In March 2000 the archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey, dedicated, in the presence of Queen Elizabeth II, the long-promised national Home Front Memorial in the ruins of Coventry Cathedral (Figure 1). His speech was centered around the “three Rs” of postwar Coventry: resilience, resurrection, and, above all, reconciliation. Carey stressed the crucial support Coventry Cathedral was providing to the then-ongoing restoration of the Frauenkirche (Church of our Lady) in Dresden.Footnote 1 Here was a tangible example of reconciliation in action: between two Christian confessions, two churches, two cities, and two countries. At the time of the archbishop's speech, Coventry Cathedral and the Frauenkirche were often mentioned in one breath. Clergy(wo)men, journalists, politicians, and historical preservationists alike considered them architectural and moral equivalents, corresponding symbols of annihilation and atonement, of ruination and resurrection. However, during the first forty-five years after the war, no one saw the parallel—because there wasn't any. For decades after 1945, the ruins of the Frauenkirche were neither a revered shrine nor an unintentional monument, but simply a gutted structure suspended in limbo. The idea that the Frauenkirche ruins “quickly became the foremost site of commemorating German victimhood”—a claim frequently encountered in the scholarly literature—is based on a misreading of the ruins.Footnote 2 To be sure, reading ruins is a tricky undertaking, for they are “both over- and underdetermined,” as the poet and critic Susan Stewart puts it aptly. “They stand poised between the forms they were and the formlessness to which, in the absence of restoration, they are destined.”Footnote 3

Figure 1. Home Front Memorial, Coventry Cathedral, 2000. Author's photograph, 2008.

This article explores the contrasting, and connected, stories of the (overdetermined) ruins of Coventry Cathedral and the (underdetermined) remnants of the Frauenkirche between 1940 and 2010. The rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral was a—perhaps the—landmark project of postwar Britain, one that has attracted some attention from architectural, ecclesiastical, urban, visual, and even musical historians. We know quite a bit about Basil Spence's thoughtful architecture, John Piper's brightly colored baptistry window, Graham Sutherland's imposing altar tapestry, Benjamin Britten's haunting War Requiem, and the cathedral clergy's innovative theology of society.Footnote 4 This research has shed important light on the artistic and theological ideas behind the new building as well as its festive inauguration; yet little is known about the ruins that, to this day, form an integral part of not only the architectural ensemble but also the liturgical life of the cathedral. Similarly, the memorial function of the gutted Frauenkirche has often been assumed rather than examined. The lack of scholarly attention to what are, arguably, two of the most famous war ruins in the world is surprising, given that scholars of various backgrounds have researched the conversion of local church ruins into war memorials after the Second World War.Footnote 5

Across postwar Europe, thirty-two war-damaged churches were converted into war memorials (although a similar number were retained without a specific memorial function). The reasons for keeping bombed churches were symbolic and pragmatic, and, as we will see, part of a wider turn away from established forms of memorialization. Geographically, church memorial ruins were concentrated in Western Europe, notably in Britain (seventeen in total) and West Germany (ten). To be sure, many of these sites of memory have not fared well since then, as planning historian Peter J. Larkham has recently discovered. Today the vast majority are barely visited, improperly signposted, and difficult to access; one has even been converted for business and residential use.Footnote 6 The towering exception is Coventry Cathedral, not simply because it was, and continues to be, a still-functioning place of worship but above all, I will argue, because of its global significance. The cathedral's ruins have been key to the message of reconciliation, internationally and interdenominationally. Unlike other church ruins, they are not merely a symbol, a static “site of memory” frozen in time but a dynamic lieu de mémoire, a workshop, where memories of a destructive past were harnessed to a vision for a peaceful future and Christian unity.Footnote 7

This article charts the evolving meaning of this British cathedral's ruins in their global context. In particular, it highlights connections and contrasts between Coventry Cathedral and the Dresden Frauenkirche. Using a comparative and transnational approach, the article fuses memory studies with church/architectural history. In doing so, it pays close attention to the imbrications of material remains, public discourses, signifying practices, and administrative actions. The article begins with a discussion of the historical background, that is, the rejection of memorial ruins after the Great War and their propagation in Britain after the Second World War. It then explores the meaning of the ruins of Coventry Cathedral in the first two decades after the war as well as subsequent attempts to “update” them (and broaden the cathedral's international mission) through artistic interventions and additional memorials. Finally, the article demonstrates that the Frauenkirche ruins were a belated and ambiguous memorial, and that the pairing of Coventry Cathedral and the Dresden church happened only in the aftermath of German reunification.

Bombed Churches as War Memorials? From the Great War to the Second World War

A fascination with ruins in general and ruined ecclesiastical buildings in particular long predated the Second World War, harking back at least to romanticism in the early nineteenth century. But to understand the attraction of bombed churches as war memorials after 1945, one has to begin with the legacy of the Great War (itself, of course, shaped by a long tradition of ruin-gazing).Footnote 8 The dynamic of destruction unleashed in the First World War had left behind a scene of cultural devastation. The war-gutted city of Ypres, with its ghostly ruins of medieval buildings, acquired a special poignancy for the British and Dominion forces. In this context, there emerged the idea of the ruin as a witness to destruction and survival, violence and endurance—“as a witness to something beyond itself,” as Thomas W. Laqueur has phrased it.Footnote 9 In 1919 the then secretary of state for war, Winston Churchill, proposed acquiring the ruins of the Flemish city as a permanent memorial to the sacrifices of the British Empire—an idea both original and outrageous, and one that did not go down well with the local population, keen to return and rebuild.Footnote 10 Everywhere along the former Western Front, reconstruction was the order of the day. Rebuilding was a practical necessity mediated by moral propaganda, a celebration of victory and a demonstration of perseverance. The cathedrals of Ypres, St. Quentin, and Rheims became symbols of national recovery from the dynamic of cultural destruction. Rheims Cathedral, the site of coronation of French kings, was without doubt the most prominent architectural loss of the Great War. The rebuilding of this most significant of French cathedrals was an act of defiance, and also revenge. Its restoration was celebrated as the ultimate triumph of French civilization over German Kultur, a reversal of the “strategic historicide.”Footnote 11 Thus, significant resources—economic and emotional—were invested into the reconstruction of war-damaged churches. Commemorative ruins simply did not fit into this architectural program of reversed ruination. Churchill's vision of ruins-turned-memorials was an idea ahead of its time.

If the “Great War ruined the idea of ruins,” as Geoff Dyer has put it (a bit too emphatically), then the Second World War restored it.Footnote 12 The painter John Piper, sent on an official mission to Coventry in the immediate aftermath of the air raid of 14 November 1940, was among the first to discern or rediscover what he called the “picturesque” in the ruinous landscape.Footnote 13 Like all official war art, Piper's paintings of Coventry, especially of the destroyed cathedral, were commissioned as propaganda but intended for posterity—war memorials in oil and gouache. The bombing war gave the British people an intimate knowledge of ruins, and yet the idea of not only visually recording but also physically preserving them seemed to some, mainly intellectuals, an attractive proposition. In 1944 a group of public figures, including the art historian (and chairman of the Ministry of Information's War Artists Advisory Committee) Kenneth Clark, the poet T. S. Eliot, and the economist John Maynard Keynes, lobbied for the conservation of bombed churches, specifically churches in the City of London built by Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of 1666. They feared, quite rightly as it turned out, that once the war had ended the need to revive the metropolis and return to business as usual (especially in London's financial district) might be greater than the impetus to memorialize the wartime past. Arguing that the monuments erected after the Great War had been “unworthy” of the fallen soldiers and that, in any case, total war had rendered traditional war memorials inadequate, they doubted that there could be “a more appropriate memorial to the nation's crisis than the preservation of fragments of its battleground.”Footnote 14 What they had in mind, though, were not stark ruins and raw reality but beautified structures, serene garden sanctuaries offering vaguely religious “spiritual refreshment” and mental relaxation—memorial sites that were both sacred and utilitarian.Footnote 15 These (un)natural ruins were choreographed landscapes, discreetly curated to resist further decay—contemporary versions of Fountains Abbey or Raglan Castle rather than memorials of a frozen apocalypse. Proponents of this idea were also anxious to stress that bombed churches were reminders of “sacrifice” (a term that now encompassed soldiers and civilians), and certainly not symbols of “vengeful memory.”Footnote 16

The garden ruins scheme had the backing of the dean of St. Paul's Cathedral, London, that carefully crafted icon of miraculous survival. Having escaped largely unscathed from the blitz, St. Paul's—the almost-ruin—was widely touted in the late 1940s as the site of the new national war memorial. The blitzed area around the cathedral, it was suggested, could be turned into a memorial garden, complete with a flower-covered ruin, ready in time for the Festival of Britain in 1951.Footnote 17 Paradoxically, the war “rescued” the dilapidated cathedral church of London, which before 1940 had become a national liability. While St. Paul's was already a world-famous building, Coventry Cathedral was a regional landmark thrust into the global spotlight by the war.Footnote 18 It was the bombing that transformed the former parish church into a national treasure and an international symbol. Ruination effectively enhanced the status of St. Michael's, elevated to cathedral status only in 1918. Here was a tragic-heroic story set in space and time, recognized United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt, when in 1942 he declared the wrecked cathedral one of the “proudest monuments to British heroism.”Footnote 19 Seeking to exploit this newfound fame, the bishop floated the idea of offering the cathedral to the government as a “Civil Defence memorial,” that is, “a national memorial to those who died from enemy air raids over Britain.”Footnote 20 He and the cathedral clergy had, of course, no intention of relinquishing control over the ruins, but they hoped to convince the government to shoulder the burden of maintaining them (and financing the rebuilding of the new cathedral). In the end, nothing came of this. In fact, the whole scheme of a national memorial, although widely discussed, was stillborn.

One of the reasons for this failure was a fundamental disagreement about what form the national memorial (and new memorials generally) should take. The idea of combining war memorialization with urban beautification struck a responsive chord with many, but also drew critics. Among the most formidable was Herbert Baker, a former principal architect of the Imperial War Graves Commission. He questioned whether ruins could derive their commemorative power from their materiality alone. Calling himself an “architect of living buildings” (even though, for many, his name was synonymous with war cemeteries), he rejected “dead ruins,” unless it was possible to “reanimate” them, for instance through religious service.Footnote 21 In other words, the material narrative of ruins needed to be embedded in performative practice and connected to religious thought. That was exactly what they did at Coventry. The bombed-out shell of the cathedral continued to be used on special occasions during the war. Notably, the enthronement of the new bishop, Neville Gorton, in the rubble-strewn, roofless ruins in 1943 sent a powerful signal: an assertion of continuity in an era of catastrophe, a celebration of renewal after ruination.Footnote 22 After the end of the war, the remaining rubble was removed, a lawn planted, and a neat gravel path laid, creating a more sanitized environment.Footnote 23

Symbol of Forgiveness, Site of Reconciliation: The Coventry Cathedral Ruins, 1940–64

The ruins, Provost Richard Howard reflected in 1947, “have been exceedingly impressive and have spoken to tens of thousands with a message that is beyond words.”Footnote 24 Yet a wordless token, a mute witness to sacrilege, would not suffice. The cathedral clergy were determined to fill the semantic void with positive meaning—meaning derived from the theology of atonement, forgiveness, and reconciliation.Footnote 25 Initially, though, the ruins appeared to stand in the way of this endeavor. “It is a wrong and debilitating sentiment to want to perpetuate a ruin,” a publicity brochure of 1945 stated, adding that, “It is more noble and energising to rebuild as a symbol of triumph over evil.”Footnote 26 Thus, the original plan foresaw the demolition of most of the ruins, except for the spire (which miraculously had escaped serious damage), in order to make space for the new cathedral. For the architect Basil Spence, however, retaining the ruins and rebuilding the cathedral were not contradictions. On the contrary, Spence believed that the new cathedral “should grow out of the old Cathedral and be incomplete without it.”Footnote 27 The architect's plan did not fail to impress the critics. A stone trades journal called the finished building (consecrated in 1962) a “magnificent war memorial,” while The Builder echoed and expanded on Spence's words:

22 years have passed since the old cathedral church was burnt out in the savage air raids which took place during the night of November 14, 1940, the tower and scarred outer walls only surviving. Yet out of this holocaust has risen a new national monument and place of pilgrimage from all over Europe and indeed the world—a building which, in the manner of its inception, design and execution, epitomises the spirit of religious resurgence in England today.Footnote 28

Spence considered the destroyed cathedral an “eloquent memorial to the courage of the people of Coventry” that should be allowed to stand as a “garden of rest.”Footnote 29 While taking inspiration from the garden ruins scheme, he sought to go beyond it. Architecturally, the vestiges of the medieval church form an atrium to the new cathedral—an ensemble suggestive of sacrifice and resurrection—while, liturgically, the ruins remained an integral part of religious observance.Footnote 30 Here, the cathedral congregation recites weekly the Coventry “Litany of Reconciliation.” Prayers and services conducted in the ruins are centered around three symbols: the altar of rubble, the Charred Cross, and the Cross of Nails (Figure 2). All three were fashioned from remnants from the old church and positioned in the ruined apse. The words “FATHER FORGIVE” (Luke 23:34) are carved into the stonework, but significantly omitting “THEM,” for the cathedral clergy believed that all were sinners, and all needed to be saved.

Figure 2. Charred Cross and altar of rubble, Coventry Cathedral, 1940. Author's photograph, 2008.

The story behind the making of the Charred Cross is particularly illuminating. The morning after the bombing of Coventry on 14 November 1940, so the story goes, Jock Forbes, the stonemason and caretaker of the cathedral, came to inspect the damage. Spontaneously, Forbes picked up two huge wooden beams, scorched by the fire of the incendiary bombs, and fastened them into the shape of a cross, the symbol of Christian sacrifice and redemption. This he planted on a mound of rubble. A devout Roman Catholic but unlearned in theology, Forbes did a simple yet profound thing, transforming the debris into a Calvary—not quite a miracle story but not far from it either.Footnote 31 A lingering iconophobia among Anglicans notwithstanding, the makeshift cross soon became recognized as a precious relic. It offered little by way of aesthetic redemption, but it contained the rudiments of hope: “It is an ugly cross, let us not pretend that it is not, but it has in its ugliness the beauty of hope, the quality of love and the serenity of forgiveness.”Footnote 32 When, shortly after the war, Provost Howard invited the German pastor Adolf Kurtz to visit Coventry, they knelt and prayed together before the Charred Cross. Like many Anglican churchmen, Howard believed in the existence of “the other Germany,” a land supposedly inhabited by good Protestants—people such as Kurtz, who had been a member of the anti-Nazi Confessing Church during the Third Reich. Pastor Kurtz, too, understood the Charred Cross as “a symbol of Christian Unity and Brotherhood which even Hitler's war was unable to destroy.”Footnote 33 The German visitor experienced the ruins as a site, and the Charred Cross as a token, of reconciliation both internationally and inter-denominationally. The Charred Cross marked a complete departure from the patriotically inflected commemorative art and culture—the patri-passionism—of the interwar era, during which the monumental cross had undergone a massive revival. Here, there was no attempt to convert death into a gift, and to create a spiritual aura around the dead, the war, and commemoration itself.Footnote 34

The Charred Cross performed a dual role. The symbol of a religious idea, on the one hand, it was a memorial (within a larger memorial space) to a historical event, on the other. On occasion tension arose between these two dimensions, between reconciliation and remembrance. The cathedral authorities had no interest in preserving a “frozen moment of destruction.”Footnote 35 Rather, they envisaged the ruins as a dynamic space, facilitating contemplation and communion, introspection and interaction. A hybrid space, the ruins served as a quotidian garden of rest, a place of weekly worship, and a venue for special events. While the cathedral clergy regarded the ruins as a symbolically charged space to be used, many locals considered them a hallowed monument to be revered.

In striking fashion these attitudes clashed in 1958. The dancer and choreographer Anton Dolin offered to stage a ballet performance in the ruins in aid of the new cathedral scheme. The performance was likely to attract widespread attention and fill the coffers of the reconstruction fund. Yet the cathedral authorities had underestimated the strength of local feeling. “Please let us keep it as holy ground and not desecrate it,” wrote a group of bereaved. “It is the only place where we can remember our loved ones.”Footnote 36 To be sure, the controversy was as much about modernism and modernity as it was about decorum and the dignity of memory, for people took particular exception to the idea of a modern ballet, which, they alleged, would “entirely destroy the sacred character of the ruins.”Footnote 37

The bishops and provosts of Coventry sought to imbue the ruins with positive meaning, using them as a platform to spread the evangelium, the good news, in Coventry and around the world. While the ruins were fixed in place—and the cathedral authorities unwilling to part with a single stone—the Charred Cross could be transplanted into other contexts.Footnote 38 In 1964 it was sent on a journey to the United States, where it formed part of the Protestant–Orthodox pavilion at the New York World's Fair. The initial proposal was to display the Charred Cross alongside Michelangelo's Pietà and the Dead Sea Scrolls. In contrast to the other star exhibits, the Charred Cross was neither an artistic piece nor a historical document, but “something with a deeper spiritual meaning.” Unafraid of hyperbole, H. C. N. “Bill” Williams (provost from 1958 to 1981) declared his cross “world famous,” maintaining that it “speaks more eloquently of the reconciliation and forgiveness, and hope of unity and peace, then any symbol that we know of anywhere in the world.”Footnote 39 He became extremely alarmed, then, when it transpired that the Charred Cross was to be exhibited not inside the pavilion itself but outdoors, next to a hot dog stand.Footnote 40 In the end, the cross was mounted on an altar in the pavilion's meditation garden, backed by a concrete wall on which were inscribed the words “Father Forgive.” There was nothing beautiful about this cross in either its original or its new setting, said the provost when presenting it in New York, but it “invites you to look human suffering and agony straight in the eye.”Footnote 41

Multidirectional Monuments: Pacifist Sculptures for Coventry and Hiroshima, 1968–2005

Although posited as a universal project, the cathedral's ministry of reconciliation betrayed a European or Western-centric bias. It reached out to Europeans, in particular Germans, and looked for moral and financial support from North Americans. New impulses came from the outside, in the shape of two sculptures intended for the ruins and their environs: an installation by the artist couple John Lennon and Yoko Ono in 1968 and a statue donated by the entrepreneur Richard Branson in 1995, both shifting the focus eastward. Yoko by John and John by Yoko was an unofficial contribution to a major sculpture show staged in the cathedral ruins in summer 1968. Attempting a late entry to the exhibition, Lennon and Ono planted two “acorns for peace” in the center of a circular white wrought-iron garden seat. Aligned in an east–west direction, the two trees were supposed to bridge the geographical and cultural divide between John and Yoko's ancestral homes. The couple's first public “peace action” left the organizers cold. “It's a beautiful thought […]—but it's not a sculpture.”Footnote 42 The installation was removed from view (allegedly on the advice of Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore) and replanted in the cathedral churchyard. Apparently, the outraged Lennon sent a private letter to the canon in charge of the exhibition, branding him hypocrite.Footnote 43 Thirty-seven years after this row, in 2005, Ono was invited back to Coventry to plant two Japanese oak trees—a memorial to the original installation (which was later stolen) and a gesture of reconciliation between the cathedral and the artists.Footnote 44

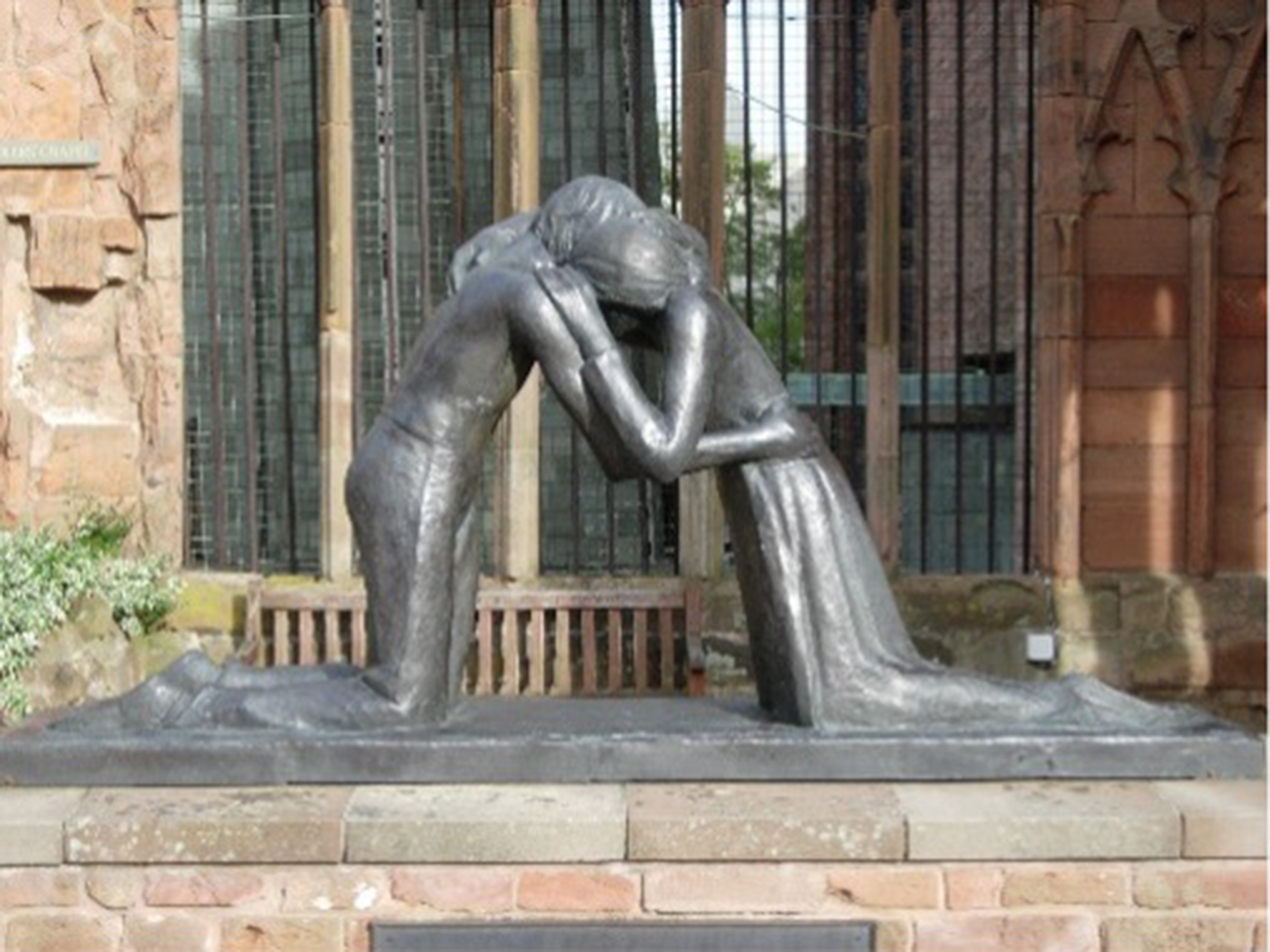

What exactly Lennon and Ono meant by “peace” and understanding between East and West remained nebulous. Did it entail soothing painful memories of the fall of Singapore and the Burma operation, the “forgotten” campaigns that for decades remained open wounds in Britain? Probably not. In the 1960s the time was not ripe for that.Footnote 45 It took a further twenty-five years and another outside intervention, again from a celebrity, for the war in East Asia to find a place (albeit a limited one) in the memoryscape of Coventry. In 1995 billionaire businessman Branson approached the cathedral with the offer of donating two identical statues cast in bronze, sculpted by the British artist Josefina de Vasconcellos (Figure 3): one to be placed in the ruins of Coventry Cathedral, the other in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Entitled Reconciliation, the statues represent a man and a woman embracing in consolation to “remind us that, in the face of destructive forces, human dignity and love will triumph over disaster and bring nations together in respect and peace.”Footnote 46 The decision to accept the donation caused a marked backlash, with both a local citizens’ group and national veterans’ associations protesting.Footnote 47 Individual ex-servicemen, too, sent sharp letters to Provost John Petty:

I don't know who authorised you to “reconcile” Japan's WW2 atrocities, I do know that no authorisation would have been given by the vast majority of British and Allied troops who fought in that terrible campaign, and let's face it, they are the only ones to decide this matter. Without their stance against superior odds and a brutal enemy you, Richard Branson, and all the conciliatory Uncle Tom Cobley's [sic] would not exsist [sic] to pontificate. Japan could have had “reconciliation” at any time during the last 50 years, all they had to do was apologise and compensate. Where was your voice urging them to do this?Footnote 48

Figure 3. Reconciliation by Josefina de Vasconcellos, Coventry Cathedral, 1995. Author's photograph, 2008.

The veteran raised an important question: who “owned” the memory of war? The provost conceded that “I come from a different generation” without personal experience of the horrors of the Second World War, but he deflected the broader question. His mission was reconciliation, not remembrance; he wanted to look forward, not backward. “It is for that generation and those who follow,” the provost told the veteran, “that we try to look to a lift of trust rather than bitterness between peoples.”Footnote 49

Branson, too, engaged directly with critics of the Reconciliation statue (for instance, a representative of the Burma Star Association), broadly echoing the provost's line.Footnote 50 A flamboyant businessman with a knack for public relations stunts, Branson has sometimes been accused of fake altruism. Yet the files in the archives reveal that he felt deeply about this issue (and that the cathedral had no reservations about the Branson brand). Certainly, Branson took the trouble to reply personally, even to rude letters. To be sure, not all veterans flatly rejected the twin memorials in Coventry and Hiroshima. The intervention by the president of the National Federation of Far East Prisoners of War Associations, although forceful, ended on a conciliatory note: “Mr Branson is an entrepreneur who would do better to look after his airline and his virgins. But I have to accept that freedom of expression is what we are fighting for.”Footnote 51 Crucial support came from the South African writer and guru Laurens van der Post. A former prisoner-of-war (who, incidentally, had also witnessed the bombing of Coventry), van der Post claimed the status of truth-teller about the past, and apostle for the present: “Forgiveness, my prison experience had taught me, was not mere religious sentimentality; it was as fundamental a law of the human spirit as the law of gravity.”Footnote 52

Provost Petty cited this passage, taken from van der Post's 1970 memoir The Night of the New Moon, at the unveiling of the Reconciliation statue in the ruins of Coventry Cathedral in August 1995.Footnote 53 While the preliminary discussions had brought up bad memories, the dedication ceremony sent out a positive message—namely that forgiveness and reconciliation were possible, and necessary, because nobody was innocent: “All have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God.”Footnote 54 Paul Oestreicher, the German-born canon who led the service in the ruins (broadcast on BBC Radio 4), took his theme from the New Testament (Romans 3:23). The sin that loomed largest on his mind, though, was the bombing of cities, above all the nuclear attack on Hiroshima. An Anglican priest, Quaker, and peace and human rights activist, Oestreicher foregrounded the suffering of the hibakusha, the victim-witnesses of the atomic bomb. By contrast, the story of captivity—of cruelty and exploitation—did not sit well with the spirit of the occasion. A religious act rather than a historical reckoning, the service of dedication presupposed an equivalence of suffering. Moreover, it imposed a specific interpretation on the Reconciliation statues that was reinforced by their respective settings. Erected in the ruins of Coventry Cathedral and in the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima, the twin figures memorialized the reconciliation between two iconic cities. For all the cultural differences, there are striking similarities between the cathedral ruins and the memorial park with the Atomic Bomb Dome: the architectural juxtaposition of ruination and rebuilding; the framing narrative of suffering and healing; and the symbolic tension between a universal message and historical specificity.Footnote 55

The pairing of Coventry and Hiroshima happened against a backdrop of the un-pairing of Hiroshima and Auschwitz in the 1990s. For over forty years, the Holocaust and the atomic bomb had been treated as commensurable events—a notion sustained by flows of ideas and people between the two discourses.Footnote 56 But now, as the Holocaust-centered memory boom was taking off, Hiroshima was in danger of becoming an irrelevance. The new intercontinental memorial alliance promised to reverse this trend, reassuring both partners of their global significance. The commemorative axis between Coventry and Hiroshima became a triangle in 1999, when a further copy of the Reconciliation statue was erected outside the Chapel of Reconciliation in Berlin. Placed adjacent to a very different ruin—fragments of the Berlin Wall—this statue recalls a totally different historical situation, namely, the Cold War in Europe, the division of Germany, and the shootings at the Berlin Wall. To complicate further the symbolism of Reconciliation, another cast was made for Stormont Castle in Belfast, in recognition of the Northern Ireland peace process.Footnote 57 This increasingly heterodox network of identical sculptures in different countries (all but one placed next to a ruin) was an early manifestation of “multidirectional memory,” a phenomenon associated with post- or second modernity. Memory takes a multidirectional turn, Michael Rothberg argues, when “remembrance cuts across and binds together diverse spatial, temporal and cultural sites.”Footnote 58

Given how scrupulously the cathedral authorities had guarded the ruins until then, it is surprising that they were even willing to contemplate an additional—multidirectional—monument in 1995. The original Lennon–Ono installation had been removed, largely because the cathedral clergy were not prepared to tolerate a high-profile supplementary memorial that might divert attention away from the Charred Cross and the ruins. Yet, in the 1990s, they began to accept more and more gifts, partly out of concern that without such modifications the ruins could deteriorate into a commemorative fossil. The most significant addition was the national Home Front Memorial, unveiled in 2000 (Figure 1). An inauspicious circular slab, it commemorated the “self-sacrifice of all those who served on the Home Front”—specifically, war workers and women volunteers—in the Second World War. The much-discussed but never-realized national memorial was finally taking shape, over fifty years after it had been mooted. When making the announcement that Coventry Cathedral was the site chosen for the new monument, Prime Minister Tony Blair stressed that the city had made “tremendous sacrifices during the Second World War to help defeat dictatorship in Europe.” Here, Blair effectively echoed wartime representations of the city's heroic suffering and resilience.Footnote 59 However, he was quick to add: “But it is also a city that embodies the spirit of reconciliation.”Footnote 60 In his unveiling speech, the archbishop of Canterbury pointed out that “This in fact is a service about service.” He was even more anxious than the prime minister to move on from remembrance to reconciliation, from self-sacrifice to service, and from the past to the future:

The Home Front story of Coventry though is not just of resilience and resistance, but also of resurrection. The post-war rise of this wonderful Cathedral, alongside the shattered remains of the old one, has become a symbol across the world. […]. But when we have honoured and sought to reconcile the past, what if anything should we carry into the future? What should it mean for the generations to whom this is not the stuff of experience but of history? Service, of course, has to be motivated. A war effort draws a beleaguered people together. Peace-time is a different matter. Neither the enemy nor the shared cause are so easily identifiable. So we struggle to work together for the common good […] And in the extraordinary humility of Christ coming among us a servant, there is I believe a special resonance with the kind of service we honour and commend here today.Footnote 61

A Belated Memorial: The Ruins of Dresden's Frauenkirche, 1945–89

During the dedication of the Home Front Memorial in March 2000, the archbishop of Canterbury brought up the ongoing restoration of the Frauenkirche in Dresden, specifically the support provided by Coventry Cathedral. Like so many commentators at the time, he considered the two churches twin symbols of resilience, resurrection, and reconciliation. The pairing of Coventry Cathedral and the Frauenkirche is a relatively recent phenomenon, though. For some forty-five years after the war, practically no one saw a connection between these two ruins, even though the two cities and dioceses had become, against all the odds, twins or partners at the height of the Cold War in the mid-1950s and 1960s respectively.Footnote 62

While the ruins of Coventry Cathedral were transformed into a site of—and memorial to—postwar reconciliation, the Frauenkirche's were not. The gutted baroque church was neither demolished, nor allowed to decay into disappearance. Instead, it was kept in its ruined state as a languishing landmark, with some of its fragments salvaged and catalogued, its vestiges periodically surveyed and secured—to what end, though, was left hanging in the balance. It was not a memorial, and there were sound reasons for not making it one. While the architecture had suffered serious but reparable damage, the institution was still tainted by recent history, for between 1934 and 1945 the Frauenkirche had served as the cathedral church of the Nazi-supporting group of German Christians (although it also had a connection with the rival Confessing Church).Footnote 63

Ironically, it was the extensive restoration work completed during the Third Reich that had left open the possibility that the Frauenkirche could rise again in the future. Miraculously, it seemed, the church, which had dominated the panorama of Dresden for two centuries, was still standing after the initial air raid on the Saxon capital on 13–14 February. Yet, on the morning of 15 February, the famous sandstone dome collapsed into a heap of rubble, burying everything below it, except for two jagged stumps. A few months later, the architect who had overseen the repairs carried out between 1937 and 1943 produced a report on the condition of the building. He was optimistic about the prospect of reconstructing the baroque building, designed by George Bähr and built between 1726 and 1743.Footnote 64 The foundation walls were still there, as were architectural drawings and photographs from the recent restoration. The job was challenging but not impossible. “Its execution requires a conductor-like architect,” suggested the organ of architects in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1955, a personality “who can bring it back to life according to the given score, like a Bachian oratorio to which the Frauenkirche is related in spirit.”Footnote 65 Despite the political rupture of 1945, the Frauenkirche retained her reputation as the jewel of German/Protestant church architecture, the finest baroque building north of the Alps—an image that was a relatively recent “invention of tradition,” dating from the late nineteenth century.Footnote 66

The real obstacle was not architectural skill but financial capability. In order to raise the funds necessary for such an ambitious project, the church authorities initially came up with some ingenious schemes, including the sale of commemorative objects—paperweights, crosses, and candlesticks—fashioned from the debris of the church.Footnote 67 It was a touching idea, although completely out of touch with the magnitude of the task at hand. Yet believers never gave up the hope of resurrecting the Frauenkirche. New impulses came in the second half of the 1950s, when leading West German churchmen associated with the former Confessing Church, above all Martin Niemöller (Hitler's “personal prisoner”), proposed internationalizing the rebuilding project. One such proposal envisaged setting up a joint venture between the Federal Republic of Germany and Western powers, an idea unpalatable to the communist regime and unwelcomed by the regional church leaders. For, by then, it had become apparent that the Frauenkirche was surplus to requirements in an era of dwindling congregations. Religious leaders’ new priority was maintaining functioning churches, not restoring architectural landmarks.Footnote 68

With the socialist state committed to transforming the skyline of Dresden, and the Lutheran Church unable and unwilling to finance the rebuilding, the Frauenkirche ruins were in danger of suffering the same fate as the ruined Sophienkirche. The former Franciscan monastery, which had served as the Protestant chapel royal between 1737 and 1918, was a long-standing thorn in the side of SED (Socialist Unity Party) bosses, notably General Secretary Walter Ulbricht.Footnote 69 Official representations and public protests notwithstanding, and even though it was one of Dresden's few remaining medieval buildings, it was torn down in 1962–63. Two years later, the Frauenkirche ruins were still standing, yet the structure was erased, literally, from the official city map.Footnote 70 A tourist brochure of the same year, entitled “Dresden: The New Construction [Neuaufbau] of the Modern, Socialist Metropolis,” mentions the ruined “Dresden Frauenkirche”—but only in inverted commas.Footnote 71 In all communist societies, building—literally and rhetorically—assumed great significance; for the SED, too, the (re)purification of urban space was a priority.Footnote 72 What saved the Frauenkirche from demolition was that the planners were preoccupied with other projects elsewhere in the city, above all the construction of a massive urban square suitable for state pageantry.Footnote 73

Since there was neither the political will to remove the ruins nor the financial ability to rebuild the church, the site became a “memorial,” twenty years after the air raid. It was a convenient solution for both the regime and the church. The former never bothered to confer with the latter, though. Mayor Gerhard Schill first mooted the idea in a letter to the president of the GDR parliament in 1962, but the ruins were not declared a memorial until 1965–66.Footnote 74 It took another year for an inauspicious plaque to be fixed to one of the surviving walls, without permission of the legal owners, the Lutheran Church, in 1967. And that was pretty much the end of the story. Thereafter, neither state nor church showed any inclination to use the ruins for commemorative ritual, or even to tidy up and curate the heap of burnt stones overgrown with weeds. The West German travel magazine Merian, reporting in 1967, was deeply unimpressed by the physical state of the ruins and dismissive of political attempts to make them a memorial, noting: “Unfortunately, the Frauenkirche is nothing more than a ‘memorial’,” suggesting that in its ruined state it was neither an architectural monument nor a proper war memorial.Footnote 75 Although the Frauenkirche memorial ruins became a popular postcard motif, it is difficult to determine how ordinary Dresdeners or West German visitors understood or interacted with them.Footnote 76 There are few traces of unofficial memorial practices. Some contemporaries may have regarded the ruins as an accidental war memorial; others perceived them principally as a lost jewel of baroque architecture.Footnote 77 The Dresden-born writer Erich Kästner, for one, treated the ruins as an architectural remnant of the legendary “Old Dresden,” not as a war memorial.Footnote 78

Two decades after the end of the war, the Frauenkirche became an official—but unused—“memorial” site shrouded in ambiguity. This should not surprise us. Retaining ruins as material evidence for the destructiveness of total war (and the perishability of memory) was anathema in communist societies. Leningrad, for instance, planted victory parks and built massive monuments but preserved no commemorative ruins. The war might have been etched into the Russian city's psyche, but it left few physical traces—and certainly none that were kept by design.Footnote 79 Likewise, the GDR's self-image as a forward-looking Aufbau (rebuilding) society—a state “risen from ruins,” according to its anthem—demanded making good the scars of war, not their cultivation.Footnote 80 Church ruins, in particular, had no value to the atheist regime. The memorial ruin—this “silent yet eloquent witness,” as one contemporary phrased it—was quintessentially a Western or capitalist phenomenon.Footnote 81 In West Germany, ruined churches offered symbolic foci that filled the gap between postwar speechlessness and self-pity. Prominent examples include St. Nikolai Church in Hamburg, Aegidien Church in Hanover, and, above all, the Gedächtniskirche in West Berlin (the latter, consisting of the stark shell of the old church and a modernist postwar building, was sometimes compared to Coventry Cathedral).Footnote 82 The ruin-turned-memorial allowed West Germans in the 1950s and early 1960s to reflect on personal suffering and historical impoverishment without recrimination, since “war”—prior to the anti-Vietnam War protests—was treated as an anonymous fate for which nobody could be held responsible.Footnote 83

The nuclear confrontation during the Cold War raised the specter of creating cityscapes beyond recognizable ruins. It was against the background of heightened apocalyptic fears and diplomatic tensions in early 1980 that Mayor Schill made the announcement (again, unilaterally, without consulting the church authorities) to install an “eternal memorial against war and destruction” on the site of the Frauenkirche.Footnote 84 That was on 13 February 1980, the thirty-fifth anniversary of the bombing, and the first time the Neumarkt square was chosen to host a commemorative rally. The mayor's ambition to revive remembrance ritual and reconfigure the commemorative landscape proved short-lived. The rally at the Frauenkirche ruins was a one-off event, and the grand plans for a memorial nothing more than hot air. Two years later, however, a new memorial tablet (in addition to the smaller plaque put up in 1967) was hastily erected, at the behest of the Central Committee of the SED.Footnote 85 Measuring 2.21 by 1.78 meters, it depicted an intact Frauenkirche. The inscription retrieved worn-out propaganda slogans about the “struggle against imperialist barbarism” (to which the Lutheran Church objected, to no effect).Footnote 86 Politicians in East Berlin were demanding a monumental statement, and pronto, having observed with some trepidation how local activists had hijacked the anniversary ritual and usurped symbolic space, notably the ruined church, for their purposes on 13 February 1982. In the run-up to the anniversary of the bombing, a band of teenage rebels distributed flyers inviting young people to gather at the Frauenkirche on 13 February. They proposed an informal and unconventional form of commemoration centered around the ruins, inspired by ritual forms pioneered by the American civil rights movement:

At 21.50 we will meet at the Frauenkirche. All are to bring flowers and a candle. The flowers will be arranged in the form of a cross, around which we sit down. We will place the candles in front of us (bring matches!). At 22.00 the church bells will ring! Afterwards we will wait for 2 minutes and then we will sing “We Shall Overcome.” The whole thing will take place in absolute silence. After the singing, we shall leave quietly after waiting for ca. 4 minutes.Footnote 87

The candlelit vigil at the Frauenkirche became an integral, albeit unofficial, element of the anniversaries during the 1980s, against the will of both church and state. The original sit-in idea of 1982 highlighted a shift in agency. Political dissidents and Christian youth were to become the most active and creative players, pushing the party-state as well as the Lutheran Church into a reactive role. The Stasi allocated more and more resources to countermeasures around the anniversaries during the 1980s, culminating in the prophetically code-named Operation “Ruin 89” in the year of the fall of the Berlin Wall.Footnote 88 Party bosses put all their hopes in a memorial tablet, viewing memorialization as a means of regaining the initiative they had lost in the realm of ritual; this was in vain, though, for official memory had lost its displacing forcefulness. It was grassroots practice, not official measures, that finally established the Frauenkirche as a true memorial—the Dresden memorial—almost forty years after the bombing of the city.Footnote 89

Ruins Restored: The Rebuilt Frauenkirche and Dresden's Memoryscape, 1990–2010

Symbolic performance recast the ruins as a dual memorial to the destructiveness of total war and the healing power of collective action. Yet the new-won status was almost immediately lost again. In the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall, a citizens’ initiative emerged that campaigned for a faithful reconstruction of the Frauenkirche, reusing as much as possible of the surviving fabric. Spearheaded by the trumpeter Ludwig Güttler, the initiative soon received prominent backing from the federal president, the Dresdner Bank, and various celebrities. Reconstituted as the Society for the Promotion of the Rebuilding of the Frauenkirche, it took part in international exhibitions (such as Expo 2000 and CeBIT), held charity concerts (for instance, with the tenor José Carreras), and sold merchandise (a children's book, a wristwatch, etc.). Local societies sprang up in a number of German cities as well as in Paris, New York, and Gostyń (Poland).Footnote 90 Private individuals were invited to adopt a stone, sponsor a seat, or purchase a donor's certificate. Work on the site commenced with the archaeological clearance of the ruins in early 1993. By August 1996 the undercroft was completed, and just over four years later the interior was also ready for use.Footnote 91 Finally, on 30 October 2005 the Frauenkirche was reconsecrated (Figure 4). Here was a beacon of European culture and a manifestation of German unity, as the federal president underlined in his speech.Footnote 92 What he did not say, however, was that Dresden had gained an uplifting symbol (popularly known as “The Wonder of Dresden”) but had lost a war memorial.Footnote 93 The people behind the project had, according to one psychological anthropologist, indulged in “monumental fetishism” in a futile attempt of “undoing trauma.”Footnote 94

Figure 4. Frauenkirche, Dresden, 1743/2005. Author's photograph, 2005.

The Frauenkirche society billed itself, not entirely without justification, as “the most successful cultural citizens’ movement of the German postwar period.”Footnote 95 It achieved its objective in a remarkably short time and against considerable resistance. The Lutheran Church initially distanced itself from the reconstruction project, saying it had no use for another church building (it later changed its stance).Footnote 96 German preservationists, except those based in Dresden, almost unanimously rejected the scheme, condemning it as gigantic kitsch. The director-general of the State Art Collections, Martin Roth, also heaped scorn on the project. “It's like IKEA,” Roth said, by which he presumably meant that it was inauthentic, because, at a cost of €180 million, it was certainly not cheap.Footnote 97

Earlier objections on grounds of religious need and preservation philosophy were broadened to include concerns about the loss of cultural memory. Reversing wartime destruction and socialist neglect came at the cost of undermining the Frauenkirche's critical memorial function. True, the blackened stones of the ruins were to be integrated into the bright sandstone structure, making them stand out visually. Yet, in the course of time, the old and the new are supposed to blend into one another, transfiguring rather than preserving the ruinous past—a form of “revisionist reconstruction” rather than “critical preservation.”Footnote 98 Not everybody was impressed. “I am annoyed that the Frauenkirche […] is to be rebuilt,” noted the American writer Kurt Vonnegut, expressing what many people seemed to feel: “I thought it was a perfect monument when a ruin to Western Civilization's effort to commit suicide in two world wars.”Footnote 99 Vonnegut, who had witnessed the bombing of Dresden as a prisoner-of-war, embodied for many the authoritative voice of the one-who-had-been-there. What Vonnegut did not realize, or had forgotten, was that this “perfect monument” was a relatively recent creation. For decades, it had been a mere heap of stones, half-heartedly declared a memorial, awaiting a decision that neither city planners nor church leaders had been prepared to take. It was civic action that transformed the site into a true memorial between 1982 and 1989; and it was civil society that did away with ruins in the 1990s.

Few of those who wanted “their church” back were churchgoers. Even fewer had a clear idea as to what the reconstructed church should or could be used for. East Germany in the 1980s and 1990s was one of the most secularized societies in Europe, and in Dresden there was already a surplus of churches. One of the earliest ideas, discussed behind the scenes in the mid-1980s, was to convert the church building into a memorial museum, housing a permanent exhibition about the “imperialist air war.”Footnote 100 But the GDR lacked the financial means to reconstruct the church and the political will to repurpose it. A serious discussion about a future use for the Frauenkirche could only be broached after the peaceful revolution of 1989. Veteran protesters, wary of the new feel-good language of peace and reconciliation, were generally opposed to the notion of losing “their ruins,” although some argued for the rebuilt Frauenkirche to become an international “peace center” dedicated to peace education and research.Footnote 101 The final decision rested with the Frauenkirche Foundation, set up jointly by the Lutheran Church, the city of Dresden, and the state of Saxony. It stipulated early on that the resurrected church would function again as a Protestant place of worship—even in the absence of a congregation. Following the completion of the undercroft in 1996, the Frauenkirche served a transient flock of occasional churchgoers and cultural tourists. Arguably, the Frauenkirche is a memorial first and a church second. Communion became separated from community.Footnote 102 Some called this a “missed opportunity” to establish a truly ecumenical center, a wasted chance to build a church fit for the twenty-first century.Footnote 103

The benchmark for success was Coventry Cathedral, and in many ways the Frauenkirche was modelled on the rebuilt Anglican cathedral and its mission of international reconciliation.Footnote 104 The ideas of atonement and forgiveness were built, quite literally, into the fabric of both churches. Just as the West German state and churches had contributed to the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral, so Britain supported the restoration of the Frauenkirche. The trauma of the bombing war found resolution in the celebration of reconciliation; rebuilding the church became an Anglo-German project embedded within a transnational one. Thus, in 1993 the Dresden Trust was formed as an “expression of the wish of people of the United Kingdom […] to offer the hand of friendship and reconciliation.”Footnote 105 The trust's claim to be “widely representative” was an exaggeration, although not a wild one.Footnote 106 Many ordinary Britons sponsored the work of the Dresden Trust, and so did British industry, while Coventry Cathedral provided crucial assistance with the fundraising campaign. The most eye-catching donation, an undisclosed sum, came from Queen Elizabeth II. Her visit to Dresden in 1992, during which the royal motorcade had driven past the Frauenkirche ruins, without stopping, had triggered mixed reactions.Footnote 107 Supporting the work of the trust was a way of setting the record straight.

A working member of the royal family, the Duke of Kent, became the patron of the trust. Representing the queen, the duke acknowledged Dresdeners’ grief and trauma by joining thousands of people who had gathered at the ruins carrying candles on 13 February 1995. Speaking in German, he came closer to offering an apology than any British official before or after him: “We deeply regret the suffering on all sides in the war. Today we especially remember that of the people of Dresden.”Footnote 108 As a gift, the duke had brought with him a design of the golden orb and cross that was to crown the reconstructed Frauenkirche and that the trust pledged to donate. The editorial in The Times commented perceptively: “Some Germans may interpret the present as a discrete apology. All can agree that it is a sincere act of reconciliation.”Footnote 109 All was said that could be said, and the Dresden Trust, eager to put the past behind, urged people to “look forward, not back.”Footnote 110 For his part, the duke skillfully moved on to other, more upbeat, themes on subsequent visits. Thus, he foregrounded Anglo-German friendship in 2000 and European unity in 2004.Footnote 111 This shift of emphasis was very much in line with the trust's raison d’être as an organization dedicated principally to reconciliation, not remembrance. Its chairman, Alan Russell, reasoned that “peace is not just the absence of war and that reconciliation means very much more than the sullen toleration of difference or defeat. It is, in effect, a profound, reflective and long-term process, requiring justice and freedom, forgiveness and love.”Footnote 112

Russell was the driving force behind the Dresden Trust. A convinced European and former official in the European Commission, he had studied philosophy, politics, and economics, and had a doctorate in modern history. And though he provided thoughtful perspectives on the moral philosophy underpinning the work of the trust, he was a doer not a theorist. His motto was borrowed from Erich Kästner: “Es gibt nichts Gutes, außer man tut es,” which translates roughly as actions speak louder than words.Footnote 113 The good deed in question was the donation of the great orb and cross: “The ultimate gift of reconciliation” and symbol of “lived reconciliation,” as the Coventry and Dresden press put it respectively, echoing each other's phrases.Footnote 114 The orb and cross (a replica of the eighteenth-century original) gave the trust a material focus for its fundraising activities—a “symbol more powerful than words,” according to the German president.Footnote 115 A tangible token of reconciliation, it was also supposed to showcase British craftsmanship, and thus the quality of the finished product had to be beyond criticism. Interestingly, the eighty-plus pages of specifications for the manufacture of the orb and cross do not mention the bombing once (not even in the first section entitled “Historical and General Background Information”), perhaps unsurprisingly because the trust's goal was to overcome the past and forge a hopeful future.Footnote 116

Alan Smith, the goldsmith responsible for making the orb and cross, knew all about the history anyway; his father had flown a Lancaster in the raid on Dresden. Smith understood his work as a form of Wiedergutmachung (“making good again”), the Sächsische Zeitung cited him as saying.Footnote 117 Although it seems unlikely that he would have used this essentially untranslatable and ambiguous term, the orb and cross were arguably a form of symbolic and material restitution, of making good, as well as a tangible financial contribution to the rebuilding project. Working on the orb and cross held a deep personal meaning for the goldsmith. A token of Anglo-German reconciliation, the cross was also a memorial to a witness of the bombing. “My father used to tell me about the horrors and the suffering of Dresden,” Smith told the British press. “He did not want it to be forgotten. By working on the cross I've come closer to my father and it's my way of saying goodbye to him and fulfilling his wishes.”Footnote 118

Over £1 million were donated to the Dresden Trust, a sum far exceeding the cost of the orb and cross. The remainder was used, inter alia, to finance the construction of two friendship gardens. The first British-German friendship garden was inaugurated at the National Memorial Arboretum in rural Staffordshire in the West Midlands in October 2006 (Figure 5), almost exactly one year after the completion of the Frauenkirche. Located thirty miles north of Coventry, this friendship garden is part of an emerging memorial landscape, sponsored by the Royal British Legion, which includes the Armed Forces Memorial to British servicemen and women killed on duty since the Second World War. Thus, the bombing war—or, rather, postwar reconciliation—found a place within a British site of national remembrance, itself inspired by the Arlington National Cemetery and United States National Arboretum in Washington. Steeped in a tradition of horticultural memorials, the friendship garden consists of two circles of weeping silver birches and a third circle created out of fourteen stones retrieved from the rubble of the Frauenkirche. On these stones are inscribed the names of twenty cities or regions that had suffered bombing in the Second World War. “It has a Dresden theme but stands for all people in both countries,” the trust stressed.Footnote 119 All the same, Coventry and Dresden take pride of place. A plaque on the central dedication stone explains (in both English and German) the idea behind the garden: “Just as Coventry has been rebuilt and Dresden has risen from the ashes of the firestorm which engulfed it on 13/14 February 1945, so have the friendship and mutual respect that traditionally characterised British German relations been reborn.” Here is a commemorative terrain in which the dialectics of memory give way to a reconciliatory synthesis.

Figure 5. British-German Friendship Garden, National Memorial Arboretum, Alrewas, inaugurated by the Duke of Kent, 2006. Author's photograph, 2006.

Five years later, the Dresden Trust donated 1,750 roses (including the varieties “Remembrance” and “Reconciliation”) for a second garden of friendship, planted at Rathausplatz in Dresden, opposite the synagogue.Footnote 120 Again, the location is highly symbolic, complicating the notion of “reconciliation” (a term that the Jewish community rejected anyway).Footnote 121 The new synagogue occupies the ground of the one destroyed during the so-called Kristallnacht pogrom. “The fire that Dresdeners set in the synagogue on 9 November 1938, came back to haunt the city on 13 February 1945, when Allied bombers reduced Dresden to rubble,” commented the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on 9 November 2001, the day of the opening of the new synagogue. Remarkably, the liberal-conservative broadsheet echoed a point that left-leaning local memory activists had been making for many years.Footnote 122 Challenging claims of German victimization, they argued that there was a causal connection between the two events, and that therefore the reconstruction of the Frauenkirche would be incomplete without the rebuilding of the synagogue. National and international supporters of the Frauenkirche project signed up to this idea, especially once they realized that Dresden was becoming a magnet for right-wing extremists and Holocaust deniers.Footnote 123 Notably, the chairman of the New York-based Friends of Dresden, the biologist Günter Blobel, divided his Nobel Prize money between the Frauenkirche and the synagogue. Unlike the Frauenkirche, the old synagogue, designed by Gottfried Semper, had vanished completely. After the pogrom the burnt-out shell of the building was razed to the ground; not a stone was left standing. But one thing survived: the Star of David, now integrated into the new building.Footnote 124 The new synagogue is thus different from the “redemptive reconstruction” of Jewish sites in (West) Germany from the 1980s onward. Previous projects, driven by the comforting illusion of “reconstructing multiethnicity from the ruins of multiethnicity,” had focused on the material remains of Jewish life.Footnote 125 The stark architecture of the Dresden's new synagogue, by contrast, exposes the catastrophic rupture between past and present. If anything, it is designed to counterbalance the pervasive trend toward reassembling the shattered fragments of the past.

A second architectural counterpoint to the Frauenkirche project—and the broader hope of and redemptive recovery from a ruinous past—arose in the form of the Busmannkapelle, a memorial chapel erected on the plot of the former Sophienkirche. While the new synagogue is a massive cube with few windows to the outside, this small chapel—or Denkraum (think-space)—is covered by a glass structure. Yet the two buildings are more similar than would appear at first sight. Both underline historical discontinuity. Each in its way is suggestive of a broken past that is not easily mended. In the case of the Sophienkirche, only the outer shell of the church remained standing after the February 1945 air raid. The parish council's proposal to turn the gutted church into memorial space—an idea inspired by Coventry Cathedral—fell on deaf ears; the ruins were pulled down in 1962–63 to make room for a mega-restaurant.Footnote 126 The Fresswürfel, as it was popularly known, was itself demolished after the collapse of the GDR.

Around the same time, a group of citizens started campaigning for the construction of a memorial on the site of the former church. They put their finger on the paradox of memory at work in contemporary Dresden: “Today,” they stated in 2005, “the Sophienkirche represents the Old Dresden more than the Zwinger, the palace, and the Frauenkirche possibly can: it no longer exists.”Footnote 127 Unlike the Frauenkirche project, this one was framed as a Mahnmal (memorial of admonition), with the intention of showing that the destruction of Dresden had begun well before the war and did not end with it: “The Sophienkirche was destroyed several times: spiritually, by the Nazi insanity of the German Christians; objectively, on 13 February 1945, in a military retaliation; materially, by ideological delusion in 1962/63.”Footnote 128

The glass structure houses an artificial, stylized ruin, which incorporates architectural fragments of the Gothic church. A Mahnmal intended to problematize the multifaceted legacies of destruction, this “think-space” was designed as a counterpoint to the reconstructed Frauenkirche, this domineering symbol of rebirth and reconciliation. And yet the supporters of the Sophienkirche project were unable to escape the dynamics of reconciliation. Together with the Frauenkirche, the Denkraum Sophienkirche was received into the community of the Cross of Nails, the cathedral's global network of partner institutions. Ruination had put Coventry Cathedral on the map in 1940; fifty years later, the link with Dresden helped reinforce and cement the cathedral's international profile. The ruins of war were the common denominator. “[I]n both cities […] the ruins of war became poignant symbols of what is means to remember and yet to forgive,” claimed Canon Oestreicher in 1999.Footnote 129 But while Coventry Cathedral thrived on the juxtaposition of ruination and rebuilding, the Frauenkirche dissolved this tension by blending ruins with reconstruction. Importantly, though, the Frauenkirche is not the only (former) ruin in Dresden. There are also the invisible but ever-present ruins of the old synagogue as well as the recreated, stylized “ruins” of the Sophienkirche. All three ruins together form a memorial landscape that speaks of savagery and suffering as well as recovery and rapprochement. In one way or another, the ruinous past has become incorporated into the material and moral fiber of the city.

Conclusion

Church ruins were silent witnesses to total war, accidental memorials that suited an age in which people turned against the idea of erecting another “cold stone memorial” so soon after the end of the First World War.Footnote 130 The disavowal of the traditional war memorial after 1945 had much to do with the fact that Great War memorials had seemingly “failed” to warn. “It is a kindred feeling which suggests that a war memorial should take a form which would contribute to the prevention of another war,” one architectural critic rather optimistically wrote in 1946. The logical consequence was that future memorials “must be international in character.”Footnote 131 The idea of a pacifist, supranational war memorial proved overambitious, but memorialization did take an international turn after the Second World War, above all at Coventry: the cathedral ruins were transformed into a worldwide symbol; the Charred Cross travelled to the United States and was displayed at the world's fair; the Reconciliation statue was part of an international network of sculptures. Similarly, the rebuilding of the Frauenkirche was, from the very first ideas mooted in the 1950s to its eventual execution after 1989–90, conceived of as a transnational and, above all, Anglo-German project, inspired by the rebuilt Coventry Cathedral. To be sure, the envisaged United Nations memorial was never built, yet Coventry Cathedral and the ruins—their message of forgiveness, compassion, and brotherhood—was the nearest thing: not a static signifier, but a dynamic site of reflection and reconciliation; not a war memorial fixated on the past, but a postwar memorial facing the future.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Philip Boobbyer, Mark Connelly, Laura Tradii, Jay Winter, and the journal's three anonymous readers for their perceptive comments on earlier versions of the article, and to Charlie Hall for his assistance in the early stages of this research.

Stefan Goebel is Reader in Modern British History and Director of the Centre for the History of War, Media and Society at the University of Kent at Canterbury.