Introduction: theoretical and research basis for treatment

Specific phobia of vomiting (SPOV), also known as emetophobia, falls under the umbrella diagnosis of Specific Phobia in the ICD11 (World Health Organization, 2022). It is characterised by a ‘marked and persistent fear of vomiting that is excessive or unreasonable, cued by the presence of vomit or anticipation of vomiting’ (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Veale, Reference Veale2009). SPOV is often chronic and pervasive and is characterised by numerous safety-seeking behaviours including checking the freshness of food, avoiding alcohol, certain food types, drunk or sick people, excessive washing of hands or food, carrying or taking anti-sickness medication and trying to tightly control one’s behaviour, all of which negatively impact daily functioning (Fairbrother et al., Reference Fairbrother, Janssen, Antony, Tucker and Young2016; Lipsitz et al., Reference Lipsitz, Fyer, Paterniti and Klein2001; Veale and Lambrou, Reference Veale and Lambrou2006).

The prevalence of a fear of vomiting is estimated at around 7% in females and 1.8% in males within community samples (van Hout and Bouman, Reference van Hout and Bouman2012). Estimates of clinical prevalence of emetophobia tend to be lower, with a lifetime prevalence rate of around 0.2% (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Goodwin, Kause, Margraf, Neumer, Rinck and Türke2007). This, however, may be an under-estimation due to misdiagnosis or diagnostic overshadowing; there is a high co-morbidity of emetophobia with panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), agoraphobia and social phobia (van Hout and Bouman, Reference van Hout and Bouman2012; Veale, Reference Veale2009).

SPOV often develops in childhood and has a typical duration of 25 years before seeking treatment, therefore impacting many women during their reproductive years. (Lambrou and Veale, Reference Lambrou and Veale2006; van Hout and Bouman, Reference van Hout and Bouman2012). Due to the high prevalence of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (70–80%; Lee and Saha, Reference Lee and Saha2011)), in one study of 94 people with SPOV, 49% had avoided pregnancy and 5% had terminated a pregnancy due to their phobia (Lambrou and Veale, Reference Lambrou and Veale2006).

The evidence base is limited for the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for treating SPOV, and studies typically contain small sample sizes. However, within the limited evidence base, CBT is supported over other treatments. In a small (n=24), randomised control trial, Veale’s (Reference Veale2009) protocol for treating SPOV was found to be significantly more effective than a waitlist control, with 50% of patients achieving reliable and significant change after 12 hour-long sessions, and with treatment gains maintained at follow-up (Riddle-Walker et al., Reference Riddle-Walker, Veale, Chapman, Ogle, Rosko, Najmi, Walker, Maceachern and Hicks2016). Challacombe et al. (Reference Challacombe, Orme and Roxborough2022) outlined two treatment cases of SPOV in mothers of young children and found CBT to be effective when using Veale’s (Reference Veale2009) protocol. Using a single case experimental design, Keyes et al. (Reference Keyes, Deale, Foster and Veale2020) trialled a time intensive format of CBT for treating SPOV with good results; seven out of eight participants showed reliable improvement, with five showing clinically significant change on the Specific Vomit Phobia Inventory (SPOVI). Finally, a systematic review into the characteristics, assessment measures and treatment of SPOV by Keyes et al. (Reference Keyes, Gilpin and Veale2018) reviewed four treatment studies, three of which used CBT in adults, and found both individual and group CBT effective at reducing SPOV symptoms, anxiety and depression with good effect sizes, maintained at follow up (Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Gilpin and Veale2018).

Thus far, no evidence exists on the effectiveness of CBT for treating SPOV during pregnancy. This is an important area of research; for women with SPOV the link between pregnancy and nausea may result in significant anxiety during this period. Some studies examining the impact of maternal anxiety in pregnancy have found it to be associated with more difficult infant temperament, increased odds for pre-term birth and lower birth weight, yet it is important to note that this research has not examined the impact of anxiety caused by SPOV specifically (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Wu, Xu, Zhu, Jia, Zhang, Huang, Zhu, Hao and Tao2014; Thiel et al., Reference Thiel, Iffland, Drozd, Haga, Martini, Weidner, Eberhard-Gran and Garthus-Niegel2020). Furthermore, the safety behaviours associated with SPOV such as food restriction could have implications for infant outcomes, although this has not yet been investigated in the research.

Healthcare practitioners and patients often adopt a ‘better safe than sorry’ attitude, focusing on the potential risks of treatment to the foetus rather than the risks of failing to intervene, including the impact on maternal mental health, while propagating the idea that all negative outcomes are avoidable (Lyerly et al., Reference Lyerly, Mitchell, Armstrong, Harris, Kukla, Kuppermann and Little2009). As a result, pregnant women are often excluded from trials of exposure therapy, e.g. in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment, reducing the evidence base available to advocate for such treatment during pregnancy and leaving many therapists feeling reluctant to treat pregnant women using exposure-based therapy (Hendrix et al., Reference Hendrix, Sier, Baas and van Pampus2022; Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Miller, Soibatian, Otwell, Rufa, Meyer and Shalowitz2020).

This reluctance of therapists may not be warranted. In a recent treatment trial by Challacombe et al. (Reference Challacombe, Tinch-Taylor, Sabin, Potts, Lawrence, Howard and Carter2024), exposure-based CBT was delivered to pregnant women with anxiety-related disorders with good results that were sustained over the course of pregnancy. Qualitatively, many participants highlighted the importance of the exposure work in helping them to face their fears and progress towards their goals (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Tinch-Taylor, Sabin, Potts, Lawrence, Howard and Carter2024). Moreover, offering evidence-based, disorder-specific treatments for women with anxiety disorders during pregnancy is currently recommended by the NICE Guidelines for antenatal and postnatal mental health (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014; latest update 2020). It is important to note, however, that there is not specific NICE guidance for treating SPOV in pregnant women. The current study aims to add to the existing literature to support the delivery of exposure-based protocols during pregnancy, applying and adapting Veale’s (Reference Veale2009) model to treatment of SPOV in a pregnant client.

Case material

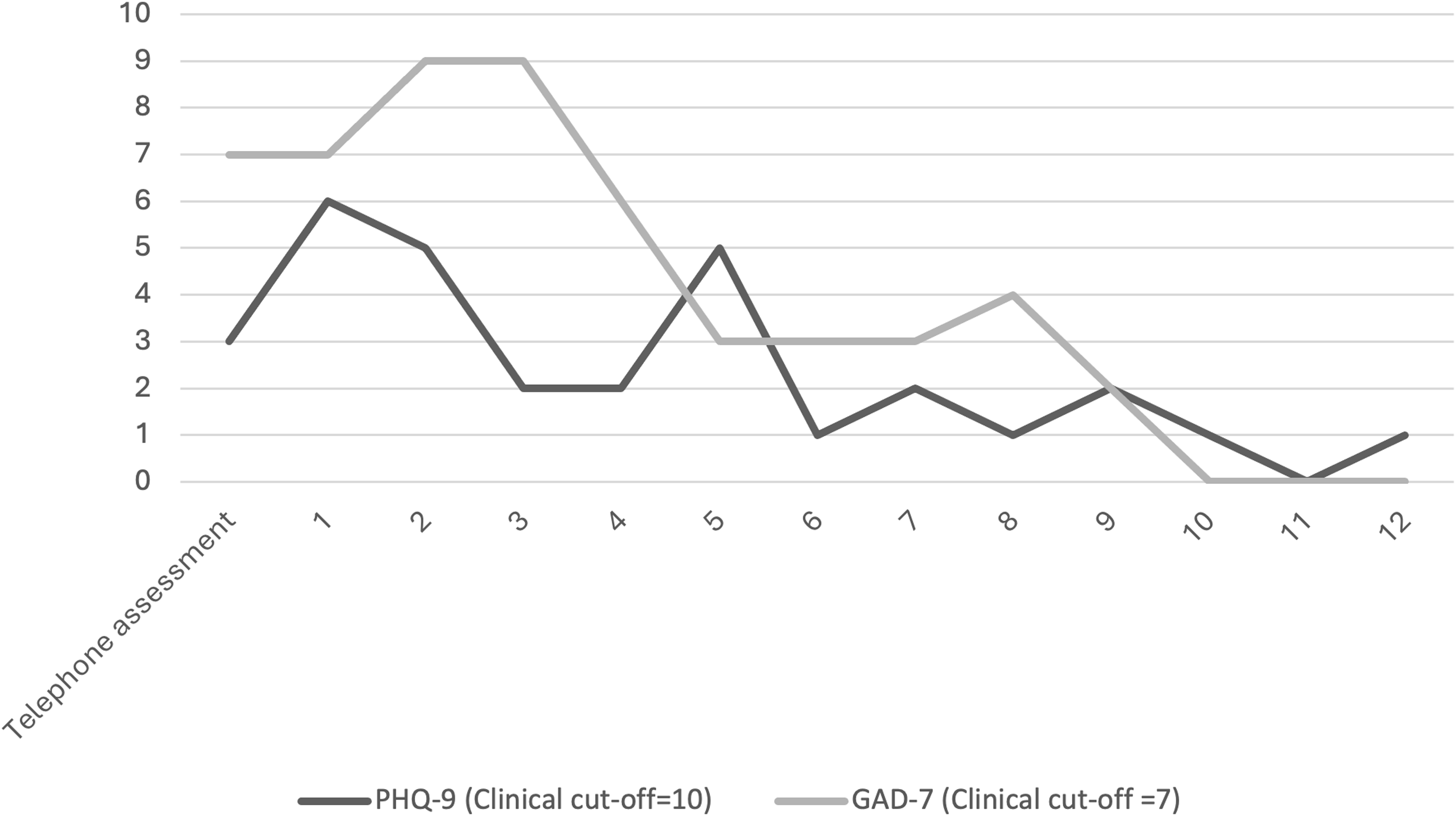

To monitor the effectiveness of the intervention, validated measures of anxiety and depression were completed by the client each week. The Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 Questionnaire (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) assessed levels of anxiety. Clinical caseness is defined as a score of 8 or above (NHS England, 2018). The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) was used to measure mood. Caseness is defined by scores of 10 or above (NHS England, 2018). The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) (Mundt et al., Reference Mundt, Marks, Shear and Greist2002) measures impaired client functioning in different life areas due to mental health difficulties. This measure does not have a caseness threshold but provides valuable information about the quality of a treatment response (NHS England, 2018).

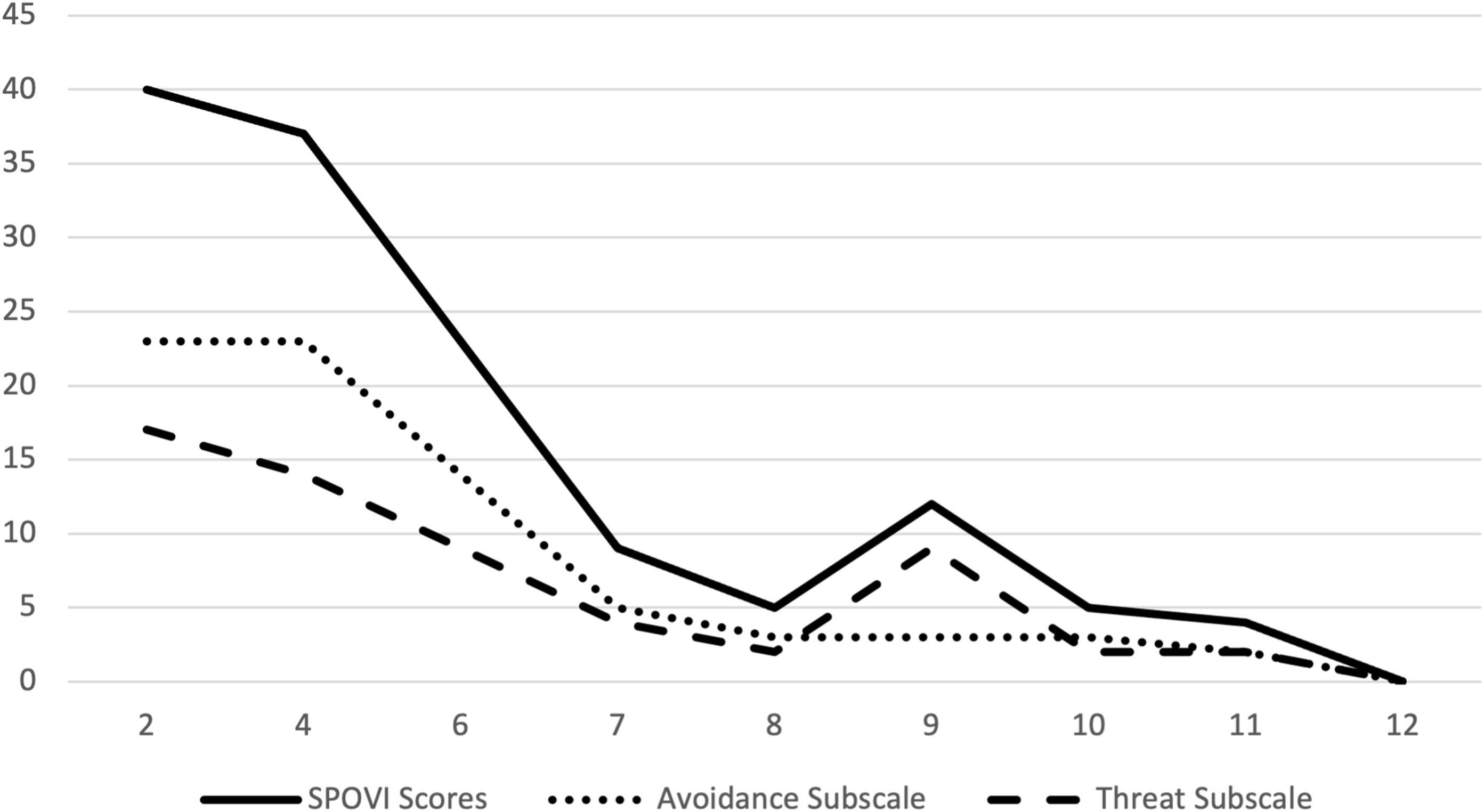

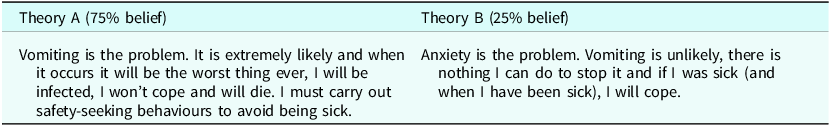

The Specific Vomit Phobia Inventory (SPOVI) (Veale et al., Reference Veale, Ellison, Boschen, Costa, Whelan, Muccio and Henry2013) was used from session 2 onwards, to assess the impact of treatment on specific symptoms of SPOV. The maximum score is 56, and a score of 10 or above indicates significant SPOV. This measure consists of two subscales, avoidance and threat monitoring.

Introduction to the case

Maisie (pseudonym) is a White British female in her mid-twenties. Eight weeks pregnant with her first child, she presented to Talking Therapies (TT) for treatment of a long-standing SPOV. Previous involvement with mental health services had been around gaining a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) several years prior, after struggling with emotional instability, suicidal impulses and self-harm. Maisie now felt this was well controlled with the use of medication, which she was able to continue at a lower dose throughout her pregnancy, and was no longer impacting her day-to-day life.

Maisie’s SPOV was resulting in significant life impairment due to constantly ruminating about vomiting, counting the hours until she felt ‘safe’ after potential infection risks, observing others for signs of illness and avoiding situations associated with vomit. The worst outcome was Maisie herself being sick; the last time this occurred was age 16. Maisie stated, ‘I would rather die than be sick’ due to the loss of control of her body it represented, resulting in thoughts such as ‘I won’t be able to cope, I’ll die’. The focus of her safety behaviours was around monitoring others for signs of nausea or vomiting. This was driven by Maisie’s fear of being infected and becoming ill herself, especially if she did not know the cause of the other person’s vomiting, rather than a fear of witnessing other people vomit. Vomiting on her own was worse than vomiting around others, because of the lack of support available when on her own. To Maisie, children posed the biggest threat due to the infection risk and unpredictability of them being sick. Maisie met all the ICD11 criteria for a specific phobia (World Health Organization, 2022).

Developmentally, Maisie’s SPOV began around age 7 when she recounted a negative experience of another child vomiting at school and had been present consistently ever since. A similar incident happened two years later. As a result of these experiences, Maisie associated vomiting with feelings of being trapped, out of control, as well as with unpredictability and chaos. Maisie could only recall two lifetime instances of herself vomiting. At age six she remembers feeling better afterwards, not being bothered by the vomiting and believed her anxiety had been a 4/10 at the time. At age 16, she believed her anxiety was a 10/10 with the worst part being waiting to be sick, willing herself not to be sick and feeling nauseous. This memory had stuck with Maisie as her most aversive memory of vomiting, intruded whenever she felt anxious and was associated with her beliefs around the awfulness of being sick and her inability to cope. Maisie recounted how her own mother also has SPOV, yet was always able to look after her when she was sick. Maisie had not previously sought therapy for her SPOV due to feeling embarrassed about her phobia. However, becoming pregnant provided her with the motivation to finally seek help.

At the first session, Maisie reported mild anxiety (7, GAD-7) and mild depression (6, PHQ-9). An initial WSAS score of 20 represented the widespread impact that Maisie’s phobia was having across her life. The first time the SPOVI was completed in session 2, Maisie scored 40 out of a possible 56, significantly above the clinical cut-off of 10.

Pregnancy-specific concerns

Now pregnant with her first child, Maisie had decided to seek help. Maisie’s pregnancy had been unplanned; she stated that planned pregnancy was something she would have avoided. Maisie was particularly worried about the risk of vomiting during labour and felt that if this happened that it would result in her having a panic attack and that she would not be able to cope with this. Attending antenatal appointments was also causing Maisie significant anxiety, especially when surrounded by other pregnant women in the waiting area, for fear of witnessing them being sick. Maisie would sit as far away from other women as possible and would be constantly scanning others, looking for signs they might be sick and avoiding anyone with a cardboard bowl. Maisie did not often suffer with pregnancy-related nausea and when she did was able to control this with the use of anti-sickness tablets prescribed by her GP, so did not have any goals related to this.

Her motivation for treatment was a desire to be able to care for her child when they become ill; prior to our work together she felt she would have to leave the house if the child became unwell and let her partner take care of them. Children of school age were a particular stressor for Maisie, due to the risk of them catching and bringing home various sickness bugs. As a result, Maisie currently avoided attending soft plays and children’s parties with children of her friends and family members due to risk of infection. Another motivation for treatment was to be able to take her own child to such places. Maisie therefore wanted to work on her SPOV whilst pregnant, so that it did not restrict her ability to parent as her child became older.

Treatment overview

Veale’s (Reference Veale2009) protocol was used to guide treatment. Treatment consisted of 12 weekly hour-long sessions across 4 months, delivered by a trainee clinical psychologist in a UK Talking Therapies service. Treatment involved psychoeducation, collaboratively mapping out a ‘vicious flower’ maintenance formulation, using an anxiety diary to monitor SPOV anxiety and help Maisie identify her safety-seeking behaviours, introducing Theory A/Theory B, using an exposure hierarchy to set a series of behavioural experiments and imagery rescripting of aversive memories of vomiting. As per the Perinatal Positive Practice Guidelines, flexibility in session time and day was offered to help Maisie fit therapy around other medical appointments (O’Mahen et al., Reference O’Mahen, Healy, Haycock, Igwe, Chilvers and Butterworth2023). In accordance with NICE guidelines on antenatal and postnatal mental health (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014; latest update 2020), Maisie was also fast-tracked into treatment, only waiting 4 weeks between referral and the first session of CBT.

CBT formulation

Veale’s (Reference Veale2009) model of emetophobia was used; this model was a good fit for Maisie’s presentation and difficulties, and there is evidence that this model and accompanying protocol are effective in treating SPOV (Riddle-Walker et al., Reference Riddle-Walker, Veale, Chapman, Ogle, Rosko, Najmi, Walker, Maceachern and Hicks2016). During the assessment sessions, Veale’s (Reference Veale2009) vicious flower was collaboratively mapped out to understand the development and maintenance of Maisie’s SPOV (see Fig. 1). Maisie found this validating, stating how it was like ‘seeing my brain on a piece of paper’ and helped to make sense as to why the phobia had persisted so long. Alongside these sessions, Maisie kept an anxiety diary to capture moments of SPOV anxiety, and to help us gather data on her safety-seeking behaviours, thoughts and physiological symptoms during moments of anxiety, which fed into our formulation.

Figure 1. Maisie’s vicious flower.

Goals

Maisie’s short-term goal was to stop scanning people for signs of illness as she found this so exhausting. Her longer-term goal was to know she could be around her child when they are sick, comfort them and help to clean up the vomit and her child.

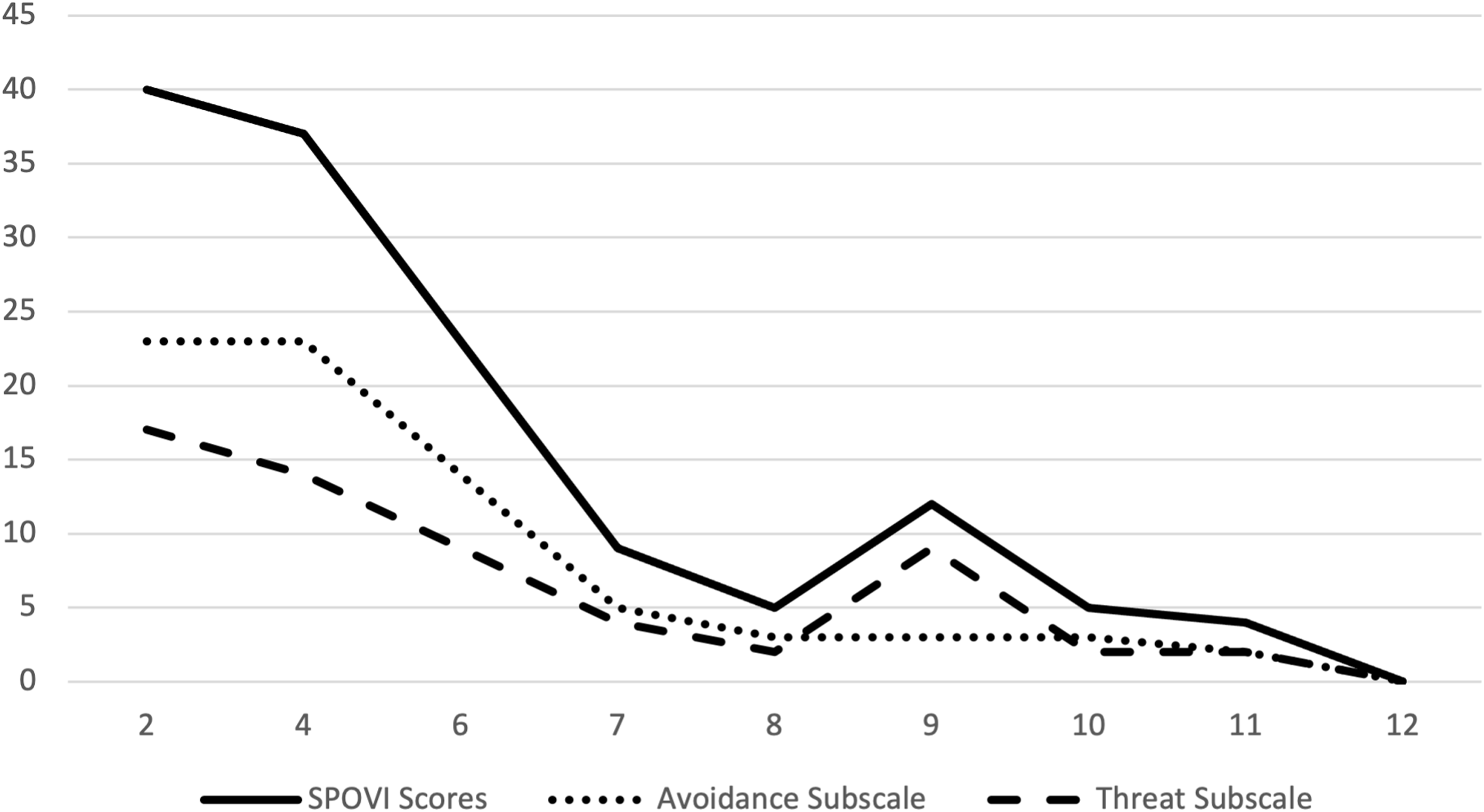

Theory A/Theory B

Early on in therapy, the technique ‘Theory A/Theory B’ was introduced to help Maisie reframe her SPOV as a problem of anxiety and worry, rather than one of vomiting. Socratic questioning and guided discovery were used to help establish Theory A and Theory B (see Table 1).

Table 1. Theory A/Theory B

Exposure and experiments

A hierarchy of avoided situations was mapped out and used as the basis for behavioural experiments both within sessions and as homework. The hierarchy included watching images, videos and sound clips of vomit/people vomiting, gradually building up to exposure to fake sick, touching things in public places, spending time around children and eating avoided foods such as chicken without checking every piece. For every behavioural experiment (BE) set, a BE sheet was filled in before and after. At the start of each session, Maisie was asked for her updated percentage belief in Theory A vs B based on homework tasks, and any learnings from the BE were added as evidence for Theory B.

Reductions across all measures were seen each time an experiment took place. Experiments included: exposure to images of people vomiting (session 5); watching videos of people vomiting (session 6); visiting a supermarket and then other public places (public transport, shopping centres, etc.) whilst dropping safety behaviours of scanning, holding breath, avoiding touching things and washing hands (session 7 onwards); visiting her 5-year-old nephew, sharing his food and playing with his toys whilst dropping safety behaviours (session 8 onwards); interoceptive exposure (session 9), and pretending to be sick with fake vomit (sessions 10 and 11).

A slight increase in the SPOVI threat monitoring scores was seen around session 9. Maisie reported feeling extremely nauseous that week and encountering thoughts about not being able to cope if she was sick. As a result, that weeks’ homework was focused on interoceptive exposure, utilising Maisie’s travel sickness to test her ability to cope with nausea.

Towards the end of therapy, some avoidance around activities that may induce nausea, e.g. pretending to be sick using fake vomit was identified. Maisie said she still couldn’t bring herself to use parmesan in the fake vomit; the smell made her worry that she might be sick. Borrowing the tool of risk calculations commonly used in PTSD treatment, we worked collaboratively to calculate the likelihood of being sick when feeling sick. Maisie reported feeling nauseous roughly once every 3 months yet only being sick twice in her life. Her lifetime chance of being sick when feeling sick was calculated as 1.92%. This statistic acted as a mechanism to support Maisie to approach the final exposure tasks.

Imagery rescripting

When formulating, we identified how the aversive memory of being sick age 16 haunted Maisie whenever she felt sick. In session 11, we used imagery re-scripting as per Veale’s (Reference Veale2009) protocol to update the meanings of this memory. Three hotspots and their subjective units of distress (SUDs) were identified; panic (10/10), anger at herself for ‘causing’ vomiting (9/10) and embarrassment for being sick in front of her mother (7/10). For each hotspot, Maisie wrote updates of what she needed to hear at the time such as ‘this was not your fault, you didn’t know it would make you ill’ and ‘it will be ok, you will feel better soon’ and then read this back every day the next week, which helped to reduce the SUDs for each hotspot. In our final session, she reflected on how helpful this was to reframe this memory by seeing vomiting as temporary and associated with relief.

Blueprinting

Therapy ended by creating a detailed therapy blueprint in which we mapped out experiments that Maisie would continue to engage in, such as going to the supermarket, going to soft play and spending time with her younger cousin, all whilst dropping safety-seeking behaviours. A relapse prevention plan was put together including potential triggers, warning signs to look out for and a list of strategies for coping with these.

Outcome

Maisie’s initial score on the SPOVI was 40/56, representing clinical levels of SPOV. Maisie scored 23/28 on the avoidance subscale and 17/28 on the threat monitoring subscale, reflecting her description of life being dictated by avoidance of vomit-related situations, reducing the likelihood of feeling threatened by vomit due to lack of exposure.

From session 2, PHQ-9, WSAS and SPOVI scores began to fall (see Figs. 2 and 3). Maisie reflected on how helpful and validating she found the vicious flower exercise, and how she found this experience of therapy to be validating and non-judgemental. Combined, this may have begun to give Maisie hope that her phobia was treatable and that she could regain control over it.

Figure 2. SPOVI scores.

Figure 3. PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores.

By the end of treatment at session 12, when Maisie was 6 months pregnant all her scores were below caseness (SPOVI, 0; PHQ-9, 1; GAD-7, 0; and WSAS, 4), representing marked improvement across the board. On the SPOVI, reliable change is reported to be 7 or more points (Veale et al., Reference Veale, Ellison, Boschen, Costa, Whelan, Muccio and Henry2013), so Maisie showed a clinically significant and reliable change over treatment. As Maisie’s initial GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores were not over caseness, she was not able to meet ‘reliable recovery’ as measured by TT services but did show reliable improvement on these measures. She reported significant achievement on both her goals: 10/10 on stopping scanning people, and 9/10 on feeling confident that she can take care of her child when they are ill. Her final belief ratings were Theory A (5%) and Theory B (95%), reflecting her shift in cognitions.

Regarding her pregnancy-related goals, Maisie felt she was able to focus more on herself and less on scanning others when waiting for antenatal appointments, feeling more relaxed than she was ever able to previously in these settings. Regarding being sick during labour, in our final session together Maisie stated that if she was sick during labour she knew that there was nothing she could do about it, that it was temporary and that therefore she felt she would be able to cope with it. Maisie also fed back on her experience of labour after our work together:

‘Ultimately, I ended up having a C-section which causes nausea afterwards, and I did feel like I was going to vomit. I resisted, as is my nature, but also because I hadn’t eaten in 24 hours and it would just make me feel worse. I coped by thinking of the work we did and how even if I am sick, it’s always going to be temporary and over quite quickly, and it’s not the end of the world!’

Discussion

Veale’s (Reference Veale2009) model of SPOV was a good fit for Maisie’s presentation and difficulties, therefore Veale’s CBT protocol for SPOV was used to guide treatment. Overall, this intervention appeared very effective in treating SPOV during pregnancy given the large reductions in SPOVI scores that occurred. Maisie reported dropping almost all her safety behaviours (when feeling nauseous she was still taking anti-sickness medication but waiting an hour before taking these rather than taking them straightaway) and regaining functioning and enjoyment across all areas of her life. Maisie was successful in reaching both her short-term and longer-term goals. In terms of being able to deal with being sick herself, she rated achievement on this as 8/10 but stated that she would not know whether this is the case until this happens. This was the reason that she maintained a 5% belief rating in Theory A, worrying that when she is sick, she might have a panic attack and embarrass herself.

Although no formal follow-up measures were collected, in an informal post-discharge follow-up, Maisie highlighted that the positive effects of treatment persisted beyond pregnancy and into early parenthood; she was even able to cope with her baby being sick with minimal anxiety. However, Maisie also reported that some of her emetophobia had later returned alongside some more generalised health anxiety once she had returned to work and her child started attending nursery. Ideally, clients seen in pregnancy would be offered follow-up sessions when they move into the postpartum period to help reinforce therapy learnings and address issues pertinent to this new life stage. A detailed blueprint at the end of therapy should also include specific experiments for the postpartum period and forward thinking through the possible challenges of the first year as the child develops. Whilst aligning with the flexibility in therapy delivery recommended by the Perinatal Positive Practice Guidelines (O’Mahen et al., Reference O’Mahen, Healy, Haycock, Igwe, Chilvers and Butterworth2023), offering follow-up sessions so long after discharge could be difficult in very structured services such as Talking Therapies, as it would involve keeping clients open to the service for several months post-discharge.

Formulation itself using the vicious flower appeared to help Maisie understand the role of her safety-seeking behaviours in maintaining her phobia. This, combined with using an anxiety diary to capture moments of SPOV anxiety and help Maisie become more aware of previously automatic behaviours appeared to increase Maisie’s motivation to challenge these behaviours and to ‘regain control’ of her life, and helped normalise her symptoms.

Behavioural experiments were effective in challenging Theory A appraisals (vomiting is the problem) and building up evidence for Theory B (anxiety is the problem). As Maisie’s phobia was focused on contamination, experiments using videos or photos of other people being sick appeared less effective at raising anxiety levels, with anxiety only reaching a peak of 5/10. Real-world experiments, e.g. in a local supermarket and on public transport, in which Maisie was exposed to avoided stimuli (children, germs, crowds of people) whilst dropping all safety behaviours resulted in the greatest amount of evidence for Theory B (e.g. ‘safety behaviours only reinforce my phobia’/’being normal around strangers won’t make me ill’) and Maisie commented on finding these helpful in unlearning years’ worth of safety behaviours. As repetition and use of different contexts in exposure is crucial to aid generalisation of learning (Craske, Reference Craske2015), it perhaps would have been helpful to conduct more experiments in locations where Maisie would likely go with her child such as soft plays and playgrounds both within and between sessions.

Towards the end of therapy, it appeared certain threat-monitoring behaviours were still present during episodes of nausea, resulting in avoidance on certain experiments (pretending to be sick with fake vomit) for fear of being sick. Imagery rescripting of Maisie’s aversive memory appeared to effectively reduce these threat-monitoring behaviours, and to help Maisie learn that although vomiting is unpleasant, that (a) she can cope with it and (b) it is often associated with relief and feeling better. As the rescripting was helpful in loosening Maisie’s beliefs around the awfulness of vomiting and her ability to cope, it might have been helpful to bring it in earlier in treatment, prior to exposure work to help Maisie’s willingness to approach behavioural experiments, although she was able to begin exposure prior to this.

Another technique used to support approach to exposure was the use of a risk calculation in terms of the likelihood of vomiting when feeling nauseous. This was a slight deviation from protocol but appeared impactful in helping Maisie to approach the final exposure tasks by seeing how unlikely she was to be sick, even when nauseous. Whilst such a technique proved helpful in allowing Maisie to engage in exposure, care must be taken that such a statement does not form a reassurance function for the client and become another safety-seeking behaviour when nauseous.

Regarding Maisie’s BPD, during assessment we had explored potential ways this might impact our work together. However, due to the treatment setting of a TT service, a full structured diagnostic interview around the BPD was not completed. Maisie felt it was unlikely to impact our sessions but might mean that she was more likely to go away and ruminate over something discussed. We made sure to always end our sessions with space for a check-in and feedback, which helped make sure Maisie was feeling okay before leaving each session. Overall, her BPD did not appear to have an impact on the treatment delivered, nor her ability to tolerate the anxiety associated with exposure.

Perinatal considerations

Maisie was 8-weeks pregnant when we first met and struggled with infrequent, mild episodes of pregnancy-related nausea during her first trimester. We made use of naturally occurring anxiety-inducing situations for Maisie in our work together. For example, in our early work together Maisie had encountered severe anxiety whilst in the waiting room for her antenatal appointments, worrying about other pregnant women vomiting. We used this situation to help map out the vicious flower and better understand her current coping strategies and safety-seeking behaviours. Future antenatal appointments presented Maisie with a chance to test out alternative coping strategies whilst dropping her safety-seeking behaviours and to notice the difference on her anxiety levels. Recalling recent episodes of pregnancy-related nausea also proved helpful to better understand the bottom line of Maisie’s anxiety around being sick herself – ‘I won’t cope, and I will die’, and to identify modifiers of her SPOV, e.g. being sick on my own is worse than being sick around other people. Maisie was able to use future episodes of nausea to test alternative strategies such as shifting her attention externally and breathing exercises, and compare these with previous, less helpful strategies that acted to maintain the nausea.

Throughout our work together, we did not use any techniques that would put strain on Maisie physically, contradict government guidelines for pregnant women or risk serious illness, e.g. eating food past its sell-by date, eating chicken not cooked thoroughly or drinking alcohol (even though this was avoided for fear of being sick). Despite the lack of belief about being able to cope with vomiting, induced vomiting was not carried out. There is a lack of evidence for the effectiveness of using this as a technique as well as ethical and health issues around the repeated induced vomiting that would be required to increase tolerance (Riddle-Walker et al., Reference Riddle-Walker, Veale, Chapman, Ogle, Rosko, Najmi, Walker, Maceachern and Hicks2016).

However, in general, a standard but individually tailored treatment approach was adopted. The risk of not intervening to treat Maisie’s SPOV was a continuation of living in a state of severe anxiety around vomiting. Some studies have shown that severe, sustained anxiety is associated with increased likelihood of negative effects on maternal wellbeing, the pregnancy and the developing foetus, the birth experience, and the developing infant’s temperament (Fairbrother et al., Reference Fairbrother, Challacombe, Green and O’Mahen2025). However, it is important to note that none of these studies have investigated the impact of untreated SPOV specifically. The impact of continued anxiety on Maisie’s wellbeing was high, and she was keen to engage with treatment prior to starting a new phase of life. Therefore, for Maisie, the potential benefit of treatment outweighed any risks of not going ahead and the possible, although objectively low, risks of treatment. Such risks included potential illness from e.g. not washing her hands when visiting a supermarket or taking public transport, the risk of inducing actual vomiting due to the use of fake vomit and the risk of catching a sickness bug from other people or children that she was purposefully exposing herself to. If a ‘better safe than sorry’ approach had been adopted too harshly, learnings for this client may not have been as great, nor treatment as effective.

Maisie was asked to reflect on her experience of CBT during pregnancy, and whether she would recommend this approach to other pregnant women:

‘I found the CBT incredibly helpful. The amount and length of the sessions, taking it slowly, putting what I’d learnt in place e.g. going to Aldi and touching the baskets, etc., was so helpful. Exposure to things like photos and videos, although unpleasant, absolutely helped. Seeing my progress across the weeks with the questionnaire was like a miracle! Scoring so high on the initial quiz and then it being close to zero towards the end was mind blowing. I would absolutely recommend CBT for emetophobia for pregnant women to prepare themselves for the journey ahead. It has turned my life around and I’m able to enjoy my son instead of worrying constantly about if he’s going to be sick.’

Limitations

The GAD-7 and PHQ-9 were completed online as self-report measures, whereas the SPOVI was completed together in-session, and it was clear that the aim of our work was to reduce scores over time. This therefore may have been subject to social desirability bias, with Maisie possibly under-estimating her scores to reflect a ‘model client’. However, the increase in scores at session 9 potentially demonstrates that this was not entirely the case. Furthermore, the SPOVI was not collected at every session, and therefore whilst it appears there was a week-on-week decrease in scores, there may have been undocumented increases.

Whilst only one formulation diagram was created, in retrospect it may have been helpful to complete two or three formulations for different levels of threat, as the safety and checking behaviours that Maisie used differed depending on the situation.

It is important to note that this was a single case study; single case experimental designs (SCED) are better able to establish the effectiveness of an intervention; however, it was not possible to collect data ahead of treatment to establish a clear baseline. Future research should aim to extend this research and test the effectiveness of CBT treatment for SPOV during pregnancy using a case series or SCED format.

Conclusion

This case report provides further evidence for the effectiveness of adopting a treatment as usual approach in following Veale’s (Reference Veale2009) protocol and in using exposure-based therapy for SPOV when working with pregnant clients.

Key practice points

-

(1) Pregnancy involves physical changes and sensitivities including nausea and vomiting, which can result in heightened anxiety for women with SPOV. Sustained anxiety during the perinatal period can result in numerous negative outcomes for both the mother and her developing foetus (Fairbrother et al., Reference Fairbrother, Challacombe, Green and O’Mahen2025). It is therefore important to adopt a standard but individually tailored treatment approach; the risk of not treating severe anxiety greatly outweighs the objectively small risks of exposure treatment during pregnancy.

-

(2) Treatment of SPOV during pregnancy begins by jointly mapping out a vicious flower formulation to explain how current thinking patterns and safety-seeking behaviours act to maintain the SPOV. Conducting sessions in the ‘real world’ can be helpful to identify subtle and possibly previously undisclosed safety-seeking behaviours.

-

(3) The aim of treatment is to reframe the problem from one of vomiting (Theory A) to one of anxiety and worry (Theory B), using behavioural experiments of exposure to both avoided external and internal stimuli to build evidence for Theory B. Leaving the clinic to carry out real-world experiments was especially effective in challenging Theory A as well as instilling confidence to practise experiments between sessions.

-

(4) Imagery rescripting of aversive memories associated with vomiting is helpful to address strong negative beliefs around vomiting including ‘I won’t cope’ and ‘I would rather die than vomit’ and to help update strong negative emotions, e.g. panic and embarrassment associated with such memories.

-

(5) Regular use of disorder-specific measures such as the SPOVI (Veale et al., Reference Veale, Ellison, Boschen, Costa, Whelan, Muccio and Henry2013) is helpful to track treatment progress.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, J.A., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Jessica Allinson: Conceptualization (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (lead); Marion Barnbrook: Conceptualization (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Resources (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Fiona Challacombe: Project administration (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

J.A. was supported by funding for professional clinical psychology training by Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. No ethical approval was required for this case study; the treatment ran as part of routine clinical cases within an NHS Talking Therapies Service in the UK. All names and identifying details have been changed to preserve confidentiality, consent to publish this manuscript has been obtained from the client involved and they have seen this submission in full and agreed to publication.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.