Introduction

How do technological innovations, such as social media, transform agenda setting between political parties? The extent to which political parties respond to each other and talk about the same issues is a crucial element in democracies. The presence or absence of issue engagement (also ‘issue convergence’ or ‘issue dialogue') between parties is an important democratic feature. First, voters only learn about similarities and differences in party proposals and positions, when parties talk about the same issues. Thus, issue engagement is a precondition for informed electoral decision‐making (Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2016; Sigelman & Buell, Reference Sigelman and Buell2004). Second, the streams of influence between parties shape public discourse and reflect political power relations. Those actors holding ‘discursive power’ are able to ‘introduce, amplify and maintain topics, frames and speakers that come to dominate public discourse’ (Jungherr et al., Reference Jungherr, Posegga and An2019, p. 406). The ability to set the political agenda or respond to issues raised by others is a key factor in political processes (Green‐Pedersen & Walgrave, Reference Green‐Pedersen, Walgrave, Green‐Pedersen and Walgrave2014).

Therefore, a rich body of literature on issue engagement has developed over the past decades. While some older studies indicate the absence of issue engagement in election campaigns (Budge & Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Spiliotes & Vavreck, Reference Spiliotes and Vavreck2002), more recent ones point towards issue engagement between political actors (e.g. Banda, Reference Banda2015; Dolezal et al., Reference Dolezal, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Müller and Winkler2014; Sigelman & Buell, Reference Sigelman and Buell2004). Further studies focus on the factors that influence issue engagement, such as electoral incentives, ideological orientations or organisational constraints (Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015; Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2016). However, the advent of social media and the development of so‐called hybrid media systems (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2017), where ‘older’ and ‘newer’ forms of political communication co‐exist and interact, have transformed party competition.

To what extent and how new communication channels, such as social media, have changed the nature of political debate in recent years is a hot topic. The academic literature attributes social media a central role in the ‘fourth phase of campaigning’, in which political actors have internalised media logics, communicate on a permanent basis and make use of data‐driven campaign strategies, thereby affecting political processes and public discourse (e.g. Roemmele & Gibson, Reference Roemmele and Gibson2020; Strömbäck, Reference Strömbäck2008). How social media and the ‘fourth phase of campaigning’ affect the functioning of democracies is thus subject to a broad debate and highly contested. While one perspective sees an ‘egalitarian effect’ of social media by reducing institutional and resource constraints and increasing flexibility in communication, thereby allowing new and smaller actors to enter the political arena, others are more pessimistic and attribute increasing societal fragmentation and polarisation to social media. This pessimistic view is probably best reflected by the buzzwords ‘filter bubbles’ and ‘echo chambers’, although their actual existence is empirically contested (e.g., Barberá et al., Reference Jost, Nagler, Tucker and Bonneau2015; Barberá, Reference Barberá, Persily and Tucker2020; Barnidge, Reference Barnidge2017). What is clear though is that social media has transformed party communication and political agenda setting (Gilardi, Gessler, et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2022). However, it remains unclear how exactly agenda setting between parties (i.e., issue engagement) changes on social media compared to more ‘traditional’ forms of political communication. As political discourse in contemporary democracies increasingly takes place online, it is crucial to understand the influence of social media on the dynamics of party competition and agenda setting. Does social media promote or limit discussions about specific issues between parties? Does it have an ‘egalitarian effect’ or does it perpetuate or even strengthen existing power relations? Do parties indeed talk past each other and withdraw into ‘echo chambers’ on social media, or not?

To investigate whether and how issue engagement differs between social media and more ‘traditional’ forms of political communication, I study the case of press releases and tweets from political parties in Austria, Germany and Switzerland (January 2019–September 2021). Press releases and the social media platform Twitter/X are widely used by political actors to disseminate news and communicate policies (e.g. Ennser‐Jedenastik et al., Reference Ennser‐Jedenastik, Haselmayer, Huber and Scharrer2022; Jungherr, Reference Jungherr2014). While press releases are well‐established ‘traditional’ communication tools, the micro‐blogging platform Twitter/XFootnote 1 has become the primary social media platform where political debates take place at the national level (e.g., Stier et al., Reference Stier, Bleier, Lietz and Strohmaier2018). Although some features have changed after Twitter was acquired by Elon Musk in October 2022 and subsequently renamed to X, it still functions in a similar way and remains a central platform for political actors and debates. Therefore, comparing press releases and tweets is a well‐suited set‐up to study issue engagement dynamics in contemporary political communication environments. Methodologically, I apply unsupervised topic modelling to extract issues and then statistically model issue engagement between parties in the press releases and tweets.

In this article, I argue that both the level and nature of issue engagement differ between press releases and tweets. The results show how different communication channels’ institutional and resource constraints, levels of flexibility and communication styles can affect issue engagement between parties. Overall, I find more issue engagement and different patterns of agenda setting between parties on Twitter than in press releases. First, party size has a smaller influence, supporting the argument that parties face fewer resource constraints on social media, allowing smaller parties to participate in the debate more actively. Second, government parties engage on issues raised by other parties more frequently on Twitter than in press releases. This may be due to a relatively confrontational communication style on the platform, which can be marked by attacks on power‐holders and their responses. Finally, the results show a limited role of ideological distance between parties for issue engagement both on Twitter and in press releases. Thus, I do not find evidence for an ‘echo chamber’ effect when it comes to issue engagement between parties on Twitter.

These findings have several implications for our understanding of party competition and political communication in contemporary democracies. The article adds to the debate about the transformative effect of new communication technologies on party competition and political discourse. The results suggest that different patterns of party competition exist in parallel, leading to potentially different perceptions of democratic processes and parties among voters. This is a particularly important finding as political communication becomes increasingly fragmented. Furthermore, the article adds important insights to the ongoing debate about the potential positive and negative effects of social media on political discourse, using Twitter as an example. First, the study finds higher levels of issue engagement on Twitter than in press releases. Thus, ‘newer’ forms of political communication, such as Twitter/X, do not appear to limit political discussions between political actors about certain issues per se. According to the findings of this study, parties address issues discussed by other parties more frequently on Twitter than in press releases, albeit potentially in a less extensive and detailed form. Second, the results lend support to the argument that social media can have an ‘egalitarian effect’ by reducing constraints on parties, allowing smaller actors to participate more actively in the political debate. Finally, and contrary to some pessimistic views, Twitter does not appear to stop parties – particularly ideologically different parties – from talking about the same issues. Thus, issue engagement between parties does not seem to be affected by an ‘echo chamber’ effect on Twitter. Overall, these findings show that ‘newer’ forms of political communication, such as the social media platform Twitter/X, can affect the nature of political debates and change discursive power relations between political actors.

Theoretical framework

In its minimalist definition, issue engagement (also ‘issue convergence’ or ‘issue dialogue') simply captures the extent to which political actors (e.g., parties) talk about the same issues during a specific point in time, such as during an election campaign (e.g., Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Park and Ridout2006; Sigelman & Buell, Reference Sigelman and Buell2004). This is a quite static conceptualisation. The term ‘engagement’, however, also implies a more dynamic process (see Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2016) in which political actors address issues, respond to each other and engage in (daily) discussions about specific political problems or policies. To conceptualise this process, it is helpful to break it down to a smaller level. Issue engagement can be thought of as an interaction between two parties. When one party communicates an issue, it acts as a source of information for the other party, and the latter party then either addresses that issue as well or not. Therefore, I understand it as ‘engagement’ if a party addresses an issue discussed by another party (‘source') within a specified time frame.

Unlike related concepts that focus on very specific aspects or have specific connotations, such as the presence or absence of substantive conversations between parties (‘issue dialogue’; see Simon, Reference Simon2002) or positional changes (‘issue convergence’; see Damore, Reference Damore2005; Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Park and Ridout2006), issue engagement as understood in this article allows to capture a broad range of dynamics between parties. Following the conceptualisation used in this article, issue engagement occurs, for example, when two parties specifically discuss the same policy or event within an issue area, come into direct conflict on an issue, discuss the same issue but with different frames, positions or issue emphasis or simply mention an issue at the same time. This understanding offers the advantage of covering the variety of issue engagement dynamics relevant to party competition with one concept but also has the limitation of not allowing a detailed differentiation between them.

When and why do parties address issues discussed by a competitor? Existing research has uncovered several reasons why parties may address issues communicated by other parties as well as reasons why they may abstain from it. First, issue‐specific attributes and related strategic choices are an important factor. On the one hand, issue engagement can signal interest in issues and problems that are important to the public or in the media (e.g., Damore, Reference Damore2005; Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Hennessy, Kifer and Parkin2010). This way, issue engagement can show that a party cares about voters’ interests and concerns and can therefore be a potentially vote‐winning strategy (Spoon et al., Reference Spoon, Hobolt and Vries2014). On the other hand, parties may want to give full attention to their strongest issues and avoid issues raised by other parties (Budge & Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996). Furthermore, the complexity or familiarity of issues can influence engagement (Hänggli, Reference Hänggli2020). Second, institutional contexts have been found to influence issue engagement between political actors, such as the competitiveness of election races (e.g., Banda, Reference Banda2015; Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Park and Ridout2006) or direct democracy (e.g. Hänggli, Reference Hänggli2020). Third, parties may be incentivised to engage with issues to (re)frame them to their own advantage (e.g., Nadeau et al., Reference Nadeau, Pétry and Bélanger2010). Fourth, issue engagement can occur when multiple political actors align in issue‐specific discourse coalitions (e.g., Markard et al., Reference Markard, Rinscheid and Widdel2021; Williams & Sovacool, Reference Williams and Sovacool2020).

Finally, several party‐level factors have been shown to influence issue engagement, and these are also the focus of this article. For example, Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen (Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015) and Meyer and Wagner (Reference Meyer and Wagner2016) find that issue engagement is stronger between ideologically proximate parties competing for similar voter groups. Furthermore, parties’ organisational features affect issue engagement. Large parties with many resources (e.g., financial means, personnel) have been found to engage with other parties on a broader set of issues than smaller parties (Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2016). Other organisational features, such as leadership or activist orientation, also affect the range of issues addressed by parties and thus (potentially) issue engagement (Van Heck, Reference Heck2018). Hence, parties' ideological orientations and organisational constraints are important moderating factors according to existing research. Another potential factor is government participation. Opposition parties usually seek to push issues on the agenda on which the government has a poor record to force government parties to respond to these issues. Although intuitive, empirical evidence for such behaviour is so far mixed (see Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2010; Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2016).

The advent of social media now raises the question whether it has transformed issue engagement between political parties. Most existing research discussed above focuses on ‘traditional’ forms of party communication, such as manifestos (Dolezal et al., Reference Dolezal, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Müller and Winkler2014; Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015), press releases (Meyer and Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2016), campaign advertising (Banda, Reference Banda2015; Spiliotes & Vavreck, Reference Spiliotes and Vavreck2002) or parliamentary activities (Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2010). Social media, however, provides a different venue and opportunity structure for political actors.

The rise of social media is inherently linked to what Roemmele and Gibson (Reference Roemmele and Gibson2020) call the ‘fourth phase of political campaigning’. Several features of social media platforms have contributed to changes in the communication efforts of political parties. First of all, permanent campaigning has become even more important as news is produced and consumed 24/7 on social media and mobile devices. In this highly fluid news environment, political parties face a daily battle to shape the political debate. Here, social media platforms offer a vast network for voter persuasion, when parties can produce newsworthy messages that achieve virality (e.g., Al‐Rawi, Reference Al‐Rawi2019; Strömbäck, Reference Strömbäck2008). Especially with regard to the visibility and virality of party messages, the content produced by parties as well as user engagement and algorithmic content selection on social media platforms play a crucial role (e.g., Maitra & Hänggli, Reference Maitra and Hänggli2023). Simultaneously, social media platforms allow parties to observe which issues and news are being shared online and attracting public attention and thus serve as an important tool for monitoring political debates and the ‘popular mood’ (Roemmele & Gibson, Reference Roemmele and Gibson2020). These developments have led to an expansion of professionalised staff managing parties' communication efforts as political actors increasingly adopt and internalise media logics (Strömbäck, Reference Strömbäck2008). Furthermore, social media has also changed how parties can connect with voters as it allows – at least to some extent – to circumvent the gatekeeping function of traditional news media and connect directly with voters (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2017; Gilardi, Gessler, et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2022). Furthermore, parties face fewer institutional and resource constraints on social media than on other channels. While press releases or campaign advertisements, for example, require more resources than social media posts, parliamentary activities are more regulated by partisan control of the legislative agenda or rules regarding speaking time (Herzog & Benoit, Reference Herzog and Benoit2015; Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2015). This characteristic of social media platforms offers parties more flexibility in their communications, for example, in terms of which issues they address, to what extent, at what time and how. Therefore, the advent of social media platforms has contributed significantly to changes in party communication in the ‘fourth phase of political campaigning’.

These developments have led several authors to conclude that social media also plays an increasingly transformative role in political agenda setting (e.g., Feezell, Reference Feezell2018; Gilardi, Gessler, et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2022; Lewandowsky et al., Reference Lewandowsky, Jetter and Ecker2020). As discussed above, political actors nowadays face a permanent battle to shape the political debate, that is, to set the political agenda. Furthermore, the changes in communication efforts and contexts (e.g., resources) brought about by social media can (potentially) shift power relations between political actors. Building on these insights, I argue that the use of different forms of political communication (i.e., ‘newer’ and ‘older’ channels) also moderates the dynamics of issue engagement between parties in several ways. In my argument, I focus in particular on social media platforms that are broadly adopted by political actors and facilitate the discussion of political issues at the national level, such as the micro‐blogging platform Twitter/X (e.g., Stier et al., Reference Stier, Bleier, Lietz and Strohmaier2018). The theoretical framework and subsequent analysis therefore mainly refer to social media platforms that function similarly to Twitter/X. Given the plethora of social media platforms, such a focus is necessary to enable a meaningful and concise analysis. At the same time, however, it must also be borne in mind that the arguments presented in this article thus may not apply to all social media platforms in the same way.

First, I expect social media to moderate the level of issue engagement between parties. However, there are reasons both for a potential positive and negative effect of social media platforms. On the one hand, parties face less constraints with regard to regulations and required resources. This offers the potential for discussing and engaging on a broader set of issues (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2017; Gilardi, Gessler, et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2022; Russell, Reference Russell2018). Furthermore, social media allows parties to monitor the public debate (at least on the respective platform) in more detail and to respond more quickly to emerging issues. Following these arguments, one can expect more issue engagement on social media than in ‘traditional’ forms of political communication (e.g., press releases). On the other hand, social media allows to communicate with one's followers and voters directly and circumvent journalists as gatekeepers (Gilardi, Gessler, et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2022; Peeters et al., Reference Peeters, Aelst and Praet2021). Journalists are primarily interested in issues that are relevant to multiple different actors with potentially competing positions and interests (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Haselmayer and Wagner2020). Thus, parties have to engage on issues raised by other parties in order to attract attention from journalists and get their messages into the media. The ‘direct’ nature of social media, however, reduces this pressure resulting from the gatekeeping function of journalists. Following this argument, social media should show lower levels of issue engagement than ‘traditional’ forms of political communication. Based on these conflicting considerations regarding the extent of issue engagement on social media, I formulate two rival hypotheses.

H1a: Issue engagement between political parties is higher on social media platforms than in ‘traditional’ forms of party communication.

H1b: Issue engagement between political parties is lower on social media platforms than in ‘traditional’ forms of party communication.

Second, the use of social media platforms could intensify the influence of ideological distance on issue engagement between parties. As mentioned earlier, previous studies find that parties are more likely to respond to ideologically similar parties (e.g., Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015; Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2016). This effect could be further heightened on social media. According to a widespread argument, algorithmic content selection on social media platforms primarily shows users content that corresponds to their ideological viewpoints, eventually leading to a segregation of discourse along ideological and partisan lines (e.g., Pariser, Reference Pariser2011). Although empirical evidence questions the existence of full‐fledged ‘filter bubbles’ or ‘echo chambers’, social media indeed seems to support conversations among ideological peers (Barberá et al., Reference Jost, Nagler, Tucker and Bonneau2015; Barberá, Reference Barberá, Persily and Tucker2020). Therefore, I expect this characteristic of social media platforms to heighten the role of ideological positions and negatively influence issue engagement between ideologically distant parties.

H2: Issue engagement between ideologically distant parties is lower on social media platforms than in ‘traditional’ forms of party communication.

Third, I expect social media to reduce the effect of parties' organisational constraints on issue engagement. Specifically, I focus on party size in this article. Larger parties usually have more resources (i.e., financial means, personnel) at their disposal and can therefore more easily cover a broad range of issues (Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2016). Social media posts, however, often require much less resources than crafting press releases or campaign advertisements. This allows a broader and more diverse range of actors to participate in the political debate (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2017). I expect this ‘egalitarian effect’ to trump another characteristic of social media platforms, which could lead us to a counter hypothesis. Maitra and Hänggli (Reference Maitra and Hänggli2023), for example, find that due to algorithmic content selection, few political users dominate political discourse on the social media platform Facebook, although many speak. However, I argue that this should primarily affect voters' exposure to political information on social media rather than party communication. As discussed earlier, political parties nowadays closely monitor the political debate on social media. Parties are well aware of issues raised by all their competitors on a platform, arguably limiting the influence of the connection between algorithms and party relevance or size for parties' behaviour in relation to issue engagement. Based on these considerations, I expect social media platforms to have some sort of ‘egalitarian effect’ on issue engagement, allowing smaller parties to respond more frequently to issues discussed by others.

H3: Issue engagement is less influenced by party size on social media platforms than in ‘traditional’ forms of party communication.

Fourth, social media can moderate how government participation affects issue engagement. In general, government parties often have to address issues and criticism raised by other parties (Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2010). In turn, government parties also act as an important source of information for other parties. Therefore, government participation arguably plays an important role when it comes to the dynamics of issue engagement. However, social media platforms could moderate this dynamic. The lack of gatekeeping on social media can result in a bigger influence of government participation on issue engagement compared to more ‘traditional’ forms of party communication, such as press releases. Research on negative campaigning shows that social media and its absence of moderators (e.g., journalists) is used by challengers to attack power‐holders or front‐runners in election campaigns and, in turn, leads to reactions from those attacked (Auter & Fine, Reference Auter and Fine2016; Gross & Johnson, Reference Gross and Johnson2016). This heightened focus on power‐holders on social media platforms may also travel to issue engagement. Government parties may therefore respond more frequently to issues raised by other parties on social media than in press releases, for example.

H4: Issue engagement by government parties is higher on social media platforms than in ‘traditional’ forms of party communication.

Case selection

To test the postulated hypotheses, I compare issue engagement in press releases and tweets from political parties in Austria, Germany and Switzerland between January 2019 and September 2021. Both press releases and the social media platform Twitter/X are widely used by parties to communicate their policies. Press releases are a well‐established ‘traditional’ communication channel and are used by parties to communicate with journalists and voters on a daily basis (e.g. Ennser‐Jedenastik et al., Reference Ennser‐Jedenastik, Haselmayer, Huber and Scharrer2022; Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, Elmelund‐Præstekær, Albæk, Vliegenthart and Vreese2012). Press releases are not subject to significant ‘institutional and resource constraints’ (Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2021) and their content can reach a large audience if picked up by journalists (Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, Elmelund‐Præstekær, Albæk, Vliegenthart and Vreese2012; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Haselmayer and Wagner2020). Therefore, press releases are an ideal tool to study ‘immediate dynamics of agenda setting’ (Gessler & Hunger, Reference Gessler and Hunger2021, p. 8), such as issue engagement between parties.

Similarly, the micro‐blogging platform Twitter/X has become a widely used tool for political actors to disseminate news and communicate policies to the general public on a permanent basis (e.g., Barberá et al., Reference Barberá, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019; Gilardi, Gessler, et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2022; Jungherr, Reference Jungherr2014; Kruikemeier, Reference Kruikemeier2014; Popa et al., Reference Popa, Fazekas, Braun and Leidecker‐Sandmann2020; Silva & Proksch, Reference Silva and Proksch2022). Tweets allow political actors to directly reach followers but also non‐followers through indirect exposure via retweets or shares, for example, (Popa et al., Reference Popa, Fazekas, Braun and Leidecker‐Sandmann2020; Silva & Proksch, Reference Silva and Proksch2022; Spierings & Jacobs, Reference Spierings and Jacobs2014). Twitter/X is the primary social media platform where political debates take place and political issues are discussed at the national level, while other platforms (e.g., Facebook) are rather used for campaign‐related purposes, such as the promotion of activities and events (Stier et al., Reference Stier, Bleier, Lietz and Strohmaier2018). This role as an important platform for political actors and debates has remained, even though some features have changed after Twitter was acquired by Elon Musk in October 2022 and later renamed to X.

This overview shows that press releases and tweets are ideal examples of ‘traditional’ and ‘newer’ forms of party communication channels, where a broad range of political issues are discussed. They share several important features: in contrast to other channels (e.g., manifestos, parliamentary speeches), press releases and tweets are comparatively flexible and unconstrained tools that allow parties to communicate policies on a daily (or hourly) basis and potentially reach a large audience. Thus, press releases are the one ‘traditional’ party communication channel that most closely resembles ‘newer’ tools such as Twitter/X. Therefore, a comparison of issue engagement between political parties in press releases and tweets is a well‐suited set‐up for the purpose of this study.

The selected countries represent typical Western European multi‐party systems covering a broad ideological and organisational spectrum. In all three countries, large centre‐left social democratic parties and centre‐right Christian democratic parties as well as Green, liberal and populist radical right parties are represented in parliament. Furthermore, the national parliament in Germany includes a left party, while smaller parties are regularly represented in the Austrian and Swiss parliaments.

However, Austria, Germany and Switzerland also show several differences that are potentially relevant for issue engagement. First, they differ in terms of electoral systems. While Austria and Switzerland use proportional systems, Germany uses a mixed system, with electoral districts and party lists playing different roles in each country. Electoral systems affect party competition, such as which positions parties take (e.g., Calvo & Hellwig, Reference Calvo and Hellwig2011; Cox, Reference Cox1990) or their issue emphasis (e.g., Kim, Reference Kim2020). Thus, differences in electoral systems may also affect issue engagement between parties. Furthermore, issue engagement in Switzerland is influenced by the rich tradition of direct democracy (Hänggli, Reference Hänggli2020). Second, unlike the other two countries, Switzerland usually relies on a special formula to automatically form a four‐party government consisting of the main parties (‘Zauberformel'). This significantly moderates government–opposition dynamics. Third, the selected countries show varying levels of professionalism and communication efforts. While Austria and Germany have highly professionalised parties and Members of Parliament (MPs), Switzerland has a semi‐professional parliament. This (potentially) affects the amount and frequency of published press releases and tweets. Higher levels of professionalism (e.g., campaign experts) within parties may lead to constant monitoring of political competitors and strategic responses to the issues raised by them, while less professionalised parties may not be able to handle such an effort. The selected countries also differ when it comes to the use of social media platforms. In Germany and Switzerland, Twitter/X is used by nearly every political party. This is less the case in Austria, where the FPÖ, for example, has only recently become more active on the platform.

Therefore, this case selection is well‐suited to study agenda setting between parties in typical Western European multi‐party systems and simultaneously allows to account for potential variation stemming from different political systems and cultures. In addition, the selected observation period (January 2019–September 2021) allows to control for potential influences of contextual factors, such as national election campaigns – Austria held national elections in September 2019, Germany in September 2021 and Switzerland in October 2019 – and direct democratic referendum campaigns in the case of Switzerland as well as the Covid‐19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

From a methodological point of view, the case selection also facilitates a monolingual computer‐based text analysis of exclusively German‐language texts. This should ensure higher reliability compared to multilingual text analysis, which can pose significant challenges (Chan & Sältzer, Reference Chan and Sältzer2020; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Baden, Stoltenberg, De Vries‐Kedem and Waldherr2022). Therefore, also in the Swiss case, only German‐language texts are included in the analysis, while French and Italian texts are excluded. Thus, the analysis for Switzerland mainly speaks to the 21 cantons (out of 26 cantons) in which German is the (co‐)official language.Footnote 2

Data

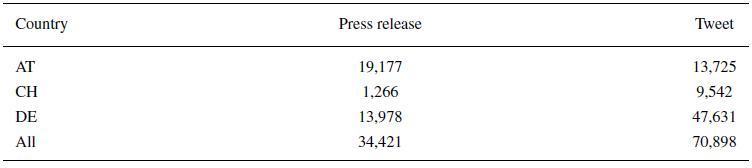

The complete text corpus consists of more than 105,000 individual party texts, which were collected in the context of a larger research project. The corpus contains more than 34,400 press releases and nearly 71,000 tweets from central party offices and parliamentary party groups (PPGs). Both central party offices and PPGs are important actors in the public communication profile of parties. In both cases, communication is mostly in the hands of the party leadership or the public relations team. This data selection allows to keep the actor constant across both press releases and tweets. In this study, I am interested in the potential differences in issue engagement between political actors across different types of communication channels. Thus, ensuring comparability between press releases and tweets is crucial. For this reason, I focus on the central party offices and PPGs and do not include tweets from individual politicians in the analysis. This is particularly relevant as social media allows individual politicians to play an important role, with their activity on social media related to a number of (personal) characteristics and effects on parties’ public profiles (e.g., Rauchfleisch & Metag, Reference Rauchfleisch and Metag2016; Silva & Proksch, Reference Silva and Proksch2022).

The press releases were collected by combining webscraping in the case of Austria and Germany and a dataset provided by Gilardi, Baumgartner, et al. (Reference Gilardi, Baumgartner, Dermont, Donnay, Gessler, Kubli, Leemann and Müller2022) for Switzerland. The tweets were collected through the Twitter Researcher API. In line with similar previous research (e.g., Barberá et al., Reference Barberá, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019; Gilardi, Gessler, et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2022), I analyse original tweets but exclude retweets and replies. Table 1 provides an overview of the corpus, while the evolution of the number of press releases and tweets per country and party over time is illustrated in Online Appendix A.1. Overall, the three countries differ with regard to the volume of party communication and the use of press releases and tweets. While Austrian and German parties use press releases similar extensively, Swiss parties publish comparatively few press releases. With regard to tweets, parties from Germany are the most active with a combined average of more than 47 tweets per day (compared to 14 press releases per day). Parties from Austria and Switzerland are also quite active on Twitter but to a much smaller extent than their German counterparts. While parties in Germany and Switzerland publish more tweets than press releases, Austrian parties seem to use both communication channels to a similar extent, averaging around 19 press releases and almost 14 tweets per day. In Switzerland, the parties publish a combined average of more than nine tweets, but only 1.2 press releases per day.

Table 1. Number of press releases and tweets between January 2019 and September 2021

Methods

Topic modelling

This paper aims to study whether and how issue engagement between parties is influenced by the use of social media platforms compared to more ‘traditional’ forms of communication (i.e., press releases). Therefore, it is crucial to first identify the issues discussed in the respective party texts. The large scale of the corpus requires a computer‐based approach. Several text‐as‐data tools for classifying political texts into topic categories have been developed and applied over the last decades (e.g., Blei et al., Reference Blei, Ng and Jordan2003; Wang, Reference Wang2023; Watanabe & Zhou, Reference Watanabe and Zhou2022). While some approaches are particularly useful when topic categories are known beforehand (e.g., supervised learning), others (e.g., unsupervised learning) have their strength in exploration (Grimmer & Stewart, Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013). Political parties discuss a broad spectrum of issues and the aim of this study is to identify engagement on particular issues. Thus, I am not primarily interested in broad policy areas but rather in the discussion of specific issues. Here, a more inductive approach allowing to extract previously unknown topics from texts is best suited to the task.

Similar to Barberá et al. (Reference Barberá, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019), I apply an unsupervised topic model, but opt for a structural topic model (STM) developed by Roberts et al. (Reference Roberts, Stewart and Airoldi2016) instead of Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) (Blei et al., Reference Blei, Ng and Jordan2003). For the purpose of this study, STM offers the advantage of allowing to specify covariates to account for potential topic variation stemming from country‐specific differences. To identify and extract issues from the party press releases and tweets, I apply STM in four steps.Footnote 3 First, I prepare the corpus for the text analysis. After removing URLs and text‐specific features (e.g., location/time stamps or abbreviations at the start of press releases), I apply common preprocessing steps by removing stop words, numbers and punctuation, converting the text to lowercase, stemming, and filtering out infrequent terms.

Second, I apply STM with country covariates to both the press releases and tweets together. To identify the optimal number of topics (k), I proceeded in two steps: first, I monitored semantic coherence, exclusivity, held‐out likelihood and the residuals for models with different numbers of topics (k = {20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, 160, 180, 200}). Based on the findings from this step, the optimal k seems to be located between 80 and 100. In the second step, I use this insight to apply models with k = {80, 85, 90, 95, 100} and conduct word and topic intrusion tests based on Chang et al. (Reference Chang, Gerrish, Wang, Boyd‐graber and Blei2009) to validate the models.Footnote 4 Overall, all tested models deliver good results. Ultimately, I choose k = 85 as the optimal number of topics because it delivers comparatively strong results both in the word and topic intrusion tests.

Third, I manually label the topics delivered by the topic model and assign political issues to them. Topic models provide the set number of topics (k) as clusters of words based on co‐occurrence. Thus, one needs to assign meaningful labels to each topic. I leverage the 10 highest probability words within each topic to fulfill this task. While some topics were fairly intuitive to label, others required extensive case‐specific knowledge. The latter was especially pronounced when names of political actors appeared in the highest probability words. This is due to text‐specific characteristics of press releases and tweets, where party leaders or policy‐speakers are regularly mentioned or quoted. Furthermore, several categories are not directly linked to specific policy areas but rather to legislative procedures, elections and events or are not clearly identifiable as political issues (i.e., ‘NA’ topics). Overall, I identify 37 unique political issues (e.g., ‘agriculture’, ‘education’, ‘migration') plus additional categories (e.g., ‘elections’, ‘event information’, ‘legislation and initiatives’, ‘thanks and wishes') in the press releases and tweets. An overview of the highest probability words per topic and the manually assigned issue labels is provided in Online Appendix A.3.

Finally, I assign the most likely political issue label to each individual text. Thus, each press release and tweet is assigned the most salient political issue. To account for text‐specific features of press releases and tweets and mitigate related potential problems in topic assignment, I performed some additional custom steps described in Online Appendix A.2. The resulting issue salience (in percent) that the structural topic model identified in the press releases and tweets, respectively, is reported in Online Appendix A.4.

Measuring issue engagement between parties

With the aid of statistical analysis, I aim to investigate whether and how issue engagement differs between press releases and tweets. The dependent variable is issue engagement between party dyads. As discussed earlier, I understand as ‘engagement’ if a party addresses an issue discussed by another party. Thus, I measure whether a party addresses a particular issue communicated by another party (‘source’) or not (‘no issue engagement’ = 0; ‘issue engagement’ = 1). This conceptualisation covers a broad range of dynamics, such as when two parties specifically discuss the same policy or event within an issue area, come into direct conflict on an issue, discuss the same issue but with different frames, positions or issue emphasis, or simply mention an issue at the same time. Examples of issue engagement between parties in press releases and tweets are provided in Online Appendix A.5. To allow a detailed and fine‐grained analysis of issue engagement dynamics between parties, I repeat this measure for each party dyad (party–source combination) within the respective country and for each issue on each date between 1 January 2019 and 26 September 2021. To compare issue engagement dynamics between the studied party communication channels, I measure issue engagement within press releases and tweets separately.

In principle, the data structure covers 110 party dyads

![]() $\times$ 37 political issues

$\times$ 37 political issues

![]() $\times$ 1000 days

$\times$ 1000 days

![]() $\times$ two text types. As some parties were not present in parliament during the complete time period or had not used press releases or tweets regularly during the studied time period, the respective entries were removed and the main dataset includes 6,212,744 observations.Footnote 5 Online Appendix A.6 provides a glimpse into the data structure and displays a sample of entries as contained in the main dataset. As this paper is interested in issue engagement, I focus on those observations where a party (‘source') discusses an issue and investigates whether another party addresses the issue as well or not in the respective communication channel. Therefore, the statistical analysis is based on 249,648 observations where an issue was discussed by a party (‘source') on a specific date.

$\times$ two text types. As some parties were not present in parliament during the complete time period or had not used press releases or tweets regularly during the studied time period, the respective entries were removed and the main dataset includes 6,212,744 observations.Footnote 5 Online Appendix A.6 provides a glimpse into the data structure and displays a sample of entries as contained in the main dataset. As this paper is interested in issue engagement, I focus on those observations where a party (‘source') discusses an issue and investigates whether another party addresses the issue as well or not in the respective communication channel. Therefore, the statistical analysis is based on 249,648 observations where an issue was discussed by a party (‘source') on a specific date.

For the dependent variable issue engagement, I calculate four different versions that cover different time frames for issue engagement. As discussed above, this article is based on a dynamic understanding of issue engagement between parties. Therefore, a fine‐grained measure is required. I expect parties to engage rather quickly on issues, as press releases and tweets allow parties to communicate permanently and respond immediately to other parties and events, that is, within 1 or 2 days. However, sometimes parties may also take a little bit longer to craft press releases or tweets to engage on an issue, such as on non‐working days at weekends or on public holidays. To account for such variation, I calculate different versions of the dependent variable, namely when a party addresses the same issue as another party (‘source') on the same day, within 2 days (i.e., same day and next day), within 3 days (i.e., same day and following 2 days) or within 4 days (i.e., same day and following 3 days).Footnote 6 Across the whole time period and across both press releases and tweets, I find 51,308 instances of issue engagement between two parties on the same day, 72,848 within 2 days, 86,155 within 3 days and 96,175 within 4 days.

To measure how the use of press releases and tweets moderates issue engagement, I include several independent variables. The first independent variable is tweet and indicates issue engagement in tweets compared to press releases. Furthermore, I use tweet in interaction terms to explore whether the use of Twitter moderates the influence of party‐level variables on issue engagement. To gather the required information for the party‐level variables, I mainly rely on the Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR) dataset (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al‐Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2024). The first party‐level variable is RILE difference and measures the ideological distance between the party under investigation and the source party. This measure is based on the Right‐left (RILE) score, which estimates the programmatic right‐left position of political parties (Laver & Budge, Reference Laver and Budge1992). The second party‐level variable captures the size of the party under investigation (party size) as the respective percentage of seats in parliament. Finally, I use a dummy variable to capture government and opposition roles of parties (party in government), where a value of 1 indicates government participation.

In order to statistically model issue engagement between the parties in press releases and tweets, I use logistic regression. I estimate four different models to capture issue engagement on the same day and within 2‐, 3‐ and 4‐day periods. To control for potential effects of election and direct democratic referendum campaigns, I include dummy variables representing 6‐week campaign periods ahead of national elections and referendums, respectively.Footnote 7 Furthermore, I include country and issue fixed effects to account for potential unobserved differences between these groups. Finally, I calculate clustered standard errors by party dyad‐issue (each party–source–issue combination) to address the clustering of observations in the data.

Results

The key question I address is whether social media may transform issue engagement between parties compared to more ‘traditional’ forms of political communication, such as press releases. Is issue engagement more or less likely on the social media platform Twitter compared to press releases? Do patterns of issue engagement between parties change?

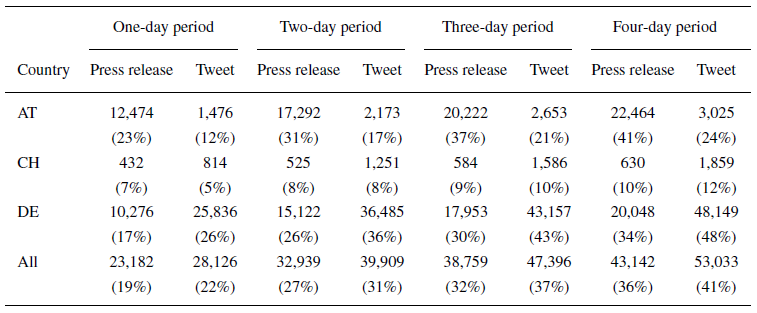

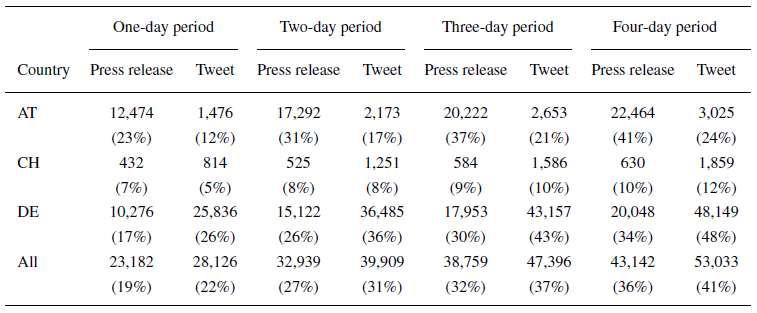

First, we can investigate how often political parties engage on issues communicated by other parties in press releases and tweets. Table 2 compares the absolute number of issue engagement occurrences in press releases and tweets. As explained earlier, I count as an occurrence of issue engagement when a party addresses an issue discussed by another party within the respective communication channel. The values are provided for issue engagement on the same day (1‐day period), within 2‐, 3‐ and 4‐day periods. Furthermore, the percentages provided in parentheses indicate the observed occurrences of issue engagement (i.e., instances when an issue is discussed by a party, that is, ‘source’, and addressed by another party) relative to the number of potential occurrences (i.e., all instances when an issue is discussed by a party, i.e. ‘source').

Table 2. Number of issue engagement occurrences across all party‐dyads per text type and country between January 2019 and September 2021. The percentages provided in parentheses indicate the observed occurrences of issue engagement relative to the number of potential occurrences

For all countries combined, I find more occurrences of issue engagement in tweets than in press releases, but considerable variation exists across countries. While Austria and Germany show similar levels of issue engagement in press releases, it is much rarer in Switzerland. This coincides with and probably results from the generally much smaller communication volume of Swiss parties. The most glaring outlier, however, is the level of issue engagement between Austrian parties on Twitter. In contrast to the overall trend, the results show a much lower number of occurrences in tweets than in press releases. As discussed earlier, Twitter is used less extensively by political actors in Austria than in Germany or Switzerland. For example, the FPÖ – one of Austria's most relevant parties – has not used Twitter regularly during the studied time period. This unequal use of press releases and tweets in Austria may therefore drive this – at first sight rather surprising – observation.

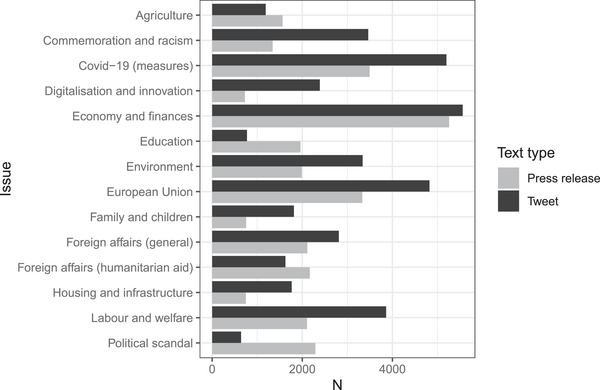

Figure 1 provides further descriptive results by comparing the number of issue engagement occurrences in press releases and tweets per issue. More precisely, Figure 1 is an overview of the top 10 issues with the highest level of issue engagement in absolute numbers (within a 4‐day period) for the two respective party communication channels. We can observe similar levels of issue engagement for several issues (e.g., ‘agriculture’, ‘economy and finances'), but some differences exist. While issue engagement on ‘commemoration and racism’ (e.g., mentions of remembrance days, discussion of antisemitism) and ‘digitalisation and innovation’ appears to be more frequent on Twitter, it is more pronounced in press releases on ‘education’ or ‘political scandal’, for example.

Figure 1. Top 10 issues with the highest level of issue engagement (4‐day period) in press releases and tweets between January 2019 and September 2021.

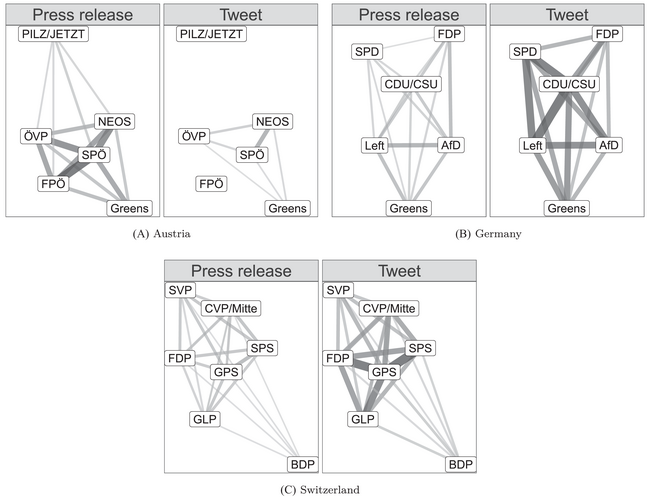

Besides the (issue‐wise) amount of issue engagement, the dyadic structure of the dataset also allows to investigate relationships between individual parties. Figure 2 provides the issue engagement networks between the parties both in press releases and tweets per country. The network nodes represent the parties, and the strength of the edges represents the (undirected) frequency of issue engagement between each party dyad.Footnote 8 Overall, the networks for Germany and Switzerland indicate higher levels of issue engagement in tweets. Furthermore, differences between the party dyads appear to exist. Some observations hint at a potential influence of ideological distance on issue engagement as some ideologically similar parties appear to have stronger ties, such as Greens‐Left and SPD‐Left in Germany, but this is not the case for all. In the case of Austria, the network for tweets appears to be less dense. As mentioned earlier, this descriptive finding is probably due to the fact that Twitter is a less important communication channel in Austria, which is also reflected in the lack of Twitter use by the FPÖ and PILZ/JETZT.

Figure 2. Issue engagement (4‐day period) network between parties in press releases and tweets between January 2019 and September 2021.

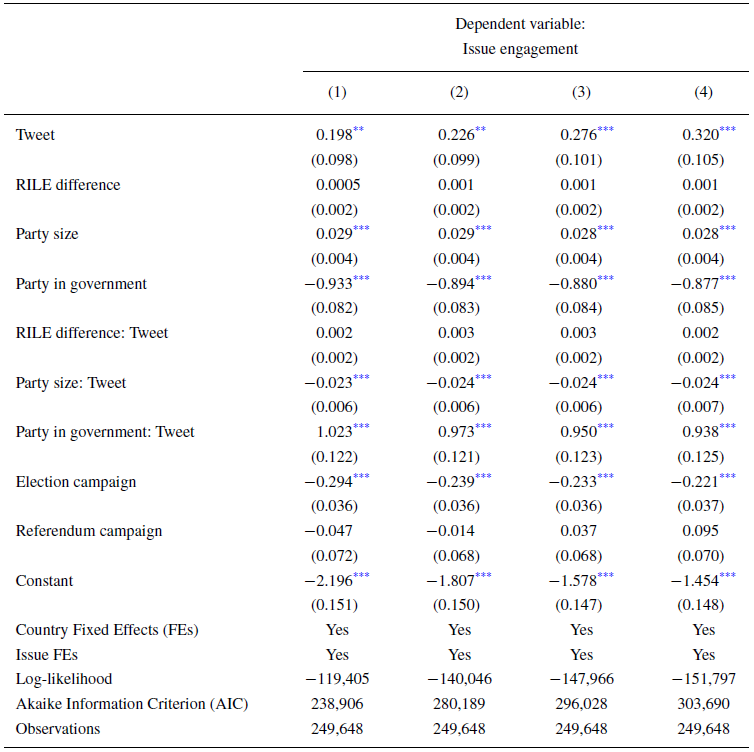

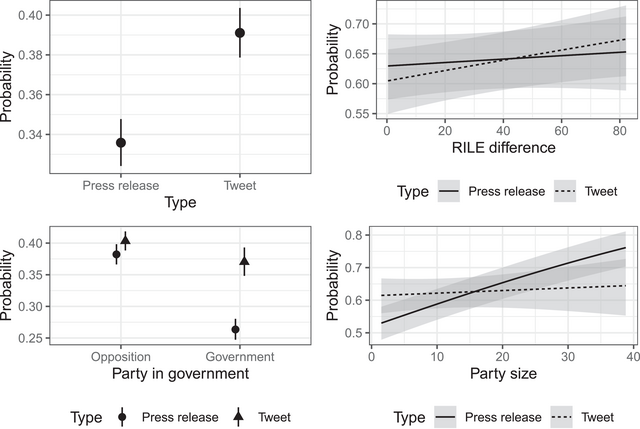

In the next step, I use statistical models to dive deeper into the dynamics of issue engagement in press releases and tweets. Table 3 provides the results of logistic regression models investigating how Twitter influences issue engagement between parties and the (potential) interaction effects with ideological distance, party size and government participation. Issue engagement in press releases functions as the reference category in the models. The first model captures issue engagement by one party (party) as addressing an issue discussed by another party (source) on the same day (1‐day period), the second model captures issue engagement within a 2‐day period, the third model within a 3‐day period and the fourth model within a 4‐day period. The fourth model also serves as the basis for marginal effects plots displayed in Figure 3.

Table 3. Regression models with moderating factors for issue engagement between parties

Note: Standard errors are clustered by party dyad‐issue.

*p

![]() $<$0.1; **p

$<$0.1; **p

![]() $<$0.05; ***p

$<$0.05; ***p

![]() $<$0.01.

$<$0.01.

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities for issue engagement (4‐day period) in press releases and tweets. The plots on the left show marginal predictions (i.e., predictions computed on the original data, but averaged by subgroups) based on categorical variables; the plots on the right require conditional predictions (i.e., predictions computed on a substantively meaningful grid of predictor values) due to the inclusion of continuous variables.

Overall, the results are consistent across the four model specifications and show that issue engagement between parties is indeed more likely in tweets than in more ‘traditional’ forms of political communication (i.e., press releases). According to model 1, the coefficient for issue engagement in tweets is 0.198, meaning an increase in the odds for issue engagement by a factor of 1.219. This evidence is further supported by the fact that it is solely based on the analysis of original tweets. One can imagine that retweets and replies encourage issue engagement even more and including them in the analysis would probably further increase the magnitude of the effect. Overall, this finding supports hypothesis H1a, which postulates that social media offers political parties the opportunity to discuss and engage more actively with other parties on issues. The competing hypothesis H1b, in turn, needs to be rejected.

When taking a closer look at the influence of the different party‐level factors, it becomes clear that Twitter does not only affect the level of issue engagement but also moderates its nature.Footnote 9 First, the variable party size reflects whether large parties are more likely to engage on issues communicated by other parties. In the reference category (i.e., press releases), the models show a positive and statistically significant effect on party size. However, there is a negative interaction effect between party size and tweet. Thus, the effect is significantly smaller on Twitter. Hence, the size of a party plays a less influential role with regard to issue engagement on Twitter than in press releases, confirming hypothesis H3. This is in line with the argument that social media communication requires less resources and allows smaller parties to participate more actively in the debate.

Second, the variable party in government indicates a potential effect resulting from a party's position in government. The models show a statistically significant negative effect for the variable in the reference category, indicating that government parties are less likely to engage with other parties on issues in press releases. This runs counter to the argument that government parties have to engage on a broader set of issues than opposition parties, although evidence for such behaviour is mixed anyway (see Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2010; Meyer and Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2016). A possible explanation for the pattern found here also lies in the dataset, since I focus on press releases from party offices and parliamentary party groups. Besides their own communication tools, government parties also routinely use government tools, such as press releases from ministries. This circumstance may affect the results in the reference category (i.e., press releases). On Twitter, the likelihood that government parties engage with other parties on issues is clearly higher, as indicated by the interaction term between party in government and tweet. While government parties perform significantly less issue engagement than opposition parties in press releases, they show similar levels to opposition parties in tweets. This finding is in line with the argument that social media can heighten the focus on power‐holders and increase their role in issue engagement compared to more ‘traditional’ forms of political communication, confirming hypothesis H4.

In contrast to these findings, Twitter does not appear to have an effect on the influence of ideological distance on issue engagement according to the analysis presented here. The variable RILE difference represents the ideological distance between two parties. The models indicate no effect of ideological distance on issue engagement in press releases. This contradicts previous findings by Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen (Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015) and Meyer and Wagner (Reference Meyer and Wagner2016), which show that issue engagement is higher between ideologically similar parties. Here, the picture also does not change when we turn our attention to the interaction term between RILE difference and tweet. While the coefficients point to a slightly positive relationship, the effect is rather weak and not statistically significant. Thus, I do not find support for an ‘echo chamber’ effect in issue engagement between parties on Twitter and H2 needs to be rejected. The hypothesis was based on the argument that social media primarily encourages discussions among ideological peers due to algorithmic content selection. However, this does not seem to apply to political parties. As discussed earlier, political parties closely monitor the political debate, particularly on social media, and are well informed about their competitors’ communication – regardless of ideological position. This is a potential explanation for the limited role of algorithmic content selection with regard to issue engagement between ideologically distant parties. However, platform design and algorithmic content selection may actually play an important role with regard to voters’ exposure to party communication and their perceptions of party competition.

Furthermore, the results also shed light on how contextual factors, such as election or referendum campaigns, affect issue engagement. The regression models show a lower level of issue engagement during election campaigns. This is in line with the classic argument that parties aim to stick to their main message during election campaigns (e.g., Norris et al., Reference Norris, Curtice, Sanders, Scammell and Semetko1999). However, this seems to be much more pronounced in press releases than in tweets (see Online Appendix A.8). In contrast, no statistically significant effect of referendum campaigns on issue engagement is found. Thus, referendum campaigns do not seem to have the same negative effect on issue engagement as national election campaigns, but they also do not seem to drive issue engagement on a broad scale. A potential explanation lies in the fact that although parties may engage more on a particular issue subject to the referendum, this behaviour may not travel to other issues. However, the broader implications of differences in political cultures, such as the importance of direct democracy, cannot be investigated in detail here and should be subject to future research.

To sum up, the results show that political parties are more likely to perform issue engagement in tweets than in press releases. Furthermore, the social media platform Twitter appears to moderate the influence of party size and government participation on issue engagement but not so much of ideological distance. While party size is less important on Twitter than in press releases, government participation plays a larger role. These results remain largely stable in individual country models, but there are also some differences (see Online Appendix A.9). In principle, the different types of electoral and party systems do not seem to have systematic effects on the findings. Across all cases, the level and nature of issue engagement differ in a similar fashion between press releases and tweets. However, two differences exist. First, the heightened likelihood for issue engagement on Twitter is only apparent after 2 days in the case of Switzerland. Thus, Swiss parties seem to take longer to respond to issues addressed by other parties than parties in Austria and Germany, also on Twitter. Here, the semi‐professional nature of Swiss politics, which leads to a comparatively low volume of political communication, may provide a suitable explanation. Second, the likelihood for issue engagement by government parties does not increase on Twitter in the case of Austria and Switzerland. In contrast to the overall findings, I even find a negative effect for Austria and no statistically significant effect for Switzerland. While the latter finding is not surprising due to the absence of a classic government–opposition dynamic in Switzerland (see discussion in case selection), the former requires more explanation. As pointed out earlier, the finding for Austria could be due to the relatively small role of Twitter in the Austrian political system and particularly for one of the largest parties, the FPÖ, which was also part of the government for some parts of the observation period. Besides these small country differences, the regression models are quite robust to checks following a jackknife logic controlling for a potential influence of individual political issues (see Online Appendix A.10) and to checks controlling for potential effects resulting from the Covid‐19 pandemic (see Online Appendix A.11).

Discussion and conclusion

Contemporary democracies are shaped by a plethora of communication channels with political actors using both ‘older’ and ‘newer’ forms simultaneously. To what extent and how this transforms political competition and public discourse is subject to a broad and ongoing debate. In this article, I contribute to this debate by investigating how the nature of issue engagement among political parties differs between ‘traditional’ forms of political communication (i.e., press releases) and social media platforms (i.e., Twitter). Issue engagement captures the extent to which political parties talk about the same issues and the related streams of influence between them (i.e., agenda setting). Issue engagement thereby affects public discourse, policy‐making and how voters learn about and perceive parties and political processes.

To investigate whether and how issue engagement differs between different communication channels, I have analysed press releases and tweets from parties in Austria, Germany and Switzerland (January 2019–September 2021). Based on the application of an STM, I statistically modelled patterns of issue engagement in the press releases and tweets with logistic regression.

The empirical analysis shows a higher likelihood for issue engagement in tweets than in press releases. The results provide strong evidence for this effect, although I only include original tweets in the analysis and exclude retweets or replies, which may further drive issue engagement between parties. Besides the extent, the patterns of issue engagement differ between these two forms of political communication as well. First, social media can reduce the influence of party size on issue engagement. I argue that social media posts, such as tweets, often require less resources than publishing press releases and therefore allow smaller parties to engage on a broader set of issues. Second, the results show that government parties engage with other parties on issues more frequently in tweets than in press releases. A fitting explanation for this pattern lies in an arguably comparatively confrontational communication style – particularly between power‐holders and challengers ‐ on social media. Finally, I do not find evidence for a heightened role of ideological distance with regard to issue engagement on Twitter. Thus, potential ‘echo chambers’ on the platform do not appear to affect issue engagement between political parties.

These findings have important (normative) implications for various democratic processes. First, the example of press releases and tweets shows that the use of ‘newer’ and ‘older’ forms of political communication leads to the simultaneous co‐existence of different patterns of party competition and political debate. This has several implications for media coverage and voters’ perceptions. While journalists have for a long time relied on press releases from parties to gain information about current affairs, they nowadays also increasingly monitor social media for reporting (e.g., Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2017; Lecheler & Kruikemeier, Reference Lecheler and Kruikemeier2016). Thus, one might expect that the changing dynamics of issue engagement on Twitter/X will also be transferred to news reporting. Furthermore, social media allows political parties to reach voters directly. Issue engagement may therefore present itself in different ways, depending on whether voters observe it directly on social media or through media coverage. Depending on news habits and social media use, this can potentially lead to different perceptions of democratic processes and parties among different groups of voters, particularly since political communication is increasingly fragmented along generations or educational backgrounds, for example. Such potential heterogeneous effects resulting from different patterns of issue engagement – that is, how issue engagement in ‘newer’ and ‘older’ forms of political communication affects media coverage and voters’ perceptions – are therefore a relevant avenue for future research.

Second, the paper adds evidence to some common arguments about the potential positive or negative effects of social media on democracy. In contrast to some pessimistic views, the social media platform Twitter does not appear to stop parties – particularly ideologically different parties – from talking about the same issues. Furthermore, it seems to reduce the barriers for smaller parties to participate in debates. Thus, I indeed find evidence for some sort of ‘egalitarian effect’ of Twitter on issue engagement between political parties. However, at the same time, it also seems to increase the role of government parties. Again, future research should look into how this affects media coverage and voters’ perceptions of political processes.

These insights advance our understanding of several important features of contemporary political communication, but the article also has limitations. First, the article does not address the depth, quality and style of issue engagement in different types of party communication. This limitation is caused by the conceptualisation and measurement of issue engagement. While the understanding of issue engagement in this article and the associated measurement allows to investigate the broad dynamics of issue engagement, it does not enable a fine‐grained analysis of how parties engage with each other on issues, that is, whether they engage in substantive conversations about a particular issue, for example, or merely mention it or attack each other based on competence. Here, one can expect several differences between various party communication channels. Although tweets, for example, offer the possibility to share links to external websites or allow to create threads, they are usually still much shorter and less detailed than press releases. This can therefore constrain the depth at which a particular issue is discussed. Furthermore, the quality and style of issue engagement may be negatively influenced by the use of social media. For example, previous studies on negative campaigning (e.g., Antypas et al., Reference Antypas, Preece and Camacho‐Collados2023; Klinger et al., Reference Klinger, Koc‐Michalska and Russmann2023) point to a confrontational style of discussing issues on social media. Exactly such confrontational or emotional messages may attract attention and issue engagement on social media platforms, having several potential negative implications for public discourse or voters’ perceptions of and satisfaction with democratic processes. Thus, further research that investigates the quality and style of issue engagement in different communication channels and the associated effects on democracies is needed.

Second, this article mainly focuses on the influence of party‐level factors on issue engagement, such as the ideological distance between parties, party size or government participation. Further factors were outside the scope of this study but would certainly lend themselves to fruitful analyses. Future research, for example, could dive deeper into the influence of parties’ organisational features. This article has relied on the number of seats in parliament as a proxy for party size, but it could be worthwhile to look into other related aspects, such as membership, number of staff or campaign expenditures, and their influence on issue engagement. Similarly, investigating the influence of internal organisational structures, such as leadership or activist orientation, is another potential avenue for future research. Furthermore, our understanding of party competition and issue engagement in ‘older’ and ‘newer’ forms of political communication would certainly benefit from a closer inspection of issue attributes and contextual factors. In relation to issue attributes, previous research has shown that voters’ attention to issues drives issue engagement between parties (e.g., Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Hennessy, Kifer and Parkin2010). Social media platforms allow political actors to monitor issue attention on the respective platform even more directly. Does this feature of social media platforms further spur engagement on issues, which are important to voters, or at least to the users of a platform? And are there issues on which all parties tend to engage regardless of ideological orientation, while engagement on other issues is more selective and depends on ideology or issue ownership? In relation to contextual factors, the connection between institutional features and political cultures, such as the type of electoral and party system or the role of direct democracy, and the characteristics of social media also warrants further research. Does social media promote or limit broad societal debates on certain issues in the context of election or referendum campaigns? Are there differences between types of electoral systems and political cultures?

Third, another aspect not covered in this article is how different channels interact when it comes to issue engagement and agenda setting between parties. The analysis presented here treats issue engagement in press releases and tweets separately. Therefore, it does neglect whether parties address issues in press releases that were first raised by another party on Twitter or vice versa. Thus, while the results of this article offer several valuable insights into issue engagement within the two studied communication channels, it may also be fruitful to investigate how channels interact and the diffusion of political issues across them.

Finally, social media is a constantly growing field (e.g., Twitter/X, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok). Here, investigating how issue engagement and party competition are affected by different platform logics and algorithms is another important avenue for future research. While Twitter/X is a major social media platform where current political affairs are discussed, other platforms (e.g., Facebook) are better suited for campaign‐related purposes (Stier et al., 2018). Thus, parties may use the plethora of social media platforms differently. For example, there may be significantly less issue engagement between parties on more campaign‐oriented platforms such as Facebook, Instagram or TikTok than on the micro‐blogging platform Twitter/X, which more strongly facilitates political debates at the national level. Similarly, parties may address and engage on different issues depending on the audience that can be reached through a platform. Furthermore, different platform logics and algorithms may influence the extent to which voters are exposed to content from various competing parties or – depending on who they follow, for example – are mainly shown content from certain parties. Thus, issue engagement between parties and how it is perceived by voters may play out differently depending on the social media platform.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and guidance. I am also very grateful to Heiko Giebler, Pola Lehmann, Elizabeth Nugent, Daniel Saldivia Gonzatti, as well as all participants of the Center for Civil Society Research colloquium at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center for helpful comments and feedback. Additionally, the paper was greatly improved by feedback from participants of a workshop at the Berlin Graduate School of Social Sciences.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IDCDHS.

Ivanusch, C. (2024). Replication data for: Where do parties interact? Issue engagement in press releases and tweets. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IDCDHS , Harvard Dataverse, V1.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure 1: Evolution of the number of press releases and tweets published by parties between January 2019 and September 2021.

Figure 2: Evolution of the number of press releases and tweets published by each Austrian party between January 2019 and September 2021.

Figure 3: Evolution of the number of press releases and tweets published by each German party between January 2019 and September 2021.

Figure 4: Evolution of the number of press releases and tweets published by each Swiss party between January 2019 and September 2021.

Figure 5: Development of semantic coherence, exclusivity, held‐out likelihood and residuals for different numbers of topics (k) of structural topic model (STM).

Table 1: Mean model precision from word intrusion test and mean topic log odds (TLO) from topic intrusion tests for the applied structural topic models (STM)

Table 2: Top‐10 words per topic provided by the Structural Topic Model with manually assigned topic labels

Table 3: Comparison of issue salience (in percent) in press releases and tweets between January 2019 and September 2021.

Table 4: Examples for issue engagement between parties in press releases and tweets.

Table 5: Overview of structure of main data set (sample).

Figure 6: Directed issue engagement network graph for Austrian parties in press releases and tweets (four‐day period) between January 2019 and September 2021.

Figure 7: Directed issue engagement network graph for German parties in press releases and tweets (four‐day period) between January 2019 and September 2021

Figure 8: Directed issue engagement network graph for Swiss parties in press releases and tweets (four‐day period) between January 2019 and September 2021.

Table 6: Regression models (one‐day period) with moderating factors on issue engagement between parties for press releases and tweets separately.

Table 7: Regression models (two‐day period) with moderating factors on issue engagement between parties for press releases and tweets separately

Table 8: Regression models (three‐day period) with moderating factors on issue engagement between parties for press releases and tweets separately.

Table 9: Regression models (four‐day period) with moderating factors on issue engagement between parties for press releases and tweets separately.

Table 10: Regression models (one‐day period) with moderating factors on issue engagement between parties per country

Table 11: Regression models (two‐day period) with moderating factors on issue engagement between parties per country.

Table 12: Regression models (three‐day period) with moderating factors on issue engagement between parties per country.

Table 13: Regression models (four‐day period) with moderating factors on issue engagement between parties per country.

Table 14: Summary statistics of coefficients for regression models (four‐day period) following jackknife logic.

Figure 9: Coefficients for the influence of tweets on issue engagement based on regression models (four‐day period) following jackknife logic.

Figure 10: Coefficients for the influence of ideological distance on issue engagement in press releases based on regression models (four‐day period) following jackknife logic.

Figure 11: Coefficients for the influence of party size on issue engagement in press releases based on regression models (four‐day period) following jackknife logic.

Figure 12: Coefficients for the influence of government participation on issue engagement in press releases based on regression models (four‐day period) following jackknife logic.

Figure 13: Coefficients for the interaction effect between ideological distance and tweets on issue engagement based on regression models (four‐day period) following jackknife logic.

Figure 14: Coefficients for the interaction effect between party size and tweets on issue engagement based on regression models (four‐day period) following jackknife logic

Figure 15: Coefficients for the interaction effect between government participation and tweets on issue engagement based on regression models (four‐day period) following jackknife logic.

Table 15: Regression models (four‐day period) with for moderating factors on issue engagement across all issues, non‐Covid‐19‐related issues and Covid‐19‐related issues.