Introduction

Hot tap water is the most common source of scald burns, representing a quarter of all scald injuries requiring hospitalization in the United States (US).Reference Peck 1 A recent study determined that between 2016 and 2018, there were 52,088 emergency department (ED) visits, 7,270 hospitalizations, and 110 hospital-based deaths attributable to tap water burns in the US.Reference Shields 2 The severity of a hot water scald depends on the temperature of the water and the duration of the exposure. Exposure to water at 120°F will result in a serious burn in 10 minutes, whereas exposure to water at 140°F can result in a serious burn in as little as 3 seconds. A third factor, age of the person exposed, also determines scald severity. Because young children and older adults have thinner skin, they sustain severe burns at lower temperatures and shorter exposure times. 3

Young children are uniquely vulnerable to tap water burns due to their developing motor skills and dependence on adult supervision.Reference Shields 4 Between 2009 and 2012, over 2,000 children under 3 years were treated for scald burns in EDs annually.Reference Shields 5 Evidence suggests that poor knowledge of burn risks and treatment among parents and the public may contribute to the burden of scald injuries in young children. Studies have shown that only up to 10% of parentsReference Burgess 6 and the publicReference Lagziel 7 can identify the leading household risks for childhood burns, including hot tap water. Most people also lack adequate knowledge of burn first aid, a characteristic that has been shown to vary with income in parents. 8 In a large survey of the public, 77% of respondents incorrectly identified a superficial burn as a more severe partial thickness burn but indicated they would not seek a healthcare provider for it. 9

Medical and injury surveillance categorizes most scald burns as unintentional injuries. However, scald burns can also lead to investigation by the justice system if the injury is suspected to result from abuse or neglect. The reported incidence of intentional burns, including non-scald burns, in health care centers globally varies from between 0.5 and 25% of all burns, with the highest incidence sizes reported in the US.Reference Loos 10 The Department of Justice recommends assessing criminal intent in childhood scald burns based on traditional indicators derived from medical research: burn uniformity, areas of sparing, burn locations on the body, family history, and speed of seeking medical care. 11 When scald injuries occur during bathing, law enforcement may also investigate environmental factors that contributed to the injury, including the depth of the bathtub or sink, temperature setting of the water heater, and temperature of the water at time intervals; however, this information is time-sensitive and requires immediate investigation. 12 In the absence of investigations to capture this information in a timely manner, medical records are commonly used to determine intent.

The methods of investigation used in criminal cases may strongly impact the determination of intent. Two approaches have been offered to explain scald burns suspected to result from child abuse or neglect. In the first approach, the child presents with traditional indicators of intentional burns (i.e. specific patterns, with delay in seeking care), so the child must have been intentionally burned.Reference Hobbs 13 In the second approach, the child presents with traditional indicators of intentional burns, but the injury occurred or was delayed from treatment unintentionally due to the age or temperature setting of the home water heater, absence of scald protection via a temperature limiting device, or ignorance of how to treat scald burns.Reference Dressler and Hozid 14 Given the high percentage of intentional burns reported in the US relative to the global community, greater attention to the interaction between the medical and criminal justice fields’ response to reports of suspected intentional scald injuries, including the suitability of medical records for determining scald intent, is needed.

Background

To understand the task of discerning intentionality, it is important to recognize the role of water heaters in tap water scalds. Because water heaters can deliver scalding water at a rate that puts a large amount of body surface at risk, water heaters are associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates than other home appliances. As of 2024, the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) recommends that manufacturers preset the temperature of water heaters to 120°F. In 1980, Florida became the first state to pass legislation limiting the temperature setting of new water heaters sold, requiring that manufacturers set water heaters to no more than 125°F.Reference Erdmann 15 As more states passed similar requirements, manufacturers voluntarily adopted the CPSC-recommended 120°F standard in 1988. 16 However, evaluations of these policies have produced mixed results. Prior to the industry’s voluntary agreement, a study in a Washington State found that the state’s 120°F temperature law passed in 1983 reduced tap water scalds. 17 Meanwhile, a study in New York City found that tap water burn incidence remained high following the passage of a similar law in 1996, even with the manufacturers’ voluntary agreement in place.Reference Leahy 18 Further complicating these findings is evidence suggesting that despite the industry standard and regulatory efforts, hot water heaters continue to dispense water at temperatures in excess of the CPSC-recommended limit. A direct observation study in Baltimore City found that hot tap water temperatures exceeded 120°F in 41% of homes, with 27% of homes reaching or exceeding 130°F. 19

Dangerously high tap water temperature is a risk that disproportionately affects certain households such as rental properties. 20 To eliminate the risk of tap water scalds, the American Society of Sanitary Engineering (ASSE) recommends installing temperature-limiting devices, such as mixing valves, which control water temperatures at the point of use (i.e., sinks and bathtubs). 21 However, individuals living in homes built prior to 1986 are less likely to have these devices. While new homes are subject to housing codes that require mixing valves or temperature-limiting devices to ensure water temperatures at the point of use do not exceed 120°F, homes built prior to 1986 are grandfathered out of this safety requirement unless the plumbing system has been upgraded. New water heaters are also sold with an owner’s manual and installation instructions. Though not required by building codes, these manufacturer instructions typically recommend both that water heaters be set to 120°F and that temperature-limiting devices be used to prevent scald burns.

As mandated reporters, clinicians in the US need to know how to distinguish between intentional and unintentional scalds 22 but may not understand how time and temperature impact the clinical presentation of pediatric burns. 23 Case reports of false child abuse diagnoses in scalded children also suggest that the assessment process is complicated by unknown or underestimated hot tap water temperatures in children’s homes. 24 Systematic reviews 25 and a novel clinical prediction tool from the United KingdomReference Kemp 26 have characterized indicators of intentional burns, but no review to our knowledge has yet investigated scald burns in the US specifically. Tracing the evidence to understand the evolution of our current approach to determining intentionality with regard to scald burns may inform opportunities for a more holistic and informed approach that includes structural factors that put some children at greater risk. Additionally, as clinicians in the US adopt new clinical tools to identify intentional scalds, they can benefit from a summary of the most nationally relevant indicators and an appreciation for the structural factorsReference Kendi and Macy 27 at play.

In this study, we present an overview of the existing literature on intentional scald burns in children caused by hot tap water in order to improve their identification and prevention. This systematic review aims to answer two questions: (1) What are the indicators of intentional scald burns in children according to the literature; and (2) is the body of evidence for common indicators of intentional scald burns subject to bias?

Methods

Study Selection

This systematic review considered full-text primary studies of scald burns among children younger than 18 years of age. Additional inclusion criteria were studies that examined the intent of scalding (intentional, neglectful, or unintentional) and injury patterns (e.g., burn depth, burn distribution, and total body surface area) as exposures, outcomes, data, or recommended diagnostic criteria. Primary studies must have reported information on child participants and scald burns separate from data on adult participants and other types of injuries or burns. No requirements were specified on the certainty of abuse or participants’ death status at presentation. Studies without data collected in the US were excluded, given the aim to summarize the literature with implications for mandatory reporters in the US. Studies that exclusively addressed unintentional scalds, burn care management, or non-thermal burns (e.g., chemical) were excluded. Letters and commentaries were excluded, as well as studies using animal models or non-English language. No date limits were set.

Search Strategy

The search was conducted in six databases: PubMed, PsychInfo, Cochrane, Embase, Scopus, and Academic Search Ultimate. The initial search was conducted in November 2021. A weekly email alert was created to notify the research team if any newly published articles matched the search query through February 2024. Literature review articles and reference lists of identified articles were examined for further inclusion.

The following search terms and equivalents were used: (1) scald (or synonyms such as “scald injury,” “immersion burn,” “water burn,” etc.), (2) intentional, neglectful, or unintentional (or synonyms such as “inflicted,” “negligent,” “accidental,” etc.), and (3) children (or synonyms such as “infant,” “pediatric,” “babies,” etc.).

One investigator conducted an initial title screening of all articles generated by the search strategy, followed by an abstract screening of all articles included in the title screen. Another investigator reviewed ten percent of the sample at each round of screening (500 titles and 40 abstracts) to verify the quality of the original review. Once title and abstract screening were completed, two investigators independently reviewed full-text manuscripts of all articles retained to determine whether inclusion and exclusion criteria were met. The investigators discussed any disagreements about eligibility, and a third author was consulted until consensus was reached.

Data Abstraction and Analysis

A data abstraction form was used to aid in the analysis of studies that passed full-text review. Outcomes were collected on indicators of intentional, neglectful, and/or unintentional scalds, such as specific burn patterns, delay in seeking care, and housing risks. Other information collected included article type, study design, sample size, target population, method of determining scald intent, references cited in the text, main results, author takeaways, and strengths and limitations of the study. Two investigators divided the data abstraction of all included articles and confirmed the accuracy of the information obtained by the other investigator.

Results were synthesized and presented by reported indicators of scalding intent. Due to high heterogeneity across studies, the effect sizes could not be pooled. To understand how diagnostic criteria have been informed by evidence over time, articles were analyzed for references to prior studies also included in this review and tabulated by date of publication.

Assessment of Quality and Risk of Bias

To assess risk of bias for each study, we selected critical appraisal tools from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) to account for the multiple study design types included in our review. 28 Three tools were employed corresponding to study design: cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort. Each tool included 8 to 11 items: quality of reporting (1–3 items), confounding (1–3 items), and bias (4–7 items). Possible item ratings were yes, no, or unclear. Two investigators independently assessed each article, and disagreements were resolved with a third investigator.

Results

Search Results and Study Characteristics

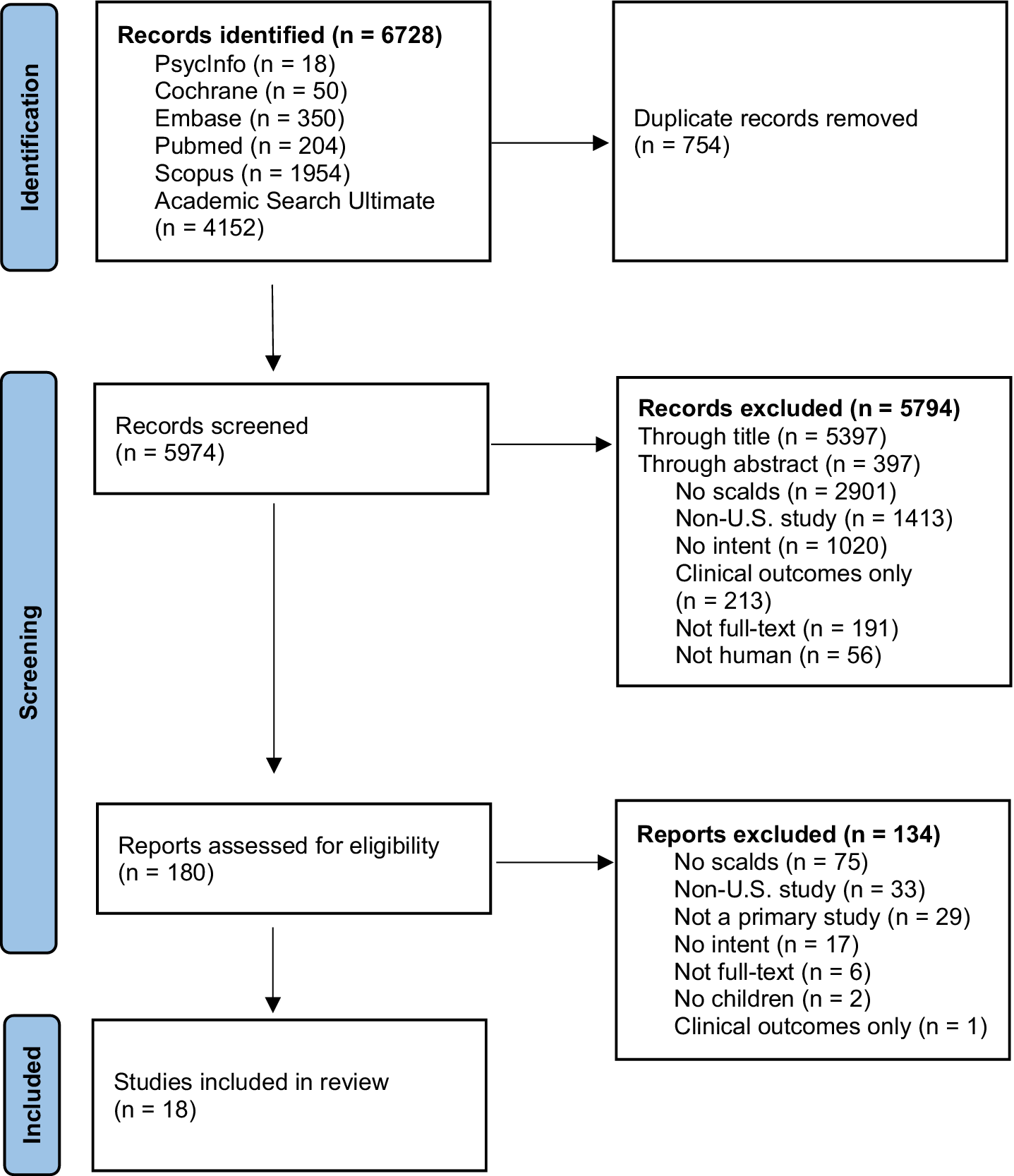

Using our search strategy, we identified 5,974 unique records for screening through titles, and 577 abstracts were reviewed. Of these, 180 full-text manuscripts were downloaded for review, and 18 studies were determined to meet inclusion criteria (Figure 1). All eligible studies were published between 1970 and 2024. Most were cross-sectional in design, with 2 case-control and 2 cohort study designs. Sample size ranged from 26 to 5,553 children, representing a total of 4,391 children with scald burns and 711 children suspected of sustaining intentional scald burns.

Figure 1. Flowchart of study selection.

Only 2 studies (Feldman et al.Reference Feldman 29 and Daria et al.Reference Daria 30) exclusively recruited participants with scald burns. In 3 studies (Ayoub et al.,Reference Ayoub and Pfeifer 31 Angel et al.,Reference Angel 32 and Zaloga et al.Reference Zaloga and Collins 33), participants were not restricted to scalded children during recruitment, but all intentionally burned children had scalds. Among the remaining 13 studies, burning agent and specific burn patterns were the only data that could be extracted on scalds specifically. The data collected from all 18 studies are presented below and in Table 1.

Table 1. Reviewed studies organized by year published

1 N.H. Stone, L. Rinaldo, C.R. Humphrey, and R.H. Brown, “Child Abuse by Burning,” The Surgical Clinics of North America 50, no. 6 (1970): 1419–1424, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-6109(16)39298-2.

2 E. Lenoski and K. Hunter, “Specific Patterns of Inflicted Burn Injuries,” The Journal of Trauma 17, no. 11 (1977): 842–846, https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-197711000-00004.

3 K.W. Feldman et al., “Tap Water Scald Burns in Children,” Pediatrics 62, no. 1 (1978): 1–7.

4 C. Ayoub and D. Pfeifer, “Burns as a Manifestation of Child Abuse and Neglect,” American Journal of Diseases of Children 133, no. 9 (1979): 910–914, https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1979.02130090038006.

5 J.S. Montrey and P. J. Barcia, “Nonaccidental Burns in Child Abuse,” Southern Medical Journal 78, no. 11 (1985): 1324–1326, https://doi.org/10.1097/00007611-198511000-00013.

6 G.F. Purdue, J.L. Hunt, and P.R. Prescott, “Child Abuse by Burning — An Index of Suspicion,” The Journal of Trauma 28, no. 2 (1988): 221–224.

7 J. Showers and K. M. Garrison, “Burn Abuse: A Four-Year Study.” Journal of Trauma 28, no. 11 (1988): 1581–1583, https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-198811000-00011

8 C. Angel et al., “Genital and Perineal Burns in Children: 10 Years of Experience at a Major Burn Center,” Journal of Pediatric Surgery 37, no. 1 (2002): 99–103, https://doi.org/s002234680211654x.

9 S. Daria et al., “Into Hot Water Head First: Distribution of Intentional and Unintentional Immersion Burns,” Pediatric Emergency Care 20, no. 5 (2004): 302–310. https://doi.org/00006565-200405000-00005.

10 W.F. Zaloga and K.A. Collins, “Pediatric Homicides Related to Burn Injury: A Retrospective Review at the Medical University of South Carolina,” Journal Forensic Science 51, no. 2 (2006): 396–399, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00066.x.

11 P. Ojo et al., “Pattern of Burns in Child Abuse,” American Surgeon 73, no. 3 (2007): 253–255, https://doi.org/10.1177/000313480707300311.

12 S. Hayek et al., “The Efficacy of Hair and Urine Toxicology Screening on the Detection of Child Abuse by Burning,” Journal of Burn Care and Research 30, no. 4 (2009): 587–592, https://doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181abfd30.

13 S. Dissanaike et al., “Burns as Child Abuse: Risk Factors and Legal Issues in West Texas and Eastern New Mexico,” Journal of Burn Care and Research 31, no. 1 (2010): 176–183, https://doi.org/10.1097/bcr.0b013e3181c89d72.

14 L. Wibbenmeyer et al., “Factors Related to Child Maltreatment in Children Presenting with Burn Injuries,” Journal of Burn Care and Research 35, no. 5 (2014): 374–381, https://doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0000000000000005.

15 E.I. Hodgman et al., “The Parkland Burn Center Experience with 297 Cases of Child Abuse from 1974 to 2010,” Burns 42, no. 5 (2016): 1121–1127, https://doi.org/s0305-4179(16)00071-1.

16 M.C. Pawlik et al., “Children With Burns Referred for Child Abuse Evaluation: Burn Characteristics and Co-existent Injuries,” Child Abuse and Neglect 55 (2016): 52–61, https://doi.org/S0145-2134(16)30037-0.

17 Z.J. Collier et al., “A 6-Year Case-Control Study of the Presentation and Clinical Sequelae for Noninflicted, Negligent, and Inflicted Pediatric Burns,” Journal of Burn Care & Research 38, no. 1 (2017): E101-E124, https://doi.org/10.1097/bcr.0000000000000408.

18 S. Vazquez et al., “Patterns for Child Protective Service Referrals in a Pediatric Burn Cohort,” Curēus 16, no. 1 (2024): e51525, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.51525.

Characteristics of Intentional Scalds

Burning Agent

All but one study reported on causal agents of burns, though evidence is mixed on whether certain types of thermal burning (e.g., scalds, contact burns, flame) are more indicative of intentional injury than others. Of the 16 studies that did not restrict study participants to scalded children, only 6 suggested that scalds distinguish intentional burning. However, within scald injuries specifically, certain causal agents appear linked to intentional burns. All 10 studies that examined causal agents of scalds suggested that those caused by tap water are more indicative of intentional burning than other liquids.

Specific Burn Patterns

Twelve studies reported on specific burn patterns potentially indicative of intentional scalding. First introduced by Stone et al.Reference Stone, Rinaldo, Humphrey and Brown 34 and Lenoski et al.,Reference Lenoski and Hunter 35 these burn patterns are generally categorized as immersion, bilateral, and splash burns. Immersion burns are uniform with circumferential lines of demarcation; bilateral burns are symmetric on the body; and splash burns are non-uniform as liquid cools on the body. Only one small-sample (n=26) study reported not observing any of these burn patterns. 36 Lenoski et al. also described flexion burns as a category of burns with sparing at the body’s creases where exposure to hot liquid is avoided, reporting an incidence of 11.6% in abused patients. Subsequent studies did not report data on this pattern. 37

Immersion burns were measured in 10 of the 12 studies and occurred significantly more often in intentionally than unintentionally scalded children. Of the studies that measured immersion burns in treatment centers, the pattern had a reported incidence between 37.5–68% among patients involving suspicion of abuse. Two of the studies (Montrey et al.Reference Montrey and Barcia 38 and Purdue et al.Reference Purdue, Hunt and Prescott 39) further measured and identified within their samples “forced” immersion burns, a subcategory of immersion burns with central sparing where the body is pressed against a cool container. In a study of burn homicides, immersion burns were observed in all 3 deaths caused by scalding in the sample. 40 Bilateral burns were measured in 7 studies and similarly occurred significantly more often in children where abuse was suspected than unintentionally scalded children, with a reported incidence between 32–68.8%.

Splash burn intentionality was mixed across the 4 studies that measured the pattern. Although Lenoski et al. reported an incidence of 16.3% among abused patients and first introduced the pattern as indicative of intentional scalding, 41 subsequent studies (Ayoub et al. 42 and Purdue et al. 43) reported not observing the pattern among abused patients, and a recent study even reported splash burns to occur significantly more often in unintentionally than intentionally scalded patients, with an incidence of 80%.Reference Pawlik 44 “Flowing” burns, which are also non-uniform but caused by contact with running tap water rather than a single splash, have been proposed as a more appropriate pattern indicator of intentional scalding than splash burns, with one study reporting 15.5% of such scalds in abused patients. 45

Distribution, Depth, Size, and Additional Injuries of Burns

Three studies (Angel et al., 46 Daria et al., 47 and Zaloga et al. 48) measured burn distribution of scalds, but all reported body locations potentially indicative of intentional burning. The buttocks/perineum were identified in all three studies, followed by the feet in two studies, and the hands/lower forearm, feet, and back in one study. Only one small-sample study (n=20) measured burn depth of scalds and reported all intentional burns to be either partial or full thickness. 49

Two small-sample studies (n=26 and 20) reported on burn size and the presence of additional injuries. One study set in a burn center found that intentional scalds had an average total body surface area (TBSA) of 13.8%, ranging from 5–33%. 50 This study also reported previous injuries present in all patients with intentional scalds. 51 The other study examined burn homicides and naturally reported larger burn sizes in intentional scalds, ranging from 30-45%. 52 This study found no additional injuries present with homicidal scalds. 53

Social Risk Factors

Of the five studies that reported the sex of scalded children, three described a higher rate of males in the intentionally scalded group (Feldman et al., 54 Ayoub et al. 55 and Angel et al. 56). A fourth described a higher rate among females, 57 and another described no difference between sexes. 58 Evidence suggests that scalds in younger children warrant attention to possible intentional burning. In the four studies that reported the age of scalded children, all children with intentional scalds were two years old or younger. Only two small-sample studies (n=26 59 and 20 60) collected data on the race of scalded children; both reported that children with intentional scalds were mostly Black.

The household characteristics suggested to indicate intentionally scalded children mainly reflect low-income status. In Ayoub et al.’s study, perpetrators of intentional scalds were more likely to be unemployed, highly mobile, single/separated, and previously subject to domestic violence. 61 Feldman et al.’s analysis grouped these factors in a “stress” category and found that it applied more often to children with intentional scalds. 62

Housing Risks, Delay in Seeking Care, and Historical Details

None of the studies examined the association between intentional scalds and housing risks, including hot tap water temperatures. In Feldman et al.’s article, however, the authors complemented their analysis of patients admitted to a hospital for tap water burns, which measured suspected child abuse, with a survey of home water temperatures conducted in a local sample. 63 This separate analysis of 57 households found water temperatures in most homes to exceed 130°F. 64 Although the authors did not collect data to conclude whether water temperatures were high in the homes of the children suspected of being abused, they suggested that decreased temperatures would effectively reduce the risk of scalding for any child exposed to hot tap water, whether unintentionally or intentionally. 65

In one study, delays in seeking treatment of >2 hours were identified significantly more often in children with intentional scalds. 66 Other historical details related to intentional scalds were documented in two studies and involved characteristics of the people present with the child during the medical care and injury event. Feldman et al. reported that tap water scalds were more likely to be intentional when children were brought in for medical care by someone other than the adult present during the injury event and when an adult drew the water compared to when another child drew the water. 67 Zaloga et al. reported that tap water scalds resulting in homicide were more likely to involve perpetrators who were adult females, such as mothers and older sisters. 68

Evolution of the Evidence

In 14 of the 18 reviewed articles, authors cited and supported the findings of previous studies included in this review (Table 2). As some of the earliest reports published, Stone et al., 69 Lenoski et al., 70 and Purdue et al.’s 71 articles were cited and supported most often. With no conflicting evidence, articles cited previous studies to support the following characteristics as indicators of intentional burns: scalds caused by tap water and historical inconsistencies in 5 studies, poverty-related factors in 3 studies, and additional injuries in 1 study. Additionally, previous findings were cited to support delay in seeking care as an indicator of intentional burns in 3 studies, though one of these studies did not measure delay in seeking care in its own sample.

Table 2. Quality assessment, method of classifying intent, and cited studies

1 N.H. Stone, L. Rinaldo, C.R. Humphrey, and R.H. Brown, “Child Abuse by Burning,” The Surgical Clinics of North America 50, no. 6 (1970): 1419–1424, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-6109(16)39298-2.

2 E. Lenoski and K. Hunter, “Specific Patterns of Inflicted Burn Injuries,” The Journal of Trauma 17, no. 11 (1977): 842–846, https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-197711000-00004.

3 K.W. Feldman et al., “Tap Water Scald Burns in Children,” Pediatrics 62, no. 1 (1978): 1–7.

4 C. Ayoub and D. Pfeifer, “Burns as a Manifestation of Child Abuse and Neglect,” American Journal of Diseases of Children 133, no. 9 (1979): 910–914, https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1979.02130090038006.

5 J.S. Montrey and P. J. Barcia, “Nonaccidental Burns in Child Abuse,” Southern Medical Journal 78, no. 11 (1985): 1324–1326, https://doi.org/10.1097/00007611-198511000-00013.

6 G.F. Purdue, J.L. Hunt, and P.R. Prescott, “Child Abuse by Burning — An Index of Suspicion,” The Journal of Trauma 28, no. 2 (1988): 221–224.

7 J. Showers and K. M. Garrison, “Burn Abuse: A Four-Year Study.” Journal of Trauma 28, no. 11 (1988): 1581–1583, https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-198811000-00011

8 C. Angel et al., “Genital and Perineal Burns in Children: 10 Years of Experience at a Major Burn Center,” Journal of Pediatric Surgery 37, no. 1 (2002): 99–103, https://doi.org/s002234680211654x.

9 S. Daria et al., “Into Hot Water Head First: Distribution of Intentional and Unintentional Immersion Burns,” Pediatric Emergency Care 20, no. 5 (2004): 302–310. https://doi.org/00006565-200405000-00005.

10 W.F. Zaloga and K.A. Collins, “Pediatric Homicides Related to Burn Injury: A Retrospective Review at the Medical University of South Carolina,” Journal Forensic Science 51, no. 2 (2006): 396–399, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00066.x.

11 P. Ojo et al., “Pattern of Burns in Child Abuse,” American Surgeon 73, no. 3 (2007): 253–255, https://doi.org/10.1177/000313480707300311.

12 S. Hayek et al., “The Efficacy of Hair and Urine Toxicology Screening on the Detection of Child Abuse by Burning,” Journal of Burn Care and Research 30, no. 4 (2009): 587–592, https://doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181abfd30.

13 S. Dissanaike et al., “Burns as Child Abuse: Risk Factors and Legal Issues in West Texas and Eastern New Mexico,” Journal of Burn Care and Research 31, no. 1 (2010): 176–183, https://doi.org/10.1097/bcr.0b013e3181c89d72.

14 L. Wibbenmeyer et al., “Factors Related to Child Maltreatment in Children Presenting with Burn Injuries,” Journal of Burn Care and Research 35, no. 5 (2014): 374–381, https://doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0000000000000005.

15 E.I. Hodgman et al., “The Parkland Burn Center Experience with 297 Cases of Child Abuse from 1974 to 2010,” Burns 42, no. 5 (2016): 1121–1127, https://doi.org/s0305-4179(16)00071-1.

16 M.C. Pawlik et al., “Children With Burns Referred for Child Abuse Evaluation: Burn Characteristics and Co-existent Injuries,” Child Abuse and Neglect 55 (2016): 52–61, https://doi.org/S0145-2134(16)30037-0.

17 Z.J. Collier et al., “A 6-Year Case-Control Study of the Presentation and Clinical Sequelae for Noninflicted, Negligent, and Inflicted Pediatric Burns,” Journal of Burn Care & Research 38, no. 1 (2017): E101-E124, https://doi.org/10.1097/bcr.0000000000000408.

18 S. Vazquez et al., “Patterns for Child Protective Service Referrals in a Pediatric Burn Cohort,” Curēus 16, no. 1 (2024): e51525, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.51525.

Previous studies were most commonly cited to discuss specific burn patterns as an indicator of intentional scalds. Of the ten articles citing prior studies to support specific burn patterns as an indicator, seven identified immersion burns, five identified bilateral burns, and three identified forced immersion burns. Even though immersion burns were not observed in Hodgman et al.’s study, the article endorsed this specific burn pattern as an indicator.Reference Hodgman 72 Previous findings that burns located on lower body parts indicate intentional burns were also cited in four studies, with all four identifying the buttocks/perineum and three identifying the feet. However, Dissanaike et al. reported low rates of both immersion and buttocks/perineum burns and cited prior studies to emphasize this inconsistency.Reference Dissanaike 73

Mixed development of evidence was noted for younger age and male sex as indicators of intentional burns. Although three studies supported previous findings that intentionally burned children are younger than unintentionally burned children, the most recent study in our review found no difference in age between intentionally and unintentionally burned children.Reference Collier 74 Only one study supported previous findings that children with intentional burns are more likely to be male, while four studies have contrarily suggested no sex differences, one of which posited that study design contributed to earlier observations.

Quality Assessment

Using the JBI checklists 75 across the 18 studies, quality scores for cross-sectional designs varied the most, ranging from 2–7, with an average score of 3.9 out of 8. The two case-control designs scored 6 and 8 out of 10, and the three cohort designs scored 5, 6, and 8 out of 11. High scores for the checklists indicate good quality. Most primary studies clearly described the study participants, setting, and measurements for potential indicators of intentional scald burns using valid and reliable methods. Scores were limited in almost all studies for using retrospective analyses of medical charts; however, this study design is the most feasible for examining intentional scalds due to the rare nature of these events. Older cross-sectional studies scored particularly low for failing to specify and consider confounding factors. In the case-control and cohort studies, scores were also impacted for failing to report exposure or follow-up time.

Methods of Classifying Intent

The JBI checklist 76 quality scores for many articles were particularly impacted for failing to measure intentional scalding in a valid way. Of the 18 primary studies, only 4 relied exclusively on state investigations or the confession or conviction of a perpetrator to determine intentional scalding. The majority of studies measured intent via clinician diagnosis or review by a multidisciplinary child abuse team, a child abuse pediatrician team, a social work team, or the authors. One study 77 specified that its multidisciplinary child abuse team used Stone et al.’s recommended diagnostic criteria 78 to determine child abuse, and another specified that the diagnosis of abuse included specific burn patterns; 79 however, most did not describe the assessment methods or procedures employed to make the diagnosis. A few studies provided criteria from which abuse was determined, such as “physical findings,” 80 but did not explain how the criteria were applied in the study. Additionally, some studies reported using a combination of methods to classify intent, such as “state investigation or diagnosis by child abuse pediatrician,” 81 but failed to specify which patients were classified using each method.

Vazquez et al. uniquely collected data both on patients who received Child Protective Service (CPS) referrals during hospitalization and those who received CPS intervention after investigation.Reference Vazquez 82 Of the 28 scald patients who were referred to CPS, only 1 case was substantiated.

Discussion

Once clinicians have reported suspected intentional injuries to CPS or law enforcement based on burn indicator criteria, they are required to assist investigators by providing medical records if requested. 83 The parent or guardian is then at risk of criminal charges under the state’s child abuse or child neglect statutes. Multiple elements must be met to convict an individual of either charge. For instance, child abuse statutes require (1) the presence of an injury — scald burns causing physical injury or death to the child meet this requirement — and (2) the determination that the individual under investigation (e.g. parent or guardian) acted intentionally. 84 Requirements for child neglect charges vary more widely among the states than abuse requirements. Some state statutes require individuals under investigation to have acted intentionally to a degree (e.g., acted negligently, knowingly, or intentionally), while others include actions such as failure to provide proper care.Reference Mateyka and Yoo 85 Across all child neglect statutes, the individuals under investigation risks or actions must be determined to be unreasonable. 86

The outcome of assessing intentionality in suspected child abuse or neglect cases relies strongly on the approach applied.Reference Lynøe and Eriksson 87 In cases of scald injury, this determination has often relied on the approach that only intentional burns can produce the traditional indicators of intentional scald burns. 88 This approach uses a common assessment of medical records indicating the child’s injury location, injury appearance, and social and historical background. Applied to all cases where a clinician determines that a scald burn is intentional, this approach would likely lead to criminal charges for the party responsible.

However, an alternative approach offers additional methods of assessing intentionality for child scald burns. This approach accounts for the possibility that traditional indicators of intentional scalds were caused unintentionally and reasonably due to water heater settings, the absence of a temperature limiting device, or ignorance of scald burn treatment and severity. For example, in homes where water can become excessively hot, parents or guardians may lack awareness that the risk can be reduced by adjusting their water heater’s temperature setting. Yet even homes with a water heater set at the recommended 120°F can dispense water at much higher temperatures if a temperature limiting device is not installed. 89 According to the ASSE, water heaters are not intended to control temperatures at the point of use; unlike air heating systems, they do not limit maximum temperatures to the gauge setting and therefore may release overheated water. 90 When water is turned on in this situation, scald injury characteristics traditionally associated with child abuse can occur in seconds. In the absence of an alternative explanation, the presence of traditional indicators could lead to a parent or guardian being charged and convicted of abuse without meeting the requisite criminal intent.

In this systematic review, the following characteristics were indicative of intentional burning in scald injuries: tap water as the causal agent; immersion or bilateral injury pattern; buttocks/perineum or feet injury location; child aged two years or younger; and child of a low-income household. Characteristics that were shown to indicate intentional burns but warrant further research in scald injuries specifically include delay in seeking care, historical inconsistencies, large and deep injury, and additional injuries. Taken together, this profile of intentional scalds reflects the earliest description published by Stone et al. 91 and Lenoski et al. 92 in the 1970s and has remained relatively consistent over time. 93

The earliest description of intentional scalds had a strong impact on the criteria applied by clinicians and CPS investigating suspected cases of child abuse. In the absence of a gold standard to determine intentional burns, subsequent research used diagnoses made by clinicians and CPS as a “reference test” to examine further characteristics that could indicate intentional scalds. However, calculating diagnostic accuracy requires that the “reference test” is independent of the “diagnostic test.” Using a reference test that overlaps with the diagnostic test can result in a procedure referred to as circular reasoning. 94 For example, if a study considers immersion burns as the “diagnostic test” for intentional burns without realizing that the child abuse diagnosis as the “reference test” was determined in part by assessing the presence of immersion burns, the accuracy of the diagnostic test will be overestimated.

Following this guideline for calculating diagnostic accuracy, researchers would ideally separate child abuse diagnoses from the burn characteristics measured in their observational studies. However, two studies in our review described employing methods of classifying abuse based on the earliest description, and most others failed to report methodological steps that would ensure classification was not also subject to unintentional bias. Findings from studies using child abuse diagnoses would be accepted if the basis of early descriptions was adequate, but quality assessments demonstrate that the earliest studies in the field were poor quality, in that they lacked comparison groups, adequate sample sizes, and statistical rigor. Even recent, more rigorous studies in this review suggest that high rates of certain characteristics in prior samples could be attributed to overestimation due to being widely publicized indicators of abuse. 95

Observational studies, and consequently the diagnostic criteria used by clinicians and CPS, have focused primarily on the injury patterns, demographic features, and historical details associated with intentional scalds. However, there is no indication that the authors considered how the depth of the bathtub or sink, setting of the water heater, or temperature of the water at the time of the scald impacted injury patterns. We hypothesize that they may not have been aware how common extremely hot water is in many homes. No primary studies explain how a burn from unintentionally placing a child in water at 140°F would present differently from the early description of immersion patterns. When children are exposed to water hotter than the CPSC-recommended temperature limit, scald injuries with the immersion pattern develop quickly: water at 140°F can nearly instantaneously create the same burn as water at 120°F where a child is held still for 10 minutes. 96

Much of the literature suggests clinicians and CPS pay attention to historical details and care-seeking behaviors of parents when determining abuse. However, a strong body of evidence demonstrates that parents and the public have poor knowledge of burn risks and treatment. 97 A mistake of fact, such as a mistake of the seriousness of a child’s scald burn, may be a defense for child neglect. Proving that parents made this mistake of fact is a difficult defense to proffer in potential child neglect cases, especially when the scald burns present in the traditional patterns of intentional burns. Once again, the indicators of intent could lead to a parent or guardian being convicted of neglect without the requisite intent.

Several studies in our review suggested clinicians should consider social factors related to income, including race and relationship status of the parent, in their assessments of intentional scalding. This recommendation has likely impacted CPS referrals: Vazquez et al. found that Black race and area deprivation index were associated with CPS involvement in a pediatric burn cohort, but less than 10% of these CPS cases were substantiated. 98 The conclusion that low income is an indicator of intentional scalding is complicated by a policy landscape that has put low-income families at greater risk of tap water burns. Low-income families are more likely to live in older housing, which lack important safety features: homes built before 1986 are excluded from housing codes that require temperature-limiting devices, and water heaters installed before 1988 were not subject to the industry’s voluntary temperature standard.Reference Swope and Hernández 99 Low-income families are also more likely to live in rental properties, which have been associated with higher tap water temperatures in observational studies.Reference Gilman 100 In these homes where tap water can reach excessive temperatures, children are more likely to experience scald injuries, including those that may present with traditional indicators of abuse. To better understand the relationship between scald injury, child abuse, and income, further analysis of child scald burn cases by sociodemographic characteristics should be conducted.

Given the failure of primary studies to consider the possibility of water exceeding 120°F and the estimated 41% of homes lacking protection from this scald risk, we recommend a reconsideration of the current clinical and criminal paradigms used to understand pediatric scald burns. 101 Such a reconsideration is necessary to ensure families living in low-income homes are not facing increased suspicion due to structural housing factors beyond their control and is consistent with the growing acknowledgement of the influence of structural factors on injury risk. 102 A more holistic approach to determining intentionality would also support efforts to address concerns about the lack of training in criminal justice and CPS systems around the structural factors associated with scald burn injuries and based on the reliance on early studies potentially equating poverty with child abuse or neglect.Reference Pimentel 103 More comprehensive efforts to prevent scald burn injuries would fully consider social policies that would enable more low-income families to overcome the financial challenges of parenting. We further recommend that law enforcement and CPS investigating suspected child abuse cases be trained about (1) the time to scald burn when water exceeds recommended temperatures and (2) the allowable variation between set temperature and release temperature from water heaters when considering charges. Additionally, we recommend that investigators add a photographic recording of set temperature and a record of any scald protection devices at the tap to their investigative protocols to more fully capture the unintentional risk of scald burns in homes of injured children.

Findings from this review have broader implications for consumer protection and housing policy in the US, as well as future directions for research. Currently, building codes in some states require thermostatic mixing valves in new buildings and as part of plumbing system upgrades, but not with water heater replacements. 104 A requirement to install mixing valves with water heater replacements at the state and federal level would facilitate widespread use of this scald prevention technology in homes where the risk of both intentional and unintentional childhood scalds is elevated. Another approach to addressing scalds in the highest-risk children is through rental assistance programs. For example, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD’s) Housing Choice Vouchers program requires regular safety inspections in participating homes, but these inspections currently do not cover tap water temperatures. 105 We recommend that HUD includes water testing as part of their inspection and ensures that homes with unsafe temperatures adjust those water heater temperatures and install mixing valves, a process that can serve as a model for state and local programs. Parental educational interventions are another potential approach to lowering water temperatures but relative to policy solutions, education may have particularly limited effectiveness in rental properties where the landlord’s permission is often required to make changes to the home water system. In addition, decades of injury prevention research and practice provide evidence of the benefits of passive protections relative to interventions that require regular maintenance to realize safer environments. To inform legislative steps to prevent both intentional and unintentional scalds in children, future work should address the current gap in primary research focused on the association between housing characteristics and intentional childhood scalds. Qualitative studies that engage with clinicians, law enforcement, and CPS to further understand how suspected cases of intentional childhood scalds are investigated and decided can provide a valuable complement to the current literature. In addition, qualitative methods can also be used to identify opportunities for considering the role of structural factors in scald burns among children.