One of the deadliest natural disasters in the United States occurred on a barrier island in 1900 when a hurricane struck Galveston Island, Texas. At least 6 000 of the island’s 44 000 inhabitants were killed (Bixel and Turner, Reference Bixel and Turner2000). This tragic event prompted the initiation of a landmark coastal engineering project in the United States: the construction of the Galveston Seawall and the subsequent raise of the island elevation through artificial fill (Wiegel, Reference Wiegel1991; Wiegel and Saville, Reference Westfall1996). The tidal inlet separating Galveston Island and the barrier island (Bolivar Peninsula) to the east serves as the entrance to one of the nation’s largest seaports, the Port of Houston. Balancing navigation safety of the inlet channel and healthy sandy beaches along the barrier islands has posed a major challenge to coastal management in the past that continues in the future. Fortifying the island and raising the elevation may not be the choice of solution for today. Adaptation based on comprehensive scientific understanding and increasingly accurate predictions is becoming the modern and likely future approach. Multifaced adaptation can be much more complicated than structural fortification, involving the entire coastal community and multi-disciplinary knowledge in addition to dominantly hard engineering.

Sandy beaches and tidal inlets are arguably among the most economically valuable coastal resources and draw broad interest from a wide spectrum of society. Sandy beaches attract numerous tourists and are often desirable residential areas. Tidal inlets often serve as navigational channels for both recreational and commercial vessels. They also connect estuaries with the ocean and play a significant role in water exchange and are therefore essential to environmental quality. For barrier island coasts, which broadly distribute worldwide, sandy beaches and tidal inlets are parts of one coastal system and should be understood and managed as such.

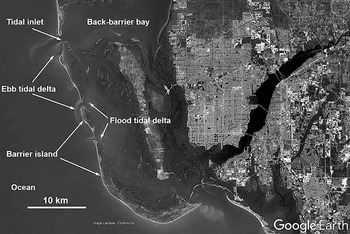

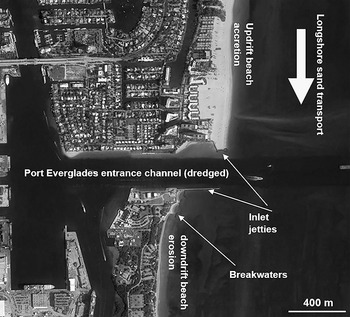

A general definition of a barrier island is given by Davis (Reference Davis1994a, Reference Davis and Davis1994b) as “an elongate, essentially shore parallel, island composed dominantly of unconsolidated sediment, which protects the adjacent land mass and is separated from it by some combination of wetland environments.” Presently, barrier islands can be found across all latitudes on all continents except the ice-covered Antarctica. Figure 1.1 illustrates the various sub-environments that constitute barrier–inlet systems. In general, the system is composed of barrier islands that are separated alongshore by tidal inlets. Sandy beaches typically distribute along the ocean side of the barrier island, backed landward by dunes and interior wetlands. Estuaries, as referred to as back-barrier bay or lagoon in this and other texts, occur landward of the barrier islands. Tidal inlets connect the back-barrier bay to the open ocean. Two morphological features typically develop in the vicinity of a tidal inlet, an ebb tidal delta on the ocean side, and a flood tidal delta on the landward side. The physical interaction between these environments is complicated and can be further exacerbated by human development and intervention, as illustrated in Figure 1.2. Except for the very narrow strip of sandy beach, practically every square meter of the entire barrier–inlet system is modified by human development in such a way that the natural processes and geomorphology are fundamentally changed.

From an energetics point of view, it can be argued that sandy beaches and tidal inlets occurring at the boundary between land and sea are among the most dynamic environments on the surface of the earth. They are influenced by regular waves and tidal forcing as well as extremely energetic conditions induced by storms. This very large range of energy, in addition to the rather random nature of storms, makes it very challenging to predict any morphology change of barrier islands. This, combined with human’s desire to live on barrier islands, creates a daunting task to manage these precious natural resources.

On a global scale, plate tectonics has a significant control on the distribution of barrier islands (Glaeser, Reference Gladki1978). Applying the then newly established plate tectonic theory, Inman and Nordstrom (Reference Inman, Elwany and Jekins1971) proposed a global scale coast classification. Based on the position relative to the moving plates, Inman and Nordstrom (Reference Inman, Elwany and Jekins1971) identified three types of coast: (1) collision coasts, those that distribute along the collision edge of the continents and island arcs, for example, the US Pacific coast; (2) trailing-edge coasts, those along the trailing-edge or noncollision side of a continent, for example, the US Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts; and (3) marginal sea coasts along the landward side of the island arcs, for example, the Pacific coast along the Eurasia side.

Glaeser (Reference Gladki1978) studied the global distribution of barrier islands based on Inman and Nordstrom’s (Reference Inman, Elwany and Jekins1971) coast classification and found that 49% of the barrier islands occur along the trailing-edge coast, 24% along the collision coast, and 27% along the marginal-sea coast. Glaeser (Reference Gladki1978) suggested that the developments of barrier islands are controlled by three factors: a wide continental shelf with gentle gradient, an abundant sediment supply, and a broad low gradient coastal plain.

Pilkey and Fraser (Reference Pilkey and Fraser2003) identified nearly 2 100 barrier islands along all continents except Antarctica, constituting about 12% of all the world’s open ocean coast. The Northern Hemisphere hosts 73% of the world’s barrier islands, partly attributable to the much larger land area as compared to the Southern Hemisphere. Quite relevant to the topic of this book, the United States has nearly 20% (405) of the world’s barrier islands, extending almost 5 000 km (Pilkey and Fraser, Reference Pilkey and Fraser2003) along large sections of the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coasts.

Barrier islands, practically narrow strips of sand in the sea, have the distinction of being among the most vulnerable and most desirable sites for human habitation, particularly for the case of the United States. Barrier islands are highly mobile, driven by the very dynamic interactions between the sea, with energetic storms, and the land, that is largely made of unconsolidated sand. However, the beauty and serenity offered by the sandy beaches, in addition to the navigation convenience provided by the inlets, have drawn human development despite the high risks of flooding by the sea and instability of the moving land, as shown in Figure 1.2.

In a recent US NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) State of Coast Report, the US coastal population trends from 1970 to 2020 was analyzed (NOAA, 2013). To more directly serve coastal management efforts, the population analysis was conducted in terms of US counties. Two types of coastal counties are classified. Coastal Watershed Counties are those where a substantial portion of their land intersects coastal watershed. The land use change and water quality impacts in these areas would directly impact the coastal ecosystem. Therefore, the residence in these counties could be considered as “the US population that most directly affects the coast” (NOAA, 2013). To provide a more direct context for coastal community resilience, the NOAA (2103) report classified US Coastal Shoreline Counties for the first time. The Coastal Shoreline Counties are those directly adjacent to the open ocean, major estuaries, and the Great Lakes. These counties bear the most direct impacts of coastal hazards, and therefore their residents are referred to as “the US population most directly affected by the coast.” Many of the Coastal Shoreline Counties along the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean have barrier islands. Despite the highly publicized coastal hazard brought by extreme storms over the past 120 years, highlighted by, for example, the storm in 1900 that killed an estimated 6 000 to 12 000 people in Galveston Texas, Hurricane Camille in 1969 that killed 259 people, and the more recent Hurricane Katrina in 2005 that killed between 1 245 and 1 836 people, the population in Coastal Shoreline Counties remains very dense and continues to grow rapidly.

The 2010 US Census indicates that 39% of the US population, or 123.3 million people, live in Coastal Shoreline Counties, which comprise less than 10% of the US land area (NOAA, 2013). This results in a population density that is 4.2-times the national average. The State of Florida is very well known for its frequent hurricane strikes. However, the population in the vulnerable low-lying Coastal Shoreline Counties increased 165% from 1970 to 2010, with a projected further 16% increase between 2010 and 2020 over a large base of nearly 15 million people. It is worth noting that a substantial portion of the Florida coast is lined with barrier islands.

Globally, population growth in coastal areas demonstrates a similarly increasing trend to that in the United States but with a much higher population density in many countries. Neumann et al. (Reference Neumann, Vafeidis, Zimmermann and Nicholls2015) provided a global assessment of future coastal population growth till 2060 in low-elevation coastal zones, as well as within the 100-year flood plains. Similar to the case in the United States, despite the projected, and sometimes well documented and publicized, risks associated with storm impact and sea-level rise, the population is growing at an alarming rate over an already very high population density with no signs of slowing down, let alone reversing course, till at least 2060. Therefore, improved understanding of coastal dynamics and better management of coastal resiliency will be crucial to the survival of the coastal human–natural environment.

Compared to most other coastal systems, barrier islands with their sandy beaches and tidal inlets are particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise and storm impacts simply because they are surrounded by the sea (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). Most of the modern barrier islands are younger than 4 000 years and were formed when the Holocene sea-level rise slowed down substantially from roughly 1 cm/yr to around 1–2 mm/yr (Davis, Reference Davis1994a, Reference Davis and Davis1994b; Davis and FitzGerald, Reference Davis and FitzGerald2004). It is broadly agreed that the formation of barrier islands requires a slow rate of sea-level rise, generally less than 3 mm/yr, as over the past 4 000 years, with the exception of spit type barrier islands, as discussed in Chapter 2. This slow sea-level rise requirement for barrier island formation and maintenance poses a challenging scientific question regarding the future survival and/or existence of this landform under the projected accelerating sea-level rise. Moore and Murray (Reference Moore and Murray2018) compiled a series of insightful papers examining the morphodynamics of natural barrier islands in response to climate change, specifically accelerating sea-level rise and storm impacts.

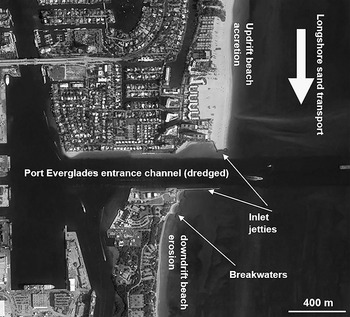

Due to intense human interest in sandy beaches and tidal inlets, many barrier islands have been developed (Figure 1.2). From a human engineering point of view, efforts to maintain a wide beach and a stable deep navigable inlet are often conflicting. This is illustrated in Figure 1.3 as an almost extreme case. The dredged Port Everglades entrance channel, serving mega cruise ships among other vessels, and the associated long inlet jetties have completely blocked the southward longshore sand transport to reach the downdrift side of the inlet. This results in substantial beach accretion at the updrift side due to impoundment by the inlet jetty and corresponding erosion at the downdrift side due to depletion of sand supply. This situation occurs at many developed barrier–inlet systems, as shown by the Florida example (Figure 1.3) and the Venice example (Figure 1.2); and constitutes a major coastal management issue.

Figure 1.3 Blocking of longshore moving sand by the deeply dredged Port Everglades (USA) entrance channel and the associated jetties, resulted in substantial updrift beach accretion and corresponding downdrift erosion, as illustrated by the nearly 400 m offset between the north and south sides of the inlet.

To emphasize a systems approach, Beck and Wang (Reference Beck and Wang2019) defined barrier–inlet systems as the interconnected chain of barrier islands, dissected by tidal inlets, through and across which sediment is exchanged in the littoral zone of the open coast and the estuary. Dean (Reference Dean1988) concluded that about 85% of the beach erosion problems along the Florida Atlantic coast can be directly related to tidal inlets. Therefore, allowing an adequate amount of sand to be transported across natural as well as structured tidal inlets constitutes a major beach–inlet management strategy in the State of Florida.

Beach nourishments constitute the major method for modern sandy shore protection. Finding beach compatible sand has become an increasingly challenging task. The often large sand body in the vicinity of a tidal inlet, particularly the ebb tidal delta (Figure 1.1), is a valuable sand source for beach nourishment. As a matter of fact, a large portion of the sand deposited on the tidal deltas has originated from the beach. Effectively managing the sand resources and minimizing potential negative impacts of the sand mining have evolved into a new regional sediment management strategy, an exciting new area of research and practice.

The hydrodynamics, sediment transport, and morphodynamics at the beach–inlet systems are complicated and provide intriguing research challenges at multiple temporal and spatial scales. Significant scientific advancements, particularly from an interactive system approach assisted by fast improving numerical modeling capabilities, have occurred in the past two decades, resulting in insightful new findings and development of new tools and management strategies. In this book, we focus on beach–inlet interactions in terms of sediment exchange and subsequent morphology response and its application in coastal sediment management. This book is intended for advanced students in geology, coastal engineering and management, environmental science, and oceanography. It is also a valuable resource for practicing engineers, environmental scientists, and coastal managers. Coastal residents who are interested in and concerned about the coasts may also find this book useful.

This book is organized as follows. Chapter 2 provides a review of various beach–inlet systems under different geological and oceanographic settings. Chapter 3 discusses hydrodynamic and sediment processes that shape beach–inlet systems. Hydrodynamic review includes fundamentals of wave forcing, tide forcing, and interaction between wave and tide as they function in beach–inlet systems. Key mechanisms of nearshore sediment transport are also reviewed. Commonly used formulas for calculating the sediment transport rate by breaking and non-breaking waves as well as tidal currents are provided. Chapter 4 describes the various morphologic features and their morphodynamics within a typical barrier–inlet system, along with the sediment characteristics associated with each feature. Chapter 5 examines the interactions between beaches and inlets with a special focus on inlet stability and sediment bypassing across a tidal inlet. Chapter 6 reviews various methods to mitigate beach erosion and to ensure inlet navigation safety within the framework of beach–inlet interaction. Chapter 7 discusses regional sediment management in beach–inlet systems, focusing on developing and balancing sediment budget at various temporal and spatial scales. Finally, Chapter 8 evaluates the resiliency of beach–inlet systems facing sea-level rise, storm impacts, and human stresses.