1. Introduction

Copper (Cu) is an essential mineral nutrient that readily cycles between the Cu2+ and Cu+ oxidation states. This redox flexibility allows Cu to serve as a cofactor in key metabolic enzymes involved in electron transfer reactions and essential biological processes such as photosynthesis, respiration and oxidative stress scavenging (reviewed in Broadley et al., Reference Broadley, Brown, Cakmak, Rengel, Zhao and Marschner2012; Burkhead et al., Reference Burkhead, Gogolin Reynolds, Abdel-Ghany, Cohu and Pilon2009; Ravet & Pilon, Reference Ravet and Pilon2013). In plants, Cu also plays roles in cell wall lignification, pathogen resistance and reproduction (reviewed in Rahmati Ishka et al., Reference Rahmati Ishka, Chia, Vatamaniuk and Upadhyay2022). Beyond its static role as an enzyme cofactor, labile (loosely bound or bioavailable) Cu acts as a dynamic signalling metal and metalloallosteric regulator, increasingly recognized in cell proliferation and death pathways in animal systems (Chang, Reference Chang2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Min and Wang2022; Ge et al., Reference Ge, Bush, Casini, Cobine, Cross, DeNicola, Dou, Franz, Gohil, Gupta, Kaler, Lutsenko, Mittal, Petris, Polishchuk, Ralle, Schilsky, Tonks, Vahdat and Chang2022; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yang, Yu, Jin, Nie, Zhang, Ren, Ge, Zhang, Ma, Dai, Sui and Teng2025). While the signalling functions of labile Cu in plants are less explored, Cu+, the predominant form in the reducing environment of the cytosol, is essential for ethylene and salicylic acid perception and signalling, highlighting Cu as a dynamic and compartmentalized signal involved in developmental transitions and environmental responses (Azhar et al., Reference Azhar, Abbas, Aman, Yamburenko, Chen, Muller, Uzun, Jewell, Dong, Shakeel, Groth, Binder, Grigoryan and Schaller2023; Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Esch, Hall, Binder, Schaller and Bleecker1999; Schott-Verdugo et al., Reference Schott-Verdugo, Müller, Classen, Gohlke and Groth2019; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhang, Chu, Boyle, Wang, Brindle, De Luca and Després2012). Recent studies also suggest that Cu can act as a systemic signal or influence an unidentified systemic signal in long-distance shoot-to-root communication of plant Cu status under varying environmental and developmental contexts (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023).

Cu redox activity, however, poses toxicity risks, as its ability to accept and donate electrons can generate adventitious electron transfers to oxygen, causing oxidative stress (Ravet & Pilon, Reference Ravet and Pilon2013). Moreover, Cu2+ forms exceptionally stable complexes with organic ligands, as explained by the Irving–Williams series (Ca2+/Mg2+ < Mn2+ < Fe2+ < Co2+ < Ni2+ < Cu2+ > Zn2+), which ranks the relative stability of divalent metal-ligand complexes and highlights Cu2+ as the strongest binder among biologically relevant metals; this high Cu2+-ligand stability can lead to mismetalation and protein inactivation (Festa & Thiele, Reference Festa and Thiele2011; Irving & Williams, Reference Irving and Williams1953; Martin, Reference Martin1987; Osman & Robinson, Reference Osman and Robinson2023). Consequently, although total intracellular Cu may be in the micromolar range, the vast majority exists tightly bound to proteins and various cellular ligands, with the labile Cu pool estimated to be in the femto- to zeptomolar range (Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Lee and Chang2017; Hong-Hermesdorf et al., Reference Hong-Hermesdorf, Miethke, Gallaher, Kropat, Dodani, Chan, Barupala, Domaille, Shirasaki, Loo, Weber, Pett-Ridge, Stemmler, Chang and Merchant2014). Intracellular Cu trafficking is mediated by chaperone proteins that ensure accurate metalation via protein-protein interactions and ligand exchange, preventing free cytoplasmic Cu ion exposure during transit (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Jones and Dameron1999; Meiser et al., Reference Meiser, Lingam and Bauer2011; Rahmati Ishka et al., Reference Rahmati Ishka, Chia, Vatamaniuk and Upadhyay2022; Riaz & Guerinot, Reference Riaz and Guerinot2021; Wairich et al., Reference Wairich, De Conti, Lamb, Keil, Neves, Brunetto, Sperotto and Ricachenevsky2022).

Historically, Cu was not among the earliest bioavailable metals; it became biologically indispensable with the rise of photosynthetic organisms and the oxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere over 2.33 billion years ago (Bekker et al., Reference Bekker, Holland, Wang, Rumble, Stein, Hannah, Coetzee and Beukes2004; Burkhead et al., Reference Burkhead, Gogolin Reynolds, Abdel-Ghany, Cohu and Pilon2009; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Ono, Beukes, Wang, Xie and Summons2016; Poulton et al., Reference Poulton, Bekker, Cumming, Zerkle, Canfield and Johnston2021). As atmospheric oxygen increased, iron (Fe), once dominant in early biochemistry, became less soluble due to Fe3+ oxide formation, whereas Cu2+ became more bioavailable, liberated from insoluble Cu+ sulphide salts in oxygenated soils and waters (Burkhead et al., Reference Burkhead, Gogolin Reynolds, Abdel-Ghany, Cohu and Pilon2009). This environmental transition likely drove the evolution of Cu-dependent metalloenzymes and laid the foundation for the increasingly recognized, although not fully explored, intricate crosstalk between Cu and Fe homeostasis and their metabolic networks. The hallmark of this crosstalk is the increased uptake of Fe under Cu deficiency and vice versa, reciprocal regulation of some of Cu-responsive genes under Cu or Fe deficiency, modulation of Cu homeostasis through a Cu economy/metal switch component, and finding that Cu and Fe can partially substitute each other in long-distance signalling (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Ping, Zhao, Li, Li and Liang2024; Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023; Chia & Vatamaniuk, Reference Chia and Vatamaniuk2024; Kastoori Ramamurthy et al., Reference Kastoori Ramamurthy, Xiang, Hsieh, Liu, Zhang and Waters2018; Pätsikkä et al., Reference Pätsikkä, Kairavuo, Sersen, Aro and Tyystjärvi2002; Waters et al., Reference Waters, McInturf and Stein2012; Reference Waters, McInturf and Amundsen2014; Waters & Armbrust, Reference Waters and Armbrust2013; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Li, Hu, Wang, Fang, Wang and Shou2023). A detailed analysis of Cu–Fe crosstalk is beyond the scope of this review and is available in (Wairich et al., Reference Wairich, De Conti, Lamb, Keil, Neves, Brunetto, Sperotto and Ricachenevsky2022; Reference Wairich, Lima-Melo, Menguer, Ortolan and Ricachenevsky2025).

Total soil Cu levels typically range from 2 to 100 mg/kg, but its bioavailability is controlled by complex physicochemical interactions, so only a small fraction is accessible for plant uptake (Alloway, Reference Alloway2013; Kabata-Pendias, Reference Kabata-Pendias2000; McBride, Reference McBride1994; Shorrocks & Alloway, Reference Shorrocks and Alloway1988). Soil pH is a major determinant, with acidic soils increasing Cu solubility and alkaline soils promoting insoluble Cu compound formation, thereby reducing bioavailability (Alloway, Reference Alloway2013; McBride, Reference McBride1994). Considering the tightness of Cu binding to organic matter, Cu bioavailability in organic soils is limited (Irving & Williams, Reference Irving and Williams1953; McBride, Reference McBride1994; Mitra, Reference Mitra2015; Shorrocks & Alloway, Reference Shorrocks and Alloway1988). Clay minerals and soils with high cation exchange capacity adsorb Cu, further immobilizing it and limiting uptake (McBride, Reference McBride1994). Additionally, redox conditions play a role in Cu bioavailability in soils: under waterlogged, anaerobic conditions, Cu may precipitate as Cu-sulphide (CuS), further decreasing its availability (McBride, Reference McBride1994). These factors, along with agricultural practices such as the use of Cu-based fungicides and fertilization regimes, contribute to the dynamic behaviour of Cu in the soil-plant continuum. This review focuses on how plants harness Cu biochemical properties by utilizing a sophisticated Cu homeostatic system that regulates uptake, cellular trafficking, tissue distribution, storage and utilization. We also explore the differences in Cu uptake strategies between grasses and non-grass species, the proposed mechanisms of Cu sensing and emerging evidence for systemic Cu status signalling.

2. Overview of Cu homeostasis in plants

2.1. Cu uptake and long-distance transport in dicots and non-grass monocots

Copper predominantly exists as Cu(II) in aerated soils, where it forms complexes with organic matter, Fe and aluminium (Al) oxides. Thus, Cu must be mobilised before root uptake (Flemming & Trevors, Reference Flemming and Trevors1989). In Arabidopsis thaliana, a model dicot, Cu(II) is proposed to be reduced to Cu(I) before uptake, which is a mechanism likely shared by other dicots and non-grass monocots (Burkhead et al., Reference Burkhead, Gogolin Reynolds, Abdel-Ghany, Cohu and Pilon2009) and (Figure 1). This reduction is mediated by FRO4 and FRO5, members of the ferric reductase oxidase (FRO) family of membrane-bound enzymes. Following reduction, Cu(I) is transported into root epidermal cells mainly via the copper transporter (COPT) family. AtCOPT1 and AtCOPT2 facilitate high-affinity Cu(I) uptake (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Casero, Singh, Wilson, Grande, Yang, Dodani, Pellegrini, Huijser, Connolly, Merchant and Krämer2012; Gayomba et al., Reference Gayomba, Jung, Yan, Danku, Rutzke, Bernal, Kramer, Kochian, Salt and Vatamaniuk2013; Jung et al., Reference Jung, Gayomba, Rutzke, Craft, Kochian and Vatamaniuk2012; Kampfenkel et al., Reference Kampfenkel, Kushnir, Babiychuk, Inzà and Van Montagu1995; Sancenon et al., Reference Sancenon, Puig, Mira, Thiele and Peñarrubia2003). In addition, AtZIP2, a member of the ZIP family better known for Zn and Fe transport, is transcriptionally upregulated under Cu deficiency (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Casero, Singh, Wilson, Grande, Yang, Dodani, Pellegrini, Huijser, Connolly, Merchant and Krämer2012; Wintz et al., Reference Wintz, Fox, Wu, Feng, Chen, Chang, Zhu and Vulpe2003; Yamasaki et al., Reference Yamasaki, Hayashi, Fukazawa, Kobayashi and Shikanai2009; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Chia, Sheng, Jung, Zavodna, Zhang, Huang, Jiao, Craft, Fei, Kochian and Vatamaniuk2017) and (Figure 1). Recent studies in A. thaliana revealed that ZIP2 localizes primarily to root epidermal cells, with additional signal detected in the vasculature of transgenic plants expressing a ZIP2 genomic fragment fused to mCitrine. zip2 mutants are hypersensitive to Cu deficiency and accumulate less Cu in both roots and shoots, supporting a role for ZIP2 in Cu acquisition at the root periphery and possibly in Cu partitioning between roots and shoots (Robe et al., Reference Robe, Lefebvre-Legendre, Cleard and Barberon2025).

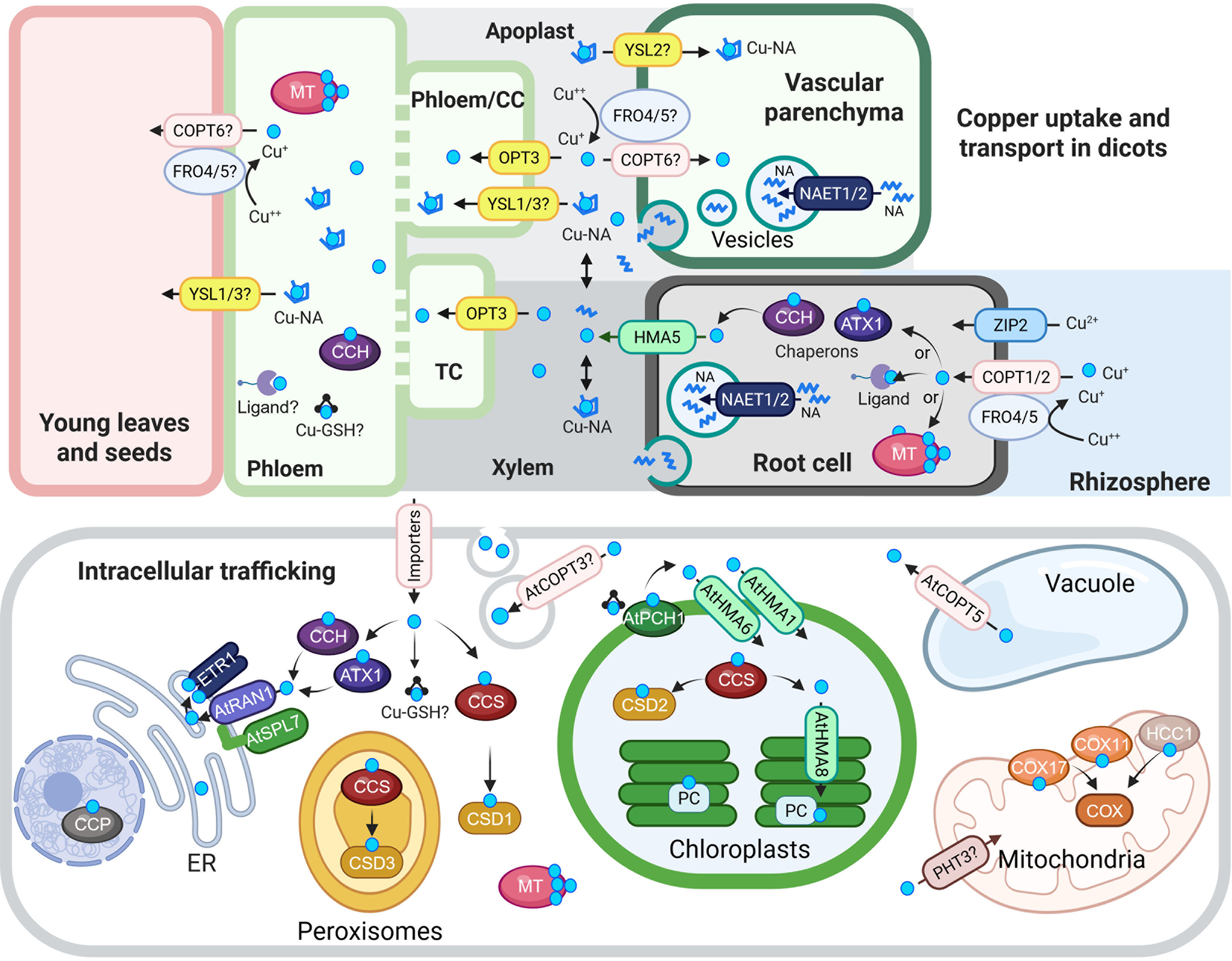

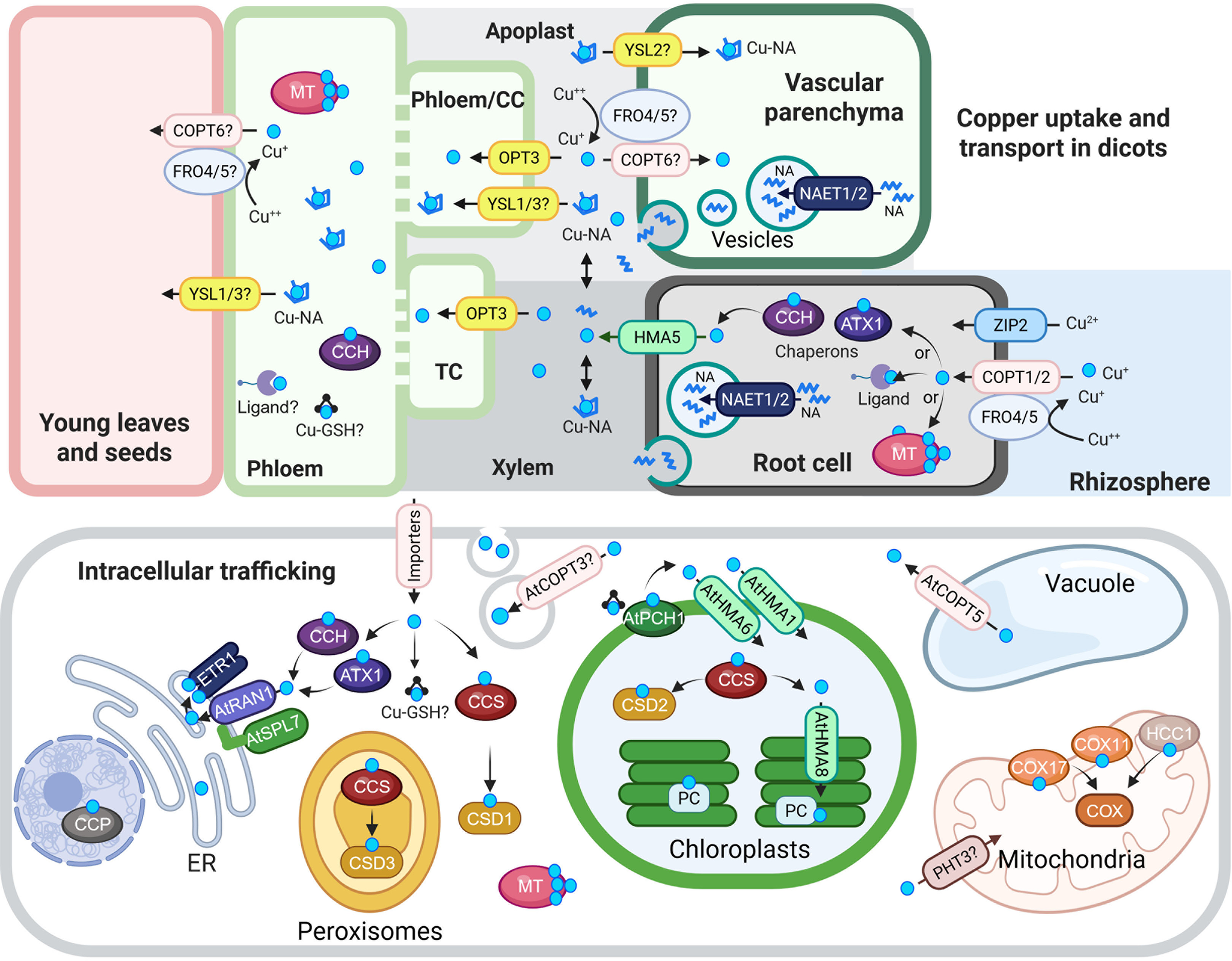

Figure 1. Cu uptake, transport and intracellular trafficking in dicots.

Top panel: Cu uptake and long-distance transport. At the root surface, Cu(II) is reduced to Cu(I) by AtFRO4 and AtFRO5, then imported into cells via AtCOPT1 and AtCOPT2, members of the CTR/COPT transporter family. AtZIP2 serves as an alternative Cu(II) uptake route. Once inside root cells, Cu is loaded into the xylem via AtHMA5, a member of the HMA family of P-type ATPases. Nicotianamine (NA), synthesized in the cytoplasm, is transported into secretory vesicles by AtNAET1/2, then secreted into the xylem apoplast, where it chelates Cu to form Cu-NA complexes. These complexes are carried to the shoot with the transpiration stream. Cu or Cu-NA may be reabsorbed from the xylem apoplast into xylem parenchyma cells via AtCOPT6 and possibly AtYSL2, both expressed in the vasculature and proposed to mediate lateral mineral movement. In the phloem apoplast, Cu or Cu-NA is taken up by AtYSL1/3 or directly by AtOPT3, which mediates Cu loading into phloem companion cells. Although AtFRO4/5 are expressed in the shoot, their role in Cu(II) reduction in the shoot remains unconfirmed. Once in the phloem, Cu transport to sink tissues may involve metallothioneins (MTs), glutathione (GSH) and the Cu chaperone CCH.

Bottom panel: Intracellular Cu trafficking. After entering the cytosol, Cu is buffered and distributed by chaperones, ligands, MTs and GSH. At the chloroplast membrane, AtPCH1 delivers Cu to AtHMA1 and AtHMA6, which import Cu into the stroma. There, AtCCS loads Cu onto Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase (AtCSD2). AtHMA8 then transfers Cu into the thylakoid lumen, where plastocyanin (PC) acquires it. AtPHT3 family transporters may deliver Cu to the mitochondria, and AtCOX11, AtCOX17 and AtHCC1 facilitate its insertion into COX. AtCCS also delivers Cu to CSD1 and CSD3, Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase isoforms in the cytosol and peroxisomes, respectively. In the vacuole, excess Cu is stored and exported to the cytosol by AtCOPT5, a tonoplast-localized transporter. ATX1 and CCH deliver Cu to RAN1/AtHMA7 on the ER membrane. RAN1/AtHMA7 interacts with AtSPL7; this interaction is speculated to modulate Cu transfer to ETR via RAN1. AtCCP is proposed to be a nuclear Cu chaperone required for plant immunity. Finally, AtCOPT3 associates with secretory vesicles and may participate in Cu mobilization during reproduction.

In the schematic, Cu(I/II) ions are indicated by cyan circles unless otherwise noted. Transporter families are color-coded: CTR/COPT in pink, HMA in green and YSL in yellow. Abbreviations: CC, companion cells; TC, phloem companion cells that de-differentiated into transfer cells; NA, nicotianamine, ER, endoplasmic reticulum; CCS, Cu chaperone for superoxide dismutase; ATX1, antioxidant protein 1; CCH, ATX1-like Cu chaperone; MT, metallothionine; GSH, glutathione; PCH, plastid chaperone 1; PC, plastocyanin. COX, cytochrome c oxidase. ETR1, ethylene response 1. CCP, copper chaperone protein. The figure was created with BioRender.com.

Long-distance Cu transport involves multiple steps: efflux from root xylem parenchyma cells into the xylem apoplast, upward movement via the transpiration stream, reabsorption into shoot xylem parenchyma cells, lateral transfer, loading into and unloading from the phloem (companion cells) for source-to-sink distribution (Figure 1). AtHMA5, a member of the PIB-type ATPase family, is the only transporter identified thus far with the assigned role for Cu loading into the root xylem (Andrés-Colás et al., Reference Andrés-Colás, Sancenón, Rodríguez-Navarro, Mayo, Thiele, Ecker, Puig and Peñarrubia2006). In the xylem, Cu is associated with the methionine-derived non-proteinogenic amino acid, nicotianamine (NA), which directly contributes to Cu root-to-shoot translocation in tomato and tobacco, and, as was shown recently, in A. thaliana (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Wang, Chen, Zhang, Wang, Song, Liu, Lv, Han, Wang, Yan, Lei and Chao2021; Pich & Scholz, Reference Pich and Scholz1996; Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Terada, Nakai, Nakanishi, Yoshimura, Mori and Nishizawa2003).

Historically, NA was primarily linked with iron (Fe) transport, as it is a precursor for Fe(III)-chelating phytosiderophores (PSs) that mediate Fe3+ uptake in grasses, while in non-grass species, NA supports long-distance Fe transport mainly via the phloem from source to sink tissues (Curie et al., Reference Curie, Cassin, Couch, Divol, Higuchi, Le Jean, Misson, Schikora, Czernic and Mari2009; Stephan & Procházka, Reference Stephan and Procházka1989). Consistent with this role, the NA-deficient chloronerva mutant of tomato displays Fe deficiency symptoms, including interveinal chlorosis, altered root morphology and stunted growth, despite adequate Fe supply (Curie et al., Reference Curie, Cassin, Couch, Divol, Higuchi, Le Jean, Misson, Schikora, Czernic and Mari2009; Stephan & Procházka, Reference Stephan and Procházka1989). In addition, the Arabidopsis nax4-2 mutant, lacking all four NA synthase (NAS) genes, is sterile and shows a chloronerva-like phenotype (Klatte et al., Reference Klatte, Schuler, Wirtz, Fink-Straube, Hell and Bauer2009; Stephan & Grun, Reference Stephan and Grun1989). Moreover, the nax4-1 mutant, which retains residual NA accumulation in leaves, exhibits a marked reduction in seed Fe content, further supporting the role for NA in the phloem-based, long-distance Fe transport (Klatte et al., Reference Klatte, Schuler, Wirtz, Fink-Straube, Hell and Bauer2009).

Notably, however, NA forms highly stable complexes with Cu. Based on stability constants (log K) for NA-metal complexes, Cu2+ forms one of the most stable complexes with NA, second only to Fe3+. The strength of binding decreases in the order: Fe3+ (20.6) > Cu2+ (18.6) > Ni2+ (16.1) > Co2+ (14.8) ≈ Zn2+ (14.7) > Fe2+ (12.1) > Mn (Beneš et al., Reference Beneš, Schreiber, Ripperger and Kircheiss1983; Blindauer & Schmid, Reference Blindauer and Schmid2010). This high affinity suggests that NA can readily chelate Cu, supporting the role of NA in long-distance Cu transport as well. Indeed, in tomato, Fe(III) is predominantly chelated by citrate in the xylem, leaving NA available to mobilize Cu(II) (Pich & Scholz, Reference Pich and Scholz1996; Rellán-Álvarez et al., Reference Rellán-Álvarez, Giner-Martínez-Sierra, Orduna, Orera, Rodríguez-Castrillón, García-Alonso, Abadía and Álvarez-Fernández2009). Further support for the role of NA in long-distance Cu transport comes from the discovery of two NA efflux transporters, NAET1 and NAET2, members of the NRT1/PTR family (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Wang, Chen, Zhang, Wang, Song, Liu, Lv, Han, Wang, Yan, Lei and Chao2021). NAET 1 and NAET2 mediate NA secretion into secretory vesicles, which are then transported to the cell surface and released into the apoplast space, creating an NA pool outside the cell for metal binding. Consequently, NA levels are low in the xylem and phloem sap of the naet1 naet2 double mutant (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Wang, Chen, Zhang, Wang, Song, Liu, Lv, Han, Wang, Yan, Lei and Chao2021). These mutants also exhibit phenotypes similar to chloronerva in tomato and nas4x-2 or ysl1 ysl3 mutants in A. thaliana, all of which are defective in NA biosynthesis or metal-NA transport (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Wang, Chen, Zhang, Wang, Song, Liu, Lv, Han, Wang, Yan, Lei and Chao2021; Chu et al., Reference Chu, Chiecko, Punshon, Lanzirotti, Lahner, Salt and Walker2010; Klatte et al., Reference Klatte, Schuler, Wirtz, Fink-Straube, Hell and Bauer2009; Waters et al., Reference Waters, Chu, Didonato, Roberts, Eisley, Lahner, Salt and Walker2006). Interestingly, Fe levels in xylem sap of the naet1 naet2 double mutant remain unchanged, but Cu concentrations are reduced by nearly 50%. This suggests that, similar to tomato, NA facilitates xylem-based root-to-shoot Cu transport. Concerning phloem sap, the concentration of both Fe and Cu was reduced in the naet1 naet2 double mutant. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that, in addition to its established role in Fe transport via the phloem, NA also facilitates xylem and phloem-based long-distance transport of Cu.

Concerning Cu transport in the shoot, from what is known thus far, a COPT family member, AtCOPT6, localizes to the plasma membrane and is proposed to mediate lateral Cu transport in above-ground tissues (Jung et al., Reference Jung, Gayomba, Rutzke, Craft, Kochian and Vatamaniuk2012). Cu reabsorption from the xylem and phloem-based sources-to-sink distribution is mainly mediated by members of the oligopeptide transporter (OPT) family. This family comprises two major clades: the OPTs and yellow stripe-like (YSL) transporters (Lubkowitz, Reference Lubkowitz2011). Of YSLs, AtYSL2 has been shown to transport a Cu-NA in the heterologous yeast system. It is expressed in the vasculature, and its mRNA level increases under Cu deficiency, declining under high Cu treatments (DiDonato et al., Reference DiDonato, Roberts, Sanderson, Eisley and Walker2004). In addition to Cu, AtYSL2 is postulated to transport Fe, but its expression declines under Fe deficiency, suggesting that AtYSL2 contributes to Cu-Fe crosstalk (DiDonato et al., Reference DiDonato, Roberts, Sanderson, Eisley and Walker2004). Based on the expression pattern in the vasculature, it is proposed that AtYSL2 mediates lateral Cu (and Fe) movement in the vascular system, perhaps via reabsorption from the xylem into the parenchyma cells. AtYSL1 and AtYSL3, on the other hand, localize to phloem companion cells and contribute to Cu remobilization to reproductive tissues and seeds (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Chiecko, Punshon, Lanzirotti, Lahner, Salt and Walker2010; Mustroph et al., Reference Mustroph, Zanetti, Jang, Holtan, Repetti, Galbraith, Girke and Bailey-Serres2009; Waters et al., Reference Waters, Chu, Didonato, Roberts, Eisley, Lahner, Salt and Walker2006). In addition to resembling the tomato chloronerva mutant, ysl1 ysl3 double mutants show reduced Cu levels in seeds and flowers, delayed flowering and reduced fertility, phenotypes that are partially rescued by Cu supplementation (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Chiecko, Punshon, Lanzirotti, Lahner, Salt and Walker2010; Waters et al., Reference Waters, Chu, Didonato, Roberts, Eisley, Lahner, Salt and Walker2006).

Cu loading into the phloem companion cells is mediated by AtOPT3, a member of the OPT clade of the OPT family (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023). The opt3-3 mutant exhibits reduced Cu in phloem sap and impaired source-to-sink Cu movement, indicating the role of AtOPT3 in Cu phloem loading and redistribution to young tissues and developing seeds (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023; Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, Gayomba, Jung, Vimalakumari, Piñeros, Craft, Rutzke, Danku, Lahner, Punshon, Guerinot, Salt, Kochian and Vatamaniuk2014). AtOPT3 was originally identified as a critical component of Fe homeostasis and root-to-shoot signalling in A. thaliana (Stacey et al., Reference Stacey, Patel, McClain, Mathieu, Remley, Rogers, Gassmann, Blevins and Stacey2007) and detailed in Section 4.2. The transport substrate of AtOPT3 has been debated, with hypotheses ranging from peptide-metal complexes to free metal ions. Indeed, early studies show that members of the OPT and YSL clades of the OPT family transport tetra- and pentapeptides and metal-NA complexes, respectively (Curie et al., Reference Curie, Cassin, Couch, Divol, Higuchi, Le Jean, Misson, Schikora, Czernic and Mari2009; Osawa et al., Reference Osawa, Stacey and Gassmann2006). More recent evidence has shown that AtOPT3 can transport free Fe2+, Cd2+ and Cu2+ ions when expressed in Xenopus oocytes and yeast metal transport mutants (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023; Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, Gayomba, Jung, Vimalakumari, Piñeros, Craft, Rutzke, Danku, Lahner, Punshon, Guerinot, Salt, Kochian and Vatamaniuk2014). Notably, Cu2+ was the preferred substrate over Cu-NA in oocyte assays (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023). In parallel, NAET1 and NAET2, recently identified as NA exporters, release NA into the phloem companion cells, influencing Fe and Cu delivery to seeds (Chao et al., Reference Chao, Wang, Chen, Zhang, Wang, Song, Liu, Lv, Han, Wang, Yan, Lei and Chao2021). These findings suggest that AtOPT3 and NAET1/2 may act in concert to facilitate the co-delivery of free Cu2+ and Fe2+, and their complexation with NA in the phloem, enabling efficient long-distance transport.

In addition to NA, other molecules contribute to Cu transport and redistribution in plants. Metallothioneins (MTs), cysteine-rich proteins, bind Cu through thiol groups and function in buffering excess Cu as well as in its redistribution from leaves to seeds (Benatti et al., Reference Benatti, Yookongkaew, Meetam, Guo, Punyasuk, AbuQamar and Goldsbrough2014; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Meetam and Goldsbrough2008). Glutathione (GSH), a ubiquitous tripeptide, also chelates Cu and facilitates Cu uptake and trafficking in animals, while its role in plants is mainly associated with detoxification of excessive Cu concentrations (Burkhead et al., Reference Burkhead, Gogolin Reynolds, Abdel-Ghany, Cohu and Pilon2009; Maryon et al., Reference Maryon, Molloy and Kaplan2013). Whether GSH is also involved in Cu trafficking and/or long-distance transport in plants needs to be verified experimentally. The ATX1-like Cu chaperone, CCH, is detected in the phloem and has been implicated in Cu loading and long-distance distribution, ensuring adequate supply to sink tissues (Himelblau et al., Reference Himelblau, Mira, Lin, Cizewski Culotta, Peñarrubia and Amasino1998; Mira et al., Reference Mira, Martínez-García and Peñarrubia2001). Thus, Cu transport involves not only transporters but also a network of Cu-binding peptides and chaperones.

2.2. Cu uptake and long-distance transport in grasses

Copper uptake strategies in grasses remain less well understood than in dicots. Moreover, studies on the ionic form of Cu absorbed by grass roots have yielded conflicting results, suggesting three not mutually exclusive models for Cu uptake (Figure 2):

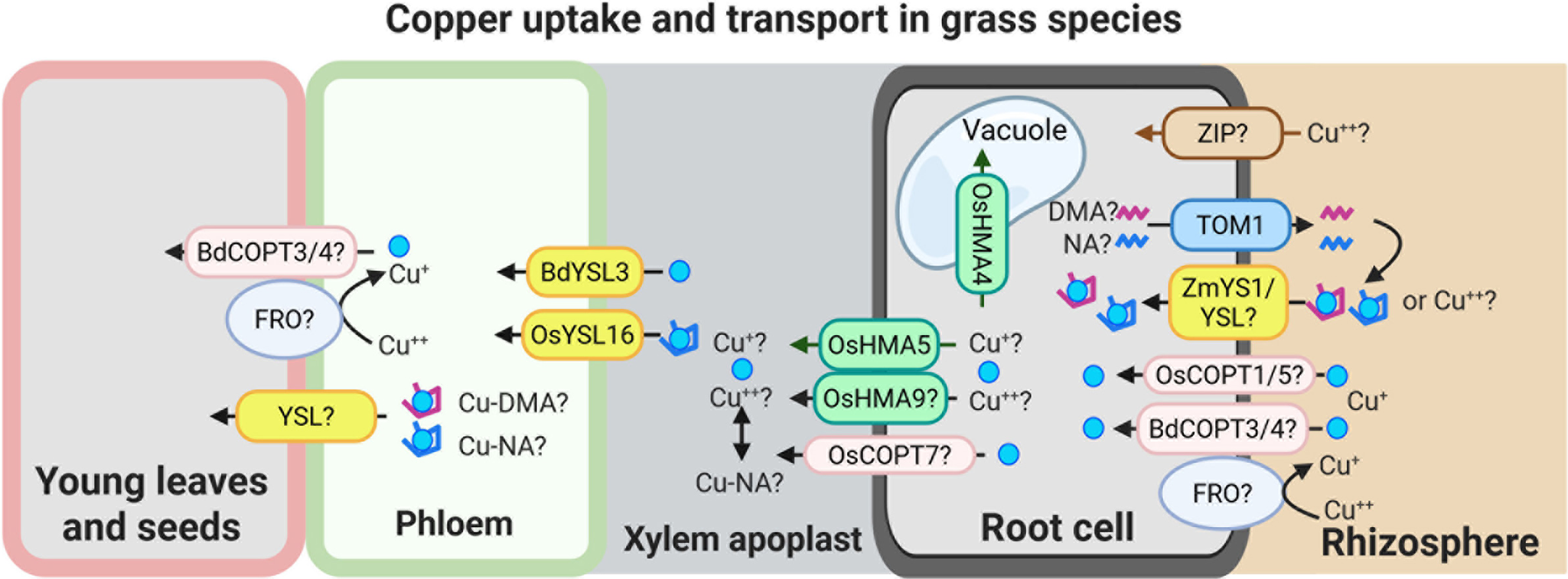

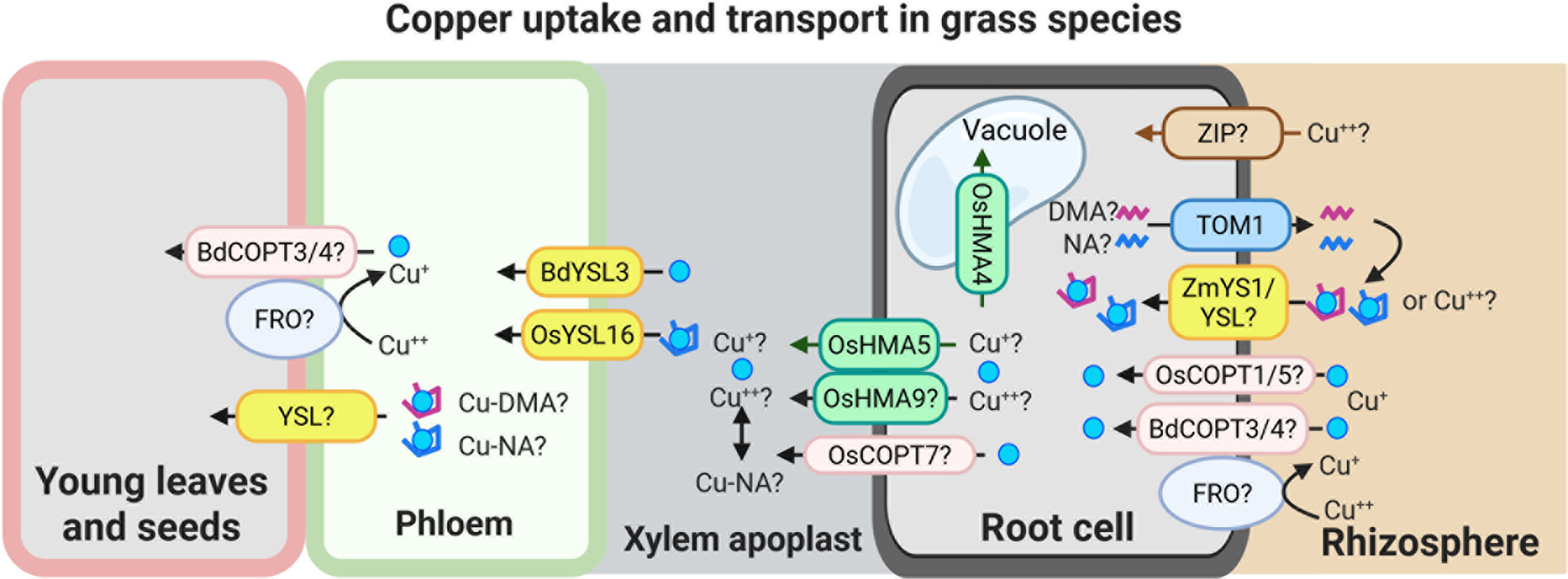

Figure 2. Speculative model for Cu uptake and transport in grass species.

This model illustrates potential mechanisms of Cu uptake and internal transport in grasses. Cu(II) uptake from the rhizosphere may involve as-yet unidentified ZIP-like transporters and/or YS1/YSL family members. Cu uptake may also occur via secretion of phytosiderophores, primarily 2′-deoxymugineic acid (DMA), and possibly nicotianamine (NA), through the TOM1-like transporters. The resulting Cu-DMA or Cu-NA complexes can then be imported into root cells via ZmYS1/YSL transporters. A low-affinity Cu uptake system, potentially involving BdCOPT3/4, OsCOPT1/5 and an FRO-type reductase, may also contribute to Cu acquisition directly from the rhizosphere.

Once inside the root, Cu is loaded into the xylem by HMA family transporters, including OsHMA5 and possibly OsHMA9 and OsCOPT7. OsHMA4 was identified as a vacuolar Cu importer in rice. The transfer of Cu from xylem to phloem is mediated by BdYSL3 and OsYSL16, both of which facilitate Cu redistribution towards sink tissues. Although the precise mechanisms of Cu unloading into sink organs remain to be elucidated, available evidence suggests that YSL transporters and components of the low-affinity Cu uptake pathway may play a role in this process as well. The figure was created with BioRender.com.

1) Uptake of Cu+ (Cu(I)): Evidence from (Jouvin et al., Reference Jouvin, Weiss, Mason, Bravin, Louvat, Zhao, Ferec, Hinsinger and Benedetti2012) suggests that, as in non-graminaceous plants, Cu(II) is reduced to Cu(I) before uptake into the root epidermal cells of grasses. This implies the existence of root surface reductase activity in grasses, analogous to FRO3/4 enzymes in A. thaliana and other dicots (Figures 1 and 2). However, unlike non-grass species, which possess multiple FRO-like genes, grasses such as corn, Brachypodium distachyon (hereafter brachypodium), and rice harbour only one or two FRO-like genes (Table 1; (Schwacke et al., Reference Schwacke, Schneider, van der Graaff, Fischer, Catoni, Desimone, Frommer, Flügge and Kunze2003; Schwacke & Flügge, Reference Schwacke, Flügge, Mock, Matros and Witzel2018). Still, the limited number of FRO genes does not exclude the possibility that grasses use an as-yet-unidentified mechanism for Cu(II) reduction at the root surface. As for Cu(I) transporters, several COPT/CTR family members in rice, including OsCOPT1, OsCOPT5, OsCOPT6 and OsCOPT7, are transcriptionally upregulated in roots under Cu deficiency (Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li, Xiao and Wang2011). OsCOPT1 and OsCOPT5 have been shown to contribute to Cu accumulation in the shoots, but whether these transporters mediate Cu uptake is unknown (Yao et al., Reference Yao, Kang, Guo, Yang, Huang, Lan, Zhou, Wang, Wei, Xu and Li2022). Interestingly, however, loss of their function not only decreased shoot Cu levels but also reduced viral resistance, exemplifying the role of Cu in pathogen resistance (Yao et al., Reference Yao, Kang, Guo, Yang, Huang, Lan, Zhou, Wang, Wei, Xu and Li2022). In brachypodium, five COPT genes have been identified, with BdCOPT3 and BdCOPT4 being Cu-deficiency-inducible in both roots and shoots. These proteins localize to the plasma membrane but, unlike their high-affinity A. thaliana counterparts, they mediate low-affinity Cu uptake, suggesting mechanistic divergence in Cu acquisition from A. thaliana (Jung et al., Reference Jung, Gayomba, Yan and Vatamaniuk2014).

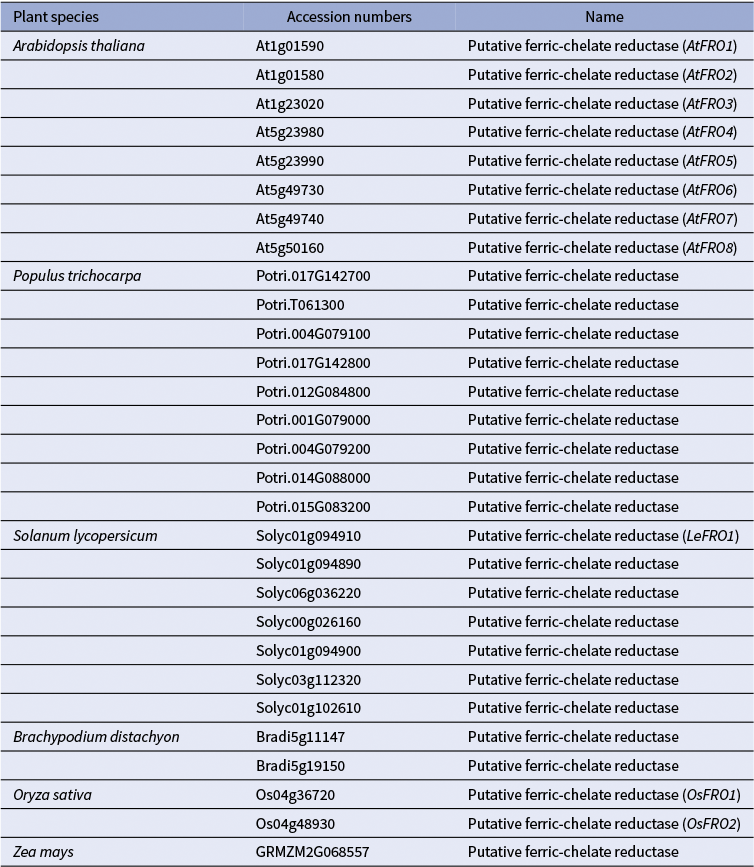

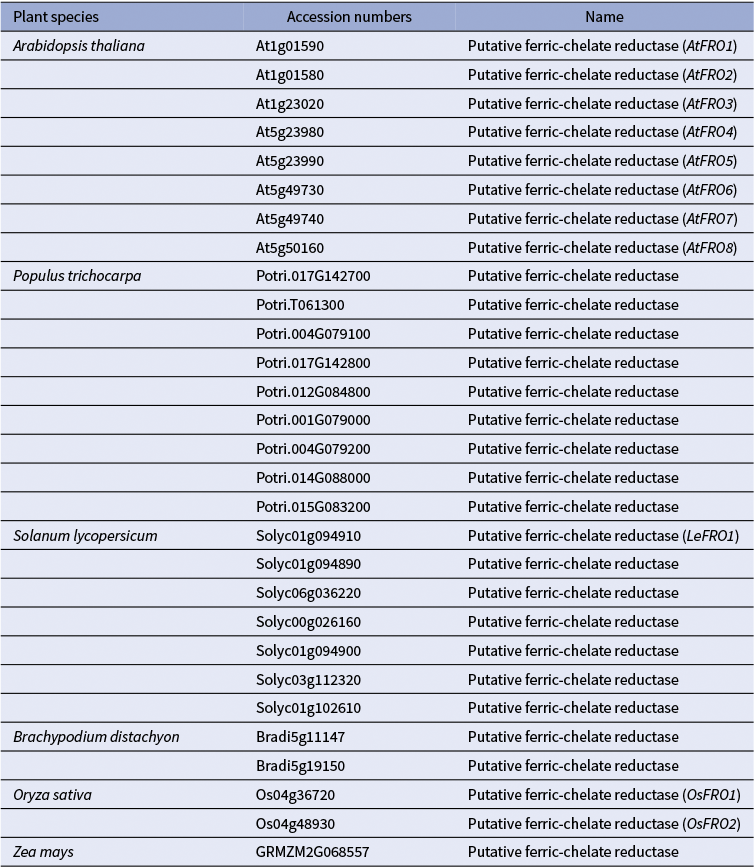

Table 1 A list of FRO-like genes in monocot and dicot model plants. The accession numbers of the FRO-homologs were retrieved from the Arabidopsis Plant Membrane Protein database (Aramemnon) (Schwacke et al., Reference Schwacke, Schneider, van der Graaff, Fischer, Catoni, Desimone, Frommer, Flügge and Kunze2003; Schwacke & Flügge, Reference Schwacke, Flügge, Mock, Matros and Witzel2018).

2) Uptake of Cu2+ (Cu(II)): Alternatively, Ryan et al. (Reference Ryan, Kirby, Degryse, Harris, McLaughlin and Scheiderich2013) found that roots of oat (Avena sativa) absorb Cu(II) directly from the soil solution, with Cu(II) subsequently reduced to Cu(I) within root cells. This model implies the existence of Cu(II) transporters at the plasma membrane (Figure 2). While ZIP2 has been recognized for its function in mediating Cu uptake, presumably as Cu(II), in the roots of A. thaliana (Robe et al., Reference Robe, Lefebvre-Legendre, Cleard and Barberon2025; Wintz et al., Reference Wintz, Fox, Wu, Feng, Chen, Chang, Zhu and Vulpe2003), corresponding ZIP transporters in grasses remain unidentified. Recently, ZmYS1 was found to mediate Cu(II) transport when expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Although ZmYS1 is a well-characterized metal-NA and metal-PS transporter, ZmYS1-expressing oocytes accumulated significantly higher levels of Cu when it was supplied in ionic form compared to the Cu-NA complex (Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Jiang, Rahmati, Chia, Dokuchayeva, Kavulych, Zavodna, Mendoza, Huang, Smieshka, Miller, Woll, Terek, Romanyuk, Pineros, Zhou and Vatamaniuk2021). The physiological substrate specificity of ZmYS1 and the contribution of YSL family members to Cu(II) uptake in planta remain to be established.

3) Uptake of Cu(II)-ligand complexes: A third scenario involves the uptake of Cu complexed with ligands, particularly NA, that strongly chelates Cu(II) and plays a known role in long-distance Cu transport in both grasses and dicots (reviewed in (Curie et al., Reference Curie, Cassin, Couch, Divol, Higuchi, Le Jean, Misson, Schikora, Czernic and Mari2009)). Whether NA is secreted into the rhizosphere by Cu-deficient roots to mobilize soil Cu is unknown. Grasses are known to secrete PSs to solubilize Fe(III) under Fe deficiency, and this process involves TOM1 (Transporter of Mugineic Acid PSs) in rice and barley (Nozoye et al., Reference Nozoye, Nagasaka, Kobayashi, Takahashi, Sato, Sato, Uozumi, Nakanishi and Nishizawa2011; Takagi, Reference Takagi1976). As it was shown in maize, YS1 mediates Fe-PC complexes uptake into root cells (Curie et al., Reference Curie, Panaviene, Loulergue, Dellaporta, Briat and Walker2001). Notably, ZmYS1 is capable of transporting Cu-PS and Cu-NA complexes in the heterologous system (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023; Curie et al., Reference Curie, Panaviene, Loulergue, Dellaporta, Briat and Walker2001; Schaaf et al., Reference Schaaf, Ludewig, Erenoglu, Mori, Kitahara and von Wirén2004). However, whether NA, MAs and YS1/YSLs are involved in Cu uptake in planta remains an open question.

Concerning Cu long-distance transport in grasses, several homologs of AtHMA5 in rice, including OsHMA5 and possibly OsHMA9, are induced by high Cu and have been proposed to mediate Cu loading into the root xylem, thereby contributing to long-distance transport (Andrés-Colás et al., Reference Andrés-Colás, Sancenón, Rodríguez-Navarro, Mayo, Thiele, Ecker, Puig and Peñarrubia2006; Deng et al., Reference Deng, Yamaji, Xia and Ma2013; Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, Kuroda, Kimura, Southron-Francis, Furuzawa, Kimura, Iuchi, Kobayashi, Taylor and Koyama2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kim, Lee and An2007). OsHMA6 also belongs to the AtHMA5 clade and shares 83% sequence similarity with OsHMA9 (Zou et al., Reference Zou, Li, Zhu, Chen, He and Ye2020). It has been demonstrated to function as a plasma membrane Cu efflux transporter, although it remains unclear whether OsHMA6 also participates in the long-distance transport of Cu in rice. More recently, OsCOPT7 was demonstrated to be predominantly expressed in the exodermis and stele of roots, facilitating root-to-shoot translocation via xylem, and contributing to Cu accumulation in rice grains (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Cao, Xia, Xv, Lin and Chen2024).

Among the YSL transporters, OsYSL16, transports Cu-NA complexes when expressed heterologously in yeast lacking high-affinity COPTs CTR1p and CTR3p (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Yamaji, Yokosho and Ma2012). Loss-of-function mutations in OsYSL16 have a defect in Cu redistribution from sources, such as mature leaves and developing flag leaves, to sink tissues, including panicles; this defect results in reduced grain yield (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Yamaji, Yokosho and Ma2012). Its ortholog in brachypodium, BdYSL3, is transcriptionally upregulated under Cu deficiency and mediates Cu redistribution from mature leaves to flag leaves, reproductive organs, and developing grains as well (Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Jiang, Rahmati, Chia, Dokuchayeva, Kavulych, Zavodna, Mendoza, Huang, Smieshka, Miller, Woll, Terek, Romanyuk, Pineros, Zhou and Vatamaniuk2021). Notably, BdYSL3 mutants exhibit decreased seed Cu levels, reduced seed size and diminished protein content, directly linking Cu transport to the development of these key agronomic traits. It has been shown that YSL transporters from different species mediate the transport of Cu-NA or Cu-PSs complexes (DiDonato et al., Reference DiDonato, Roberts, Sanderson, Eisley and Walker2004; Schaaf et al., Reference Schaaf, Ludewig, Erenoglu, Mori, Kitahara and von Wirén2004; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Yamaji, Yokosho and Ma2012). However, analysis of the transport capabilities of BdYSL3 using the Xenopus laevis oocyte expression system has shown that oocytes expressing BdYSL3 accumulate Cu only when it is supplied in ionic form, but not as the Cu-NA complex (Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Jiang, Rahmati, Chia, Dokuchayeva, Kavulych, Zavodna, Mendoza, Huang, Smieshka, Miller, Woll, Terek, Romanyuk, Pineros, Zhou and Vatamaniuk2021). By contrast, oocytes expressing ZmYS1 accumulate Cu when it is supplied as Cu-NA complex; however, Cu levels in ZmYS1-expressing oocytes increase significantly when Cu is supplied in the ionic form (Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Jiang, Rahmati, Chia, Dokuchayeva, Kavulych, Zavodna, Mendoza, Huang, Smieshka, Miller, Woll, Terek, Romanyuk, Pineros, Zhou and Vatamaniuk2021). The physiological substrate(s) of YSLs are yet to be determined.

2.3. Intracellular Cu transport and trafficking

The cytosol maintains extremely low concentrations of free Cu ions, estimated to be in the femtomolar to zeptomolar range, through tight buffering by cellular ligands and Cu chaperones (Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Lee and Chang2017; Hong-Hermesdorf et al., Reference Hong-Hermesdorf, Miethke, Gallaher, Kropat, Dodani, Chan, Barupala, Domaille, Shirasaki, Loo, Weber, Pett-Ridge, Stemmler, Chang and Merchant2014; Schmollinger et al., Reference Schmollinger, Chen, Strenkert, Hui, Ralle and Merchant2021; Waldron & Robinson, Reference Waldron and Robinson2009; Wintz & Vulpe, Reference Wintz and Vulpe2002). These ligands and chaperones ensure safe and efficient delivery of Cu to its target proteins and organelles. The A. thaliana genome encodes nine Cu chaperones: Cu chaperone for superoxide dismutase (CCS), antioxidant protein 1 (ATX1), ATX1-like chaperone (CCH), cytochrome c oxidase 11 (COX11), COX17, two homologs of the yeast Cu chaperone (HCC1 and HCC2) and plastid Cu chaperone 1 (PCH1) (Attallah et al., Reference Attallah, Welchen, Martin, Spinelli, Bonnard, Palatnik and Gonzalez2011; Balandin & Castresana, Reference Balandin and Castresana2002; Blaby-Haas et al., Reference Blaby-Haas, Padilla-Benavides, Stube, Arguello and Merchant2014; Chu et al., Reference Chu, Lee, Guo, Pan, Chen, Li and Jinn2005; Himelblau et al., Reference Himelblau, Mira, Lin, Cizewski Culotta, Peñarrubia and Amasino1998; Llases et al., Reference Llases, Lisa, Morgada, Giannini, Alzari and Vila2020; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Lo and Yeh2012; Steinebrunner et al., Reference Steinebrunner, Landschreiber, Krause-Buchholz, Teichmann and Rödel2011). A new putative Cu chaperone induced by pathogens (CCP) has been recently identified in A. thaliana that, unlike other chaperones, localizes to the nucleus (Chai et al., Reference Chai, Dong, Liu, Zhang, Zhang, Tong, Zhu, Zou and Wang2020). Most of these proteins share a conserved heavy metal-binding domain, characterized by an MXXCXC motif, and function through protein-protein interactions, guiding Cu from cellular entry points to destination cuproenzymes or transporters within the intracellular compartments (Figure 1) and (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Jones and Dameron1999; Rono et al., Reference Rono, Sun and Yang2022). For example, ATX1 mediates Cu transfer to rice HMA4, HMA5, HMA6, HMA9 and COPT7, facilitating root-to-shoot translocation and redistribution of Cu from old leaves to developing tissues and seeds (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Cao, Xia, Xv, Lin and Chen2024; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen, Zhao, Sun, Jin, Shi, Sun, Li, Yang, Jing, Luo and Lian2018). Similarly, CCS, delivers Cu to three types of Cu/Zn Superoxide Dismutases: CSD1, in the cytosol, CSD2 in the chloroplast and CSD3 in peroxisomes (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Montagu and Inze1992; Chu et al., Reference Chu, Lee, Guo, Pan, Chen, Li and Jinn2005; Kliebenstein et al., Reference Kliebenstein, Monde and Last1998). CSD1 is a major Cu sink in the cytosol, and mRNA abundance for both CCS and CSD1 (and as described below, CDS2) negatively correlates with Cu availability in a microRNA 398 (miR398)-dependent manner (Cohu et al., Reference Cohu, Abdel-Ghany, Gogolin Reynolds, Onofrio, Bodecker, Kimbrel, Niyogi and Pilon2009).

Chloroplasts are the main sinks for copper (Cu) in photosynthetic tissues, making up an estimated 30% of the overall cellular Cu in mature leaves, as was estimated for soil-grown A. thaliana (Shikanai et al., Reference Shikanai, Müller-Moulé, Munekage, Niyogi and Pilon2003). This is primarily because Cu is needed for plastocyanin, an essential soluble electron carrier that functions between the cytochrome-b6f complex and photosystem I (Burkhead et al., Reference Burkhead, Gogolin Reynolds, Abdel-Ghany, Cohu and Pilon2009; Weigel et al., Reference Weigel, Varotto, Pesaresi, Finazzi, Rappaport, Salamini and Leister2003; Yruela, Reference Yruela2009). Plant genomes contain two plastocyanin isoforms, PC1 and PC2, which have identical roles in electron transport (Abdel-Ghany, Reference Abdel-Ghany2009). Another major Cu-containing protein in the chloroplast is CSD2, which requires a Cu chaperone, CCS, for Cu delivery (Cohu et al., Reference Cohu, Abdel-Ghany, Gogolin Reynolds, Onofrio, Bodecker, Kimbrel, Niyogi and Pilon2009). A dedicated chaperone inserting Cu into plastocyanin has not yet been identified.

Additionally, many plants, including poplar and spinach, have the thylakoid lumen associated class of Cu enzymes, polyphenol oxidases (PPOs), which oxidize a variety of aromatic compounds. These enzymes are believed to play roles in plant defence and in synthesizing specialized metabolites. However, A. thaliana and green algae like Chlamydomonas reinhardtii do not have PPOs in this lumen (Mayer, Reference Mayer2006; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2014).

Cu likely enters the chloroplast intermembrane space by diffusion through porins in the outer membrane, potentially bound to GSH or a PCH1 (Aguirre & Pilon, Reference Aguirre and Pilon2015; Blaby-Haas et al., Reference Blaby-Haas, Padilla-Benavides, Stube, Arguello and Merchant2014). In A. thaliana, PCH1 delivers Cu to a PIB-type Cu-transporting ATPase, PAA1 (Plastid ATPase of Arabidopsis 1, alias HMA6), localized to the inner envelope and actively transporting Cu into the chloroplast stroma (Shikanai et al., Reference Shikanai, Müller-Moulé, Munekage, Niyogi and Pilon2003). PAA1 loss-of-function mutants are chlorotic due to a defect in plastocyanin assembly; this phenotype underlies the importance of PAA1/HMA6 transporter in chloroplast function. Another PIB-ATPase family member, AtHMA1, localizes to the chloroplast and is involved in chloroplast Cu homeostasis, as evidenced by the decreased chloroplast Cu levels in the hma1 mutants (Boutigny et al., Reference Boutigny, Sautron, Finazzi, Rivasseau, Frelet-Barrand, Pilon, Rolland and Seigneurin-Berny2014). Unlike hma6 mutans, loss of AtHMA1 did not cause obvious phenotypes under standard conditions; however, the hma1 mutants are susceptible to high light.

Once in the stroma, Cu is further delivered to the thylakoid lumen by another PIB-type ATPase, PAA2 (alias HMA8), localized to the thylakoid membrane (Abdel-Ghany et al., Reference Abdel-Ghany, Müller-Moulé, Niyogi, Pilon and Shikanai2005). PAA2/HMA8 moves Cu from the stroma into the thylakoid lumen, where it is incorporated into plastocyanin (Figure 1). Together, the sequential actions of Cu transporters and chaperones ensure the proper metalation of key Cu-dependent proteins in the chloroplast while preventing Cu toxicity (Abdel-Ghany et al., Reference Abdel-Ghany, Müller-Moulé, Niyogi, Pilon and Shikanai2005; Seigneurin-Berny et al., Reference Seigneurin-Berny, Gravot, Auroy, Mazard, Kraut, Finazzi, Grunwald, Rappaport, Vavasseur, Joyard, Richaud and Rolland2006; Shikanai et al., Reference Shikanai, Müller-Moulé, Munekage, Niyogi and Pilon2003).

Mitochondria, a second major Cu sink, contain 5-15% of total cellular Cu, used primarily by cytochrome c oxidase (COX, or mitochondrial complex IV), which transfers electrons from cytochrome c to oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor of the respiratory mitochondrial electron transport chain (Kadenbach et al., Reference Kadenbach, Hüttemann, Arnold, Lee and Bender2000; Ravet & Pilon, Reference Ravet and Pilon2013). A. thaliana mitochondrial Cu pools are maintained by chaperones, such as COX11, COX17 and HCC1, all essential for COX assembly and mitochondrial respiration (Attallah et al., Reference Attallah, Welchen, Martin, Spinelli, Bonnard, Palatnik and Gonzalez2011; Burkhead et al., Reference Burkhead, Gogolin Reynolds, Abdel-Ghany, Cohu and Pilon2009; Llases et al., Reference Llases, Lisa, Morgada, Giannini, Alzari and Vila2020; Steinebrunner et al., Reference Steinebrunner, Gey, Andres, Garcia and Gonzalez2014). HCC1 homolog, HCC2, localizes to the mitochondria as well, but lacks canonical Cu binding motifs and is implicated in response to UV-B radiation (Steinebrunner et al., Reference Steinebrunner, Gey, Andres, Garcia and Gonzalez2014).

Cu transport in and out of mitochondria in plants is poorly understood despite the essential role of this metal in mitochondrial function. Concerning other species, the mitochondrial carrier family (MCF) member in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pic2, and its homolog in humans, SLC25A3, import Cu into the mitochondrial matrix (Boulet et al., Reference Boulet, Vest, Maynard, Gammon, Russell, Mathews, Cole, Zhu, Phillips, Kwong, Dodani, Leary and Cobine2018; Vest et al., Reference Vest, Leary, Winge and Cobine2013; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Boulet, Buckley, Phillips, Gammon, Oldfather, Moore, Leary and Cobine2021). MCF-like proteins are also found in plants. Three orthologous genes have been identified in A. thaliana genome and designated as AtMPT1/AT2/PHT3.3, AtMPT2/AT3/PHT3.2 and AtMPT3/AT5/PHT3.1 (Hamel et al., Reference Hamel, Saint-Georges, De Pinto, Lachacinski, Altamura and Dujardin2004; Poirier & Bucher, Reference Poirier and Bucher2002). Previous studies suggested that they participate in phosphate transport (Poirier & Bucher, Reference Poirier and Bucher2002; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Miao, Sun, Yang, Wu, Huang and Zheng2012). Whether any of them is involved in Cu import into mitochondria is unknown.

The vacuole serves as a dynamic storage compartment for Cu, particularly under conditions of excess. Plant transporters mediating vacuolar Cu sequestration are not clearly defined. AtCOPT3 localizes to the secretory pathway and is expressed in the vasculature and pollen grains, and its overexpression increases plant Cu levels (Andrés-Colás et al., Reference Andrés-Colás, Carrió-Seguí, Abdel-Ghany, Pilon and Peñarrubia2018). AtCOPT5 localizes to the tonoplast and mediates Cu efflux under Cu deficiency (Andrés-Colás et al., Reference Andrés-Colás, Perea-García, Puig and Peñarrubia2010). This process allows plants to buffer cytosolic Cu levels and remobilize stored Cu when needed, as evidenced by the compromised growth of the copt5 mutants under Cu deficiency (Garcia-Molina et al., Reference Garcia-Molina, Andrés-Colás, Perea-García, del Valle-Tascón, Peñarrubia and Puig2011; Klaumann et al., Reference Klaumann, Nickolaus, Fürst, Starck, Schneider, Ekkehard Neuhaus and Trentmann2011). Consistent with the notion of the existing crosstalk between Cu and Fe homeostasis, copt5 mutants are sensitive to Fe deficiency, while the loss of Fe exporters NRAMP3 and NRAMP4 increases the plant’s sensitivity to Cu deficiency (Carrió-Seguí et al., Reference Carrió-Seguí, Romero, Curie, Mari and Peñarrubia2019).

In rice, OsHMA4 and its transcript variants function in sequestering Cu into root vacuoles, thereby limiting Cu accumulation in the grain (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Zhang, Xu, Zhao, Chen and Cao2022; Guan et al., Reference Guan, Cao, Xia, Xv, Lin and Chen2024). Heterologous expression studies further demonstrated that OsHMA4 localizes to the tonoplast and enhances vacuolar Cu sequestration. Loss-of-function mutants of OsHMA4 exhibit elevated Cu in the shoots, xylem sap and grains, confirming its role as a vacuolar Cu importer in cellular Cu homeostasis and maintaining root-to-shoot Cu balance.

The nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) also harbour small but functionally critical pools of Cu. RESPONSIVE-TO-ANTAGONIST 1 (RAN1, alias AtHMA7) transports Cu across the ER membrane to provide Cu(I) to the transmembrane sensor domain of the ethylene receptor ETHYLENE RESPONSE 1 (ETR1) to confer proper ethylene response (Binder et al., Reference Binder, Rodríguez and Bleecker2010; Hirayama et al., Reference Hirayama, Kieber, Hirayama, Kogan, Guzman, Nourizadeh, Alonso, Dailey, Dancis and Ecker1999; Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Esch, Hall, Binder, Schaller and Bleecker1999; Woeste & Kieber, Reference Woeste and Kieber2000) (Figure 1). Cu chaperon ATX1 traffics Cu to RAN1 to be incorporated to ETR1 and the partial loss-of-function Arabidopsis ran1-1 mutant exhibits a mild constitutive ethylene response (Li et al., Reference Li, Lacey, Ye, Lu, Yeh, Xiao, Li, Wen, Binder and Zhao2017; Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Esch, Hall, Binder, Schaller and Bleecker1999). High-affinity ethylene binding by ETR1 is primarily mediated by Cu(I) coordinated to a conserved cysteine and histidine residues in the second transmembrane helix of ETR N-terminal ethylene-binding domain, while an asparagine residue plays a crucial role in positioning the histidine residue for Cu coordination, further contributing to the high-affinity binding (Azhar et al., Reference Azhar, Abbas, Aman, Yamburenko, Chen, Muller, Uzun, Jewell, Dong, Shakeel, Groth, Binder, Grigoryan and Schaller2023; Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Esch, Hall, Binder, Schaller and Bleecker1999; Schaller et al., Reference Schaller, Ladd, Lanahan, Spanbauer and Bleecker1995). Structural modelling of the transmembrane sensor domain of Arabidopsis ETR revealed a dimeric state with two Cu(I) per receptor dimer and potentially two ethylene-binding sites per receptor dimer (Schott-Verdugo et al., Reference Schott-Verdugo, Müller, Classen, Gohlke and Groth2019).

Peroxisomes, multifunctional organelles that contain enzymes catalysing diverse oxidative reactions, require Cu to manage oxidative stress (Corpas et al., Reference Corpas, González-Gordo and Palma2020). For example, CSD3 (Cu/Zn-SOD) is a major Cu protein in peroxisomes, and, as noted above, Cu is delivered to CSD3 via a Cu chaperone CCS (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Lee, Guo, Pan, Chen, Li and Jinn2005). In addition, peroxisomes possess Cu-containing amine oxidases, enzymes that oxidize polyamines with concomitant production of H2O2 and NH3 (Planas-Portell et al., Reference Planas-Portell, Gallart, Tiburcio and Altabella2013). How Cu is delivered to peroxisomes is unknown.

The role of Cu and its precise localization in the nucleus of plants is not fully understood as well. However, a recently discovered Cu chaperone induced by pathogens (CCP), contains a nuclear localization signal (Chai et al., Reference Chai, Dong, Liu, Zhang, Zhang, Tong, Zhu, Zou and Wang2020). CCP interacts with transcription factor TGA2 in vivo and in vitro and induces SA-mediated defence signalling (Chai et al., Reference Chai, Dong, Liu, Zhang, Zhang, Tong, Zhu, Zou and Wang2020). Recent reports from the studies in animal systems indicate that Cu ions are predominantly located in the perinuclear and nuclear areas, including nucleoli, and act during mitosis; specifically, Cu binding to cyclins and subsequent antioxidant 1 chaperon-dependent transfer to cyclin-dependent kinase 1 is essential for its kinase function, triggering the G2/M progression in the cell cycle (McRae et al., Reference McRae, Lai and Fahrni2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yang, Yu, Jin, Nie, Zhang, Ren, Ge, Zhang, Ma, Dai, Sui and Teng2025; Yang et al., Reference Yang, McRae, Henary, Patel, Lai, Vogt and Fahrni2005). A newly discovered function of the recombinant Xenopus laevis histone H3-H4 tetramer in reducing Cu(II) to Cu(I), and the essentiality of this function of the H3 histones for Cu utilization in S. cerevisiae, is a testament to the untapped Cu cellular resources and roles in biology (Attar et al., Reference Attar, Campos, Vogelauer, Cheng, Xue, Schmollinger, Salwinski, Mallipeddi, Boone, Yen, Yang, Zikovich, Dardine, Carey, Merchant and Kurdistani2020).

3. Regulation of Cu homeostasis

Plants employ two major strategies to maintain Cu homeostasis: regulation of Cu acquisition and the Cu economy/metal switch mechanism (Figure 3A). In A. thaliana, Cu acquisition is regulated by the conserved transcription factor SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE 7 (SPL7) and its downstream target, the clade Ib basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factor COPPER DEFICIENCY-INDUCED TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR 1 (CITF1, also known as bHLH160) (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Casero, Singh, Wilson, Grande, Yang, Dodani, Pellegrini, Huijser, Connolly, Merchant and Krämer2012; Yamasaki et al., Reference Yamasaki, Hayashi, Fukazawa, Kobayashi and Shikanai2009; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Chia, Sheng, Jung, Zavodna, Zhang, Huang, Jiao, Craft, Fei, Kochian and Vatamaniuk2017). Together, SPL7 and CITF1 coregulate genes encoding the high-affinity Cu uptake system in roots, including COPT2, FRO4 and FRO5. Although CITF1’s direct targets have yet to be identified, chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) has identified CITF2 (alias bHLH23), with an unknown role in Cu homeostasis, and Cu transporters ZIP2 and YSL2 as direct SPL7 targets (Schulten et al., Reference Schulten, Pietzenuk, Quintana, Scholle, Feil, Krause, Romera-Branchat, Wahl, Severing, Coupland and Krämer2022).

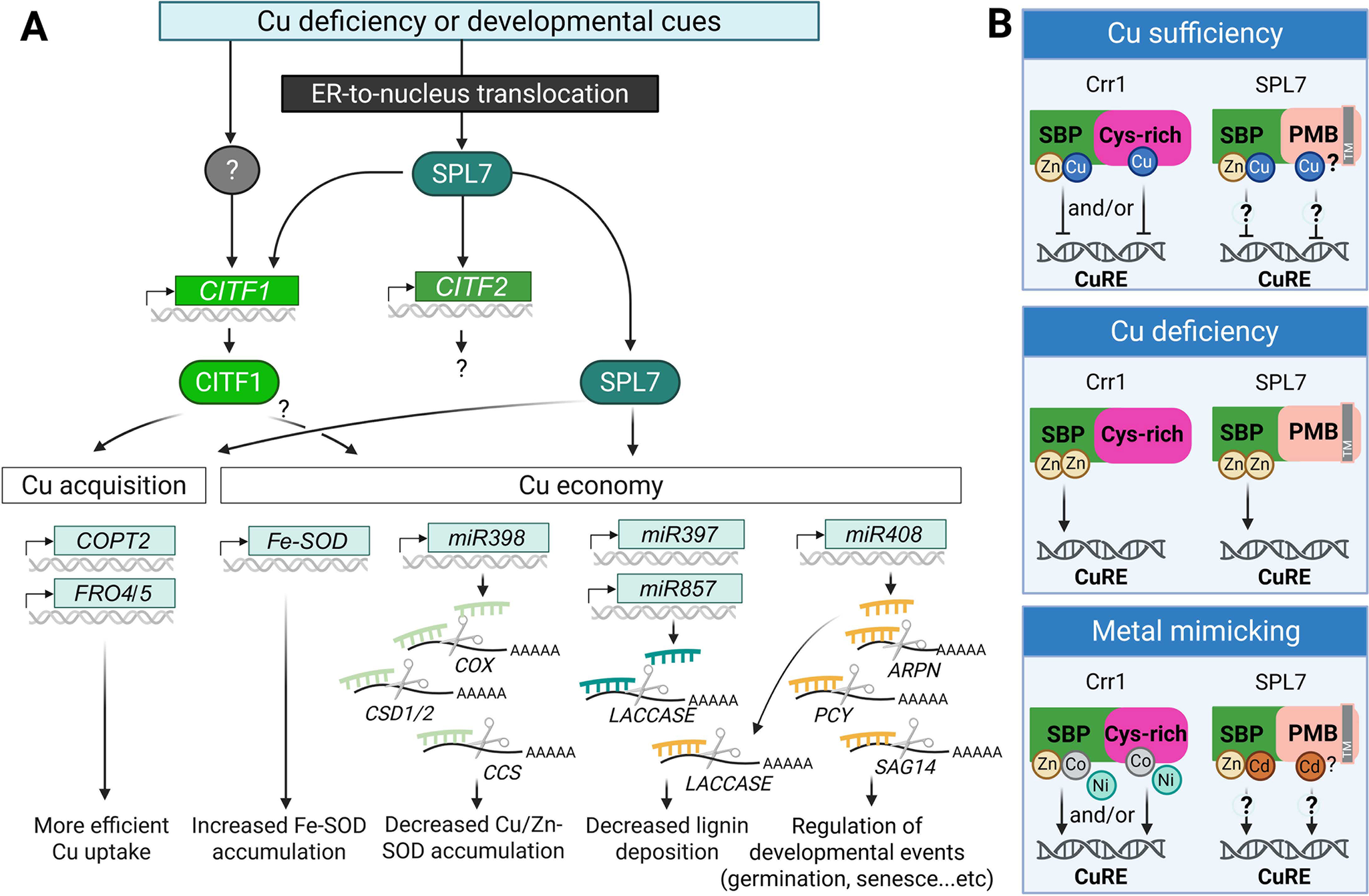

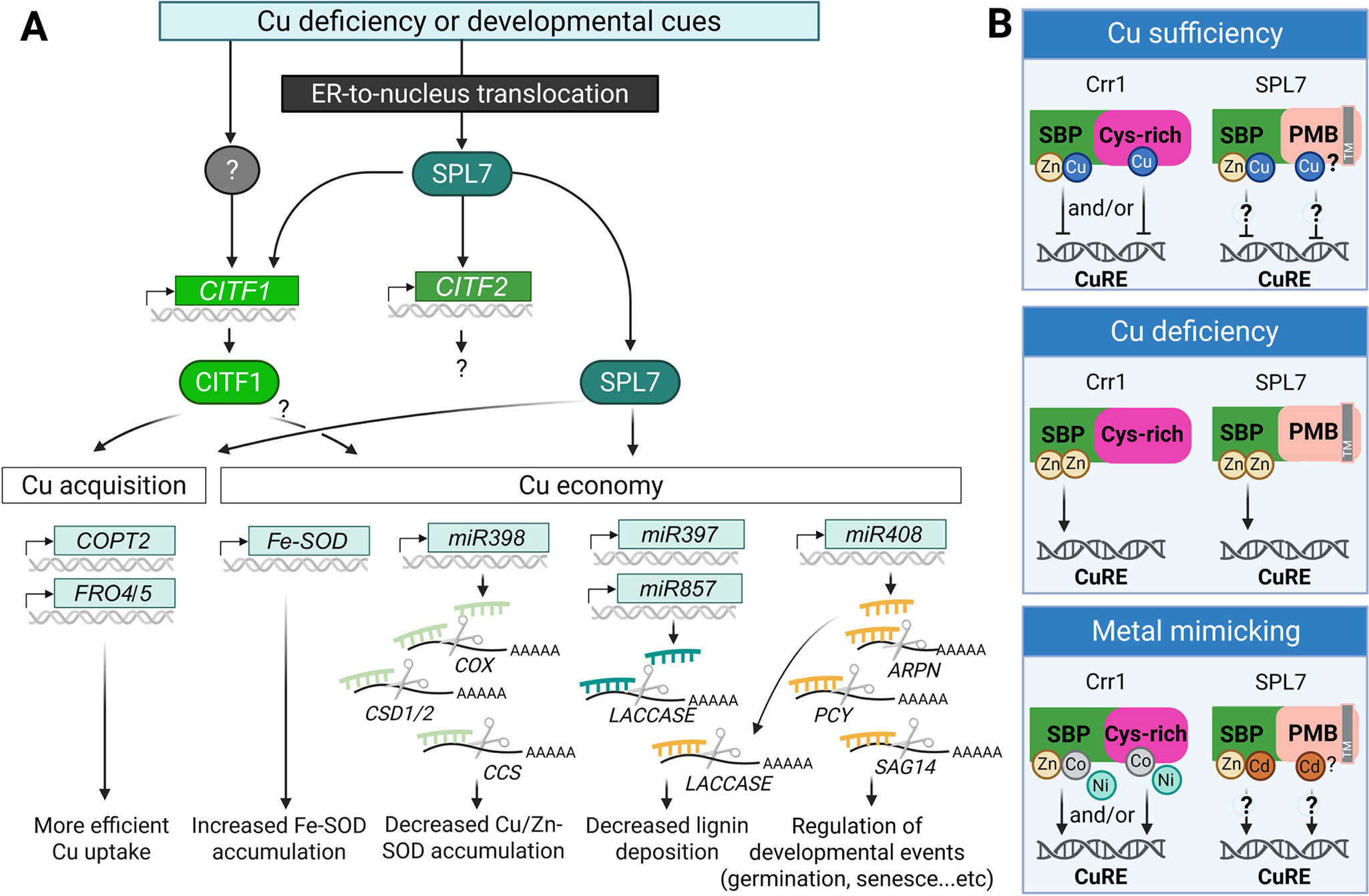

Figure 3. Summary of transcriptional Cu deficiency response based on studies in A. thaliana.

(A) Cu deficiency responses are triggered by fluctuations in environmental Cu availability and/or developmental cues. The master regulator SPL7 is translocated from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane to the nucleus, where it activates a Cu deficiency response cascade. This includes the induction of CITF1, CITF2, and downstream genes involved in Cu acquisition and Cu economy. CITF1 expression is partially dependent on SPL7 and may also be regulated by yet unidentified transcription factors. SPL7 and CITF1 co-regulate several Cu uptake-related genes, including COPT2, FRO4 and FRO5. The Cu economy is primarily governed by SPL7, and potentially by CITF1. Under Cu-deficient conditions, FeSOD (FSD1) expression is upregulated to substitute for Cu/Zn-SOD, CSD1/2. A set of Cu-responsive microRNAs is also activated to degrade mRNAs encoding Cu-dependent proteins, such as CSD1/2, COX, CSS, Laccases, ARPN and a pair of interacting plantacyanin proteins (plantacyanin [PCY] and senescence-associated gene 14 [SAG14]), thereby reducing overall Cu consumption.

(B) Speculative models for AtSPL7/Crr1 Cu status sensing (based on Gayomba et al., Reference Gayomba, Jung, Yan, Danku, Rutzke, Bernal, Kramer, Kochian, Salt and Vatamaniuk2013; Kropat et al., Reference Kropat, Tottey, Birkenbihl, Depège, Huijser and Merchant2005). Under Cu sufficiency, Cu may replace Zn in the SBP domain in Crr1 and AtSPL7 and/or bind the C-terminal Cys-rich region in Crr1, altering the transcription factor’s structure to prevent binding to the Cu response element (CuRE). Under Cu deficiency, Zn may replace Cu in the SBP domain and/or induce structural changes that promote CuRE binding. Excess of other divalent metal ions (e.g., Cd2+, Ni2+ and Co2+) may mimic Zn function and also facilitate interaction with CuRE. While the Crr1’s Cys-rich domain is not conserved in AtSPL7, the C-terminal half of AtSPL7 contains four potential metal-binding (PMB) sites in addition to multiple Cys and His residues. Their role in metal binding and Cu sensing is yet to be determined. A grey box labelled (TM) in SPL7 indicates the transmembrane domain. The figure was created with BioRender.com.

SPL7 also governs the Cu economy/metal switch mechanism, which prioritizes Cu use for essential functions under Cu deficiency. This mechanism involves miRNAs that target genes encoding abundant and functionally redundant Cu proteins. Their depletion is compensated by the isoforms that utilize other metals, most commonly iron (Fe) (Burkhead et al., Reference Burkhead, Gogolin Reynolds, Abdel-Ghany, Cohu and Pilon2009). For example, miR398, a direct SPL7 target, is transcriptionally upregulated under Cu deficiency and targets CSD1 and CSD2, and their chaperone CCS. At the same time, the expression of FSD1, an Fe-dependent isoform and direct SPL7 target, increases (Cohu & Pilon, Reference Cohu and Pilon2007; Schulten et al., Reference Schulten, Pietzenuk, Quintana, Scholle, Feil, Krause, Romera-Branchat, Wahl, Severing, Coupland and Krämer2022; Yamasaki et al., Reference Yamasaki, Abdel-Ghany, Cohu, Kobayashi, Shikanai and Pilon2007; Yamasaki et al., Reference Yamasaki, Hayashi, Fukazawa, Kobayashi and Shikanai2009). Other SPL7-regulated miRNAs include miR397b, miR408, miR853a, miR857a and miR860a. These miRNAs collectively downregulate genes encoding several non-essential or less critical Cu proteins, including CSDs, CCS and COX subunit 5b (miR398); laccases (miR397, miR408 miR857); plantacyanins, ARPN and PCY and senescence-associated proteins such as SAG14 (miR408). This process allows for prioritizing Cu allocation to essential cellular functions, a regulatory mechanism often referred to as the Cu economy/metal switch model (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Casero, Singh, Wilson, Grande, Yang, Dodani, Pellegrini, Huijser, Connolly, Merchant and Krämer2012; Cohu et al., Reference Cohu, Abdel-Ghany, Gogolin Reynolds, Onofrio, Bodecker, Kimbrel, Niyogi and Pilon2009; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Yang, Du, Deng and Li2022; Pilon, Reference Pilon2017; Sunkar et al., Reference Sunkar, Kapoor and Zhu2006; Yamasaki et al., Reference Yamasaki, Abdel-Ghany, Cohu, Kobayashi, Shikanai and Pilon2007; Yamasaki et al., Reference Yamasaki, Hayashi, Fukazawa, Kobayashi and Shikanai2009).

While CITF1 transcript levels increase under Cu deficiency and decrease under sufficiency, partially in an SPL7-dependent manner, AtSPL7 itself is expressed constitutively, suggesting its posttranscriptional regulation under Cu deficiency (Shikanai et al., Reference Shikanai, Müller-Moulé, Munekage, Niyogi and Pilon2003; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Chia, Sheng, Jung, Zavodna, Zhang, Huang, Jiao, Craft, Fei, Kochian and Vatamaniuk2017). Unlike other SPL family members, the A. thaliana SPL7 contains a 20-amino-acid C-terminal transmembrane domain (TMD) in addition to the characteristic SBP domain with a functional bipartite nuclear localization signal (Garcia-Molina et al., Reference Garcia-Molina, Xing and Huijser2014). Under Cu-sufficient conditions, the TMD anchors AtSPL7 to the ER, preventing its nuclear localization and transcriptional activity. Under Cu deficiency, AtSPL7 undergoes proteolytic cleavage, releasing the SBP domain-containing N-terminal fragment, which translocates to the nucleus to activate target genes. Furthermore, this N-terminal fragment can homodimerize, forming complexes too large to pass through the nuclear pore, thereby offering an additional regulatory layer over AtSPL7 activity (Garcia-Molina et al., Reference Garcia-Molina, Xing and Huijser2014).

AtSPL7, anchored via TMD to ER, also interacts with RAN1, a Cu transporter that is required for Cu transfer to ethylene receptors; the TMD of AtSPL7 is required for regulating RAN1 abundance and ethylene sensitivity (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Hao, Du, Xu, Guo, Li, Cai, Guo and Li2022) and (Figure 1). Whether and how AtSPL7-RAN1 interaction modulates RAN1-based Cu delivery to ethylene receptors is yet to be determined.

The molecular components regulating Cu homeostasis in grasses remain poorly defined, but recent findings indicate that rice exhibits a partially conserved Cu economy strategy while also employing a conserved SPL7-like system to orchestrate the Cu deficiency response (Navarro et al., Reference Navarro, Del Frari, Dias, Lemainski, Mario, Ponte, Goergen, Tarouco, Neves, Dressler, Fett, Brunetto, Sperotto, Nicoloso and Ricachenevsky2021). For example, the expression of Cu-miRNA homologs in rice, such as OsmiR397, OsmiR398b and OsmiR408, is significantly upregulated under Cu deficiency, whereas the expression of CSD homologs (OsCSD2/3/4) is downregulated. However, Cu deficiency does not upregulate OsFSD genes or suppress the expression of OsCCS, which highlights the unique features of the Cu economy response in rice (Navarro et al., Reference Navarro, Del Frari, Dias, Lemainski, Mario, Ponte, Goergen, Tarouco, Neves, Dressler, Fett, Brunetto, Sperotto, Nicoloso and Ricachenevsky2021).

The regulatory network of Cu homeostasis in grasses is further depicted by functional analyses of OsSPL9, the closest rice homolog of AtSPL7 (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Luo, Shi, Song, Wang, Chen, Shen, Rouached and Zheng2024). Loss-of-function mutants of OsSPL9 display increased sensitivity to Cu deficiency, reduced Cu accumulation in shoots, and impaired Cu distribution to newly developing leaves, underscoring its importance for Cu resilience. OsSPL9 directly binds to GTAC motifs in the promoters of multiple Cu uptake and transport genes, including OsCOPT1/5/6/7 and OsYSL16, as well as genes encoding Cu-responsive miRNAs such as OsmiR397, OsmiR398, OsmiR408 and OsmiR528, thereby promoting Cu uptake, root-to-shoot translocation, and the Cu economy response (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Wu, Bai, Zhang, Zhang, Yao, Yang, Chen, Liu, Li, Zhou and Liu2025; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Luo, Shi, Song, Wang, Chen, Shen, Rouached and Zheng2024). Together, these findings position OsSPL9 as a functional equivalent of Arabidopsis SPL7 and highlight the conservation of SPL7-based Cu regulatory modules across monocots and dicots.

4. Cu sensing and signalling mechanisms

4.1. Local sensing of Cu availability

Our understanding of Cu sensing originates from studies in bacteria and green algae, C. reinhardtii. In Escherichia coli, cytoplasmic Cu sensors like CueR, CsoR and CopY modulate DNA binding in response to Cu ions (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Jacobsen and Giedroc2009; Stoyanov et al., Reference Stoyanov, Hobman and Brown2001). When the cytosolic Cu level increases, metal binding to the sensor induces changes in the DNA binding region to promote or repress gene expression. These sensors have a high affinity for Cu ions and are highly sensitive to fluctuations of labile Cu concentration in the cells (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Jacobsen and Giedroc2009; Osman et al., Reference Osman, Martini, Foster, Chen, Scott, Morton, Steed, Lurie-Luke, Huggins, Lawrence, Deery, Warren, Chivers and Robinson2019). For example, the Cu binding affinity of CueR is 10−21 M (Changela et al., Reference Changela, Chen, Xue, Holschen, Outten, O’Halloran and Mondragón2003). E. coli also senses periplasmic Cu through two-component systems, for example, CusS–CusR (Outten et al., Reference Outten, Huffman, Hale and O’Halloran2001). CusS is a homodimeric histidine kinase sensor; CusR is the cognate cytosolic response regulator and has an N-terminal receiver domain that interacts with CusS and a C-terminal effector domain that binds DNA (Affandi et al., Reference Affandi, Issaian and McEvoy2016; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Sengupta, Genova, Santiago, Jung, Krzemiński, Chakraborty, Zhang and Chen2020). The equivalent systems in plants have not yet been discovered.

Early insights on Cu sensing in plants came from studies in C. reinhardtii, where Cu-response elements (CuREs) with GTAC core motifs were found in promoters of Cu-responsive genes (Kropat et al., Reference Kropat, Tottey, Birkenbihl, Depège, Huijser and Merchant2005; Quinn et al., Reference Quinn, Barraco, Eriksson and Merchant2000; Sommer et al., Reference Sommer, Kropat, Malasarn, Grossoehme, Chen, Giedroc and Merchant2010). These motifs are recognized by the Cu response regulator Crr1, a functional ortholog of AtSPL7 (Kropat et al., Reference Kropat, Tottey, Birkenbihl, Depège, Huijser and Merchant2005; Sommer et al., Reference Sommer, Kropat, Malasarn, Grossoehme, Chen, Giedroc and Merchant2010). Recent global ChIP-seq analysis refined the AtSPL7 recognition sites and supported the consensus GTACTRC motif in promoter regions of AtSPL7 targets primarily under low-Cu conditions (Schulten et al., Reference Schulten, Pietzenuk, Quintana, Scholle, Feil, Krause, Romera-Branchat, Wahl, Severing, Coupland and Krämer2022).

Both Crr1 and AtSPL7 contain a Zn-binding SBP domain, regarded as a putative metal-sensing region in Crr1 (Kropat et al., Reference Kropat, Tottey, Birkenbihl, Depège, Huijser and Merchant2005; Yamasaki et al., Reference Yamasaki, Hayashi, Fukazawa, Kobayashi and Shikanai2009) and (Figure 3B). In addition, Crr1 has four putative metal-binding CXXC motifs in the C-terminal region. These motifs are not conserved in AtSPL7 (Kropat et al., Reference Kropat, Tottey, Birkenbihl, Depège, Huijser and Merchant2005; Yamasaki et al., Reference Yamasaki, Hayashi, Fukazawa, Kobayashi and Shikanai2009). Crr1 binds to GTAC motifs via the SBP domain in a Zn-dependent manner under Cu deficiency. It is proposed that under sufficiency, Cu may displace Zn in the SBP domain and/or induce conformational changes via the C-terminal Cys-rich region, releasing Crr1 from the promoters of its targets (Kropat et al., Reference Kropat, Tottey, Birkenbihl, Depège, Huijser and Merchant2005). Crr1 is also affected by Ni and Co, which act antagonistically to Cu in regulating the expression of Crr1 targets, suggesting metal-specific modulation. Although a similar mechanism in AtSPL7 has not been fully established, Cd has been shown to antagonize Cu by activating AtSPL7 targets even under Cu sufficiency (Gayomba et al., Reference Gayomba, Jung, Yan, Danku, Rutzke, Bernal, Kramer, Kochian, Salt and Vatamaniuk2013). This supports the possibility that AtSPL7 may also act as a direct Cu sensor, potentially via Zn displacement in the SBP. Using the metal ion-binding site prediction and modelling server (MIB2, Lu et al., Reference Lu, Chen, Yu, Liu, Liu, Wei and Lin2022), we identified four potential Zn, Cu, Ni, Co and Cd binding sites: His475 Tyr477, His628Leu630, 662SDIHRKH668 and 644HCTCDCD650 at the C-terminal region. There are also two CCC motifs (residues 564–566 and 683–685), in addition to scattered Cys and His residues. Whether these residues are involved in metal binding and Cu status sensing by AtSPL7 is yet to be determined.

4.2. Systemic signalling of Cu deficiency

Beyond local regulation, plants integrate whole-plant Cu status through systemic signalling mechanisms. AtSPL7 monitors Cu availability locally, especially near the vasculature (Araki et al., Reference Araki, Mermod, Yamasaki, Kamiya, Fujiwara and Shikanai2018). However, roots can also respond to shoot Cu demands via long-distance signalling, and Cu levels in the phloem contribute to shoot-to-root communication (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023).

The strongest evidence for systemic Cu signalling comes from studies of AtOPT3, originally identified as an essential component of Fe homeostasis and signalling. AtOPT3 loads Fe into phloem companion cells; its disruption in opt3 mutants leads to constitutive Fe deficiency responses in roots and Fe accumulation in shoots due to a defect in Fe loading into phloem companion cells (Mendoza-Cózatl et al., Reference Mendoza-Cózatl, Xie, Akmakjian, Jobe, Patel, Stacey, Song, Demoin, Jurisson, Stacey and Schroeder2014; Stacey et al., Reference Stacey, Patel, McClain, Mathieu, Remley, Rogers, Gassmann, Blevins and Stacey2007; Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, Gayomba, Jung, Vimalakumari, Piñeros, Craft, Rutzke, Danku, Lahner, Punshon, Guerinot, Salt, Kochian and Vatamaniuk2014). Remarkably, this constitutive root Fe response can be repressed by Fe application to the shoot, indicating a phloem-mediated feedback signal (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023).

We recently demonstrated that AtOPT3 also transports Cu ions when expressed in Xenopus oocytes and S. cerevisiae (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023). The opt3-3 mutant exhibits lower Cu in the phloem sap and impaired Cu recirculation from source to sink tissues (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023). While the ability of AtOPT3 to transport Cu as well as Fe is not surprising, considering the recognized multispecificity of metal ion transporters, it was surprising to find, however, that the mutant also manifested the increased expression of Cu-deficiency marker genes in root tissues while overaccumulating Cu in the vascular tissues of the shoots (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023). Importantly, these defects are rescued by Cu application. Furthermore, Cu feeding via the phloem in the shoot rescued the molecular symptoms of Cu deficiency in the root of the wild-type and the opt3-3 mutant, suggesting the existence of long-distance shoot-to-root Cu signalling. This suggestion is further strengthened by results from reciprocal grafting experiments using wild-type and the opt3-3 mutant (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Yan, Rahmati Ishka, Faulkner, Simons, Huang, Smieska, Woll, Tappero, Kiss, Jiao, Fei, Kochian, Walker, Piñeros and Vatamaniuk2023). Thus, Cu availability in the shoot, mediated through phloem transport by AtOPT3, serves as a systemic signal to fine-tune root Cu uptake, ensuring balanced nutrient distribution across the plant. Interestingly, phloem-feeding with Cu in the shoot also rescued molecular symptoms of Fe deficiency in the root of the opt3-3 mutant and decreased the transcript abundance of molecular markers of Fe deficiency in the root of wild-type. Likewise, phloem-feeding with Fe in the shoot downregulated the expression of both Fe- and Cu-deficiency marker genes in the root of the opt3-3 mutant or wild-type, highlighting the complexity of the crosstalk between Cu and Fe in long-distance signalling. Together, these findings illustrate that Cu homeostasis in A. thaliana is maintained through a finely tuned network of local and systemic regulatory mechanisms. SPL7 emerges as a central integrator of Cu sensing and transcriptional responses, coordinating both Cu uptake and the economy/metal switch. In parallel, systemic signalling, mediated through phloem-localized transporters such as OPT3, ensures root Cu acquisition is aligned with whole-plant Cu status and is coordinated with Fe uptake and transport pathways.

5. Future perspectives

Although significant progress has been made in understanding Cu uptake strategies in non-grass species, the mechanisms underlying Cu uptake and long-distance transport in grasses remain incompletely defined. Multiple, potentially co-existing pathways for Cu acquisition, including direct uptake of Cu+ and Cu2+ and transport of Cu-ligand complexes, warrant further exploration. Furthermore, the identification of YSL transporters such as BdYSL3, which mediate Cu redistribution to reproductive tissues and influence grain size and protein content, underscores the need to investigate the role of Cu in shaping these essential agronomic traits. These studies would lay the groundwork for future exploration of the full suite of Cu transporters, ligands and regulatory networks that support Cu nutrition in cereal crops.

In addition to expanding our understanding of Cu uptake strategies across plant species, knowledge of internal Cu transport systems needs to be expanded as well. For example, the transporters responsible for Cu movement into and out of mitochondria have yet to be identified. Cu sensing mechanisms, roles of Cu in local and systemic signalling and molecular basis of crosstalk with other mineral nutrients, represent additional promising avenues of investigation. Continued exploration of these pathways will be critical for understanding how plants optimize Cu allocation under fluctuating environmental conditions.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/qpb.2025.10027.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and apologize to colleagues whose work was either not included due to a specific review focus or not cited due to space limitations.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability statement

This review article does not rely on original data or resources.

Funding statement

The research in the O.K.V. lab is currently funded by U.S. National Science Foundation (US-NSF) Division of Integrative Organismal Systems (IOS) Award#: 2430791; U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA) Award#: 2021-67013-33798 and Research Capacity Fund (HATCH) Award#: 2024-25-153, from the USDA-NIFA. T.O.Z.’s studies in the O.K.V. lab is funded by the USDA-NIFA Workforce Development Award#: 2021-67034-35124; J.C. is, in part, supported by the US-NSF Division of Biological Infrastructure (DBI) Award#: 2330043.

Comments

Dear Dale and Ingo,

Thank you very much for inviting my group to submit a review on copper homeostasis to be included in the special edition on Plant Ion Homeostasis in Quantitative Plant Biology. I apologize for the late submission and would like to thank you for your patience! I also apologize that the review turned out to be lengthier than intended. I hope this is OK. Please find attached our documents for the review entitled “Copper Connections: Coordinating Transport, Sensing, and Systemic Signaling in Plants”. I hope you find the review stimulating, as it not only overviews the existing literature but also taps into less-studied aspects of copper transport in grasses as well as emerging avenues for copper signaling.

Thank you very much,

With kind regards,

Olena