Introduction

Although international surveys show that citizens of the world believe that democracy is the best system of collective governance (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Bol and Ananda2021; Norris, Reference Norris2011), the functioning of representative democracy is increasingly criticized. There is growing public distrust against politicians and parties (Cain et al., Reference Cain, Dalton and Scarrow2003; Van der Meer, Reference Van der Meer2017), which many consider as a cause of the decline in electoral participation (Grönlund & Setälä, Reference Grönlund and Setälä2007), the surge in populism (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019) as well as a general threat to the survival of current political regimes (Rosanvallon, Reference Rosanvallon2008). It is within this context that a growing body of normative‐driven research promotes participatory and deliberative models of democracy (Fishkin et al., Reference Fishkin, Siu, Diamond and Bradburn2021). Under these models, citizens are more often and more closely associated with policymaking through deliberative forums, in which a small group gathers to deliberate and make recommendations, and sometimes even decisions, regarding policies (Curato et al., Reference Curato, Farrell, Geissel, Grönlund, Mockler, Renwick, Rose, Setälä and Suiter2021; Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2009; Fishkin, Reference Fishkin2009). Deliberative democracy is thus often seen as a remedy to the ‘malaise’ of representative democracy (Geissel & Newton, Reference Geissel and Newton2012).

Building on such promises, the appeal for deliberative democracy has grown gradually among academics and practitioners. It has gained visibility these past years after several European governments have taken major initiatives of the sort. In 2012, the Irish government installed a constitutional convention that gathered 66 randomly selected citizens and 33 MPs to propose constitutional amendments (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Suiter and Harris2019). Since then, Ireland has renewed the experience twice with two new conventions fully composed of citizens selected by lot. Other recent examples include the French convention on climate and the British climate assembly, both organized between 2019 and 2020. In 2021, the German Bundestag endorsed two such initiatives, one on the fight against climate change and the second on the country's position in the global order. The POLITICIZE project has identified 127 deliberative citizens’ assemblies at the national and regional levels in Europe since 2000, most of them after 2015 (Paulis et al., Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2020).Footnote 1 In a report released last year, the OECD (2020) uses the expression ‘deliberative wave’ to refer to the growing interest in the institution in Europe.

In this paper, we study public opinion about deliberative democracy. We evaluate whether this new model attracts supportFootnote 2 from the ‘right’ citizens (i.e., those who are dissatisfied) and whether this support is motivated by the ‘right’ reasons (i.e., for the model itself rather than the expected policy outcome). To do so, we rely on a unique large‐scale survey with representative samples of the populations of 15 Western European countries (N = 14,043). In this survey, we asked respondents whether they support the use of (decisional) deliberative citizens’ assemblies in their country. We also embedded an original survey experiment in which we randomly exposed respondents to the level of support for three policies in their country (real figures, no deception). This design allows us to explore whether support increases when respondents know that their co‐nationals share their policy preferences and thus whether they could expect deliberative citizens’ assemblies to lead to an outcome that is favourable to them.

Although this paper addresses the broader question of support for deliberative democracy, we focus on deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition, also called deliberative mini‐publics. These are the most popular deliberative institutions that have been used these past years. Curato et al. (Reference Curato, Farrell, Geissel, Grönlund, Mockler, Renwick, Rose, Setälä and Suiter2021, p. 4) define them as ‘carefully designed forums where a representative subset of the wider population come together to engage in open, inclusive, informed and consequential discussions on one or more issues’. One of their core features is that ‘[they] are designed to actively recruit participants to ensure some form of statistical representativeness of the population affected by the issue’ (Curato et al., Reference Curato, Farrell, Geissel, Grönlund, Mockler, Renwick, Rose, Setälä and Suiter2021, p. 5). Most often, such representativeness is achieved through sortition, that is the selection of group citizens at random in the population at large.

Who should support deliberative democracy and why?

Deliberative democracy conveys much hope for the future of democracy (van der Does & Jacquet, Reference Van der Does and Jacquet2021). Such hopes include empowering and engaging participating citizens and equipping them with deep policy knowledge to make them efficient decision‐makers (Curato et al., Reference Curato, Dryzek, Ercan, Hendriks and Niemeyer2017; Fung, Reference Fung2003; Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund, Setälä and Herne2010; Knobloch & Gastil, Reference Knobloch and Gastil2015; Papadopoulos & Warin, Reference Papadopoulos and Warin2007). Advocates of this model argue that it can also have a spill‐over effect on the system at large by improving the quality of political deliberation outside the deliberative forums (Curato & Böker, Reference Curato and Böker2016; Lafont, Reference Lafont2019) and by enhancing the legitimacy of public policies (Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006; Warren & Gastil, Reference Warren and Gastil2015). Some argue that deliberative democracy would indeed affect the attitudes of non‐participating citizens. By its role in policymaking, it would help engage the population in politics (Beauvais & Warren, Reference Beauvais and Warren2019; Màr & Gastil, Reference Már and Gastil2021; Setälä & Smith, Reference Setälä, Smith, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018). This is particularly crucial for citizens who have lost trust in politicians and representative democracy (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018; Curato et al., Reference Curato, Vrydagh and Bächtiger2020; Fung, Reference Fung2006; Zittel & Fuchs, Reference Zittel and Fuchs2006).

Yet, the literature on the topic is not unanimous: some scholars argue that deliberative democracy could in fact reinforce inequalities in political participation by giving an even greater role in policymaking to the educated and those who are already politically engaged. They predict that the educated and engaged citizens are indeed those who would be the most enthusiastic about these forums and then the most likely to accept to participate (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, van der Kolk, Carty, Blais and Rose2011; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Bächtiger, Shikano, Reber and Rohr2016; Jacquet, Reference Jacquet2017; Rojon & Pilet, Reference Rojon and Pilet2021; Sanders, Reference Sanders1997; Young, Reference Young, Fishkin and Laslett2003). Lafont, for instance (Reference Lafont2015, Reference Lafont2017, Reference Lafont2019) warns that the disengaged might reject deliberative instruments if they feel alien to the participants, their preferences and their decisions. Moreover, she argues that the public might not be on board as participating citizens, unlike elected politicians, are by design not accountable to the rest of the society.

Connecting those debates, we study in this paper whether Western Europeans support deliberative democracy and whether it has the potential to deliver its promise of re‐engaging disenfranchised citizens. In particular, we evaluate (1) whether those who are dissatisfied are the most supportive of the model and (2) whether support is driven by the institution itself rather than an expectation regarding a favourable policy outcome. First, the deliberative model should in theory be particularly popular among those who are disengaged from, dissatisfied with, and marginalized by representative democracy. The institution would indeed give them an alternative platform to participate in policymaking (Talukder & Pilet, Reference Talukder and Pilet2021; Webb, Reference Webb2013 ). However, the opposite might be true as well. The resource model of participation indeed states that citizens with high levels of socio‐economic resources are more likely to be politically engaged and participate in politics (Almond & Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1963; Brady et al., Reference Brady, Verba and Scholzman1995; Dalton & Welzel, Reference Dalton and Welzel2014; Norris, Reference Norris2011). Hence, the alternative hypothesis is that deliberative democracy is primarily appealing to citizens who are already highly engaged with, and interested in, representative politics. Those citizens might like these institutions because they give them the possibility to participate even more in policymaking, beyond the simple act of voting once every few years (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004). Identifying who supports deliberative democracy is thus important to evaluate if this model can re‐engage the dissatisfied or maintain (or even worsen) the gap in political participation.

Second, still from the perspective of finding out whether deliberative democracy can deliver its promise, it is not enough to know whether the ‘right’ citizens support it; we also need to know whether they do so for the ‘right’ reasons. Citizens’ support for a political institution can be driven by a belief that the institution itself is good, for example, because it is seen as fair or efficient, or by a selfish motivation that the institution is likely to lead to an outcome that is favourable to them (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2019; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). For example, a citizen might support deliberative democracy because they prefer the likely policy that will be implemented at the end of the process. Studying motivations behind support for the deliberative model is thus important because if this support is contingent on the expected policy outcome, it is necessarily fragile. As soon as the outcome stops being favourable, citizens will stop supporting it. The question of losers’ consent, that is, the propension of citizens to accept the possibility of losing without questioning the political institution that led to this defeat, is fundamental to the functioning of any democratic model, including deliberative democracy (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Chu, Wu and Thomassen2014).

Hypotheses

In order to build hypotheses about who supports deliberative citizens’ assemblies and why, we mobilize the theoretical literature on the virtues of deliberative democracy, as well as the recent empirical studies that investigate public support for deliberative institutions (e.g., Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018; Bedock & Pilet, Reference Bedock and Pilet2020a; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2021; Jacobs & Kaufman, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021; Már & Gastil, Reference Már and Gastil2021, Pow, Reference Pow2021; Rojon et al., Reference Rojon, Rijken and Klandermans2019; Rojon & Pilet, Reference Rojon and Pilet2021; Talukder & Pilet, Reference Talukder and Pilet2021; van der Does & Kantorowicz, Reference Van der Does and Kantorowicz2021). We also build on the numerous studies that examine support for referendums and, more generally, for a greater role of citizens in policymaking (e.g., Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007; Christensen, Reference Christensen2020; Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Burklin and Drummond2001; Donovan & Karp, Reference Donovan and Karp2006; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2019; Gherghina & Geissel, Reference Gherghina and Geissel2019, Reference Gherghina and Geissel2020; Landwehr & Harms, Reference Landwehr and Harms2020; Neblo et al., Reference Neblo, Esterling, Kennedy, Lazer and Sokhey2010; Schuck & de Vreese, Reference Schuck and De Vreese2015; Webb, Reference Webb2013; Werner, Reference Werner2020). Even though these studies do not focus on support for deliberative democratic instruments, they explore, just like us, the question of whether empowering citizens by giving them a more direct role in policymaking can re‐engage them in politics (Bedock, Reference Bedock2017).

We propose three sets of hypotheses. The first two address the question of who should support deliberative citizens’ assemblies. According to the literature, there are two groups of determinants. The first one is political engagement (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007). Citizens who are very active and highly interested in politics should be more demanding of these institutions, as they might be no longer be satisfied with the simple act of voting in elections. They might want more opportunities to voice their concerns. Bowler et al. (Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007) refer to them as ‘engaged’, Norris (Reference Norris2011) as ‘critical’ and Dalton and Welzel (Reference Dalton and Welzel2014) as ‘assertive’ citizens. Some studies claim that engaged citizens should be more positive about deliberative democracy than about referendums because they have an even more active role in the former. With deliberative institutions, they can indeed actively participate in political discussions and try to convince others about their policy preferences (Anderson & Goodyear‐Grant, Reference Anderson and Goodyear‐Grant2010).

We measure political engagement in two different ways and formulate two different hypotheses. On the one hand, we measure political engagement directly using attitudinal variables related to the concept. We posit that support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies should be stronger among citizens who are highly interested in politics and who feel politically competent. On the other hand, we measure it indirectly using socio‐demographic variables that are directly associated with political engagement and should thus be indirectly associated with support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies. We know from the ‘resource model’ that citizens who have many socio‐economic resources, typically education and wealth, are more engaged and participative in politics (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Verba and Scholzman1995). They should, thus, also be supportive of a greater role of citizens in policymaking. Several studies find a positive correlation between socioeconomic status and support for the direct involvement of citizens in policymaking (Coffé & Michels, Reference Coffé and Michels2014; Dalton & Welzel, Reference Dalton and Welzel2014; Del Río, Navarro & Font, Reference Fung2016; Vandamme et al., Reference Vandamme, Jacquet, Niessen, Pitseys and Reuchamps2018; Webb, Reference Webb2013). This leads to the first group of hypotheses related to the engaged citizens’ thesis:

H1a: Support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition is higher among engaged citizens.

H1b: Support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition is higher among citizens who are better off in terms of education and income.

The second group of determinants of support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies is related to dissatisfaction with representative politics.Footnote 3 This concerns citizens who are unhappy with the current system (Bengtsson & Mattila, Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009; Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007; Del Río, Navarro & Font 2016; Coffé & Michels, Reference Coffé and Michels2014; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Niessen and Reuchamps2022; Webb, Reference Webb2013). We measure political dissatisfaction using direct attitudinal variables: a negative evaluation of the way democratic institutions work, and a negative judgment of the main actors involved, that is, governments and politicians (Allen & Birch, Reference Allen and Birch2015; Gherghina & Geissel, Reference Gherghina and Geissel2019; Schuck & de Vreese, Reference Schuck and De Vreese2015). Regardless of the source of dissatisfaction, dissatisfied citizens should be more supportive of deliberative citizens’ assemblies. This leads to a second hypothesis:

H2: Support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition is higher among politically dissatisfied citizens.

The third hypothesis addresses the question of why people support deliberative citizens’ assemblies. The literature usually distinguishes two types of motivation that drive support for political institutions: (1) the adhesion to the institutions themselves, for example, because they are considered fair, efficient or, more generally, positive for the community and (2) a selfish desire for the policy outcome that it is expected to emerge from these institutions (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Himmelroos and Setälä2019; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2019; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2022). This line of reasoning, sometimes labelled ‘outcome favourability’, is quite common in the literature. There is, for example, evidence that citizens prefer the electoral system that gives an advantage to their preferred party or candidate (Aldrich et al., Reference Aldrich, Reifler and Munger2014; Banducci & Karp, Reference Banducci and Karp1999), that they are also keener on organizing a referendum on a policy issue when they recently won a referendum on a similar one (Brummel, Reference Brummel2020) or when they know that their policy preference is shared by the majority of their co‐nationals (Landwehr & Harms, Reference Landwehr and Harms2020; Werner, Reference Werner2020). This pattern also exists in the choice of other institutions including those of technocratic governance (Arnesen, Reference Arnesen2017; Beiser‐McGrath et al., Reference Beiser‐McGrath, Huber, Bernauer and Koubi2022; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2019; Harms et al., Reference Harms, Landwehr, Lutz and Tepe2021; Landwehr & Leininger, Reference Landwehr and Leininger2019; van der Does & Kantorowicz, Reference Van der Does and Kantorowicz2021).

In our third hypothesis, we apply the same logic to deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition. If a citizen's support is driven by outcome favourability, it should increase with the probability that the institution leads to the implementation of their favourite policy. Since these assemblies are composed of citizens randomly selected from the population at large, the likelihood of this policy being implemented increases with the share of other citizens preferring this policy.Footnote 4 In other words, if one knows that their views are shared by most of their co‐nationals, they should support deliberative citizens’ assemblies as they will likely lead to a policy outcome that they like. The third hypothesis is thus the following:

H3: Support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition is higher when citizens know that their preference for a certain issue is shared by their co‐nationals.

Research design

Data

We conducted a web‐based survey between 2 March and 3 April 2020, for which we interviewed 15,406 adults across 15 Western European countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.Footnote 5 The respondents were recruited by the survey company DyNata (formerly known as Survey Sampling International, https://www.dynata.com/, last accessed on 18 May 2022), which used country‐specific age, gender, education, and region quotas matched to the latest census data to ensure that each national sample is representative of the population of the corresponding country on these socio‐demographic characteristics. These quotas were strictly applied until the end of the data collection. The survey took about 15 minutes and included questions about political attitudes and preferences. We believe the case of Western European countries is particularly informative because these countries have a long tradition of representative democracy, which means that citizens have had the opportunity to experience it and identify its advantages and limits.

Dependent variable

To test H1 and H2, we use a dependent variable that captures support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies in general. Throughout the middle of the survey, we introduced respondents to the idea of deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition with a short message:

People sometimes talk about the possibility of letting a group of citizens decide instead of politicians. These citizens will be selected by lot within the population and would then gather and deliberate for several days in order to make policy decisions, like politicians do in parliament.

This is obviously a simplification of the institution. However, with this kind of web‐based survey interface, written instructions need to be short and simple to ensure readability and understanding, and further maximize the likelihood of receiving meaningful answers. This is particularly important when the questions revolve around objects like deliberative citizens’ assemblies that might not be well‐known to all respondents, compared to long‐standing institutions like referendums (Bächtiger & Goldberg, Reference Bächtiger and Goldberg2020).

The short description of deliberative citizens’ assemblies in our survey covered their two main characteristics: (1) composed of citizens selected by lot who (2) convene to deliberate on policy issues. For this reason, we expect answers to be meaningful. In fact, we observe that only 5% of all respondents answered ‘don't know’ to this question (we removed them from the dataset). Nevertheless, we cannot fully discard the possibility that some respondents would have answered differently if they would be provided with more information.

After the short description of deliberative citizens’ assemblies, we asked respondents to answer the following question: ‘Overall, do you think it is a good idea to let a group of randomly‐selected citizens make decisions instead of politicians on a scale going from 0 (very bad idea) to 10 (very good idea)?’ Importantly, with this question, we referred to deliberative citizens’ assemblies as an alternative policymaking institution. We acknowledge that this is a radical form, as in most instances these assemblies are simply consultative (Paulis et al., Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2020; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017; Setälä & Smith, Reference Setälä, Smith, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018). We nonetheless opted for a decisional version of the institution to reveal respondents’ preferences by increasing the stakes. We feared that even those who do not particularly like deliberative citizens’ assemblies would still report some support for a consultative version of the institution because they see it as ‘harmless’. However, we keep the radical nature of the question in mind while interpreting the results below, as previous studies indicate a higher level of public support for the consultative version than for the decisional one (Bedock & Pilet, Reference Bedock and Pilet2020a; Rojon & Rijken, Reference Rojon and Rijken2021).

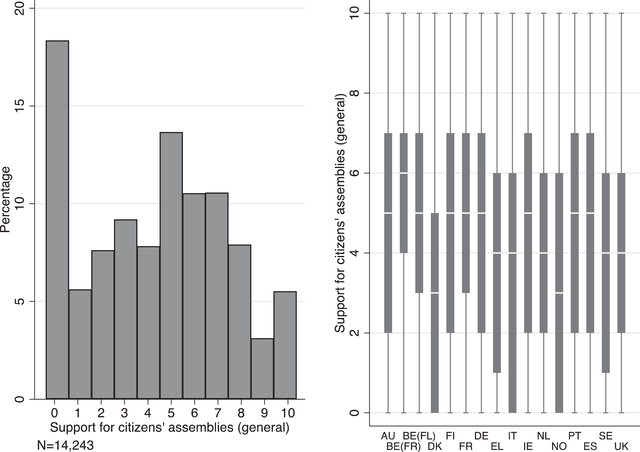

The left panel of Figure 1 reports the distribution of the dependent variable among all respondents in the form of a histogram.Footnote 6 First, it reveals that support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies is not particularly high. The median is below the midpoint of the 0–10 response scale (4.32). We need to be cautious about the interpretation of this result, however, given that we presented in the survey the institution as decisional (see above). Second, we observe a large standard deviation (3.05). This high dispersion seems to be mainly driven by the high proportion of respondents (about 18%) who think that citizens’ assemblies are a ‘very bad idea’ (0 on the 0–10 scale). By contrast, about 6% think that the institution is a ‘very good idea’ (10 on the 0–10 scale). There is thus a rather high polarization on the topic, although 14% of the respondents seem to be indifferent (5 on the 0–10 scale).

Figure 1. Distribution of the dependent variable.

The right panel of Figure 1 reports the distribution of support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies per country in the form of boxplots. It reveals that the median is either 4 or 5 on the 0–10 scale, the first quartile either 2 or 3, and the third one either 6 or 7. Strikingly, although Denmark, Norway (median at 3 and Q1 at 0) and Italy (median at 4, Q1 at 0) show slightly lower levels of support and French‐speaking Belgium (median at 6 and Q3 at 7) slightly higher levels, support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies are relatively constant across countries.

Explaining these (relatively minor) cross‐country variations falls beyond the scope of this paper, especially since the survey only covers 15 countries and does not give us a lot of variations in terms of relevant macro variables. That said, one possible explanation could be past exposure to the deliberative citizens’ assemblies and thus familiarity with their positive and/or negative aspects. Although it is unreasonable to think that many West Europeans know about them, it is possible that some of those who live in a country where they have been used are more familiar. We thus explore the correlation between our dependent variable and another one measuring the number of deliberative citizens’ assemblies organized in the respondent's country since 1990 at the national and regional levels (taken from Paulis et al., Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2020). This correlation is almost null (i.e., 0.03), which either means that past exposure does not increase familiarity (deliberative citizens’ assemblies are not much mediatized) or that familiarity does not affect support.

Independent variables

We asked the questions aimed at testing H1a, H1b and H2 at the beginning of the survey. To test H1a, we use two well‐known indicators of political engagement: self‐reported political interest (1 not interested at all, 4 very interested) and self‐reported political competence (politics is too complicated for people like me, 1 strongly agree, 4 strongly disagree). This last survey question is usually used to measure internal political efficacy (Craig & Maggiotto, Reference Craig and Maggiotto1982). In order to test H1b, we use highest education attainment (for the sake of comparison between countries we recoded the education variables in three levels, 0 no secondary degree, 1 secondary degree, 2 university degree) and feeling of income security (how you feel about your household's income nowadays? 1 find it difficult to very difficult to live, 4 living comfortably). This subjective income variable has the advantage of having fewer missing values than the one about objective income (because of respondents refusing to answer). It is also more comparable across countries with different costs of living.

To test H2, we use two survey questions to measure political dissatisfaction. First, we use satisfaction with the way democracy works in the country (0 extremely dissatisfied, 10 extremely satisfied). Second, we use a set of questions from the literature on populism and anti‐elite sentiment (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Hebling and Littvay2020). We asked respondents to give their degree of agreement (1 strongly agree, 4 strongly disagree) with the following two statements: ‘the government is run by a few big interests looking out for themselves’ and ‘government officials use their power to try to improve people's lives’. After inverting the variable relative to the second statement, we sum the two and divide them by two (Cronbach alpha = 0.47). The aggregate variable thus measures the respondent's evaluation of elites and ranges from 1 (very negative) to 4 (very positive)

We also use a few control variables in our regression. In line with standard practices, we include both socio‐demographic variables as well as attitudes that are linked to support for greater citizen participation in policymaking in the existing literature. These are age, gender (0 male, 1 female), urbanization (1 living in a farm or home in the countryside, 5 living in a big city), voting (0 not voted at last election, 1 voted), voting for the incumbent (0 intention to vote for another party than one in government, 1 intention to vote for a party in government) and self‐reported left‐right position (0 extreme left, 10 extreme right).

Experiment

To test H3, we embedded in our survey an experiment revolving around three specific policy issues, that is, European integration, social benefits and immigration.Footnote 8 First, at the beginning of the questionnaire, we elicited policy preferences about these three issues using the related questions from the European Social Survey (https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/, last accessed on 18 May 2022).Footnote 9 Second, right before the questions about deliberative citizens’ assemblies, we added an experimental vignette: at random, we exposed half of the respondents to the proportion of citizens in their country who share their policy preference about each of the three issues (in particular, the proportion of those who agree or strongly agree with the three policy statements). Importantly, this vignette included real figures from the latest wave of the European Social Survey (from 2018 or 2016 depending on country and data availability).Footnote 10

Third, we asked respondents about their level of support for the deliberative citizens’ assemblies if they were applied to the three specific policy issues. This question appeared on the same screen as the experimental vignette, and right before the question about support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies in general.Footnote 11 In Appendix D, we report the balance test showing that the treatment assignment was unrelated to pre‐treatment variables. In Appendix E, we report the result of a manipulation check, which shows that the experimental vignettes indeed made respondents update their beliefs about the preferences of their co‐nationals for the three policy issues.

According to H3, we expect that a respondent will be supportive of deliberative citizens’ assemblies if they know that their views are shared by many of their co‐nationals. To capture this, we use two variables for each of the three policy issues. The first one is simply a binary variable capturing whether the respondent saw the vignette or not (0 control group, 1 treatment group). The second one is a construct variable that captures whether the respondent's preference for each of the three policy issues is shared by their fellow citizens and by what margin. We call this variable the ‘Share of population aligned with respondent’. It is as follows:

For respondents in favour of policy issue i,

For respondents against policy issue i.

The variable can go from −0.5 to +0.5. A negative value means that the respondent's preference for a given policy issue is not supported by a majority of their co‐nationals, and a positive value means that it is.Footnote 12 Zero means that exactly 50% of citizens in the country are in favour of it. For example, someone against European integration in a country where 65% of the population is also against it has a score of 0.15 on this variable (=0.65−0.50). Another respondent in favour of European integration in the same country has a score of −0.15 (=−(0.65−0.50)). Note that respondents who are indifferent to the policy issues (neither agree nor disagree with the policy statement) are assigned 0 on this variable. Our expectation is that for respondents who received the experimental vignette, the variable ‘Share of population aligned with respondent’ should be positively associated with support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies. In our regression, we test this by adding an interaction term between the construct variable and the binary treatment variable.

Such an experimental design has some key advantages for eliciting the motivations that drive support for political institutions. First, by providing respondents with the real proportion of co‐nationals sharing their views (instead of asking their perception of this proportion), we reduce the interference of uncertainty and ‘wishful thinking’ (i.e., one's propensity to exaggerate the proportion of co‐nationals sharing their views). Second, we introduce an exogenous variation in the variables of interest, which then leads to a more credible causal identification of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Finally, by using real figures from the European Social Survey, we do not deceive respondents, which would be ethically questionable.Footnote 13

Results

Who supports deliberative citizens’ assemblies?

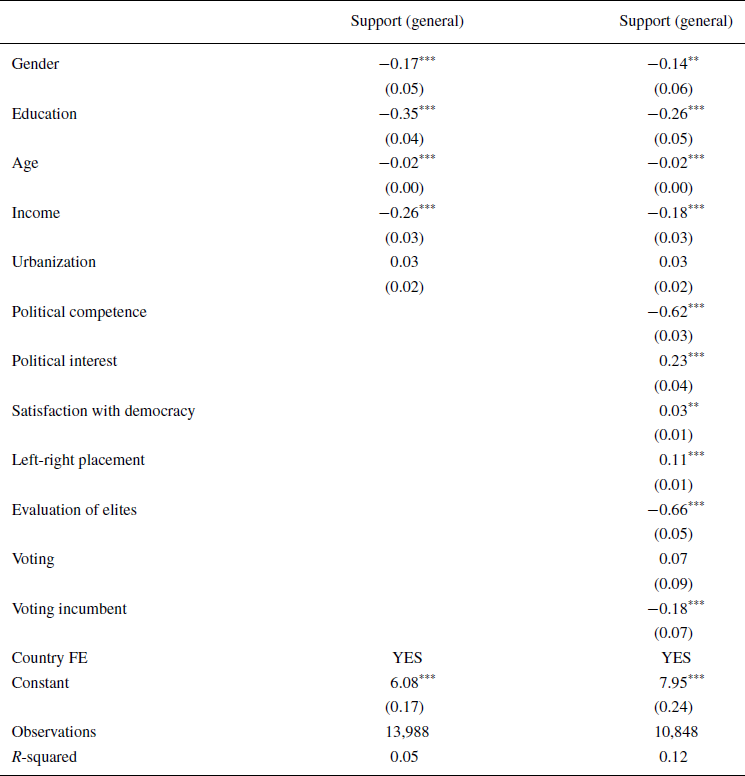

Table 1 reports the results of two Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regressions predicting support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition in general. In the first one, we only include the socio‐demographic variables presented above as predictors. In the second, we also include those capturing political attitudes. The reason for having two separate regressions comes from the possibility that political attitudes are the products of socio‐demographic characteristics. In including both as predictors, the coefficient estimates relative to socio‐demographic characteristics can thus be altered by a post‐treatment bias. In each of these two regressions, we use country fixed effects to account for differences between countries.

Table 1. Regressions about who support deliberative citizens’ assemblies

Note: Entries are coefficient estimates from OLS regressions predicting support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition in general. Standard errors are in parentheses.

* p < 0.1;

** p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.01 (two‐tailed).

We find little evidence for H1a and H1b. We do not observe stronger support among respondents who have high levels of political engagement. The only independent variable measuring the concept that is positively correlated with the dependent variable is political interest (p < 0.01). Yet, the magnitude of this correlation is small. Going from the minimum to the maximum of the variable (1–4, i.e., the ‘full effect’) increases support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies by 0.90, which is less than a third of the standard deviation of the dependent variable. This effect could be explained by the greater familiarity with the institution of respondents who are highly interested in politics (Michels, Reference Michels2011).

By contrast, political competence on the one hand, and education and income on the other, are all negatively associated with the dependent variable (p < 0.01). The correlations are stronger than those with political interest. The full effects vary between −1.00 and −1.40 for income and education and −1.90 for political competence. This last effect corresponds to a reduction of 60% of the standard deviation of the dependent variable. In other words, the results point in the direction of stronger support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies among less politically engaged respondents. Interestingly, we also observe stronger support among specific social groups who tend to be more politically disengaged such as women and youth.

By contrast, we find stronger evidence for H2. Contrary to the hypothesis, satisfaction with democracy seems to be positively correlated with support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies. However, this correlation is weak (full effect = + 0.20) and barely statistically significant (p < 0.1) despite the sample size of more than 10,000 respondents. By contrast, there is a strong correlation between the evaluation of elites and the dependent variable. The full effect is −2.72 (p < 0.01), which corresponds to a decrease of 90% of the standard deviation of the dependent variable. This suggests that support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies is stronger among citizens who hold negative views of political elites.

To assess the robustness of these results, we conduct a series of supplementary tests. First, since we asked the question used as the dependent variable after exposure to the experimental vignette, we reproduce the analysis of Table 1 by reducing the sample to the control group. Appendix F shows that results are very similar. Second, we reproduce the analysis by grouping the ‘engaged’ (political interest and political engagement) and ‘dissatisfied’ independent variables together (satisfaction with democracy and evaluation of elites) to make the results less sensitive to mistakes and errors in individual variables. After standardizing each variable between 0 and 1, we form aggregate indicators of the two concepts in summing the related variables. Appendix F shows that the more politically dissatisfied a respondent is, the more supportive they are of deliberative citizens’ assemblies (p < 0.01), but that political engagement is negatively associated with the dependent variable (p < 0.01), which confirms the findings of Table 1.

Third, we reproduce the analysis by using a multinomial logit regression predicting a negative evaluation of deliberative citizens’ assemblies (0–3 on the original 0–10 scale), or a positive one (7–10), relative to a neutral one (4–6). This extra analysis allows us to check whether the effects presented in Table 1 are symmetric. Results in Appendix F show that they are. The only independent variable that does not seem to have a symmetric effect is political interest. The variable is positively correlated with both positive and negative evaluations of deliberative citizens’ assemblies, which means that respondents with a low level of political interest are mostly indifferent to the institution and that those with a high level are polarized. Finally, we reproduce the analysis of Table 1 by replacing the dependent variable with each of the three policy‐specific dependent variables. Appendix G shows that the results are also sensibly similar, which indicates that the determinants of support are similar across policy issues.

Finally, we evaluate the stability of our results across countries. First, we reproduce the analysis in Table 1 in each of the 15 countries covered in the survey, separately. Appendix H shows that the negative correlation between the dependent variable and education, political competence and evaluation of politicians is very robust: they exist in virtually all countries. Second, we reproduce the analysis of Table 1 by considering the number of deliberative citizens’ assemblies organized in the country at the national or regional levels since 1990 (Paulis et al., Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2020). We add an interaction between this variable and each of the independent and control variables of the regression. Appendix I shows that none of the interactions with the independent variables involved in the hypotheses is statistically significant, which indicates that the determinants of support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies are no different among respondents who live in a country where such initiatives are frequent, compared to those who live in a country where they are not.

Overall, we find evidence in favour of H2, but not for hypotheses H1a and H1b. Supporters of citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition seem to be rather disengaged or politically dissatisfied: they have low education levels, a negative opinion about political elites, and do not feel politically competent.

Why do people support deliberative citizens’ assemblies?

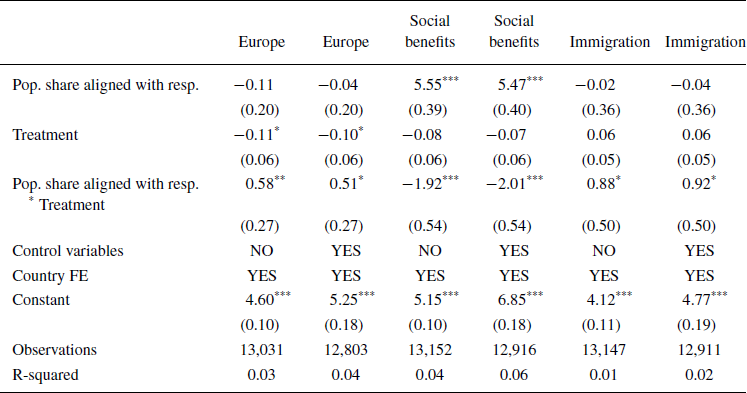

Table 2 reports the results of a series of OLS regressions predicting support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies for each of the three policy issues included in the survey. The main predictors are (1) the treatment variable (0 control group, 1 treatment group), and (2) the share of the population of the respondent's country with a preference that aligned with them on the issue, and (3) an interaction between these two. Note that, for each policy issue, we present the results with and without the control variables presented above. Although the test is based on an experimental design, which does not normally require any control variable, it does here, since the randomized treatment is not the only variable of interest. For this reason, we also include the overall share of citizens supportive of the issue in the respondent's country as a supplementary control variable. Table 2 shows that the interaction term is mostly positive and statistically significant (at least at p < 0.1). This result indicates that, as expected in H3, the treatment status moderates the relationship between the variable ‘Population share aligned with respondent’ and support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies.Footnote 14

Table 2. Regressions about why people support deliberative citizens’ assemblies

Note: Entries are coefficient estimates from OLS regressions predicting support for citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition (per policy). Standard errors are in parentheses. Control variables are age, gender, education, income, urbanization and overall support of the policy issue in the respondent's country (regardless of their own position).

* p < 0.1;

** p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.01 (two‐tailed).

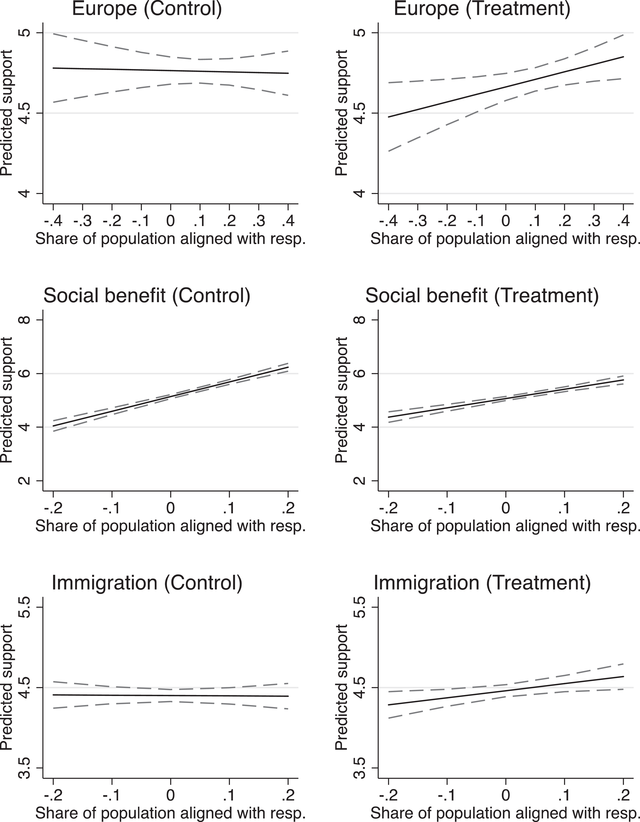

To facilitate the interpretation of the results, we plot the predicted values and 95% confidence intervals in separating the control and treatment groups. In Figure 2, we observe flat lines in control groups, which suggests that respondents’ support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies is not affected by the share of their co‐nationals who have a position that aligns with them when they do not have this information (probably because they cannot anticipate it). By contrast, we observe positive lines in treatment groups, which means that respondents’ support increases when they know that many of their co‐nationals share their policy preferences. An important exception is for social benefits. For this policy issue, the line is positive in both the treatment and control group, which suggests that respondents can anticipate the share of their co‐nationals that aligns with them, even without seeing the experimental vignette.

Figure 2. Predictive support for citizens’ assemblies as treatment varies. Note: Lines are predicted values from OLS regressions in Table 2 (with control variables). Dashed lines are 95%‐confidence intervals.

The full effect of the variable ‘Share of population aligned with respondent’ goes from +0.35 for immigration to +1.38 for social benefits (respectively, 11% and 45% of the standard deviation of the dependent variable). This confirms H3: respondents are more supportive of deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition when they know that their position is shared by their co‐nationals. In other words, their support for the institution is at least partially by an expected favourable policy outcome.Footnote 15

Discussion

Amid declining trust in politicians and representative democracy (Van der Meer, Reference Van der Meer2017), deliberative citizens’ assemblies have gained popularity among academics and practitioners as potential cures of the so‐called ‘democratic malaise’ (Reuchamps & Suiter, Reference Reuchamps and Suiter2016). Among others, they are expected to reconcile the disenfranchised of representative democracy (Fung, Reference Fung2006; Zittel & Fuchs, Reference Zittel and Fuchs2006). With this paper, we evaluate whether this new institution can deliver its promises. To do so, we rely on a comparative survey with large samples representative of the population of 15 West European countries. We evaluate whether deliberative citizens’ assemblies attract support from the ‘right’ citizens (i.e., the dissatisfied) and whether this support is motivated by the ‘right’ reason (i.e., support for the institution itself rather than the expected policy outcome). In other words, we evaluate who supports the deliberative citizens’ assemblies and why.

On the first question, we find that support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies comes first and foremost from those who are politically dissatisfied. The supporters do not feel politically competent and hold negative views about political elites. They also tend to have a low‐education background. This finding is the same for all countries covered in the survey regardless of how frequent deliberative citizens’ assemblies are in those countries. Interestingly, this means that the profile of the supporters is the opposite of the profile of those who generally accept to participate in deliberative assemblies (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, van der Kolk, Carty, Blais and Rose2011; Jacquet, Reference Jacquet2017). This finding is in line with the one of Rojon and Pilet (Reference Rojon and Pilet2021) who show that although disengaged citizens are generally in favour of deliberative democracy, they would rather let other citizens whom they perceive as more politically competent participate in these forums. Nonetheless, our study suggests that deliberative citizens’ assemblies have the potential of reconciling the politically disengaged.

On the second question, we find that support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies is at least partly driven by citizens’ expectations of a favourable outcome. When respondents know that their preference about a certain policy issue is shared by most of their co‐nationals, they anticipate that these citizens’ assemblies will lead to their preferred policy because the participants are randomly drawn from the population at large, and thus support it. This finding concurs with those of Werner (Reference Werner2020), Landwerh and Harms (Reference Landwehr and Harms2020) and van der Does and Kantorowicz (Reference Van der Does and Kantorowicz2021) who find that citizens’ support for other institutions that give a greater role to citizens in policymaking is at least partly driven by self‐interest. In turn, this means that deliberative citizens’ assemblies, just like other political institutions, will need to address the issue of ‘losers’ consent’ (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005). Non‐participating citizens might not accept the resulting decisions or recommendations, as their support seems to be contingent on the favourability of the policy outcome.

Overall, this paper brings an important contribution to the literature on deliberative democracy. Many consider that the institution would give ‘citizens a more permanent and meaningful role in shaping the policies affecting their lives’ (OECD, 2020, p. 1), and indeed there is a vast literature that shows promising results along this line. By contrast, our results show that although deliberative citizens’ assemblies have the potential to re‐engage the disenfranchised, their supporters are not (yet) motivated by the institution itself and its collective benefits. This is at least the situation in Western Europe at the time of conducting our survey in 2020 (see Fishkin, Reference Fishkin2018, for a discussion of the state of citizens’ deliberative assemblies in other parts of the world). Although deliberative citizens’ assemblies are increasingly used in these countries, the public does not seem to be sufficiently familiar with the institution's collective benefits for the political system.

Acknowledgements

This project was led by Jean‐Benoit Pilet and Damien Bol. An earlier version of this paper has been presented at seminars of the Centre for the Study of Deliberative Democracy of the University of Canberra, the Åbo Akademi University, Centre for the Study of Democratic Innovations of the Goethe Universität Frankfurt, the Centre for Political Science and Comparative Politics of UC Louvain. The authors would like to thank all the participants of these seminars for their helpful comments and suggestions. The study has received financial support from the European Research Council (ERC Consolidator Grant) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 772695) for the project CURE OR CURSE?/POLITICIZE.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this article.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

A Appendix

B Appendix

C Appendix

D Appendix

Note: Entries are marginal effects from logit regressions predicting treatment assignment. Standard errors are in parentheses.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

E Appendix

The experimental vignette consists in exposing a random sample of respondents to the proportion of their co‐nationals supporting each of the three policy issues covered in the study (European integration, social benefits, immigration). Right after being exposed to this vignette (or not), we asked respondents to guess what is the share of the population that supports each of the three policy issues. The raison d’être of this question is to make sure that they noticed the treatment and updated their beliefs accordingly. We did not exactly ask the same policy question as the one in the vignette though, as we envisioned that it would feel odd for respondents. We asked slightly different questions. Their wordings were: (European integration) ‘In your opinion, what share of the population of [COUNTRY] thinks that the country should remain in the European Union’; (Social benefit) ‘In your opinion, what share of the population of [COUNTRY] thinks social benefits should be increased’; (Immigration) ‘In your opinion, what share of the population of [COUNTRY] thinks that the country should not accept new migrants’.

The figure below shows that the correlations between the actual and perceived share of the population supporting the policy issue are always positive, suggesting that respondents were able to correctly estimate whether their position is shared by their fellow citizens. Yet, this correlation is stronger in the treatment group than in the control group, which confirms that they updated their belief in view of the experimental vignette.

Note that the positive correlation is not stronger in the treatment group for one policy issue: immigration. We attribute this to the question itself. The one asking respondents about their perception of the share of their fellow citizens supporting the policy issue was asked the other way round compared to the treatment group (share of population thinking that the country should NOT accept new migrants vs. share of population thinking that immigrants are economically beneficial for the country). Yet, we do believe that this treatment, just like others, made respondents update their beliefs about the share of the population with positions aligned to them.

F Appendix

Note: Entries are odds ratios (two first columns) from multinomial regressions predicting evaluation of deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition in general (0–3 negative, 4–6 neutral, 7–10 positive). Entries are coefficient estimates (last column) from OLS regressions predicting the evaluation of deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition in general with respondents from the control group. Standard errors are in parentheses. Engagement = Political competence + Political interest (Cronbach alpha = 0.47). Enragement = Satisfaction with democracy + Evaluation of political elites (Cronbach alpha = 0.43).

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

G Appendix

Note: Entries are coefficient estimates from OLS regressions predicting support for citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition (per policy). Standard errors are in parentheses.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01 (two‐tailed).

H Appendix

Note: Entries are coefficient estimates (last column) from OLS regressions predicting evaluation of deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition in general by country.

Abbreviations: AT, Austria; BE(FR), Belgium (French); BE(FL), Belgium (Flanders); DK, Denmark; FI, Finland; FR, France; DE, Germany; EL, Greece; IE, Ireland; IT, Italy; NL, the Netherlands; NO, Norway, PO, Portugal; ES, Spain; SE, Sweden; UK, the United Kingdom.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01 (two‐tailed).

I Appendix

Note: Entries are coefficient estimates from OLS regressions predicting support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies selected through sortition in general. Standard errors clustered by country are in parentheses. Interactions are between the variable number of deliberative citizens’ assemblies in the country and other independent variables.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01 (two‐tailed).