Civil society and its agents have seen their space for activity limited across both democracies and other political regimes (Anheier et al. Reference Anheier, Lang and Toepler2019; Bloodgood et al. Reference Bloodgood, Tremblay-Boire and Prakash2014). In particular, hybrid political regimes have attempted to shape a civil society sector that aligns with the regime’s needs (Hale Reference Hale2010; Karl Reference Karl1995; Owen and Bindman Reference Owen and Bindman2017; Wilde et al. Reference Wilde, Zimmer, Obuch and Sandhaus2018). Hybrid regimes are also referred to as participatory authoritarian (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2012; Owen Reference Owen2018; Xiaojun and Ge Reference Xiaojun and Ge2016). They combine characteristics of participatory democratic governance such as regular elections with authoritarian tendencies such as a dominant party of power and/or restrictions on civil liberties such as limits on press freedoms and/or limits on freedom of association (Diamond Reference Diamond2002; Wigell Reference Wigell2008). In line with such tendencies, hybrid regimes seek to align civil society with their own goals, through restricting the public sphere and setting clear boundaries on the activities civil society agents, including non-profit organisations (NPOs), can pursue (Karl Reference Karl1995; Wilde et al. Reference Wilde, Zimmer, Obuch and Sandhaus2018). Thus, hybrid regimes tend to focus on shaping the scope of NPOs activities in particular of those that can challenge governance arrangement. A key aspect to this is restricting organisational engagement in activities that in the literature would fall under the advocacy umbrella (Almog-Bar and Schmid Reference Almog-Bar and Schmid2014) and which could be termed as big ‘P’ politics; that is to say, activity aligned to party politics, (shaping and influencing) policymaking, or attempts to hold the state to account (Hale Reference Hale2010; Richter and Hatch Reference Richter and Hatch2013; Shapovalova Reference Shapovalova2015; Spires Reference Spires2011). This also enables hybrid regimes to demark what is considered to be ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ civil society (Daucé Reference Daucé2015).

Despite these restrictions, NPOs continue to play a role in governance arrangements within hybrid regimes (Guo and Zhang Reference Guo and Zhang2014). Hence, hybrid regimes encourage some type of NPOs, frequently via resource provision to provide welfare services (or what could be considered the right sort of civil society). However, to provide these services also means that NPOs have to demonstrate their relevant organisational strength and engage in what could be termed small ‘p’ politics. Small ‘p’ politics requires engagement with constituencies and clients as well as or broader public and building and managing of networks that help to navigate their operating environment, help to determine how policy is deployed even if the policy itself cannot be influenced. As a result, NPOs become ‘apolitical helpers’ (Kulmala Reference Kulmala2016, p. 200). Similarly, Ljubownikow and Crotty (Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2016) observe that NPOs in the Russian Federation strategically frame themselves as apolitical to make it easier to interact or even become part of state structures. This, in turn, gives them access to resources and allows them to exert influence over public policy deployment. Therefore, despite what seems to be rather clear boundaries for NPO activity (i.e. ‘don’t be Political’; engage in the ‘right’ type of civil society activity), their welfare provision role does give such organisations potential political (small ‘p’) power. Riley and Fernandez’s (Reference Riley and Fernández2014) propose that path-dependent influences of past regime arrangements shape civil society. Specifically, they highlight how the past impacts civil society arrangements in post-dictatorial contexts, many of which are now characterised as hybrid regimes (Riley and Fernández Reference Riley and Fernández2014). In such contexts, NPOs might lack autonomy from the state to be Political—to shape policy, either locally or nationally, to challenge the status quo, or effectively hold state authorities to account. But they still have organisational strength, that is to say, political power to influence how policy is deployed and to negotiate the associated networks therein. As such, they can still contribute to society both by providing welfare services (often their core mission) and also by facilitating good (if not necessarily democratic) governance (Riley and Fernández Reference Riley and Fernández2014).

These considerations lead to our research question; how do NPOs in hybrid regimes use ‘mundane’ day-to-day activity of providing (welfare) services to affect change in their immediate environment? To explore this question, we focus on NPOs organisational strength and whether it provides them with small ‘p’ political power.

To examine this, we use an activity lens. An activity lens enables micro-level focus and aims to explore what organisations do, rather than what they ought to be doing based on certain normative conceptions (Cohen and Arato Reference Cohen and Arato1994). This approach also enables us to link such micro-level explanations to macro-phenomena (Sivunen and Putnam Reference Sivunen and Putnam2020; Whittington Reference Whittington2006). Given our focus on the role of civil society in a hybrid regime (i.e. understanding how NPOs act within this institutional context) and whether and how NPOs might activate the citizenry [i.e. getting individuals to do civil society thus to engage with them (Vorbrugg Reference Vorbrugg2015)], in this paper, we are primarily concerned with external activities of such organisations. We draw on Riley and Fernández (Reference Riley and Fernández2014) who suggest the need to distinguish between organisational strength and organisational autonomy. The post-dictatorial context of Italy and Spain indicates that democratic reforms do not automatically lead to NPO autonomy and that they can remain heteronomous (i.e. subject to external control) within such contexts (Riley and Fernández Reference Riley and Fernández2014). However, organisational strength might provide NPOs with some basis to engage with the state as part of small ‘p’ politics thru access to elites and their associated resources, and the deployment of such networks, improving the experience of their constituents and governance within a set legislative context as a result.

To examine organisational strength and heteronomy in more detail, we study NPOs in the Russian Federation. We have selected the Russian Federation due to the hybrid nature of its regime (Hale Reference Hale2010), because Russian civil society has historically been characterised as weak (i.e. lacking organisational strength) (Henry and Sundstrom Reference Henry, Sundstrom, Evans, Henry and Sundstrom2006); NPOs are seen to have squandered their opportunity to build a functioning third sector (i.e. influencing governance arrangements and activities), following the Soviet Union’s collapse nearly 30 years ago (Robertson Reference Robertson2009). However, more recently some researchers have observed more dynamism amongst Russian civil society actors (Bogdanova et al. Reference Bogdanova, Cook and Kulmala2018; Skokova et al. Reference Skokova, Pape and Krasnopolskaya2018; Tarasenko Reference Tarasenko2018), but still, consider their capacity vis-à-vis democratising Russia’s authoritarian regime as limited (Berg-Nordlie and Bolshakov Reference Berg-Nordlie and Bolshakov2018; Flikke Reference Flikke2018; Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2016; Moser and Skripchenko Reference Moser and Skripchenko2018; Owen Reference Owen2015; Owen and Bindman Reference Owen and Bindman2017; Tysiachniouk et al. Reference Tysiachniouk, Tulaeva and Henry2018). Further, the Russian Federation and its attempt to control or limit the scope of civil society agents is also mirrored in other hybrid regimes and authoritarian contexts (Richter and Hatch Reference Richter and Hatch2013; Spires Reference Spires2011; Xiaojun and Ge Reference Xiaojun and Ge2016). This makes the Russian Federation an illuminating context to explore issues of organisational strength and heteronomy. Focusing on Russian NPOs enables us to explore the specificities of the Russian Federation and gain some potential representative insights about hybrid regimes and civil society and organisations therein. This enables our paper to broaden the understanding of civil society and its arrangements in contexts hostile to its existence. In presenting our insight, we first provide a concise overview of research on Russian civil society. We then present our research study before illustrating our key insights. Our paper finishes with a discussion and conclusion of our insights.

Civil Society in the Russian Federation

The extant literature portrays Russian NPOs as organisationally weak and heteronomous confirming the negative outlook for Russia civil society illustrated by Linz and StepanFootnote 1 back in 1996. The majority of past and more current studies of Russian NPOs highlight an institutional context hostile to NPOs (Crotty et al. Reference Crotty, Hall and Ljubownikow2014; Daucé Reference Daucé2015; Flikke Reference Flikke2018; Henderson Reference Henderson2008; Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2014; Salamon et al. Reference Salamon, Benevolenski and Jakobson2015; Skokova et al. Reference Skokova, Pape and Krasnopolskaya2018; Tarasenko Reference Tarasenko2018). Much of this past research has focused on the limits the institutional context placed on NPO activities, namely revenue controls and registration requirements (Crotty et al. Reference Crotty, Hall and Ljubownikow2014; Daucé Reference Daucé2015; Robertson Reference Robertson2009; Salamon et al. Reference Salamon, Benevolenski and Jakobson2015), restrictions on interaction with organisations abroad (Skokova et al. Reference Skokova, Pape and Krasnopolskaya2018), and limits on rights to protest and assembly (Johnson and Saarinen Reference Johnson and Saarinen2011; Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2016; Richter and Hatch Reference Richter and Hatch2013). At the same time, research has also highlighted deficiencies at the organisational level and presents Russian NPOs as parochial, disengaged from their constituencies, and a broader public that views them as irrelevant and untrustworthy (Chebankova Reference Chebankova2009; Crotty Reference Crotty2006; Henderson Reference Henderson2002; Henry Reference Henry2006; Spencer and Skalaban Reference Spencer and Skalaban2018).

Research also highlights that many Russian NPOs are reliant on the state to ensure survival, and as a result present them as being nationalised, emasculated, licensed, and/or agents of the state (Ljubownikow et al. Reference Ljubownikow, Crotty and Rodgers2013; Richter and Hatch Reference Richter and Hatch2013; Robertson Reference Robertson2009). In turn, Russian NPOs are unable to hold the state to account in a meaningfully way and contribute little to democratisation (Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2017). However, there are notable exceptions to the above. For example, research on the women’s rights movement has indicated that although organisations are limited when it comes to democratisation, they can still have some societal impact (Hemment Reference Hemment2004, Reference Hemment2007). Similarly, research focusing on NPOs providing welfare services paints a brighter and more colourful picture in particular with regard to organisational strength and advocacy (Henry Reference Henry2012; Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2016; Pape Reference Pape2018; Skokova et al. Reference Skokova, Pape and Krasnopolskaya2018). Such organisations have been able to carve out a distinct space for social if not Political activity (Skokova et al. Reference Skokova, Pape and Krasnopolskaya2018).

Nonetheless, Russia’s hybrid regime continues to restrict what NPOs can do. The Russian state has continued with legislative developments to ensure heteronomous control of NPOs (Flikke Reference Flikke2018; Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2014; Moser and Skripchenko Reference Moser and Skripchenko2018) as well as creating competition for resources (Daucé Reference Daucé2015; Fröhlich and Skokova Reference Fröhlich and Skokova2020; Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2017; Salamon et al. Reference Salamon, Benevolenski and Jakobson2015; Skokova et al. Reference Skokova, Pape and Krasnopolskaya2018). In turn, this has led NPOs to become an integral part of the state’s welfare provision, through their engagement and participation in social contracting schemes (Benevolenski and Toepler Reference Benevolenski and Toepler2017; Tarasenko Reference Tarasenko2018). However, authors have observed that the welfare-oriented action of NPOs has been able to challenge some practices associated with public policy decisions and influenced how public policy has been deployed at a regional and local level (Berg-Nordlie and Bolshakov Reference Berg-Nordlie and Bolshakov2018; Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2016). This, in turn, suggests that despite the restrictive nature of Russia’s institutional context which constrains opportunity for political protest or to challenge the state (Daucé Reference Daucé2015; Henry Reference Henry2012; Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2016; Tysiachniouk et al. Reference Tysiachniouk, Tulaeva and Henry2018), NPOs have the ability to organise and thus do have organisational strengths.

The collaboration and close integration between the Russian state and welfare NPOs (i.e. the right type of organisations) can trace its roots to the socialist self-management system of the Soviet Union (Vetta Reference Vetta2018). Despite the emergence of many social welfare organisations during the 1990s (Cook Reference Cook2007; Fröhlich Reference Fröhlich2012; Jakobson and Sanovich Reference Jakobson and Sanovich2010; Kulmala and Tarasenko Reference Kulmala and Tarasenko2016), recent insights suggest that the most effective social welfare NPOs are now those with the right combination of capabilities and resources to ‘do’ good for their constituencies and the ability to navigate their networks and relationships with relevant state authorities (Bogdanova et al. Reference Bogdanova, Cook and Kulmala2018; Skokova et al. Reference Skokova, Pape and Krasnopolskaya2018; Tarasenko Reference Tarasenko2018). It is fair to assume that welfare NPOs will have always had capabilities to organise and thus organisational strength, but that the institutional context of the 1990s was not conducive to leverage those. However, in the current institutional context of constraint space for civil society actors and legacies of welfare NPOs working with the state, it now enables such organisation to use their day-to-day activities (i.e. organisational strength) to advance relevant issues within the structure of the state. This organisational strength has put key individuals in charge of welfare NPOs at the intersect between the state and civil society and thus in a position to operate spaces of power (Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2017). In turn, this highlights that NPOs might have the potential to instigate changes working within the regime and its confines (Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2016; Owen Reference Owen2015; Owen and Bindman Reference Owen and Bindman2017). Thus, in this study, we draw on data collected from a subsection of welfare focused NPOs, namely those addressing on health-related issues (hNPOs) to explore if such social oriented organisations can use their day-to-day activities to demonstrate organisational strength. We outline our research study below.

The Research Study

In order to address our research question of how NPOs in hybrid regimes use their day-to-day activity of providing (welfare) services to potentially effect change, our data collection process aimed at establishing the modus operandi of hNPOs. To encourage hNPOs to illustrate what they do, we operationalised semi-structured interviews with key decision-makers as a key data collection technique. We supplemented this, also to triangulate respondents’ illustrations, with observations. One of the researchers spent an average working week with each organisation. Observations and any informal conversations during this period were recorded in an extensive daily research diary (Miles and Huberman Reference Miles and Huberman1999). Hence, this qualitative approach enabled us to explore how key decision-makers portrayed their activities and how they saw them being operationalised both in terms of demonstrating organisational strength as well as political engagement (which as we illustrate in our findings section was mainly that of the small ‘p’ kind).

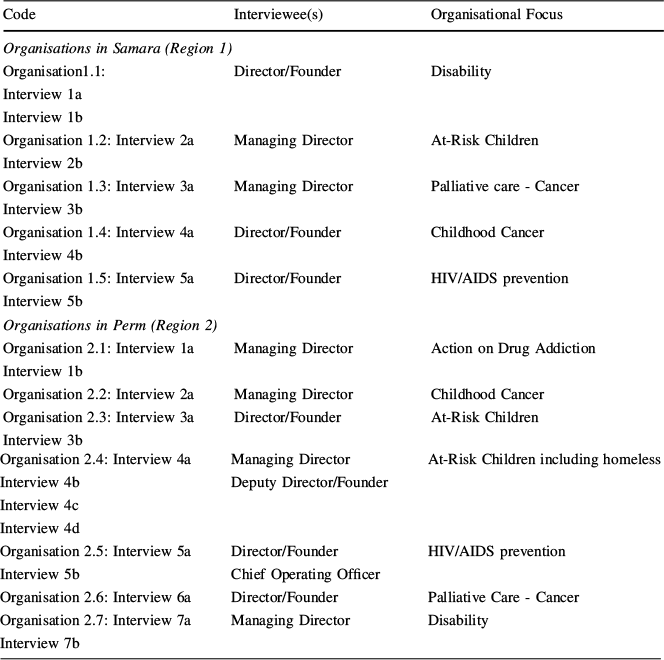

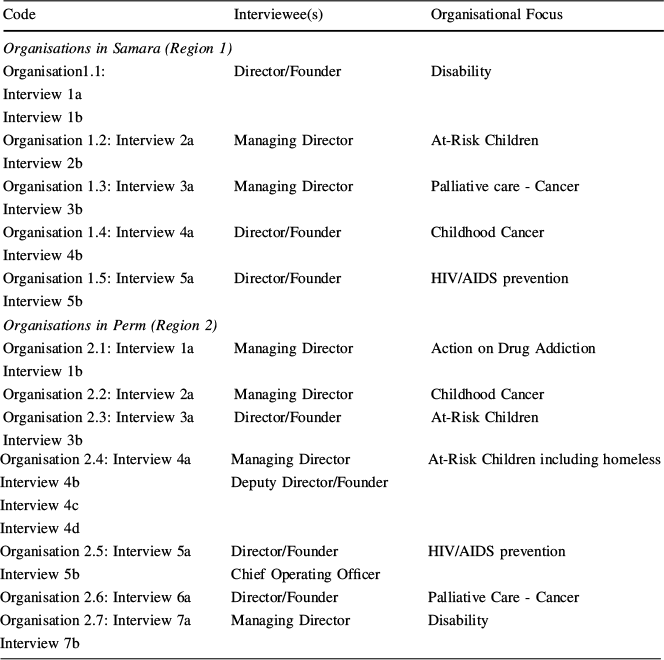

We carried out 24 interviews across 12 organisations. We focused on organisations located in regional capital cities outside the urban centres of Moscow and St. Petersburg as they are said to be unrepresentative of most of Russia (Javeline and Lindemann-Komarova Reference Javeline and Lindemann-Komarova2010). Our study focused on the two regional centres of Perm and Samara (see ‘Appendix A’). Perm city is the regional capital of the Permsky Kray (Perm Region), which is dominated by extractive industries such as oil. The city of Samara is also the regional capital to Samarskaya Oblast (Samara Region), which is a centre for manufacturing, in particular, automotive (Federal State Statistics Service 2010). We focused on organisations in regional capital cities where they were greater in number, and because regional capitals exhibit a concentration of state authorities and thus the potential of incidents of big ‘P’ and/or small ‘p’ politics. We purposefully select organisations (Siggelkow Reference Siggelkow2007) based on their activities and objectives focusing on what is considered health/healthcare (zdravookhraneniye) issues in Russia and whether or not they understand themselves as obshchestvennyye organizatsii. Obshchestvennyye organizatsii can be translated to mean social or societal organisations—a widespread term both Russian NPOs and the Russian state use to describe NPOs both in law and colloquially (Spencer Reference Spencer2011). This approach also allowed us to create matched pairs, in the area of drug abuse/prevention and HIV/AIDS, disability, palliative care, and children living with cancer.

We drew on Gioia et al. (Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013) when designing interview questions as well as using ethnographic interview techniques focusing our open-ended, non-leading questions on everyday organisational activities. Interviews were done with organisational leaders, as similar to the majority of Russian NPOs, and hNPOs in this study were small in size (only a few had any paid staff) with organisational cultures dominated by ‘democratic centralism’—where the leader’s ideas are adopted by full staff/member consent (Spencer Reference Spencer2011, p. 1080). Interviews were conducted in Russian and lasted on average 1 h. Organisational documentation (publicly available as well as internal when supplied by organisations) was used to triangulate and validate interview responses and observations (Miles and Huberman Reference Miles and Huberman1999). Reflecting best practice for qualitative research, our data analysis process and data collection process overlapped, allowing for feedback from data analysis into the data collecting process (Gioia et al. Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). To aid analysis, all interviews were transcribed and translated into English using a professional translation and transcription service. We began the analysis with open coding the interview transcripts, which produced using first-order codes (Gioia et al. Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). Initial codes covered various specific activities organisations engaged in. As coding progressed iteratively, we consolidated these first-order codes into more abstract second-order themes elaborating organisational strength, organisational autonomy (Riley and Fernández Reference Riley and Fernández2014) and how and if hNPOs engage the wider public.

Complementing our data coding, we also engaged in constant a comparison to facilitate the identification of differences and similarities in data segments and respondents. For example, by comparing one organisation’s account of what they do with that of others, we were able to detect similarities with regard to organisational strength, organisational autonomy, or engagement with the wider public. In presenting our findings, we draw on hNPOs main activities for structure and use excerpts from interviews as ‘illuminating examples’ (de Vaus Reference de Vaus2001, p. 240) and supplementing it with observational notes from our research diary.Footnote 2

Findings

Similar to other recent research (Moser and Skripchenko Reference Moser and Skripchenko2018; Skokova et al. Reference Skokova, Pape and Krasnopolskaya2018; Tarasenko Reference Tarasenko2018), we found Russian hNPOs to be dynamic and successful at carving out operating spaces for their welfare service provision. In extending this emerging insight, we also found that Russian hNPOs have been successful in influencing public policy deployment. However, echoing findings by Kulmala (Reference Kulmala2016), groups were very keen to stress that they did not engage in Politics (i.e. specific party politics, influencing policymaking, or holding the state to account) but focused on what they perceived and portrayed as apolitical activities. HNPO in our study thus submitted themselves to the heteronomous power of the state (Riley and Fernández Reference Riley and Fernández2014) and aligned themselves, and their activities with what they believed were the explicit or implicit requirements of the state (see Moser and Skripchenko Reference Moser and Skripchenko2018 for a similar insight amongst rights-focused organisations).

For hNPOs in this study, their day-to-day activities presented themselves as a good way to demonstrate their organising capabilities. In turn, this enabled hNPOs to promote themselves as viable partners with whom the state or its representations could engage in collaborative projects. This later engagement then opened up opportunities for hNPOs to engage in activities with potential effects on governance and governance arrangements, where they did not expect a negative response from the state or its representations (Tarrow Reference Tarrow1989) or even perceived the state’s receptiveness for input. Thus, to answer our research question as to how hNPO use their organisational strength, we explore what hNPOs do in more detail below.

Core Service Provision

As would be expected from organisations focusing on welfare services, hNPOs focused primarily on providing services that would improve their constituents’ life experiences. To do so, hNPOs aimed to supply specialist services such as access to ‘counselling’ (2.1a; 2.4a), ‘doctors…medication…moreover, social workers’ (2.5a), ‘rehabilitation equipment’ (2.2a), ‘legal services’ (2.5a) and even organised immediate free medical treatment for a children’s homeless shelter (Observation Notes). HNPOs were also working with underrepresented societal groups providing services aimed at ‘giving them a chance’ (1.1a) and an opportunity for constituents/clients to ‘improve their skills’ (2.7a) or develop new ones such as computer skills for pensionaries or conflict-solving skills for young offenders (Observation Notes from relevant events). Extending their service provision, hNPOs also engaged in activities to entertain their constituents such as ‘outings for children’ (2.2a; 1.2a), ‘prom dances’ (2.3b), ‘puppet theatre, chorus and other activities’, (2.7a), ‘summer camps’ (1.4a) and ‘sporting competitions’ (1.4b).

Another core part of their welfare activities for organisations in this study was what they termed ‘educational’ (1.4b) services. Other than the activities outlined above, which aimed at skill development of their constituencies, these services were aimed primarily at employees at state institutions that dealt with their constituency groups. At the core of these activities was the aim to improve the understanding within individuals and state structures of their constituents/clients, their needs and ultimately influence the practices used to engage with them. Here hNPOs in this study highlighted how they trained professionals from state institutions such as ‘teachers’ (2.3a), ‘doctors’ (1.3a), ‘medical staff’ (1.5a), ‘social workers and school psychologists’ (2.1a), in areas such as ‘pain management’ (1.3a) and ‘drug prevention’ (2.5a) and demonstrating them how to change operational-level practices within state institutions. To support the latter, respondents also emphasised that they engaged in co-production of material on ‘the benefits of physical therapy’ (1.2a), a leaflet highlighting ‘legal issues [for those] working with foster families’ (2.3a), or campaigns on drug prevention (2.1), which state institutions were able to use for their staff. Some hNPOs also highlighted how this had enabled them to act on behalf of the regional health authorities. Respondents illustrated that they distributed ‘lubricants, condoms and disinfecting wipes’ (2.5a) to sex workers, providing ‘mobility equipment’ and ‘specialist employment services for the disabled’ (1.1a), collecting and distributing ‘school supplies’ (2.3a), or operating an ‘ex-offender support service’ (2.5a). For hNPOs, this was evidence that they possessed organisational strengths that were valued by state authorities as well as constituency access (informal conversation with Chief Operating Officer during event observation, 2.5). HNPOs engaged in these educational services as well as taking on services usually provided by the state, can be seen as hNPOs leveraging this organisational strength into what can be characterised as small ‘p’ politics, that is to say, influencing practices of state institutions with regard to how they engage with their constituency and in effect improving governance.

The core service engagements illustrated by hNPOs in this study indicates an emerging mutual dependency between NPOs and the Russian state (Salamon et al. Reference Salamon, Benevolenski and Jakobson2015). HNPOs have been able to leverage this mutual dependency (the state needs to address health issues and provide services, and hNPOs can organise and access marginalised societal groups) to engage in drug misuse prevention or working with ex-offenders and sex workers. Those are all areas that have traditionally been difficult to access for such organisations in the Russian Federation (Owen Reference Owen2015; Titterton Reference Titterton2006). Russian hNPOs in our study used their organisational strength to contribute to Russian society by delivering their core services (that is fulfilling their mission), broadening the scope of those services, and improving how relevant state actors engaged with their constituencies. To some extent, this reflects path dependencies from the Soviet period, where social organisations, although under very strong heteronomous control of the state, did provide engagement opportunities for specific groups as well as their representations in local governance arrangements (e.g. the blind, the deaf, the disabled, and veterans (Fröhlich Reference Fröhlich2012; Kulmala and Tarasenko Reference Kulmala and Tarasenko2016; Thomson Reference Thomson, Evans, Henry and Sundstrom2006). However, it also shows that the scope for hNPOs to engage in more than service delivery was limited. Instead, as we illustrate below, organisations focused on raising awareness of their core remit and engaging in humanitarian assistance.

Awareness-Raising and Humanitarian Assistance

Respondents considered both these types of activities—awareness-raising and humanitarian assistance—as additional to their core engagements of providing welfare services, but as we show below, they also provided some basis for small ‘p’ politics. HNPOs aimed to combine the aim of raising awareness for themselves with that of increasing the understanding of their constituents/clients amongst the public. The description below by organisation 1.4 characterises the types of activities hNPOs engage in.

We organised an exhibition. We have provided all the information about where do the kids get treatment, about the survival rate, and rehabilitation process…We try to inform the public, get them interested in joining that [donor] register… we do this through publications in newspapers and magazines, or TV programs (1.4a)

Frequently, path-dependent social conventions formed a cornerstone to such engagements. Specifically, hNPOs aimed to draw on historical legacies and replicate Soviet traditions of commemoration by targeting awareness-raising events around days and events that formed an important part of everyday life in the Soviet period (Danilova Reference Danilova2016) such as ‘Cosmonautics Day’ (1.2a), ‘International Childhood Cancer Day’ (2.2a), International Women’s Day, or International Labour Day. Often such events or days are either public holidays or still play an important role in commemorating the past, and thus, hNPOs aimed to capitalise on those by organising concerts (2.2a; 2.7a) or award ceremonies (2.3a, 1.1a, 1.2a). Organisations organised concerts or award ceremonies as both celebrations of their work [‘we just let everyone know that we exist’ (2.2a)] but also to illustrate the ‘plight’ of their constituents/clients to the wider public [‘a big event for all the kids graduating orphanages in Perm Krai’ (2.3a)] and thus frequently invited local media (Observational notes from research diary). These events demonstrated how hNPOs were able to use their organisational strength (i.e. organising capability) and mobilise cultural legacies in order to raise awareness of their constituency (and themselves). Although this does not challenge the state or hold it to account, it does enable hNPOs to raise awareness of relevant issues with state authorities and the public more widely.

Moreover, by drawing on cultural legacies of commemoration, hNPOs found it easier to demonstrate the neutral and apolitical nature of their events, demonstrating not just their organisational strength but the strength of Russian society (i.e. aligning with the nationalistic discourse promoted by the Putin administration). Respondents specifically emphasised that they were then able to use this for more regular engagement with ‘radio programs’ (2.1b), ‘advertised on [local] TV’ (2.2a), ‘publishing magazines’ (2.3a), and ‘Facebook and other social media’ (2.2a) to communicate their activities and how well they did them—raising awareness of themselves and their organisational strength beyond one-off-events. This can also be seen as an indication that organisations have begun to move beyond patronage, personalism, and tight group boundaries that have characterised post-Soviet Russian NPOs to date (Spencer Reference Spencer2011; Spencer and Skalaban Reference Spencer and Skalaban2018).

Reflecting on their rationale for engaging in raising awareness (both for their cause and themselves), hNPOs in this study also saw their engagement in humanitarian and charitable assistance as helping the profile of their organisations in addition to helping their constituencies. Such activities by hNPOs, be they focused on helping children or assisting drug users, focused on the collection and distribution of a wider range of donated goods or gifts including ‘clothes’ (2.3a; 1.2a), ‘toys’ (1.2a; 1.4a) ‘diapers and wipes’ (1.4a), or ‘books, furniture and appliances’ (1.2a). Organisations would also often link humanitarian engagement with their awareness-raising activities. In particular, they would use specific events to ‘announce that we need these products, [so that] people [could] bring them’ (1.4a). Two hNPOs in our study, both engaging with children with cancer, were also able to leverage this activity into ‘raising money’ (1.4a, 2.2a), in both cases for the treatment of individual children. However, other hNPOs in our study, in particular, those dealing with traditionally more contested issues (Rivkin-Fish Reference Rivkin-Fish2017; Titterton Reference Titterton2006) such as drug users, saw attempts at leveraging humanitarian engagements into raising money as ‘wasting our energy’ (1.5b, 2.5b) because drug addiction and use is not yet seen as a ‘general [accepted] humanitarian issues, [that] society is (…) willing to fund’ (2.1b).

Given the lack of philanthropic activities in the Soviet Union and persistently low levels of charitable donations since its disintegration (CAF Russia 2014), the ability of some groups to solicit donations (in-kind or monetary) is indicative of organisational strength that has thus far been considered lacking. This also allowed groups to engage with the wider public (Owen Reference Owen2015; Owen and Bindman Reference Owen and Bindman2017; Tysiachniouk et al. Reference Tysiachniouk, Tulaeva and Henry2018), countering the persistent negative connotation of NPOs in public discourse (Moser and Skripchenko Reference Moser and Skripchenko2018). This indicates positive spillovers from small ‘p’ political activity. However, this outreach falls into in what is perceived as politically safe or apolitical areas such as ‘the disabled, animal welfare or environmental issues’Footnote 3 (2.1b) or activity which resonates with the traditional Christian-Orthodox cultural values of helping the needy (e.g. children with terminal illnesses). Evidence of outreach that went beyond this was not evident in this study.

Conclusion

In this paper, we set out to examine Russian civil society and NPOs through an activity-based lens. We asked specifically, how do NPOs in hybrid regimes use day-to-day activities and their small ‘p’ political power that results from them to influence how policy is deployed in their immediate environment. We sought to identify the organisational strength of NPOs that are associated with day-to-day activities and how and whether this creates spillovers, improving governance arrangements [for example, changing practices (small p politics) or changing governance arrangements (large P politics)]. Our insights provide a more positive story about Russian NPOs dovetailing recent observations made by others (Bogdanova et al. Reference Bogdanova, Cook and Kulmala2018). We highlight how regulatory changes aimed at establishing control over NPOs specifically through provision of resources (Daucé Reference Daucé2015; Krasnopolskaya et al. Reference Krasnopolskaya, Skokova and Pape2015; Moser and Skripchenko Reference Moser and Skripchenko2018; Robertson Reference Robertson2009; Salamon et al. Reference Salamon, Benevolenski and Jakobson2015; Tarasenko Reference Tarasenko2018) have actually resulted in NPOs and the state working together in collaborative partnerships. Although discourse on organisational autonomy was largely missing from this study, organisations in this study were able to leverage their organising abilities (organisational strength) to work with and in some case for the state enabling to raise issues and change practices improving the life of their constituencies. Hence, the organisational strength of NPO provided them with political opportunities not only to make small changes from within, such as changing work practices within state-run service providers (Owen Reference Owen2015; Owen and Bindman Reference Owen and Bindman2017) but also built ties with state authorities which can, as others observed, help buffer against arbitrary institutional behaviour (Dieleman and Boddewyn Reference Dieleman and Boddewyn2011; Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2017). As a result, these hNPOs at least had manoeuvred themselves into a position from which they can now influence the lives of their constituencies, although their ultimate goal might not be democratisation, as the traditional conceptualisation of civil society assumes (Diamond Reference Diamond1999).

Our data also showed that hNPOs encouraged the public to engage in their activities and were able to, as also observed by others (Fröhlich and Jacobsson Reference Fröhlich and Jacobsson2019), use public events to mobilise support beyond their core service work (mainly humanitarian in nature), and thus more actively draw in outsiders to do civil society (Vorbrugg Reference Vorbrugg2015). In the longer run, this sort of activity might mean that the Russian public no longer views NPOs and other civil society agents as untrustworthy (Chebankova Reference Chebankova2009; Crotty Reference Crotty2006; Henderson Reference Henderson2002; Henry Reference Henry2006; Mendelson and Gerber Reference Mendelson and Gerber2007; Spencer Reference Spencer2011). Although organisations cannot demonstrate autonomy from the state by holding it to account or challenging it directly [i.e. being overtly political in a hybrid regime (Moser and Skripchenko Reference Moser and Skripchenko2018)], we highlighted that organisations had some autonomy over the activities they can engage in. This indicates that the Russian state clearly sees NPOs as having (social) relevance and value.

Our study of the Russian case also highlights that various factors (we illustrate some of the regulatory as well as cultural conditions) within hybrid regimes shape what can be seen as the operating space of NPOs. Thus, our paper also contributes to expanding our understanding of NPOs in hybrid regimes more generally. What the Russia experience illustrates is that civil society and its agents play an important role in the way in which hybrid regimes govern. However, the insight from the organisations in our study also suggests that NPOs in hybrid or authoritarian participatory regimes (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2012; Owen Reference Owen2018; Xiaojun and Ge Reference Xiaojun and Ge2016) can deploy tactics and strategies to influence public policy deployment (i.e. practices and how governance happens)—if not public policy itself (i.e. governance arrangements). By using the very restrictions placed on them to ‘control’ civil society (be apolitical welfare service providers), organisations can use their organisational strength and arising relationships with state actors to exert influence. Our findings indicate that short of banning third sector organisations altogether, it is impossible to exclude their influence on public policy entirely.

Our conclusions need to be seen in light of the limitations of this study. A larger sample, a different methodological approach, different areas of NPO activity and different regions may have provided other insights into the activities of Russian civil society organisations. Our focus on one sector in two regions also means that future research will need to focus on a more detailed exploration of organisational activities in less industrial regions and within different NPO sectors, particularly as we already indicate that those hNPOs engage engaged in political or social stigma find engagement in some types of activities less worth their while. We would also suggest that future research in Russia might also take a more gendered focus (Lyytikäinen Reference Lyytikäinen2013; Salmenniemi Reference Salmenniemi2005). Both women’s rights and hNPOs are dominated by female leaders and seemed to have been successful at demonstrating organisational strength and ‘managing’ Russia’s hybrid regime environment. Are NPOs led by men similarly successful? Future research will need to continue to be mindful that the Russian Federation spans a large geographic territory encompassing a myriad of cultural groupings that might affect the activities of NPOs. Furthermore, research will also need to look into other similar regimes to explore whether and the factors which influence whether NPOs are able to influence policy deployment to a greater or lesser extent than in the Russian Federation.

This notwithstanding, our paper extends an emerging understanding of how Russian NPOs and NPOs in hybrid regimes more generally exert influence despite the prevailing hostile environment created by a hybrid regime. Although hNPOs in our study succumbed to heteronomous power (Riley and Fernández Reference Riley and Fernández2014) and generally aligned their activities with what they perceive as explicit or implicit requirements of the state (Moser and Skripchenko Reference Moser and Skripchenko2018), they were still able to demonstrate organisational strength. Consequently, we find vibrancy at the organisational level with NPOs affecting social change through their core service-providing activities and influencing public policy deployment. For them, being able to make small changes to the life of their constituencies from within the system is proving a more successful approach than the more confrontational and governance rearrangement focus of Russia civil society agents in the past.

Funding

Funding was provided by British Academy (Grant Number SG111936).

Appendix

Appendix A: Overview of Participating Organisations

See Table 1.

Table 1 Overview of participating organisations

Code |

Interviewee(s) |

Organisational Focus |

|---|---|---|

Organisations in Samara (Region 1) |

||

Organisation1.1: Interview 1a Interview 1b |

Director/Founder |

Disability |

Organisation 1.2: Interview 2a Interview 2b |

Managing Director |

At-Risk Children |

Organisation 1.3: Interview 3a Interview 3b |

Managing Director |

Palliative care - Cancer |

Organisation 1.4: Interview 4a Interview 4b |

Director/Founder |

Childhood Cancer |

Organisation 1.5: Interview 5a Interview 5b |

Director/Founder |

HIV/AIDS prevention |

Organisations in Perm (Region 2) |

||

Organisation 2.1: Interview 1a Interview 1b |

Managing Director |

Action on Drug Addiction |

Organisation 2.2: Interview 2a |

Managing Director |

Childhood Cancer |

Organisation 2.3: Interview 3a Interview 3b |

Director/Founder |

At-Risk Children |

Organisation 2.4: Interview 4a Interview 4b Interview 4c Interview 4d |

Managing Director Deputy Director/Founder |

At-Risk Children including homeless |

Organisation 2.5: Interview 5a Interview 5b |

Director/Founder Chief Operating Officer |

HIV/AIDS prevention |

Organisation 2.6: Interview 6a |

Director/Founder |

Palliative Care - Cancer |

Organisation 2.7: Interview 7a Interview 7b |

Managing Director |

Disability |