Antiquaries and the Literary Past

Ossian’s appeal to the late-Enlightenment reading public lay not only in his uncanny settings and spooky scenes but also in the remarkable tale of his retrieval: snatched from oblivion in a remote corner of the Old World, where his memory lingered among balladeering Highlanders in desolate mountain ranges and in almost-illegible manuscripts. The mission of James Macpherson seems almost like an Indiana-Jones-style quest for lost treasures. A difference between the two is that the fictitious Indiana Jones is an archaeologist, a scholarly specialism that did not yet exist in Macpherson’s day. Those who investigated antiquities were called antiquaries, and they had a wide remit: ‘antiquities’ included material remains (be they from the medieval, the classical or the prehistoric past) and whatever could be found in ancient manuscripts, be they ballads, genealogies, law texts or chronicles. Macpherson was an innovator in that he searched for antique remains in living oral poetry.1

Another difference is that antiquaries had no academic or professional standards to go by. They were learned, dedicated amateurs, usually with a steady independent income, and although there were some fledgling associations (a Society of Antiquaries was established in London in 1707 and another one in Edinburgh in 1780) they worked largely on their own and on whatever material they happened to come across. They were also often carried away by their enthusiasm: their interpretations of the past were, more often than not, over the top, unchecked by sceptical reservations or by factual background knowledge. They had no qualms about tracing the origin of the Irish and Scottish Celts back to Carthaginians or Phoenicians. In the eighteenth century, before solid comparative linguistics, antiquaries frantically tried to read Gaelic with the help of Greek and Hebrew dictionaries. In his novel The Antiquary (1816) Walter Scott drew the portrait of such an amateur scholar of the Macpherson generation with affectionate irony; fondly, because Scott was himself an antiquary at one remove. He worked on ancient ballads and minstrelsy, on Scottish legal and social history, on the country’s ancient manners and customs, and he hoarded material remains of the past at his museum-mansion at Abbotsford. And he was a proud, card-carrying member of the Scottish Society of Antiquaries. But Scott’s Antiquary also signalled that this type of antiquarianism was a thing of the past. In the next century, the investigation of the past would split up into the scholarly disciplines of archaeology, philology, and the studies of folklore and mythology. The undisciplined imagination with which antiquaries had approached the past was no longer suitable to these new, respectably academic offshoots, and it became the characteristic feature of a Romantic literary genre of which Scott was the first and foremost practitioner: the historical novel (on which, see Chapter 7).2

Cesarotti’s Italian edition of Ossian carried, besides the frontispiece that we have seen in the previous chapter (Figure 3.1), another vignette on its title page (Figure 4.1). It shows a dapper man, obviously an ‘amateur gentleman’ rather than a menial, wearing a hat – probably against the sun, because the surroundings look more Italian than Highland Scottish. He is digging with a spade around some half-buried objects; a marble slab next to him carries a quotation from Horace (Epistles I.6:24–25), ‘Whatever lies buried below ground, time will bring to light’. The gentleman is clearly an archaeologist, and his work is to unearth the remains of the past. That is what was famously going on in Cesarotti’s Italy at the time: the ruins of Pompeii were being uncovered in these very decades, and caused a sensation. Word had spread to Germany as a result of J. J. Winckelmann’s letters ‘on the discoveries at Herculaneum’ published in 1762 and 1764.Footnote * This is an altogether different frame for reading Ossian from the ‘ghosts on a moonlit mountain top’. Ossian was an antiquarian sensation.

Figure 4.1 Title-page vignette for Melchiorre Cesarotti’s Italian version of Ossian (1763).

The juxtaposition of Ossian with Homer, which we noticed in Chapter 3, is not just a typological one (both were sublime original geniuses relating the heroism of the ancestors in epic form) but also a historical one. With Ossian, Scotland (and, by extension, Northern Europe in general) is rediscovering its ancestral antiquity. Until then, classical and biblical antiquity had held the monopoly on Europe’s most ancient cultural memories; that monopoly was now broken. The impact of Ossian was that Northern Europe could opt out of this Mediterranean, biblical/classical ancestral antiquity and look back on its own cultural roots. That pattern was reinforced by the fact that at the same time Nordic antiquities, rooted in the Edda and the Heimskringla, were being reactivated by Scandinavian antiquaries. The result was that for a while, the ‘Gothic’ (Scandinavian) and ‘Celtic’ antiquities of Northern Europe were being lumped together; the trend had been set by Paul-Henri Mallet’s Monuments de la mythologie et de la poésie des Celtes, et particulièrement des anciens Scandinaves (1756). By that time, the Swiss antiquaries Bodmer and Breitinger had also retrieved a manuscript of the Nibelungenlied, which they presented to the reading public as ‘Chriemhild’s Revenge’ (Chriemhilden Rache), commenting that, although it fell short of the Aristotelian rules for tragedy, it could stand, as an epic poem, beside the pre-Aristotelian epic poet Homer.3

All this dealt a huge blow to the still prevalent classicism of the time. Until then, the cultural rearview mirror had reached back to the periods of humanism and the Renaissance and then, bypassing the dark and scantily known Middle Ages, had focused on the biblical and classical periods – the recourse to which had allowed those humanists and their Renaissance successors to emerge from Europe’s medieval benightedness. Now, however, Northern Europe’s vernacular, non-classical ancestry could be traced back further along native lines towards an origin, and an original genius, of their own. And the Middle Ages themselves became something more than a centuries-long night-time of impenetrable barbarism: the Middle Ages now became a literary Pompeii, a continuum for the nation’s buried cultural heritage, with chivalric and epic heroes such as King Arthur and Siegfried the Dragon-Slayer appearing in a favourable, prestigious light. These philological discoveries not only inspired the medievalism of the Romantic century but also necessitated a new, national form of literary history writing. Literary history had to be rewritten and to accommodate in its opening chapters these newly discovered materials: ancient, heroic, vernacular.4

Cesarotti himself was quite sensitive to this ‘shock of the old’. In his annotations to Ossian and his Homer translations, he instilled a great many of Vico’s theories of cultural history, notably that each civilization articulates its cultural self-awareness, and marks its emergence into history, in a primordial Big Bang where laws, epic-heroic poems and religious myths are almost undifferentiated. These notions in turn found their way into the German translation of Ossian (which followed the Italian version rather than Macpherson’s English one). We may even surmise that it is through the intermediary stepping-stone of Cesarotti’s Ossian that Vico’s ideas began to spread in the Republic of Learning.5

Cesarotti’s Ossian presentation triggered a veritable paradigm shift in European literary history, which outlasted the brief fame of Ossian himself. It triggered a form of literary archaeology (digging around to see what submerged things could be brought to the light of day). The treasures found by Macpherson led to a gold rush; and the Klondike of that literary gold rush were libraries and archives – which, as it happened, were now beginning to make their riches publicly available.

Archaeology in the Archives

Libraries are like sponges: they soak up available books and texts circulating in the marketplace, and that ingestion is by and large a one-way process. Libraries siphon off the marketplace: they are predicated on acquiring and keeping stuff. Over the decades and centuries – as institutions, libraries can be very long-lived – dispersed materials drift from private ownership into library collections. The oldest of these are monastic libraries and court libraries, with college/university and municipal libraries following in the later Middle Ages. The public had only limited access to these.

But periodically, sponges get squeezed, and then their accumulated storage either trickles out or gushes out profusely. Sometimes, libraries are opened to the public: Florence’s Biblioteca Laurentina was opened to scholars in 1571, and Louis XIV opened the Bibliothèque du roi to the public in 1692. A major squeeze occurred with Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. The monastic libraries of medieval England were plundered by the king’s officials, and a great number of ancient manuscripts circulated among private owners (John Leland, William Camden, Matthew Parker, Lawrence Nowell, Robert Cotton) before finally settling down, once again, in other libraries: Matthew Parker’s books became the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and Robert Cotton’s library, donated to the nation in 1700, was merged with the Sloane, Harley and Royal libraries to form the British Museum’s library in 1757. It was here that an inquisitive Danish scholar, Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin, located the sole surviving copy of the Beowulf epic in 1786–1787. A first edition was published in Copenhagen in 1815. Literary archaeology was beginning to bring long-lost manuscripts back to the light of day.

At precisely this time, a great library squeeze was underway in Europe. As in Henry VIII’s day, it targeted, at least initially, monastic libraries. The process began with the suspension of the Jesuit order in the 1770s. In Lisbon, this meant that the Jesuitical Ajuda library was transferred to a new, state-run teaching institution; and it was here that the oldest surviving medieval manuscript of vernacular love songs came to light: the Cancioneiro da Ajuda. A first edition was published in Paris in 1823.

After the Jesuits, under Emperor Joseph II, the libraries of contemplative orders such as the Benedictines were targeted; then came the nationalization, by the authorities of the French Republic, of monastic and noble libraries in France; and then came the libraries, in the German lands, of those church establishments that were annexed by Napoleon or (in the great Reich reshuffle of 1803) were placed under the control of temporal lords.Footnote * In France, the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal was formed in Paris, incorporating many former monastic libraries from the metropolitan area, and the former Bibliothèque du roi and Bibliothèque mazarine became public research institutes. In Germany, the huge libraries and archives of formerly self-governing ecclesiastical establishments were transferred to the court libraries of Vienna, Munich and Stuttgart, and as part of that transfer they were inventorized and recatalogued. The Munich court library swelled to become one of the largest in Europe, a process mirrored at slightly smaller scale at the Württemberg Library in Stuttgart. Finally, when Napoleon annexed the Papal States in 1808, even the mother of all libraries at the Vatican was placed under the bureaucratic management of French civil servants. And men of letters descended in great numbers on these newly accessible hoards, made many discoveries and laid the basis for many a scholarly career. In Munich, soon to become the capital of a Napoleon-created kingdom, the court librarian Johann Christoph von Aretin encountered, with some wistfulness, an old document about Charlemagne in the mediatized library of Freising Abbey. He published it in 1803 with a nostalgic preface linking, quite aptly, the simultaneous overhaul of ancient libraries and overthrowing of ancient monarchies.

It is now a thousand years ago that Charlemagne founded the German empire. I alert my readers to this fact, not to draw their attention to the remarkable changeability of things during that timespan, or to make them ponder the recent events which have appeared to threaten that very empire with an overthrow after its millennial existence; rather, I would mark a literary jubilee of that great occurrence, and an occasion presented itself when I could consult a remarkable ancient German manuscript in the most ancient abbey of Weihenstephan near Freising, and which with all the literary treasures of the Bavarian monasteries has been lodged in the Munich court library.6

One of the biggest finds was in Rome. The Vatican library, now under Napoleonic administration, was inventorized by a librarian called Gloeckle – notorious for his drunkenness and known in Rome as il porco tedesco – together with the literary historian J. J. Görres; what they found was the old collection of the Palatinate counts on the Rhine, which had been taken from Heidelberg in 1622 as war booty and presented to the pope. This ‘Biblioteca palatina’ turned out to be packed with long-lost classics from medieval German literature: chivalric romances, Tristan, Reynard the Fox, Lohengrin (of which Görres himself would bring out an edition in 1813) and much besides. Görres sent an open letter to the Heidelbergische Jahrbücher der Literatur in 1812, hoping to raise subscriptions for a printed edition of all these classics. Two centuries later we can still sense the breathless excitement of these thrilled bookworms.7

The European Republic of Philology

When we look at the text editions that came out between 1800 and 1840, we see that they include practically all the ‘classics’ that now feature in the opening chapters of literary history books. Besides the Portuguese cancioneiros, Reynard, Beowulf, the Nibelungenlied and Lohengrin, the list includes the French Chanson de Roland (discovered in the mid-1830s in the Bodleian library by Francisque Michel), the Russian/Ukrainian Lay of Prince Igor’s Campaign, the Dutch Legend of Saint Servatius, the Irish Annals of the Four Masters and Deirdre/Cuchulain tales, and many others. Literary histories were, quite literally, being rewritten and traced back to their vernacular and tribal origins rather than to classical antiquity.

Friedrich Schlegel gave a name to the scholars who were doing this work. Rejecting the speculative waywardness of the old-school antiquaries, he called for a systematic comparative-historical method, and in his diaries began to call this line of work philology. In doing so he revived an old Latin word for ‘erudite bookworm’, which, however, had been given a trenchant new importance in Vico’s Scienza nuova. There, Vico had compared two forms of knowledge production, one dealing with the nature of things and the other with the meaning of things. The former Vico called philosophy, the latter philologia. The underlying meaning of that term was a preoccupation with logos, the language-empowered faculty of human cogitation. Schlegel applied this in his Viennese lectures on ancient and modern literature (1812, published 1815). What makes humans different from animals, Schlegel argues, is language (with each human society developing their own language: see Chapter 6). The primary function of language, besides communication, is commemoration: the articulation of memories and their formulation into something that is more than a fleeting state of mind. Once these memories take the form of crystallized narratives recalling important events and figures from a past that is longer than a human lifespan ago, such a society has a culture: it is no longer a band of grunting cavepeople but on its way to becoming a civilization. The primal role of literature, for Schlegel, is to encapsulate collective (he calls them ‘national’) memories.

What appears important above all else for a nation’s development and indeed its spiritual existence is that a people should have great national memories, which mostly reach back into the dark times of its first origins, and which it is the great task of literature to maintain and to celebrate. Such national memories, the finest inheritance that a people can boast, offer advantages that cannot be matched by anything else. When a people finds itself exalted and ennobled in their feelings by their possession of such a great past, of such memories from ancient days, in short: of such a poetry, we must admit their higher standing in our esteem. … Remarkable deeds, great and fateful events do not suffice in themselves to gain our admiration and to sway the judgement of posterity. A nation’s value depends on its clear awareness of its deeds and destinies. This self-awareness of a nation, as articulated in contemplative and descriptive works, is its history.8

Schlegel in fact updates Vico for the new century. He combines the textual investigation of ancient literary history with a sense of comparative historical linguistics and with what he calls ‘Völkergeschichte’; as such, he is also one of the great harbingers of a new philology, which takes over from the antiquaries of the preceding generations.9

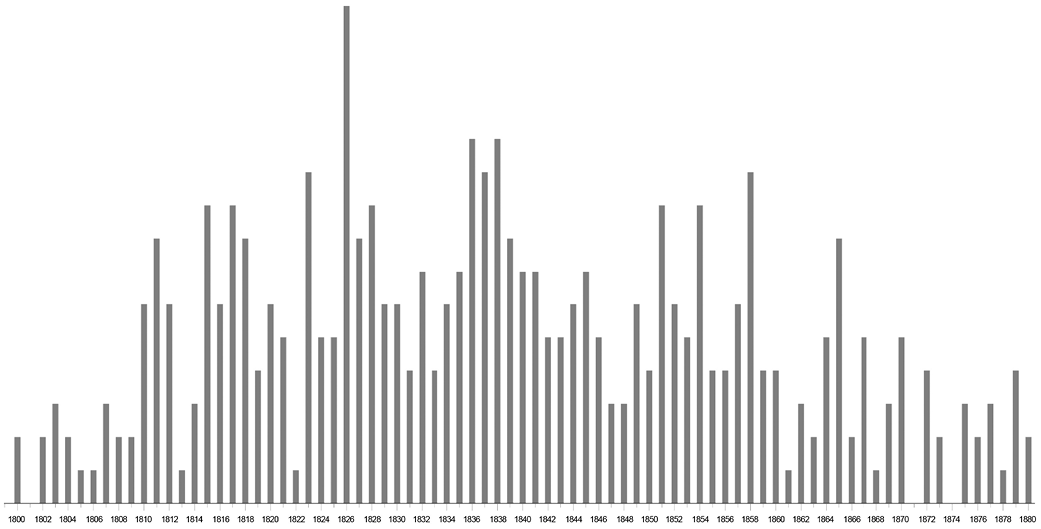

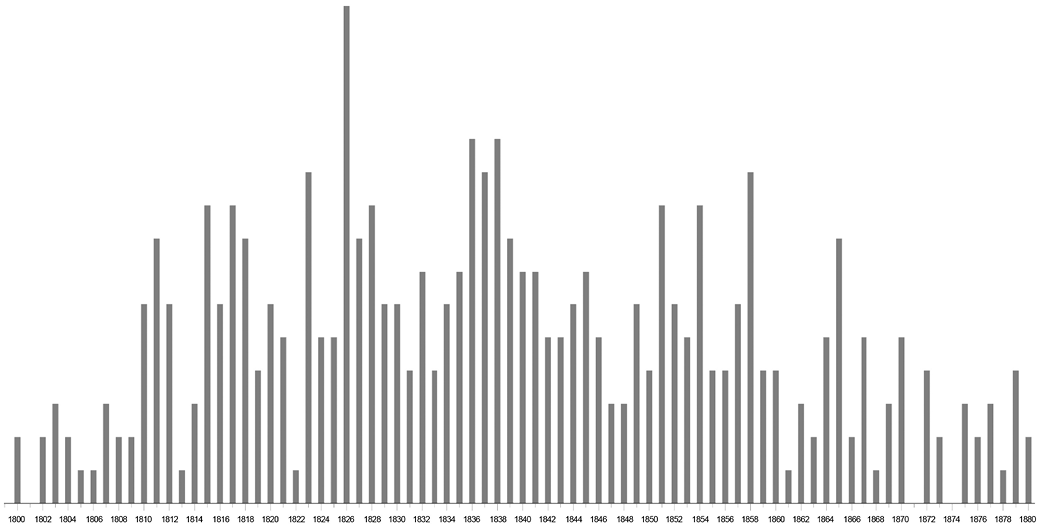

The takeover was effected by a wave of re-editions of vernacular classics. The Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe lists some 500 editions of ancient texts over the century,Footnote * with productivity peaks in the 1820s, the late 1830s and the 1850s (Figure 4.2). Productivity after 1860 consists mainly of re-editions of the initial harvest and of belated text discoveries in comparatively poorly archived cultural communities.

The striking thing about this rediscovery of nations’ vernacular roots was that, while it served to set off these nations against each other as each having their own, distinct cultural mainsprings, it was an almost pan-European enterprise. It was not just that German libraries yielded medieval texts to local (German) philologists, while French and Portuguese ones proved, in separate but parallel developments, fertile working grounds for their local users; far from it. Those users travelled to libraries outside their own countries (as we have encountered, or will in the following pages: Thorkelin in the British Museum, Michel in the Bodleian, Grimm in Paris, Görres in Rome, and Hoffmann von Fallersleben in Vienna and Valenciennes). Their rediscoveries were part of a development that all of them in their different countries recognized as a joint, multinational concern. The contacts between them, whether amicable or competitive, were intense, and they were keenly aware of each other’s work. The epistolary network of Jacob Grimm (13,000 letters, Figure 4.3) casts a dense, far-flung web over all of Europe; it can be confidently said that it enmeshes everyone involved in such enterprises, if not directly, then at most at two degrees of separation. Anyone who was active in philology in the nineteenth century exchanged letters with Grimm or, failing that, with someone else who did.10

The intensity and spread of this network is deeply meaningful for our understanding of Europe as a unified intellectual space. The philologists were the last representatives of the old Europe-wide Republic of Learning. The modernization of the university system, with humanities faculties and historical and philological departments, was a development that took place all over Europe; so was the establishment of national academies, libraries and archives, along with the professionalization of whose who worked in all those new types of institutions. And while those working environments might be compartmentalized by state, the people working in them were in mutual contact, constantly exchanging information, aware of each other’s work. The fact that so many agents in a ‘cultivation of culture’ crop up in parallel forms in different countries is, then, not a matter of happenstance or parallel responses to similar circumstances: they are the systemic, Europe-wide manifestation of a transnational communicative network and a homogeneous intellectual space. Different though Europe’s states were in their governance and in their socio-economic states of development, the philologists and scholars, from Anders Sjögren in St Petersburg to Alexandre Herculano in Lisbon, were part of a single intellectual continuum.

The ‘cultivation of culture’, of which this new type of knowledge production forms part, is itself an important aspect of ‘Phase A’ of national movements as theorized by Miroslav Hroch: the phase of national consciousness-raising. The later phases (B and C) of those national movements – social demands and political activism – may pan out differently according to the local conditions of the various European societies, regions and countries. But unlike those later phases, Phase A is very strongly transnational. Musical, literary and artistic fashions spread, and so does scholarship and knowledge production. Ossian, Herder, Byron, Scott, Grimm: the influence of these names reaches far beyond their country of origin or their place of work. Nothing in this cultivation of culture takes place in national isolation.11

Literary Histories, National Identity

Ironically, the editions of national classics, supported though they were by a pan-European intellectual vogue, had a deeply nationalizing effect on their readership. Culture and literature were now seen as historical traditions carried, specifically, by the nation over the centuries. In some instances the nation-building effect was announced in so many words as a deliberate intent at the forefront of the philologists’ mind. The most famous example is the preface given by Friedrich Heinrich von der Hagen to his edition of the Nibelungenlied (Reference Hagen1807). Von der Hagen was evidently trying to come to terms with a crisis: the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire and the Napoleonic hegemony over the German lands.

[I]n present-day Germany, torn by destructive tempests, the love of the language and literature of our virtuous ancestors is alive and active, and it seems as if people seek in the past and in its poetry what is so grievously declining today. And this need for comfort is the last remaining sign of the imperishable German character, which, raised above all servility, will sooner or later always break foreign bonds and, wiser and chastened, will retrieve its inherited nature and liberty.

…Nothing can afford a German heart more comfort and true edification than the most immortal of all heroic lays, which from long oblivion re-emerges in vital and rejuvenated form: the song of the Nibelungs, undoubtedly one of the greatest and most admirable works of all periods and nations, grown and matured wholly from German life and sensibility, and pre-eminent for its sublime perfection among the admirable remains of our long-forgotten national poetry – comparable to the colossal edifice of Erwin von Steinach [i.e. Strasbourg Cathedral]. No other lay can so move and grip a patriotic heart, delight and fortify it.

Twenty-five years later, the preface of Jan Frans Willems’s edition of the Flemish Reynard tale used the occasion to upbraid his countrymen for their adoption of French culture:

Our Flemish Reynard surpasses all other poems on that theme. … in a word, it is by far the best poem (Dante’s Divina commedia excepted) which has come down to us from the Middle Ages. And it is a Belgian one! And the Belgians know it not! And the editing of it was left to Germans! … May this, my edition of the more ancient part of Reynard the Fox, contribute to the revival of our once-cherished language, at a time when our country is being inundated by French trash!12

Ancient literature is now becoming a national heirloom, and an argument in the imperative to maintain the nation’s cultural continuity. France, in its ‘culture of defeat’ after 1871, gives the most heightened examples of this nationalization of the literary heritage. The Chanson de Roland, first published in the 1830s, gained fresh national symbolism in the traumatic events of 1870–1871. Much as Von der Hagen in 1807 had taken comfort from the death-defying heroism of the Nibelungen heroes, so too in 1870 Léon Gautier turned to the stalwart Roland, killed on the medieval battlefield of Roncesvalles while covering the army’s retreat to his ‘douce France’. Gautier wrote his preface

wrapped up in sadness and with tears in my eyes, during the siege of Paris, in those lugubrious hours when we might have thought that France was in its death-throes. And so what is the Roland? It is the tale of a great defeat for France, from which France has risen gloriously and which has been fully atoned for. What could be more topical? The defeat so far is the only part we have lived through, but this Roncesvalles of the nineteenth century has its own glory … It cannot be, really, that she should die, that France of the Chanson de Roland, which is still our France … where were they, those boastful invaders, when our Chanson was written? They roamed in savage bands through the gloom of nameless forests; all they knew was how to plunder and kill.

As Gautier wrote his preface, and during the siege of Paris, Charles Lenient taught a lecture course at the Sorbonne on ‘La poésie patriotique en France’, and Gaston Paris lectured at the Collège de France on ‘La Chanson de Roland et la nationalité française’.13 When in 1875 Gaston Paris and his father Paulin Paris founded the Ancient French Texts Society, its philological aims were also presented as a ‘national enterprise’:

The Société des anciens textes français is a national enterprise … it needs the support of all those who understand the importance of tradition, all those who realize that the strongest bond keeping a nation together is piety towards our ancestors, all those who are vigilant about the intellectual and scientific standing of our country amidst other peoples; all those who love, throughout all the centuries of its history, that douce France for which one could already die such a good death at Roncesvalles.14

‘Roncesvalles’ echoes through the period of French revanchism, 1871–1914, much as Nibelungentreue would haunt German history in the twentieth century. If we want to understand what made Churchill and Stalin commission cinematic recalls of Henry V and Alexander Nevsky, here are the origins of that national historicism.

Entangled Roots

As the new philologists gradually professionalized into state-salaried archivists, librarians and professors (of history, philology, archaeology), they became civil servants of the state. The antiquaries had been gentlemen of leisure; the new professionals acquired not only a professional, academic work ethos but also a sense that their knowledge production was a service to the nation. When, in 1846 and 1847, Jacob Grimm called together two countrywide congresses of Germanisten (German philologists, including legal and cultural historians), the gathering showed how the new post-antiquarian university disciplines were now positioning themselves as a useful helpmeet to the nation’s identity. They manifested this with the same patriotic arguments that we have encountered in the later manifesto of the Society of Ancient French Texts: the importance of tradition and of ancestral piety, and the vigilant safeguarding of one’s country’s intellectual and scientific standing amidst other peoples. Concretely, the Germanisten proceedings revolved around an assertion that Schleswig-Holstein had always been, and should once again become, German; a call for the ancient Germanic liberty of trial by jury (an oblique dig at arbitrary monarchical government); and the need for a proper German dictionary. The 1846 meeting was held in St Paul’s church, Frankfurt; two years later, no fewer than thirty-one of the participating Germanisten would meet again in the same spot, this time as delegates of the 1848 Frankfurt National Assembly.15

Germany was in the forefront of the new philology, establishing benchmarks for all of Europe in many fields. The presiding genius was Jacob Grimm, together with his (slightly more withdrawn and amiable) brother Wilhelm. Nowadays known mainly as the collectors of fairy tales (Kinder- und Hausmärchen, literally ‘Wonder Tales for Children and the Household’, 1812–1815), the Grimms were also the instigators of the huge lexicographical enterprise of the ‘German Dictionary’ (Deutsches Wörterbuch, 1852–1961) and collectors of German legends (Deutsche Sagen, 1816–1818). Jacob himself edited ancient German texts and legal customs, extrapolating from the latter a generalized ethnography of public mores and their enforcement (‘German Legal Antiquities’, Deutsche Rechtsaltertümer, 1828); we will encounter, further on, his German mythology and his history of the German language and its dialects (Geschichte der deutschen Sprache, 1848). The breadth of these interests recalls the antiquarians of yore, and indeed Grimm could be prone to flights of fancy in interpreting his material; but his data management was thorough and rigidly systematic. No amateur he: he was a legal scholar by training and had been a librarian in his first employment. That he was firmly part of the new comparative-historical paradigm is manifested triumphantly in his comparative grammar of the Germanic languages, the Deutsche Grammatik (1824–1836), in which he went as far as formulating linguistic ‘laws’ (regularities in historical consonantal shiftsFootnote *). It was the first time such ‘laws’/regularities had been observed in human culture rather than inanimate nature. Among fellow philologists, this gave Grimm a scientific stature comparable only to that of Newton. In addition, he was involved in momentous political crisis moments. When Jacob and Wilhelm were dismissed as professors at Göttingen University in 1837 for refusing to acquiesce in the arbitrary autocracy of the incoming King of Hanover, they became martyrs to the cause of academic freedom, and Jacob was a delegate in the Frankfurt National Assembly of 1848.16

The Grimm-style German ‘new philology’ inspired scholars in Spain and Portugal (Hermann Böhl de Faber and Carolina Michaëlis de Vasconcellos). At Oxford, the Anglo-Saxonist Kemble and the Sanskritist Max Müller were Grimm adepts. Even French philology in France was inspired deeply by Grimm’s pupil Friedrich Diez, to the point that the manifesto of the Ancient French Texts Society complained of ‘Germany being the European country where ancient French texts are printed most’.17

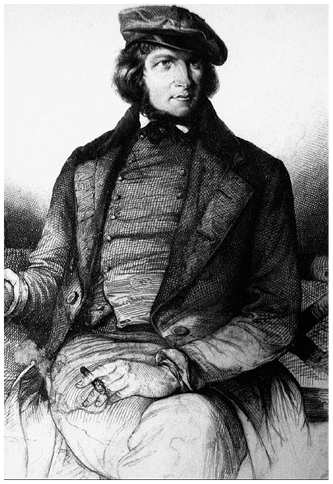

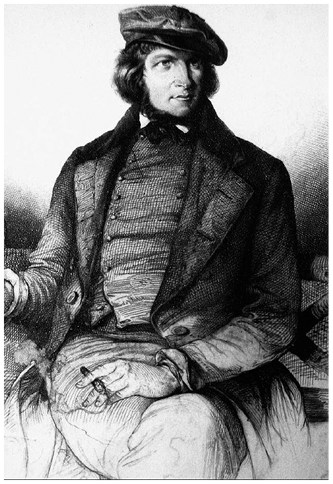

Also, Jan Frans Willems invoked Grimm when he chided Belgium for its neglect of its Flemish-language roots. Indeed, the ‘Flemish Movement’ – one of Europe’s best-documented national movements – leaned heavily on German intellectual aid in its cultural insurgency against the dominance of French. A stalwart supporter of the Flemish cause was the poet-philologist and political activist August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben, a larger-than-life figure mainly known as the author of the ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ anthem (Figure 4.4).18 Hoffmann was a fervent adherent of the Grimm school of philology and made a name for himself as a canny investigator of archives and libraries (he edited two volumes of ancient German ‘treasure troves’, Fundgruben, published in 1830 and 1837). In the many places he visited on his philological quests, he invariably sought out kindred spirits who, like him, were inspired by the glories of the vernacular literary tradition. This made him a ‘networking’ mediator among the various national revival movements that these kindred spirits were involved in. A hub of these was formed around the Vienna librarian and philologist Jernej Kopitar. While on a visit there, Hoffmann joined the Stammtisch or regulars’ table at the inn where the Slovenian Kopitar gathered intellectuals from the Slavic minority populations of the Habsburg Empire – a typical instance of the intensive private and convivial networking among these Romantic scholars.19 While in Vienna, Hoffmann also got wind of the possible whereabouts of a long-lost medieval German manuscript – somewhere near Ghent, in Flanders, where Jan Frans Willems had edited the Flemish Reynard.

Figure 4.4 August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben in the garb of a nationally minded wandering student: Dürer-inspired hairstyle, beret, unstarched collar, tight waistcoat. The full portrait also shows a walking stick and a drinking gourd.

Hoffmann immediately hastened from Vienna to Ghent, in the process boarding one of the very first steam trains to run on the newly opened railroad north from Brussels. He and Willems then travelled from Ghent to the public library of Valenciennes, where the French authorities, who had closed down the ancient monastery of St Amand des Eaux, were rumoured to have lodged its collection of books and manuscripts. They hit the jackpot: what they retrieved was the long-lost ninth-century Ludwigslied, one of the most ancient poetic texts in vernacular German. Only a few months later, their edition of the manuscript appeared in print (Elnonensia, 1838).

Hoffmann was familiar with Flanders and its literary history; he had been editing ancient Flemish texts since 1833 in a series called Horae Belgicae. Indeed, it is to this German’s editorial work that Dutch and Flemish literature owe many of the first printed versions of their medieval heritage. But by 1838, when Hoffmann visited Ghent, the climate was shifting. We have seen how Jan Frans Willems in 1835 was already chafing at the pronounced francophilia of the newly independent Belgian state and the marginalization of Flemish culture in that state. Hoffmann was fêted by Willems in a convivial club of Flemish-minded intellectuals called, tellingly, De taal is gansch het volk – ‘The language is, entirely, the nation’ – and Hoffmann, impressionable and enthusiastic as ever, now started to support the Flemish emancipation cause with his accustomed fervour. That same year, he wrote a firebrand introduction to yet another text edition (Altniederländische Schaubühne, 1838), in which he vehemently denounced the fact that on his railway journey from Brussels, passing through Flemish territory, he had heard announcements only in French. His denunciation of the general retreat of Flemish before the hegemonic French language was a fervent endorsement for the emerging Flemish movement; though possibly it was also somewhat embarrassing.20

Hoffmann did not only feel solidarity with a marginalized language; as a nationalistic German, he felt a proprietorial paternalism towards it and wanted to place the small sister language under the protection and tutelage of the older brother. If Belgium wanted to have a bilingual regime with a metropolitan language alongside the local Flemish, he asked, why then should that metropolitan language be the alien French? Why should it not be, rather, the more closely related and more easily understood German? And he continues, in a remarkable mash-up of different variants of ‘German’ and Netherlandic:

Fleminglandish is a Niederdeutsch language and conveys just like Plattdeutsch a familiarity and understanding of High German (Hochdeutsch). If German Belgium were to give up its own language and literature, then the High German language would have a more natural, and therefore more justified claim than that non-German, French language. If at some future date the educated classes of German Belgium were to speak and write High German, and to that extent take part in the German-language literary production, then this would not be a great marvel, any more than that ever since the sixteenth century the Nether-Germans in Germany’s northern lands (the lower Rhine, Westphalia, Lower Saxony and on the hither shores of the Baltic Sea) speak and write High German, and add their intellectual cooperation to German literature as much as the inhabitants of the regions where Upland-German (Oberdeutsch) is spoken, even though Niederdeutsch has remained their native tongue.21

This tendency to fold the Low Countries into a greater German whole played itself out in other fields than mere linguistic confusion. Hoffmann had, indeed, looked on the Low Countries with an acquisitively greater-German eye since 1820; and he was the poet who in his ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ had proclaimed that his aspirational, beloved Germany should stretch ‘from the Meuse [i.e. Namur-Liège] to the Niemen [Königsberg], from the Belt [Kiel, Schleswig] to the Adige [southern Tyrol]’. That was put forward as a programme of popular unification and emancipation; but it also implied territorial expansionism at the cost of neighbouring states and linguistically mixed populations. In the event, the association with greater-German nationalism was to prove a mixed blessing for the Flemish movement. German nationalists supported Flanders as a bulwark against encroaching French culture and repeatedly (in 1848, and fatally in 1914 and 1940) made the Flemish cause their own. This meant that after 1918, Flemish activism was tainted with the notion of uncivically betraying, with the aid of the German military occupiers, their country, Belgium; and ever since 1944, the Flemish movement has carried the guilty burden of its wartime sympathy, and widespread collaboration, with the Nazis.22

There was one great irony in this. What Willems and Hoffman found in the Elnon manuscript in Valenciennes was not just the most ancient contemporary copy of a vernacular German poem but also the most ancient contemporary copy of a vernacular French poem: on the same page as the ‘Ludwigslied’, and written in the same hand, is the ancient French ‘Hymn to Saint Eulalie’. The nearby monastery of St Amand, where the manuscript was produced and was kept until the French Revolution, had been founded in Merovingian times in the transition zone between the German-speaking and the Latinizing branches of the Frankish tribes. At that period and in that area, proto-German and proto-French coexisted and intermingled. Their peaceful literary coexistence in this ninth-century manuscript is a quiet reproach to the growing national chauvinism of the nineteenth-century philologists. A century after the manuscript’s discovery, its home region, between Ghent and Valenciennes, was torn up by the French–German gash of the Western Front.

Contested Heritage

In providing the modern nation with its ‘own’ cultural heritage, the past was not so much rediscovered as reappropriated. That reappropriation was to a large extent anachronistic, since the materials claimed as a national heritage themselves dated from a prenational (feudal or even tribal) past. That one should feel proprietorial towards one’s heritage is to a certain extent understandable. Modern countries such as England and Egypt may cherish and feel stakeholders in the ancient monuments located on their soil, such as Stonehenge and the Pyramids of Giza; in that privileged sense of being uniquely associated with them it matters little that the builders of those monuments had no familiarity with the country’s modern inhabitants. But the literary heritage presented a problem. Manuscripts as ‘portable monuments’ were transnationally dispersed across libraries and discovered by a roaming band of philologists; and they were written in idioms that were the forerunners of a palette of various modern languages current in different countries.23 As a result, they could become contested among different appropriations. The successor traditions to these medieval texts had fanned out into groups of different nationalities, each of which felt that they, and they more than any other, were the true heirs.

Thus Thorkelin thought that the Beowulf text he had discovered was a Danish poem, for the action is located along the Saxon coastlands that were Danish territory around 1800; nearby coastal tribes that the poem mentions are the Frisians, Angles and Geats, all of them known to Danish antiquarians. Small wonder that Thorkelin presented Beowulf as ‘a Danish poem in the Anglo-Saxon dialect’. Beowulf was thereby placed under a double mortgage: a scholarly one (since Thorkelin’s version was error-ridden) and a political one (in that the text was claimed by German, Danish and English scholars as culturally theirs). It took decades of debate for the English view to become dominant: that the Angles and Saxons, having migrated across the North Sea, had become the tribal ancestors of England, and that Beowulf was an Old English poem recalling events from before the Anglo-Saxon migration. That debate was further muddied by German philologists who argued that, since the Saxons were a German tribe, this was in fact a German poem casting light on the mores of the Saxon contemporaries of Charlemagne. In 1839 and 1859, editions appeared calling Beowulf Das älteste deutsche, in angelsächsischer Mundart erhaltene Heldengedicht and Das älteste deutsche Epos. The subtitle of the 1839 edition (by Heinrich Leo) offers full disclosure as to its approach: ‘The most ancient German heroic poem, in the Anglo-Saxon dialect, considered in its contents and in its relations to history and mythology: A contribution to the history of the ancient German mentality’. The preface to the 1859 edition (by Karl Simrock, a Grimm adept) voiced sentiments such as this: ‘As has already been pointed out, the Beowulf, though handed down in Anglo-Saxon, is in its foundations a German poem. In addition, the following comments clarify that its plot-line (Mythus) is a German one, which has left many traces amongst us. All this increased my wish to reappropriate this poem into our language.’ Simrock hopes ‘to bridge a thousand-year old division and to renew for this poem, that emigrated away along with the Angles and Saxons, its native domicile [Heimatrecht] amongst us.’ It is no coincidence that these editions appeared at a time when a strenuous German–Danish struggle was underway over ownership of Schleswig-Holstein – including precisely the coastlands where Beowulf was set.24

Within England, the assertion of Beowulf’s Englishness did much to strengthen a sense of Anglo-Saxon roots, rejecting the country’s other cultural source traditions – Celtic and Norman French. The marriage of Victoria, from the Hanover dynasty, to Albert, Prince of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, symbolically enshrined this sense of Saxon–Germanic affinity at the apex of society. Intellectuals such as Carlyle vociferously expressed a ‘Saxonism’ that dominated the mid-century. It was even projected across the Atlantic Ocean, where the ideal type of the WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) shored up the ideology of manifest destiny and a sense of a westward-expanding Anglo-Saxon world empire. The echoes of that ideology would inform Winston Churchill’s notion of the north Atlantic community of ‘English-speaking peoples’.25

The effect of these contesting appropriations in fanning national rivalries and national chauvinism is shown best by the most protean literary heirloom of them all: the satirical fables around Reynard, the canny, Machiavellian fox, who outwits the tooth-and-claw aggression of Isengrim the Wolf, the lumbering overbearing bearishness of Bruin the Bear, and the harsh arrogance of Noble the Lion, reigning monarch of the animal kingdom. The poem was known from early modern popular ‘chapbook’ printings in Dutch, in Low German and in English, and wily foxes were widely proverbial and featured in the fables of La Fontaine. The fables’ literary standing had been raised by Goethe’s new verse rendition, Reineke Fuchs, and French antiquarians had published early French versions – possibly the very oldest ones. It looked as if the French version was the original one, from which later versions had branched off.26

But when a young Jacob Grimm in 1805 was on a bibliographical mission to the French National Library (as an assistant to his mentor, the legal scholar Savigny), he could not help wondering at the fact that even in these oldest French versions, the animal’s names tended to sound German: Isengrim, Reynard’s wife Hersinde, even Reynard himself, the sarcastically named ‘Reinhart’ (pure-heart). And so Grimm began to hunt for the occulted Germanic roots of this Roman de Renard (much as Simrock would later discern Beowulf’s fundamentally German Mythus underneath the Anglo-Saxon language). His hunch was that there had been a lost prototype somewhere in the Flemish–French borderlands (where the tale is set, and where Hoffmann von Fallersleben and Willems would, thirty years later, find the German–French Elnon manuscript). He began to ply Dutch colleagues at Leiden with requests for information. Shortly after, the library of Comburg Abbey was transferred to Stuttgart, and in the process a manuscript was found that contained a previously unknown early Flemish version of the Reynard fable.

Grimm’s fox-hunt would last almost thirty years; only in 1834 did he bring out his majestic text edition Reinhart Fuchs, with a 200-page introduction to the High German text (discovered by Gloeckle and Görres in the Vatican Library) and other versions discovered in the former monastic library of Comburg, the former episcopal library of Kolocza, and elsewhere. It was a feisty assertion of the seniority of the German Reinhart over the French Renard. The French staked their claim with Dominique Martin Méon’s Roman de Renard (1826), followed by Paulin Paris’s Les aventures du maître Renard of 1861. The fox-hunt turned into a trench war.

That battle was also between two modes of editing ancient texts, ‘diplomatic’ or ‘critical’. The French editions were ‘diplomatic’ in that they based themselves on the best and most ancient available manuscript, noting marginally how other versions diverged from it; and this played out in favour of French seniority. Grimm’s way of editing was, however, ‘critical’, something he had learned from the renowned classical philologist Karl Lachmann. This method compared the available versions on the basis of their mutual resemblances and differences and schematized these variants into a type of ‘family tree’ of forking paths, known technically by the Latin term stemma. The stemma guided the philologist back towards the common root of all these diverging branches, an Urtext or underlying text-type that, while it might not have been expressed as such in any single version, formed the best starting-point for them all. And as it happened, the Urtext or Mythus for Reynard and Beowulf would turn out to be German (or Germanic, which for Grimm and his adepts – Hoffmann, Simrock – amounted to much the same thing).27

The choice between diplomatic or critical editing was also generational: the diplomatic mode harked back to the antiquarian tradition, while the critical mode was philological. And in the French–German philological bickering, it also became nationalized. The French denounced the obscurantist flim-flam of the German X-ray approach to texts; the Germans denounced the facile and superficial French obsession with appearances. The reader may discern here, once again, the ethnotypes that suffused the war propaganda of Thomas Mann (Chapter 2). Even scholarly method became an expression of national character and of national incompatibilities.

Over the century, the Franco-German appropriation war ground on. One edition followed another, and contemporary national values were projected onto the medieval material itself. Reynard himself was fitted into the prevailing ethnotypes. For the French, Renard was a nimble, sardonic charmer full of Gallic wit, and the episodes involving gross or obscene acts had all been added to the charming French original by vulgar German elaborators with their coarse sense of harsh, low-comic pranks. For Grimm, Reinhart was a moralistic Frankish animal epic harking back to the prehistorical days of tribal-totemic belief in animal magic, and the gross or obscene episodes had been spliced into it by oh-là-là French pornographers, frivolous and immoral as the French are known to be.

The tendency of philological traditions to fission along national lines is illustrated by the mid-century epistolary networks of Ernst Moritz Arndt (for most of his life professor at Bonn) and the Paris-based writer and inspector of antiquities Prosper Mérimée (some 4,000 letters in all, Figure 4.5); both were contemporaries of Grimm. Arndt’s network faces north-east, while that of Mérimée faces south-west. Between Paris and Bonn there is a dead zone of non-communication, running from London and Valenciennes/Saint-Amand-les-Eaux (where the Elnon manuscript had been written) to Venice, in an uncanny foreshadowing of the Western Front in 1914–1918.

Figure 4.5 The differently oriented correspondence networks of Ernst Moritz Arndt and Prosper Mérimée.

In this ‘ground zero’, Flanders, a very early Reynard version was discovered, written in, of all languages, Latin. But that did nothing to defuse the terms in which the contesting appropriations were now fought. Grimm kept on questing for older Netherlandic-Germanic versions antedating the ones that were coming to light. In 1830, though, when Flanders seceded from the Netherlands, he gave up hope; for the new state, Belgium, exhibited a strong affinity with France. Grimm (a cantankerous character at the best of times) voiced bitter resentment towards the stolid indifference of the Dutch and the traitorous francophilia of the Catholic Flemings, which now seemed to preclude any possible discovery of a Flemish Ur-Reynard. In a review of 1830 he vented his spleen at the Belgian secession:

The Catholic, formerly Spanish, then Austrian Netherlands offer a warning example of how the neglect of the native language weakens all love of the fatherland. Any nation that surrenders the language of its ancestors is degenerate and without firm footing. The present revolution in the Netherlands cannot be attributed to a properly patriotic movement but merely reflects the long-established influence of French manners and the plotting of priests. Common folk from Antwerp to Brussels and Ghent still speak Netherlandic. The almost-extinct nationality of the Belgians might have been rekindled by closer ties with Holland; but the tremendous torrent of events now threatens to sweep away all that remains of it.28

These reproaches were later to be quoted by none other than Jan Frans Willems when he edited his Flemish Reynard in 1836, praising the fox fable as the crown jewel of Netherlandic literature and denouncing its obscurity as a standing reproach to the hegemony of French in Belgium. That edition, of the long-lost Flemish version, presented a double irony. Grimm’s own Reinhart Fuchs, appearing after thirty years of painstaking preparation in 1834, proved to be still premature; for in 1835, that selfsame Belgium that Grimm had accused of a lack of true patriotism had acquired an important manuscript from the estate of a British bibliophile, which contained, among other foundational Flemish texts, the long-sought-after Reynaert. The boost that this gave to Flemish self-esteem in the new Belgium can be imagined; and Grimm embraced Willems as the long-sought philological soulmate and his fellow worker in the Low Countries. Willems died soon after Hoffmann von Fallersleben’s visit, however, and Grimm dedicated a heartfelt eulogy to this absent friend when he opened the Germanisten Congress in 1846.29

Reynaert has ever since remained a trump card in the Flemish rejection of francophone dominance in Belgium, and the character attributed to him here was again a projection of a national self-image. Reynard as framed in Flemish terms is beset by many authoritarian figures claiming dominance over him; unable to challenge their brute force, Reynard instead uses his wiles as a trickster to outwit them. The fox continued to be all things to all nations competing for his appropriation.

The Nation Goes Epic

These foundational texts have all become hyper-canonical. Beowulf, the Chanson de Roland, the Nibelungenlied, Reynaert, the Lay of Prince Igor’s Campaign: they take pride of place in the opening chapters of national literary history books and anthologies, they form part of national school curricula and they have, in the root sense of the word, been canonized as being foundational to their nations’ cultural-historical presence.

The hallmark of canonicity is the fact that a text is regularly adapted and recycled into different updated retellings, often in different genres or media (‘remediation’). The public cannot, literally, get enough of it, and besides the many reprints and new editions (spurred on by professional rivalry between ‘diplomatic’ and ‘critical’ editors and by the discovery of additional manuscript fragments), there were numerous literary spin-offs: retellings in contemporary language for the general public or for juvenile readers; or adaptations as stage plays, as operas, as novels and, in the twentieth century, as films and graphic novels. Britain rediscovered King Arthur, King Alfred and Queen Boudicca. In post-1870s France, Sarah Bernhardt starred in a patriotic theatre play, La fille de Roland; in Germany, the Nibelungen generated some forty poetic and theatrical adaptations, culminating, of course, in Richard Wagner’s operatic Ring cycle; in 1916 a volume of propagandistic war poetry was published under the title Nibelungentreue: Kriegsgesänge, signalling a robust politicization of the epic for nationalistic and militaristic purposes.30

It was in the nineteenth century that the notion of a ‘national epic’ became current; previously, epics such as the Iliad had been seen as simply classical and nationally unspecific. By the 1840s, it became commonplace to see each literary tradition begin with an epic foundation. Goethe had wryly pointed this out: ‘Each nation owes it to its self-esteem to possess its own epic’. As the Oxford English Dictionary (1933 edition, under ‘Epic’) puts it:

The typical epics, the Homeric poems, the Nibelungenlied, etc., have often been regarded as embodying a nation’s conception of its own past history, or of the events in that history which it finds most worthy of remembrance. Hence by some writers the phrase national epic has been applied to any imaginative work (whatever its form) which is considered to fulfil this function.

For Jacob Grimm, the peculiar power of the epic was that it makes no concessions to the modern reader, forcing that reader into mental time-travel to the days of yore:

Lyrical poetry, arising as it does out of the human heart itself, turns directly to our feelings and is understood from all periods in all periods; and dramatic poetry attempts to translate the past into the frame of reference, the language almost, of the present, and cannot fail to impress us when it succeeds. But the case is far different with epic poetry. Born in the past, it reaches over to us from this past, without abandoning its proper nature; and if we want to savour it, we must project ourselves into wholly vanished conditions.31

‘Projecting oneself into wholly vanished conditions’ (uns in ganz geschwundene umstände versetzen) – that imaginative time-travel into the past and directly experiencing it as it must have felt at the time: that may provide us with a pithy definition of historicism, which the rediscovery of epic did much to engender. The remediations and adaptations should also be understood, then, as bridges across the historical gap between the epic Then and the national Now.

It is still a sobering surprise to realize that these national epics had dropped out of cultural memory more or less completely for so many centuries and that their currency as texts was achieved largely in the post-Napoleonic decades. The presentations of the oldest texts in the national canons are mostly a product of, or at least initially marketed as part of, the Romantic movement; and the philological bookworms were as much part of that Romantic movement as the idealistic poets.

Those poets did their nationally epic thing, too – Romanticism wasn’t exclusively about the lyrical intuition of Higher Things, it was also about the epic evocation of Olden Things. Foundational epics were freshly composed as part of a Romantic-national literary agenda. In many cases, these newly written epics originate in nations experiencing an existential crisis. Jan Frederik Helmers’s De Hollandsche Natie (1812) dates from the Netherlands’ Napoleonic occupation and annexation. In Sweden, the national poetry of Esaias Tegnér was fed by regrets about that country’s loss of its Finnish possessions (Svea, 1811; Frithiof’s Saga, 1825). Similarly, there are various mythical and historical plays and poems by the Danish national poet Adam Gottlob Oehlenschläger, starting with Vaulundur’s Saga (1805) and culminating in the heroic-epic poem Hrolf Krake of 1828. As in the Dutch case of Helmers, Oehlenschläger’s work reflects a nation with a great past sinking to second-rank status: Denmark lost its Norwegian dominions after Waterloo and saw Schleswig-Holstein threatened by an increasingly powerful German neighbour.

Whereas Dutch, Swedish and Danish were the established official languages of long-standing sovereign states, national epics were to become particularly popular in languages newly emerging as literary vehicles, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe. In a number of emerging literatures, in languages until then seen as uncouth dialects, poets were inspired by these discoveries and by the taste of literary historicism to become their nations’ Homers. The Slovak language, overshadowed on all sides (in Bohemia by Czech and German, in Hungary by Magyar), declared its presence in the epic poems of Jan Hollí (Svatopluk, 1833; Cirillo-Metodiada, 1835).Footnote * Jan Kollár, another Slovak, though writing in Czech, produced the remarkable sonnet cycle Slavy dcera (‘The Daughter of the Goddess Slava’, 1824), which has formed a national-Romantic inspiration to all Slavic languages and literatures.

For the Hungarian, Polish, Slovene and Ukrainian languages, likewise at that moment outside the repertoire of established literary praxis, the verse epics Zalan futása (‘Zalan’s Flight’, 1823, by Mihaly Vörösmarty), Konrad Wallenrod (1828, by Adam Mickiewicz), Krst pri Savici (‘The Baptism on the River Savica’, 1836, by France Prešeren) and Hajdamaky (‘The Outlaws’, 1841, by Taras Shevchenko) became the very foundation of subsequent national literatures. What is more, they were written as such. The very choice of a marginalized minority language for an ambitious and extensive heroic poem is in each of these cases already a blatant cultural–political signal. They were national both in theme and in ambition – in that the poet dealt with a foundational episode in the nation’s early history. The case of Prešeren’s Baptism on the Savica may stand for the others: it deals with the Slovenes’ transition from ancient paganism to Christianity. (Figures straddling the transition from tribal paganism to Christianity were a favourite Romantic theme: the Gaulish princess Norma in Bellini’s 1831 opera; the Lithuanian Princess Birutė; the Batavian maiden Hermingard in Aarnout Drost’s 1832 novel.) Prešeren’s poem describes the defeat of the last pagan chieftain at the hand of the Christian armies and his discovery that his even his beloved has become a Christian; written in the metre of Slovene folksong, the poem traces a crucial and tragically dignified moment of transition in the nation’s collective history. It is this quality that gives it its epic character. In turn, this epic scale has ensured for the poet (a cosmopolitan intellectual, whose literary sensibility resembles Heine’s ironic Weltschmerz more than Macpherson’s sublime sentimentalism) his stature as the founding father of his country’s national literature. Prešeren’s statue is prominent in the central square of Slovenia’s capital Ljubljana.

In this process, the epic slipped its antiquarian moorings in the ‘manuscript found in an attic’ mode. Indeed, not all nationalities in Europe had manuscript-stocked attics, or ancient libraries or archives with dormant primordial texts. What they had instead was a thriving oral-performative culture, and alongside the national epic rose the oral epic. That will be the topic of Chapter 5.