Introduction

The main political event in Norway in 2017 was the parliamentary (Storting) election in September. The centre‐right parties retained their majority in Parliament. The governing coalition of the Conservative (H) and the Progress (FrP) parties could therefore continue after the election. The election was a defeat for the Labour Party (Ap), whose share of the vote declined since the 2013 election.

Election report

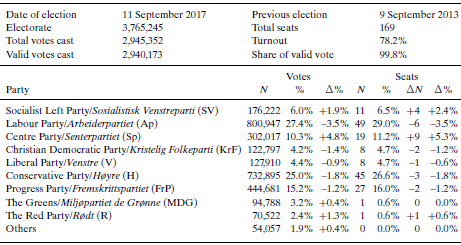

The Storting election of 11 September 2017 gave the two governing parties and their supporting centre‐right parties a parliamentary majority. Prime Minister Solberg's premiership therefore continued after the election. Nevertheless, the election result weakened the parliamentary base of the government. In the previous Parliament, the government could secure a majority with just one of the two centrist parties; the Liberal Party (V) or the Christian Democratic Party (KrF), whereas after the 2017 election the government needed the support of both parties.

The four parties supporting the incumbent government (Conservatives, Progress, Liberals and KrF) lost 5.1 percentage points and eight seats. Their parliamentary majority was reduced from 96 to 88 of 169 seats. The Liberals and the KrF barely passed the threshold of 4 per cent for the adjustment seats. In practice, this means that a 0.6 per cent lower share of the votes for those two parties would not only have cost nine seats but also would have meant the end of the conservative government.

The Centre Party (Sp), which gained 4.8 percentage points and went from 10 to 19 representatives, was one of the big winners of the election. The Socialist Left (SV) and The Red (R) parties also fared well, with increases of 1.9 and 1.3 percentage points respectively. The Reds gained representation (one seat) for the first time since 1993. In sum, these three opposition parties on the centre‐left gained 8 percentage points and 14 seats. A ‘normal’ result for largest opposition party, Labour, would have given the opposition parties a clear majority. However, Labour lost 3.4 percentage points and six seats. With only 27.4 per cent of the votes, it was the party's second worst election result since 1924. Turnout in the parliamentary election was 78.2 per cent – precisely the same as in the previous election (2013).

Though the sitting government was often criticized in the four years since its inception in 2013, it generally received a passing grade from voters according to the opinion polls. The main challenges for this government in those four years were probably, first, the falling oil prices in 2015, which led to a moderate rise in unemployment in the south‐west of the country where much of the oil sector is located; second, the refugee crisis in the fall of 2015 presented the government with the challenge of starkly rising numbers of asylum‐seekers and finally, the annual process of passing a budget in Parliament became a bit of a crisis in every instance. The compromises that had to be made, and the semi‐public negotiations between the centrist parties (Liberals and KrF) and the two governing parties (Conservatives and Progress Party) strained relations within this coalition, and sometimes cast doubt on whether it would survive until the next election (in 2017).

However, the government did survive, unemployment gradually fell and the refugee crisis passed into history. In the lead up to the 2017 election campaign, therefore, the sitting government was reasonably popular and did not struggle with any crises of major proportions.

In the lead up to the 2017 election campaign, the polls were close between the two governing parties and the two supporting parties (centre‐right) and the opposition centre‐left, but with a slight edge to the centre‐left. The most likely scenario was a Labour‐led government, with the support of other centre‐left parties, including the resurgent Sp (Aardal & Bergh Reference Aardal and Bergh2018).

Election campaigns in Norway (the short campaign) got started after the summer break in mid‐August, about a month before election day. Election campaigns, and national campaigns in particular, receive massive media attention, and party leaders participate in televised debates almost daily. While one or two main issues used to dominate campaigns in Norway, the issue agendas during the three last elections have been more diverse, including a number of issues. However, the horse race, and discussions about government formations, arguably dominated the media agenda.

Labour tried to make employment policy and economic policy central issues in the campaign. Although quite a few voters consider these issues to be important, Labour's strategy of focusing on economic issues was not entirely successful, in part because there was no sense of economic crisis in Norway. Also, Labour suffered a dramatic decline in the public opinion polls early in the campaign. This became an issue in itself, and throughout the campaign Labour politicians were faced with questions about why the party was declining in the polls.

Another dominant media narrative was the Progress Party and immigration policy. The Minister of Immigration and Integration, Sylvi Listhaug from the Progress Party, paid a high‐profile visit to Rinkeby in Stockholm, Sweden, in the middle of the campaign. Rinkeby has a large immigrant population, some social problems such as crime and high unemployment, and is sometimes used by people who favour stricter immigration policies as a symbol of a liberal immigration policy gone wrong. The Listhaug visit received large‐scale media coverage in both Sweden and Norway, and it stirred up a debate about immigration and integration policy, which then became a key issue in the campaign. The Sp represents rural interests in Norway and the party benefited from a popular opposition to several reforms initiated by the government. This included a reform of municipal and regional amalgamation.

Cabinet report

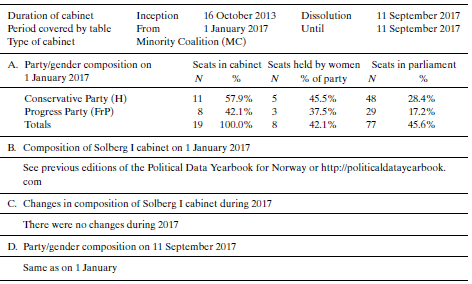

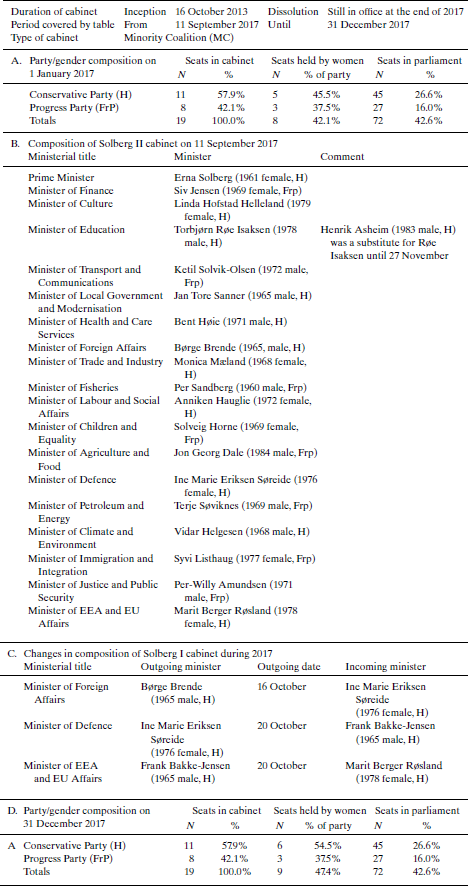

The coalition minority government of the Progress and Conservative parties, headed by Prime Minister Solberg of the Conservatives, was formed after the 2013 election. Since the government was re‐elected in 2017, Solberg continued to govern after the election. The only change in the composition of the cabinet in 2017 was set off when Foreign Minister Børge Brende resigned his ministerial post to take on the position of President of the World Economic Forum (WEF). Additional changes were made in January 2018 when the Liberals joined the governing coalition.

Parliament report

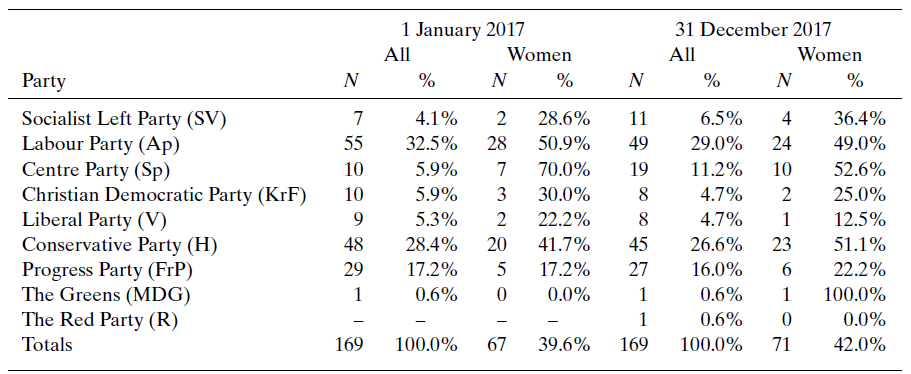

The election in September led to a slight uptick in the share of female representatives in Parliament. The balance of power remained on the centre‐right side of politics. One additional party was elected to Parliament: the Marxist Red Party. In total, nine parties are represented in the current Parliament, which is a record high.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of Parliament (Stortinget) in Norway in 2017

Source: Stortinget (n.d. b).

Issues in national politics

In the months after the election, the media started to report that the Liberals were considering joining the government. Their poor showing in the election, combined with the fact that an even worse result was averted by a number of previous Høyre voters supporting the Liberals, led some to argue that a change had to be made. A number of voters who supported them (notably those previous Høyre voters) probably did so to retain the centre‐right majority in Parliament, and thereby to re‐elect the sitting government. This fact gave some legitimacy to the idea that the Liberals should join the coalition. Others argued against this course of action, mainly because the Liberals would then become closely associated with the Progress Party, but also because the Solberg government would still not have a majority in Parliament, even with the inclusion of the Liberals. Despite these objections, the leadership of the Liberals entered into negotiations with the sitting government on 9 December, and ended up joining that government in January 2018.

Among other issues being discussed by Norwegian politicians in 2017 is the fate of the small number of wolves in the country. Should the population of wolves be reduced or allowed to grow? It is an issue that pits conservationists against people in rural areas where wolves may threaten livestock and create a sense of fear. The issue is hotly debated on the national stage, in part because it is important to the people concerned, but also because the wolf issue becomes a symbol of a more general split between rural and urban areas in Norway.

Another issue that within a short period of time came to dominate public discourse in Norway, as well as in many other parts of the world, is sexual harassment. In the wake of the #metoo campaign in November, Norwegian media started reporting on sexual harassment in several different industries. The #metoo campaign became a hot political issue when the deputy leader of Labour, Trond Giske, had several allegations directed at him. He publicly apologized for his behaviour on national television in late December. Giske resigned his post as deputy leader of the party in early 2018. A number of stories about other politicians have also come out since that time.