Since winter 2017, when Donald Trump entered the White House, there has been much discussion of the condition of democratic civil-military relations in the United States. Trump’s early adulation of “my generals,” and his decision to delegate many decisions about the use of force to the military, prompted concern.Footnote 1 At the same time, when tensions heated up with North Korea in spring 2017, and many feared that Trump’s impetuous decision-making might lead to nuclear war, informed observers questioned whether the uniformed military would or should obey the president’s direct order to launch a nuclear weapon.Footnote 2 As president, Trump repeatedly dragged the armed forces into partisan politics by addressing U.S. forces as if at a rally, and some troops responded by wearing MAGA (Make America Great Again) hats during his visits to U.S. military bases.Footnote 3 In November 2019, he jumped past the guardrails of military autonomy, overruling its decisions about personnel and justice by issuing pardons to service members convicted of or charged with war crimes and insisting that a disgraced Navy SEAL be restored to his rank and station. Amidst the protests that exploded nationwide in June 2020 over police violence toward African Americans, Trump threatened to deploy active-duty U.S. military forces on the nation’s streets. In response, many of the country’s most respected, recently retired military officers broke their silence in criticism of the president.Footnote 4 Finally, in the aftermath of his failed 2020 reelection campaign, Trump reportedly even entertained former adviser General Michael Flynn’s proposal to send the military into swing states to “rerun” the election.

Trump’s norm-breaching behavior has revived debate over classic questions about the proper policymaking roles of civilian officials and military officers. Democratic regimes in particular confront the question of “who guards the guardians”: how to ensure that the armed forces are both capable—of protecting the nation against adversaries—and subservient—to the nation’s political leaders.Footnote 5 The democratic theory of civil-military relations, in Feaver’s memorable phrase, thus insists that “civilians have the right to be wrong,” because they are much more directly accountable to the people (Feaver Reference Feaver2003, 65). Put differently, this normative stance, which is widely accepted among both senior military officers and many civilian experts, asserts that while officers have a right and responsibility to advise civilian politicians and officials, they have no right to substitute their judgment for that of civilians. The will of civilians must reign supreme.

However, we find—in a survey, conducted in June 2019 and that is among the deepest examinations to date of what Americans think about civil-military relations—that Americans do not subscribe to consensus tenets of democratic civil-military relations. Americans call for extraordinary deference to the armed forces, even on fundamental questions regarding when to use military force: if senior officers support a mission, nearly a majority of Americans would have the president approve it, even if he thinks the mission unwise, and a majority would grant the military a veto on the use of force. Whereas the traditional view enjoins officers to express their policy opinions only behind closed doors, Americans are not much bothered by the prospect of military officers, whether active-duty or retired, publicly intruding on policy debates.

One might have thought that, given the confidence huge majorities of Americans express in the armed forces, civil-military relations would be above politics. Perhaps the military would be an exception to our polarized age in which political tribalism regularly dominates ideological principle. Yet we find that political partisanship deeply informs how Americans approach the respective roles of civilian officials and military officers. Although liberals trusted the military less, they were in 2019 also more deferential to the military than were conservatives, and they even wanted the military to be more publicly vocal on policy. These views derived from partisan respondents’ trust in Donald Trump. Republicans expressed great confidence in the armed forces, but those who trusted Trump wanted his preferences to become national policy, and they opposed a politically active military. Democrats, who distrusted Trump, wanted the military to act as a check on a president they abhorred. In a multivariate analysis, respondents’ party identification and approval of Trump were strongly predictive of their deference toward the military, swamping the impact of political ideology. The impact of partisanship comes across clearly when comparing our results to a 2013 survey, when Barack Obama was president and partisan and ideological interests were aligned: Democrats then backed civilian supremacy, and Republicans called for deference.

It is generally unreasonable to expect the public’s views to be in lockstep with scholars’ normative theories.Footnote 6 But the core claim of democratic civil-military relations—that the will of elected, accountable civilian officials should prevail—follows directly from the folk definition of democracy, to which Abraham Lincoln gave voice at Gettysburg in 1863, as government “of the people, by the people, for the people.” Every American schoolchild can recite this folk definition of democracy, and therefore a U.S. public committed to democratic governance should oppose senior military officers driving the policy agenda or undermining the executive branch’s capacity to set policy, let alone having a veto on the use of force. Yet we find that many Americans, sometimes a majority, have no problem with senior military officers making critical policy decisions and injecting themselves into policy debate—contrary to Lincoln’s famous maxim.

We fill a significant gap in the field of civil-military relations. While across the world pollsters routinely ask about trust or confidence in various institutions, including the armed forces, they almost never ask more precise questions probing into the appropriate roles and limits of military officers in politics and decision-making. Perhaps, though, we need not worry much about public opinion. Perhaps scholars of civil-military relations have, for good reason, focused their analytical energies on institutions that cultivate military professionalism, socialize officers to obedience, or bolster civilians’ capacity to monitor officers and hold them accountable (Feaver Reference Feaver1999, Reference Feaver2003; Huntington Reference Huntington1957; Janowitz Reference Janowitz1960). Yet, we argue later, existing theories’ tacit premise is that, if the military is to remain within its designated bounds, the public must grasp and endorse these norms. Our article’s findings therefore raise troubling questions about the sustainability of democratic civil-military relations.

We proceed in six sections. First, we highlight the zone of normative consensus on democratic civil-military relations and explore the limits of existing scholarly knowledge of public opinion on these issues. Second, we describe the survey and its design. The next two sections unpack our two major findings. Fifth, we evaluate possible alternative explanations. We conclude by elucidating the implications for future scholarship and by addressing the findings’ linked analytical and normative challenges.

Civil-Military Relations and Public Opinion

Over six decades ago, Huntington set out an influential account of what he believed to be the defining normative challenge of civil-military relations: how to create a military powerful enough to defend the nation but still subservient to civilians. He argued that encouraging military professionalism was the surest means of keeping the armed forces focused on its expertise—the application of force—rather than competing with civilians for supremacy. Professional officers, he believed, would then have little desire to throw themselves into the political arena. In exchange, according to this “normal theory” of civil-military relations (Cohen Reference Cohen, Feaver and Kohn2001, Reference Cohen2002), drilled into generations of U.S. military officers, civilian politicians were to keep out of the officers’ domain of expertise (Huntington Reference Huntington1957).Footnote 7 While the argument for “objective control” was contested from the start,Footnote 8 the principle of civilian supremacy, which derived directly from the normative heart of democratic theory, was not. In the Huntingtonian vision, decisions regarding the use of military force would ideally arise from an iterative process of advisory collaboration between military officers and senior elected civilian politicians and appointed executive branch officials. Huntington feared that civilian, non-expert interference in military tactics and operations would harm national security, but he did not doubt their right to issue such orders, and he presumed that officers were duty-bound to obey those orders. Military officers, Finer powerfully argued, had “the right and the duty” to try “to persuade the government to their point of view” (Finer Reference Finer1962, 137),Footnote 9 but that right had to be circumscribed, to private settings—or else civilian control over policy would swiftly be rendered meaningless (Kemp and Hudlin Reference Kemp and Hudlin1992, 20–21).

Huntington’s many critics generally called for a more active and intrusive civilian role. Observing that many professional officers in modern, technologically sophisticated armed forces are more expert in fields such as logistics and cryptography than in the application of force, military sociologists questioned whether greater civilian involvement would have the detrimental impact Huntington feared.Footnote 10 Cohen argued that, in fact, the intrusion of civilian leaders into military operations had historically often been for the good (Cohen Reference Cohen2002). Rooted in principal-agent theory, Feaver maintained that civilian control of the military had long depended not on giving officers autonomy, as Huntington advised, but the opposite. Only by carefully supervising the armed forces and punishing insubordination would civilians prevent the military from departing from their will (Feaver Reference Feaver2003).

Theorists of democratic civil-military relations thus generally embrace a large zone of normative consensus (in the core text of the following bullet points) and a smaller zone of normative dispute (in parentheses). The consensus’ key propositions include:

• The judgment of civilian politicians should trump that of senior military officers regarding whether to undertake military missions. (But some argue that civilian politicians should defer to senior military officers over how to conduct military missions.)

• Military officers should express their views on military operations behind closed doors, not in public. (But some argue that they should publicly challenge patently illegal and immoral orders and that retired military officers should feel free to express their views in public.)Footnote 11

• The armed forces should be subject to substantial civilian oversight. (But some argue that civilian oversight should be less intense on matters closest to the military’s areas of professional expertise or its organizational prerogatives.)

The consensus is, moreover, reflected in the details of regional and intergovernmental organizations’ policies and nongovernmental organizations’ efforts seeking to promote “security sector reform” and “democratic control of the armed forces” around the world.Footnote 12 Some noted theorists, most famously Janowitz, asked whether the armed forces might sustain democracy by nurturing civic virtue and fostering enthusiasm for public service (Janowitz Reference Janowitz1960, Reference Janowitz1983). But while such theorists therefore took issue with the strict normative stance that the military be “apolitical,”Footnote 13 they did not take issue with the listed propositions. Burk’s insightful, sympathetic reading of Janowitz revealingly begins by implicitly endorsing the normative consensus (Burk Reference Burk2002, 8).Footnote 14 Ongoing debates about military officers’ principled resignations over policy differences—rather than illegal or immoral orders—reflect the normative consensus, with many analysts warning that the threat to resign can easily be used to subvert civilians’ will and undermine civilian control (Brooks Reference Brooks, Nielsen and Snider2009, 220–221; Feaver Reference Feaver2011, 94; Kohn Reference Kohn2002, 10).Footnote 15

The literature generally theorizes democratic civil-military relations as emerging from the preferences and power of elites, civilian and military. However, these theories all acknowledge or imply that the views of the mass public are critical. Huntington’s seminal book concludes that his recommendations are unsustainable unless the American body politic accepts that the military way of life is, and must be, distinct. America’s liberalism has been “the real problem” to “the maximizing of civilian control and military professionalism.” “Today America can learn more from West Point,” Huntington (in)famously declares, “than West Point from America” (Huntington Reference Huntington1957, 457, 464, 466). Although the text focuses largely on institutional arrangements, its final chapter revealingly puts mass culture and opinion at its analytical center. Feaver’s principal-agent theory of civil-military relations also rests on a tacit foundation of supportive public opinion. One major impediment to civilian punishment of the military, he notes, is the military’s “prestige that confers political power quite apart from any consideration of physical coercion” and its capacity to mobilize supporters in Congress and civil society (Feaver Reference Feaver2003, 88–90). Public opinion thus features in the background of Feaver’s theory: the less the public buys in to civilian supremacy, the greater are the potential costs of disciplining shirking military officers, the less likely civilians then are to punish them, and the less effectively civilian monitoring then produces military compliance. These theories’ implicit reliance on supportive mass opinion becomes explicit in Schiff’s “concordance theory,” which sees agreement among officers, political elites, and the citizenry on the military’s role as essential to forestalling the military’s intervention in politics (Schiff Reference Schiff1995, Reference Schiff2009).

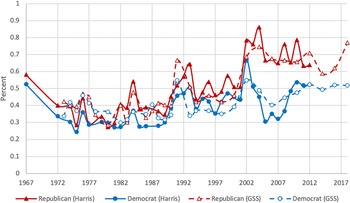

However, existing surveys of U.S. public opinion yield only limited insight into the public’s views of civil-military relations. It is well known that the American public has a great deal of confidence in the U.S. armed forces. For at least the past twenty-one years, Americans have had more confidence in the U.S. military than in any other political or social institution.Footnote 16 This trust has endured through two largely unpopular and unsuccessful wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (Burbach Reference Burbach2017, Reference Burbach2019). While Americans generally express confidence in the military, this has been especially true of Republicans—as figure 1 shows. The partisan gap grew substantially with the 2003 Iraq War, shrank at the start of the Obama administration, and then grew strikingly again after Trump’s election in 2016. But is “confidence” in the U.S. military a useful stand-in for other substantive attitudes, such as deference to the armed forces? We do not know, because pollsters have only occasionally asked more detailed questions about Americans’ views of civil-military relations.

Figure 1 U.S. public confidence in the U.S. military, 1967–2018

Note. Lines show the percentage of respondents reporting “a great deal” of confidence in the military in Harris and General Social Survey Polls. Thanks to David Burbach for sharing the data from which this figure was generated.

Studies delving deeply into U.S. public opinion on civil-military relations have been rare. Responses to occasional survey questions from the 1940s through the 1990s suggested that the mass public did not share experts’ commitment to civilian supremacy (Clotfelter Reference Clotfelter1973, 124–127; Feaver Reference Feaver2003, 40–42). However, in fall 1998 and spring 1999, the Triangle Institute posed a series of questions regarding the appropriate roles of civilian officials and military officers in decision-making and politics to a nationally representative sample of around 1,000 Americans and a convenience sample of military officers at various stages of career. This survey found that the professional military hewed more closely to democratic civil-military norms than did civilians. Just 7.9% of surveyed officers agreed to some extent that “high-ranking military officers,” not “high-ranking civilian officials,” should have “the final say on whether or not to use military force,” but 44.4% of civilians felt that way. Few military officers (12.4%) agreed that they should be allowed to “publicly criticize senior members of the civilian branch of government,” but around one-third of Americans (33.7%) thought so. The overwhelming majority of Americans—86.2%—thought it was “proper for the military to advocate publicly for the military policies it believes are in the best interests of the United States,” and almost as many—83.7%—believed that “members of the military should be allowed to publicly express their political views like any other citizen”; many officers concurred on military affairs (67.9% percent), but relatively few thought that right extended to the political arena (39.7%; Davis Reference Davis, Feaver and Kohn2001, 120–121).Footnote 17 The Triangle Institute survey, however, is over two decades old, and it was conducted at a time of great tension between civilians and uniformed military, but also of relative international calm. It is unclear whether the Triangle Institute’s findings still hold—after the United States embarked on a series of protracted wars after 2001, and after U.S. politics became far more polarized.

In 2013, as part of a larger survey, Schake and Mattis asked Americans to select one of four beliefs about civilian and military roles in the use of force. At one extreme was “when the country is at war, the President should personally direct both the broad objectives as well as the details of military plans.” At the other lay “when the country is at war, the President should basically follow the advice of the generals.” Three times as many respondents chose the latter highly deferential option (18%) as the former (just 5%). The most popular response—41%—came closest to the “normal theory” division of labor: “when the country is at war, the President should manage the broad objectives but leave the details of military plans to the generals.”Footnote 18 While this question is revealing of Americans’ views, it is limited in three respects. First, it does not probe respondents on the key issue of deference: whose judgment should determine policy when high-level civilian and military officials disagree. Second, it is framed as an ongoing military mission, and it is therefore not clear how survey-takers would respond to a prospective mission. Third, the question of civilian control is not restricted to the “objectives” versus the “details” of war-fighting, but extends to where the line is drawn between “means” and “ends” (Kemp and Hudlin Reference Kemp and Hudlin1992, 8–9). Additionally, while the authors ask other questions about civil-military relations—including military oversight, the credibility of military public information, and military endorsements of political candidates—these are often framed with respect to the mission in Afghanistan, which raises questions about these findings’ generalizability. Schake and Mattis concluded that their survey indicates that the mass public has “a strong grasp of the fundamental principles on which the American model of civil-military interaction is based” (Schake and Mattis Reference Schake, Mattis, Schake and Mattis2016a, 291).Footnote 19 Our survey’s design rectifies those limitations, and it reaches strikingly different, and less reassuring, conclusions about Americans’ adherence to those “fundamental principles” of civil-military relations.

Finally, recent experimental work has yielded important insights into the U.S. public’s deference to the military. Golby, Feaver, and Dropp find that the views of senior military leaders—particularly when they oppose a mission—impact public support for the use of force (Golby, Feaver, and Dropp Reference Golby, Feaver and Dropp2018). Employing a conjoint experimental design, Jost and Kertzer find that Americans are more likely to endorse the policy recommendations of senior military officers than of civilian experts and those of advisers with military experience than of advisers without; they further show that Americans’ respect for military officers’ opinions extends to arenas well beyond the use of force (Jost and Kertzer Reference Jost and Kertzer2019). However, neither paper confronts directly the core issue of deference: once the president has consulted with and received input about a prospective mission from senior military officers, but has nevertheless reached a different conclusion, whose view should become policy? Our survey asks respondents directly whether the military’s judgment should trump that of the president when it comes to using force.

The Survey

To assess the American public’s views on civil-military relations, we collected a sample of 1,921 U.S.-based respondents between May 31 and June 23, 2019, via Lucid.Footnote 20 Lucid supplies respondents using an iterative process that matches gender, age, education, race, Hispanic origin, state, and region to parameters from the 2015 Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.Footnote 21 The survey poses a series of questions to gauge how Americans think about civil-military relations. Per the earlier discussion, it focuses on three concepts: (a) civilian supremacy on decisions regarding the use of force; (b) the boundaries of appropriate military intrusion into policy debate in public venues; and (c) the appropriate extent and subject of civilian oversight of the military.

Civilian supremacy. To ascertain respondents’ attitudes toward civilian supremacy, we asked whether the president should approve a proposed military mission when senior military officers support the mission and, more pointedly, whether the president should approve the mission only if the president agrees with their judgment or even if the president disagrees. We also asked this question framed in the negative: whether the president should reject a proposed military mission when senior military officers object to it.

Because we wish to highlight the core dynamic of deference, we have intentionally departed from the traditional framing of survey questions about support for the use of military force. Deference to another goes well beyond due consideration of, or respect for, another’s opinion. Philosophers associate deference with denying one’s own right or capacity to make a moral judgment. When people are deferential to a particular authority, they voluntarily substitute the authority’s judgment for their own. When I am deferential to a doctor, for instance, “the doctor’s views do not outweigh mine; they replace mine” (Richards Reference Richards1964; Soper Reference Soper2002, 36 and passim). Because judges sometimes expressly defer to executive branch officials and agencies, legal scholars have considered deference, as both concept and practice. In that literature, deference means at a minimum “acceding to the views of others even when one’s own personal judgment is that the recommended action is wrong.” Put formally, “deference … involves a decisionmaker (D1) setting aside its own judgment and following the judgment of another decisionmaker (D2) in circumstances in which the deferring decisionmaker, D1, might have reached a different decision” (emphasis original; Horwitz Reference Horwitz2007–2008, 1073 and passim; Schauer Reference Schauer2008; Soper Reference Soper2002, 7).

The central issue of deference is, therefore: should the national leader substitute the military’s judgment for her own regarding whether and how to use military force?Footnote 22 Healthy democratic civil-military relations expect national leaders to consult with senior military officers before ordering the use of force, and the military’s expert advice may well influence the ultimate decision. But control is weakened if authorized civilians are expected to defer to the armed forces—that is, to replace their judgment with that of senior military officers. Other surveys—which ask respondents which adviser’s recommendations they support (Jost and Kertzer Reference Jost and Kertzer2019) or who should set the objectives and the details of ongoing wars (Schake and Mattis Reference Schake and Jim2016b), or which prime respondents about the military’s views of a prospective mission (Golby, Feaver, and Dropp Reference Golby, Feaver and Dropp2018)—do not address this central dilemma of deference.

To generate a baseline of deference to expertise, we also posed these two questions with reference to civilian advisers.Footnote 23 A third question involving military officers focused on whether the president should defer to senior military officers regarding how to employ force on the battlefield. To grasp the extent of respondents’ general inclination to defer to the judgment of senior military officers, we generated a “Deference Index” that varies between 0 and 3—with 3 representing the position of maximal deference.Footnote 24 To facilitate longitudinal comparisons, we also reproduced the 2013 Schake and Mattis question on deference.

Boundaries of advocacy. To grasp whether, on what issues, and to what extent Americans believe senior military officers should advocate publicly for particular policies, we asked respondents to express their agreement with a series of statements that varied in the advocates (senior military officers, retired senior military officers), the object of advocacy (policies not related to the military, military operations and policies), and the purpose of advocacy (in favor of certain operations and policies, against certain operations and policies).

Civilian oversight. To measure respondents’ support for civilian oversight of the armed forces, we asked respondents how intense and frequent civilian scrutiny of military decisions should be with respect to nine different issues: the defense budget, weapons development, base closures, manpower policy, sexual harassment policy, force employment, the military justice system, training, and veterans’ benefits. We created an “Oversight Index,” based on an additive measure of respondents’ expressed support for more frequent and intense oversight in each issue area.Footnote 25

In addition, we sought to identify the reasons Americans do—or do not—trust military officers, and asked respondents how much they believe military officers know about international affairs—not specifically military affairs—compared to other decision-makers. Finally, we measured common individual-level covariates—political ideology, gender, race, age, level of education, income, military service, household military service, party identification, and political knowledge. We also included versions of three well-established psychological batteries: “blind patriotism,” “right-wing authoritarianism,” and “social dominance orientation.” These are all correlated with, but distinct from, political conservatism (Schatz, Staub, and Lavine Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999; Van Hiel and Mervielde Reference Alain and Mervielde2002).Footnote 26

Finding #1: The U.S. Public’s Views Are Not in Line with Democratic Civil-Military Relations Theory

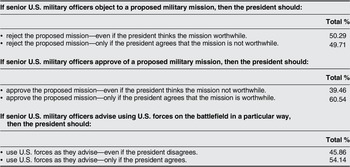

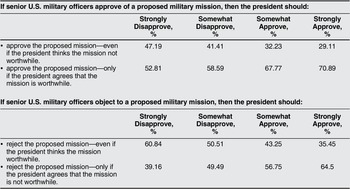

If the U.S. public adhered to the normative consensus among experts on democratic civil-military relations, large majorities would abjure deference to the armed forces and would oppose the military’s open, public involvement in policy debate. But our survey reveals that the U.S. public is out of step with these consensus principles. Consider the most basic question: who decides when to use force. Per table 1, “if senior U.S. military officers approve of a proposed military mission,” nearly 40% of respondents think the president should give his blessing “even if the president thinks the mission not worthwhile.” Even more are deferential, however, if the scenario is framed in the negative. “If senior U.S. military officers object to a proposed military mission,” over 50% of respondents think the president should reject the mission “even if the president thinks the mission worthwhile.” In sum, depending on how the question is framed, either a very substantial minority or a slim majority of Americans believes that the judgment of the professional military should replace that of the nation’s elected leader. The “normal theory” of civil-military relations would expect, and approve of, deference when it comes to battlefield tactics, yet Americans are only slightly more deferential to the military on tactical matters. “If senior U.S. military officers advise using U.S. forces on the battlefield in a particular way,” just over 45% of respondents say that “the president should use U.S. forces as they advise—even if the president disagrees.” In short, as table 1 reveals, when it comes to when and how to use military force, Americans’ views are not in line with the principle of civilian supremacy. Large numbers, sometimes a majority, think the president should override his own judgment and simply do what senior military officers want.

Table 1 Deference to the military and the use of force

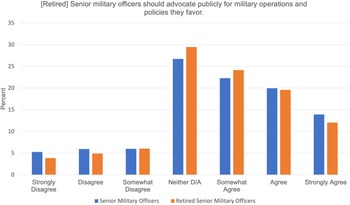

Americans also seem to have few reservations about the military’s involvement in public debate over policy. A majority of respondents—56.1%—agree to some extent that “senior military officers should advocate publicly for military operations and policies they favor,” compared to just 17.2% who disagree to any extent (figure 2). That number falls only slightly, to 50.3%, when the statement is framed in the negative: “Senior military officers should advocate publicly against military operations and policies they do not favor.” A plurality even endorses military public advocacy on matters that “they believe are in the country’s best interest, even if the policies are not related to the military”: 40.9% agree with this statement, versus 29.3% who disagree.Footnote 27 While active-duty U.S. military officers rarely express publicly their policy views, Americans are routinely exposed to retired generals praising or criticizing the nation’s elected leadership. Per figure 2, respondents draw no meaningful distinction between active-duty and retired generals in this regard. They endorse retired officers’ advocacy on military matters to roughly the same degree as they do active-duty officers (55.7% approve); on non-military affairs, their approval is moderately higher than for active duty (48.9%).Footnote 28

Figure 2 Active-duty and retired military officers and policy advocacy

While Americans trust the military, that trust does not appear to be rooted in the belief that officers are “apolitical” (contra Hill, Wong, and Gerras Reference Hill, Wong and Gerras2013; King and Karabell Reference King and Karabell2003). Consistent with past polls, just 15.9% of this survey’s respondents express any distrust of military officers.Footnote 29 However, when asked to identify the reason for their trust, just under 10% of those who trust do so because “military officers do not get involved in politics.” In fact, nearly one-quarter of respondents (23.5%) disagree with the statement, “I trust military officers because they are non-political,” and only 51.2% agree. That is far less than the support respondents give to any of the three other provided reasons for trust: professional competence, ethical commitments, patriotism.Footnote 30 In short, while the survey data suggest that Americans have only modest faith that military officers stay out of politics, that has little apparent impact on their trust in military officers.

The one area in which Americans are largely in line with traditional norms is oversight. In general, more Americans opt for the intense-and-frequent-oversight side of the scale than the light-and-occasional side. Nothing would seem to fall more within the military’s zone of professional expertise than the training of soldiers, but even here a slim plurality of respondents (42.1%) prefer more oversight, compared to 40.1% who prefer less. Even more (43.6%) want greater oversight over the use of forces on the battlefield, compared to the 36.1% who want less. Calls for frequent and intense oversight are, not surprisingly, greatest—over 60%—on widely publicized issues on which the military has seemed incapable of governing itself: sexual harassment policy and the treatment of veterans.Footnote 31 Initially, there appears to be a tension between deference and oversight: deference entails substituting officers’ judgment for that of civilians, whereas oversight implies that civilians’ judgment ultimately trumps that of officers. However, the survey’s questions do not probe deeply into why and to what degree respondents support oversight of the military. Democratic civil-military relations mandate significant oversight to ensure that military officers do not deviate from civilians’ will and to hold officers accountable if they do. But respondents who endorse deference to the armed forces may back civilian oversight to help the military honor its own commitments and standards or to promote civilian supremacy only at the extremes—such as, to prevent military disobedience of civilians’ express orders.

The next section delves into significant differences among respondents, but that nuanced analysis should not lead readers to lose sight of the disturbing big picture. A large proportion, and sometimes a majority, of Americans—across demographic and ideological groups—seem not to subscribe to the tenets of democratic civil-military relations. They are often inclined to show deep deference to senior officers’ preferences regarding not just how to employ force on the battlefield, but whether to employ force to advance national aims. Nor are they worried by the professional military’s public involvement in policy debate. By the standards of the normative consensus, Americans’ commitment to democratic civil-military relations is weak.

Finding #2: In Civil-Military Relations, Too, Politics Trumps Principle

The theory of democratic civil-military relations is expressly normative. To the extent that principle governs attitudes toward civil-military relations, so should the ideological positions that undergird people’s beliefs about politics. If that were true, political conservatives would be more deferential toward the armed forces and less sensitive to officers’ intrusion into policy debate. For conservatives, the military is the state institution that most epitomizes the ideals they cherish: in-group loyalty and integrity, self-sacrifice, and obedience to authority. People who trust an institution are also more likely to defer to its leading members’ judgment and to wish to grant that institution autonomy and to minimize intrusive oversight of it. Political liberals conversely would be less deferential to the military and more sensitive to officers’ intrusion into policy debate (Krebs and Ralston Reference Krebs and Ralston2020).

However, this survey’s bivariate results largely point in precisely the opposite direction. In June 2019, when the survey was fielded, trust in the military was, surprisingly, associated in bivariate analysis with less deference on strategic, and to a lesser extent tactical, matters. Whereas 38.4% of those who greatly trust the military believed that presidents should, regardless of their own assessment, follow senior officers’ lead in approving a proposed mission, 47.2% of those who greatly distrust the military adopted that stance. While 48.1% of extreme trusters called for deference to senior officers’ objections to a prospective military mission, a whopping 59.6% of extreme distrusters said the same.Footnote 32 On its face, this observed negative relationship is exceedingly puzzling: why were those who most trust military officers least likely to defer to their judgment?

The answer seems to be, in a word, politics. In 2019, Republicans and Trump supporters were more likely to trust the military. Consistent with their ideological predispositions, they were less likely to demand frequent and intense oversight of the military.Footnote 33 But their warmth toward the military evaporated when they realized that the preferences of the generals might trump those of Trump. Therefore, Republicans and Trump approvers adopted a relatively non-deferential attitude toward the military. They wanted Trump to have free rein, unconstrained by senior military officers. Democrats and Trump disapprovers were more likely to distrust the military, but they distrusted Trump even more. They were deferential to the armed forces because they hoped the military could act as a check on the president, whose policies they detested, whose judgment they found suspect, and whose impulsiveness they feared.

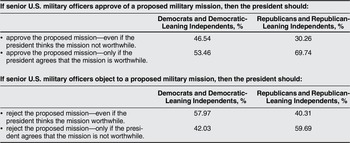

Per table 2, 46.5% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents said that, if senior U.S. military officers approve of a proposed military mission, the president should do what they say, contrary to his own judgment—compared to 30.3% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (t = –7.34; p<0.000). When framed in terms of military objection to a proposed mission, deference generally rose, but the partisan differences remained: 58.0% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents adopted the more deferential position, compared to 40.3% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (t = –7.7921; p<0.000). The U.S. public’s attitudes toward civil-military relations thus reflect the extraordinary partisan polarization of U.S. politics over the last quarter-century. It was apparently too much to hope that public opinion on the military would remain immune to these pressures (see also Burbach Reference Burbach2019; Golby Reference Golby2011, ch. 3; Robinson Reference Robinson2018, ch. 3).

Table 2 Deference to the military: Partisan comparisons

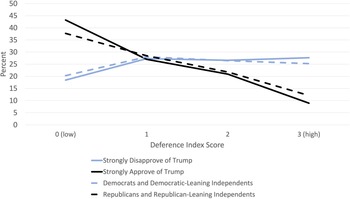

The pattern emerges even more clearly through the lens of respondents’ approval of Trump’s performance as president. As table 3 shows, respondents who strongly disapprove of the president were the most deferential to the armed forces, and those who strongly approve were the least: depending on the question, the former were 60%–80% more likely to adopt a deferential stance.Footnote 34 These results are borne out as well in the Deference Index. Figure 3 displays the stark effects that respondents’ partisan affiliations and views of the president had on their inclination to military deference: Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, along with Trump disapprovers, scored higher on the index—that is, they were more deferential to the military—than Republicans and Republican-leaning independents as well as Trump approvers.Footnote 35 These partisan effects, however, seemed to be stronger among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents, and Trump approvers, whose lines in figure 3 slope consistently downward. In contrast, the lines of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, and Trump disapprovers, slope upward, but then plateau—suggesting that they were not as prepared to sacrifice their ideological commitments and embrace deference to the military.

Table 3 Deference to the military and Trump approval

Figure 3 Deference index scores by party identification and Trump approval

The same pattern manifests in attitudes toward senior officers’ policy advocacy in the public domain. If respondents were motivated by ideology, one would expect liberals to be more critical of officers’ advocacy. This was the case in past surveys, when partisan and ideological interests aligned.Footnote 36 But, in our 2019 survey, when partisan and ideological interests were not in accord, Democrats were more likely to agree with statements endorsing military advocacy and less likely to disagree. For instance, 55.2% of Democrats agreed that “senior military officers should advocate publicly against military operations and policies they do not favor,” compared to 49.6% of Republicans; 25.5% of Republicans disagreed, compared to just 17.8% of Democrats. The same partisan pattern holds regarding whether “senior military officers should advocate publicly for policies they believe are in the country’s best interest, even if the policies are not related to the military.” Similarly, those who strongly approve of Trump as president were more likely to disagree with pro-advocacy statements and less likely to agree than those who strongly disapprove.Footnote 37 However, the effects of partisanship and Trump approval on military advocacy were not quite as clear or substantial as their effects on deference. We suspect this is because the advocacy statements never explicitly mention the president, and therefore any conflict between military and presidential preferences can only be inferred.

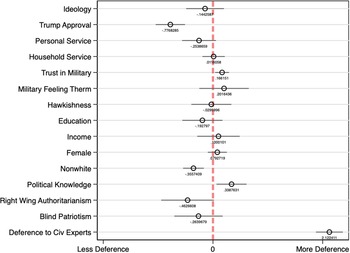

The findings on deference to the military hold in multivariate analysis. Figure 4 displays the impact of various variables on respondents’ Deference Index scores.Footnote 38 In other statistical analyses, political conservatism, Republican partisan identity, and Trump approval are all significantly associated on their own with less deference.Footnote 39 However, including either party identification or Trump approval alongside political ideology renders the latter variable insignificant.Footnote 40 In figure 4, approval of Trump has the largest negative substantive effect on deference to the military, while political ideology is statistically and substantively insignificant. Respondents’ general respect for expertise—reflected in their deference to civilian experts—has far and away the largest positive substantive effect on deference to the military. Trust in the military is consistently positive and significant—as one would expect—but its substantive effect is also small. Revealingly, right-wing authoritarians—who are especially warm toward this institution and who should be deferential to its leading members—are significantly less deferential in figure 4.Footnote 41 Among other controls, nonwhite respondents are less deferential, and politically knowledgeable respondents are unexpectedly more so. The multivariate analyses confirm that ideological commitments are not the chief drivers of respondents’ deference to the military. Partisan identity and attitudes toward the president matter more.

FIGURE 4 Predicted deference index scores: coefficient plot

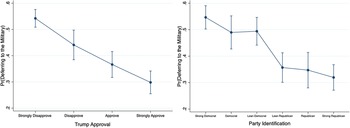

Both partisan identity and Trump approval also have substantively significant effects on deference. Figure 5 displays the probability that a respondent achieves a high Deference Index score (2 or 3), conditional on their self-reported partisan identification or Trump approval. In 2019 there was a 54% chance that a respondent who strongly disapproves of Trump would be highly deferential to the military, compared to just a 30% chance for a respondent who strongly approves. Put differently, in 2019, strong Trump disapprovers were 80% more likely to be highly deferential than strong Trump approvers. The effects were very similar with political partisanship: moving from one extreme (strongly Democratic) to the other (strongly Republican) translated into a 42% lesser likelihood of the respondent being highly deferential.

Figure 5 Probability of deferring to the military across levels of Trump approval and party identification

Note. Predicted probability (expressed as 95% confidence intervals) of scoring 2 or 3 on the Military Deference Index. The figures are based on a binary dependent variable. Models include no controls.

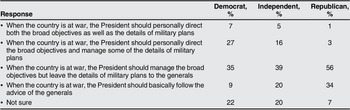

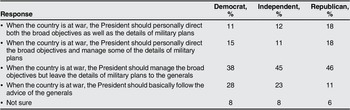

To test these claims regarding the effects of ideology and partisanship, we compared the responses to Schake and Mattis’ 2013 deference question to the replicated question in our 2019 survey. The results, in tables 4 and 5, are striking. In 2013, virtually no Republican respondents adopted a position of maximal civilian supremacy: just 1% said that “when the country is at war, the President should personally direct both the broad objectives as well as the details of military plans.” In 2019, 18% of Republicans endorsed this view. In 2013, just 9% of Democrats opted for extreme deference: “when the country is at war, the President should basically follow the advice of the generals.” In 2019, 28% of Democrats chose this option. In 2013, 34% of Republicans preferred the most deferential position, but just 11% did in 2019. In a multinomial logistic regression analysis of the 2013 results, we find that both political conservatives and Republicans were significantly less likely to select the first three civil-military alternatives relative to the last—that is, the position of greatest deference. Analysis of the 2019 results finds the inverse: both conservatives and Republicans were significantly more likely to select the first three alternatives relative to the last.Footnote 42 Conservatives’ and Republicans’ warmth toward and trust of the armed forces had not waned between 2013 and 2019—just the opposite. What had changed was the partisan affiliation of the president.

Table 4 Schake and Mattis deference question (2013)

Table 5 Replication of Schake and Mattis deference question (2019)

Alternative Explanations and Interpretations

We argue that public support for democratic norms of civil-military relations is in poor shape in the United States. Large swaths of the U.S. public seem quite willing to replace the judgment of their elected officials with that of the military and to urge military officers to wade into public debates on policy. Many Americans are unprepared to guard the guardians.

Perhaps, however, these results reflect not respondents’ deference to the military, but their hawkishness. If respondents care more about policy outcomes than about the niceties of civilian supremacy, maybe hawkish respondents wish to empower the military because they presume officers share their policy preferences. However, respondents’ hawkishness would then be a significant predictor of their answers to the three individual deference questions. Yet that is not the case: hawks are not significantly more supportive of the president overruling the military when he approves of the mission, nor are they significantly more deferential to the military when its leadership supports using force.Footnote 43

Perhaps, though, hawkish respondents’ predilection for employing force helps explain why they “flip” from a non-deferential stance (when senior U.S. military officers object to the mission) to a deferential one (when senior U.S. military officers approve of it). Indeed, we find that hawkishness is a significant predictor of “flipping.” However, even in these cases, respondents’ attitudes toward the president and political ideology remain significant: hawks who strongly approve of Trump and who self-identity as conservatives are more likely to remain consistently non-deferential to the military. Moreover, respondents’ dovishness does not seem to help explain why some “flip” from a non-deferential stance (when senior U.S. military officers approve of the mission) to a deferential one (when senior U.S. military officers object to it).Footnote 44 In short, the effects of hawkishness are highly circumscribed, and deference to the armed forces is independent of respondents’ general attitudes toward the use of force.

Alternatively, perhaps Americans’ deference to the armed forces reflects the reality that military service today is distant from most Americans’ lives.Footnote 45 This claim implies that those more familiar with the military—veterans and maybe their family members—should adhere more closely to the normative ideal. However, our survey data do not support this alternative explanation. We find that veterans are as deferential as non-veteran civilians to senior military officers regarding when to use force; they are less deferential only regarding how to use force. In other words, their view—even more than that of civilians—is antithetical to the “normal theory” of civil-military relations.Footnote 46 Veterans are also significantly less supportive of oversight of the military—again contrary to civil-military norms.Footnote 47 Meanwhile, the views of military household members are, generally speaking, indistinguishable from those of other civilians on critical questions of deference to and oversight of the military.Footnote 48

We have further argued that political loyalties—more than ideology—significantly shape attitudes toward civil-military relations. Perhaps, though, members of the U.S. public have become deferential to the armed forces out of a different principled commitment: left-liberal Americans in particular may have believed in 2019 that Donald Trump represented a singular threat to democratic norms, and they may therefore have turned to the military as a backstop to democratic backsliding. We are skeptical, however, of this Trump-as-threat-to-the-republic alternative explanation. First, concern about the health of the nation’s democratic institutions has long been related to party affiliation—as far back as 1996, when the American National Election Study first started asking people if they were “satisfied with the way democracy works in the United States.” In general, those whose party won the last presidential election think U.S. democracy is in better shape than those whose party lost.Footnote 49 Weak faith in democracy’s present practice may be another mechanism through which partisan politics shape attitudes toward civil-military relations, but it is not an independent explanatory account.

Second, while this alternative explanation may conceivably shed light on why Democrats and Trump-disapprovers were more deferential to the armed forces in 2019 than in 2013, it cannot explain why Republicans and Trump-approvers became less deferential over that span. By its logic, the many Republicans who believe the Trump administration a stalwart defender of democracy had no reason to shift their view of civil-military relations. Moreover, as noted earlier with reference to figure 3, the Trump-threat argument would expect the strongest partisan effects to be concentrated among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents. Yet we find the opposite. These respondents are ambivalent about deferring to the military; as a result, they are evenly spread across three of the four levels of the Deference Index. Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are far less equivocal, contrary to this alternative argument.

Perhaps though a different principled commitment underlies these results: maybe many respondents welcome senior officers’ open intervention in policy debate because they believe deeply in democratic deliberation and transparency, wish to be better informed, and therefore want to hear from all relevant parties, including military officers. Were this the case, liberals, who more deeply value liberal-democratic institutions,Footnote 50 would be more supportive of officers wading into public policy debates. Conservatives, who rank higher on the authoritarianism and blind-patriotism scales (Schatz, Staub, and Lavine Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999, 167; Van Hiel and Mervielde Reference Alain and Mervielde2002, 969), and authoritarians and nationalists, who place relatively little value on democracy, would be less supportive (de Figueiredo and Elkins Reference de Figueiredo, Rui and Elkins2003, 177, 179). This is precisely what we find: liberals and Democrats were more supportive in 2019 of officers’ public policy advocacy. Note that this unusual interpretation of liberals’ preferences means that partisan and ideological interests aligned in 2019, making it impossible to separate the two accounts. However, if we are right, after Democrat Joe Biden entered the Oval Office in January 2021, Democrats’ views of military intrusion into policy debate would shift—whereas, by this ideological account, they would not. Moreover, our political account seems more plausible because Democrats in 2019 supported deference toward the military, and it is extremely hard to square that deferential stance with any variant of liberal ideology.

Conclusion

Even the widely trusted U.S. military cannot escape the nation’s deeply polarized politics. Although Americans of all stripes generally hold the armed forces and its officers in high regard, partisanship is now—and perhaps has long been—a key driver of Americans’ attitudes on these basic questions. Principled devotion to democratic civil-military relations, we have discovered, is rare, and in 2019 Trump’s supporters were oddly less deferential to the military—and more in line with the civil-military normative consensus—than were his detractors. If a more “normal” Republican had ascended to the presidency in 2016, would we have witnessed the same shift toward military deference among Democrats? We suspect so, though our data cannot offer a conclusive answer. At least now, thanks to this article, we are asking the question. We make one strong prediction: with Democrat Joe Biden in the White House since January 2021, we expect partisans’ stances on deference and military politics to flip yet again.

What is to be done? The answer depends on why Americans’ normative views of civil-military relations diverge so dramatically from what democratic theory demands. This is an important research question, about which we can only speculate. Perhaps the problem lies partly in civics training. It seems likely that few Americans have thought deeply about how to guard the guardians. As much as military officers need to have proper norms of democratic civil-military relations inculcated, so does the average citizen. Democratic civil-military relations should, like the separation of powers, be a part of every high school civics class and indeed of citizens’ lifelong civics education.Footnote 51 However, we are wary of putting too much weight on socialization. If socialization were so powerful, then veterans would be stronger proponents of democratic civil-military relations, yet as discussed earlier, our evidence runs contrary to this claim.Footnote 52 Recent survey data show that even West Point cadets, despite their intense and active socialization, do not endorse the principles of civilian supremacy (Brooks, Robinson, and Urben Reference Brooks, Robinson and Urben2020). Lifelong education in democratic civil-military relations can help, but its absence is probably not responsible for our current straits.

More likely a significant part of the problem lies in rampant militarism in modern America, sustained by the nation’s elites. Militarism is woven into America’s everyday practices and national rituals as well as its political discourse (Bacevich Reference Bacevich2005; Enloe Reference Enloe2000; Lutz Reference Lutz2001; Mann Reference Mann1987; Millar Reference Millar2019b): politicians routinely and exclusively narrate soldiering in terms of heroism, sacrifice, and patriotism, rather than professionalism, and they regularly declare their “support for the troops,” even when criticizing ongoing missions (Krebs Reference Krebs2009; Millar Reference Millar2019a). Deference to the military may derive from a deep tension between this dominant militaristic public narrative of soldiering and the modern military’s market-based mode of recruitment. In the age of the conscripted mass army, the citizen-soldier willingly performing his duty thereby demonstrated his civic virtue, but he was no more virtuous than the millions of others who obeyed the call to the colors. When the draft ended, soldiers’ reputation for virtue should have evaporated. The contracted professional may be highly skilled, but she is not virtuous. But the militaristic public narrative, by affirming that the citizen-soldier was embodied in the professional soldier, transformed the latter into a figure that combined both extraordinary virtue and great expertise. Our survey finds that belief in the U.S. officer corps’ patriotism and competence is axiomatic in modern America. Very few question that “military officers put the interests of the country first,” and even fewer think they are “not good at what they do.”Footnote 53 The combination is formidable. A patriotic officer’s heart is in the right place, but good intentions are never enough. A competent officer’s professional judgment should be carefully weighed, but she may also be corrupt. However, if officers are unusually patriotic and unusually competent, and if politicians and bureaucrats are venal or ignorant, it is no wonder that many Americans are convinced that the preferences of officers should govern and that officers should freely and publicly weigh in on policy matters.

Building public support for democratic civil-military relations must start with brave leadership challenging the nation’s militarist hegemony. Rather than encourage unquestioning deference to the military, politicians should model respectful skepticism. Rather than reflexively thanking soldiers for serving heroically, politicians should thank them for serving democratically—that is, for obeying the will of the people and their elected representatives. Rather than reproduce the mythology of the citizen-soldier, politicians should speak more honestly about what drives soldiers and officers, about their foibles as well as their strengths. Politicians may even find that the nation’s military men and women would welcome being taken down a notch.Footnote 54

But brave leadership will not suffice to securely install civilian supremacy. Militarism’s firm grip will be loosened only if there is also change from below. Democracy demands a certain degree of popular civic virtue. As the perfectly named U.S. federal judge Learned Hand warned, amidst the Second World War, “liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it” (Hand Reference Hand1977, 190). So does civilian control over the military.

Acknowledgment

For helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this article, the authors are grateful to audiences at Bar Ilan University, the London School of Economics, and the 2019 Conference of the Inter-University Seminar of Armed Forces and Society. They also thank, for their comments, Mark Bell, Avishay Ben Sasson-Gordis, Lindsay Cohn, Jonny Hall, Kate Millar, Mike Robinson, Chiara Ruffa, Jennifer Spindel, Jeremy Teigen, and Ariel Zellman. Finally, they thank the University of Minnesota, through its Grant-in-Aid of Research, Artistry, and Scholarship program, for its support of this research.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. 2019 Lucid Data and Analyses

Appendix 2. TISS and ANES Supplementary Analyses

Appendix 3. Survey Instrument

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592721000013.