Introduction

The waning of Covid-19 and the restrictions that came with it enabled the government to start delivering on its own agenda in a year that was characterized by government stability, but some changes in the parliamentary composition, municipal elections and new parties provided the potential for more disruption to the Danish party system at the next election.

Election report

No national election was held in Denmark in 2021, but there were municipal and regional elections on 16 November 2021.

Municipal and regional elections

Denmark is divided into 98 municipalities and five regions (since the structural reform of 2006). On 16 November, 4,672,643 eligible voters were called to elect a total of 2436 municipal representatives and 205 regional representatives from 9167 and 1351 candidates, respectively. Danish municipal elections are held every four years, the third Tuesday of November.

Eligible voters need to be citizens of Denmark, another European Union (EU) member state, Iceland or Norway, or be a British citizen and have lived in Denmark since 31 January 2020, or have constantly lived in Denmark in the four years before election day. Postal ballots were requested by twice as many voters as usual, and Covid-19 measures at the polling stations included outdoor tents and the possibility of voting from your car. Turnout tends to be lower at regional and municipality elections than at national elections; it reached 67 per cent in 2021, which is 4 points lower than in 2017.

While these were 103 separate elections, the overall result may be considered an indication of parties’ current standing. However, it is important to keep in mind that smaller parties tend to be underrepresented, since only the big parties stand in all regions and municipalities (KMD 2021). The two major municipal parties, Social Democrats/Socialdemokratiet (SD) and Liberals/Venstre (V) lost 4 and 2 percentage points, respectively, and ended up at 28 per cent (SD) and 21 per cent (V). The major winner of the elections was the Conservatives/Det Konservative Folkeparti (KF), who gained 6 percentage points and reached 15 per cent in total. Their main strongholds were the richer areas in the north of Copenhagen. The Socialist People's Party/Socialistisk Folkeparti (SF) (7 per cent), the Red–Green Alliance/Enhedslisten (EL) (7 per cent) and the Social Liberals/Radikale Venstre (RV) (6 per cent), all of which provide parliamentary support to the minority Social Democratic/Socialdemokratiet (SD) government, gained 1–2 percentage points. In relative terms, New Right/Nye Borgerlige (NB) was among the major winners, gaining 3.6 per cent of the vote (2.7 points more than in the last elections), which is not far from the Danish People's Party/Dansk Folkeparti (DF) at 4.1 per cent. The latter had a devastating result, with their representation more than halved. The dissolution of the Alternative/Alternativet (Alt) in 2020 (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021) translated into the waning of their local presence with a decline from 2.9 per cent to 0.7 per cent.

In almost all municipalities, only the mayor is a full-time politician, and this is the most important position. After the election, the pool of mayors was distributed as follows: 44 Social Democrats, 34 Liberals, 14 Conservatives, two from the Socialist People's Party, one from the Social Liberals, one from the Liberal Alliance and two local lists (i.e., non-national parties). The election also resulted in three Social Democratic and two Liberal regional council chairs.

In sum, the two major parties continued to dominate regional and municipal politics. But these elections also cemented the increasing support for the Conservatives, whose party chair, Søren Pape, told the delegates at the national congress in September that ‘there will be another Conservative Prime Minister’ (Pape Reference Pape2021) in reference to the only former Conservative Prime Minister, Poul Schlüter, who was in office 1982–93, and who died in May.

Cabinet report

While the parties providing parliamentary support for the government, in particular the left-wing Red–Green Alliance and the centre party Social Liberals, but less so the Socialist People's Party, have on several occasions criticized the minority Social Democratic government, no major challenges were made in 2021.

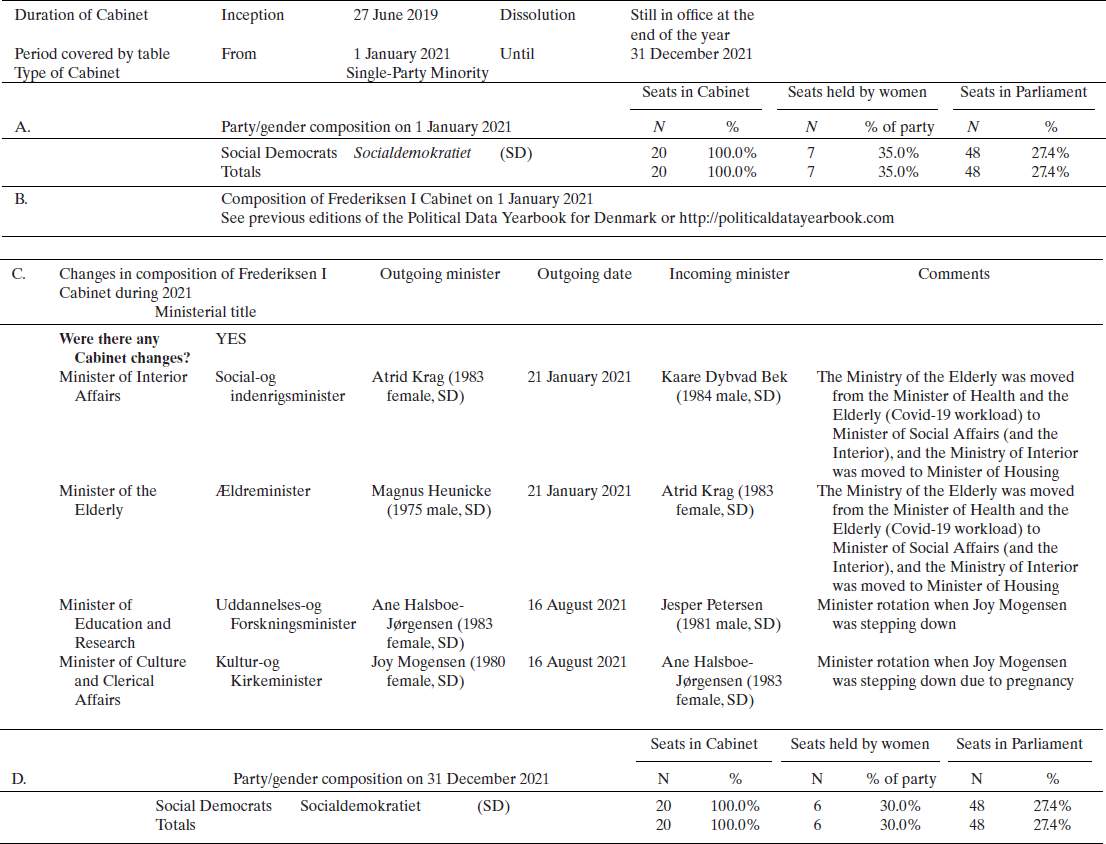

A small rotation of ministerial fields took place on 21 January. The area concerning the elderly was moved from the Minister of Health, Magnus Heunicke, to the Minister of Social and Interior Affairs, Astrid Krag, who was from then the Minister of Social Affairs and the Elderly, since the Interior Affairs portfolio was moved to Housing Minister Kaare Dybvad Bek. The most likely reason was the heavy Covid-19-related workload on the Minister of Health.

A small minister rotation took place on 16 August, when the Minister of Culture and Clerical Affairs, Joy Mogensen, stepped down. She was replaced by Ane Halsboe-Jørgensen, who left the Ministry of Education and Research to Jesper Petersen, who had been the party's spokesperson since the 2019 election – hence, the highest-ranking person in the parliamentary group. A note on Mogensen's resignation may be relevant from a gender perspective. Mogensen was a successful mayor, hence recruited from outside Parliament, when becoming minister in 2019. Four months after taking office, Mogensen had a stillborn baby. When back in office after some leave, she seemed to have been regarded as ‘the weakest link’ in government, being criticized by the opposition and the media for not taking care of the interests of the various institutions of sport, culture, entertainment, etc. within her cultural portfolio with regard to Covid-19 regulations and compensation.

Data on Cabinet composition can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Frederiksen I in Denmark in 2021

Sources: Danmarks Statistik (2019); Folketinget (2022a, 2022b); Kosiara-Pedersen (Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021); Regeringen (2022).

Parliament report

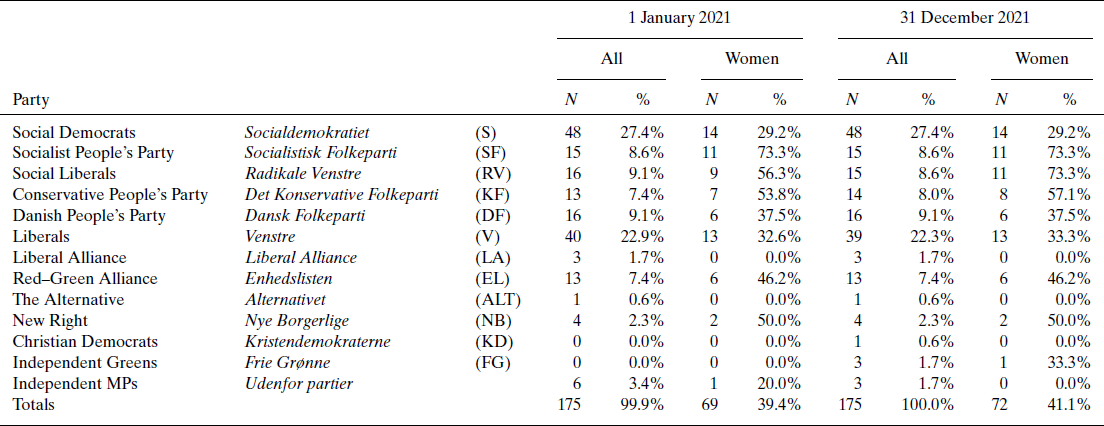

In 2021, the composition of Parliament was affected by both MPs becoming independents or changing parties, and by members leaving Parliament to a much larger extent than usual and with more prominent MPs involved (Table 2).

Table 2. Party and gender composition of the Parliament (Folketinget) in Denmark in 2021

Notes: Parliament also contains four North Atlantic representatives, two MPs from Greenland and two from the Faroe Islands. The former has two female MPs, whereas the latter has two male MPs, thus bringing the total number of women to 74 out of 179 MPs (41.3%).

Sources: Danmarks Statistik (2019); Folketinget (2022a, 2022b); Kosiara-Pedersen (Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021).

Former Prime Minister and party chair, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, announced on 1 January 2021 in his Facebook page that he was leaving Liberal/Venstre (V). But he was not leaving politics. In a book published in September 2020, he discussed taking his political engagement outside both the Liberals and the existing parties (Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen2020). Hence, a new political project seemed to be in the pipeline. In his Facebook statement, he wrote that he had decided to ‘set himself free after 40 years of Liberal membership’. He claimed that his decision had developed over time, but was finalized in the last few days when intra-party member democracy was let down (Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen2021). These comments indirectly pointed to party chair Jacob Ellemann requiring Inger Støjberg to step down as vice-chair following the Instruction Commission's report (see below). Lars Løkke Rasmussen justified continuing as an independent in Parliament, stating that ‘Due to my number of personal votes, I'm elected in my own right and will therefore not leave my parliamentary seat’ (Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen2021).

In January, former Liberal MP Jens Rohde left the Social Liberals, which he argued was becoming too top-steered and left-of-centre (Jepsen Reference Jepsen2021), and joined in April the Christian Democrats/Kristendemokraterne (KD), providing them with parliamentary representation for the first time in 10 years. Independent Greens/Frie Grønne (FG) became eligible to stand for election (see Political party report below), and is represented by three MPs who represented the Alternative until 2020 and have been independents since then (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021).

The Liberals lost three prominent members in addition to Lars Løkke Rasmussen. In December 2020, the Instruction Commission/Instrukskommissionen stated that the authorities’ administration and handling of cases concerning the accommodation of married or cohabiting asylum seekers, one of whom was a minor, had not taken place in accordance with administrative law rules and principles (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021). On that basis, Parliament decided on 2 February that the Former Minister for Integration, MP Inger Støjberg, should be brought to trial. She left the Liberals in light of their support for the trial, and when sentenced to six months of unconditional prison in December 2021 (which she served in her home in the spring of 2022), she left Parliament. Her replacement had in the meantime changed from the Liberals to the Conservatives, which means that since the election in 2019, the Conservatives have acquired three seat from the Liberals (Marcus Knuth in 2019 and Britt Bager in 2020).

In addition, Kristian Jensen, former minister, vice-chair and part of the leadership battle within the Liberals in 2019 (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2020a), left Parliament for a diplomatic position in April. Former minister Tommy Ahlers, who was recruited as an independent minister from the private sector by Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen in 2015 (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2016) and had got an excellent election result in 2019 when standing for the Liberals, left politics in August. Ahlers, a successful entrepreneur, left politics partly to develop innovative solutions to the green transmission, partly since ‘politics is too much about the game and too little about visions and good ideas’ (Mazor Reference Mazor2021).

The remaining two MPs leaving Parliament in 2021, both from within the Social Liberals, did so for reasons related to the #metoo movement. Morten Østergaard had stepped down as party chair in 2020 due to his poor handling of a case of sexual harassment within the parliamentary group, where he covered up he had harassed a fellow MP 10 years previously (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021). He left Parliament in 2021. Kristian Heegaard, the first Danish MP in a wheelchair, also left Parliament in August after being involved in a case of sexual harassment.

The share of women elected to Folketinget had been 37–39 per cent in the 1998–2019 period, but never surpassed 40 per cent (Folketinget 2022a, 2022b). In 2021, when three of the men leaving Parliament were replaced by female MPs, the share of women reached a record high of 41 per cent.

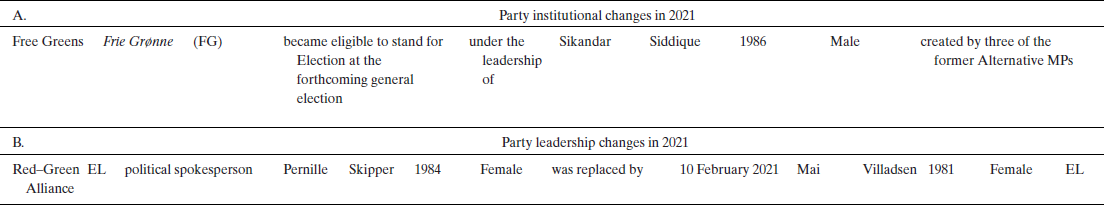

Political party report

Several parties that did not stand for election or achieve representation in 2019 gained the necessary signatures to be able to field candidates at the next general election. The Christian Democrats and the Vegan Party/Veganerpartiet (VP) had already become eligible in 2020 (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021). In 2021, Independent Greens, a party created and represented in Parliament by three former members of Alternative, also obtained the required signatures to stand at the next general election. Even though the new party, Moderates/Moderaterne (M) created by former chair of the Liberals, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, had collected the required number of signatures by mid-September 2021 (Dreiager Reference Dreiager2021), they waited until 14 March 2022 to make a formal application. Hence, by the end of 2021, a total of 13 parties were eligible to field candidates at the coming election, which was to be held by June 2023 at the latest.

The Red–Green Alliance parliamentary group unanimously replaced Pernille Skipper with Mai Villadsen as political spokesperson on 10 February 2021. The party has collective leadership, so this position is the closest to a party chair. The change was scheduled due to the party's principle of rotation.

In August 2021, the Danish People's Party vice-chair Morten Messerschmidt received a six-month suspended prison sentence due to misuse of EU funding at a party meeting where EU matters were not being discussed and forgery in relation to this. In December, the judge was recused from the case due to him liking a Facebook message which could be interpreted as critical of Messerschmidt, and the case was sent to retrial with a decision expected by December 2022. If sentenced again, Messerschmidt could appeal the decision, hence prolonging any final assessment. The lack of a final verdict implied that Messerschmidt was not completely out of the question when the Danish People's Party chair, Kristian Thulesen Dahl, in light of the very poor election result at the municipal and regional elections in November 2021 (see above), decided to step down. Dahl had met internal opposition for a while, and the dissatisfaction became more apparent. Particularly noticeable is Pia Kjærsgaard's (party founder and former party chair) waning support for Thulesen; this indicated a true split among the group of party founders (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen, Elklit and Nedergaard2020b). Messerschmidt was then elected as new party chair at an extra-ordinary party congress in January 2022.

Data on changes in political parties can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Changes in political parties in Denmark in 2021

Sources: Kehlet (Reference Kehlet2021); Schrøder (Reference Schrøder2021).

Institutional change report

There were no major institutional changes in 2021.

Issues in national politics

Covid-19 still played a role in Danish politics and society in 2021. Everything reopened in June, and by September all restrictions had been lifted. The Mink Commission, which investigated the process around illegal orders to cull minks in light of Covid-19 contamination risks (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021), continued to prove a challenge to the government. In particular, the roles of Prime Minister Frederiksen and the Permanent Secretary/Departementchef were questioned. The commission revealed a very tough language of communication among the top people dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic. This harsh image was not contradicted when Frederiksen said that we should ‘just accept it’ (lev med det). More importantly, the commission's investigation has been affected by the lack of access to the communications between decision-makers. In particular, the deletion of text messages was an issue.

The waning effect of Covid-19 (and the more limited severity of the omicron variant in the fall) meant that the government had time to deliver on other issues. The spring brought an agreement on the relocation of 10 per cent of the university and college education delivery from the urban centres to other areas of Denmark in May, and an agreement on investment in roads and railways in June. Over the summer, a nurses’ strike went on for 10 weeks to demand better working conditions. However, the strike stopped by legal requirement after 10 weeks in August. In October, a deal was made on climate action within the agriculture sector, while November brought a deal on affordable housing. At the international scene, US President Donald Trump suggested buying Greenland from Denmark in May, and Denmark withdrew its troops from Afghanistan together with the rest of the international community.

It is the prerogative of the Danish Prime Minister to call elections (within a maximum of four years). While opinion polls show a trend towards ‘rallying around the flag’ and increased support for the governing parties during the Covid-19 pandemic, their electoral surplus is likely to have diminished. The next general election is to be held by June 2023, but it remains to be seen whether it is called earlier. The decision will be affected by the extent to which Prime Minister Frederiksen is criticized in the report from the Mink Commission.