Introduction

Antibiotic use is a major driver for antimicrobial resistance (AMR), Reference Bell, Schellevis and Stobberingh1 widely recognized as a major global health threat. 2 General practitioners (GPs) prescribe the highest quantity of antibiotics. 3 Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are the most common indication for antibiotics, both in daytime and out-of-hours (OOH) settings. Reference McCloskey, Malabar and McCabe4,Reference Lindberg, Gjelstad and Foshaug5 Studies indicate high levels (between 20% and 50%) of unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions for RTIs in primary care, Reference Hersh, King and Shapiro6 which contribute to the development of bacterial resistance. Reference Costelloe, Metcalfe and Lovering7 Evidence suggests that antibiotic prescriptions for RTIs can be safely reduced in primary care. Reference Stimson, McKeever and Agnew8

Antimicrobial stewardship efforts to reduce antibiotic use for self-limiting or viral RTIs and encourage self-management of infections need to address both prescriber and patient behavior. 9 GPs report pressure from patients to prescribe antibiotics. Reference Cole10,Reference Reali, Kwang and Cho11 One study reports that 45% of GPs sometimes prescribe antibiotics for a viral infection due to perceived patient demand rather than clinical need. Reference Cole10 Other contributing factors include high GP workload, reducing opportunity to explain why antibiotics are not needed and fear of adverse outcomes when withholding antibiotics. Reference Reali, Kwang and Cho11,Reference Lundkvist, Akerlind and Borgquist12 In the OOH setting, lack of follow up and familiarity with patients, lack of access to the patient medical history and investigations, and time pressure may lower the threshold for prescribing an antibiotic. Reference Williams, Halls and Tonkin-Crine13

An evidence-based approach to address unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics in general practice is the use of patient leaflets by GPs during RTI consultations, Reference de Bont and Alink14–Reference Hunter and Owen16 offering the opportunity to educate patients on responsible antibiotic use and promote self-management of infections as an alternative. It supports GP and patient communication and shared decision-making and is a tangible resource to give a patient instead of a prescription. Reference Bunten, Hawking and McNulty17 Reductions in antibiotic use of 21%–24% have been reported in two randomized control trials with the use of a patient leaflet during RTI consultations. Reference Francis, Butler and Hood18,Reference Macfarlane, Holmes and Gard19 Use of leaflets could reduce re-consultations Reference Macfarlane, Holmes and Gard19 and GP workload by empowering patient. Reference Jones, Hawking and Owens20

The TARGET (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly: Guidance, Education, Tools) toolkit is an evidence-based UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) initiative designed to address primary care clinicians’ and patients’ behaviors around responsible antibiotic use. 21 One of the most popular toolkit resources is the Treating Your RTI leaflet, intended to be used by GPs during consultations with patients presenting with self-limiting RTIs to support communication and education around self-management of RTIs. 3 The TARGET leaflet was developed with extensive stakeholder consultation, is thoroughly evaluated Reference Bunten, Hawking and McNulty17,Reference Jones, Hawking and Owens20,Reference Eley, Lecky and Hayes22,Reference McNulty, Hawking and Lecky23 and has been awarded with a Crystal Mark for use of plain English. 21 It provides information on likely illness duration, self-care, cautions with antibiotic use and red flags for when to seek further help. It also provides the clinician with the opportunity to use a back-up or delayed prescription, a strategy shown to reduce antibiotic use. Reference Spurling, Del Mar and Dooley24

Key objectives of Ireland’s national AMR action plan are to increase awareness amongst the public of prudent antibiotic use and utilize behavioral change approaches to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use. 25 At the time of this study, no patient information leaflets were available in Ireland for GPs to use during consultations with patients presenting with self-limiting RTIs to support a no-antibiotic or a delayed antibiotic prescribing strategy.

This study evaluates the feasibility and acceptability of the use of the Treat Your RTI (TY-RTI) leaflet, adapted from the TARGET toolkit leaflet, in Irish daytime general practice and OOH GP services. The findings from this study will inform wider implementation of the use of the TY-RTI leaflet in general practice in Ireland and other countries considering developing similar resources.

Methods

A single-arm mixed-methods feasibility study was conducted to assess the feasibility of the use of a TY-RTI leaflet in general practice and OOH settings. It is reported in accordance with the Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist. Reference Hoffmann, Glasziou and Boutron26 (TIDieR checklist in supplementary data).

Development of the leaflet

Following permission from UKHSA TARGET leads, the TARGET Treating Your RTI leaflet was adapted to align with Irish guidance, ensuring legibility and understandability in the Irish context. This was conducted with a stakeholder consultation group including national GP leads for AMR and sepsis, an antimicrobial pharmacist, a health service communications manager, and a patient representative. After modification the version of the TY-RTI leaflet used in the study was agreed by the research team (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The leaflet used in the Treat Your respiratory infection leaflet feasibility study, Ireland, 2024 (A5 folded paper copy).

The term “back-up antibiotic” was used in the leaflet rather than “delayed antibiotic” as previous research has shown this term is more understandable for patients than “delayed antibiotic.” Reference Bunten, Hawking and McNulty17

Study design, setting, and participants

GPs were recruited for the study through professional networks of the researchers to obtain a purposive sample of GPs working in daytime practice in small/large and urban/rural practices and from one regional OOH GP service.

An introductory meeting was held with each GP individually to explain the study and provide instructions, study participant information leaflets, GP and patient questionnaires and hard copies of the TY-RTI leaflet. GPs were advised to use the leaflet for in-person consultations with patients and parents of children aged 3 months and over presenting with RTI symptoms where the GP determines there is no need for an antibiotic, or they prescribe a delayed antibiotic. The GP was free to choose for which patient consultations they used the leaflet. The study ran from January to June 2024.

Allowing for projected loss of follow-up of completed patient questionnaires, the aim was for at least 50 completed patient questionnaires and for a total of 200 GP consultations. GPs were each asked to use the leaflet approximately 30 times to ensure familiarity with the leaflet and use in a variety of RTI presentations and patients. This sample size was proposed to provide a sufficient and meaningful amount of data to inform the results and was considered a manageable request for participating GPs in terms of data collection. As some GPs commenced the study in springtime, there were fewer RTI presentations, and not all GPs were able to use the leaflet in 30 consultations within the study time frame. The study closed when 200 GP consultations were recorded. No compensation was provided to GPs or patients for participation. Written consent to participate in the study was obtained from each GP. Patients provided informed consent to participate. Ireland has a mixed public/private GP care provision, with approximately 40% of the population eligible for free GP care through a means-tested general medical card (GMS) card or free GP visit card. 27 GPs are self-employed and are reimbursed a set fee per patient per annum from the state irrespective of frequency of attendance. The remainder of the population pay for the consultation. OOHs doctors are accessed through OOH doctor co-operatives where many daytime GPs work shifts.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Irish College of General Practitioners Research Ethics Committee (2023–1842).

Data collection and analysis

GPs completed a questionnaire for each consultation when the leaflet was used, outlining patient demographics, consultation setting (daytime practice/OOH), working diagnosis, whether the patient requested an antibiotic, and whether an antibiotic was prescribed (immediate or delayed). GPs provided feedback on the use of the leaflet in the questionnaire through questions based on a 5-point Likert scale, with an option for free-text comments.

At the end of the consultation, the GP invited patients (or parents if the patient was under 18 years old) to complete a patient questionnaire developed for this study as soon as possible after they left the consultation. Patient questionnaires gathered details on patient demographics and their feedback on the leaflet through questions based on a 5-point Likert scale, with an option for free-text comments.

Both patient and GP questionnaires were available to complete on paper copies or electronically via MS Forms available via a QR code. All data were analyzed descriptively in Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365 MSO (Version 2504 Build 16.0.18730.20226) 64-bit. All free-text comments were reviewed and summarized.

Results

Participant demographics and consultation characteristics

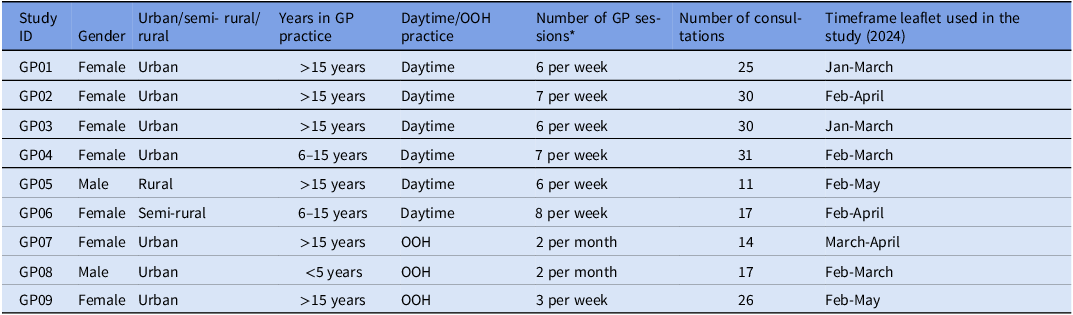

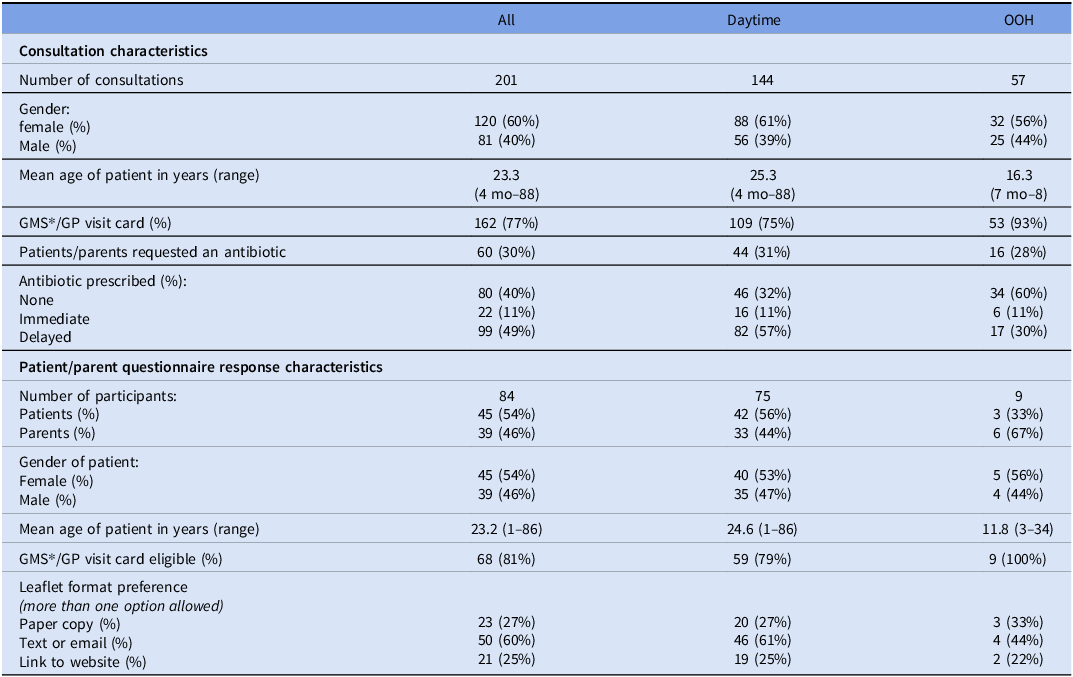

The leaflet was used by nine GPs (six in daytime practice and three in OOH doctor’s service), with 201 RTI consultations recorded. Feedback was provided by GPs on each consultation (n = 201) and patient questionnaires were submitted by 84 patients/parents (41.8%) with whom the leaflet was used. Table 1 summarizes the GP characteristics.

Table 1. GP participant characteristics for the Treat Your respiratory infection leaflet feasibility study, Ireland, 2024

* One session = 3 hours patient consultations.

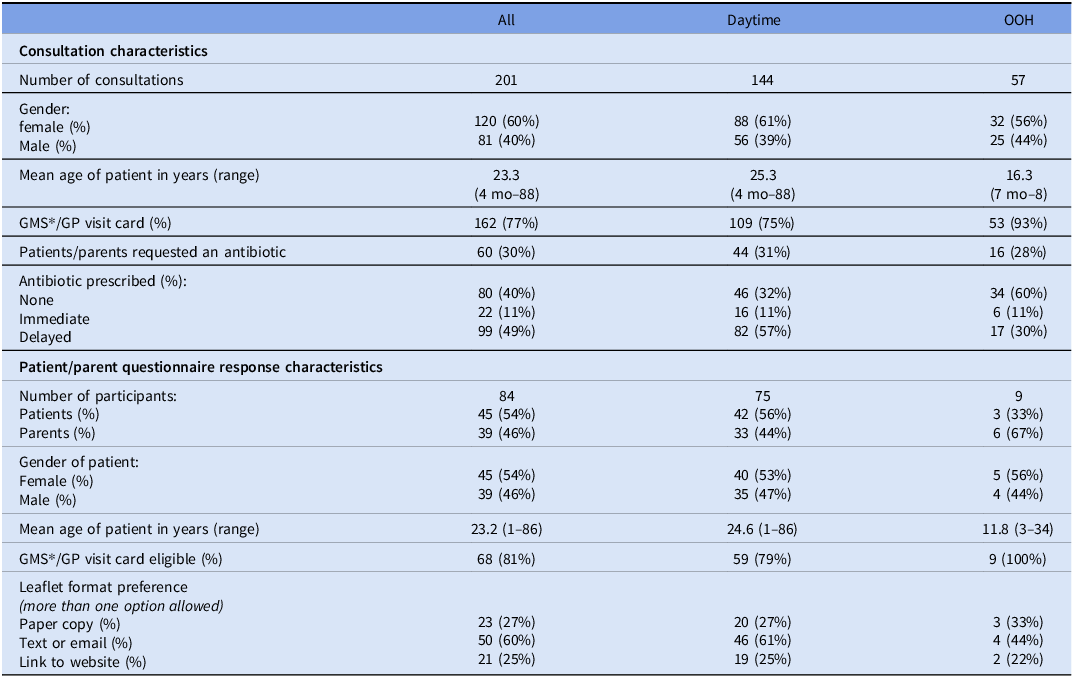

Of the 201 consultations, 144 (72%) took place in daytime practice and 57 (28%) in OOH sessions (Table 2). The overall mean patient age was 23.3 years (16.3 yr for OOH consultations; 25.3 yr for daytime consultations). The age range of patients was 4 months–88 years, and the leaflet was most commonly used in 0–4-year-olds (31% 62/201 patients).

Table 2. Summary of consultation and patient/parent questionnaire response characteristics for the Treat Your respiratory infection leaflet feasibility study, Ireland, 2024

* GMS = General Medical Scheme. This is the name of the state scheme that provides holders of a GMS card or a GP visit card with general practice care that is free at the point of access.

The most common indication presentation was the common cold (40%, 81/201 consultations), followed by acute bronchitis (12%, 24/201), tonsilitis (10%, 21/201), sinusitis (9%, 18/201), and otitis media (8%, 17/201).

Overall, 40% (80/201) of consultations did not result in an antibiotic prescription, and 49% (99/201) of consultations resulted in a delayed antibiotic prescription. Although GPs were asked to use the leaflet when they were not prescribing antibiotics or for delayed antibiotics, six of the nine GPs used it occasionally when prescribing immediate antibiotics, and 11% (22/201) of consultations resulted in an immediate antibiotic prescription.

GPs recorded that 30% (60/201) of patients requested an antibiotic during the consultation, and of these, 75% (45/60) were prescribed a delayed or immediate antibiotic prescription, higher than 63% (76/121) of patients who did not request an antibiotic being prescribed one.

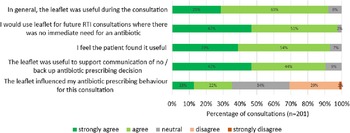

GP views on the leaflet

GPs reported all the sections of the leaflet to be useful in over 83% (168/201) of the consultations. In particular, for over 94% (189/201) consultations, GPs reported the “when to seek help,” “self-care” and “expected duration of symptoms” sections useful. For most consultations (91%,182/201), GPs reported that the leaflet was useful to support communication with the patient and that they would use the leaflet for future RTI consultations. For 35% (71/201) consultations, GPs reported that using the leaflet influenced their antibiotic prescribing behavior (Figure 2). For 53% (107/201) of consultations, GPs stated there was no significant impact on consultation duration, for 41% (82/201) consultations, they stated it shortened the consultation and for 6% (12/201) consultations, they stated it lengthened the consultation.

Figure 2. GPs views on using the leaflet in the Treat your respiratory infection leaflet feasibility study, Ireland, 2024 (n = 201).

Additional free-text comments indicated GPs were positive about the leaflet, that the leaflet helped to “break the ice,” build rapport with patients, support shared decision-making, alleviate parental anxiety and dispel misconceptions about infections and the need for antibiotics.

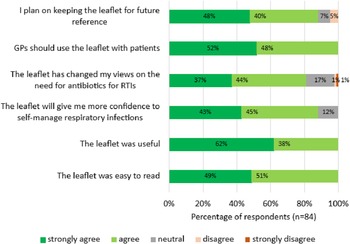

Patient/parent views on the leaflet

Of the 201 consultations, 84 (42%) patients/parents completed the questionnaire (Table 2). Overall, patients/parents responded positively to the leaflet (Figure 3). All respondents found the leaflet easy to read and useful and believed that GPs should use the leaflet with patients/parents. Most respondents felt that the leaflet has given them more confidence to self-manage RTIs (88%, 74/84) and that they would keep it for future reference (88%, 74/84). Patients/parents stated that the leaflet changed their views on the need for an antibiotic in 81% (68/84) of responses.

Figure 3. Patient/parents views on the leaflet in the Treat Your respiratory infection leaflet feasibility study, Ireland, 2024 (n = 84).

Although most patients/parents expressed a preference for information to be given to them via text or email (60%, 50/84), some would prefer to receive a hard copy (27%, 23/84), while others would prefer to be directed to a website (25%, 21/84) (Table 2).

Additional comments from patients/parents demonstrate a positive response to the leaflet. They commented that the leaflet was useful in explaining the length of recovery time from illness, overuse of antibiotics, when to get help, and that the leaflet was easy to read, clear and well laid out. One patient commented “it should be in a prominent place in every household.”

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the TY-RTI leaflet was acceptable and feasible to use during RTI consultations and was a useful resource for both GPs and patients/parents, both in daytime and OOH GP services. GPs reported the leaflet was useful to support communication of a delayed or no antibiotic prescribing decision, and they would use it in the future. In particular, GPs found sections on self-care, when to seek help, and expected duration of symptoms useful during the consultation. Patients/parents reported the leaflet was easy to read, and GPs should use the leaflet with patients. For more than 80% of patients/parents, it changed their views on the need for antibiotics for RTIs and gave them confidence to self-manage RTIs, and they would keep the leaflet for future reference. The evaluation of the TARGET TYI-RTI leaflet reported similar findings with 93% (77/83) of patients happy for GPs to use the leaflet with them and 73% (60/83) of patients indicated they would read it again when they got home. Reference Eley, Lecky and Hayes22

The leaflet was mainly used for upper RTI consultations and most frequently for children between 4 months to 4 years. Addressing parental anxiety and unnecessary antibiotic use in children is a priority as this cohort accounts for a large proportion of antibiotic prescribing in primary care both in daytime and OOH GP services, 3,Reference Shah, Barbosa and Stack28 despite most RTIs in children being viral in nature. Reference Timbrook, Glancey and Noble29

The delayed antibiotic prescribing strategy was widely utilized by GPs in this study, with 49% (99/201) of consultations resulting in a delayed antibiotic prescription. There is good evidence that this strategy can reduce overall antibiotic use safely compared to immediate antibiotics. Reference Spurling, Del Mar and Dooley24 Many patients are not aware of the delayed antibiotic prescribing strategy; Reference Bunten, Hawking and McNulty17 therefore, information on delayed antibiotics in the leaflet can contribute to patient awareness and understanding of this strategy.

An immediate antibiotic was issued in 11% of consultations, which was not the intended use of the leaflet, illustrating the complex decision-making processes that evolve during GP RTI consultations and the perceived usefulness of the leaflet by GPs when antibiotics were prescribed.

The study shows potential for the use of the leaflet to influence behavior change for GPs and patients. The use of the leaflet helps to address some key determinants influencing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing: patient/parent expectation for an antibiotic and GP perception of that expectation; preservation of GP-patient relationship and ability to effectively negotiate antibiotic use. Reference Sijbom, Büchner and Saadah30 De Bont et al., in a systematic review investigating the effect of patient information leaflets during infection consultations in general practice, found that use of the leaflet reduced antibiotic prescribing, with a tendency to lower re-consultation rates, and had a positive effect on patient satisfaction. Reference de Bont and Alink14

GPs reported that in 30% of consultations, patients/parents requested an antibiotic, similar to other studies conducted in Ireland Reference Shah, Fleming and Barbosa31,Reference O’Connor, O’Doherty and O’Regan32 and higher than reported in other European countries. Reference Domen, Aabenhus and Balan33 We found a higher proportion of antibiotic prescribing in patients/parents who requested an antibiotic. The challenge of changing patients’ perceptions of the need for antibiotics has been illustrated by Eley et al. who reported that although 70% of patients stated they knew most common RTIs get better on their own, 43% would still want an antibiotic for their child or relative. Reference Eley, Lecky and Hayes22

The TY-RTI leaflet aligns with the COM-B model (capability, opportunity, motivation) for behavior change. Reference Michie, van Stralen and West34 It enhances capability by providing knowledge to patients/parents and GPs on the self-management of RTI providing supportive information and advice or skills to self-manage at home. It provides information to motivate patients/parents by describing the lack of efficacy of antibiotics in treating viral illness and presenting the potential adverse consequences of antibiotics. It provides resources to motivate GPs to engage in further communication with patients/parents presenting with RTIs. 35 It provides a valuable opportunity to change patients/parents’ antibiotic-seeking behavior, with minimal impact or a reduction on consultant time, to encourage self-management, improve communication between GPs and patients with the leaflet being a physical resource for the patient to take home.

This study provides reassurance that using the leaflet did not significantly impact on consultation time. Given the current time constraints in GP practice, it is important that any additional intervention does not lengthen consultation time. Reference Crosbie, O’Callaghan and O’Flanagan36

Patients indicated a mixed preference for digital and hard copies, and both formats should be made available to GPs to use. Data from the UK suggests both digital and printed copies of the TARGET Treating your RTI leaflet are used in practice. 3 Studies point to passive sharing of information (eg, having leaflet available in the waiting room) having minimal impact on antibiotic prescribing. Reference Plate, Di Gangi and Garzoni37 The leaflet is designed to be used during consultations as a communication tool and not just to be given to patient as a parting gift. Reference Bunten, Hawking and McNulty17

Evidence suggests that multi-faceted interventions are more effective in reducing antibiotic prescribing for RTIs. Therefore, incorporating other methods (eg, use of rapid diagnostics, enhanced communication skills, audit and feedback, delayed antibiotic prescribing, and physician education) with the dissemination of this leaflet for wider use should be considered. 35,Reference Murphy, Murphy and Ahern38,Reference Arnold and Straus39 There is potential for the use of a TY-RTI leaflet by other healthcare professionals (eg, pharmacists and practice nurses) 3,Reference Eley, Lecky and Hayes22,Reference Plate, Di Gangi and Garzoni37,Reference Ashiru-Oredope, Doble and Thornley40 and this should be explored in further studies.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is that it explored both GP’s and patients’/parents’ views on the use of the leaflet. Consideration of service users’ perspectives is vital to ensure interventions are accessible, relevant, and understandable by patients/parents and thus will have the desired effect.

GPs were recruited from different settings (rural/urban; large/small practices; daytime/OOH) and had a variety of years’ experience in practice. This enabled us to ascertain the feasibility and usability of the leaflet in a variety of contexts. However, there is a selection bias as the GPs recruited to the study may have been more likely to be more engaged with antimicrobial stewardship than the general GP population, which may impact on their views on the leaflet. GPs self-selected patients who they used leaflet for, so information obtained on consultation characteristics may not be generalizable to all RTI consultations.

GPs were asked to use the leaflet when considering a no-antibiotic or delayed antibiotic strategy. However, on some occasions, six GPs used it when prescribing immediate antibiotics, as well as no or delayed antibiotics, while one GP only used it when prescribing delayed antibiotics, highlighting issues with fidelity of the intended use of the leaflet. However, overall feedback from patients and GPs was overwhelmingly positive across all consultations, whether antibiotics prescribed or not, providing reassurance of wide applicability of its use for RTI consultations.

This study supports a wider roll out of this leaflet in GP and OOH practice to support patient education and increase awareness of the risks of antibiotic use and facilitate shared decision making. It can easily be replicated in other countries where such patient-facing resources are lacking.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2025.10253.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the GPs who gave their time to participate in the study, the participating patients/parents, and the Health Service Executive (HSE) National Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control (AMRIC) Programme, Ireland for supporting this study.

Financial support

Mala Shah is supported by a University College Cork, College of Medicine and Health Employment-based Doctoral Scholarship. Printing of leaflets for the study was funded by the Health Service Executive National Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control Programme, Ireland.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.