Prologue

Nearly everyone on earth knows the Cinderella story – the mistreated orphan, tormented by her stepmother, who, with a fairy’s help, wins a prince’s heart after he tracks her down with a glass slipper she left behind.Footnote 1 But few realize that this timeless tale, so familiar today, already existed in Greek, underwent a major transformation in India, and then journeyed to Southeast Asia, China, before circling back to Europe ages ago. Wherever the story went, it adapted, reshaping itself once again. What exactly has been enabling this quaint tale to thrive since ancient times, traversing unstoppably from one culture to another, captivating hearts worldwide? Is it because the story’s unusual power of psychological suggestion has universal appeal? Or does the answer lie in the relays of the story’s history of migrations?

Like the Cinderella story, the timeless stories (and the words that make them) told in this Element have been migrating across cultures for centuries, even millennia. They, too, have journeyed far and wide: from Greece and India to Southeast Asia, Inner Asia, China, Europe, and beyond. What has enabled these stories to stand the test of time and distance, securing their eternal presence in human history? Is their resilience rooted in religious faith, the pursuit of wealth through long-distance trade, the desire to tell and to hear enchanting stories, or the thirst for new knowledge? These are but a few of the possibilities. Although the focus of this Element is premodern Chinese literature and language, or literature written in Chinese characters and produced in regions that are parts of China today, we aim to contextualize premodern Chinese literature and language within premodern transregional and transcultural networks that we call “early globalism.”

But what is “early globalism”? How does “globalism” differ from “globalization,” a term that we encounter far more often than “globalism” nowadays? In the premodern world when a real sense of globalization had not yet occurred, smaller-scale transregional connections were already taking place and persisted. What do we call them? Geraldine Heng suggests that we refer to these smaller-scale transregional activities as “globalism,” differentiating them from the more modern phenomenon of “globalization.” Heng proposes that the study of globalism not only “foregrounds interconnectivity” across distances, enabling us to see “how geographical spaces and vectors were interlinked,” but also “exists as a dynamic” that forms “larger scales of relation” or “forces that globalize” (Heng, Reference Heng2021: 16). “Interconnectivity” includes the long-distance transport of anything such as goods, artisans, and stories over continents or seas; “dynamics” indicate cultural, religious, or political forces such as Islam and Indic culture that transformed local populations, politics, cultures, languages, architecture, and art (Heng, Reference Heng2021: 16). Further, such premodern globalism is patently uneven all over the world (Heng, Reference Heng2021: 17–18).

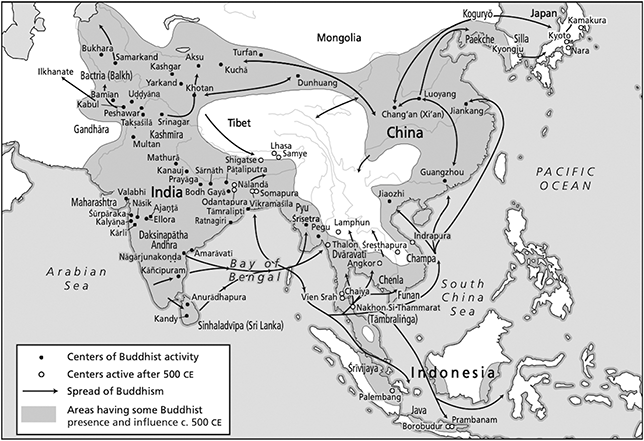

This Element focuses on literary diffusion to discuss two types of prominent cultural activities of early globalism in premodern China, activities that evince both interconnectivity and dynamics. First is early medieval and Tang (618–907) Buddhism’s influence on Chinese language and literature. The second is the growth of maritime trade and maritime interactions from the Tang dynasty onward that resulted in expansion and circulation of new knowledge. Both examples of early globalism brought forth literary diffusion.

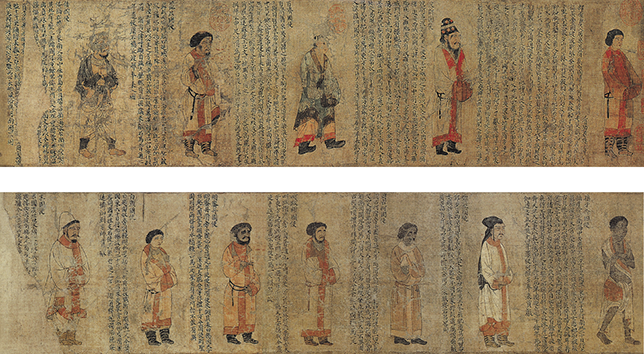

In premodern times, stories and knowledge were circulated and disseminated in a piecemeal fashion. Stories (and in most cases, fragments of stories) were heard, retold, memorized, paraphrased, summarized, improvised, adapted, written down, commented upon, illustrated, and passed on. This dynamic process of literary diffusion proved remarkably fluid, capable of sustaining itself across centuries with no end. The routes of literary diffusion overlapped with the trade routes by land and by sea that connected civilizations. Along the routes traveled new stories, foreign words, and novel knowledge carried by merchants and monks across deserts and oceans to reach bustling oasis towns and thriving seaports in other places, and then onward to other mountains and rivers, to other shores and other lands throughout the world.

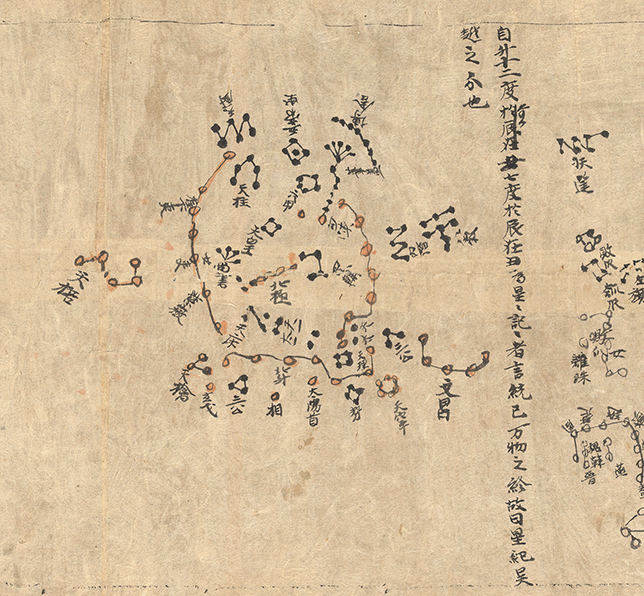

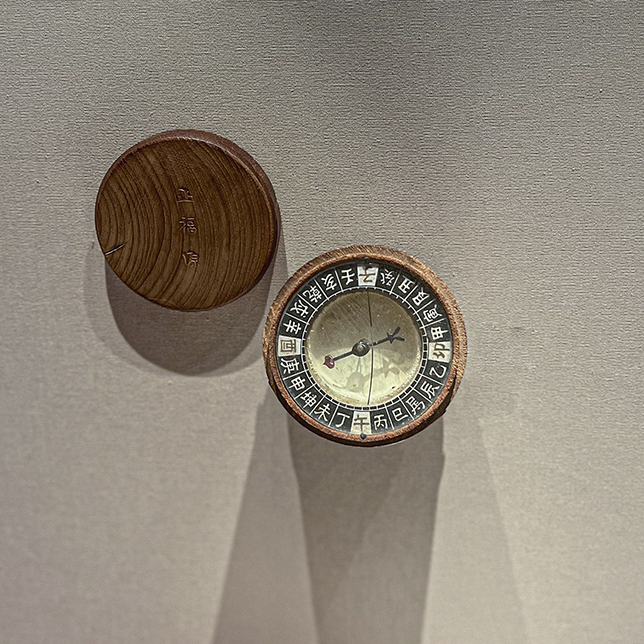

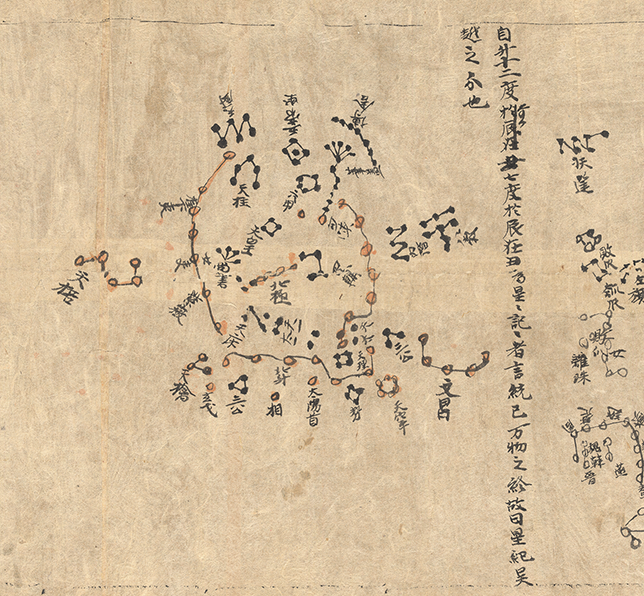

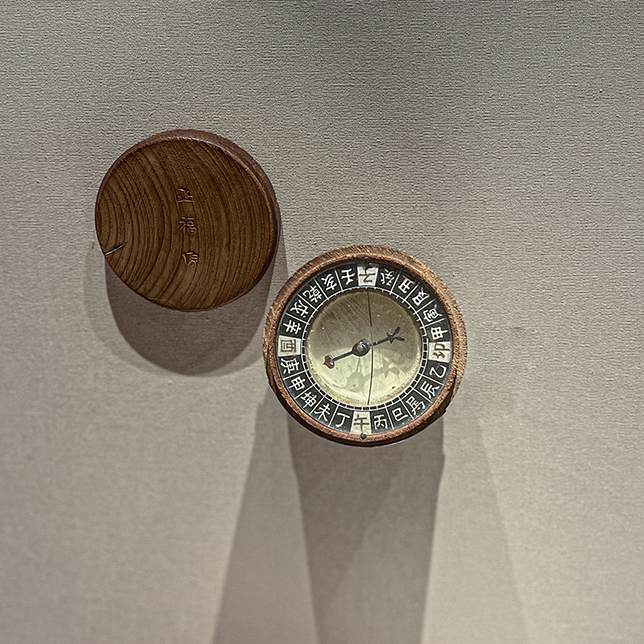

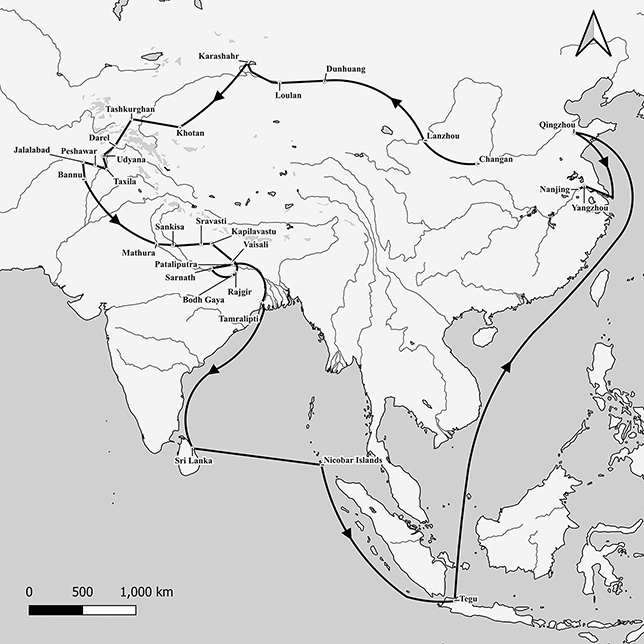

In this telling or, more precisely, retelling, of these medieval “global stories,” which is itself a form of literary diffusion, particularly as related to China, both Dunhuang and the South China Sea are two crucial geographical locales that constituted the medieval global loop of trade, religions, and literatures. The desert town of Dunhuang at the far western end of Gansu Province was the jumping-off point from which the fabled Silk Road led traders and monks across the chain of oases to travel from China to Central Asia and beyond and vice versa (Hansen, Reference Hansen2012: 167–172) (Figure 1). It was also an essential place for Buddhist pilgrims like Xuanzang 玄奘 (602–664) to pass through on their way to India to fetch Buddhist scriptures. As such, Dunhuang became a center of Buddhist culture, even though it was in a remote location. Further, with advances in maritime technology, especially shipbuilding and the invention of the maritime compass, from the Tang dynasty onward the South China Sea became increasingly important for maritime connections between China and the world (Figure 2).

Figure 1 The thirteenth star chart of the Dunhuang Star Atlas (thirteen charts in total), the oldest complete star map in existence, dating from the second half of the seventh century CE. The chart details the part of the sky that is aligned with the North Pole. It contains 144 stars visible to the naked eye.

Figure 2 A traditional Chinese maritime compass (a twentieth-century duplicate, Hong Kong Maritime Museum).

The desert and the ocean are connected and formed an early global loop. Some medieval travelers knew of this desert–sea circuit. For example, the Buddhist monk Faxian 法顯 (337–422) traversed overland from Chang’an through Khotan to reach India. On his trip returning to China, he took the sea route. He sailed to Sri Lanka, south of Calcutta in West Bengal, passed by Sumatra, and then headed to Shandong Peninsula (Hansen, Reference Hansen2012: 160–165). The desert–sea global loop will be the backdrop of China’s early global stories (see Figure A1 in the Appendix and the online resources).

Before beginning to tell these stories, three concepts need to be clarified. First, the duration of China’s Middle Ages is different from that of Europe. The European Middle Ages spanned from the fifth to the fifteenth century. But scholars of Chinese literature are now inclined to use “the Middle Period” to refer to the Tang (618–907), the Five Dynasties (907–797), and the Song (960–1276). They use “early medieval” to refer to the Six Dynasties (220–589) up to the Tang. China’s Middle Ages can be broadly defined as spanning from the Western Han dynasty (202 BCE–9 CE) to the Southern Song (1127–1279). Since there is not a single standard for “medieval/middle period” that fits both China and Europe, this Element also includes an “early modern” duration – the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) – to correspond approximately to the European Middle Ages and for the purpose of including two important examples of “literary diffusion” relating to the Ming literature on the monk Xuanzang’s journey to India and Admiral Zheng He’s 鄭和 (1371–1433) seven voyages (1405–1433) across the Indian Ocean.

Second, the term “Chinese literature” refers to various kinds of literature that were produced within the administrative borders of any given Chinese dynasty. In particular, this Element focuses on “Chinese popular literature and language” – works and words that belong neither to the Confucian canon nor to classical Chinese poetry. These are translated Buddhist sutras, lay Buddhist storytelling genres, tales, dramas, and novels. They contain a significant number of elements from foreign religions and cultures, exotic stories and knowledge, and colloquial expressions. There was a wide range among the members of the Chinese audience from royalty and elites, to merchants, laymen and laywomen, and, to some extent, common folk.

Third, the primary theme of this Element is literary diffusion. Whereas “globalism” signifies any transregional interconnectivity or dynamics, regardless of discipline or subject, “literary diffusion” concentrates on the interconnectivity and dynamics of languages and literatures across cultures. “Literary diffusion” refers to the process by which language and literature are transmitted beyond the culture in which they originated, or the process by which language and literature are created and circulated to accommodate the incoming Other. “Literary diffusion” presumes an unevenness and difference among various cultures and the existence of one or many cultural centers that generate fluxes of literary diffusion. In other words, globalism seems inevitable in a world of diversity and difference. In fact, globalism may have happened more dramatically in premodern times than we thought since the high level of unevenness of cultures in medieval times might have brought about a rapid “literary diffusion.” Buddhism is a great example. In its early days, Buddhism spread very quickly from India to China and other East Asian countries where the cultures were completely different. When Buddhism reached its peak in China in the Tang dynasty and then became pervasive throughout late imperial Chinese society, this cross-cultural transmission slowed down dramatically.

Diffusion is also operative in the physical sciences. In biochemistry, channel proteins and carrier proteins assist molecules in moving across the membrane (Philibert, Reference Philibert1991). Likewise, in the Middle Ages, the ship was the vehicle par excellence that expedited the spread of new information to large regions of the world. Good examples of seaborne “literary diffusion” are the cases of the global spread of the Cinderella story in the Middle Ages and the voyages of Zheng He that collected a large quantity of information about Southeast Asia and the Middle East from around the Indian Ocean, along with all sorts of exotic flora and fauna, and carried them back to China.

This Element consists of two parts. Part I discusses the spread of Buddhism in China and its legacy in Chinese language and literature. Part II examines how maritime circulations facilitated literary diffusion and production in China and around the world.

PART I Buddhism And Literature

Introduction to Part I

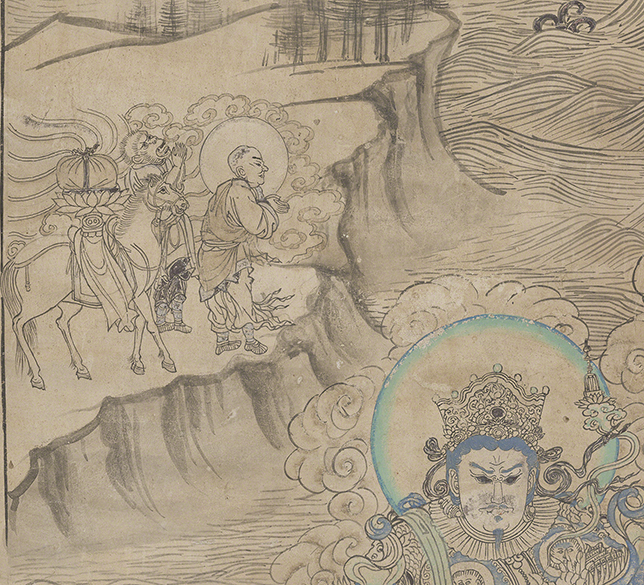

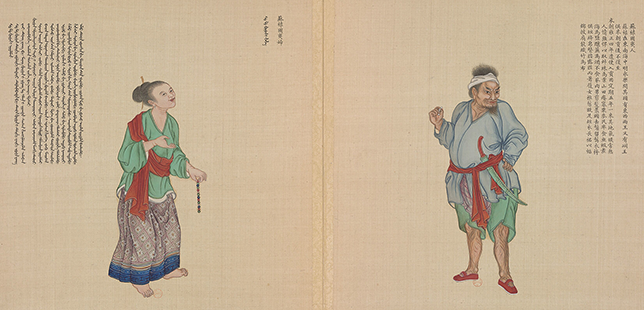

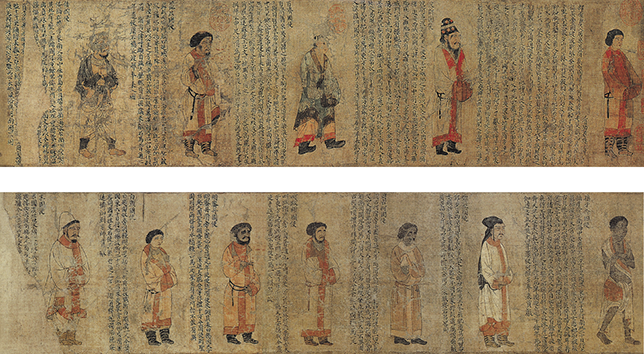

Approximately 2,000 years ago, merchants from Iran, Tocharia (northern rim of the Tarim Basin), and India traversed the vast deserts between the Western Regions and China on camel and horseback to trade precious goods for their communities. Through the scorching winds, under starry skies, along trails littered with bleached bones and animal dung, these travelers whispered prayers to the Buddha for safe passage (Figure 3). Spreading their faith, they shared tales about the Enlightened One along the fabled Silk Road. But these followers of the Buddha may never have anticipated – or they may have devoutly believed – that centuries later, the Buddha’s teachings would bear countless fruits in this foreign land.

Figure 3 Buddha with radiate halo and mandorla. A portable shrine from the Turfan area, fifth- or sixth-century CE, in the northern branch of the Central Asian Silk Road (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

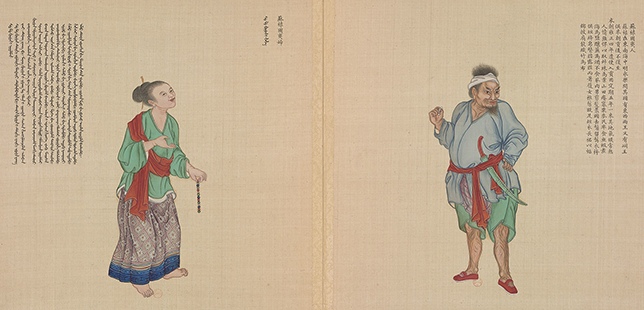

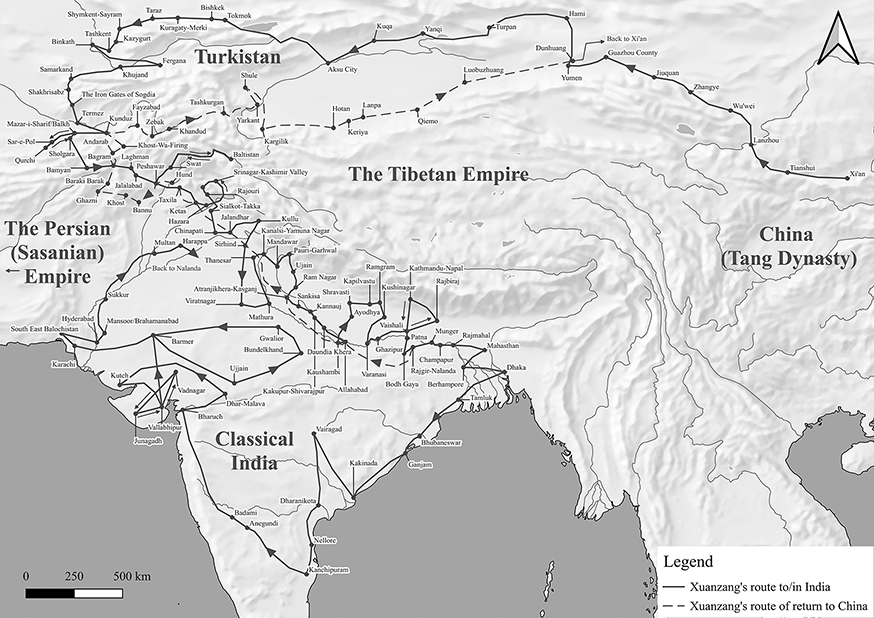

As Arthur F. Wright insightfully notes, Buddhism’s transformation of Chinese culture is “one of the great themes in the history of Eastern Asia” (Wright, Reference Wright1959: 3). With the founding of Buddhism, during the Maurya empire (322–185 BCE), the teaching of the Buddha spread over the Indian subcontinent, expanding northwestward into the regions of Gandhara, Kashmir, and eastern Afghanistan. Buddhism took hold in the thriving regions of present-day Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, and along the Amu Darya (Zurcher, Reference Zurcher, Idema and Zurcher1990, Reference Zurcher1997). Later, Iranian, Tocharian, and Indian peoples traveling along the Silk Road from northwestern India to the frontier of China’s Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) introduced Buddhism (see Figure A2 in the Appendix and the online resources).

The earliest Buddhist scriptures containing prescriptions to enhance intuitive faculties were well received by the Chinese, who were eager to acquire knowledge of longevity and immortality (de Bary and Bloom, Reference de Bary and Bloom1999: 421). In one of the earliest discourses on the compatibility of Buddhism and Chinese culture, Mouzi: Disposing of Error 牟子理惑論, Mouzi defends Buddhism by arguing that Chinese sages like Confucius, Laozi, Yao, Shun, and the Duke of Zhou would all have applauded the foreign religion’s virtues, regardless of its different cultural practices (de Bary and Bloom, Reference de Bary and Bloom1999: 421–426). This was the very promising beginning of Buddhist teaching in China.

Part I consists of three sections. Each section focuses on one aspect of Chinese language and literature that were greatly influenced by Buddhist literary diffusion. Section 1 discusses medieval Buddhist translation as a type of literary diffusion that generated new words and discourses in China that had long-lasting impact on Chinese language and culture. Section 2 delves into how Buddhist literary diffusion gave rise to new art forms and genres. The new genre of bianwen that grew out of lay Buddhist oral storytelling is a case in point. The bianwen genre has bequeathed much to the Chinese popular literary and performance tradition. Section 3 explores how Buddhist literary diffusion created the literary world of Chinese literature. It examines popular stories of the pilgrimage to India by the legendary monk Xuanzang as influenced by the Ramayana and Buddhism. The most famous realization of all these stories about Xuanzang and his companions is the Ming novel Journey to the West (Xiyou ji 西遊記) which has been translated into English four times in the twentieth century and adapted into cartoons, animation, dramas, and films around the world. These stories are excellent examples of how the medieval literary diffusion could prompt new currents of literary diffusion that could last for hundreds of years and will possibly continue ad infinitum.

1 Buddhist Translation and the Chinese Language

The Buddhist scriptures originally were disseminated in a variety of local Prakrit vernacular languages. Later, Buddhists adopted Sanskrit, a refined literary language, to produce Buddhist literature (Nattier, Reference Nattier1990).Footnote 2 But the Chinese language is fundamentally different from Sanskrit and Prakrit. So when the Buddhist monks arrived in Chinese-speaking regions, they were faced with huge linguistic barriers. In order to spread Buddhism in China, they decided to translate their scriptures into Chinese. Some of the earliest notable Buddhist translators came from Gandhara,Footnote 3 Sogdiana,Footnote 4 Tocharia (northern rim of the Tarim Basin), and the eastern borderland of Parthia (located today in Iran) (Boucher, Reference Boucher1998). These monks translated sutras in monastic centers such as Kucha in the Tarim Basin (located today in the Xinjiang region of China) and Dunhuang (Milward, Reference Milward2013: 28).

Generally speaking, translation was done through collaboration and oral transmission. Early medieval non-Chinese monks recruited teams of two to four people to translate a single text. The presiding translator, known for his erudition and firm memorization of sutras, would recite the Buddhist text orally. Depending on the presiding translator’s mastery of Chinese, he would either interpret the text in Chinese himself or let his bilingual assistants explain his words in Chinese. Then, the recorder would transcribe and edit what had been interpreted into written Chinese (Cheung and Lin, Reference Cheung and Lin2006: 8). For example, the Scripture of the Great Bright Enlightenment attributed to Zhi Qian 支謙 (fl. 222–252 CE) displays enormous diversity in vocabulary and style (Nattier, Reference Nattier2008 [2010]), suggesting the collaborative process of the translation.Footnote 5

A scripture can have several origin and translation versions. For instance, initially written in a dialect of the Magadha kingdom based in the eastern Ganges plain, the Lotus Sutra was gradually transmitted in Sanskrit and Central Asian languages northwestward into Central Asia, Nepal, the Western Region, and East Asia. The Lotus Sutra has had six to twelve Chinese translations. Each of the three existent Chinese translations of the Lotus Sutra is based on a different text, written on either palm leaves or white cotton cloth found in Khotan and Kashmir (Suwen, Reference Suwen 素聞.2007: 16). However, these original texts may not be in Sanskrit. They may be Iranian or Tocharian translations of Sanskrit versions (Ji, Reference Ji1947; Reference Ji1990; Zhu, Reference Zhu1992: 14).

In at least one case, a Chinese Buddhist sutra may not have had its original Sanskrit counterpart. We have the example of a Chinese Buddhist monk translating a Chinese sutra back into its supposedly original Sanskrit language. In this instance, the celebrated monk Xuanzang’s “translated version” of the Heart Sutra, which has become the standard version in East Asia, is in fact the “original” text, created by Xuanzang himself, who extracted it from the Perfection of Wisdom (Prajnaparamita) in 25,000 lines. From the Chinese Heart Sutra he back-translated the Sanskrit Heart Sutra (Nattier, Reference Nattier1992).

Additionally, it is noteworthy that most of what we know about translation in the early medieval period consists of only a handful of names of the Central Asian Buddhist translators as the presiding translators to whom we attribute the translated texts’ authorship. These include the Parthian prince An Shigao 安世高 (c. 200 BCE) and his countryman An Xuan (fl. 147 CE), the Indo-Scythian Zhi Qian, Lokaksema (Zhi Loujiachen) from the Kushan empire (fl. 147–189 CE), and Kumarajiva (c. 344–409 CE) of Indian (Kashmiri) and Tocharian parentage. These notable translators are only the tip of the iceberg of the translation community, most of whom must have already become anonymous between the Han (202 BCE–220 CE) and the Jin (266–420 CE) dynasties (Cheung and Lin, Reference Cheung and Lin2006).

Medieval Discourse on Translation

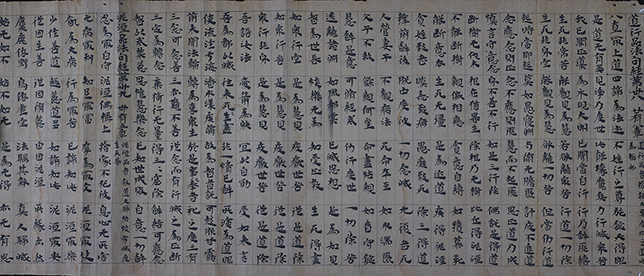

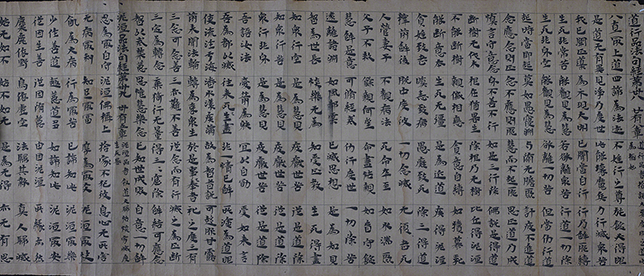

Buddhist translation prompted the first wave of discussions of methods and theories on what “a good translation” was in Chinese history. Zhi Qian became the first person in the history of Chinese translation to discuss translation theory. When translating and introducing Sanskrit terms, he proposed to “translate meaning” (huiyi 會意 or yiyi 意譯) rather than using the conventional method of “transcription” (yinyi 音譯). He suggested creating new words and phrases based upon the original Buddhist Sanskrit terms. He also advocated new ways of explaining religious jargon by adding explanatory comments to the original text. Such additions served to clarify the translated text. In the preface to the Scripture of Dhammapada (Figure 4), he introduced the idea of the importance of polishing the translated language and inserting interpretation into the original text to elaborate on its meaning:

The language of Tianzhu [India] has different sounds from that of the Han empire. Their writing is called the Tian script and their language is called the Tian language [Tian also means “from Heaven”]. Their way of designating objects differs [from ours] and it is difficult to bring their meanings across [when translating]. The only early translators capable of rendering Sanskrit into Chinese while preserving the form [of the original] were the Parthian prince An Shigao, a former officer named An Xuan, and [Yan] Fotiao. Hardly anyone was capable of continuing [this work]. Later transmitters were unable to adhere so strictly [to the correct mode of the originals]; for the most part they treasured what was precious [in the Buddha’s message] and expressed its main points roughly … Laozi said, “Beautiful words are not trustworthy, trustworthy words are not beautiful.” Confucius stated, “Writing does not completely express speech, and speech does not completely express meanings.” This shows that there was no limit to the profundity of the sages.

In this case, when communicating the Sanskrit meaning, we must do so directly and clearly. For this reason, these chants were collected and translated from the [foreign] reciters themselves. In compiling a standard text, the principle was not to add any literary adornment. When translating, if there was a passage that could not be understood, it was left out and not transmitted. There are accordingly many gaps and untranslated sections [in the Dhammapada]. Nonetheless, these translations, plain in wording and profound in ideas, concise in style yet broad in reference, link together the entirety of the sutras. Each section has a standard text and each sentence has its annotation. If those in India who began the study of the dharma did not study the Dhammapada, they were called “wanderers.” The Dhammapada gives an auspicious entry to the beginner; it is a mysterious treasure for advanced students. It can open minds, remove doubts, persuade people, and confirm one’s vocation. Studying it does not require great effort, but its fruit is vast. Should it not be called wonderful and valuable?Footnote 6

This passage presents the first recorded discussion of translation as a disciplined practice in Chinese history.Footnote 7 Zhi Qian emphasizes the clarity of translation as paramount: An effective translation must convey meaning clearly through plain and accessible language. This approach posits the ideal translator as an eloquent communicator in the target language and a perceptive interpreter of the foreign culture. Zhi Qian advocates for the translator as an articulate mediator, ensuring Buddhist teachings could be faithfully transmitted to the Chinese audience.

Figure 4 A segment of the manuscript Dhammapada, Eastern Jin dynasty, 317–420 CE (Gansu Museum, No. 001).

Looking back at early Buddhist translation as a cross-cultural activity, some modern scholars argue that it triggered early attempts at comparative thinking through the strict third-century practice of geyi 格義 (“categorizing concepts”). Rather than creating a new Chinese term to designate a Buddhist concept or transcribe a foreign Buddhist term into Chinese, the translator would adopt Daoist terms to designate approximately corresponding Buddhist concepts. For example, Dao (the Way) was adopted as a term for bodhi, and wuwei (nonaction) was the term designated for nirvana (Deeg, Reference Deeg2008 [2010]: 83–118).Footnote 8 This recourse to the cultural and linguistic familiar no doubt occurred from time to time, but there is no conclusive evidence that it had a formative effect on the development of the terminology and ideology of Buddhism during the period of its arrival in China. In actuality, it was never put into widespread use as a practical means of translation, since the medieval Chinese thinkers were able to reason independently in the new epistemological system (Mair, Reference Mair, Alan and Lo2010: 227–264; Mair, Reference Mair2012: 38).

The famous translator Kumarajiva’s version of the Lotus Sutra – one of the fundamental scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism – is a perfect example of how effective translation and independent storytelling and reasoning can be for the transmission of Buddhism to a wide range of readers. Throughout his translation, he barely uses jargon, transliteration, geyi, or annotation. The language of Kumarajiva’s translation is plain, clear, colloquial, fluent, and free of difficult classical Chinese phrases. He and his translation committee made sure that the translation itself was compelling enough to convey the concepts in Mahayana Buddhism correctly. Kumarajiva decided to retranslate the Lotus Sutra because he found that his predecessor Dharmaraksa’s 竺法護 (233–310) translation of the same sutra did not interpret some Buddhist concepts correctly and its language was too obscure for readers to grasp the gist of Buddhism. His translation was so successful that the monk Zhiyi 智顗 (538–597) used it as the main scripture of the Tiantai 天台 school of Chinese Buddhism of which Zhiyi was the founder (Suwen, Reference Suwen 素聞.2007: 14–15; Lopez, Reference Lopez2016: 47–50). The teaching of the Tiantai school later spread to Japan and Korea.

One of the most famous parables of the Lotus Sutra is the burning house parable. A crumbling house is on fire. The 500 people who are living in the house are still indulging in dallying inside the house, unaware that the house is burning and that their lives are in danger. Witnessing this, their loving father outside the house fears that his children will die in the fire and finds no useful means to save them. So, he devises carriages pulled by deer, horses, and oxen and promises to give everyone a carriage. This way, he successfully convinces his children to get out of the perilous house. The following is an excerpt of an English translation based upon the sutra translated by Kumarajiva.

Sariputra,Footnote 9 imagine that a country, or a city-state, or a municipality has a man of great power, advanced in years and of incalculable wealth, owning many fields and houses, as well as servants. His house is broad and great; it has only one doorway, but great multitudes of human beings, a hundred, or two hundred, or even five hundred, are dwelling in it. The halls are rotting, the walls crumbling, the pillars decayed at their base, the beams and ridgepoles precariously tipped. Throughout the house and all at the same time, quite suddenly a fire breaks out, burning down all the apartments. The great man’s sons, ten, or twenty, or thirty of them, are still in the house.

The great man, directly he sees this great fire breaking out from four directions, is alarmed and terrified. He then has this thought: “Though I was able to get out safely through this burning doorway, yet my sons within the burning house, attached as they are to their games, are unaware, ignorant, unperturbed, unafraid. The fire is coming to press in upon them, the pain will cut them to the quick. Yet at heart they are not horrified, nor have they any wish to leave.”

⋯

At that time, the great man has this thought: “This house is already aflame with a great fire. If we do not get out in time, the children and I shall certainly be burnt. I will now devise an expedient, whereby I shall enable the children to escape this disaster.” The father knows the children’s preconceptions, whereby each child has his preferences, his feelings being specifically attached to his several precious toys and unusual playthings.

Accordingly, [the father] proclaimed to them: “The things you so love to play with are rare and hard to get. If you do not get them, you are certain to regret it later. Things like these, a variety of goat-drawn carriages, deer-drawn carriages, and ox-drawn carriages are now outside the door for you to play with. Come out of this burning house quickly, all of you! I will give all of you what you desire.” The children hear what their father says. Since rare playthings are exactly what they desire, the heart of each is emboldened. Shoving one another in a mad race, altogether in a rush they leave the burning house.

Kumarajiva’s language is naturally fluent. He shows the clear meaning of a given passage rather than just providing a word-for-word translation (Lopez, Reference Lopez2016: 45). The burning house is a metaphor for the everyday desires that bring suffering to all sentient beings who are completely unaware of their misery and hence cannot transcend the mundane world. The loving father is the Buddha who, with the heart of compassion, wants to save the ordinary people from suffering. But he employs a strategy: to make “expedient devices” – the three carriages – to guide people his way. The three carriages represent the three vehicles of Buddhism expounded for the voice-hearers (Shravaka), for cause-awakened ones (pratyekabuddha), and for the bodhisattvas. At the end of the story, however, instead of giving them the three carriages promised, the father gives everyone a splendid carriage “made of the seven jewels,” pulled by a white ox, “whose skin is pure white, whose bodily form is lovely, whose muscular strength is great, whose tread is even and fleet like the wind.” The kids all happily ascend the splendid carriages to play, completely forgetting about the three other carriages promised to them (Hurvitz, Reference Hurvitz1976: 60). This carriage embodies Mahayana Buddhism, which can help sentient beings achieve enlightenment (Figure 5). Throughout the story, Kumarajiva barely uses transliteration, annotation, or geyi, except for some essential Sanskrit terms, such as boruoboluomi 般若波羅蜜 (Prajnaparamita), a significant concept in Mahayana Buddhism that teaches that all sentient beings possess the ability to reach enlightenment. In Kumarajiva’s captivating translation and storytelling, the parable itself is powerful enough to deliver the Mahayana Buddhist message. Kumarajiva’s translation has since been the most popular version up to today, widely read, annotated, and translated in East Asia and around the world.

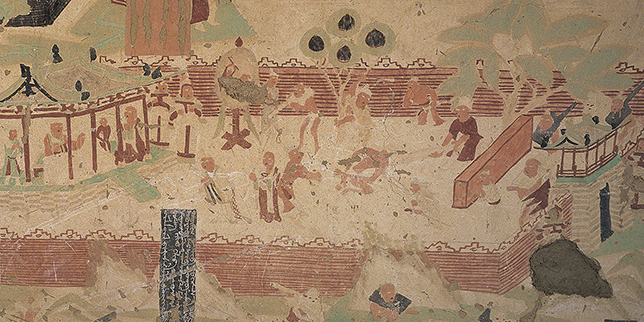

Figure 5 A mural on the burning house parable in the Lotus Sutra, Five Dynasties (Southern wall, Mogao Cave 98). In the lower-right register of the painting, a household compound burns, while figures within the compound remain engrossed in riding horses or indoor activities, unaware of the fire. Some people have already exited the house. Some scramble to board the three blue-canopied carriages pulled by white oxen–vehicles symbolizing Mahayana Buddhism.

In Buddhist translation, Sanskrit terms are still important. Xuanzang of the Tang dynasty reiterated that Sanskrit’s linguistic aspects should be taken into account:

[Sanskrit’s] words are gentle and fine. Its sounds are recurrent. It either expresses many meanings with one word, or one meaning is expressed by many words. Its sound has modulation, and its tones are divided into voiced and voiceless. Since Sanskrit is so profound, its translation depends on intelligent men. Since the essence of the sutras is deep and mysterious, understanding its correct meaning relies upon people of high virtue. If the translator and his team reduce this phonetic aspect in his writing, and if they adjust the Sanskrit tones to the tones in China, the translation is not going to be good, and the translated thesis is not going to be elegant.Footnote 10

Like Zhi Qian and Kumarajiva, Xuanzang similarly considered that the language of a good translation should be plain and clear. Yet he regarded it better, in some circumstances, to transcribe the Sanskrit sounds with Chinese characters. He laid out five guidelines for transcription: do not translate the esoteric Buddhist terms; do not translate the terms that have multiple meanings; do not translate the things and deities that cannot be found in China; keep the customary transcriptions; make worshippers respect the deities and Buddhist concepts signified by these transcriptions. These five guidelines have become frequently used in the discourse of traditional Chinese translation (Cheung and Lin, Reference Cheung and Lin2006: 134–135).

The Impact of Buddhist Translation on the Chinese Language

Early medieval Buddhist translations greatly influenced the lexicon, grammar, and syntax of the Chinese language. As the linguist Zhu Qingzhi 朱慶之 pointed out, the term “Buddhist hybrid Chinese” refers to the language used in the Chinese translations of Buddhist scriptures and Chinese compositions on Buddhism. Buddhist hybrid Chinese contains a large number of loanwords, translation words, disyllabic words, and colloquial phrases (Zhu, Reference Zhu2009: 13–15). Over the span of nearly 1,000 years, between the Eastern Han (25–220 CE) and the Southern Song dynasties (1127–1279 CE), approximately 1,482 scriptures known to us today were translated into Chinese. These scriptures generated 46,000,000 Chinese characters (Zhu, Reference Zhu2009: 7). The sheer volume of the numerous translation projects has expanded Chinese vocabulary by as many as 35,000 words.

Some examples of loanwords include fo 佛 (Buddha, “the awakened”), jie 劫 (kalpa, “a long period of time [eon] between the creation and re-creation of a world”), jie 偈 (gatha, “verses”), sanmei 三昧 (samadhi, “the highest state of mental concentration”), niepan 涅槃 or nihuan 泥洹 (nirvana, “the transcendence beyond suffering and the cycle of death and rebirth”). In terms of translated words, for instance, we find examples such as rulai 如來 (tathagata), falun 法輪 (Dharmacakra), mo 魔 (mara), cibei 慈悲 (“compassion”; karuna), jietuo 解脫 (“liberation”; moksha), yinyuan 因緣 (karma), shijie 世界 ( “universe”; lokadhatu), lunhui 輪迴 (“reincarnation”; samsara), and fanbai 梵呗 (“hymns”; Brahma-patha).

Aside from coining new terms and phrases, another method of translation and transcription is to borrow existing Chinese phrases and designate a new Buddhist meaning for them. For instance, yingxiang 影響 (“influence” in modern Chinese) originally meant “shadow and sound.” But later translators adopted the word to signify emptiness and karma in Buddhism (Zhu, Reference Zhu1992: 231–234). Another example is ayi 阿姨 which in Chinese means “aunt,” but in Buddhist translation it is used to designate the Sanskrit term upasika 優婆夷, a common title for women of high social status who believe in Buddhism and still live at home. Further, jiehui 節會 in Chinese indicates “a festival” or a “gathering of people to celebrate a festival.” But when used in Buddhist translation, it designates an Indian festival that takes place before New Year’s Day. Zuxingzi 族姓子 originally meant a son of a family clan in Chinese, but in Buddhist translation it is used to designate the Sanskrit term kulaputra, meaning a noble-born son (Zhu, Reference Zhu2010).

Further, Buddhist hybrid Chinese consists of a large number of disyllabic words, rapidly expanding the disyllabic and multisyllabic vocabulary of the Medieval Chinese language. One major reason is that the Buddhist scriptures are meant for memorization and oral recitation. Regular rhythm that facilitates easy memorization then leads to the creation of numerous disyllabic and multisyllabic words in Buddhist scriptures (Zhu, Reference Zhu1992: 124–129).

In terms of grammar, Buddhist translation also integrates Sanskrit grammar into certain Chinese phrases. An obvious example is rushi wowen 如是我聞 (Skt: Evam maya-srutam) which in English means “Thus have I heard.” The Chinese word order imitates the Sanskrit grammatical formula. If the translation were in Chinese word order, it would have been 我聞如是. Before the fifth century CE, the entire Chinese translation of the Indic Buddhist phrase was wen rushi 聞如是 without the first-person pronoun. The term rushi wowen 如是我聞 is a highly exceptional phrase that imitates Indic grammatical order and could have resulted from the different practices of diverse translation schools (Nattier, Reference Nattier and Sen2013).

The adoption of vernacular language rather than classical Chinese in Buddhist scripture translation may have been due to philosophical, religious, and realistic reasons. First, language is an upaya or convenient means for the zealous Buddhist monks to spread their faith so as to rescue all sentient beings from suffering in samsara. Ultimately, language is unimportant in Buddhism: The Suttanipata considers the Buddha beyond language. In the Theragatha, the Buddha cannot be sensed in language or sound (Gómez, Reference Gómez and Lancaster1977: 446a), and in Mahayana Buddhism, speech can obstruct the spread of the Way. Chan Buddhism further emphasizes the unimportance of language and abides by the rule of transmitting the dharma through the mind rather than through texts.

Second, significantly and in reality, since early Buddhist translators all came from South Asia and Central Asia, Chinese was not their mother tongue. They gradually learned colloquial Chinese through everyday experiences. As a result, when they interpreted the scriptures orally in front of the recorder, they naturally used many colloquial expressions which were then jotted down by the recorder and incorporated into the Chinese translation. This interesting oral–written translation process gave rise to the Chinese written vernacular language which was largely excluded in the discourses of Chinese classics, historiography, and classical poetry (Mair, Reference Mair1994a).

Concluding Remarks

Translation is a prime example of how literary diffusion takes place. Buddhist scripture translation brought into Chinese language a plethora of Sanskrit terms and Buddhist ideas through transliteration and translation. Such diffusion dramatically expanded Chinese vocabulary and left a mark on Chinese grammar and syntax; most significantly, it hastened the emergence of written vernacular Chinese. Its profound influence on the Chinese language has been long-lasting. Through lucid and effective translation, coordinated by visionary translators such as Zhi Qian, Kumarajiva, and Xuanzang, many Buddhist tales like the burning house allegory have inspired and influenced generations of Chinese monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen for centuries. These tales continued to transcend borders to spread to other countries and cultures. Buddhist scripture translation also sparked early discussion of methods and theories on what constituted a “good” translation. These early medieval dialogues herald the cross-cultural comparative thinking and translingual practice widely discussed in today’s global context.

2 Bianwen (“Transformation Texts”) and Their Importance

Besides Chinese language and cultural discourses, Buddhist literary diffusion created new genres of Chinese literature. Arguably one of the most important sources for understanding the development of Chinese literature, bianwen (“transformation texts”), a genre of lay Buddhist storytelling, is a case in point. However, nothing was known about bianwen (“transformation texts”) before the beginning of the twentieth century: For 1,000 years, from the early eleventh century to the end of the nineteenth century, the manuscripts on which they were written lay sealed inside a cave outside Dunhuang. The chief glories of Buddhist art (wall paintings and sculptures) at Dunhuang are to be found in the Mogao Caves, sixteen miles southeast of the town. The Mogao Caves are a complex of about 500 temples and shrines built into a cliff face of soft conglomerate. One of them, Cave 17, constitutes a small library that served as a repository for approximately 60,000 manuscripts that are now known as the Dunhuang manuscripts. The story of how, when, and why the manuscripts were deposited and sealed in Cave 17, who discovered them a millennium later, their contents, and the way they were distributed around the world is a separate and very complicated tale (Hao, Reference Hao2020). Two of the key figures in the exploration and early investigation of these Dunhuang manuscripts were the Hungarian-British archaeologist Marc Aurel Stein (1862–1943) and the French philologist Paul Pelliot (1878–1945). The manuscripts they retrieved from Cave 17 were taken back to England and France where they were accessioned in the British Library and Bibliothèque nationale, respectively, and ordered under the manuscript numbers preceded by “S” (Stein) and “P” (Pelliot).

The vast majority of the Dunhuang manuscripts are sutras and other Buddhist religious texts, but there are also Confucian and Daoist works, classics, histories, medical and mathematical treatises, contracts and other legal documents, dictionaries, music scores, geographical and astronomical maps and discourses, plus records and accounts dealing with virtually all other realms of human thought and activity. They are written in a range of languages (Khotanese and Sogdian [Middle Iranian], Tibetan, Sanskrit, Tangut, Old Uighur, and others), though naturally most are in Chinese. For the purposes of this section, the most vital subset of the Dunhuang manuscripts is a group of between roughly 200 and 800 manuscripts (depending on how they are classified and counted), the content of which may be described as popular literature.

The popular literary works from Dunhuang consist of a variety of poetry, prose, prosimetra, and other genres. Among the more noteworthy genres of such Dunhuang popular literature are lyrics (quzici), ballads and songs (geci), folk rhapsodies (fu), “seat-settling texts” (yazuowen), sutra lectures (jiangjingwen; Sen and Mair, Reference Sen, Mair, Mair, Steinhardt and Goldin2005), expositions of karma (yinyuan, yuanqi), and the like (Schmid, Reference Schmid and Mair2001).Footnote 11 Unfortunately, for the accurate description and classification of Dunhuang popular literary genres, these and many other forms of popular literature found in the cache of manuscripts in the library in Cave 17 are usually lumped under the broad rubric of bianwen.

Within the subset of Dunhuang popular literature, the most vital genre for comprehending the overall development of Chinese literature is that of the transformation texts or bianwen. Since the name of the genre is not immediately transparent, it is necessary to understand what “transformation” means in this context. This is by no means an easy task, and in the first fifty or more years after the discovery of the Dunhuang manuscripts, scholars wrestled over a plethora of interpretations of the term. Some said that it indicated the alternation between sung and spoken portions of prosimetric texts (formerly called “chantefables”), while others argued that it signified the change from the classical/literary language to vernacular language, and there were countless other speculations about its meaning.

Because there was no agreement on precisely what bian meant or what constituted bianwen, there was wild disagreement until the 1970s over how many bianwen there were, with guesstimates ranging from about 80 to 800. (One scholar, who shall remain nameless, even hazarded that there were 8,000!) Given the chaotic situation with regard to the nature of the genre and the numbers, in order to bring a semblance of order to the field of bianwen studies, it was necessary to carefully examine the entire corpus of Dunhuang popular literature and establish criteria that were based on the extant manuscripts that actually bore the designation bian or bianwen in their title. When all of the manuscripts of Dunhuang popular literature (su wenxue) were subjected to this rigorous test, it turned out that there were no more than twenty-eight texts with twelve stories represented (due to multiple manuscripts for some of the stories). Based on a still narrower set of criteria, there are only seven stories represented in the bianwen corpus. However, since there are multiple copies of several of these stories, the total is eighteen to twenty-one extant bianwen manuscripts (Mair, Reference Mair1989b; chapter 2).

The fundamental identifying characteristics of bianwen in the narrow sense comprise

1. a unique verse-introductory formula (“Here is the place where X happened. How shall I describe it?”; cf. the verse-introductory formula of karmic narratives: “This is the time when X happened. What did they say?”);

2. an implicit or explicit relationship to the illustrations, correlating to the verse-introductory formula, where the “place” refers to a scene depicted in the painting that was used as a storytelling aid by the performer;

3. an episodic narrative progression;

4. the homogeneity of language, with a conspicuously greater usage of the vernacular and colloquial language than in typical contemporary writing; and

5. a prosimetric structure in which the text alternates between spoken (prose) and poetic or metrical (sung or cantillated) passages.

These are the seven bianwen stories based on these five characteristics:

1. “The Transformation Text on Mahamaudgalyayana’s Rescue of His Mother from the Dark Regions.” The main manuscript is S2614, but there are eight other copies. The hero’s name in Chinese is Mulian. Relying on the power of the Buddha, he helps his mother escape from hell. This tale is celebrated in later Chinese literature for its evocation of filial piety.

2. “The Transformation Text on the Subjugation of Demons.” This is found in S5511 and two other manuscripts, including the uniquely precious P4524, the only surviving illustrated bian storytelling scroll. This bianwen relates the contest of supernatural powers between Sariputra (one of the Buddha’s chief disciples, who is often paired with Mahamaudgalyayana or Mulian), and Raudraksa, chief of the six heretical masters.

3. “The Transformation on the Han General, Wang Ling.” This is written on S5437 and two other manuscripts. The basis for this tale is a brief account of approximately eighty characters extracted from the biography of Wang Ling in fascicle 40 of the History of the Han Dynasty (Han shu: 40). The author of the transformation text has expanded this into a story that is approximately fifty times the length of the original. It relates how the Chu armies of Xiang Yu repeatedly defeated the Han armies of Liu Bang, leading Wang Ling and his associate, Guan Ying, to make a surprise attack on the enemy camp. A major focus of the story is on the brave, sacrificial role that Wang Ling’s mother plays in encouraging her son in his resolve.

4. [A Transformation Text on Wang Zhaojun; title missing on manuscript]. P2553. This is a version of a very popular legend with a historical basis (History of the Han Dynasty, 9). The heroine is one of the four famous beauties of ancient China. She is married off to a Hun chieftain as a “peace bride.” Along the way, seated on a horse, she plays sorrowful melodies on a balloon lute (pipa) – a poignant scene in the sorrowful tale about her that was often recounted in poems, stories, and dramas, both before and after the bianwen was written.

5. [A Transformation Text on Li Ling; title missing on manuscript]. The manuscript is preserved in the collection of the National Library of China. This heartrending story of General Li Ling’s surrender to the Huns is ultimately derived from the well-known accounts in the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji: 109) by Sima Qian (145–c. 86 BCE), who was directly involved in the original events, and the History of the Han Dynasty (54). Li Ling’s captivity among the Huns was a favorite topic of the Dunhuang authors and was written up in other forms beside the transformation text.

6. [A Transformation Text on Zhang Yichao; title missing on manuscript]. P2962. A vivid, contemporaneous tale of a local hero, this fragmentary account relates the expulsion of the Tibetans from the area around Dunhuang. Scenes from these events are depicted in the wall paintings at the Mogao Caves.

7. [A Transformation Text on Zhang Huaishen; title missing on manuscript]. P3451. Another contemporaneous tale of a local hero, this fragmentary account relates the achievements of Zhang Huaishen, the nephew of Zhang Yichao and his successor as the leader of the Returning to Righteousness Army. Like the Zhang Yichao transformation text, it emphasizes the fighting spirit of the Chinese troops and their valor in battle.

Just from this list of genuine bianwen, it can be seen that the genre – as might well be expected – started with Buddhist tales, since the overall form and language were heavily indebted to Buddhist sources; the form and language were then applied to Chinese historical records and eventually used in local, contemporaneous accounts. For example, the following is a passage from “The Transformation Text on Mahamaudgalyayana’s Rescue of His Mother from the Dark Regions.”

This is the place where Maudgalyayana is led in by the gatekeepers to see the Great King who asks him his business:

When Maudgalyayana had finished speaking, the Great King then summoned him to the upper part of the hall. There he was given audience with Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva to whom he quickly paid obeisance (Mair, Reference Mair1994b: 1100–1101).

The above-cited passage clearly shows the generic features of a bianwen. The passage begins with a unique introductory verse formula “This is the place where …” indicating that this “place” is represented in a scene depicted in the illustrated storytelling scroll. The alteration between the verse (sung) and the prose (spoken) is typical of the prosimetric structure of a bianwen. Further, the passage contains quite a few vernacular phrases, such as 既見 (when … saw), 連忙 (hurriedly), 雖然 (although), 被 (passive tense), and 便 (then) (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Scene of gruesome tortures in hell from the Five Dynasties (907–979) Maudgalyayana transformation wall painting in Mogao Cave 19 at Dunhuang. The monk in white robe is Maudgalyayana. The writing in the vertical cartouche is Old Uyghur and it says: “On a day of the first 10 day period (旬), the fifth month of the Year of the Snake, we two, Sangadas(?) and Birmese, came to this mountain temple, burned incense, and prayed for the cleansing of all our misdeeds! Then we rose, scattered flowers, and bowed before returning to Aqbaliq. Thus I, Birmese, have written this.”

With this general understanding of the corpus and nature of bianwen, returning to the meaning of bian (“transformation”) is essential because it was confusion over that which troubled the study of the genre from the very beginning in the first half of the twentieth century. Perhaps the best way to approach the challenge of exactly what the bian in bianwen signifies is to point out that Monkey, in Journey to the West, possesses seventy-two (a magic number) miraculous bian (“transformations”) that he uses to outwit his opponents. In the “Transformation Text on the Subjugation of Demons,” Sariputra produces the same kind of transformations, using his prodigious mental powers produced through deep, intense meditation. This is graphically depicted in P4524, the illustrated bian storytelling scroll (Figure 7). Employed by the likes of Sariputra and Monkey, such transformations can be thought of as “mind-emanations.”

Figure 7 A segment of the pictorial scroll of the Transformation Text of Conquering Demons, portraying the magical combat between Sariputra and Raudraksa. Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Bianwen are based on nirmana (“metamorphosis”), a core concept in Mahayana (“Great Vehicle”) Buddhism. It is quite in keeping with Buddhist ontology to say that an adept created, made, or produced something (a manifestation) through transformation. It is also common in Buddhist thought and literature to speak of supernatural or magical creations produced through transformation.

Stepping back a bit from such rarefied philosophical notions, for those who are interested in genre studies, the available historical evidence indicates that the performers of bian (“transformations”) made their living by reciting them on the street and were chiefly, if not exclusively, women (Mair, Reference Mair1989b: chapter 5). As for the history and sociolinguistics of “ancient Chinese books,” a curious feature of bianwen is that, to the extent that it can be determined, the scribes and copyists responsible for the manuscripts that have come down to us were “lay students” (xueshilang) who studied a comprehensive curriculum in the monastery schools at Dunhuang (Mair, Reference Mair1981).

Finally, the degree to which bianwen are intimately bound to illustrations cannot be overemphasized. As we have seen, the bian in bianwen quite literally signifies an image or scene that has been manifested through transformation. A close contemporary corollary of bianwen are bianxiang (“transformation tableaux”) or narrative wall paintings (Mair, Reference Mair1986). We cannot, however, directly equate the stories presented in bianwen with those portrayed in bianxiang, since the latter are more overtly Buddhist and scripturally based, whereas the former are more of a folk-type and were dependent upon oral transmission.

The connection with illustrations is further exemplified in pinghua (“expository tales” or “plain texts”) of the Song (960–1279) and Ming (1368–1644) periods, where the upper register of each page is occupied by an illustration of what is going on in the written story at that point. It is as though a picture scroll, such as that employed by the Sariputra picture storyteller, were unrolled and spread out at the top of the page. Such illustrations are a feature of much published fiction during the second millennium CE.

The international dimensions of this type of picture storytelling, whose roots can be traced back to Indian folk literature and art, are evident, for example, in Indonesian/Javanese wayang kulit which is picture storytelling with a scroll, but it is also a clear predecessor of other types of dramatic performance, including the famous puppet theater and shadow play of Indonesia/Java. This connection of Song-Ming pinghua and Tang dynasty bian storytelling with picture scrolls is evidenced by the records of a Chinese traveler to Indonesia who went with Admiral Zheng He (1371–1433/35) as his secretary: He observed that wayang beber picture storytelling was “just like our pinghua back home” (Mair, Reference Mair1988: chapter 3).

Although preserved in manuscripts only in the remote, desert town of Dunhuang, bianwen (“transformation texts”) had an enormous impact on later Chinese popular literature, especially fiction and drama. Dating to the Tang (618–907) and Five Dynasties (907–979) periods as living oral performance texts, these works of popular literature were found in the East Asian heartland as well. Yet we knew of their existence only through rare, scattered historical and anecdotal records that were not recognized for what they signified before the discovery and investigation of the actual bianwen manuscripts from Dunhuang.

Concluding Remarks

Bianwen is an excellent example of how Buddhist literary diffusion gave rise to new literary genres and art forms in China. In response to the question of what bianwen is, we can say that bianwen was a revolutionary medieval genre of popular literature that bequeathed much to the Chinese popular literary and performance tradition, including the ubiquitous prosimetric form of fiction and drama, the fondness for narrative illustrations, and the legitimization of vernacular language (Mair, Reference Mair1994b). While bianwen were not composed exclusively in the vernacular language, they did use a considerable component of language that was neither classical nor literary. As such, it is fair to say that bianwen were the first narrative texts in the history of Chinese literature that included a relatively large amount of vernacularisms, both grammatically and lexically. While sooner or later, the Chinese would have begun to write closer to the way they spoke than to the book language of the typical classical/literary style that had been employed by a minuscule number of literate individuals in pre-Tang times extending all the way back to the beginning of the script in the Shang era (ca. 1600–1046 BCE), there is no doubt that the Buddhist-inspired bianwen hastened the actualization of vernacular writing. Were it not for the chance preservation and miraculous discovery of the Dunhuang manuscripts in the desert frontier of Gansu, much of the true history of the development of Chinese literature might have remained unknown forever.

3 Buddhism, the Literary World, and the “Journey to the West” Stories

India–China Buddhist literary diffusion has profoundly influenced the literary world of Chinese literature. A notable example is the “journey to the West” stories that recount the pilgrimage to India by the legendary Tang monk Xuanzang 玄奘 (602–664, also known by his honorific, Tripitaka 三藏). Xuanzang spent seventeen years in his travels to India to bring the Buddhist scriptures to China (see Figure A3 in the Appendix and the online resources). His heroic journey has given rise to many legends, folklore accounts, stories, performances, and visual arts depicting his pilgrimage.Footnote 12 Influenced by Valmiki’s celebrated third-century BCE Hindu epic Ramayana and Buddhism, the fictive accounts on world travel produced between the Tang dynasty and Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) eventually paved the way for the composition and publication of Journey to the West (Xiyou ji 西遊記, 1592), by Wu Cheng’en – one of the four masterpieces of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The novel has since continuously inspired new literature, art, film, television series, plays, cartoons, computer games, not just in China but throughout East Asia and globally from premodern to modern times (Figures 8–10).Footnote 13 Doubtlessly, Xuanzang’s legendary pilgrimage will continue to stimulate people to tell his timeless tale in countless ways in the future. The “journey to the west” narratives embody early global influences, Buddhist literary diffusion, and modern globalization. Particularly, Journey to the West, like the Ramayana, stands as a widely recognized representative of world literature.Footnote 14

Figure 8 Portrait of Tripitaka, Kamakura Period of Japan (1185–1333).

Figure 9 Jade Rabbit and Sun Wukong, from the series One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892).

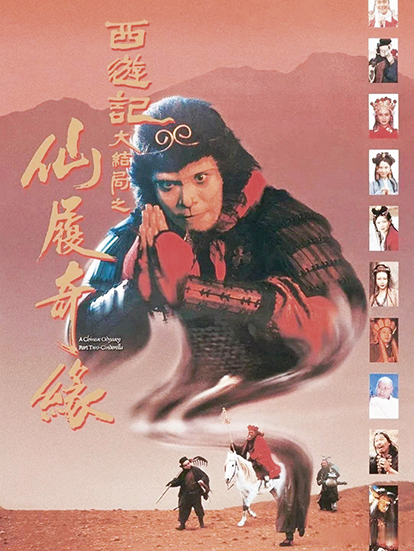

Figure 10 A poster of the Hong Kong fantasy-comedy film A Chinese Odyssey (1995) that is loosely based upon the plot of Journey to the West.

To show that early globalism and Buddhist literary diffusion have influenced the literary world of “journey to the West” stories, this section will begin by examining the Ramayana’s transmission to China and the appearance of the monkey disciple in the “journey to the West” stories after 1000 CE. Then, this section will sketch out the cross-cultural reception of a few important Buddhist deities and schools in China that shape the literary landscape of the “journey to the West” stories. Finally, this section will discuss the Buddhist tropes of magical battles and karmic retribution as integral to the narrative structure of the stories. Overall, this section will look at how Buddhism has impacted the literary world of the “journey to the West” stories, and to a large extent, Chinese literature.

Among the many oral, textual, and visual depictions of Xuanzang’s journey, notable texts that clearly show Buddhist influence include the earliest known written version of the “journey to the West” story (the Kōzanji version) – the shihua (tale interspersed with poems) text titled The Story of How the Monk of the Great Country of Tang Brought Back the Sutras (hereafter The Story of the Monk); a play that was popular in the Song and the Yuan dynasties titled The River-Floating Monk Chen Guangrui; an episode about a dragon king recorded in the Ming encyclopedia commissioned by the Yongle emperor (r. 1402–1424); three Yuan dynasty plays – The Three Transformations of Fierce Nata, The Wild Ape Listening to the Sutra Chanting at Mount Longji (hereafter The Wild Ape), and the twenty-four-act Journey to the West variety drama (hereafter Journey Drama 24), as well as the Ming novel Journey to the West first published in 1592 (Dudbridge, Reference Dudbridge1970).

From Hanuman to Monkey King: The Diffusion of the Ramayana in China

The Monkey from the “journey to the West” stories arguably bears a profound similarity to the simian god Hanuman in the Ramayana. Let us see how similar they are. The following passage from the Ramayana tells us that Hanuman takes a leap over the ocean to Lanka, by shapeshifting to the size of a mountain, to rescue Rama’s abducted wife Sita:

Cupping his hands in reverence to the sun god Surya, great Indra, the wind god Pavana, self-existent Brahma, and all the great beings, he resolved to set forth. Facing east, the clever monkey cupped his hands in reverence to his father Pavana and then began to increase his size in preparation for his journey to the south. Thus, the monkey formed his resolution to jump. In order to fulfill Rama’s purpose, he increased in size – right before the eyes of the monkey leaders – as does the sea on the days of spring tide. In his desire to leap the ocean, he assumed a body of immeasurable size and pressed down on the mountain with his fore and hind feet.

…

So great was his speed that as he leapt up, the trees that grew on the mountain flew up after him on every side with all their branches pressed flat. And so he leapt up into the clear sky, and the force of his haunches was such that he carried with him the trees full of blossoms and love-maddened koyastibhakas.

The following passage from the Journey to the West relates that Monkey King takes a leap across the palm of the Tathagata Buddha on a bet that if Monkey can somersault out of the hand of the Buddha, the Buddha will allow him to replace the Jade Emperor to rule the Celestial Palace:

When the Great Sage heard this, he said to himself, snickering, “What a fool this Tathagata is! A single somersault of mine can carry old Monkey a hundred and eight thousand miles, yet his palm is not even one foot across. How could I possibly not jump clear of it?” He asked quickly, “You’re certain that your decision will stand?” “Certainly it will,” said Tathagata. He stretched out his right hand, which was about the size of a lotus leaf. Our Great Sage put away his compliant rod and, summoning his power, leaped up and stood right in the center of the Patriarch’s hand. He said simply, “I’m off!” and he was gone – all but invisible like a streak of light in the clouds. Training the eye of wisdom on him, the Buddhist Patriarch saw that the Monkey King was hurtling along relentlessly like a whirligig.

As the Great Sage advanced, he suddenly saw five flesh-pink pillars supporting a mass of green air. “This must be the end of the road,” he said. “When I go back presently, Tathagata will be my witness and I shall certainly take up residence in the Palace of Divine Mists.” But he thought to himself, “Wait a moment! I’d better leave some kind of memento if I’m going to negotiate with Tathagata.” He plucked a hair and blew a mouthful of magic breath onto it, crying, “Change!” It changed into a writing brush with extra thick hair soaked in heavy ink. On the middle pillar he then wrote in large letters the following line: “The Great Sage, Equal to Heaven, has made a tour of this place.” When he had finished writing, he retrieved his hair, and with a total lack of respect he left a bubbling pool of monkey urine at the base of the first pillar. He reversed his cloud-somersault and went back to where he had started. Standing on Tathagata’s palm, he said, “I left, and now I’m back. Tell the Jade Emperor to give me the Celestial Palace.”

These two excerpts show that both Monkey and Hanuman share the ability to cloud-soar. Like Hanuman, Monkey can also shapeshift. In fact, he has seventy-two transformations. They both played the role of counselor: Hanuman serves Rama to help him find his wife Sita. Monkey assists Tripitaka to reach India.Footnote 15 But while Hanuman appears majestic and heroic, Monkey is often depicted as crafty, sneaky, and even ugly-looking. Moreover, Monkey is mischievous. Leaving urine on the palm of the Buddha is a typical example of his naughty and unruly character. After all, Journey to the West is a humorous book. Nonetheless, the commonalities between Hanuman and Monkey have naturally led scholars to speculate on the Ramayana’s transmission to China and Indian influence on Chinese literature.

Indeed, even though the Ramayana is long, its episodes were introduced into China in a piecemeal fashion. These episodic tales were continuously referenced, paraphrased, and retold in many medieval Chinese Buddhist texts translated from Indic sutras. Here we only give two of the most significant examples. In 247 CE, Seng Hui 僧會, a monk of Sogdian background, arrived in Nanjing and translated the Sat-paramita-samgraha-Sutra (Sutra of the Collection of the Six Perfections 六度集經) into Chinese. The forty-sixth story in this collection titled “Jataka of an Unnamed King” is a miniature version of the Ramayana. It tells the story of a bodhisattva who is a respected sovereign of his country. His uncle, ruling a different country, is, however, a greedy and ruthless man. The uncle plans to conquer the kingdom of the bodhisattva. He eventually takes over the kingdom, and the bodhisattva and his wife seek shelter in the forests. An evil dragon living in the ocean covets the bodhisattva’s beautiful wife and abducts her. A giant bird comes to the rescue to fight with the dragon. The king climbs mountains to look for his wife and encounters a sorrowful giant ape who divulges to him that his monkey troops were taken away by the king’s uncle. The ape helps the king to defeat his uncle and he regains his monkey troops. Afterward, the monkeys help the king to rescue his wife from the evil dragon. The uncle dies without a child to succeed to his throne and the bodhisattva is welcomed back to be the king. The wife also proved her chastity and loyalty to the king while she was being held prisoner.

Further, in 472 CE, Kimkarya (or Kekaya, Ji Jiaye 吉迦夜), working with the Chinese Sramana Tan Yao 曇耀, translated Dasarata-nidana (The Tale of the Origin of the “King of Ten Luxuries” 十奢王緣) as the first entry in the Saṃyukta Ratnapiṭaka Sūtra (Sutra of Miscellaneous Jewels 雜寶藏經). The story tells of a king named Ten Luxuries who has four wives, each of whom has a son. Ten Luxuries makes one of his sons, Rama, the crown prince. But his youngest wife schemes to make the king appoint her son, Poluotuo 婆羅陀, the crown prince. Rama is subsequently banished to the forest for twelve years. After the death of the king, the conscientious Poluotuo criticizes his selfish mother and seeks his brother in the forest to persuade him to return to the palace to succeed their father. Upon being repeatedly rejected, Poluotuo then takes one of Rama’s shoes back and places it on the throne as if Rama were sitting there acting as the sovereign. After Rama finishes his exile, he returns to the palace and eventually accepts his younger brother’s constant requests to be the king. Because the two brothers are filial to their father and loyal to each other, the kingdom is blessed with a bountiful harvest every year and the people are all wealthy, healthy, and happy (Ji, Reference Ji1991: 207–208).

Together, these two Chinese texts fully translate the storyline of the Ramayana into Chinese, although the stories are instilled with Chinese values such as filial piety and loyalty. While the oral versions are inevitably much longer and detailed, the Chinese versions are similar to all other non-Indian written versions in terms of detail and length (Ji, Reference Ji1991: 208–216). As a result, the stories in the Ramayana spread among monks and laymen, along with the widely circulated sutras.

In fact, Buddhist scriptures contain a large number of folk tales. These humorous stories, clever parables, and moral tales are short and simple, hence easy to remember and spread orally rather than by paper and ink. For example, the Jatakas are a collection of 500 folk stories, parables, and fairy tales that tell the life story of Shakyamuni (Ji, Reference Ji1991: 134–135).

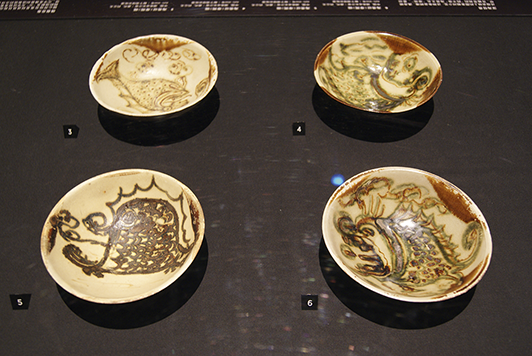

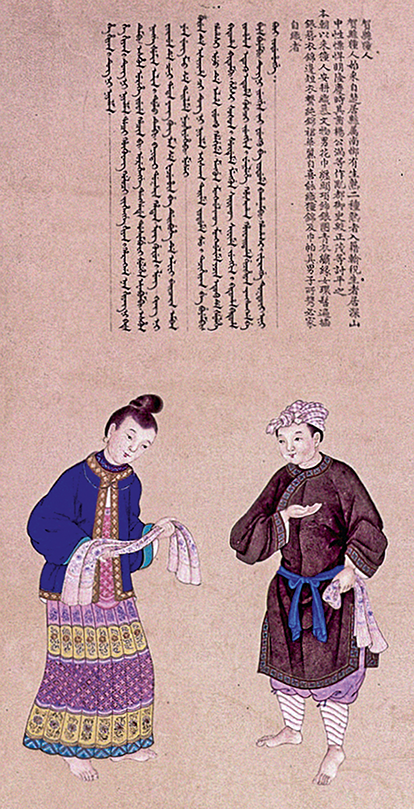

There could be multiple global–regional sources of the Ramayana that influenced its transmission in China. We cannot overlook the considerable possibility that the Ramayana, the stories about Hanuman and the cult of monkeys, were transmitted from Southeast Asia. In the first place, the use of Sanskrit was widespread in Southeast Asia beginning in the fifth century. From Indonesia to Cambodia to Thailand, theatrical and ritual performances of the Ramayana took place frequently in cities and towns in literally every country in Southeast Asia. By the early tenth century, there was already an old Javanese Ramayana, based on the Bhatti-kavya (Ravanavadha of Bhatti) which tells the Indian epic story while illuminating Sanskrit grammar. Since then, more than 200 versions of the Ramayana have been found in Indonesia (Mair, Reference Mair1989a: 670). Stone inscriptions from Prasat Ba An of Cambodia and the bas-reliefs at Angor Wat in Cambodia, Wat Phra Jetubon in Bangkok, and Indonesia’s Panataran and Prambanan all demonstrate the strong currency of the Ramayana and Hanuman in Southeast Asia (Figure 11). In Thailand, although the country’s historical archives were lost in the fire that destroyed the Ayutthaya kingdom (1351–1767) set by the Burmese in 1767, the Thai Ramayana was composed on the order of King Rama I (1782–1809) in an effort to reconstruct the history of Siam (Kasetsiri, Reference Kasetsiri1976: 54). A dozen story scenes, motifs, and archetypes, most of which come from the Laotian Gvay Dvorabhi, concern Hanuman. They are surprisingly like the Monkey King. Noteworthily, Gvay Dvorabhi was orally disseminated (Mair, Reference Mair1989a: 697).

Figure 11 A bas-relief portraying Hanuman in the Ramayana (The Prambanan Temple in Java).

In the second place, the Ramayana was also widely known among the ethnic peoples living on the borderlands of China. For instance, the Thai-speaking Dai people living in Yunnan province, a region bordering Burma, have had many versions of the Dai language translation of the Ramayana. The Dai language is in the same language family of Thai spoken by the majority of the people of Thailand so the Dai people likely received the Hindu epic from Thailand or Burma. Further, in Tibet, Mongolia, and Xinjiang, archaeologists have found manuscripts translated from the Ramayana story in Tibetan, Mongolian, ancient Khotanese, and the Tocharian languages (Ji, Reference Ji1991: 218–238).

In The Year 1000: When Explorers Connected the World – and Globalization Began, the historian Valerie Hansen proposes that 1000 CE was the year when “globalization” – as Hansen puts it – truly began, starting with “Viking” explorers’ journeys across the North Atlantic to Greenland and Canada – a voyage that closed that particular global loop for the first time (Hansen, Reference Hansen2020: 25). In China, the Song and Liao (916–1125) emperors signed the Treaty of Chanyuan in 1005 to establish a century-old agreement that suited both sides. While the Liao in the north turned to the Steppe, forming a cross-regional land route along the Silk Road, the restricted borders forced the Song in the south to explore overseas connections through Southeast Asia. As a result, the coastal cities in the South thrived. Quanzhou, for instance, a port city in Fujian, became one of the most flourishing cities in the world (Hansen, Reference Hansen2020: 23, 158).

After the year 1000, a robust transregional Buddhist network in north Asia came into shape. The land and sea trade routes increased the transmission of Buddhism in northern and southern China. Nomadic polities such as the Khotan, Khitan Liao, and Tangut Xia, as well as the Chinese polities of the Northern and Southern Song all promoted Buddhism. As a result, Buddhist temples, pagodas, and murals thrived (Figure 12).

Figure 12 The 6.7-meter-long bas-reliefs carved during the Song dynasties, from Hangzhou’s Lingyin Temple, depict three stories of eminent monks’ pilgrimages in Chinese history. The two figures on the left are the Indian monks Matanga and Dharmaratna (first century CE), who brought Buddhist sutras to China on white horses. The central carvings feature Zhu Shihang 朱士行 (203–282), the first Chinese monk to journey to the Western Regions in search of Buddhism teachings. The figure on the right represents Tripitaka portrayed as a compassionate, modest, and devout monk.

This thriving Buddhist network brought to China more stories of Hanuman and the Ramayana from India and Southeast Asia than before. Murals and bas-reliefs started to portray the simian disciple and guardian who accompanies the monk Xuanzang on his journey to India. The earliest existing grotto bas-reliefs that feature Tripitaka and Monkey paying tributes to the water-moon Avalokitesvara Guanyin are located in Cave 2 of the Zhongshan grottos in the Yan’an region of Shaanxi province. These bas-reliefs can be dated to 1112 CE during the Northern Song (960–1127). Thirteen more bas-reliefs were produced quickly within approximately ten years in this same region (Wei and Zhang, Reference Wei and Zhang2019: 2–4).

About the same time, a “journey to the West” grotto bas-relief was carved more than 1,200 kilometers from Shaanxi in Sichuan’s Luzhou. One century later, at least six beautiful murals were painted in the Yulin 榆林 caves, Thousand-Buddha caves 千佛洞, and Mount Manjusri grottos of Guazhou in the late Xi Xia dynasty (1038–1227) (Figures 13 and 14). Between 1237 and 1250, two bas-reliefs of a monkey guardian were carved on a pagoda of the Kaiyuan temple of Quanzhou – a port city in Fujian that is 3,400 kilometers from Guazhou – in 1237–1250 (Wei and Zhang, Reference Wei and Zhang2019: 2–4) (Figure 15).

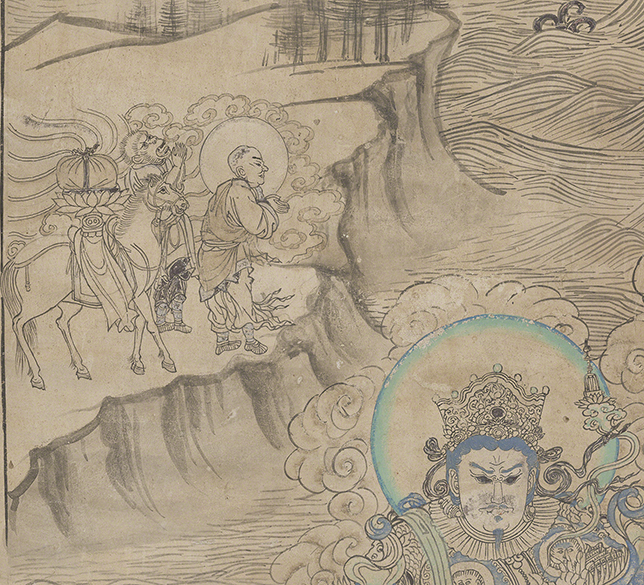

Figure 13 Tripitaka, accompanied by Monkey, paying homage to Bodhisattva Samantabhadra (Yulin Cave 3).

Figure 14 A mural that depicts the water-moon Avalokitesvara Guanyin, visited by Tripitaka and Monkey, who appear in the lower-right corner of the painting (Yulin Cave 2).

Figure 15 Bas-relief of a monkey guardian carved on the pagodas of the Kaiyuan Temple in Quanzhou.

The strongest evidence of the Ramayana’s transmission to China is the monkey guardian in the sculptural relief on a panel at the fourth floor of one of the two pagodas (called the East and West Pagodas 東西塔) built in 1237 in the Kaiyuan 開元 temple in Quanzhou. The monkey guardian shares with Monkey a number of similarities: They are both holding a weapon and wearing a tight-fillet and identical earrings; they both have long hair and an elongated mouth; they have similar ornaments on their forearm and upper arm; and they both possess the ability to leap swiftly.

In short, the Ramayana was spread from India to Southeast Asia and to China. Stories of Hanuman were known to the Tibetans, Mongolians, Tocharians, ethnic peoples in the southwestern region of China, and the Han Chinese. Fostering a robust transregional Buddhist network that encompassed various regions, the first wave of globalism that happened around 1000 CE further facilitated the spread of the Ramayana and stories of Hanuman. Since then, the monkey disciple started to appear by the side of the legendary monk Xuanzang on the murals and bas-reliefs created in that period.

Chinese Reception of Buddhist Deities

The “journey to the West” stories serve as a literary repository of the Buddhist pantheon, weaving deities from diverse Buddhist traditions and historical periods. Initially foreign to the Chinese, this pantheon was gradually assimilated, becoming the vital “world-making power” at the core of the narrative corpus. Compassion, heroism, protection, wisdom, and emptiness function as some of the governing laws of this literary universe.

The first deity to mention is Vaisravana, the god of protection. Originated in the kingdom of Khotan, this Tantric god resides in the north of Mount Meru in the Buddhist cosmos. Often portrayed as holding a mouse that can spit out gold ingots, this deity of luck and wealth protects armies, states, and people. In The Story of the Monk, Vaisravana helps Tripitaka to cross a deep pit, extinguish a wildfire, and halt the flow of a river so that he could continue his journey (Wang, Reference Wang2011: 217–218). Vaisravana became so popular in the Dunhuang region in the Tang and the Five Dynasties (907–979) that Emperor Xuanzong (685–762) of the Tang requested the Tantric monk Amoghavajra (705–774) to summon Vaisravana to protect the Tang army in a battle against the Western Bod, Tajik, and Sogdian forces (Zan, Reference Zan1987: 11–12) (Figure 16). In later stories and films, however, Vaisravana became conflated with and Sinicized into the pagoda-holding Daoist deity Li Jing whose third son, Nezha, is a beloved protective deity in Chinese popular tales.Footnote 16

Figure 16 Painting of Vaisravana, Guardian of the North, shown crossing the waters, floating on purple clouds. In one hand, a golden halberd; in the other, a purple cloud supporting a stupa with a seated Buddha inside. Flames come out of his shoulders. His retinue includes Sri Devi, his sister, holding a golden dish of flowers, the sage Vasu, and one of Vaisravana’s sons. Garuda flies above.

A second interesting deity to mention is Hariti – fertility goddess, healer, and protector of children transmitted to East Asia and Southeast Asia from Gandharan India influenced by Greco-Buddhism. In The Story of the Monk, Tripitaka visits the country of Hariti where he sees many three-year-old children living without their parents and where Hariti bestows elaborate gifts on Tripitaka and his disciples. In Journey Drama 24, Hariti is a demoness and mother of the demon Red Child who snatches Tripitaka. The Buddha then contains Red Child under his alms bowl in an attempt to convert Hariti so as to save the monk. Both the plots are based upon the hagiography of Hariti who was a child-eating demoness before her conversion. To convert her, the Buddha captures her youngest son, Pingala, and covers him under his magic alms bowl. After days of searching for her son in vain and realizing the pain she has inflicted upon parents, the distressed mother repents in front of the Buddha and converts to Buddhism. Hariti’s cult reached its zenith in China and Japan between the ninth and eleventh centuries (Murray, Reference Murray1981–1982: 256). Her cult became secularized after the Song dynasty, as demonstrated by the anonymous Yuan dynasty painting Hariti Raising the Alms Bowl 鬼子母揭缽圖 (Li, Reference Li2008) (Figure 17). Yet her cult declined in Ming–Qing China, probably in part because Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara rose to a prominent status.

Figure 17 Hariti Raising the Alms Bowl, by an anonymous artist in the Yuan dynasty. In the painting, an elegant lady in a pink silk dress looks agonized as she tries to rescue her child from the Buddha’s alms bowl. The surrounding audience sympathizes with her distress.