Introduction

The increase in the European Parliament's (EP's) legislative power post‐Lisbon Treaty was matched by a surge in studies investigating the legislative behaviour of members of European Parliament (MEPs) (Hix & Høyland Reference Hix and Høyland2013). A consolidated body of research examined how institutional factors and individual‐level characteristics shape MEPs as political actors navigating a multilevel system of governance and the challenge of multiple political principals (Daübler & Hix Reference Daübler and Hix2018). Recognizing its growing institutional relevance and status as a key lobbying venue, scholars of European Union (EU) interest groups also started examining the EP in light of theories of interest representation. This research proposed excellent systematic analyses of lobbying strategies targeting individual legislators (Marshall Reference Marshall2015), groups’ access to EP committees (Marshall Reference Marshall2010), their relationships and policy alignments with European party groups (Beyers et al. Reference Beyers, De Bruycker and Baller2015) and levels of lobbying success (Dionigi Reference Dionigi2017). Despite these noteworthy contributions, the interactions and ties between individual MEPs and interest organizations remain largely unexplored and systematic analyses of how MEPs perceive, understand and approach their relationship with organized interests are conspicuously absent (Bunea & Baumgartner Reference Bunea and Baumgartner2014).

Interest groups are key sources of political and policy‐relevant information and potential policy coalition partners. In addition to parties and voters, interest groups are an important set of actors that MEPs pay attention to and interact with. Yet, MEPs have limited time, staff and information‐processing resources. And the EU system of interest organizations is complex, dynamic and densely populated by a wide diversity of actors competing for decision‐makers’ finite attention and time. Getting the interest and attention of decision‐makers is a crucial yet generally scarce commodity for organizations whose raison d'etre is to communicate with, lobby and influence decision‐makers (Fraussen et al. Reference Fraussen, Graham and Halpin2018). This supports their organizational survival and lobbying efforts. Therefore, an interesting puzzle revolves around the ways MEPs navigate this complex system of organizations and recognize some (over others) as relevant and important actors, worthy of their attention. From a multitude of organizations attempting to get their attention, MEPs decide to pay attention only to a subset of actors. If an organization mobilizes and seeks access to decision‐makers, this act of attention‐giving (recognition) may constitute a first step towards building MEP–interest group relationships, gathering and transmitting information, building policy coalitions and lobbying legislators. If an organization's efforts to reach out to a legislator are met by the legislator's recognition, then recognition may constitute an important first step towards access to decision‐makers (Binderkrantz & Pedersen Reference Binderkrantz and Pedersen2017). Interest group recognition is thus relevant for understanding the role of elites in shaping patterns of interest representation and private actors’ access to and role in decision making.

We address this puzzle and ask: What explains MEPs’ decisions to recognize some organizations (and not others) as relevant policy actors? We answer by building on theories of legislative behaviour and informational theories of legislative lobbying. We argue MEPs recognize organizations that are instrumental for achieving their votes, policy and office‐seeking goals (cf. Müller & Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999). We focus on legislators serving in EP8 (2014–2019 term) and seize the opportunity to use social media to directly observe MEPs’ public recognition of an organization. We adopt an innovative approach and argue that MEPs’ decision to follow certain organizations on Twitter constitutes a reliable and valid indicator of MEPs’ recognition of interest groups. We recognize this social media platform as a rich and relevant source of information about legislators’ communication and ties to various publics (Barberá Reference Barberá2015) and build on the research emphasizing the importance of Twitter as a tool carefully used by MEPs as part of their political communication strategies (Fazekas et al. Reference Fazekas, Popa, Schmitt, Barberá and Theocaris2020).

We find support for the re‐election and policy‐seeking/career‐progression logics. MEPs are more likely to recognize organizations representing interests from their national Member State (MS), especially under flexible‐ and open‐list electoral institutions. To satisfy the dynamics of policy seeking and career‐progression, MEPs use their time and information‐gathering efforts judiciously. They are more likely to pay attention to organizations that, within a shared policy domain, share their ideological leaning and enjoy high prominence amongst peer organizations. Legislators are interested in organizations that provide high‐quality information as legislative subsidy and help them reach consensus in committee decision making.

We speak to the well‐established literature on MEPs legislative behaviour, the literature on EP lobbying (Marshall Reference Marshall2012; Klüver Reference Klüver2013), the research on parties–interest group links (Allern & Bale Reference Allern and Bale2012) and the literature on MEPs’ use of social media (Nulty et al. Reference Nulty, Theocharis, Adrian Popa, Parnet and Benoit2016). We indirectly provide interesting insights for the emerging literature exploring interest groups’ use of social media, although we do not explicitly focus on this topic (Van der Graaf et al. Reference Van der Graaf, Otjes and Rasmussen2016; Chalmers & Shotton Reference Chalmers and Shotton2016).

We contribute in three ways. Conceptually, we propose interest group recognition as a relevant concept for understanding links between legislative and non‐legislative actors. We highlight the connection between recognition and legislators’ informational needs and explain how recognition is a scarce yet valuable resource for organizations and may constitute one of the first steps facilitating access to decision‐makers. We emphasize the conceptual relevance of recognition in relation to lobbying access and organizational prominence, while noting its separateness and conspicuous neglect (Halpin & Fraussen Reference Halpin and Fraussen2017). We address this gap and place recognition central stage in understanding legislators–groups ties. Theoretically, we build on a classic framework explaining legislators’ behaviour and incentives, and we innovatively refine it through the lenses of informational theories of lobbying and legislative decision making. We recognize the importance of the broader institutional and policy context in which MEPs operate and how they react to and interact with it. Empirically, we propose an original research design that builds on social media data. Our empirical strategy constitutes a significant improvement insofar that it reduces the challenges of measurement bias usually associated with self‐reported data generated through interviews, surveys or the textual analysis of newspaper articles or official documents. We also innovate by using the broadest sampling framework currently available for identifying EU organizations: the Transparency Register (TR). Our research design allows using fine‐grained measures of key dependent and explanatory variables and offers the very first analysis of MEPs’ interest group recognition that holds across decision‐making events and policy areas.

Interest group recognition

Understanding interest group recognition by MEPs is relevant for several reasons. First, interest organizations constitute a key source of policy and political information for MEPs, serving as policy experts and channels of interest representation for sectoral, national and European interests. Yet, as political elites, MEPs are selective in their choice of information sources and their attention‐giving is meaningful. Understanding why and how MEPs recognize as relevant and worthy of attention some organizations provides important insights about which actors may attract MEPs’ interest and inform directly or indirectly their decision making. Second, since organizations compete for decision‐makers’ attention, time and contact‐making (Fraussen et al. Reference Fraussen, Graham and Halpin2018), studying their recognition by MEPs provides valuable knowledge about which organizations were successful in this competition and their efforts to get attention. Recognition may thus provide information about which interests have better prospects to play a role in EU legislative politics. Third, the level of EP lobbying and the number of MEP–group interactions significantly increased recently as attested by a surge in the number of issued EP‐entry passes (Ripoll Servent Reference Ripoll Servent2018), indicative that non‐legislative actors play a relevant role in institutional power struggles and policy negotiations, affecting MEP behaviour. Knowing more about MEP interest group recognition offers insights about how factors located outside the legislative arena may shape processes within it. Fourth, the EU lacks a well‐defined legal framework to regulate MEP–group interactions (Bunea Reference Bunea2018). Examining interest group recognition constitutes a promising start in identifying patterns of legislator–group ties and provides information about how elected representatives themselves may introduce bias in representation by becoming significantly more susceptible to hearing the views of some interests over others (Beyers Reference Beyers2017).

We define recognition as the attention an organization gains from a decision‐maker. This attention is publicly visible and attests to an organization's relevance that is not context specific: it is not issue, policy or event related. Different from more context‐specific forms of attention, such as mentions in news reports (Binderkrantz Reference Binderkrantz2012) or legislative speeches (Fraussen et al. Reference Fraussen, Graham and Halpin2018), recognition captures a decision‐maker's interest in an organization that is motivated by broader and longer‐term considerations that are not informed by specific, time‐delimited circumstances, and accounts for a more permanent form of organizational relevance and decision‐maker attention. Being susceptible to public scrutiny, recognition allows decision‐makers to convey a public message about what they generally appreciate and value as relevant policy actors and sources of information.

Recognition is a continuous concept ranging from no attention to a lot of attention from a decision‐maker and can take several forms. It can be gained in various political arenas. We focus on MEPs as one important set of decision‐makers and examine recognition at the level of dyads involving individual decision‐makers and individual organizations.

Conceptually, recognition relates to two key concepts in interest groups research: lobbying access and interest group prominence. Interest group access to decision‐makers is unanimously recognized as ‘a result of groups seeking access by approaching the arena and gatekeepers allowing the groups access’ (Binderkrantz & Pedersen Reference Binderkrantz and Pedersen2017: 310). Both conditions are necessary and jointly sufficient for access to emerge. Getting recognized by decision‐makers may be an important first step that may facilitate organizational access to decision‐makers, based on the assumption that legislators are more likely to grant access to organizations they deem relevant and worthy of attention. In this respect, getting MEP recognition may be one of the basic prerequisites for an organization to be granted access to decision‐makers.

Recognition shares with the concept of interest group prominence a focus on a group's relevance for decision‐makers. Both recognition and prominence are ascribed by political elites to private actors. Halpin and Fraussen (Reference Halpin and Fraussen2017: 725) indicate ‘recognition or favourable notice of a group by policymakers’ as the observable implication of prominence which they define as when ‘a group has pre‐eminence for a particular constituency or viewpoint and is therefore “taken‐for‐granted” by a prescribed audience’. Grossmann (Reference Grossmann2012: 48) employs a similar definition to study the prominence of public interest groups in American policymaking, using media attention to measure prominence.

Our concept of recognition differs from prominence in two ways. First, recognition is not dependent upon an organization being prominent for representing a particular constituency/viewpoint. While prominence implies that organizations must become in some way distinct from organizational peers (mainly those representing and sharing their specific constituency of interests/viewpoints) to get noticed by decision‐makers, recognition entails a form of attention‐giving that is meaningfully ascribed by elites based on a more complex set of considerations, which include political calculus and a broader assessment of a group's general characteristics, resources and credentials. Recognition is informed by considerations that go beyond importance relative to peer‐organizations representing the same interests/viewpoints. For example, decision‐makers might give recognition to organizations whose primary goal is to defend their own (economic) interests (i.e., companies) and not represent a constituency of interests. Decision‐makers might not recognize certain prominent (amongst peers) groups if, for example, they strategically aim to exclude from policymaking the constituencies or viewpoints they represent. Conversely, decision‐makers might have strategic incentives to recognize groups that do not have pre‐eminence as representatives of particular constituencies but provide other important resources such as expert/technical advice. Second, prominence is context‐dependent (organizations are ‘top of mind’ for politicians relative to specific circumstances) and emphasizes an organization's quality of being ‘worthy of attention’. Recognition is underpinned by considerations that are not context‐specific and captures actualized attention received from decision‐makers. Overall, prominence depends a lot more on what an organization stands for, while recognition depends to a larger extent on decision‐makers’ perceptions of what an organization can provide as a valuable political or policy good. We consider prominence and recognition as two distinct yet related concepts. While large‐scale measures of organizational prominence in the EU are absent, in our empirical analysis we use the centrality of an organization among other groups within a policy domain as a proxy measure for this concept, as part of our explanatory variables.

Explaining MEPs’ recognition of interest groups

To understand MEPs’ recognition of interest groups, we build on and refine a classic theoretical framework developed by Müller and Strøm (Reference Müller and Strøm1999) to explain parties’ and politicians’ behaviour. This framework describes them as vote‐seeking, policy‐seeking and career‐seeking actors. We argue that MEP legislative behaviour is motivated by electoral incentives (re‐election), policy incentives (achieving policy goals, shaping legislation in line with their preferences, exerting policy influence) and ensuring their career progression in the legislature (getting key agenda‐setting and decision‐making committee roles). These incentives are also relevant for explaining MEP behaviour towards non‐legislative actors. Policy‐seeking and career‐progression objectives are to a large extent intertwined and closely linked in the context of legislators’ work in EP committees (Daniel Reference Daniel2015). We discuss how electoral incentives on the one hand, and policy and career objectives on the other shape MEPs’ decisions about which organizations to recognize as relevant actors.Footnote 1

We contend MEPs use their relationship with organizations to enhance their electoral prospects and support their legislative activities. While important, establishing links with interest groups is not cost‐free: legislators have limited time, attention and staff resources, while the number of organizations competing for their attention is high. Usually, organizations initiate contact themselves, seeking and demanding legislators’ attention in events, meetings or online platforms. MEPs want relevant, high‐quality, reliable information from trustworthy sources that help them perform their representative mandate and organizational roles. Therefore, MEPs must be discerning and strategic about whom they give attention to. They selectively deploy their attention by considering the extent to which being able to be (even remotely) in touch with some organizations helps in achieving their goals. This decision is underpinned by their informational needs. Depending on which goals they try to maximize, MEPs need different information and thus assign recognition to different actors. This leads to different observable implications regarding patterns of MEP recognition behaviour.

Electoral incentives

MEPs’ re‐election depends on electorates in their home countries (in some cases divided into regional constituencies) and national parties. The relative importance of each varies with the electoral system, particularly its ballot structure. Setting aside the rather risky options of running as independent candidates or creating their own parties, under all electoral systems used for European elections, MEPs need to be re‐selected by their parties to have a chance of re‐election. More open ballot systems (single‐transferable vote (STV) or open‐list proportional representation (PR)) give substantial leverage for voters to decide which candidates nominated by the party get elected, while closed‐list systems leave this choice entirely to parties. MEPs have greater electoral incentives to be responsive to their constituents under electoral systems with more open ballot structures. Electoral systems have important implications for legislative behaviour: MEPs elected under more open electoral systems are more likely to vote in line with the public opinion in their electoral constituencies against the wishes of their European party‐groups (Däubler & Hix Reference Daübler and Hix2018). We expect that under flexible‐ or open‐list or STV systems MEPs will be particularly interested to recognize organizations that increase their individual electoral appeal. Even under closed‐list systems, candidate attractiveness is an important consideration for national parties when deciding whether to re‐nominate incumbents (Frech Reference Frech2016). We consequently expect that under closed‐list systems MEPs will recognize organizations that help them increase their re‐election chances, although less so than under systems with more open ballot structures.

We argue that organizations from an MEP's home‐MS are most relevant for enhancing electoral attractiveness. The public recognition of an organization increases the probability of engaging with them in a dialogue and indicates a willingness to listen to its policy demands and feedback. Some organizations may even consider recognition as an invitation to access and dialogue. Building on Essaisson et al. (Reference Essaisson, Gilljam and Persson2017), we argue that establishing this recognition‐based listening channel is fundamental in a multilevel system of governance in which the electoral connection between voters and legislators is weaker than at national level (Hix & Høyland Reference Hix and Høyland2013). Paying public attention to organizations representing relevant constituencies of national interests and recognizing them as relevant actors represents a minimum and necessary condition MEPs must satisfy in order to build and maintain a legitimate mandate as elected representatives of national constituencies and trustworthy ‘national constituency advocates’. Organizations from home‐MS are best placed to provide MEPs with information about the positions of voters or organized interests in their constituencies on specific legislative proposals. Without such information (which is hard to come by in other ways), MEPs risk voting against the preferences of their constituents. These organizations provide valuable feedback about the impact of European legislation on policy realities at national, regional and local levels. Also, these organizations might be familiar to MEPs from national politics, and may have strong incentives to actively reach out and get legislators’ attention because of their national representative mandate.

By recognizing as relevant and worthy of attention organizations voicing constituency demands based in their home‐MS, while adapting their legislative behaviour in line with these demands, MEPs can increase their attractiveness as candidates in the next election. Conversely, not doing so would put an MEP's re‐election at risk if neglected organizations use media to criticize him/her for doing this or, in rare instances (Allern et al. Reference Allern, Hansen, Marshall, Rasmussen and Webb2020), provide negative input to the candidate selection process in the MEP's national party.

Therefore, when motivated by re‐election incentives, we expect that:

H1: MEPs are more likely to give recognition to organizations based in their national MS, especially under electoral institutions that provide voters with more power to select individual candidates.

The electoral system should obviously not have an effect on recognition when the MEP and group do not share a home‐MS.

Policy influence and career progression

MEPs also want to exert policy influence and achieve career progression within the EP by gaining access to powerful institutional positions. EP committees play a key role in achieving this: They offer the opportunity to amend and shape legislation, as well as the opportunity to demonstrate policy expertise and political skill in the successful completion of important committee roles such as chair, rapporteur or shadow‐rapporteur (Scherpeel et al. Reference Scherpeel, Wohlgemuth and Lievens2018). Informational and partisan theories of legislative committees explain MEPs’ policy influence in committee and plenary decision making and their success in securing important committee roles that attest and further develop career progression (Yoshinaka et al. Reference Yoshinaka, McElroy and Bowler2010).

In the EP, policy‐seeking and career‐seeking objectives overlap significantly and are highly intertwined (Daniel Reference Daniel2015). Both are facilitated by a common set of ‘decisive characteristics’ such as policy expertise and political experience, dedication and perceived party loyalty (Chiru Reference Chiru2020). However, policy seeking takes precedence over and conditions in many ways career seeking: A successful achievement of policy objectives attracts new assignments to powerful institutional roles later down the line of their legislative mandate and therefore contributes significantly to career progression (Daniel Reference Daniel2015). We contend that MEP career‐incentives are subsumed to their policy‐seeking objectives and focus analytically on explaining how MEP policy‐seeking behaviour shapes their recognition of organizations.

Building on informational theories of legislative committees, we note EP committees are highly specialized decision‐making settings requiring a high amount of policy‐relevant information and expertise necessary for amending and adopting what constitutes highly technical legislative acts. They also require the ability to reach consensus and work with other political actors (Yoshinaka et al. Reference Yoshinaka, McElroy and Bowler2010). To exert influence over committee decision making and achieve their policy goals, MEPs must: develop and consolidate their policy‐specific knowledge and expertise relevant for the policy areas assigned to their committee; while acquiring political skill and knowledge about how to reach consensus within committee decision making (Neuhold Reference Neuhold2001). MEPs must become both good ‘technicians’ and skilful ‘negotiators’ (Daniel Reference Daniel2015: 28–29).

Theories of lobbying as legislative subsidy indicate organizations supply legislators with two types of information: policy expertise and political intelligence about what other decision‐makers and/or private actors want and do on specific issues and legislative proposals (Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006: 74). An obvious, up‐to‐date and relatively easy to tap into source of policy‐relevant expertise are the organizations affected by or interested in the policy areas covered by the EP committees MEPs are members of. Research shows that ‘relative to legislators, lobbyists are specialists’ (Hall & Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006: 73). MEPs are more likely to recognize as relevant, actors with which they share a policy domain. Since legislators have limited resources, they need to maximize the process of information‐gathering and processing. They pay attention to a limited and manageable number of organizations. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that MEPs will more likely identify and recognize as relevant those organizations that, within their policy domain, share their preferences over policy outcomes. These natural ‘policy friends’ have incentives to provide MEPs with relevant, high‐quality information at a low cost since they work towards common policy goals (Marshall Reference Marshall2010). These organizations may be part of what Neuhold (Reference Neuhold2001) describes as MEPs’ own ‘established network of experts, which they are comfortable dealing with’ on specific policy issues and domains. This leads us to expect that MEPs are more likely to recognize organizations that inhabit their policy domain and with which they share ideological affinities. Of course, paying attention to organizations with different, perhaps even opposite ideological orientations may also be appealing to MEPs, especially when attempting to estimate levels of opposition or to build an informational advantage in legislative information networks (Ringe et al. Reference Ringe, Victor and Gross2012). However, this is a significantly less likely scenario because legislators know that: these organizations are less likely to become part of their legislative coalitions; and they have strategic incentives to build a good reputation with and provide their best‐quality information to their legislative friends and not to their policy foes (Marshall Reference Marshall2015).

Equally important, groups can also offer MEPs political intelligence about the political and policy environment in which MEPs operate as decision‐makers within a policy domain. In the EU, information about the level of expected opposition on behalf of affected interests and how to build consensus around finding feasible policy solutions is particularly relevant. Hall and Deardorff (Reference Hall and Deardorff2006: 74) argue that organizations located centrally in issue networks are particularly well placed to offer legislators this type of information (see also Box‐Steffensmeier et al. Reference Box‐Steffensmeier, Christenson and Craig2019). These central organizations are also likely to possess high levels of policy expertise because their network position facilitates access to the flow of policy‐relevant information. Their central position may also indicate a higher than average endowment with organizational and informational resources.

We contend that, within a shared policy domain, the prominence (centrality) of an organization within the community of interest groups is a key consideration for MEPs when deciding which non‐legislative actors to recognize as relevant. Although interest group prominence in a shared policy field matters in itself, we expect for it to be particularly consequential in MEPs’ decisions to follow a group when the two share ideological affinities, in line with ‘lobbying as legislative subsidy’ argument.

To maximize information monitoring, gathering and processing, MEPs have incentives to recognize as relevant those organizations that simultaneously display three characteristics: they share MEPs’ policy domain, share MEPs’ ideological leaning and they are prominent in the interest group community active in this shared policy domain. We therefore expect that:

H2a: MEPs are more likely to give recognition to organizations that share their ideological leaning, but only if these actors are prominent organizations in a shared policy area.

H2b: MEPs are more likely to give recognition to organizations that are prominent organizations in a shared policy area, especially when these organizations share MEPs’ ideological preferences.

Research design

Measuring recognition

We examine MEPs serving in EP8 (2014–2019). Our unit of analysis is a MEP–organization dyad. Our dependent variable is dichotomous, indicating whether the MEP gives recognition to the organization in the dyad.

We operationalize MEPs’ recognition of interest groups by using social media data. We looked at MEPs’ Twitter accounts and based on the ‘Following’ tab, we identified the organizations MEPs decided to follow on Twitter. We use the inclusion of an organization in this ‘Following’ category as an indicator of its recognition by the MEP. This is a measure that to our best knowledge has not been yet used in the literature. Therefore, we detail first its construction and present several validation tests. We note that while some MEPs manage their Twitter accounts, many more may decide to entrust the daily management of accounts to their advisory team (assistants). It is reasonable to assume though that MEPs delegate this task to staff members that act loyally and in line with MEPs’ legislative objectives.

While Twitter offers a rich amount of information such as re‐tweets, replies or hashtag mentions that could potentially provide alternative and more nuanced measures of attention‐giving, we adopt a binary measure instead and focus only on the Twitter‐following ties, for two reasons: first, our concept captures a generalized, context‐independent form of attention‐giving which our binary measure captures well. Re‐tweets, replies and mentions provide a context‐specific form of attention‐giving insofar as they are used in relation to specific issues or events. Second, our theoretical framework speaks of Twitter as a channel of information‐gathering used by MEPs to stay in touch with key constituencies and policy actors. This assumes MEPs make a more sophisticated use of Twitter that goes beyond broadcasting and includes information‐monitoring in more confidential, ‘stealth’ mode. Our binary measure is able to capture this better than potential alternative measures.

We developed several criteria for including MEPs in our analyses. First, we examine only MEPs that were elected in the 2014 election and served until the last plenary session of EP8 in April 2019. This accounts for a total of 647 MEPs. Eliminating MEPs that stayed in legislature for a shorter period than (almost) the whole term reduces the likelihood that links between MEPs in our sample and organizations are driven by other roles MEPs had before or after joining the EP. Second, we included MEPs with a Twitter account: 564 MEPs out of 647 had accounts, thus confirming the findings of other studies indicating high levels of MEPs’ social media use (Nulty et al. Reference Nulty, Theocharis, Adrian Popa, Parnet and Benoit2016). Third, we excluded MEPs having missing data on one or more independent variables discussed below: this leaves 545 MEPs for the explanatory analysis.

We use the EU TR to identify the population of interest groups. This constitutes an ideal data source for our research design. First, it offers the broadest sampling frame currently available to systematically identify organizations participating in EU policymaking. Second, despite criticism of its data quality, the Register offers a systematic, generous amount of information about organizational profiles and domains of policy interest and activity. This makes it a valuable source particularly well‐suited for our research design. Third, the Register contains the list of all organizations with EP‐entry passes. This allows identifying actors that are most likely to seek and get access to MEPs and are part of the myriad of organizations that legislators are acquainted with and get to choose from when picking their sources of information, expertise and policy‐coalition partners (Neuhold Reference Neuhold2001).

TR‐data was downloaded in February 2019. The dataset included 11,882 organizations. To identify Twitter‐handles, we examined the first pages of organizations’ websites in March 2019 using R. Manual checks were performed on the Twitter‐handles identified by automatic search, and for all organizations for which this search did not identify handles. We identified 7,791 organizations (approximately two‐thirds of TR‐organizations) with available information about Twitter accounts.

We identified 15,164 instances of MEP following an organization for 564 MEPs and 7,791 organizations. This represents more than 0.3 per cent of all possible MEP‐organization dyads (4,394,124). The median number of followed‐organizations (13.5) is around 2per cent of the median number of actors followed by a MEP (691). Among MEPs, 53 did not follow at least one organization and 38 followed one. Close to three quarters (72 per cent) followed five or more. Top five MEPs following the highest number of organizations were: Julie Ward (539; S&D, UK), Brando Benifei (435; S&D, Italy), Marietje Schaake (305; ALDE/ADLE, the Netherlands), Sirpa Pietikäinen (270; EPP, Finland) and Henna Virkkunen (182; EPP, Finland). These low levels of recognition confirm that decision‐makers’ attention is in limited supply, and a valuable resource for organizations. They also indicate a key consequence of the large organizational networks MEPs face in Brussels: they must rationalize their links and make strategic decisions about whom to recognize as relevant actors and sources of information.

This original operationalization and measurement strategy of our dependent variable is justified in several ways that illustrate the content, face and convergent validity of our measure. Regarding content validity, we note that large‐scale analyses of following behaviour indicate Twitter is both a social network and an information network. Myers et al. (Reference Myers, Sharma, Gupta and Lin2014: 493) argue that ‘it is undeniable that many follow relationships are built on social ties, for example, following one's colleagues…Twitter behaves like a social network’. Politicians are no exception. In addition to its important role as a communication‐tool with voters (Daniel et al. Reference Daniel, Obholzer and Hurka2019), Twitter's relevance as a social network for politicians is suggested by analyses showing they mostly follow other elite actors: particularly other politicians, but also interest groups (Spierings et al. Reference Spierings, Jacobs and Linders2019). We argue MEPs (and/or their assistants) follow organizations whom they consider as relevant in their professional/social networks and with whom they may have even engaged previously. Given that organizations are part of their networks, MEPs may be ready to offer them access (e.g., via personal meetings) even if they often may not read the tweets of these actors. This is in line with our conceptualization of recognition.Footnote 2 Further, the act of following a group implies by its very nature paying attention to the organization, which is also in line with our concept of recognition. Following an organization on Twitter is meaningful: media scrutinizes and reports on MEPs’ Twitter activities including whom they followFootnote 3; and organizations consider it important to be publicly listed on MEPs’ Twitter‐following category, given that politicians’ attention is in limited supply. Other organizations also attempt to get listed and this represents a confirmation of successful attempts to get noticed (by, for example, even initiating the Twitter following) and an aspect that may improve prospects for access to legislators and decision making.

The social network features of MEPs’ Twitter‐following decisions are reinforced by the fact that 51 per cent of these decisions in our sample are reciprocated by organizations. While many following‐decisions may be MEP‐initiated (potentially based on the cues from other actors, such as fellow politicians), we also expect that in many cases MEPs reciprocate an organization's attempt to follow them first. Similar to MEPs, organizations are likely to use Twitter to initiate, maintain and strengthen, contacts with decision‐makers, as indicated by research showing that community‐building and preservation is essential for organizations’ use of Twitter (Lovejoy & Saxton Reference Lovejoy and Saxton2012).

Twitter is also an information network. As already mentioned, MEPs’ Twitter‐following decisions are motivated by information‐seeking, particularly in the case of organizations that are not in MEPs’ offline social/professional networks. The decision to follow an organization implies MEPs understand and accept (and in some cases even eagerly anticipate) that information from the group will (occasionally) show up on their Twitter‐feeds. MEPs observe information from a subset of organizations they follow. Similar to other Twitter‐users, MEPs are likely to face information overload if they follow too many organizations. Common responses to mitigate overload are reading only parts of the tweets or using software features to reduce the amount of information seen (Sasaki et al. Reference Sasaki, Kawai and Kitamura2016). While MEPs may be using these strategies with regard to organizations they follow (thus reducing or perhaps even eliminating information from them), we argue that the decision to follow the group initially (without unfollowing it later) still indicates an MEP's openness to receive information from it. An MEP may be constrained in receiving information via Twitter, but he/she is also likely to be open to receive information from a group by offering it access via other means (e.g., personal meetings, emails). The act of continuing to follow the group implies attention from the MEP in line with our concept of recognition.

Second, the distribution of recognition across organizations is highly skewed and provides anecdotal evidence supporting the face validation of our measure. It confirms the elite pluralist nature of the EU interest group system: 4,657 (60 per cent) of organizations did not have a single MEP following their Twitter accounts. Conversely, 67 (almost 1 per cent) organizations were followed by more than 5 per cent of MEPs and represented one quarter (3,727 out of 15,164) of all dyads with recognition. These organizations are well‐established actors in the EU lobbying community. Supporting Information Appendix 1 lists 25 organizations followed by more than 10 per cent of MEPs (57 or more) and the distribution of MEPs following organizations on Twitter (Figure A1.1).

Third, to investigate convergent validity, we first use a measure of organizational contact with MEPs based on whether the group follows the MEP. As contact making is one of the two dimensions of access alongside recognition, we expect contact and recognition to be correlated. We find 51,713 instances in which organizations follow MEPs. In 7,768 cases these were reciprocated ties. The polychoric correlation between the dichotomous variables of MEP following an organization and an organization following an MEP is 0.76.

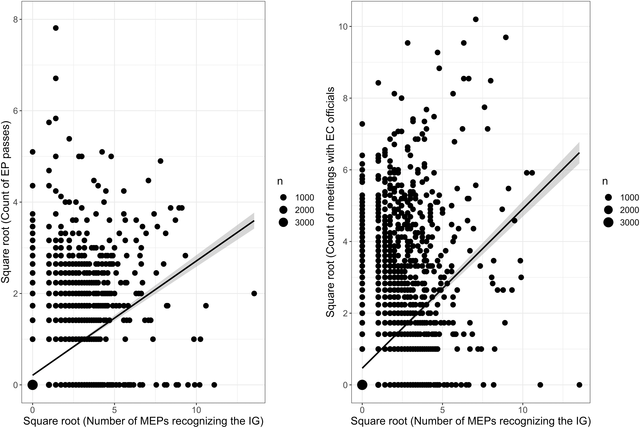

Second, Figure 1 compares the number of MEPs following an organization with the organization's number of EP‐entry passes and number of Commission high‐level meetings since 1 December 2014 (based on LobbyFacts.eu).

Figure 1. Number of MEP Twitter‐followees, EP‐entry passes and Commission meetings.

The number of EP‐passes constitutes a proxy‐measure of organizational access to EP premises. We find a correlation of 0.38 between the two measures. The number of Commission meetings is also a measure of access, although to different decision‐makers. We find a correlation of 0.4.

Explanatory and control variables

Shared‐MS is a dichotomous variable indicating the organizational headquarters (TR‐data) are in the same MS as the one in which the MEP was elected. The Electoral system variable distinguishes between closed‐list, flexible‐list and open‐list or STV systems. The coding is based on Däubler and Hix (Reference Daübler and Hix2018).

MEP's ideological preferences are measured using the general left–right in the 2014 wave of the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015). Some MEPs have changed their national party affiliation since 2014. If information on their new party's policies was available in the CHES dataset, this was used to code the MEP's ideological leaning. Otherwise, we used the information about the MEP's party in the 2014 election as the best available proxy for her/his ideological leaning. One national party represented on average 2.7 MEPs in our sample.

The equivalent measures of ideological preferences for interest groups are not publicly available. Thus, we build on Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012: 22)Footnote 4 and use the type of interest represented as a proxy measure of ideological leaning of an organization. We used TR information to code interest group type: business (associations and individual companies), non‐government organizations (NGOs), trade unions, professional associations, subnational public institutions, think‐tanks, consultancies and academic institutions. This captures well the high diversity of interests and actors participating in EU policymaking as interest organizations. We exclude 239 organizations (3 per cent) that were not included in any of these categories. We expect the preferences of business groups are closer to those of MEPs on the right, while NGOs (which usually advocate the public interest), trade unions and professional associations are generally closer to MEPs on the left. The remaining four types of organizations are likely to have diverse ideological inclinations (think‐tanks) or less focus on ideology (consultancies). We still include these organizations to provide a comprehensive analysis of the patterns of MEP interest group recognition.

To measure interest organization prominence in a shared policy area, we first examine whether a given MEP‐organization dyad is characterized by a shared policy domain. MEPs’ ‘interest’ is identified based on the policy areas that were a primary responsibility of the permanent parliamentary committee(s) of which the MEP was a (full or substitute) member. For organizations, we use self‐reported TR‐information. The variable takes the value of 0 for a given dyad if no policy domain is shared. If one policy area is shared, we identify all other organizations in our sample that also have an interest in this policy area. Using this policy area specific subsample, we identify the number of organizations that follow on Twitter the organization in the MEP‐organization dyad, divide this number by the total count of groups in the subsample and multiply the resulting quantity by 100. This represents the in‐degree centrality of an organization in the policy area measured using Twitter‐follower data that ranges from 0 (no followers) to 100 (all groups in the subsample follow the organization). If the MEP and organization share more than one policy area, we compute in‐degree centrality of the organization across all shared policy domains and take the highest score. In the analysis we use a quartic root of this quantity to account for the right‐skewness of this variable (using other transformations had no significant effect on the results). This measure assumes that, similar to MEPs, organizations are more likely to follow those organizational peers they consider to be prominent in EU policymaking. Supporting Information Appendix 1, section 2, details this measure.

For business, we expect for MEP's ideology variable (more rightist preferences with higher values) to have a positive and increasing‐in‐size effect on recognition. For the minimum values of the prominence variable, the ideology variable should have no effect because the MEP has no incentives to recognize such groups regardless of ideological similarity. Conversely, prominence should have a positive effect on recognition for the whole range of values of the ideology variable because all MEPs have incentives to recognize business organizations highly prominent amongst interest groups. However, the magnitude of this effect should be increasing with higher values of the ideology variable.

The expectations for NGOs, trade unions and professional associations samples are reverse. The ideology variable should have no effect on recognition for the minimum values of prominence, but a negative and increasing‐in‐magnitude effect as the prominence of an organization in a shared policy field increases. The prominence variables should have a positive effect for all values of the ideology variable, but the magnitude of the effect should be decreasing.

For subnational public institutions, think‐tanks, consultancies and academic institutions, we expect no clear effects of ideology as these organizations represent ideologically diverse interests or avoid taking stances in ideological battles. The prominence variables should have a positive effect on their recognition.

A positive effect of a shared‐MS on recognition (H1) may be driven by the language skills of MEPs, as opposed to their electoral incentives. To our best knowledge, the information about MEPs’ language skills is not available. We therefore use the 2012 Eurobarometer 386 survey to construct a continuous measure of MEPs’ skills to speak each EU official language and several major non‐EU languages based on the share of populations in their home‐MS able to hold a conversation in that language. For each MEP–organization dyad, this variable takes a value equal to the share of the population in the MEP's home‐country that speaks the official language(s) used in the country the organization originates from. When an MEP and an organization share a country, the variable value is 1.

Our control variables include: EU‐level organizations (1,213; preferred dialogue partners for EU decision‐makers due to their broad representative mandate); logged number of accounts followed by MEP (MEPs’ Twitter‐following propensity); logged number of followers of an organization; whether the MEP was a committee chair or vice‐chair (these positions imply higher informational needs and motivates MEPs to recognize more groups as relevant information sources); the squared number of legislative and non‐legislative reports an MEP was responsible for in 2014–19; number of EP terms served; the squared root of the percentage of plenary sessions attended in the 2014–19 term. These last three variables account for the arguments that MEPs with more experience and more legislative tasks have higher informational needs and recognize more organizations. We control for MS in Central and Eastern Europe: younger democracies with potentially different patterns of legislators–organization interactions. Sections 2 and 3 in Supporting Information Appendix 2 discuss the inclusion of EP political group fixed effects and control variables for age and gender of MEPs.

Analyses

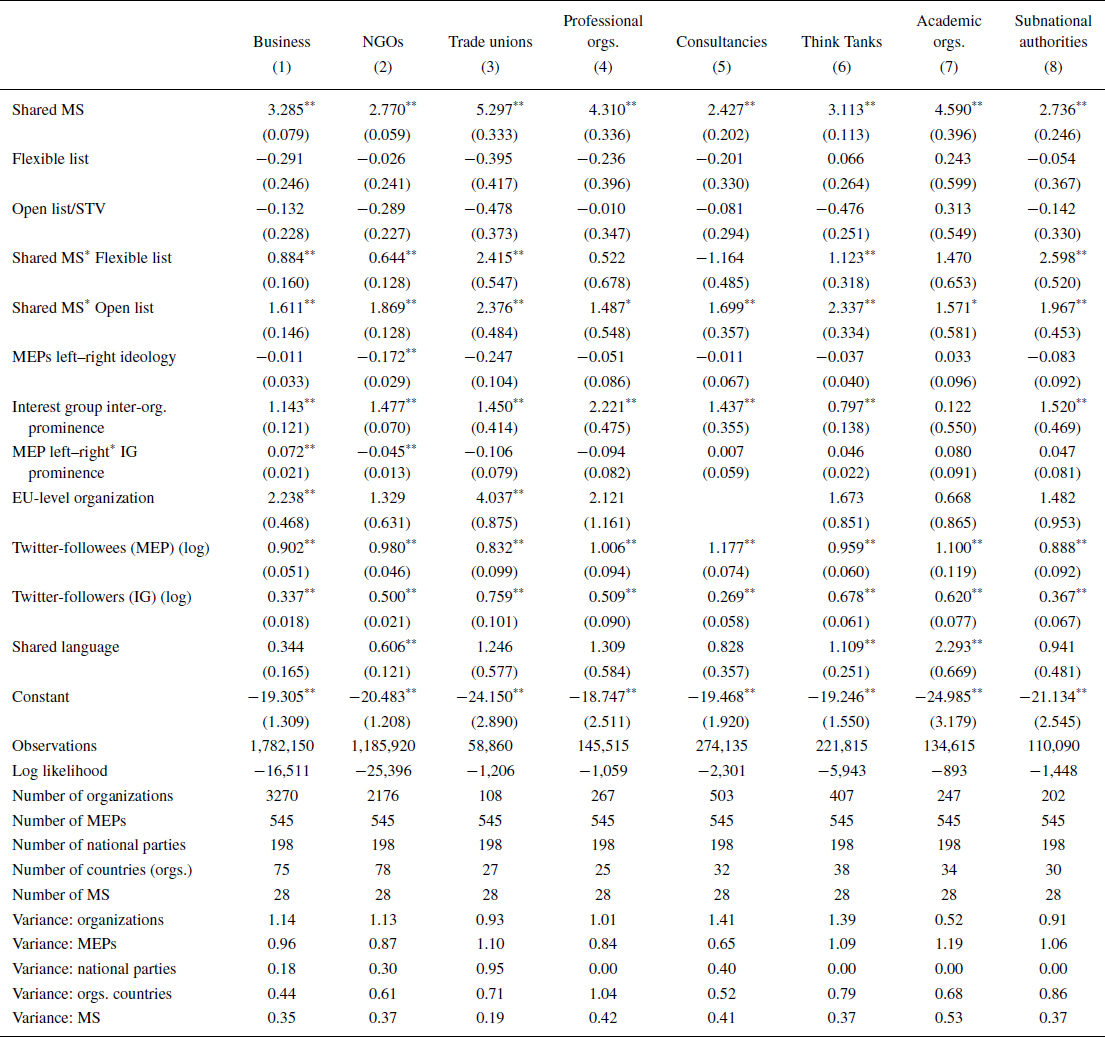

Table 1 presents eight logistic regression models (one for each interest group type). Our data has a complex structure: the unit of analysis is an MEP‐organization dyad, MEPs are nested in their national parties which in turn are nested in MS, and organizations are also nested in the countries of origin. We therefore include random intercepts for MEPs, national parties, MS, organizations and their country of origin. In each model, we include an interaction effect between MEP ideology and organizational prominence in the policy field shared with the MEP. Interest group type and MEP ideology variables jointly measure shared ideological preferences.

Table 1. Logistic regression models of interest group recognition by MEPs

Note: Closed‐list as reference category for electoral system. All models include variables for EP committee chair/vice‐chair, participation, number of reports and legislative terms by MEP, and CEE country. Supporting Information Appendix 2, Table A2.1, presents the full version of the regression models. Standard errors in parentheses. **p < 0.001; *p < 0.01.

All models provide consistent support to hypothesis 1. The variables capturing the shared‐MS and organizational prominence in the shared policy domain are statistically and substantively significant across all models, and so are the interactions between shared‐MS and electoral system on the one hand and the MEP's ideological preferences and interest group type on the other hand.

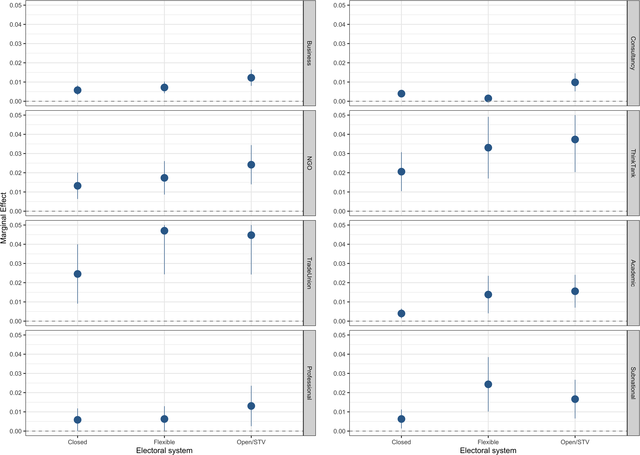

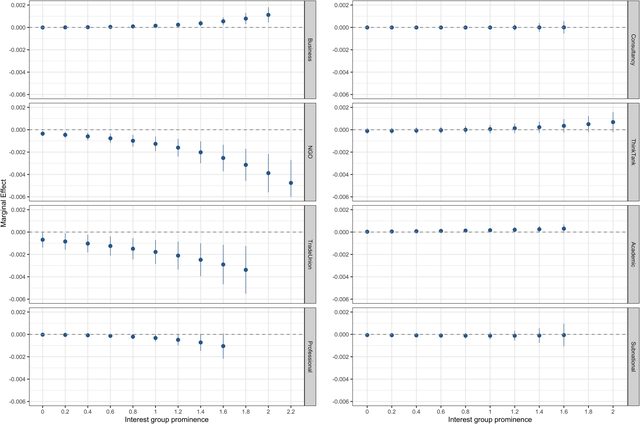

Figures 2, 3, 4 present average marginal effects at theoretically interesting values of conditioning variables (electoral system for H1, organizational prominence for H2a and MEPs’ ideology for H2b) computed using margins package in R (Leeper Reference Leeper2018). We use the probability scale to increase the interpretability of results.

Figure 2. Effects of shared‐MS conditional on electoral system. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Marginal effects. 95% confidence intervals.

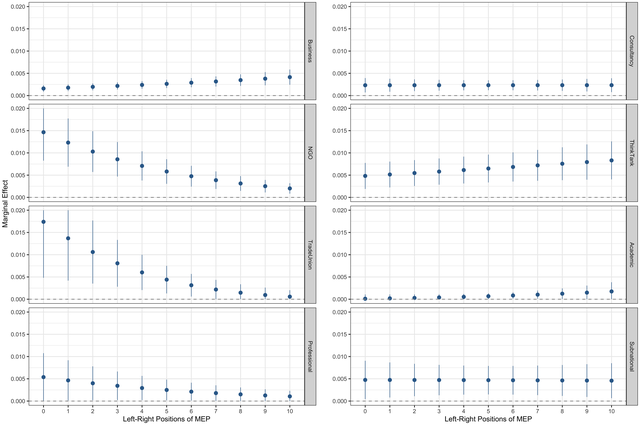

Figure 3. Effect of MEP's left‐right ideology on recognition. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Marginal effects. 95% confidence intervals.

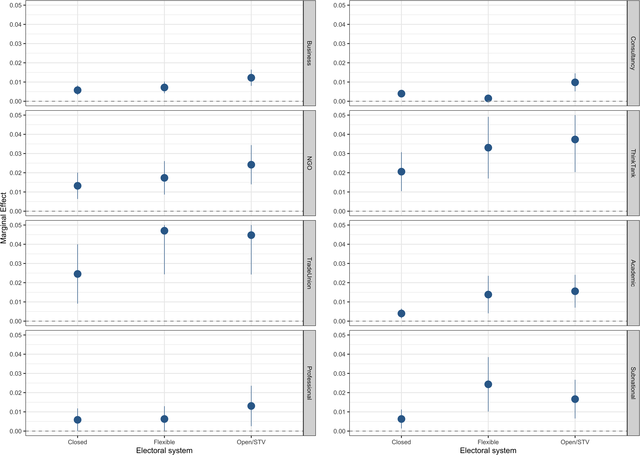

Figure 4. Effect of interest group prominence on recognition. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Marginal effects. 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2 plots the conditional effects for three types of electoral systems based on Model 1. Being from the same MS significantly increases the probability of an MEP recognizing an organization under all electoral systems, but the effect is weaker under closed‐list PR systems. This pattern holds across all types of organizations with a partial exception for consultancies. The effect of a shared‐MS is generally somewhat stronger under the open‐list/STV system than under a flexible‐list system. For example, for NGOs the change in probability under closed‐list, flexible‐list and open‐list/STV systems is 0.013, 0.017 and 0.024, respectively. While these may seem as relatively limited effects, the probability of recognition in a randomly selected dyad is 0.003. Sharing a MS, particularly under an open‐list/STV system, thus increases the probability of recognition multiple times. This by far exceeds the minimum change (10–20 per cent) that King and Zeng (Reference King and Zeng2001: 152) report as indicating the importance of the effect in rare event studies. Notably, these effects persist in the models that include a control variable for shared language (which is also statistically significant, although with a moderately strong effect).

These findings emphasize the role of MEPs as representatives of geographical, national or subnational constituencies and the potential role of organizations in informing legislators about their constituents’ preferences and pressuring them to respond. Crucially, the importance of organizations as transmission belts of national electorates’ preferences is more important under electoral institutions that give more choice to the electorates to punish individual MEPs who were less responsive. This conditioning effect of electoral systems provides important evidence supporting our argument that the extent to which MEPs recognize organizations from their home‐MS is driven by the extent to which these groups are useful in increasing re‐election chances. Also consistent with our argument is the absence (with a partial exception for trade unions) of the effect of electoral systems when the MEP and interest organization do not share the MS.

The results also support Hypothesis 2. In line with H2a, we find that MEP's ideology influences the probability that he/she recognizes a prominent group in a shared policy field. Compared to their leftist counterparts, more rightist MEPs are more likely to recognize the more prominent business organizations and less likely to recognize the more prominent NGOs, trade unions and professional associations. The absolute size of effects reported in Figure 3 is small in absolute terms, but large compared to the overall average probability of recognition. Further, effects are larger for many MEP–organization dyads. For example, a moderate 3‐point leftward shift in the position of the centre‐right (position 6.6) chair of the Environment Committee, Adina‐Ioana Vălean, would decrease the probability of her recognition of BusinessEurope from 0.39 to 0.37 and increase the probability of her recognition of Greenpeace EU from 0.37 to 0.43.

Further, as implied by H2a, an MEP's ideology has no effect on the recognition of the less prominent business and professional associations. However, more leftist MEPs are more likely to recognize even the less prominent NGOs and trade unions, but, importantly, the magnitude of the effect is weaker than for the more prominent organizations. Lastly, as expected, the overall left–right ideology of MEPs has no effect on the recognition of consultancies, think‐tanks and academic and subnational organizations.

The results also support H2b (Figure 4). More prominent organizations are more likely to get recognition. This applies to all types of organizations except for academic institutions. Further, as expected, the effect of prominence increases in size when an MEP and organization share an ideological leaning. For business, the effect of prominence on recognition is stronger for more rightist MEPs than for their leftist colleagues. Conversely, prominence has stronger impact on the recognition of NGOs, trade unions and professional associations by leftist MEPs. The absolute size of these effects is much higher compared to the average probability of recognition; and the effects are very large for certain dyads. For example, if BusinessEurope and Greenpeace EU had prominence of 0 in relation to Adina‐Ioana Vălean instead of the actually observed prominence of 1.6 and 1.8, the probability of their recognition by this MEP decreases from 0.39 and 0.37 to 0.04 and 0.07, respectively. Since Vălean was a centre‐right MEP, the effect is somewhat stronger for BusinessEurope than for GreenpeaceEU.

Interestingly, more rightist preferences of MEPs also increase the effect of prominence for think‐tanks on their recognition. No similar relationship was observed for consultancies, academic institutions and subnational authorities: the substantive size of the effect of prominence shows limited or no relationship with an MEP's ideology. Supporting Information Appendix 2, Section 7 presents analyses that measure MEPs’ ideology in a two‐dimensional framework (economic and social left–right). The substantive findings are similar to the ones presented here. The effect of shared ideological leaning is strong for business, NGOs and trade unions, but weaker for professional associations. The prominence of an organization in a shared policy field increases the probability of recognition, and the magnitude of the effect is conditional on an MEP's ideology for NGOs and trade unions in particular.

Overall, the findings support our argument that shared preferences, together with organizational prominence amongst other groups within a shared policy area, are crucial to understand MEPs’ recognition of interest groups. Ideological affinities matter substantially more if an organization is a key, prominent actor amongst its peers. Prominence, while important even under low preference similarity, has a stronger effect on recognition when MEPs and organizations share similar preferences.

Additional analyses in Supporting Information Appendix 2 (sections 4 and 5) show that Twitter styles of MEPs and organizations and whether an organization reciprocates an MEP's Twitter‐following have no major effect on the robustness of results.

Most of our control variables are also significant covariates of interest group recognition. EU‐level organizations are more likely to be recognized. The number of Twitter‐followers an organization has, and, more importantly, the number of overall Twitter accounts followed by MEPs also influences the probability of recognition. We find a very limited effect of being a chair or vice‐chair of an EP committee. The number of MEPs’ reports and the number of terms served, both have a modest positive effect on the rates of recognition. Interestingly, the effect of plenary session attendance has quite strong negative effects on the recognition of business, but a positive effect on the recognition of NGOs. The effect for the whole sample is of limited magnitude.

Conclusion

We addressed an important question about the relationship between individual legislators and interest groups: What explains the former's decision to publicly recognize some of the latter as relevant policy actors? Using the conceptual lenses of the literature on lobbying, we discussed the importance of recognition for interest groups’ activities and ties with political elites while noting its conspicuous neglect by scholars. We showed why and how recognition is a related but separate concept from key concepts such as interest group access and prominence.

Focusing on the EP, we argued legislators’ recognition of organizations is largely driven by how organizations can help MEPs pursue their electoral and policy/office‐seeking objectives. We tested our argument on an original, built‐for‐purpose dataset with approximately 4 million observations that records recognition of more than 7,000 organizations by more than 80 per cent of MEPs that served in EP8. We proposed an innovative operationalization of recognition and validated it in line with content, face and convergent validation approaches. Analyses support our argument. MEPs are more likely to recognize organizations that help them stay in touch with constituencies from their home‐MS, and, importantly, this effect is stronger under flexible‐ and open‐list or STV electoral systems. Further, shared preferences matter, but the effect is conditional on the inter‐organizational prominence of groups in the policy domains MEPs specialize in. Compared to their leftist counterparts, more rightist MEPs are more likely to recognize prominent business groups, but less likely to recognize prominent NGOs, trade unions and professional associations. MEP ideology has weaker or no effect on the recognition of organizations with diverse or less pronounced ideological positions, such as consultancies, think‐tanks, academic institutions and subnational authorities. Conversely, inter‐organizational prominence is an important factor for recognition for almost all organizations, but the magnitude of the effect is conditional on shared preferences: stronger for rightist MEPs business and leftist MEPs‐NGOs/trade unions dyads.

Several relevant implications follow from our findings. First, they provide further evidence that electoral institutions shape MEPs’ online communication behaviour (Obholzer and Daniel Reference Obholzer and Daniel2016) and examine an important implication of this. Second, they indicate a well‐structured, along ideological lines, policy space describing the EP and MEPs’ work in specialized committees, and their links with non‐legislative actors (Beyers et al. Reference Beyers, De Bruycker and Baller2015). This presents an additional scenario about ways in which interest groups may inform decision‐makers and contribute towards ensuring some level of ideological representation of interests at EU‐level, which complements well their functional/sectoral representation mandate. Relatedly, our findings highlight interest groups’ potential to serve a geographic representation function and contribute towards strengthening the communication and electoral link between MEPs and national constituencies. Together, these findings highlight a rather versatile representation role that organizations may play through their contacts with individual MEPs. Third, our findings show that legislators’ own political goals shape the EU system of interest representation. We also show that organizational prominence of a group amongst other organizations matters greatly in getting the attention of EP legislators, similar to what Box‐Steffensmeier et al. (Reference Box‐Steffensmeier, Christenson and Craig2019) find for the US Congress. Our findings thus reinforce the image of an elite‐pluralist EU interest group system, in which a few, prominent amongst their peers, organizations manage to get recognition from decision‐makers. Fourth, our findings show that social media may play a key role in interest representation in multilevel systems of governance, and can constitute an important platform for information gathering used by legislators that goes beyond their more common use as strategic broadcasting devices during electoral campaigns (Nulty et al. Reference Nulty, Theocharis, Adrian Popa, Parnet and Benoit2016) or at specific times during the legislative cycle (Daniel et al. Reference Daniel, Obholzer and Hurka2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Elin Haugsjerd Allern, Anne Skorkjær Binderkrantz, Mihail Chiru, Bruno de Paula Castanho Silva, Thomas Däubler, Vibeke Wøien Hansen, Daniel Naurin, Anne Rasmussen, Florian Weiler, Reto Wüest and four anonymous referees for their excellent comments and feedback on previous versions of this manuscript. The authors also benefited from the feedback received as part of the PAIRDEM workshop ‘Party‐Interest Group Relationships in Contemporary Democracies’, organized at the University of Oslo, Norway, by Elin Haugsgjerd Allern in May 2019. We would like to thank Idunn Johanne Bjøve Nørbech and Soran Hajo Dahl for their excellent research assistance.

Funding information

This research received support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (ERC StG 2018 CONSULTATIONEFFECTS, grant agreement no. 804288).

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article:

Replication Data

Appendix 1: Additional information about the data