Versailles, Berlin, Belfast, Odessa

What is the Third Estate? Everything.

What has it been in the political order so far? Nothing.

What does it demand? To become something.

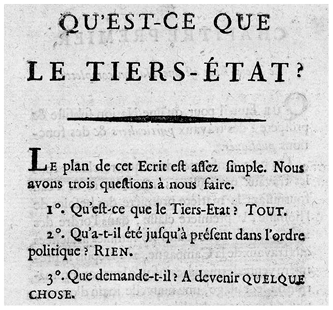

The formative moments in the emergence of the nation as a political principle were 1789 (Versailles) and 1808 (Berlin).1 In June 1789, delegates of the French Third Estate gathered in Versailles as the French Revolution was forming in the air. That ‘Third Estate’ was a container term for those who were neither prelates nor noblemen. In the words of the seminal pamphlet by Emmanuel Sieyès, Qu’est-ce que le tiers état?, the Third Estate had always been ‘Everything’ in socio-economic terms, had amounted to ‘Nothing’ in the running of the state, and now demanded, politically, to ‘become Something’ (Figure 2.1). As the political events of mid-1789 unfolded, this Third Estate constituted itself into a mandate-giving representative body. That body christened itself, at the suggestion of the same Sieyès, the Assemblée nationale, and thereby gave the word nation a new political meaning. The nation was the Something that the Third Estate aspired to become. Their assemblée was the rump continuation of a meeting of the Estates General that, convoked by King Louis XVI, had disbanded when Louis found the delegates too fractious and rebellious. The First and Second Estates (clergy and nobility) obeyed the king’s dissolution of the Estates General and disbanded, but the Third Estate vowed to remain in session until they had given France a constitution. It was this decision that formed the actual beginning of the French Revolution; the storming of the Bastille took place almost a month later (14 July). In August 1789 the Assemblée nationale voted for the abolition of feudalism and enacted the Declaration of Human and Civil Rights. In the space of two months, the nation had definitely managed to become Something.

Figure 2.1 Opening page of Emmanuel Sieyès’s What Is the Third Estate? (Reference Sieyès1789).

In 1808 in Germany, the nation also became Something; in this case, it became the principle that was called upon to fill the void left by the imploding Reich. Following the imposition of Napoleonic overlordship, the thousand-year-old empire (formally known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, das Heilige Römische Reich Deutscher Nation) had abolished itself in 1806. At that juncture, the celebrated philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte held public lectures (Reden an die deutsche Nation, Reference Fichte1808), in which he addressed the bereft ‘Deutsche Nation’; he implicitly redefined them as the subsisting body politic of the now-defunct empire. He, too, tried to turn the nation into Something: a continuity principle,2 a cultural community, autonomously existing as such on the basis of a common language, a common past and shared values. That nation, now culturally rather than constitutionally defined, was to become the focus of the political loyalty and aspirations of the German Romantic generation. Fichte’s Reden followed and consolidated a line of argument already thought out by Schiller in 1797, when territorial losses had begun to threaten the millennial fabric of the Holy Roman Empire:

Can the German, with head held confidently high, take his place among the nations? Yes he can! The German Reich and the German nation are two different things. The Germans’ majesty never rested on the head of their monarch. Outside the realm of the political, Germans have established a dignity unto themselves, and even were the Empire to go under, that German dignity would remain unimpeached. It is a moral quantity, residing in the nation’s culture and character, which is independent of its political vicissitudes.3

This emergence of the nation as a political Something was provoked, in France and in Germany, by constitutional crises requiring a redefinition of the relations between the state and its taxpayers. But there was a new force at work as well, and it was operative in various places along the edges of the European monarchies and empires: people were rejecting state rule altogether because it was considered an alien imposition. A separatist, republican rebellion took place in Ireland in 1798; an anti-Ottoman secret society was founded by Greek merchants in Odessa in 1814. Both invoked the right of the people to secede from, or to rise against, a government they considered tyrannical. In that respect they were both inspired by the American and French Revolutions of 1776 and 1789 and by the notion of popular sovereignty. But in these cases, popular sovereignty was invoked to secede from states whose governments were denounced not only as despotic but also as a foreign yoke (English and Turkish, respectively) on their own nation (Irish, not English; Greek, not Turkish). The aim was not to reform the state but to secede from it; and unlike the Founding Fathers in the United States, they aimed not to start a new state afresh but rather to re-establish an ancient one that in the course of history had been vanquished and conquered.

Belfast to Odessa: the European span does not get much wider, either in space or indeed in time. Those two cities have remained flashpoints in Europe’s national conflicts ever since. Everywhere along the tectonic faultlines of Europe, the seismic tremors were noticed, along the grinding edges of the British, Spanish, French, Habsburg, Romanov and Ottoman Empires. The political seismographs register violent regime changes and internal conflicts, fluttering between sullen disaffection and open rebellion. In the Southern Netherlands (present-day Belgium) anti-Austrian resistance was distributed evenly between radical and traditionalist factions; in the Balkans, Serbian and Romanian resistance against Ottoman rule was no less vehement than in Greece; in the Tyrol, the enforced transfer from Austria to Bavaria in 1805 was hotly resented and led to a rebellion; in Scandinavia, where in 1809 Finland was moved from Sweden to Russia and in 1814 Norway was moved from Denmark to Sweden, both Norway and Finland strove to maintain constitutional liberties in the process; in Spain, the Carlist wars affected the Basque and Catalan fueros (local autonomies) and provoked regionalist consciousness-raising.

States, Subjects, Secret Societies

The epicentre of all this was Napoleon, who vanquished and abolished ancient realms and created new ones at will. In the span of a few years, he put an end to the Papal States and to the Venetian, Swiss and Dutch republics; conquered Spain and Naples and humiliated Prussia; reduced and annexed sovereign German lordships, temporal and ecclesiastical; and drove the venerable Holy Roman Empire to self-abolish as he crowned himself an Emperor of the French. And then his own empire crashed and burned – not once, but twice. First at the Battle of Leipzig (1813), which sent him off to Elba, and then again at Waterloo (1815), which sent him off to St Helena.

The European state system staggered out of the Napoleonic upheavals with a desperate need for, above all else, stability. The congress system devised by Austria’s chancellor Clemens von Metternich attempted to provide this. The balance of power in Europe was regulated by diplomats who at crisis moments would convene to work out solutions, first at the Congress of Vienna (1814), then at further follow-up congresses. The one at Aachen (1818) was notable for taking repressive measures (such as censorship) against democratic activism and aspirations. This persecution of ‘demagogues’ affected many of the Romantic intellectuals who had supported the insurrection against Napoleonic hegemony: the pamphleteer and versifier Ernst Moritz Arndt, the theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, the gymnastics organizer Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, the folksong collector Werner von Haxthausen, the student activist Hans Ferdinand Maßmann. For indeed the Napoleonic period had left Europe sharply divided ideologically: the restored monarchical governments aimed above all to return to their old authoritative positions and abhorred the French liberté, égalité, fraternité as a sinister force of anarchism and upheaval. A ‘democrat’ in their understanding of the word was a fanatical sans-culotte itching to unleash the terreur of the guillotine. But many populations in Europe, though they had come to abhor Napoleon as a warmongering despot, had tasted the benefits of a state that was based not on the privileges of the aristocracy but on a constitution with citizens’ equality before the law. After an anti-Napoleonic honeymoon period of 1813–1817, that friction between princes and peoples became apparent again. The reinstated monarchs, who had initially agreed to rule constitutionally rather than absolutely, tended to ignore the constitutions they had half-heartedly accepted, to whittle them away or even to abolish them.4

Signs of unrest at this reactionary trend flared up at various points on the European map. As early as 1817, a commemorative feast at the Wartburg Castle, bringing together students who had seen military action in 1813, turned into an act of defiance; in its wake, a participating student activist murdered a writer who was seen as an advocate of reactionary absolutism, and this in turn triggered the repressive measures of the Aachen Congress. Semi-private societies, modelled on the German Tugendbund (an anti-Napoleonic organization in Prussia in 1808–1809) and on the template of masonic lodges, kept the idea of patriotic civic empowerment alive.Footnote * As they were regarded with increasing suspicion by the authorities, these organizations retreated into discreet obscurity and in the process acquired the aura of sinister secret societies. At the Polish-Lithuanian University of Vilnius, now under Russian rule, a group of liberal-minded intellectuals was active in the early 1820s, with a visible outer layer known as the Philomaths harbouring a more radical inner circle, the Philarets. They were disbanded and harshly sentenced by the Russian authorities in 1823; but they were a first sign that the Polish intelligentsia would not abide by the continuing dismemberment of what once had been a separate realm (the united Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania). Ex-Philarets in exile who would continue their advocacy for a separate Polish nationality were the poet Adam Mickiewicz and the historian Joachim Lelewel. The university itself was closed down after the Polish Uprising of 1831. (Ironically, its books were distributed among newly founded universities in the Ukraine, which would later on become seedbeds of Ukrainian nationalism.) Meanwhile Russia itself had experienced the shock of the Decembrist revolt of 1825, which hastened the tsar’s paranoid withdrawal into reactionary absolutism. At the same time, however, Russia’s geopolitical rivalry with the Ottoman Empire (which had been excluded from Metternich’s congress system) developed into a semi-mystical mission to re-establish Christianity in Jerusalem and Istanbul; disaffected subjects of the Ottoman sultan were welcomed and supported in Russia on the basis of their shared orthodox religion. Macedonians, Bulgarians, Romanians and Greeks could find refuge and succour in Moscow or Odessa, and it is in the latter city that another secret society with nationalist aims was founded: the Greek Filiki Eteria (Φιληκη εταιρια: literally, ‘Friendly Society’).5 Pushkin, in provincial exile from Moscow, became an early sympathizer and was enrolled as a member. The euphemistic high-mindedness of that name recalls the German Tugendbund (‘Virtue Association’) and the Philomaths and Philarets (‘Friends of Science’/‘Friends of Virtue’). Similarly, the groups behind the Decembrist revolt of 1825 called themselves the ‘Union of Salvation’ in 1816, morphing into a ‘Society of True and Loyal Sons of the Fatherland’ in 1817 and into a ‘Union of Prosperity’ in 1818. These were obviously what Tolstoy had in mind when, at the end of War and Peace, he mentions Pierre Bezukhov’s project for a reformist association:

‘And what position [Nikolai Rostov asks] will you adopt toward the government?’

‘Why, the position of assistants. … We join hands only for the public welfare and the general safety.’

‘Yes, but it’s a secret society and therefore a hostile and harmful one which can only cause harm.’

‘Why? Did the Tugendbund which saved Europe … do any harm?’Footnote *

Meanwhile, in Italy, where absolute rule had been restored in the Kingdom of Naples and the Papal States, a group called the Carbonari resisted; there were imitators of that resistance in restoration France, the Charbonnerie. In time the Carbonari would evolve into the Young Italy movement led by Mazzini and Garibaldi. That, in turn, would inspire a number of national reform movements across the century, from Junges Deutschland to the Young Turks.6

In Germany, anti-absolutism initially took a more coded, cultural form: a cult of Schiller commemorations in the 1820s recalled how that great poet had celebrated the unification and revolt of the Swiss cantons under Wilhelm Tell (see Figure 10.1) and how he had passionately asserted the right to freedom of thought in his Don Carlos. A popular song, ‘Die Gedanken sind frei’, had been published in Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano’s anthology Des Knaben Wunderhorn in 1808, and it remained a widespread, subversive inspiration well into the twentieth century: it was distributed in the Commersbuch student songbooks (see Chapter 9), played by Sophie Scholl to her imprisoned father in 1942, and sung by demonstrators in blockaded Berlin in 1948.7

The anti-Napoleonic restoration tried to obliterate the memory of democracy; but the memory was kept alive in semi-clandestine cultural form. It would become a programme not just of political emancipation but of national liberation.

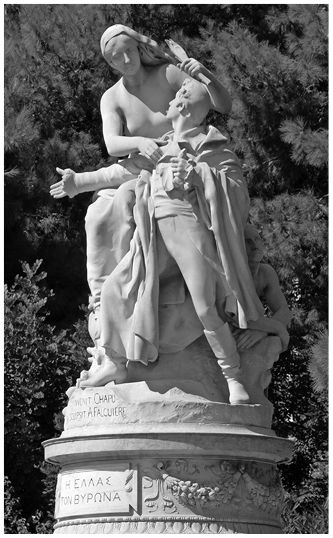

Uprisings

The Metternich system was rocked on its foundations by a number of revolts. The earliest of these (Serbia in 1816; Greece and Romania, masterminded by the Filiki Eteria, in 1822) were anti-Ottoman in character and took place in the Turkish-ruled Balkans; as such, they could still be seen as external to the congress system’s remit. But the ongoing decline of that alien Islamic empire would nonetheless affect Europe deeply. A wave of sympathy for the Greek cause – philhellenism – swept across Europe in the 1820s, and provided a coded outlet for anti-Metternich feeling among progressives. Some young men took active service to support the Greek cause, but most foregrounded was the cultural and moral–intellectual support, expressed in poetry, painting (Delacroix) and philology (Claude Fauriel editing collections of Greek insurrectionist songs in 1824). The symbolic culmination came when the Romantic poet Byron, who had become famous with dramatic poems set in the Ottoman-ruled Levant, embarked for Greece and died in besieged Missolonghi in 1824 (Figure 2.2).8

Figure 2.2 Statue of Byron in Athens (Henri-Michel Chapu and Alexandre Falguière, 1896): the Greek goddess of fame pulls the dying poet heavenwards.

Finally in 1832, the European powers, despite their ingrained mistrust of popular sovereignty, came down on the side of the Greeks and agreed to sponsor the establishment of an independent Greek kingdom: this took the place of the Hellenic Republic of 1822, the first new European state in the century of nationalism.Footnote *

The Hellenic Republic was followed by Belgium. In 1830, liberal anti-restoration revolts broke out in many European states. In France, the reactionary autocrat Charles X was replaced by the constitutional ‘bourgeois king’ Louis-Philippe. Revolts in Brunswick, Hanover and Saxony enforced constitutional changes. But the Southern Netherlands went further: rechristening themselves ‘Belgium’, they formally seceded from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and its reactionary king Willem I and proclaimed a separate state. After some geopolitical balancing between neighbouring Germany and France, Belgium was internationally recognized, under a king from the German house of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, brother-in-law to the future English queen Victoria and son-in-law to the French king Louis-Philippe. The country’s neutrality was internationally guaranteed – something that would become a casus belli when German armies, singing ‘Die Wacht am Rhein’ and on their way to defend that river against the perfidious French, invaded the country in 1914.

In 1830, again, the French and Belgian examples inspired an uprising in the Russian portion of partitioned Poland. Like the Greek one, it triggered a wave of sympathy among European progressives. Its own battle slogan (‘For our freedom and yours’) played into this sense that the cause of defending the people’s (‘national’) liberty against autocratic rule was a universal one. Indeed, the uprising was triggered by the refusal of Polish officers to be deployed for the intended repression of the Paris and Brussels revolts. The Polish Uprising was doomed, and henceforth the tsar became a despised symbol of tyranny and oriental despotism among European progressives everywhere. (He would in 1848 send troops to repress the anti-Habsburg revolt in Budapest, following the logic of the Metternich system.) A renewed Polish uprising in 1863 was equally unsuccessful, with many participants and sympathizers being sent to Siberia, but the cause of Poland was by now firmly accepted by liberal European opinion, thanks in no small part to its artists and intellectuals in exile: Mickiewicz, Lelewel, Chopin. The internationalism of the freedom fighters of 1830 became a universalist messianism: the sufferings of Poland were sufferings on behalf of Europe’s liberty generally. The Polish anthem ‘Not Yet is Poland Lost’ was adapted to become that of Croatian nationalists as well.9

1848 and the End of the Congress System

Belgium apart, it was only in the Balkans that the cause of national self-determination made any headway during this time, and that was largely thanks to the decrepitude of the Ottoman Empire. In the mid-century decades, Serbia and the Danubian provinces gained in autonomy and Greece began a process of territorial expansion. Elsewhere in Europe, national movements failed to wrest power from the state but, in the process of trying, gained influence and public sympathy for their principles. Sociability increased – choirs, athletic societies, book clubs and cultural societies with periodicals – and increasingly became platforms for the proclamation of national ideals. The political secret societies of yore were evolving into grass-roots cultural associations. Europe was now replete with self-defining nations with memories of ancient (feudal or pre-modern) autonomy. As their historical consciousness deepened (discussed in Chapter 7), these erstwhile realms and fiefdoms were beginning to chafe at the their contemporary subaltern and disempowered positions: Iceland, Norway, Ireland, Catalonia, Bohemia, Poland, Croatia, Hungary, Bulgaria. And in Germany, philologists and historians refused to acquiesce altogether to the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire with its vestiges of deep tribal–ancestral traditions. Its abolition was felt as an irksome and wrongful truncation of historical continuity, and a Reichsidee subsisted culturally as a vaguely felt nostalgia.10

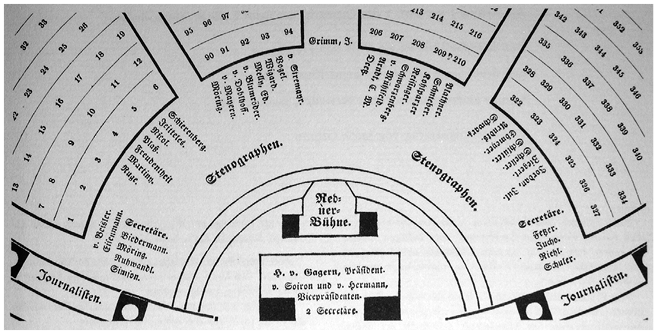

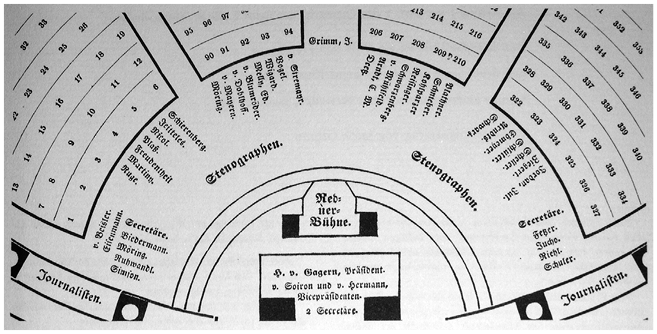

A revolutionary upheaval came in 1848, when activists attempted to unify Germany politically by means of a Nationalversammlung (National Assembly) in the Free Imperial City of Frankfurt. (The patriotic Germans, by now habituated into a firm dislike of everything French, would have been aghast had they realized that they owed both the template and the name of this National Assembly to Emmanuel Sieyès.) The Nationalversammlung, in which intellectuals of the Romantic generation – Jacob Grimm, Ernst Moritz Arndt, Ludwig Uhland – took pride of place (Figure 2.3), failed to realize these unifying aims; the delegates had little or no standing with the autocratic German princes, were split between a radical left and a traditionalist right wing, and were divided even on the question as to which lands of the former Holy Roman Empire, north and/or south of the Alps, were to be included as ‘German’ in the new, national sense. But what they did achieve was to revive and turbocharge the dormant Reichsidee, the notion that the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire was merely a suspension, an interregnum, and that the Reich was in abeyance, awaiting its future revival and reconstitution.11

Figure 2.3 Seating plan of the Frankfurt National Assembly (1848). Jacob Grimm occupies an impartial seat of honour, centrally in the front row.

One imperial crown land that had been invited to attend, Bohemia (under Habsburg rule), used the occasion to firmly opt out of this once-and-future Reich. Its invited representative, the Czech historian František Palacký, declined the invitation, stating that as a Slav and as representative of the Czech Slavs of Bohemia, he had no reason to come to Frankfurt to join a German national love-in. Palacký and fellow Slavs even set up a rival to the Frankfurt Parliament in Prague: the Slavic Congress. It was attended by Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenians, Croatians, Serbian, Bulgarians, Sorbians and Poles, who proclaimed the unity of all Slavic nations in Europe, and their ambition to ‘become Something’.12

Both the Slavic and the Frankfurt assemblies foundered in the disordered revolutionary events of 1848. That year saw the overthrow of kings Louis-Philippe of France and Ludwig of Bavaria. Habsburg power tottered (and Metternich’s career finally ended) as Hungarian nationalists, inspired by the poet Petőfi and led by Lajos Kossuth, rose in arms to claim self-determination.13

All these revolutions failed – only in France was a republic established, and it was soon to be hijacked by Napoleon III. The Habsburg regime post-1848 strenuously discountenanced any form of nationalist activism in its many non-German provinces, Slavic and Italian. And with Metternich gone and France (briefly) a republic, the old congress system of 1813 broke down.14

A war between Russia and the weakened Ottoman Empire soon followed, with some of the heaviest action taking place on the Crimean peninsula. It saw France and the United Kingdom intervene, strange to say, on the Turkish side, worried as they were about Russian expansionism around the shores of the Black Sea. The Ottoman Empire had enacted its Tanzimat reforms in 1837 and was modernizing; Russia, on the other hand, had proved itself to be ruthlessly autocratic. It was now moot who the true oriental despot was. The Crimean War of 1853–1856 signalled the beginning of an uneasy jockeying for position between the European powers, each seeking to strengthen its position through shifting and constantly renegotiated alliances.

In those unsettled circumstances, Italy was able, with covert support from France, to finally achieve a united statehood in 1861 under the rule of the King of Sardinia, Vittorio Emmanuele – much to the disgust of the original republican instigators of the Risorgimento, Mazzini and Garibaldi. Bismarck engineered the rise of Prussia to become a major European power with a cunning combination of diplomacy and carefully calibrated wars: against Denmark (1864), against Austria (1866) and finally against France (1870). Now it was time for Denmark, Austria and France to live through their own ‘culture of defeat’. In Denmark, dreams of becoming the centre of a Scandinavian Union evaporated, and the country settled into post-imperial domestic disenchantment. In France, revanchist resentment against Germany grew over the loss of Alsace-Lorraine; during the toxic and relentlessly protracted Dreyfus affair, anti-Semitism mixed with ultramontanist Catholicism and reactionary conservatism to spawn something for which the journalist Maurice Barrès coined the word nationalisme. He introduced the term in an article in Le Figaro in 1892 (‘La querelle des nationalistes et des cosmopolites’), and it was thenceforth used to define a system of thought centred on the exaltation of the national idea and anti-cosmopolitanism. His trilogy of novels Les déracinés (1897), L’appel au soldat (1900) and Leurs figures (1902) continued to exhibit this combination of xenophobia, chauvinism and conservatism, which also found an outlet in the movement/newspaper L’Action française (cofounded by Barrès in 1899). Barrès’s impact on public opinion was acknowledged by his election to the Académie française in 1906.15

Austria’s defeat by Prussia in 1866 forced it to marshal its inner resources and to make concessions to its minority nationalities, especially the Hungarians; it reinvented itself as a ‘dual monarchy’, consisting of an autonomous Hungarian Kingdom in personal union with an Austrian Empire. Over the next decades, the dual monarchy cultivated the idea of a Vielvölkerstaat, a multi-ethnic empire where all nationalities would happily coexist in common loyalty to a paternal monarch. (This model was attractive to moderate Irish nationalists, who wanted to achieve a similar autonomy for their country in an imperial British setting.) Strauss’s operetta Die Fledermaus (1874) accordingly contained ballet music combining a Viennese waltz, a Hungarian csardas, and a Bohemian polka yoked with a Polish mazurka.

This operetta model cast a golden sheen over what in hindsight became known as the belle époque. Younger sons from German dynasties (Wittelsbach, Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Hohenzollern and Battenberg) were placed on the thrones of the newly created kingdoms of Greece, Romania and Bulgaria. Alongside the princes of Serbia and Montenegro from the native dynasties of Obrenović and Njegoš, their courts, set in Ottoman-style or neo-Gothic palaces, presented to western onlookers a theatrical and slightly gimcrack aspect, summarized in the notion of ‘Ruritania’ or ‘operetta state’.Footnote * At the same time, a fairy-tale glamour began to be attached to the queens of the European monarchies, who represented the sentimental ‘soft power’ of their dynastic houses: Queen Louise of Prussia of revered memory, (young) queen Victoria, Empress Sissi, Queen Elisabeth of Romania (a poet under the pen name of Carmen Sylva, née von Wied); such soft power was also wielded by the gender-bending, extravagant Ludwig II of Bavaria.16 The iconography of ‘Disney Princesses’ and the continuing appeal of sentimental monarchy kitsch derives from the twin ancestry of Grimm’s fairy tales and these Romantic queens – witness the design of the castle of Disneyland, modelled after Ludwig of Bavaria’s Neuschwanstein.

Underneath this Ruritanian glamour, geopolitical wars in the Balkans would continue, with Austria annexing Bosnia-Herzegovina to thwart Serbian expansionism, Bulgaria achieving independence in 1878, Greece eating progressively into Ottoman territory, and the newly independent states jostling for territory.

This continued until the very eve of the Great War. In March 1914, Prince Wilhelm of Wied mounted the wobbly throne of a newly created Principality of Albania; less than four months later, the Habsburg archduke Franz Ferdinand was shot in Sarajevo. In August, young Adolf Hitler passed the Germania monument on the Rhine as a member of the Bavarian forces deployed on the Western Front.

The Nation-State and the Unmaking of Empires

Russia’s defeat by Japan in 1904 presented a similar crisis for the Russian empire to that which Austria had experienced in 1866. In 1905, Russia’s autocracy was relaxed and we see a drive towards autonomy accelerate in the empire’s western provinces: Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, Ukraine. Once again, achieving national autonomy was a question of opportunism, making use of the weakening of imperial power following a defeat. The final opportunity presented itself when the Russian empire collapsed into revolution in 1917, with its minority nationalities on the periphery achieving autonomy; many of them (Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia) were later eaten up by the new Bolshevik USSR, but Finland, the Baltic states and Poland maintained their independence, Poland and Lithuania immediately entering into hostilities over the city of Vilnius. At the Paris Peace conference, the American president Woodrow Wilson introduced the principle of ‘national self-determination’ as a cogent principle that served to dismember the vanquished Ottoman and Habsburg Empires. The nation had definitely become Something: if you were a nation, you were entitled to an autonomous state. By 1918, many provincial peripheries of Europe’s empires, from Helsinki to Novi Sad and from Gdańsk to Trieste, were freed from their imperial subservience and achieved independence. Of the western minority nations, only Ireland was able to fight the battle-weary British Empire into a standoff and an uneasy compromise, which left the issue of Ulster/Northern Ireland unresolved and sparked a civil war in the newly independent Irish Free State. In France and neutral Spain, the Catalans, Basques and Bretons were left out of the Wilsonian principle of the ‘self-determination of peoples’. And the application of that principle to non-European populations in the imperial peripheries and colonies was even more haphazard and ill-considered.

As Robert Gerwarth (Reference Gerwarth2016) reminds us, the armistice of 11 November 1918 did not end the hostilities of that war. Not only was there the standoff between Poland and Lithuania over the city of Vilnius, there were ongoing armed conflicts in Finland, between Greece and Turkey, in Ireland, in Fiume/Rijeka (where Gabriele D’Annunzio set up the first Fascist statelet of Europe), and around irregular militias in Germany’s lands and former possessions. Now Germany, Hungary and Turkey experienced their ‘culture of defeat’ and developed a rancorous nationalism that bitterly refused to come to terms with the indigestible truth: that the war had been lost.

1918 was the crowning achievement of many national movements in Europe. All the new nation-states of 1918–1920 benefited from the defeat of their former overlords and all of them could trace their emergence back to a nineteenth-century movement. And in all cases, that movement had begun with, and relied on, the cultural identity of the nation, its separate and authentic language, history and folk life as asserted in the crisis moments of Europe’s empires. As a political force, nationalism from 1805 on had failed and failed again, except in a few countries such as Greece and Belgium; but it failed better every time. As an outlook, it had indoctrinated and saturated all of Europe by 1900. That outlook held that the state should ideally be based on the sovereignty of the people; that that people should ideally be bonded by a common culture; and that therefore, as people with a common culture deserved a sovereign state of their own, each state should ideally be a nation-state, embody the nation’s essential identity and rest on the nation’s common culture: one state (and not more than one) for each nation. The political sovereignty of the state was derived from the unpolitical, cultural identity of the nation.

Even during the high point of 1848 and in the Polish Uprisings of 1831 and 1863, the mobilizing power of nationalism was limited to relatively small insurgency units aided by street barricades in the cities. After 1848, it became increasingly clear that real mobilizing power was wielded by social reformists and revolutionaries defined by class rather than by ethnicity, and that it was the state itself that could most successfully harness national sentiment to its armies and propaganda machinery. The influence of nationalism lay, then, less in its power to overthrow the state than in the ability to convince the state of its ideals. Nationalism wielded more influence than power; it shaped the outlook, the self-image and the institutions of existing and emerging states by persuasion rather than coercion, by cultural allure rather than clout, by bestowing charisma rather than by enforcing authority.