1 Introduction

In factor analysis, a potentially large set of dependent random variables is modeled as a linear combination of a smaller set of underlying latent (unobserved) factors. Factor analysis is ubiquitously applied in fields, such as econometrics (Aigner et al., Reference Aigner, Hsiao, Kapteyn and Wansbeek1984; Aßmann et al., Reference Aßmann, Boysen-Hogrefe and Pape2016; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Fan and Lv2008), psychology (Caprara et al., Reference Caprara, Barbaranelli, Borgogni and Perugini1993; Ford et al., Reference Ford, MacCallum and Tait1986; Goretzko et al., Reference Goretzko, Siemund and Sterner2023; Horn, Reference Horn1965; Reise et al., Reference Reise, Waller and Comrey2000), epidemiology (de Oliveira Santos et al., Reference de Oliveira Santos, Gorgulho, de Castro, Fisberg, Marchioni and Baltar2019; Martínez et al., Reference Martínez, Marshall and Sechrest1998), and education (Beavers et al., Reference Beavers, Lounsbury, Richards, Huck, Skolits and Esquivel2013; Schreiber et al., Reference Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow and King2006). It also has applications in causality (Pearl, Reference Pearl2000; Spirtes et al., Reference Spirtes, Glymour and Scheines2000) as a building block for models with latent variables (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Drton, Sturma and Weihs2022; Bollen, Reference Bollen1989).

Let

![]() $X=(X_v)_{v \in V}$

be an observed random vector, and let

$X=(X_v)_{v \in V}$

be an observed random vector, and let

![]() $Y=(Y_h)_{h \in \mathcal {H}}$

be a latent random vector, indexed by finite sets V and

$Y=(Y_h)_{h \in \mathcal {H}}$

be a latent random vector, indexed by finite sets V and

![]() $\mathcal {H}$

, respectively. Factor analysis models postulate that each observed variable

$\mathcal {H}$

, respectively. Factor analysis models postulate that each observed variable

![]() $X_v$

is a linear function of the factors

$X_v$

is a linear function of the factors

![]() $Y_h$

and noise, that is,

$Y_h$

and noise, that is,

where

![]() $\Lambda = (\lambda _{vh}) \in \mathbb {R}^{|V| \times |\mathcal {H}|}$

is an unknown coefficient matrix known as the factor loading matrix. The elements of

$\Lambda = (\lambda _{vh}) \in \mathbb {R}^{|V| \times |\mathcal {H}|}$

is an unknown coefficient matrix known as the factor loading matrix. The elements of

![]() $\varepsilon = (\varepsilon _v)_{v \in V}$

are mutually independent noise variables with mean zero and finite, positive variance. We consider orthogonal factor analysis, which means that we assume that the latent factors

$\varepsilon = (\varepsilon _v)_{v \in V}$

are mutually independent noise variables with mean zero and finite, positive variance. We consider orthogonal factor analysis, which means that we assume that the latent factors

![]() $(Y_h)_{h \in \mathcal {H}}$

are mutually independent. The model further assumes that

$(Y_h)_{h \in \mathcal {H}}$

are mutually independent. The model further assumes that

![]() $\varepsilon $

is independent of Y. Without loss of generality, we fix the scale of the factors such that

$\varepsilon $

is independent of Y. Without loss of generality, we fix the scale of the factors such that

![]() $\text {Var}[Y_h]=1$

for each factor. The main object of study, the covariance matrix of the observed random vector X, is then given by

$\text {Var}[Y_h]=1$

for each factor. The main object of study, the covariance matrix of the observed random vector X, is then given by

where

![]() $\Omega $

is a diagonal matrix with entries

$\Omega $

is a diagonal matrix with entries

![]() $\omega _{vv}= \text {Var}[\varepsilon _v]$

.

$\omega _{vv}= \text {Var}[\varepsilon _v]$

.

Our focus is on confirmatory factor analysis (Bollen, Reference Bollen1989, Chapter 7), which pertains to a prespecified model that encodes a scientific hypothesis or was learned previously in an exploratory step. Most interest is typically in models in which the factor loading matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

is sparse. In this article, we assume that the sparsity structure of the factor loading matrix and the number of latent factors

$\Lambda $

is sparse. In this article, we assume that the sparsity structure of the factor loading matrix and the number of latent factors

![]() $|\mathcal {H}|$

are fixed and known. Estimation of the factor loadings in confirmatory analyses has been subject to much controversy, due to the difficulties in determining model identifiability (Long, Reference Long1983). A factor analysis model is identifiable if the loading matrix

$|\mathcal {H}|$

are fixed and known. Estimation of the factor loadings in confirmatory analyses has been subject to much controversy, due to the difficulties in determining model identifiability (Long, Reference Long1983). A factor analysis model is identifiable if the loading matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

can be recovered from the covariance matrix

$\Lambda $

can be recovered from the covariance matrix

![]() $\Sigma $

in (1). If

$\Sigma $

in (1). If

![]() $\Lambda $

is not identifiable, then its estimates are to some degree arbitrary and standard inferential methods invalid (Cox, Reference Cox2024; Ximénez, Reference Ximénez2006).

$\Lambda $

is not identifiable, then its estimates are to some degree arbitrary and standard inferential methods invalid (Cox, Reference Cox2024; Ximénez, Reference Ximénez2006).

In full factor analysis, where no restrictions on the factor loading matrix are imposed (Drton et al., Reference Drton, Sturmfels and Sullivant2007), the matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

is never identifiable, due to rotational invariance. Indeed, for any orthogonal matrix

$\Lambda $

is never identifiable, due to rotational invariance. Indeed, for any orthogonal matrix

![]() $Q \in \mathbb {R}^{|\mathcal {H}| \times |\mathcal {H}|}$

, the product

$Q \in \mathbb {R}^{|\mathcal {H}| \times |\mathcal {H}|}$

, the product

![]() $\widetilde {\Lambda } = \Lambda Q$

satisfies

$\widetilde {\Lambda } = \Lambda Q$

satisfies

and, thus,

![]() $(\widetilde {\Lambda },\Omega )$

determines the same covariance matrix as

$(\widetilde {\Lambda },\Omega )$

determines the same covariance matrix as

![]() $(\Lambda ,\Omega )$

. For this reason, prior work on full factor analysis focuses on identifiability of

$(\Lambda ,\Omega )$

. For this reason, prior work on full factor analysis focuses on identifiability of

![]() $\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

or, equivalently, of

$\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

or, equivalently, of

![]() $\Omega $

. Bekker and ten Berge (Reference Bekker and ten Berge1997) characterize generic identifiability, which refers to whether

$\Omega $

. Bekker and ten Berge (Reference Bekker and ten Berge1997) characterize generic identifiability, which refers to whether

![]() $\Omega $

can be uniquely recovered for almost all parameter choices, except for a few corner cases at the so-called Ledermann bound. However, for models with sparsity restrictions on

$\Omega $

can be uniquely recovered for almost all parameter choices, except for a few corner cases at the so-called Ledermann bound. However, for models with sparsity restrictions on

![]() $\Lambda $

, the situation may improve, allowing for the identifiability of the loading matrix

$\Lambda $

, the situation may improve, allowing for the identifiability of the loading matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

itself up to sign changes of the columns. Identifiability up to column sign is the best we may hope for. If we multiply

$\Lambda $

itself up to sign changes of the columns. Identifiability up to column sign is the best we may hope for. If we multiply

![]() $\Lambda $

with a diagonal matrix

$\Lambda $

with a diagonal matrix

![]() $\Psi $

with entries in

$\Psi $

with entries in

![]() $\{\pm 1\}$

, then the support of

$\{\pm 1\}$

, then the support of

![]() $\Lambda \Psi $

is the same as the support of

$\Lambda \Psi $

is the same as the support of

![]() $\Lambda $

and it still holds that

$\Lambda $

and it still holds that

![]() $\Lambda \Psi \Psi ^{\top } \Lambda ^{\top } = \Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

.

$\Lambda \Psi \Psi ^{\top } \Lambda ^{\top } = \Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

.

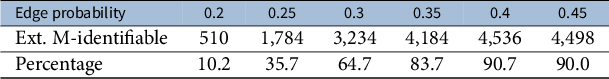

Example 1.1. In a re-analysis of a well-known five-dimensional example of Harman (Reference Harman1976, p.14), Trendafilov et al. (Reference Trendafilov, Fontanella and Adachi2017, Table 1, Column 3) apply

![]() $\ell _1$

-penalization techniques and infer the following sparsity pattern in the factor loading matrix:

$\ell _1$

-penalization techniques and infer the following sparsity pattern in the factor loading matrix:

$$\begin{align*}\Lambda^{\top} = \begin{pmatrix} \lambda_{11} & 0 & \lambda_{31} &\lambda_{41} &\lambda_{51}\\ 0 & \lambda_{22} & 0 & \lambda_{42} & \lambda_{52} \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\Lambda^{\top} = \begin{pmatrix} \lambda_{11} & 0 & \lambda_{31} &\lambda_{41} &\lambda_{51}\\ 0 & \lambda_{22} & 0 & \lambda_{42} & \lambda_{52} \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

This implies that the observed covariance matrix is given by

$$\begin{align*}\Sigma = (\sigma_{uv}) = \begin{pmatrix} \omega_{11}+\lambda_{11}^{2}&0 &\lambda_{11}\lambda_{31}&\lambda_{11}\lambda_{41}&\lambda_{11}\lambda_{51}\\ 0 &\omega_{22}+\lambda_{22}^{2}& 0 &\lambda_{22}\lambda_{42}&\lambda_{22}\lambda_{52}\\ \lambda_{11}\lambda_{31}&0&\omega_{33}+\lambda_{31}^{2}&\lambda_{31}\lambda_{41}&\lambda_{31}\lambda_{51}\\ \lambda_{11}\lambda_{41}&\lambda_{22}\lambda_{42}&\lambda_{31}\lambda_{41}&\omega_{44}+\lambda_{41}^{2}+\lambda_{52}^{2}&\lambda_{41}\lambda_{51}+\lambda_{42}\lambda_{52}\\ \lambda_{11}\lambda_{51}&\lambda_{22}\lambda_{52}&\lambda_{31}\lambda_{51}&\lambda_{41}\lambda_{51}+\lambda_{42}\lambda_{52}&\omega_{55}+\lambda_{51}^{2}+\lambda_{52}^{2} \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\Sigma = (\sigma_{uv}) = \begin{pmatrix} \omega_{11}+\lambda_{11}^{2}&0 &\lambda_{11}\lambda_{31}&\lambda_{11}\lambda_{41}&\lambda_{11}\lambda_{51}\\ 0 &\omega_{22}+\lambda_{22}^{2}& 0 &\lambda_{22}\lambda_{42}&\lambda_{22}\lambda_{52}\\ \lambda_{11}\lambda_{31}&0&\omega_{33}+\lambda_{31}^{2}&\lambda_{31}\lambda_{41}&\lambda_{31}\lambda_{51}\\ \lambda_{11}\lambda_{41}&\lambda_{22}\lambda_{42}&\lambda_{31}\lambda_{41}&\omega_{44}+\lambda_{41}^{2}+\lambda_{52}^{2}&\lambda_{41}\lambda_{51}+\lambda_{42}\lambda_{52}\\ \lambda_{11}\lambda_{51}&\lambda_{22}\lambda_{52}&\lambda_{31}\lambda_{51}&\lambda_{41}\lambda_{51}+\lambda_{42}\lambda_{52}&\omega_{55}+\lambda_{51}^{2}+\lambda_{52}^{2} \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

For almost every choice of

![]() $\Lambda $

, we have

$\Lambda $

, we have

![]() $\sigma _{34} = \lambda _{31}\lambda _{41} \neq 0$

, and the formula

$\sigma _{34} = \lambda _{31}\lambda _{41} \neq 0$

, and the formula

$$\begin{align*}\sqrt{\frac{\sigma_{13} \sigma_{14} }{\sigma_{34}}} = \sqrt{\frac{\lambda_{11}\lambda_{31} \, \lambda_{11}\lambda_{41}}{\lambda_{31}\lambda_{41}}} = \sqrt{\lambda_{11}^2} =|\lambda_{11} | \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\sqrt{\frac{\sigma_{13} \sigma_{14} }{\sigma_{34}}} = \sqrt{\frac{\lambda_{11}\lambda_{31} \, \lambda_{11}\lambda_{41}}{\lambda_{31}\lambda_{41}}} = \sqrt{\lambda_{11}^2} =|\lambda_{11} | \end{align*}$$

shows that we can recover the parameter

![]() $\lambda _{11}$

up to sign. Given

$\lambda _{11}$

up to sign. Given

![]() $|\lambda _{11}|$

, the remaining nonzero parameters of the first column of

$|\lambda _{11}|$

, the remaining nonzero parameters of the first column of

![]() $\Lambda $

are easily found, up to

$\Lambda $

are easily found, up to

![]() $\text {sign}(\lambda _{11})$

. For example,

$\text {sign}(\lambda _{11})$

. For example,

which is again well-defined for almost all parameter choices. Given

![]() $\Lambda _{\star ,1}$

up to sign, it is then possible to identify the second column

$\Lambda _{\star ,1}$

up to sign, it is then possible to identify the second column

![]() $\Lambda _{\star ,2}$

up to

$\Lambda _{\star ,2}$

up to

![]() $\text {sign}(\lambda _{22})$

using similar formulas.

$\text {sign}(\lambda _{22})$

using similar formulas.

Remark 1.2. If the latent factors are allowed to have arbitrary positive variance instead of fixing

![]() $\text {Var}[Y_h]=1$

, then we can only hope for identifiability up to column sign and column scaling of

$\text {Var}[Y_h]=1$

, then we can only hope for identifiability up to column sign and column scaling of

![]() $\Lambda $

. In this case, the absolute values of the recovered factor loadings within each column can be interpreted as the relative strength of effects.

$\Lambda $

. In this case, the absolute values of the recovered factor loadings within each column can be interpreted as the relative strength of effects.

The fact that sparsity improves identifiability was noted early in the literature, and there exist many methods in exploratory factor analysis that select a model that is as sparse as possible. Kaiser (Reference Kaiser1958) and Carroll (Reference Carroll1953) proposed methods that are still used in modern statistical software (Pedregosa et al., Reference Pedregosa, Varoquaux, Gramfort, Michel, Thirion, Grisel, Blondel, Prettenhofer, Weiss, Dubourg, Vanderplas, Passos, Cournapeau, Brucher, Perrot and Duchesnay2011), optimizing over all rotations such that many factor loadings are close to zero and the remaining loadings have a large absolute value. Developing methods for recovering a sparse factor loading matrix remains a very active field of research. Examples include regularization techniques (Goretzko, Reference Goretzko2023; Hirose & Konishi, Reference Hirose and Konishi2012; Lan et al., Reference Lan, Waters, Studer and Baraniuk2014; Lee & Seregina, Reference Lee and Seregina2023; Ning & Georgiou, Reference Ning and Georgiou2011; Scharf & Nestler, Reference Scharf and Nestler2019; Trendafilov et al., Reference Trendafilov, Fontanella and Adachi2017), rotation methods (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wallin, Chen and Moustaki2023), correlation thresholding (Kim & Zhou, Reference Kim and Zhou2023), and Bayesian approaches (Conti et al., Reference Conti, Frühwirth-Schnatter, Heckman and Piatek2014; Frühwirth-Schnatter et al., Reference Frühwirth-Schnatter, Hosszejni and Lopes2025; Ročková & George, Reference Ročková and George2016; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Gao, Mukherjee and Engelhardt2016).

In this article, we study identifiability of the factor loading matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

from the population covariance matrix

$\Lambda $

from the population covariance matrix

![]() $\Sigma = \Lambda \Lambda ^{\top } + \Omega $

, where the sparsity structure of

$\Sigma = \Lambda \Lambda ^{\top } + \Omega $

, where the sparsity structure of

![]() $\Lambda $

is fixed and known. Reflecting the problem’s inherent difficulty, the most prominent sufficient condition for identifiability in confirmatory factor analysis is still the criterion of Anderson and Rubin (Reference Anderson and Rubin1956), which certifies identifiability of

$\Lambda $

is fixed and known. Reflecting the problem’s inherent difficulty, the most prominent sufficient condition for identifiability in confirmatory factor analysis is still the criterion of Anderson and Rubin (Reference Anderson and Rubin1956), which certifies identifiability of

![]() $\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

. Subsequently, criteria were developed for identifying

$\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

. Subsequently, criteria were developed for identifying

![]() $\Lambda $

from

$\Lambda $

from

![]() $\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

up to column sign (see Williams, Reference Williams2020 or Bai & Li, Reference Bai and Li2012, Section 4). Examples include the three-indicator rule of Bollen (Reference Bollen1989) and the side-by-side rule of Reilly and O’Brien (Reference Reilly and O’Brien1996). However, gaps remain in the existing results. As noted by Hosszejni and Frühwirth-Schnatter (Reference Hosszejni and Frühwirth-Schnatter2026), the model given by the sparse matrix

$\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

up to column sign (see Williams, Reference Williams2020 or Bai & Li, Reference Bai and Li2012, Section 4). Examples include the three-indicator rule of Bollen (Reference Bollen1989) and the side-by-side rule of Reilly and O’Brien (Reference Reilly and O’Brien1996). However, gaps remain in the existing results. As noted by Hosszejni and Frühwirth-Schnatter (Reference Hosszejni and Frühwirth-Schnatter2026), the model given by the sparse matrix

$$ \begin{align} \Lambda^{\top} = \begin{pmatrix} \lambda_{11} & \lambda_{21} & 0 & \lambda_{41} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_{22} & \lambda_{32} & 0 & \lambda_{52} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \lambda_{33} & \lambda_{43} & 0 & \lambda_{63} \\ \end{pmatrix} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \Lambda^{\top} = \begin{pmatrix} \lambda_{11} & \lambda_{21} & 0 & \lambda_{41} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_{22} & \lambda_{32} & 0 & \lambda_{52} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \lambda_{33} & \lambda_{43} & 0 & \lambda_{63} \\ \end{pmatrix} \end{align} $$

is identifiable up to column sign in an almost sure sense, but the criterion of Anderson and Rubin (Reference Anderson and Rubin1956) and the subsequent developments are not able to certify it.

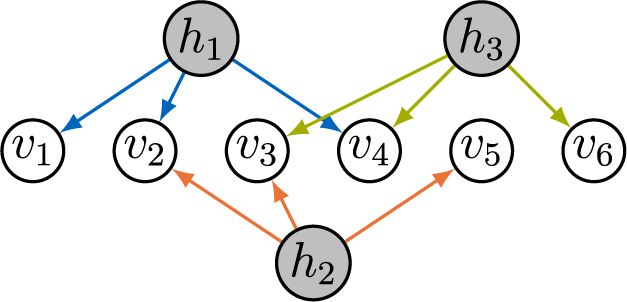

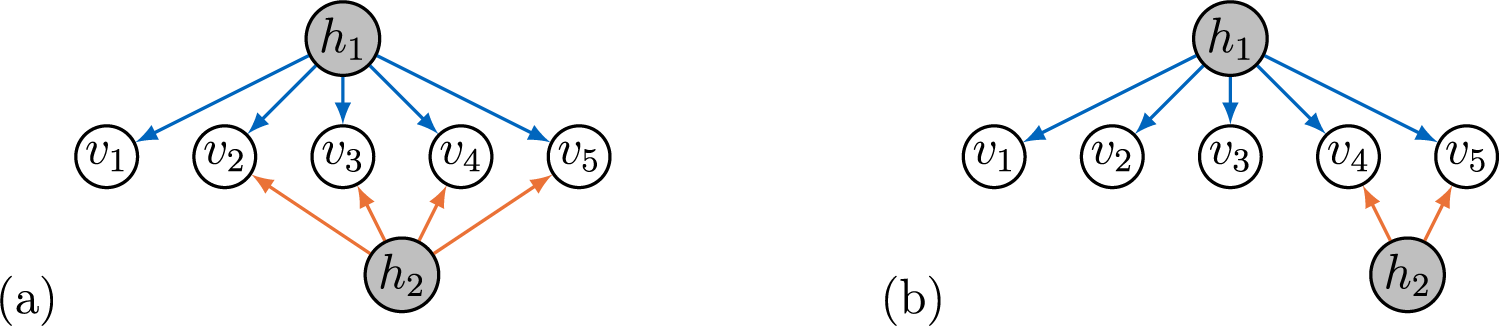

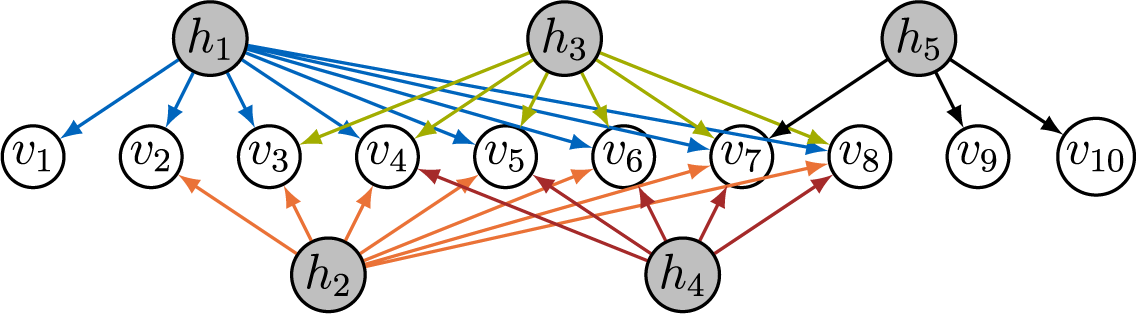

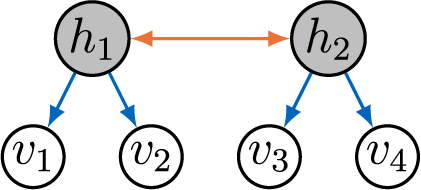

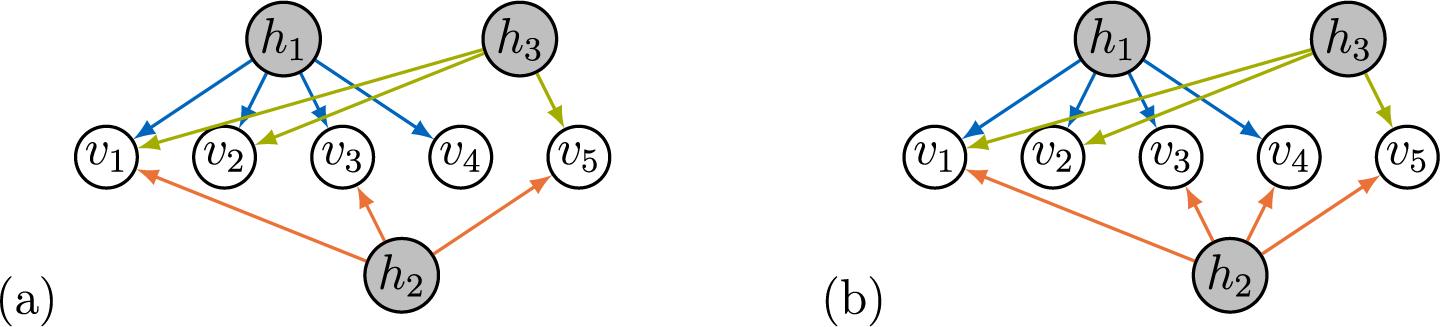

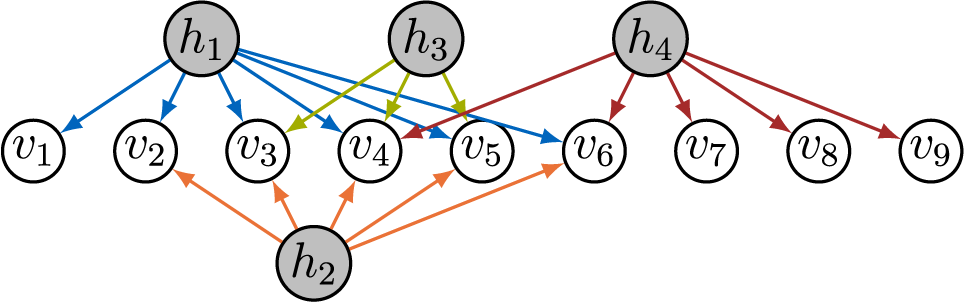

In contrast to prior work, we take a graphical perspective to specify the sparsity structure in

![]() $\Lambda $

(Lauritzen, Reference Lauritzen1996; Maathuis et al., Reference Maathuis, Drton, Lauritzen and Wainwright2019). For example, the graph in Figure 1 encodes the sparsity structure in the factor loading matrix given in Equation (2). When an edge

$\Lambda $

(Lauritzen, Reference Lauritzen1996; Maathuis et al., Reference Maathuis, Drton, Lauritzen and Wainwright2019). For example, the graph in Figure 1 encodes the sparsity structure in the factor loading matrix given in Equation (2). When an edge

![]() $h \rightarrow v$

is missing in the graph, the corresponding entry

$h \rightarrow v$

is missing in the graph, the corresponding entry

![]() $\lambda _{vh}$

is required to be zero. Building on Anderson and Rubin (Reference Anderson and Rubin1956) and Bekker and ten Berge (Reference Bekker and ten Berge1997), our new matching criterion (and an extension thereof) is a purely graphical criterion that exploits sparsity by operating locally on the structure of the graph.

$\lambda _{vh}$

is required to be zero. Building on Anderson and Rubin (Reference Anderson and Rubin1956) and Bekker and ten Berge (Reference Bekker and ten Berge1997), our new matching criterion (and an extension thereof) is a purely graphical criterion that exploits sparsity by operating locally on the structure of the graph.

Figure 1 Directed graph encoding the sparsity structure in a factor analysis model.

Deciding identifiability corresponds to solving the equation system from (1). Since the equations are polynomial in the factor loadings

![]() $\lambda _{vh}$

, identifiability is, in principle, always decidable via Gröbner basis methods from computational algebraic geometry (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Drton, Sturma and Weihs2022; Garcia-Puente et al., Reference Garcia-Puente, Spielvogel and Sullivant2010). But the scope of such methods is limited to small graphs as their complexity can grow double exponentially with the size of the graph (Mayr, Reference Mayr1997). In contrast, our new graphical criteria can be checked in polynomial time, provided we restrict a search step to subsets of bounded size.

$\lambda _{vh}$

, identifiability is, in principle, always decidable via Gröbner basis methods from computational algebraic geometry (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Drton, Sturma and Weihs2022; Garcia-Puente et al., Reference Garcia-Puente, Spielvogel and Sullivant2010). But the scope of such methods is limited to small graphs as their complexity can grow double exponentially with the size of the graph (Mayr, Reference Mayr1997). In contrast, our new graphical criteria can be checked in polynomial time, provided we restrict a search step to subsets of bounded size.

The organization of the article is as follows. Section 2 formally introduces the concept of generic sign-identifiability, and we revisit the criteria of Anderson and Rubin (Reference Anderson and Rubin1956) and Bekker and ten Berge (Reference Bekker and ten Berge1997) in Section 3. Section 4 presents our main results, the matching criterion and its extension. In Section 5, we show that both criteria are decidable in polynomial time. In Section 6, we conduct experiments that demonstrate the performance of our criteria and exemplify how our identifiability criteria are also useful in exploratory factor analysis. The Supplementary Material contains additional results for full factor models (Appendix A of the Supplementary Material), efficient algorithms (Appendix B of the Supplementary Material), all technical proofs (Appendix C of the Supplementary Material), and an explanation of how to decide identifiability using algebraic tools (Appendix D of the Supplementary Material).

2 Graphical representation and identifiability

Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a directed graph, where V and

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a directed graph, where V and

![]() $\mathcal {H}$

are finite disjoint sets of observed and latent nodes. We assume that the graph

$\mathcal {H}$

are finite disjoint sets of observed and latent nodes. We assume that the graph

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

is bipartite, that is, it only contains edges from latent to observed variables such that

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

is bipartite, that is, it only contains edges from latent to observed variables such that

![]() $D \subseteq \mathcal {H} \times V$

. We refer to such graphs as factor analysis graphs. If G contains an edge

$D \subseteq \mathcal {H} \times V$

. We refer to such graphs as factor analysis graphs. If G contains an edge

![]() $(h,v) \in D$

, then we also denote this by

$(h,v) \in D$

, then we also denote this by

![]() $h \rightarrow v \in D$

. The set

$h \rightarrow v \in D$

. The set

![]() $\text {ch}(h)=\{v \in V: h \rightarrow v \in D\}$

contains the children of a latent node

$\text {ch}(h)=\{v \in V: h \rightarrow v \in D\}$

contains the children of a latent node

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$

, and the set

$h \in \mathcal {H}$

, and the set

![]() $\text {pa}(v)=\{h \in \mathcal {H}: h \rightarrow v \in D\}$

contains the parents of an observed node

$\text {pa}(v)=\{h \in \mathcal {H}: h \rightarrow v \in D\}$

contains the parents of an observed node

![]() $v \in V$

.

$v \in V$

.

Each bipartite graph defines a factor analysis model, which for our purposes may be identified with a set of covariance matrices.

Definition 2.1. Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph with

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph with

![]() $|V|=p$

and

$|V|=p$

and

![]() $|\mathcal {H}|=m$

, and let

$|\mathcal {H}|=m$

, and let

![]() $\mathbb {R}^D$

be the space of real

$\mathbb {R}^D$

be the space of real

![]() $p\times m$

matrices

$p\times m$

matrices

![]() $\Lambda = (\lambda _{vh})$

with support D, that is,

$\Lambda = (\lambda _{vh})$

with support D, that is,

![]() $\lambda _{vh} = 0$

if

$\lambda _{vh} = 0$

if

![]() $h \rightarrow v \not \in D$

. The factor analysis model determined by G is the image

$h \rightarrow v \not \in D$

. The factor analysis model determined by G is the image

![]() $F(G) = \text {Im}(\tau _G)$

of the parameterization

$F(G) = \text {Im}(\tau _G)$

of the parameterization

$$ \begin{align*} \begin{split} \tau_G : \mathbb{R}^p_{>0} \times \mathbb{R}^D &\longrightarrow \operatorname{\mathrm{\mathit{PD}}}(p) \\ (\Omega, \Lambda) &\longmapsto \Omega + \Lambda \Lambda^{\top}, \end{split} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \begin{split} \tau_G : \mathbb{R}^p_{>0} \times \mathbb{R}^D &\longrightarrow \operatorname{\mathrm{\mathit{PD}}}(p) \\ (\Omega, \Lambda) &\longmapsto \Omega + \Lambda \Lambda^{\top}, \end{split} \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {\mathit {PD}}}(p)$

is the cone of positive-definite

$\operatorname {\mathrm {\mathit {PD}}}(p)$

is the cone of positive-definite

![]() $p \times p$

matrices, and

$p \times p$

matrices, and

![]() $\mathbb {R}^p_{>0} \subset \operatorname {\mathrm {\mathit {PD}}}(p)$

is the subset of diagonal positive-definite matrices.

$\mathbb {R}^p_{>0} \subset \operatorname {\mathrm {\mathit {PD}}}(p)$

is the subset of diagonal positive-definite matrices.

Identifiability holds if we can recover

![]() $\Omega $

and

$\Omega $

and

![]() $\Lambda $

from a given matrix

$\Lambda $

from a given matrix

![]() $\Sigma \in F(G)$

up to column signs of the matrix

$\Sigma \in F(G)$

up to column signs of the matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

. To make this precise, we write

$\Lambda $

. To make this precise, we write

for the fiber of a pair

![]() $(\Omega , \Lambda )$

in the domain

$(\Omega , \Lambda )$

in the domain

![]() $\Theta _{G}=\mathbb {R}^{|V|}_{>0} \times \mathbb {R}^D$

of the parameterization

$\Theta _{G}=\mathbb {R}^{|V|}_{>0} \times \mathbb {R}^D$

of the parameterization

![]() $\tau _G$

.

$\tau _G$

.

Definition 2.2. A factor analysis graph

![]() $ G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

is said to be generically sign-identifiable if

$ G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

is said to be generically sign-identifiable if

for almost all

![]() $(\Omega , \Lambda ) \in \Theta _G$

. Moreover, we say that a node

$(\Omega , \Lambda ) \in \Theta _G$

. Moreover, we say that a node

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$

in a factor analysis graph

$h \in \mathcal {H}$

in a factor analysis graph

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

is generically sign-identifiable if it holds for almost all

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

is generically sign-identifiable if it holds for almost all

![]() $(\Omega , \Lambda ) \in \Theta _G$

that each parameter pair

$(\Omega , \Lambda ) \in \Theta _G$

that each parameter pair

![]() $(\widetilde {\Omega }, \widetilde {\Lambda })\in \mathcal {F}_G(\Omega , \Lambda )$

satisfies

$(\widetilde {\Omega }, \widetilde {\Lambda })\in \mathcal {F}_G(\Omega , \Lambda )$

satisfies

![]() $\widetilde {\Lambda }_{\text {ch}(h),h}=\Lambda _{\text {ch}(h),h}$

.

$\widetilde {\Lambda }_{\text {ch}(h),h}=\Lambda _{\text {ch}(h),h}$

.

In Definition 2.2, “almost all” is meant with respect to the induced Lebesgue measure on

![]() $\Theta _G$

, considered as an open subset of

$\Theta _G$

, considered as an open subset of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^{|V|+|D|}$

. If a graph is generically sign-identifiable, then for a factor loading matrix

$\mathbb {R}^{|V|+|D|}$

. If a graph is generically sign-identifiable, then for a factor loading matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

and a diagonal covariance matrix

$\Lambda $

and a diagonal covariance matrix

![]() $\Omega $

drawn randomly from an absolutely continuous distribution, the resulting covariance matrix of the observable vector X will almost surely allow recovery of

$\Omega $

drawn randomly from an absolutely continuous distribution, the resulting covariance matrix of the observable vector X will almost surely allow recovery of

![]() $\Lambda $

up to column sign.

$\Lambda $

up to column sign.

Example 2.3. Consider the identification formula for

![]() $|\lambda _{11}|$

in Example 1.1 given by

$|\lambda _{11}|$

in Example 1.1 given by

$$\begin{align*}\sqrt{\frac{\sigma_{13} \sigma_{14} }{\sigma_{34}}} = \sqrt{\frac{\lambda_{11}\lambda_{31} \, \lambda_{11}\lambda_{41}}{\lambda_{31}\lambda_{41}}}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\sqrt{\frac{\sigma_{13} \sigma_{14} }{\sigma_{34}}} = \sqrt{\frac{\lambda_{11}\lambda_{31} \, \lambda_{11}\lambda_{41}}{\lambda_{31}\lambda_{41}}}. \end{align*}$$

This formula does not hold if at least one of the parameters

![]() $\lambda _{31}$

and

$\lambda _{31}$

and

![]() $\lambda _{41}$

is equal to zero. Hence, for such exceptional parameter pairs

$\lambda _{41}$

is equal to zero. Hence, for such exceptional parameter pairs

![]() $(\Omega ,\Lambda ),$

we cannot establish the correct form of the fiber and identification fails. However, since the set of exceptional pairs forms a Lebesgue measure zero subset of the parameter space, we obtain generic sign-identifiability.

$(\Omega ,\Lambda ),$

we cannot establish the correct form of the fiber and identification fails. However, since the set of exceptional pairs forms a Lebesgue measure zero subset of the parameter space, we obtain generic sign-identifiability.

Note that any node h with

![]() $\text {ch}(h)=\emptyset $

is trivially generically sign-identifiable. For later reference, we formally record how generic sign-identifiability of the graph results from generic sign-identifiability of all nodes.

$\text {ch}(h)=\emptyset $

is trivially generically sign-identifiable. For later reference, we formally record how generic sign-identifiability of the graph results from generic sign-identifiability of all nodes.

Lemma 2.4. A factor analysis graph

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

is generically sign-identifiable if and only if all nodes

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

is generically sign-identifiable if and only if all nodes

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$

are generically sign-identifiable.

$h \in \mathcal {H}$

are generically sign-identifiable.

Remark 2.5. A model can only be generically sign-identifiable if its dimension matches the parameter count

![]() $|V|+|D|$

. Recently, Drton et al. (Reference Drton, Grosdos, Portakal and Sturma2025) proved upper and lower bounds for the dimension of sparse factor analysis models. The bounds reveal that such models may have dimension strictly smaller than

$|V|+|D|$

. Recently, Drton et al. (Reference Drton, Grosdos, Portakal and Sturma2025) proved upper and lower bounds for the dimension of sparse factor analysis models. The bounds reveal that such models may have dimension strictly smaller than

![]() $|V|+|D|$

and, thus, may be non-identifiable. The bounds also show that a necessary condition for a factor analysis graph to be generically sign-identifiable is that each latent node has at least three children.

$|V|+|D|$

and, thus, may be non-identifiable. The bounds also show that a necessary condition for a factor analysis graph to be generically sign-identifiable is that each latent node has at least three children.

3 Existing criteria

Due to rotational indeterminacy, previous work on identifiability of full factor analysis models focused on identifying the diagonal matrix

![]() $\Omega $

. If we require that the upper triangle of the matrix

$\Omega $

. If we require that the upper triangle of the matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

is zero, then existing criteria may also yield generic sign-identifiability.

$\Lambda $

is zero, then existing criteria may also yield generic sign-identifiability.

Definition 3.1. A factor analysis graph

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

satisfies the zero upper triangular assumption (ZUTA) if there exists an ordering

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

satisfies the zero upper triangular assumption (ZUTA) if there exists an ordering

![]() $\prec $

on the latent nodes

$\prec $

on the latent nodes

![]() $\mathcal {H}$

such that

$\mathcal {H}$

such that

![]() $\text {ch}(h)$

is not contained in

$\text {ch}(h)$

is not contained in

![]() $\bigcup _{\ell \succ h} \text {ch}(\ell )$

for all

$\bigcup _{\ell \succ h} \text {ch}(\ell )$

for all

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$

. In this case, we say that

$h \in \mathcal {H}$

. In this case, we say that

![]() $\prec $

is a ZUTA-ordering with respect to G.

$\prec $

is a ZUTA-ordering with respect to G.

ZUTA ensures that the rows and columns of the factor loading matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

can be permuted such that the upper triangle of the matrix is zero. Note that ZUTA eliminates rotational indeterminacy. That is, if it holds that

$\Lambda $

can be permuted such that the upper triangle of the matrix is zero. Note that ZUTA eliminates rotational indeterminacy. That is, if it holds that

![]() $\Sigma - \Omega = \widetilde {\Lambda } \widetilde {\Lambda }^{\top }$

for a matrix

$\Sigma - \Omega = \widetilde {\Lambda } \widetilde {\Lambda }^{\top }$

for a matrix

![]() $\widetilde {\Lambda }$

that is zero upper triangular, i.e.,

$\widetilde {\Lambda }$

that is zero upper triangular, i.e.,

![]() $\widetilde {\Lambda }_{ij}=0$

for

$\widetilde {\Lambda }_{ij}=0$

for

![]() $i < j$

, then it follows from the uniqueness of the Cholesky decomposition that

$i < j$

, then it follows from the uniqueness of the Cholesky decomposition that

![]() $\widetilde {\Lambda }$

is unique up to column sign, i.e.,

$\widetilde {\Lambda }$

is unique up to column sign, i.e.,

![]() $\widetilde {\Lambda } = \Lambda \Psi $

for a fixed matrix

$\widetilde {\Lambda } = \Lambda \Psi $

for a fixed matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

and a diagonal matrix

$\Lambda $

and a diagonal matrix

![]() $\Psi $

with entries in

$\Psi $

with entries in

![]() $\{\pm 1\}$

.

$\{\pm 1\}$

.

If a factor analysis graph satisfies the ZUTA condition, then there is an observed node

![]() $v_h \in \text {ch}(h)$

for each

$v_h \in \text {ch}(h)$

for each

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$

such that

$h \in \mathcal {H}$

such that

![]() $v_h \in \text {ch}(h)$

and

$v_h \in \text {ch}(h)$

and

![]() $v_h \not \in \bigcup _{\ell \succ h} \text {ch}(\ell )$

. In particular, it is a necessary condition for ZUTA that there is at least one observed node that only has one latent parent.

$v_h \not \in \bigcup _{\ell \succ h} \text {ch}(\ell )$

. In particular, it is a necessary condition for ZUTA that there is at least one observed node that only has one latent parent.

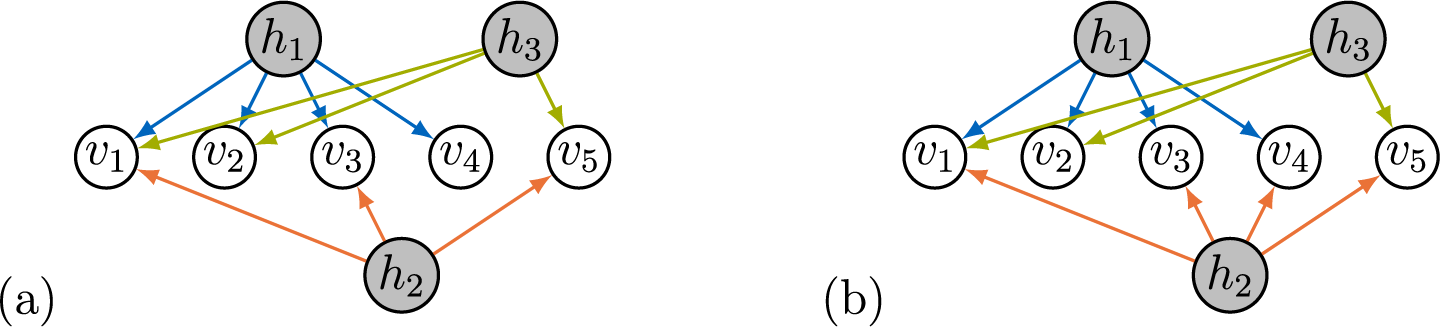

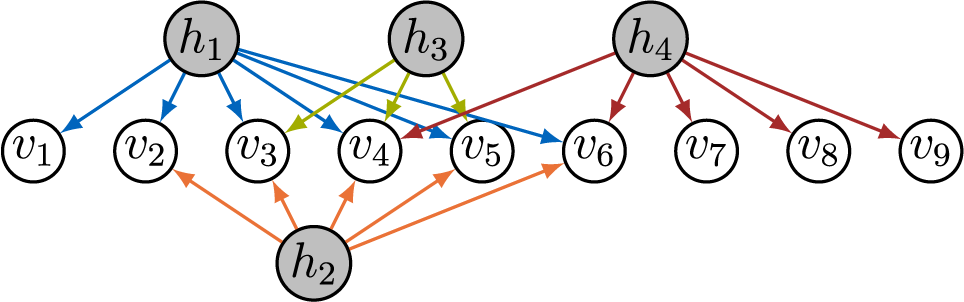

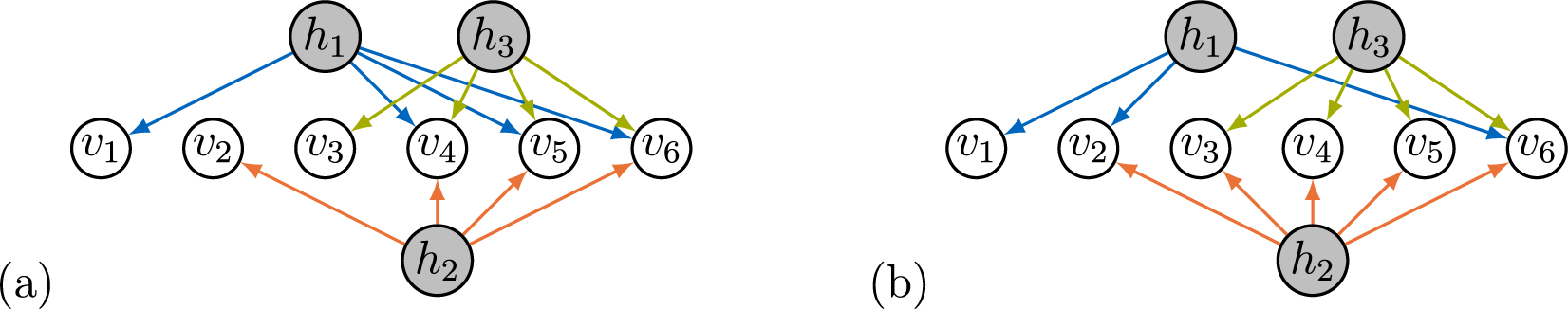

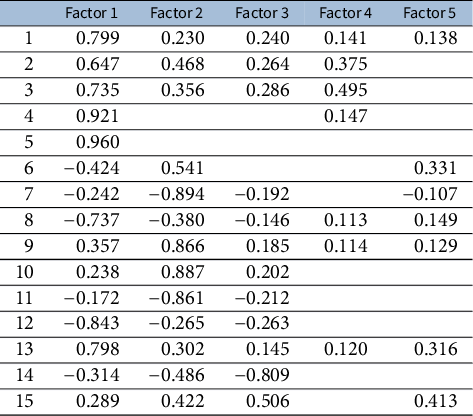

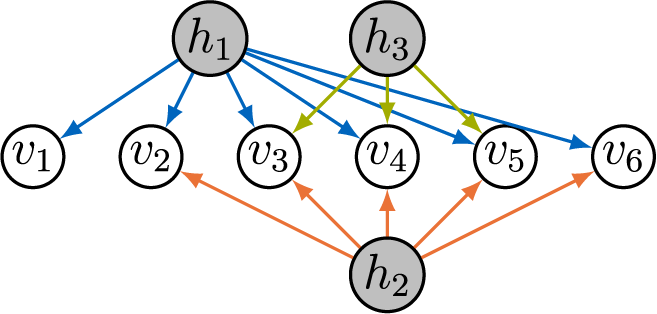

Example 3.2. The graph in Figure 2a satisfies ZUTA with the ordering

![]() $h_1 \prec h_2 \prec h_3$

, since

$h_1 \prec h_2 \prec h_3$

, since

![]() $v_4 \in \text {ch}(h_1)$

but

$v_4 \in \text {ch}(h_1)$

but

![]() $v_4 \not \in \text {ch}(h_2) \cup \text {ch}(h_3)$

, and

$v_4 \not \in \text {ch}(h_2) \cup \text {ch}(h_3)$

, and

![]() $v_3 \in \text {ch}(h_2)$

but

$v_3 \in \text {ch}(h_2)$

but

![]() $v_3 \not \in \text {ch}(h_3)$

. However, the graph in Figure 2b does not satisfy ZUTA as no observed node has only one parent.

$v_3 \not \in \text {ch}(h_3)$

. However, the graph in Figure 2b does not satisfy ZUTA as no observed node has only one parent.

Figure 2 Two factor analysis graphs. Graph (a) satisfies ZUTA while graph (b) does not.

Remark 3.3. ZUTA is equivalent to the generalized lower triangular assumption introduced in Frühwirth-Schnatter et al. (Reference Frühwirth-Schnatter, Hosszejni and Lopes2025), which operates directly on the matrix

![]() $\Lambda $

. ZUTA refers to the graph, which is useful to present our graphical criteria in Section 4.

$\Lambda $

. ZUTA refers to the graph, which is useful to present our graphical criteria in Section 4.

If we consider graphs that satisfy ZUTA, many criteria in the literature directly yield generic sign-identifiability. The most prominent condition for identifiability is still the criterion of Anderson and Rubin (Reference Anderson and Rubin1956). Since it is originally stated as a pointwise condition, it is also applicable to sparse graphs. To state the result one obtains, we treat the entries of

![]() $\Lambda $

as indeterminates and say that a submatrix is generically of rank k if it has rank k for almost all choices of

$\Lambda $

as indeterminates and say that a submatrix is generically of rank k if it has rank k for almost all choices of

![]() $\Lambda \in \mathbb {R}^D$

. Under the assumption that a graph satisfies ZUTA, Theorem 5.1 in Anderson and Rubin (Reference Anderson and Rubin1956) then translates to the following sufficient condition for generic sign-identifiability.

$\Lambda \in \mathbb {R}^D$

. Under the assumption that a graph satisfies ZUTA, Theorem 5.1 in Anderson and Rubin (Reference Anderson and Rubin1956) then translates to the following sufficient condition for generic sign-identifiability.

Theorem 3.4 (AR-identifiability)

Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph that satisfies ZUTA. Then, G is generically sign-identifiable if for any deleted row of

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph that satisfies ZUTA. Then, G is generically sign-identifiable if for any deleted row of

![]() $\Lambda = (\lambda _{vh}) \in \mathbb {R}^D$

, there remain two disjoint submatrices that are generically of rank

$\Lambda = (\lambda _{vh}) \in \mathbb {R}^D$

, there remain two disjoint submatrices that are generically of rank

![]() $|\mathcal {H}|$

.

$|\mathcal {H}|$

.

If generic sign-identifiability can be proven by applying Theorem 3.4 for a factor analysis graph, then we say that the graph is AR-identifiable.

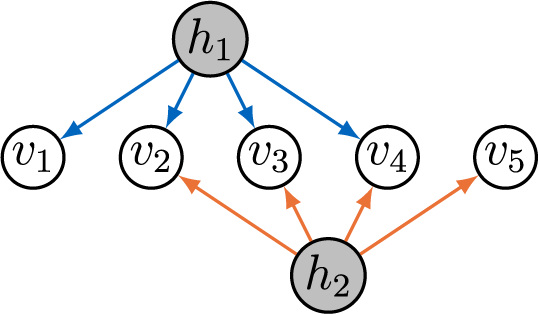

Example 3.5. The graph in Figure 3 gives rise to the transpose of

![]() $\Lambda \in \mathbb {R}^D$

given by

$\Lambda \in \mathbb {R}^D$

given by

$$\begin{align*}\Lambda^{\top} = \begin{pmatrix} \lambda_{v_1 h_1} & \lambda_{v_2 h_1} & \lambda_{v_3 h_1} & \lambda_{v_4 h_1} & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_{v_3 h_2} & \lambda_{v_3 h_2} & \lambda_{v_4 h_2} & \lambda_{v_5 h_2} \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\Lambda^{\top} = \begin{pmatrix} \lambda_{v_1 h_1} & \lambda_{v_2 h_1} & \lambda_{v_3 h_1} & \lambda_{v_4 h_1} & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_{v_3 h_2} & \lambda_{v_3 h_2} & \lambda_{v_4 h_2} & \lambda_{v_5 h_2} \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

Deleting any row of

![]() $\Lambda $

leaves four rows that can always be split into two

$\Lambda $

leaves four rows that can always be split into two

![]() $2 \times 2$

matrices that generically have rank 2. Hence, the graph is AR-identifiable.

$2 \times 2$

matrices that generically have rank 2. Hence, the graph is AR-identifiable.

Figure 3 AR-identifiable factor analysis graph.

AR-identifiability requires

![]() $|V| \geq 2 |\mathcal {H}|+1$

. For general full factor analysis models, Bekker and ten Berge (Reference Bekker and ten Berge1997) solve the problem of generic identifiability (up to orthogonal transformation) in all but certain edge cases. However, the generic nature of their condition implies sign-identifiability results only for dense ZUTA graphs, in which only a permuted upper triangle vanishes.

$|V| \geq 2 |\mathcal {H}|+1$

. For general full factor analysis models, Bekker and ten Berge (Reference Bekker and ten Berge1997) solve the problem of generic identifiability (up to orthogonal transformation) in all but certain edge cases. However, the generic nature of their condition implies sign-identifiability results only for dense ZUTA graphs, in which only a permuted upper triangle vanishes.

Definition 3.6. A full-ZUTA graph is a factor analysis graph

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

that satisfies ZUTA but contains all other possible edges. That is, there is an ordering

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

that satisfies ZUTA but contains all other possible edges. That is, there is an ordering

![]() $\prec $

on the latent nodes

$\prec $

on the latent nodes

![]() $\mathcal {H}=\{h_1, \ldots , h_m\}$

such that

$\mathcal {H}=\{h_1, \ldots , h_m\}$

such that

![]() $h_1 \prec \cdots \prec h_m$

, with the property that

$h_1 \prec \cdots \prec h_m$

, with the property that

![]() $\text {ch}(h_1)=V$

and

$\text {ch}(h_1)=V$

and

![]() $\text {ch}(h_{i+1})=\text {ch}(h_{i}) \setminus \{v_{i}\}$

for some child

$\text {ch}(h_{i+1})=\text {ch}(h_{i}) \setminus \{v_{i}\}$

for some child

![]() $v_{i} \in \text {ch}(h_{i})$

.

$v_{i} \in \text {ch}(h_{i})$

.

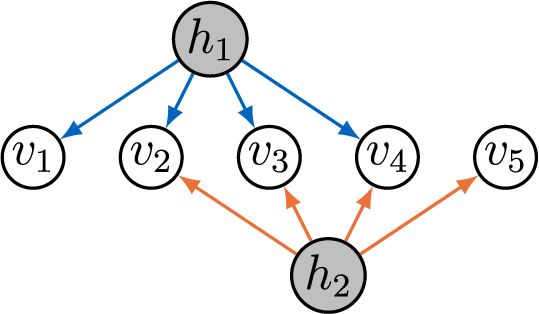

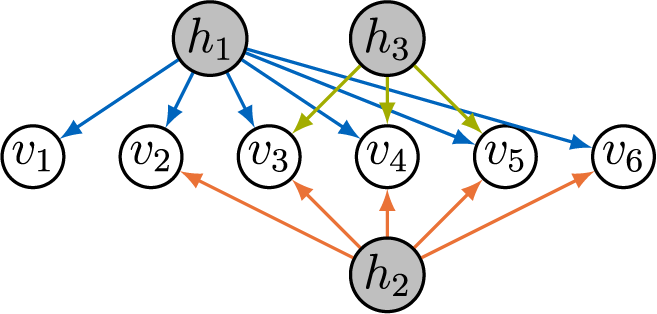

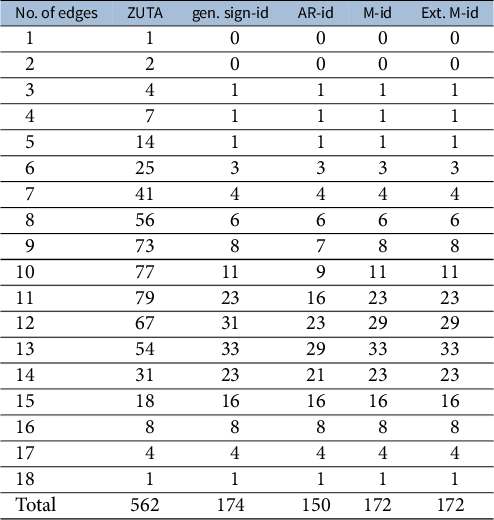

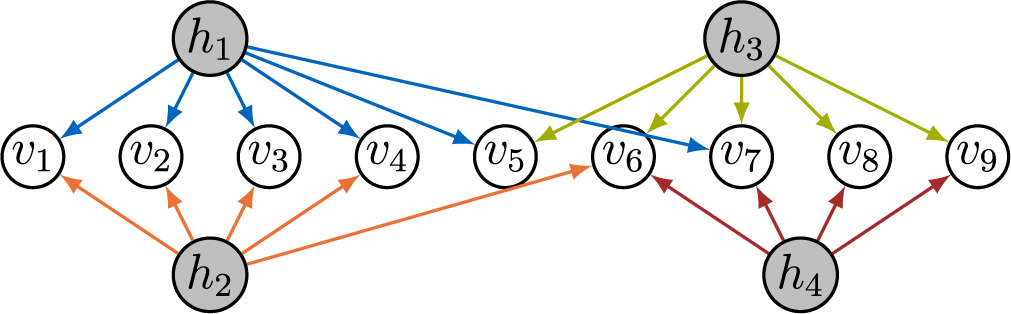

As an example, Figure 4a displays the full-ZUTA graph on three latent and six observed nodes. For full-ZUTA graphs, the criterion from Bekker and ten Berge (Reference Bekker and ten Berge1997) directly translates into the following sufficient condition for generic sign-identifiability.

Figure 4 Two full-ZUTA graphs.

Theorem 3.7 (BB-identifiability)

Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a full-ZUTA graph. Then, G is generically sign-identifiable if

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a full-ZUTA graph. Then, G is generically sign-identifiable if

![]() $|V| + |D| < \binom {|V|+1}{2}$

.

$|V| + |D| < \binom {|V|+1}{2}$

.

If a full-ZUTA graph is generic sign-identifiability by Theorem 3.7, then we term the graph BB-identifiable. Note that

![]() $|V| + |D| = |V|(|\mathcal {H}|+1) - \binom {|\mathcal {H}|}{2}$

in a full-ZUTA graph. If

$|V| + |D| = |V|(|\mathcal {H}|+1) - \binom {|\mathcal {H}|}{2}$

in a full-ZUTA graph. If

![]() $|V| + |D|> \binom {|V|+1}{2}$

, then the parameter count is larger than the dimension of the ambient space of symmetric matrices, and full-ZUTA graphs are not generically sign-identifiable (recall Remark 2.5). Hence, the only remaining open cases where identifiability of full-ZUTA graphs is unknown are models “at the Ledermann bound,” where

$|V| + |D|> \binom {|V|+1}{2}$

, then the parameter count is larger than the dimension of the ambient space of symmetric matrices, and full-ZUTA graphs are not generically sign-identifiable (recall Remark 2.5). Hence, the only remaining open cases where identifiability of full-ZUTA graphs is unknown are models “at the Ledermann bound,” where

![]() $|V| + |D| = \binom {|V|+1}{2}$

.

$|V| + |D| = \binom {|V|+1}{2}$

.

Example 3.8. Figure 4 shows two full-ZUTA graphs. Graph (b) is BB-identifiable because

![]() $ |V| + |D| = 24 \, < \, 28 = \binom {7+1}{2}. $

Graph (a), on the other hand, has

$ |V| + |D| = 24 \, < \, 28 = \binom {7+1}{2}. $

Graph (a), on the other hand, has

![]() $ |V| + |D| = \, 21 \, = \binom {6+1}{2}. $

As already noted by Wilson and Worcester (Reference Wilson and Worcester1939), the fiber for graph (a), with

$ |V| + |D| = \, 21 \, = \binom {6+1}{2}. $

As already noted by Wilson and Worcester (Reference Wilson and Worcester1939), the fiber for graph (a), with

![]() $|V|=6$

and

$|V|=6$

and

![]() $|\mathcal {H}|=3$

, generically contains two diagonal matrices and two corresponding factor loading matrices together with their symmetries given by the sign changes of the columns.

$|\mathcal {H}|=3$

, generically contains two diagonal matrices and two corresponding factor loading matrices together with their symmetries given by the sign changes of the columns.

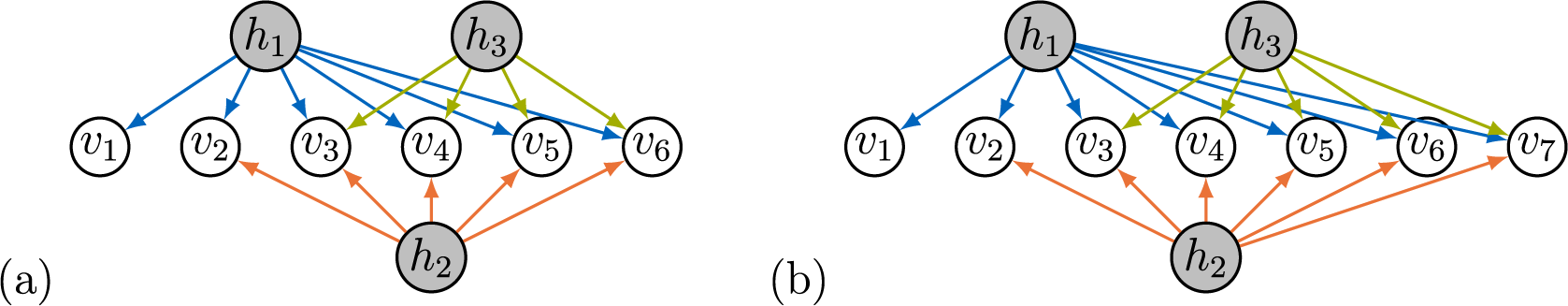

Remark 3.9. Generic sign-identifiability of full-ZUTA graphs does not imply identifiability of sparse subgraphs, since the models corresponding to subgraphs might be non-generic points in the model given by the full-ZUTA graph. For example, consider the full-ZUTA graph in Figure 5a that is generically sign-identifiable by Theorem 3.7. The graph in Figure 5b is a sparse subgraph. Since in this graph

![]() $|\text {ch}(h_2)| < 3$

, it follows that the model has not expected dimension and is hence not generically sign-identifiable (recall Remark 2.5).

$|\text {ch}(h_2)| < 3$

, it follows that the model has not expected dimension and is hence not generically sign-identifiable (recall Remark 2.5).

Figure 5 Full-ZUTA graph and a sparse subgraph.

The following example shows two graphs that are generically sign-identifiable but no known general criterion is able to certify it.

Example 3.10. The loading matrix for the graph in Figure 6 has transpose

$$\begin{align*}\Lambda^{\top} = \begin{pmatrix} \lambda_{v_1 h_1} & \lambda_{v_2 h_1} & \lambda_{v_3 h_1} & \lambda_{v_4 h_1} & \lambda_{v_5 h_1} & \lambda_{v_6 h_1} & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_{v_2 h_2} & \lambda_{v_3 h_2} & \lambda_{v_4 h_2} & \lambda_{v_5 h_2} & \lambda_{v_6 h_2} & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \lambda_{v_3 h_3} & \lambda_{v_4 h_3} & \lambda_{v_5 h_3} & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \lambda_{v_4 h_4} & 0 & \lambda_{v_6 h_4} & \lambda_{v_7 h_4} & \lambda_{v_8 h_4} & \lambda_{v_9 h_4} \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\Lambda^{\top} = \begin{pmatrix} \lambda_{v_1 h_1} & \lambda_{v_2 h_1} & \lambda_{v_3 h_1} & \lambda_{v_4 h_1} & \lambda_{v_5 h_1} & \lambda_{v_6 h_1} & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_{v_2 h_2} & \lambda_{v_3 h_2} & \lambda_{v_4 h_2} & \lambda_{v_5 h_2} & \lambda_{v_6 h_2} & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \lambda_{v_3 h_3} & \lambda_{v_4 h_3} & \lambda_{v_5 h_3} & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \lambda_{v_4 h_4} & 0 & \lambda_{v_6 h_4} & \lambda_{v_7 h_4} & \lambda_{v_8 h_4} & \lambda_{v_9 h_4} \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*}$$

The graph is not BB-identifiable as it is not full-ZUTA. To see that it is not AR-identifiable, delete the row of

![]() $\Lambda $

indexed by

$\Lambda $

indexed by

![]() $v_4$

. If we form two

$v_4$

. If we form two

![]() $4 \times 4$

-matrices out of the remaining eight rows, then one of these matrices has to contain at least two rows indexed by

$4 \times 4$

-matrices out of the remaining eight rows, then one of these matrices has to contain at least two rows indexed by

![]() $v_7$

,

$v_7$

,

![]() $v_8,$

or

$v_8,$

or

![]() $v_9$

. This matrix has at most rank three, which disproves AR-identifiability. Another example that is neither AR- nor BB-identifiable is the graph in Figure 1. Using the criteria we develop in the next section, we can certify identifiability of both graphs (see also Example 4.9).

$v_9$

. This matrix has at most rank three, which disproves AR-identifiability. Another example that is neither AR- nor BB-identifiable is the graph in Figure 1. Using the criteria we develop in the next section, we can certify identifiability of both graphs (see also Example 4.9).

Figure 6 Sparse factor analysis graphs that is not AR-identifiable nor BB-identifiable.

Finally, we note that BB-identifiability subsumes AR-identifiability for full-ZUTA graphs.

Corollary 3.11. Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a full-ZUTA graph with

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a full-ZUTA graph with

![]() $|\mathcal {H}|\geq 2$

latent nodes that is AR-identifiable. Then, G is also BB-identifiable.

$|\mathcal {H}|\geq 2$

latent nodes that is AR-identifiable. Then, G is also BB-identifiable.

However, there are full-ZUTA graphs that are BB- but not AR-identifiable. The smallest example has

![]() $|V|=8$

observed nodes and

$|V|=8$

observed nodes and

![]() $|\mathcal {H}|=4$

latent nodes.

$|\mathcal {H}|=4$

latent nodes.

4 Main identifiability results

In this section, we derive novel graphical criteria that are sufficient for generic sign-identifiability in sparse factor analysis graphs. As we will show, the criteria strictly generalize AR- and BB-identifiability for ZUTA graphs and are capable of certifying identifiability of models not covered by the AR- nor BB-criterion.

4.1 Matching criterion

Our first criterion takes the form of a recursive procedure and is based on a graphical extension of the Anderson–Rubin criterion that can be applied locally at a given node. In the AR criterion, for each observed node

![]() $v \in V$

, we need to find disjoint sets

$v \in V$

, we need to find disjoint sets

![]() $U,W \subseteq V\setminus \{v\}$

with

$U,W \subseteq V\setminus \{v\}$

with

![]() $|U|=|W|=|\mathcal {H}|$

such that

$|U|=|W|=|\mathcal {H}|$

such that

![]() $\det (\Lambda _{U,\mathcal {H}}) \neq 0$

and

$\det (\Lambda _{U,\mathcal {H}}) \neq 0$

and

![]() $\det (\Lambda _{W,\mathcal {H}}) \neq 0$

. This is equivalent to

$\det (\Lambda _{W,\mathcal {H}}) \neq 0$

. This is equivalent to

![]() $\det ([\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }]_{U,W}) \neq 0$

. Our main idea is to derive, and locally apply, a modified version of the AR criterion that also considers sets

$\det ([\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }]_{U,W}) \neq 0$

. Our main idea is to derive, and locally apply, a modified version of the AR criterion that also considers sets

![]() $U,W$

with cardinality smaller than

$U,W$

with cardinality smaller than

![]() $|\mathcal {H}|$

. In doing so, we need to ensure that

$|\mathcal {H}|$

. In doing so, we need to ensure that

![]() $\det ([\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }]_{U,W}) \neq 0$

, i.e., we need to characterize when minors of

$\det ([\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }]_{U,W}) \neq 0$

, i.e., we need to characterize when minors of

![]() $\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

vanish. This can be achieved via the concept of trek separation (Sullivant et al., Reference Sullivant, Talaska and Draisma2010) and leads to the following definition.

$\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

vanish. This can be achieved via the concept of trek separation (Sullivant et al., Reference Sullivant, Talaska and Draisma2010) and leads to the following definition.

Definition 4.1. Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph, and let

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph, and let

![]() $A,B\subseteq V$

be two subsets of equal cardinality,

$A,B\subseteq V$

be two subsets of equal cardinality,

![]() $|A|=|B|=n$

. A matching of A and B is a system

$|A|=|B|=n$

. A matching of A and B is a system

![]() $\Pi = \{\pi _1, \ldots , \pi _n\}$

consisting of paths of the form

$\Pi = \{\pi _1, \ldots , \pi _n\}$

consisting of paths of the form

where all

![]() $h_i \in \mathcal {H}$

, and

$h_i \in \mathcal {H}$

, and

![]() $\{v_1, \ldots , v_n\}=A$

and

$\{v_1, \ldots , v_n\}=A$

and

![]() $\{w_1, \ldots , w_n\}=B$

. A matching is intersection-free if the

$\{w_1, \ldots , w_n\}=B$

. A matching is intersection-free if the

![]() $h_i$

are all distinct, and a matching avoids

$h_i$

are all distinct, and a matching avoids

![]() $\mathcal {L} \subseteq \mathcal {H}$

if

$\mathcal {L} \subseteq \mathcal {H}$

if

![]() $\mathcal {L} \cap \{h_1, \ldots , h_n\} = \emptyset $

.

$\mathcal {L} \cap \{h_1, \ldots , h_n\} = \emptyset $

.

Example 4.2. Consider the sets

![]() $A=\{v_2,v_3\}$

and

$A=\{v_2,v_3\}$

and

![]() $B=\{v_4,v_5\}$

in the graph from Figure 5a. The system

$B=\{v_4,v_5\}$

in the graph from Figure 5a. The system

![]() $ \{v_2 \leftarrow h_1 \rightarrow v_3, v_4 \leftarrow h_2 \rightarrow v_5\} $

is an intersection-free matching of A and B. If instead

$ \{v_2 \leftarrow h_1 \rightarrow v_3, v_4 \leftarrow h_2 \rightarrow v_5\} $

is an intersection-free matching of A and B. If instead

![]() $A=\{v_1,v_2,v_3\}$

and

$A=\{v_1,v_2,v_3\}$

and

![]() $B=\{v_1,v_4,v_5\}$

, then any matching between A and B has an intersection. An example is given by the set of paths

$B=\{v_1,v_4,v_5\}$

, then any matching between A and B has an intersection. An example is given by the set of paths

![]() $ \{v_1 \leftarrow h_1 \rightarrow v_1, v_2 \leftarrow h_1 \rightarrow v_3, v_4 \leftarrow h_2 \rightarrow v_5\} $

that intersects in the latent node

$ \{v_1 \leftarrow h_1 \rightarrow v_1, v_2 \leftarrow h_1 \rightarrow v_3, v_4 \leftarrow h_2 \rightarrow v_5\} $

that intersects in the latent node

![]() $h_1$

.

$h_1$

.

Our main tool is a lemma that considers determinants of submatrices of

![]() $\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

for

$\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }$

for

![]() $\Lambda \in \mathbb {R}^D$

. Here, we view the determinant as a polynomial in the indeterminates

$\Lambda \in \mathbb {R}^D$

. Here, we view the determinant as a polynomial in the indeterminates

![]() $\lambda _{vh}$

, that is, we view it as an algebraic object without reference to its evaluation at specific values.

$\lambda _{vh}$

, that is, we view it as an algebraic object without reference to its evaluation at specific values.

Lemma 4.3. Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph, and let

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph, and let

![]() $\Lambda \in \mathbb {R}^D$

. For two subsets

$\Lambda \in \mathbb {R}^D$

. For two subsets

![]() $A, B \subseteq V$

of equal cardinality,

$A, B \subseteq V$

of equal cardinality,

![]() $\det ( [\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }]_{A,B} )$

is not the zero polynomial if and only if there is an intersection-free matching of A and B.

$\det ( [\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }]_{A,B} )$

is not the zero polynomial if and only if there is an intersection-free matching of A and B.

Applying Lemma 4.3 to Anderson and Rubin’s theorem yields the following corollary.

Corollary 4.4. Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph that satisfies ZUTA. Then, G is AR-identifiable if and only if for all

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph that satisfies ZUTA. Then, G is AR-identifiable if and only if for all

![]() $v \in V$

, there exist two disjoint sets

$v \in V$

, there exist two disjoint sets

![]() $W,U \subseteq V \setminus \{v\}$

with

$W,U \subseteq V \setminus \{v\}$

with

![]() $|W|=|U|=|\mathcal {H}|$

such that there is an intersection-free matching between W and U.

$|W|=|U|=|\mathcal {H}|$

such that there is an intersection-free matching between W and U.

Example 4.5. We saw in Example 3.5 that the graph in Figure 3 is AR-identifiable. Corollary 4.4 allows us to certify AR-identifiability in a fully graphical way without relating to the factor loading matrix. For example, for node

![]() $v_5$

, we observe that the two sets

$v_5$

, we observe that the two sets

![]() $U=\{v_1,v_2\}$

and

$U=\{v_1,v_2\}$

and

![]() $W=\{v_3,v_4\}$

have intersection-free matching

$W=\{v_3,v_4\}$

have intersection-free matching

![]() $ \{v_1 \leftarrow h_1 \rightarrow v_2, v_3 \leftarrow h_2 \rightarrow v_4\}. $

$ \{v_1 \leftarrow h_1 \rightarrow v_2, v_3 \leftarrow h_2 \rightarrow v_4\}. $

Remark 4.6. The use of matchings to verify AR-identifiability also appears in recent work of Hosszejni and Frühwirth-Schnatter (Reference Hosszejni and Frühwirth-Schnatter2026, Proposition 2) who make a connection between computing classical maximal matchings in bipartite graphs and verifying AR-identifiability. They consider matchings that are defined on duplicate bipartite graphs, which are constructed by first duplicating all latent nodes of the original graph and then duplicating the edges connecting these new latent nodes to the original observed nodes. The criterion of Hosszejni and Frühwirth-Schnatter (Reference Hosszejni and Frühwirth-Schnatter2026) then establishes AR-identifiability by checking whether the duplicate bipartite graph admits a maximal matching that covers all latent nodes, both the original and their duplicates. However, this approach is not feasible when we modify Corollary 4.4 to be locally applicable, as we do next. The reason is that if not all latent nodes are part of the matching, we do not know a priori which nodes we should consider in the bipartite graph. Therefore, we consider intersection-free matchings defined with respect to the original factor analysis graph.

We are now ready to define our new matching criterion, which operates “node-wise” and considers generic sign-identifiability for individual latent nodes

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$

.

$h \in \mathcal {H}$

.

Definition 4.7. Fix a latent node

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$

in the factor analysis graph

$h \in \mathcal {H}$

in the factor analysis graph

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

. A tuple

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

. A tuple

![]() $(v, W, U, S) \in V \times 2^{V} \times 2^{V} \times 2^{ \mathcal {H} \setminus \{h\}}$

satisfies the matching criterion with respect to h if

$(v, W, U, S) \in V \times 2^{V} \times 2^{V} \times 2^{ \mathcal {H} \setminus \{h\}}$

satisfies the matching criterion with respect to h if

-

(i)

$\text {pa}(v)\setminus S = \{h\}$

and

$\text {pa}(v)\setminus S = \{h\}$

and

$v \not \in W \cup U$

;

$v \not \in W \cup U$

; -

(ii) W and U are disjoint, nonempty sets of equal cardinality;

-

(iii) there exists an intersection-free matching of W and U that avoids S;

-

(iv) there is no intersection-free matching of

$\{v\} \cup W$

and

$\{v\} \cup W$

and

$\{v\} \cup U$

that avoids S.

$\{v\} \cup U$

that avoids S.

If

![]() $(v, W, U, S)$

satisfies the matching criterion with respect to h, then Condition (iii) ensures

$(v, W, U, S)$

satisfies the matching criterion with respect to h, then Condition (iii) ensures

![]() $\det ([\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }]_{W,U}) \neq 0$

, and Condition (iv) ensures

$\det ([\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }]_{W,U}) \neq 0$

, and Condition (iv) ensures

![]() $\det ([\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }]_{\{v\} \cup W,\{v\} \cup U}) = 0$

after removing the nodes in S from the graph. The Laplace expansion of determinants then allows us to find a rational formula for

$\det ([\Lambda \Lambda ^{\top }]_{\{v\} \cup W,\{v\} \cup U}) = 0$

after removing the nodes in S from the graph. The Laplace expansion of determinants then allows us to find a rational formula for

![]() $\lambda _{vh}^2$

in terms of the entries of the covariance matrix. We can thus identify

$\lambda _{vh}^2$

in terms of the entries of the covariance matrix. We can thus identify

![]() $\lambda _{vh}$

up to sign. Having identified parameter

$\lambda _{vh}$

up to sign. Having identified parameter

![]() $\lambda _{v h}$

for one child

$\lambda _{v h}$

for one child

![]() $v \in \text {ch}(h)$

, it is easy to certify sign-identifiability of h, i.e., to identify the remaining parameters

$v \in \text {ch}(h)$

, it is easy to certify sign-identifiability of h, i.e., to identify the remaining parameters

![]() $\lambda _{uh}$

for

$\lambda _{uh}$

for

![]() $u \in \text {ch}(h) \setminus \{v\}$

up to the same sign. This is formalized in our first main result.

$u \in \text {ch}(h) \setminus \{v\}$

up to the same sign. This is formalized in our first main result.

Theorem 4.8 (M-identifiability)

Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph, and fix a latent node

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph, and fix a latent node

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$

. Suppose that the tuple

$h \in \mathcal {H}$

. Suppose that the tuple

![]() $(v, W, U, S) \in V \times 2^{V} \times 2^{V} \times 2^{ \mathcal {H} \setminus \{h\}}$

satisfies the matching criterion with respect to h. If all nodes

$(v, W, U, S) \in V \times 2^{V} \times 2^{V} \times 2^{ \mathcal {H} \setminus \{h\}}$

satisfies the matching criterion with respect to h. If all nodes

![]() $\ell \in S$

are generically sign-identifiable, then h is generically sign-identifiable.

$\ell \in S$

are generically sign-identifiable, then h is generically sign-identifiable.

Theorem 4.8 provides a way to recursively certify generic sign-identifiability of a factor analysis graph by checking whether all nodes

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$

are generically sign-identifiable (recall Lemma 2.4). If generic sign-identifiability can be certified recursively by Theorem 4.8, then we call the factor analysis graph M-identifiable. The details of an efficient algorithm to check M-identifiability using max-flow techniques are described in Appendix B of the Supplementary Material.

$h \in \mathcal {H}$

are generically sign-identifiable (recall Lemma 2.4). If generic sign-identifiability can be certified recursively by Theorem 4.8, then we call the factor analysis graph M-identifiable. The details of an efficient algorithm to check M-identifiability using max-flow techniques are described in Appendix B of the Supplementary Material.

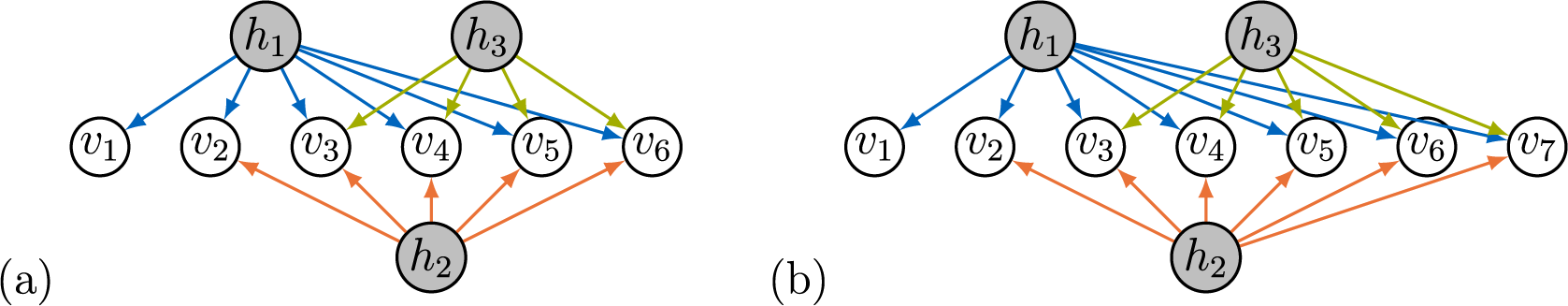

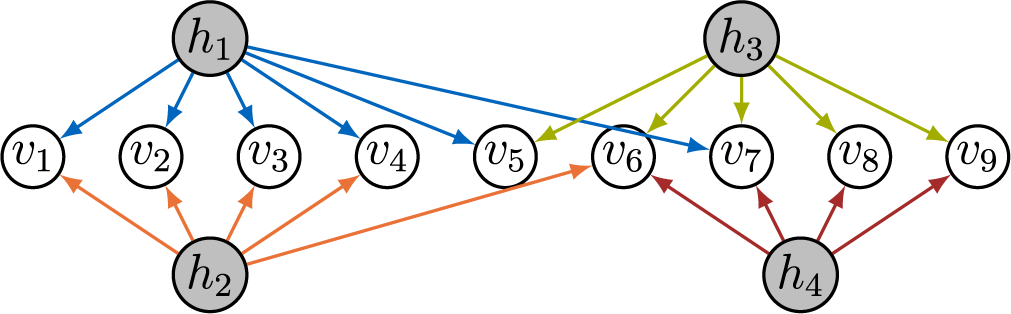

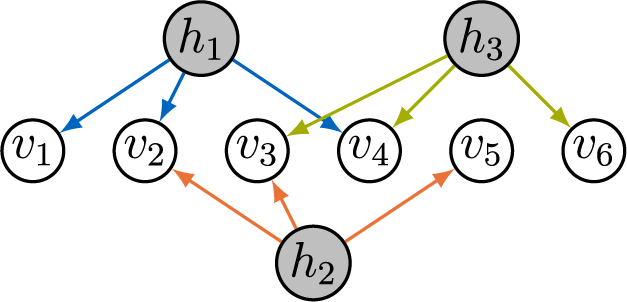

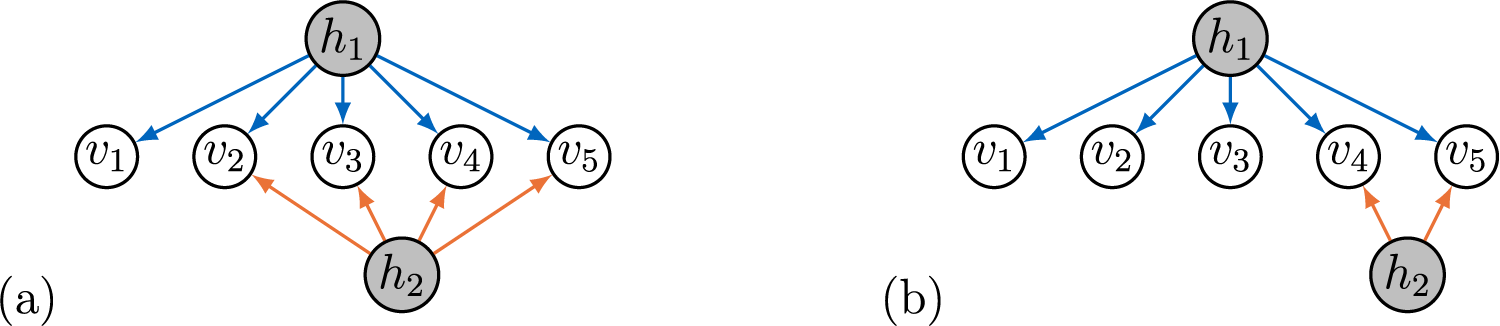

Example 4.9. The factor analysis graph in Figure 7 is not AR-identifiable since

![]() $|V|=2|\mathcal {H}|$

. However, it is M-identifiable. We recursively check all latent nodes

$|V|=2|\mathcal {H}|$

. However, it is M-identifiable. We recursively check all latent nodes

![]() $\mathcal {H} = \{ h_1, h_2, h_3 \}$

.

$\mathcal {H} = \{ h_1, h_2, h_3 \}$

.

-

h 1: Take

$v=v_1$

,

$v=v_1$

,

$S=\emptyset $

,

$S=\emptyset $

,

$U=\{v_2,v_6\}$

, and

$U=\{v_2,v_6\}$

, and

$W=\{v_3,v_4\}$

. Conditions (i) and (ii) are easily checked, and for (iii), an intersection-free matching is given by

$W=\{v_3,v_4\}$

. Conditions (i) and (ii) are easily checked, and for (iii), an intersection-free matching is given by

$\{v_2 \leftarrow h_1 \rightarrow v_3, v_6 \leftarrow h_2 \rightarrow v_4\}$

. To verify (iv), note that

$\{v_2 \leftarrow h_1 \rightarrow v_3, v_6 \leftarrow h_2 \rightarrow v_4\}$

. To verify (iv), note that

$\text {pa}(\{v\} \cup U) \cap \text {pa}(\{v\} \cup W) = \{h_1, h_2\}$

, which implies that there cannot exist an intersection-free matching of

$\text {pa}(\{v\} \cup U) \cap \text {pa}(\{v\} \cup W) = \{h_1, h_2\}$

, which implies that there cannot exist an intersection-free matching of

$\{v\} \cup U$

and

$\{v\} \cup U$

and

$\{v\} \cup W$

.

$\{v\} \cup W$

. -

h 2: Take

$v=v_2$

,

$v=v_2$

,

$S=\{h_1\}$

,

$S=\{h_1\}$

,

$U=\{v_3\}$

, and

$U=\{v_3\}$

, and

$W=\{v_6\}$

. The matching

$W=\{v_6\}$

. The matching

$\{v_3 \leftarrow h_2 \rightarrow v_6\}$

is intersection-free, and

$\{v_3 \leftarrow h_2 \rightarrow v_6\}$

is intersection-free, and

$(\text {pa}(\{v\} \cup U) \cap \text {pa}(\{v\} \cup W)) \setminus S = \{h_2\}$

implies that (iv) holds.

$(\text {pa}(\{v\} \cup U) \cap \text {pa}(\{v\} \cup W)) \setminus S = \{h_2\}$

implies that (iv) holds. -

h 3: Take

$v=v_3$

,

$v=v_3$

,

$S=\{h_1,h_2\}$

,

$S=\{h_1,h_2\}$

,

$U=\{v_4\}$

, and

$U=\{v_4\}$

, and

$W=\{v_5\}$

. The matching

$W=\{v_5\}$

. The matching

$\{v_4 \leftarrow h_3 \rightarrow v_5\}$

is intersection-free, and

$\{v_4 \leftarrow h_3 \rightarrow v_5\}$

is intersection-free, and

$(\text {pa}(\{v\} \cup U) \cap \text {pa}(\{v\} \cup W)) \setminus S = \{h_3\}$

implies that (iv) holds.

$(\text {pa}(\{v\} \cup U) \cap \text {pa}(\{v\} \cup W)) \setminus S = \{h_3\}$

implies that (iv) holds.

Note that the graphs in Figures 1 and 6 are also M-identifiable, which can be seen similarly.

Figure 7 M-identifiable sparse factor analysis graph.

Next, we show that M-identifiability subsumes AR-identifiability.

Corollary 4.10. Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph that satisfies ZUTA. Then:

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph that satisfies ZUTA. Then:

-

(i) If G is AR-identifiable, then it is also M-identifiable.

-

(ii) If G is full-ZUTA, then G is AR-identifiable if and only if it is M-identifiable.

Even though M-identifiability subsumes AR-identifiability, it can also only establish identifiability of graphs that satisfy ZUTA.

Corollary 4.11. Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph that is M-identifiable. Then, the factor analysis graph G satisfies ZUTA.

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph that is M-identifiable. Then, the factor analysis graph G satisfies ZUTA.

4.2 Extension of the matching criterion

By Corollary 4.10, M-identifiability subsumes AR-identifiability. However, it does not subsume BB-identifiability. For example, the full-ZUTA graph on

![]() $|V|=8$

observed nodes and

$|V|=8$

observed nodes and

![]() $|\mathcal {H}|=4$

latent nodes is BB- but not M-identifiable. We now provide a second criterion that can certify generic sign-identifiability of a set of latent nodes in a way that generalizes BB-identifiability. It operates by searching locally for full-ZUTA subgraphs

$|\mathcal {H}|=4$

latent nodes is BB- but not M-identifiable. We now provide a second criterion that can certify generic sign-identifiability of a set of latent nodes in a way that generalizes BB-identifiability. It operates by searching locally for full-ZUTA subgraphs

![]() $\widetilde {G}=(\widetilde {V}, \widetilde {D})$

that satisfy the condition

$\widetilde {G}=(\widetilde {V}, \widetilde {D})$

that satisfy the condition

![]() $|\widetilde {V}|+ |\widetilde {D}| < \binom {|\widetilde {V}|+1}{2}$

. Combining both criteria then yields an extension of the matching criterion. We start by defining the necessary concepts.

$|\widetilde {V}|+ |\widetilde {D}| < \binom {|\widetilde {V}|+1}{2}$

. Combining both criteria then yields an extension of the matching criterion. We start by defining the necessary concepts.

Definition 4.12. For a set

![]() $B \subseteq V$

of observed nodes, the set of joint parents of pairs in B is given by

$B \subseteq V$

of observed nodes, the set of joint parents of pairs in B is given by

Moreover, for another set

![]() $S \subseteq V$

, we say that an ordering

$S \subseteq V$

, we say that an ordering

![]() $\prec $

on the set S is a B-first-ordering if, for two elements

$\prec $

on the set S is a B-first-ordering if, for two elements

![]() $v,w \in S$

, it holds that

$v,w \in S$

, it holds that

![]() $v \prec w$

whenever

$v \prec w$

whenever

![]() $v \in B \cap S$

and

$v \in B \cap S$

and

![]() $w \in S \setminus B$

.

$w \in S \setminus B$

.

Said differently, a B-first-ordering on a set of nodes S is a block-ordering such that all elements in B come first.

Example 4.13. Consider the graph in Figure 7, and let

![]() $B=\{v_1,v_2,v_3\}$

. The joint parents are given by

$B=\{v_1,v_2,v_3\}$

. The joint parents are given by

![]() $\text {jpa}(B)=\{h_1,h_2\}$

. Moreover, for

$\text {jpa}(B)=\{h_1,h_2\}$

. Moreover, for

![]() $S = \{v_1,v_2,v_4,v_5\}$

, an example of a B-first ordering is given by

$S = \{v_1,v_2,v_4,v_5\}$

, an example of a B-first ordering is given by

![]() $v_2 \prec v_1 \prec v_5 \prec v_4$

.

$v_2 \prec v_1 \prec v_5 \prec v_4$

.

We now define a criterion that generalizes BB-identifiability. For

![]() $A \subseteq V \cup \mathcal {H}$

, we write

$A \subseteq V \cup \mathcal {H}$

, we write

![]() $G[A]=(A,D_A)$

for the induced subgraph of

$G[A]=(A,D_A)$

for the induced subgraph of

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

. The edge set

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

. The edge set

![]() $D_A=\{h \rightarrow v \in D: h, v \in A\}$

includes precisely those edges in D that have both endpoints in A.

$D_A=\{h \rightarrow v \in D: h, v \in A\}$

includes precisely those edges in D that have both endpoints in A.

Definition 4.14. Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph. We say that the tuple

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph. We say that the tuple

![]() $(B, S) \in 2^V \times 2^{\mathcal {H}}$

satisfies the local BB-criterion if

$(B, S) \in 2^V \times 2^{\mathcal {H}}$

satisfies the local BB-criterion if

-

(i) the induced subgraph

$\widetilde {G} = G[B \cup (\text {jpa}(B)\setminus S)]$

is a full-ZUTA graph;

$\widetilde {G} = G[B \cup (\text {jpa}(B)\setminus S)]$

is a full-ZUTA graph; -

(ii) for all

$h \in \text {jpa}(B)\setminus S$

, there is a B-first-ordering

$h \in \text {jpa}(B)\setminus S$

, there is a B-first-ordering

$\prec _h$

on

$\prec _h$

on

$\text {ch}(h)$

such that for all

$\text {ch}(h)$

such that for all

$v \in \text {ch}(h) \setminus B,$

there is

$v \in \text {ch}(h) \setminus B,$

there is

$u \in \text {ch}(h)$

with

$u \in \text {ch}(h)$

with

$u \prec _h v$

and

$u \prec _h v$

and

$\text {jpa}(\{v,u\}) \setminus S \subseteq \{\ell \in \text {jpa}(B)\setminus S: \ell \preceq _{\text {ZUTA}} h \}$

, where

$\text {jpa}(\{v,u\}) \setminus S \subseteq \{\ell \in \text {jpa}(B)\setminus S: \ell \preceq _{\text {ZUTA}} h \}$

, where

$\prec _{\text {ZUTA}}$

is the unique ZUTA-ordering on

$\prec _{\text {ZUTA}}$

is the unique ZUTA-ordering on

$\text {jpa}(B)\setminus S$

induced by

$\text {jpa}(B)\setminus S$

induced by

$\widetilde {G}$

;

$\widetilde {G}$

; -

(iii) for the edge set

$\widetilde {D}$

of the subgraph

$\widetilde {D}$

of the subgraph

$\widetilde {G}$

it holds that

$\widetilde {G}$

it holds that

$|B| + |\widetilde {D}| < \binom {|B|+1}{2}$

.

$|B| + |\widetilde {D}| < \binom {|B|+1}{2}$

.

Theorem 4.15. Let

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph and suppose that the tuple

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

be a factor analysis graph and suppose that the tuple

![]() $(B,S)\in 2^V \times 2^{\mathcal {H}}$

satisfies the local BB-criterion. If all nodes

$(B,S)\in 2^V \times 2^{\mathcal {H}}$

satisfies the local BB-criterion. If all nodes

![]() $\ell \in S$

are generically sign-identifiable, then all nodes

$\ell \in S$

are generically sign-identifiable, then all nodes

![]() $h \in \text {jpa}(B)\setminus S$

are generically sign-identifiable.

$h \in \text {jpa}(B)\setminus S$

are generically sign-identifiable.

Similar to M-identifiability, Theorem 4.15 allows us to recursively certify generic sign-identifiability of a factor analysis graph by checking whether all nodes

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$

are generically sign-identifiable (recall Lemma 2.4).

$h \in \mathcal {H}$

are generically sign-identifiable (recall Lemma 2.4).

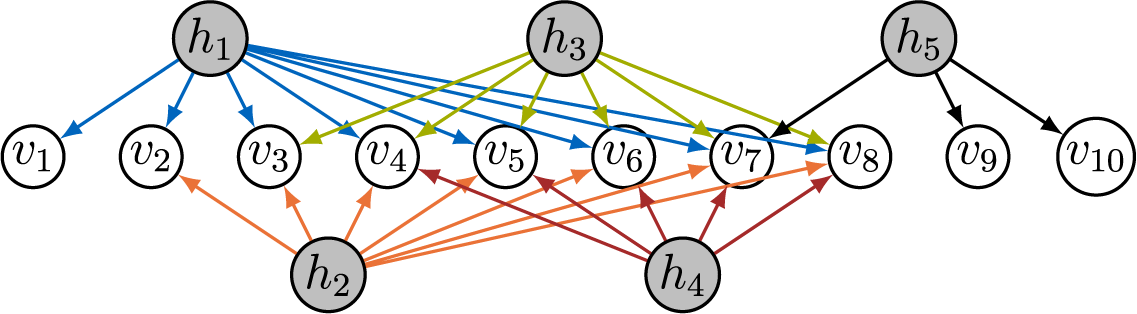

Example 4.16. We can use Theorem 4.15 to recursively certify generic sign-identifiability of all latent nodes of the graph displayed in Figure 8.

-

h 1, h 2: Take

$B=\{v_1, \ldots , v_5\}$

and

$B=\{v_1, \ldots , v_5\}$

and

$S=\emptyset $

such that

$S=\emptyset $

such that

$\text {jpa}(B)\setminus S = \{h_1,h_2\}$

. Observe that

$\text {jpa}(B)\setminus S = \{h_1,h_2\}$

. Observe that

$G[B \cup (\text {jpa}(B)\setminus S)]$

is a full-ZUTA graph such that Condition (iii) is satisfied. Note that the unique ZUTA-ordering on

$G[B \cup (\text {jpa}(B)\setminus S)]$

is a full-ZUTA graph such that Condition (iii) is satisfied. Note that the unique ZUTA-ordering on

$\text {jpa}(B)$

is given by

$\text {jpa}(B)$

is given by

$h_1 \prec _{\text {ZUTA}} h_2$

, i.e., to verify Condition (ii), we proceed according to this ordering on the latent nodes. The only child of

$h_1 \prec _{\text {ZUTA}} h_2$

, i.e., to verify Condition (ii), we proceed according to this ordering on the latent nodes. The only child of

$h_1$

that is not a member of B is

$h_1$

that is not a member of B is

$v_7$

. Take any ordering

$v_7$

. Take any ordering

$\prec _{h_1}$

on

$\prec _{h_1}$

on

$\text {ch}(h_1)$

such that

$\text {ch}(h_1)$

such that

$v_7$

is the largest node according to

$v_7$

is the largest node according to

$\prec _{h_1}$

. Then, the ordering

$\prec _{h_1}$

. Then, the ordering

$\prec _{h_1}$

is a B-first-ordering and

$\prec _{h_1}$

is a B-first-ordering and

$v_1 \prec _{h_1} v_7$

. Moreover, observe that

$v_1 \prec _{h_1} v_7$

. Moreover, observe that

$\text {jpa}(\{v_1,v_7\}) = \{h_1\}$

. Similarly, we can take any ordering

$\text {jpa}(\{v_1,v_7\}) = \{h_1\}$

. Similarly, we can take any ordering

$\prec _{h_2}$

on

$\prec _{h_2}$

on

$\text {ch}(h_2)$

such that

$\text {ch}(h_2)$

such that

$v_6$

is the largest node according to

$v_6$

is the largest node according to

$\prec _{h_2}$

. Since

$\prec _{h_2}$

. Since

$\text {jpa}(\{v_1,v_6\}) = \{h_2\}$

, we conclude that Condition (ii) is satisfied.

$\text {jpa}(\{v_1,v_6\}) = \{h_2\}$

, we conclude that Condition (ii) is satisfied. -

h 3, h 4: Take

$U=\{v_5, \ldots , v_9\}$

and

$U=\{v_5, \ldots , v_9\}$

and

$S=\{h_1,h_2\}$

such that

$S=\{h_1,h_2\}$

such that

$\text {jpa}(B)\setminus S = \{h_3,h_4\}$

. It is easy to verify that Conditions (i) and (iii) are satisfied. Moreover, we have that

$\text {jpa}(B)\setminus S = \{h_3,h_4\}$

. It is easy to verify that Conditions (i) and (iii) are satisfied. Moreover, we have that

$\text {ch}(h_i)\setminus B = \emptyset $

for

$\text {ch}(h_i)\setminus B = \emptyset $

for

$i=3,4$

, that is, Condition (ii) is trivially satisfied.

$i=3,4$

, that is, Condition (ii) is trivially satisfied.

On the other hand, each observed node in the graph in Figure 8 has at least two latent parents. This implies that ZUTA is not satisfied and hence, due to Corollary 4.11, the graph is not M-identifiable.

Figure 8 Graph that is certified to be generically sign-identifiable by Theorem 4.15.

Next, we show that the recursive application of Theorem 4.15 subsumes BB-identifiability, that is, we show equivalence on full-ZUTA graphs. Crucially, Theorem 4.15 is also able to certify generic sign-identifiability of sparse graphs.

Corollary 4.17. A full-ZUTA graph

![]() $G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

is BB-identifiable if and only if generic sign-identifiability of G can be certified by recursively applying Theorem 4.15.

$G=(V \cup \mathcal {H}, D)$

is BB-identifiable if and only if generic sign-identifiability of G can be certified by recursively applying Theorem 4.15.

We obtain our final criterion by combining Theorems 4.8 and 4.15 iteratively in a recursive algorithm. We call a factor analysis graph extended M-identifiable if generic sign-identifiability can be certified recursively by Theorems 4.8 and 4.15 for all nodes

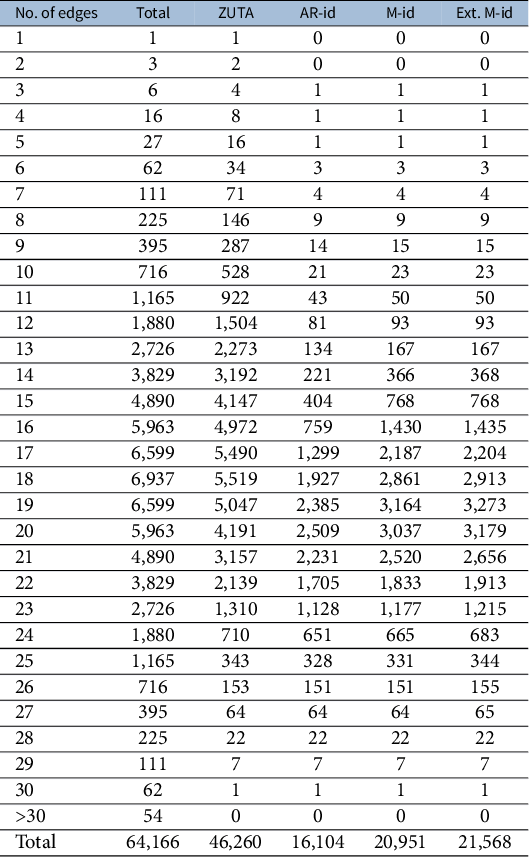

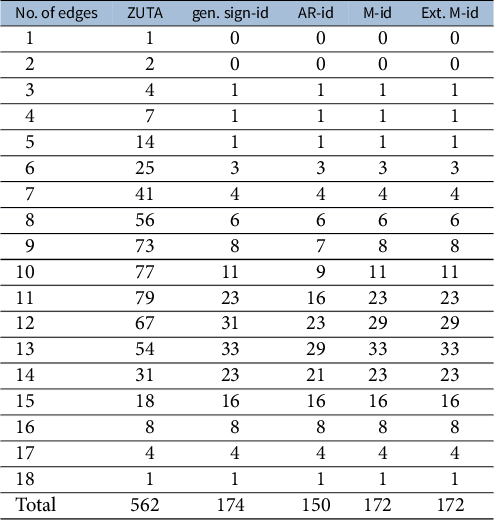

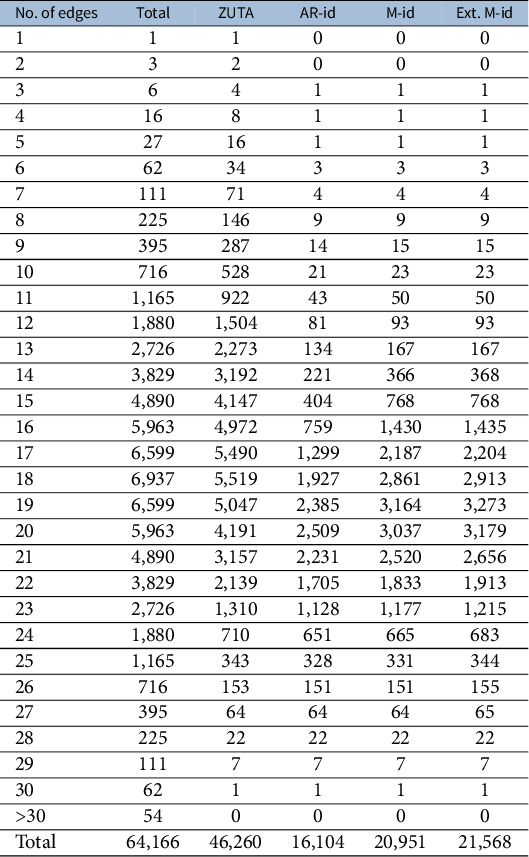

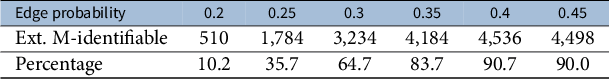

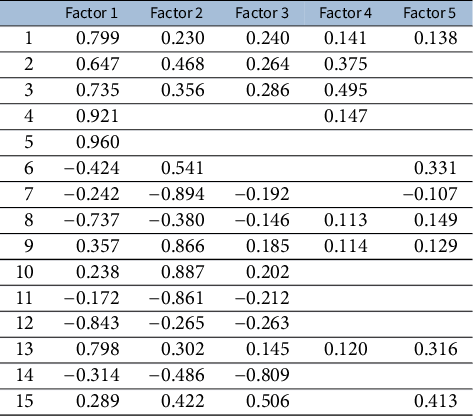

![]() $h \in \mathcal {H}$