Introduction

Though COVID-19 restrictions were still in place at the start of 2022, it quickly became clear that the expected surge in cases would not translate into illnesses and pressure on the health system. Restrictions were eased in January and completely removed by the end of February. In its place, the Russian invasion of Ukraine delivered a new set of crises for the Irish government to contend with. These took the form of high inflation, and so a cost-of-living crisis, and a surge in refugees, which led to the worsening of the housing crisis. Where opposition parties were broadly supportive of state action on COVID-19 measures, there was a return to normal opposition politics in 2022.

Election report

There were no elections in Ireland in 2022.

Cabinet report

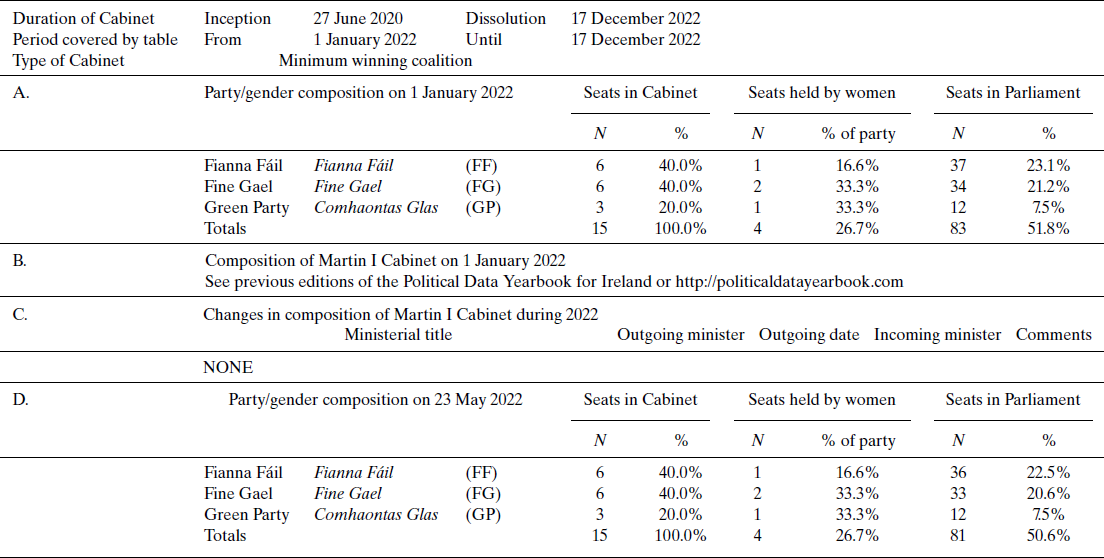

Ireland saw a new government at the end of the year, which showed very few significant changes from the previous government (Table 1) except for one, its head. In the Programme for Government (PfG) signed in the summer of 2020, it was agreed that in the mid-term of the government, the position of Taoiseach (Prime Minister) would be rotated, so the leader of Fianna Fáil, Micheál Martin, would cede the position to the leader of Fine Gael, Leo Varadkar (Lynch & O'Malley Reference Lynch and O'Malley2021: 186). This was an arrangement that had never been tried before, but never before had there been such an even distribution of seats among the top two government parties. There was some speculation in the run-up to the scheduled changeover in mid-December 2022 that Martin would renege and refuse to resign, though that was never likely as he could be forced to do so by a simple vote of no confidence.

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Martin I in Ireland in 2022

Notes:

1. Marc MacSharry resigned from Fianna Fáil and became an independent TD on 2 November 2022, bringing Fianna Fáil to 36 seats in the Dáil.

2. Minister of Justice, Helen McEntee (FG), took six months maternity leave beginning on 25 November 2022. She remained a member of Cabinet and her portfolio was covered by the Minister of Social Protection, Heather Humphreys (FG) until 17 December 2022.

3. Joe McHugh resigned the Fine Gael party whip on 6 July 2022, bringing Fine Gael to 33 seats in the Dáil.

Sources: Department of the Taoiseach and Oireachtas websites (2023). https://www.gov.ie/en/organisation/department-of-the-taoiseach/, https://www.oireachtas.ie/

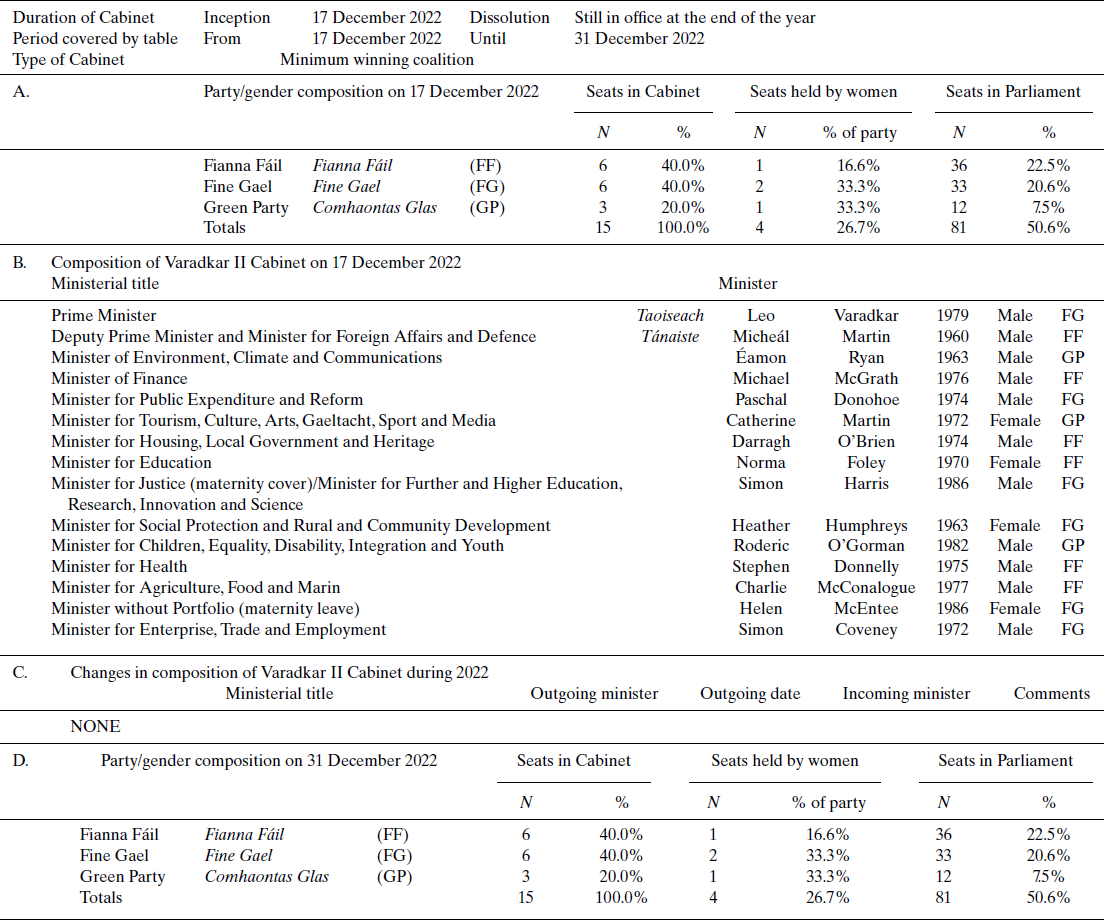

The date of the changeover was shifted back slightly to allow Martin to represent Ireland at an EU Council meeting, and on 17 December, Martin resigned as Taoiseach, and Varadkar was nominated by Dáil Éireann (lower house) for appointment by the President. The new cabinet saw minimal changes (Table 2). Micheál Martin became Tánaiste (Deputy Prime Minister) and Minister for Foreign Affairs, to enable him to remain involved in Northern Ireland policy. That meant that Simon Coveney shifted to Enterprise, Trade and Employment. The two main economic ministries held by Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael also swapped in a prearranged move: Paschal Donohoe moved to the Department of Public Expenditure, and Michael McGrath took over as Minister for Finance. Beyond that, there were few changes as a result of the change of government. The PfG still stood and the policy direction of the government remained the same. Though Varadkar was seen as more of an economic liberal than Martin, the reality of the government is that there is a dual-premiership, where the three party leaders have a mutual veto (for a discussion of this, see O'Malley & Martin Reference O'Malley, Martin, Coakley, Gallagher, O'Malley and Reidy2023).

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Varadkar II in Ireland in 2022

Notes:

1. Fianna Fáil lost one seat in 2022 (see notes in Table 1).

2. Fine Gael lost one seat in 2022 (see notes in Table 1).

3. Minister Helen McEntee (FG) took six months maternity leave beginning on 25 November 2022. Her portfolio is covered by Minister Simon Harris from the inception of this Cabinet.

Sources: Department of the Taoiseach and Oireachtas websites (2023). https://www.gov.ie/en/organisation/department-of-the-taoiseach/, https://www.oireachtas.ie/

Parliament report

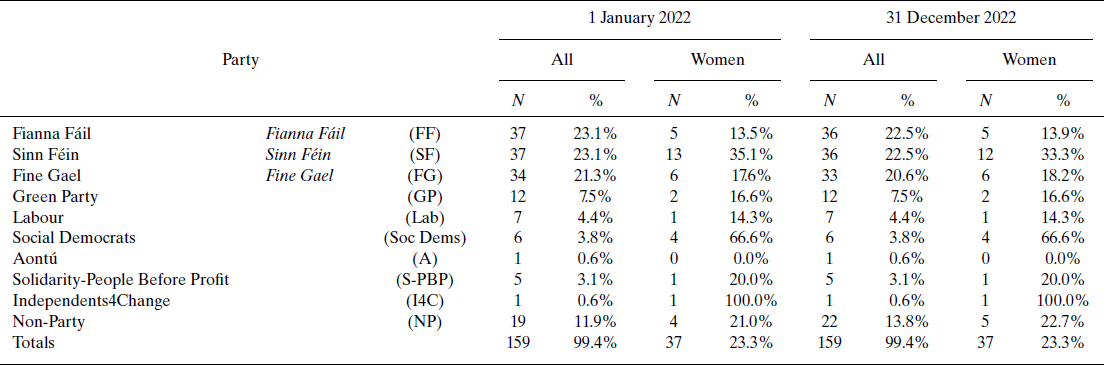

There were few changes to the parties’ representation in the Dáil (Table 3). Sinn Féin lost a seat when one of its TDs (MPs) resigned to become an independent citing a ‘campaign of psychological warfare’ against her. Sinn Féin is the most tightly controlled of all the parties, but its surge in support at the 2020 election saw many Sinn Féin candidates elected unexpectedly, many of whom were not fully integrated into the modus operandi of the party. One Fine Gael TD resigned from the parliamentary party in advance of a vote on compensation for homeowners whose houses were built with defective building material. Another TD who had lost the whip from Fianna Fáil in 2021 (see O'Malley Reference O'Malley2022) was expected to re-join the party, but the motion was revoked when allegations of bullying were made against him. He promptly resigned from the organisation and said he would contest the next election as an independent. Two Green Party TDs voted against the government on a motion on the use of church-owned land for a new National Maternity Hospital. They lost the party whip but were re-admitted into the parliamentary party late in the year. These two resignations from government eroded the government's technically slender majority, but as the vote on the formation of the new government revealed, it could usually rely on support from many independent TDs, including those who had resigned from government parties.

Table 3. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Parliament (Dáil Éireann) in Ireland in 2022

Notes:

1. Violet-Anne Wynne resigned from Sinn Féin and became an independent TD on 24 February 2022, bringing Sinn Féin to 36 seats in the Dáil.

2. There are 160 TDs (members of Parliament), including the Ceanna Comhairle (speaker) who was elected as a Fianna Fáil TD, but does not sit with the party or attend its meetings. He does, however, remain a member of that party. Except where there is a tie, he does not vote in divisions of the House.

Sources: Department of the Taoiseach and Oireachtas websites (2023). https://www.gov.ie/en/organisation/department-of-the-taoiseach/, https://www.oireachtas.ie/

Political party report

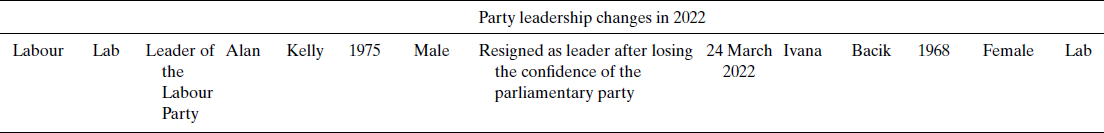

There had been speculation that there might be some move against Micheál Martin as party leader once he ceased to be Taoiseach, but this did not transpire. The only change was at the head of the Labour Party. There was some dissatisfaction with the performance of the party in the polls. Labour usually polled well in opposition, but in early 2022, it had barely shifted from polling between 3 per cent and 4 per cent.

The leader, Alan Kelly, had only been in office since 2020, during which time Ireland was in various forms of lockdown. But in early 2022, there were some in the party who wondered whether a change in leader might be the change needed to revitalise the party. Kelly was abrasive—his nickname was AK-47—and rural, which did not endear him to the more liberal, middle-class members on the east coast. In fact, Labour's problem was that many working-class voters had shifted to Sinn Féin, and many of the liberal ones were newly enamoured with the Social Democrats. In early March 2022, three members of the parliamentary party (Duncan Smith TD, Seán Sherlock TD and Senator Mark Wall) approached Kelly to say he had lost the confidence of the parliamentary party, and he promptly resigned. Only one person emerged as a replacement. Ivana Bacik had been elected in a by-election a year earlier, but she was well known in the party and among the public as a feminist campaigner (see O'Malley Reference O'Malley2022). Bacik was made leader without a contest (Table 4). Seen as likely to emphasise gender and social issues more than class issues, by the end of 2022, she had made no appreciable difference to Labour support.

Table 4. Changes in political parties in Ireland in 2022

Sources: Department of the Taoiseach and Oireachtas websites (2023). https://www.gov.ie/en/organisation/department-of-the-taoiseach/, https://www.oireachtas.ie/

Issues in national politics

Any chance that the government could enjoy the return to normality with the lifting of social restrictions due to the pandemic was scotched by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Even before the invasion took place, there had been increases in petrol prices and heating bills. After the invasion, this inflation jumped markedly. Though the introduction of carbon taxes had been an issue of contention in the formation of the Martin I government and continued to divide the parties in government, a number of measures were agreed upon in March and throughout the year that essentially wiped out the effect of the increase in the carbon tax, which went ahead later in the year.

There were cuts in VAT on heating bills, as well as cuts to excise duty on fuel. The government removed a levy on fuel used to build up the national energy reserves. The government also gave each household a grant or energy credit of €200. This was extended later in the year in a ‘cost-of-living budget’ that aimed at mitigating the effects of inflation. This cost about €8 billion, but the buoyant state of the economy meant that the government could easily afford it. The question being asked at the end of 2022 was whether some of those reductions in fuel taxes could be removed without a political backlash.

Related to the invasion of Ukraine was the surge in the number of people seeking asylum in Ireland. Ireland took in almost 70,000 refugees from Ukraine in 2022, which was higher per capita, compared to any other Western European country. While they were welcomed, the government struggled to house all these refugees from the war. A memo to the Cabinet in the summer expressed concern that if the large numbers kept arriving, it would be difficult to integrate them all, and it potentially posed a risk to social cohesion in deprived areas.

By the end of the year, that came to pass. Some protests occurred in smaller towns that had seen their hotels taken to house refugees, particularly ones from the Middle East and North Africa. When a Dublin office block in a working-class area was repurposed to house male, non-Ukrainian refugees, protests sprung up citing security concerns. The support for these protests was in part genuine from local residents, but it was also clear that these were being orchestrated by nationalist groups. These groups organised more protests leading to traffic disruption in Dublin. One poll in late October, before protests became common, showed that over 60 per cent of respondents were concerned there were ‘too many refugees coming here’ (Leahy Reference Leahy2022). None of the established political parties, including Sinn Féin, which might have been thought to have the most to lose from the emerging anti-immigrant sentiment, pandered to the protesters, however.

Much of the emphasis in the protests against refugees was that they felt the government was going to great lengths to house refugees but making no similar effort to solve the still worsening housing crisis. Homeless figures rose from about 9,000 to over 11,000 by the end of the year. Yet these figures mask what was a much more widespread problem. Rents in Ireland continued to rise to barely sustainable levels, and the age at which people were likely to stop living with their parents rose with it. Government efforts to deal with the problem seemed anaemic at best. Certainly, compared to the rapid and concerted response the state made to the pandemic, there appeared to be no such sense of action in relation to housing. Surveys continued to show the issue was that of greatest concern to voters and less than a third of respondents to one poll thought the government was making progress on housing (Leahy Reference Leahy2022).

The year 2022 also saw emerging allegations of corruption or poor standards in politics. In advance of the elevation of Leo Varadkar from Tánaiste to Taoiseach, revelations that he had shared a confidential memo containing a proposed pay agreement with an acquaintance who had an interest in that agreement caused a Garda (police) investigation. The Gardaí referred the issue to the Director for Public Prosecutions. She decided there was no case to answer, and in November, the Standards in Public Office also found that Varadkar had done nothing wrong. It was odd that it had even gotten that far, as there was a reasonable political excuse for the so-called ‘leak’. While few took those allegations seriously, it was used by populist opposition parties to create an image of cronyism and low standards in the government parties.

A news website, The Ditch, funded by a wealthy businessman revealed that one (politically-appointed) member of An Bord Pleanála (the planning board) had made decisions in which there was a clear conflict of interest. This led to more revelations of unusual practices in the board. The chair resigned and the government announced that it would overhaul the board and its powers.

The Ditch was also central to revelations that a junior minister in the government, Robert Troy (Fianna Fáil) had failed to declare several property interests. Though he claimed they were ‘genuine errors’, his revelation that he owned or co-owned 11 properties was met with anger and incredulity, especially given the housing crisis. He eventually resigned his ministerial position, but the affair damaged the government's reputation somewhat and created some fission within the government. But any division between the government parties was not deep enough to challenge what was an emerging centrist alliance, challenged by a more populist left opposition led by Sinn Féin.

Acknowledgment

Open access funding provided by IReL.