Introduction

The European crises of 2008–2022 have created conflicts but may have also spurred polity building at the European Union (EU) level by increasing solidarity and strengthening common identities. If on the one hand, crises can tilt the playing field of EU member states by posing asymmetric problem pressures and creating divergent policy preferences, they can also constitute windows of opportunity for further strengthening the EU polity by activating solidarity mechanisms between people and countries. Such mechanisms can be dubbed ‘bonding’ mechanisms (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005; Ferrera, Reference Ferrera2005; Flora et al., Reference Flora, Kuhnle and Urwin1999): they ‘bond’ the European polity together and create a ‘we‐space’ (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera2023) through increased willingness to help, social risk sharing and eventually a more pronounced shared identity. Arguably, such bonding mechanisms happened on the supply side of European politics during COVID‐19. After many acrimonious exchanges in March 2020, European leaders bonded together to create a complex and previously unthinkable policy response called NextGenerationEU (NGEU). Policymakers stressed the common identity and ‘community of fate’ (to use the words of Angela Merkel – in Ferrera et al., Reference Ferrera, Miró and Ronchi2021, p. 1346) to resolve deep conflicts over crisis solutions. This bonding of policymakers on the supply side of politics has been analysed extensively in the literature (Ferrera et al., Reference Ferrera, Miró and Ronchi2021; Schelkle, Reference Schelkle2021; Truchlewski et al., Reference Truchlewski, Schelkle and Ganderson2021; Truchlewski & Schelkle, Reference Truchlewski and Schelkle2022).

By contrast, we aim to explore the relationship between the perceptions of a ‘we‐space’ (a shared identity, ‘bounding’) and support for solidarity in Europe (‘bonding’) on the demand side of politics, that is, among European publics. Was European solidarity during COVID‐19 ‘bounded’ in the Hirschmanian–Rokkanian sense that boundaries create higher solidarity for in‐group members than for out‐group members? This question has important implications for EU polity building. If European solidarity has a territorial basis, rather than being cosmopolitan and universal, this could further facilitate institution building, burden sharing or debt financing, all implying a shared political destiny. By analysing the politics of bounding–bonding on the demand side, we contribute to a burgeoning literature measuring levels of European solidarity in general (Lahusen & Grasso, Reference Lahusen, Grasso, Lahusen and Grasso2018, Gerhards et al., Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019) but also enquiring about its levels and determinants during the COVID‐19 crisis in particular (Bauhr & Charron, Reference Bauhr and Charron2023; Katsanidou et al., Reference Katsanidou, Reinl and Eder2022).

We expand this theoretical and empirical agenda in several ways. First, we argue that European solidarity is bounded and differentiates between EU insiders and outsiders. We test this by empirically benchmarking our measures of solidarity to a non‐EU member. This is important because studies analysing European solidarity rarely use a non‐EU benchmark, and thus we rarely know whether increasing solidarity in Europe is destined for other Europeans (‘bounded solidarity’) or whether this is a universal and cosmopolitan feeling (‘cumulative solidarity’ – the more solidaristic I am with you, the more solidaristic I am also likely to be with a foreigner; Kiess et al., Reference Kiess, Lahusen, Zschache, Lahusen and Grasso2018). Different political bases for the cumulative and bounded solidarity imply different bases for institutional development: while the former is universalistic, the latter is based on a feeling of shared political destiny. Furthermore, once this logic of bounded solidarity takes hold, it begs the question of knowing whether the ‘bounding–bonding’ mechanism is homogeneous or heterogeneous (i.e., it applies to citizens across all member states and socio‐political groups, or only to some). A heterogeneous ‘bounding–bonding’ mechanism can result in ‘circles of bonding’: while all citizens agree that they should be more solidaristic with European peers than with non‐European ones, it can be that they are more solidaristic with some countries than others within the EU.

Second, we argue that if this ‘bounding–bonding’ mechanism materializes, the nature of such bonded solidarity can also have deep implications for building the European polity, through the channels (EU level vs. member state level), policy dimensions of the crisis (health vs. economy) and instruments (loans, grants, medical equipment, vaccines) of solidarity. Contrary to bilateral, one‐off aid, solidarity transmitted through the EU channel is likely to strengthen the EU polity via institution building and a socialization of European publics and elites around common goals. This could further contribute to the elaboration of a solidaristic ‘we‐space’ in a positive feedback loop. Next, we enquire whether bonding varies across the policy dimensions of the COVID‐19 crisis (health vs. economic) because they can have different implications for polity building through the bounding–bonding mechanism. If solidarity happens only on the health aspect of the crisis – what characterizes most the COVID‐19 crisis and is a less common scenario compared to the economic aspect – then solidarity is more likely to remain temporary/exceptional. If solidarity is high and bounded on the economic dimension, it may imply a long‐term willingness to deal with deeper, structural problems and creates a precedent for future crises on the economic dimension. Finally, we explore differences in solidarity when it comes to instruments within each policy domain. Within the economic domain, we take into account differences in preferences for repayable versus non‐repayable instruments (loans vs. grants) that have been previously appointed as important in the literature (Cicchi et al., Reference Cicchi, Genschel, Hemerijck and Nasr2020) and were hotly debated during the 5 months that led to the NGEU package (de la Porte & Jensen, Reference de la Porte and Jensen2021). Within the health domain, we explore preferences for aid in the form of medical equipment and vaccines.

Using an original vignette survey experiment collected in December 2021 in eight European countries, we find that, except for respondents in Italy, solidarity in most countries is bounded (though we find a strong effect size heterogeneity). We show that whatever the measure, the recipient, or giver, Spain and Italy are most likely to be solidaristic, while Sweden, the Netherlands, and France are the least likely. Germans are more solidaristic than their government appears to be, which gives the German government some room for manoeuvre in EU negotiations. We also find that circles of bonding emerge within Europe: there is a significant interaction between the respondent's country and the country receiving help. An inner circle including France, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden mostly want to help themselves and Southern member states, but not the Central European members. Our evidence shows that this division is likely driven by the Rule of Law debate and Poland and Hungary's obstructionist European politics. When enquiring into the type of help Europeans want, medical help is preferred to economic help. On the economic side, respondents preferred loans, rather than grants. Finally, we ask at which level should bonding take place: respondents usually prefer the European level to national bilateral solidarity. While our evidence suggested that a freeriding mechanism might be behind this preference, we consider this result still optimistic insofar as EU‐level solutions are widely accepted. In summary, we find that EU citizens do form a distinct community of solidarity which, in line with a Rokkanian understanding of polity formation, plays a key role in political development and consolidation.Footnote 1

This article proceeds as follows. First, we theoretically develop the idea of European solidarity resting on the nexus of bounding and bonding and propose hypotheses based on the insider–outsider heuristic but also regarding preferences across policy fields and regarding ways of implementing help. Second, we explain our experimental approach and describe the data we gathered. The third section discusses our results, while the fourth one concludes by drawing the implications for European solidarity politics and institutional building in times of crisis.

Bounding–bonding: Insider/outsider demarcation and European solidarity during COVID‐19

Numerous studies on the determinants of European solidarity followed in the wake of the polycrisis (Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Kuhn, Meijers and Nicoli2021; Cicchi et al., Reference Cicchi, Genschel, Hemerijck and Nasr2020; Ferrera, Reference Ferrera2023; Pellegata & Visconti, Reference Pellegata and Visconti2021) indicating that Europeans do tend to be generally more solidaristic in times of crisis. We argue, however, that while this effort is welcome, it is important to elaborate and empirically examine the various conceptual dimensions falling under the umbrella term of solidarity. Sangiovanni (Reference Sangiovanni2015) offers a useful triptych to summarize various definitions of solidarity as shared experience, shared action and shared identity. Our definition of solidarity tends towards the latter: in Sangiovanni's words, ‘solidarity is anchored in shared identification with an ‘imagined community’ where membership is defined not in terms of class, or social position, or family, or joint action or struggle, but in terms of an underlying identity, often based on ethnicity, language, and/or social “origin”’ (p. 342). It also comes close to Bayertz's (Reference Bayertz1999) second definition of solidarity (‘solidarity as the inner cement holding together a society’, p. 9) and T.H. Marshall's remark that solidarity rests on ‘a direct sense of community membership based on loyalty to a civilization that is a common possession’ (Reference Marshall1950, p. 96). This approach has been further developed theoretically and empirically in recent studies (Harell et al., Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2022; Kymlicka, Reference Kymlicka2015). The ‘we‐ness’ at the basis of Kymlicka's definition of solidarity is the precondition for inclusive solidarity mechanisms in diverse societies – a description that is particularly fitting for the European polity – which once implemented, strengthens the ties that bind further, thus being a strong basis for institution building (Banting & Kymlicka, Reference Banting and Kymlicka2017). Bounded solidarity is, thus, different from charity and altruism: neither presupposes a shared identity. This is the approach of Komter (Reference Komter2004) for whom – in the tradition of Mauss and Durkheim – solidarity is defined through gift, that is, a first step that creates a mutual obligation. There is nothing ‘bounded’ in this definition in the sense that Komter's definition implies that anyone could receive a gift. This is a kind of disinterested altruism which we labelled charity or cumulative solidarity throughout the rest of the article on the basis of Table 1. There are of course criteria of deservingness (Heermann et al., Reference Heermann, Koos and Leuffen2023; van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2006), and we look at how some actors may not be deserving of being included in the ‘we‐ness’ of the European polity: some obstructionist countries undermining the European polity by not respecting its rules (e.g., Poland and Hungary in our sample).

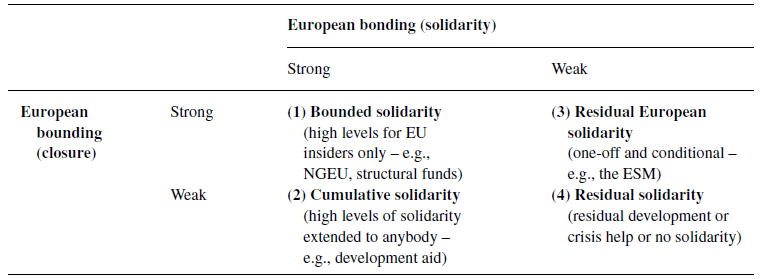

Table 1. The bounding–bonding nexus in the emerging European polity

Abbreviations: EU, European Union; NGEU, NextGenerationEU; ESM, European Stability Mechanism.

We argue that solidarity can be preferential and that some countries may be more favoured than others as recipients of solidarity. The question is how EU citizens would like European solidarity to be implemented at the macro‐level: Should the emerging European solidarity regime distinguish between EU and non‐EU members? Or should it rather keep a universal nature where any country in crisis deserves equal solidarity? Recent literature has underlined that identity plays a big role in European solidarity (Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2020) and that more identity‐based solidarity may ‘re‐border’ Europe and strengthen the willingness of individuals to contribute to the public good, which constitutes a strong basis for institutional building (Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2021).

Our argument is that while many studies seek to estimate how much solidarity there is in Europe, they also do not always provide a benchmark (for exceptions, see: Gerhards et al., Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019; Heermann et al., Reference Heermann, Koos and Leuffen2023); how much solidarity is there in the EU, compared to countries outside the Union? Is this solidarity catered to particular (clubs of) member states? Without knowing this, we can never be sure of whether European solidarity is universal or targeted at European insiders and thus qualitatively different for the EU polity. The findings of the literature so far are mixed: while Gerhards et al. (Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019) show that fiscal solidarity during crises is more pronounced for other European than for non‐EU countries (using a survey encompassing 13 countries), Heermann et al. (Reference Heermann, Koos and Leuffen2023) find that this difference is not so pronounced (however, their sample is restricted to Germany). Others find that solidarity is more pronounced at the national and universal levels, but weakest at the European level (Lahusen & Grasso, Reference Lahusen, Grasso, Lahusen and Grasso2018). These findings are complemented by a broad literature on the determinants of foreign aid which suggests that interests and cosmopolitanism play a major role (Prather, Reference Prather2020). We aim to bring further empirical evidence to this debate.

Even if European solidarity is bounded, its level and nature can vary greatly. First, similar identities and proximity can drive this differentiation. Cicchi et al. (Reference Cicchi, Genschel, Hemerijck and Nasr2020) provide descriptive survey evidence on regional European solidarity: respondents are mostly willing to help their neighbours. Other studies confirm this finding and stress the role of past crises in shaping solidarity (Afonso & Negash, Reference Afonso and Negash2023; Reinl et al., Reference Reinl, Eder and Katsanidou2022). Second, ‘partial exits’ can severely erode solidarity: if some actors undermine common norms but continue to benefit from EU public goods, they are perceived as free riders (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005, pp. 7−10; Fenger, Reference Fenger2009). Europeans might be less solidaristic with countries which are seen as obstructionist and not playing by the rules, such as those involved in the current Rule of Law crisis and the upheaval about the conditionality of NGEU (Hungary and Poland). Therefore, solidarity in Europe can be bounded from without (differentiating EU and non‐EU members) and from within (differentiating between compliers and non‐compliers of the EU polity).

Table 1 offers an overview of the analytical space that is opened by our two concepts: ‘bounding’ – that is, the differentiation between outsiders and insiders when crossed with the concept of ‘bonding’ on the EU polity yields four types of European solidarity.

The first quadrant defines ‘bounded’ solidarity: high solidarity is only geared towards members of a spatially bounded space, the European one in our case. Should a crisis happen, insiders will help each other out more than outsiders. Bounded solidarity has deep political implications for polity building. For instance, national welfare states are built on such a type of bounded solidarity, differentiating between citizens and non‐citizens, those who have rights and those who do not. For a polity, this is a powerful loyalty mechanism that ‘bonds’ a society together and can sustain institution building through the legitimacy that bounded solidarity confers. Bonding with closure (bounding) is like loyalty without exit: it creates pressure for a common voice on common solidarity and thus participates in the strengthening of a multilevel polity. By contrast, the second type of solidarity, cumulative solidarity, is ‘universal’ in the sense that givers do not differentiate between the receivers of such solidarity: countries inside or outside the EU can benefit equally in hard times from generous solidarity mechanisms. Since solidarity does not depend on membership, there are no incentives to join or stay in the group, which implies a weak loyalty mechanism and undermines voice. The ties that bind are weaker in this case and generate little loyalty/legitimacy for the European polity. An example could be if the EU offered structural or NGEU funds to countries from the neighbourhood policy (e.g., Moldova, Ukraine, Tunisia): such high solidarity mechanisms would not be based on bounded membership but on belonging to a wider, more diffuse territorial basis (e.g., De Gaulle's Europe from the ‘Atlantic to the Urals’). The third quadrant of solidarity combines weak European bonding and strong bounding: this weak European solidarity is perhaps best epitomized by the European stability mechanism, which was bounded to EU members but was weak in terms of bonding. Such solidarity happens rarely, perhaps only during crises that justify one‐off help between member states because they are beyond the control of member states (Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2020; Ferrara et al., Reference Ferrara, Schelkle and Truchlewski2023) or to prevent spillover effects like in the Euro Area crisis and to insure tail risks of economic integration (Schelkle, Reference Schelkle, Adamski, Amtenbrink and Haan2022). If citizens prefer such solidarity, loyalty mechanisms are weak at the EU level and thus do not constitute a firm basis for polity building. For instance, Italy was extremely reluctant to use the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) during COVID‐19 because it could spur Euroscepticism (Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Bremer and Neimanns2021). Finally, in the fourth quadrant, we have weak European bonding and bounding: residual solidarity is akin to charity, a small and occasional help which is not offered on a continuous basis like cumulative solidarity. Europeans might show solidarity to each other and outsider countries depending on needs and occasionally, but this type of solidarity is not conducive to polity building. While for reasons of simplicity we put these ideal types into a table, they can also be seen as a continuum which goes from the most bounded and most solidaristic type of solidarity to the least bounded and least solidaristic regime the EU could have.

Given that the Rokkanian polity perspective of the EU does not have precise empirical expectations as a system‐level theory that is amenable to hypothesis testing, our attempt to bring this down to the empirical, individual level follows the spirit of a theory‐building exercise, rather than that of precise testing. Nevertheless, as shown below, we do guide our empirical choices by a wide body of literature on solidarity and polity building and, consequently, we elaborate a series of considerations and expectations to guide our data analysis in terms of the factors included in the analyses and their potential effects. We argue that an external ‘benchmark’ that helps us differentiate between cumulative and bounded solidarity has deep implications for European solidarity. For reasons of tractability and because we are focused on European solidarity, we focus on a third country not belonging to the EU, Peru, for two reasons. First, in terms of proximity, it was important to select a country that was distant enough not to trigger specific solidaristic dynamics that might differ widely across the countries in our sample. We wanted to avoid countries to which specific member states might have strong bonds such as those neighbouring the EU (e.g., Central European countries being more solidaristic with countries in the EU's eastern neighbourhood due to proximity). Second, in terms of crisis performance, given that our study is focused on solidarity during the COVID‐19 crisis, it was also important to avoid countries that were featured heavily in the media as examples of their crisis (mis‐)management in order not to introduce unwarranted deservingness dynamics or that had prominent populist governments at their helm (e.g., Brazil for mismanagement or South Korea for good management).

Bounding the bonds, the creation of a ‘we‐space’ and cross‐national constellations

The ‘bounding–bonding’ dynamic has already been investigated before the COVID‐19 crisis, with the literature asking whether European solidarity is ‘cumulative’ or ‘bounded’. For instance, Gerhards et al. (Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019) investigate European solidarity systematically across four domains: fiscal (i.e., willingness to support indebted countries), welfare (i.e., willingness to support weaker EU citizens irrespective of their residence), territorial (i.e., willingness to reduce inequalities between rich and poor countries) and refugees (i.e., willingness to grant asylum and willingness to support burden‐sharing within the EU). For each of these dimensions, the authors probe whether European solidarity goes beyond the national ‘containers’ and whether the EU is ‘a specific space of solidarity distinguishable from both global and national solidarity’ (p. 4). In pre‐COVID‐19 times (their data were fielded in 2016), one would have expected that, after the mismanaged Euro Area crisis, preferences for European bonding would be weak and certainly weakly bounded, especially amongst respondents of creditor countries. Surprisingly, they find that, more often than not, solidarity is indeed more bounded at the EU level. For instance, European fiscal, territorial and welfare solidarity is higher than for non‐EU members. Gerhards et al. summarize their findings by saying that ‘Europe is thus undoubtedly a distinct space of solidarity’ (Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019, p. 6) compared to non‐EU countries and is increasingly overlapping with the national space of solidarity (little differences across the dimensions). They find the national and European spaces of solidarity are not seen as competing with each other, but rather as being complementary: European solidarity can be seen as a compensation for the weaknesses of national solidarity. To echo Alan Milward, European solidarity is a rescue of national solidarity (Milward, Reference Milward2000), a kind of reinsurance of national insurance systems (Schelkle, Reference Schelkle, Adamski, Amtenbrink and Haan2022). On the eve of the COVID‐19 crisis, this was good news indeed: our empirical study seeks to find out whether these bonding–bounding dynamics have been reinforced or weakened after COVID‐19.

We aim to build on this pioneering line of research in three ways. First, many things have changed since 2016. Brexit, the trans‐Atlantic populist crisis and the rise of strategic challengers (Russia and China) – not to mention climate change – may have brought Europeans closer to each other and sharpened the ‘bounding–bonding’ mechanism due to strained resources and a need for tighter solidarity mechanisms. Second, the bounding–bonding mechanism can rest on a variable geometry, which we aim to also probe in this article. We want to see not only whether all countries have a bounding–bonding mechanism between the EU and non‐EU countries, but also whether there are territorial demarcations of solidarity within the EU. Due to various political conflicts, past crisis experiences and currently unfolding phenomena like democratic backsliding and the Rule of Law crisis, we expect the bounding–bonding mechanism to create circles of solidarity. While most EU countries may prefer to redistribute more to EU countries than to non‐EU ones, they may also prefer to show more solidarity with some than others. Third, we take issue with the conclusion of Gerhards et al. according to which ‘the EU should refrain from developing supranational institutions warranting European solidarity and should look for alternative solutions’ (Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019, p. 10). If the recent literature on European solidarity during COVID‐19 has highlighted anything, it is that instruments of solidarity matter as much as their content (Beetsma et al., Reference Beetsma, Burgoon, Nicoli, Ruijter and Vandenbroucke2022; Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Kuhn, Meijers and Nicoli2021; Ferrara et al., Reference Ferrara, Schelkle and Truchlewski2023). Third, we seek to go beyond the generic ‘fiscal’ solidarity field and ask whether preferences implied by the bounding–bonding mechanism can vary by policy dimension. It can be that the demarcation of the solidarity space works for economic issues but not for the health aspect of the crisis which can trigger a cumulative logic of solidarity rather than a bounded one.

Probing the territorial bases of European solidarity is important because citizens from different European countries might express similar solidaristic preferences that can enable not only European‐level solutions but also give rise to divergent national coalitions. These ‘elective affinities’ of the European electorates can constrain governments at the European level during negotiations. Polarized preferences make polity building at the European level harder, while closer preferences enable engineering institutional innovations for bonding. Along the same lines, bonding at the EU level does not need to be homogeneous with preferences for different (re‐)combinations of bonding and bounding varying across citizens of different countries and enabling coalitional games.

For instance, richer, north‐western countries may prefer being solidaristic towards each other rather than the ‘underserving’ and eternally under‐prepared South, as Woepke Hoekstra's bluntness suggested.Footnote 2 That is, citizens from richer countries may not want to commit to solidarity because they may sense that this implies a long‐term costly burden if the beneficiaries of the solidaristic bargain are perceived to be always the same. By contrast, North‐Westerners may be more willing to support Central and Eastern European countries given the costs that these countries paid to reform themselves in the past and given their need to catch up. Conversely, the Rule of Law crisis and the divergence of preferences on social norms may undermine the feeling of solidarity that they have towards Central European countries, and they may thus be reluctant to help them more than Peru. Voters from poorer countries like Central and Eastern Europe would prefer to help each other out due to shared historical experiences (war, fascism, communism and neoliberal transformation). They may be less willing to offer help to comparatively richer Southern countries with which they are catching up and which are not perceived as reforming as much as they did in the post‐communist period. This was precisely the reason why the Slovak government collapsed in 2011 and refused to contribute to the bailout of Greece (Schelkle, Reference Schelkle2017, p. 168). Additionally, Central and Eastern Europeans may be less willing to help richer North‐Western citizens because they are perceived as being wealthy enough and resilient to manage the crisis on their own. Conversely, if some actors undermine common norms and political orders but continue to benefit from EU public goods, they are perceived as free riders (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005, pp. 7−10; Fenger, Reference Fenger2009) and might be less likely recipients of solidarity.

Consequently, circles of bonding may emerge within the European polity itself: respondents will prefer to help Europeans rather than outsiders, but they will also prefer to help some Europeans more than others. Such a basis for European solidarity could trigger political problems: indeed, the constituents of a polity should be treated equally for a polity to be sustainable in the long run. All in all, the creation of ingroup solidarity may not be homogeneous: despite the bounding–bonding nexus happening, some states may be more willing to contribute to some than others. We expect this to be dependent on various factors such as geopolitical proximity, crisis experience and deservingness. Generally, we expect bonding to happen towards more similar members of the community, that is, Westerners have a more of a preference to help Westerners than (in order) Peru, Southerners and Easterners and so forth. Additionally, we hypothesize that, given the current Rule of Law crisis and the upheaval about the conditionality of NGEU, Europeans will be less solidaristic with countries which are seen as obstructionist and not playing by the rules (e.g., Poland and Hungary).

The nature of bounded solidarity

Our article builds on a large literature on European solidarity during crises (Gerhards et al., Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019) like the Euro Area (Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014; Franchino & Segatti, Reference Franchino and Segatti2019), immigration, refugees, inequality and welfare state (Burgoon, Reference Burgoon2009; Reference Burgoon2014; Finseraas, Reference Finseraas2008) and the COVID‐19 crises (Beetsma et al., Reference Beetsma, Burgoon, Nicoli, Ruijter and Vandenbroucke2022; Bobzien & Kalleitner, Reference Bobzien and Kalleitner2021; Cicchi et al., Reference Cicchi, Genschel, Hemerijck and Nasr2020; Ferrara et al., Reference Ferrara, Schelkle and Truchlewski2023), to name but a few. We aim to further explore whether the design of solidarity has an impact on preferences for redistribution. We single out three such dimensions: the channels, the policy dimensions of the crisis and the instruments.

Channels: Transnational versus bilateral

First, it is important to know whether solidarity should be channelled through the European level of the polity – thus participating in the elaboration of a new layer of risk‐sharing – or whether European solidarity should be channelled through bilateral help. National bilateral solutions can be seen as more temporary, made on an ad hoc basis, not unlike helping outside countries hit by a crisis or extreme natural event. Conversely, channelling solidarity through the European level implies institutional innovation, sets precedents for the future and creates long‐term iterations between constituent members of a polity. However, channelling solutions through the EU level could also constitute a form of freeriding, as respondents might prefer to shift (even if temporarily) the burden from their national systems. We test such a freeriding mechanism using questions of European identity and views on European integration. Generally, preferences for European‐level solutions should be particularly preferred by those respondents with more pro‐European views. Consequently, we consider as evidence for freeriding if preferences for channelling solutions at the EU level do not vary by identity and views on integration.

Bonding across policy dimensions in the COVID‐19 crisis

Second, the multi‐faceted aspect of the COVID‐19 crisis allows us to enquire into how bonding is triggered across different policy dimensions of the crisis. In the scenarios, we propose to our respondents, we differentiate between health and economic issues, following the most up‐to‐date literature (Heermann et al., Reference Heermann, Koos and Leuffen2023)Footnote 3 which finds that, in general, respondents are more keen on providing medical than financial help. Our study being focused on the COVID‐19 crisis does not aim to compare across different crises hitting different policy domains and acknowledges that the economic and public health aspects of the crisis are deeply intertwined. Nevertheless, we argue that differentiating between the economic and health policy dimensions of the COVID‐19 crisis is important not only given the relative salience of these two dimensions in the public discourse related to COVID‐19 but also given the fact that solidarity instruments usually vary widely across these dimensions. First, health‐based solidarity is much more temporary than economic‐based solidarity. Health issues are very much related to a single and extraordinary situation, while economic solidarity implies commitment over the long run and sets a precedent for future recessions. Second, the different nature of economic threats and health threats triggers different emotional and blame‐attribution dynamics. The exogenous health threat of the COVID‐19 crisis touched upon universal health concerns experienced symmetrically across member states. The economic threat of the crisis, on the other hand, was much more bound to open old wounds from previous crises, highlighting Northern‐Southern divides, and hence triggering arguments blaming the various preparedness levels of the national systems. Given these differences between the two policy dimensions, we expect respondents to show much higher levels of solidarity in the health dimension, than in the economic one.

Instruments of solidarity within policy dimensions

Finally, the re‐combinations of the ‘bonding–bounding’ mechanism can vary with the type of implemented solidarity in each specific policy domain. We consider differences in preferences for repayable versus non‐repayable instruments (loans vs. grants) previously pointed out as consequential in the literature (Cicchi et al., Reference Cicchi, Genschel, Hemerijck and Nasr2020). The difference between loans and grants was hotly debated during the 5 months that led to the NGEU package (de la Porte & Jensen, Reference de la Porte and Jensen2021). Grants emerged as a solution to a symmetric crisis which followed bitter debates on austerity and conditional bailouts. Loans were, therefore, politically toxic. However, at the same time as richer European countries acknowledged that they needed to be solidaristic with other EU members, they also underlined that they were equally affected by the crisis, therefore requiring a certain balance between loans and grants (Schelkle, Reference Schelkle2021). Generally, we expect the difference between the two to be driven by the simple reason that the first is repayable while the second is not. Within the health dimension, we explore preferences for aid in the form of medical equipment and vaccines. While the sharing of medical equipment within EU member states was faced with heated debates at the beginning of the COVID‐19 crisis with countries withholding such equipment, the organization of the vaccination drive was generally considered a success story (even if after an initial slow start). Given these differences in the two types of health solidarity, we expect respondents to be more solidaristic when it comes to the sharing of vaccines, as such a type of help is less likely to open old wounds.

Experimental design and data

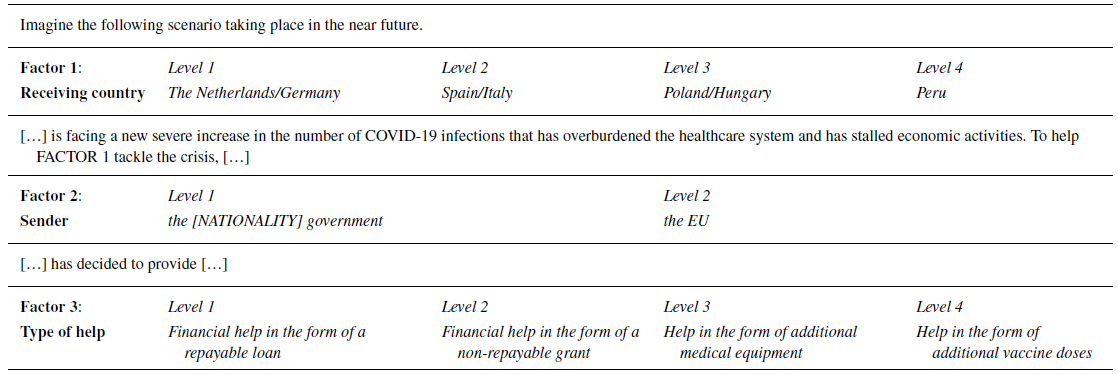

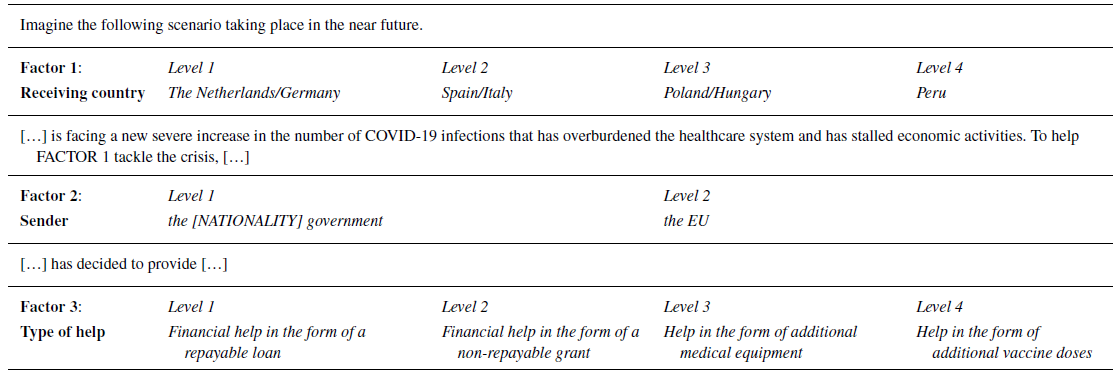

We use an experimental design that leverages factorial vignettes, a form of survey experiment widely used in psychological, sociological and more recently, political science research and which enables us to examine respondents' preferences for and evaluations of various hypothetical scenarios (so‐called vignettes) in which combinations of factors/characteristics are varied randomly. Survey experimental designs, in general, are considered to achieve the internal validity of classic experimental studies due to randomization of factors while enhancing the external validity of these by affording the same sampling strategies as those of surveys (Aguinis & Bradley, Reference Aguinis and Bradley2014). Furthermore, in comparison to classic survey experiments, a factorial design allows us to estimate the causal effects of multiple treatment components, rather than a single treatment, and assess several causal hypotheses simultaneously (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). For the factorial vignettes used here, participants were presented with mock descriptions of various countries (FACTOR 1) being affected by a new severe increase in the number of COVID‐19 infections that has overburdened the healthcare system and has stalled economic activities. Given these scenarios, either the national government or the EU (FACTOR 2) decides to offer various types of financial and medical aid (FACTOR 3). It is important to note here that our experiment is focused on the positive, territorial dimension of solidarity within the COVID‐19 crisis, rather than aiming to gauge normative aspects, such as deservingness, or aspects that might vary across different types of crises, such as symmetry. Our choice of factors, hence, follows the three dimensions (channel, policy dimension and instruments) identified in the section above. Table 2 presents the various factor levels and complete formulation given to the respondents. Manipulating these three factors resulted in 32 (4*2*4) possible policy scenarios. Out of these 32 scenarios, each survey respondent was randomly assigned to three such scenarios and was instructed to give a numerical rating representing their degree of agreement with the decision to help on an 11‐point scale. Note that as opposed to conjoint experiments, respondents were not made to choose between these scenarios, but just to rate each.

Table 2. Experimental design

aFor the European member states, two country options were introduced in order for respondents in one region to not get their own country. For example, respondents in the Netherlands who randomly get assigned Level 1 of Factor 1 will receive Germany in this scenario.

The data for this study was collected as part of a survey conducted in eight EU countries (Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, France, Sweden, Poland, and Hungary) in the framework of the ERC SOLIDFootnote 4 project (‘Policy Crisis and Crisis Politics, Sovereignty, Solidarity and Identity in the EU Post‐2008’).Footnote 5 Interviews were administered between 20 and 30 December 2021 on national samples obtained using a quota design based on gender, age classes, macro‐area of residence (NUTS‐1) and education. The total sample size for the survey was 8916, with national sample sizes varying between 1067 and 1304. The randomization of factors and levels resulted in a balanced assignment of all scenarios across the respondents (see online Appendix Table A1).

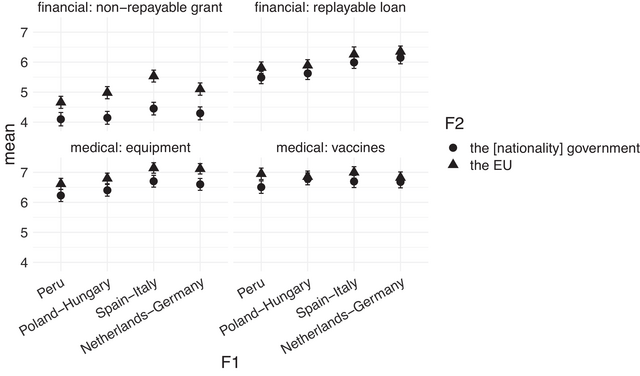

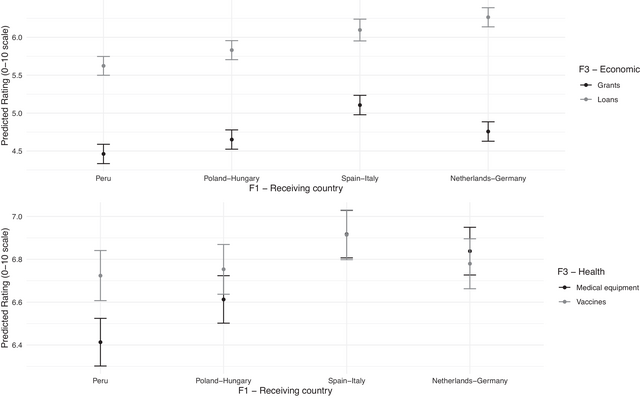

Figure 1 presents the means of the various factor‐level combinations in our experiment. Concerning forms of help (F3, differentiated by the four graphs), the two health measures included in the experiment (vaccines and medical equipment) appear to be most preferred among respondents, followed by loans, while grants appear to be the least supported measure. Regarding the recipients of this help (F1, differentiated vertically within each box), Southern and North‐Western European countries are the ones receiving the greatest level of support across all measures. This is surprising given that several countries in this group are part of the Frugal Four coalition (the Netherlands and Sweden, and their initial ally, Germany). We further explore this result below. Finally, when it comes to the provider of help (F2, differentiated by shape within each graph), while respondents seem to on average prefer the EU to grant all forms of help, economic or health related, their preference for the EU is highest when it comes to grants.

Figure 1. Means and confidence intervals (95 per cent) across factor‐level combinations.

Results

Our main goal is to estimate what characteristic of a scenario increases or decreases the appeal of that scenario when varied independently of the other attributes included in the design, but also the interactions between these attributes. Since we are repeating measurements across respondents (three vignettes per respondent), we resort here to using linear mixed‐effect models, with three‐way interactions, a random intercept for respondent and country fixed effects.

Circles of bonding

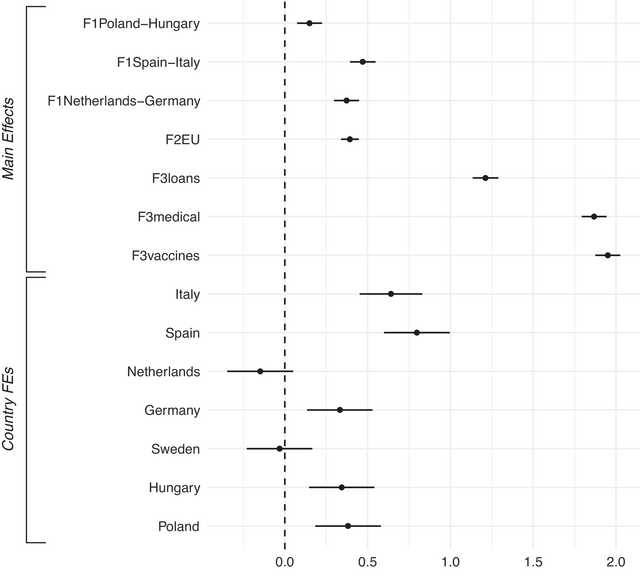

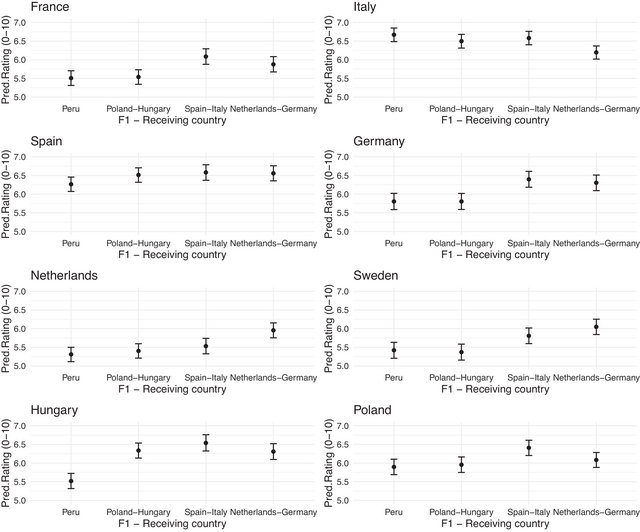

Figure 2 presents the result of our main models without interactions for studying average main effects.Footnote 6 For Factor 1 we observe that indeed Europeans are more willing to be solidaristic towards other EU members, rather than our baseline country – Peru with effect sizes up to 0.5 on the 11‐point scale measuring the dependent variable. This result strongly underlines that on average, bonding is bounded in the EU and there is a European territorial basis of solidarity. Regarding the channel of solidarity, respondents prefer on average the EU: scenarios with solidarity organized at the EU level are rated on average 0.4 points higher. We further explore below whether there might be freeriding behind this preference. Finally, as expected, respondents are more solidaristic with health measures than economic measures, with the highest effect sizes out of our three factors (close to 2.0 points on the 11‐point scale measuring the dependent variable). Furthermore, they prefer on average loans to grants, likely because of their repayable nature.

Figure 2. Main models with a random intercept for participant, and country fixed effects.

Note: The x‐axis measures effect sizes of each factor level compared to a baseline level (France, baseline for country FEs; Peru, baseline for F1; the government, baseline for F2; grants, baseline for F) on scenario rating measured on an 11‐point scale.

Given the expected heterogeneity regarding preferences for solidarity, the country fixed effects (the effects plotted at the bottom left of the figure) are also of interest to us. The findings indicate that irrespective of the measure (economic or health related; institutionalized or not), the recipient country or provider of help (EU or national governments), Spain and Italy are most likely to be solidaristic, while Sweden, the Netherlands, and France are the least likely (keeping in mind that France is the baseline category). This aligns with our expectations of these countries’ positions guided by their respective policy positions during the COVID‐19 crisis (Italy and Spain as vocal members of the COVID‐19 Letter 9 group, and the Netherlands and Sweden as members of the Frugal Four). While we cannot show whether respondents have been cued by their national elites, their positions are remarkably similar to the policies pursued by their respective governments. Perhaps more surprising is Germany's position as relatively not frugal, even in comparison to France. This indicates that contrary to discourses on Germany's ordoliberalism in the supply side of politics (Hien & Joerges, Reference Hien and Joerges2017), on the demand side there is a lot of leeway for solidarity. The same cannot be said about France whose average position aligns with the Frugals, despite the French government's historical preference for more redistribution. Establishing the direction of causality between elite cueing and public preferences is beyond the scope of this article, but previous research shows mixed evidence, with some studies proposing a dual‐process model in which party elites both respond and shape public views (Steenbergen et al., Reference Steenbergen, Edwards and De Vries2007).

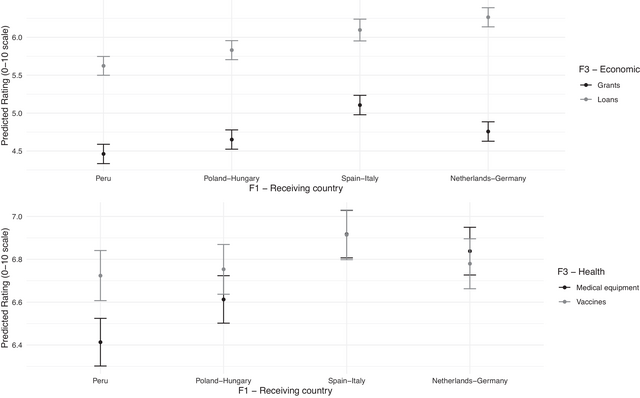

For exploring interactions, we follow up on our main model with an analysis of simple main effects (one‐way models of one factor at each level of another factor). In Figure 3, we analyse the interaction between types of help (F3) and receiving countries (F1). In terms of economic measures (top plot), our results indicate a strong preference for repayable loans across the board (with the difference in predicted rating varying between 1 and 1.5 points and crossing the mid‐point of our 0–10 point scale indicating a switch from negative to positive attitudes on average). Nevertheless, the intensity of this preference varies across recipient countries. Spain or Italy are generally the preferred recipients of grant measures. Conversely, Northern European countries are significantly better rated in receiving loans. Given the scars of the Eurozone crisis and the levels of distrust towards Southern European member states (including the reluctance surrounding NGEU in spring 2020), this result is not surprising. What is more surprising is the fact that while solidarity towards North‐Western and Southern EU member states is significantly higher than our non‐EU control country (Peru), the same cannot be said about Central‐Eastern Europe. Poland and Hungary appear to be left outside this core circle of bonding. At this point, it is unclear whether this lack of solidarity towards these member states is due to their newcomer status or due to the role they played in the ‘Rule of Law’ and conditionality debate. Given this, we further explore below (Figure 7) whether this effect is tied to respondents’ views of these countries as obstructing the EU in reaching the best response to the COVID‐19 crisis, with results strongly pointing to the role played by the Rule of Law debate. Nevertheless, Figure 3 generally suggests that the EU polity is bounded within. We obtain similar results on the outsider status of CEE countries in terms of health measures such as medical equipment. Finally, it is only vaccines where we do not see European solidarity only prevailing as there is no significant difference when it comes to recipients. Again, as explained before, given that by December 2021, the European population was vaccinated to a high degree (or at least they were not facing vaccine shortages), this result is aligned with our expectations.

Figure 3. Predicted rating for the effect of receiving country by type of help.

Given the differences between preferences for certain recipients of help found above, our next set of results explores coalitional dynamics and possible inner circles of bounding by analysing an interaction effect between the respondent's country and the country receiving help in the scenarios given. In Figure 4, we plot the effects of F1 – country receiving help by each respondent country including in our sample. One first finding highlighted by the figure is that respondents in France, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden seem to coalesce into an inner circle of solidarity. Despite small effect sizes, respondents in these countries significantly prefer to help other countries in this inner circle and Southern European member states (though the two frugal members of the group want so to a lesser extent) but not member states in Central‐Eastern Europe. When it comes to Southern and Central‐Eastern European member states, we can see that these hardly have affinities with each other in their respective groups. On the one hand, Spain appears to gravitate towards the inner core in wanting to help EU member states more than the baseline country of Peru, but it is less frugal than the inner core as Spaniards also want to extend help to Central‐Eastern Europeans.

Figure 4. Predicted rating for the effect of receiving country by respondent country.

On the other hand, Italy appears the least frugal (Italian respondents have the highest predicted rating irrespective of scenario, with average predicted ratings more than 1‐point higher than, for example, Sweden in the case of Peru and Central‐Eastern European countries), but we can now see that this is not homogeneous across receiving countries. Italians seem to apply a need‐based criterion of help as they prefer poorer countries within and outside the EU in comparison to the Netherlands or Germany. In this respect, Italy appears as an outlier in comparison to all countries in our sample as they do not want to help any member state more than the control country of Peru. Given that Italy was the first and, arguably, worst hit by the COVID‐19 pandemic, it is understandable that the Italians’ criteria for help might be more need‐based than affinity‐based compared to the other countries. Additionally, given the austerity wounds Italy had from the Eurozone crisis, and the blunt response they received from the EU (and especially the Netherlands and Germany) in the initial phases of the pandemic, it is not counterintuitive that they want to help the Netherlands or Germany the least out of all other options. Moving to Central‐Eastern Europe, we see that Hungary draws the strongest difference between EU member states and the outsiders in terms of willingness to help (up to 1 point lower predicted rating when Peru is part of the scenario). One reason behind this marked difference stands in Hungary's very Europe‐centric discourse, focused on anti‐immigration from outside Europe and on protecting European (Christian) values. By contrast, Poland does not seem to differentiate between most EU member states and the outsiders, except for Southern Europe (the most hit by the COVID‐19 pandemic).

The nature of solidarity: Channels, instruments and policy domains

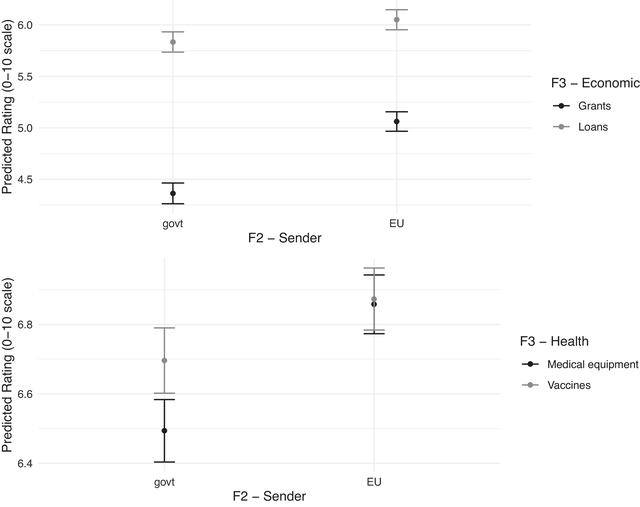

For interpreting the effect of F2 and F3 regarding the type of help and the channel preferred by respondents, in Figure 5 we report the effect of F2 (channel) by each level of F3 (sender of help). In terms of the channel of help, Figure 5 shows that the EU is generally significantly highly rated as the preferred provider of solidaristic measures across all four types of measures included in our vignettes. Nevertheless, we see that we have a significant interaction between the type of help and preference for the EU as the provider. Respondents seem to prefer the EU more as a provider when it comes to grants (with a 0.7 difference in predicted rating) than loans (with a 0.2 difference in predicted rating), and more in what regards medical equipment, than vaccines. Concerning health measures, this difference is partly explained by the fact that the vaccination roll‐out was already well underway in December 2021 with countries not experiencing significant shortages. Regarding economic measures, this indicates that while loans are still the preferred economic type of help overall, the size of the effect of the EU being the provider of help as compared to national governments is larger when it comes to grants.

Figure 5. Predicted rating for the effects of the sender (government vs. EU) by the type of help.

In terms of policy domains, the findings indicate that health‐related forms of help are generally rated higher, irrespective of the sender (the predicted rating on the y‐scale for health measures varies between 6.5 and 6.9, whereas for economic measures it varies between 4.4 and 6.1). Moreover, vaccines are the preferred type of help. Given the saliency of the health dimension and the fact that this dimension appeared as the highest perceived threat of the COVID‐19 crisis (Oana et al., Reference Oana, Pellegata and Wang2021), these results are unsurprising. Additionally, given that by the end of 2021 when our survey was fielded, medical supplies and vaccines were no longer in short supply, the acceptance of these forms of help was also not hindered by national shortage threats. Beyond the health dimension of help, when it comes to economic help, perhaps the most striking result is the significant and large difference between preferences for loans and grants, with loans being the preferred form of help. While the preference for loans is likely driven by their repayable nature, it is worth noting that observing this preference can have important implications for EU polity building as loans entail institutionalization and more permanent political exchanges.

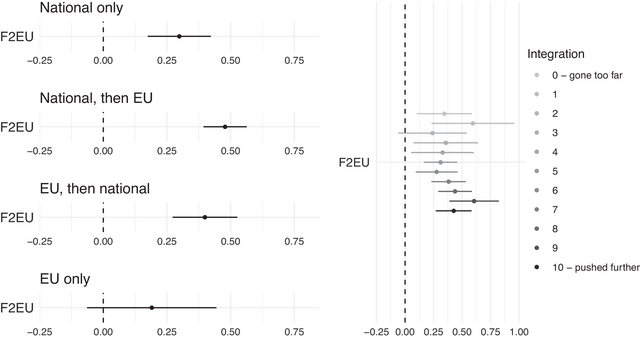

As we previously argued, channelling solutions through the EU level could also constitute a form of freeriding, as respondents might prefer to shift (even if temporarily) the burden from their national systems. We test such a freeriding mechanism in Figure 6, expecting that preferences for European‐level solutions are more strongly preferred by those respondents with more pro‐European views. Our results are pessimistic in this regard: there is little variation in preferences for the EU channel across both types of national or European identity and views on European integrationFootnote 7. Nevertheless, one could argue that the end justifies the means, as our findings still strongly underline that citizens do prefer solidarity to go through the EU level rather than the national level, irrespective of its form. Whether this is a form of freeriding or not, the results show that European citizens do not fear/oppose EU‐level solutions in the bonding preferences which could lead to positive reinforcement effects as such a preference could enable further polity building.

Figure 6. Effect heterogeneity of support for the EU as sender by identity and views on integration.

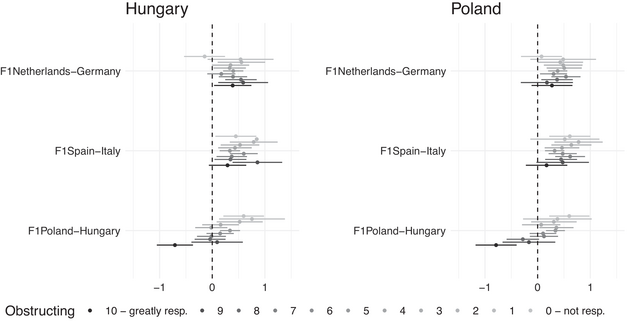

Finally, given our previous finding of Poland and Hungary as being left outside the core circle of EU bonding, in Figure 7 we explore whether this lack of solidarity is related to views of these countries as obstructing the EU in reaching the best response to the COVID‐19 crisis. The results indicate that the more one views these countries as obstructionist, the less solidaristic one is with them.Footnote 8 This strong effect heterogeneity indicates that the lack of solidarity with Hungary and Poland is likely driven by the Rule of Law and conditionality debate, rather than simply by dynamics between new and old member states. This result makes sense: as underlined in the theory on EU polity formation and the welfare state, ‘partial exits’ like the Polish and Hungarian ones – refusal of common norms and political orders but continued consumption of EU public goods – are perceived as a free rider problem and undermine solidarity in a bounded community between those who accept the polity and those who retreat into partial exit (Vollaard, Reference Vollaard2014; Genschel & Hemerijck, Reference Genschel and Hemerijck2018).

Figure 7. Effect heterogeneity of receiving country by considering Poland and Hungary as responsible for obstructing the EU in reaching the best response to the COVID‐19 crisis.

Conclusions: Bounded solidarity in times of COVID‐19

Contrary to previous European crises, COVID‐19 has arguably been characterized by a rather solidaristic response from the supply side of European politics. In this article, we aim to enquire whether the pandemic had a similar effect on the demand side in activating ‘bonding’ mechanisms between people and countries (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005; Ferrera, Reference Ferrera2005; Flora et al., Reference Flora, Kuhnle and Urwin1999).

The question of solidarity has been at the forefront of European theoretical, empirical and political debates since its inception, but particularly so since the eruption of the polycrisis in 2008. From the broader theoretical approach to the EU as a polity (or for any polity for that matter), the existence of bounded solidarity is considered to play a key role in polity maintenance and political structuring. Seen through Rokkanian eyes, loyalty is built upon the identity and solidarity that exists between members of a polity (Flora et al., Reference Flora, Kuhnle and Urwin1999). Early polity theorists like Rokkan and Bartolini were very sceptical that such a bounded solidarity could arise in Europe and underpin a centripetal political system through the channel of loyalty building. This scepticism arose mostly from the cosmopolitanism of the era and the relative destructuring of the national welfare states through market integration without a corrective European safety net (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005, p. 304). In Bartolini's own words, ‘the complex problem of fostering collective identification and solidarity across lingual, cultural, and institutional national diversities remains, and these internal differences have resulted into a paradoxical imbalance between considerable organization‐building efforts and poor collective action in the market and the polity’ (p. 291).

This article sought to shed empirical light on this key issue and to update prior research. The findings of the literature so far are mixed: while Gerhards et al. (Reference Gerhards, Lengfeld, Ignácz, Kley and Priem2019) show that fiscal solidarity during crises is more pronounced for other European countries than for non‐EU countries (using a survey encompassing 13 countries), Heermann et al. (Reference Heermann, Koos and Leuffen2023) find that this difference is actually not so pronounced (however, their sample is restricted to Germany), whereas other researchers find that solidarity is more pronounced at the national and universal level, but weakest at the European level (Lahusen & Grasso, Reference Lahusen, Grasso, Lahusen and Grasso2018). These findings are complemented by a broad literature on determinants of foreign aid which suggests that interests and cosmopolitanism – which are important in the EU context – play a major role (Prather, Reference Prather2020).

Our results suggest that in times of COVID‐19 bounded solidarity is a reality. We find that, Italy excepted, most countries are more solidaristic with EU countries than an outsider, baseline state (Peru in our case). Nevertheless, we find, on the one hand, a strong heterogeneity regarding the size of this effect: Spain and Italy are most likely to be solidaristic, while Sweden, the Netherlands, and France are the least likely, with Germany being less frugal than expected. On the other hand, solidarity is bounded within Europe itself, with an inner circle– France, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden – mostly wanting to help themselves and Southern member states, but not Poland and Hungary, likely because of the Rule of Law debate. Regarding channels of solidarity, our results show that respondents do prefer help, irrespective of its kind, to go through the EU level, rather than their national governments. While our evidence indicates that part of the reason for this preference might be a form of freeriding as citizens would like to shift the burden from their national systems or a misunderstanding of the functioning of the EU budget as they would think this does not incur national costs, such preferences can still be consequential as they can enable polity building through a permissive public opinion environment. Additionally, on the economic side, respondents preferred repayable loans rather than grants. While on the one hand, the loans’ repayable nature could be interpreted as indicative of lower solidarity, we do consider this preference as having important implications for EU polity building as it stands to show that public opinion is generally not opposed to a further institutionalization of solidarity instruments across member states.

Our approach and findings have limitations and important implications for further research. First, our results need to be replicated in the medium and long run because bounded solidarity could be the result of the COVID‐19 crisis. The confounding factor is that COVID‐19 was a substantial and, arguably, relatively symmetric crisis that came on the heels of fragilizing events like the Euro Area crisis, austerity, populism, transatlantic tensions and the rise or return of geopolitical challenges. Thus, the demand for common solidarity may have been higher both due to temporal reasons and due to the peculiarities of the crisis itself. While transboundary crises like COVID‐19 or war can spur bounded solidarity (Freudlsperger & Schimmelfennig, Reference Freudlsperger and Schimmelfennig2022), asymmetric crises do not necessarily do so (Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2020; Ferrara et al., Reference Ferrara, Schelkle and Truchlewski2023). It can also be that bounded solidarity dissipates over time and thus repeated measurements are important.

Second, as our results suggest, bounded solidarity can be very much heterogeneous within the EU. Why this is the case is a research question that needs to be further explored. Is this due to national ‘deservingness factors’ or rather to the fact that countries respect common European rules (Afonso & Negash, Reference Afonso and Negash2023; Harell et al., Reference Harell, Banting, Kymlicka and Wallace2022; Heermann et al., Reference Heermann, Koos and Leuffen2023)? The answer to this question can also vary by country: for instance, creditor countries may look closely at whether recipient countries respect the Stability and Growth Pact and democratic standards, while, for instance, poorer EU countries may be more solidaristic with richer EU countries if their crisis was not self‐inflicted.

Third, the geography of bounded solidarity needs to be explored over time. If our results are replicated in the future and patterns of bounded solidarity do not change, this may be the sign of profound territorial divisions underpinning the European polity. If, however, these patterns vary over time with events, this would be an indication that national respondents pay attention to how other member states fare and what should be their place within the new solidarity regime of the EU. This could prove crucial for the future of NGEU, which is temporary.

Finally, our results have profound implications for policymaking within the EU. We show that European solidarity is indeed territorially demarcated, with bonding being bounded to the EU community. Public opinion constitutes a highly enabling environment for channelling solidarity through the European level, through solutions that might imply repeated interactions and, thus, spur institutional innovation and EU polity building, rather than more ad hoc national bilateral solutions. Nevertheless, we find that there are important dynamics between EU member states that can hardly be overlooked, creating unequal bonding preferences and circles of solidarity. Whereas an inner circle of Southern and North‐Western Europe is rather willing to be solidaristic with itself, this is hardly extended to Hungary or Poland, given views on these countries as obstructing the EU in reaching the best response to the COVID‐19 crisis. Partial exits thus come with a real cost in solidaristic attitudes.

Acknowledgements

The data were collected for the SOLID research project (‘Policy Crisis and Crisis Politics, Sovereignty, Solidarity and Identity in the EU Post‐2008’) financed by EU Grant Agreement 810356 – ERC‐2018‐SyG (SOLID). We want to thank our colleagues at the European University Institute (EUI), the London School of Economics & Political Science (LSE), the University of Milan (UNIMI), and the Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Foundation for their involvement in the preparation of the survey questionnaire and feedback on earlier versions of this paper. We also want to thank participants at the CES 28th International Conference of Europeanists in Lisbon, 2022, for comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding Information

This study was supported by the SOLID research project (‘Policy Crisis and Crisis Politics, Sovereignty, Solidarity and Identity in the EU Post‐2008’) financed by the ERC Synergy Grant Agreement 810356 (ERC‐2018‐SYG).

Data availability statement

The data and replication code that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to an embargo on the data by the project financing the data generation.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: