Introduction

In many ways, the golden age of legislative oversight studies was in the 1970s and the 1980s. That is when the first analytical contributions were made, stemming from the experience of congressional oversight in the United States (Aberbach Reference Aberbach1990; McCubbins & Schwartz, Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984; Ogul, Reference Ogul1976; Rockman, Reference Rockman1984). In that context, principal–agent (PA) applications to delegation and accountability became the dominant theoretical lens, focused on how parliaments can(‐not) control governments and bureaucracies through oversight activities (Kiewiet & McCubbins, Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991; Niskanen, Reference Niskanen1971; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2000; Strøm, Reference Strøm2000). One of the basic tools in the repertoire of legislative oversight is the right to ask questions to the executive, either in writing or orally in hearings and plenary debates (Pelizzo & Stapenhurst, Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2012; Yamamoto, Reference Yamamoto2007). In fact, parliamentary questions constitute a field of studies in themselves, with scholars interested in the behaviour of legislators and the reasons why members of parliaments (MPs) choose to raise specific questions (Franklin & Norton, Reference Franklin and Norton1993; Martin, Reference Martin2011a; Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2011; Russo & Wiberg, Reference Russo and Wiberg2010; Wiberg & Koura, Reference Wiberg, Koura and Wiberg1994). The connection between parliamentary questions and the ability of legislatures to control executives has always been implicit, following the logic that questions allow parliaments to ‘check, verify, scrutinise, inspect, examine, […] criticise, censure, challenge, [and] call to account’ the government and the administration (Gregory, Reference Gregory1990, p. 64).

What is less clear, however, is the extent to which parliamentary questions are effective in achieving the goal of controlling the executive. The fuzzy concepts of ‘effectiveness’ and ‘control’ make research difficult, raising problems of operationalisation and comparison across different contexts. This article seeks to advance legislative oversight studies by providing a systematic framework for the microanalysis of questions and answers (Q&A) identified in the relationship between legislatures and executives at different levels of governance. The approach is called the ‘Q&A approach to legislative oversight’ based on the premise that the study of parliamentary questions (Q) needs to be linked to their respective answers (A) in order to assess their effectiveness as a legislative oversight instrument. Drawing on insights from PA theory, the public administration literature on accountability and communication research, the framework offers a step‐by‐step guide for qualitative content analysis – specifically claims analysis – of Q&A applicable to diverse settings. A key argument is that the effectiveness of parliamentary questions depends on the (1) strength of questions asked by members of legislatures for the purposes of oversight and the (2) the extent to which executive actors respond to the questions raised. The two dimensions are operationalised and developed into six possible scenarios of oversight interactions, ranging from ‘full control’ over the executive to ‘lack of control’. The goal is to provide a theoretically and methodologically consistent toolkit for analysing and evaluating legislative oversight interactions, establishing the extent of legislative control over the executive through questions within a certain institutional setting.

To demonstrate the merits of the framework, the article uses a single case study as an illustration of the possible institutional constellations of legislative oversight, in line with the six scenarios identified. Drawing on the existing literature (Bovens, Reference Bovens2007; Kiewiet & McCubbins, Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991; Rozenberg & Martin, Reference Rozenberg and Martin2011; Strøm, Reference Strøm2000; Wiberg & Koura, Reference Wiberg, Koura and Wiberg1994), relevant variables of institutional settings are derived in order to narrow down the conditions under which the six scenarios are likely to occur. To allow the testing of more hypotheses from the literature, the focus is not on a classic legislative oversight interaction – for example, ‘Question Time’ in the Westminster system – but on the relationship between parliaments and executive actors in a context where (1) the two parties are not in a PA relationship, (2) the executive actor is an independent agency that operates in a politically salient field, while (3) the policy area is characterised by asymmetric information and collective decision making at different levels of governance. Accordingly, the case study selected illustrates the interactions between the European Parliament (EP) and the European Central Bank (ECB) in the area of banking supervision (2013–2018). The purpose of the case is to test, in an exploratory way, the expectations of the Q&A approach regarding the ‘scenarios’ of legislative oversight interactions, simultaneously inviting future applications in other contexts.

The article is structured as follows. The first section situates Q&A in the academic literature on legislative oversight, with an emphasis on PA applications and the study of parliamentary questions. The goal is to underline the necessity for a framework that empirically traces the connection between the use of parliamentary questions and the control of legislatures over executives. The second section introduces the Q&A approach to legislative oversight, explaining the logic and main tenets of the framework. To distinguish variation in degrees of control, the section also describes six scenarios of legislative oversight interactions and the likelihood that they will occur in practice, depending on different institutional settings. The third section puts forth the illustrative case study of the EP and the ECB in banking supervision in relation to one of the scenarios identified. The conclusion emphasises the contribution of the article and the lessons drawn from the specific case.

Legislative oversight from principal–agent models to parliamentary questions

In the academic literature, the notion of ‘oversight’ gained traction in the 1970s, in parallel to empirical developments in the US Congress regarding the growing importance of ‘keeping a watchful eye’ over the administration (Aberbach, Reference Aberbach1990). However, the idea of legislative oversight was hardly new; in fact, congressional oversight has always been an integral part of the American system of checks and balances (Ogul, Reference Ogul1976). The objective of oversight was to prevent abuses by the administration, including but not limited to dishonesty, waste, arbitrariness, unresponsiveness or deviation from legislative intent (MacMahon, Reference MacMahon1943, pp. 162–163). The ‘administration’ referred to different members of the executive branch, both politically appointed and part of the bureaucracy (Rockman, Reference Rockman1984). Although definitions varied, the common understanding of ‘oversight’ implied an ex post focus (‘review after the fact’), looking at ‘policies that are or have been in effect’ (Harris, Reference Harris1964, p. 9).

From a theoretical perspective, the study of legislative oversight became intertwined with PA applications to delegation in representative democracies (Kiewiet & McCubbins, Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991; Lupia & McCubbins, Reference Lupia and McCubbins1994; Strøm, Reference Strøm2000). In fact, this is how definitions of oversight came to be equated with a parliament's [mechanisms of] control over the government and the bureaucracy. The PA logic places legislative oversight as the counterpart to delegation, based on the premise that ‘A is obliged to act in some way on behalf of B’ and, in turn, that ‘B is empowered by some formal institutional or perhaps informal rules to sanction or reward A for her activities or performance in this capacity’ (Fearon, Reference Fearon, Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999). In the PA framework, B is the principal (the person or group/institution doing the delegation), whereas A is the agent (the person or group/institution acting on the principal's behalf). The chief concern of PA models is the formal incentive structure through which principals can influence the behaviour of agents and prevent agency loss (Kiewiet & McCubbins, Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991). PA models are based on rationalist assumptions of fixed preferences and self‐interested behaviour, operating in an environment of scarce information and a hierarchy of principals over agents (Niskanen, Reference Niskanen1971). These assumptions create automatic problems for legislative oversight because the preferences of principals and agents are bound to diverge over time. Agents are expected to ‘shirk’ their obligations to principals either by hiding information before they are appointed (adverse selection) or by hiding their behaviour while on the job (moral hazard) (Moe, Reference Moe1984).

To limit agency loss and increase control by the principal, the literature describes four different mechanisms. These are as follows: (1) contract design at the moment of delegation, (2) screening and selection of the agent by the principal, (3) monitoring and reporting requirements of the agent to the principal and (4) institutional checks on the agent by other veto players (e.g., courts of law) (Kiewiet & McCubbins, Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991, p. 27). The first two operate ex ante (framing the PA relationship), while the other two function ex post, ensuring ongoing oversight of the agent. Among the four mechanisms, monitoring and reporting requirements overlap most clearly with the traditional understanding of oversight. According to McCubbins & Schwartz (Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984), monitoring mechanisms can be (1) proactive and centralised (‘police patrols’), aimed at detecting and remedying violations of legislative goals or (2) reactive and decentralised (‘fire alarms’), available at the disposal of those affected in case of necessity. The centralised aspect of ‘police patrols’ is contested in the literature, taking into account that there is no parliamentary‐wide, systematic review of government measures; instead, police patrols are decentralised in committees and can often act in response to scandals inside the executive (Ogul & Rockman, Reference Ogul and Rockman1990, p. 13). Building on these tenets, many PA studies aim to outline game‐theoretic models mapping the different choices of principals and agents and the possibilities for limiting agency loss (e.g., Lupia & McCubbins, Reference Lupia and McCubbins1994).

While legislative oversight studies might have originated in the US literature, the concept can be identified all over the world, with some variation between parliamentary and presidential regimes (Strøm, Reference Strøm2000). The framework for legislative–executive relations is typically described in constitutions (or equivalent) in relation to the separation of powers, while the details of legislative oversight are stipulated in legislation and/or parliamentary rules of procedures (Yamamoto, Reference Yamamoto2007). From an organisational perspective, legislative oversight is visible in (1) committee hearings, (2) plenary hearings on specific topics, (3) the creation and functioning of commissions of inquiry, (4) the submission of written questions, as well as the use of in‐chamber (5) ‘question time’ and (6) interpellations (Pelizzo & Stapenhurst, Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2012, pp. 32–36). The availability and use of different tools depends on the jurisdiction; important factors include the legal framework of executive–legislative relations, the adequacy of parliamentary staff and research capacity, the influence of political parties and the activity of individual legislators (Ogul, Reference Ogul1976; Pelizzo & Stapenhurst, Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2012).

In sum, oversight tools allow a parliament to make demands of the executive and react to specific policies in writing or orally through reports, speeches, statements and, in direct engagement with the government or civil servants, by asking questions. In fact, the study of parliamentary questions constitutes a field of its own, with different areas of focus. In the British House of Commons, the use of ‘Question Time’ has attracted a lot of attention as a historical development (Chester & Bowring, Reference Chester and Bowring1962) in terms of why MPs ask questions and how (Franklin & Norton, Reference Franklin and Norton1993), and in relation to what type of control over the government can be exercised through questions (Cole, Reference Cole1999; Gregory, Reference Gregory1990). There is also extensive research on the practices of parliamentary questions in European legislatures, with an emphasis on the political behaviour of members who address questions (Martin, Reference Martin2011a; Russo & Wiberg, Reference Russo and Wiberg2010; Wiberg & Koura, Reference Wiberg, Koura and Wiberg1994). Although questions are almost always linked to oversight, they carry additional connotations for MPs such as self‐promotion, acting on behalf of one's constituency (Martin, Reference Martin2011b), gaining strategic advantages within one's party or competing over issues with others (Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2011; Vliegenthart et al., Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave and Zicha2013). In fact, it is widely recognised that MPs ask questions for a plurality of reasons (Wiberg & Koura, Reference Wiberg, Koura and Wiberg1994, pp. 30–31). Furthermore, examining the behaviour of MPs driving parliamentary questions contributes to the study of electoral links, government–opposition relations, and intra‐party dynamics in legislatures. But although these subjects are fascinating in themselves, they move away from the legislative oversight goal of limiting agency loss through monitoring and reporting requirements (Kiewiet & McCubbins, Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991). To put it simply, even if MPs ask questions for electoral or career gains, this does not diminish their original ‘oversight purpose’ to control the executive. After all, different motivations can be served through the same question.

From a research perspective, the challenge is to establish when a parliamentary question is effective in achieving the effect of control. So far, this methodological conundrum has been addressed by scholars in two ways. One avenue was to ask MPs, through surveys and interviews, whether the use of parliamentary questions has fulfilled their expectations of holding ministers accountable (Franklin & Norton, Reference Franklin and Norton1993). Surveys are helpful to convey perceptions of a sample of MPs regarding the usefulness of parliamentary questions; however, they risk being under‐representative owing to low participation rates (Bailer, Reference Bailer, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014, p. 186). Interviews suffer from the same problem to a higher extent, namely the inability to capture whole of parliament views about the effectiveness of oversight activities. At the same time, surveys and interviews take a snapshot of participants’ views at a certain moment in time, meaning that findings cannot cover longer legislative periods.

Another popular approach is to conduct content analyses of parliamentary questions, which aim ‘to extract meaningful content from an entire corpus of text in a systematic way’ (Slapin & Proksch, Reference Slapin, Proksch, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014, p. 128). Typical investigations include analyses of the frequency of questions on different indicators, such as government department/agency and subject matter (Cole, Reference Cole1999) or type of procedure and political affiliation of MPs posing questions (Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2011; Wiberg & Koura, Reference Wiberg, Koura and Wiberg1994). Quantitative content analysis of oral and written questions overcomes the representativeness problem of surveys and interviews; nevertheless, the method cannot capture qualitative aspects about the content of the question in terms of their suitability for oversight.

To sum up, the literature on legislative oversight is rich but simultaneously disjointed. As with many other academic subfields, scholars have been interested throughout time in different aspects of oversight – some theoretical and others empirically driven. When it comes to the study of parliamentary questions in particular, what is currently missing from the literature is a systematic analytical approach for evaluating their effectiveness in achieving control of the executive. The next section introduces such a framework.

The analytical framework: The Q&A approach to legislative oversight

To assess the effectiveness of parliamentary questions, the approach presented in this article builds on two underlying assumptions. The first is that the study of parliamentary questions cannot be separated from the study of executive answers, keeping in mind that legislative oversight presupposes a discursive exchange between two actors – the legislative and the executive. Following the convention in the literature, the ‘executive’ can refer to cabinet members (including prime ministers/presidents), politically appointed government officials in ministries or agencies, or civil servants in public administration. The legislative can include MPs (individually or in groups), a parliamentary committee or the parliament as a whole. The second assumption is that evaluating the effectiveness of parliamentary questions must be limited in scope, otherwise researchers risk getting lost in assessing the broader impact of legislative oversight on the political system (Rockman, Reference Rockman1984, p. 430). Indeed, ‘impact’ can mean different things to different people, including but not limited to changes in policy decisions, changes in the attitudes of the executive towards the legislative (e.g., more transparency) or changes in legislative oversight practices (e.g., more hearings). The problem is that such [longer‐term] effects can be caused by multiple factors that are not related to parliamentary questions. To avoid the confusion, it is proposed to limit the evaluation of parliamentary questions to their content on the one hand and their corresponding answers on the other, that is, the exchange of claims between legislative and executive actors.

Taking into account the emphasis on questions and answers as a discursive exchange, the framework is called the ‘Q&A approach to legislative oversight’. Two implications come with the label: first, that the content of Q&A in oversight interactions is essential and should be analysed in itself, and second, that the exchange of claims between legislative and executive actors is the result of ‘the actual, strategic actions of the claims makers’ (Koopmans & Statham, Reference Koopmans and Statham1999, p. 216). Indeed, legislative oversight interactions have a certain dynamic dictated by the nature of their relationship, bearing in mind that the legislative has the authority to judge the appropriateness of executive actions, while the executive has to answer to the legislative for its performance (Aberbach, Reference Aberbach1990; Kiewiet & McCubbins, Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991; Ogul, Reference Ogul1976). Q&A will thus correspondingly reflect the strategic positions of actors towards these goals. Moreover, since legislative oversight is an institutionalised process, Q&A can be found in organised hearings, meetings, and, more frequently, the exchange of documents between the two parties. Accordingly, Q&A takes the form of both verbal and written communication.

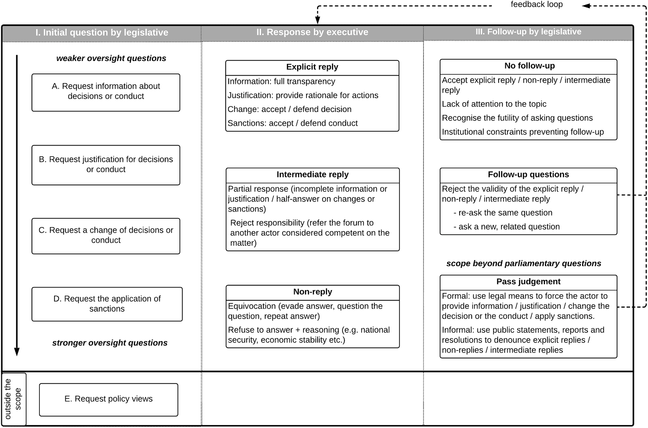

Furthermore, the Q&A approach to legislative oversight puts forth an analytical map entailing [a minimum of] three steps: (1) the legislative asks a question to the executive; (2) the executive provides an answer and (3) the legislative reacts to that response. If the legislative continues one line of questioning, there is a feedback loop back to the executive's replies. Portraying Q&A as a three‐step process is not random. In a legislative oversight interaction, not only does the legislative ask a question and the executive replies, but there is a back‐and‐forth that reveals essential information about the dynamics of oversight in a particular setting. Follow‐up questions suggest dissatisfaction with the executive's response, which is why they have to be considered separately from questions asked only once (Sánchez de Dios & Wiberg, Reference Sánchez de Dios and Wiberg2011, p. 356). Figure 1 offers an overview of the framework, which is explained below.

Figure 1. The Q&A approach to legislative oversight – a framework for analysis.

Column I enumerates the types of questions an MP can ask to the executive. Borrowing from the public administration literature, the Q&A approach to legislative oversight connects parliamentary questions to the stages of public accountability envisaged by Mark Bovens (Reference Bovens2007). The author famously defined the concept as a relationship between two parties – an actor and a forum – characterised by institutionalised mechanisms through which (1) the actor is obliged to disclose information about its activities on a regular basis, (2) the forum can interrogate the actor about the adequacy of its conduct and (3) the forum can pass positive or negative judgements on the behaviour of the actor, including through the imposition of sanctions (Bovens, Reference Bovens2007, pp. 450–451). Technically speaking, parliamentary questions are part of Bovens’ second stage because they constitute only one element of holding actors accountable. However, for the purposes of analysing parliamentary questions, the stages are extremely useful for identifying both the objectives of questions and the degree to which they challenge executive action.

Accordingly, it is posited that the legislative can make four types of requests from the executive: (A) provide information about [the context of] a decision; (B) justify a decision taken or explain conduct in a given situation; (C) amend a decision or change a conduct in a specific or general way; and (D) sanction individuals considered at fault for the negative effects of a decision or conduct. The Q&A approach to legislative oversight distinguishes demands to change decisions from requests for sanctions, keeping in mind that in PA models sanctions are the ultimate weapon of the principal (Fearon, Reference Fearon, Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999). Amendments of decisions can occur without necessarily sanctioning responsible parties for past errors. Overall, applying Bovens’ logic allows the researcher to distinguish ‘weaker’ oversight questions requesting information and justification of conduct from ‘stronger’ oversight questions demanding changes of decisions and the imposition of sanctions. In addition, there is the possibility that the legislative asks a question that is outside the scope of oversight (Figure 1, requests of type E). Examples include questions for policy views that do not challenge the executive's past decisions or conduct in any way. Indeed, not all questions are relevant for legislative oversight purposes.

Next, Column II illustrates the categories of answers provided by the executive in response to parliamentary questions. The point here is to establish the extent to which executive actors actually respond to questions, or alternatively, if they ‘evade questions and/or give insufficient responses’ (National Democratic Institute, 2000, p. 38). The classification of answers is borrowed from communication research, specifically the strand dealing with equivocation in political interviews, that is, the ways in which politicians fail to reply to questions and how (Bull, Reference Bull1994; Bull & Mayer, Reference Bull and Mayer1993). Peter Bull recently refined his ‘response typology’ for the purposes of analysing ‘Question Time’ with the Prime Minister in the House of Commons, demonstrating the applicability of his categories for judging executive answers in legislative oversight (Bull & Strawson, Reference Bull and Strawson2020). Following his typology, Column II shows that in response to parliamentary questions, the executive can provide (1) an explicit reply, (2) a non‐reply or (3) an intermediate reply.

Explicit replies show full engagement with the substance of questions. For requests for information and justification, this means offering full transparency or providing a comprehensive explanation of the rationale behind a certain decision. Likewise, when responding to requests for changes of conduct or for sanctions, executive actors can accept the request or defend the conduct in question. Explicit replies do not necessarily promise to redress a situation contested by the legislative; it may simply be that the government stands by the contested decision. For example, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, the Treasury Committee in the House of Commons held a series of hearings with the leadership of the Bank of England to discuss past errors and future reforms (2010–2012). One area of contention concerned the functions of the Court of Directors of the Bank, responsible for resource organisation (budget and appointments). In an oral testimony on 28 June 2011, the Governor of the Bank of England, Sir Mervyn King, rejected MP's Mark Garnier suggestion that the role of the Court will be to ‘run the Bank of England’; instead, he argued that the Court will ‘not be responsible and should not be responsible for policy’ because the Bank should be fully independent from political interference (House of Commons Treasury Committee, 2011, p. 126). The point of explicit replies is that they address the question head‐on, without attempts at subterfuge or by invoking reasons why parliamentary requests cannot be met.

Second, if the executive provides a non‐reply, it can do so in two ways. One is equivocation, which can mean evading an answer, questioning the question, or repeating a response from before (Bull & Strawson, Reference Bull and Strawson2020, pp. 10–11). In the same hearing from June 2011, the Governor of the Bank of England evaded a question from MP Andrea Leadsom, who contested the extent to which the Court of Directors reviewed the Bank's handling of the financial crisis. Instead of answering the question, Sir Mervyn King claimed that the Treasury Committee actually fulfilled that function by conducting ‘a permanent standing public inquiry into the financial crisis’ (House of Commons Treasury Committee, 2011, p. 129). Attention was thus deflected from what the Court should have done to direct flattery of the Treasury Committee. The other category of non‐replies concerns a clear refusal to reply accompanied by a rationale, which in legislative oversight could refer to national security, economic stability or executive actions that require secrecy. In the same hearing with the Governor of the Bank of England, MP George Mudie asked for ‘one time, one action’ when the Bank changed its conduct because the ‘Committee came across strongly on a given issue’. Sir Mervyn King answered ‘I sincerely hope that there was no action that we took that was as a direct result of what you have said because that would be to compromise [our] independence’ (House of Commons Treasury Committee, 2011, p. 131). In this context, we see that central bank independence is considered a sufficient rationale for not complying with requests for change of conduct in legislative oversight.

Finally, intermediate replies lie in‐between explicit and non‐replies. Some intermediate replies are just partial responses, providing incomplete information and justification or only half‐answering requests for changes and sanctions (Bull & Mayer, Reference Bull and Mayer1993, p. 660). In the hearing cited, an intermediate reply is provided by the Governor of the Bank of England when he acknowledges that it is essential to clearly delineate the role of the Court of Directors, but that this should be done by the legislators (House of Commons Treasury Committee, 2011, pp. 125–126). A second type of intermediate replies concerns instances of rejecting responsibility for the matter because it is not within the competence of the executive actor questioned. In the example above, Sir Mervyn King replies to questions regarding mistakes done prior to the financial crisis in banking supervision by referring to the Financial Services Authority, which was responsible for prudential supervision and financial (mis‐)conduct during the crisis. These situations should be investigated further because they can include cases of blame‐shifting or avoidance of oversight (Hood, Reference Hood2010). If the question was indeed asked to the incorrect addressee, the reply is still considered ‘intermediate’ because the legislative does not receive a full response; however, the situation is not the fault of the executive actor under consideration.

In a third step (Column III), the legislative reacts to the response of the actor by (1) providing no follow‐up, (2) asking follow‐up questions or (3) passing judgement on the actions of the executive. The reaction of the forum as ‘no follow‐up’, ‘follow‐up’ and ‘passing judgement’ can occur regardless whether the request was for information, justification of conduct, changes of policy or the application of sanctions. The lack of follow‐up can have different reasons, which are often hidden to the observer because they concern the personal motivations of legislative actors. Accordingly, a lack of follow‐up can mean that the legislative is satisfied with the answer of the executive, that public attention moved away from the topic or simply that the legislative is aware that a complete answer will never be provided – in the case of non‐replies and intermediate replies. Moreover, not all parliamentary systems allow members to ask follow‐up questions orally; this depends on each assembly's rules of procedure, which can create institutional constraints that prevent follow‐up altogether. Follow‐up questions occur for all categories of responses: explicit replies (when the legislative seeks additional information about the issue), non‐replies (when the legislative rejects the lack of answer and restates the question) and intermediate replies (when the legislative seeks a full answer either by re‐asking the same question or demanding additional information).

The final category of follow‐up reactions, namely the ‘passing of judgement’ (Bovens, Reference Bovens2007) goes beyond the scope of Q&A in legislative oversight. In fact, MPs use other parliamentary tools – not questions – to express positive or negative assessments of the executive's conduct. Such tools can be formal, for example, legislative acts that force the executive's hand in some respect, but also informal, when legislatures criticise or approve the executive's response in public statements, reports and resolutions (Bovens, Reference Bovens2007, p. 452). The challenge is to establish the extent to which these other forms of follow‐up are linked to specific parliamentary questions. In the end, the decision to include the ‘passing of judgement’ in an analysis of Q&A is an empirical question to be settled by researchers on a case‐by‐case basis.

Six scenarios of oversight interactions

Having established the main categories of Q&A, the next step is to evaluate their effectiveness. Following PA insights, the purpose of oversight is to ensure legislative control of the executive (Fearon, Reference Fearon, Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999; Lupia & McCubbins, Reference Lupia and McCubbins1994; Strøm, Reference Strøm2000). The Q&A approach to legislative oversight puts forth six scenarios capturing different dynamics of PA control – or its lack thereof. Two criteria are considered: one concerns the type of questions asked by the legislature, the other refers to the responsiveness of the executive actor providing the answer. In line with the Q&A approach to legislative oversight, requests of type A (for information) and B (for justification of conduct) are considered ‘weaker’ oversight questions, whereas requests of type C (for change of conduct) and D (for sanctions) are seen as ‘stronger’ oversight questions. In respect to the responsiveness of the executive, three patterns are possible: the actor accepts the legislative's requests for change of conduct or sanctions and promises to do better in the future (rectification), the actor explains or defends its decisions without promising any changes (justification), or the actor evades answering altogether, dodging the question from the legislative (equivocation).

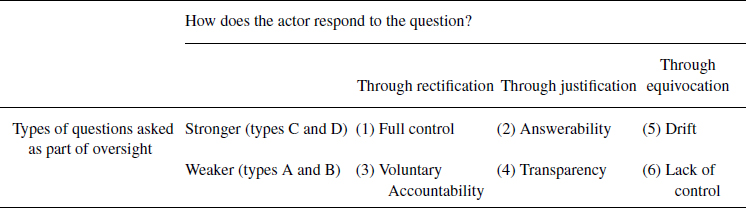

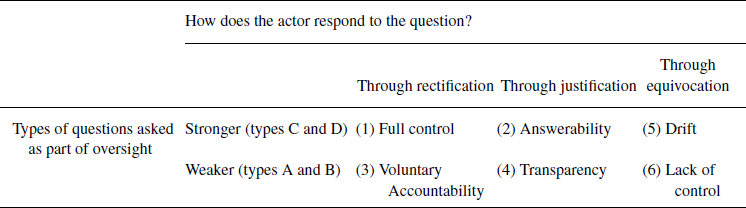

Accordingly, the effectiveness of parliamentary questions is operationalised in terms of (1) the strength of questions raised for the purposes of oversight, and (2) the extent to which the executive is ready to justify and, if needed, rectify its behaviour in front of MPs. Justification and rectification are intrinsic in many definitions of accountability (Mulgan, Reference Mulgan2000) and correspond to ‘explicit replies’ in the Q&A approach to legislative oversight; conversely, equivocation is borrowed from communication research (Bull & Mayer, Reference Bull and Mayer1993) and can be identified under ‘non‐replies’ in Figure 1. Table 1 provides a summary of the interactions between the two dimensions, creating six scenarios of legislative oversight.

Table 1. Six scenarios of legislative oversight

The numbering of the scenarios illustrates their placement on a continuum from ‘(1) Full control’ to ‘(6) Lack of control’. The order of the in‐between scenarios is complicated by the strength of parliamentary questions. Specifically, scenario ‘(2) Answerability’ indicates a higher degree of legislative control over the executive than ‘(3) Voluntary Accountability’ because rectification in the absence of strong requests for changes of conduct/sanctions is entirely dependent on the benevolence of the executive. Conversely, scenario ‘(4) Transparency’ denotes a higher degree of legislative control over the executive than ‘(5) Drift’ because a transparent executive that addresses requests for information/justification illustrates a higher degree of legislative control than an executive that evades strong parliamentary questions altogether.

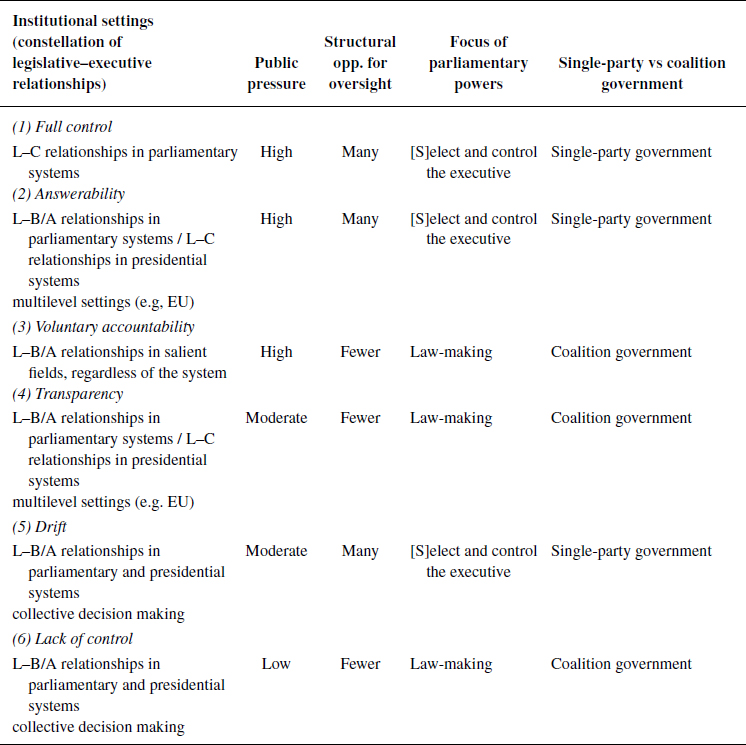

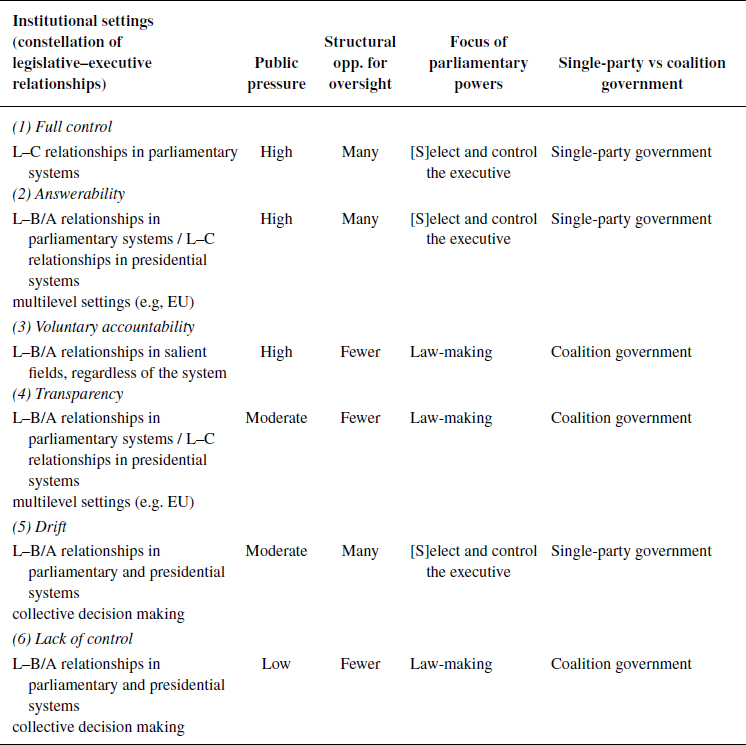

Under what conditions is each scenario more likely? The legislative oversight literature offers no encompassing explanation of the reasons behind cross‐national and cross‐temporal variation in the strength of parliamentary questions (Rozenberg & Martin, Reference Rozenberg and Martin2011, pp. 402–403). Based on empirical studies, we have however some indication of the institutional settings and legislative–executive constellations that increase the likelihood of stronger questions (types C and D). First, public pressure on an issue is essential for legislative oversight, regardless if it is triggered by ‘fire alarms’ (McCubbins & Schwartz, Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984), constituency demands (Martin, Reference Martin2011b) or general media scrutiny that allows MPs to build a reputation (Wiberg & Koura, Reference Wiberg, Koura and Wiberg1994). Second, there are structural opportunities such as the oversight mandate of the legislative, the institutional procedures available to ask questions in committee or plenary meetings and adequate staff resources supporting MPs in asking strong questions (Ogul, Reference Ogul1976; Rockman, Reference Rockman1984). In this respect, parliamentary systems have on average a greater capacity for oversight than semi‐presidential and presidential systems (Pelizzo & Stapenhurst, Reference Pelizzo and Stapenhurst2012, p. 52). Third, there is the relative strength of various functions played by parliaments, namely ‘law‐making’, the ‘ex ante [s]election of officeholders’ and ‘the ex post control of the cabinet’ (Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2011, p. 731; for a general index of parliamentary powers, see Fish & Kroenig, Reference Fish and Kroenig2009). It can thus be expected that legislatures with strong law making powers are less likely to prioritise parliamentary questions than legislatures with strong elective and control powers (Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2011). Fourth, single‐party cabinets tend to face more effective questioning procedures than coalition governments because the latter have a lower potential for confrontation (Russo & Wiberg, Reference Russo and Wiberg2010). In summary, we can expect stronger oversight questions under the following conditions: (1) high public pressure on an issue, (2) multiple structural opportunities for legislative oversight in settings where (3) parliaments have stronger elective and control functions than law‐making powers, while (4) cabinets are led by single parties rather than coalitions.

Furthermore, the oversight literature also provides some indication in respect to the likelihood for rectification, justification or equivocation in response to questions. Rectification as ‘(1) Full control’ can be anticipated in parliamentary systems where there is a direct chain of delegation between parliaments and cabinet members (Strøm, Reference Strøm2000). In contrast, rectification as ‘(3) Voluntary Accountability’ can be expected from independent agencies that seek self‐legitimation in different systems, especially when dealing with politically salient issues (Koop, Reference Koop2014; Schillemans & Busuioc, Reference Schillemans and Busuioc2015). Next, justification as ‘(2) Answerability’ or ‘(4) Transparency’ is applicable to a wide range of legislative–executive interactions regardless of the system of government; nevertheless, the two scenarios are more likely when parliaments and governments are in an indirect PA relationship in which the focus is on account‐giving rather than control (Bovens, Reference Bovens2007). Examples include legislatures and independent agencies in parliamentary systems (Thatcher, Reference Thatcher2005), legislatures and cabinets in presidential systems (Aberbach, Reference Aberbach1990; Strøm, Reference Strøm2000), as well as multilevel polities like the European Union (EU) – where the complexity of supranational organisation precludes direct PA relationships (Kassim & Menon, Reference Kassim and Menon2003). Finally, equivocation in the form of ‘(5) Drift’ or ‘(6) Lack of control’ can be predicted in two contexts. First, under conditions of asymmetric information between legislatures and bureaucracies/expert agencies, there is a higher chance that executive actors will ‘explain away’ the questions raised in any system of government (Lupia & McCubbins, Reference Lupia and McCubbins1994; Moe, Reference Moe1984). Second, when collective decisions by multiple actors at different levels of governance cannot be disentangled, the potential for blame‐shifting increases exponentially (Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2014; Hood, Reference Hood2010). Table 2 provides an overview of these expectations in connection to the conditions for stronger oversight questions outlined above.

Table 2. Institutional settings of legislative oversight scenarios: own account based on the literature

Note: Legend: L = legislative, C = cabinet, B/A = bureaucracy/agencies.

Basis in literature: public pressure (Martin Reference Martin2011b; McCubbins & Schwartz Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984; Wiberg & Koura Reference Wiberg, Koura and Wiberg1994), structural opportunities for LO (Ogul, Reference Ogul1976; Rockman Reference Rockman1984); types of parliamentary powers (Fish & Kroenig Reference Fish and Kroenig2009; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2011); single‐party cabinet as opposed to ‘coalition government’ (Russo & Wiberg Reference Russo and Wiberg2010); L–C relationships in parliamentary systems (Strøm, Reference Strøm2000); L–B/A relationships in politically salient fields (Koop Reference Koop2014; Schillemans & Busuioc Reference Schillemans and Busuioc2015); L‐B/A relationships in parliamentary systems (Bovens Reference Bovens2007); L–C relationships in presidential systems (Aberbach Reference Aberbach1990, Weingast Reference Weingast1984); L–B/A relationships in presidential systems (Lupia & McCubbins Reference Lupia and McCubbins1994; Moe Reference Moe1984).

It is anticipated that no empirical case will be a perfect match for the ideal type, but each example will be closer to one of the possible scenarios (for an elaboration of the six scenarios, see the Supporting Information Appendix). To illustrate the plausibility of the scenarios and the utility of the Q&A approach to legislative oversight, the article focuses on a case that captures three expectations outlined above: (1) it involves a parliament and an executive actor that are not in a direct PA relationship, (2) the executive actor is an independent agency that operates in a politically salient field, while (3) the policy area is characterised by asymmetric information and collective decision making in a multilevel setting. In theory, scenarios (2) to (6) could apply to the case. The Q&A approach to legislative oversight will allow the comprehensive evaluation of the example, as shown below.

Methodological considerations

The case study selected involves legislative–executive interactions between the EP and the ECB in the field of banking supervision. There are several reasons why this case is pertinent. First, the legislator (the EP) is not formally the principal of the executive agency under consideration (the ECB). Legally, the ECB was delegated to carry out banking supervision in the euro area by national governments through Council Regulation 1024/2013 establishing the Single Supervisory Mechanism (henceforth the ‘SSM Regulation’). Under a special legislative procedure, the EP – and the ECB for that matter – only have a consultative role in the process (Amtenbrink & Markakis, Reference Amtenbrink and Markakis2019). Consequently, the EP does not have the power to unilaterally act as the principal of the ECB and change its competences in banking supervision.

Second, the executive agency (the ECB) benefits from a high level of institutional independence that hinders the scope for oversight: both the EU Treaties (Article 130 TFEU) and the SSM Regulation (Article 19) prohibit the ECB from taking instructions from other EU institutions. At the same time, banking supervision is a politically salient field that was established at the EU level in the aftermath of the euro crisis with the goal to ‘sever any future link between banking sector crises and sovereign debt crises’ (Alexander, Reference Alexander2016, p. 470). Subsequently, the media and politicians kept a close eye on the ECB to check whether its supervision is actually improving the safety of the banking system. Third, banking supervision is a specialised field in which the ECB has significantly more expertise than the EP (asymmetric information); in addition, the ECB shares responsibilities for supervision with national competent authorities in the member states, creating problems of collective decision making (Maricut‐Akbik, Reference Maricut‐Akbik2020). Unlike in other legislative oversight contexts, the main tool at the disposal of the EP to control the ECB is provided by questions for oral answer with debate (Rule 128 of the EP's Rules of Procedure for the 8th parliamentary term) and questions for written answer (Rules 131 and 131a).

To investigate the exchange of questions between the EP and the ECB in banking supervision, the article proposes an adaptation of the method of political claims analysis developed in the social movements literature (Koopmans & Statham, Reference Koopmans and Statham1999). Claims analysis is a form of qualitative content analysis which combines actor‐centred and discourse‐centred approaches: in a legislative oversight context, it allows the researcher to link legislative and executive actors with the content of their interactions, including their respective positions and frames of justification used to support them. The unit of analysis is the claim, which is a sentence or a set of sentences on a particular topic. In a legislative oversight context, there is always a ‘claimant’ and an ‘addressee’ depending on the direction of communication: either the legislative asks questions to the executive, or the executive replies to the legislative. In line with Figure 1, the goal is to identify initial questions, replies, and follow‐ups in order to manually assign corresponding codes to claims made by legislative and executive actors.

For the purposes of evaluating oversight interactions, the results of the coding are aggregated in order to count the number of occurrences in each category. There are several goals to the exercise. First, one can establish the frequency of questions along different categories, capturing the inclinations of legislatures to ask ‘stronger’ or ‘weaker’ oversight questions. Second, one can identify problems in the practices of parliamentary questions, for example, asking questions outside the scope of legislative oversight or failing to follow up on non‐/intermediate replies. Third, one can detect trends in answers provided by the executive, such as tendencies to avoid substantive replies (equivocation) or to shift responsibility for the question to other actors. The idea is to empirically trace the underlying dynamics of oversight relationships and identify trends over time and across issues.

The Supporting Information Appendix provides the detailed codebook used for the case, including examples of coding and an intercoder reliability check showing that two independent human coders can understand the data in a similar way. The findings are presented in the next section.

Illustration: EP oversight of the ECB

The legislative oversight relationship between the EP and the ECB in banking supervision is regulated by the SSM Regulation and an Inter‐Institutional Agreement signed by the two institutions in 2013. In respect to parliamentary questions, members of the European Parliament (MEPs) can send written questions, to which the ECB is obliged to answer within 5 weeks; additionally, MEPs can address oral questions in ordinary and ad hoc hearings of the EP's Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) Committee, in which the Chair of the Supervisory Board participates at least three times per year (SSM Regulation, Art. 20; Inter‐Institutional Agreement between the ECB and the EP 2013, Art. 2–3). All letters exchanged between the two institutions and the relevant hearings are public and available on the websites of the institutions, which facilitated the examination presented below.

The evaluation of Q&A between the ECB and the EP in banking supervision includes the results of the claims analysis performed on 13 transcripts of hearings and 283 written letters identified between October 2013 (from the adoption of the SSM Regulation) and April 2018. Using the software ATLAS.ti, questions were coded according to their clustering around one single topic, regardless of the number of interrogative sentences involved. Accordingly, a total of 706 single‐topic questions were identified: 337 in writing and 369 orally. On average, one letter comprised two questions, while a hearing included 28 questions. The number of answers coded corresponds to the number of questions identified; when answers were absent, they were coded as non‐replies (equivocation). The full analysis is more elaborate, including figures showing the frequency of questions over time, the political affiliation of MEPs asking questions, trends in topics and differences between oral and written questions (Maricut‐Akbik, Reference Maricut‐Akbik2020). The findings presented here focus on the essence of the Q&A approach to legislative oversight, namely the categories of questions asked, and answers received in the period under investigation. The evolution of Q&A over time is shown in Supporting Information Figures A1 and A2.

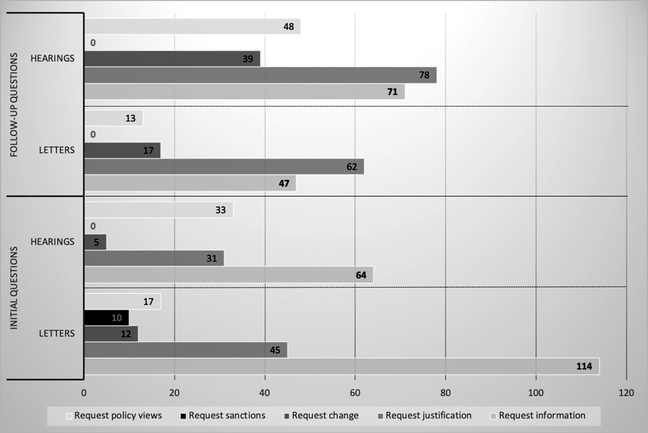

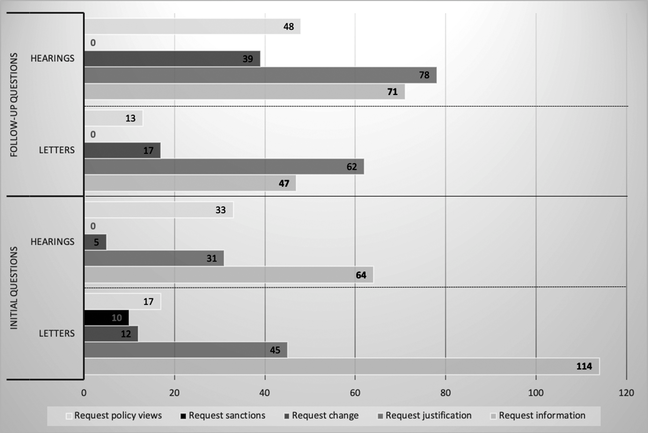

Accordingly, both oral and written questions were classified into requests for (A) information, (B) justification of decisions/conduct, (C) change of decisions/conduct and (D) sanctions. Figure 2 illustrates the results of the coding for the 56 months examined, making a distinction between questions asked for the first time and follow‐up questions raised on the same issue because MEPs wanted further information/justification of conduct or rejected the answer provided. Follow‐up questions occur more frequently in hearings than in letters, despite the fact that the EP's Rules of Procedure limit the speaking time of each MEP (see Rule 162 of the 8th parliamentary term). This suggests that when MEPs have the chance to be face to face with the Chair of the Supervisory Board, they pursue one line of questioning.

Figure 2. Categories of questions addressed by MEPs to the ECB in banking supervision, in letters and hearings (October 2013–April 2018).

In terms of categories of questions, Figure 2 shows that the majority are requests for information and justification of conduct. There is a slight difference between letters and hearings: there are more requests for information in written questions and more requests for justification in oral questions, as face‐to‐face interactions seem conducive to asking ‘why’ questions. In line with the Q&A approach to legislative oversight, both are ‘weaker’ oversight questions because they challenge executive action in a limited fashion. The low number of ‘stronger’ oversight questions is foreshadowed in the SSM legal framework and the institutional independence of the ECB. However, MEPs showed readiness to make requests for changes of decisions when they perceived that the ECB was acting outside its legal mandate, as was the case of the 2017 Addendum to the ECB guidance on non‐performing loans. The document was considered to place additional supervisory burdens on banks by going beyond the tasks assigned to the ECB in banking supervision (see public hearing on 9 November, ECON Committee 2017). Like other independent executive agencies, the ECB is supposed to enforce an existing legal framework in the SSM based on international regulatory standards (Basel III) translated into EU legislation through the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV) and the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). This means that the EP can check when the ECB is diverting from legislative intent, which is a classic goal of oversight. In fact, almost all follow‐up questions requesting changes of conduct centred on the 2017 Addendum.

Furthermore, the high number of requests for information and justification of conduct reveals a systemic problem in EU banking supervision, namely the lack of [sufficient] data about individual banks. In terms of topics, 278 out of the total 706 questions demanded increased transparency or the rationale behind specific ECB decisions on a supervised bank. While the ECB is a notoriously secretive institution in monetary policy (Curtin, Reference Curtin2017), the case for the confidentiality of supervisory decisions is defended in terms of legal provisions, trust between the supervisor and the supervisee and financial stability at large. Legally, EU bank supervisors are not allowed to disclose information that would endanger the competitive position of a bank on the market (Directive 2003/6/EC on insider dealing and market manipulation). In relation to trust, banks are more likely to share sensitive data with the supervisor if they are confident that their information will be treated confidentially. From the perspective of financial stability, liquidity problems at a bank can trigger bank runs and panic in the population, which is why the ECB argues that they should not be publicised prematurely (Gandrud & Hallerberg, Reference Gandrud and Hallerberg2018). Such confidentiality constraints are contested by MEPs and academics alike, who explain that it is impossible to assess the performance of the ECB as a bank supervisor in the absence of information about supervisory decisions (Amtenbrink & Markakis, Reference Amtenbrink and Markakis2019; Maricut‐Akbik, Reference Maricut‐Akbik2020). Consequently, questions about information and justification of conduct are bound to focus on specific banks.

An anomaly in Figure 2 is the fifth category of identified questions, which refers to instances when MEPs request policy views from the ECB on future legislation on banking supervision (a total of 111 out of 706 questions). The label describes all questions through which the EP demands the ECB's expert opinion on their ongoing legislative files. The practice seems a lost opportunity, especially since the ECB is formally required to provide written opinions on all EU legislative proposals in economic and monetary policy (European Central Bank.). Requests for policy views are more common during hearings (22% of all questions asked) than in letters (9% of all questions sent), with the additional observation that MEPs who have a leading role in the legislative process are more likely to use hearings with the Chair of the Supervisory Board to ask for expert advice on issues that interest them. Since the questions do not concern the ex post activity of the ECB in banking supervision, they cannot be considered part of legislative oversight. Unsurprisingly, the ECB replies fully to most such requests (94 out of 111 occasions).

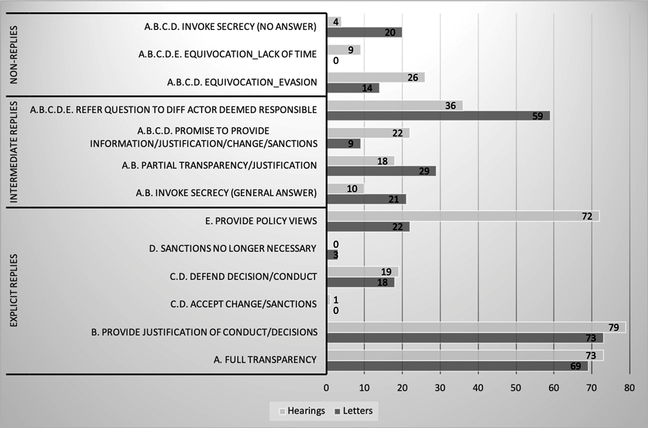

Moving to categories of responses, Figure 3 lists the number of answers identified as explicit replies, intermediate replies and non‐replies. By far, the number of explicit replies is the highest (in total 429 out of 706), suggesting the ECB's willingness to engage with the questions raised by MEPs. However, when calculated as a percentage of all questions (excluding the irrelevant requests for policy views), answers that count as explicit replies only make 47.45 per cent of the total. The next category includes intermediate replies (204 instances), the majority of which (95) refer to questions which the ECB could not answer because the issues were outside its competence in banking supervision. The problem stems from the complex multilevel system of the EU's so‐called ‘banking union’, which separates institutions for banking regulation (European Banking Authority) from banking supervision (SSM), from banking resolution (Single Resolution Mechanism, the European Commission) and thus creates confusing lines of authority (Alexander, Reference Alexander2016). Moreover, some issues still remain within the competence of national supervisors, for example, consumer protection, financial misconduct or money laundering. Such intermediate replies could be avoided if MEPs addressed questions to the relevant authority, showing comprehension of the system they helped create through legislative decisions.

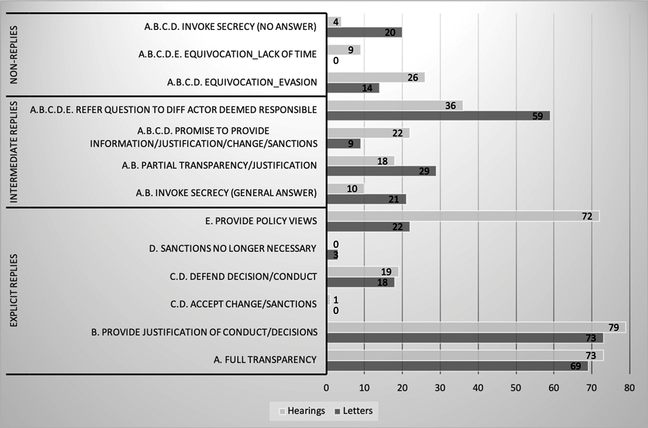

Figure 3. Categories of answers provided by the ECB to MEPs in banking supervision, in letters and hearings (October 2013–April 2018).

Figure 3 also illustrates other types of intermediate replies, namely answers that provide partial information/justification or promises to offer information/justification or implement changes in the future. An interesting category are replies that invoke secrecy but still provide a general answer (31 in total); these occur when the ECB argues that it is bound by confidentiality requirements but would still like to explain how it acts in similar situations. All answers citing confidentiality requirements refer to specific supervisory decisions or the balance sheets of individual banks, which the ECB can lawfully decline to make public. However, from the perspective of legislative oversight, such responses indicate a low degree of responsiveness from the executive – which can provide an answer that is substantively empty. Secrecy rules are a form of legally sanctioned ‘asymmetric information’, which cannot be corrected through the regular mechanisms of legislative oversight.

Most non‐replies are the result of equivocation, when the ECB evades answering oral and written questions (40 instances in total). Equivocation is more frequent in public hearings, when the Chair of the Supervisory Board uses the time allocated for answers to respond to one out of several questions addressed by a MEP. This finding is connected to the practice of asking oral questions in the EP, which structurally limits the opportunities for oversight. In line with the EP's Internal Rules of Procedure, speaking time is allocated in order of the size of political groups and in proportion to their total number of members (Rule 162 for the 8th parliamentary term). In the period under focus, MEPs from eight parliamentary groups could ask questions for a 5‐minute period; this meant that MEPs could pursue many different topics in one hearing or that topics would overlap because parliamentary groups do not coordinate with each other.

Overall, when applying the institutional settings identified in Table 2 to the case study, the results illustrate that the relationship between the EP and the ECB in banking supervision fulfil the expectations of scenario ‘(4) Transparency’. The number of Q&A identified (1,412 altogether) over the 56‐month period demonstrates, first and foremost, that the institutional infrastructure for legislative oversight is being used on a regular basis. Second, many questions are relevant for holding the ECB accountable in banking supervision, for example, requests for information and justification of conduct regarding the situation at specific banks. However, such requests rarely pass the threshold of ‘stronger’ oversight questions (for change of conduct and sanctions). Several variables contribute to this outcome, for example, public pressure on banking supervision was low in the period under investigation because the financial crisis had passed. Moreover, structural opportunities for legislative oversight in the EP are limited by the secrecy rules in banking supervision, which force MEPs to focus on transparency requests despite having the formal right and resources to pose other questions to the ECB. Moreover, the emphasis on requests for policy views shows the traditional role of the EP as a ‘law‐making parliament’, contributing actively to the legislative framework which the ECB is supposed to implement. Finally, the variable of single‐party government is not applicable to the EU; however, the large number of parties in the EP (eight in the period under focus) complicates the dynamic of oversight, as political fragmentation reduces the time for potential confrontations with the ECB during hearings.

In respect to the responsiveness of the executive actor, the majority of ECB answers are explicit replies, which suggest a clear openness towards justification and rectification of conduct (in the few cases where it was demanded). But since the ECB continues to defend strict confidentiality rules in banking supervision and refuses to change its conduct, scenario ‘(2) Voluntary accountability’ can be dismissed as characterising its relationship to the EP. Finally, the tendencies towards equivocation – while problematic – were insufficient to categorise this legislative–executive relationship as scenario ‘(6) Lack of control’. In summary, the analysis shows the case of the EP and the ECB in banking supervision as an instance of scenario ‘(4) Transparency’.

Conclusions

There are several lessons to take home from the microanalysis of Q&A between the EP and the ECB in banking supervision. From a theoretical perspective, the case study demonstrated the plausibility of the six scenarios of oversight interactions, combining insights from the oversight literature with the evaluation framework of the Q&A approach proposed in the article. The institutional setting of the EP–ECB interactions provided important clues about the likely outcome scenario: ‘stronger’ oversight questions and executive answers through rectification were structurally limited by the absence of a PA relationship between the two actors, the executive's independence vis‐à‐vis a parliament with strong law‐making powers and a fragmented party system, the asymmetry of information specific to the policy area and the nature of collective decision making in a multilevel setting. The Q&A approach to legislative oversight led to the evaluation of the case as ‘Transparency’ – a scenario that is likely to apply to other oversight interactions with similar actor constellations. In a national setting, such features are present to varying degrees in the relationship between parliaments and bureaucracies/agencies in parliamentary systems or the relationship between parliaments and cabinets/bureaucracies in presidential systems. Future research will need to establish the interaction between the different variables identified, for example, which conditions are necessary and sufficient to generate a particular oversight scenario.

Furthermore, from a methodological perspective, the case study revealed the systematicity of the Q&A approach to legislative oversight and the merits of linking the public administration literature on accountability with communication research for the purposes of investigating parliamentary Q&A. While the codebook and the intercoder reliability check in the Supporting Information Appendix are particular to the case study, they demonstrate the broad applicability of the framework. The categories of Q&A envisaged in the analytical framework are not unique to EU banking supervision; conversely, they can occur in any legislative oversight interaction. Finally, from an empirical standpoint, the case study illustrated the problem‐solving nature of the Q&A approach to legislative oversight, allowing the identification of concrete shortcomings in the oversight relationship under focus. In the case of the EP and the ECB in banking supervision, future reforms should simultaneously take into account problems of weak oversight questions and the limited responsiveness of the ECB. For scholars and practitioners interested in policy recommendations, such insights are invaluable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Mark Dawson, Ana Bobić, Alexander Akbik and the two EJPR reviewers for extensive feedback provided in the development of the argument. I am also grateful for helpful comments received at the 2018 EGPA Annual Conference and the 2018 ECPR General Conference. Special thanks to Evgenija Kröker and Harry McNeil Adams for research assistance on the case study. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Funding

This research has been supported by funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 716923).

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article:

Figure A1: Types of questions per year addressed by Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) to the ECB in banking supervision, in letters and hearings (October 2013–April 2018).

Figure A2: Types of answers per year provided by the ECB to MEPs in banking supervision in both letters and hearings (October 2013–April 2018)

Supporting Material