Introduction

In recent years, younger generations have found accessing affordable, independent housing increasingly challenging (Coulter, Reference Coulter2018; Forrest and Hirayama, Reference Forrest and Hirayama2018; Howard, Reference Howard2024). Escalating property prices have combined with tighter rental sector conditions, diminished social housing supply, less secure employment and squeezed incomes to reduce housing opportunities, especially for younger adults (Lennartz et al., Reference Lennartz, Arundel and Ronald2016). This lies in contrast with the more conducive housing policies and conditions – in lending, prices and rising real income – typical of housing transitions amongst post-war birth cohorts (Forrest and Hirayama, Reference Forrest and Hirayama2018). Concomitantly, housing has become more fundamental to socio-economic security, with homeownership often considered necessary to successful life-course transitions. As such, in the light of the historic housing asset wealth accumulated by many older middle-class households, transfers of parental resources, specifically for homebuying, have become particularly salient to the family careers and life chances of their adult children.

Indeed, older, property-owning generations are increasingly being asked to draw upon their wealth in support of their children’s transitions into owner-occupation (Ong ViforJ et al., Reference Ong ViforJ, Clark and Phelps2023). This development arguably represents a renegotiation of the ‘generational contract’ involving formal and informal exchanges of support between generations, which appears to be shifting back to interpersonal transfers across generations within the family (Albertini and Kohli, Reference Albertini and Kohli2013). This paper seeks to examine this realignment between generations and the role of housing systems, policies and practices therein. Whilst studies have increasingly addressed intergenerational transfers for housing (e.g. Cigdem and Whelan, Reference Cigdem and Whelan2017; Cook and Overton, Reference Cook and Overton2024; Druta and Ronald, Reference Druta and Ronald2017), and the experiences of ‘generation rent’ (Howard, Reference Howard2024; McKee et al., Reference McKee, Moore, Soaita and Crawford2017; Waldron, Reference Waldron2022), older cohorts have received little attention despite growing pressures on them to share their homes or to tap into their own asset wealth in service of their adult children’s needs.

Given increasing pressures on parents to support their children on the housing market in Hong Kong, this paper specifically asks: How do older generations perceive generational inequalities in housing and what do they understand their responsibilities to be (as parents) for housing adult-children or helping them into independent housing? We ask this question with the aim of better understanding how families are responding to diminishing housing affordability, but also the role that housing policy and the welfare system play in shaping intergenerational relations.

We draw empirically on fieldwork in Hong Kong involving a survey with more than 1,000 parents co-residing with adult-children (aged 25–35 years). This is complimented by a series of in-depth interviews with a small sub-sample of parents. Hong Kong provides a provocative case for exploring contemporary intergenerational housing market inequalities and the role of family dynamics. This city’s housing market affordability ratio stood at 18.8 in 2022. This compares with 7.3 in London and 7.1 in New York (Demographia, 2023). Hong Kong’s older generations benefitted substantially from early public housing schemes that facilitated easy access and rapid growth in owner-occupancy rates (Li et al., Reference Li, Du and Wu2022). However, with subsequent house price inflation and few affordable housing alternatives, homeownership has stagnated, with younger people staying longer at home (Forrest and Xian, Reference Forrest and Xian2018).

Hong Kong’s welfare system is characteristically ‘productivist’ (Holliday, Reference Holliday2000), with social policies focussed on supporting working, self-reliant households with the objective of driving rapid economic growth. Housing policy has been a distinct pillar of the Hong Kong model, with public renting and homeownership schemes sustaining high levels of household welfare (Lau, Reference Lau, Groves, Murie and Watson2007). However, housing has incrementally become a major contributor to rising socio-economic inequalities and diminishing social mobility, with responsibility for housing younger adult cohorts increasingly falling on parents as public housing schemes have waned.

This paper continues by exploring contemporary relations between generations and recent disruptions derived from shifts in housing markets and intergenerational distributions of housing wealth. Attention then turns to the Hong Kong case and fieldwork there. The discussion reflects upon our findings in relation to contemporary family life in Hong Kong as well as social and housing policy implications. In concluding, we consider our findings in relation to other societies facing similar intergenerational housing inequality issues. We also reflect on the efficacy of focussing on parents, rather than adult children, to understand the ways housing and life-course trajectories of young people are subject to parental decisions and family resources.

Housing, families and transfers

Generational inequalities

Homeownership expanded significantly across advanced and advancing economies in the latter decades of twentieth century. In Western contexts, growing access to housing assets became increasingly important to the intergenerational settlement as the Keynesian welfare model faded, with property owning households better positioned to look after themselves and less reliant on state transfers (Crouch, Reference Crouch2009). In East Asian ones, meanwhile, the consolidation of wealth in family-owned property bolstered direct intergenerational welfare capacities, freeing the state to focus resources on economic growth, which in turn stimulated property value increases (see Doling, Reference Doling1999). In both cases, policy sought to widen homeownership access as a means to enhance not only individual social mobility and economic security, but also production, consumption and growth (Forrest and Hirayama, Reference Forrest and Hirayama2015).

Late twentieth-century housing and economic policies thus focussed on widening distribution of owner-occupied housing assets, producing cohorts of property-richer older adults in the early twenty-first century. Over time, however, although homeownership and housing wealth became more concentrated amongst older and more middle-class households (Arundel, Reference Arundel2017), homebuying and the potential to amass equity diminished amongst younger cohorts (Howard, Reference Howard2024). The return of rapid house price inflation after the Global Financial Crisis proved a particular challenge to the housing opportunities of younger cohorts. Governments, in various measures, supported post-crisis price recovery but proved decreasingly effective in reproducing homeownership (Ronald and Arundel, Reference Ronald, Arundel, Ronald and Arundel2023).

Schisms in housing asset conditions between cohorts have become increasingly extant across developed economies, raising specific tensions between generations (see Howard, Reference Howard2024). Serving the needs of different generations has become a conundrum for many governments who struggle to address the dilemma of high property values that produce security for older-owners and insecurity for younger people excluded from independent housing careers. Whilst twentieth-century state interventions proved highly effective in stimulating homeownership (e.g. the ‘right-to-buy’ for UK council tenants; government mortgage loans in Japan), state support for owner-occupation in the twenty-first century has suffered diminishing returns and homeownership rates have faded (Lennartz et al., Reference Lennartz, Arundel and Ronald2016).

Tensions between generations are also being played out at the micro-level of families. Whilst older cohorts typically benefitted from housing market developments and realised considerable economic security through the rising value of their homes, they are increasingly called upon to draw on these reserves to assist their offspring in starting independent housing careers (Ronald and Lennartz, Reference Ronald and Lennartz2018). Amongst poorer families, longer co-residence with adult children has provided an alternative solution for parents but also disrupted the formation of new families (Mulder and Smits, Reference Mulder and Smits2013). In either case, the need for older homeowners to address the housing needs of younger kin presents a sharp realignment of intergenerational obligations, with parents assuming increased responsibility for their children’s wellbeing and life-course progression.

Parents, children and transfers

Modes of intergenerational assistance variously include, inter alia, informal help with renovations, sharing of financial knowledge/literacy and prolonged co-residence. The timing of transfers also typically aligns with life-course markers: forming long-term partnerships, marriage, bearing children, etc. (Coulter et al., Reference Coulter, Bayrakdar and Berrington2020). However, under competitive market conditions and intensified focus on homeownership in asset wealth accumulation, the links between family assistance, housing and life-stage have loosened. Similarly, economic support has assumed much greater prominence as a mode of family assistance (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Myers, Painter, Thunell and Zissimopoulos2020; Lux et al., Reference Lux, Samec, Bartos, Sunega, Palguta, Boumová and Kážmér2018; Mulder and Smits, Reference Mulder and Smits2013).

Financial transfers from older family members not only improve individual capacity to buy housing, but also enhance the benefits, with the size and timing of family transfers significantly impacting the housing outcomes of recipients (Guiso and Jappelli, Reference Guiso and Jappelli2002). For example, parental aid can compensate for the absence of savings for a deposit in the early stages of a housing career when earning capacity is limited (Cigdem and Whelan, Reference Cigdem and Whelan2017), thus facilitating earlier access to the market and potential capital gains. Similarly, inter vivo financial assistance or even the anticipation of an inheritance may motivate larger down payments or higher value purchases that advantage the recipient household in the long run (Engelhardt and Mayer, Reference Engelhardt and Mayer1998).

The motivations for parental transfers are argued to be relational, reflecting family practices and the everyday ‘doing’ of family (Morgan, Reference Morgan2011). Finch and Mason (Reference Finch and Mason1993), for example, explored negotiations surrounding the provision and receipt of family support, noting the importance of normative judgements concerning ‘worthiness’. Heath (Reference Heath2018) subsequently illustrated the particularly ‘worthiness’ of housing in generational transfers, with homebuying offspring considered especially ‘deserving’. Transfers typically begin as loans that, with time, transform into de facto gifts. Whilst it is often easier for children to ask for loans over gifts, parents are also less likely to ask for or expect repayment later (Heath and Calvert, Reference Heath and Calvert2013). Druta and Ronald (Reference Druta and Ronald2017) highlight that helping a child buy a home augments their independence and enhances individual financial capacity. Houses also have a particular cultural resonance, constituting a material and symbolic legacy for future generations (Manzo et al., Reference Manzo, Druta and Ronald2019). As such, parents are typically more willing to give larger transfers for home purchase than other purposes.

Financialization processes have transformed housing markets in recent decades, helping reshape normative approaches to parenting and family transfers (Adkins et al., Reference Adkins, Cooper and Konings2021). They have also helped differentiate families by market position and social class habitus. Forrest and Hirayama (Reference Forrest and Hirayama2018), distinguish between real estate ‘accumulating families’ who actively acquire multiple property assets over generations, and ‘dissipating families’ who need to draw down on family-owned property assets to sustain themselves. Similarly, Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Bristow, Faircloth and Macvarish2014) emphasise contemporary middle-class modes of parenting focussed on the competitive advantages of property ownership. By contrast, working-class parenting modes focus on the risks of ‘missing out’ on the property ladder or with sustaining their children in homeownership during economic volatility. Cook and Overton (Reference Cook and Overton2024) thus compare risk-focussed and investment-oriented approaches, emphasising how parents cultivate such sensibilities in their offspring by strategically providing or withholding assistance.

Contexts: welfare regimes and housing systems

Such distinctions in family strategies have recently been identified in China, with parents often planning their children’s house moves and market strategies well in advance of adulthood (Cui and Ronald, Reference Cui and Ronald2024; Deng et al., Reference Deng, Hoekstra and Elsinga2020). Indeed, practices that shape housing transfers vary remarkably between contexts. Southern Europe, for example, is characterised by cultural expectations of long-term housing career support involving prolonged co-residence, often into middle age. In contrast, home-leaving in Nordic Europe occurs much earlier and is typically accompanied by financial assistance (Albertini and Kohli, Reference Albertini and Kohli2013). Whilst cultural norms are influential, they critically reify housing systems and welfare regime features: whereas Southern European welfare regimes rely on family rather than state provision, and housing systems are dominated by owner-occupation, North European regimes are more corporatist and feature offerings of affordable rental housing suitable to young independent households (Tosi, Reference Tosi2020).

Liberal regimes, characteristic of Anglophone countries, are focussed on market provision, especially homeownership, and the cultivation of an individualised, asset-based approach to welfare (Doling and Ronald, Reference Doling and Ronald2010). Along with diminishing access to affordable housing, however, countries such as the UK, Ireland and the USA have seen remarkable shifts to co-residence amongst younger adults and growing reliance on family transfers to get onto the owner-occupied housing ladder (Heath and Calvert, Reference Heath and Calvert2013). In East Asia, meanwhile, where welfare regimes usually align with a ‘productivist’ model (Holliday, Reference Holliday2000), policy commonly supports the provision of housing commodities (owner-occupied) whose increasing asset value supplements the familial base of social and welfare practices (Doling, Reference Doling1999). Thus, whilst market orientated, family housing practices remain linked to filial expectations where younger generations bear responsibility for the welfare care of older ones (Takagi and Silverstein Reference Takagi and Silverstein2011; Yu, Reference Yu2021).

As house prices began to grow across East Asian economies in the late twentieth century, increasing numbers of families aligned their collective resources around the acquisition of housing property, supporting household reproduction. In becoming owner-occupiers, post-war generations essentially became better equipped to support themselves and their elders (Forrest and Hirayama, Reference Forrest and Hirayama2015; Izuhara and Forrest, Reference Izuhara and Forrest2013). Since the beginning of this century, however, East Asian countries have also seen diminishing transitions into homeownership (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Hoekstra and Elsinga2020) and a revival in co-residence (Izuhara Reference Izuhara2020; Li and Ronald, Reference Li and Ronald2025). Parents have consequently become more active in supporting homebuying amongst their adult children. Izuhara and Forrest (Reference Izuhara and Forrest2013), for example, illustrate the growing necessity for urban Chinese families to purchase ‘marriage homes’ for their sons considering the diminishing capacity of offspring to do so independently. Such acquisitions are considered necessary to forming new family households and achieving the economic autonomy necessary to later meet filial obligations. Indeed, social, economic and housing market realignments have had significant implications for generational contracts in such contexts. Despite expectations of young people servicing the needs of their elders, housing market pressures are being borne by older cohorts, with parents taking increasing responsibly for maintaining the life-course transitions of younger generations.

Current research on family change in China and East Asian contexts has largely focussed on issues surrounding elderly care and societal ageing (e.g. Chan, Reference Chan2005; Lau, Reference Lau and Izuhara2013; Lin and Yi, Reference Lin and Yi2013), with considerable attention paid to intergenerational assistance. Many studies, for example, focus on co-residence and how contemporary adult children care for ageing parents (e.g. Izuhara, Reference Izuhara and Izuhara2010; Lin and Yi, Reference Lin and Yi2013), or how older ‘sandwiched couples’ support both ageing parents and adult children (e.g. Tan, Reference Tan2018). Such studies have highlighted the pressures exerted on parents, and in particular, tensions between meeting their own welfare interests and the growing compulsion to assist adult children. Nonetheless, whilst housing plays a clear role, there is little understanding of how parents cope with competing demands on their resources.

Indeed, despite growing concern, practices and policies surrounding intergenerational housing wealth transfers have not been well explored across Asian settings (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Hoekstra and Elsinga2020). Moreover, the focus of extant research has been young people as receivers of assistance rather than the perspective of parents or other categories of donor. Consideration of parental positions would, nonetheless, seem to be critical to understanding the impacts of contemporary social and economic transformations as well as emerging intergenerational tensions, inequalities and injustices, as our study seeks to demonstrate.

Housing opportunities in Hong Kong

Our empirical research focusses on Hong Kong as a rich case for examining the impact of housing market pressures on families and intergenerational relations. This city-state has historically taken a lead role in developing the housing system (Lau, Reference Lau, Groves, Murie and Watson2007). Whilst the Housing Authority (HKHA) established a large public housing base in the 1970s and 1980s – still around 30 per cent of housing in the 2020s – it subsequently promoted the expansion of homeownership through numerous schemes: constructing Home Ownership Scheme (HOS) flats and Tenant Purchase Scheme (TPS) sales to public tenants. Households entering homeownership in the 1990s were particularly advantaged by such schemes as subsidisation later diminished in favour of a more market approach (Li et al., Reference Li, Du and Wu2022). Of the 2.61 million Hong Kong households, approximately 1.3 million are homeowners, of which, around 910,000 occupy private housing and just over 380,000 (around 15.5 per cent of households), live in subsidised homeownership flats (Census and Statistics Department, 2021).

Whilst rates of homeownership peaked at 54.3 per cent in 2004, they subsequently fell back to 51.2% in 2020 following a four-fold increase in apartment prices (Legislative Council Secretariat, 2021). Driving decline has been diminishing numbers of younger adults entering the sector. Whilst the proportion of homeowning heads-of-household aged under 35 years was 22.1 per cent in 1997, it fell to 7.6 per cent by 2019. The ratio of homeowning adults aged over 60 years, meanwhile, almost doubled (Legislative Council Secretariat, 2021). Also significant is the increasing ratio of unmortgaged (older) homeowners, which increased from 48 per cent to 66 per cent of homeowners between 2001 and 2016, reflecting growing intergenerational inequalities in Hong Kong’s housing asset wealth base. Driving this generational division is an underdeveloped state pension sector, with households expected to accumulate enough over their working lives to finance retirement. A Mandatory Provident Fund was introduced in 2000, although the overall social security system remains largely residual. Arguably, these conditions have not only stimulated housing buying as a retirement-focussed, wealth accumulation strategy, but also cultivated an ‘asset-rich income-poor’ elderly population, with around one-fifth of older owner-occupiers living under the poverty line (Legislative Council Secretariat, 2021).

In 2011, a government-supported Reverse Mortgage Programme was launched to allow homeowners aged 55 years and over to extract an income stream from their housing assets. Uptake, nonetheless, has been limited (Doling and Ronald, Reference Doling and Ronald2012). Older households appear more inclined towards managing their own housing wealth, although helping their children has become a competing demand on resources. Between 1991 and 2006, the numbers of young people aged 25–29 years living with parents increased from 56 per cent to 70 per cent, and from 33 per cent to 42 per cent for those aged 30–34 years (Yip, Reference Yip, Forrest and Yip2013). Meanwhile, a recent Housing Authority survey (2018) indicated that transfers to children are commonplace, with 22 per cent of subsidy scheme homebuyers acknowledging parental help with deposits.

In this context, our fieldwork focussed on a number of key issues: how parents view the housing prospects of their adult children and what forms of assistance they expect to provide; how families are adapting ‘strategically’ to shifting social, economic and housing market conditions to maximise the housing opportunities of their youngest members; and how the need to help adult offspring impacts other plans they may have for themselves in later life. Considering the distinct government role housing, with around 45.5 per cent of households in subsidised housing schemes (HOS/TPS and public tenants), we also addressed tenure divisions between households and parents’ expectations of the government.

Methods

Our data draw on a mixed methods study in Hong Kong involving both a large telephone survey and in-depth interviews with parents living with their adult children (aged 25–35 years). The in-depth interviews were an integral part of the survey development process, providing initial insights into parental perspectives on intergenerational assistance. Interviews also elicited supplementary and often unanticipated information on the negotiation of intergenerational support and the everyday practices of family housing. The telephone survey built on the findings of the initial interviews and sought to reveal broader patterns across different groups of parents and families from different housing and social contexts. All telephone survey respondents were asked whether they would be willing to participate further in this research. This provided a base for follow-up qualitative interviews that sought to elicit further insights as well as inform the interpretation of the survey data. The design of the study was thus iterative, with interview and survey stages reinforcing each other. Moreover, the combination of qualitative and quantitative insights provided a particularly effective base for answering the main question of this paper regarding the perceptions of housing market and policy conditions and the practices of older generations in supporting the housing and welfare of younger ones.

The fieldwork began with in-depth interviews with nine parents in the summer of 2020. The interviewee selection targeted households where parents still co-resided with their young, adult offspring and where intergenerational assistance had thus yet to be applied. This provided a focus on households’ sensitivity to the need for children to become independent. The life stage between 25 and 35 years old is demographically dense, normally associated with key transitions related to education and work, partnering, marriage and childbearing (Kohli, Reference Kohli2007). Co-residing with parents at this age is typical in Hong Kong, accounting for 54.4 per cent of people in this age group in 2021, up from 42.5 per cent in 2006 (Census and Statistics 2021). Recruitment was based on referrals from personal networks and snowball sampling. The sampling procedure was purposive and sought to include respondents from a range of tenures: homeowners (private and public) with different mortgage status, and public rental housing (PRH) tenants with various years of residence. This strategically sharpened the focus of the research and the exploration of how different parental resources are mobilised for wider family interests. Moreover, the inclusion of PRH tenants, who represent a large share of Hong Kong households (see below), offered an important point of contrast to homeowning households regarding intergenerational resources and practices applied in support of children’s housing opportunities.

These interviews were conducted with the informed consent of the participants, with clear protocols concerning anonymity, confidentiality and integrity in the storage and reporting of the data. The interviews were carried out by trained researchers and lasted for 40–100 minutes. The initial topic guide was informed by previous studies addressing intergenerational transfers assisting young people into housing, both in Hong Kong (e.g. Forrest and Yip, Reference Forrest and Yip2014; Forrest and Xian, Reference Forrest and Xian2018) and internationally (e.g. Heath and Calvert, Reference Heath and Calvert2013; Lüscher, Reference Lüscher, Rossi and Scabini2012; Manzo et al., Reference Manzo, Druta and Ronald2019; Rowlingson et al., Reference Rowlingson, Overton and Joseph2017). Participants were engaged on social norms surrounding parental responsibilities for adult children; their expectations of giving and receiving family housing support; and their lived experience of co-residence with adult children.

The telephone survey ran from late 2020 to early 2021 and was undertaken by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (PORI). In total 1,012 parents living with their adult offspring were successfully surveyed, with a response rate of 49 per cent. Further details of the telephone survey sample selection can be found elsewhere (see Lau et al., Reference Lau, Yip and Wang2021). Survey questions focussed on six major themes related to intergenerational housing support: (1) life-chances and housing opportunities across generations, (2) housing and life-stage development, (3) intergenerational housing support (i.e. financial and non-financial support), (4) attitudes towards tenure options, (5) co-residence with adult-children, and (6) the role of government in supporting housing needs. Most parents surveyed were aged 51–60 years old (42 per cent) or 61–70 years old (45 per cent). The housing tenure spread reflected the distribution of Hong Kong households, with around one-third being public rental tenants (PRH), 43 per cent regular homeowners in private residential units and 23 per cent homeowners in government housing subsidy schemes (HOS, TPS, etc.). Private rental tenants represent a small and highly variegated group of households and were thus omitted.

Apart from living with their adult children, about two-thirds of parents (65 per cent) surveyed lived with a spouse. Two-thirds (67 per cent) lived with one single adult child. Most parents were either retired (35 per cent) or homemakers (37 per cent). A quarter were engaged in full-time (17 per cent) or part-time (7 per cent) work. Amongst the respondents’ spouses (N = 653), two-fifths were engaged in full-time (35 per cent) or part-time (10 per cent) work, with the rest retired (35 per cent) or homemakers (16 per cent) (Annex 1). Together, the quantitative and qualitative data analysed below illustrate parental norms and attitudes towards their adult children and plans to assist them (or not) in leaving home and forming their own independent household. The data allude not only to interpersonal and intergenerational dynamics, but also how these align with housing system and social policy conditions as well as expectations of life-course and housing pathways.

Results

Intergenerational differences in housing opportunities

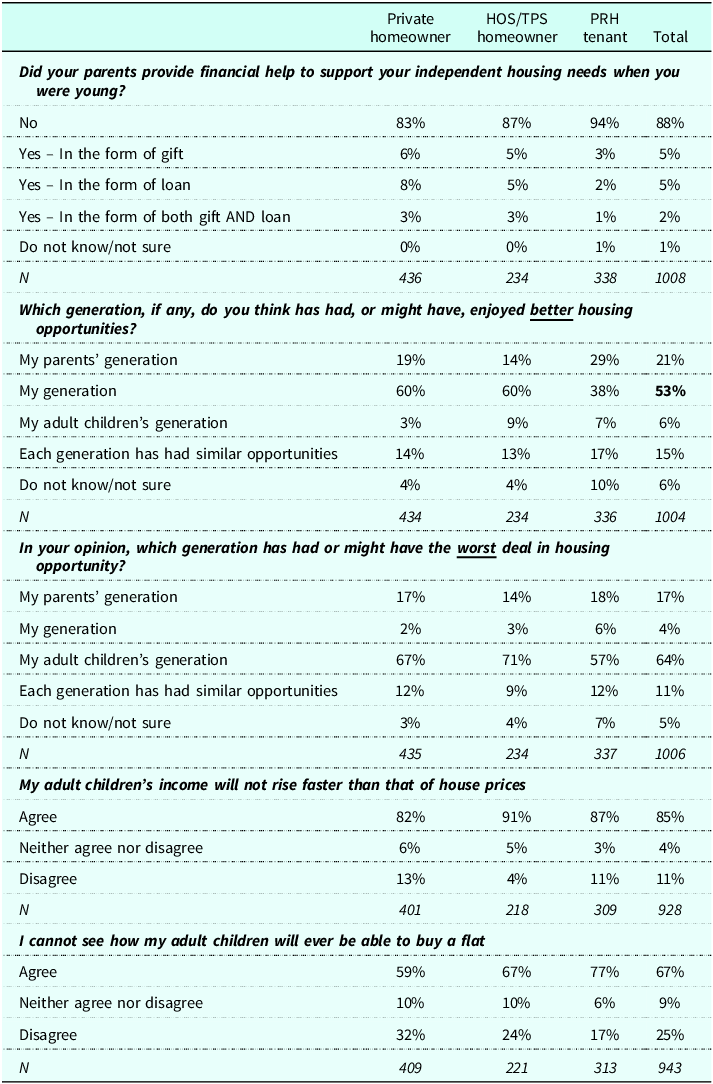

There was considerable sensitivity amongst our respondents to intergenerational differences in housing access that reflected the pattern identified above in terms of aggregate tenure shifts and growing inequalities in housing wealth in recent decades. Of those surveyed, 53 per cent considered their own generation as enjoying much better housing opportunities than both their own parents and adult children (Table 1). This opinion was, however, strongest amongst homeowners (60 per cent) compared with PRH tenants (38 per cent). Despite higher overall rates of owner-occupation, this cohort of parents had received little assistance from their families when setting out on a housing career, with 88 per cent stating they had received no support. Private homeowners were nonetheless more likely to have received something when starting out, either as a gift, 6 per cent, or a loan, 8 per cent. This compared with 3 per cent and 2 per cent, respectively, amongst PRH tenants.

Table 1. Dynamics of intergenerational housing opportunities a

a Figures do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Our interview data provided specific insights into how these parents had navigated the housing system with little financial backing from their families, with government schemes playing a significant role. Indeed, whilst subsidised homeowners were obvious beneficiaries, many private homeowners had started an independent housing career via the public rental sector. As one private homeowner reflected:

I am quite lucky since I was allocated a public rental housing flat… I eventually moved up the housing ladder… I feel quite sad… because many young people who are well educated… no matter how hard-working they are, cannot afford the down payment. (male, part-time taxi driver, aged 61–70 years)

About two-thirds of parents (64 per cent) believed that the younger generation faced the worst housing opportunities of all, with 85 per cent agreeing that their children’s incomes were incapable of keeping up with house price increases. Indeed, about two-thirds (67 per cent) did not expect their children to be capable of entering homeownership in the future. There were, however, some differences in parental views between tenures, with more than three-quarters of PRH tenants unable to see their adult children ever affording to buy a flat compared with two-thirds of subsidised homeowners and 59 per cent of private homeowners. Interviews provided an ostensible consensus on the longer-term implications for their children’s lives: ‘The current property market is crazy. Young people cannot afford to buy a property if they just solely rely on their incomes… This would defer their plans like partnering and marriage’ (HOS homeowner, female, part-time elementary worker, aged 61–70 years).

Financial support strategies

In contrast to their children’s very poor housing prospects, parents possessed very important resources: their own homes and savings. Post-war generations largely managed to capture advantages derived from Hong Kong’s economic development and in the 1980s and 1990s, could also more easily access public housing schemes, propelling them up the housing ladder (Forrest and Xian Reference Forrest and Xian2018; Yip, Reference Yip, Forrest and Yip2013). The accumulation of housing and financial resources critically represented a means to support subsequent generations.

… it is impossible… even if a young person earns a reasonable income, they won’t be able to afford a property. In the past, we were able to pay back home loans… But now, even if you lend them [adult-children] the down payment to buy a home… they might be able to manage the mortgage loan, but not pay back the down payment… Indeed, parents don’t expect their children to pay back the down payment nowadays. (private homeowner, male, full-time high school teacher, aged 51–60 years)

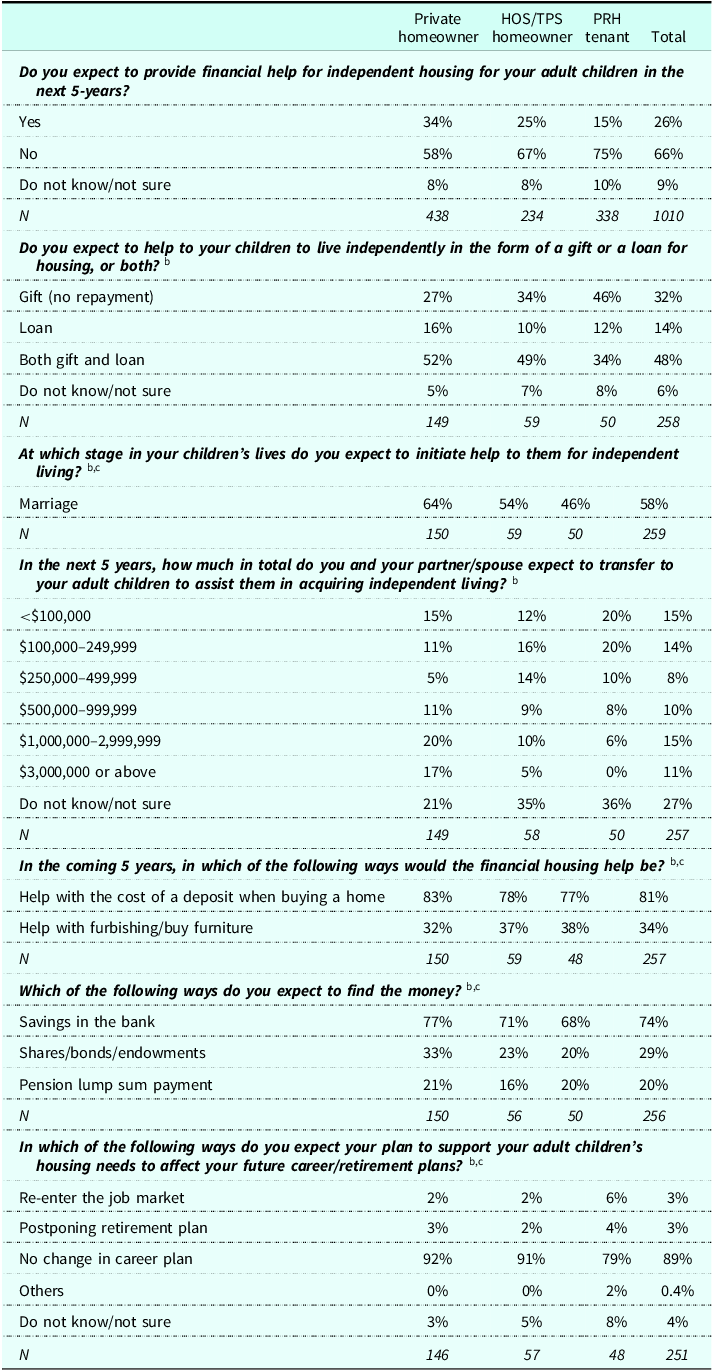

Despite the advantages they had enjoyed and the housing wealth many had been able to accrue, only one-quarter of our survey respondents (26 per cent) planned to provide housing support for their adult children in the coming 5 years. There were, nonetheless, differences between tenure groups, reflecting both different economic situations as well as tenure socialisation (Flynn and Kostecki, Reference Flynn and Kostecki2023; Mulder and Smits, Reference Mulder and Smits2013). Only 15 per cent of PRH tenants intended to provide future financial housing support compared with 25 per cent amongst subsidised homeowners and 34 per cent amongst private homeowners. Across tenures, of those planning to provide support, only 14 per cent were considering a loan, 32 per cent were planning a financial gift and about half (48 per cent) were considering a combination of a gift and a loan. It is worth noting that the preference for gifts over loans was higher amongst PRH tenants than homeowners (Table 2).

Table 2. Parental financial housing support plan: means, timing for initiative and sources of finance a

a Figures do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

b Only respondents who have a financial support plan to their adult children answered this question.

c Multiple response question.

Indeed, in contrast to European cases, where intergenerational gifts have been highlighted (Druta and Ronald Reference Druta and Ronald2017; Heath and Calvert, Reference Heath and Calvert2013; Manzo et al., Reference Manzo, Druta and Ronald2019), the consideration of loans in our interviews reflected a particular understanding of intergenerational (in)dependence and personal self-reliance, with loans symbolically working to remind offspring that they should bear the responsibilities for their own housing needs. As one private homeowner (male) put it: ‘Even though parents can provide financial support, it should be a loan, not a gift. An adult child who borrows money should pay it back… it should be their responsibility’ (retired social worker, aged 61–70 years). Another woman owner-occupier affirmed: ‘I would definitely not treat it as a gift… [adult children] should not take it for granted’ (part-time social worker, aged 51–60 years). Indeed, the idea of ‘responsibility’ was pivotal to many people’s understandings of the generational contract, as one female HOS homeowner told us:

I believe that adult-children should be responsible for their housing, and parental support should only be complementary… As they are adults, they should bear more responsibility… Parents should have a right to choose to offer help, but I don’t think it should be a parental responsibility… [if resources allow] we would try our best to help, but I wouldn’t say it’s a requirement. (homemaker, aged 61–70 years)

Rather than their responsibility, parents planning to assist their children typically viewed financial support as a necessity derived from adverse market conditions. Intergenerational assistance was thus considered essential to overcome financial obstacles that children had limited means to resolve on their own. Without support, parents struggled to imagine how their children would otherwise ever be able to get married or become parents themselves. In this regard, respondents were strategic in ways that echoed other homeownership-orientated contexts (e.g. Cui and Ronald, Reference Cui and Ronald2024). Timing was important, as was clear from our survey, with most parents (58 per cent) planning to provide financial assistance for housing at the moment children married (Table 2).

The size of gifts could also be substantial. Approximately 60 per cent of respondents expecting to provide financial help planned to give sums of HK$100,000 (approximately HK$7.8 = US$1) or more, and as many as 26 per cent expected to give HK 1 million dollars or more. There were predictable differences in the generosity of transfers, with 37 per cent of private homeowners expecting to give one million or more compared with 6 per cent of PRH tenants. Parents were strongly inclined to support home downpayments (81 per cent), whereas only one-third (34 per cent) expected to help finance renovation or new furniture. Giving was largely derived from not only bank savings (74 per cent) and other investments (29 per cent), but also pension savings (20 per cent). Significantly, transfers to children were not expected to disrupt work or retirement plans of donors, with 89 per cent of parents anticipating no impact (Table 2).

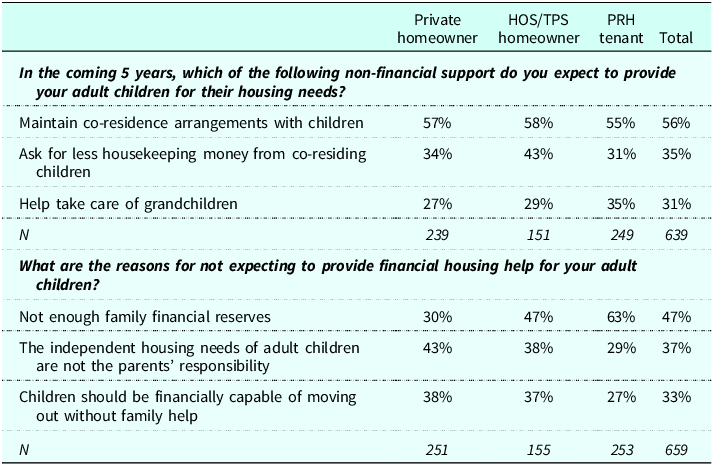

Families and non-financial support

For the many parents not planning to provide financial housing support (66 per cent of respondents), the absence of family financial reserves (47 per cent) and the financial capacity of offspring to move out without family help (33 per cent) were the main reasons given (Table 3). Another key reason offered was that the housing needs of children were not the responsibility of parents (37 per cent overall), reinforcing the discursive findings above. This justification was given more frequently by private homeowners (43 per cent) than by PRH tenants (29 per cent). For the latter, lack of family finances was much more important (63 per cent). As an alternative to financial help, many parents anticipated allowing their adult children to continue co-residing with them (56 per cent), reducing demands for housekeeping contributions (35 per cent) and providing free care for grandchildren (31 per cent).

a Figures do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

b Only respondents who do not have a financial support plan for their adult children answered this multiple response question.

The uneven distribution of housing assets amongst the parental cohort was reflected in different expectations of intergenerational support and different approaches to co-residence with adult children across families. As one female PRH tenant explained: ‘It depends on the parents’ financial capacity… It is impossible… if parents themselves are not able to help at all… [co-residence] is a big help for him [the adult son]. If he moves out, his living cost will increase, and it will be even harder’ (retiree, aged 61–70 years).

In fact, many poorer households perceived supporting children in becoming independent (i.e. transfers for a deposit) as conflicting with their own needs (i.e. extra money for the rent and housekeeping). Indeed, not only were most respondents unlikely to provide children financial help with acquiring a home, but many also appeared to rely on co-residency with them. This was not only the case for PRH tenants. As one TPS homeowner told us: ‘We did not have the Mandatory Provident Fund when we were working… Now we rely on our two daughters’ housekeeping money to support our household expenses’ (female, homemaker, aged 51–60 years).

Housing wealth and welfare anxiety

The particular intersection of housing and welfare practices in Hong Kong was unmistakable in our interviews and helped explain differences in feelings of responsibility for adult children. The historic advance of homeownership and property values has ostensibly produced, on the one hand, one group of economically robust households. On the other hand, in the absence of a welfare state and underdevelopment of a pension system, many households remain economically insecure in later life and strongly dependent on low-cost housing facilitated by either owner-occupation (mortgage-free) or access to public rental housing. Differences between these groups were often reflected in how respondents perceived their relationships with, and responsibility for, their offspring.

As demonstrated by the survey (Table 2), a majority of parents were either unsure or had no expectations of supporting their children in achieving independent living. In interviews, many considered that responsibility for the care of children expired as offspring entered adulthood or completed education. Indeed, continued reliance on family help was seen to undermine transitions to autonomous adulthood. In contrast to the filial norms associated with Chinese families, such parents had few expectations of future help from independent adult children. One private homeowner explained: ‘after completing university, my child should take care of themselves… I do not expect that they support me, and I do not need it either. I also do not want to become a burden to them’ (male, retired social worker, aged 61–70 years).

Many other parents, however, were more reticent about home-leaving children and were unlikely to assist them for different reasons. As discussed previously, many parents rely on the incomes of adult children living at home. Given limited pensions and increasing longevity, older generations now anticipate considerable demands on financial resources in later life. In discussing the future and responsibility for their children, the housing situation in Hong Kong loomed large in interviews, and whilst there was a deep recognition of housing challenges facing young people, there were also deep anxieties about the need to reserve wealth. Thus, whilst lower-income PRH tenants had more obvious incentives to hold on to capital and keep children at home, many homeowners also felt vulnerable. As one HOS homeowner, who was typical of many, told us: ‘…because not all parents are necessarily resourceful or rich enough…they have to consider their later life. For example, I have to think about my financial situation and my daily living costs for the coming ten-to-twenty years of my retirement’ (female, homemaker, aged 61–70 years).

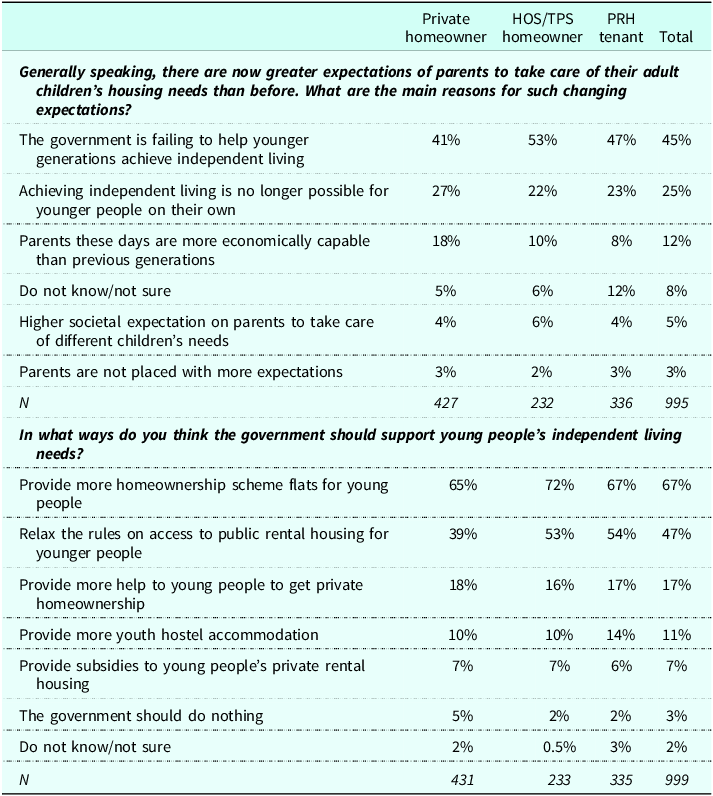

Responsibility and the role of the government

In contrast to social and cultural expectations of contemporary mainland Chinese families (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Hoekstra and Elsinga2020), our analysis of meanings surrounding intergenerational transfers for housing identified a particular reticence amongst parents in Hong Kong. Table 4 presents parents’ expectations regarding intergenerational help, and critically, who they consider responsible. Given some options, respondents were much more likely to find the government accountable, with 45 per cent agreeing that the government was failing to help younger generations achieve independent living. The increased financial capacity of the parent cohort, meanwhile, was considered an unlikely justification for families helping out more (only 12 per cent).

a Figures do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

b Multiple response question.

In understanding intergenerational transfers and family reciprocity in Hong Kong, it is thus critical to account for housing policy and expectations of the government in managing housing conditions. Whilst parents gave credit to the public rental and homeownership schemes that had helped them, in interviews the government was perceived to have failed younger generations and intensified pressures on families. Specifically, most parents found existing land and housing policies to correspond inadequately to the needs of younger generations. For many parents, the government realignment around private capital and real estate was a critical concern.

It is the real estate hegemony… If they could allocate them a public rental housing flat, the cost of living would be very different… The housing problem faced by younger generations in Hong Kong is mainly down to government housing policies and high land prices. (male, retired, private homeowner, aged 61–70 years)

Current supply of public rental housing was considered inadequate to current economic conditions, with application criteria poorly matched to the income conditions of younger generations. Contemporary young adults in Hong Kong are typically better educated than their predecessors and are more typically found in middle-class occupations (Forrest and Yip, Reference Forrest and Yip2014). Public homeownership schemes, meanwhile, have been rolled out at diminishing rates despite increasing demand and growing waiting lists. Parents in our study were particularly sensitive to the inadequacies of policy responses and regarded the government as explicitly accountable for young people’s independent living conditions. Whilst many (47 per cent) thought that PRH application requirements should be relaxed for younger generations, a majority (67 per cent) agreed overall that the government should provide more subsidised housing (Table 4).

Discussion

In the context of widespread declines in housing affordability and homeownership rates amongst younger cohorts that enhance expectations of intergenerational housing assistance, this study has sought to shed light on the impact on, and roles and perspectives of, parent givers. The case of Hong Kong, one of the world’s most expensive housing markets with high rates of homeownership amongst older cohorts, provides an important context for understanding generational inequities in housing wealth and access, and the pressure this places on families. Younger people in Hong Kong are now staying much longer in the parental home and entering homeownership much later in life, if at all (Legislative Council Secretariat, 2021). In understanding the nature and impact of these developments on families, our research provides some important insights.

The accounts of parents were particular illustrative of how families are responding not only to housing market challenges, but also to developments within the productivist welfare system. Housing, both public rental and owner-occupied, were central to household security and sustaining high levels of welfare during Hong Kong’s high-speed growth period (Forrest and Yip, Reference Forrest and Yip2014). The effectiveness and equitability of the housing pillar are, nonetheless, waning, with parents clearly sensitive to diminishing conditions for their children, with, for example, two-thirds believing that younger generations face the worst housing opportunities in generations and are unlikely to ever access owner-occupation or PRH housing on their own. Parental perspectives, as well as family strategies, thus typically mirrored the shifting position of housing in the productivist welfare structure, which is ostensibly demanding a rebalancing of the family and the State as respective guarantors of housing and welfare security.

Despite stress placed on helping out offspring, parents in our study were, on the whole, reticent about providing direct financial transfers. Whilst only around a quarter intended to assist with acquiring independent housing, relatively few of those were prepared to offer an unconditional gift. Most plans involved loans or a combination of loans and gifts that would help with a downpayment on a home. Critically, this constrained response reflected two key and sometimes overlapping dispositions within the parent cohort: the limited resources of many homeowners and public housing tenants facing retirement and expectations of adult children to take responsibility for themselves. Together, our interviews and survey findings supported an image of parents as conservative givers, who largely felt compelled by economic conditions to help their children. Indeed, many considered co-residing with children as a way to support themselves as much as a solution to children’s housing needs.

This orientation is dissonant with many other views and feelings expressed. For example, parents recognised the good fortune of their own circumstances. A large majority were very sensitive to inequalities in access to homeownership and housing asset wealth accumulation between generations. Parents were also deeply aware of the broader significance of frustrated access to independent housing in undermining their children’s ability to form families of their own. Nonetheless, whilst most parents did not expect children to buy flats without help, they often placed the emphasis on children’s responsibilities for themselves. The government was also expected to act. In the context of a successful policy track record that has facilitated access to independent housing for older cohorts, the government was often considered as ‘responsible’ for helping younger people with housing as parents were.

These findings contrast significantly to recent research elsewhere. Property price increases in mainland China, for example, have presented similar challenges. Nonetheless, families in cities such as Shanghai have been shown to have more effectively mobilised, with parents taking far more responsibility for the housing careers of their adult children (Cui et al., Reference Cui, Arundel and Cui2024; Deng et al., Reference Deng, Hoekstra and Elsinga2020), especially those preparing for marriage (Forrest and Izuhara, Reference Forrest, Izuhara and Izuhara2013). Not only is intergenerational financial assistance amongst homeowning families more likely, and relatively more generous, parents also typically cooperate strategically with their children and are more predisposed towards transfers of ‘acquisition capital’ – economic capital, but also financial savvy and propensities for risk taking (Flynn and Kostecki, Reference Flynn and Kostecki2023) – to get children on the housing ladder early with a view to maximising gains and property portfolios (Cui and Ronald, Reference Cui and Ronald2024).

Arguably, housing and policy differences between Hong Kong and mainland cities shape different parental approaches. Hong Kong authorities continue to play a central role in housing as landowner and housebuilder. Indeed, in recent years, continued pressure derived from housing inequalities has driven renewed state focus on public housing policy. Since our research was carried out, more than 9,000 flats have been recovered from non-eligible (wealthier) tenants, and provision of public rental and subsidised flats increased 50 per cent (waiting times for public flats fell from 6.1 to 5.1 years between 2002 and 2025). The latest Long-Term Housing Strategy seeks to add 420,000 new units over the next decade (Housing Bureau, 2025).

Distinct policy and welfare structures in Hong Kong may also be important, with older people potentially more confident in, and dependent on, their subsidised home ownership and PRH flats as the basis of future welfare security. Research has demonstrated that regular welfare schemes are highly stigmatised in Hong Kong, as indicated by very low take-up rates amongst older people (Kühner and Chou, Reference Kühner and Chou2025). However, state supported housing is a largely unstigmatised welfare pillar that, moreover, facilitates public transfers that sustain people in later life without undermining material and non-material family transfers (i.e. gifts/loans, co-residence and contact behaviour), between generations (see also Peng et al., Reference Peng, Wang, Zhu and Zeng2023). Housing policy thus plays a conspicuous role in welfare relations, especially in how families function in relation to the state. For example, whilst the meaning and practice of co-residence in public flats may reflect filial cultural values, they also have value to older households with limited pensions: ensuring low-cost housing as well as care and income from co-residing adult-children.

There are also important contrasts to western housing and welfare regime contexts. For example, there has been a strong reaction to the diminishing capacity of younger people on the housing market in liberal English-speaking countries, which have resulted in galvanised kinship focussed on wealth transfers to children that support transitions to homeownership and different expectations of the generational contract (Cook and Overton, Reference Cook and Overton2024). Parents in Hong Kong demonstrate similar sensitivities and many wealthier families plan large transfers necessary to getting children onto a housing ladder. However, this sense of responsibility seems more tempered across the cohort at large, at least in our study, with far greater emphasis placed on the government and young generations themselves.

Conclusions

Arguably, our study has added some depth to current understandings of intergenerational housing transfers and emerging intergenerational inequalities. A specific contribution is the focus on parental (givers) perspectives as well as consideration of Hong Kong’s social policy and housing system features that contrast to prevailing studies of younger receivers, typically located Anglophone contexts. Our survey draws on a large sample of different households across tenures but is nonetheless limited by a focus on opinions and intentions to give, rather than actual transfers. Our qualitative data have been particularly useful in drawing out the meanings behind survey responses, but are also based on a limited sample, and again, often reflect on intentions rather than behaviour. Whilst insightful, further research focussed on actual gifts and givers, as well as reflecting on real-life family settings, would be more illustrative. Deeper comparisons between urban contexts across the region that draw out the interconnections between market and policy context, and how families mobilise in the face of diminishing housing opportunities, would also be of value. There are also issues related to the gender of children and the impact of siblings (and sons- and daughters-in-law) to be explored.

In addition to providing insights on parental perspectives, our study also contributes to understandings of growing social inequalities derived from housing (Lennartz et al., Reference Lennartz, Arundel and Ronald2016). There are various implications for policy. Firstly, the unequal opportunity structure between cohorts is creating a social landscape of intergenerational dependency that extends children’s reliance on parents, especially for housing. This represents a financial demand on parents approaching retirement and expecting to be self-reliant in old age, including for care. A key issue then is the historic emphasis in policy on homeownership as a resource for later life and the need to enhance other forms of support – pensions and social care – or the continuation of low-cost housing programmes, especially for younger cohorts. Secondly, the extreme difficulties younger generations face in finding independent housing has wider implications in terms of its influence on delayed marriage, late family formation and postponement of first birth. Frustrated housing transitions have been associated with patterns of declining fertility (e.g. Mulder and Billari, Reference Mulder and Billari2010), with inequalities in housing and housing transfers potentially having long-run social policy impacts in terms of increasing numbers of future elderly without children to support them.

Thirdly, the economic and demographic effects of unequal generational housing opportunities are socially uneven. The children of more poorly resourced families face greater difficulties in transitioning to marriage and entering homeownership and thus acquiring similar resources for subsequent generations. In other words, existing inequalities in housing tenure and wealth are potentially being reproduced across generations and becoming more polarised over time, with intergenerational inequalities thus enhancing intragenerational inequalities in the long term (Arundel, Reference Arundel2017; Forrest and Hirayama, Reference Forrest and Hirayama2018). This is an issue for many societies but appears particularly salient to the development of social conditions in Hong Kong.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Public Policy Research Funding Scheme from the Policy Innovation and Co-ordination Office of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region under grant no. 2019.A3.017.19B. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the late Professor Ray Forrest who was the former principal investigator of the project. We would like to express our gratitude to all parties who have provided us support for questionnaire design, and sample recruitment of the study. We would also like to thank all participants who took part in the in-depth interviews, telephone survey and post-survey interviews.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was obtained from the Sub-Committee on Research Ethics of the Research Committee at Lingnan University (ref. no.: EC-011/1819).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.