Introduction

In most herbivorous insects, host plant location and selection are essential for insect survival and fitness because host plants provide food, shelter, and oviposition sites. Insects depend heavily on olfaction for sensing their surrounding environment (Greenfield Reference Greenfield and Greenfield2002) and have developed a complex olfactory system that is extremely sensitive to the detection of behaviourally relevant volatiles (Hansson Reference Hansson2002; Wyatt Reference Wyatt and Wyatt2014; Dekker and Barrozo Reference Dekker, Barrozo, Allison and Cardé2016). Plant volatile compounds have chemical properties that allow them to travel metres away from the source (Pichersky et al. Reference Pichersky, Noel and Dudareva2006; Baldwin Reference Baldwin2010), and the location and selection of host plants at a distance partially result from the detection of plant volatile chemical cues by the insects’ well-developed olfactory system. Herbivorous insects may also use habitat odour cues (e.g., general volatile conifer terpenoids, including α-pinene) to facilitate host location (i.e., to locate general areas where hosts are most likely to be found; Webster and Cardé Reference Webster and Cardé2017). Differences in the composition and ratios of plant volatile compounds allow insects to discriminate host plants from nonhost plants, to find appropriate host plants within diverse vegetation patches, to determine the nutritional quality of host plants, and to detect the presence of other insects on a host plant (Dicke and Baldwin Reference Dicke and Baldwin2010; Bruce and Pickett Reference Bruce and Pickett2011).

Insect mate location generally involves the use of species-specific pheromones (Thornhill and Alcock Reference Thornhill, Alcock, Thornhill and Alcock1983; Greenfield Reference Greenfield and Greenfield2002). Increasing evidence suggests that plant volatiles also play an additional, important role in insect mate location because mating in some species occurs on host plants (Anderson and Anton Reference Anderson and Anton2014). Herbivorous insects have developed multiple strategies that integrate host plant chemicals and sex pheromones to optimise mating and reproduction (Landolt and Phillips Reference Landolt and Phillips1997; Reddy and Guerrero Reference Reddy and Guerrero2004; Xu and Turlings Reference Xu and Turlings2018). For example, males of many insect orders can use host plant volatiles released during female or larval feeding activity as cues for mate location (Ruther et al. Reference Ruther, Reinecke, Thiemann, Tolasch, Francke and Hilker2000; Tooker et al. Reference Tooker, Koenig and Hanks2002; Estrada and Gilbert Reference Estrada and Gilbert2010). Some species can sequester host plant chemicals during the larval or adult stage to use as sex pheromones or sex pheromone precursors (Hartmann et al. Reference Hartmann, Theuring and Bernays2003, Reference Hartmann, Theuring, Beuerle and Bernays2004; Fonseca et al. Reference Fonseca, Vidal and Zarbin2010; Zarbin et al. Reference Zarbin, Fonseca, Szczerbowski and Oliveira2013). In some species of Coleoptera, host plant volatiles have been reported to stimulate the release of pheromones (Jaffé et al. Reference Jaffé, Sánchez, Cerda, Hernández, Jaffé and Urdaneta1993; Lextrait et al. Reference Lextrait, Biémont and Pouzat1995; Pineda-Ríos et al. Reference Pineda-Ríos, Cibrián-Tovar, Hernández-Fuentes, López-Romero, Soto-Rojas and Romero-Nápoles2021) or have a synergistic or additive effect in the attractivity of sex pheromones (Ginzel and Hanks Reference Ginzel and Hanks2005; Hanks and Millar Reference Hanks and Millar2016; Hanks and Wang Reference Hanks, Wang and Wang2017).

In the genus Monochamus Dejean (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), the compound monochamol has been reported to be a pheromone or pheromone attractant for at least 14 species (Pajares et al. Reference Pajares, Álvarez, Ibeas, Gallego, Hall and Farman2010, Reference Pajares, Álvarez, Hall, Douglas, Centeno and Ibarra2013; Teale et al. Reference Teale, Wickham, Zhang, Su, Chen and Xiao2011; Allison et al. Reference Allison, McKenney, Millar, McElfresh, Mitchell and Hanks2012; Fierke et al. Reference Fierke, Skabeikis, Millar, Teale, McElfresh and Hanks2012; Wickham et al. Reference Wickham, Harrison, Lu, Guo, Millar, Hanks and Chien2014; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Lee, Lee, Choi, Jung and Jeon2017, Reference Lee, Lee, Lee, Jung, Kwon and Huh2018; Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, Guignard, Smith and Allison2024). Monochamol is an aggregation-sex pheromone (sensu Cardé Reference Cardé2014) produced by males that mediates aggregation of both males and females on larval hosts, where mating usually occurs. Three species of the genus, namely M. maculosus (Haldeman) (previously known as M. mutator LeConte; Bousquet et al. Reference Bousquet, Laplante, Hammond and Langor2017), M. notatus (Drury), and M. scutellatus (Say), are sympatric and partially synchronic in Ontario, Canada (Bousquet et al. Reference Bousquet, Laplante, Hammond and Langor2017), and have been reported to use the same compound as a pheromone or putative pheromone attractant (Fierke et al. Reference Fierke, Skabeikis, Millar, Teale, McElfresh and Hanks2012; Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, Guignard, Smith and Allison2024). These species have also been reported to use the same tree species in similar physiological conditions (i.e., severely stressed or recently killed trees of the genus Pinus Linnaeus, Picea Miller, Abies Miller, and Larix Miller (all Pinaceae)) as mating and oviposition sites (Akbulut and Stamps Reference Akbulut and Stamps2011; Akbulut et al. Reference Akbulut, Togashi, Linit and Wang2017). Although pheromone parsimony in this genus would make sympatric species susceptible to cross-attraction, hybridisation between M. scutellatus, M. maculosus, and M. notatus in the field seems rare.

Host location and acceptance in the Cerambycidae are mediated by chemical cues (Allison et al. Reference Allison, Borden and Seybold2004). Consequently, specific host volatile cues could contribute to the reproductive isolation of Monochamus species. In fact, the addition of α-pinene, a volatile emitted by conifer trees, to synthetic monochamol in field trapping experiments has a synergistic or additive effect on the attraction of many Monochamus species (Pajares et al. Reference Pajares, Álvarez, Ibeas, Gallego, Hall and Farman2010; Allison et al. Reference Allison, McKenney, Millar, McElfresh, Mitchell and Hanks2012; Fierke et al. Reference Fierke, Skabeikis, Millar, Teale, McElfresh and Hanks2012; Macias-Samano et al. Reference Macias-Samano, Wakarchuk, Millar and Hanks2012; Ryall et al. Reference Ryall, Silk, Webster, Gutowski, Meng and Li2015; Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, Guignard, Smith and Allison2024). However, variation in the production of secondary metabolites (e.g., terpenes) between different genera and species of conifers exists (Kopacyk et al. Reference Kopaczyk, Warguła and Jelonek2020). Host species preference for adult feeding and oviposition has been reported in Monochamus galloprovinciallis (Olivier) (Naves et al. Reference Naves, De Sousa and Quartau2006a; Koutroumpa et al. Reference Koutroumpa, Sallé, Lieutier and Roux-Morabito2009) and seems to be related to the reproductive potential of female beetles (Akbulut Reference Akbulut2009). Females of M. scutellatus have been reported to lay more eggs on black spruce, Picea mariana (Miller) Britton et al. (Pinaceae), than on jack pine, Pinus banksiana Lambert (Pinaceae), and M. scutellatus larvae seem to develop faster on black spruce than on jack pine (Breton et al. Reference Breton, Hébert, Ibarzabal, Berthiaume and Bauce2013). In addition, adult body size and mass in some Monochamus species seem to vary with host species (Naves et al. Reference Naves, De Sousa and Quartau2006a, Reference Naves, De Sousa and Quartau2006b; Togashi and Appleby Reference Togashi and Appleby2023), and advantages of size in both adult and larval competition over resources have been reported in the genus (Hughes and Hughes Reference Hughes and Hughes1987; Victorsson and Wikars Reference Victorsson and Wikars1996; Anbutsu and Togashi Reference Anbutsu and Togashi1997a).

Niche partitioning between sympatric species is well documented in bark beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). The height at which Scolytinae species fly during dispersal seems related with the height of tree structures they attack (Wood Reference Wood1982; Ulyshen and Hanula Reference Ulyshen and Hanula2007), and colonisation of host trees by two or more species seems to affect their spatial distribution in the bole (Paine et al. Reference Paine, Birch and Švihra1981; Safranyik et al. Reference Safranyik, Linton and Shore2000; Ayres et al. Reference Ayres, Ayres, Abrahamson and Teale2001). In this context, pheromones appear to play a role in defining the sequence and patterns of host aggregation and colonisation by more than one Scolytinae species because the presence of species-specific pheromone signals can either enhance or inhibit heterospecific attraction response to specific sections of a tree (Paine et al. Reference Paine, Birch and Švihra1981; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Payne and Birch1990; Ayres et al. Reference Ayres, Ayres, Abrahamson and Teale2001). Dodds (Reference Dodds2014) hypothesised that niche partitioning in Monochamus may occur in a similar way as it does in Scolytinae to minimise competition for mates, for oviposition resources, or for both.

The abundance of sympatric Cerambycidae species has been reported to differ across the vertical strata of the forest canopy, including species of the genus Monochamus (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Poland, McCullough and Millar2012; Sweeney et al. Reference Sweeney, Hughes, Webster, Kostanowicz, Webster, Mayo and Allison2020; Vargas-Cardoso et al. Reference Vargas-Cardoso, Toledo-Hernández, Corona-López, Corona-Lopéz, Flores-Palacios and Figueroa-Brito2023). Dodds (Reference Dodds2014) observed that most of Monochamus carolinensis (Oliver) were captured in traps placed in the forest canopy, whereas the majority of M. scutellatus were captured in traps placed in the understorey. Hughes and Hughes (Reference Hughes and Hughes1982) reported that female M. scutellatus prefer larger-diameter sections of host trees for oviposition, and Ryan et al. (Reference Ryan, de Groot and Smith2012) found that the distribution of larvae of M. carolinensis tends to increase slightly in the upper portions of bole sections. In addition, males of M. scutellatus have been reported to engage in aggressive inter- and intra-specific contests to defend portions of hosts that are favoured by females for oviposition (i.e., areas of the trunk with largest circumference) and for access to females (Hughes and Hughes Reference Hughes and Hughes1982, Reference Hughes and Hughes1987; Allison and Borden Reference Allison and Borden2001). However, it remains unclear whether differences in flight patterns among Cerambycidae species relate directly to colonisation behaviour in host trees (Dearborn et al. Reference Dearborn, Heard, Sweeney and Pureswaran2016).

The main objective of the present study was to investigate host and habitat preferences and their potential contribution to reproductive isolation in sympatric populations of three Monochamus spp. – M. scutellatus, M. maculosus, and M. notatus – in the Great Lakes Forest Region of Ontario, Canada. Field experiments were used to test for specific host preferences, vertical distribution across the forest canopy, and spatial distribution within and among lying and standing dead trees. The data were assessed for specific host and habitat preferences that could contribute to their reproductive isolation. It was hypothesised that (1) if the three sympatric Monochamus spp. use host volatiles in addition to pheromones to locate mates and have specific host preferences for mating and reproduction, then specific host volatile components minimise the chances of cross-attraction to monochamol and (2) if the three sympatric Monochamus spp. segregate as adults at the local spatial forest level, tree level, or both, either during mating or oviposition, specific spatial preferences within and between down and standing dead trees can minimise the chances of cross-attraction between these species.

Materials and methods

Study sites

All field experiments were run in two sites located in the Algoma District, Ontario, Canada. The first field site is a private, unmanaged mixed-wood forest of approximately 30 ha located west of Sault Ste Marie, Ontario, Canada (46° 29′ 47.5″ N, 84° 29′ 09.7″ W). The forest is primarily composed of softwood species (∼57%), including white spruce, Picea glauca (Moench) Voss, black spruce, P. mariana, eastern white pine, Pinus strobus Linnaeus, red pine, Pinus resinosa Solander ex. Aiton, jack pine, Pinus banksiana, balsam fir, Abies balsamea (Linnaeus) Miller, tamarack, Larix laricina (Du Roi) K. Koch, and eastern hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (Linnaeus) Carrière, (all Pinaceae) (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry 2020a). The second field site is a crown softwood pine forest stand of approximately 170 ha located north of Thessalon, Ontario (47° 07′ 56.7″ N, 83° 08′ 31.3″ W). This stand is primarily composed of P. banksiana (∼80%) and is located between softwood pine forest stands that had been clearcut (all trees removed) within two years before the experiments using the short-wood method (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry 2020b).

Host-mediated reproductive isolation

Twelve-unit multifunnel traps (Lindgren Reference Lindgren1983) that were coated with Fluon PTFE lubricant to increase the capture rate of attracted beetles (Allison et al. Reference Allison, Wood Johnson, Meeker, Strom and Butler2011, Reference Allison, Graham, Poland and Strom2016) and were equipped with wet collecting cups containing approximately 200 mL of antifreeze were deployed in linear arrays of eight replicate blocks in a clearcut mixed-wood forest in the second field site (47° 07′ 56.7″N, 83° 08′ 31.3″ W). Each block contained four traps hung at 1.5 m height from iron stands fixed into the ground and spaced 30 m apart (n = 32 traps in total). All traps were baited with one bubblecap lure containing synthetic monochamol, and the following treatments were randomly assigned within each replicate block: (1) one mesh bag with no branches or fresh foliage of host trees and one ultra-high release (UHR) α-pinene lure; (2) one mesh bag containing 4.5 kg of branches and fresh foliage of Abies balsamea; (3) one mesh bag containing 4.5 kg of branches and fresh foliage of Pinus banksiana; and (4) one mesh bag containing 4.5 kg of branches and fresh foliage of Picea glauca. Bubblecap lures containing synthetic monochamol (99% purity and release rate of 1.5 mg/day at 30 °C) and UHR α-pinene (98% purity and release rate of 2000 mg/day at 25 °C) were purchased from Synergy Semiochemicals (Delta, British Columbia, Canada). The contents of the mesh bags were prepared one day before their installation on the traps. Branches and foliage of either A. balsamea, P. banksiana, or P. glauca were chopped into small pieces with an electric log splitter (LOGic®, version 120/6; Bell SRL, Reggio Emilia, Italy). Chopped host material (4.5 kg) was placed in a mesh bag and kept at 5 °C until the next morning, when the bags were taken to the field and hung on the traps. All mesh bags containing chopped plant material were replaced weekly.

The traps were inspected weekly during four consecutive weeks from 3 to 27 August 2014. The content of each trap was sieved and placed individually in a Whirl-Pak® bag (710 mL; Whirl-Pak Filtration Group, Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin, United States of America) containing 95% ethanol, transferred to the laboratory, and kept at 5 °C until processed. Captured beetles of the genus Monochamus were sorted and identified to sex and species, using morphological characters (Bousquet et al. Reference Bousquet, Laplante, Hammond and Langor2017).

Species abundance across the vertical strata of the forest canopy

Monochamus spp. abundance across vertical strata of the forest canopy was investigated with a field trapping experiment using 12-unit multifunnel traps (Lindgren Reference Lindgren1983) that were coated with Fluon PTFE lubricant and were equipped with wet collecting cups containing approximately 200 mL of antifreeze and baited with ultra-high release (UHR) α-pinene and bubblecap lures containing synthetic monochamol (purity and release rates as described above in the section, Host-mediated reproductive isolation) purchased from Synergy Semiochemicals (Delta, British Columbia, Canada). Traps were placed at two different heights in the forest vertical strata at the two field sites: traps were hung at approximately 10 m above ground (hereafter, “canopy traps”) and at 1.5 m above ground (hereafter, “understorey traps”). Canopy and understorey traps were placed in the field following a methodology similar to that in Dodds (Reference Dodds2014). To place canopy traps, a Big Shot® launcher (Sherrill Tree, Greensboro, North Carolina, United States of America) was used to shoot a weighted bag tied to a throwline through the lower portion of a branch in the canopy of a tree, facilitating the installation of a double-braided nylon rope with single rope pulley attached to its midpoint. The pulley was raised approximately 10 m above ground and positioned at about a 45° angle from vertical, and a second rope looped around the pulley wheel was used to raise the canopy-level trap and secure the position. Understorey level traps were hung from iron stands fixed into the ground under the canopy traps, so that the understorey trap collection cup was approximately 0.5 m above the ground. At the first field site, six pairs of one canopy trap and one understorey trap each were deployed at least 30 m away from one another. At the second field site, 10 pairs of one canopy trap and one understorey trap each were deployed – seven pairs 250 m away from one another, and three pairs of traps 500 m away from one another.

The traps were inspected weekly during eight consecutive weeks from 9 July to 2 September 2021. The contents of each trap were sieved and placed individually in a Whirl-Pak bag (710 mL) containing 95% ethanol, transferred to the laboratory, and kept at 5 °C until processed. Captured beetles of the genus Monochamus were sorted and identified to sex and species, using morphological characters (Bousquet et al. Reference Bousquet, Laplante, Hammond and Langor2017).

Coarse woody debris assessments

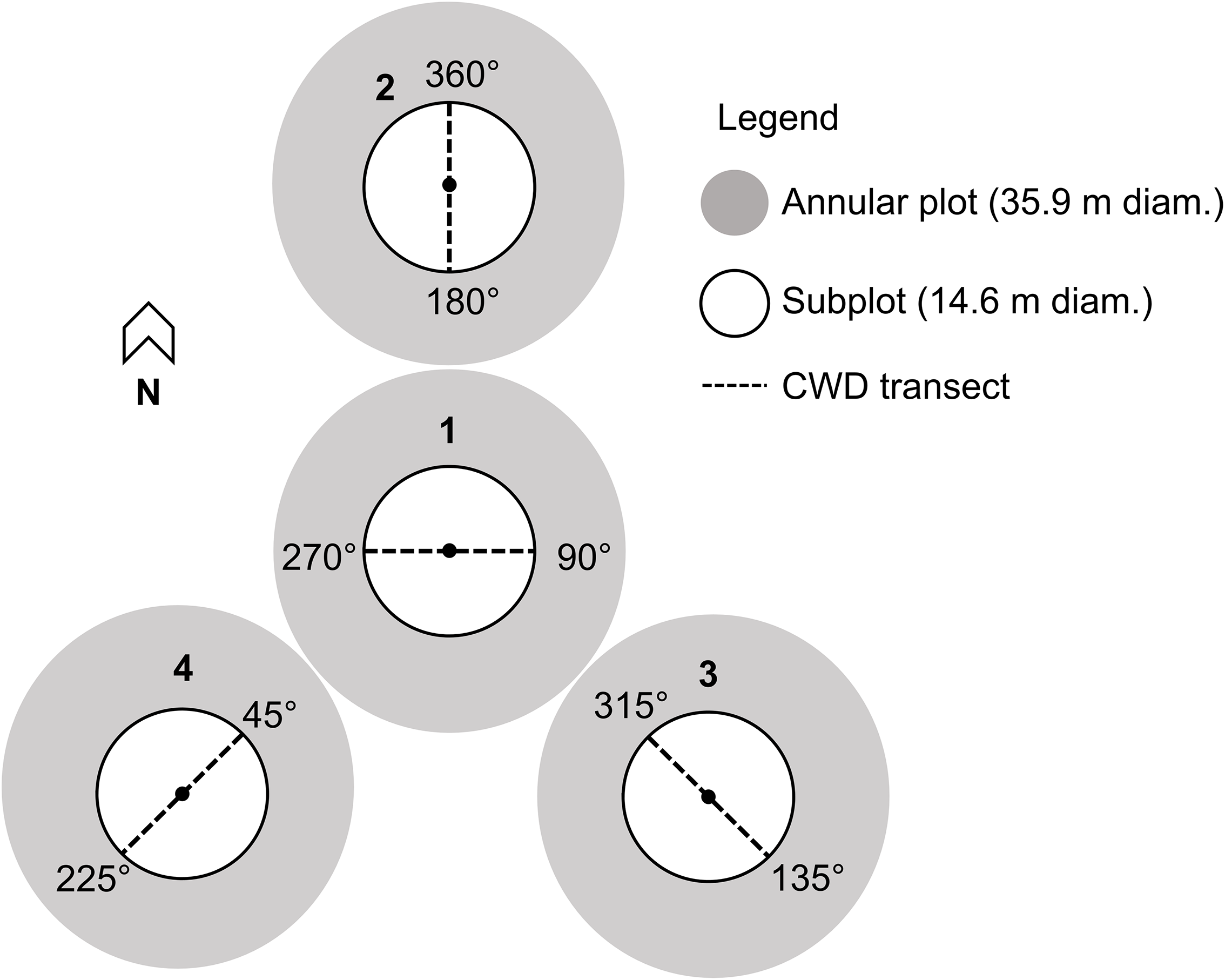

Coarse woody debris assessments were performed in the two field sites. The assessments were performed following the United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service (2019) line-intersect sampling method for forest inventory and analysis, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In this method, linear transects are established in plots, and individual pieces of coarse woody debris are tallied if the plane of the transect intercepts the central axis of the piece. In June 2022, four plots were established in field site #1, and five plots were established in field site #2. Plots were installed adjacent to the locations where canopy and understorey traps were placed in the two sites (nine plots in total). Plot centres were 150 m apart in the first field site and 800 m apart in the second field site.

Figure 1. Coarse woody debris (CWD) sampling design for forest inventory and analysis plots implemented in 2022 (adapted from United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service 2019). The centres of subplots 2, 3, and 4 are 37 m distant from the centre of subplot 1, at azimuths 360° for subplot 2, 120° for subplot 3, and 240° for subplot 4.

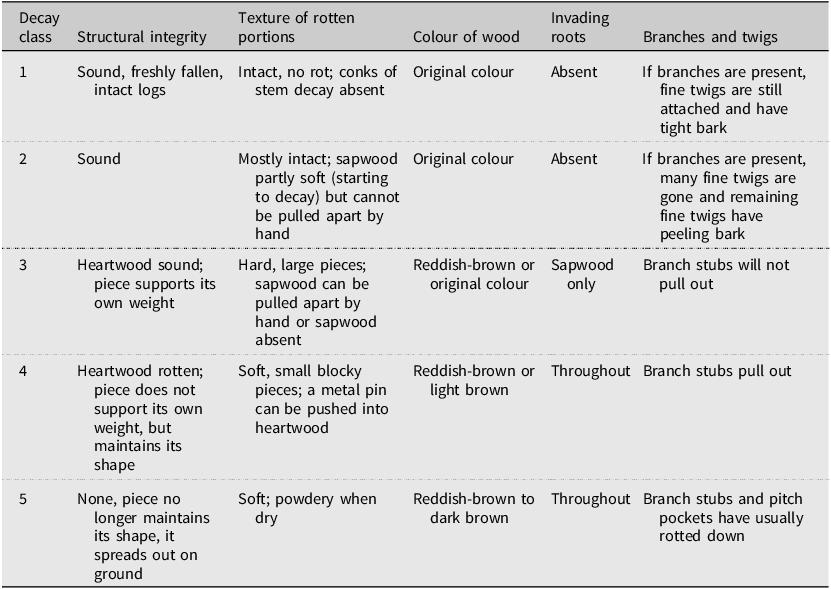

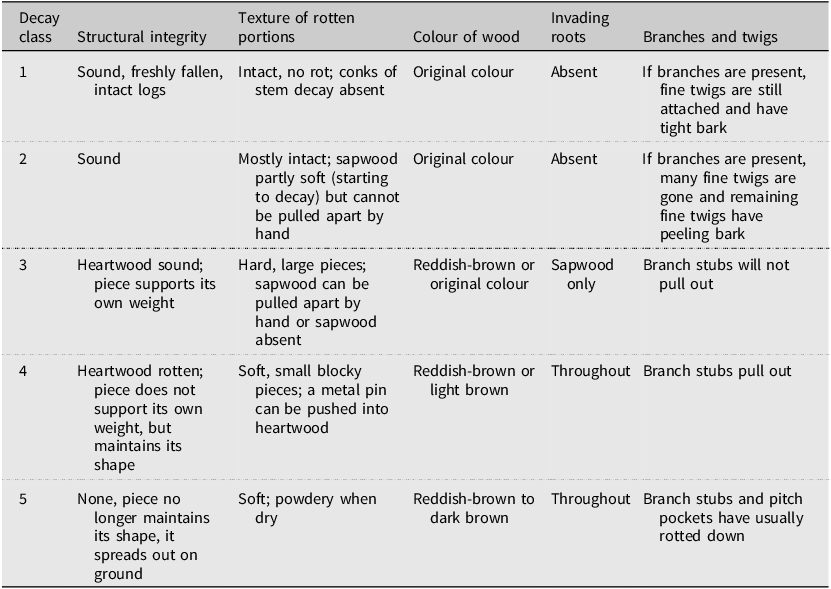

The species, decay class (Table 1), length (m), and diameters (cm) at the small and large ends and at the intersection with the transect were recorded from each piece of down coarse woody debris along transects that met the conditions described in United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service (2019). The species, decay class, and diameter at 1.37 m height of dead standing trees along transects were recorded. Pieces of down coarse woody debris in an advanced stage of decay (decay class 5; Table 1) that intersected transects were not sampled due to difficulties in determining the species and delineating the log on the ground to obtain diameter and length measurements.

Table 1. Classification of the stage of decay for down coarse woody debris pieces (adapted from United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service 2019)

Spatial distribution within and among lying and standing dead trees

Specific spatial distribution within and among host trees was investigated in the two field sites. Between 19 May and 4 June 2021, 10 healthy trees of A. balsamea, P. banksiana, and P. glauca (n = 30 trees total) were selected in the first field site, and 20 healthy trees of P. banksiana were selected in the second field site. We then created 15 lying (hereafter, “logs”) and 15 standing (hereafter, “snags”) dead trees of each host species in the first field site (i.e., five logs and five snags of each species). In the second field site, a total of 10 logs and 10 snags of P. banksiana were created due to this being the predominant host species in the area. Height and diameter at 1.4 m above ground (breast height) of all trees were recorded. After five months, all snags were felled, and 60-cm sections were removed from the 30% (“lower-bole”), 50% (“middle-bole”), and 70% (“upper-bole”) mark of each snag and log, as measured from the tree base. The diameters of the small and large ends of each bole were recorded, metal identification tags were nailed on individual boles, and all bole sections were subsequently transported to the laboratory. All bole sections were kept outside until May 2022, after which they were transferred to the laboratory and kept in an upright position at approximately 22 °C under a 16:8–hour light:dark cycle in individual rearing cages made from fibreboard drums (101 cm high × 57.2 cm diameter) capped with rigid opaque polyethylene lids and steel lever-lock ring closures. A circular hole (9 cm diameter) was cut into the centre of each lid to accommodate an inverted opaque plastic cup (475 mL) with a circular exit hole (2.7 cm diameter) cut into its base. A 375-mL transparent cup was placed on top of the larger cup to collect emerged insects, and a 1.5-m-long string was installed in each rearing cage to provide a way for insects to exit the drum. The ends of all bole sections were sealed with paraffin wax before being placed in the rearing cages to reduce desiccation. Boles and rearing cage interiors were sprayed with water until the surfaces were visibly wet every 15 days. All bole sections were inspected weekly for 20 consecutive weeks, from 13 May to 13 October 2022, and all emerged insects were collected. Insects that had not exited the rearing cages were removed manually. The sawdust that accumulated in the bottom of individual drums was collected monthly and inspected for insects. Insects from each rearing cage were stored in a vial containing 95% ethanol. Vials were capped and stored at approximately 5 °C until inspection. Only adult Monochamus spp. were sorted, sexed, and identified to species, using morphological characters (Bousquet et al. Reference Bousquet, Laplante, Hammond and Langor2017).

In fall 2022, all bole sections were chopped with a hydraulic gas log splitter (Surge Master® 26HVGC-L; Belkin, Playa Vista, California, United States of America), and all larvae were collected. Each larva was placed in a 2-mL micro centrifuge tube (VWR®, VWR International, Radnor, Pennsylvania, United States of America) containing 95% ethanol. Micro centrifuge tubes were capped and stored at approximately 5 °C until inspection. All Monochamus larvae were identified to species level, using morphological characters, per Craighead (Reference Craighead1923), Chu (Reference Chu1949), and Stehr (Reference Stehr1991). Monochamus larvae were also compared to identified specimens preserved in the entomological collection of Natural Resources Canada’s Great Lakes Forestry Centre (Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario; Monochamus scutellatus: reference # S65-1848-01, Vermillion Bay # 18, Red Pine, 23.vi.1965; Monochamus mutator: reference # S64-2207-02, Sarnia L. Erie, Red Pine, 29.iv.1964; Monochamus notatus: reference # 6386, reg # 42-5-F489, Nipissing Dist., White Pine, 8.vii.1942).

Statistical analyses

Six generalised linear models were used to analyse the effect of host volatiles in the attraction of M. maculosus, M. scutellatus, and M. notatus to monochamol and α-pinene (two generalised linear models per species). For each individual Monochamus species, a Poisson and a negative binomial model (hereafter, “NB”) were compared to assess for overdispersion in count data. Model selection was performed following the methodology described by Fávero et al. (Reference Fávero, Souza, Belfiore, Corréa and Haddad2021). Log-likelihood ratio test and the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) for goodness of fit (Burnham and Anderson Reference Burnham and Anderson2004; Zuur et al. Reference Zuur, Ieno, Walker, Saveliev and Smith2009) were used to confirm that the NB regression model presented a better fit to the data in comparison to the Poisson regression model for the three beetle species. Differences in the number of adult M. maculosus, M. scutellatus, and M. notatus collected by traps across different treatments (i.e., host volatiles) were assessed with analyses of deviance with likelihood ratio test (Type II test) based on the NB regression model for each species. Post hoc pairwise comparisons with Tukey-adjusted P-values were conducted to assess differences in the estimated marginal means (emmeans) for each Monochamus species collected between different treatments.

Additionally, eight generalised linear models were used to analyse the effect of trap height (10 m and 1.5 m) on adult captures of M. maculosus and M. scutellatus in field site #1 and field site #2 (i.e., two generalised linear models per species per field site). For each individual Monochamus species from field sites #1 and #2, a Poisson model and a negative binomial regression model were compared to assess for overdispersion in the count data as above. The negative binomial regression model was selected as the most suitable model for the M. maculosus and M. scutellatus data from field sites #1 and #2, following the same methodology as above. All statistical analyses were conducted using a significance level of α = 0.05.

The volume (m3), cubic volume per hectare (m3/ha), density (logs/ha), and percentage of deadwood cover on the ground (i.e., the percentage of ground surface covered by coarse woody debris at the transect level) of individual pieces of down coarse woody debris (“logs”) sampled in the four plots established in field site #1 and the five plots established in field site #2 were calculated following the methodology described in Waddell (Reference Waddell2002). The mean volume per hectare was estimated by first summing the cubic volume per hectare of all individual softwood pieces tallied within plots and dividing that sum by the total number of plots established in field site #1 (n = four plots total) and in field site #2 (n = five plots total). The mean density per hectare and mean percentage of deadwood cover on the ground in field site #1 and in field site #2 (per-unit-area value) were estimated using the same methodology to estimate the mean volume per hectare. Descriptive analysis was used to describe differences observed in the mean volume per hectare, mean density per hectare, and mean percentage of deadwood cover on the ground of down coarse woody debris of softwood species between the two field sites. Individual pieces of down coarse woody debris of hardwood species sampled along transects in field site #1 and in field site #2 were excluded from analyses because they would not be used as resources by Monochamus species.

Descriptive analyses were conducted to describe the number of adult Monochamus spp. that emerged from different bole sections of logs and snags from the two field sites. A generalised linear mixed model with Poisson distribution was performed to analyse the effect of bole section (lower, middle, and upper bole) and tree species (A. balsamea, P. banksiana, and P. glauca) on the number of M. scutellatus larvae collected from logs in field site #1. For field site #2, a generalised linear mixed model with Poisson distribution was performed to analyse the effects of bole section on the number of M. scutellatus larvae collected from logs. Individual logs were included as a random effect in the two models to account for the dependence structure of the data from different bole section heights at the tree level. Model fit was assessed with diagnostic plots of scaled residuals from the DHARMa package (Hartig Reference Hartig2022) in R, version 4.1.2 (R Core Team 2021). Goodness-of-fit test on the scaled residuals was used to confirm that the observed dispersion was not different than expected with simulation under the fitted model. Two reduced Poisson regression models were fitted for field site #1 data, each including only one fixed-effect predictor (either bole section or tree species), and one null Poisson regression model was fitted for field site #2 data with no fixed-effect predictors. Individual logs were included as a random effect in reduced and null models for both field sites. Full models for field site #1 and for field site #2 were compared with corresponding reduced and null models using the likelihood ratio test to assess the contribution of each fixed-effect predictor to model fit. Post hoc pairwise comparisons with Tukey-adjusted P-values were performed to determine differences in the estimated marginal mean (emmeans) numbers of larvae between different bole sections averaged over host-tree species from field site #1. All analyses were performed using the software R, version 4.1.2 (R Core Team 2021), using a significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

Host-mediated reproductive isolation

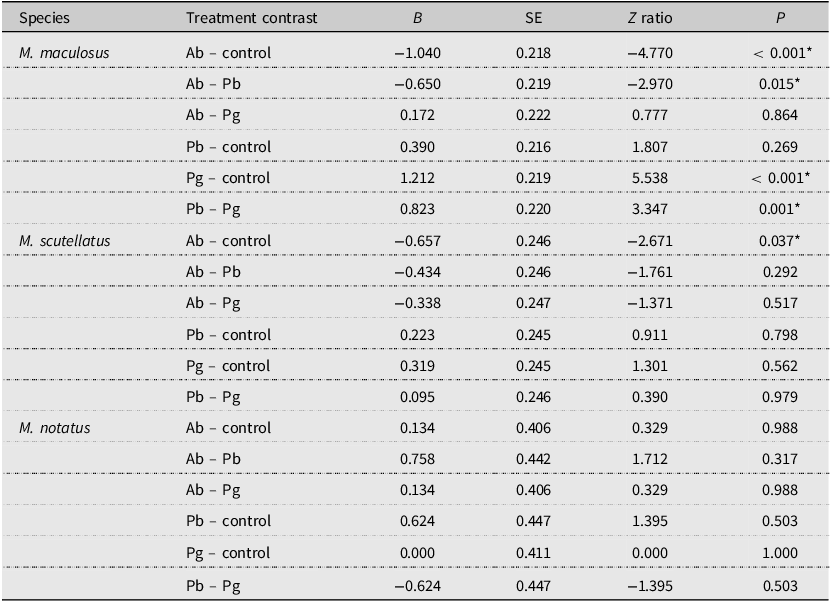

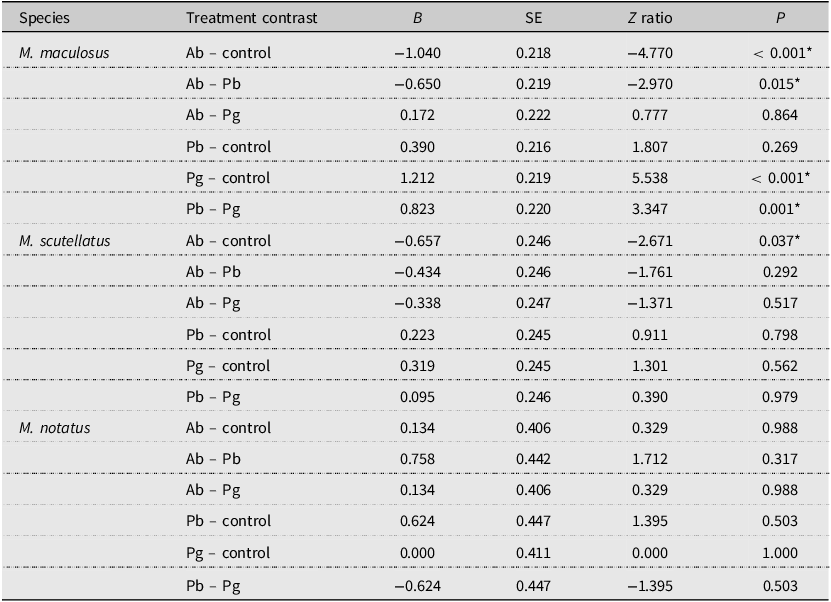

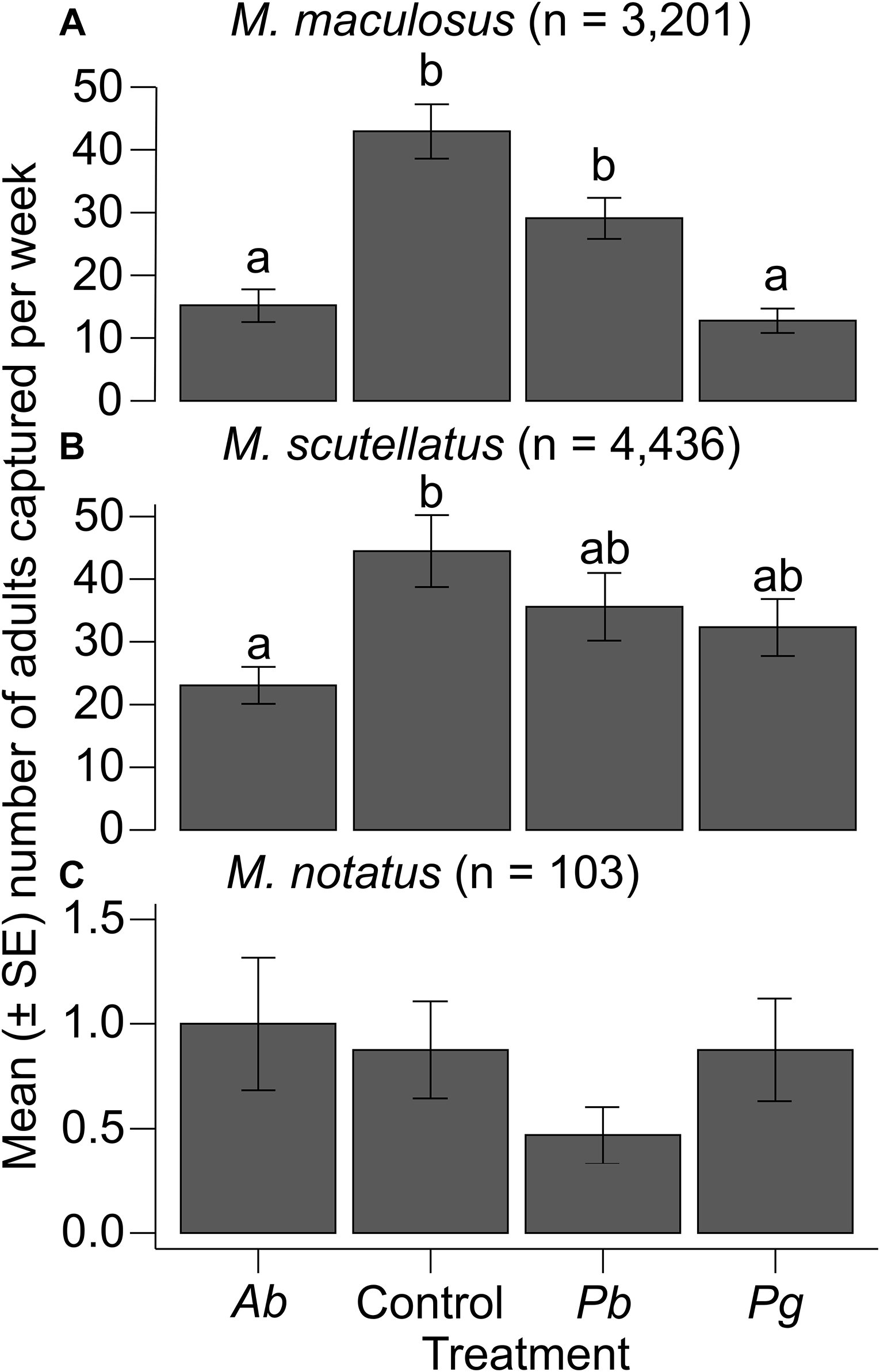

A total of 3201 adult M. maculosus were captured from 32 traps assigned to the four different treatment groups. The means ± standard errors of M. maculosus collected per week from traps baited with monochamol and α-pinene (control) were 43.0 ± 4.3, from traps baited with monochamol and P. banksiana foliage were 29.1 ± 3.3, from traps baited with monochamol and A. balsamea foliage were 15.2 ± 2.6, and from traps baited with monochamol and P. glauca foliage were 12.8 ± 1.9. Analysis of deviance with a likelihood ratio test indicated a significant overall effect of trap treatments on the number of adult M. maculosus captured (likelihood ratio χ 2 = 40.206; df = 3; P < 0.001). Post hoc pairwise comparisons (emmeans) indicated that the control treatment resulted in significantly higher M. maculosus trap captures than the A. balsamea and P. glauca treatments did (all P < 0.001). The P. banksiana treatment resulted in significantly higher M. maculosus trap captures than the A. balsamea and P. glauca treatments did (all P < 0.05). No other significant differences in trap captures of M. maculosus were observed among treatments (all P > 0.05; Table 2; Fig. 2A).

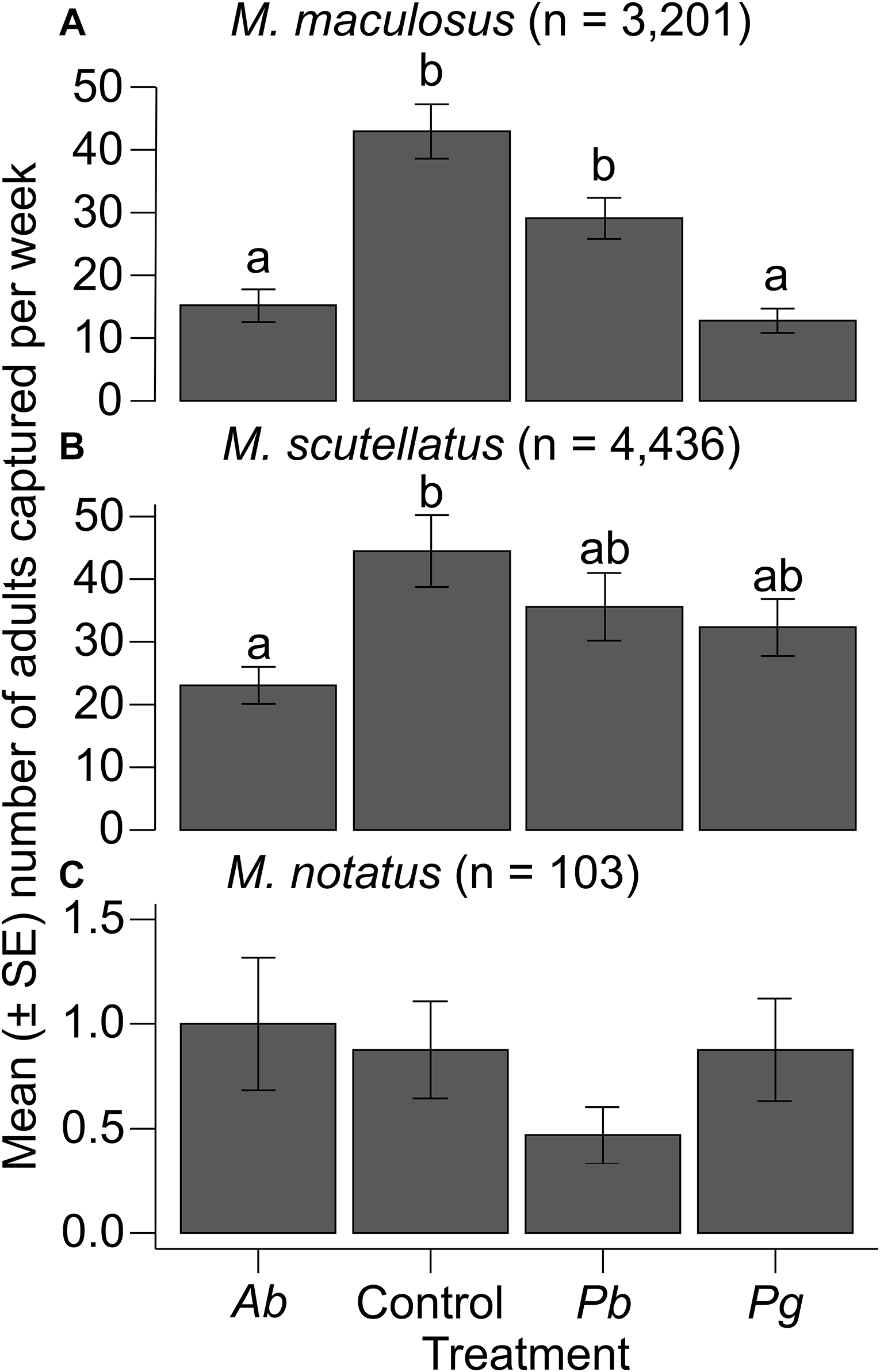

Table 2. Paired contrasts of the total number of adult Monochamus maculosus, M. notatus, and M. scutellatus collected per week from multifunnel traps baited with monochamol and either α-pinene (control) or fresh foliage and branches of Abies balsamea (Ab treatment), of Pinus banksiana (Pb treatment), or of Picea glauca (Pg treatment; n = 4 dates of collection total; 32 traps used total). Results were obtained using post hoc pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means (α = 0.05) from generalised linear models. Clearcut mixed-wood forests in the Algoma Region, Ontario, Canada, were used as collection sites. Results are given on the log (not the response) scale. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) between treatment estimated marginal means (emmeans); SE, standard error

Figure 2. Mean number of adult Monochamus spp. caught per week in multifunnel traps baited with monochamol and α-pinene (control) or monochamol and fresh branches and foliage of four different host species (Ab, Abies balsamea; Pb, Pinus banksiana; Pg, Picea glauca): A, M. maculosus; B, M. scutellatus, and C, M. notatus. Differences among treatments within M. maculosus and M. scutellatus were determined with post hoc pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means (P < 0.05) from generalised linear models. No significant differences among treatments within M. notatus were found with post hoc pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means (P > 0.05) from generalised linear models. SE, standard error.

A total of 4336 adult M. scutellatus were captured from 32 traps assigned to the four different treatment groups. The means ± standard errors of M. scutellatus collected per week from traps baited with monochamol and α-pinene (control) were 44.5 ± 5.7, from traps baited with monochamol and A. balsamea foliage were 23.1 ± 3.0, from traps baited with monochamol and P. banksiana foliage were 35.6 ± 5.4, and from traps baited with monochamol and P. glauca foliage were 32.3 ± 4.6. The overall effect of trap treatments on the number of adult M. scutellatus captured was not significant (likelihood ratio χ 2 = 7.1747; df = 3; P = 0.066). However, post hoc pairwise comparisons (emmeans) indicated that the control treatment resulted in significantly higher M. scutellatus trap captures than the A. balsamea treatment did (P = 0.037). No other significant differences in trap captures of M. scutellatus were observed among treatments (all P > 0.05; Table 2; Fig. 2B).

A total of 103 adult M. notatus were captured from 32 traps assigned to the four different treatment groups. The means ± standard errors of M. notatus collected per week from traps baited with monochamol and α-pinene (control) were 0.9 ± 0.2, from traps baited with monochamol and A. balsamea foliage were 1.0 ± 0.3, from traps baited with monochamol and P. banksiana foliage were 0.5 ± 0.1, and from traps baited with monochamol and P. glauca foliage were 0.9 ± 0.2. The overall effect of trap treatments on the number of adult M. notatus captured was not significant (likelihood ratio χ 2 = 3.3298; df = 3; P = 0.343). Post hoc pairwise comparisons (emmeans) indicated that differences in trap captures of M. notatus among treatments were not significant (all P > 0.05; Table 2; Fig. 2C).

Species abundance across the vertical strata of the forest canopy

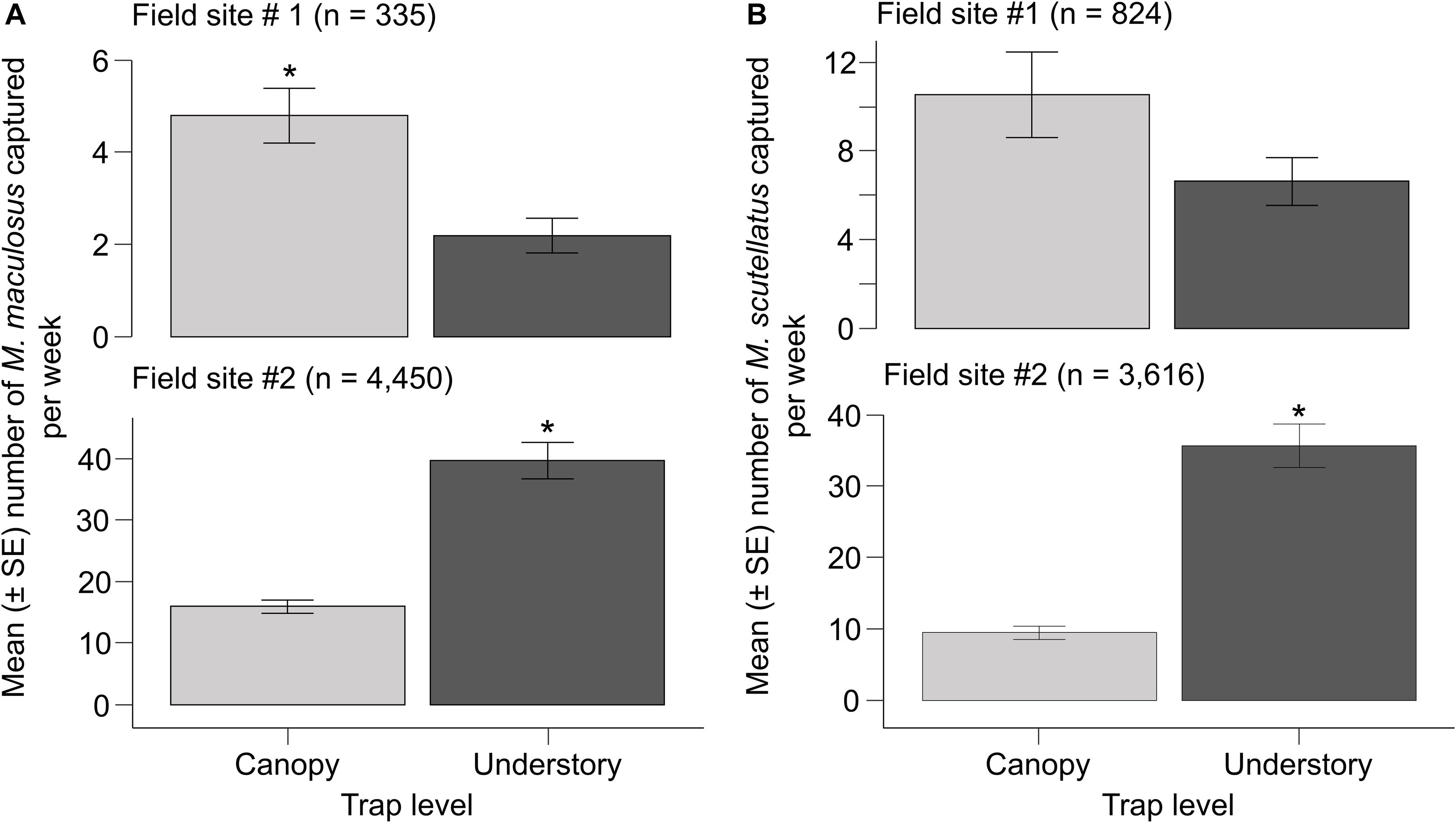

A total of 335 adult M. maculosus were collected from 12 traps at field site #1 and 4450 were collected from 20 traps at field site #2. Adult M. maculosus captures were significantly affected by trap height in the two field sites, but the species’ abundance across the vertical strata of the forest canopy differed between the two sites. At field site #1, the mean ± standard error of adults collected per week from canopy traps (4.8 ± 0.6) was significantly higher than that from understorey traps (2.2 ± 0.4; GLM ß understorey = −0.7841; standard error = 0.1985; Z = −3.95; P < 0.001). At field site #2, the mean ± standard error of adults collected per week from canopy traps (15.9 ± 1.1) was significantly lower than that collected each week from understorey traps (39.7 ± 3.0; GLM ß understorey = 0.9123; standard error = 0.1007; Z = 9.05; P < 0.001; Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Mean number of adult Monochamus spp. captured per week in canopy (hung at ∼10 m height) and understorey multifunnel traps (hung at 1.5 m height) baited with α-pinene and monochamol placed in field sites #1 and #2: A, M. maculosus and B, Monochamus scutellatus. Differences between trap levels within individual species were determined with generalised linear models (P < 0.05). SE, standard error.

A total of 824 adult M. scutellatus were collected from 12 traps at field site #1 and 3616 were collected from 20 traps at field site #2. At field site #1, the mean ± standard error of adults collected per week from canopy and understorey traps was 10.5 ± 1.9 and 6.6 ± 1.1, respectively. Trap height did not have a significant impact on the number of M. scutellatus captured at field site #1 (GLM ß understorey = −0.4645; standard error = 0.2438; Z = −1.90; P = 0.056). However, trap height had a significant impact on the number of M. scutellatus captured at field site #2 with a lower mean ± standard error of adults collected per week from canopy traps (9.5 ± 0.9) than from understorey traps (35.7 ± 3.1; GLM ß understorey = 1.3289; standard error = 0.1410; Z = 9.42; P < 0.001; Fig. 3B).

Nineteen adult M. notatus were collected from 12 traps at field site #1. Of these, a mean ± standard error of 0.2 ± 0.1 individuals were collected per week from canopy traps, and 0.2 ± 0.1 individuals were collected from understorey traps. In addition, one adult M. marmorator was collected from a canopy trap at field site #1. At field site #2, a total of four adult M. notatus were collected from 20 traps. All adult M. notatus at field site #2 were collected from understorey traps, and no adults were collected from canopy traps. Collections of M. notatus at field sites #1 and #2 and of M. marmorator at field site #1 were excluded from analyses due to the low numbers of individuals captured.

Coarse woody debris assessments

A total of eight down coarse woody debris pieces were recorded in the four plots established in field site #1, and a total of 52 down coarse woody debris pieces were recorded in the five plots established in field site #2 (Supplementary material, Table S1). The mean ± standard error length and diameter across the small and large ends of down coarse woody debris pieces were 7.9 ± 1.5 m and 12.5 ± 1.5 cm, respectively, in field site #1 and 6.1 ± 0.5 m and 10.6 ± 0.3 cm, respectively, in field site #2. The mean volume of down coarse woody debris of softwood per hectare was 7.0 m3/ha in field site #1 and 27.2 m3/ha in field site #2. Field site #1 had a mean density of 94 logs/ha (softwood), with a mean percent of deadwood cover on ground of 0.67 %, whereas field site #2 had a mean density of 628 logs/ha (softwood), with a mean percent of deadwood cover on ground of 2.97%. Dead standing trees were observed only in field site #2; all were P. banksiana (n = 6 dead standing trees total). Of these six dead standing trees, three were from decay class 1, two from decay class 2, and one from decay class 4. The mean ± standard error diameter of dead standing trees at 1.4 m height was 4.0 ± 0.5 cm.

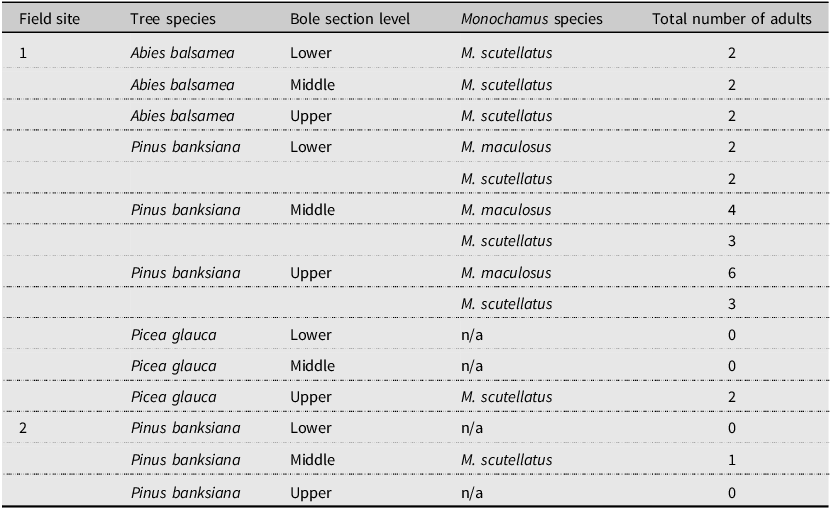

Spatial distribution within and among lying and standing dead trees

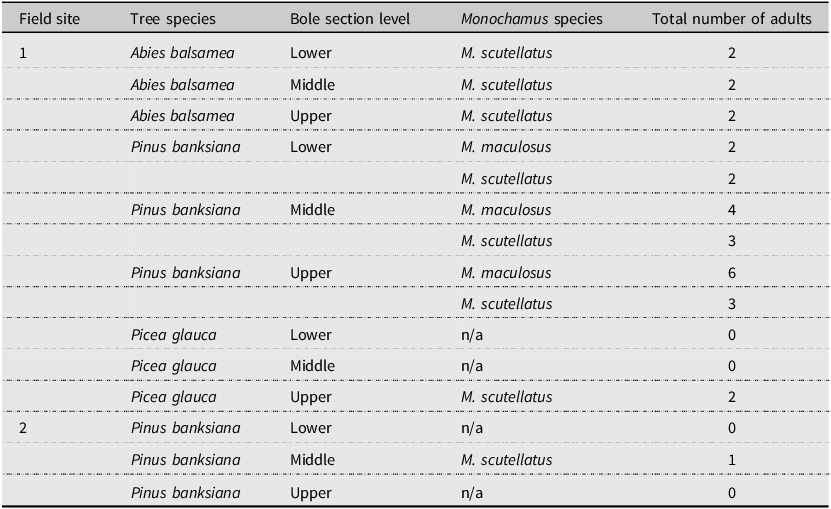

A total of 27 adult Monochamus spp. emerged from 75 bole sections removed from logs at the two field sites (Table 3). No adults emerged from bole sections removed from snags at the two field sites (n = 75 bole sections from snags; 150 bole sections in total). The number of adult Monochamus spp. that emerged from bole sections was too low for statistical analyses.

Table 3. Total number of adult Monochamus spp. that emerged from 45 bole sections removed from lying dead trees from field site #1 (n = 5 bole sections per tree species and bole section level) and from 30 bole sections removed from lying dead trees from field site #2 (n = 10 bole sections per level) and their corresponding origin in terms of tree species and bole section level (60-cm-long sections removed from the 30% – “lower”, 50% – “middle”, and 70% – “upper” levels of each experimental tree height, as measured from the tree base)

A total of 307 larvae were collected from the 150 bole sections from the two field sites: 203 larvae were collected from 90 bole sections from field site #1; 104 larvae were collected from 60 bole sections from field site #2. Of these, 300 larvae were identified (Supplementary material, Table S2). Seven larvae were not identifiable because they had been destroyed during the log splitting process (field site #1: n = 2; field site #2: n = 2; four larvae total) or because morphological identification was not possible (field site #1: n = 2; field site #2: n = 1; three larvae total). Out of the 300 larvae identified, 292 were identified to the genus Monochamus; of the 292, 265 were identified as M. scutellatus. Twenty-seven Monochamus larvae could not be identified to species because they had been damaged during the log splitting process (field site #1: n = 7; field site #2: n = 4; 11 larvae total) or because their morphological identification to species was not possible (field site #1: n = 7; field site #2: n = 9; 16 larvae total). Only M. scutellatus larvae were considered for analyses because approximately 90% of all Monochamus larvae collected from the 150 bole sections were M. scutellatus (field site #1: n = 177 of 191; field site #2: n = 88 of 101, tentatively identified as M. scutellatus). A few M. notatus larvae may have been identified as M. scutellatus. The two species’ morphology is very similar, and the differences are hard to distinguish; that is, compared to matured M. scutellatus larvae, matured M. notatus larvae tend to be more robust, have coarser hair, and present a more continuous band of hair across the anterior area of the pronotum; Craighead Reference Craighead1923). Trapping experiments during the same period show that only 0.3% of all 8948 adult Monochamus individuals collected at the two field sites were M. notatus (see the section, Species abundance across vertical strata of the forest canopy, in Results). Morphological differences between M. scutellatus and M. maculosus larvae are visible under the microscope, making distinguishing the two species possible: that is, the tubercles on the ventral ampullae of matured M. maculosus are glabrous, whereas matured M. scutellatus larvae have the tubercles on the ventral ampullae covered with thin asperites (Craighead Reference Craighead1923; Supplementary material, Fig. S1).

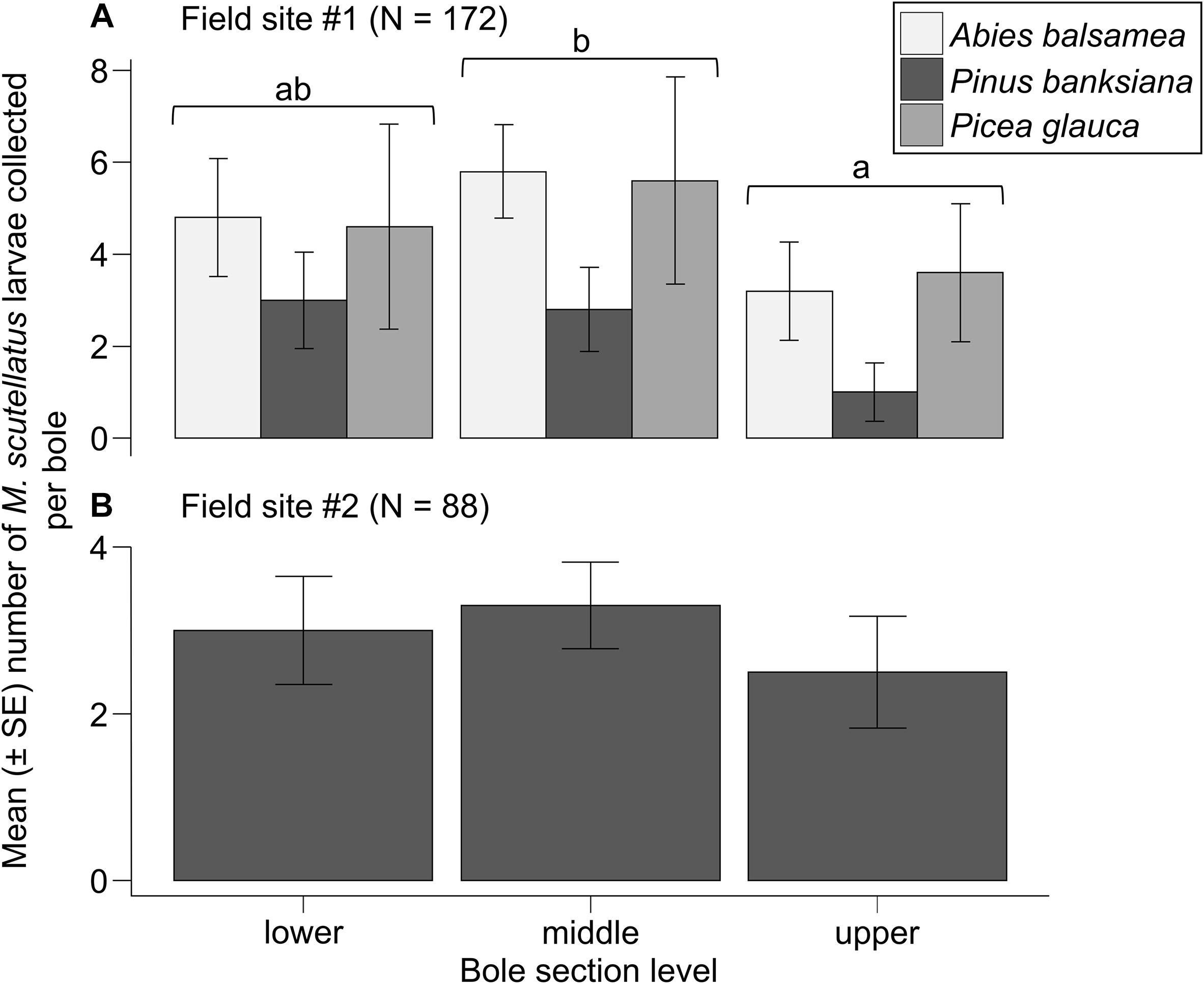

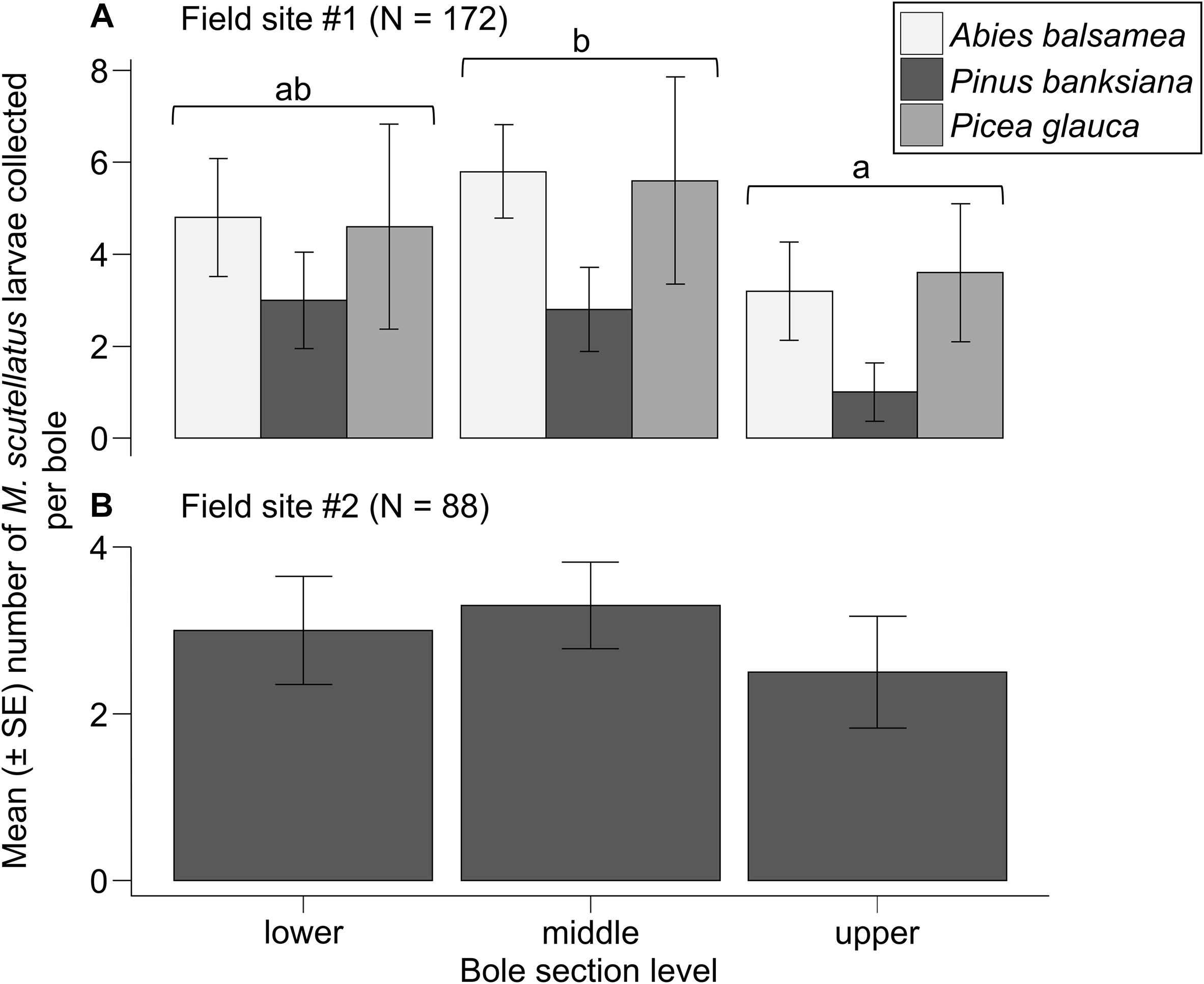

A total of 177 M. scutellatus larvae were collected from 90 bole sections at field site #1. The means ± standard errors of M. scutellatus larvae collected per bole in field site #1 were 3.8 ± 0.5 for sections removed from logs and 0.1 ± 0.1 for sections removed from snags. Collections of M. scutellatus larvae from snag sections in field site #1 were excluded from analyses because few such individuals were collected. Including bole section height significantly improved the model fit for field site #1 compared to a reduced model containing only host tree species as a fixed effect (likelihood ratio χ 2 = 10.008, df = 2, P = 0.006), indicating that bole section height is an important predictor of the number of M. scutellatus larvae collected from logs. The mean number ± standard error of larvae collected per bole from middle sections (4.7 ± 0.9) was significantly higher than that from upper sections (2.6 ± 0.7; emmean B = 0.599, standard error = 0.199, Z ratio = 3.006, P = 0.007). No significant differences were observed in the means ± standard errors of M. scutellatus larvae collected per bole between lower-bole (4.1 ± 0.9) and either middle-bole (emmean B = −0136, standard error = 0.174, Z ratio = −0.780, P = 0.715) or upper-bole sections (emmean B = 0.464, standard error = 0.204, Z ratio = 2.268, P = 0.060). No significant improvement in the model fit for field site #1 was observed when host tree species was added to a model with bole section as a fixed effect (likelihood ratio χ 2 = 2.758, df = 2, P = 0.251), suggesting no significant effect of host tree species in the M. scutellatus larval abundance in logs (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Mean number of Monochamus scutellatus larvae collected per bole from sections removed at 30% (lower), 50% (middle), and 70% (upper) height measured from the base of lying dead trees (logs) of A, Abies balsamea, Pinus banksiana, and Picea glauca in field site #1, and of B, Pinus banksiana in field site #2. Differences among bole section levels averaged over host tree species in field site #1 were determined with post hoc pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means (P < 0.05) from a generalised linear mixed model. SE, standard error.

In field site #2, 88 M. scutellatus larvae were collected from 60 bole sections. All M. scutellatus larvae in field site #2 were collected from bole sections removed from logs (mean ± standard error: 2.9 ± 0.3 larvae collected per bole), and no larvae were collected from bole sections removed from snags. The means ± standard errors of M. scutellatus larvae collected per bole from lower, middle, and upper sections of logs were 3.0 ± 0.6, 3.3 ± 0.5, and 2.5 ± 0.7, respectively. No significant improvement in the model fit for field site #2 was observed when bole section height was included as a fixed effect compared to the null model (likelihood ratio χ 2 = 1.1296, df = 2, P = 0.568), suggesting that bole section height does not significantly explain the variation observed in the number of M. scutellatus larvae collected from logs (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

Pheromones are widely used among insects to mediate mate location and recognition and are often observed to differ qualitatively, quantitatively, or both among species (Symonds and Elgar Reference Symonds and Elgar2008; Wyatt Reference Wyatt and Wyatt2014; Allison and Cardé Reference Allison, Cardé, Allison and Cardé2016). Research on the pheromone biology of the genus Monochamus has revealed a general pattern of pheromone parsimony, with several species using monochamol as their aggregation-sex pheromone or putative pheromone attractant, including the sympatric M. maculosus, M. notatus, and M. scutellatus in eastern Canada (Hanks and Millar Reference Hanks and Millar2016; Millar and Hanks Reference Millar, Hanks and Wang2017; Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, Guignard, Smith and Allison2024). Hybridisation among Monochamus species in the field seems rare despite this pheromone parsimony, suggesting that additional mechanisms facilitate reproductive isolation among the three species, including differences in host and habitat preferences (Dodds Reference Dodds2014; Togashi and Appleby Reference Togashi and Appleby2023). Although the present study found no evidence of specific host and habitat preferences of sympatric M. scutellatus, M. maculosus, and M. notatus that confer reproductive isolation, our results suggest that vertical abundance across the forest canopy in M. maculosus and M. scutellatus could be driven by resource availability, and that M. scutellatus seems to prefer softwood material lying on the forest floor over standing dead trees for oviposition.

Vertical stratification in wood-boring Cerambycid beetles in temperate North American forests is likely driven by resource availability, with species abundance across vertical strata positively correlating with the abundance of larval resources. Cerambycid species captured in higher numbers in traps near the ground than in traps in the canopy have been observed to develop in fallen logs, and species captured in lower numbers in traps near the ground than in traps in the canopy have been observed to develop in twigs and cones located in the canopy (Vance et al. Reference Vance, Kirby, Malcolm and Smith2003; Ulyshen and Hanula Reference Ulyshen and Hanula2007). The vertical abundance of M. maculosus in forests may be driven by the availability of oviposition resources. Traps deployed in a forest stand managed for harvesting that had a high volume and density of coarse woody debris lying on the floor (field site #2) showed greater beetle abundance in the understorey than in the canopy. Conversely, M. maculosus trapping collections conducted in a private, unmanaged forest stand that was observed to have a low volume and density of down, coarse woody softwood debris (field site #1) presented greater beetle abundance in the canopy than in the understorey.

The vertical abundance of M. scutellatus in forests may also be driven by the availability of oviposition resources: as with our M. maculosus data, trapping collections of M. scutellatus in field site #2 during the present study showed greater beetle abundance in the understorey than in the canopy, but we observed no differences in M. scutellatus abundance between understorey and canopy trap collections in field site #1.

Studies have shown that forest canopies usually have a lower amount of deadwood compared to the forest floor (see Nordén et al. Reference Nordén, Götmark, Tönnberg and Ryberg2004), but much of the dead wood in forests begins in the canopy in the form of standing dead trees, dead branches and twigs, and rotting heartwood (Fonte and Schowalter Reference Fonte, Schowalter, Lowman and Rinker2004). Although the present study found no evidence of host or habitat partitioning between M. maculosus, M. notatus, and M. scutellatus that could explain their reproductive isolation, our results suggest that M. scutellatus prefer ovipositing on down coarse conifer logs to ovipositing on standing dead conifers. This oviposition habitat preference in M. scutellatus could be related to differences in the physiological conditions of dead wood position for larval development: suspended and standing dead wood generally is drier and decays more slowly than does dead wood that is in contact with the ground (Hjältén et al. Reference Hjältén, Johansson, Alinvi, Danell, Ball and Pettersson2007; Jomura et al. Reference Jomura, Kominami, Dannoura and Kanazawa2008). Boulanger et al. (Reference Boulanger, Sirois and Hébert2013) observed that higher wood moisture content estimates from wood discs positively affected the larval occurrence of M. scutellatus on fire-killed black spruce, P. mariana, trees. Dyer and Seabrook (Reference Dyer and Seabrook1978) reported that M. notatus and M. scutellatus females lay eggs only on logs with water content ranging between 10% and 60% of total dry weight. Although adult insects should select hosts that will optimise larval survival and development (Jaenike Reference Jaenike1978), oviposition preferences and larval suitability are not necessarily related. Although some species make optimal oviposition choices to assure the highest offspring fitness (Pöykkö Reference Pöykkö2006), others choose to oviposit on plants on which their larvae have poor development or fitness (Courtney Reference Courtney1981; Haavik et al. Reference Haavik, Dodds and Allison2017) to, perhaps, avoid competitors and natural enemies (Price et al. Reference Price, Bouton, Gross, McPheron, Thompson and Weis1980; Thompson Reference Thompson1988). Larval cannibalism is common in the genus Monochamus (Victorsson and Wikars Reference Victorsson and Wikars1996; Anbutsu and Togashi Reference Anbutsu and Togashi1997a; Dodds et al. Reference Dodds, Graber and Stephen2001), and females seem to avoid ovipositing on host material already occupied by conspecific eggs or larvae (Anbutsu and Togashi Reference Anbutsu and Togashi1997b, Reference Anbutsu and Togashi2000; Peddle et al. Reference Peddle, De Groot and Smith2002).

Markovic et al. (Reference Markovic, Glinwood, Olsson and Ninkovic2014), Kopaczyk et al. (Reference Kopaczyk, Warguła and Jelonek2020), and Pinto-Zevallos et al. (Reference Pinto-Zevallos, Martins, Andrade, Zawadneak and Zarbin2020) showed that insect behavioural responses can be affected by variation in plant secondary metabolites induced by a variety of biotic and abiotic stresses. In the present study, chopping host plant material into small pieces to bait traps in the field may have altered the chemical composition of the wood’s volatiles or the dynamics of host volatile release, affecting Monochamus spp. responses in different ways than natural host material does. The differences we observed in the numbers of adult M. scutellatus and M. maculosus captured in canopy and understorey traps between the two field site locations in the present study indicate that oviposition resource availability may be an important factor driving the vertical distribution of these species across the forest canopy; however, additional spatial and temporal replications (i.e., field collections using understorey and canopy traps in sites presenting different resource availability scenarios during multiple years) are needed to confirm or refute this hypothesis. Monochamus adults are known to require maturation feeding on twig bark and needles of healthy host trees for a period of 7–12 days (Akbulut and Stamps Reference Akbulut and Stamps2011), and adult Monochamus continue to feed while being reproductively active (Akbulut et al. Reference Akbulut, Togashi, Linit and Wang2017). Maturation feeding and oviposition may occur at different vertical strata of the forest (e.g., feeding or maturation may occur in the canopy of healthy trees, and oviposition may occur in freshly dead host material on the forest floor). Canopy structure and tree density can influence the dispersion and structure of pheromone plumes (Murlis et al. Reference Murlis, Willis and Cardé2000; Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, Thistle, Lamb, Allwine, Edburg and Strom2010; Cardé Reference Cardé2021). The differences we observed in the vertical distribution of M. maculosus and M. scutellatus between an unmanaged, mixed-wood forest stand (field site #1) and a managed, pine-dominated stand (field site #2) may be related to how differences in the structure and species composition between the two sites affected the dispersion and structure of pheromone plumes. These differences in tree species composition, management practices, and forest structure may also contribute to microclimatic variation, potentially influencing physical aspects of trees, such as bark thickness, that are relevant to Monochamus colonisation (Naves et al. Reference Naves, De Sousa and Quartau2006a; Han et al. Reference Han, Kim, Kang and Kim2016).

Although the present study found no evidence of specific host and habitat preferences that could prevent cross-attraction between M. maculosus, M. notatus, and M. scutellatus, other factors may account for their reproductive isolation. Differences in phenological and diel patterns of flight behaviour between M. scutellatus and M. maculosus or M. notatus may contribute to their reproductive isolation (Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, McTavish, Smith and Allison2025). However, the broad overlap in phenological and diel flight activity patterns of M. maculosus and M. notatus (Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, McTavish, Smith and Allison2025) suggests the existence of other isolating mechanisms. Evidence shows that close range or contact pheromones play an important role in the mate-recognition systems of male Cerambycidae (Ginzel Reference Ginzel, Blomquist and Bagnères2010; Millar and Hanks Reference Millar, Hanks and Wang2017), and differences in cuticular hydrocarbons of females may contribute to the reproductive isolation of closely related species (Ginzel et al. Reference Ginzel, Millar and Hanks2003, Reference Ginzel, Moreira, Ray, Millar and Hanks2006; Silk et al. Reference Silk, Sweeney, Wu, Sopow, Mayo and Magee2011). Differences in the relative proportions of cuticular hydrocarbons related to sex have been observed in M. scutellatus (Brodie et al. Reference Brodie, Wickham and Teale2012) and M. galloprovincialis (Ibeas et al. Reference Ibeas, Gemeno, Díez and Pajares2009), but contact pheromone compounds have not yet been identified in the genus. Future investigations into whether differences in cuticular compounds prevent interspecific mating between Monochamus species are needed. In addition, Pershing and Linit (Reference Pershing and Linit1986) and Wallin et al. (Reference Wallin, Schroeder and Kvamme2013) have noted morphological differences in male genitalia among Monochamus species: whether these differences contribute to reproductive isolation requires study. The present study’s results suggest that resource availability and suitability may drive the vertical abundance of M. scutellatus and M. maculosus across the forest canopy. These findings suggest that the chances of finding a mate in Monochamus may be improved if, in addition to using an aggregation-sex pheromone, males and females aggregate on larval host plants that are in a particular physiological condition (freshly cut logs of conifers lying on the forest floor).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.4039/tce.2025.10042.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. Andrade and S. Thomas for their feedback; D. Peerla and W. Byman for facilitating access to field sites; N. Boyonoski, I. Ochoa, J. Goodwin, M. Swinn, A. Carlson, and H. Dunlop for field assistance; J. Goodwin, A. Carlson, and H. Dunlop for collecting insects that emerged from bole sections; C. Rowswell, G. Whalen, and G. Hill for storage space for bole sections; C. MacQuarrie for log splitting and rearing material; and G. Brand for log splitting and larvae collection. The authors acknowledge Natural Resources Canada and the Institute of Forestry & Conservation, University of Toronto for their financial support.

Funding statement

This project was supported by funds from Natural Resources Canada and the Institute of Forestry & Conservation, University of Toronto (Charles Percival Howard Scholarship Fund, Class of 5t2 Prize, Doctoral Completion Award: Forestry, Forestry COVID-19 Research Pivot Fund, School of Graduate Studies Conference Grant, and University of Toronto Fellowship/graduate Student Aid – Forestry).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.