Highlights

What is already known?

-

• Meta-analysis methods are widely used to combine effect sizes across studies, typically within a traditional frequentist framework.

-

• These methods face challenges in hypothesis testing because the cumulative nature of meta-analyses inherently induces multiple testing issues.

-

• Bayes factors provide an alternative that directly quantify the evidence between hypotheses, and allow for natural evidence accumulation.

What is new?

-

• The article compares Bayes factor testing with classical significance testing in meta-analyses, clarifying their conceptual and methodological differences.

-

• It presents five Bayes factor models for evidence synthesis, illustrated using the standard single-effect-size meta-analysis setup.

-

• The article discusses prior specification, including priors for the (nuisance) between-study heterogeneity.

-

• It highlights the link between Bayes factors and e-values as a means for flexible classical error control in cumulative meta-analyses.

-

• All methods are implemented in the R package BFpack.

Potential impact for RSM readers

-

• The overview aims to guide researchers in selecting suitable evidence synthesis methods and promote flexible, statistically robust Bayesian approaches for hypothesis testing in (cumulative) meta-analyses.

1. Introduction

Meta-analysis refers to the statistical methodology used for combining independent studies addressing the same research question. The approach improves the precision of results, combines the available evidence, and may also resolve controversies when contradicting conclusions are drawn in multiple studies.Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman, McKenzie and Veroniki1 Given the available published studies, a meta-analyst is often interested in estimating the magnitude of a global effect and its statistical uncertainty. Instead of (or next to) estimation, the focus of a meta-analyst can be on testing whether the effect is equal to a specific value, typically zero.Reference Higgins, Thompson and Spiegelhalter2– Reference Rice, Higgins and Lumley4 This is, for instance, of interest if the goal is to answer whether a treatment is beneficial on average.

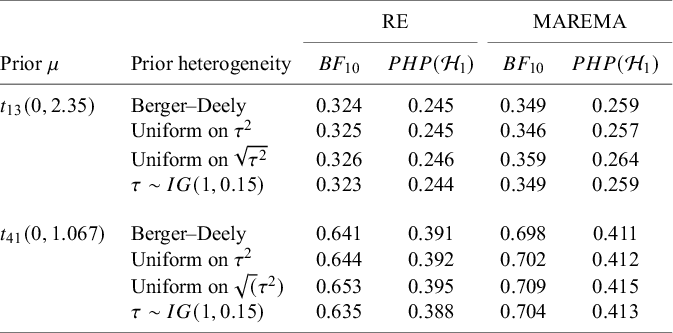

Over the last decades, Bayesian estimation methods have become increasingly popular.Reference Higgins, Thompson and Spiegelhalter2, Reference Smith, Spiegelhalter and Thomas5– Reference Schmid, Carlin, Welton, Schmid, Stijnen and White8 These methods may be more accurate in case of a few studies by not relying on large sample theory and the possibility to include external information in the prior distribution.Reference Friede, Röver, Wandel and Neuenschwander9, Reference Rhodes, Turner, White, Jackson, Spiegelhalter and Higgins10 If the information in the data dominates the prior, classical and Bayesian estimation methods behave similarly. When the goal is to test the effect on a specific value (or specific range), classical significance-based testing is most common using classical two-sided p-values. The test may also be executed by evaluating whether the specific (null) value falls inside the classical confidence interval (CI) or inside the Bayesian credible interval (CrI). Another way to test hypotheses in meta-analyses is using the Bayes factor, a Bayesian criterion for hypothesis testing.Reference Jeffreys11, Reference Kass and Raftery12 Bayes factors possess fundamentally different properties from significance-based tests. This Bayesian criterion may be particularly useful for meta-analyses where statistical evidence accumulates across multiple studies. While meta-analyses are typically modeled as combining independent studies, in practice, earlier findings often influence whether subsequent studies are conducted, meaning that true independence rarely holds.Reference Ter Schure and Grünwald13 This implicit sequential dependence further motivates the use of Bayes factors, which remain valid under such cumulative accumulation of evidence. As the meta-analysis community is less familiar with this alternative methodology, this article aims to provide a critical overview of theoretical properties, methodological considerations, and practical advantages of this methodology. Table 1 summarizes key conceptual and practical differences between classical p-value testing and Bayes factor testing, which we elaborate upon below.

Table 1 Summary of differences between classical p-value and Bayes factor testing.

The goal of classical significance testing using the p-value is to make a dichotomous decision while controlling the type I error rate at a particular prespecified

![]() $\alpha $

-level. This is in contrast with the goal of the Bayes factor, which quantifies the relative evidence in the available published studies between the hypotheses via the ratio of the so-called marginal likelihoods of the available data under the respective hypotheses, i.e.,

$\alpha $

-level. This is in contrast with the goal of the Bayes factor, which quantifies the relative evidence in the available published studies between the hypotheses via the ratio of the so-called marginal likelihoods of the available data under the respective hypotheses, i.e.,

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

and

$\mathcal {H}_1$

and

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

. Mathematically, the Bayes factor is defined by:

$\mathcal {H}_0$

. Mathematically, the Bayes factor is defined by:

where

![]() $y_{1:k}$

denotes the available effect sizes from studies 1 to k. Given the interpretation as a measure of relative evidence, and because a meta-analysis aims to synthesize evidence across studies, the use of Bayes factors for meta-analyses is sometimes termed Bayesian evidence synthesis.Reference Scheibehenne, Jamil and Wagenmakers21–

Reference Klugkist and Volker23

$y_{1:k}$

denotes the available effect sizes from studies 1 to k. Given the interpretation as a measure of relative evidence, and because a meta-analysis aims to synthesize evidence across studies, the use of Bayes factors for meta-analyses is sometimes termed Bayesian evidence synthesis.Reference Scheibehenne, Jamil and Wagenmakers21–

Reference Klugkist and Volker23

As can be seen from (1), the Bayes factor is a type of likelihood ratio. Unlike the classical likelihood ratio test statistic, which is computed at the maximum likelihood estimates of the unknown parameters (Chapter 8),Reference Casella and Berger24 the marginal likelihoods are computed as weighted averages of the likelihood weighted according to the prior distributions of the unknown parameters under the hypotheses.Reference Jeffreys11, Reference Kass and Raftery12 Therefore, the Bayes factor is sensitive to the choice of the prior: its outcome is only meaningful when the chosen priors are meaningful, especially for the parameter that is tested. In Bayesian estimation of meta-analysis models on the other hand, the prior plays a considerably smaller role if “vague,” weakly informative, or noninformative priors are usedFootnote i When testing hypotheses using the Bayes factors, extremely vague priors should not be used for the effect that is tested. Such priors cover unrealistically large effect sizes, often resulting in Bayes factors that are unrealistic quantifications of the relative evidence between the hypotheses.

While this prior sensitivity is sometimes cited as a limitation,Reference Higgins, Thompson and Spiegelhalter2 classical testing approaches also require subjective inputs, such as defining a minimal effect of interest for equivalence testing or choosing a plausible effect size for power analysis.Reference Lakens14, Reference Hoenig and Heisey16 Hence, both statistical approaches demand thoughtful specification of the alternative hypothesis (Table 1).Reference Rouder, Morey, Verhagen, Province and Wagenmakers26 Because of the importance of prior specification, this article elaborately discusses this topic under various meta-analysis models.

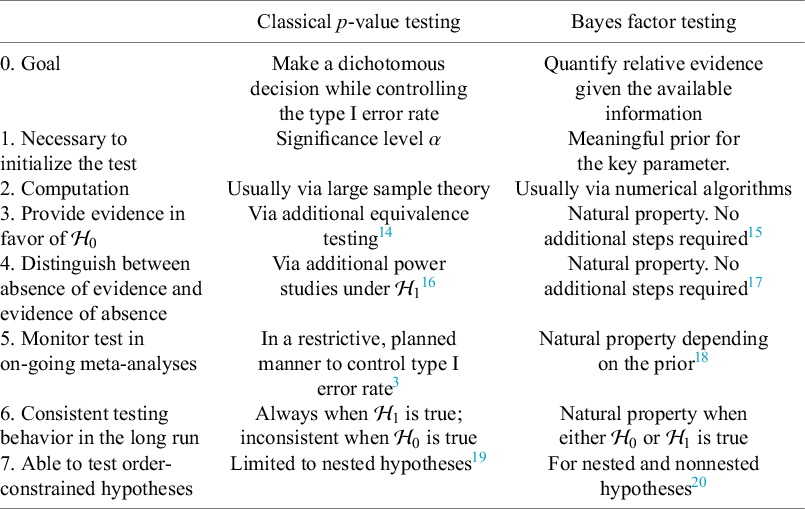

Once priors are specified, computing the Bayes factor usually requires intensive numerical methods, unlike classical p-value tests that rely on simpler large-sample calculations. To interpret a Bayes factor, Figure 1 displays the relative evidence between the hypotheses on a continuous scale. For example, a Bayes factor of

![]() $B_{10}=15$

implies that the data were 15 times more plausible under the alternative

$B_{10}=15$

implies that the data were 15 times more plausible under the alternative

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

than under the null

$\mathcal {H}_1$

than under the null

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

, implying considerable evidence in favor of

$\mathcal {H}_0$

, implying considerable evidence in favor of

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

. On the other hand, a Bayes factor of, say,

$\mathcal {H}_1$

. On the other hand, a Bayes factor of, say,

![]() $B_{10}=0.14$

, implies that we obtained positive evidence in favor of

$B_{10}=0.14$

, implies that we obtained positive evidence in favor of

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

because

$\mathcal {H}_0$

because

![]() $B_{01}=1/B_{10}\approx 7.1$

implying that the data were 7.1 times more plausible under

$B_{01}=1/B_{10}\approx 7.1$

implying that the data were 7.1 times more plausible under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

. This illustrates that Bayes factors allow evidence quantification in favor of a null hypothesis. Depending on the field of research, this natural property may be particularly important because null hypotheses may often be true.Reference Johnson, Payne, Wang, Asher and Mandal27

$\mathcal {H}_0$

. This illustrates that Bayes factors allow evidence quantification in favor of a null hypothesis. Depending on the field of research, this natural property may be particularly important because null hypotheses may often be true.Reference Johnson, Payne, Wang, Asher and Mandal27

Figure 1 Interpreting the evidence on a continuous (log) scale. The qualitative categories can be found in Kass and Raftery.Reference Kass and Raftery12 Visualization of the colored bar from Mulder et al.Reference Mulder, Friel and Leifeld28

Moreover, if the Bayes factor is close to 1, this would imply the absence of evidence toward any of the two hypotheses (Table 1).Reference Dienes17,

Reference Altman and Bland29 This illustrates that Bayes factors have the natural ability to distinguish between absence of evidence (i.e., an underpowered analysis when

![]() $B_{10}\approx 1$

) and evidence of absence (i.e., evidence in favor of the null when

$B_{10}\approx 1$

) and evidence of absence (i.e., evidence in favor of the null when

![]() $B_{01}\gg 1$

). To assess whether the test was underpowered using classical testing, additional power analyses would have been required. However, when power analyses have not been executed before the analysis, post-experimental power analyses are not without problems.Reference Hoenig and Heisey16

$B_{01}\gg 1$

). To assess whether the test was underpowered using classical testing, additional power analyses would have been required. However, when power analyses have not been executed before the analysis, post-experimental power analyses are not without problems.Reference Hoenig and Heisey16

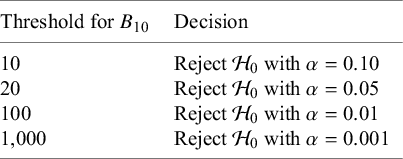

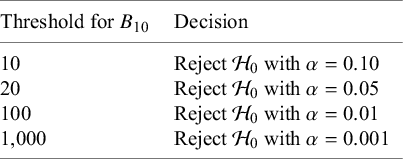

Figure 1 shows qualitative bounds for interpreting Bayes factors, as proposed in the literature,Reference Jeffreys11,

Reference Kass and Raftery12 which serve primarily as a guide for researchers less familiar with the concept and should not be applied rigidly. While Bayes factors naturally provide a graded measure of evidence, they can also be compared against a threshold to make dichotomous decisions, potentially controlling classical type I error rates even in on-going meta-analyses where studies are evaluated sequentially, regardless of the stopping rules or data-collection decisions applied in previous studies.Reference Ter Schure and Grünwald13,

Reference De Heide and Grünwald18,

Reference Grünwald, de Heide and Koolen30,

Reference Rouder31 Classical tests, by contrast, require careful pre-planning for such designs (see Table 1).Reference Higgins, Whitehead and Simmonds3 This type I error control for Bayes factors in sequential settings is enabled by recent advances in “e-value theory,” which supports “safe anytime-valid inference”—a relatively novel statistical framework ensuring that statistical conclusions remain valid regardless of when data collection or analysis stops, without requiring careful pre-planning.Reference Grünwald, de Heide and Koolen30,

Reference Ramdas and Wang32,

Reference Ly, Boehm, Grünwald, Ramdas and Ravenzwaaij33 Moreover, Bayes factors are statistically consistent, with evidence accumulation toward the true hypothesis as the number of studies grows, whereas classical tests remain inconsistent due to a persistent chance of rejecting a true null at the pre-specified

![]() $\alpha $

-level.

$\alpha $

-level.

Finally, Bayes factors are relatively flexible for testing more complex hypotheses involving combinations of equality and order constraints on multiple parameters. Such hypotheses can reflect more precise scientific expectations regarding the specific relationships between the parameters (such as order constraints between group means). Though not very common, they have been used for meta-analytic applications.Reference Kuiper, Buskens, Raub and Hoijtink34, Reference Wonderen, Zondervan-Zwijnenburg and Klugkist35 Although p-values are also available for testing such hypotheses, the class of order-constrained hypotheses that can be tested is limited (e.g., only nested hypotheses can be tested against each otherReference Silvapulle and Sen19).

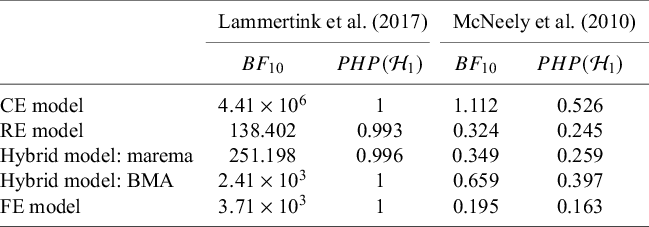

To guide researchers interested in using Bayes factors for hypothesis testing in meta-analyses, we begin with a published example that motivates our work (Section 2). Section 3 introduces five meta-analytic models, focusing on the standard framework of normally distributed effect sizes with known error variances and independent contributions per study. This standard setup was chosen for accessibility and because normal models are most often used. Naturally, it is generally advisable to use exact models when appropriate (e.g., a logistic model for binary data). Throughout the article, we focus on the (most common) two-sided hypothesis test. Section 4 discusses prior specification for the (average) effect size, which may reflect the standardized mean difference, log odds ratio, or Fisher-transformed correlation, with brief remarks on priors for between-study heterogeneity. Section 5 outlines how to compute Bayes factors for the five models. Section 6 connects Bayes factors to e-values, highlighting their suitability for sequential meta-analysis. Section 7 provides a synthetic illustration, and Section 8 applies Bayes factors to two real meta-analyses. We conclude with a discussion, and note that the R package BFpack Reference Mulder, Williams and Gu36 has been extended to support several of the Bayes factor tests presented here.

2. Motivating illustration

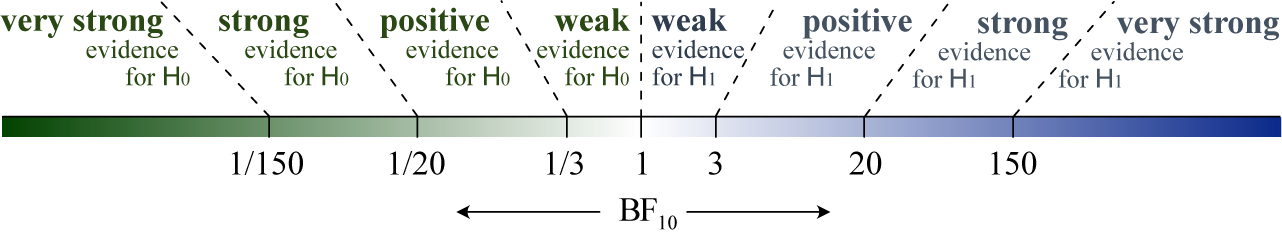

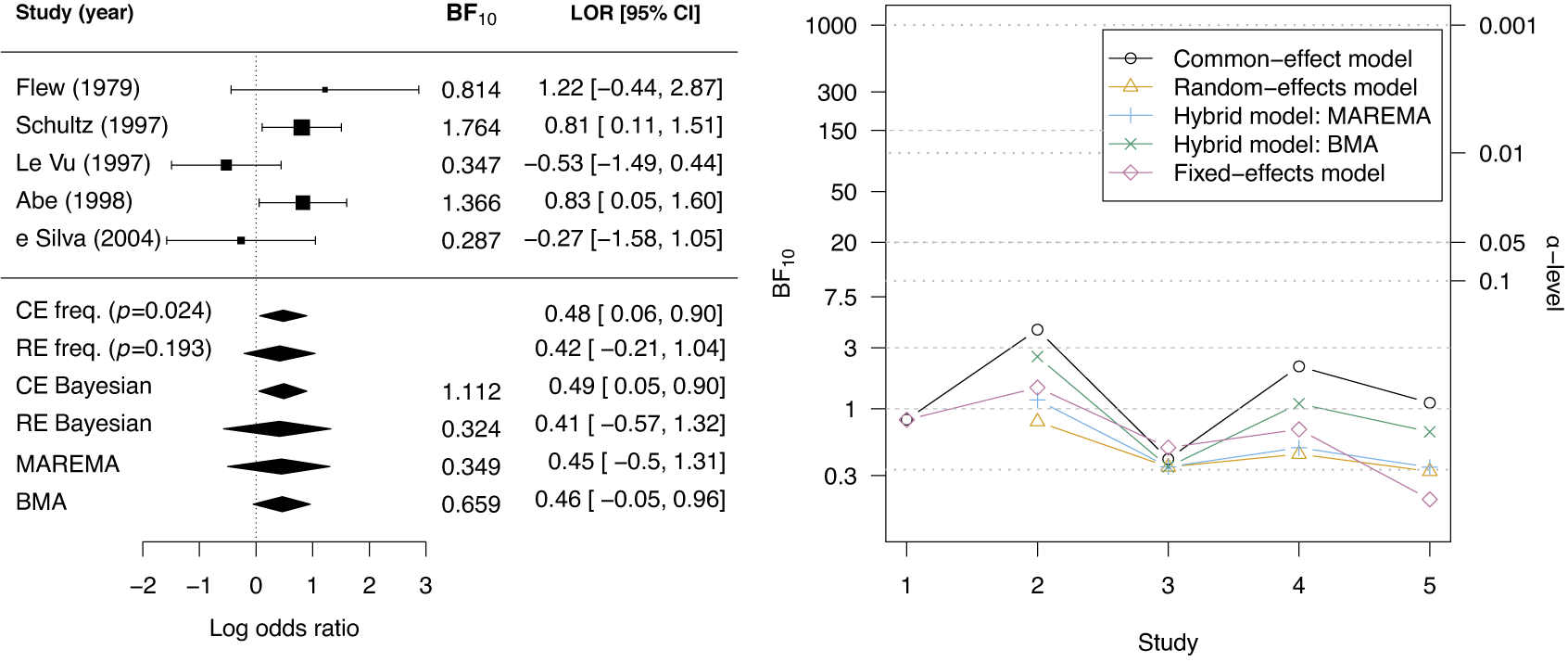

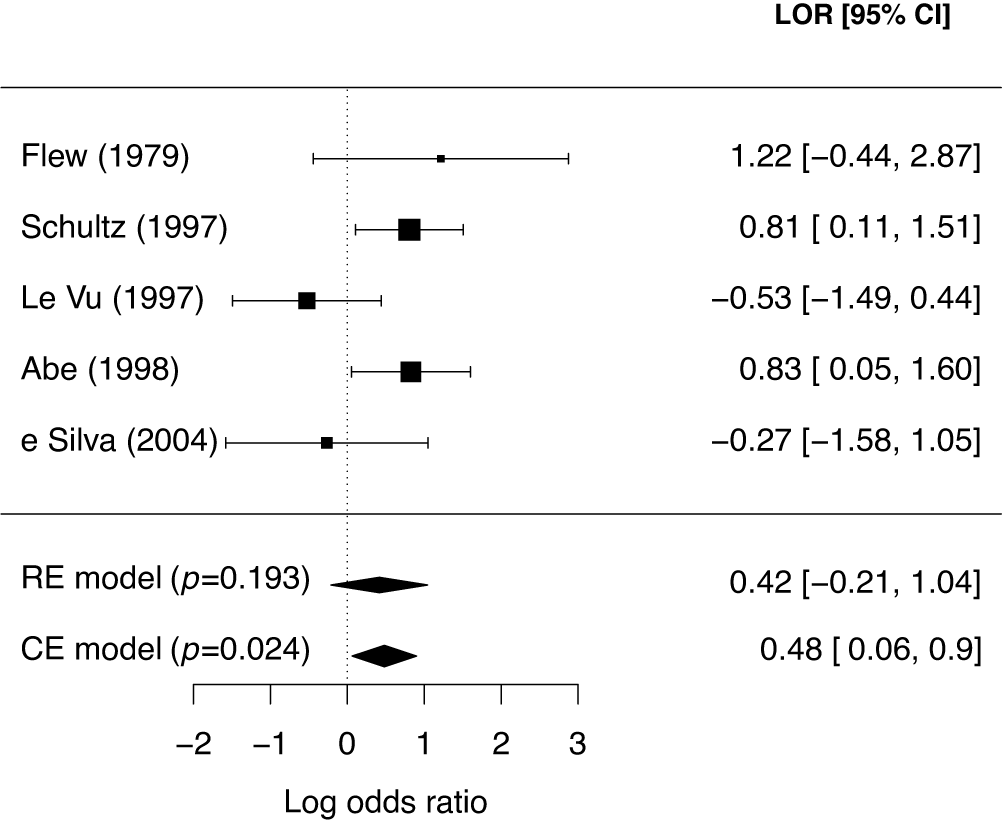

McNeely et al.Reference McNeely, Campbell and Ospina37 presented a meta-analysis on the incidence of seroma when patients start exercising within or after three days following a breast cancer surgery. Five studies are included in this meta-analysis where patients were assigned to an early or delayed exercise condition in each study. The outcome variable was the occurrence of seroma. Thus, a log odds ratio was the effect size measure of interest. A log odds ratio larger (smaller) than zero indicates that seroma is more (less) likely to appear in this early period compared to the delayed exercise condition. The data (including the publication years of the studies in chronological order) and the corresponding 95%-CIs for this meta-analysis are presented in the forest plot in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Forest plot for the meta-analysis of McNeely et al. (2010). LOR is the log odds ratio, and RE and CE refer to the random effects and the common effect, respectively.

We can formulate the following two-sided test for this application:

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{H}_0 &: \text{"The average effect is zero."}\\ \mathcal{H}_1 &: \text{"The average effect is nonzero (either positive or negative)."} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{H}_0 &: \text{"The average effect is zero."}\\ \mathcal{H}_1 &: \text{"The average effect is nonzero (either positive or negative)."} \end{align*} $$

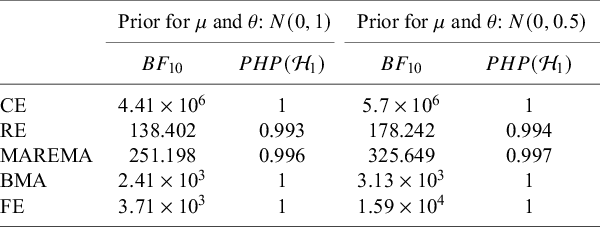

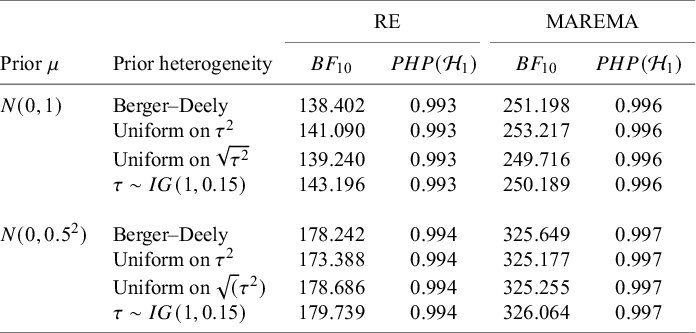

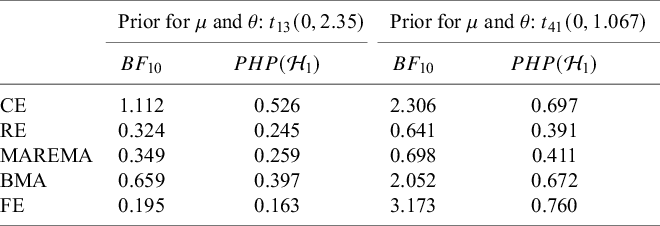

If the conventional significance level of 5% were applied, the null hypothesis would have been rejected under the common effect (CE) model but not under the random effects (RE) model. The null hypothesis of no between-study heterogeneity was not rejected based on the Q-test (

![]() $Q(4) = 7.765$

,

$Q(4) = 7.765$

,

![]() $p = 0.101$

). However, this test is known to have low power when only a few studies are available.Reference Hardy and Thompson38 Given the considerable heterogeneity among the effects observed in the individual studies, a more conservative approach—such as the RE model used byReference McNeely, Campbell and Ospina37—is likely more appropriate. Under this model, there is insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis regarding the average effect. However, the outcome of this classical test does not clarify whether the nonsignificant result reflects a true null effect or simply a lack of statistical power—especially sinceReference McNeely, Campbell and Ospina37 did not report a power analysis.

$p = 0.101$

). However, this test is known to have low power when only a few studies are available.Reference Hardy and Thompson38 Given the considerable heterogeneity among the effects observed in the individual studies, a more conservative approach—such as the RE model used byReference McNeely, Campbell and Ospina37—is likely more appropriate. Under this model, there is insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis regarding the average effect. However, the outcome of this classical test does not clarify whether the nonsignificant result reflects a true null effect or simply a lack of statistical power—especially sinceReference McNeely, Campbell and Ospina37 did not report a power analysis.

Due to this statistical uncertainty, a research group may be motivated to conduct a new study on the incidence of seroma. Once published, however, updating the meta-analysis using classical significance testing introduces a challenge: what significance level (

![]() $\alpha $

) should be used when testing the null hypothesis a second time? Re-testing naturally inflates the overall significance level. Ignoring this multiple testing problem undermines the core assumption of a fixed sample size that underlies classical p-value-based inference.

$\alpha $

) should be used when testing the null hypothesis a second time? Re-testing naturally inflates the overall significance level. Ignoring this multiple testing problem undermines the core assumption of a fixed sample size that underlies classical p-value-based inference.

Bayes factors offer a compelling alternative in such settings. First, they can distinguish between a lack of evidence (i.e., an underpowered study, leading to a Bayes factor close to 1) and evidence favoring the null hypothesis (i.e., a Bayes factor indicating substantial support for the null; Figure 1). Second, Bayes factors allow for straightforward updating of the relative evidence for competing hypotheses as new studies become available. Furthermore, recent advances in e-value theoryReference De Heide and Grünwald18, Reference Ramdas and Wang32, Reference Grünwald, Heide and Koolen39, Reference Hendriksen, Heide and Grünwald40 make it possible to maintain Type I error control without relying on subjective priors, thus preserving desirable frequentist properties while still benefiting from Bayesian updating.

Finally, note that a meta-analyst may consider reporting the Bayesian probability that the average effect is positive, particularly if this direction is expected. Such probabilities behave similarly to one-sided p-values however,Reference Marsman and Wagenmakers41 and thus face similar challenges as two-sided p-values in the context of hypothesis testing.

3. Statistical models for Bayesian evidence synthesis

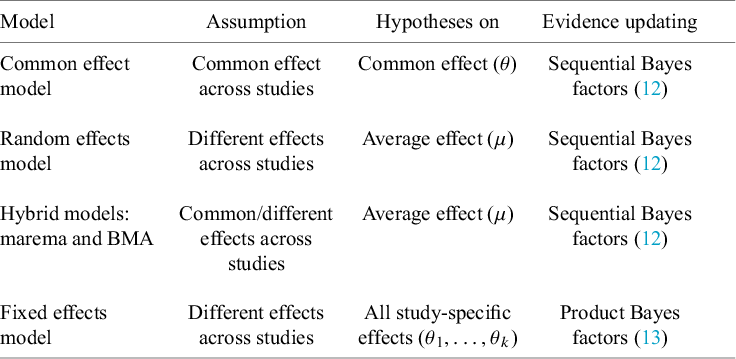

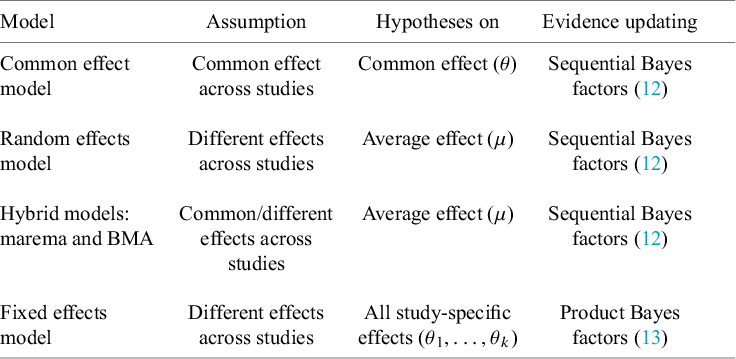

Depending on the application, different meta-analysis models can be used. The current section gives a brief overview of three traditional and two more recent hybrid meta-analysis models. Bayes factor tests will be discussed under these models in subsequent sections.

3.1. Traditional meta-analysis models

3.1.1. Common effect model

Under the CE model, the key parameter, denoted by

![]() $\theta $

, is assumed to be common under all studies. In order for this assumption to hold, the conditions under which the data are collected under every study need to be (practically) identical, such as replication studies in psychologyReference Schmidt42 or series of randomized clinical trials by the same researchers, for patients from the same population, and testing exactly the same treatment.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein43

$\theta $

, is assumed to be common under all studies. In order for this assumption to hold, the conditions under which the data are collected under every study need to be (practically) identical, such as replication studies in psychologyReference Schmidt42 or series of randomized clinical trials by the same researchers, for patients from the same population, and testing exactly the same treatment.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein43

For study i, for

![]() $i=1,\ldots ,k$

, we denote the estimated effect size by

$i=1,\ldots ,k$

, we denote the estimated effect size by

![]() $y_i$

, its (assumed known) standard error by

$y_i$

, its (assumed known) standard error by

![]() $\sigma _i$

, and the sample size in the study by

$\sigma _i$

, and the sample size in the study by

![]() $n_i$

. A Gaussian (normal) error is assumed for the study-specific estimate and the corresponding standard error resulting in the following synthesis model:

$n_i$

. A Gaussian (normal) error is assumed for the study-specific estimate and the corresponding standard error resulting in the following synthesis model:

Under the CE model, we consider the most common test in statistical practice of a precise null hypothesis, which assumes that the mean effect is zero, against a two-sided null hypothesis test, which assumes that the mean effect is nonzero, i.e.,

3.1.2. Random effects model

Under the RE model, the effects

![]() $\theta _i$

are assumed to be heterogeneous across studies. This heterogeneity may be caused by (slightly) different conditions under which the data were collected across studies or (slightly) different populations that were considered under the different studies. The RE model is generally the preferred model since researchers deem the assumption of a CE unrealistically restrictive in most applications. Moreover, the RE model is also often preferred, because it allows for drawing inference for the distribution of true effects whereas the CE model is restricted to drawing inference to only the included studies in a meta-analysis.

$\theta _i$

are assumed to be heterogeneous across studies. This heterogeneity may be caused by (slightly) different conditions under which the data were collected across studies or (slightly) different populations that were considered under the different studies. The RE model is generally the preferred model since researchers deem the assumption of a CE unrealistically restrictive in most applications. Moreover, the RE model is also often preferred, because it allows for drawing inference for the distribution of true effects whereas the CE model is restricted to drawing inference to only the included studies in a meta-analysis.

A normal distribution is assumed for the study-specific effects, where the mean

![]() $\mu $

quantifies the average (global) effect across studies and the standard deviation

$\mu $

quantifies the average (global) effect across studies and the standard deviation

![]() $\tau $

quantifies the between-study heterogeneity in true effect size. Similar to the CE model, normally distributed errors are assumed for the study-specific estimates. The RE model can then be formulated as

$\tau $

quantifies the between-study heterogeneity in true effect size. Similar to the CE model, normally distributed errors are assumed for the study-specific estimates. The RE model can then be formulated as

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{M}_{RE}:\left\{\begin{array}{ccl} y_i &\sim & N(\theta_i,\sigma_i^2)\\ \theta_i &\sim & N(\mu,\tau^2). \end{array} \right. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{M}_{RE}:\left\{\begin{array}{ccl} y_i &\sim & N(\theta_i,\sigma_i^2)\\ \theta_i &\sim & N(\mu,\tau^2). \end{array} \right. \end{align} $$

In this model, the study-specific true effects (i.e.,

![]() $\theta _i$

) are often treated as nuisance parameters which can be integrated out. The marginalized RE model can then be equivalently written as

$\theta _i$

) are often treated as nuisance parameters which can be integrated out. The marginalized RE model can then be equivalently written as

Under the RE model, we generally test whether the global effect

![]() $\mu $

is zero or not, i.e.,

$\mu $

is zero or not, i.e.,

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{H}_0&:\mu = 0\\ \nonumber \mathcal{H}_1&:\mu \not = 0. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{H}_0&:\mu = 0\\ \nonumber \mathcal{H}_1&:\mu \not = 0. \end{align} $$

3.1.3. Fixed effects models

Similarly to the RE model, and unlike the CE model, the fixed effects (FE) model also assumes heterogeneous effects across studies. However, rather than specifying a distribution for the between-study heterogeneity, whose parameters are estimated from the data, an FE approach is considered without a multilevel structure. The parameters of interest are the true effect sizes of the studies. Although less common, the FE model has been used in meta-analytic applicationsReference Rice, Higgins and Lumley4, Reference Klugkist and Volker23, Reference Kuiper, Buskens, Raub and Hoijtink34, Reference Wonderen, Zondervan-Zwijnenburg and Klugkist35, Reference Van Lissa, Clapper and Kuiper44 and when aggregating evidence across respondents.Reference Stephan, Weiskopf, Drysdale, Robinson and Friston45– Reference Klaassen, Zedelius, Veling, Aarts and Hoijtink47, Footnote ii Moreover, the FE model can also be seen as a CE model that is extended to a meta-regression model by the inclusion of a moderator that has a unique value for each study. According to this meta-regression model, each study also has its own true effect size.

Again, Gaussian errors are assumed for the study-specific effect size estimates. The FE model can then be formulated as

Because of the absence of a parameter for a global effect, the null hypothesis assumes that all study-specific effects are zero or not,Reference Rice, Higgins and Lumley4 i.e.,

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{H}_0&:\theta_1=\dots=\theta_k=0,\\ \mathcal{H}_1&:\text{not } \mathcal{H}_0, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{H}_0&:\theta_1=\dots=\theta_k=0,\\ \mathcal{H}_1&:\text{not } \mathcal{H}_0, \end{align*} $$

where the alternative assumes that at least one constraint under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

does not hold. Hence, this null hypothesis fundamentally differs from the null hypothesis under the CE and RE models where the average effect across studies is assumed to be zero, while in the FE model, the null assumes that all study-specific effects are assumed to be zero. Consequently, the null is extended with every newly included study.

$\mathcal {H}_0$

does not hold. Hence, this null hypothesis fundamentally differs from the null hypothesis under the CE and RE models where the average effect across studies is assumed to be zero, while in the FE model, the null assumes that all study-specific effects are assumed to be zero. Consequently, the null is extended with every newly included study.

It has been argued that an FE model has the advantage that it can be used when the study designs and/or measurement levels of the key variables (highly) vary across studies.Reference Klugkist and Volker23, Reference Kuiper, Buskens, Raub and Hoijtink34 The argument is that we are not combining effect sizes, which may then have (highly) different scales, but rather combining statistical evidence regarding the hypotheses when computing Bayes factors. However, the relative evidence between hypotheses as quantified by the Bayes factor is directly affected by the observed effect size and its uncertainty (via the likelihood). Therefore, the appropriateness of combining evidence from different studies with highly different designs, e.g., studies with reported effect sizes based on both dichotomous and continuous outcomes, or studies with an experimental design or observational design, should be carefully assessed by substantive experts. Moreover, prior specification may be more challenging when considering effect sizes having fundamentally different scales.

3.2. Hybrid effects model

To apply a traditional meta-analysis model, a dichotomous decision needs to be made whether to assume between-study homogeneity (i.e., the CE model) or between-study heterogeneity (i.e., the RE model, which is much more common than the FE model). This comes down to the following model selection problem:

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{M}_{CE}&:\tau^2 = 0\\ \nonumber \mathcal{M}_{RE}&:\tau^2> 0. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{M}_{CE}&:\tau^2 = 0\\ \nonumber \mathcal{M}_{RE}&:\tau^2> 0. \end{align} $$

Although the Q-testReference Cochran48 can be used for testing whether the data are homogeneous, it is not recommended for model selection since it may have low statistical power depending on the number of studies included in the meta-analysis, the sample size of the studies, and the true between-study heterogeneity.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein43, Reference Viechtbauer49 This implies potentially large error rates when choosing either one of the two possible models.

Specifically, when an incorrect CE model is employed, the standard error of the key parameter will be underestimated. In a classical significance test, this would result in inflated type I error rates, and in a Bayesian evidence synthesis, this would result in an overestimation of the evidence for the true hypothesis. On the other hand, when an incorrect RE model is employed, the standard error of the key parameter will be overestimated unless

![]() $\tau ^2$

is estimated as zero. In a classical significance test, this results in an underpowered test, and in Bayesian evidence synthesis, this would result in an underestimation of the evidence for the true hypothesis. Thus, when there is considerable statistical uncertainty regarding the true underlying model and there are no theoretical reasons for favoring one model over the others, it is useful to employ a statistical model that encompasses both the CE and RE models to avoid a potentially error-prone dichotomous decision resulting in unreliable quantifications of the statistical evidence.Reference Gronau, Heck, Berkhout, Haaf and Wagenmakers50,

Reference Aert and Mulder51 We shall refer to the class of models that encompasses both the CE model and the RE model as hybrid effects models. To our knowledge, two hybrid effects models have been proposed in the literature, which we discuss below. Appendix A discusses some statistical differences.

$\tau ^2$

is estimated as zero. In a classical significance test, this results in an underpowered test, and in Bayesian evidence synthesis, this would result in an underestimation of the evidence for the true hypothesis. Thus, when there is considerable statistical uncertainty regarding the true underlying model and there are no theoretical reasons for favoring one model over the others, it is useful to employ a statistical model that encompasses both the CE and RE models to avoid a potentially error-prone dichotomous decision resulting in unreliable quantifications of the statistical evidence.Reference Gronau, Heck, Berkhout, Haaf and Wagenmakers50,

Reference Aert and Mulder51 We shall refer to the class of models that encompasses both the CE model and the RE model as hybrid effects models. To our knowledge, two hybrid effects models have been proposed in the literature, which we discuss below. Appendix A discusses some statistical differences.

3.2.1. Marginalized random-effects meta-analysis (marema) model

The marginalized random-effects meta-analysis (marema) modelReference Aert and Mulder51 is closely related to the RE model with the exception that it also allows for the possibility of excessive between-study homogeneity implying less variability across studies than would be expected by chance. The marema model can be written as

where the lower bound of

![]() $\tau ^2$

depends on the smallest sampling variance of the included studies,

$\tau ^2$

depends on the smallest sampling variance of the included studies,

![]() $\sigma _{\min }^2=\min _i \{\sigma ^2_i\}$

. Thus, under the marema model,

$\sigma _{\min }^2=\min _i \{\sigma ^2_i\}$

. Thus, under the marema model,

![]() $\tau ^2$

can attain negative values. A negative

$\tau ^2$

can attain negative values. A negative

![]() $\tau ^2$

implies that the between-study heterogeneity is smaller than expected by chance.

$\tau ^2$

implies that the between-study heterogeneity is smaller than expected by chance.

Although this property may seem unnatural at first sight, this setup has various advantages.Reference Nielsen, Smink and Fox52,

Reference Mulder and Fox53 First, the model allows a simple check of whether between-study heterogeneity is present via the posterior probability that

![]() $\tau ^2>0$

holds (this simple Bayesian measure can also be used as an alternative to the Q-test as it does not rely on large sample theory). Second, the model allows noninformative improper priors for

$\tau ^2>0$

holds (this simple Bayesian measure can also be used as an alternative to the Q-test as it does not rely on large sample theory). Second, the model allows noninformative improper priors for

![]() $\tau ^2$

(both for estimation, e.g., whether

$\tau ^2$

(both for estimation, e.g., whether

![]() $\tau ^2>0$

, and for testing the global mean

$\tau ^2>0$

, and for testing the global mean

![]() $\mu $

using a Bayes factor; see Section 4). Thereby, the model simplifies the (challenging) choice of the prior for

$\mu $

using a Bayes factor; see Section 4). Thereby, the model simplifies the (challenging) choice of the prior for

![]() $\tau ^2$

. Third, the model enables researchers to check for extreme between-study homogeneity (less than expected by chance), which may indicate strong correlation between studies, extreme bias, or potential fraud.Reference Ioannidis, Trikalinos and Zintzaras54 This can be checked via the posterior probability that

$\tau ^2$

. Third, the model enables researchers to check for extreme between-study homogeneity (less than expected by chance), which may indicate strong correlation between studies, extreme bias, or potential fraud.Reference Ioannidis, Trikalinos and Zintzaras54 This can be checked via the posterior probability that

![]() $\tau ^2<0$

. Fourth, as mentioned earlier, the models avoid the need to make a dichotomous decision between the CE model and the RE model but instead naturally balance between these models depending on the between-study heterogeneity that is present. Finally, note that negative variances are very common in latent variable models (such as the RE model). In the factor analysis literature, these are known as “Heywood cases,” which often indicate model misspecification.Reference Kolenikov and Bollen55 In our current setup, this implies that the RE model would be inappropriate given the available data. Marginalized RE models have also been advocated for various other statistical problems.Reference Mulder and Fox56–

Reference Nielsen, Smink and Fox52

$\tau ^2<0$

. Fourth, as mentioned earlier, the models avoid the need to make a dichotomous decision between the CE model and the RE model but instead naturally balance between these models depending on the between-study heterogeneity that is present. Finally, note that negative variances are very common in latent variable models (such as the RE model). In the factor analysis literature, these are known as “Heywood cases,” which often indicate model misspecification.Reference Kolenikov and Bollen55 In our current setup, this implies that the RE model would be inappropriate given the available data. Marginalized RE models have also been advocated for various other statistical problems.Reference Mulder and Fox56–

Reference Nielsen, Smink and Fox52

Under the marema model, the hypothesis test on the global effect will be the same as under the RE model, i.e.,

$$ \begin{align*} & \mathcal{H}_0:\mu = 0,\\ & \mathcal{H}_1:\mu \not= 0. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} & \mathcal{H}_0:\mu = 0,\\ & \mathcal{H}_1:\mu \not= 0. \end{align*} $$

3.2.2. Bayesian model-averaged meta-analysis model

The second hybrid model incorporates the statistical uncertainty regarding the true meta-analysis model via a weighted average of all models under consideration using Bayesian model averaging (BMA), a common approach in Bayesian statistics.Reference Hoeting, Madigan, Raftery and Volinsky58 A Bayesian model-averaged meta-analysis modelReference Gronau, Heck, Berkhout, Haaf and Wagenmakers50 can be obtained by averaging over the CE model and the RE model according to

using prespecified prior probabilities for the CE model and RE model, i.e.,

![]() $\text {Pr}(\mathcal {M}_{CE})=p_{CE}$

and

$\text {Pr}(\mathcal {M}_{CE})=p_{CE}$

and

![]() $\text {Pr}(\mathcal {M}_{RE})=1-p_{CE}$

. Moreover, each of the two model parts,

$\text {Pr}(\mathcal {M}_{RE})=1-p_{CE}$

. Moreover, each of the two model parts,

![]() $\mathcal {M}_{CE}$

and

$\mathcal {M}_{CE}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {M}_{RE}$

, need to be split regarding the absence and presence of the respective key parameters, i.e.,

$\mathcal {M}_{RE}$

, need to be split regarding the absence and presence of the respective key parameters, i.e.,

![]() $\theta $

and

$\theta $

and

![]() $\mu $

, resulting in four model parts:

$\mu $

, resulting in four model parts:

![]() $\mathcal {M}_{CE} \, \&\, \theta = 0$

,

$\mathcal {M}_{CE} \, \&\, \theta = 0$

,

![]() $\mathcal {M}_{CE} \, \&\, \theta \not = 0$

,

$\mathcal {M}_{CE} \, \&\, \theta \not = 0$

,

![]() $\mathcal {M}_{RE} \, \&\, \mu = 0$

, and

$\mathcal {M}_{RE} \, \&\, \mu = 0$

, and

![]() $\mathcal {M}_{RE} \, \&\, \mu \not = 0$

. Typically, equal prior probabilities of

$\mathcal {M}_{RE} \, \&\, \mu \not = 0$

. Typically, equal prior probabilities of

![]() $\frac {1}{4}$

are chosen for these four models.Reference Gronau, Heck, Berkhout, Haaf and Wagenmakers50 Under the BMA approach, the hypothesis test of interest would be formulated as

$\frac {1}{4}$

are chosen for these four models.Reference Gronau, Heck, Berkhout, Haaf and Wagenmakers50 Under the BMA approach, the hypothesis test of interest would be formulated as

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{H}_0&:(\mathcal{M}_{CE}\, \&\, \theta = 0) \text{ or } (\mathcal{M}_{RE}\, \&\, \mu = 0)\\ \mathcal{H}_1&:(\mathcal{M}_{CE}\, \&\, \theta \not= 0) \text{ or } (\mathcal{M}_{RE}\, \&\, \mu \not= 0). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{H}_0&:(\mathcal{M}_{CE}\, \&\, \theta = 0) \text{ or } (\mathcal{M}_{RE}\, \&\, \mu = 0)\\ \mathcal{H}_1&:(\mathcal{M}_{CE}\, \&\, \theta \not= 0) \text{ or } (\mathcal{M}_{RE}\, \&\, \mu \not= 0). \end{align*} $$

The BMA approach has also been extended to include (sub)models that correct for publication bias.Reference Maier, Bartoš and Wagenmakers59

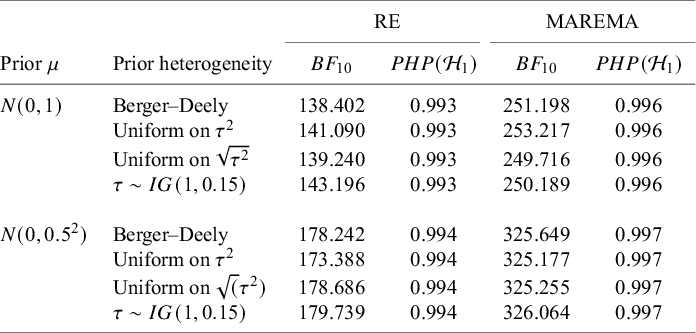

4. Prior specification for the parameters

Prior distributions (or priors for short) need to be chosen for the parameters under the employed meta-analysis model. Priors reflect the plausibility of the parameter values before observing the data. To test the average effect, proper priors need to be formulated for the average effect under all five models. Additionally, under the RE model, the marema model, and the BMA model, a prior needs to be formulated for the between-study heterogeneity, which is a common nuisance parameter under both

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

and

$\mathcal {H}_0$

and

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

. Under the RE model and marema model, a noninformative improper prior can be used. Under the BMA model, the prior for the nuisance parameter must be proper (see also Appendix A).

$\mathcal {H}_1$

. Under the RE model and marema model, a noninformative improper prior can be used. Under the BMA model, the prior for the nuisance parameter must be proper (see also Appendix A).

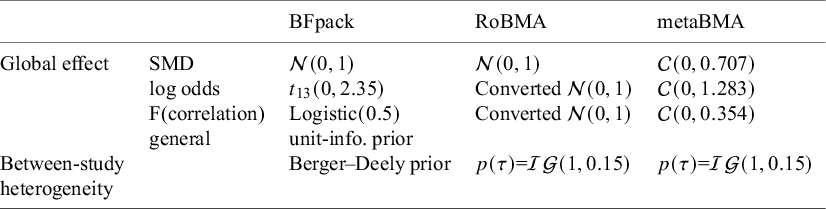

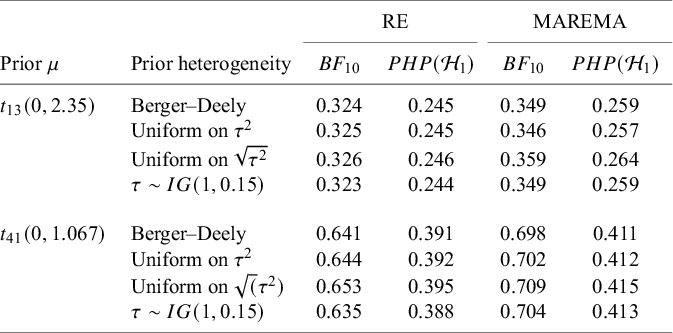

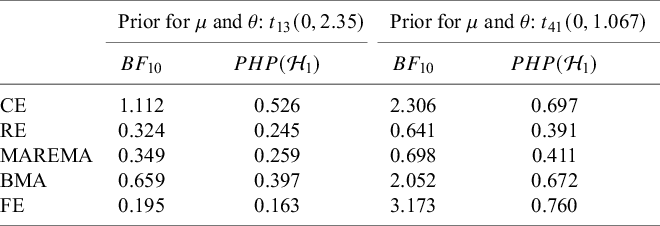

First, we illustrate the sensitivity of Bayes factors to the prior of the tested parameter. Next, we discuss prior specification separately for the average effect and for the between-study heterogeneity parameter. Table 2 gives an overview of default priors which are currently available in existing R packages: BFpack,Reference Mulder, Williams and Gu36 RoBMA,Reference Bartoš and Maier60 and metaBMA.Reference Heck, Gronau and Wagenmakers61 Because the R package bayesmetaReference Röver62 does not provide default priors for Bayes factor testing, this package is omitted in the table.

Table 2 An overview of available default priors when testing the mean effect using existing R packages: BFpack,Reference Mulder, Williams and Gu36 RoBMA,Reference Bartoš and Maier60 and metaBMA.Reference Heck, Gronau and Wagenmakers61

Note: SMD = standardized mean difference;

![]() $t_{13}(0,2.35)$

= t-distribution with a mean of 0, a scale of 2.35, and 13 degrees of freedom;

$t_{13}(0,2.35)$

= t-distribution with a mean of 0, a scale of 2.35, and 13 degrees of freedom;

![]() $\mathcal {C}$

= Cauchy distribution; unit-info. = unit-information;

$\mathcal {C}$

= Cauchy distribution; unit-info. = unit-information;

![]() $\mathcal {IG}$

= inverse-gamma distribution. The Berger–Deely prior is a noninformative improper prior.Reference Röver62,

Reference Berger and Deely63

$\mathcal {IG}$

= inverse-gamma distribution. The Berger–Deely prior is a noninformative improper prior.Reference Röver62,

Reference Berger and Deely63

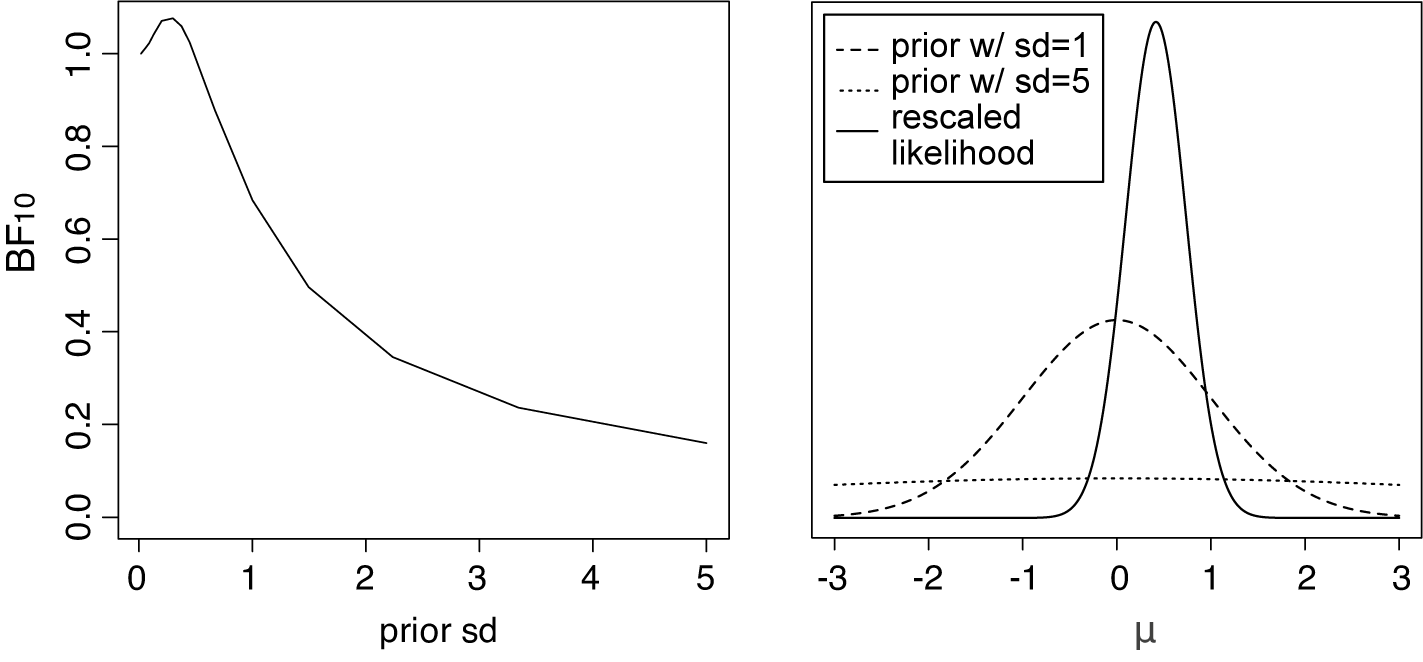

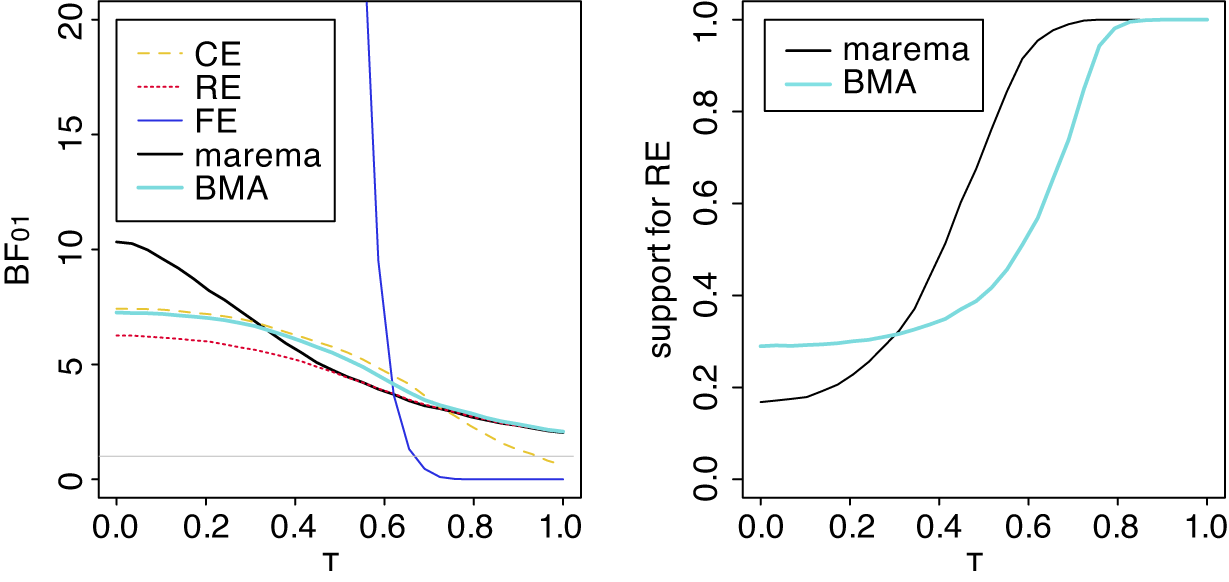

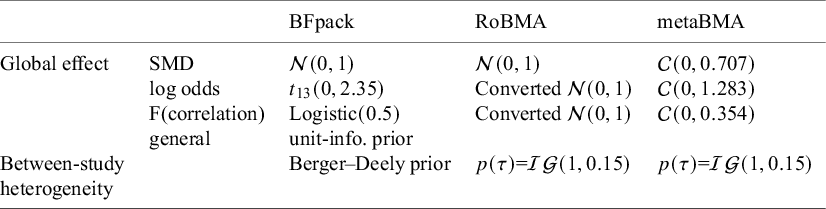

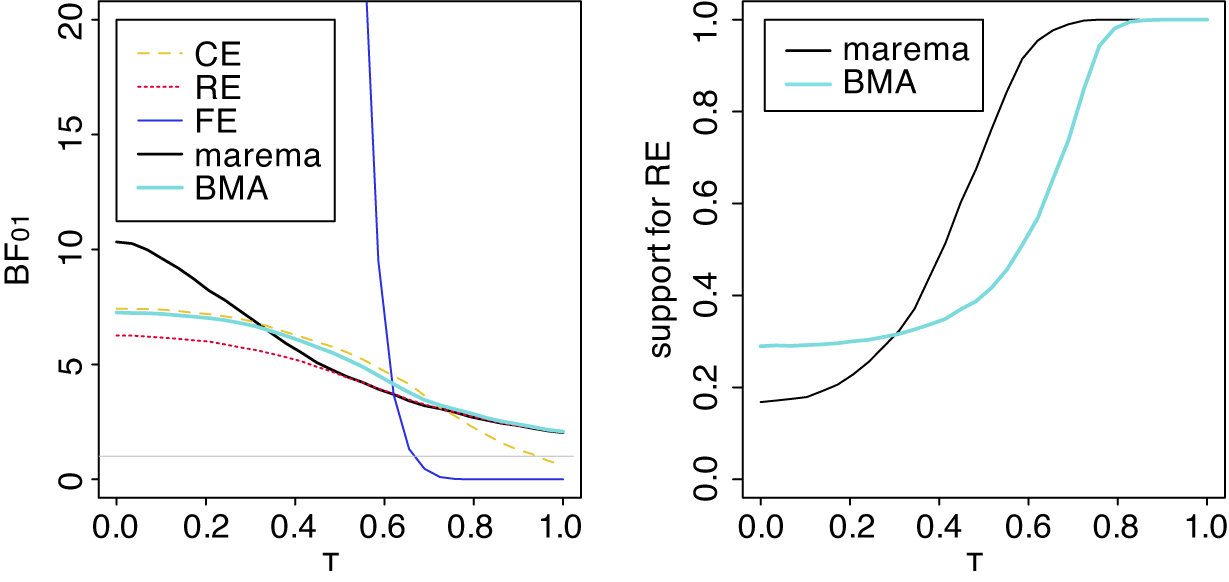

Figure 3 Left panel: The Bayes factor

![]() $B_{10}$

as a function of the standard deviation of a normal prior for the average effect having a mean of zero for the meta-analysis of McNeely et al.Reference McNeely, Campbell and Ospina37 Right panel: Normal priors with mean 0 and a standard deviation of 1 (dashed line) or 5 (dotted line), and the rescaled likelihood evaluated at

$B_{10}$

as a function of the standard deviation of a normal prior for the average effect having a mean of zero for the meta-analysis of McNeely et al.Reference McNeely, Campbell and Ospina37 Right panel: Normal priors with mean 0 and a standard deviation of 1 (dashed line) or 5 (dotted line), and the rescaled likelihood evaluated at

![]() $\hat {\tau }=0.243$

. The likelihood has its mode at

$\hat {\tau }=0.243$

. The likelihood has its mode at

![]() $\hat {\mu }=0.416$

.

$\hat {\mu }=0.416$

.

4.1. Prior sensitivity

The choice of the prior for the average effect, which is unique under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

(as it is fixed under

$\mathcal {H}_1$

(as it is fixed under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

), is particularly important. The sensitivity of the Bayes factor to this prior can be understood from the definition of the Bayes factor in (1). Under

$\mathcal {H}_0$

), is particularly important. The sensitivity of the Bayes factor to this prior can be understood from the definition of the Bayes factor in (1). Under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

, the average effect is assumed to be fixed at zero, and thus, the marginal probability of the data in the available studies quantifies how likely the data were to be observed under the assumption that the effect is zero. Under

$\mathcal {H}_0$

, the average effect is assumed to be fixed at zero, and thus, the marginal probability of the data in the available studies quantifies how likely the data were to be observed under the assumption that the effect is zero. Under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

, the effect is assumed to be unknown and our belief about its magnitude is reflected in the prior distribution. Thus, the marginal probability of the data is equal to a weighted average of the likelihood of the data weighted according to the specified prior.

$\mathcal {H}_1$

, the effect is assumed to be unknown and our belief about its magnitude is reflected in the prior distribution. Thus, the marginal probability of the data is equal to a weighted average of the likelihood of the data weighted according to the specified prior.

In order for the marginal probability under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

to be meaningful, and to ensure that the resulting Bayes factor is meaningful, the prior should correspond to realistic “weights” on the possible (nonzero) effect sizes. For this reason, an extremely vague prior for the average effect should not be used, such as a normal prior with a very large standard deviation. Such a prior would place a relatively large weights at unrealistically large effect sizes, resulting in extremely small marginal likelihoods under

$\mathcal {H}_1$

to be meaningful, and to ensure that the resulting Bayes factor is meaningful, the prior should correspond to realistic “weights” on the possible (nonzero) effect sizes. For this reason, an extremely vague prior for the average effect should not be used, such as a normal prior with a very large standard deviation. Such a prior would place a relatively large weights at unrealistically large effect sizes, resulting in extremely small marginal likelihoods under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

for typical (“small” to “large”) effect sizes, thereby heavily biasing the evidence in favor of the null.Footnote iii This is illustrated in Figure 3 (left panel) when testing the average effect under an RE model for the meta-analysis of McNeely et al.Reference McNeely, Campbell and Ospina37 when placing a normal prior on

$\mathcal {H}_1$

for typical (“small” to “large”) effect sizes, thereby heavily biasing the evidence in favor of the null.Footnote iii This is illustrated in Figure 3 (left panel) when testing the average effect under an RE model for the meta-analysis of McNeely et al.Reference McNeely, Campbell and Ospina37 when placing a normal prior on

![]() $\mu $

with a mean of zero and we let the prior standard deviation gradually increase to very large values. As the prior standard deviation of the normal prior increases to unrealistically large effect sizes, the Bayes factor gradually decreases toward zero implying that the evidence in favor of

$\mu $

with a mean of zero and we let the prior standard deviation gradually increase to very large values. As the prior standard deviation of the normal prior increases to unrealistically large effect sizes, the Bayes factor gradually decreases toward zero implying that the evidence in favor of

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

keeps increasing. Furthermore, the right panel of Figure 3 illustrates that when using a prior standard deviation of 5, the prior places lower weights around the likelihood (which is concentrated around

$\mathcal {H}_0$

keeps increasing. Furthermore, the right panel of Figure 3 illustrates that when using a prior standard deviation of 5, the prior places lower weights around the likelihood (which is concentrated around

![]() $\hat {\mu }=0.416$

), than when using a prior standard deviation of 1. Thus, the marginal likelihood of

$\hat {\mu }=0.416$

), than when using a prior standard deviation of 1. Thus, the marginal likelihood of

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

is lower when a prior standard deviation of 5 is used, as can also be seen from the lower Bayes factor in the left panel in Figure 3.

$\mathcal {H}_1$

is lower when a prior standard deviation of 5 is used, as can also be seen from the lower Bayes factor in the left panel in Figure 3.

4.2. Priors for the average effect

The prior for the (average) effect in the case of a standardized mean difference can be specified based on different considerations. Because we are testing whether the average effect is zero or not, a natural choice would be to center the prior at zero so that negative effects are equally likely as positive effects, and so that small effects are on average more likely than large effects before observing the data. Moreover, as the distribution of the observed effect given the unknown true effect is also normal, a (conjugate) normal prior would be a natural choice. The choice of the prior standard deviation is particularly important as was illustrated from Bartlett’s paradox (Figure 3). A standard deviation of 1 is the default in the R packages RoBMAReference Bartoš and Maier60 and BFpackReference Mulder, Williams and Gu36 implying fairly large effects to be plausible. In metaBMA, the more heavy tailed Cauchy prior with scale

![]() $0.707$

is the default.

$0.707$

is the default.

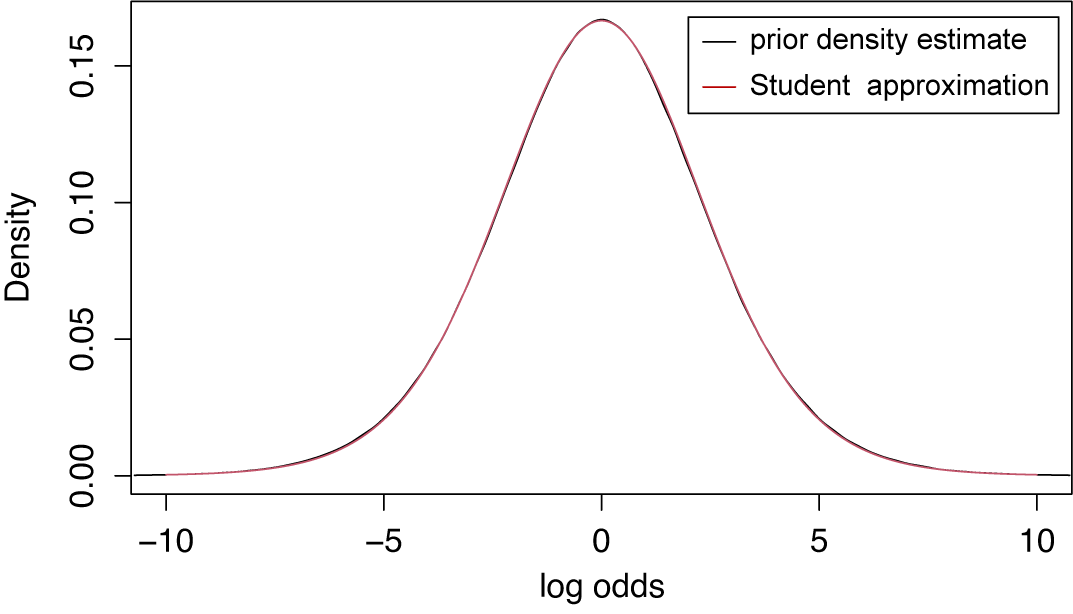

For a log odds ratio as an effect size measure (which lies on an approximate normal scale), one could start with placing priors on the success probabilities in the two groups (e.g., treatment and control), which are then transformed to the log odds ratio. As a default choice, proper independent uniform priors can be specified for the success probabilities which assume that all success probabilities are equally likely a priori. By transforming these to the log odds ratio, an approximate t distribution having a scale of 2.35 and 13 degrees of freedom is obtained (Appendix B). This is the default in BFpack. Another option could be to start with a prior for a mean effect, e.g.,

![]() $\mathcal {N}(0,1)$

prior, and convert this prior to the log odds scale the transformation formulas of Borenstein et al. (Chapter 7).Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein43 This is the default in RoBMA and in this case the scale of the prior distribution is approximately the same regardless of whether the standardized mean difference or log odds ratio is the effect size measure of interest. In metaBMA, the default scale of the prior distributions is also adjusted to the effect size measure: a Cauchy prior with scale 1.283 is used, because the distribution of log odds ratio is approximately 1.81 times as wide as that of the standardized mean difference. The use of conversion formulas may be particularly useful when the scales of the outcome variables varied across studies in the same meta-analysis. Synthesizing evidence from highly heterogeneous outcomes having different measurement levels is only recommended of course when this is substantively meaningful.

$\mathcal {N}(0,1)$

prior, and convert this prior to the log odds scale the transformation formulas of Borenstein et al. (Chapter 7).Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein43 This is the default in RoBMA and in this case the scale of the prior distribution is approximately the same regardless of whether the standardized mean difference or log odds ratio is the effect size measure of interest. In metaBMA, the default scale of the prior distributions is also adjusted to the effect size measure: a Cauchy prior with scale 1.283 is used, because the distribution of log odds ratio is approximately 1.81 times as wide as that of the standardized mean difference. The use of conversion formulas may be particularly useful when the scales of the outcome variables varied across studies in the same meta-analysis. Synthesizing evidence from highly heterogeneous outcomes having different measurement levels is only recommended of course when this is substantively meaningful.

Pearson correlation coefficients are commonly meta-analyzed after applying Fisher’s z transformation.Reference Fisher66 Fisher’s z transformed correlations are approximately normally distributed. For a Fisher transformed correlation, one can specify a prior for the correlation in the interval

![]() $(-1,1)$

, which can then be transformed by applying Fisher’s z transformation. A natural proper noninformative choice for a correlation would be to use a uniform prior in the interval

$(-1,1)$

, which can then be transformed by applying Fisher’s z transformation. A natural proper noninformative choice for a correlation would be to use a uniform prior in the interval

![]() $(-1,1)$

.Reference Jeffreys11,

Reference Mulder and Gelissen67,

Reference Mulder68 After applying a parameter transformation, this corresponds to a logistic prior distribution with a scale of 0.5 for Fisher’s z transformed correlation (Appendix B). This is the current default in BFpack. Alternatively, one could again use the conversion formulas from Borenstein et al.,Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein43 which is the default in RoBMA. In metaBMA, a Cauchy prior with a scale of 0.354 is the default to take into account that the distribution of Fisher’s z transformed correlations in relation to the distribution of standardized mean differences.

$(-1,1)$

.Reference Jeffreys11,

Reference Mulder and Gelissen67,

Reference Mulder68 After applying a parameter transformation, this corresponds to a logistic prior distribution with a scale of 0.5 for Fisher’s z transformed correlation (Appendix B). This is the current default in BFpack. Alternatively, one could again use the conversion formulas from Borenstein et al.,Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein43 which is the default in RoBMA. In metaBMA, a Cauchy prior with a scale of 0.354 is the default to take into account that the distribution of Fisher’s z transformed correlations in relation to the distribution of standardized mean differences.

As a general default choice for the prior, that is independent of the effect size measure, a unit-information prior can also be specified, which contains the information of a single observation.Reference Röver, Bender and Dias69 By construction, the amount of prior information is then relative to the amount of information in the sample instead of being based on contextual information about the key parameter. Therefore, this prior can be used as a general default. Note that the evidence as quantified by the well-known Bayesian information criterion (BIC)Reference Schwarz70 also behaves as an approximate Bayes factor based on a unit-information prior.Reference Raftery71,

Reference Kass and Wasserman72 The information of one observation depends on whether between-study heterogeneity is present or not. Under the CE model, where between-study heterogeneity is absent, the unit-information prior follows a normal distribution having a mean of 0 and a prior variance that is equal to the error variance rescaled to the total sample size, i.e.,

![]() $\mathcal {N}(0,N/\sum _i 1/\sigma _i^2)$

, where

$\mathcal {N}(0,N/\sum _i 1/\sigma _i^2)$

, where

![]() $N=\sum _i n_i$

denotes the total sample size across studies. Under the RE model and the hybrid models, a conditional prior for the average effect

$N=\sum _i n_i$

denotes the total sample size across studies. Under the RE model and the hybrid models, a conditional prior for the average effect

![]() $\mu $

is required conditional on

$\mu $

is required conditional on

![]() $\tau ^2$

, which follows a normal

$\tau ^2$

, which follows a normal

![]() $\mathcal {N}(0,N/\sum _i(\sigma ^2_i+\tau ^2)^{-1})$

distribution.Footnote iv This prior needs to be combined with a prior for

$\mathcal {N}(0,N/\sum _i(\sigma ^2_i+\tau ^2)^{-1})$

distribution.Footnote iv This prior needs to be combined with a prior for

![]() $\tau ^2$

(discussed later) to construct a joint prior for

$\tau ^2$

(discussed later) to construct a joint prior for

![]() $\mu $

and

$\mu $

and

![]() $\tau ^2$

under

$\tau ^2$

under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

.(Note that such prior dependency between

$\mathcal {H}_1$

.(Note that such prior dependency between

![]() $\mu$

and

$\mu$

and

![]() ${\tau}^2$

is common in the objective Bayesian literature for Bayes factor testing.Reference Liang, Paulo, Molina, Clyde and Berger65,

Reference Zellner73,

Reference Bayarri, Berger, Forte and García-Donato74)

${\tau}^2$

is common in the objective Bayesian literature for Bayes factor testing.Reference Liang, Paulo, Molina, Clyde and Berger65,

Reference Zellner73,

Reference Bayarri, Berger, Forte and García-Donato74)

When viewing a prior of the average effect as a population distribution of effect sizes from which the unknown effect size of a current meta-analysis is “drawn,” one can use the estimated distribution of effect sizes from published research to create an empirically informed prior. This has been done for meta-analyses of binary data with rare events,Reference Günhan, Röver and Friede75 for medicine and its subfields,Reference Bartoš, Gronau, Timmers, Otte, Ly and Wagenmakers76 and for binary trial data and time-to-event data,Reference Bartoš, Otte, Gronau, Timmers, Ly and Wagenmakers77 for example. Depending on the availability of relevant published effect sizes given the meta-analysis at hand, such an approach may be reasonable. A prior for the average effect has also been elicited for a meta-analysis using external knowledge regarding the effect size at hand.Reference Gronau, Van Erp, Heck, Cesario, Jonas and Wagenmakers78

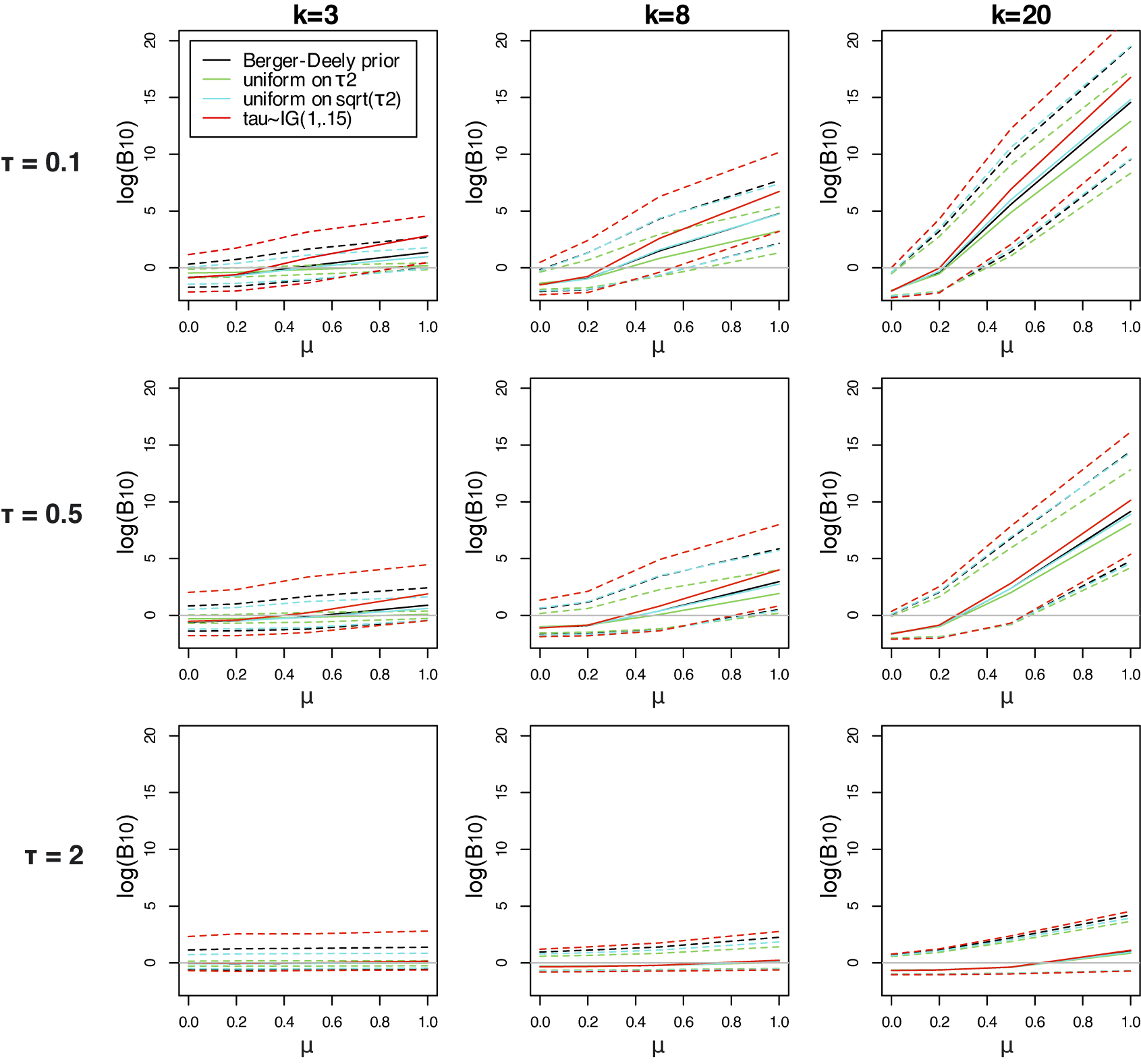

4.3. Priors for the between-study heterogeneity

Under the RE model and the hybrid models, a prior for the between-study heterogeneity also needs to be chosen.Reference Röver62,

Reference Pateras, Nikolakopoulos and Roes79,

Reference Spiegelhalter, Abrams and Myles80 As this is a common nuisance parameter under both hypotheses,

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

and

$\mathcal {H}_1$

and

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

, the Bayes factor for testing the global effect is considerably less sensitive to the exact choice of this prior.Reference Kass and Raftery12 This feature is advantageous, as specifying an informative prior for the between-study heterogeneity can be challenging due to its less intuitive interpretation. Interestingly, it is also possible to employ a noninformative improper prior for this common nuisance parameter,Footnote v allowing a default Bayes factor test.

$\mathcal {H}_0$

, the Bayes factor for testing the global effect is considerably less sensitive to the exact choice of this prior.Reference Kass and Raftery12 This feature is advantageous, as specifying an informative prior for the between-study heterogeneity can be challenging due to its less intuitive interpretation. Interestingly, it is also possible to employ a noninformative improper prior for this common nuisance parameter,Footnote v allowing a default Bayes factor test.

As summarized by Röver,Reference Röver62 there is an extensive literature on noninformative (“objective” and “default”) priors for the between-study heterogeneity

![]() $\tau ^2$

. For researchers with a less mathematical statistical background, it will be difficult to choose one specific noninformative prior based on the available theoretical and statistical arguments. Moreover, noninformative priors have often been assessed based on their implied behavior in Bayesian estimation problems rather than their implied behavior in hypothesis testing using Bayes factors. To keep the discussion as concise as possible, we restrict ourselves to certain noninformative priors rather than providing a complete assessment of all possible priors.

$\tau ^2$

. For researchers with a less mathematical statistical background, it will be difficult to choose one specific noninformative prior based on the available theoretical and statistical arguments. Moreover, noninformative priors have often been assessed based on their implied behavior in Bayesian estimation problems rather than their implied behavior in hypothesis testing using Bayes factors. To keep the discussion as concise as possible, we restrict ourselves to certain noninformative priors rather than providing a complete assessment of all possible priors.

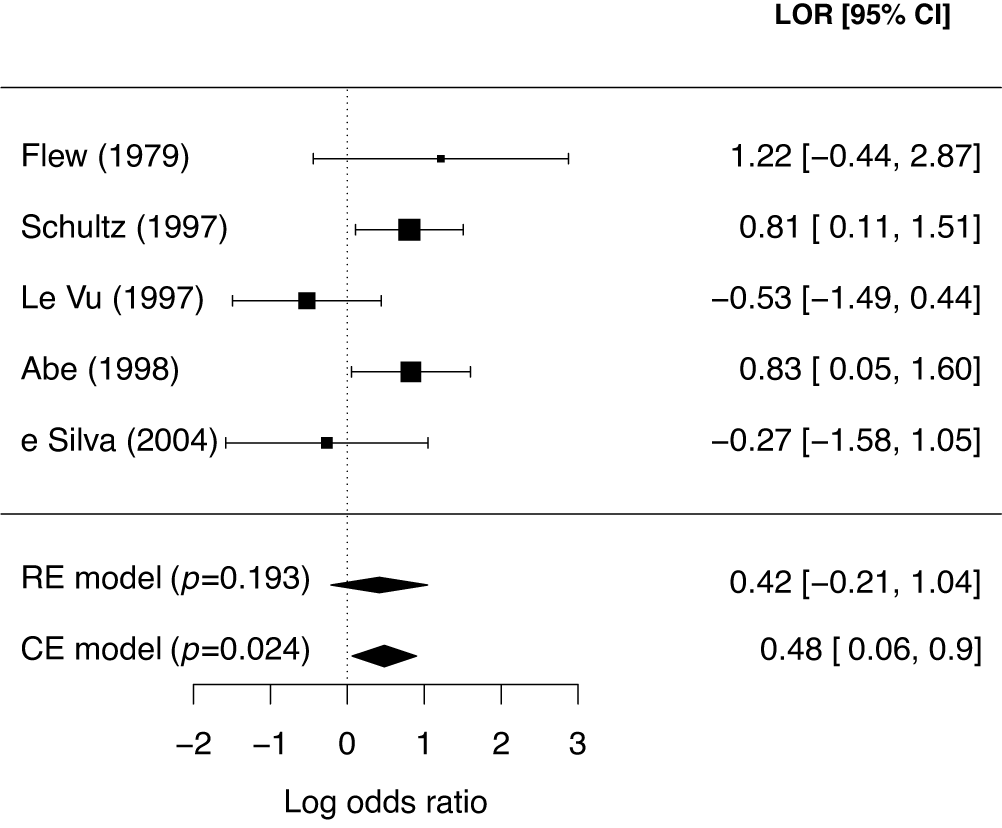

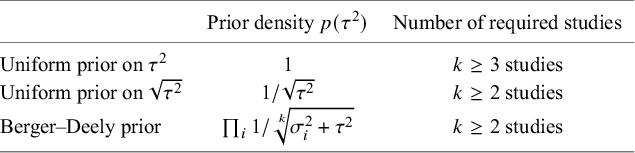

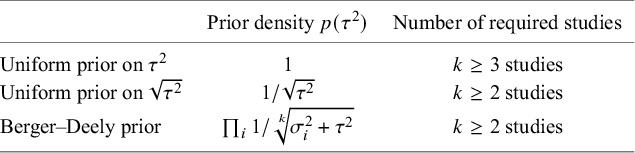

One important criterion for a noninformative improper prior is whether the resulting Bayes factor is well-defined. This is the case when the marginal likelihoods are finite. In an estimation problem, this is equivalent to the important criterion of that the posterior is proper. Table 3 provides three possible noninformative improper priors for the between-study variance when testing the global mean, including the minimal number of studies for a well-defined Bayes factor. The uniform prior on

![]() $\sqrt {\tau ^2}$

or the Berger–Deely priorReference Berger and Deely63 may be preferred as Bayes factor testing will already be possible when only two studies are available. From these two priors, the Berger–Deely prior is conjugate under the RE model, and therefore a more natural choice. Moreover, the Berger–Deely prior naturally extends to the marema modelFootnote vi (the Berger–Deely prior is the default in BFpack; Table 2). Furthermore, the scale invariant prior,

$\sqrt {\tau ^2}$

or the Berger–Deely priorReference Berger and Deely63 may be preferred as Bayes factor testing will already be possible when only two studies are available. From these two priors, the Berger–Deely prior is conjugate under the RE model, and therefore a more natural choice. Moreover, the Berger–Deely prior naturally extends to the marema modelFootnote vi (the Berger–Deely prior is the default in BFpack; Table 2). Furthermore, the scale invariant prior,

![]() $1/\tau ^2$

, which is also Jeffreys’ prior, is not recommended for lower level variances such as the between-study heterogeneity.Reference Gelman82 This prior may result in infinite marginal likelihoods (and improper posteriors in Bayesian estimation) when the between-study heterogeneity in the data is very low, and is therefore not recommended. Finally, we note that proper approximations of noninformative improper priorsReference Pateras, Nikolakopoulos and Roes79,

Reference Spiegelhalter83 should be used with care, as they may unduly be highly noninformative.Reference Gelman82,

Reference Berger84

$1/\tau ^2$

, which is also Jeffreys’ prior, is not recommended for lower level variances such as the between-study heterogeneity.Reference Gelman82 This prior may result in infinite marginal likelihoods (and improper posteriors in Bayesian estimation) when the between-study heterogeneity in the data is very low, and is therefore not recommended. Finally, we note that proper approximations of noninformative improper priorsReference Pateras, Nikolakopoulos and Roes79,

Reference Spiegelhalter83 should be used with care, as they may unduly be highly noninformative.Reference Gelman82,

Reference Berger84

Table 3 Three possible noninformative priors for the between-study heterogeneity

![]() $\tau ^2$

and the number of required studies to obtain a finite Bayes factor.

$\tau ^2$

and the number of required studies to obtain a finite Bayes factor.

Empirically informed priors have also been proposed for the between-study heterogeneity.Reference Turner, Jackson, Wei, Thompson and Higgins6,

Reference Rhodes, Turner and Higgins25,

Reference Pullenayegum85,

Reference Van Erp, Verhagen, Grasman and Wagenmakers86 These empirically informed priors have mostly been used for estimation problems, although there is also literature where these priors have also been used for Bayes factor testing in meta-analyses.Reference Bartoš, Otte, Gronau, Timmers, Ly and Wagenmakers77,

Reference Gronau, Van Erp, Heck, Cesario, Jonas and Wagenmakers78 A complicating factor which is often overlooked is that the between-study variance under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

will never be larger than the between-study variance under

$\mathcal {H}_1$

will never be larger than the between-study variance under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

as the mean is restricted under

$\mathcal {H}_0$

as the mean is restricted under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

. For this reason, it would be preferred to incorporate this in the informative priors (by ensuring that

$\mathcal {H}_0$

. For this reason, it would be preferred to incorporate this in the informative priors (by ensuring that

![]() $\tau ^2$

is stochastically larger under

$\tau ^2$

is stochastically larger under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

than under

$\mathcal {H}_0$

than under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

a priori). To our knowledge, no priors have been proposed so far that abide this property. In the end, the suitability of informed priors would need to be carefully assessed depending on the meta-analysis at hand.

$\mathcal {H}_1$

a priori). To our knowledge, no priors have been proposed so far that abide this property. In the end, the suitability of informed priors would need to be carefully assessed depending on the meta-analysis at hand.

Currently, the R package “BFpack” supports the use of noninformative improper priors for the between-study heterogeneity. Since the R packages “metaBMA” and “RoBMA” perform BMA between the CE model (

![]() $\tau ^2 = 0$

) and the RE model (

$\tau ^2 = 0$

) and the RE model (

![]() $\tau ^2> 0$

), calculating Bayes factors is necessary to determine the posterior model weights. This test treats

$\tau ^2> 0$

), calculating Bayes factors is necessary to determine the posterior model weights. This test treats

![]() $\tau ^2$

as a parameter of interest rather than a nuisance parameter, precluding the use of noninformative improper or arbitrarily vague priors. These two packages do allow a noninformative improper prior for

$\tau ^2$

as a parameter of interest rather than a nuisance parameter, precluding the use of noninformative improper or arbitrarily vague priors. These two packages do allow a noninformative improper prior for

![]() $\tau ^2$

when solely working under the RE model (implying that the CE model is disregarded and BMA is not used). Based on our experience, the “bayesmeta” package does not support noninformative improper priors for the nuisance parameter when testing the overall effect.

$\tau ^2$

when solely working under the RE model (implying that the CE model is disregarded and BMA is not used). Based on our experience, the “bayesmeta” package does not support noninformative improper priors for the nuisance parameter when testing the overall effect.

4.4. Final remarks on prior specification

On a more theoretical note, it has been argued that priors should result in Bayes factors that are information consistent.Reference Liang, Paulo, Molina, Clyde and Berger65,

Reference Gronau, Ly and Wagenmakers87,

Reference Mulder, Berger, Peña and Bayarri88 Information consistency implies that the evidence for the alternative should go to infinity when the estimated effect goes to plus or minus infinity. Roughly speaking, Bayes factors are not information consistent when the (marginal) prior for the mean effect has thinner tails than the (integrated) likelihood as a function of the mean effect (after integrating out the nuisance parameter

![]() $\tau ^2$

). As the integrated likelihood follows an approximate Student t distribution under the RE model, information consistency is assured when using a prior with thicker tails, such as a Cauchy prior. As was shown by Mulder et al.,Reference Mulder, Berger, Peña and Bayarri88 a normal marginal prior (having very thin tails) can be detrimental when the effect size is extremely large (such as standardized effect sizes of 10) causing the relative evidence to be approximately 1 (suggesting equal evidence for the null and alternative). For the CE and FE models, the likelihood as a function of the mean has a Gaussian shape, which already has thin tails. Therefore, information inconsistency would not even occur when using a normal prior. Based on our experience, information consistency is mainly a theoretical property and not a practical one as effect sizes are generally not that extreme such that an information inconsistent Bayes factor would result in conflicting behavior. Therefore, information consistency may not be a serious concern when choosing priors in general.

$\tau ^2$

). As the integrated likelihood follows an approximate Student t distribution under the RE model, information consistency is assured when using a prior with thicker tails, such as a Cauchy prior. As was shown by Mulder et al.,Reference Mulder, Berger, Peña and Bayarri88 a normal marginal prior (having very thin tails) can be detrimental when the effect size is extremely large (such as standardized effect sizes of 10) causing the relative evidence to be approximately 1 (suggesting equal evidence for the null and alternative). For the CE and FE models, the likelihood as a function of the mean has a Gaussian shape, which already has thin tails. Therefore, information inconsistency would not even occur when using a normal prior. Based on our experience, information consistency is mainly a theoretical property and not a practical one as effect sizes are generally not that extreme such that an information inconsistent Bayes factor would result in conflicting behavior. Therefore, information consistency may not be a serious concern when choosing priors in general.

Generic approximate Bayesian approaches are also available which avoid manual prior specification, such as the BICReference Schwarz70, Reference Raftery71 or fractional/intrinsic Bayes factors,Reference Berger and Pericchi89– Reference Mulder91 or approximations thereof.Reference Gu, Mulder and Hoijtink92 These methods have, for instance, been been applied for FE meta-analyses.Reference Kuiper, Buskens, Raub and Hoijtink34, Reference Wonderen, Zondervan-Zwijnenburg and Klugkist35, Reference Van Lissa, Clapper and Kuiper44 Implicitly, these approximations abide the principle of minimally informative priors, comparable to the unit-information prior. To simplify the interpretation of the evidence however, it may be preferred to only use these approximate methods for hypothesis testing problems which are not supported by the available Bayesian meta-analysis software (e.g., due to the formulated hypotheses, the statistical models, or the research designs).

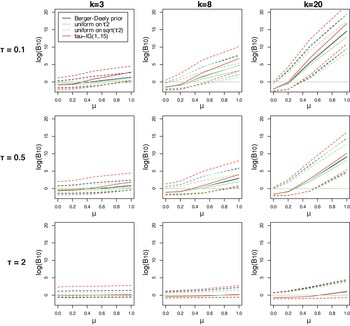

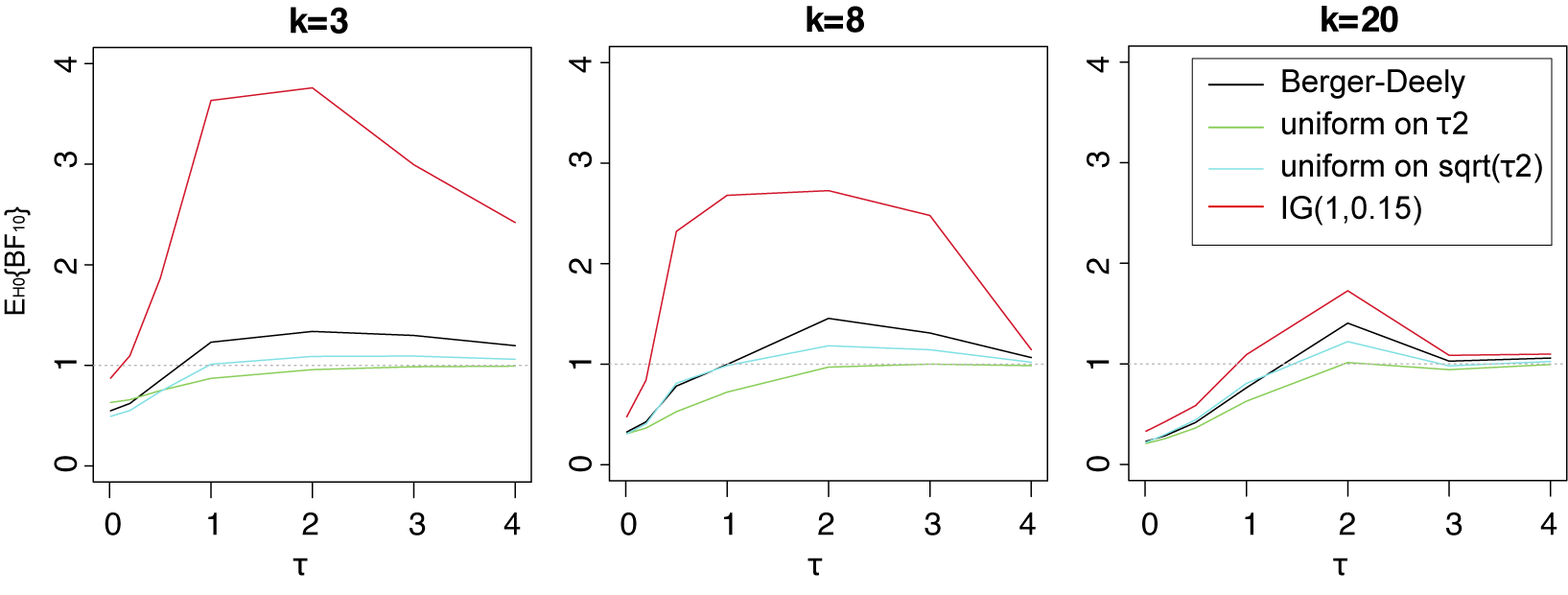

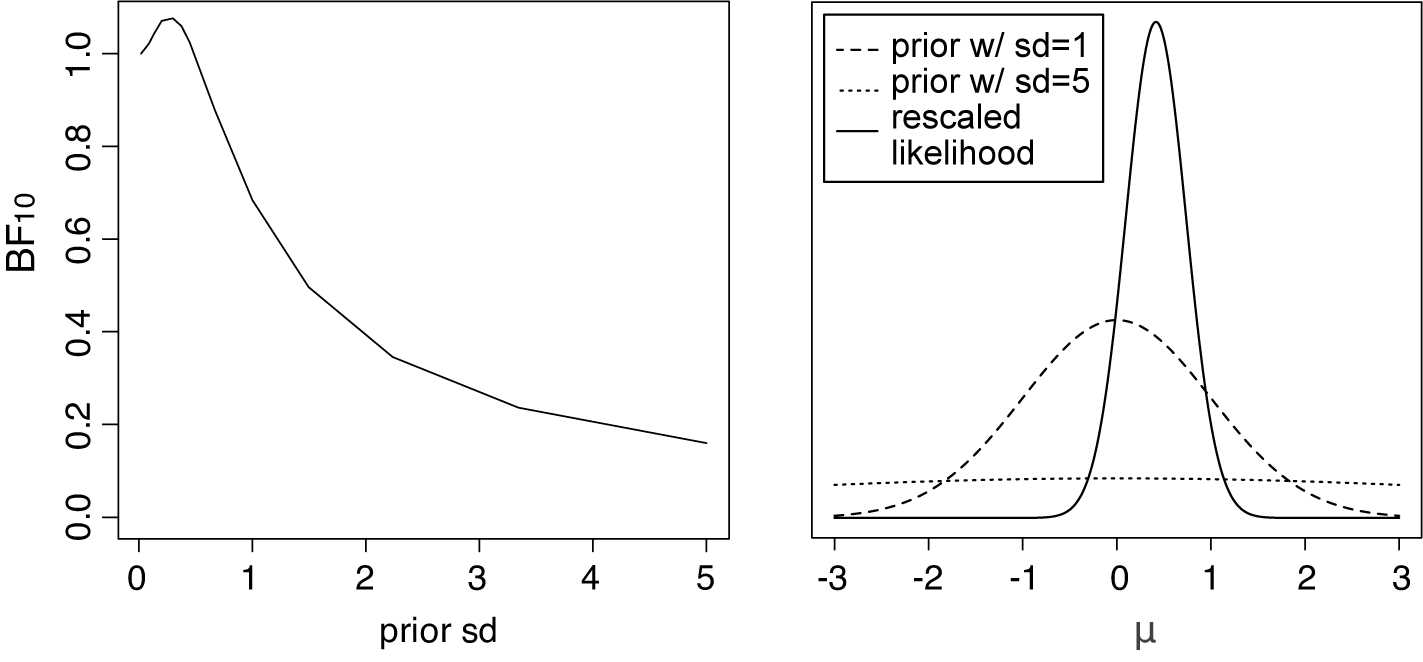

Finally, Appendix C presents a small simulation on the sensitivity of the Bayes factor to the prior of the nuisance between-study heterogeneity. As shown, the Bayes factor is quite robust to the exact choice.

5. Computing Bayes factors for evidence synthesis

Depending on the employed meta-analytic model, as well as on the chosen prior (e.g., whether a conjugate prior was used), the complexity of the computation of the Bayes factor differs. Moreover, when a new study becomes available, updating the Bayes factor can be done via different formulas.

5.1. Evidence synthesis via (regular) Bayesian updating

Under the CE model, the RE model, and the hybrid models, evidence updating is done in a similar manner as regular Bayesian updating in estimation. In Bayesian estimation, we need to update the posterior when a new study is reported. The posterior based on the previous studies becomes the prior, which is then multiplied (“combined”) with the likelihood of the new study to obtain the new posterior via Bayes’ theorem. When testing hypotheses, we update the Bayes factor based on the previous

![]() $k-1$

studies with the Bayes factor for the new k-th study using the posteriors based on the previous studies under the hypotheses as prior for computing the marginal likelihoods. Under

$k-1$

studies with the Bayes factor for the new k-th study using the posteriors based on the previous studies under the hypotheses as prior for computing the marginal likelihoods. Under

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

, this can be written as

$\mathcal {H}_1$

, this can be written as

This follows from basic probability calculus.Reference Ly, Etz, Marsman and Wagenmakers22 Consequently, we can also write the Bayes factor for all

![]() $k+1$

studies according to

$k+1$

studies according to

Rather than using this updating scheme explicitly, meta-analysts will likely compute the Bayes factor based on the

![]() $k+1$

studies “from scratch” because R packages generally only have functions for computing marginal likelihoods and Bayes factors for a given set of studies. Computing Bayes factors for a given set of studies is generally done by computing the marginal likelihoods using numerical algorithms (e.g., based on bridge samplingReference Bennett93 using the R package “bridgesampling,”Reference Gronau, Singmann and Wagenmakers94 or importance sampling,Reference Meng and Wong95 as used in the R package “BFpack,”Reference Mulder, Williams and Gu36 for instance). When no nuisance parameters are present (as in the CE model) or when the prior of the key parameter is independent of the prior of the nuisance parameter, for instance, it is also possible to compute the Bayes factor using the Savage–Dickey density ratio.Reference Dickey96 This quantity is relatively easy to compute from MCMC output (e.g., using StanReference Carpenter, Gelman and Hoffman97 or JAGS,Reference Plummer98 for example). Here, we briefly explain this as it may give readers some extra intuition since viewing the behavior of Bayes factors as marginal likelihoods may be less intuitive.

$k+1$

studies “from scratch” because R packages generally only have functions for computing marginal likelihoods and Bayes factors for a given set of studies. Computing Bayes factors for a given set of studies is generally done by computing the marginal likelihoods using numerical algorithms (e.g., based on bridge samplingReference Bennett93 using the R package “bridgesampling,”Reference Gronau, Singmann and Wagenmakers94 or importance sampling,Reference Meng and Wong95 as used in the R package “BFpack,”Reference Mulder, Williams and Gu36 for instance). When no nuisance parameters are present (as in the CE model) or when the prior of the key parameter is independent of the prior of the nuisance parameter, for instance, it is also possible to compute the Bayes factor using the Savage–Dickey density ratio.Reference Dickey96 This quantity is relatively easy to compute from MCMC output (e.g., using StanReference Carpenter, Gelman and Hoffman97 or JAGS,Reference Plummer98 for example). Here, we briefly explain this as it may give readers some extra intuition since viewing the behavior of Bayes factors as marginal likelihoods may be less intuitive.

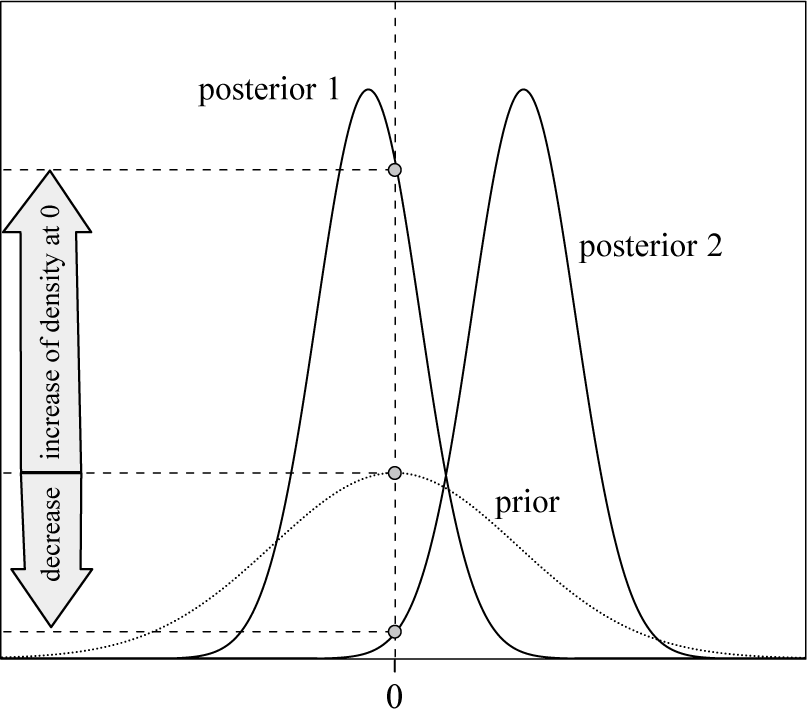

The Savage–Dickey density ratio is defined by evaluating the posterior density of

![]() $\theta $

under the unconstrained hypothesis

$\theta $

under the unconstrained hypothesis

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

, at the null value divided by the unconstrained prior density at the null valueReference Dickey96:

$\mathcal {H}_1$

, at the null value divided by the unconstrained prior density at the null valueReference Dickey96:

Thus, we can compute the Bayes factor in favor of

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

by simply computing the posterior of

$\mathcal {H}_0$

by simply computing the posterior of

![]() $\theta $

(which is obtained from an estimation step) at zero divided by the chosen prior for

$\theta $

(which is obtained from an estimation step) at zero divided by the chosen prior for

![]() $\theta $

at zero. The posterior density at the null value can easily be obtained from MCMC output with Bayesian software (e.g., Stan or JAGS). The prior density at the null value generally has an analytic form when the prior belongs to a common family of probability distributions. Consequently, if the density at zero increases from prior to posterior, then there is evidence in favor of the null value, and vice versa (Figure 4). In the case, a normal prior is considered, the Bayes factor has an analytic expression and thus numerical algorithms can be avoided (Appendix D).

$\theta $

at zero. The posterior density at the null value can easily be obtained from MCMC output with Bayesian software (e.g., Stan or JAGS). The prior density at the null value generally has an analytic form when the prior belongs to a common family of probability distributions. Consequently, if the density at zero increases from prior to posterior, then there is evidence in favor of the null value, and vice versa (Figure 4). In the case, a normal prior is considered, the Bayes factor has an analytic expression and thus numerical algorithms can be avoided (Appendix D).

Figure 4 Evidence for

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

based on a Savage–Dickey density ratio. In case of posterior 1, there is evidence for

$\mathcal {H}_0$

based on a Savage–Dickey density ratio. In case of posterior 1, there is evidence for

![]() $\mathcal {H}_0$

, and in case of posterior 2, there would be evidence for

$\mathcal {H}_0$

, and in case of posterior 2, there would be evidence for

![]() $\mathcal {H}_1$

.

$\mathcal {H}_1$

.

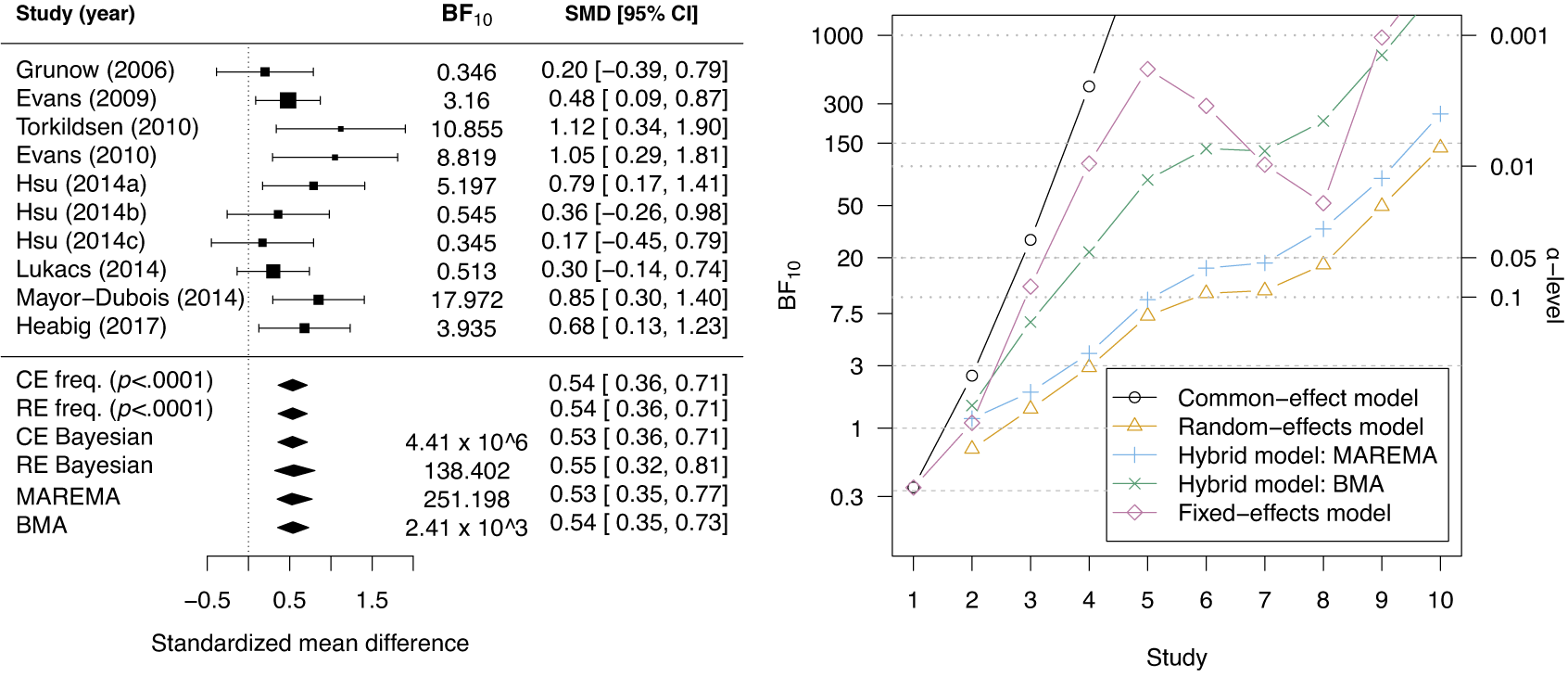

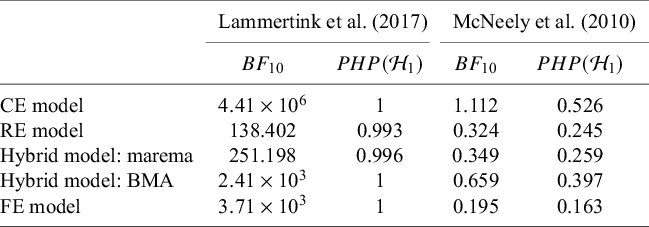

5.2. Evidence synthesis via the product Bayes factor