1 Introduction

Evidence strongly suggests that high-quality managerial practices are associated with better organisational performance across a range of settings.Reference Bloom and Van Reenen1,Reference Bloom, Propper, Seiler and Van Reenen2 Operations management – the discipline focused on the design, planning, and delivery of processes and resources – is an important source of such practices. With deep roots in the world of industrial engineering,Reference Lewis3 operations management emerged as a standalone discipline with the rise of the quality movement, led by people like W. Edwards Deming,Reference Best and Neuhauser4 and growing international awareness of concepts like the Toyota Production System.Reference Samuel, Found and Williams5 It also offers pragmatic insights and opportunities for improving efficiency and effectiveness in healthcare organisations. Several key tools of operations management have their own Element in this series – for example statistical process control,Reference Mohammed, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic6 lean,Reference Radnor, Williams, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic7 measurement for improvement,Reference Toulany, Shojania, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic8 and supply chain management.Reference Williams, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic9 This Element offers a complementary overview, discussing in particular three major areas of operations management in healthcare: capacity management, the potential of focused work, and the importance of managing ‘people plus process’.

We set the scene by discussing the fundamental building block of operations management – the idea of process. Framed as either a noun or a verb, process is the series of actions or steps that bring together all sorts of resources to achieve a particular goal.

2 Processes

A foundational principle of operations management is to think about work as a collection of processes. This requires asking how an organisation is changing the state of something, be it bending metal in a factory, baking dough in a bakery, or altering the health status of a patient. Processes will typically involve inputs, activities, and outputs, ultimately leading to outcomes.

The doctor–patient consultation in general practice is an example of such a process. The clinical processes, at first glance, are the most evident. The inputs include the patient with a particular health status and the doctor with competencies and qualifications. Clinical activities may include giving and taking a history, conducting examinations, or giving treatment, all of which may have experiential dimensions (e.g. body language). The output of the consultation might be a diagnosis, a prescription, a follow-up appointment, referral to a specialist service, or advice and support. The outcomes might include patient health status and experience, and staff experience. In this way, the clinical process leads to a change in the state of the patient (and possibly also the practitioner). But these clinical processes cannot happen without supporting operations processes. For example, administrative staff are needed to manage the systems needed for booking appointments and maintaining patient records. Likewise, numerous administrative activities will run alongside the appointment: for example, putting this single appointment into an overall schedule for the doctor, procuring all the goods and services, staffing the practice, and managing premises to ensure they are clean and secure. All of this needs to be done in a context of multiple regulatory and legal requirements, alongside more general expectations of good practice.

Processes in healthcare are found, and need to be managed, at many different levels – from a single team through to an individual organisation, region, or the whole system.Reference Slack, Cooper, Roden, Lewis and Slack10 At each level, both the scale and scope of the processes and the resources to be planned and controlled increase, as does the complexity of the managerial tasks involved. Each level presents its own challenges. Simply considering how processes operate is valuable, as it shifts attention onto the goals and how they will be achieved, including the resources needed and used, the way work is carried out, and bottlenecks and constraints.

3 Capacity Management

Capacity management, which aims to align capacity with demand while optimising efficiency and productive use of resources, is a crucial element of operations management. Formally defined as the maximum level of value-added activity that can be achieved over a specified time period under normal conditions, capacity management involves ensuring that an organisation has the right resources at the right time to meet current and future demands.

The relationship between capacity and process is critical. Processes, as explained above, are how inputs are converted into outputs (and ultimately outcomes). Typically made up of a series of interdependent tasks of varying durations and complexities, how processes are designed and executed is critically important to capacity. A process that is not designed or operated well is likely to consume more capacity and produce less value than a more optimised process. Most operations management textbooks suggest that capacity is determined by first calculating the capacity of each element in isolation, and then the ‘effective capacity’ is defined by the process step with the smallest, or bottleneck, capacity. However, healthcare poses a number of distinctive challenges in determining and, ultimately, managing capacity.

One of these is the nature of demand for healthcare services. Nearly five decades of researchReference Atsma, Elwyn and Westert11 confirm an association between the use of capacity and variability in both clinical practiceReference Wennberg12,Reference Westert, Groenewoud and Wennberg13 and patient behaviour (e.g. symptom identification, attendances, and choices).Reference Hwang, Atlas and Cronin14,Reference Dantas, Fleck, Oliveira and Hamacher15 Health needs are highly complex, shaped by demographic, socioeconomic, epidemiological, seasonal, technological, and policy factors, such as the ageing population, new diagnostic and treatment options becoming available, and societal expectations increasing. The system itself can create demand, for example treating a condition can lead to further needs, such as follow-up tests and long-term care.Reference James, Denholm and Wood16 Furthermore, a significant proportion of demand is unpredictable and urgent, while individual judgement and skills can create more variation.Reference Allder, Silvester and Walley17

Capacity in healthcare needs to be considered at different levels.Reference Cardoen, Demeulemeester and Belien18,Reference Ma and Demeulemeester19 One might be at microsystem level. When a trauma patient arrives in an emergency department requiring surgery, capacity issues relating to the available staff and operating theatre availability will all be important. But capacity also has to be planned at whole system level – for example, in making decisions about where emergency departments should be located.20 Decision-making about capacity will be different at these different levels. Staffing capacity will be managed

minute-by-minute – for example, who is available to respond to a patient now

day-by-day – for example, how many nurses are off sick

month-by-month – for example, shift patterns and holiday bookings

multi-year-by-multi-year – for example, how many professionals are in training, recruited, and retained.

These decisions will be taken largely at the local level by managers within organisations. But decisions about capacity at the system level may be made at the policy level, by very different stakeholders, who may have varying interests and motivations.

Another challenge for capacity management in healthcare is the extreme complexity of many processes, which typically involve multiple forms of interdependence and variation. Many activities may have to be combined across multiple services to produce a single resource.Reference Bo, Dawande, Huh, Janakiraman and Nagarajan21 For example, a specialised service, such as oncology, might have to

address different patient volumes and disease types

manage supply chains for interventions such as chemotherapy (including for rare diseases)

coordinate with services such as pharmacy, radiology, and surgery

ensure availability of staff with rare skillsets

manage procurement and maintenance of dedicated equipment.

These processes may require significant coordination and collaboration across teams, organisations, and external services. They can be fraught with challenge, with some elements of a process more under the control of a service than others. It is common in healthcare for expensive infrastructural resource to be used for multiple activities (e.g. a CT scanner used both for emergency and elective care), therefore it may not be straightforward to ensure optimal use of the capacity for the right patients at the right time. All of this happens within wider funding patterns, which determine overall scale and scope for the service.Reference Street, Nils, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic22

3.1 Managing Capacity in Healthcare

The operations management toolbox offers a range of techniques that can be used to manage capacity, including demand forecasting, capacity evaluation, capacity adjustment, and performance monitoring. In healthcare, algorithms and rules to maximise use of capacity are often proposed, but capturing the complexity and variation of real practice can be very challenging. In a highly cited review of outpatient scheduling, Cayirli and VeralReference Cayirli and Veral23 noted that no appointment system performed well under all clinical circumstances.

One evidence-based approach to managing capacity in healthcare involves queuing theory. While a specialist mathematical discipline, it is widely used in operational management theory and practice. It can be used to obtain important insights using simple data like average demand, average length of stay, variation levels, waiting times, punctuality, and so on.Reference Bretthauer, Cote MJ and Schultz24 Its usefulness can be illustrated by looking at the example of waiting times in an urgent care clinic staffed by a single doctor. The variability-utilisation-time (VUT, KingmanReference Kingman25) formula can estimate how long patients will likely wait (the queue) based on two key factors:

Utilisation: This is how busy the doctor is. For example, if patients arrive at an average rate of 11 per hour and the maximum the doctor can see is 12 patients per hour, then the utilisation rate is close to 1 (high).

Variability in arrivals and service times: Patient arrivals and consultation times are rarely consistent. Instead of arriving at evenly spaced intervals, some patients may arrive early, late, or not at all. Some patients may come in with complex health issues that take longer to address, while others have routine check-ups.

By directly applying the VUT formula, the clinic manager can get a decent estimate of average patient waiting times. This can be helpful for staffing decisions, such as whether a second doctor is needed to reduce waiting times when variability or demand increase significantly.

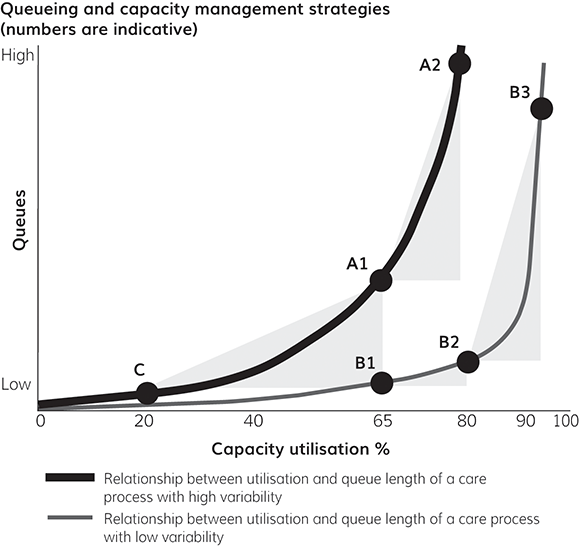

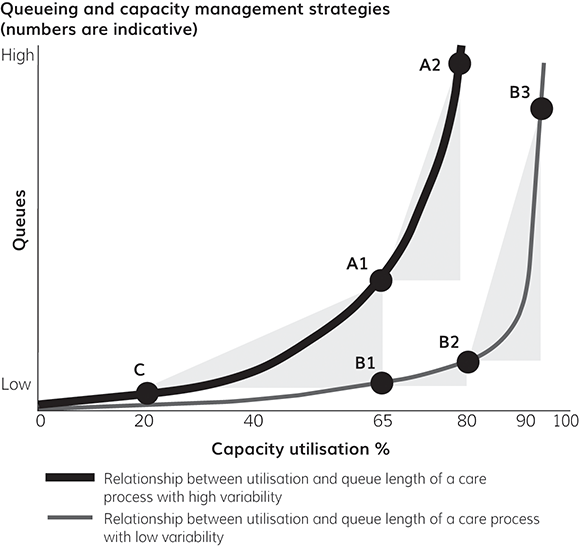

The VUT formula can also be used to produce more general insights into capacity management (see Figure 1). Here, the x-axis shows the utilisation of the system expressed in percent (e.g. how many cubicles are occupied). The y-axis is an indication of the length of the queue (e.g. how long a patient will have to wait to be seen in a cubicle). This is a good indicator for the overall responsiveness of the system – a long queue implies a bigger gap between demand and system response. The two curved lines represent the different relationships between utilisation and queue given either high (the thick line) or low (the thin line) levels of (patient and service) variability in the system. Insights from this way of thinking about and visualising queuing can help managers understand their operating constraints (where they are on the graph in Figure 1) and then help develop an integrative strategy that includes demand management, variability, and capacity factors.

Figure 1 Queueing and capacity management strategies (numbers are indicative).Reference Proudlove26

Point A1 represents a care process with mid-level utilisation (65% on the figure) and high variability (thick line). Point B1 represents a different care process with the same level of utilisation but lower variability (thin line). Point C represents a process with high variability (thick line) but much lower utilisation (20% on the figure). Now look at the consequences in terms of queues for these systems.

A1 and B1 have the same level of ‘busyness’ but their different variability characteristics mean A1 has higher queues. Using VUT logic, a process with higher variability will experience longer queues, even at similar levels of utilisation. In a higher-variability process, there can be larger swings in the time it takes to complete different jobs. For example, some tasks (e.g. assess the patient in the emergency department) might take significantly longer than the average, while others might be shorter (e.g. write a prescription). This variability makes it difficult to predict when a resource will become free. It also means that even if average utilisation is low, there can still be periods when a burst of arrivals or a few long service times create sudden peaks in queues. During these peaks, even a relatively underutilised system can become temporarily overloaded, leading to queue formation that takes time to clear. Thus, queues can expand quickly, even if, on paper, the process easily has capacity to handle average demand.

Now let’s consider what happens in process A when utilisation increases as shown by point A2 (80% utilisation on the figure). The same mechanics applies but the VUT module uses an exponential relationship to reflect the difficulty of operating close to capacity while also accommodating variability. Essentially, the process has less slack to handle each incoming job or patient, resulting in an even more rapid increase in queuing. More positively, from a capacity management perspective, the reverse is also true. Adding capacity to reduce utilisation back to 65% would have a significant impact on queues – although a further 15% reduction would have a diminishing impact. This is one of the key insights from the VUT logic – adding capacity does not always have the same impact on a process. It depends where you start from and what is happening with variability. If we now compare with point C, we see that the impact of variability is reduced to almost zero. Here the very low levels of utilisation mean there is ample slack to accommodate most variability – but, from a capacity management perspective, maintaining such a care process is challenging as it will frequently appear inactive.

We have already described point B1 as a process with high utilisation but relatively low variability. In systems with low variability, arrival and service times are more predictable. This generally helps maintain shorter queues, even as utilisation grows (point B2). The key VUT insight into this kind of low-variability system is how, as utilisation approaches 100% (point B3), waiting times will increase dramatically. This is because each additional job must wait for a longer period, which compounds over time, since VUT shows exponential behaviour. In this situation, even minor delays, such as a slightly longer-than-average time to see each patient, can cause the next job to wait. Without the capacity to absorb even these small variances, each delay creates a knock-on effect, causing the queue to grow.

3.2 Capacity Management Responses

Doing nothing and accepting long queues is an option, but there are meaningful, proactive strategies available. They fall into three categories: reduce or redirect demand, reduce variation, or add capacity.

Seeking to reduce or redirect demand as a way of managing capacity is a common strategy for policymakers and managers. For example, encouraging patients to self-manage chronic conditions, encouraging primary and secondary prevention, and shifting care into communities have been themes of the Carter Review of Productivity in the UK NHS,27 published in 2016, as well as the UK government’s 10 Year Health Plan for England, published in 2025.28 The design and evaluation of these kinds of efforts to reduce or redirect demand benefit from operations management techniques. For example, operations management can be used to reduce demand for pathology using tools like minimum retesting intervals,Reference Lang29 or through targeting of inappropriate requests (from both patients and staff). Jaeker and Tucker,Reference Jaeker and Tucker30 for example, explored the impact of adding in a ‘non‐value‐added’ justification step to the ultrasound ordering process at two North American emergency departments. They conclude that introducing ‘process friction’, which forced healthcare workers to explain the rationale for requesting an optional service, reduces the use of ultrasound (by 50% in their study) and other diagnostic tests.

A second option to improve how capacity is deployed is by reducing variation. A substantial body of research suggests that reducing unwarranted variation in processes through better planning of highly utilised resources, such as ICU beds and scanning (e.g. Jung et al.),Reference Jung, Pinedo, Sriskandarajah and Tiwari31 operating theatres,Reference Zhu, Fan, Yang, Pei and Pardalos32 and so on may be useful (see, for example, Box 1) as a way of better managing capacity.

The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota,Reference Ozen, Marmor and Rohleder33 faced significant challenges in managing capacity for orthopaedic spine surgeries due to high variability in surgery durations. While the average surgery took around 4 hours, some extended up to 18 hours, leading to unpredictable demands on operating room time. This variability, combined with Mayo’s patient-centred scheduling approach – where patients had input into their surgery dates – resulted in low operating room utilisation and frequent overtime for surgical teams. About 38% of surgical days ran past the desired end time of 5 pm, putting pressure on the surgical teams and limiting patient choice. To address these issues, a team of researchers worked with surgeons to develop a variability management strategy. The team used a 7-year dataset of over 2,500 spine surgeries to categorise procedures based on time distributions. This allowed for better scheduling predictions and grouping of surgeries with similar durations. A custom scheduling tool was then implemented, providing real-time feedback to surgeons and schedulers about the optimal days for surgeries. The pilot implementation resulted in a 19% increase in operating room utilisation and a 10% reduction in overtime.

The third option is to add capacity. As we discussed in Section 3.1, however, queuing theory tells us that high variability requires larger buffers or slack time to maintain smooth operations. In a high-variability system, even when utilisation is relatively low, unpredictability means that the system can face periods where unusually long service times or closely spaced arrivals overwhelm the available capacity. Without enough buffer, queues start forming. The level of analysis is important here. For example, localised incentives (e.g. payments for weekend surgery) might encourage staff to maximise throughput, but could lead to short-term capacity expansions that do not address overall demand patterns. Likewise, adding capacity at higher levels of aggregation – for example, by building more hospitals and expanding the health professional workforce – is far from straightforward. Expanding capacity can be slow, costly, and difficult to scale back. Active consideration needs to be given to how flexible future capacity will be as demand evolves.Reference Bazzoli, Brewster, May and Kuo34 One example is commissioning spaces that can be converted for different uses (such as converting general wards into ICU beds during a surge).Reference McCabe, Schmit and Christen35

4 Focus

In operations management, focus describes the extent to which an activity can be specialised in particular services or patient populations. Activities that change frequently and need a wide range of inputs, flexible facilities, skills, and technology tend to generate higher costs (and potentially more risk). In some circumstances, such as the emergency department, much of the variety may be unavoidable. In scenarios that lend themselves to specialisation, choosing to narrow the variety of work – through focus – may have significant benefits.

The operations management interest in focus dates to Skinner’sReference Skinner36 observation that factories tackling a limited set of tasks were more productive than similar factories attempting a more diverse set of tasks. Similar findings have been made in service settings.Reference van Dierdonck and Brandt37,Reference McLaughlin, Yang and Vandierdonck38 Although a lack of focus does not mean poor performance,Reference Ketokivi and Jokinen39 focus is often regarded as best practice in industry,Reference Tsikriktsis40 based on the logic it can help achieve higher volumes of work, enable economies of scale, and support sharing of fixed costs across more output. In healthcare, different approaches to focus can be used. Bredenhoff et al.Reference Bredenhoff, van Lent and van Harten41 define three approaches: by speciality, mode of delivery, and procedure employed. Dabhilkar and SvartsReference Dabhilkar and Svarts42 propose that a narrow range of interrelated factors – knowledge areas, procedures, medical conditions, patient groups, planning horizons, and levels of difficulty – can offer more focus than one with a broader range. Perhaps the most advocated type of healthcare focus (e.g. Hopp and Lovejoy)Reference Hopp and Lovejoy43 involves hospitals splitting out activities that are currently combined.Reference Cook, Thompson and Habermann44 This might involve, for example, separating pathways where it is possible to apply standardised treatment plans from pathways caring for patients with conditions that are more difficult to diagnose and manage.

The most established example of (procedural) focus in practice is the Shouldice Hernia Hospital in Canada.Reference Lorenz, Arlt and Conze45 Founded in 1945, the private 5-theatre, 89-bed surgical hospital is a centre of excellence in pure tissue abdominal wall hernia repair. It has also been a very popular Harvard Business School operations management case study since 1983.Reference Heskett46 The surgical teams perform more than 7,000 repairs annually, with an exceptional success rate. Wrapped around this medical focus is what is known as the ‘Shouldice experience’: the hospital environment is more like a country house hotel where the carefully planned patient care pathway – which can last up to five days (such repairs are typically day cases elsewhere) – is supported by numerous dedicated staff. Despite evolution in surgical techniques over time, Shouldice continues to achieve some of the best medical and patient experience outcomes well into its eighth decade.

Some specific features of Shouldice are important in weighing up the benefits and possible disadvantages (including inequities) of a focus-oriented approach. One feature is the careful selection of patients, who, as well as being wealthier than average, are refused or delayed surgery if they are not within 20% of their ideal body weight. Obesity is a clear risk factor in hernia recurrence, but the negative consequences of variability reduction need to be actively considered. This type of cherry-picking patients for focused operations, where hospitals prioritise treating less complex cases, can have significant negative consequences for the broader healthcare system. It can lead to inequalities in access to care, particularly for patients with complex, chronic, or less financially rewarding conditions who may be deferred or denied timely treatment. It may undermine the equity of healthcare delivery, as resources and attention become concentrated on patients who are easier and cheaper to treat, leaving those with more severe needs underserved. Furthermore, this approach can distort overall capacity management, creating an imbalance where some units are overburdened with challenging cases while others maintain higher efficiency and performance metrics by handling only straightforward cases.

Other examples include Coxa Hospital for Joint Replacement in Finland,Reference Rechel, Erskine, Dowdeswell, Wright and McKee47 and the Aravind Eye Hospital in India (Box 2).

If Coca-Cola can sell billions of sodas and McDonald’s can sell billions of burgers, why can’t Aravind sell millions of sight-restoring operations?Reference Rubin49

Venkataswamy set out to achieve a specific vision – eliminating blindness through cataract surgery. He went on to create Aravind, a high-volume (400,000 eye surgeries a year), high-quality, and low-cost ($50) operation. Aravind developed standardised processes for key operations, ensuring consistent and optimised delivery. An Aravind doctor performs more than 2,000 surgeries in a year, compared with the Indian average of 400. The Aravind model has been (at least partially) replicated in more than 300 hospitals globally.

Significantly higher productivity is achieved by adopting an assembly-line approach to surgery. Each operating room has one surgeon, but a minimum of two operating tables, multiple sets of equipment, and multiple nursing teams to carry out key non-surgical tasks, such as preparing the patient and administering anaesthetic. To allow the doctors to focus on the most critical tasks of diagnosis and surgery, Aravind has a large staff of nurses and technicians. This enables the surgeon to complete a surgery, turn around, and start the next, thus enabling a doctor to perform six to eight procedures per hour. Despite differing approaches, such as minimal downtime between surgeries and lower-cost intraocular lenses, the quality of care remains high. The Aravind Eye Care System achieves a cost of about $195 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), significantly lower than costs in the UK and US.Reference Le, Ehrlich, Venkatesh, Srinivasan and Kolli50

In addition to its 6,000 hospital outpatients, Aravind serves 1,500 patients in outreach camps every day. Mobile vision diagnosis centres, which employ tele-medicine, also allow doctors from the main hospital to evaluate and diagnose millions of patients at distance. Their focused process flow begins long before the surgery itself and involves registration, vision test, preliminary exam, refraction, final exam, counselling, and recommendation for surgery. Aravind also uses in-house manufacturing: the lens used to be a significant part of the fixed cost of the surgery; today the price of the lens has been driven down to less than US$10 (a 90% reduction).

As with any ‘best practice’, there are limitations. For example, while Aravind’s high-volume model is effective in delivering cataract surgeries, replicating its success in other contexts has proved difficult due to cultural and operational differences. Additionally, Aravind’s financial sustainability depends on a cross-subsidisation model, which could be vulnerable if the balance between paying and non-paying patients shifts due to economic changes. Concerns also exist about potential workforce strain and maintaining quality amidst high service volumes, which can impact staff wellbeing.

A large literature on focus in healthcare has emerged, with UK evidence generally suggesting that it could offer quality benefits across the system.51 Several studies of surgical centres, for example, have identified efficiencies, higher patient satisfaction, comparable or decreased mortality rates, and less adverse hospital-level outcomes (e.g. Cram et al.Reference Cram, Rosenthal and Vaughan-Sarrazin52). A study by Freeman et al.,Reference Freeman, Savva and Scholtes53 using 10 years of annual cost data and 145 million hospital admissions for over 2,000 treatments from 157 English NHS acute care trusts, has significant practical implications. For example, they suggest that if a pair of London hospitals redistributed elective specialties so that only one of them provided either service, then the cost of elective treatments could be 3.6% lower, without a substantial change in the hospitals’ total admissions volumes.

5 Process Plus People

Up to this point we have discussed the insights offered by a process perspective, but considering ‘process plus people’ is critical – not least because Bloom et al.Reference Bloom, Propper, Seiler and Van Reenen2 found that people-related practice gaps were a significant factor in lower-than-average scores for management quality achieved by public hospitals compared with private hospitals and manufacturing. Suboptimal processes can also result in significant professional time being diverted to managing interruptions and operational failures.Reference Sinnott, Georgiadis and Dixon-Woods54,Reference Sinnott, Moxey and Marjanovic55

Examples of interactions between people and process include multitasking, which is often an adaptive response to issues of workload and capacity. Multitasking can result in non-value adding activity, since task-switching imposes cost in time and performance. Tucker and Spear, for example,Reference Tucker and Spear56 showed that multitasking by nurses – frequently triggered by high workloads/utilisation – leads to resequencing of workflows and a loss of capacity linked to recovery after interruptions (e.g. a nurse both assigning colleagues to tasks and undertaking a medication round at the same time). Similarly, Froehle and WhiteReference Froehle and White57 showed how interruptions associated with multitasking lead to forgetting and reworking in radiology. A US study in emergency medicine found additional multitasking led to fewer diagnoses and an increased likelihood of a 24-hour revisit to the emergency department.Reference Diwas Singh58

Workarounds are another example of combinations of processes and people that emerge in healthcare settings.Reference Koppel, Wetterneck, Telles and Karsh59 Deviations from the official procedures that users adopt to navigate challenges or inefficiencies in the system, workarounds can enable something to get done in the moment but may recreate different (often hidden) forms of variability or even safety issues at a systems level.Reference Hewitt and Chreim60 For example, when faced with malfunctioning scanners, unreadable barcodes, or time pressures, a nurse might bypass intended process steps to maintain workflow continuity.

Operations management can help to optimise design of processes to address these kinds of problems. Process poka-yoke, ‘mistake-proofing’ or ‘error prevention’ in Japanese,Reference Schrage61 is one approach increasingly accepted as a safety tool in healthcare.Reference Grout62 The same interventions can play a fundamental, human-centred (i.e. considering natural human behaviours and limitations) role in capacity management and focus through variability reduction.Reference Macleod, Campbell and Macrae63 Poka-yoke principles include standardising processes – such as using central line kits with prearranged tools in a specific sequence, or creating immediate feedback mechanisms, like electronic alerts in medication administration systems to allow for rapid correction of mistakes. Process simplification and visual cues, including floor markings or visual guides around critical areas, reduce cognitive load on staff and make adherence to protocols more intuitive. Checklists have also been widely advocated as an approach to mistake-proofing.Reference Gawande64

Optimising processes in publicly funded models like the NHS, where processes are often not ‘standalone’, but instead use resources (for example, scanning facilities) shared across a number of activities, is often challenging. As briefly mentioned in Section 3, sharing can, for instance, create conflict between resource-providing departments and those deploying the resource.Reference Frangeskou, Lewis and Vasilakis65 When there is competition for resources, cooperation can be inhibited, and variations in care can emerge. For example, one hospital might prioritise scanning for one type of emergency condition (e.g. stroke) over another (e.g. trauma).

One possible way of addressing this kind of conflict is through relational coordination.Reference Gittell, Fairfield and Bierbaum66 An approach to building a network of communication and relationship ties among workers, relational coordination can improve service quality and clinical outcomes while also reducing lengths of hospital stay. Relational coordination uses both process concepts – boundary-spanning staff, shared IT infrastructure, cross-functional performance measurement, and flexible work roles – and frequent, timely, and problem-solving communication. Intriguingly, given our focus on process, Siemsen et al.Reference Siemsen, Roth, Balasubramanian and Anand67 propose a constraining factor or bottleneck model, based on the well-established motivation-opportunity-ability (MOA) model, to argue that managers can maximise such relational knowledge sharing by focusing on the bottleneck MOA variable (i.e. is it motivation or opportunity or ability?).

6 Critiques of Operations Management as an Improvement Approach

Despite the rich knowledge base on operations management, gaps exist and there is a clear need for ongoing original and translational work.Reference Dai and Tayur68 What is clear is that efforts to improve operations, while important, are not always straightforwardly positive.

Evaluating operations management interventions is often challenging, not least because there may be significant diversity in policy, design, and implementation. For example, KC and TerwieschReference DS and Terwiesch69 used hospital-level discharge data for Californian cardiac patients to investigate the effects of focus (discussed in Section 4) on operational performance at the organisational, operating unit, and process flow level. They found focus was associated with improved outcomes – namely, faster services at higher levels of quality, as indicated by lower lengths of stay and reduced mortality rates. But after controlling for selective patient admissions – that is like Shouldice, so-called cherry-picking easier-to-treat patients – the benefits persisted only at the operating unit level. Other research has found higher readmission rates for more complex patients treated at certain cardiac specialty hospitals in the US (e.g. Greenwald et al.).Reference Greenwald, Cromwell and Adamache70

On balance, the evidence suggests that, with the correct strategic intent and when well-executed, focus delivers improved cost and quality performance. However, dramatic redesigns seeking focus can be difficult to implement, for example, because of political, patient, and professional preferences. Kuntz et al.’sReference Kuntz and Scholtes71 exploration of the impact on mortality of reorganising hospitals into organisationally focused divisions for routine and non-routine services suggests that both routine and complex patients would benefit, but also that such a transition could be challenging. In line with the VUT logic described earlier, this raises important questions of optimal coordination, including issues of resource-sharing, between ‘focused factories’ and other care resources.

Technologies to improve operations can similarly bring risks as well as benefits. The Barcode Administration example given in Box 3 shows the positive side: reducing time to complete tasks, reducing variability, and freeing scarce medical professional capacity to focus more on clinical activities, such as patient consultations and therapeutic interventions. However, there are still notable risks. Contrary to initial expectations, and vendor promises, error proofing technologies can increase the workload, as tasks such as verifying system status and managing alerts can in practice demand additional time and attention. Moreover, hidden costs may arise, including expenses related to specialised training. The transition to new systems can also disrupt existing workflows, requiring adjustments and a learning curve for staff, which may temporarily hinder productivity. A thorough understanding of all the positive and negative impacts is essential for balancing the advantages and challenges of adopting such technologies.Reference Moore, Tolley, Bates and Slight73

Erasmus University Medical Centre in Rotterdam completed a major implementation of updated Barcode Medication Administration (BCMA) technology on infusion pumps in its operating rooms with the intent to enhance patient safety and increase the productivity of medication administration. The aim was to automate the double-check process during critical stages of medication administration, particularly at the start-up of infusion pumps and when replacing empty syringes. The updated system allowed real-time electronic verification, reducing reliance on manual double-checks by a coworker. Before implementation, compliance with double-check procedures was variable. Significant risks were identified at the point of syringe replacement, which accounted for 70.9% of medication administration errors (MAEs). Post-implementation observations revealed a marked improvement in compliance: the use of BCMA for syringe changes increased adherence to 85%, with 63.5% of instances using BCMA specifically. Additionally, MAEs at these critical moments were significantly reduced. The success of this system was attributed to a comprehensive strategy that included staff training, iterative process modelling, and overcoming technical barriers like unreadable barcodes.

Important learning from the research literature is that the impacts of process management on ‘experiential quality’ – people’s experiences of care and work – are not always positive and need to be considered (Box 4).Reference Chandrasekaran, Senot and Boyer74

In July 2021, the Bury Care Organisation tested a new way of working by holding a ‘Super Saturday Orthopaedics List’. Using part of the English NHS’s national Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT)Reference Chandrasekaran, Senot and Boyer74 and high-volume low complexity (HVLC)Reference Street, Nils, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic22 programmes, the Bury pilot aimed to reduce surgical waiting lists by using existing resources – a ring-fenced orthopaedic unit with standardised kit and consistent staff – to deliver more surgical procedures. Utilising two operating theatres, a team led by one consultant surgeon and two consultant anaesthetists successfully performed 10 arthroplasty cases in one day (as opposed to three to four cases per day per theatre under business as usual). As well as improved theatre productivity and utilisation, the project achieved reduced length of stay (and hence increased effective capacity), and post-pilot evaluations suggest improvements in both patient care and experience and staff morale. Although more evidence is needed on the clinical effectiveness and operational efficiencies that can be achieved by this type of service innovation, and their capacity for scaling up, they are part of the investment needed to tackle the long waiting times for elective care.

Evaluations of this large-scale programme are only just emergingReference Scantlebury, Sivey, Anteneh, Ayres and Bloor76 but they highlight several challenges. Interviewees perceived the deep dives as overly focused on cost-cutting rather than quality, resulting in lower engagement among surgeons. Additionally, they criticised the visits for lacking meaningful dialogue and flexibility, with limited opportunity for trust staff to challenge the data or adapt recommendations to local contexts.

Changes to workflows – such as reshaping the clinician’s choice architecture in the pathology test demand management example in Section 3.2 – are essentially behavioural interventions. Such interventions can be helpful, but are not always successful, for example, when they are over-reliant on previous personal experience without sufficient adjustments to new information (a form of bias known as ‘anchoring’). However, evidence-based solutions can often be found. For example, Staats et al.Reference Staats, DS and Gino77 explored why some cardiologists failed to adjust their choice of stents when official advice said they should. They found that enabling sharing of personal stories was important in encouraging people to research additional disconfirming information.

Furthermore, initiatives to reduce variation can also increase (at least perceived) time pressure, which can, in turn, diminish performance in a range of areas.Reference Loch and Terwiesch78,Reference Tucker and Edmondson79,Reference DeDonno and Demaree80 In researching the implementation of a standardised care pathway for acute stroke care in an NHS hospital, Frangeskou et al.Reference Gittell, Fairfield and Bierbaum66 identified significant challenges. The care pathway specified the optimal sequence and timing of interventions, such as brain imaging and thrombolysis, to improve outcomes for stroke patients, but implementation was not straightforward. Operational dependencies included resources like CT scanners and emergency department staff that were not dedicated solely to stroke patients; instead, as described in Section 5, they were shared among different patient groups, including trauma and sepsis cases, leading to competition for access. Delays in brain imaging arose when radiologists had to prioritise other emergencies over stroke cases, undermining the time-sensitive requirements of the acute stroke care pathway. Additionally, the hospital’s bed management system, which reallocated beds during periods of high demand, often directed beds reserved for stroke patients to others, potentially disrupting the intended flow of care. Alongside these operational challenges, the hospital faced professional dependencies, including the need to coordinate the efforts of specialists such as emergency department doctors, radiologists, and stroke physicians. The pathway relied on these professionals working together seamlessly, but variations in their levels of expertise and engagement created inconsistencies in how the standardised process was applied. Some emergency department doctors were more committed to stroke care than others, resulting in differences in the speed and quality of care delivery. Effective communication between departments, like the emergency department and the acute stroke unit, was also crucial but often difficult to achieve, leading to delays and misunderstandings.

In response to the challenges, the hospital introduced the role of the stroke nurse practitioner as a kind of pilot to guide patients through the pathway and actively manage interactions between departments. The practitioners played a crucial role in coordinating care, often stepping in to find solutions when communication breakdowns occurred or when resources were not readily available. For instance, they sometimes had to physically track down doctors in the emergency department to ensure that stroke patients received timely assessments. Despite the stroke nurse practitioner’s efforts to navigate these complexities, the broader issues of conflicting priorities, limited resources, and inconsistent professional engagement continued to pose challenges.

7 Conclusions

Operations management, as an improvement approach, offers a range of useful analytic approaches, insights, and techniques. Parts of its toolbox feature in several of the Elements. Here, we proposed that the concept of process is valuable across multiple levels of analysis. Second, we turned to the challenges of balancing capacity and demand, showing the logic and insights of queuing theory. Exploring the concept of focus, we showed that significant benefits can be realised in narrowing healthcare by service or patient or pathway, but implementing focused approaches is often very challenging in health systems. Finally, we discussed people and process, stressing that all operations management interventions need to consider professional and team behaviours and their contexts.

Process redesign may be challenging, but simply working harder without structural change is far from cost free. The entire healthcare system, from community health to primary care, from neighbourhood centres to surgical specialists, will continue to face pressure to deliver increased output with very real resource constraints. As such, insights from operations management will continue to be of fundamental value.

8 Further Reading

Slack and Brandon-JonesReference Slack, Brandon-Jones and Burgess81 – approaching the subject from a managerial perspective, this book provides comprehensive and concise coverage of the principles and practices of operations and process management.

Vissers, Elkhuizen, and ProudloveReference Williams, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic9 – this book features both theoretical frameworks in the fields of healthcare management, operations management, and patient flow logistics, as well as a set of practical case studies.

Slack and LewisReference Slack and Lewis82 – the ideas and examples in this book illustrate how operations strategy can help organisations develop their operations capabilities by building on concepts from strategic management, operations management, marketing, and human resource management.

Hopp and LovejoyReference Lorenz, Arlt and Conze45 – this book demonstrates how to apply operations management techniques and metrics to substantially improve hospitals’ operational, clinical, and financial performance.

Loch and WuReference Loch and Wu83 – this book provides an overview of important relevant behavioural issues and their application in operations management work.

MAL wrote the initial draft of this Element. CV critically reviewed, commented, and edited the initial draft, and led on the revision. Both authors have approved the final version.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank the peer reviewers for their insightful comments and recommendations to improve the Element. A list of peer reviewers is published at www.cambridge.org/IQ-peer-reviewers.

Funding

This Element was funded by THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute, www.thisinstitute.cam.ac.uk). THIS Institute is strengthening the evidence base for improving the quality and safety of healthcare. THIS Institute is supported by a grant to the University of Cambridge from the Health Foundation – an independent charity committed to bringing about better health and healthcare for people in the UK.

About the Authors

Michael Lewis is Professor at the University of Bath School of Management, specialising in operations and supply management. Author of over 60 publications, his public policy research includes health and care services transformation and major project implementation.

Christos Vasilakis is Professor of Management Science and Fellow of the Operational Research Society (FORS). At the University of Bath, he set up and directs the Centre for Healthcare Innovation and Improvement. Working in close collaboration with clinicians and healthcare professionals, Christos develops and applies advanced analytics methods to help better plan and deliver care services. He is also interested in the evaluation of the likely impact of healthcare interventions and policy initiatives using modelling and empirical methods.

The online version of this work is published under a Creative Commons licence called CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0). It means that you’re free to reuse this work. In fact, we encourage it. We just ask that you acknowledge THIS Institute as the creator, you don’t distribute a modified version without our permission, and you don’t sell it or use it for any activity that generates revenue without our permission. Ultimately, we want our work to have impact. So if you’ve got a use in mind but you’re not sure it’s allowed, just ask us at enquiries@thisinstitute.cam.ac.uk.

The printed version is subject to statutory exceptions and to the provisions of relevant licensing agreements, so you will need written permission from Cambridge University Press to reproduce any part of it.

All versions of this work may contain content reproduced under licence from third parties. You must obtain permission to reproduce this content from these third parties directly.

Editors-in-Chief

Mary Dixon-Woods

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Mary is Director of THIS Institute and is the Health Foundation Professor of Healthcare Improvement Studies in the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at the University of Cambridge. Mary leads a programme of research focused on healthcare improvement, healthcare ethics, and methodological innovation in studying healthcare.

Graham Martin

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Graham is Director of Research at THIS Institute, leading applied research programmes and contributing to the institute’s strategy and development. His research interests are in the organisation and delivery of healthcare, and particularly the role of professionals, managers, and patients and the public in efforts at organisational change.

Executive Editor

Katrina Brown

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Katrina was Communications Manager at THIS Institute, providing editorial expertise to maximise the impact of THIS Institute’s research findings. She managed the project to produce the series until 2023.

Editorial Team

Sonja Marjanovic

RAND Europe

Sonja is Director of RAND Europe’s healthcare innovation, industry, and policy research. Her work provides decision-makers with evidence and insights to support innovation and improvement in healthcare systems, and to support the translation of innovation into societal benefits for healthcare services and population health.

Tom Ling

RAND Europe

Tom is Head of Evaluation at RAND Europe and President of the European Evaluation Society, leading evaluations and applied research focused on the key challenges facing health services. His current health portfolio includes evaluations of the innovation landscape, quality improvement, communities of practice, patient flow, and service transformation.

Ellen Perry

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Ellen supported the production of the series during 2020–21.

Gemma Petley

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Gemma is Senior Communications and Editorial Manager at THIS Institute, responsible for overseeing the production and maximising the impact of the series.

Claire Dipple

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Claire is Editorial Project Manager at THIS Institute, responsible for editing and project managing the series.

About the Series

The past decade has seen enormous growth in both activity and research on improvement in healthcare. This series offers a comprehensive and authoritative set of overviews of the different improvement approaches available, exploring the thinking behind them, examining evidence for each approach, and identifying areas of debate.