Feminist cause lawyers have made the US courts a major institutional arena for articulating arguments in favor of women’s access to abortion. We examine innovations in women’s-rights legal framing by pro-choice cause lawyers in their Supreme Court party briefs. Concentrating on cases drawing major legal battle lines since Roe v. Wade—cases concerning limits on the use of public funding for abortion, state and local laws imposing multiple restrictions on access, and bans on second-trimester abortions—we investigate how reproductive-rights cause lawyers articulate claims for women’s right to choose abortion and, additionally, how the broader political and legal context shapes framing innovations in this claims-making.

Only a handful of studies investigate pro-choice legal framing to consider how reproductive-rights arguments have developed since Roe. Our investigation builds on this prior research by providing a systematic comparison of reproductive-rights lawyers’ framing across pivotal Supreme Court cases. Through our analysis, we discern important shifts in pro-choice legal argumentation. We then find that these pro-choice framing innovations occur when the political-judicial climate is more resistant to women’s reproductive rights, that is, when the political-judicial opportunity structure is generally closed to the reproductive-rights legal activists. We draw on social-movement and sociolegal literature to theorize the importance of a hostile broader climate in triggering cause-lawyer legal-framing innovations. Although these lawyers may still lose their cases, some of the innovative framing efforts help rein in the scope of abortion restrictions permitted by the Court’s decisions.

PRO-CHOICE CAUSE LAWYERING

Most Supreme Court abortion cases decided in the last half-century involve cause lawyers as legal counsel.Footnote 1 The goal of pro-choice cause lawyers, as for the broader reproductive-rights movement, is to preserve and protect women’s legal right to choose abortion.Footnote 2 Many of these reproductive-rights cause lawyers identify as members of the feminist pro-choice movement (Benshoof Reference Benshoof2003; Albisa Reference Albisa2012). They choose cases not only to represent their clients (patients, physicians, and abortion clinics) but to support reproductive-rights policy in society generally. Most lawyers who litigate abortion cases at the Supreme Court work heavily on reproductive rights and are affiliated with public-interest law groups that specialize in the area, such as the American Civil Liberties Reproductive Freedom Project (RFP), the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR), and Planned Parenthood’s litigation department.Footnote 3

We focus on legal framing by pro-choice cause lawyers because they figure prominently in the history of Supreme Court abortion litigation and because, given their alignment with the broader reproductive-rights movement, we expect that their framing strategy is designed to aid the broader effort to protect women’s legal rights and not just the case-specific interests of their clients.Footnote 4 We consider pro-choice cause lawyers to be institutional social-movement activists. Social-movement scholars (Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg, della Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013) distinguish between institutional and noninstitutional activists, where the latter press their demands largely outside formal institutional structures, such as in public venues using protest tactics. Institutional reproductive-rights legal advocates work within established judicial channels, presenting cases before the courts, and they have been a leading edge in the pro-choice movement in the years since Roe (Gale and Strossen Reference Gale and Strossen1989; O’Connor and Yanus Reference O’Connor and Yanus2007).

While pro-choice cause lawyers play a significant role in efforts to protect women’s reproductive rights, only a handful of studies examine developments in their pro-choice framing, and few such studies seek to understand political and legal circumstances influencing this framing, beyond the characteristics of particular cases (Siegel Reference Siegel1992, Reference Siegel2007; Benshoof Reference Benshoof2011; Smith Reference Smith2011).Footnote 5 Epstein and Kobylka (Reference Epstein and Kobylka1992) provide details on legal arguments in some Supreme Court abortion cases up through the 1989 Webster v. Reproductive Health Services decision, concentrating heavily on Roe and Planned Parenthood v. Danforth and listing pro-choice rationales in Webster and Harris v. McRae. The goal of these authors is not to offer a systematic comparison of pro-choice framing across these cases or to explain why the reproductive-rights lawyers utilize particular frames. Epstein and Kobylka do comment, however, that the pro-choice attorneys’ “arguments [as of Webster, the last case these authors consider] had not changed significantly since 1973.” Additionally, Ziegler (Reference Ziegler2017b) provides a historical analysis tracing use of the undue-burden framework by pro-choice (and pro-life) lawyers, linking its use by abortion-rights advocates to early debates regarding contraception and the Court’s decision particularly in Bellotti v. Baird (1976), an abortion case involving the rights of minors. While Ziegler’s account is detailed, in the end, her analysis follows only one frame through time.

Beyond reproductive rights, scholars have begun to compare legal briefs across cases to understand influences on attorney framing as well as the impact these briefs have on court decisions (Corley Reference Corley2008; Black et al. Reference Black, Hall, Owens and Ringsmuth2016). Such research, however, has not yet considered the impact of the broader political-judicial environment on attorney framing, although Wedeking (Reference Wedeking2010) presents a partial exception. Wedeking examines a sample of just over one hundred Supreme Court cases primarily from the 1980s (thus his analysis is not centered on abortion cases) and finds that petitioners and respondents, as they present their cases to the Supreme Court, align their briefs with the framing in the lower court’s decision. Given that petitioners typically experience loss in the lower court, we might draw a parallel with our investigation, by considering that a loss in the lower court could be a nonreceptive legal environment. Wedeking’s results show that petitioners in their Supreme Court briefs are unlikely to deviate from the lower court’s legal logic. In short, Wedeking’s findings suggest that a hostile legal environment (a lower court loss) reduces innovations in lawyers’ framing, at least innovations defined as framing that is distinct from the lower court’s rationale.

We build on these studies by posing the following questions: When examined systematically across pivotal abortion cases, do pro-choice lawyers’ arguments reveal important innovations? And, if so, in what sort of political and legal context do reproductive-rights framing innovations occur? We focus our examination specifically on arguments in the briefs for a woman’s right to choose abortion. Women’s-rights arguments provide a rich opportunity to examine the contours of pro-choice institutional activists’ frames and how the broader political-legal context can influence such legal framing. To distill when these innovations occur, we utilize a combined qualitative and quantitative approach that allows us to examine the briefs and their framing through a close reading of the text and then to track trends in the frames we uncover using counts of specific words and phrases associated with the frames. We then turn to further qualitative analysis to discuss both the meaning of these frames and the political-judicial context in which women’s-rights framing innovations emerge.

LEGAL FRAMING AND RECEPTIVE AND HOSTILE CONTEXTS

To make sense of the circumstances influencing cause-lawyer framing, we draw on social-movement and sociolegal theorizing regarding framing and political and legal opportunities and threats. Social-movement-framing theorists (Snow et al. Reference Snow and Burke Rochford1986) tell us that a movement frame is an interpretation or understanding offered by movement activists to make meaning of a social circumstance, typically to convey a sense of the social injustice or negative impact of the circumstance in people’s lives and to propose a remedy for the problem. Legal frames, then, are a type of meaning-making where legal language and concepts, case precedents, and legal doctrine are invoked (Pedriana Reference Pedriana2006). Cause lawyers engage in legal framing by utilizing arguments typically both to identify an injustice, often rooting its cause in the harm resulting from existing legal rules, and to formulate a legal solution to the problem, typically some change in the legal rules.

While some scholars (McCammon Reference McCammon2003; Wang and Soule Reference Wang2016) investigate tactical innovations among grassroots social-movement activists, few researchers specifically study movement frame innovation. By frame innovation we refer to activists introducing a relatively new ideational frame into the discursive field in which they operate. Snow et al. (Reference Snow and Burke Rochford1986) define the concept of frame transformation, drawing our attention to the ways in which social-movement actors resist an existing conceptualization and instead put forward an alternative general framework for understanding the social problem at hand. Steinberg (Reference Steinberg1999, 751) speaks of challengers “interject[ing] alternative meanings to articulate their sense of injustice.” The understandings of both Snow et al. and Steinberg are helpful in developing our idea of frame innovation. By legal-framing innovation we mean cause lawyers interjecting new meaning into the legal discourse surrounding abortion rights, along the lines Steinberg describes, both new women’s-rights frames and new ways of using legal rationales to support them. Frame transformation, on the other hand, likely entails a broader framing change than much of what we observe in pro-choice legal framing, as frame transformation often involves a more fundamental redefinition of a social circumstance by supplanting one “primary framework” (Snow et al. Reference Snow and Burke Rochford1986, 474) with another, possibly even substituting one world view with another.

As Snow (Reference Snow2008) and others (Pellow and Brehm Reference Pellow2015) point out, we have limited understanding of the contexts in which movement actors change their framing approaches. Our study investigates the political-legal context in which cause lawyers offer innovative framing in their briefs. Numerous movement scholars theorize opportunities in the broad political environment, often when elite decision-makers are receptive to movement demands (McAdam Reference McAdam1991; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011). As some movement framing studies (Koopmans and Statham Reference Koopmans, Statham, Giugni, McAdam and Tilly1999; Motta Reference Motta2015) suggest, a shift in the discursive context may offer openings for new framing arguments, openings that scholars call “discursive opportunities.” A discursive opportunity for legal-framing innovations can occur when a shift in public or legal discourse introduces new ideational elements that then invite framing innovations in party briefs as lawyers perceive that Supreme Court Justices, given a changed discursive climate, may be open to novel legal arguments that align with the new discursive environment.

While a variety of social-movement studies suggest the importance of opportunity structures, including discursive openings, in shaping activist framing (Noonan Reference Noonan1995; King and Husting Reference King and Husting2003), we expect the opposite. We anticipate that strategic activist pro-choice lawyers will pursue new framing approaches when the broader political and legal climate is hostile, and thus the opportunity structure is largely closed and movement goals are threatened. Legal advocates will innovate in an effort to persuade recalcitrant judicial decision-makers as well as to educate political leaders and the public. Our analysis below suggests that when key political leaders, including Congress, the president, and even state legislatures, signal their opposition to pro-choice movement goals, often as these actors are influenced to do so by pro-life movement activists, and when public opinion may be shifting in this direction as well, the Justices also are likely to become more resistant to pro-choice goals. In some periods, in fact, our results indicate that the composition of the Court changes as an outcome of the shifting broader political environment, and this produces greater oppositional sentiment on the Court. Thus, our analyses suggest that climates more hostile to pro-choice legal arguments develop first in the broader political context and this then increases resistance on the Court.

Social-movement and sociolegal literature supports our hypothesis about resistant contexts leading to framing innovations, although such studies for the most part consider activists other than cause lawyers. Some scholars document the rise of distinct, new movement frames (White Reference White1999), but only a few (Einwohner Reference Einwohner2003; Rohlinger Reference Rohlinger2006) go to the next level and consider how threats in the larger cultural and political environment may cause activists to shift their framing approach. Pellow and Brehm (Reference Pellow2015), for example, document that grassroots environmental activists revise their framing approach in response to emerging environmental crises. Sociolegal scholars (McCann Reference McCann1994; NeJaime Reference NeJaime2011; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2012) consider the impact of hostile legal climates on movement action—when movement advocates experience significant setbacks in the judicial arena—but such studies tend to focus on movement activism more broadly with limited attention to cause-lawyer framing in court cases.

We theorize that when pro-choice cause lawyers confront a hostile political and legal climate, they are more likely to put forward innovative women’s-rights framing that articulates an important, novel pro-choice legal argument in their case briefs. We posit that a hostile climate or a closed political-legal opportunity structure encourages reproductive-rights legal advocates to press their framing more vigorously with innovative arguments. We hypothesize this because cause lawyers are likely to be highly strategic actors, actors who are attentive to and recognize the changed environment and respond to threats by altering their approach in ways they believe likely to produce at least some success. When confronted with a hostile climate, cause lawyers will try new framing in an attempt to persuade resistant Justices, forestall or limit judicial defeat, and possibly, in the process, educate political elites and the public.

Legal framing by attorneys in Supreme Court briefs generally adheres tightly to the norms of this judicial arena, as lawyers draw heavily on constitutional principles, case precedent, and statutory law. As Wuthnow (Reference Wuthnow1989, 13) states, a discursive field, such as a judicial arena, provides its actors with “fundamental categories in which thinking can take place.” Accepted current and past discourses in the judicial arena, evident in relevant legal precedent and existing jurisprudence, typically heavily shape the claims lawyers articulate in their briefs. In providing these ideational categories and materials, the field limits legal actors’ framing to a substantial degree, in that advocates’ frames largely restate existing legal understandings, albeit with important exceptions as we discuss below. Given that Roe, for instance, was decided on the basis of due-process privacy rights, lawyers making later claims for reproductive rights are highly likely to utilize this foundational legal argument (or category) as they assert women’s right to choose.

Although the judicial arena’s norms and expectations constrain them to formulate arguments by drawing on existing legal doctrine, pro-choice cause lawyers also possess a degree of autonomy in generating their claims (Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Snow Reference Snow2008). In writing briefs, strategic attorneys can introduce novel legal claims and rationales. As McCann (Reference McCann1994, 7) states, “legal discourses offer a potentially plastic medium both for refiguring the terms of past settlements … and for expressing aspirations for new terms of entitlement.”

We find that pro-choice cause lawyers generally innovate in two ways. First, they do so by melding pivotal existing legal concepts (such as equal protection or due process) with feminist themes (such as intersectionality or women’s citizenship), drawing new connections between established legal rationales and feminist arguments in an attempt to persuade conservative Justices. Other movement scholars (Maney, Woehrle, and Coy Reference Maney, Woehrle and Coy2005) discuss such hybrid frames in which activists harness established and accepted ideational categories and combine them with novel discursive elements to challenge the status quo. Additionally, Leachman (Reference Leachman2013, 29) helps us see that judicial and movement actors, as they invoke the law, can and often do subscribe to particular ideologies, or “system[s] of meaning.” Pro-choice cause lawyers often espouse a feminist legal ideology, positing that women should control decision making regarding their bodies, including if and when to give birth, and that women should be understood to make thoughtful, rational decisions regarding pregnancy termination based on the social contexts of their lives (Siegel Reference Siegel1992). Reproductive-rights attorneys then engage in innovative framing by invoking feminist themes and combining them with established legal principles.

Second, pro-choice cause lawyers innovate in their framing by using what William Riker (Reference Riker1986) labels “heresthetical” maneuvering in an effort to divide and thus weaken their opponents. Riker defines such framing as a strategy utilized when actors believe they face staunch opposition and a likely defeat, which is the situation the pro-choice legal activists confront in facing hostile, closed political-judicial contexts (see also Wedeking Reference Wedeking2010). In such circumstances, Riker argues, advocates will work to minimize their losses by framing an alternative option, one designed to divide their opponents. Pro-choice lawyers thus frame possible case outcomes in their brief designed to divide conservative Supreme Court Justices (and possibly other political conservatives) by providing an option that may hold appeal for more moderate conservatives and that does not result in a full defeat for the reproductive-rights advocates. In our analysis we illustrate heresthetical maneuvering in more detail with specific examples.

METHODS

To examine how a hostile political-judicial climate may influence legal framing, we examine pro-choice cause-lawyer party briefs in prominent US Supreme Court abortion cases. Given our focus on distilling the cause lawyers’ women’s-rights legal frames, we concentrate our efforts on merits briefs where these frames are developed in detail. Lawyers also present oral arguments before the Supreme Court, but these are short interactive exchanges between the Justices and lawyers with the Justices interrupting and questioning attorneys. Given our focus on distilling cause lawyers’ frames and innovations in those frames, we analyze the written briefs because they present the litigant’s framing more fully. As one judge (Coffin Reference Coffin1994, 107) remarks, the parties’ briefs are the “heavy artillery” of legal cases. In determining which lawyers in the abortion cases are pro-choice cause lawyers, we exclude lawyers who generally practice in other, non-reproductive-rights legal areas. As stated, pro-choice cause lawyers presenting their cases to the Supreme Court focus their work heavily on reproductive rights, often through their work in public-interest reproductive-rights legal organizations.

We analyze three types of abortion cases from the late 1970s to 2007: challenges to limits on public funding for abortion, state- or local-level laws containing multiple restrictions on abortion access, and second-trimester abortion bans. All three of these legal disputes involve key issues in the judicial battles over abortion law (Mezey Reference Mezey2011). For both the multiple-restriction and second-trimester-ban cases, we are able to contrast pro-choice cause-lawyer framing in receptive and hostile political-judicial climates to discern whether important framing innovations occur in the more resistant context, holding case issues relatively constant. The funding cases do not permit such a comparison. As we show, numerous political leaders opposed public funding of abortion during all the funding cases. Given that these cases began shortly after Roe, we contrast pro-choice cause-lawyer framing in Roe, in which the Court ruled in favor of abortion rights, with framing in the public-funding cases, in which the Court resisted allowing use of public benefits for abortion, although the comparison is not as direct as the comparisons for the multi-restriction and second-trimester-ban cases.

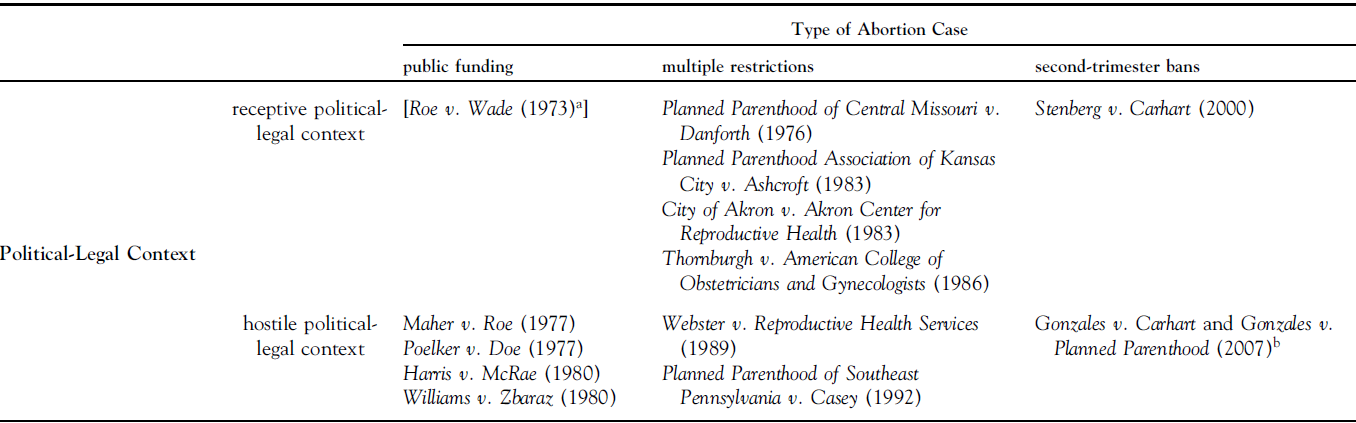

The twelve cases we consider are: (a) public funding: Maher v. Roe (1977), Poelker v. Doe (1977), Harris v. McRae (1980), Williams v. Zbaraz (1980); (b) multi-restrictions: Planned Parenthood v. Danforth (1976), Planned Parenthood v. Ashcroft (1983), Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health (1983), Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (1986), Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989), Planned Parenthood v. Casey; and (c) second-trimester bans: Stenberg v. Carhart (2000), Gonzales v. Carhart and Planned Parenthood (2007) (see also Table 1, which we discuss below).Footnote 6 Our review of Shepard’s Supreme Court citations reveals that these cases are also typically among the most highly cited abortion cases.

Table 1. Supreme Court Abortion Briefs and Their Political-Legal Context

a. Roe v. Wade is not a public-funding case. Given that no public-funding cases were heard in a receptive context, we contrast legal framing in the funding cases with that in Roe.

b. The Supreme Court consolidated Gonzales v. Carhart and Gonzales v. Planned Parenthood, issuing a single decision in the case. We examine the separate pro-choice cause-lawyer briefs submitted to the Court but refer to them as the Gonzales briefs in the text for simplicity.

We next describe the steps of our analysis. The lead author began with close and multiple readings of each pro-choice cause-lawyering party brief (approximately seven to eight readings of each brief) to discern how the brief made its case for women’s abortion rights. In reading the brief, the author first used an inductive approach and open coded claims and rationales for women’s legal right to choose abortion (Strauss and Corbin Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). Through this process of open coding, a set of women’s-rights frames emerged from each brief. This examination of the briefs revealed other types of frames beyond women’s-rights frames, and below in our analysis we briefly discuss these other frames. We focus our analysis, however, on how cause lawyers articulate their claims specifically for women’s rights, that is, why women should possess the right to make decisions regarding their reproduction. For our purposes, we define a cause lawyers’ women’s-rights abortion legal frame as typically having two parts: (a) a claim that women should have a legal right to choose abortion because the lack of this right causes harm to women (e.g., harm to their right to privacy, their citizenship, their health) and (b) a legal rationale offered to support the claim (e.g., due process, equal protection).

After discerning these women’s-rights frames in the briefs, we then assessed the frequency of use of the framing language in the briefs using a quantitative approach. We began by generating lists of words and phrases used in the briefs to articulate the particular women’s-rights frames and their legal rationales. Our list of words and phrases were culled from our close reading of the frames in the briefs, and they appear in the Appendix. We then used text mining relying on R software to conduct our word/phrase counts for each of the abortion briefs. Before conducting the counts, we took preprocessing steps to prepare the briefs for the count analysis. These steps involved: paring down the brief files to exclude lists of cases and authorities at the brief’s beginning and appendices (which often simply list statutes), removing URLs, setting aside proper names that included our search terms, and cleaning and checking the text and analysis to ensure our counts properly dealt with punctuation, capitalization (“African American”, “african american”), brackets (“[a]bortion”), contractions (“can’t”, “cannot”), apostrophes, superscripts, quotations, dashes/hyphens (“self determination”, “self-determination”), and misspellings. We also removed stop words (e.g., “an”, “the”) (Silva and Ribeiro Reference Silva and Ribeiro2003) unless, following Brieger et al.’s (Reference Breiger2018) advice, removing such words importantly altered the meaning (“her future life” v. “future life”). We then utilized R for our count analysis, separating each brief into n-grams ranging in length from one to four words (Caropreso, Matwin, and Sebastiani Reference Caropreso, Matwin, Sebastiani and Chin2001).

In our results below, we present graphs containing the frequency of these counts for each case brief (using a term frequency approach in which we control for the overall word count of the brief). Framing innovations are in part discerned from the graphs by observing distinct shifts across the briefs in frequency of use of particular words/phrases associated with the frames and their legal rationales.

In our third step, we then returned to the briefs, again using a qualitative approach, to examine specific uses and meanings of the framing language to determine whether women’s-rights framing innovations occurred. We thus discern legal-framing innovations using both quantitative and qualitative information. The qualitative examination of the meaning of the words/phrases defining a frame is important. For example, in one brief a keyword used to discern the frame’s presence was also used in the title of a publication frequently referred to the brief and this artificially increased the frequency of use of that frame in the brief. We checked for such artificial uses and removed these from our frequency counts. In moving back and forth between our qualitative and quantitative assessments of the briefs, to carefully examine both the frequency of use and the meaning of the language, we utilize a hybrid methodological approach in text analysis recommended by Breiger, Wagner-Pacifici, and Mohr (Reference Breiger2018). We conceptualize a women’s-rights framing innovation in the briefs as a discernable new emphasis of a women’s-rights legal frame in one or more case briefs, where that frame was not routinely utilized in briefs prior to the new emphasis.

Finally, we situate these framing shifts in their broader political-legal contexts, to examine how the broader environment plays a role in influencing framing innovations. We operationalize a hostile political-legal context as a closed opportunity structure. When prominent political leaders and possibly public opinion as well generally oppose women’s reproductive rights and as a result the majority of Supreme Court Justices also become more resistant, we consider the broad context to be closed to abortion rights for women and thus hostile to pro-choice cause-lawyer framing.Footnote 7

FINDINGS

Table 1 lists the three types of abortion case briefs we consider and the specific legal cases in each of these types. The table also lists whether the cases were heard in a generally receptive or resistant political-legal climate. Our goal is to explore whether in political and judicial contexts where women’s reproductive rights are more strongly opposed—that is, where the opportunity structure is closed—pro-choice cause lawyers are more likely to take innovative steps in their women’s-rights framing.

In our analysis, we focus specifically on women’s-rights legal framing, or frames making a claim for women’s reproductive choice and the legal rationale for this right. The briefs also contain other frames, the most common being what we call “physicians’ rights,” “state interests,” and “balance of judicial and legislative power” frames. The physicians’-rights frame typically asserts the importance of physicians being able to rely on their expert medical judgment. The briefs also discuss the scope of the state’s interest, where the state’s interest in these cases is typically defined as protecting the health of the woman or the potential life of the fetus. Finally, the pro-choice briefs also contain discussions of the balance of power between judicial and legislative action, with pro-choice attorneys often making the case that the judiciary must give limited deference to legislatures as it assesses the constitutionality of legislative enactments. Again, given our focus on women’s-rights framing, we do not consider these frames further.

Our examination of the cause-lawyer party briefs reveals the following women’s-rights frames and their legal rationales (the latter listed below after the colon):

(1) privacy: due process

(2) women’s health: due process, undue burden, and a compelling state interestFootnote 8

(3) intersectionality (typically involving economically marginalized women and sometimes women of color): equal protection, religious freedom, and due process (the last, rarely)

(4) women’s citizenship: due process (primarily) and equal protection (rarely)

(5) evidence-based: undue burden

(6) heresthetical maneuvering (using overturn-Roe and overly broad frames): undue burden (for the overly broad frame)Footnote 9

As we discuss below, use of the intersectionality, women’s-citizenship, evidence-based, and heresthetical-maneuvering frames all reveal framing innovations, in both our quantitative and qualitative analysis. All provide evidence at particular points in time of a distinct upturn in use. The privacy and women’s-health frames, on the other hand, as Figures 1 and 2 respectively show, are used somewhat routinely across all three sets of cases we examine, although there are exceptions.Footnote 10 Figure 1 shows an increase in use of the privacy frame in both the Webster and Casey pro-choice briefs, briefs prepared in a context more resistant to abortion rights. We discuss this increase in use further below. Figure 2 indicates that the Webster brief is also distinct in its low use of the women’s-health frame, which raises the possibility of the absence of a previously routinely used frame as a framing innovation. This is not the operationalization of frame innovation we rely on in our analysis (we consider introductions of new frames), but Rohlinger (Reference Rohlinger2006) suggests paying attention to important silences in framing.

FIGURE 1. Word/Phrase count for the Privacy Frame.

Note: The horizontal axis lists legal cases for the briefs and years in which the case was decided. The vertical axis indicates the count of the words/phrases associated with the frame, divided by the number of words overall in the legal brief. A list of the words/phrases appears in the Appendix.

Black bars = Roe and public-funding cases, light gray bars = multiple-restriction cases, and medium gray bars = second-trimester abortion cases.

FIGURE 2. Word/Phrase count for the Women’s-Health Frame.

Note: The horizontal axis lists legal cases for the briefs and years in which the case was decided. The vertical axis indicates the count of the words/phrases associated with the frame, divided by the number of words overall in the legal brief. A list of the words/phrases appears in the Appendix.

Black bars = Roe and public-funding cases, light gray bars = multiple-restriction cases, and medium gray bars = second-trimester abortion cases.

We now discuss the framing innovations we uncover for the three case types.

Cases Involving Limitations on Public Funding for Abortions

In the 1973 Roe decision, the Supreme Court’s far-reaching ruling legalized abortion in the United States, setting aside numerous state-level laws that generally outlawed abortion. At the time of Roe, the judicial and political climate was generally receptive for abortion rights. While organized opposition to abortion existed (and had for some time (Williams Reference Williams2016)), abortion was not yet the heavily debated and polarizing issue it would soon become, particularly with a mobilized and broader conservative religious-right movement in the late 1970s and then the election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency in 1980 (Greenhouse and Siegel Reference Greenhouse and Siegel2010). The Court’s ruling in Roe extended a due-process right to privacy, building on earlier Court decisions regarding contraceptive use. The Roe Court stated that “the right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision” and the Court’s ruling created a zone of privacy during the first trimester of pregnancy in which the state could not impinge on a woman’s decision to terminate her pregnancy (Roe 1973, 154). The Court held that while this due-process privacy right was a fundamental right, the state retained an ability to regulate access to abortion after the first trimester. In the second trimester, the Court stated, the government had an important interest in regulation to ensure a woman’s health, and in the third trimester, as the fetus became viable, the state had a compelling interest in protecting the fetus.

Within a few years of Roe, the high court heard a series of cases involving use of public assistance, particularly Medicaid payments, to support a woman’s right to choose. The broader political climate, however, quickly became resistant to using public funds for abortion. Abortion opposition was strong among Catholic leaders, and just after Roe Catholic members of Congress would begin introducing bans on public funding for abortion, that scholars (Tribe Reference Tribe1992; Ziegler Reference Ziegler2018; see also Quadagno Reference Quadagno1994) suggest drew additional support from conservative lawmakers and rising opposition to welfare funding for the poor. The growing opposition to public funding would also become evident in that by 1980 Jimmy Carter’s presidential administration opposed use of public assistance for abortion, directing the Solicitor General to argue against such support for women seeking abortion (Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008). Additionally, in the years following Roe, more than a dozen states took steps to limit use of Medicaid funds for abortion (NYU Law Review 1979; Copeland and Law Reference Copeland, Law, Elizabeth and Stephanie2011). In 1976, Congress passed the Hyde Amendment (sponsored by Illinois representative Henry Hyde), which severely limited use of federal funding for abortion (Ziegler Reference Ziegler2015). With this shift in the broader political context, by the late 1970s, in cases concerning use of Medicaid funding and public facilities for abortion, the Roe majority split, with some of the more conservative Justices (Warren Burger, Lewis Powell, and Potter Stewart) now joining Byron White and William Rehnquist in opposing abortion rights.

We consider cause-lawyer women’s-rights legal framing in four public-funding Supreme Court cases in this increasingly hostile climate: Maher v. Roe (1977), Poelker v. Doe (1977), Harris v. McRae (1980), and Williams v. Zbaraz (1980). Each case concerns use of public benefits for abortion among economically marginalized women, those who could least afford the cost of the medical procedure. The Maher case involves a challenge to Connecticut’s policy prohibiting use of state Medicaid funds for first-trimester abortions unless the abortion was deemed medically necessary. The Poelker case differs in that it considers a St. Louis restriction on performing abortions in the city’s public hospitals. Williams assesses an Illinois law restricting state medical-assistance funding for abortion to instances in which a woman’s life was at stake. The plaintiffs in Harris contested the federal Hyde Amendment’s ban on use of federal Medicaid benefits for abortion unless the woman’s life was endangered or the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest. In all four cases, in an increasingly hostile climate toward public funding for abortion, the Supreme Court ruled against the pro-choice lawyers, indicating that public funds and facilities would not be available for the most part to economically marginalized women who chose to terminate their pregnancies.

Legal framing by the pro-choice cause lawyers in the public-funding cases provides evidence of women’s-rights framing innovations occurring in this resistant political-legal context. The attorneys preparing the briefs in these cases represented a growing network of early pro-choice cause lawyers. Most of them were tied to the ACLU, particularly its Reproductive Freedom Project (RFP), which was founded in 1974 to ensure compliance with Roe (RFP 1974). Catherine Roraback, counsel in Maher, served on the ACLU board (Civil Liberties News 2008). Judith Mears, RFP’s first director, assisted Frank Susman with the Poelker brief (RFP 1976b). The Illinois ACLU spearheaded the Williams case, and in Harris, illustrating the strengthening pro-choice coalition, attorneys from RFP (Janet Benshoof), Planned Parenthood (Eve Paul), Center for Constitutional Rights (Rhonda Copelon), along with Sylvia Law and Harriet Pilpel, both of whom had encouraged the ACLU to found the RFP and served on the RFP’s Advisory Board (RFP 1978; Copelon and Law Reference Copeland, Law, Elizabeth and Stephanie2011), combined efforts to challenge the Hyde Amendment.

While these pro-choice attorneys drew on Roe’s due-process privacy framework in their briefs, they engaged in women’s-rights framing innovations in various and related ways. They developed an intersectional pro-choice legal frame centered on the experiences of economically marginalized women and the barriers they confronted in seeking abortions. Figure 3 shows the higher incidence of use of this intersectional frame in Maher, Poelker, Harris, and Williams compared to Roe. As Crenshaw and colleagues (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989; Cho, Crenshaw, and McCall Reference Cho, Crenshaw and McCall2013) tell us, multiple systems of oppression can combine to produce inequality and injustice. For low-income women, restrictions on public funding for abortions would severely limit their right to choose abortion, illustrating the intersection of gender and class dynamics. The combination of gendered patriarchal beliefs motivating the funding restrictions and the fact that the restrictions most impacted those with limited economic resources illustrates how gender and class subjugation can combine to produce an intersectional outcome. As the pro-choice attorneys in Maher argued, with restrictions on Medicaid funding for abortion in place, “a fundamental right is conditioned totally on the ability to pay” (16).

FIGURE 3. Word/Phrase count for the Intersectionality Frame.

Note: The horizontal axis lists legal cases for the briefs and years in which the case was decided. The vertical axis indicates the count of the words/phrases associated with the frame, divided by the number of words overall in the legal brief. A list of the words/phrases appears in the Appendix.

Black bars = Roe and public-funding cases, light gray bars = multiple-restriction cases, and medium gray bars = second-trimester abortion cases.

The primary legal rationales underpinning the intersectionality frame further illustrate innovations in women’s-rights pro-choice framing in the funding cases. In two of the funding cases (Maher and Poelker) the reproductive-rights attorneys emphasized an equal-protection rationale, and in one case (Harris) the lawyers articulated a religious-liberty legal rationale. Figures 4 and 5 respectively highlight the equal-protection and religious-freedom framing innovations in these funding cases.Footnote 11 In Maher and Poelker, the pro-choice advocates emphasized that indigent women seeking abortions were treated differently than other individuals, and this differential treatment, they argued, was a violation of the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause. The Maher and Poelker lawyers offered three comparisons to justify their equal-protection claim. First, Medicaid-eligible women who sought to terminate pregnancies were not treated similarly to others dependent on Medicaid, whose access to other medical procedures was not denied. Second, the cause lawyers compared economically disadvantaged pregnant individuals who chose to give birth and who would receive Medicaid benefits to cover the cost of the birth with those seeking abortion and who would not receive financial assistance for the abortion procedure. This circumstance could effectively compel women in the latter group to give birth, while pregnant women not seeking abortions did not face a similar pressure. Finally, the attorneys contrasted economically marginalized women with financially more secure women. While wealthier individuals would be able to exercise their right to choose abortion because they had the means to afford the procedure, the Medicaid restrictions meant that lower-income women would not be able to exercise their right.

FIGURE 4. Word/Phrase count for the Equal-Protection Frame.

Note: The horizontal axis lists legal cases for the briefs and years in which the case was decided. The vertical axis indicates the count of the words/phrases associated with the frame, divided by the number of words overall in the legal brief. A list of the words/phrases appears in the Appendix.

Black bars = Roe and public-funding cases, light gray bars = multiple-restriction cases, and medium gray bars = second-trimester abortion cases.

FIGURE 5. Word/Phrase count for the Religious-Freedom Frame.

Note: The horizontal axis lists legal cases for the briefs and years in which the case was decided. The vertical axis indicates the count of the words/phrases associated with the frame, divided by the number of words overall in the legal brief. A list of the words/phrases appears in the Appendix.

Black bars = Roe and public-funding cases, light gray bars = multiple-restriction cases, and medium gray bars = second-trimester abortion cases.

As Figure 5 shows, the Harris brief stands out in its use of another women’s-rights legal-rationale framing innovation, use of the religious-freedom frame. This new framing formulation occurred as the context for government funding for abortion became even more hostile, with anti-abortion Court decisions in 1977 in both Maher and Poelkler. This new framing approach was a response to these losses and was an effort to make headway in an increasingly resistant environment. Also, in the 1980 Harris case, signaling the Carter administration’s opposition to use of public funding for abortion, the US Solicitor General defended the Hyde Amendment. The pro-choice Harris attorneys challenged the Hyde Amendment’s limits on Medicaid funding for abortion, invoking the First Amendment’s Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses.Footnote 12 They argued that the Hyde Amendment enacted into law the religious belief that life begins at conception, and such an action violated the Establishment Clause, which bars the government from establishing religion. The attorneys went on to state that by impeding financially disadvantaged women’s ability to follow their own conscience in making decisions regarding pregnancy termination, the Hyde Amendment also violated the Free Exercise Clause, which protects individual religious liberty and the right of individuals to make personal moral choices on the basis of their religious beliefs. In the brief’s wording, the Hyde Amendment “condition[s] entitlement to necessary health care on abandonment of religious and conscientious convictions that abortion is appropriate” (Harris brief 1980, 150). The brief drew on a sociological analysis of the language of supporters of the Hyde Amendment during congressional debates in which lawmakers described the fetus as “being in relation to God” and “having a soul” (86). Some congressional Hyde Amendment supporters also referred to “church teachings to legitimate their positions” and to their own religious affiliations and upbringings as shaping their view of the amendment (87).

In the fourth funding case, Williams v. Zbaraz, the reproductive-rights attorneys again innovated in their legal framing, but in this case the framing innovation was not a women’s-rights frame. The Williams brief attacked the Hyde Amendment by drawing on Title XIX of the Social Security Act. Title XIX, passed in 1965, required that Medicaid-funded medical care “be of high quality and provided in a manner consistent with the best interest of recipients” (Williams brief 1980, 25). The brief argued that Title XIX should outweigh the Hyde Amendment in determining when Medicaid recipients would have access to publicly funded abortion services. While use of the Title XIX legal frame was novel, the framing innovation did not develop a women’s-rights framing theme and although the context was hostile to public funding for abortions, the brief in this case does not provide evidence supporting our assertion about women’s-rights framing innovations in such a context.Footnote 13

As the political-legal climate turned increasingly resistant toward public funding for abortion, the pro-choice cause lawyers deployed innovative women’s-rights legal framing and legal rationales in an effort to persuade the Justices and others that economically disadvantaged women should be able to exercise their right to choose abortion. These ongoing innovations in the increasingly hostile climate provide at least suggestive evidence that framing innovations are linked to the growing resistance in the political-legal context. In the following discussions of the multiple-restriction and second-trimester-ban cases, we find additional evidence that cause-lawyer legal-framing innovations occur in more threatening environments.

Cases Involving Laws with Multiple Restrictions on Abortion Access

Beginning in the late 1970s, the Supreme Court ruled in a number of pivotal cases involving state and local laws that placed restrictions on women’s access to abortion. The restrictions included: mandated waiting periods prior to an abortion, parental consent for minors, spousal consent for married women, and an informed-consent process in which patients must be provided with state-mandated information regarding the abortion procedure (sometimes containing inaccurate information (Daniels et al. Reference Daniels, Janna, Grace and Roberti2016)). While the earlier of these cases took place in a context that was largely receptive for continuing Roe’s general protection of abortion rights, by the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the Court decided Webster and Casey, the environment was far less receptive. Here, we explore new legal-framing strategies that pro-choice cause lawyers developed in the face of this more hostile political and legal environment.Footnote 14

Beginning with the Planned Parenthood v. Danforth ruling in 1976 and including Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health (1983), Planned Parenthood v. Ashcroft (1983), and Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (1986), the Supreme Court handed down a series of decisions that, for the most part, limited the capacity of states and local governments to restrict women’s access to abortion. In both Akron and Thornburgh, the Court held informed-consent requirements unconstitutional. In both instances, the Supreme Court decided that the required information “is designed not to inform the woman’s consent but rather to persuade her to withhold it altogether” (Akron 1983, 444; Thornburgh 1986, 762). In Akron, the Court went on to note that the Akron ordinance specified that physicians must tell their patients that “the unborn child is a human life from the moment of conception,” which the Court stated was simply one view of when life begins, and that “abortion is a particularly dangerous procedure,” an assertion for which supporting evidence did not exist (Akron 1983, 444–45). Through the mid-1980s the Court generally limited the reach of these multi-restriction abortion laws.

By the end of the 1980s, the political context had shifted markedly and the makeup of the Supreme Court reflected the change. In the late 1970s a broad conservative religious-right movement began to emerge, and it included evangelical religious messages about feminist “assaults” on the family (Spruill Reference Spruill2017, 71). The electoral results of this movement were evident in the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan. This new right movement combined with anti-abortion groups, intensifying pro-life efforts (Tribe Reference Tribe1992). Reagan’s election made visible the increasing political polarization around the abortion issue, with legal efforts on both sides gradually becoming more coordinated (Carmines, Gerrity, and Wagner Reference Carmines, Gerrity and Wagner2010; Copeland and Law Reference Copeland, Law, Elizabeth and Stephanie2011). State legislators as well were passing restrictive abortion laws (Congressional Quarterly Almanac 1989). During both the Reagan and first George Bush administrations, the Solicitor General’s office routinely filed amicus briefs in opposition to women’s reproductive rights. By the late 1980s and into the early 1990s, the Reagan and Bush administration appointees to the Supreme Court—including Justices staunchly opposed to abortion rights, in particular, Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas—moved the Court in a decidedly anti-choice direction (Allen Reference Allen1992). In this period of political and judicial conservative ascendency, two multi-restriction abortion cases, Webster and Casey, came before the Supreme Court, and in these cases we see framing innovations by reproductive-rights attorneys.

Pro-choice cause lawyers spearheaded all the multiple-restriction cases from the 1970s through the 1990s, and their organizations overlapped with those litigating the public-funding cases.Footnote 15 As noted in Figure 1, one framing development in the pro-choice briefs in Webster and Casey was an intensification in use of the privacy frame. Our close read of this frame reveals that its meaning in Webster and Casey, with its focus on the right to privacy as articulated in the due-process rationale of Roe, is the same as the privacy frame’s meaning in the earlier Danforth, Akron, Ashcroft, and Thornburgh briefs. Thus, while there is variation in use of the privacy frame, the Webster/Casey increase is an intensification in the frame’s use rather than an innovation in framing. In all likelihood, use of the privacy frame is heightened in the Webster/Casey briefs because of a clear sense among the attorneys that Roe could be overturned in these decisions, and, therefore, the pro-choice lawyers augmented their defense of the privacy right (Wharton and Kolbert Reference Wharton and Kolbert2013).

Two women’s-rights framing innovations, however, do occur in the Webster and Casey pro-choice briefs. The first of these is what we refer to as the women’s-citizenship frame. Figure 6 illustrates the sizeable increase in reliance on this frame in the feminist Webster and Casey briefs. The women’s-citizenship frame stems from a critique of Roe’s due-process framework wherein, for the latter, the right to choose abortion is situated in a doctrine of individual privacy. The privacy doctrine provides women with the right to choose abortion (in Roe’s phrasing, the choice would stem from a woman and her physician), but the right is granted as a negative right. A negative right occurs when, as in Roe, the law limits the government’s ability to impede an individual’s action—in the case of abortion, the government’s ability to burden a woman’s decision to terminate a pregnancy (Ratelle Reference Ratelle2018). A positive right, on the other hand, exists when the government has an obligation to ensure that individuals can exercise the right. The right to choose abortion has not been protected as a positive right under US law, as illustrated in the public-funding cases, where the Supreme Court found no right to government funding for abortion (Bailey Reference Bailey2016). In the 1970s and 1980s, state and municipal governments enacted restrictions on women’s right to choose abortion, typically as a response to proponents in the pro-life movement and their demands that the state offer greater protections for fetuses (Margolis and Neary Reference Margolis and Neary1980). As these restrictions took hold, various commentators (Karst Reference Karst1977; Law Reference Law1984) argued that the Court’s abortion jurisprudence, with its emphasis on privacy and refusal to recognize abortion as a positive right, failed to adequately protect the right to choose abortion.

FIGURE 6. Word/Phrase count for the Women’s-Citizenship Frame.

Note: The horizontal axis lists legal cases for the briefs and years in which the case was decided. The vertical axis indicates the count of the words/phrases associated with the frame, divided by the number of words overall in the legal brief. A list of the words/phrases appears in the Appendix.

Black bars = Roe and public-funding cases, light gray bars = multiple-restriction cases, and medium gray bars = second-trimester abortion cases.

Pro-choice critics of the Roe framework argued that a stronger form of legal protection was needed, specifically an approach where women’s citizenship was fully acknowledged and protected under the law (Siegel Reference Siegel1992; Rose and Hatfield Reference Rose and Hatfield2007).Footnote 16 A women’s-citizenship frame recognizes that women’s control over reproduction is intimately linked to women’s ability to participate in society as full and equal citizens. When women control decision making over reproduction, their ability to pursue education, employment, civic engagement, and community activism and service is substantially enhanced. This can be particularly the case for women from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, young women, and women who confront racial, ethnic, and other social discrimination. Legal protection for reproductive decision making also gives greater social status to women, countering long-standing traditional beliefs that have anchored women in the domestic sphere, devalued their decision-making capacity, and attached stigma when they do decide to terminate pregnancies (Siegel Reference Siegel1992; Reilly Reference Reilly1998; Rose and Hatfield Reference Rose and Hatfield2007). Abortion-rights law that fully recognizes women’s equal citizenship does not permit states to compel women to carry an unwanted pregnancy to term, but rather such law allows women to control reproductive decision making, because such decisions profoundly shape women’s future lives.

The Webster and Casey pro-choice briefs innovated by incorporating women’s-citizenship framing far more than prior feminist reproductive-rights briefs, as Figure 6 illustrates. In Webster, the pro-choice cause lawyers stated that the right to choose abortion has “enabled millions of American women to enter the work force, continue their education, and escape the spectre of illegal abortion or forced pregnancies” (Webster brief 1989, 2). The brief goes on to argue that “decisions with a profound effect on personal identity and destiny be placed largely beyond the reach of government” (2) and must be “in the hands of the person it most affects—the woman” (11). The Casey attorneys also emphasized the women’s-citizenship frame, stating that “[f]ew decisions are more basic to ‘individual dignity and autonomy’ than the right of a woman to choose to terminate or continue a pregnancy” (Casey brief 1992, 15). The brief asserted that “[b]ecause parenthood has a dramatic impact on a woman’s educational prospects, employment opportunities, and self-determination, restrictive abortion laws deprive her of basic control of her life” (26–27). The pro-choice attorneys asked the Court to consider the far-reaching impact of compulsory motherhood for women and to understand that laws restricting abortion serve to fuel women’s economic and social subordination in society (Law Reference Law1984; Siegel Reference Siegel1992). The women’s-citizenship frame bolsters the claim that abortion rights should be a positive right, so that women can attain their full potential and experience equal citizenship.

Even though the women’s-citizenship frame emerged out of criticism of the limits of the due-process framework, the pro-choice legal framing in Webster and Casey continued to link women’s citizenship to women’s right to liberty and privacy in reproductive decision making. The briefs stated that protecting a zone of privacy around women’s right to make the abortion decision would ensure women’s ability to reach their full potential as citizens. Only in the Casey brief are there hints of another legal rationale underpinning the women’s-citizenship frame, one focused on equality rather than privacy. The brief states, “by affording women greater control over their childbearing, Roe has permitted American women to participate more fully and equally in every societal undertaking … and thus [to] continue their education, enter the workforce, and otherwise make meaningful decisions consistent with their own moral choices” (Casey brief 1992, 33). Invoking “equality” here suggests the possibility of situating the women’s-citizenship frame in an equal-protection framework, one where equal treatment of women compared to men is elevated in the legal rationale. This is a legal-rationale innovation for abortion litigation (although one not fully realized in the Casey brief) that a number of legal scholars recommend as providing stronger legal protection for reproductive rights (Siegel Reference Siegel1992).

In addition to the women’s-citizenship frame, the pro-choice attorneys in Webster and Casey innovated in their framing by using an overturn-Roe frame. Their briefs called upon the Court to “squarely call[] the question: ‘[h]as the Supreme Court overruled Roe v. Wade, holding that a woman’s right to choose abortion is a fundamental right protected by the United States Constitution?’” (Wharton and Kolbert Reference Wharton and Kolbert2013, 147). The briefs discussed the consequences for the Court of reversing precedent and “for the first time in its history, withdraw[ing] from constitutional protection a previously recognized fundamental personal liberty” (Webster brief 1989, 3). In Casey, the cause lawyers’ brief stated that “overruling the decision would dislodge settled rights and expectations” that have been in place for two decades (Casey brief 1992, 20).Footnote 17

Riker (Reference Riker1986) refers to such framing as a type of heresthetical maneuvering, maneuvering that can be utilized when actors believe they face likely defeat, which is the situation the pro-choice activists confronted in facing a hostile political-judicial context in Webster and Casey. In engaging in heresthetical framing, the reproductive-rights lawyers attempted to minimize their losses by adding another possibility to the outcomes the Court could choose, specifically, an alternative designed to divide the pro-choice opponents on the Court. That is, the reproductive-rights attorneys anticipated that some of their opponents would fully embrace the new alternative (rejecting Roe) but others would reject it (RFP 1989a, 1989b; Wharton and Kolbert Reference Wharton and Kolbert2013). Riker (Reference Riker1986, 6) refers to this as “splitting the majority,” a particularly apt phrase for the pro-choice attorneys in both Webster and Casey who were attempting to split the Court’s conservative majority. The pro-choice legal advocates used heresthetical framing in what we call an overturn-Roe frame. They did not simply frame their arguments as against the particular abortion restrictions at stake (those in Webster’s Missouri law and Casey’s Pennsylvania law). They took the added step of framing the Court’s decision in each case as a referendum on Roe and a woman’s right to choose abortion generally (RFP 1988). Figure 7 reveals that prior to the Webster and Casey cases, the pro-choice briefs rarely utilized an overturn-Roe frame.

FIGURE 7. Word/Phrase count for the Overturn-Roe Frame.

Note: The horizontal axis lists legal cases for the briefs and years in which the case was decided. The vertical axis indicates the count of the words/phrases associated with the frame, divided by the number of words overall in the legal brief. A list of the words/phrases appears in the Appendix.

Black bars = Roe and public-funding cases, light gray bars = multiple-restriction cases, and medium gray bars = second-trimester abortion cases.

Use of the overturn-Roe frame in Webster and Casey had some success in splitting the majority in that, in the end, not all the conservative Justices wanted fully to dismantle Roe. In Casey, for instance, Justices Anthony Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor, and David Souter, all appointed by pro-life presidents, took a middle-ground, undue-burden approach, which forestalled the other conservative Justices’ willingness to overturn Roe (Greenhouse Reference Greenhouse2005). While the Court in Webster and Casey upheld most of the states’ specific abortion restrictions, it took explicit steps to clarify that it was not overturning Roe. As Benshoof stated, “our legal strategy was successful—dividing the anti-choice judges so they couldn’t agree on how or when to overturn Roe” (RFP 1989a). While the reproductive-rights cause lawyers did not succeed in setting aside the multi-issue abortion restrictions in these cases, they engaged in innovative framing, using a heresthetical maneuver, a framing step that minimized their losses. Moreover, as our results show, these two novel framing efforts, both the women’s-citizenship and overturn-Roe frames, appeared only after the political-judicial context had become more resistant to women’s reproductive rights.

Cases Challenging Second-Trimester Abortion Bans

The Court’s ruling in Casey established a new standard for assessing the constitutionality of restrictive abortion laws: the undue-burden standard. As the Casey Court stated,

The very notion that the State has a substantial interest in potential life leads to the conclusion that not all regulations must be deemed unwarranted. Not all burdens on the right to decide whether to terminate a pregnancy will be undue. In our view, the undue burden standard is the appropriate means of reconciling the State’s interest with the women’s constitutionally protected liberty (Casey 1992, 876).

This was a major shift in the Court’s abortion jurisprudence, away from Roe’s trimester framework and the assumption of privacy in reproductive decision making, especially in the earlier stages of pregnancy. The undue-burden standard elevated the state’s interest in protecting the potential life of the fetus and significantly enhanced the state’s power to regulate abortion throughout pregnancy. Under this new standard, states could regulate abortions before the point of viability as long as the regulation was not an undue burden on a woman’s right to choose abortion, which the Court defined as a regulation that “has the purpose or effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion” (Casey 1992, 877). Going forward, this meant that the courts, attorneys, and legislative bodies would now need to consider what constituted an undue burden.Footnote 18

In Stenberg v. Carhart (2000), Gonzales v. Carhart (2007), and Gonzales v. Planned Parenthood (2007), the Court assessed the constitutionality of laws banning intact dilation and evacuation (D&E), a late-second-trimester abortion procedure. Less than 10 percent of all abortions occur after the first trimester, and the intact D&E method was used in only a small minority of these cases (Guttmacher 2007). Most late-second-trimester abortions involve a nonintact procedure. The intact D&E method, similar to the nonintact D&E procedure, uses dilation and evacuation to abort the fetus, but the intact method leaves the fetus intact to reduce complications (such as infection and sterilization) associated with medical instrumentation in the uterus for at-risk patients. The pro-life movement, however, termed the intact D&E method “partial-birth abortion” in an effort to encourage widespread opposition to the procedure (Gerrity Reference Gerrity, Schaffner and Sellers2010). Use of the word “birth” in the label incorrectly suggested that these late-second-trimester abortions were postviability abortions, which they were not (Smith Reference Smith2008). Some women seek abortions at this later stage when there is a serious malformation of the fetus or the patient’s health or life is in danger (Cha Reference Cha2019).

In Stenberg, with Democratic president Bill Clinton’s appointees Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer now on the Supreme Court, the conservative tilt of the Court during Webster and Casey was lessened. The Court, in a five-to-four decision, ruled that a Nebraska law banning the second-trimester procedure was unconstitutional, because the provision placed an undue burden on the abortion right. By Gonzales, however, the composition of the Court had again shifted, with appointments by Republican president George W. Bush. New Justices Samuel Alito and John Roberts both opposed abortion rights, and Alito in particular had taken a strong stance against Roe while serving as a Department of Justice attorney in the mid-1980s, where he assisted in preparation of the Solicitor General’s amicus briefs against abortion rights (Cooper Reference Cooper1985). The Gonzales case was a challenge to Congress’s 2003 Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act (PBABA), prohibiting use of the divisive second-trimester abortion procedure. The Act reveals the strong political opposition to the abortion method, with numerous state legislatures also banning the procedure (Mezey Reference Mezey2011). Additionally, by the time Gonzales reached the Supreme Court, the pro-life movement’s framing of the issue was well publicized and had succeeded in shifting public opinion. By 2007, nearly three-quarters of those surveyed stated that late-term abortions should be illegal, up from 57 percent holding this view in 1996 (Saad Reference Saad2002, Reference Saad2007).

While pro-choice attorneys in both Stenberg and Gonzales relied on the undue-burden standard as the legal rationale to challenge the second-trimester abortions bans, in the more hostile climate of Gonzales, the cause lawyers pursued two innovations in their women’s-rights framing.Footnote 19 First, they offered framing substantially rooted in empirical evidence, evidence supporting their claim that the federal ban on the second-trimester abortion method created an undue burden on women’s right to choose abortion. As can be seen in Figure 8a, the pro-choice cause lawyers intensified use of an evidence frame by drawing heavily on the language of “evidence” and “facts,” using the evidence-based approach more so than in past cases, including Stenberg. For instance, one of the attorneys’ briefs stated that the law “imposes an unconstitutional burden on a woman’s right to choose whether or not to terminate a pregnancy” arguing “[t]hat evidence, from numerous, highly credentialed physicians practicing in hospitals, academic institutions, and clinics, establishes the intact D&E is a commonly performed and safe procedure” (Gonzales v. Carhart brief 2006, 2, 15). While the evidence-based frame was an intensification of a frame used in prior cases (as can be seen in Figure 8a), a closer look at the evidence frame in Gonzales suggests that there was an innovation in framing as well.

FIGURE 8a. Word/Phrase count for the Evidence Frame.

Note: The horizontal axis lists legal cases for the briefs and years in which the case was decided. The vertical axis indicates the count of the words/phrases associated with the frame, divided by the number of words overall in the legal brief. A list of the words/phrases appears in the Appendix.

Black bars = Roe and public-funding cases, light gray bars = multiple-restriction cases, and medium gray bars = second-trimester abortion cases.

In Gonzales, the pro-choice attorneys emphasized the role of medical evidence, referencing the testimony of physicians and the medical literature about the judgment of doctors regarding the procedure (Figure 8b). They emphasized the medical consensus that the procedure was needed to protect the health of women in particular types of cases, and thus prohibiting its use placed a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman’s right to access a late-second-trimester abortion. That this kind of evidence framing is not present to the same degree in Stenberg suggests that the framing innovation, as an invigoration of a frame with new emphasis on medical judgment, occurred when the overall climate became more hostile.

FIGURE 8b. Word/Phrase count for the Medical-Evidence Frame.

Note: The horizontal axis lists legal cases for the briefs and years in which the case was decided. The vertical axis indicates the count of the words/phrases associated with the frame, divided by the number of words overall in the legal brief. A list of the words/phrases appears in the Appendix.

Black bars = Roe and public-funding cases, light gray bars = multiple-restriction cases, and medium gray bars = second-trimester abortion cases.

In the end, the Supreme Court in Gonzales decided against the pro-choice attorneys, upholding the federal ban, ruling that the law did not impose an undue burden on a woman’s right to abortion. One legal scholar (Borgmann Reference Borgmann2013) indicates that some lower federal courts are now increasingly looking more closely at the factual evidence presented in abortion cases. It may be that the pro-choice evidence-framing strategy in Gonzales, as the attorneys worked to determine useful frames under the new undue-burden standard, encouraged this action within the courts.Footnote 20

A second legal-framing innovation in the pro-choice Gonzales briefs parallels the heresthetical maneuvering used by the cause lawyers in their Webster and Casey briefs in that it emphasized the extreme implications of the opposing side’s argument. The Gonzales briefs framed PBABA as an “overly broad” law, one that proscribed not only intact D&Es but also nonintact D&Es (Smith Reference Smith2008). As one of the briefs argued, “Congress intentionally drew the definition of ‘partial-birth abortion’ to reach beyond intact D&E abortions” and thus “Congress opted to make subject to criminal sanction procedures common to the vast majority of second trimester abortion” (Gonzales v. Carhart brief 2006, 17).

The Gonzales briefs thus put this additional understanding of the PBABA “on the table.” Given that PBABA’s imprecise wording could be utilized by state lawmakers to outlaw all D&E abortions, the lawyers argued that the Court’s decision upholding the prohibition would impinge on a woman’s right to choose abortion by banning late-second-trimester abortions altogether, given that most of these abortions were performed using a D&E procedure (Smith Reference Smith2008). Figure 9 shows the more frequent use of the “overly broad” frame in the Gonzales briefs. This heresthetical maneuvering, as had been done in the Webster and Casey briefs, painted the dispute in Gonzales as one with a possible extreme outcome. In Webster and Casey, the cause lawyers innovated by arguing that Roe itself was at stake; in Gonzales the legal advocates stated that a nearly complete ban on later-second-trimester abortions was possible, and that this overbroad ban placed an undue burden on women’s right to choose abortion. The lawyers’ goal to split the Court’s conservative majority, inviting those Justices less adamantly opposed to abortion to dissent from embracing the PBABA’s broad wording, met with some success. In the Gonzales decision—written by Justice Kennedy, known for being a potential swing voter in the Court’s abortion decisions—the Court explicitly stated that the PBABA does not ban use of the nonintact D&E procedure (Gonzales 2007). The Gonzales decision overall, of course, was not a win for the pro-choice side, in that the Court upheld the ban on the disputed procedure. But, as in Webster and Casey, the Court narrowed its decision, in this case by not allowing the broader restriction on all D&E abortion methods.

FIGURE 9. Word/Phrase count for the Overly Broad Frame.

Note: The horizontal axis lists legal cases for the briefs and years in which the case was decided. The vertical axis indicates the count of the words/phrases associated with the frame, divided by the number of words overall in the legal brief. A list of the words/phrases appears in the Appendix.

Black bars = Roe and public-funding cases, light gray bars = multiple-restriction cases, and medium gray bars = second-trimester abortion cases.

CONCLUSION

Pro-choice cause lawyers litigating before the Supreme Court have been on the front lines of the reproductive-rights battle for nearly half a century. Our study systematically identifies prominent women’s-rights legal frames articulated by these cause lawyers as well as innovations in this framing in pivotal Supreme Court case briefs. We do so not only to examine developments in pro-choice legal framing but to investigate and theorize how the political-judicial climate influences innovations in legal-activist framing.

Our findings indicate that pro-choice cause lawyers in pivotal abortion cases are more likely to engage in women’s-rights framing innovations when they confront a hostile political and legal climate, one where prominent political leaders, the majority of the Justices, and, often, public opinion run contrary to the pro-choice agenda. We find evidence suggesting that closed opportunity structures influence activist legal framing across three sets of important abortion cases: cases involving public funding for abortion, laws placing multiple restrictions on abortion access, and second-trimester abortion bans. While these innovations in framing do not produce legal victories in the instant cases, they likely worked to rein in the scope of the Court’s decisions against women’s right to choose in later multi-restriction and second-trimester-ban cases. Moreover, in all three sets of cases, pro-choice cause lawyers interjected important feminist framing of women’s right to choose abortion into the legal debate over reproductive rights, including arguments involving intersectionality, equal protection, religious freedom, women’s citizenship, and evidence-based framing.

Our research helps us understand how the political and judicial context can influence cause-lawyer framing. Rather than an open opportunity structure fostering legal-framing innovations, our study suggests that important shifts in women’s-rights legal framing occur when the opportunity structure is closed, when the political-judicial environment is hostile to the pro-choice lawyers’ claims-making. Our findings for legal framing align with those of some social-movement scholars (Einwohner Reference Einwohner2003; Pellow and Brehm Reference Pellow2015) who, in investigations of movement activism outside the judicial arena, show that activists revise their framing in response to threats in the broader environment. Our results for cause-lawyer framing innovations also align with sociolegal studies (McCann Reference McCann1994; NeJaime Reference NeJaime2011; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2012) that have not always considered in detail how cause lawyers frame their cases in court but rather consider how hostile legal climates can spur movement activism more generally. Wedeking (Reference Wedeking2010) does consider lawyers’ framing innovations, but only in response to lower court decisions. His work suggests that innovations may not occur in hostile legal environments, at least when a nonreceptive environment is defined as a lower court loss. Our work thus augments and refines this prior social-movement and sociolegal scholarship by theorizing an influential role for broad resistant political-legal environments on cause-lawyer framing innovations.

Our examination of pro-choice cause-lawyer framing since Roe reveals a variety of women’s-rights legal-framing innovations. We note use of hybrid framing strategies, in which existing legal rationales are combined with novel feminist claims. For instance, in the public-funding cases the advocacy attorneys introduced an intersectional feminist frame to point to the funding restrictions’ impacts on economically marginalized women. These legal activists drew on equal protection and religious-liberty jurisprudence to provide legal rationales to support their intersectional claims, producing legal-frame blending in which women’s-rights intersectional claims are melded with existing legal doctrine. In addition, our research uncovers that, in both the multi-restriction and second-trimester-ban cases, a threatening climate led the legal advocates to innovate utilizing a heresthetical framing strategy (Riker Reference Riker1986). The pro-choice cause lawyers presented the Court with a possible extreme outcome in the case, such as the Court deciding to fully overturn Roe in the Webster and Casey briefs, in an effort to divide the Court’s conservative majority. The attorneys’ assumption was that not all the conservative Justices would support the extreme outcome, and this proved to be the case. In both Webster and Casey, the heresthetical maneuver resulted in the Court affirming Roe as legal precedent.