Introduction

Within the field of radiation oncology (RO), the production and delivery of high-quality radiation therapy plans (RTP) are of the utmost importance to optimize patient outcomes. Variance in RTP can negatively impact treatment outcomes with errors leading to decreased local tumour control and increased toxicity rates, significantly impacting a patient’s quality of life. Reference Hesse1–Reference Segedin and Petric13 RTP has become more complicated in recent years with the move towards 3-dimensional CT-based RTP, which allows for greater accuracy of target coverage and sparing of surrounding tissue; however, it is more difficult to master because it requires greater understanding of imaging-based 3D anatomy and tumour physiology, including drainage pathways. Reference McDowell and Corry9,Reference Segedin and Petric13–Reference Cooper16 Compared to conventional RT methods, conformal RT methods have been noted to have significantly improved patient outcomes with greater physician experience, which can be difficult to achieve for low-volume institutions with primarily general radiation oncologists. Reference Segedin and Petric13,Reference Boero14,Reference Gogineni17 Due to this, quality assurance (QA) has been increasingly prioritized to ensure plan quality and subsequent clinical success.

One of the most common QA protocols implemented is institutional peer review (PR) programmes. The implementation of the PR process has been recommended by a multitude of professional organizations, including American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), American College of Radiology (ACR) and Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR), praising the concept of a multidisciplinary discussion and RTP review and its likely subsequent reduction of observer errors. Reference Farris2,Reference Martin-Garcia12,Reference Marks18–Reference Duggar20 For institutions with PR programmes, a majority of attending radiation oncologists have consistently agreed on its usefulness in both clinical outcomes and cultivating a collaborative departmental culture. Reference McDowell and Corry9,Reference Hamilton21,Reference Brundage22 Despite the consistent praise and widespread recommendations for PR, there remains both a lack of standardization across institutions and a formal guideline on universal implementation. Reference Lewis4,Reference McDowell and Corry9,Reference Gogineni17,Reference Nielsen23 For institutions undertaking PRs, the details are often variable with differential focus on key aspects of the RTP process and variance in the subsites spotlighted, obscuring institutional comparison. Reference Farris2,Reference Fong15,Reference Nielsen23 The most common execution of RTP PR currently prevails in the form of generalized ‘chart rounds’ with a multidisciplinary review of cases by physicians, physicists, dosimetrists and others involved in the patient’s RT care plan. Reference Hesse1,Reference Marks18,Reference Lawrence24,Reference Zairis25 Additionally, high discourse remains regarding the current standard of care with PR following RTP and the subsequent concerns of deciding between time efficacy versus potential detrimental outcomes when modifications are suggested. Reference Farris2,Reference Cox6

Among the differing components of the RTP process, contouring is a significant driver of treatment plan quality and subsequent outcomes. Contouring and target volume delineation involve defining the tumour, organs at risk (OAR) and avoidance structures to optimize radiation delivery to the desired site and minimize unwanted radiation side effects. 11 Inappropriate contouring can result in misses of critical areas, resulting in persistent or recurrent disease; conversely, a larger-than-necessary target volume delineation can inappropriately affect surrounding structures. Reference McDowell and Corry9,Reference Segedin and Petric13,Reference Cooper16,Reference Nuyts26 Despite its impact, it is currently disproportionately represented in PR with few institutions having a dedicated contouring PR or including target volume delineation within institutional RO PR. Institutional PR studies, including contouring, have observed a substantial portion of errors being traced to target volume delineation and, subsequently, designate contouring as a critical aspect in the RTP system requiring careful observation. Reference Hesse1,Reference Farris2,Reference Lewis4–Reference Cox6,Reference Rosenthal8,Reference McDowell and Corry9,Reference Martin-Garcia12,Reference Fong15,Reference Gogineni17,Reference Brundage22,Reference Zairis25 It is well-established that target volume delineation is susceptible to inter-physician variability with site-specific experience, individualistic conventions and departmental standard of care playing a large role. Reference McDowell and Corry9,Reference Segedin and Petric13,Reference Fong15 With the adoption of conformal RT methods, the impact and difficulty of image interpretation on disease control rise. Reference McDowell and Corry9,Reference Segedin and Petric13,Reference Fong15 The potential greater variability in image interpretation can result in prominent effect on critical target volume delineation that potentially could be minimized through the PR process but is often overlooked.

Additionally, the difficulty of contouring can be exacerbated by the site treated. Historically, head and neck (HN) cancers are one of the most difficult sites to contour due to the close proximity to multiple small critical structures, inter-patient variance and complex anatomical organization, prompting one of the highest inter-physician variabilities in contouring. Reference Nielsen23,Reference Nuyts26 Additionally, certain HN cancers have a variable natural history with extensive spread, further exacerbating contouring difficulty. Reference Rosenthal8,Reference Garden27 Ultimately, HN contours are more susceptible to detrimental observer errors with a larger dosimetric impact, up to 10 Gy, substantially influencing tumour control and patient quality of life. 28 Therefore, multiple studies have called for the wider implementation of QA to address contouring errors for individual radiation oncologists and improve institutional consistency in the production of high-quality treatment plans. Reference McDowell and Corry9,Reference Gwynne10,Reference Martin-Garcia12,28–Reference Rouette30 For complex sites, such as HN cancers, it has been noted that, contrary to the current gold standard, PR or similar methods should occur prior to the creation of RTP. As contouring is a major upstream weak link for HN cancers and has significant impact on patient prognosis, the loss of time and resources in revising post RTP creation is a prevailing shortcoming in the current standard of care. Reference Lewis4,Reference Cox6,Reference Rosenthal8,Reference Fong15,Reference Marks18,Reference Roques31

In this study, we report the outcomes of a formal HN contouring and target delineation prospective PR at our institution and its impact on independent attending physician (AP) and institutional contouring skills.

Materials and Methods

This single-institution prospective study reported outcomes of a formal HN contouring PR process. A pilot phase for this quality project was conducted for a 7-month period in 2018, followed by a maintenance phase from 2019 to 2023. All HN cancer patients who undergo external beam radiotherapy in our department are required to undergo contour peer review prior to radiation treatment planning (RTP). A PR task item was built into the task list of the electronic medical record (EMR) to document the PR process.

Contours were independently completed by the treating AP on the RTP CT scan. For each individual case, the AP utilized appropriate supportive information when available, including diagnostic imaging fused to the treatment planning CT, clinical examination including scope exam results, operative notes and surgical pathology notes. The contours were then formally presented either at the institution’s weekly scheduled HN PR meeting or additional ad hoc sessions as needed to keep RTP on schedule. PR sessions were attended by all available HN APs and RPs on HN service rotations, with the requirement that at least one additional HN AP was present. All contours underwent a slice-by-slice review and were assigned a contour grade based on the collective determination of the PR group. Definitions of contour grades were as follows: R0 (no change), R1 (minor revision, not high risk) or R2 (major revision, deemed high risk to negatively impact LC). Appropriate feedback was provided by the entire RO HN PR team for each case. If revisions were required, the treating AP would complete these. All revisions recommended were implemented by the treating AP prior to task completion. The PR task would then be completed in the EMR with contour grades recorded. Contours were expected to be completed, peer-reviewed, and ready for RTP within 48 hours after deployment of the PR task. Dosimetry did not start RTP until the PR task was completed.

The trend in contour grade was observed for the RO HN department over the initial 7-month pilot phase as well as the maintenance phase from 2019 to 2023. Changes in contour grade were observed for each RO HN AP as well as overall physician group. Contour grades were additionally evaluated by general HN subsites, including ipsilateral neck, larynx/hypopharynx/thyroid, oral cavity/oropharynx and sinonasal/base of skull (BOS) to determine if a correlation existed between subsite and mean contour grade. The Cochran-Armitage trend test, utilizing SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute Inc.), was performed to determine if each contour grade trend was significant over time.

Results

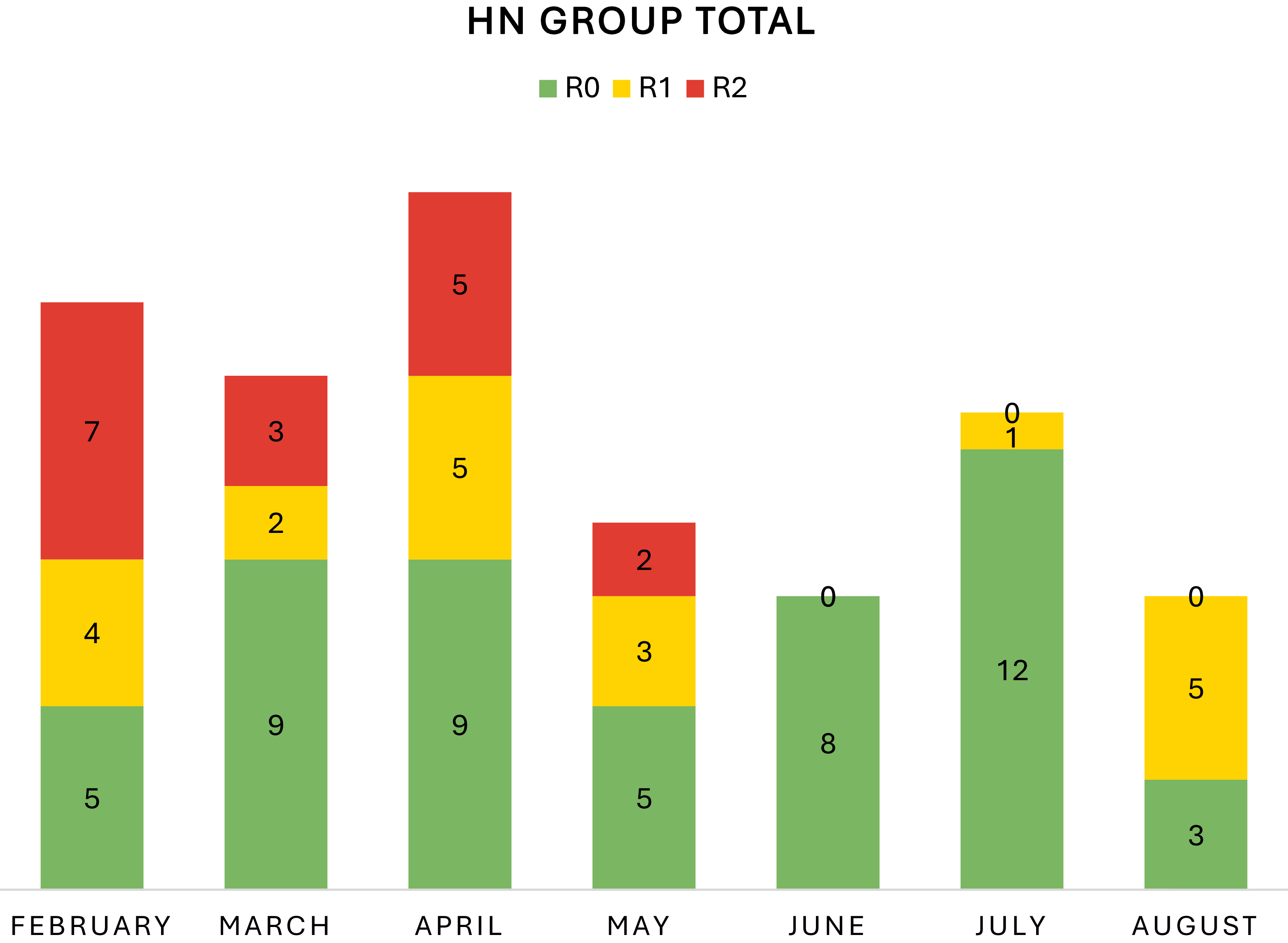

Over the course of the study’s 7-month pilot phase in 2018, 88 patients underwent HN PR and contour grading. The study was partaken by 4 RO APs in the first 3 months, while 3 RO APs participated for the entirety of the pilot phase. This was due to one part-time oncologist rotating off HN disease site to treat a different disease site in-order-to meet practice needs. During this phase, the contours were graded as follows: R0 (N = 51), R1 (N = 20) and R2 (N = 17). For the collective physician group, the number of R2s decreased over time with month 1 (N = 7), month 2 (N = 3), month 3 (N = 5), month 4 (N = 2) and months 5–7 (N = 0) (p-0.0001) (Figure 1). Conversely, the total number of R0s improved over time with month 1 (N = 5), months 2–3 (N = 9), month 4 (N = 5), month 5 (N = 8), month 6 (N = 12) and month 7 (N = 3) (p = 0.0203) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Change in revisions across the training period. Over the pilot study from February–August 2018, the number of R2 revisions decreased with time (p = 0.0001). The number of R0 revisions increased with time (p = 0.0203).

For each individual RO AP who participated for the entirety of the study, a similar objective reduction in R2 revisions was observed. For Oncologist A, month 1 (N = 2), month 2 (N = 1), month 3 (N = 2), month 4 (N = 1) and month 5–7 (N = 0) (Figure 2A). For Oncologist B, month 1 (N = 2), months 2–4 (N = 1) and months 5–7 (N = 0) (Figure 2B). For Oncologist C, months 1 and 3 (N = 1) and months 2, 4–7 (N = 0) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Change in revisions per oncologist across the training period. Over the pilot study from February–August 2018, each individual radiation oncologist participating in the review’s entirety demonstrated reduction in R2 revisions. (A): Oncologist A’s contour grades over time. (B): Oncologist B’s contour grades over time. (C): Oncologist C’s contour grades over time.

Over the course of the pilot phase, the R2 revisions objectively decreased for the 4 major HN subsites. For the ipsilateral neck, months 2–3 (N = 2) and months 4–7 (N = 0) (Figure 3A). For the larynx/hypopharynx/thyroid, month 1 (N = 2), months 2 (N = 0), month 3 (N = 1) and months 5–7 (N = 0) (Figure 3B). For the oral cavity/oropharynx, month 1 (N = 5), month 2 (N = 1), month 3 (N = 0), month 4 (N = 1) and months 5–7 (N = 0) (Figure 3C). For the sinonasal/BOS, months 1–2 (N = 0), month 3 (N = 2), month 4 (N = 1) and months 5-7 (N = 0) (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Change in revisions per subsite across the training period. Over the pilot study from February–August 2018, the number of R2 revisions decreased overall with time for each major site. (A) Contour grades over time for the ipsilateral neck. (B): Contour grades over time for the larynx, hypopharynx, and thyroid. (C): Contour grades over time for the oral cavity/oropharynx. (D): Contour grades over time for the sinonasal/BOS.

Following the completion of the pilot phase in 2018, the HN PR system was continued into a maintenance phase from 2019 to 2023. During the maintenance phase, 692 HN patient contours underwent contour grading; however, only 493 patients were included in this analysis of RO AP evaluation as 199 were representative of RP scores. Throughout the maintenance phase, all 3 RO APs demonstrated a stable low major revision rate of less than 3 R2 revisions per year.

Discussion

This single-institution prospective study illustrates that implementation of an HN contour PR system objectively improves contour quality on individual and institutional scales during the pilot phase. During the series’ 7-month pilot phase, we observe a statistically significant decrease in R2 revisions over time for each AP and the collective group, signifying a reduced need for major modifications. Additionally, we also observe a statistically significant improvement in R0 revisions over time for each AP and the collective group, indicating a more consistent production of high-quality target contours. The combination of these two trends suggests the PR process results in improved contour quality, which likely results in better RTP, likely ensuring high rates of local control. The decrease in progressive R2 reductions persists when considering each of the 4 major HN subsites. All subsites demonstrated contour grade improvement over the pilot phase. The oral cavity/oropharynx subsite received the greatest amount of R2 modifications, which is consistent with past studies showcasing the oropharynx as the site most prone to contouring errors within HN cancers.Reference Boero 14 Through the utilization of contour grading, we observe a more consistent production of high-quality plans by the end of the pilot phase.

During the reporting period of the maintenance phase from 2019 to 2023, we observe a stable low R2 rate of less than 3 cases per year for each HN RO AP, which we expect to persist due to the potential for error. The plateauing of R2 revisions is likely driven by improved group consensus and collective adherence to institutional guidelines over time. Ultimately, the drastic juxtaposition of the contour quality from the beginning of the pilot phase to the maintenance phase unravels the impact of a formal HN PR process on the production of high-quality contours and, consequently, RTPs that can set up HN patients for greater clinical success with a lower risk of potential tumour misses or undesired radiation side effects. We continue to employ the PR system with contour grading in our routine HN clinical system today to continue to monitor contour quality. We believe the system continues to ensure the highest quality of contours and RTP for each individual patient. We believe the time spent on peer review is worthwhile, even if we continue to correct few errors over time, since the detriment to those patients would be profound. The PR process at our institution has also been collectively embraced by all RO HN AP since it initiates a collaborative culture that encourages sharing of ideas and continual learning to further evolve contouring skills of each individual physician.

The introduction of an HN contouring PR system at our institution allowed for a more consistent production of high-quality RTPs while improving workplace culture. It is well-established that HN cancers have one of the highest interobserver variabilities per site within RO. Reference Farris2,11–Reference Segedin and Petric13,Reference Gogineni17,Reference Nielsen23,Reference Ballo29 The presentation of contours at a dedicated HN contouring PR directly tackles inter-observer variability through extensive discussions and immediate revision suggestions from HN experts, limiting the potential for detrimental patient outcomes through cultivating higher quality RTPs. The PR process sets up a collaborative and nonjudgemental environment that welcomes comprehensive discussions regarding each patient case. These discussions allow for mutual knowledge sharing and the emergence of more covert viewpoints, increasing collective RO knowledge and fostering a culture of continuous learning. Reference McDowell and Corry9,Reference Martin-Garcia12,Reference Brundage22 This is especially beneficial for resident physicians who can actively participate in the discussions and have greater exposure to HN cancers, a historically diverse subsite with unique patient presentations. Similar to previous studies, this study observes greater group consensus over time with fewer R2s and more R0s suggesting increased adherence to institutional guidelines. Reference Cox6,Reference Martin-Garcia12,Reference Ballo29 This sanctions practice standardization, which both eases institutional comparison and creates a standard for resident physicians to achieve prior to graduation.

We prioritize the completion of PR prior to the creation of RTPs during the pilot and ongoing maintenance phase. The current standard of care with PR in the form of chart rounds following RTP completion can negatively impact patient outcomes through inadvertently discouraging suggestions and reverse planning, placing the patient at greater risk for errors. Reference Hesse1,Reference Cox6,Reference Marks18,Reference Lawrence24,Reference Zairis25 In the traditional system, suggestions require working backwards and modifying appropriate parts of the RTP. This can potentially lead to controversial situations where time efficiency may be competing against the benefits of the modification, and one must be chosen over the other with apparent minor suggestions occasionally bypassed in respect of time. By conducting PR prior to RT planning, we remove the need for this debate and allow for all revisions to be suggested and honoured, maximizing patient outcomes and optimizing time and resources. Additionally, it decreases the potential of physicians yielding to the sunken-cost fallacy and disregarding revisions due to their personal dedication to the RTP creation and sense of being complete with a task. Reference Cox6 We call for a move towards prospective PRs alongside traditional chart rounds to ensure clinical efficacy and optimize clinical success.

The contour grading metric employed in this study assures the RTPs delivered are invariably high-quality and practice standards are continuously met. In the pilot phase, we demonstrate an objective improvement in contour grades for all measured components followed by a stable rate in the maintenance phase. Contour grades are beneficial at the beginning of the PR’s implementation by determining the institution’s baseline contour quality and providing a metric to observe PR’s impact on contour production. Its stability in the maintenance phase may raise questions on its benefits post stabilization. However, contour grades can continue to remain beneficial due to their emphasis on accountability for physicians and ease in determining outliers. Contour grading in the context of a weekly PR sessions pushes radiation oncologists to consistently produce high-quality contours in a timely manner. Reference Cox6 Additionally, contour grades allow for a straightforward determination of occasional R2s and subsequent revision ensuring that all patients are receiving a plan best suited to their needs at that time. Through recording contour grades for each physician, it serves as a simple metric to observe if physicians are meeting practice contouring standards throughout their career. Contour grading is a metric that can be easily implemented into clinical workflow to serve as a QA tool for assessing both treatment plans and physician competency.

There are some limitations to this study. It is well-established that high-quality contours correlate to improved patient outcomes with a lower likelihood of misses or unnecessary inclusion of OARs. Reference McDowell and Corry9,11,Reference Segedin and Petric13,Reference Cooper16,Reference Nuyts26 Taking that notion into consideration, this series reports that the PR system may have a positive impact on patient outcomes due to a more consistent production of high-quality contours. However, the study did not demonstrate a clear indication of the effect of the HN contour PR system on clinical outcomes. Future studies should follow-up on this preposition and juxtapose patient outcomes before and after PR initiation to determine if this correlation remains. Additionally, this institution did not require contours receiving R2s to be presented again at PR sessions, potentially negatively impacting patient outcomes. If feasible, organizations should consider the re-presentation of R2 at weekly PR sessions or through ad hoc sessions prior to RTP initiation by dosimetry. This study did not account for the possibility of the group-think phenomenon over time, potentially acting as a cofounding variable in the decrease of R2 revisions and increase in R0 revisions over time. We utilize small group discussions that emphasize patient safety and diverse opinions from each individual attending to combat the tendency for conformity; however, some degree of groupthink likely prevails and should be considered when implementing PR in the clinical workflow. Although our peer review process did not include a formal anatomist, all reviewers were high-volume HN radiation oncologists at a tertiary academic centre, each with more than five years of independent practice following training. Given their subspecialization and clinical experience, these clinicians function as disease-site experts with deep familiarity in HN anatomy and reference published treatment guidelines such as Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) atlases to provide an objective framework to complement expert judgment. We recognize that this data may not be a typical composition of all RO departments, which may limit the application of this data. Additionally, peer review groups may still be subject to interpersonal dynamics or authority gradients, which can influence consensus. Importantly, the intent of peer review is to ensure technical accuracy and consistency in contouring. It is not a mechanism to address individual professionalism concerns, which are handled through separate institutional processes. Nevertheless, it is important for the group to adhere to an accepted code of conduct. Another potential limitation is that the expert peer reviewers did not generate their own contours for direct comparison to the treating physician’s contours. Dice similarity coefficient is therefore not available to guide contour comparison. Lastly, the concerns of time efficacy often draw organizations away from the routine implementation of PR. Reference McDowell and Corry9 This series did not report the time spent on each case and overall time spent per week on PR. However, the observed substantial impact of the PR process on a crucial step of the RTP, contouring and target delineation, suggests that the trade-off between time and clinical success is worthwhile.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that implementation of a prospective HN contour PR process within routine clinical workflow is feasible and ensures quality contours. Through the utilization of contour grading, we observed an improvement in contour quality over the course of the pilot phase with a decrease in R2 revisions and increase in R0 revisions that was sustained in the maintenance phase. The collective experience of multiple high-volume ROs ensured high-quality contours for RTP, which could positively impact patient outcomes.

Data availability statement

All data created and analyzed in this series are included in this publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors of the paper have no acknowledgments related to the contents of this paper to share.

Financial support

This work did not receive funding from public or private entities.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this publication.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The data was reviewed under IRB ID 18-009627, Clinical Outcomes of Head and Neck Cancer at the Mayo Clinic.

Consent to participate

Due to the noninterventional nature and low risk of this study, the Mayo Clinic IRB did not require individual patient consent.