Introduction

In an increasingly turbulent and insecure world following climate change, terrorism, hybrid warfare, and a host of other mounting threats to society, local communities across the globe are currently bolstering their emergency response capacity (Krogh & Lo, Reference Krogh and Lo2023a). Even in highly developed welfare states, emergency response frequently requires resources beyond those available to public authorities. Co-production, defined as “a joint effort of citizens and public sector professionals in the initiation, planning, design and implementation of public services” (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Verschuere and Steen2018), is therefore often necessary to enhance the problem-solving capacity of emergency management organizations and local communities (Brudney & Gazley, Reference Brudney and Gazley2009; MacManus & Caruson, Reference MacManus and Caruson2011; Simo & Bies, Reference Simo and Bies2007; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Shang and Collins2015). At the same time, citizen engagement in emergency preparation, mitigation and response empowers citizens by granting them an opportunity to act on matters of importance to themselves, their families, and their communities during crises (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen2022).

Keenly focused on risk management, however, public incident commanders from formal emergency organizations often choose to dismiss citizens from the scene of incident instead of co-producing emergency response with them, since any uncoordinated, thoughtless or misguided behaviour of untrained and unequipped citizens may endanger the lives of those involved and result in confusion, accidents, and further escalation of the emergency situation (Krogh & Lo, Reference Krogh and Lo2023b; Sauer et al., 2014; Barsky et al., 2007; Harris et al., 2016; Skar et al., Reference Skar, Sydnes and Sydnes2016). Yet, in some instances, non-profit organizations (NPOs) such as the Red Cross step in to provide support, direction and guidance for engaged citizens, for instance by establishing temporary one-stop shops for informing and advising on the evolving situation, where to go, and what to do (Brudney & Gazley, Reference Brudney and Gazley2009; Nissen et al., Reference Nissen, Carlton, Wong and Johnson2021; Paciarotti et al., Reference Paciarotti, Cesaroni and Bevilacqua2018; Skar et al., Reference Skar, Sydnes and Sydnes2016). Acting as intermediaries, defined as ‘nongovernmental actors who have professional knowledge and participate in public service delivery’ (Haug, Reference Haug2023, p. 3), they thereby absorb some of the risk of citizen engagement in emergency response, which can make a decisive difference for the dispositions of incident commanders. In this article, we will develop and use the concept of ‘intermediated co-production’ to capture processes by which NPOs facilitate the joint emergency response of citizens and public sector professionals.

Despite an emerging international literature of case studies describing the contribution of citizens in co-produced disaster and emergency response (Kapucu, Reference Kapucu2006; Simo et al., 2007; Eller et al., Reference Eller, Gerber and Branch2015), little is known about the role of NPOs in emergency management co-production. The co-production literature points to mutual trust as the key coordinating mechanism in the co-production of public services (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Verschuere and Steen2018; Pestoff et al., Reference Pestoff, Brandsen and Verschuere2012; Verschuere et al., Reference Verschuere, Brandsen and Pestoff2012; Voorberg et al., Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers2015), and institutional trust research shows the importance of renown and reliable organizations in generating and sustaining trust (Oomsels & Bouckaert, Reference Oomsels and Bouckaert2014, p. 591). Therefore, we have reasons to expect that NPOs play a role as trust-supporting infrastructures in emergency management co-production. Yet, the few exiting studies of the role of NPOs in the co-production of emergency response (see for example Skar et al., Reference Skar, Sydnes and Sydnes2016; Paciarotti et al., Reference Paciarotti, Cesaroni and Bevilacqua2018; Nissen et al., Reference Nissen, Carlton, Wong and Johnson2021) do not examine their influence on trust in processes of emergency management co-production.

In order to provide new knowledge for scholars, practitioners and policymakers concerned with co-production, this article examines how NPOs serve as intermediaries that build trust in engaged citizens and thus facilitate the co-production of emergency response. Reporting on a qualitative study of emergency management co-production in Denmark and Norway, it shows how NPOs enhance trust in citizens through structures, procedures, and practices for registering, leading and commanding engaged citizens, thus enabling emergency management co-production. Eliciting the role of NPOs as trust-building intermediaries, the study contributes with new knowledge for scholars, practitioners and policymakers involved in issues of co-production within and beyond the field of emergency management.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we build on theories and research on co-production, emergency management and trust to develop a theoretical understanding of the intermediary role of NPOs as trust-builders in the co-production of emergency response. Second, we explain the methods applied in our empirical study. Third, we report on the study findings, showing how various structures, procedures and practices of NPOs affect the trust assessments of incident commanders involved in emergency management co-production. Fourth, we discuss how the findings provide new insights to co-production research and contemplate their implications for practice. Fifth, we conclude by briefly reiterating our research interest, stating our main findings, and reflecting on the need for further research.

The Trust-Building Role of NPOs in Emergency Management Co-production

Emergency management co-production is no new kid on the block. In a piece often credited for coining the co-production term in a public service setting, Vincent and Elinor Ostrom (1977, p. 20) observe that ‘[t]he efforts of citizens to prevent fires and to provide early warning services when fires do break out are essential factors in the supply of fire protection services. […] Collaboration between those who supply a service and those who use a service is essential if most public services are to yield the desired results’. Building on this early understanding, we define emergency management co-production as a form of public service co-production, where public sector professionals and citizens collaborate to produce operational emergency response to wildfires, flooding, avalanches, house fires, large traffic accidents, or other critical incidents that endanger human lives, natural habitats, and/or valued property. The public sector professionals involved will typically be police officers, fire fighters, and/or medics, while the citizens can be those directly affected by an emergency, but could also be a relative, a neighbour, a bystander, or a citizen arriving to scene with the intent of helping out. The criteria is simply that the person is acting as a citizen outside any organization, and thus not as a professional nor an organized volunteer, in the situation (cf. Brandsen & Honingh, Reference Brandsen and Honingh2015, p. 428–430). Focusing on citizens, our definition corresponds with more narrow understandings of co-production that exclude interorganizational collaboration (which co-management and co-governance perspectives on co-production often include, cf. Brandsen & Pestoff, Reference Brandsen and Pestoff2006). As we argue with the concept of intermediated co-production, however, organizations can play a role as mediators of the relationship between public sector professionals and citizens in the collaborative production of public services. Focusing on the direct production of emergency response, our guiding concept also sets apart from notions of co-creation concerned with the design of new and innovative solutions (Torfing et al., Reference Torfing, Ansell and Sørensen2024) and the wider creation of public value (Osborne, 2018).

Akin to the role of command in hierarchies and competition in markets, trust is considered the main coordination mechanism in networked collaboration (Rhodes, Reference Rhodes1997; Sørensen & Torfing, Reference Sørensen and Torfing2009). Concordantly, research has shown that high levels of trust reduces transaction costs, stimulates learning, and accelerates the exchange of information (Klijn et al., Reference Klijn, Edelenbos and Steijn2010), thus contributing towards positive outcomes of co-production (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Verschuere and Steen2018; Pestoff et al., Reference Pestoff, Brandsen and Verschuere2012; Verschuere et al., Reference Verschuere, Brandsen and Pestoff2012; Voorberg et al., Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers2015). In the context of emergency management, research has found that ‘trust is crucial in the uncertain situations caused by an extreme event’ (Kapucu, Reference Kapucu2006, p. 209) and shown the importance of trust for the performance, sustainability, and outcomes of emergency management networks (Cainzos, Reference Cainzos2021; Kapucu et al., Reference Kapucu, Garayev and Wang2013). Conversely, studies examining unsuccessful cases of emergency response have found that inter-organizational and interpersonal distrust is among the most debilitating communication barriers during crisis, leading to a fragmented response (Moynihan, Reference Moynihan2009, p. 107).

Trust is commonly defined as ‘the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party’ (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995, p. 712). More specifically, trust is the willingness to run a calculated risk based on a more or less conscious assessment of the trustee’s domain-specific competence, benevolence and integrity as someone who adheres to an acceptable set of principles (ibid., pp. 718–719). Evaluating the trustee positively on those parameters, the trustor will carry positive expectations that the trustee will fulfil their obligations, behave predictably, and act fairly, increasing their willingness to trust them (Zaheer et al., Reference Zaheer, McEvily and Perrone1998, p. 143). Applied to emergency management co-production, this proposition leads us to expect that the willingness of public incident commanders to engage in co-production relies on the incident commander’s assessment of the citizens’: (a) domain-specific competence, i.e. their capabilities needed for solving a specific emergency response task, (b) benevolence, i.e. their benign motivations for taking part in the emergency response, and (c) integrity, i.e. their expected adherence to the principles, rules and norms of emergency management.

Much research on the role of trust in public service co-production and collaborative disaster response has focused on interpersonal trust and considered trust a function of a personal attitude towards others, relating it to dispositional qualities such as loyalty, altruism, and honesty (Aldrich, Reference Aldrich2016; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995; Moynihan, Reference Moynihan2009). In later years, however, the literature has examined how institutional trust develops between members of different organizations by virtue of them belonging to those organizations (see for example Oomsels & Bouckaert, Reference Oomsels and Bouckaert2014; Lo et al., Reference Lo, Breimo and Turba2022; Krogh & Lo, Reference Krogh and Lo2023a). It has found that the external legitimacy and perception of an organization affects the trust placed in its members as others regard them as carriers of the organizational values, norms, and capabilities (Bachmann & Inkpen, Reference Bachmann and Inkpen2011; Sønderskov & Dinesen, Reference Sønderskov and Dinesen2016). Consequently, organizations can increase the external trustworthiness of their members through a range of institutional practices that enhance and consolidate the (perceived) competence, benevolence and integrity of the organization and – by extension – its members. These practices include procedures and practises for vetting, socializing and educating their members, identifying and sanctioning inappropriate behaviour in correspondence with the organizational norms and professional ethos of the given community of practice (Fuglsang & Jagd, Reference Fuglsang and Jagd2015) as well as external boundary work that improves the organizational reputation and affects schemes of social categorization (Kroeger et al., Reference Kroeger, Racko and Burchell2021; Simo & Bies, Reference Simo and Bies2007). When NPOs perform such practices, they increasing the willingness of external actors to run a calculated risk of involving and collaborating with their affiliated volunteers as they raise external expectations of their domain-specific capabilities of performing particular actions without being closely monitored or controlled. NPOs thus enhance institutional trust in their members by vouching for their competences, benevolence and integrity.

While, organized volunteers and other certified members of established NPOs enjoy the institutional trust stemming from their membership, unaffiliated citizens who spontaneously engage in co-production do not have the same institutional backing. Incident commanders (ICs) must therefore assess the trustworthiness of each individual before running the risk of allowing them to perform a task during an emergency response operation. Since, time is often scarce, the usual trust-cooperation spiral that gradually builds trust as positive experiences of cooperation accumulate (Ansell & Gash, Reference Ansell and Gash2008) is dismantled. By the same token, ICs are often unable to make proper individual trust assessments and therefore choose to use their authority to dismiss citizens from the scene instead of engaging in co-production with them (Krogh & Lo, Reference Krogh and Lo2023b).

When NPOs step in to temporarily organize citizens during emergency response operation, they act as intermediaries mediating the relationship between public service providers (the incident commanders) and service users (the citizens) in the co-production process (cf. Haug, Reference Haug2023). From a perspective of institutional trust theory, the NPOs may find ways to transfer some trust to the involved citizens. Unable to perform systematic vetting, education, and long-term socialization, however, the NPOs face much more challenging conditions for procuring institutional trust in citizens than in their organized volunteers.

Methods

To examine how NPOs build trust in citizens during emergency response, we draw on data collected for the Nordic research project Voluntary Organizations in Local Emergency Management (VOLEM) that examines the role of NPOs in Danish and Norwegian emergency management. Denmark and Norway both exhibit high levels of social trust and strong state-society relations. Moreover, they both rely significantly on citizens and volunteers when managing small and large-scale emergencies in land-based operations, but differ in their specific institutionalization of the role of NPOs in emergency response (Krogh & Røiseland, Reference Krogh and Røiseland2024). We can therefore expect a significant prevalence of emergency management co-production, but a multiplicity of specific manifestations of the phenomenon under study. Our analysis examines the various manifestations appearing across locales, thus taking advantage of the empirical variations produced by our multi-sited research strategy (Marcus, Reference Marcus1995).

Empirical Context: The Danish and Norwegian Emergency Management Systems

The command structure of the emergency management systems in Norway and Denmark resembles that of the Incident Command System in the US (cf. Moynihan, Reference Moynihan2009). At the scene of incident, the police act as chief incident commander (IC) in charge of establishing a shared incident command post that include ICs from the fire and rescue services and health authorities. According to official rules and guidelines, the ICs must coordinate and continuously assess the necessity and desirability of involving additional resources of citizens and voluntary organizations in the emergency response (Aasland & Braut, Reference Aasland and Braut2023; Danish Emergency Management Agency, 2018).

In Denmark, the Danish Emergency Management Agency, the municipal fire brigades, the home guard, and other public authorities organize and deploy volunteers as an integrated part of their services. NPOs such as Missing People – a national-wide search and rescue association organizing voluntary searches for missing persons – also play a role in specific instances. However, the role of larger NGOs like the Danish Red Cross is fairly limited when it comes to emergency response operations.

In Norway, public authorities do not organize volunteers as part of their services, but often collaborate with specialized NPOs, especially those associated with the umbrella organization Forum for the Voluntary Rescue Service Organizations (FORF), which includes the Norwegian Rescue Dogs, the Norwegian People´s Aid, the Norwegian Radio Relay League, and the Norwegian Red Cross (Gjerde & Winsvold, Reference Gjerde and Winsvold2017). In addition, some other organizations such as the highly specialized Alpine Rescue Groups are considered part of the emergency management community despite not being formal members of FORF. In the local management of emergencies in both countries, the ICs also engage in co-production with spontaneous volunteers with no organizational affiliation, although our data suggest that such instances are more common in Denmark than in Norway.

Data Collection

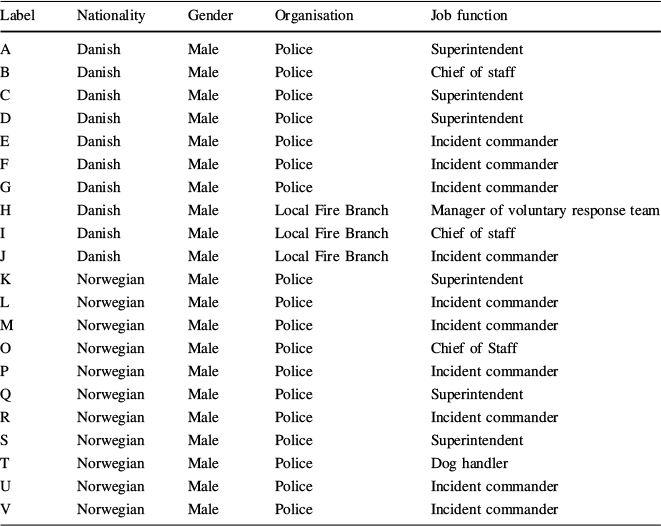

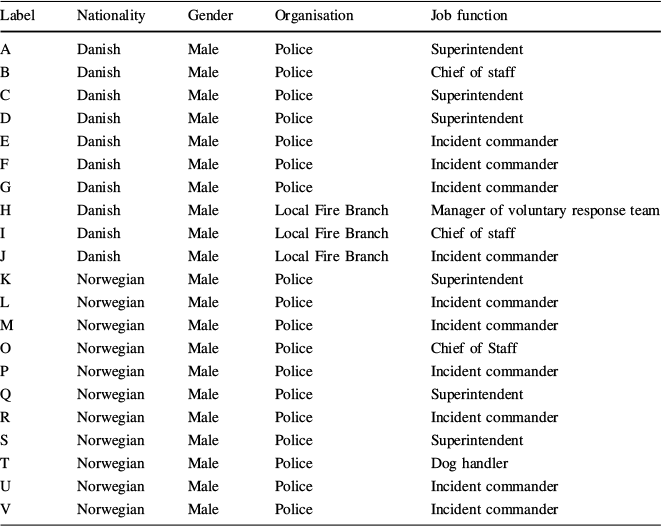

We base our analysis on qualitative interviews with Danish and Norwegian incident commanders (ICs) with extensive experience of co-producing emergency response. Between late-2020 and early-2022, we conducted 21 semi-structured interviews with ICs – ten in Denmark and eleven in Norway (see Table 1 in the Appendix for an overview of respondents). We selected interviewees with the aim of achieving a rich set of empirical data through a broad spectrum of experiences with the phenomena under investigation (Maykut & Morehouse, Reference Maykut and Morehouse1994). Accordingly, interviewees were selected based on their extensive experience as ICs responsible for coordinating citizens and volunteer resources in land-based emergency management operations. The types of incidents discussed in the interviews therefore range from minor incidents such as house fires and traffic accidents to larger search and rescue operations relating to missing persons, major accidents, and natural disasters.

In Denmark, we interviewed seven police officers and three firefighters within the same police district covering both urban and rural areas. In Norway, we interviewed police officers from three different police districts, covering both urban and rural areas, but located in different parts of the geographically dispersed country. A flexible and thematic interview guide framed the research interviews with the main purpose of making the ICs recollect and reflect upon their interactions with citizens and NPOs during past incidents as well as their inclination to co-produce emergency response with citizens during future emergencies. All interviews were recorded and averaged about one hour.

Data Analysis

Our interpretive analysis exploits the variation in our data concerning different forms of co-production with citizens and cooperation with NPOs. Specifically, our study aims at exploring the role of NPOs in sustaining and developing trust in citizens before, during and after emergency management operations. While, our research question focuses on trust-building in intermediated co-production, where NPOs temporarily organize citizens, our analysis also focuses on trust in unaffiliated citizens in situations where no intermediaries are present (what we call ‘spontaneous co-production’) and in organized volunteers who act as members of a trusted NPO, since spontaneous co-production and cooperation with organized volunteers provide analytical counter-cases that show a) how the presence of NPOs affects the ICs’ trust in citizens (compared to spontaneous co-production) and (b) how the unaffiliated/non-membership status of citizens affects the ICs’ trust in them (compared to the cooperation with organized volunteers).

Conducting a thematic analysis of the empirical data material as a whole (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), we therefore first coded the data for all three forms of collaborative emergency management. From our theoretical understanding of trust as the willingness to run a calculated risk based on a more or less conscious assessment of the trustworthiness of the trustee (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995, pp. 718–719), we then identified recurring themes in how ICs described and rationalized their decisions to engage, or disengage, in the three types of collaborative emergency management. Analysing the ICs’ trust assessments of (a) unaffiliated and unorganized citizens, (b) temporarily organized citizens, and (c) organized volunteers, we paid particular attention to the ways in which the ICs described and assessed the risks associated with the different types of co-production, their perceptions of the domain-specific competence, benevolence and integrity of the three types of trustees as well as the contextual conditions in which the ICs decide to accept or reject vulnerability. Comparing the trust assessments across the analytical categories, we identified patterned variation in the data concerning the association between forms of collaborative emergency response and levels of trust. As detailed in our presentation of the findings, we base our assessment of trust levels on an interpretation of how the interviewed incident commanders assess the benevolence, competences, and integrity of the different groups of citizens and volunteers, and specifically how such assessments affect their willingness to accept vulnerability and run a calculated risk of involving and collaborating with them (cf. our definition of trust). Our data showed strong consensus on trust levels within each category, but variation between categories, suggesting high construct validity. Analysing the practices associated with trust assessment in each category, we selected particularly illustrative interview quotes for each form of emergency management and translated them into English to ensure sufficient citing of the case study data in the reporting of results (cf. Yin, Reference Yin2018).

Findings

Comparing our findings between the categories of spontaneous co-production and intermediated co-production, we find higher levels of trust in the latter than in the former, suggesting that NPOs contribute toward higher levels of trust between incident commanders and engaged citizens in the co-production of emergency response. Comparing our findings between the categories of intermediated co-production and cooperation with organized volunteers, however, we find lower levels of trust in the former than in the latter, suggesting that the unaffiliated/non-membership status of citizens in co-production puts a cap on the IC’s trust in them. The following subsections detail the findings pertaining to each of the three forms of collaborative emergency management before discussing the findings in sum.

Spontaneous Co-production

Using different words and phrasings, the interviewees all express the sentiment that engaging with citizens and volunteers during emergency response operations “…requires that we believe and trust that they are capable of solving the task that they are given” (IC from the Danish police). However, the ICs express reluctance to entrust unfamiliar volunteers with critical tasks when there are no available means for vetting the competences, or even identities, of the volunteers. As a Norwegian IC puts it:

I haven't experienced [spontaneous volunteerism] in search operations, but I have experienced it in other cases where people just show up and say, "I'm a security guard, I can help you with this and that," or "I can do this and that." But in those situations, they are often rejected because in acute and time-critical situations, there's no time to start checking people. (Respondent V)

Although ICs seldom doubt the benevolence of spontaneous volunteers, statements like the one quoted above suggest that ICs are less likely to trust citizens unvetted by a trusted NPO, especially when limited time and resources constrain their own ability to perform background checks. The expectation that untrained citizens are unaccustomed to the standards, norms and routines of emergency management is another related and recurring theme in the interviews. Requiring careful control and management, spontaneous co-production with untrained citizens was seen as a resource demanding and potentially counterproductive strategy. A Danish IC expressed this sentiment:

Untrained personnel or spontaneous volunteers require more management because they are not accustomed to the job. If you say “take four straps and then we take a 100 metre inner liner again”, then they have no idea what I am talking about. … It comes down to an assessment of when it is helping us speed things up and when it is actually slowing us down. (Respondent H)

Accordingly, the limited trust in the capabilities of untrained citizens made the ICs prone to restrict the scope of spontaneous co-production to relatively simple tasks. In some cases, they are even inclined to distrust and outright dismiss citizens due to their expected lack of an (understanding of) organized leadership structure. Since, ICs cannot expect untrained citizens to have leadership discipline – or what an IC calls the “appreciation of the leadership structure” – they are generally wary to involve citizens in core emergency management tasks and often choose to dismiss citizens from the scene.

Finally, the ICs do not expect citizens to know the concepts and codes for appropriate behaviour due to a lack of socialization into the norms of operating in emergency situations. The ICs from the Danish police apply the concept of “crime scene discipline’ to denote the need for regulating access and behaviour at the scene: “If we decide that we need crime scene discipline, well, then we throw out everyone who doesn’t have any business to do there. They are thrown out because that’s the way it must be managed. There will be volunteers with no business to do there.” The ICs generally express low expectations that citizens know how to behave appropriately in emergency situations, which they consider pivotal for granting and sustaining their access to participate in the emergency response operation.

In sum, the interviewed ICs expressed a reluctance to engage in spontaneous co-production and concerns about entrusting unaffiliated citizens with tasks, since hazardous and misguided behaviour could endanger themselves or the operation. Partly rooted in a negative assessment of their competences and capabilities, as well as a deep-seated assumption that untrained citizens lack the necessary familiarity with command structures and behavioural norms in emergency situations, this rejection of vulnerability is an expression of a low level of trust. Even if the engaged citizens were to have the required knowledge and capabilities, the difficulties of verifying these competences, or even the identity of the citizen in question, during time-critical operations discourage the ICs to engage in spontaneous co-production. The absence of NPOs vouching for citizens and their capabilities thereby limits the spontaneous co-production of emergency response.

Cooperation with Organized Volunteers

While, the Danish ICs had either limited or no experiences with cooperating with members of NPOs, the Norwegian ICs all had extensive experience with this form of collaborative emergency management. Expressing extensive willingness to involve and cooperate with organized volunteers on a variety of challenging tasks and either directly or more subtly tying positive evaluation of trustworthiness to organizational affiliation, the Norwegian ICs exhibit a high level of trust in organized volunteers, especially those affiliated with the NPOs belonging to umbrella organization Forum for the Voluntary Rescue Service Organizations (FORF) as well as some other specialized emergency NPOs with which the ICs were well acquainted. In the interviews, affiliation to a well-known and trusted volunteer organization appeared as a verification of competence and abilities. As one IC puts it:

Of course there can be occasional minor slip-ups here and there. Just like one can say that there are some shortcomings in the police, some police officers who should never have gotten in. It's probably the same in those organizations as well. But I trust every single crew member who comes in. If they come in with the Red Cross jacket, Norwegian People's Aid jacket, or whatever it may be, and sign up, I trust that they can do their job, absolutely. (Respondent M)

The Norwegian ICs expressed particular confidence in the FORF organizations’ vetting procedures and volunteer training programs for ensuring high levels of reliability and capabilities of their volunteers, underpinning the ICs’ general trust in them. As an IC expressed it: “The voluntary organizations have their guidelines and training. While I can never be certain, I expect them to have a process for selecting and eliminating personnel, so that the people they choose to deploy are capable of solving the mission.”

Concordantly, the Danish interview data indicate a high level of trust in the volunteers organized by the Home Guard. Praising the smooth collaboration with the Home Guard, an IC expresses a generalized expectation that the organizational leaders know their capabilities:

We [the police] never really ask whether or not they [the Home Guard volunteers] can do the job. When I […] act as an incident commander, then I typically speak to the captain, an officer or the like, who leads his/her group. I channel tasks to them and then he answers if they are able to do it or not. We have no knowledge or opinion about who are capable of doing what in his group. If he says they can do the job, then we expect that they can do the job. (Respondent A)

The institutionalized belief that organized volunteers are familiar with common standards and routines also underpins the ICs’ trust in them. As part of their training programmes, FORF have developed a handbook for SAR operations defining common standards and emergency management routines, which underpin the professional volunteerism of their members and improve their trustworthiness in the eyes of the ICs:

It [the handbook] has improved both the collaboration and the effect of the collaboration between volunteers and the police. [Because] we can speak the same language, and we have the same mental models. When we arrive at an operation, then we can agree on the different statistic [probability] levels. […] There is much more professionalism now than before we had the handbook. (Respondent M)

Institutionalized collaboration between the public emergency management agencies and the NPO further enhances the ICs’ trust in their organizational leaders and affiliated volunteers. In Norway, for example, FORF representatives participate in the Local Rescue Coordination Centers, an institutionalized set of collaborative platforms responsible for coordinating the multi-actor emergency response in land-based operations. Many of the interviewed ICs emphasized the institutionalized public-non-profit collaboration in the LRCCs as an important channel for dialogue and for providing feedback to the organizations based on experiences from interacting with volunteers during operations. Allowing ICs to provide critical feedback in the aftermath of operations – and thus indirectly correcting unwanted behaviour from individual volunteers – the structured collaboration with FORF sustained their trust in FORF-organized volunteers during operations. At the same time, several of the ICs emphasized how previous experiences with key personnel in the organizations and ongoing interpersonal contact in-between operations enhance their trust in them. In some cases, the interviewed ICs explained their general trust in an organization as a consequence of such interpersonal trust, suggesting that regular interaction that builds personal trust can extent to organizational trust more generally. The ICs’ familiarity with the organizations, their leaders, and their training programs proves important for their trust assessments as it vouches for the capabilities of the organized volunteers. An IC explains:

It's both the fact that you've chosen to be part of that organization, and then you're dedicated to it. But it's also what the organization stands for. I know what it stands for and how it's organized as well. It's not just a group of guys getting together for a walk in the woods to search for someone. These are people who are truly dedicated, even during training and the education they undergo to participate in this. (...). I trust them because they come in their uniform, and then I know what they stand for. (Respondent M)

All in all, the results of the analysis show how NPOs facilitate trust between ICs and their organized volunteers, making the ICs more willing to cooperate with them. More specifically, they show how NPOs play a key role in generating and sustaining institutional trust in their organized volunteers through structures, procedures, and practices for vetting, educating, training, socializing, disciplining, leading and commanding their affiliated volunteers. Moreover, the study findings suggest that collaborative platforms, arenas and other forms of institutionalized collaboration between public and NPOs are important for strengthening inter-organizational familiarity, sustaining inter-organizational trust, and, by extension, enhancing trust in their affiliated volunteers.

Intermediated Co-production

In processes of intermediated co-production, NPOs temporarily organize citizens who want to assist the response operations. Our data show how the systematic and documented ability of the NPOs to register active citizens, assign them with relevant search areas, and log their activities make the ICs more prone to trust the involved citizens and engage in emergency management co-production with them. The organizations aid the process of keeping track of people, providing an overview of where they are at all times, which supports the ICs’ continual management of the situation and ensures crucial documentation of activities that is not only relevant in criminal cases, but also for informing relatives of the missing person about the SAR operation. As suggested above, these considerations are essential when the ICs decide whether to dismiss citizens or to engage in co-production.

Referring to a past SAR operation, a Norwegian IC reflects on both enabling and restricting factors in intermediated co-production:

We had about one hundred [organized] volunteers, and a hundred, well we can call them “civilians” or the “local population”. … But the Red Cross had a system in place to register them, to log where they had searched, mark the search areas, and provide information. They were still given the same urban search areas and we did not send them into the forest. Partly because I don’t know who these people are. There might be people involved that are not experienced hikers, and we could suddenly have another search operation going on. I will not risk that. (Respondent V)

In other words, while NPOs could reduce risk by registering and managing citizens, engaging with untrained citizens with unvetted competences still poses a considerable risk, limiting the scope of co-production (albeit to a lesser extent than in spontaneous co-production). A recurring theme in both the Norwegian and Danish interviews, this notion of the risks of involving untrained citizens permeate the trust assessments across the board. Nevertheless, the Danish ICs expressed even stronger reservations relating to the ability of the specific NPO Missing People to provide the necessary trust-building mechanisms for sustaining their confidence in the activities of engaged citizens, restraining their willingness to engage in co-production with them:

It is quite impressive how many they [Missing People] can mobilize, but we will usually make use of helicopters, drones, and dogs. So typically we won’t call up Missing People ourselves. ‘Cause one thing is that they have been there, but it is not enough for us to say that he [the missing person] is not there. (Respondent A)

As such, the case of Missing People demonstrates how the scope of intermediated co-production is also closely related to the ICs’ trust in the managerial and organizational capabilities of the NPOs. For example, a Danish IC stresses the importance of intermediate organizations providing some structure and guidelines for citizen participation in SAR operations:

It can be a problem if you’re not loyal to the incident command. The military and the police are raised on chains of command and not letting our feelings govern our behaviour. In scenarios, where civilian volunteers assist, a gamut of emotions may come into play. It is not ill will, you have to remember that: no one is there to wreck it. So to a large extent it is about communication and setting a clear framework for things. (Respondent D)

While, missing people often show up when children and elderly go missing, they do not participate in any collaborative platforms or other forms of structured collaboration with the public emergency management organizations. Generally, the ICs know little about their internal organization, including how and to what extent they educate their organizational leaders in SAR management. Over time, several of the ICs have encountered some of the same voluntary leaders with whom they build experience of how to collaborate. But the lack of familiarity with the organizational structures and activities of Missing People prevent them from building a stronger foundation of generalized trust in all voluntary leaders from Missing People by virtue of their organizational affiliation. The IC quoted above expresses this sentiment in a subtle manner:

Missing people include consistent people who are very active, and perhaps some who are not deployed that often. But I don’t know if they have any form of introduction to the work of the police. Obviously, they can’t learn everything, but they don’t have to either. But I actually don’t know if they have any general introduction on how to act in humanitarian search and rescue operations. (Respondent D)

In sum, the analysis shows how NPOs build trust in active citizens through various measures of registration, leadership and command that create accountability and lowers the risks associated with entrusting unaffiliated citizens, enabling ICs to make the necessary leap of faith involved in the co-production of emergency response. At the same time, however, the findings also indicate the limits of NPOs’ trust-sustaining capacity. Specifically, the results suggest that organizational measures for temporarily organizing and managing involved citizens such as citizen registration, search area assignment, and documentation of activities contribute positively towards emergency management co-production. However, the inherent impossibilities of systematically vetting, training, and socializing unaffiliated citizens in accordance with norms and needed competencies of emergency management (as with the organized volunteers) restrict the scope and depth of intermediated co-production. Yet, the findings indicate that the degree to which intermediate organizations have implemented measures of registration, leadership and command, and the degree to which the ICs are aware of the measures taken, influence the level of trust and thus the conditions for co-producing emergency response with temporarily organized citizens.

Discussion

The study findings provide important insights into the relationship between public ICs, NPOs, and citizens in the co-production of emergency response. They show that ICs exhibit greater trust in citizens when NPOs act as intermediaries who register, lead, and command citizens during operations. As such, the study shows the strengths of intermediated co-production compared to spontaneous co-production, but also its inherent limitations compared to cooperation with organized volunteers. The study thus contributes to a better understanding of NPOs as trust-builders in emergency response co-production, but also provides a more nuanced perspective on the role of intermediaries in co-production in general (cf. Haug, 2021).

One important contribution of the study concerns the role of intermediaries in mediating the relationship between trust and control (cf. Bijlsma-Frankema & Costa, Reference Bijlsma-Frankema and Costa2005; Edelenbos & Eshuis, Reference Edelenbos and Eshuis2012). Research has shown how the co-production of emergency response involves considerable power and resource asymmetries between ICs, NPOs, and citizens (Krogh & Lo, Reference Krogh and Lo2023a). This is also evident in our study as ICs are more willing to trust temporarily organized citizens who know and adhere to ‘the rules of the game’, follow orders and are willing to subject themselves to some degree of centralized command. Other studies of co-production have found that such an unequal power distribution may lead to a situation, where the state come to dominate, capture or co-opt citizens in ways that limit the full potential of co-production (Trætteberg et al., Reference Trætteberg, Lindén and Eimhjellen2024). However, our study suggests how NPOs can act as a buffer between public incident commanders and citizens through appropriate organizational procedures, processes and activities that levels the playing field of emergency management co-production and grants citizens a more central role in solving common problems (cf. Tuurnas et al., Reference Tuurnas, Paananen and Tynkkynen2023). The study thus provides a nuanced perspective on the role of NPOs in balancing control and trust in processes of co-production.

On a more practice-oriented level, our study suggests how NPOs can develop trust-building structures, procedures and practices to improve the conditions for co-production. Specifically, it suggests a number of measures that NPOs may implement to bolster their capacity to act as trust-building intermediaries. First, they may install effective procedures for registering volunteers, introducing accountability and vouching for their benevolence and (perhaps to a lesser extent) their competencies and integrity. Second, they may make citizens more reliable by instructing them in commonly agreed upon operational procedures, tasks and areas of operation. Third, they can help monitor and document the activities of citizens for ICs’ use during operations and in the subsequent evaluation of operations. Fourth, they may establish effective leadership and command structures that enable them to correct (and perhaps even dismiss) citizens who violate agreed upon procedures. Fifth, they may engage in inter-organizational collaboration with public authorities before, during and after operations, for instance by participating in formal networks, platforms and arenas, in which they can communicate their organizational structures, procedures, and practices to ICs in order to enhance their trust in the NPO and, by extension, the temporarily organized citizens. By building institutional trust, inter-organizational collaboration can thus contribute towards enhancing the “opportunity spaces” for co-production (Brix et al., Reference Brix, Tuurnas, Mortensen, Thomassen and Jensen2021).

Conclusions

This article set out to examine how NPOs build trust in engaged citizens and thus facilitate the co-production of emergency response. Reporting on a qualitative study of emergency management co-production in Denmark and Norway, we have shown how NPOs enhance trust in citizens through structures, procedures, and practices for registering, leading and commanding citizens during emergency response. The findings thus suggest how NPOs may develop their organizational processes and activities to strengthen their role as intermediaries and improve the conditions for emergency management co-production. On a more general note, our study demonstrates how trust theory can contribute to a better understanding of the institutional determinants and enablers of public service co-production. Today, many NPOs are experiencing a decline in formal membership, while more informal and ad hoc forms of volunteering are increasing. Understanding the role of NPOs as trust-building intermediaries in co-production can provide clues as to how voluntary organizations can renew their role and relevance in other fields as well. We therefore hope that this study will provide new insights and inspiration for NPO researchers and co-production scholars, practitioners and policymakers not only within, but also beyond the field of emergency management.

To cover a broader range of empirical settings and exploit the analytical power of comparative studies, future research could study the intermediary role of NPOs in societies and service sectors with less generalized and institutionalized trust between public professionals and citizens. We could expect a greater need for NPOs as trust-building intermediaries for co-production to unfold in such settings. As the same time, their conditions for taking on this role is likely to be more challenging, perhaps to a degree, where the intermediary function is out of reach. To illicit these and other pertinent issues, more studies of the role of NPOs in intermediated co-production within and beyond the field of emergency management are warranted.

Funding

The research leading to the presented results has received funding from the Research Council of Norway within the frame of the program "SAMRISK" under Grant Agreement No. 296064.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

All human participants have entered the research voluntarily and consented to the use of the data for research purposes.

Appendix

See Table

Table 1 Respondents

Label |

Nationality |

Gender |

Organisation |

Job function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

A |

Danish |

Male |

Police |

Superintendent |

B |

Danish |

Male |

Police |

Chief of staff |

C |

Danish |

Male |

Police |

Superintendent |

D |

Danish |

Male |

Police |

Superintendent |

E |

Danish |

Male |

Police |

Incident commander |

F |

Danish |

Male |

Police |

Incident commander |

G |

Danish |

Male |

Police |

Incident commander |

H |

Danish |

Male |

Local Fire Branch |

Manager of voluntary response team |

I |

Danish |

Male |

Local Fire Branch |

Chief of staff |

J |

Danish |

Male |

Local Fire Branch |

Incident commander |

K |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Superintendent |

L |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Incident commander |

M |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Incident commander |

O |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Chief of Staff |

P |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Incident commander |

Q |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Superintendent |

R |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Incident commander |

S |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Superintendent |

T |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Dog handler |

U |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Incident commander |

V |

Norwegian |

Male |

Police |

Incident commander |

1.