Introduction

The year 2024 marked the escalation of the war that broke out on 7 October 2023. The Gaza war continued, leading to widespread protests across the country demanding a ceasefire and the release of Israeli hostages. During 2024, Israel and Hezbollah engaged in their most intense conflict since 2006. Following Hezbollah's attacks in support of Hamas, Israel launched a ground invasion of southern Lebanon on 1 October 2024, aiming to dismantle Hezbollah's military infrastructure. Hezbollah's rocket and drone attacks led to the deaths of over a hundred civilians and soldiers, with around 60,000 residents evacuated from northern regions. A US-brokered ceasefire was implemented on 27 November, but sporadic clashes and mutual accusations of violations have persisted.

In April, Israel and Iran engaged in direct military confrontations for the first time. After an Israeli airstrike killed Iranian generals in Damascus, Iran launched a massive retaliatory attack involving over 300 drones and missiles, most of which were intercepted. Tensions flared again in October when Iran fired another barrage of missiles at Israel, citing retaliatory motives. In 2024, Iran-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen launched drone and missile attacks on Israeli territory, including a deadly strike on Tel Aviv in July. In response, Israel carried out retaliatory airstrikes on Houthi targets in Yemen.

Amid the intensifying war and the government's continued refusal to launch a comprehensive and legally binding investigation into the events of 7 October, government instability deepened throughout 2024. Debates over the next stages of the war further fuelled tensions within the coalition, which underwent three major changes during the year. First, Gideon Sa'ar, the leader of New Hope—The National Right, exited the coalition while splitting from the National Unity alliance (March 2024). Second, Benny Gantz and the National Unity faction departed from the coalition (June 2024), and third, Sa'ar and New Hope—The National Right rejoined the coalition (September 2024). The government's handling of the war sparked massive public protests, with hundreds of thousands taking to the streets to demand the immediate return of the hostages from Gaza.

Election report

There were no parliamentary elections in Israel in 2024. However, municipal elections were held on 27 February for the country's cities, local councils, and regional councils. Initially scheduled for October 2023, the elections were postponed due to the war. In Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, incumbent mayors Moshe Leon and Ron Huldai were re-elected. In Haifa, former mayor Yona Yahav defeated the incumbent, Einat Kalisch-Rotem, regaining his previous position. We note here that local elections in Israel, while politically salient, do not reflect national politics or public (dis)approval of the national government. This is because local parties and politicians are rarely affiliated with parties in the Knesset, and the composition of local coalitions does not mirror the nationwide political divisions (Tuttnauer & Friedman Reference Tuttnauer and Friedman2020).

In local councils near the Gaza border, where residents were evacuated due to the war, elections were set to be held on 19 November 2024 (Central Elections Committee 2024). Elections in Kiryat Shmona, Shlomi, and several other regional councils in the north were postponed to 18 February 2025 (Ministry of Interior 2024).

Cabinet report

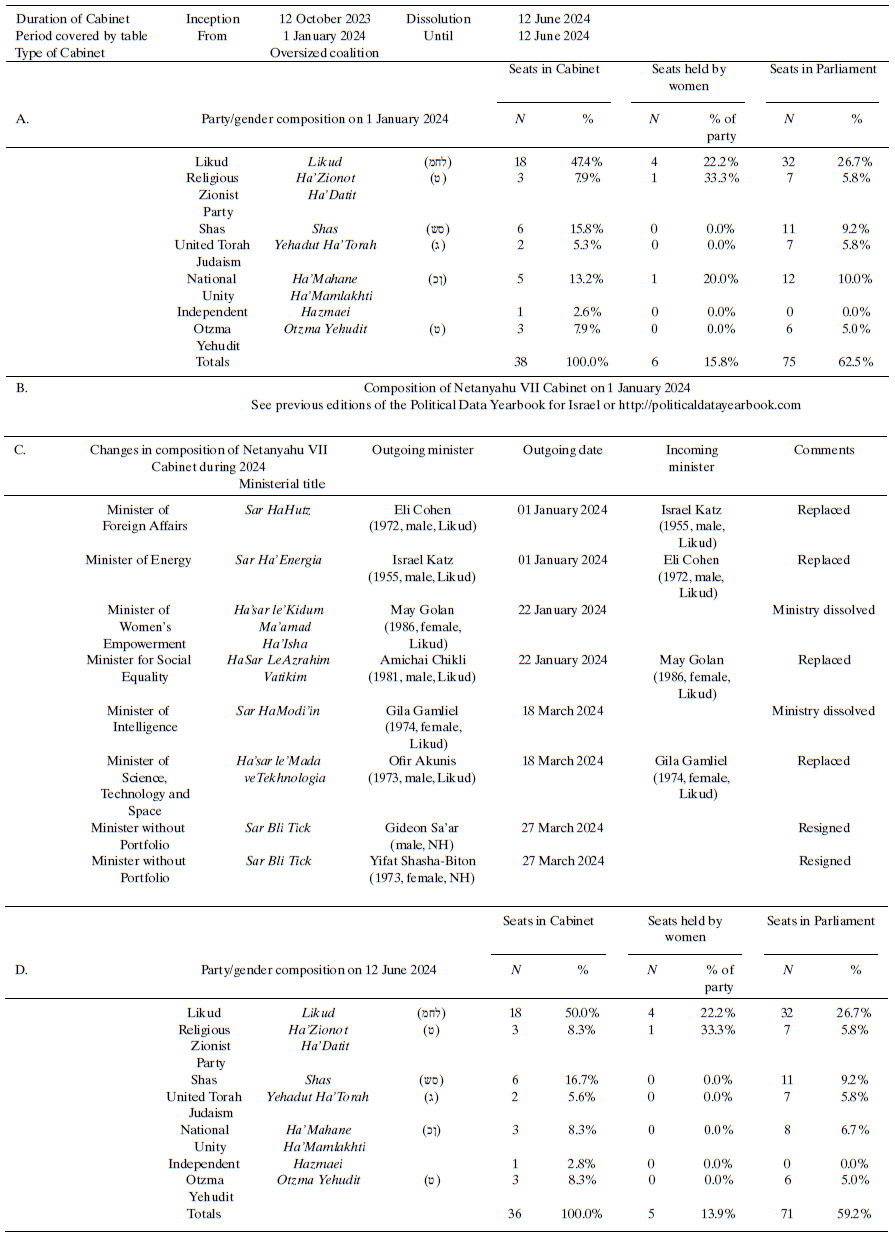

Netanyahu VII—The existing Cabinet at the beginning of 2024 (January–March 2024)

At the start of 2024, Netanyahu's Cabinet included members from his right-wing and religious coalition partners, alongside the National Unity party led by Benny Gantz, which joined during the early stages of the Gaza war in late 2023 (see Table 1). The war Cabinet,Footnote 1 formed to manage the conflict, included Netanyahu, Yoav Gallant, and Benny Gantz, along with Gadi Eisenkot and Ron Dermer as observers (Yosef & Gotkine Reference Yosef and Gotkine2024), representing a relatively broad political spectrum (see Zur & Bakker Reference Zur and Bakker2025, for the policy positions of the parties). In March 2024, Gideon Sa'ar left the National Unity alliance and formed a new faction, the National Right. He then left the government, citing disagreements over the handling of the war and his exclusion from the war Cabinet. His departure signaled growing cracks within the unity government but did not immediately dismantle the broader coalition structure.

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Netanyahu VII in Israel in 2024

Note: During 2024, PM Nethanyahu appointed Ron Dermer as an independent Cabinet member.

Source: Knesset Website (2024; https://main.knesset.gov.il/EN/mk/government/Pages/governments.aspx?govId=37).

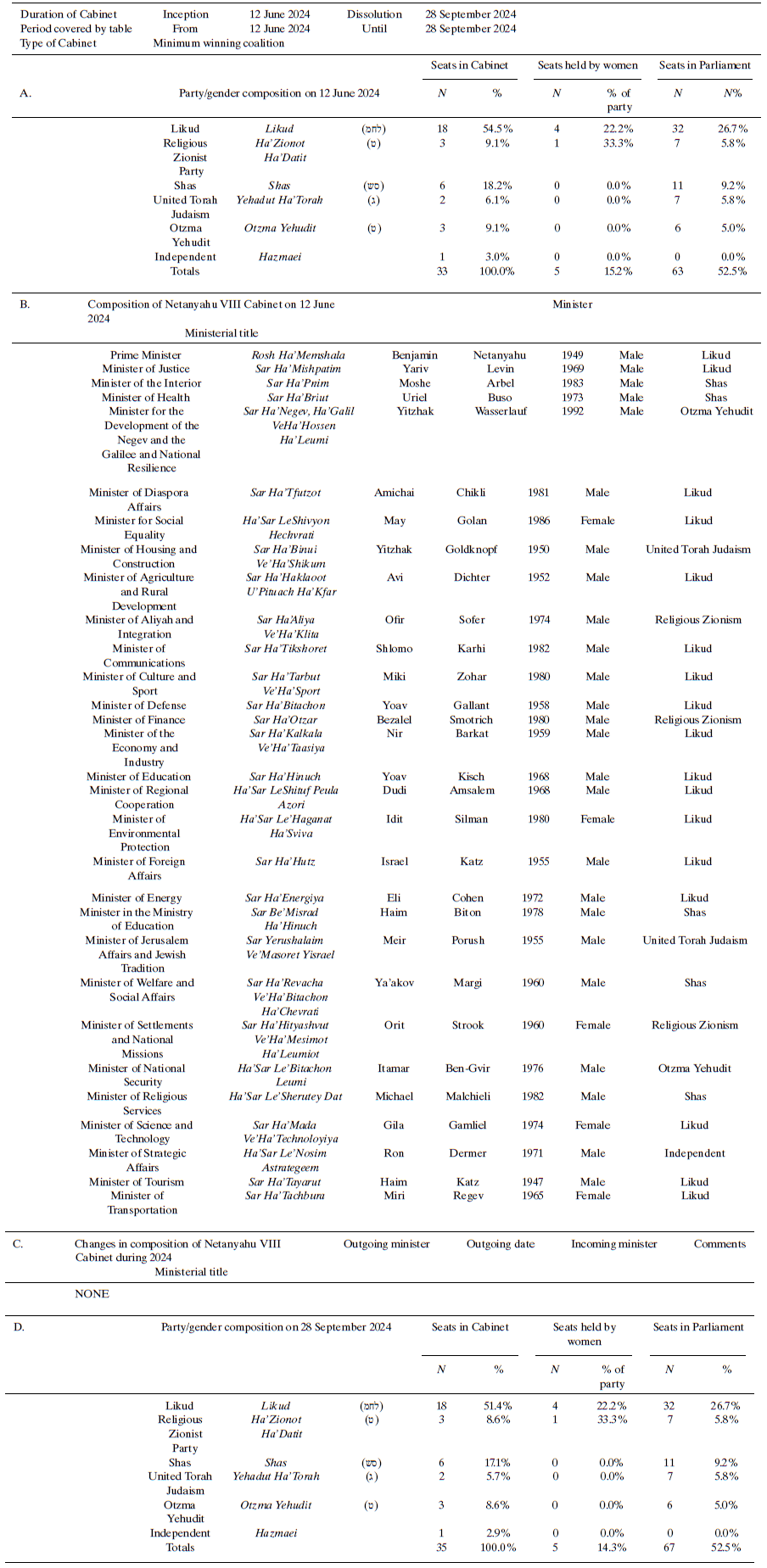

Netanyahu VIII–The National Unity's Exit from the Coalition (June – September 2024)

On 9 June 2024, Benny Gantz, Gadi Eisenkot, and Hili Tropper announced their resignation from the Cabinet, accusing Netanyahu of failing to present a post-war strategy for Gaza (Azoulay Reference Azoulay2024). In response, Netanyahu dissolved the war Cabinet on 17 June (Knell & Gritten Reference Knell and Gritten2024). Decision-making shifted back to a narrower inner circle dominated by Netanyahu's original right-wing and ultra-Orthodox partners, notably excluding centrist and moderate voices (see Table 2). This period marked the government's return to a more hardline and internally fragmented posture.

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Netanyahu VIII in Israel in 2024

Note: The “New Hope—The National Right” party split from the “National Unity” party on 13 March and withdrew from the government on 27 March. It then rejoined the government on 29 September.

Source: Knesset Website (2024; https://main.knesset.gov.il/EN/mk/government/Pages/governments.aspx?govId=37).

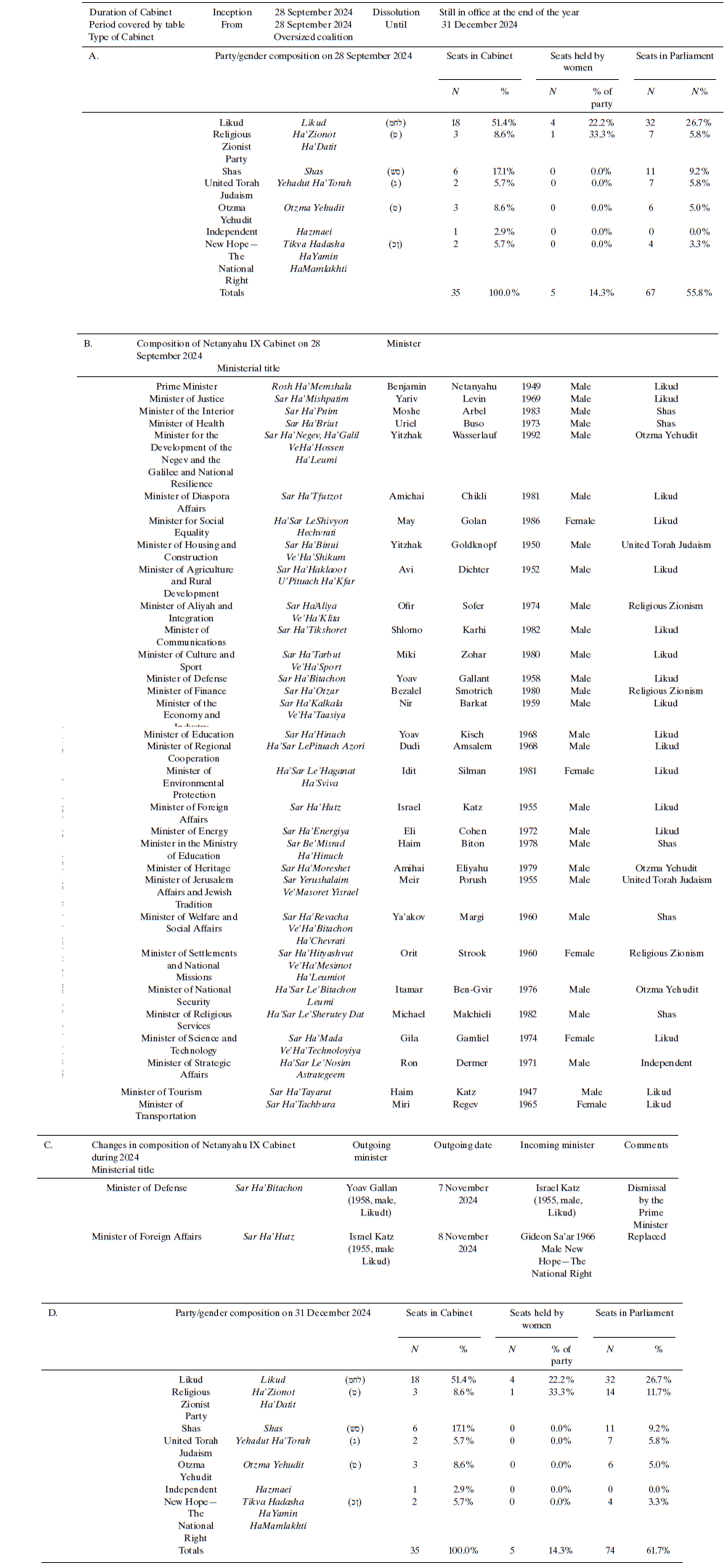

Netanyahu I—The Return of New Hope—The National Right (September 2024 onward):

In September 2024, Gideon Sa'ar and the National Right rejoined the coalition, forming a new agreement with Netanyahu (see Table 3). This reshaped the Cabinet again, giving Sa'ar and his party influence within the government. Sa'ar was appointed a Minister without Portfolio. Later in November, he was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Zeev Elkin (also from the National Right) was appointed Minister without portfolio assigned to the Ministry of Finance. While this move slightly broadened Netanyahu's political base again, the Cabinet remained fundamentally right-wing, facing ongoing internal tensions and external pressure due to the prolonged conflict and economic challenges.

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Netanyahu IX in Israel in 2024

Source: Knesset Website (2024; https://main.knesset.gov.il/EN/mk/government/Pages/governments.aspx?govId = 37).

Another notable change in the Cabinet took place on 5 November 2024, when Netanyahu dismissed Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, citing a breakdown in trust amid ongoing conflicts in Gaza and Lebanon. Gallant attributed his dismissal to disagreements over three critical issues: the exemption of ultra-Orthodox Jews from military service, the urgency of securing a deal to release hostages held by Hamas, and the necessity of establishing a commission to investigate the failures leading to the 7 October attacks (Le Monde 2024). His dismissal was met with widespread criticism from opposition leaders and sparked mass protests across Israel, with demonstrators viewing the move as politically motivated and detrimental to national security. Gallant's replacement by Foreign Minister Israel Katz signaled a potential shift toward a harder line in Israel's defense policy. In the broader context of Israeli politics, Gallant's dismissal underscored the deepening divisions within the government and the challenges facing Netanyahu's leadership amid escalating military conflicts and internal dissent.

Please note that the Cabinet changes described above follow the Political Data Yearbook Cabinet definitions, but they are all considered part of the Israeli 37th Government, and Netanyahu's 6th elected government, because Israel counts new governments (Cabinets) only after the investiture vote, not after changes in party composition.

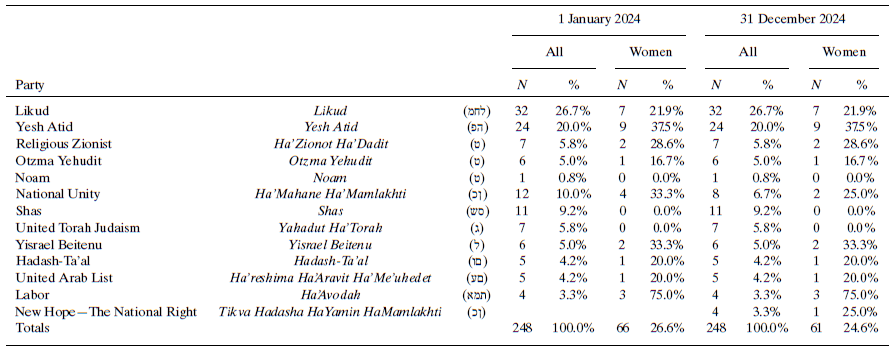

Parliament report

After the 2022 elections, the Religious Zionism list, an alliance of three right-wing parties (Religious Zionism, Otzma Yehudit, and Noam), split shortly after the election, as had been expected. In 2024, the three factions continued to operate independently within the Knesset.

In addition, a major party split occurred in 2024 when Gideon Sa'ar announced on 12 March that his party, New Hope—The National Right, left the National Unity alliance, citing disagreements over the conduct of the Gaza war and his exclusion from the war Cabinet (see Table 4). He criticized National Unity leader Benny Gantz for not adequately representing his hawkish stance on military operations. On 13 March, the Knesset Committee approved the request by faction members—Gideon Sa'ar, Yifat Shasha-Biton, Ze'ev Elkin, and Sharren Haskel—to split from the National Unity and to establish the “National Right” faction.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of Parliament (Knesset) in Israel in 2024

Notes:

1. Otzma Yehudit and Noam ran on the Religious Zionist Party list (as a pre-electoral alliance); the entire list won 14 seats, with Otzma Yehudit winning six and Noam winning one. The alliance split on 20 November 2022.

2. New Hope—The National Right ran on the National Unity list (as a pre-electoral alliance). The alliance split on 13 March 2024.

Sources: Central Election Commission website (2022; https://votes25.bechirot.gov.il/); Knesset Website, 2024 (https://main.knesset.gov.il/about/history/pages/knessethistory.aspx?kns=25;https://main.knesset.gov.il/en/mk/apps/mklobby/main/current-knesset-mks/knesset-women).

Political party report

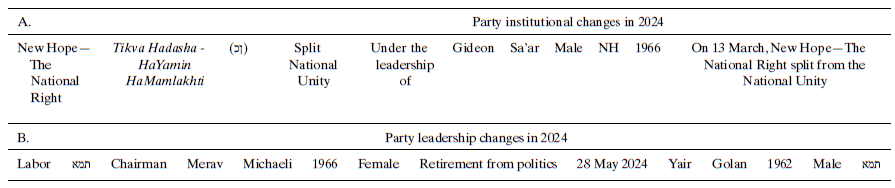

In May 2024, Yair Golan was elected leader of the Labour Party, securing 95.15 per cent of the vote in the party's internal elections. During his campaign, Golan pledged to unify Labour with Meretz, a party that failed to pass the electoral threshold in the 2022 elections for the first time since its founding in 1992 (as a Left-wing alliance). Following his election, the two parties agreed to run on a joint list in the next national elections and to hold unified internal primaries to determine their candidate list. Consequently, the Labour Party changed its name to “The Democrats.” Note that Golan is not a member of the Knesset, while Merav Michaeli, the former Labour leader, continued to serve as a Member of the Knesset (MK).

In March 2024, Gideon Sa'ar announced that his party, “New Hope—the National Right,” was leaving the National Unity alliance (Table 5). The next day, the Knesset Committee approved the split, formally establishing the “National Right” faction. Sa'ar and the National Right advocate a harder, security-focused approach, favoring aggressive military action. While supportive of military efforts, Benny Gantz and National Unity promote a more moderate and pragmatic strategy that balances force with broader political and international considerations.

Table 5. Changes in political parties in Israel in 2024

Note: New Hope was founded in December 2020, competed independently in the 2021 election and in the National Unity alliance in 2022.

Source: Israeli Democratic Institute (2024; https://en.idi.org.il/israeli-elections-and-parties).

On 28 March 2024, the leader of the opposition and the second largest party in the Knesset (Yesh Atid), Yair Lapid, was re-elected as the party leader. He narrowly won, by a 52.5 per cent to 47.5 per cent margin, against former deputy director of the Mossad and a Member of the Knesset since 2019, Ram Ben-Barak.

Institutional change report

The political developments in 2024 reflect a dynamic and contentious period in Israel's constitutional landscape, highlighting ongoing debates over the Judiciary's role, the balance of power among branches of government, and safeguarding democratic principles. These tensions were set in motion early in the year, when on 1 January, the Supreme Court, by a majority opinion, struck down an amendment to the Basic Law: the Judiciary, which had barred judicial review of the reasonableness of decisions made by the government, the Prime Minister, and Ministers. In its landmark ruling, the Court established that it holds the authority to review Basic Laws in rare and extreme cases where the Knesset exceeds its constituent power. This unprecedented decision invalidated Amendment No. 3 to the Basic Law and marked a constitutional turning point.

In response, the coalition pursued a series of legislative initiatives to expand political control and curb judicial oversight. While public backlash, legal challenges, and internal disagreements prevented sweeping reforms, several new laws were enacted in 2024.Footnote 2 Although none of these introduced significant changes to Israel's Basic Laws,Footnote 3 they signaled a broader direction toward consolidating executive power and reshaping the institutional balance, leading V-Dem to degrade Israel's status to an Electoral Democracy after over 50 years as a Liberal Democracy (Nord et al. Reference Nord2024).

Issues in national politics

In 2024, Israeli national politics were dominated by the ongoing and escalating war in Gaza and on the northern front, which profoundly impacted the political climate, strained state institutions, and amplified long-standing societal tensions. The prolonged conflict led to an unprecedented national mobilization, with tens of thousands of reservists called up for extended periods. As the months wore on, growing frustration emerged over the burden placed on reservists and their families, especially amid concerns about the lack of a clear post-war strategy. Public debate intensified over fairness and equality in military service, reigniting the polarizing issue of exemptions for ultra-Orthodox yeshiva students. The government faced mounting pressure, from both within the coalition and the broader public, to pass legislation that would either enforce or reform conscription policies, but attempts to reach a consensus repeatedly stalled.

Another focal point was the fate of the Israeli hostages still held in Gaza. A broad segment of the public demanded a comprehensive deal to bring them home, even at the cost of releasing Palestinian prisoners or accepting a final ceasefire. These demands clashed with hawkish voices in the government, who prioritized continuing military operations to dismantle Hamas. This division created deep rifts both within the coalition and between the government and large segments of Israeli society, who held weekly protests calling for a hostage deal and a more humane war policy.

Alongside these debates, there were growing calls for a national commission of inquiry into the failures that led to the 7 October attacks. Many Israelis across the political spectrum demanded accountability from military, intelligence, and political leaders, including Prime Minister Netanyahu. However, Netanyahu resisted investigation efforts, arguing that such inquiries should only be launched after the war ends.

Overall, Israeli politics in 2024 was characterized by rising internal polarization, deep public distrust in political leadership, and the growing sense that the country faced an external war and a critical reckoning over its democratic norms, social cohesion, and national priorities.

The economy

In 2024, Israel's economy faced significant challenges due to ongoing military conflicts, particularly in Gaza and Lebanon. GDP increased by only 0.9 per cent, compared to 2023, and business output contracted by 0.8 per cent (Bank of Israel 2025). Over the course of the year, there were signs of partial recovery in economic activity, and by the end of the year, the financial markets showed significant improvement. However, the economy has yet to return to its pre-war state, and the effects of the war are expected to continue for many years (Bank of Israel 2025). The war's damage to aggregate activity was primarily due to a decline in labor supply, mainly resulting from the ban on the entry of Palestinian workers, the mobilization of reservists, and the difficulties faced by workers from conflict areas in reaching their workplaces.

Inflation reached 3.2 per cent this year, slightly above the upper boundary of the target range and higher than last year's rate, contrary to the global trend of moderating inflation rates. Government spending on defense and civilian needs rose sharply due to the war. During the year, the 2024 budget was reopened three times to allow for additional allocations, most of which were war-related. The sharp expenditure rise was funded mainly by increasing the budget deficit, which reached 6.8 per cent of GDP this year (Bank of Israel 2025).

Reflecting these challenges, all three major rating agencies downgraded Israel's credit ratings. Moody's downgraded Israel's rating from A1 to A2 in February and further to Baa1 in September, citing heightened political and security risks (Moody's Ratings 2024a, 2024b). S&P lowered Israel's rating from AA− to A+ in April and again to A in October, warning of fiscal and security pressures (S&P Global 2024a, 2024b). In August, Fitch downgraded Israel from A+ to A with a negative outlook, emphasizing the impact of prolonged conflict and regional instability (Fitch Ratings 2024).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Lior Shvarts and Iaara Asaf for excellent research assistance. We also thank the editors and the anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments and suggestions. This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant No. 2976/21).

[Correction added on 25 October 2025, after first online publication: The Acknowledgments section has been included in this version.]