Introduction

Public institutions in Europe—such as unemployment agencies and tax services—are increasingly digitalising their services (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Yan, Ding, Wang, Jiang and Zhou2012; Schou & Pors, Reference Schou and Pors2019). This aspect of digital public services, which is often termed “e-government,” allows citizens to communicate with public institutions digitally through their websites, via email, or other relevant digital platforms (Reddick & Turner, Reference Reddick and Turner2012). One major justification for the digitalisation of public services is cost reduction. Digital public services purportedly streamline bureaucracy by reducing face-to-face interactions between citizens who use these services (henceforth users) and public service workers (Mattsson, Reference Mattsson, Finneman, Mattson and Andersson2016). Another justification for digital public services relates to improving users’ satisfaction with them (Nusir & Bell, Reference Nusir and Bell2013; Cordella & Tempini, Reference Cordella and Tempini2015).

To date, most research on digital public services and user satisfaction focuses on citizens who use these services with respect to specific public institutions such as unemployment agencies, tax services, and public health services (e.g. Jimmieson & Griffin, Reference Jimmieson and Griffin1998; Kazemi & Kajonius, Reference Kazemi and Kajonius2021). Conversely, this research has paid much less attention to the impact of digitalisation in one specific public institution that non-citizens will exclusively encounter—migration agencies (henceforth MAs). Like other public institutions, MAs have also digitised their services, albeit with some variation between European countries (European Migration Network, 2022). Therefore, with this paper, we aim to add a new dimension to the digital public service literature that specifically concerns migrants by examining their experience of digital services when applying to an MA. Migrants today often apply for their relevant permits first through digital platforms of MAs before they even meet a worker from these agencies. For some permits, migrants may not even have a single face-to-face interaction with a worker. However, this can vary depending on the type of application. Thus, examining the understudied impact of MAs’ digital public services on migrants’ satisfaction should take this variation into account. Additionally, the digitalisation of MA services may introduce bias against certain migrants who are less comfortable using digital public services. Rich research on variations in citizens’ use of digital services in other public institutions shows that older and less-educated citizens use digital public services less (e.g. Friemel, Reference Friemel2016; Scheerder et al., Reference Scheerder, van Deursen and van Dijk2017). Even if they are compelled to use digital services as public institutions shrink their non-digital ones, they may still use them less effectively than citizens who are at ease with digital services. In turn, these citizens may be more likely to feel dissatisfied with this turn towards digitalisation in public services. Different groups of migrants may then also vary in their satisfaction with digital MA public services.

Migrants’ satisfaction with MAs’ digital public services matters because these agencies are the first public institution that they will encounter in the country to which they are migrating. Initial satisfaction or dissatisfaction with this public institution may shape how migrants subsequently interact with and perceive other public institutions in the same country (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004). Initial satisfaction may encourage migrants to interact actively and foster fruitful interaction with other public institutions, which may then improve trust in them too. Conversely, initial dissatisfaction may discourage migrants from doing so, even if interaction and communication with public institutions is necessary in most European countries if migrants (as well as citizens) are to effectively access their social rights (Ferrera et al., Reference Ferrera, Corti and Keune2023).

The relevance of these findings pertains to migrants’ access to social rights. We suggest that these findings about digital public services for migrants can be understood within the context of social citizenship and social rights. Social citizenship, a concept developed by T.H. Marshall (Marshall and Bottomore, Reference Marshall and Bottomore1987), entails a set of rights to access welfare and fully participate in society. Social rights entail access to healthcare, food, and housing in its most basic form but also the right to economic welfare more broadly, education, and participation in culture and social life (Moses, Reference Moses2019). These rights are provided and enabled by institutions. Due to digitalisation trends, the notion of digital citizenship has been developed (Mossberger, Reference Mossberger2008) to describe rights, responsibilities, and competencies required for individuals to participate fully in society through digital means. We argue that this should also involve the inclusion of digital governance and services such as digital public services when applying for a permit to an MA as a form of digital social citizenship. The use of digital public services has been shown to be related to higher satisfaction with the services received (e.g. Welch et al., Reference Welch, Hinnant and Moon2005), therefore, it could be argued that access to digital public services is a form of digital social citizenship. While a growing body of research examines social citizenship and access to social rights for migrants (e.g. de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Ruijtenberg, Chakkour, Botton, Vollebergh and Marchesi2024; Boffi, Reference Boffi2025), we suggest that this line of inquiry should be expanded to include digital social citizenship. In this context, the concept refers to the right of migrants to be digitally included in ways that enable empowerment (Jæger, Reference Jæger2021), not only during the integration process in the host country, but also at earlier stages, such as when applying for different permits through an MA, especially when initial experiences can spillover and shape latter experiences with other public institutions.

For these reasons, studying the digitalisation of public services from the perspective of migrants is essential (see Tazzioli, Reference Tazzioli2023). In sum, we aim to fill a dual gap on migrants and MAs in the literature on the impact of the digitalisation of public services. We ask:

-

• Which groups of migrants are more likely to use digital services when interacting with migration agencies?

-

• How does the use of migration agencies’ digital public services affect migrants’ satisfaction with these agencies?

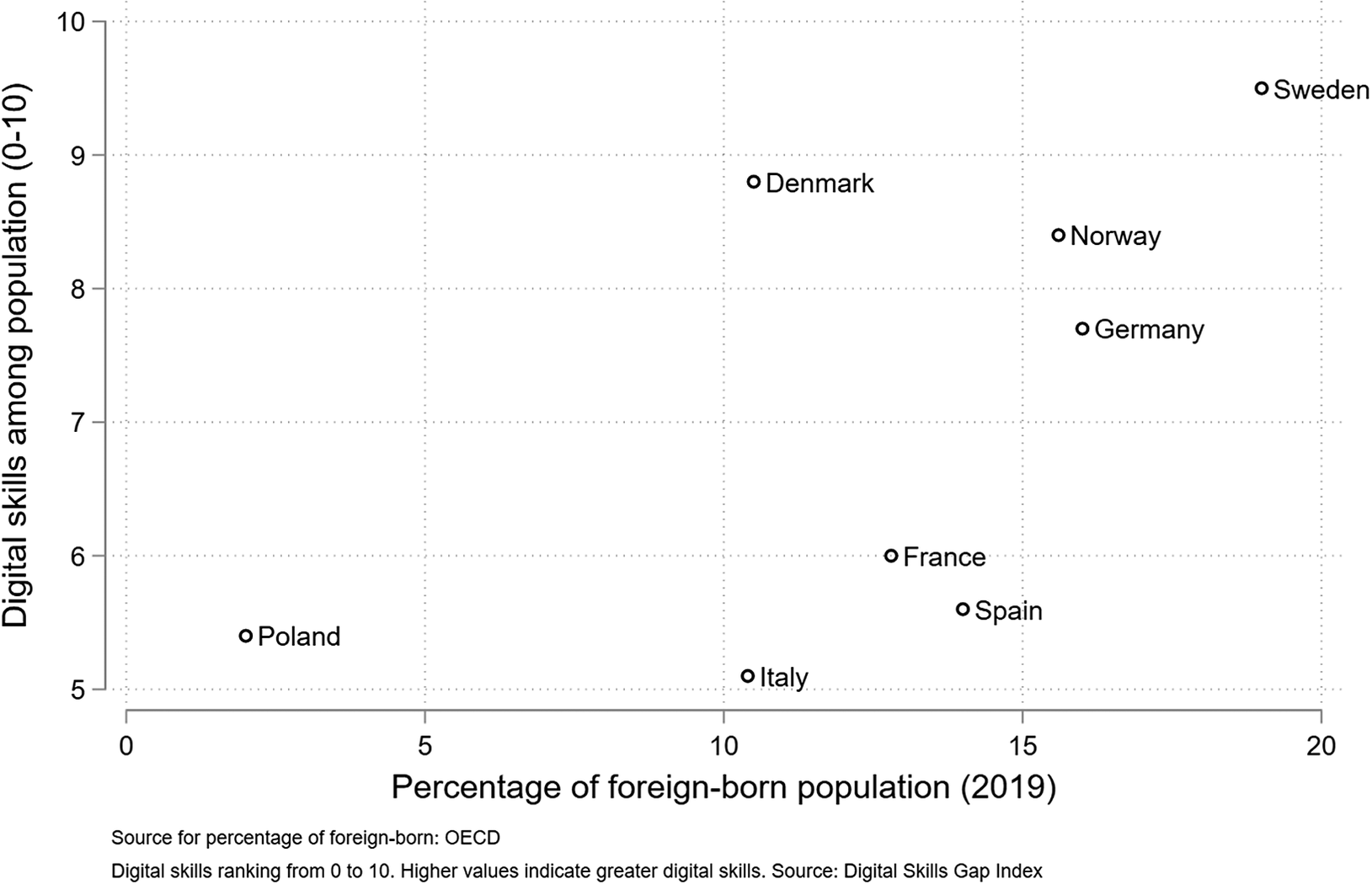

To examine these questions, we leverage a unique dataset consisting of 22,674 migrants who received a decision on their application from the Swedish Migration Agency between 30 March 2019 and 30 March 2020. The sample is representative of the most common demographics such as gender and age. Most publicly available large-scale individual-level datasets are used to study the satisfaction of users of public services (e.g. Jimmieson & Griffin, Reference Jimmieson and Griffin1998). Only a few studies observe migrants’ satisfaction with public services (e.g. Schierenbeck et al., Reference Schierenbeck, Spehar and Naseef2023 based on interview data). Even if migrants are part of these few studies, they account for too few of these dataset observations or are often insufficiently informative to adequately disaggregate migrants’ sociodemographic backgrounds, and crucially, the type of permit applied for. Our unique dataset overcomes these limitations and allows us to directly study migrants during the digitalisation of MA services. Sweden is a unique and important case because it has a high proportion of foreign-born people living in the country (compared to other EU countries), due to high levels of immigration in recent decades; concurrently, it has a high level of digital skills among its population due to its overall high level of digitalisation. Figure 1 illustrates Sweden’s unique position in comparison to other EU countries. Since 2014, the Swedish Migration Agency has digitised many of its services (e.g. online systems for managing residence permits) in line with that in its other public institutions (European Migration Network, 2022). Some applications, such as those for citizenship, are almost completely digital, where the submission and outcome (including appeal) do not include any instance of face-to-face interactions with workers from the agency. Conversely, applications for some permits, such as asylum, remain mostly face-to-face (Migration Agency, 2024). The Swedish Migration Agency’s tendency to digitise some types of permit application but to retain face-to-face interaction for a few others is not unique but is also found in other Nordic countries like Finland and Denmark and is increasingly adopted in European countries like France and Portugal (European Migration Network, 2022). As such, our analysis of the Swedish case is relevant to other countries whose MAs are also embracing similar digitalisation trends.

Figure 1. Scatterplot of the foreign-born population rate and level of digital dkills in selected EU countries.Source: Digital Skills Gap Index & OECD. Note: Digital skills ranking from 0 to 10. Higher values indicate greater digital skills.

In the following sections, we first briefly review the literature on variations in the use of digital public services across different sociodemographic groups; we then use this to elaborate on our expectations of differences in such preferences amongst migrants. Next, we discuss how MAs’ use of digital public services impacts migrants’ satisfaction with them and suggest how this impact is contingent on the type of permit applied for. Then, we present our data and analytic strategy. The penultimate section describes the results and the final section discusses them and concludes the paper.

Preferences for digital public services among citizens and migrants

The rich literature on digital divides shows that there is unequal access to and use of digital technologies among citizens (e.g. Aleixo et al., Reference Aleixo, Nunes and Isaias2012; Neufeind et al., Reference Neufeind, O’Reilly and Ranft2018; Chohan & Hu, Reference Chohan and Hu2022; Tremblay-Cantin et al., Reference Tremblay-Cantin, Mellouli, Cheikh-Ammar and Khechine2023). Van Dijk (Reference Van Dijk2020) posits that citizens who have personal and positional factors less amenable to using digital technologies and have fewer resources are less likely to use them, especially technologies with technical characteristics that do not lend themselves to being readily used. Focusing more on specific factors, Chohan and Hu (Reference Chohan and Hu2022) note that citizens who lack information and communication technology (ICT) literacy, have limited physical access to technology, and have little awareness of these technologies are less likely to use digital ones. Additionally, Tremblay-Cantin et al. (Reference Tremblay-Cantin, Mellouli, Cheikh-Ammar and Khechine2023) suggest that citizens’ perceptions of the value and usefulness of digital public services also affect their use of them. Furthermore, Al-Hujran et al. (Reference Al-Hujran, Al-Debei, Chatfield and Migdadi2015) show that citizens who perceive value in using digital public services and consider them accessible are more likely to prefer using them.

Whereas most of the literature studying the determinants of digital public service use focuses on citizens, only a few focus on newly migrated people. Among these few, the focus is on migrants’ use of digital tools for integration in their host country (e.g. Alam & Imran, Reference Alam and Imran2015; Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Coles-Kemp and Talhouk2020; Alonso et al., Reference Alonso, Thoene and Dávila Benavides2021) and their experience with digital tools to access general public services (e.g. Safarov, Reference Safarov2023). However, none focus on migrants’ use of digital public services and satisfaction with the MA. It is essential to close this gap because migrants differ from citizens in at least two regards. First, migrants are more likely to experience language barriers when accessing digital public services than citizens (Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Jang, Vaughan and Garcia2020). Second, migrants will encounter a public institution that citizens are unlikely to come across–the MA. In fact, migrants will first encounter MAs before interacting with other public institutions of the host country. Hence, their experiences with MAs may later shape their use of other digital public services.

Overall, one may plausibly expect migrants’ use of digital public services in MAs to be similarly influenced by factors affecting citizens’ use of other public services. Like other citizens, migrants with personal and positional factors amenable to digital public service use—as well as with resources that facilitate such use—are more likely to use such services. We expect younger and more highly-educated migrants to be more likely to use MAs’ digital public services than older, less-educated migrants. While acknowledging heterogeneity among different cohorts (Choi & Park, Reference Choi and Park2006; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Dai and Zhang2007; Rey-Moreno et al., Reference Rey-Moreno, Medina-Molina and Barrera-Barrera2018; Janschitz & Penker, Reference Janschitz and Penker2022), younger migrants may, overall, possess digital skills more readily than older migrants, which may lead them to use digital public services more. More highly-educated migrants may have greater experience with digital use than less-educated ones and may thus use the digital public services of MAs more (Choi & Park, Reference Choi and Park2006; Rey-Moreno et al., Reference Rey-Moreno, Medina-Molina and Barrera-Barrera2018).

However, we also contend that migrants’ use of MAs’ digital public services also depends extensively on the availability of digital public services. Although MAs have digitised applications for a range of permits, some remain less digitised and retain traditional channels of communication such as face-to-face interactions, letters, and conversations (Reddick & Anthopoulos, Reference Reddick and Anthopoulos2014; Madsen & Kræmmergaard, Reference Madsen and Kræmmergaard2015). Typically, permits—such as those for asylum-seekers—with less-digitised applications are more complex and need to abide by stricter conditions. Conversely, comparatively more straightforward applications like those for work permits and student visas are more (or even completely) digitised. In other words, even if there is a demand among some migrants to use digital public services, there may not be enough supply available. Thus, migrants are more likely to use digital public services when applying for permits with applications that have undergone greater digitalisation. We set out our first set of hypotheses below:

Hypothesis 1a: Migrants’ use of migration agencies’ digital public services varies between the different application permits.

Hypothesis 1b: Younger and more highly-educated migrants are more likely to use migration agencies’ digital public services than older and less-educated migrants respectively.

Hypothesis 1c: The extent of educational and age variations in the usage of digital public services depends on the type of application permit.

Digital public service use and migrants’ satisfaction with migration agencies

Research shows that there are several factors that affect users’ satisfaction with public institutions. Citizens’ (expected and perceived) experiences of service quality and trust in public institutions have been found to affect their satisfaction with them (Jimmieson & Griffin, Reference Jimmieson and Griffin1998; Van Ryzin, Reference Van Ryzin2004; Jilke, Reference Jilke2018; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen, Petrovsky and Walker2022; Petrovsky et al., Reference Petrovsky, Xin and Yu2023). Conversely, the sociodemographic background of citizens who use these services appears to have mixed effects on these citizens’ satisfaction with public institutions (Rey-Moreno et al., Reference Rey-Moreno, Medina-Molina and Barrera-Barrera2018). Crucially, research demonstrates that the use of digital public services affects users’ satisfaction with public institutions (e.g., Welch et al., Reference Welch, Hinnant and Moon2005; Schou & Pors, Reference Schou and Pors2019). Users of digital public services report higher satisfaction with the services received due to greater convenience, shorter (if any) waiting times, and users’ ability to make their own choices (e.g. Welch et al., Reference Welch, Hinnant and Moon2005). Conversely, there is less satisfaction with non-digital channels because contacting via phone or booking an appointment may entail long queues or be unsuccessful, leading to frustration (Reddick & Turner, Reference Reddick and Turner2012; Soares & Farhangmehr, Reference Soares and Farhangmehr2015; Rey-Moreno et al., Reference Rey-Moreno, Medina-Molina and Barrera-Barrera2018).

Likewise, we expect migrants who use digital public services to report higher satisfaction with the MAs’ services. When migrants contact MAs using non-digital channels, they are often confronted with long waiting times and queues (Tazzioli, Reference Tazzioli2023). The introduction of digital public services was deemed by MAs to be one solution to resolve this problem (ibid.). When migrants use MAs’ digital public services, they may avoid these problems and feel less frustrated with their interactions.

However, we contend that differences in their satisfaction with MAs between migrants who use digital public services and migrants who do not may vary based on the type of permit application. There are at least two reasons for this variation. First, for comparatively more complex application types such as asylum permits, which feature limited digital public services, the use of these services may have a limited impact on migrants’ satisfaction with MAs. Instead, the numerous and often iterative procedures that migrants need to complete for complex applications may exert a greater impact on their satisfaction. That is, migrants are likely to be frustrated by these procedures, even if there are limited instances of using digital public services when applying for complex permits. Conversely, digital public service use may exert a greater influence on migrants’ satisfaction for less complex applications, such as student permits, which already demand less from the applicant. With digital public services, migrants can potentially bypass queues and waiting-times for non-digital channels and complete their applications at their own convenience.

Second, applications for different permits have varying success rates. For example, applications for asylum-seeker permits are typically less successful than those for student permits. Based on rich research on outcome bias in the evaluation of decisions (e.g. Baron and Hershey, Reference Baron and Hershey1988), it is plausible that migrants’ satisfaction depends on the likelihood of success regarding their application permits. Migrants applying for permits with lower success rates may feel more frustrated with the MA than those applying for permits with higher success rates. If outcome bias affects migrants’ satisfaction with MAs, then applications for permits with a lower/higher success rate may dampen/strengthen the impact of digital public services on this satisfaction.

We set out our second set of hypotheses as follows:

Hypothesis 2a. Migrants who use digital public services report higher satisfaction with migration agencies.

Hypothesis 2b. The difference in satisfaction with migration agencies between migrants who use and those who do not use digital public services is dependent on the type of application permit.

The Swedish case

Migration to Sweden and the Swedish Migration Agency

We examine our hypotheses through the case of migrants applying to enter Sweden with the Swedish Migration Agency. Sweden is a country of immigration. In 2020, 20 per cent of the Swedish population was foreign-born (Statistika Centralbyrån, 2022). After World War II, Sweden saw migrants coming from Germany and other Nordic and Baltic countries. This wave of immigration was then followed by a wave of labour immigration up to the 1960s. During this time, migrants from Greece, Italy, Finland, Turkey, and the former Yugoslavia came to Sweden seeking job opportunities (Swedish Institute, 2023). In the 1980s, Sweden started to receive more asylum-seekers from countries such as Chile, Iran, and Iraq (Lundh & Ohlsson, Reference Lundh and Ohlsson1999). In the 1990s, Sweden received many asylum-seekers from the former Yugoslavia. From the 2000s onwards, Sweden also received an increased number of EU citizens, mostly seeking work opportunities (Swedish Institute, 2023). Overall, Sweden’s immigration policy was perceived as exceptionally welcoming. However, in 2015, there came a drastic change in Sweden’s progressive approach towards receiving migrants, with the country shifting to a restrictive migration policy approach and a tightening of asylum laws (Emilsson, Reference Emilsson2018). Today, migrants are often from both within and outside the European Union (EU), with the most common countries of origin in 2020 being Great Britain, India, Germany, Denmark, the USA, Norway, Poland, Turkey, Spain, Finland, and Syria (Statistika Centralbyrån, 2022). Application types range from work and student permits to asylum.

Like other MAs in Europe, the Swedish Migration Agency is undergoing a long-term digital transformation and has increased its use of digital technologies with respect to migration and asylum (OECD, 2022). Digital services are available for making appointments, lodging, tracking, and processing applications, and receiving outcomes (OECD, 2022). While online appointment systems are now common in Europe, online application platforms and the remote tracking of the applications’ progress remain variably adopted across Europe (OECD, 2022). Notably, the adoption of these digital public services does not entail a complete phase-out of non-digital channels of communication and application. Overall, Sweden is one of the European countries that have adopted more digital public services, including its MA. Thus, the findings of the Swedish case about migrants’ unequal use of the MA’s digital public services and their satisfaction with the MA are relevant for other Western European countries whose MAs are undergoing similar digital transformations and adopt more digital public services (European Migration Network, 2022).

The complexity of permit applications to the Swedish migration agency and the extent of their digital public services

The application process differs for (a) work permits, (b) student permits, (c) family reunion, (d) asylum or (e) citizenship. Each involves different levels of e-government during the application. Applications for asylum can only be made in Sweden and can be handed in at one of the MA’s application units. This application requires a lot of personal contact with the MA and involves several stages (for example, due to interviews), but digital skills might simplify the process of seeking and understanding information online. We summarise the complexity, e-government level, required digital skills, and acceptance rates for the different permit applications in Table 1.

Table 1. Application form, complexity of the process and E-government

Note: Information in the table is based on the description of application processes on the MA webpage (Migration Agency, 2024) and on data received by the unit for statistical support at the MA in April 2024.

Table 1 summarises the complexity, e-government level, required digital skills, and acceptance rates for different permit applications.

Data and method

Data collection and sampling

The survey data were collected by the Swedish Migration Agency for internal use in a bid to improve applicants’ service experience. The survey was designed by the first author and the MA, but the data were collected and handled by the MA solely, thereby all ethics requirements are the responsibility of the MA. The MA administered all the steps of the data collection and Author 1 received the anonymous survey data after the collection was completed. The sample consists of all migrants who received a decision on an application from the MA between 30 March 2019 and 30 March 2020. A web survey was sent out to 99,947 people—i.e. all applicants with a registered email for their individual case application in April 2020. Sending the survey only to individuals with a registered email address poses a form of selection bias whereby individuals who did not register an email address in their application were excluded and only individuals with better digital skills were surveyed. Additionally, the survey was anonymised as it did not contain information on the respondents’ email addresses. Respondents were informed at the start of the survey that participation was voluntary and that their answers would be anonymous. The groups who received this survey had applied to the MA for a work permit, a student permit, family reunion, asylum or citizenship.

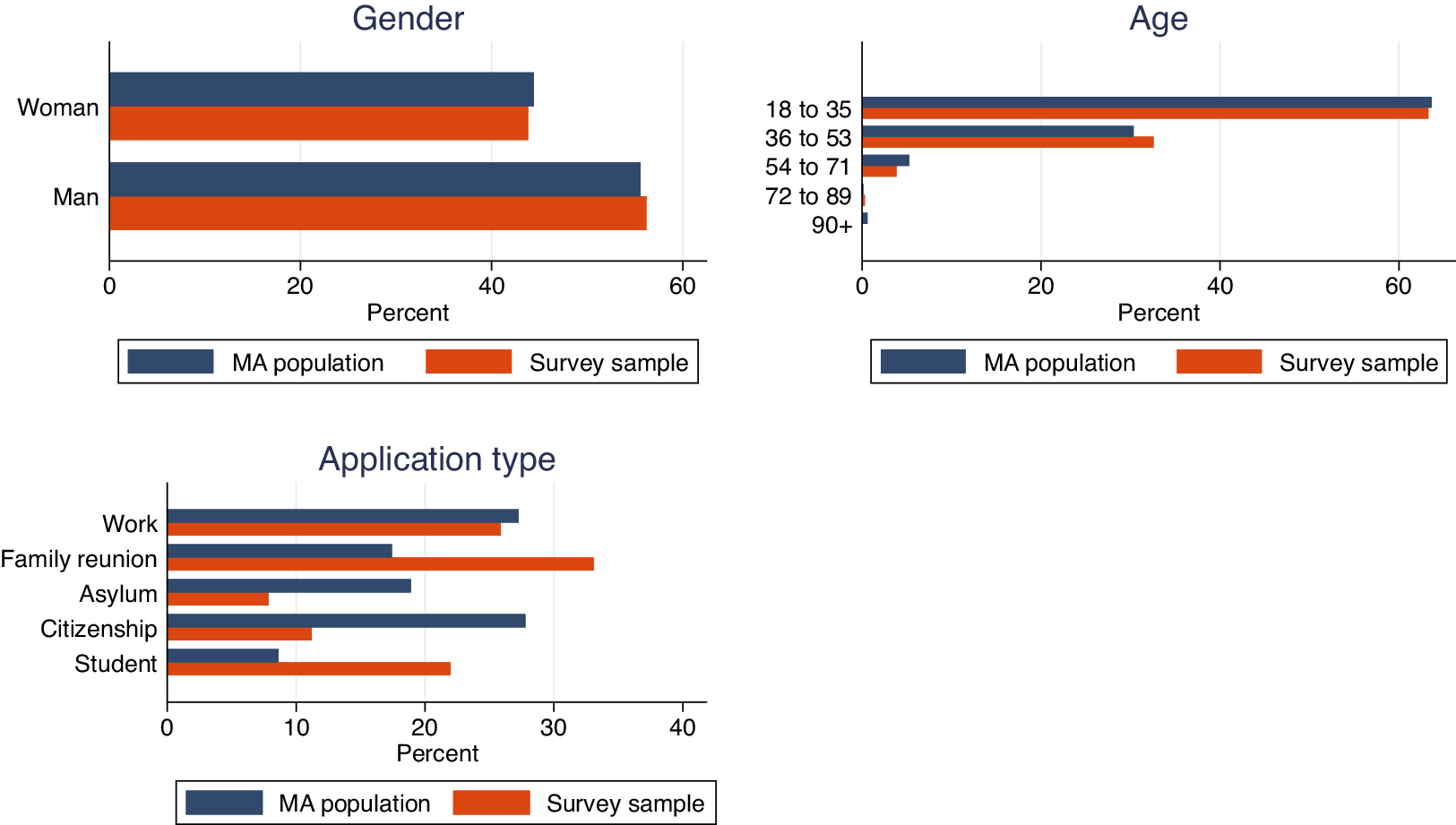

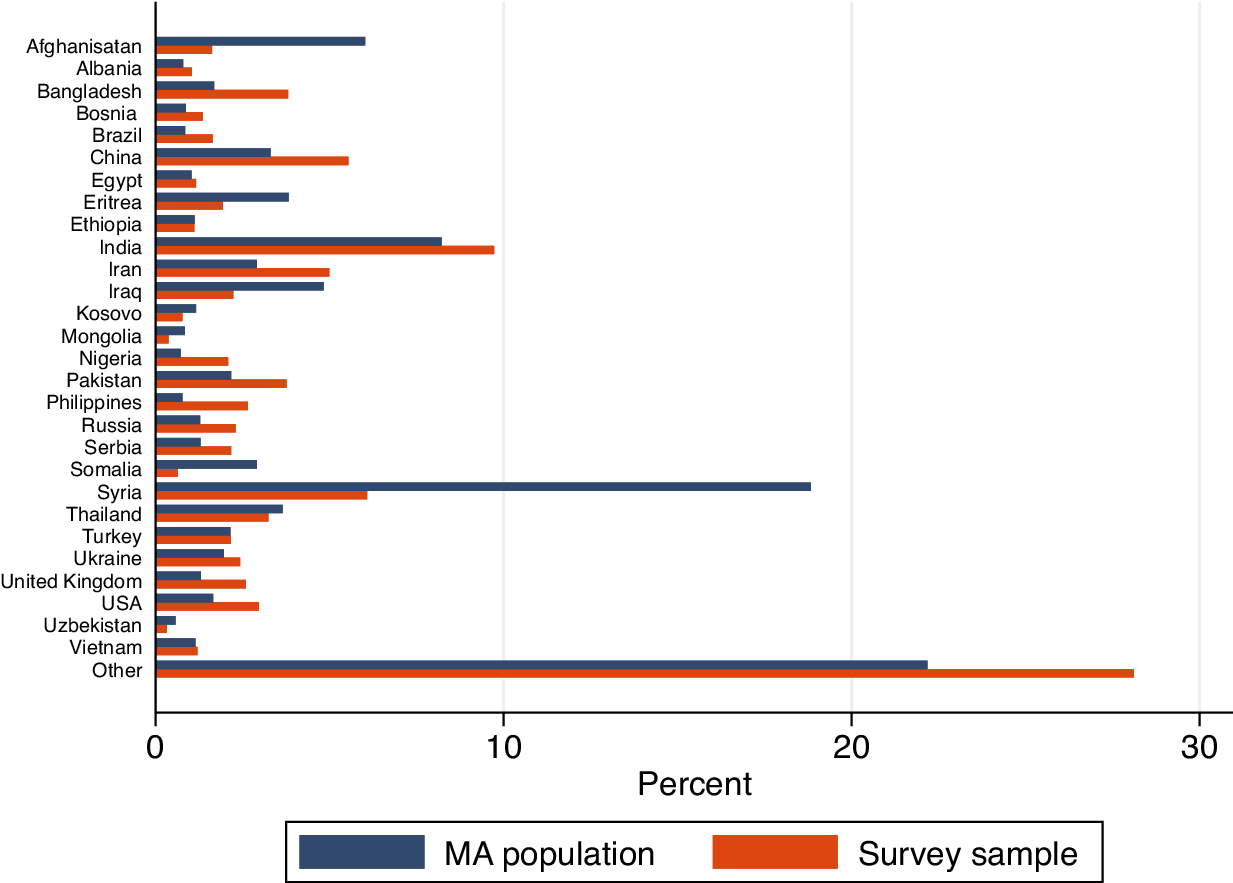

A total of 22,719 people answered the survey, resulting in a response rate of 22.8 per cent and a dataset of 22,674 observations after deleting responses with no answers at all. We deleted 42 observations from respondents younger than 18 years old and three from people over 90. The former were unlikely to apply and submit the applications themselves. The latter reported ages of 158, 229 and 300 years old, which were obviously excluded. Thus, our working sample consists of 22,629 observations. Unfortunately, it was not possible to analyse the non-response bias because there is no access to information about applicants who did not respond to the survey. However, to analyse how the survey sample compares to the targeted population (all migrants who received a decision from the MA between 30 March 2019 and 30 March 2020), we requested data from the MA on the parameters of age, gender, and country of origin.Footnote 1 Figures 2 and 3 present key characteristics of the sample and the data requested from the MA. Overall, our sample matches the target population when it comes to age and gender and mostly matches it for country of origin. We see, however, larger variations between our sample and the target population when it comes to application type. Regarding education, in our sample, most applicants were university-educated, which may point to the fact that respondents with lower education levels may have been more reluctant to participate in the survey.

Figure 2. Overview of the sample and MA population on age, gender and application type.

Figure 3. Overview of the sample and target population country of origin.

These differences have implications for the interpretation of our results. With fewer cases of lower-educated migrants and those applying for asylum and citizenship permits in our sample, the results may be seen as conservative estimates. Conversely, with more cases of highly educated migrants applying for family reunion and student permits in our sample, the results may be overstated and should be interpreted with caution. Despite these limitations, this dataset is, to the best of our knowledge, one of the few large datasets that directly tap into migrants’ digital service use and satisfaction with the MA. Thus, it offers an unprecedented opportunity to fill the gap on migrants and MAs in the literature on digital public services, albeit with the caveats described above.

Variables

Our first dependent variable is the channel via which respondents contacted the MA. Respondents were asked questions concerning their last application to the MA and then asked, “In what way did you apply?” This binary variable consisted of two options: on paper or online.Footnote 2 In our sample, 12.50 per cent communicated using the paper channel, whereas the rest communicated through online services. Thus, one advantage of this variable is its direct measure of whether or not migrant respondents used the digital public services offered by the MA. It allows us to directly juxtapose one traditional form of communication with a digital one. However, it does not allow us to tap into other communication channels, such as letters or telephones. There were 963 observations (equivalent to 4.26 per cent of our working sample) with missing values on this variable.

Our second dependent variable was the respondents’ satisfaction with the MA. We relied on one item asking respondents, “The following statements relate to your experience in contacting the Migration Agency. Do you agree or disagree?” Being in contact with the Migration Agency is a positive experience. For this variable, the available responses were: (1) Strongly disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Agree, (4) Strongly disagree, and (5) I have not contacted the MA. Our preferred item is only a proxy because it focuses on satisfaction with communication with the MA rather than with the MA overall. However, we expect (dis)satisfaction with communication to spill over to (dis)satisfaction with the MA. If respondents are dissatisfied with their communications with the MA, they will most probably be dissatisfied with the MA overall. Thus, we performed a sensitivity test with a second item that aims to tap into this spillover: “The last time I visited the Migration Agency I was pleased with the attitude of the employees when they explained my case” (see Table A1). The second measures satisfaction when respondents visit the MA in person, whereas our preferred item considers respondents’ satisfaction with their communication with the MA more generally. With this variable, we can also examine whether our findings are sensitive to how we specify satisfaction with the MA. For this variable, there were 1,497 observations (equivalent to 6.62 per cent of our working sample) with missing values on this variable.

Explanatory variables

To explain the use of the online or the paper communication channel, our explanatory variables are the respondents’ age, education, and type of application. Age is a continuous variable ranging from 18 to 90 years. Education is a categorical variable: (1) never attended school; (2) 0 to 7 years of school; (3) 8 to 12 years of school; (4) vocational training; (5) university. We combined “never attended school” and “0 to 7” years of school together because the former falls under the latter and has few observations (n = 82). The type of application consisted of five categories: (1) work permit; (2) family reunion; (3) asylum; (4) citizenship; (5) student permit. The age, education, and application type had 478 (2.11 per cent), 1,220 (5.39 per cent), and 9 (0.04 per cent) observations with missing responses, respectively.

To explain satisfaction with the MA, our explanatory variables were the respondents’ contact channel with the MA and their application type (described in the paragraph above). The respondents’ contact channel was operationalised as specified for the first dependent variable.

Controls

For models explaining the respondents’ contact channel with the MA, we controlled for the respondents’ gender and country of origin (see list of country of origin in Table A3). For 6,142 (28.12 per cent) of the observations, their country of origin was unspecified and listed under the category ‘other’. We were unable to retrieve their specific country of origin due to the survey design—but omitting them would result in a very sizable decrease in the sampleFootnote 3—therefore, we opted to include these observations in our sample and retained “other” as one category of this control variable. Gender and country of origin have 724 (3.20 per cent) and 786 (3.47 per cent) observations, with the missing responses respectively shown in brackets.

For models explaining satisfaction with the MA, we controlled for how easily respondents could both locate and understand information on the MA’s webpage. Both variables measure technical characteristics related to the usability of technology, which may affect the respondents’ (users’) satisfaction (see Van Dijk, Reference Van Dijk2020). We also controlled for age, education, gender, and country of origin. For the items on the ease of finding and understanding information, 699 observations (3.09%) and 694 observations (3.07%), respectively, were missing. Summary statistics for all variables are listed in Table A2.

Modelling strategy

We applied logit models and ordinary least squares to estimate the respondents’ contact channel and their satisfaction with the MA, respectively.Footnote 4 We estimated robust standard errors and conducted our analysis in a stepwise manner. For the contact channel, our first model consists of our explanatory variables and our controls. The second model retains the explanatory variable and controls but adds an interaction term composed of age and application type. The third model also retains the explanatory variable and controls but replaces the interaction term specified in the second model with one composed of education and application type.

For satisfaction with the MA, our first model consists of our explanatory variables—age, gender, education, and country of origin. The second model retains the explanatory variable and controls but inserts a variable measuring the ease of finding information. The third model also retains the explanatory variable and controls but adds a variable measuring the ease of understanding this information. The final model likewise retains the explanatory variable and controls but adds an interaction term composed of the respondents’ contact channel and their application type. As specified above, we performed the same analysis with the outcome variable tapping into satisfaction when visiting the MA as a sensitivity test (see results in Table A1).

Results

Channel of communication and contact

Table 2 presents the regression estimates for the respondents’ contact channel. In Model 1—which contains only direct associations between the covariates and the outcome—age, gender, education, and application types have statistically significant associations with the respondents’ contact channel. Older respondents were significantly less likely to use the online channel than the paper channel. Women were significantly less likely to use the online channel than men. When compared with university-educated migrant respondents, those who had spent 0–7 years in school, 8–12 years in school, or vocational training were significantly less likely to use the online channel. When compared with respondents who applied for work permits, those who applied for asylum permits were less likely to use online channels. Conversely, respondents who applied for citizenship or to study were more likely to use online channels.

Table 2. Logit coefficient estimates for paper vs online applications to the MA

Note: Five observations were dropped in Model 3 because there are no observations with the specific combination of family reunion application and an educational background of 0–7 years in school.

* p < 0.05;

** p < 0.01;

*** p < 0.005.

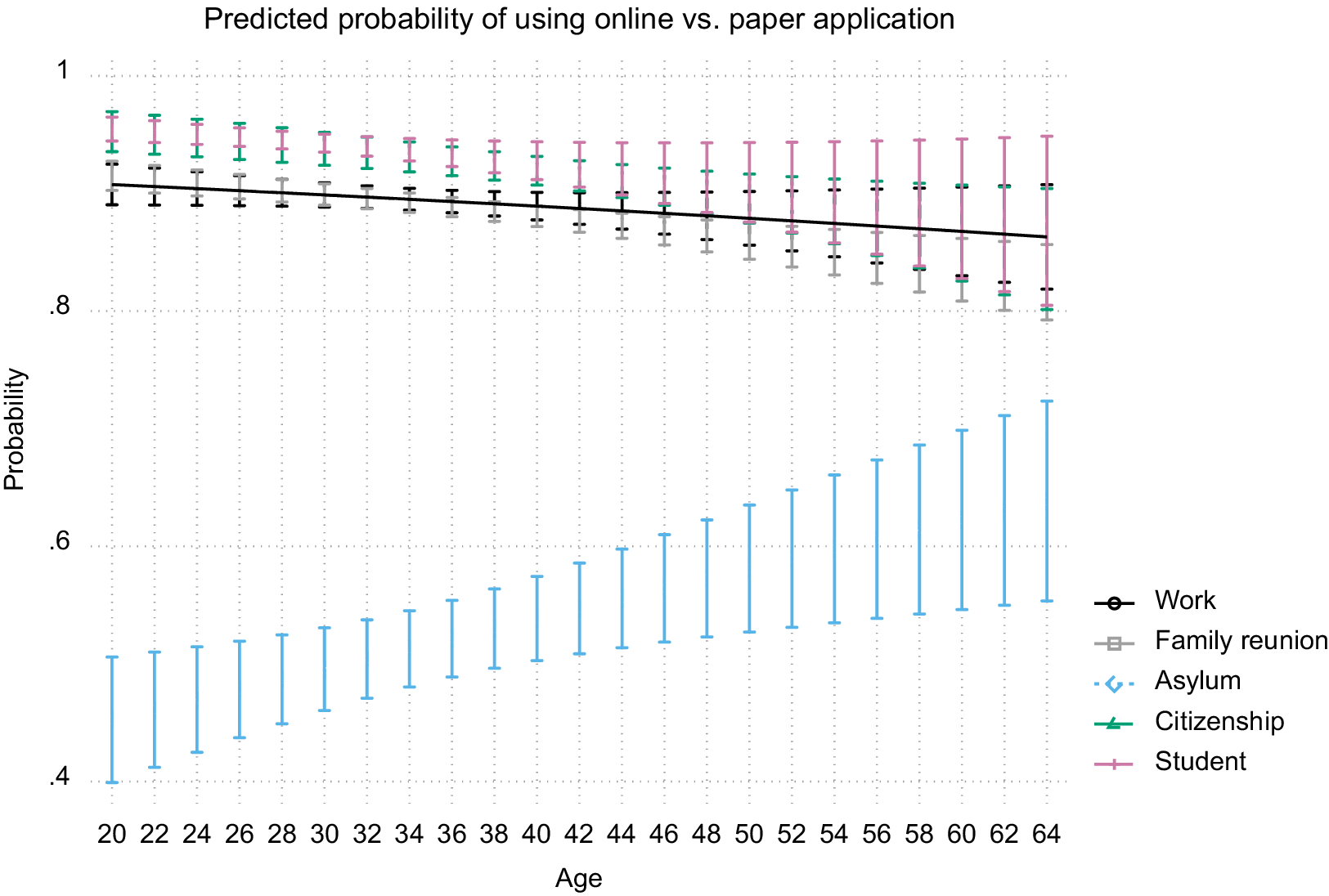

In Model 2, we included an interaction term composed of age and application type. Age no longer has a direct association with respondents’ contact channels. The results for gender, education, and application type (direct associations) remain the same. For ease of interpretation, we present the interaction effects graphically in Figure 4 (see Table A5 for interaction terms). Figure 4 shows that age has a significant association for respondents applying for family reunion, asylum, citizenship, and studying but not work. Older respondents applying for family reunion, citizenship, and studying were all significantly less likely to contact the MA online. Conversely, older respondents applying for asylum were more likely to contact the MA online than by paper means.

Figure 4. Marginal effect of age on probability of using online vs paper application conditional on application type. Notes: Coefficients (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) show a change in the probability of using online vs paper applications for an increase of one year in age for different permit applications.

Figure 5 extends the results illustrated in Figure 4 by revealing the predicted probabilities of using an online rather than a paper application for different permit applications at different ages. Like Figure 4, the estimates for Figure 5 are based on the interaction terms in Model 2. At all ages, asylum-seekers were less likely to apply online than migrants applying for other permits. However, asylum-seekers were about as likely to use paper applications as online applications from the age of 40 onwards.

Figure 5. Predicted probability of using online vs paper application at different ages for different permit applications.Note: Age range represents 1st to 99th percentiles.

In Model 3, we included an interaction term composed of education and the application type. Age had a significant association with the respondents’ contact channel. The results for gender, education, and application type (direct associations) remain the same as before. For ease of interpretation, we present the interaction effects graphically in Figure 6. Overall, differences between the various educational groups with respect to university-educated migrant respondents varied by the type of permit application. Respondents who were less educated than university level were all significantly less likely to use online channels when applying for work permits. For respondents applying for family reunion, only those with 0–7 and 8–12 years of education were significantly less likely to use online channels than the university-educated. For asylum applications, there was no difference in terms of using online channels across education groups. For citizenship, only respondents with 8–12 years of education or with vocational training were less likely to use online channels than the university-educated.

Figure 6. Marginal differences in probability of using online vs paper application across educational groups conditional on application type.

Satisfaction with the migration agency

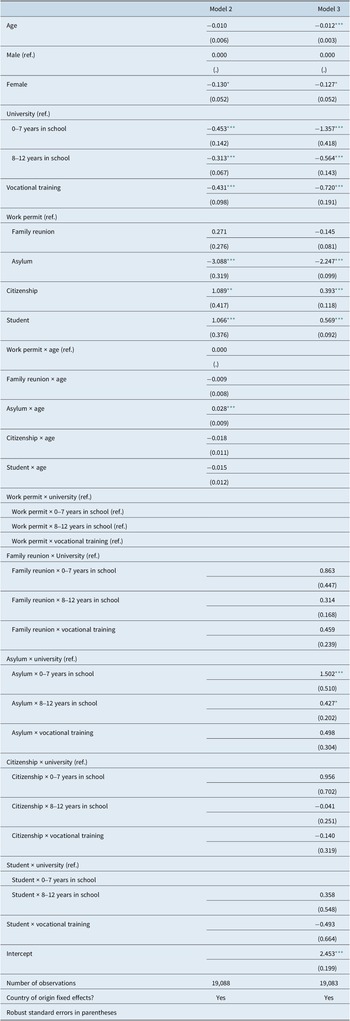

Table 3 presents the regression estimates for respondents’ satisfaction with their contact with the MA. Higher values indicate greater satisfaction with the MA. Model 1 shows that there is no significant difference in satisfaction between migrants who contacted the MA online and those who used paper means. Likewise, education has no significant association with satisfaction. Conversely, age, gender, and work permit are significantly associated with satisfaction. Older migrant respondents are more satisfied with their contact with the MA; women are less satisfied than men. When compared to work permit applicants, respondents who applied for family reunion, citizenship, or asylum were all less satisfied. By contrast, respondents who applied to study were more satisfied with the MA’s contact services than respondents who applied for work permits.

Table 3. OLS estimates of satisfaction with contact with the MA

* p < 0.05;

** p < 0.01;

*** p < 0.005.

Model 2 introduces the ease with which information on the MA webpage can be found. Migrant respondents who found it easier to obtain information in this way were more satisfied than respondents who did not find it easy. Results for the contact channel, age, gender, education and application type remain the same as before.

Model 3 adds the ease with which information on the MA webpage can be understood. Migrant respondents who found it easier to understand the information were more satisfied than respondents who did not find it easy. Again, results for contact channel, age, gender, education, and application type remain the same.

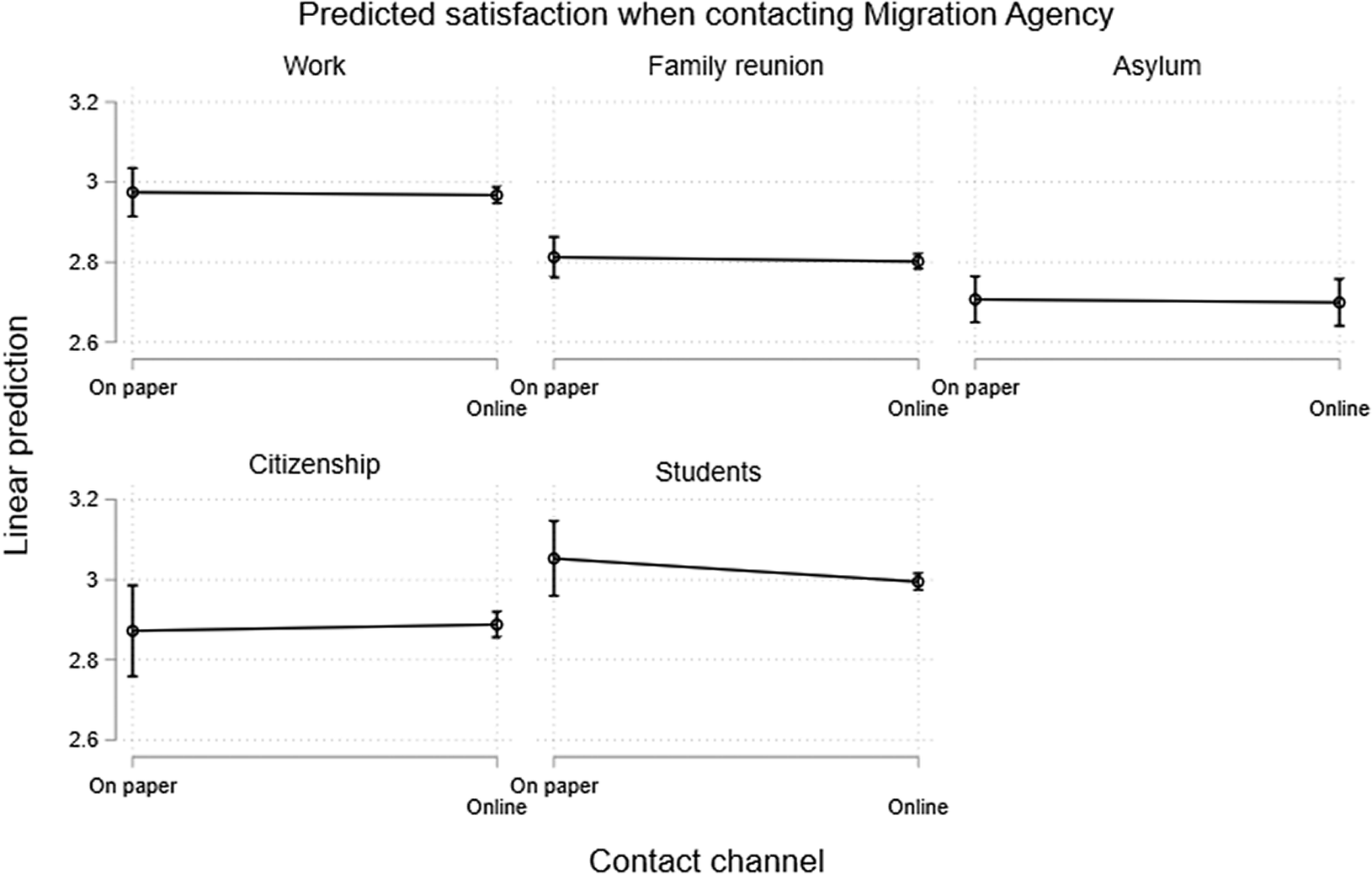

Lastly, Model 4 adds the interaction term composed of the contact channel and application type. As above, the results for age, gender, education, and ease of finding and understanding information do not change. There remains no direct association between the contact channel and satisfaction with the MA contact. There is, however, some change in the direct association for the application type. The significance of the difference in satisfaction between applicants for asylum and citizenship vis-à-vis work permits diminishes (p < 0.005 to p < 0.05). There is no longer a significant difference between applicants for study permits and applicants for work permits. Regarding the interaction terms, Figure 7 plots the results to ease interpretation. Figure 7 clearly shows that satisfaction was the highest among migrant applicants applying for study and work permits and lowest for migrants applying for family reunion and, especially asylum permits.

Figure 7. Predicted level of satisfaction with contact with migration agency.

Discussion

Does the digitalisation of public services—and especially the MA—benefit all migrants equally? Here, we examine whether there might be a bias against certain migrant groups when it comes to the use of digital public services during applications with the Swedish MA. While the existing literature has examined digitalisation in various public organisations and its impact on user satisfaction (e.g. Welch et al., Reference Welch, Hinnant and Moon2005; Schou & Pors, Reference Schou and Pors2019), few studies have focused specifically on MAs or migrant populations. To address this gap, we analysed a unique dataset of 22,674 migrant survey respondents to identify patterns in digital service use and satisfaction across different migrant groups and application types. Hence, this paper contributes by offering a better understanding of a less-studied organisation and user group.

Migrants are considered a “hard-to-reach population” (e.g. Marpsat & Razafindratsima, Reference Marpsat and Razafindratsima2010) in survey research, and prior studies tend to focus either on majority populations (e.g. Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Lundberg and Syltevik2018) or use small qualitative samples (e.g., Safarov, Reference Safarov2023). While our dataset has its limitations (e.g. only migrants with a registered email address were surveyed and there may have been underrepresentation of certain application types), it offers a unique opportunity to directly study a larger sample of migrants that were selected systematically.

Our findings reveal that age is a significant predictor of digital service use. Older migrants are less likely to use online channels for simpler applications like citizenship, possibly due to lower digital literacy and a preference for offline interactions (Van Dijk, Reference Van Dijk2020). Unlike citizens, this age-related stratification among migrants may also arise from a combination of language barriers, other migration-specific inequalities, and lower digital literacy overall (Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Jang, Vaughan and Garcia2020; European Migration Network, 2022). Interestingly, for complex applications such as asylum, older migrants are more likely than younger ones to apply online; however, the probability of both groups applying online is still much lower than for respondents applying for all other permits, regardless of their age. This suggests that age-related stratification in digital public service use also depends on the type of application permit and its complexity.

Turning now to education, more highly educated migrants are more likely to use online services, which is consistent with the general literature on digital public service use among citizens (Van Dijk, Reference Van Dijk2020). However, unlike age, education-related differences are less pronounced across application types. A notable exception is work permit applications, where university-educated respondents are more likely to use digital channels. Overall, these findings show that there is some overlap between demographic predictors for digital public service use among citizens and migrants; however, they underscore the moderating influence of the application permit types.

Our results indicate that migrants’ use of digital services when applying to the MA is not associated with higher overall satisfaction in their interactions with the MA. When higher satisfaction is measured as receiving services in person, digital service use shows a significant positive relationship. This finding suggests that the relationship between digital service use and levels of satisfaction is dependent on what type of service is measured. Notably, this latter result supports findings from the literature focusing on digital usage and satisfaction in public organisations among citizens (e.g. Welch et al., Reference Welch, Hinnant and Moon2005; MacLean & Titah, Reference MacLean and Titah2022). In sum, we posit that closing the gap on migrants’ use of digital tools and its impact on their satisfaction when applying to the MA is a relevant matter. This population has been largely overlooked in studies of the impact of digitalisation in public organisations, yet migrants are often a very vulnerable group in society. When initial digital experiences may impact digital experiences with other public institutions, understanding and improving their digital experience with the MA may yield positive spillover effects for their digital social citizenship.

As MAs across Europe continue to digitise their processes, our results underscore the urgency of addressing inequalities in digital access and satisfaction. Asylum-seekers, in particular, report the lowest levels of satisfaction, suggesting that digitalisation may exacerbate existing vulnerabilities. Their experience with this institution is relevant because it might influence their overall trust in public organisations in the host country, their political participation, and even their relations with the host community (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004; Vigoda-Gadot, Reference Vigoda-Gadot2007; Kramer, Reference Kramer and Uslaner2018). Asylum-seekers are one of the most vulnerable groups among migrants and their already vulnerable status in their host country and conditions for integration might be even further weakened by their limited access to digital public services and service experience with an MA. We argue that including the concept of digital social citizenship into these discussions—emphasising the right to digital public services not only for citizens but also migrants—will help draw attention to the needs of the most vulnerable groups. Beyond our specific case on migrants, the broader social citizenship literature shows that access to services and benefits is already stratified across social groups. Such unequal access can yield undesirable Matthew Effects, which further exacerbate social inequalities. With the digital turn in the application and administration of services and benefits, the inequalities in digital public services surfaced in our study (through the case of migrants) may introduce new or compound existing unequal access in social citizenship. From this perspective, governments should be careful in their design and implementation of digital services to ensure that digital social citizenship addresses rather than worsens existing unequal access to services and benefits.

Overall, our findings underline the need for policymakers to pay attention to inequalities that may arise from digitalisation in MA services in order to avoid undesired knock-on effects on social cohesion. Specifically, we propose that MAs should a) design inclusive digital services that offer simplified navigation to accommodate users with limited digital literacy, b) develop hybrid and more simplified application processes for complex application types, and c) regularly collect user feedback across different groups to adjust service design. To date, we lack sufficient large-N data on migrants’ opinions and views of MAs. If policymakers intend to improve satisfaction with MAs, especially when migrants are seen as service receivers akin to citizens using other types of state services, then having such data would be useful to generate policies and solutions in this direction. We would suggest that the collection of such data also needs to have a “pen and paper” component. If the survey is conducted digitally alone, we will not know the views and opinions of migrants who cannot or lack access to digital technologies. Yet, this is perhaps the exact group whose opinions and views policymakers need to know if they would like to raise the broader accessibility, satisfaction, and usability of the Swedish Migration Agencies’ digital services. Thus, future research could consider conducting both paper-based and computer-assisted surveys, where feasible.

There are four caveats in our paper. The first relates to our data. Although our sample is representative, it is less representative of the country region and application type. People seeking asylum and applying for citizenship are underrepresented in our sample. Additionally, the proportion of respondents who used paper applications is substantially smaller than those who applied online. This is because our sample excludes respondents who did not have registered email addresses, who were perhaps more likely to use paper applications. Future research could thus consider focusing on this group of respondents. Second, our sample consists of fewer less educated migrants and migrants applying for asylum and citizenship permits in comparison to the MA population. Conversely, it consists of more highly educated migrants applying for study and family reunion permits. These differences may bias our findings, leading to conservative estimates for the former group and plausible overstated estimates for the latter group. Our findings take these limitations into account. Third, paper applicants are underrepresented due to the exclusion of individuals without registered email addresses, potentially those most reliant on non-digital channels. Although our sample largely resembles the MA’s population on most characteristics, our findings may underestimate some predictors of digital service use among migrants and the relationship between digital service use and MA satisfaction. Despite these limitations, we know of few other large-scale datasets that offer such rich information on migrants in relation to digital public services and satisfaction with MAs. Fourth, our study focuses on the Swedish MA. However, the digitalisation trends in the Swedish MA are not distinct. MAs in other European countries are also pushing ahead with digitalisation. Thus, we suggest that our findings are still relevant for other European MAs that have similar digitalisation trajectories. Nevertheless, it would be useful for future studies to compare the impact of the digitalisation of applications in different European MAs, as the rules governing the various types of application, and the background of migrants vary across countries.

A. Appendix

As a sensitivity test, we performed the same set of analyses as shown in Table 3 of the manuscript with “Last time I visited the Migration Agency, I was pleased with the attitude of the employees when they explained my case” as the dependent variable. Unlike the main model, we find that applying online significantly predicts satisfaction with a visit to the MA, but the level of significance shrinks after the inclusion ease of finding and understanding information (Models 2 and 3). To facilitate further interpretation, we also plotted linear predictions for the interaction terms in Model 4 as in the manuscript. Figure 3 shows that it yields a similar result as in the manuscript—the association with contact channel and satisfaction when visiting the Migration Agency is not conditional on the application permit type. In sum, the robustness checks support the main findings’ rejection of Hypothesis 2b, but not Hypothesis 2a.

Figure A1. Predicted level of satisfaction with visit with the Migration Agency.

Table A1. Sensitivity test with OLS estimates for satisfaction with visit to MA

Table A2. Summary statistics

Table A3. Countries of origin

Table A5. Full regression model for logit coefficient estimates of using online vs paper applications

Note: See Table 2 in text.