Introduction

For long-distance migrant birds, fuelling before migration is essential, while the effects of global climate change may decrease the availability of crucial food resources at fuelling or refuelling sites (Bairlein Reference Bairlein2016). A timely spring migration is especially important for high arctic-breeding waterbirds, such as wildfowl and shorebirds, which have only a short breeding season (Bairlein Reference Bairlein2016; Battley et al. Reference Battley, Rogers, van Gils, Piersma, Hassell and Boyle2005; Conklin et al. Reference Conklin, Battley, Potter and Fox2010). In this context, the study of diet provides critical information about its ecological requirements (McWilliams et al. Reference McWilliams, Guglielmo, Pierce and Klaassen2004). Understanding the composition of the diet and the underlying influential factors is crucial for developing effective conservation strategies for threatened species (Chatterjee and Basu Reference Chatterjee and Basu2018).

The Bristle-thighed Curlew Numenius tahitiensis breeds in remote Alaskan tundra, and winters on Pacific islands and atolls, from the Hawaiian archipelago to Polynesia. Like most Numeniini, numbers are declining (Pearce-Higgins et al. Reference Pearce-Higgins, Brown, Douglas, Alves, Bellio and Bocher2017) and in French Polynesia in the past two decades they have dropped by 50% (Jiguet Reference Jiguet2023). Although classified as “Near Threatened” globally, if this rate of decline was to be true globally, it would correspond to a Red List status of “Endangered”. Bristle-thighed Curlews are long-distance migrants which move latitudinally across the Pacific Ocean, performing non-stop flights for several days consecutively (Jetz et al. Reference Jetz, Tertitski, Kays, Mueller, Wikelski and Åkesson2021). Spring migration occurs in early May, involving non-stop flights to Alaska or with a stop-over on the Hawaiian Islands. To accomplish this journey, curlews must store large food reserves, often more than doubling their body mass (Marks et al. Reference Marks, Tibbitts, Gill, McCaffery, Poole and Gill2020). Fattening before spring migration is therefore crucial to ensure a successful return to breeding grounds.

Rats are thought to be the largest threat to the Bristle-thighed Curlew in the Tuamotu Archipelago (Jiguet Reference Jiguet2023). Two rat species have been introduced into Polynesia, the Pacific rat Rattus exulans and ship rat R. rattus. The former is smaller, more widely distributed, and present on many atolls where curlews are present. Rats impact native populations of lizards and arthropods (Harper and Bunbury Reference Harper and Bunbury2015) and probably deplete the overall terrestrial food resources for curlews, including marine arthropods. As an example, Jiguet (Reference Jiguet2023) reported that the southern rim of Rangiroa is now rat-infested, while curlew numbers have shrunk here since the late 1980s.

Metabarcoding is currently the most widely used method to address the taxonomic composition of environmental samples, since it allows targeted, parallel, and cost-effective identification of multiple taxa (Taberlet et al. Reference Taberlet, Coissac, Pompanon, Brochmann and Willerslev2012). Even if not all ingested organisms are equally represented in the faeces, as digestion rates vary, metabarcoding of faeces has shown to have a much higher detection capacity than any direct observation technique, and diet studies using genomic methods are therefore becoming increasingly widespread (Taberlet et al. Reference Taberlet, Bonin, Zinger and Coissac2018), providing highly accurate information about the trophic ecology of species (Cabodevilla et al. Reference Cabodevilla, Mougeot, Bota, Mañosa, Cuscó and Martínez2021; Pompanon et al. Reference Pompanon, Deagle, Symondson, Brown, Jarman and Taberlet2012).

The diet of the Bristle-thighed Curlew has been described from field observations of foraging individuals during the breeding season (Marks et al. Reference Marks, Tibbitts, Gill, McCaffery, Poole and Gill2020) and on wintering grounds, including Rangiroa atoll (Gill and Redmond Reference Gill and Redmond1992). The aim of this study was to describe diet composition and preferences in April, which is the spring pre-migratory fuelling period, using DNA metabarcoding of faeces, thereby covering an important gap in the species trophic ecology during a critical stage of its annual cycle. We aimed to acquire a detailed knowledge of the animal and plant taxa consumed, and to compare diets of curlews frequenting rat-infested versus rat-free islands, and therefore to document the potential impact of introduced rats on fuelling capacity. We also searched for a relationship between diet and fat load (body mass relative to body size).

Methods

Study area and sample collection

Faeces collection was conducted during two successive expeditions in the Tuamotu Archipelago in April 2022 and April 2023. In 2022, samples (number in brackets) were collected at the following islands: Tuanake (1), Paraoa (2), Ahunui (8), Manuhangi (8), Haraiki (6), Reitoru (5), and Rangiroa (7). In 2023, samples were collected at Manuhangi (8) and Rangiroa (20). In total, we had 65 samples and DNA was detected in 61 of them. All faeces were collected from freshly captured curlews, either directly at capture or in keeping tents at release. They were stored in small tubes filled with 70% ethanol. Of the atolls where curlews were captured, all but two, Rangiroa and Blue Lagoon (motus, i.e. islets, Taeoo and Natonato), had Pacific rats. All faecal samples were sent to the Argaly company (Sainte-Hélène-du-Lac, France) for metabarcoding analyses.

DNA extractions

DNA was extracted from the samples in a laboratory dedicated to environmental DNA manipulation. The tubes containing the faeces were first vortexed and then centrifuged for one minute at 4,500 g. The DNA in the supernatant was then precipitated by adding sodium acetate and incubating at -20°C overnight. DNA extraction was continued by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 15,000 g. After removal of the supernatant, the pellets were air-dried and then resuspended in ultrapure water and SB buffer. Washing steps were then carried out on a column using the commercial NucleoSpin Soil protocol (Macherey Nagel, Duren, Germany). An extraction control was added at each session to examine potential contamination during this stage.

DNA amplification

We used the COI_MG2 marker and the following forward and backward primers: TCHACHAAYCAYAARGAYATYGG and ACYATRAARAARATYATDAYRAADGCRTG, respectively (Tournayre et al. Reference Tournayre, Leuchtmann, Filippi-Codaccioni, Trillat, Piry and Pontier2020). Each DNA was then amplified in four polymerase chain reaction (PCR) replicates. A blocking oligonucleotide was added to the PCR reaction mix to limit amplification Bristle-thighed Curlew DNA. Each PCR replicate was uniquely identified by a combination of two eight-base tags attached 5’ to each PCR primer. These tags were used to assign sequences to the corresponding PCR replicate during bioinformatics analysis. The dilution of DNA extracts was 1:5, the number of PCR cycles was 56, and hybridisation temperature was 43°C, while median amplicon size was 133 bp (77–266 bp). Details of temperatures and times are as follows: initial denaturation 95°C 10 minutes; 56 cycles of denaturation 95°C 30 seconds; annealing 45°C 30 seconds; extension 72°C 1 minute; final extension 72°C 7 minutes. After amplification, PCR products were mixed and purified using the MinElute purification kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). High-throughput sequencing and library construction were then carried out by Fasteris (Geneva, Switzerland). Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Metafast protocol, designed to limit sequencing artefacts, and were then sequenced in Illumina (MiSeq 2*150 bp).

Sequence analysis

Raw fastq files containing paired-end reads were analysed using the suite of programs OBITools 4 (Boyer et al. Reference Boyer, Mercier, Bonin, Le Bras, Taberlet and Coissac2016) and the SumaClust clustering tool (Mercier et al. Reference Mercier, Boyer, Bonin and Coissac2013) according to the following sequential procedure: assembling paired-end reads (obipairing command, option-min-identity = 0.8); data demultiplexing, i.e. assignment to the original PCR replicate on the basis of the 5’ tag combination of the PCR primers (obimultiple commandx); dereplication of assembled reads (obiuniq command); basic filtering of low-quality reads (with at least one N in the sequence), reads observed only once in the data set, and reads whose length does not belong to the length range observed in silico (obigrep command); clustering of 97% similar sequences (SumaClust); selection of the most abundant sequences as cluster centres, and addition of the abundances of sequences in the same cluster (internal python script); selection of clusters with at least 10 reads in at least one PCR replicate (internal python script); taxonomic assignment using a sequence reference database (obitag).

The reference database is built from sequences publicly available on the GenBank release 249, using the following procedure: in silico PCR with PCR primers, allowing a maximum of three mismatches per primer (ecopcr program; Ficetola et al. Reference Ficetola, Coissac, Zundel, Riaz, Shehzad and Bessière2010); dereplication of the resulting sequences (obiuniq command); sequence filtering to retain only sequences assigned to at least family level (obigrep command).

Sequence filtering

The R package metabaR (Zinger et al. Reference Zinger, Lionnet, Benoiston, Donald, Mercier and Boyer2021) was used to remove from the data set artefactual sequences present in low abundance in the metabarcoding data, but which may influence the ecological conclusions we can draw from them (Calderón-Sanou et al. Reference Calderón-Sanou, Münkemüller, Boyer, Zinger and Thuiller2020). More specifically, we eliminated molecular operational taxonomic units (MOTUs) that are too dissimilar from the sequences in the reference database (obitag_bestidentity threshold <0.85), as these are potential chimeras; MOTUs with maximum abundance in at least one negative control, as these are potential contaminants (contaslayer function “max” method); MOTUs with a relative frequency of <3% within a PCR replicate, as these are likely to be artefacts generated during sequencing library production, such as “tag jumps” (tagjumpslayer function; Schnell et al. Reference Schnell, Bohmann and Gilbert2015); PCR replicates with sequencing coverage <100 sequences. The remaining PCR replicates were aggregated by sample, and finally, only MOTUs observed more than 10 times in a sample were kept, otherwise they were considered absent in that sample.

Blocking oligonucleotide

A MOTU was identified in silico for Bristle-thighed Curlew in the region targeted by the COI_MG2 primers. The most interesting blocking oligonucleotide in silico was defined on the forward side based its Tm (75.6°C vs 53.9–66.6°C for the forward primer and 56.4–70.3°C for the reverse primer), its specificity, and its thermodynamic properties. Specificity tests showed that the blocking oligonucleotide blocked not only the curlew but also 100 other bird taxa (Aves class) and two taxa of sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea class), which should have no impact on the study of the diet of the species of interest here. The qPCR amplification tests for the COI_MG2 marker in the presence of the blocking oligonucleotides validated their efficiency, as the output cycles of the amplification curves were then delayed compared with amplifications in the absence of the oligonucleotides.

Quality controls

Various controls were introduced at each stage of the protocol to detect any contamination and improve the interpretation of the results. For each PCR replicate, the controls performed were four negative extraction controls, three negative PCR controls, two positive controls, and a total of 32 bioinformatic controls. The positive controls correspond to DNA from water and soil samples previously sequenced by Argaly and which gave appropriate results for the study markers. The success of the amplifications and purifications was verified on 2% agarose gel (E-Gel Power Snap, Invitrogen®).

MOTUs

We achieved a mean coverage of 64,375 reads per sample (min: 204; max: 188,017). On average, diet reads accounted for 42.94% of the total reads and concerned 38 samples. Diet reads were classified into 119 unique MOTUs: 8 MOTUs of plants, 105 MOTUs of arthropods, 3 MOTUs of annelids, 1 MOTU of nemerteans, 1 MOTU of molluscs, and 1 MOTU of Chordata (gecko). The identified taxa are listed in the Supplementary material Table S1. The remaining reads (not counted as diet) mostly belonged to DNA from the host species itself, i.e. primates, parasites, proteobacteria (probably environmental contamination), and low-quality sequences that could not be accurately identified.

Comparisons of samples

We compared the distribution of the numbers of MOTUs (for taxa with MOTUs >2, so arachnids, insects, decapods, and plants) and the number of reads (for the same groups) between atolls hosting introduced Pacific rats and rat-free islets of Rangiroa, using chi-square tests. We also performed a compositional analysis with a PERMANOVA with the vegan R-package and the “adonis2” function, with the default Bray–Curtis index, grouping MOTUs at the class taxonomic level, but separating Blattodea and other insects, and terrestrial and marine crabs.

For 13 of the 38 samples with diet reads, we knew the individual bird’s identity. The other samples were collected from a restraint tent where several individuals were placed. The faeces were collected at capture and ringing when the bird’s body mass was recorded, so we looked for a potential Pearson’s correlation between the number of MOTUs (a measure of richness) or the number of reads and the body mass of a bird relative to its size. To obtain an index of sized body mass, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using three biometric measures (wing, bill, and tarsus lengths) and the body mass was regressed against the coordinates of the individuals against the first principal component, considering the individual residuals of this linear relationship as an index of the body mass of a bird relative to its body size. The PCA was performed with the “princomp” function in R.

Results

General fuelling diet

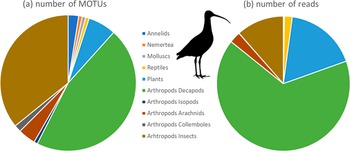

The proportions of MOTUs and reads attributed to the main identified taxa, namely annelids, nemerteans (aquatic ribbon worms), molluscs (Nerita sea snails), reptiles (Lepidodactylus gecko), plants (Magnoliopsida), and various arthropods, decapods (coastal, terrestrial, and hermit crabs), isopods (woodlice), arachnids, collembola, and insects (Blattodea, Diptera, Orthoptera, Lepidoptera, Hymenoptera, and Psocoptera) are presented in Figure 1. In terms of richness (MOTUs), the main groups in the diet were crabs (45.8%) and insects (35.8%), and crabs represented 66.1% of reads, followed by plants (17.4%), and insects (11.5%).

Figure 1. Number of (a) MOTUs (a measure of richness) and (b) reads (a measure of abundance) of the main taxa present in the diet of Bristle-thighed Curlews in April. Taxa represented here are Annelida, Nemertea, Mollusca, Chordata (Lepidosauria), Streptophyta (plants), and Arthropoda (Malacostraca including Decapoda and Isopoda, Insecta, Collembola, and Arachnida).

Some crabs were identified to species or genus: (1) two medium-sized shore crabs, Polynesian grapsid crab Pachygrapsus fakaravensis (representing 30.9% of crab reads) and Grapsus albolineatus; (2) two hermit crabs, the Indonesian hermit crab Coenobita brevimanus and the strawberry hermit crab Coenobita perlatus (20.7% of decapod reads); (3) a large terrestrial crab, the tupa Cardisoma carnifex (14.6% of decapod reads); (4) a fiddler crab Gelasimus sp.

Within insects, most reads concerned Blattodea of the genus Pycnoscelus (sand-dwelling burrowing cockroaches, 68.0% of reads), followed by Diptera (27.4%, including Calliphora vicina, the introduced bluebottle), then orders and taxa of marginal occurrence with Psocoptera (2.1%, including Polypsocus sp., a hairy-winged barklouse), Lepidoptera (1.2%, Ditrysia and Obtectomera clades), Orthoptera (1.1%, only Gryllodes sp., crickets), and Hymenoptera (0.2%, Apis mellifera and Tapinoma melanocephalum, the ghost ant, introduced to French Polynesia).

We also obtained specific identification for one reptile, the mourning gecko Lepidodactylus lugubris, and one mollusc, the sea snail Nerita undata.

Consumed plants were all Magnoliospids, with three main identified families: Arecaceae (coconut trees, representing 52.2% of plant reads), Rubiaceae (Rubioideae) (flowering plants, 44.8%), and Nyctaginaceae (2.6%).

Rat-infested and rat-free islands

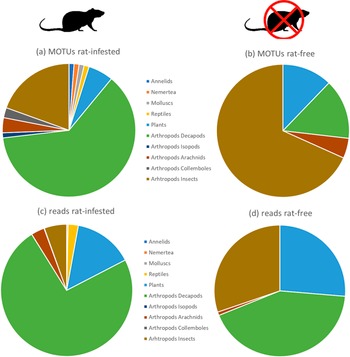

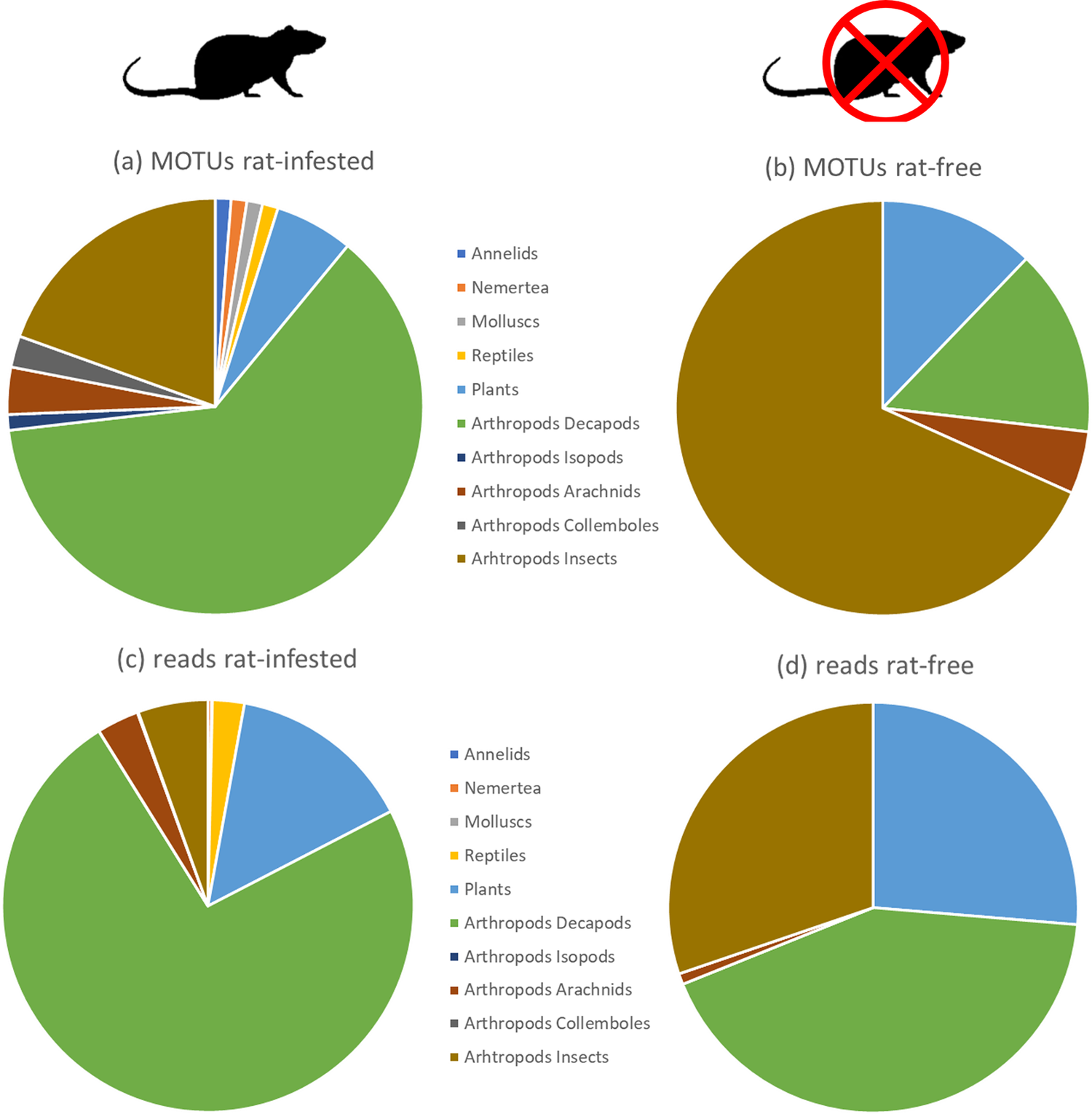

There was a significant difference between the distributions of MOTUs among the main taxa (see Figure 2) for samples collected on rat-infested and rat-free islands (chi-square = 31.76, df = 3, P <0.001). The number of MOTUs was higher on rat-infested islands, indicating a more diverse diet, with 62.2% related to crabs, and a large abundance of crabs in the diet, representing nearly 73.7% of reads. On rat-free islets, the diet displayed a higher richness in insects (68.3% of MOTUs) with more plants (12.2%), and a balanced abundance between three taxa (reads; crabs 42.6%, insects 30.2%, and plants 26.3%). The diet on rat-free islands consisted mainly of Pachygrapsus crabs and Pycnoscelus cockroaches, while the diversity of all arthropods was higher on rat-infested islands.

Figure 2. Proportions of (a and b) MOTUs (a measure of richness) and (c and d) reads (a measure of abundance) of the main taxa present in the diet of Bristle-thighed Curlews in April. Panels (a and c) for samples collected on rat-infested atolls, and (b and d) for samples collected at rat-free islets. Taxa represented here are Annelida, Nemertea, Mollusca, Chordata (Lepidosauria), Streptophyta (plants) and Arthropoda (Malacostraca including Decapoda and Isopoda, Insecta, Collembola, and Arachnida).

There was a significant difference between the distributions of reads among taxa for samples collected on rat-infested and rat-free islands (chi-square = 238491, df = 3, P <0.001), with fewer reads for crabs, and more reads for insects and plants on rat-free islands.

Using the PERMANOVA, we found a significant compositional difference in the diet between rat-infested and rat-free islands (F1,36 = 2.40, P = 0.02). We also tested for homogeneity of groups dispersion (rat presence; F1,36 = 0.64, P = 0.43).

Diet and body mass

For the 13 faeces samples where the identity of the individual bird was known, there was no significant correlation between individual residual body mass and the number of MOTUs (r = -0.258, P >0.9) or of reads (r = -0.188, P >0.5).

Discussion

The fuelling diet of Bristle-thighed Curlew

The fuelling diet of Bristle-thighed Curlew is diverse and includes plants (probably seeds) and invertebrates, mainly crabs and insects, some arachnids, and a few worms, snails, and lizards. In terms of richness, crabs represent nearly half of the diet, rising to two-thirds in terms of abundance. Overall, prior to long-distance spring migration, fuelling depends mainly on coastal and terrestrial crabs, especially the grapsid Pachygrapsus fakaravensis. This is a medium-sized crab, common on the reefs in the Tuamotu Archipelago.

Another main component of the fuelling diet is insects, especially the Surinam or greenhouse cockroach Pycnoscelus surinamensis. This sand-burrowing blattid is common in the sandy soils of the coconut plantations and native reef forests, where curlews forage during the day. This introduced species is a common plant pest originating in the Indomalayan realm that has spread to tropical and subtropical regions around the world. Its populations are almost exclusively female, and it reproduces through parthenogenesis.

Finally, plant material – probably in the form of seeds – is the third main component of their diet, of which coconut is the most conspicuous element. This is of course a commonly planted tree in the Tuamotu Archipelago, and curlews probably consume fallen flowers and very small fruits, or the pulp of fallen large coconuts that have broken open. Another explanation could be that curlews ingest coconut DNA while grasping food from dead wood or soil in coconut groves, or while ingesting insects or terrestrial crabs that have themselves ingested coconut pulp or dead wood (Poupin Reference Poupin2005). Regardless of whether the consumption of coconut was intentional or not, plant DNA appears in the metabarcoding analysis suggesting plants constitute part of the birds’ diet during their spring fuelling. As a comparison, from the stomachs of 14 Bristle-thighed Curlews collected on Rangiroa atoll, Mougin and Stockmann (Reference Mougin and Stockmann1969) reported that 7 contained vegetation, 5 had crustaceans, 4 had insects, and 1 each held gasteropods and a scorpion. Therefore, the presence of coconut DNA identified by metabarcoding is not surprising – while the frequencies of the other taxa reported here are proportionate to those found by Mougin and Stockmann (Reference Mougin and Stockmann1969).

A rat-related diet

The diet of the curlews on rat-infested islands had a different composition from those that were rat free. The diet was also more diverse on rat-infested islands, whereas as mentioned above, on rat-free islands it comprised mainly grapsid crabs, cockroaches, and coconut. We might have expected a more diversified diet in the absence of rats, as these invasive mammals eat almost any type of plant and invertebrate – marine or terrestrial – which must reduce the availability of many taxa for other consumers (Harper and Bunbury Reference Harper and Bunbury2015), including curlews. In fact, we found the reverse to be true. A possible explanation for this is that where the optimal fuelling diet of grapsid crabs, sand-dwelling cockroaches, and plants (probably seeds or pulp of coconuts) is not available due to resource depletion by introduced rats, curlews diversify their diet to include a larger variety of other taxa. This can include annelids, springtails, woodlice, crickets, ants, butterflies and moths, snails, and lizards. The observed difference also suggests that rats reduce the availability of coastal grapsid crabs for curlews, hence they forage and feed on coastal parts of the reef. Indeed, during nocturnal observations with thermal binoculars on the Tuamotu islands visited in 2021–2025, rats were often recorded on the reef, away from any vegetation, (personal observation).

Despite obvious differences in richness and abundance of diet items attributable to rat infestation, we failed to find a link between the fuelling status of a bird and the richness or abundance of items in its faeces. This could be due to a small sample size (n = 13), or the potential variability of DNA found in individual droppings, as compared with a global analysis of items found in a merged set of samples. Furthermore, read counts can be influenced by the affinity of the marker used, and thus not fully reflect real item abundance in the diet (Piertney Reference Piertney, Mateo, Arroyo and García2016). Such affinity bias can be evaluated (González del Portillo et al. Reference González del Portillo, Cabodevilla, Arroyo and Morales2024), but this was not done here, which may also explain the failure to find a relationship between fuelling status and the dietary components identified by metabarcoding. Owing to the small number of analysed samples, it was not possible to study the occurrence frequencies of dietary elements and to consider recovery biases (Deagle et al. Reference Deagle, Thomas, McInnes, Clarke, Vesterinen and Clare2019).

Conservation of curlews

It is suggested here that rats reduce food availability for curlews, and particularly the availability of prey that may contribute most to optimal fuelling for migration. To confirm this, direct measures of food availability in rat-infested vs non-infested atolls are needed to provide evidence of the differential nutritional value of identified dietary components (see Zurdo et al. Reference Zurdo, Gómez-López, Barrero, la Rosa D, Gómez-Catasús and Reverter2023 for an example). Identifying the impact of rats on the feeding and fattening strategy of migratory curlews should help define measures to improve the species’ conservation status. Our findings highlight the importance of managing invasive rats to maintain key food resources not only for native birds but also for migratory ones. Further research on prey availability and their relative nutritional quality across islands is recommended to inform conservation strategies. The analysis of tracking data obtained at Rangiroa in 2021 also reports that curlews forage and feed preferentially on rat-free islets (Lorrilliere et al. Reference Lorrilliere, Mermilliod, Wikelski, Blanc and Jiguet2025).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270925100300.

Acknowledgements

The author declares to have no competing interest, and thanks three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. Research conducted on Bristle-thighed Curlew in French Polynesia, including captures and faeces sampling, benefits from two decrees of the Ministry of Culture and Environment (n°3933 MCE/ENV 27 March 2020, and N°7954 MCE/ENV 22 July 2022). Captures are also authorised by the CRBPO under the program reference PP1099. I am highly indebted to the French Navy, ALPACI, and the crew of the Bougainville vessel, who made the expeditions possible and successful in 2022 and 2023. I am indebted to the NGO SOP-Manu, working hard for bird, biodiversity, and island conservation in Polynesia. Taurama Sun was a fantastic host for my research team on his motu at the Blue Lagoon of Rangiroa. I thank Anne-Christine Monnet who helped with running the PERMANOVA. I greatly thank field workers who contributed to faeces sampling: Ludwig Blanc, Pierrick Bocher, Anne Dozières, Pierre Fiquet, Jérôme Fournier, Méryl Gervot, Lorrillière, Sébastien Pagani, Pierre Rousseau, Frédéric Capron, and Julien Guitard. This report is a product of the Kivi Kuaka project, funded by Ministère des Armées, Ministère de la Transition Ecologique, Office Français de la Biodiversité, Agence Française de Développement, and Météo France.