Introduction

The year 2020 was supposed to become a year of new parliamentary dynamics, given that the national elections in autumn 2019 had produced the largest shifts in the composition of Parliament for decades, most notably much higher shares of green and female MPs. However, in the first half of the year, party politics was put on hold when the Federal Council, in March 2020, and for the first time in its history, declared the ‘extraordinary situation’ under the Federal Law of Epidemics. While in June this situation was downgraded to the ‘special situation’ and Parliament and party politics regained relevance and visibility in the second half of the year, the pandemic clearly dominated many aspects of the political life in 2020.

Election report

No national elections were held in Switzerland. However, cantonal (subnational) elections took place in the cantons of Uri, Schwyz, Basel-Stadt, Schaffhausen, St Gallen, Thurgau, Aargau and Jura. In all these cantonal elections but Uri, the green parties, and especially the Green Liberal Party/Grünliberale Partei/Parti vert'libéral (GLP/PVL) was able to make considerable gains in its vote shares. Hence, the ‘green wave’ of the national elections 2019 was continued at the subnational level in 2020. Even though it was sometimes less pronounced than at the national level, it is noteworthy that substantial green gains could be observed even in some conservative cantons such as St Gallen or Thurgau.

Referendums

The quarterly dates of federal votes are fixed and announced in advance. In 2020, only three dates were used, with Swiss voters deciding on nine ballot proposals (Tables 1–3). In the context of the pandemic, the Federal Council cancelled the votes scheduled in May, which led to a ‘super voting day’ in the autumn with five proposals being decided on the same day.

Table 1. Results of all popular initiatives and referendums on 9 February 2020

Source: The Federal Chancellery 2021.

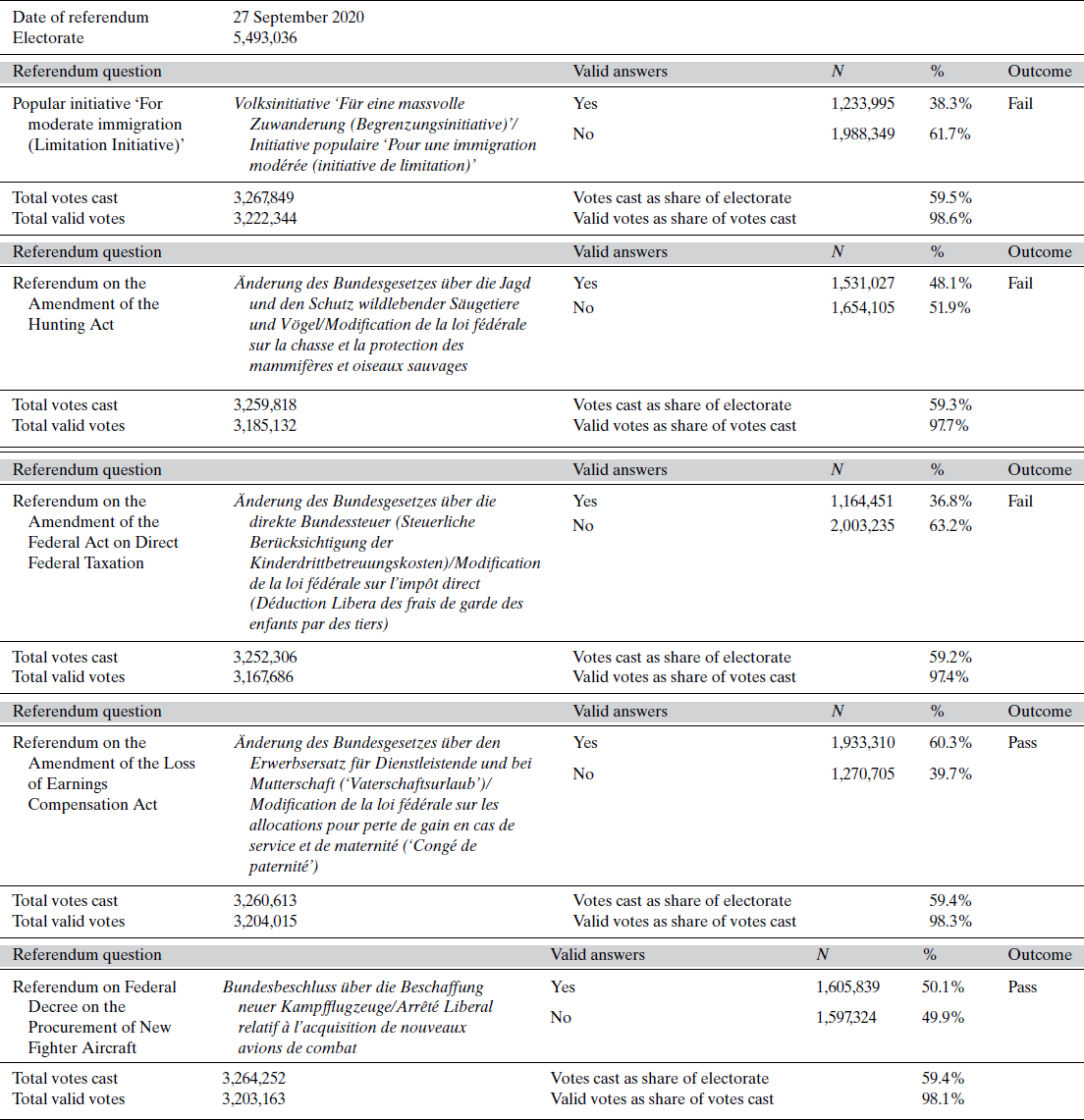

Table 2. Results of all popular initiatives and referendums on 27 September 2020

Source: The Federal Chancellery 2021.

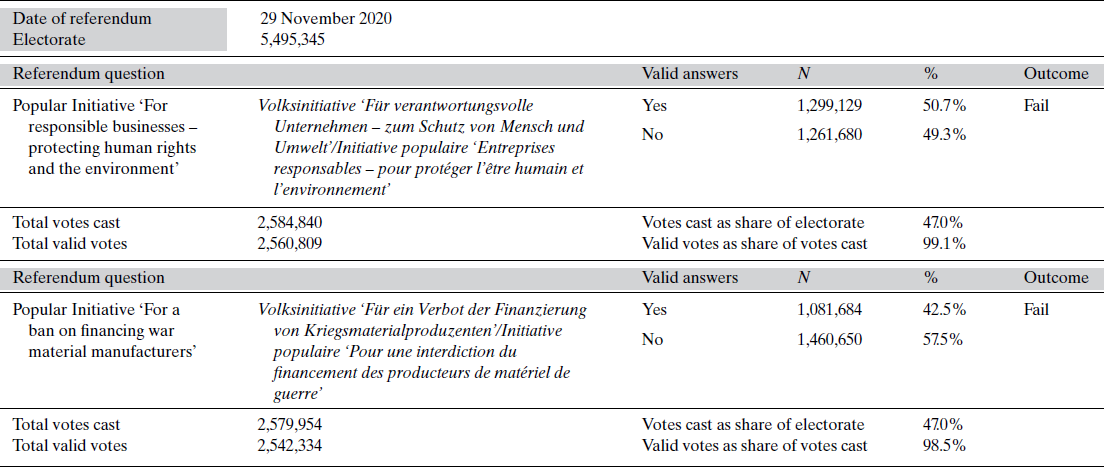

Table 3. Results of all popular initiatives and referendums on 29 November 2020

Source: The Federal Chancellery 2021.

The first ballot votes of the year took place on 9 February. The popular Initiative on More Affordable Homes asked the Confederation and the cantons to promote affordable housing more strongly. As one of the main measures, the initiative proposed that at least 10 per cent of newly built apartments should belong to non-profit developers. The initiative was clearly rejected with only 42.9 per cent of voters and four-and-a-half cantons supporting it. However, the post-ballot survey revealed that a clear majority supported the core aim of the proposal, namely more affordable housing, but feared that the new policy would not take into account regional disparities (Bernhard & Scaperrotta Reference Bernhard and Scaperrotta2020).

The second proposal of the day was a Referendum on the Ban on Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation. In 2018, Parliament had decided to extend the anti-racism penal code to include discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The referendum was called for by members of the Swiss People's Party/Schweizerische Volkspartei/Union démocratique du centre (SVP/UDC) and the Eidgenössisch-Demokratische Union/Union Démocratique Fédérale (EDU/UDF). However, the new law, and relatedly the commitment to a tolerant society (Bernhard & Scaperrotta Reference Bernhard and Scaperrotta2020), was supported by all major parties but the SVP/UDC, and also received a clear yes-majority of 63.1 per cent at the ballot.

Turnout on 9 February was relatively low at 41.7 per cent, which might also reflect a moderate campaign intensity.Footnote 1 Conversely, the ‘super voting day’ on 27 September generated an exceptionally high turnout rate of 59.9 per cent. The five proposals covered rather diverse topics, most moreover involving rather fundamental and emotional questions. This strongly mobilized green–leftist voters, those with high education and income and those in urban centres (Milic et al. Reference Milic, Feller and Kübler2020: 7).

One driver of high turnout was the so-called Limitation Initiative that demanded the end of free movement of persons with the European Union (EU). The initiative was a continuation of an ongoing debate on the potential trade-off between bilateral agreements with the EU and Switzerland's autonomy to limit immigration. Launched by members of the SVP/UDC and the Aktion für eine unabhängige und neutrale Schweiz/Action pour une Suisse Indépendante et Neutre (AUNS/ASIN), this new initiative targeted more directly the core of this trade-off, namely the free movement of persons. Initially scheduled for May 2020 and postponed to September 2020 due to the pandemic, the result was surprisingly clear: 61.7 per cent of voters casted a no-vote, and only in four cantons did the proposal obtain majority support. While previous votes on similar topics (namely the mass immigration initiative in 2014) were decided on small margins, this decision revealed that the bilateral agreements with the EU are given clear priority over autonomy in immigration control (Milic et al. Reference Milic, Feller and Kübler2020: 5).

The second proposal was a referendum on the Amendment of the Hunting Act, which centred on new rules for dealing with wolves (but also included regulations on other wild animals). The referendum was called for by nature conservation associations, and it triggered an intensive and emotional campaign. At the ballot, 51.8 per cent of voters rejected the amendment. Large differences in voting behaviour occurred between the Alpine cantons, where almost 70 per cent of voters casted a yes-vote, and the midland and urban cantons, where clear majorities opposed the new law (Milic et al. Reference Milic, Feller and Kübler2020: 24).

On the same day, the citizenry also rejected an Amendment of the Federal Act on Direct Federal Taxation with 63.2 per cent of no-votes. Initially, the Federal Council had conceptualized the amendment, namely an increased tax deduction for childcare costs, as a measure to improve the reconciliation between family duties and employment. However, in the parliamentary process, the centre-right majority added a general tax deduction for children to the proposal, which let the Social Democrats/Sozialdemokratische Partei/Parti Socialiste (SPS/PSS) to call for the referendum (Strasser Reference Strasser2020). The party's main argument against the amendment, namely that only high-income households would profit form the tax deductions, was also the main reason for voters to reject it on the ballot (Milic et al. Reference Milic, Feller and Kübler2020: 34).

The fourth referendum on the Referendum on the Amendment of the Loss of Earnings Compensation Act was in fact a vote on the Introduction of a Two-Week Paternity Leave. The proposal was a direct counterproposal to the withdrawn popular initiative ‘Paternity leave now’ and triggered opposition mainly among the right-wing parties (Milic et al. Reference Milic, Feller and Kübler2020: 38). However, 60.3 per cent of voters and a majority of cantons approved the amendment on the ballot, whereas 10 cantons from the eastern and centre parts of the country still rejected the paternity leave.

The fifth ballot proposal was embedded in a longer debate on the purchase of new fighter aircraft, regarding which the electorate had rejected a proposal in 2014. The new decree allocated a maximum of 6 billion Swiss francs to this project without, however, specifying the particular type of fighter aircraft that should be purchased. The main conflict occurred – as in previous ballot decision on military questions – along the left–right divide, and produced a very close result with 50.1 per cent yes-votes and a margin of fewer than 9000 votes (Milic et al. Reference Milic, Feller and Kübler2020: 46). Remarkably, the new and first female Defence Minister, Viola Amherd, became heavily involved in the campaign and managed to gain sympathy for herself and therewith for the bill (Milic et al. Reference Milic, Feller and Kübler2020).

On 29 November, voters decided on two ballot proposals that covered ethical, social and sustainability issues in a global context.

The popular Initiative for Responsible Businesses, launched by more than 60 non-governmental organizations (NGOs), demanded that Swiss companies should examine their as well as their subsidiaries’ suppliers’ and business partners’ compliance with internationally recognized human rights and environmental standards. The government and Parliament opposed the initiative arguing that the proposed liability rules went too far. While the proposal received a small majority in the popular vote (50.7 per cent), it failed to win a majority of the cantons. It was only the second time since the introduction of female suffrage that this combination of popular majority and cantonal minority led to the rejection of an initiative (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz and Rötheli2021).

The last ballot proposal of the year concerned a Ban on the Financing of All War Material including credits for material producers and the ownership of their shares. While support for this initiative was again strong at the left, it was clearly rejected among centre and rightist voters. Nevertheless, the yes-share of 42.6 per cent can be considered high compared with previous initiatives in the field of war and peace (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz and Rötheli2021).

While turnout on that voting day was almost 10 percentage points lower than in September 2020, it was the first time in history that women exhibited a higher turnout rate than their male counterparts (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz and Rötheli2021). This exceptional gender composition of the electorate was accompanied by a substantial gender gap in voting behaviour. A total of 57 per cent of women supported the initiative for responsible businesses, while only 43 of male voters did so. Similarly, almost every second female voter accepted the ban on financing war material manufacturers at the ballot, whereas only every third male voter cast a yes-vote (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz and Rötheli2021).

Cabinet report

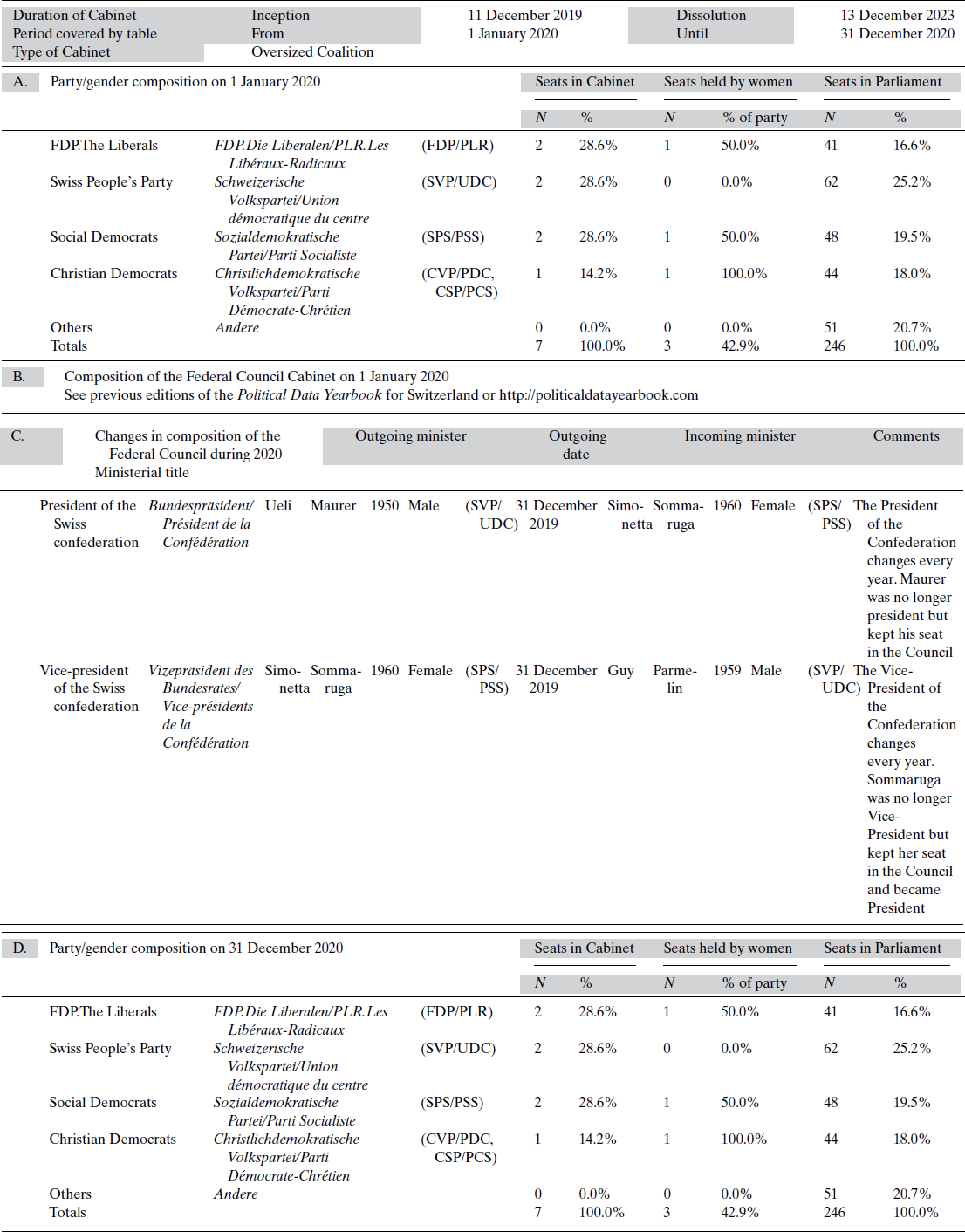

On 11 December 2019, after the national elections, all members of the coalition government in Switzerland had been re-elected by Parliament and remained in office during 2020. On the same day, Parliament also elected the Federal President and Vice-President for 2020 as these positions rotate annually among the members of the Cabinet. For the second time in her career, Simonetta Sommaruga (SPS/PSS) was elected as Federal President with 186 out of 200 valid votes. Guy Parmelin (SVP/UDC) was nominated as Vice-President and received 168 of 183 votes.

Table 4. Cabinet composition of the Federal Council in Switzerland in 2020

Notes: Parliament here is named Vereinigte Bundesversammlung and consists of the seats in both chambers (the upper and the lower house).

The Cabinet is an Oversized Coalition, but not every faction that has seats in Parliament has a federal councillor.

Whereas members of the Federal Council are elected individually and have been in office for different periods of time, every four years after the national elections all members of the Federal Council are re-elected the same day. Hence, the inception of the 2020 Federal Council was on 11 December 2019, and unless a member resigns, it is elected for a period of four years.

Parliament report

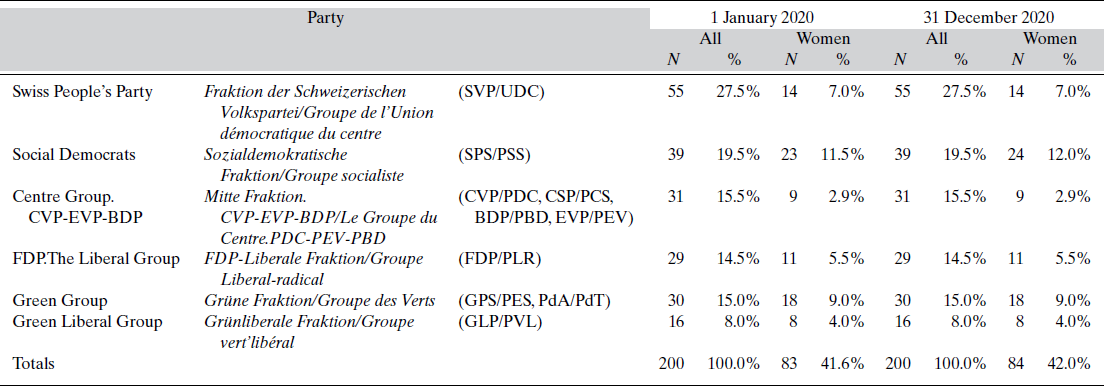

As 2020 was the first year of the legislative term, no major changes in Parliament occurred and only three members of the lower house of the Parliament (National Council) had to be replaced. Two persons left the national Parliament because they were elected to the governments of their home cantons, and one person died.

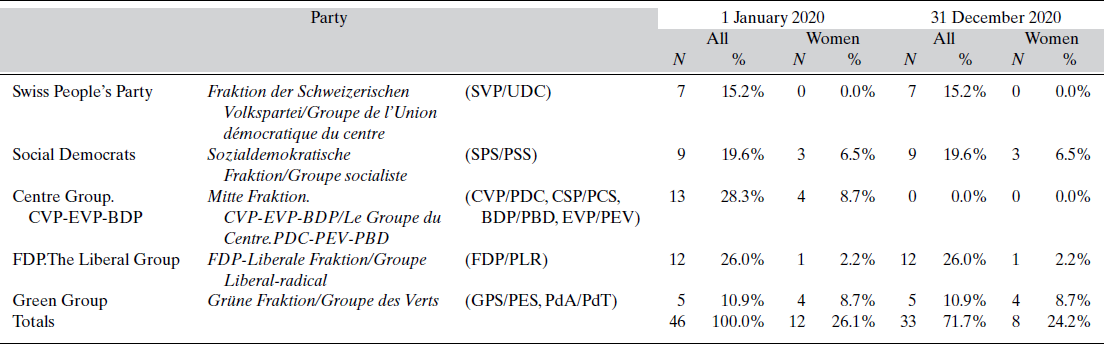

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat/Conseil national) in Switzerland in 2020

Notes: Parliamentary groups are not identical to political parties. For more information, see https://www.parlament.ch/en/organe/groups.

After the elections 2019, the Conservative Democratic Party (BDP/PBD) formed together with the former Christian Democratic Fraction (CVP/PDC, CSP/PCS and EVP/PEV) the new “The Center Group. CVP-EVP-BDP.”

Source: The Federal Assembly – The Swiss Parliament (2021).

Table 6. Party and gender composition of the upper house of Parliament (Ständerat/Conseil des États) in Switzerland in 2020

Notes: Parliamentary groups are not identical to political parties. For more information, see https://www.parlament.ch/en/organe/groups.

After the elections 2019, the Conservative Democratic Party (BDP/PBD) formed together with the former Christian Democratic Fraction (CVP/PDC, CSP/PCS and EVP/PEV) the new “The Center Group. CVP-EVP-BDP.”

Source: The Federal Assembly – The Swiss Parliament (2021).

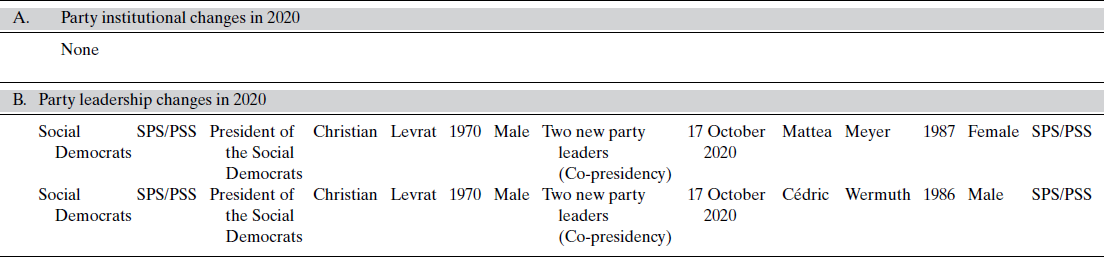

Table 7. Changes in political parties in Switzerland in 2020

Notes: Mattea Meyer and Cédric Wermuth lead the party as a co-presidency.

Source: The Federal Assembly – The Swiss Parliament (2021).

Political party report

On 17 October 2020, the delegates of the SPS/PSS had to elect a new party leader to replace Christian Levrat, who had led the party for 12 years. As a novelty in the party history, Mattea Meyer and Cédric Wermuth were elected as co-presidents.

Moreover, in 2020, the Christian Democratic People's Party/Christlichdemokratische Volkspartei/Parti Démocrate-Chrétien (CVP/PDC) and the Bürgerlich-Demokratische Partei/Parti bourgeois démocratique (BDP/PBD) decided to merge to a new joint party called ‘The Centre’. Even though the party would not exist as such until January 2021, the main decisions of this merger were taken in 2020. On 28 November 2020, over 80 per cent of the delegates of the CVP/PDC (and, thus, clearly more than the required two-thirds) decided to rename their party and merge with the BDP/PBD. The delegates of the latter had agreed on the merger two weeks before.

The BDP/PBD was only formed in 2008 as a split from the SVP/UDC. After some short-term successes, the party has steadily lost vote share in recent years. After the 2019 elections, the party no longer had the right to form its own parliamentary group and therefore joined the former Christian Democratic group (CVP/PDC, CSP/PCS and EVP/PEV) to form the new ‘Centre Group. CVP-EVP-BDP’. From this perspective, the formal merger seems not to be a big deal.

However, the situation is different from the perspective of the CVP/PDC. Since the 19th century, this party has been the dominant party in the conservative cantons and for a long time formed the main counterweight to the liberal forces in Switzerland (Bochsler Reference Bochsler2013). Moreover, having emerged from the ‘Kulturkampf’, the ‘Christian’ in the party's name has for long formed one of its identifying elements. Hence, the decision to merge, and most important, to change name is indeed historic for this party.Footnote 2

Institutional change report

There were no major institutional changes in 2020.

Issues in national politics

Not surprisingly, the pandemic, and how to deal with it, were the dominant issues in national politics. In a first phase, when the Federal Council declared the ‘extraordinary situation’ in March 2020 and put the most restrictive measures into force, the fight against the pandemic was extraordinarily depoliticized. All parties represented in Parliament even signed a joint media release supporting the Federal Council and its measures. However, only a few months later, ‘pandemic politics’ became a new issue in Swiss politics. The lines of conflict run along the left–right axis with left parties more strongly supporting stricter measures and rightist parties asking for a more rapid relaxation of measures such as the closure of shops and restaurants. Conversely, the extensive public expenditures to cushion the pandemic, namely short-time work compensation and emergency aid for companies, were hardly the subject of party-political disputes.

Related to the pandemic, the distribution of competencies between the Confederation and the cantons was a recurring topic of discussion. While in normal times cantons in Switzerland enjoy a high degree of autonomy (Linder & Vatter Reference Linder and Adrian2001), especially in health, education and social policy, the Federal Law of Epidemics allows for a considerable shift of powers to the federal government in ‘extraordinary’ or ‘special’ times. The test case of the Covid-19 pandemic, with the special and extraordinary times being in place for months, revealed that decision-making under this unusual distribution of competencies is conflictual.

Finally, while the year had started with the premise that climate change policy would be the dominant political matter, the pandemic shifted priorities. However, it did not completely displace the climate issue, which remained prominent in the political and public debate.

Acknowledgement

Open Access Funding provided by Universitat Bern.