Introduction

Numerous factors influence patients’ access to pharmaceuticals in the U.S. Recent media coverage of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) focuses on their negative impact on patients. This review seeks to provide ID clinicians with an overview of PBMs, review PBM practices, models, funding, and potential impacts on ID-specific care areas. Finally, we provide general guidance for ID clinicians contending with PBMs to ensure efficient and equitable care given present uncertainties of federal policies impacting prescription drug coverage.

Background

Prescription drug benefits in the US involve a complex interplay of pharmaceutical manufacturers, wholesalers, group purchasing organizations, providers, pharmacies, health plans, PBMs (and their rebate aggregators), and patients Reference Hernandez and Hung1,Reference Frieden2 (see Figure 1). PBMs have expanded their practices and reach since their emergence in the late 1960s–1970s and now administer pharmaceutical benefits for more than 92% of Americans covered under private, union, and governmental insurances. Reference Mattingly, Hyman and G3,Reference Keisler-Starkey, Bunch and Lindstrom4 Three Fortune 500 companies—CVS Caremark, Express Scripts/Cigna, and OptumRx/UnitedHealthcare—control roughly 80% of PBM-processed prescription claims in the US, wielding significant influence over drug benefits and pricing. Reference Frieden2,Reference Fein5 Outside the US, public institutions manage pharmacy services, making PBMs a uniquely American entity. Reference Lyles6

Figure 1. The flow of products, services, and payment in the US pharmaceutical care system. Reference Fein99

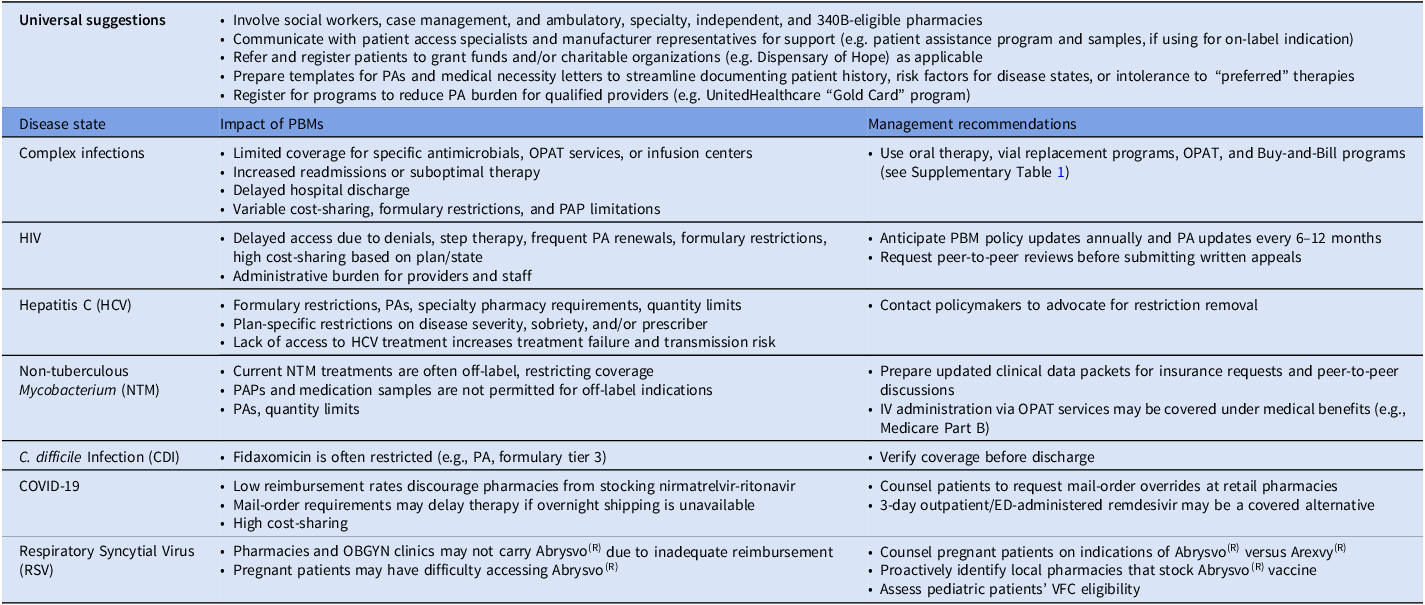

PBMs manage a variety of medications, from generic antimicrobials to high-cost specialty drugs like hepatitis C direct-acting antivirals (DAA). Access is shaped by several factors (see Table 1). Reference Mattingly, Hyman and G3,Reference Goldberg7 Rebates and contracting determine formulary inclusion, pricing models, and dispensing reimbursement. Reference Hernandez and Hung1,Reference Mattingly, Hyman and G3 As a result, PBMs influence drug pricing dynamics—affecting manufacturer sales volume via formulary access, pharmacy reimbursement, and patients’ out-of-pocket costs through tiering and utilization management. Reference Mattingly, Hyman and G3 While PBMs are integral to US healthcare, opaque denial, exclusion, and approval rationale create access barriers, particularly in ID and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care. Reference Mattingly, Hyman and G3,Reference Lyles6–10

Note. ADAP, AIDS Drug Assistance Program; ADR, adverse drug reaction; ED, emergency department; HCV, hepatitis C virus; NTM, non-tuberculous Mycobacterium; OBGYN, obstetrics/gynecology; OPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy; PA, prior authorization; PAP, patient assistance program; PBM, pharmacy benefit manager; VFC, Vaccines for Children program.

Media view and innovations

Concerns about conflicts of interest and regulatory gaps are underscored by vertical integration, wherein major health insurers and pharmacy chains own PBMs and control multiple medication fulfillment stages Reference Mattingly, Hyman and G3,11 (see Figure 2). Administrative delays are observed due to utilization management strategies, such as prior authorization (PA) for non-covered or off-label prescriptions, step therapy, quantity limits, high cost-sharing despite formulary coverage, and outright denials for costly, yet necessary, anti-infectives (see Table 1). Reference Morgan12–Reference Robbins and Abelsen14 Across the three largest PBMs, 2020 formulary exclusion lists collectively barred over 800 medications, citing generic or “therapeutically similar” formulary alternatives—despite potential nonequivalence in some clinical scenarios. Reference Fein5 In 2023, the HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute filed a complaint that certain Texas health insurers were offering “substandard and discriminatory plans that violate the Affordable Care Act” as 34%–50% of approved HIV drug formulations were not covered. Reference Schmid15 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which regulate PBMs, are investigating these practices. Reference Lichtenstein8,16

Figure 2. Vertical integration in the US pharmaceutical care system. Reference Fein99

Recent industry disruptors have emerged like Mark Cuban’s CostPlus Drug Company and Amazon Pharmacy, promoting discounts to compete with insurers. Both provide generic medicines for cheaper-than-retail costs through direct negotiations and intermediary removal. Reference Murphy17 These companies augment the US drug supply-chain, particularly in the setting of drug shortages and limited manufacturer antimicrobials. A New York City-based physician described a successful collaboration with CostPlus Drug to secure affordable penicillin G injections during a shortage and subsequent price hikes. Reference Sax18 Today, these injections cost upwards of 500 to 800 USD. Patients increasingly use alternatives to conventional pharmaceutical insurance, such as the discount card companies GoodRx and SingleCare, to cover antimicrobials. Other novel approaches to healthcare coverage include health-sharing companies such as CrowdHealth, in which members essentially pay into the company’s fund pool to cover co-members’ medical costs. Reference Semuels19

Negative public sentiment toward health insurers, and PBMs by association, was observed during the 2024 shooting of UnitedHealthcare CEO, Brian Thompson. Reference Gulati and Beard20 Many shared personal struggles of exorbitant costs for care or denied coverage for pharmaceuticals and services. Opinion writers suggested the shooting should serve as a “turning point” for health insurers due to the dramatic antagonistic shift in public opinion regarding insurance companies prioritizing shareholders over patients. Reference Potter21–24

Impact of PBMs on specific care areas

Herein, we present illustrative, fictional, yet relatable ID cases where patients were unable to receive preferred or standard-of-care therapies, or faced significant treatment delays, resulting in poor outcomes such as treatment failure, readmission, or prolonged hospitalization.

Complex bacterial infections

A 41-year-old undomiciled female with substance use disorder presented to the emergency department with sepsis and was diagnosed with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia complicated by tricuspid valve endocarditis. She was treated with IV cefazolin and underwent valve replacement 4 weeks into admission. To expedite hospital discharge, the ID team recommended off-label use of IV dalbavancin on the day of discharge, followed by a second dose 1 week later in the outpatient infusion clinic. Reference Turner, Zaharoff and King25,Reference Turner, Hamasaki and Evans26 Unfortunately, dalbavancin was not covered by her insurance and would have cost the patient 3,000 USD out of pocket. Cefadroxil was also not covered and had an exorbitant out of pocket cost. The patient was ultimately discharged on amoxicillin 1 g every 6 hours and rifampin 600 mg every 12 hours which she found intolerable due to a high pill burden. She could not complete her treatment and required readmission for conventional IV therapy.

This vignette reinforces challenges with rigid formulary restrictions in the transitions of care. Dalbavancin and cefadroxil’s coverage denial interfered with a plan designed to overcome a vulnerable patient’s barriers to follow-up. Although outpatient cefazolin may have been an option, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) is often hindered by: limited insurance coverage of certain antimicrobials and nursing services, care coordination further delaying hospital discharge, and adverse event and infection risk from prolonged parenteral access (see Table 1). High dose amoxicillin was selected as a compromise, though literature on use in deep-seated MSSA infections is sparse. Furthermore, delays in receiving antimicrobials and prescription of agents with frequent dosing can lead to non-adherence and subsequent infection relapse, disease progression, rehospitalization, and death. From the PBM’s perspective, the goal of restricting and preventing non-formulary medication use was achieved.

Complex fungal infections

A 66-year-old male Medicare beneficiary with a foot mass and worsening pain was diagnosed with skin-soft tissue infection and osteomyelitis. Biopsy cultures grew Fusarium spp. The ID team planned to treat with posaconazole delayed-release tablets for 6 weeks, which required a PA. The PA was denied as posaconazole was only approved for invasive aspergillosis. Voriconazole was instead prescribed and approved. Two weeks into treatment, he became nauseous, dizzy, and experienced visual hallucinations. Voriconazole could not be continued due to fall risk and treatment was stopped early, leading to infection relapse and rehospitalization.

Formularies may restrict access to the already limited outpatient antifungal options. While patient assistance programs (PAPs) are available, off-label indications, despite adequate evidence, may limit PAP usability.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

A 42-year-old male accountant with HIV and stage 2 chronic kidney disease (CKD), was virologically suppressed on rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (TAF). He first utilized the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) to cover copays, then a manufacturer assistance card when his salary surpassed the ADAP income cutoff. In March 2025, he was told there would be a 2000 USD copay for his ARVs reaching the 6,000 USD annual maximum limit after two refills. His employer-sponsored insurance changed its antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage schema, making the patient responsible for 80% coinsurance. Nonprofit, safety-net organizations were unable to assist due to depleted funding, so his HIV physician modified his regimen to rilpivirine and emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). The patient filled rilpivirine through a copay assistance card and 90-day supplies of generic emtricitabine/TDF through CostPlus Drugs for 21 USD.

The example above illustrates PBMs’ ART cost-containment through step therapy (trial of preferred formulary medication prior to approval of more expensive or non-formulary agents) and strict approval criteria. Emtricitabine/TAF as treatment and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been subject to both strategies. PBMs may require initial or exclusive use of generic TDF plus emtricitabine or lamivudine. PBMs may reserve emtricitabine/TAF for those with laboratory-proven CKD. 27,28 Medications coadministered with ART, such as pitavastatin for cardiovascular risk reduction, are often on non-preferred tiers despite strong recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and HIV Medicine Association. Reference Horberg, Thompson and Agwu29

PBM policies may impede neonatal discharge planning. Neonates at risk for HIV acquisition require HIV therapy, such as raltegravir oral suspension, available only as a brand product. Neonatal ART may be subject to PAs or prohibitive out-of-pockets costs. These barriers can delay treatment initiation and place undue burden on caregivers.

FDA labeling may also be used in approval criteria. For instance, a patient with multi-drug resistant HIV struggling with non-adherence due to high pill burden may be denied lenacapavir because their viral load is suppressed, given that FDA approval criteria specify an HIV RNA ≥400 copies/mL for at least 8 weeks. 30 Other PBM cost management strategies such as mandatory mail-order can also be detrimental to people with HIV due to stigma and privacy concerns. An evolving standard of care, frequent treatment guideline updates, hard-fought wins from advocacy groups, and political pressure have eased some constraints on HIV management.

PBMs also profit significantly from ARTs. Between 2017–2022, PBMs generated 521 million USD in dispensing revenue in excess of National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC) on specialty generics. Notably, 63% of drugs marked up between 300–1,000% were ARTs. Lamivudine was marked up 276% and 306% for commercial and Medicare claims in 2022, respectively. Emtricitabine/TDF was marked up greater than 1,000%. 31 These markups also extend to hepatitis B therapy, including entecavir, marked up >1,000%. 32 For global comparison, medications such as tenofovir and lamivudine in the US are on average 4.71 times the prices in the non-US G7 countries and Australia and cheaper still in South Asian nations. Reference Yao, Ying, Jesudian and Congly33

PrEP access has historically been challenging, particularly for commercially insured patients, despite an “A” rating from the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF). 34–Reference Dean, Nunn and Chang36 One economic burden study found average all-cause costs for commercially-insured adults starting PrEP were 1761 USD/patient/month, with 71% representing pharmacy costs. Reference Chen, Donga, Campbell and Taiwo37 Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), private insurances were required to fully cover therapies with an USPSTF “A” rating, including PrEP. Ongoing legal challenges, such as Braidwood Management, Inc. v Becerra, threaten to nullify those provisions, leading to increased patients’ out-of-pocket costs, PBM spread pricing, prescription abandonment rates, and risk of HIV acquisition. Reference Dean, Nunn and Chang36 Reassuringly, in 2024, CMS began covering PrEP, hepatitis B screening, and up to eight counseling visits and HIV screening tests annually.

Hepatitis C

A 59-year-old male with chronic hepatitis C infection (F2 liver fibrosis staging) was referred for treatment. He had a history of myocardial infarction and was maintained on atorvastatin due to intolerance to other statins. An initial sofosbuvir/velpatasvir prescription was denied as glecaprevir/pibrentasvir was preferred. After requesting a peer-to-peer, the provider missed the callback two days later. When the provider returned to work, the 72-hour peer-to-peer window passed, requiring formal appeal. Since an expedited approval was not specifically requested, the sofosbuvir/velpatasvir approval letter was not received until 90 days later.

DAA therapy significantly decreases mortality, decompensated cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma compared to non-treated individuals.,38–Reference Ogawa, Chien and Kam40 In contrast with guideline recommendations that all patients receive treatment, some Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial plans have requirements based on disease severity (eg: cirrhosis, fibrosis), patient sobriety, and/or provider specialty. Reference Bhattacharya, Aronsohn, Price and Lo Re41 Additionally, most PBM formularies categorize DAAs as specialty drugs, dissuading use through PAs, quantity limits, and pharmacy steering. 42 The State of Hepatitis C website publicly grades State Medicaid programs on hepatitis C drug accessibility. 43 When States eased or eliminated coverage restriction, DAA use increased by 966 treatment courses/100,000 Medicaid beneficiaries each quarter, Reference Davey, Costello and Russo44 increasing progress toward hepatitis C elimination in the U.S.

Nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) infections

A 54-year-old female with COPD was hospitalized with macrolide-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary infection. Her provider prescribed imipenem-cilastatin, tigecycline, linezolid, and completed paperwork to obtain clofazimine. Despite clinical stability, she remained inpatient for an additional week for treatment pending outpatient PA. While waiting, she developed a line-associated venous thromboembolism, prolonging hospitalization.

Non-tuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) infection management remains challenging for patients and prescribers and medication accessibility varies greatly depending on chosen therapy. Reference Daley, Iaccarino and Lange45 Several FDA-approved drugs are arduous to obtain due to PAs and quantity limits set by PBMs (eg: linezolid, imipenem, and omadacycline) and the clofazimine acquisition process is daunting due to manufacturer special access programs or FDA investigational new drug applications. 42,46,47

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI)

A 73-year-old male with benign prostatic hypertrophy received 4 days of ertapenem for ESBL-E. coli bacteremia. On hospital day 4, he developed diarrhea and was diagnosed with C. difficile. He was treated with fidaxomicin while admitted, and discharged on day 7 of ertapenem with a prescription for 6 more days of fidaxomicin. Unfortunately, PA for fidaxomicin was not obtained and his retail pharmacist could not reach the physician of record to obtain PA or change the prescription. Unfortunately, the patient’s diarrhea worsened and he required readmission.

Guidelines for C. difficile infection recommend fidaxomicin over vancomycin because of its twice-daily dosing and lower recurrence rates. Reference Johnson, Lavergne and Skinner48 Despite this, access remains limited. One study of Medicare beneficiaries found that fidaxomicin was included on formulary for 84.1% of enrollees. However, only 1.1% of patients had “broad access” to the agent (on formulary, Tier 1 or 2, no step therapy or PA required). Reference Buehrle and Clancy49 Currently, fidaxomicin is classified as Tier 3 on most PBM formularies, with some still requiring PAs. 42.46,Reference Boton, Patel and Beekmann50,51

Coronavirus/SARS CoV2 (COVID-19)

Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, approved for patients at high risk for progression to severe COVID, is currently covered by private health insurance and Medicare plans. However, some PBM reimbursement rates are below wholesale acquisition cost (WAC), dissuading pharmacy stocking and delaying initiation. Additionally, some PBMs have mail-order requirements, conflicting with recommendations to receive nirmatrelvir-ritonavir within five days of symptom onset. 52,53 For patients with cost-prohibitive copays or no coverage, Pfizer’s PAXCESS program offers co-pay assistance and access to the US Government Patient Assistance Program. 54 Leveraging such resources may improve access to care and reduce treatment delays.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines and nirsevimab decreased 2024–2025 RSV-associated hospitalizations compared to 2018–2020 pooled rates by 28%–43% among infants. Reference Patton, Moline and Whitaker55 Because of such strong data and as immunizations are required by the ACA, PBMs cover nirsevimab widely, with no out-of-pocket costs through private health insurance and Medicare plans. 56 Additionally, nirsevimab is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and Centers for Disease Control in Prevention (CDC) in infants and is available through the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program for eligible participants. 57–59

The RSV immunizations, Arexvy(R) and Abrysvo(R), are recommended for all adults ≥75 years and adults 60–74 years at increased risk for severe RSV disease. Reference Britton, Roper and Kotton60 Abrysvo(R) is also indicated for pregnant persons at 32–36 weeks’ gestation during RSV season. Reference Fleming-Dutra, Jones and Roper61 Both immunizations are widely covered by PBMs managing private health insurances and Medicare plans for eligible patients. 62,63

PBM coverage of nirsevimab, Arexvy(R), and Abrysvo(R) are key factors in determining patient access and pharmacy or medical office reimbursement. Some obstetrics and gynecology offices may not stock Abrysvo(R) due to associated costs and risk of waste. Pharmacies stock these vaccines interchangeably based on PBM reimbursement, posing a potential barrier for pregnant persons to receive Abrysvo(R). Reference Rosenthal64

Pharmacy perspective

Community pharmacies nationwide are succumbing to thinning operational margins caused by PBM reimbursement rates below WAC for nearly 80% of prescriptions. Aggressive clawback, or postpayment recoupment, practices hamper financial viability. Reference Knox, Gagneja and Kraschel65 Additionally, financial incentives and network exclusions have steered patients to specific pharmacies, hampering unaffiliated pharmacies’ business and straining long-standing relationships between patients and pharmacists. Reference Knox, Gagneja and Kraschel65 The recently publicized bankruptcy of Rite-Aid and Walgreens’ privatization, in part due to declining reimbursement rates, indicate that even industry giants are not immune to this changing landscape. Reference Cervantes66,Reference Constantino67 Pharmacists became increasingly vocal in their concerns culminating in the “Pharmageddon” walkout in late 2023. Reference Lichtenstein8

Diminishing reimbursement has especially shuttered independent pharmacies, creating “pharmacy deserts”—areas of the US where patients do not have reliable access to a pharmacy within a reasonable distance. Reference Garbato68,69 Rural areas of the US are particularly impacted. An estimated 16.1% of rural pharmacies serving over 45 million Americans closed between 2003 and 2018. Reference Knox, Gagneja and Kraschel65,Reference Garbato68 Nearly 800 ZIP codes that previously had at least one pharmacy in 2015 now have none, making antimicrobial access more complex and less reliable, particularly for socioeconomically disadvantaged areas. Reference Garbato68,Reference Abelson and Robbins71 Pharmacists in these communities were often the only accessible healthcare professional, providing antimicrobials, maintenance medications, point-of-care viral testing, immunizations, and even supporting ART adherence. Reference Hamstra70

In 2020, the US Supreme Court’s decision in Rutledge v Pharmaceutical Care Management Association allowed States to regulate PBMs, drug pricing, and reimbursement rates. In Arkansas, where the Rutledge case originated, statutes require PBMs to reimburse pharmacies at or above their acquisition cost and a subsequent law prohibits PBMs from operating pharmacies in the State. Reference Knox, Gagneja and Kraschel65,Reference Khawaja and Kazi72 This may bolster rural and independent pharmacies’ crucial role as vaccine-preventable illnesses surge in these areas. Reference Vrbin73 PBM reforms are currently under consideration in Congress to prohibit pharmacy clawback practices, standardize drug acquisition costs, require full rebate pass through in Medicaid managed care, set transparent pharmacy reimbursement standards, as well as “spread pricing,” the PBM practice of charging payers more than they pay pharmacies for medications and keeping the difference as profit. Reference Frieden2,74

Patient perspective

High costs and restricted access can lead to dissatisfaction and negative outcomes, ranging from treatment delays to death. Reference Kandiah, Altamimi, Shaeer, Holubar and Wagner75 One tragic example involves a father and son who were both asthmatics maintained on the same chronic inhaler. Suddenly, their pharmacy benefits changed, the inhaler was no longer covered, and a novel dosage form was the preferred agent on PBM formulary. The father, a patient at an independent pharmacy, discussed options with his pharmacist who helped his physician navigate PAs and successfully prescribe the treatment. The son, a patient at a large retail pharmacy, was not afforded the same guidance and was told the copay would be approximately 500 USD. Tragically, in the subsequent days, the son died of an acute exacerbation of his chronic condition. The father now educates patients and providers about PBMs and advocates for PBM reform. 76

PBMs and future healthcare policy landscape

Prescription drug pricing and PBM practices are under intense public and federal scrutiny with proposed legislation that may reshape patient access. However, other federal actions (proposed in 2025, prior to publication of this article) could lead to higher costs and supply constraints for providers and greater barriers for patients

-

1. Tariffs, Coverage Loss, and “The Bill”: The proposed 200% tariffs on imported pharmaceuticals, combined with sweeping Medicaid cuts in the newly enacted One Big Beautiful Bill Act (“The Bill”), could significantly disrupt patient access to essential medications—especially sterile injectable generics and antimicrobials reliant on global supply chains and low margins. Reference Dyrda77–Reference Murphy80 Persistent shortages of critical antibiotics may worsen due to procurement challenges and cost escalation. Additionally, The Bill includes new Medicaid eligibility restrictions that are projected to remove coverage for nearly 12 million people, shifting more uninsured individuals, low-income persons, and rural populations to emergency and safety-net systems for advanced infections like preventable/treatable sepsis. This will likely intensify pressure on outpatient pharmacy networks, retail dispensing, and infusion centers, where PBMs already exert significant control.

-

2. PBM Tightening: Narrower PBM networks and stricter utilization management may further delay or restrict antimicrobial therapy, increasing the risk of resistance, treatment failure, and adverse outcomes.

-

3. Legislative Initiatives: While “The Bill” initially included provisions to curb PBM spread pricing, these were excluded from final law, however, ongoing Senate discussions continue to target spread pricing and financial transparency between PBMs and manufacturers. Reference Frieden2

-

4. Global Tariffs: Broader tariff escalation, particularly between the US, India, and Australia, is likely to lead to higher drug acquisition costs and may offset fair PBM reimbursement. Reference Murphy78–Reference Murphy80

-

5. Vaccines: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)-recommended vaccines have historically been covered under the ACA. With a curtailing of ACIP’s role under the current administration, vaccine coverage by PBMs and insurers could decline, with increases in infection-related morbidity and hospitalizations.

Summary and call to action

Providing standard of care treatment for infectious diseases (ID) like HIV and Hepatitis C has individual and societal benefits, like a reduction in downstream healthcare costs from preventable admissions, and progress toward ID elimination. PBMs were originally designed to manage prescription drug benefits, negotiate drug pricing with manufacturers and pharmacies, and promote cost-effectiveness, but in turn have restricted drug access and prevented patients from receiving the best studied treatments for their infections. PBMs’ pervasiveness and influence indicate that they are likely to endure, therefore equitable and timely antimicrobial access requires a multifaceted approach by ID physicians, pharmacists, and professional organizations. Moreover, proposed federal policy changes are poised to impact PBMs with additional uncertainties. Therefore, as ID clinicians, our critical role includes educating, empowering, and supporting patients in navigating insurance coverage, patient access programs, PAs, and other formulary restrictions. ID pharmacists and physicians are uniquely positioned to proactively identify access barriers and communicate challenges and solutions to treatment teams, and advocate to policy makers. Professional organizations can also advocate for transparent PBM practices that prioritize patient access and effectively serve our patients.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2025.10277

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the following for their support of this article and their advocacy to ensure equitable patient access to medications: Society for Healthcare Epidemiology; John Bellitti; William Schmidtknecht; Dr Christopher Cilderman; Dr Eamonn Vitt; Dr Lisa Schwartz.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support for this manuscript.

Competing interests

KR has no competing interests to disclose. AG has no competing interests to disclose. AA has no competing interests to disclose. DS has no competing interests to disclose. HJ is on the speaker’s bureau for Gilead Sciences, Inc. AJF has no competing interests to disclose. PN has no competing interests to disclose.