The brain and body are dynamically coupled: it is increasingly recognised that variant connective tissue, as exemplified by joint hypermobility, is associated with a spectrum of somatic symptoms, as well as neuropsychiatric and affective phenomena. Reference Sharp, Critchley and Eccles1 Joint hypermobility is a dominant characteristic of hypermobile Ehler’s Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) Reference Malfait, Castori, Francomano, Giunta, Kosho and Byers2 and related conditions, which are due to differences (variants) in connective tissue properties (generally related to extracellular matrix and collagen, resulting typically in laxity). Generalised joint hypermobility is defined as the ability to move multiple joints beyond the articular range expected for the general population, which can lead to chronic pain, and musculoskeletal injuries. Reference Juul-Kristensen, Østengaard, Hansen, Boyle, Junge and Hestbaek3 Joint hypermobility is also specifically associated with bipolar affective disorder. Reference Csecs, Dowell, Savage, Iodice, Mathias and Critchley4 A diagnosis of hEDS or HSD confers a relative risk of diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder of 2.7, although it is unclear precisely what mediates this association. Reference Cederlöf, Larsson, Lichtenstein, Almqvist, Serlachius and Ludvigsson5 Hypermobility appears to be more common in females than in males, and has a prevalence of 20% in the general population, Reference Mulvey, Macfarlane, Beasley, Symmons, Lovell and Keeley6 compared with an estimated 50% in people with a neurodevelopmental condition including autism and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Reference Csecs, Iodice, Rae, Brooke, Simmons and Quadt7 Symptoms of proprioceptive dysfunction (i.e. related to difficulties in position sense, such as those seen in dyspraxia) commonly occur in both joint hypermobility and autism and there is a strong familial relationship between these two conditions. Reference Glans, Thelin, Humble, Elwin and Bejerot8 Joint hypermobility is characterised by differences in sensory and emotional processing, which predispose to anxiety, which is associated with hypermobility. Reference Smith, Easton, Bacon, Jerman, Armon and Poland9 Here we will examine if neurodivergent characteristics are related to the association between joint hypermobility and bipolar affective disorder.

What is neurodivergence?

The term neurodivergence encompasses a spectrum of (often overlapping) neurodevelopmental conditions that include autism, ADHD and Tourette syndrome Reference Csecs, Iodice, Rae, Brooke, Simmons and Quadt7 among others. Neurodevelopmental conditions, which are also associated with hypermobility, Reference Csecs, Iodice, Rae, Brooke, Simmons and Quadt7 are typically expressed through differences in cognition, communication, behaviour and/or motor skills that are attributed to variant trajectories in the development of underlying brain systems, usually apparent from childhood. Reference Morris-Rosendahl and Crocq10 This paper seeks to avoid using ableist language in describing neurodivergent individuals and we refer to ‘autistic individuals’ instead of ‘patients with autism’. Reference Bottema-Beutel, Kapp, Lester, Sasson and Hand11 Autism spectrum conditions (‘autism’ in this paper) typically entail differences in social and emotional interaction, perception (with hypo- and hypersensitivities) and behaviour (often having focused interests and preference for routine). The prevalence of a co-occurring psychiatric illness in autistic individuals is estimated to be 70–95% in children and adolescents. Reference Mosner, Kinard, Shah, McWeeny, Greene and Lowery12 ADHD is observed in over 60% of autistic patients and these two conditions are thought to have an overlapping genetic basis underlying similar inheritance, with co-occurrence common in families. Reference Bottema-Beutel, Kapp, Lester, Sasson and Hand11 ADHD is characterised by pervasive differences in attention and concentration alongside tendencies to hyperactivity, impulsivity and, often, emotion dysregulation. Similarly to autism, ADHD features are usually identifiable in childhood. Reference Mayas13

The overlap of bipolar affective disorder, hypermobility and neurodivergence

Hypermobility is associated with bipolar affective disorder, Reference Cederlöf, Larsson, Lichtenstein, Almqvist, Serlachius and Ludvigsson5,Reference Csecs, Iodice, Rae, Brooke, Simmons and Quadt7 a relapsing-remitting psychiatric condition, typically first presenting in late adolescence and early adulthood. Hypermobility, a manifestation of variant connective tissue, is usually present from birth; individuals with hypermobility (a manifestation of variant connective tissue) may develop symptomatic hypermobility later in life. In this study we assess the presence of hypermobility itself rather than symptomatic hypermobility. Bipolar affective disorder is characterised by extremes of mood, with patients experiencing mania, hypomania, mixed affective or depressive mood states throughout the disorder’s course. Reference Culpepper14 The usual age at onset for bipolar affective disorder is in relatively early adulthood/late adolescence and its lifetime prevalence ranges between 1 and 2.4% depending on whether subthreshold forms of the disorder are considered. Reference Merikangas, Jin, He, Kessler, Lee and Sampson15 Bipolar affective disorder is associated with neurodevelopmental conditions. Reference Salvi, Ribuoli, Servasi, Orsolini and Volpe16,Reference Varcin, Herniman, Lin, Chen, Perry and Pugh17 Of adult patients with bipolar affective disorder, 10–30% are reported to have co-occurring ADHD, compared with 3–6% in the general adult population. Reference Salvi, Ribuoli, Servasi, Orsolini and Volpe16 Shared genetic factors are also suggested by increased occurrence of bipolar affective disorder and both ADHD and autism within the same families. Reference van Hulzen, Scholz, Franke, Ripke, Klein and McQuillin18 Symptoms of bipolar affective disorder and ADHD overlap; e.g. hypomanic episodes may mimic the hyperactive symptoms of ADHD. Reference Comparelli, Polidori, Sarli, Pistollato and Pompili19 Bipolar affective disorder also co-occurs with autism: the rate of bipolar affective disorder is reported to be up to six times greater in autistic, compared to non-autistic, individuals. More conservatively, the prevalence of bipolar affective disorder in autistic individuals is estimated to be 5–8%, compared with perhaps 2.6% in the general population. Reference Dunalska, Rzeszutek, Debowska and Brynska20 Genetic overlap is also observed between bipolar affective disorder and autism. Reference Rylaarsdam and Guemez-Gamboa21 Growing evidence, including from large genome wide association studies, points to the convergence of genetic susceptibility to both affective and neurodevelopmental conditions, e.g. Reference Wu, Cao, Baranova, Huang, Li and Cai22 in which Wu et al observe significant enrichment of overlapping genes among bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, ADHD, autism and depression and identified a panel of cross-disorder genes. Furthermore, it is reported that the single nucleotide polymorphism–based genetic correlation between ADHD and bipolar affective disorder is substantial, significant and consistent with the existence of genetic overlap between the two conditions. Reference van Hulzen, Scholz, Franke, Ripke, Klein and McQuillin23

An improved understanding of the relationships between bipolar affective disorder and neurodivergence may inform and improve patient care. In Box 1, we demonstrate the overlap between affective phenomenology as described in the Hypomania Checklist (HCL-32) Reference Angst, Adolfsson, Benazzi, Gamma, Hantouche and Meyer24 and neurodivergent characteristics. Importantly, patients with both bipolar affective disorder and ADHD have a more severe course of illness, with earlier onset, a shorter interval between episodes and a shorter time of euthymia Reference Nierenberg, Miyahara, Spencer, Wisniewski, Otto and Simon25 compared with those with bipolar disorder alone. Interestingly, numerous studies have already independently identified shared transdiagnostic features (e.g. anxiety, Reference Smith, Easton, Bacon, Jerman, Armon and Poland9,Reference Merikangas, Akiskal, Angst, Greenberg, Hirschfeld and Petukhova26 substance use Reference Merikangas, Akiskal, Angst, Greenberg, Hirschfeld and Petukhova26–Reference French, Daley, Groom and Cassidy28 and sleep disorders Reference Hvolby29,Reference Domany, Hantragool, Smith, Xu, Hossain and Simakajornboon30 ) with ADHD, autism, bipolar affective disorder and hypermobility.

Aims of this study

Studies have independently demonstrated the link between hypermobility and bipolar affective disorder, hypermobility and neurodivergence, and neurodivergence and bipolar disorder. Further investigation of the potential co-occurring nature of these conditions is required. We hope to examine systematically for the first time the nature of this relationship, because this could enhance understanding and inform clinical decision-making and practice. First, we hypothesised that the bipolar affective disorder group would show higher rates of both joint hypermobility and neurodivergent characteristics. Second, we hypothesised that this brain-body relationship between physical constitution (joint hypermobility) and subsequent psychiatric illness (bipolar affective disorder) would be mediated by linked developmental neurodivergent characteristics. The latter hypothesis was motivated by the growing evidence linking hypermobility with a spectrum of altered physiology, somatic symptoms as well as neurodevelopmental and affective phenomena, as described above. Thus hypermobility, within the mediation model, was hypothesised to be the predictor (X), bipolar affective disorder the outcome (Y) and neurodivergent characteristics the mediator (M).

Method

Study design and participants

We undertook a case-control study of 52 patients with a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder and 54 comparison participants. A priori sample size calculation was based on previous research, wherein the probability to detect likely autism in the bipolar affective disorder patient group was estimated at 21% (0.21), Reference Lugo-Marín, Magán-Maganto, Rivero-Santana, Cuellar-Pompa, Alviani and Jenaro-Rio31 and 2% (0.02) in the comparison group. Reference Chiarotti and Venerosi32 Applying an additional correction for continuity gave a total sample size of 108 (54 per group) to detect a moderate effect size of d = 0.45, with 80% power and significance level at 0.05 for an independent t-test.

Inclusion criteria were: aged ≥18 years, being fluent in reading and speaking English, and a clinical psychiatric diagnosis (i.e. not self-identification) for allocation to the bipolar affective disorder group, and not the comparison group. Exclusion criteria included: age <18 years and the presence of neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease. The presence of other psychiatric conditions was not excluded in both groups. Participants were recruited via the online platform Prolific. The recruitment consisted of a brief screening survey, after which only eligible participants were invited to take part in the study: i.e. bipolar affective disorder participants were screened twice: (a) only those Prolific users who had previously indicated to have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Screener ‘Chronic condition/illness – Bipolar Disorder’) were sent an invitation to the study and (b) all invited participants were asked ‘Do you have a diagnosis of the following?’, with answer options ‘Bipolar Type I (Bipolar Disorder with manic episodes)’, also known as ‘Bipolar Affective Disorder’, ‘Bipolar Type II (Bipolar Disorder with hypomanic episodes)’, ‘Rapid Cycling Bipolar Disorder’, ‘Cyclothymia’ or ‘Other Bipolar Condition’. Comparison participants were selected to match bipolar affective disorder participants using frequency matching by sex assigned at birth, ethnicity and level of education. Online consent was obtained from all participants. The survey was online and was identical for both groups aside from the section about bipolar affective disorder diagnosis. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013 (https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/). All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Brighton and Sussex Medical School Research Governance and Ethics Committee (ER/BSMS99VB/1).

Variables, data and statistical methods

The Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale (RAADS-R) was the main tool that we used to quantify the likely presence of autism in individual participants: RAADS-R is an 80-item questionnaire (useful for retrospective assessment of adults without general intellectual impairment) that elicits information regarding social difficulty, circumscribed interest, language and sensory-motor symptoms. The RAADS tool has excellent psychometric properties, with reported concurrent validity, sensitivity = 97%, specificity = 100% and test–retest reliability r = 0.987. Reference Ritvo, Ritvo, Guthrie, Ritvo, Hufnagel and McMahon33

The Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) was the primary tool that we used to assess the likelihood of ADHD in adults through retrospective screening of childhood symptoms. The WURS assesses multiple domains, including impulsivity, behavioural problems, inattentiveness, school problems, self-esteem and negative mood. A diagnosis of ADHD is likely if the WURS is ≥46. Reference Kouros, Hörberg, Ekselius and Ramklint34 A cut-off score of 46 or more correctly identifies 86% of the patients with adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and 99% of the non-ADHD subjects. Reference Ward, Wender and Reimherr35

The Five Part Questionnaire (5PQ) was used to assess self-reported generalised joint hypermobility (JH). This is a useful tool when examination is not practical. Reference Hakim and Grahame36 JH is considered likely if the answer to ≥2 questions relating to current and childhood hypermobile feature is ‘yes’. The conventional way to identify joint hypermobility is by a physical examination, scored according to the Beighton score. However, Beighton scoring can be time consuming in clinical practice and is often unfeasible in large population-based and online studies. The 5PQ was developed using the Beighton scale as a reference standard, with high sensitivity and specificity of 71–84% and 77–89%, respectively. Reference Hakim, Cherkas, Grahame, Spector and MacGregor37 The presence of a formal diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder was also recorded at the start of the survey.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS statistics v29 for macOS (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics). Binary variables were created denoting whether thresholds were met for a likely presence of autism, ADHD and joint hypermobility, based on the total RAADS score, total WURS score and the 5PQ, respectively. We tested for differences in the frequency of likely neurodivergence and joint hypermobility in the bipolar affective disorder group versus the comparison group. We also analysed data on previous formal diagnoses, and the group means of total RAADS, WURS and 5PQ (hypermobility) scores. We tested for possible confounding effects of demographic data including as age, sex assigned at birth, identified gender, ethnicity and ethnic origin. Group comparisons were undertaken using χ 2 and t-tests (threshold significance p < 0.05) A post hoc sensitivity analysis was performed relating to the prevalence of suspected autism. Age-corrected odds ratios for diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder were calculated using binary logistic regression for participants scoring above and below thresholds for autism, ADHD and joint hypermobility. Spearman correlations quantified the relationship between hypermobility (total 5PQ score) and autism (total RAADS), ADHD (total WURS) and bipolar disorder. We created also a composite neurodivergence score, derived from the averaged z-scores of the RAADS and WURS, which we used in a mediation analysis where bipolar affective disorder was the outcome and joint hypermobility was the predictor, quantifying the indirect effect of neurodivergent characteristics on the relationship between these physical and psychiatric variables. This mediation analysis was performed using PROCESS v4·2 for SPSS (http://www.processmacro.org) by Hayes Reference Hayes38 and controlled for age as this was a potential effect modifier. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals were used, and the effect was considered significant if confidence intervals did not cross zero.

Results

Participants

The initial study sample consisted of 108 individuals: a case group of 54 with bipolar affective disorder and 54 comparison participants. Two of the participants in the bipolar affective disorder group had to be excluded from the study because they answered ‘no’ to a question asking whether they had bipolar affective disorder. Therefore, only 52 individuals with bipolar affective disorder and 54 comparison participants were included in the analyses.

Descriptive data, outcome data and main results

Demographic data

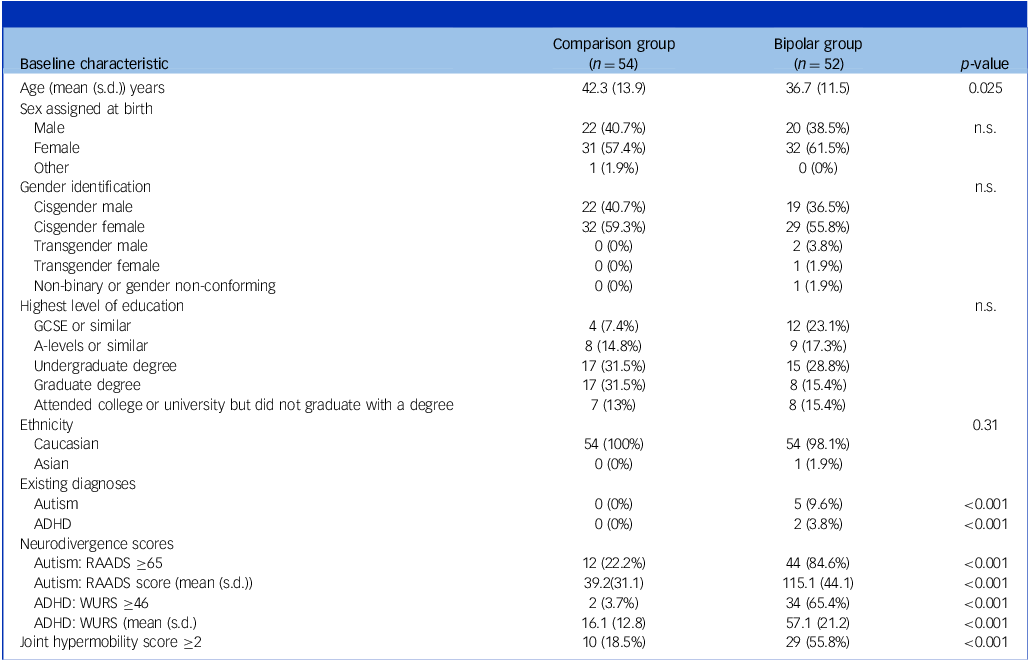

Demographic characteristics were measured (see Table 1). The mean age (±s.d.) of the bipolar affective disorder group was 36.7 (± 11.5) years and in the comparison group it was 42.3 (± 13.9) yrs. This was a statistically significant difference and, therefore, age was considered as a confound when conducting further analyses. χ 2 tests revealed no significant difference between the bipolar affective disorder and comparison group for gender assigned at birth (p = 0.59), gender identity (p = 0.36), ethnicity (p = 0.31) or highest level of education (p = 0.11). The demographic data and the data of interest were complete for all study participants.

Table 1 Summary of demographics and results, showing significant differences between the groups

n.s., not significant; GCSE, General Certificate of Secondary Education; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; RAADS, Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale; WURS, Wender Utah Rating Scale.

Prevalence and odds ratios of joint hypermobility, neurodivergence and bipolar affective disorder

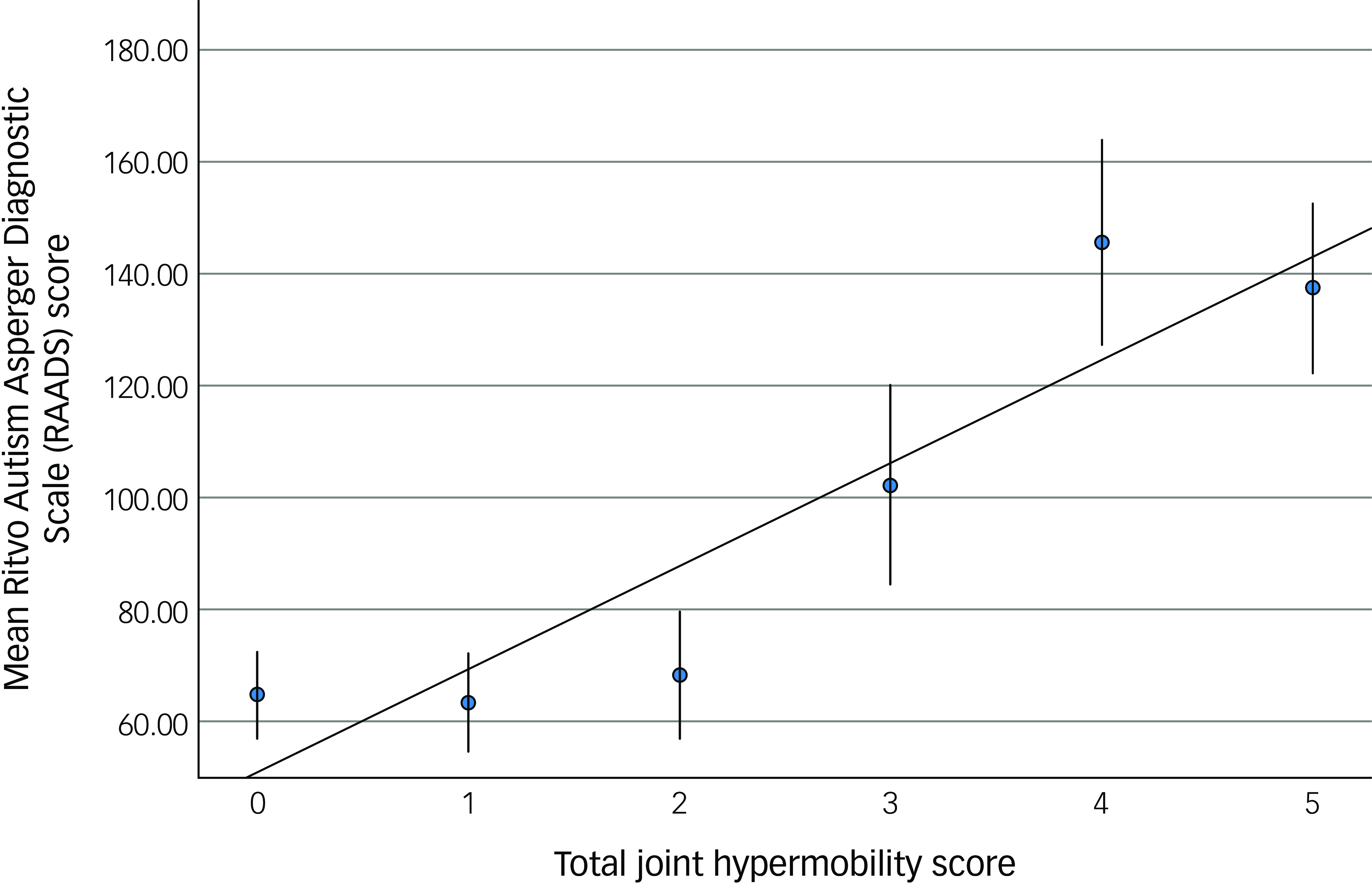

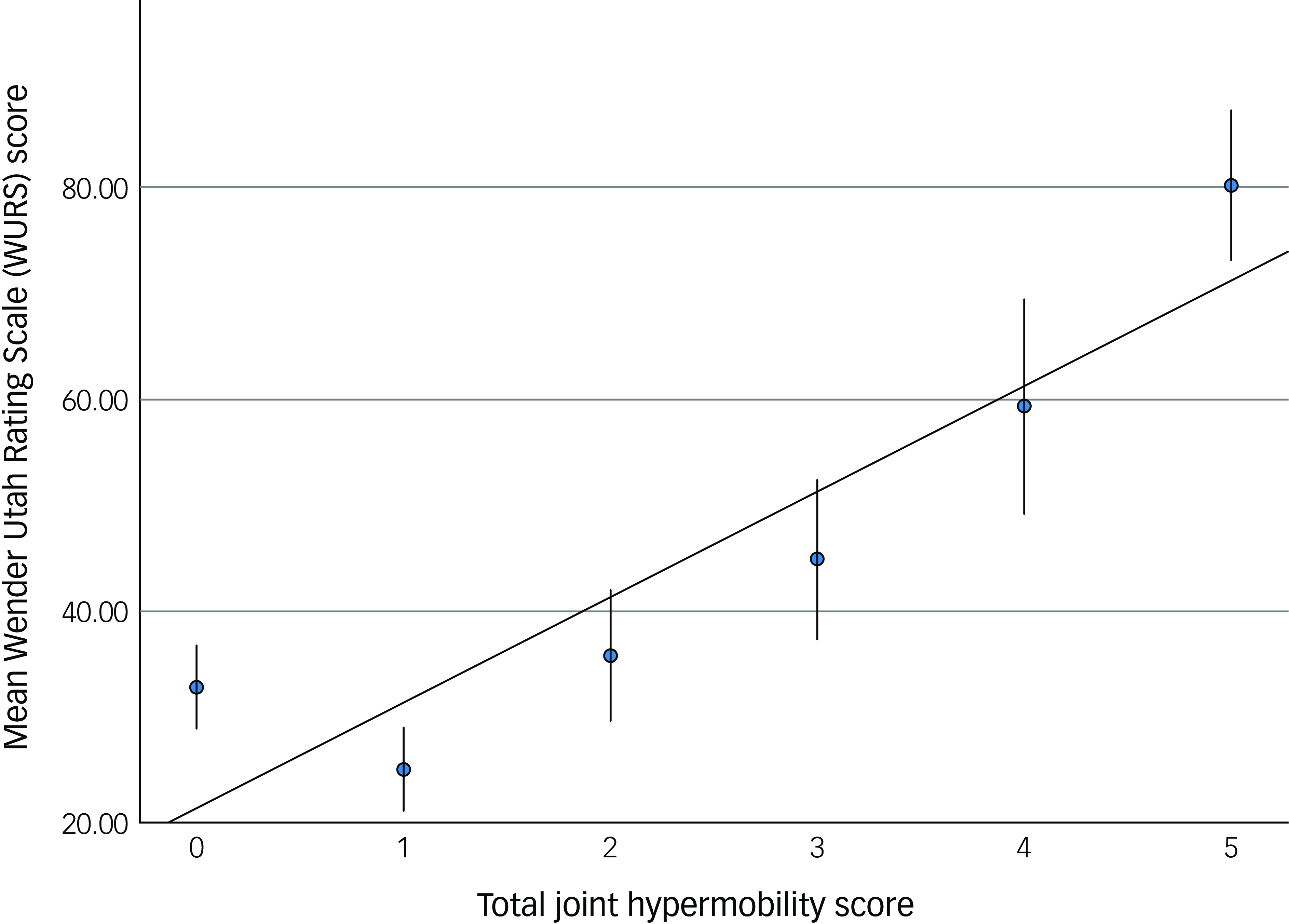

The bipolar affective disorder group comprised significantly more individuals scoring above the threshold for generalised joint hypermobility (29/52; 55.8%), compared with the comparison group (10/54; 18.5%, ӽ 2 = 15.8, p = <0.001). The presence of likely generalised joint hypermobility thus predicted the presence of bipolar affective disorder (odds ratio 5.1; 95% CI = (2.1, 12.4)). The hypermobility score was significantly correlated with both autistic characteristics (RAADS) (r s = 0.33, p < 0.001, Fig. 1) and ADHD characteristics (WURS) (r s = 0.29, p < 0.003, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 The relationship between joint hypermobility score and autism characteristics. Error bars demonstrate one s.e. of the mean.

Fig. 2 The relationship between joint hypermobility score and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) characteristics. Error bars demonstrate one s.e. of the mean.

The bipolar affective disorder group included five individuals with existing diagnoses of autism and two with existing diagnoses of ADHD. This was higher than the comparison group which contained no individuals with formal diagnoses of either autism or ADHD. The bipolar affective disorder group scored significantly higher than the comparison group for autistic traits (total RAADS; mean (± s.d.) = 115.7 (± 44.1) v. 39.2 (±31.1); t = 10.3, p < 0.001) and for ADHD traits (mean WURS (±s.d.) = 57.1 (± 21.2) v. 16.1 (± 12.8); t = 12.0, p < 0.001) and for a composite measure (pooled z score) of neurodivergent features derived from RAADS and WURS scores: bipolar group (z score; mean (± s.d.) = 0.74 (± 0.69), comparison group p = −0.74 (± 0.47), (t = 12.9, p = 0.001). Autistic and ADHD characteristics were highly correlated, r s = 0.77, p = <0.001.

The (age-corrected) odds of having a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder were 18.2 (95% Cl = 6.7, 49.4) times greater in those meeting the threshold for likely autism and 46.9 (95% CI = 10.0, 220.7) times greater for those meeting the threshold for likely ADHD.

Mediation analysis

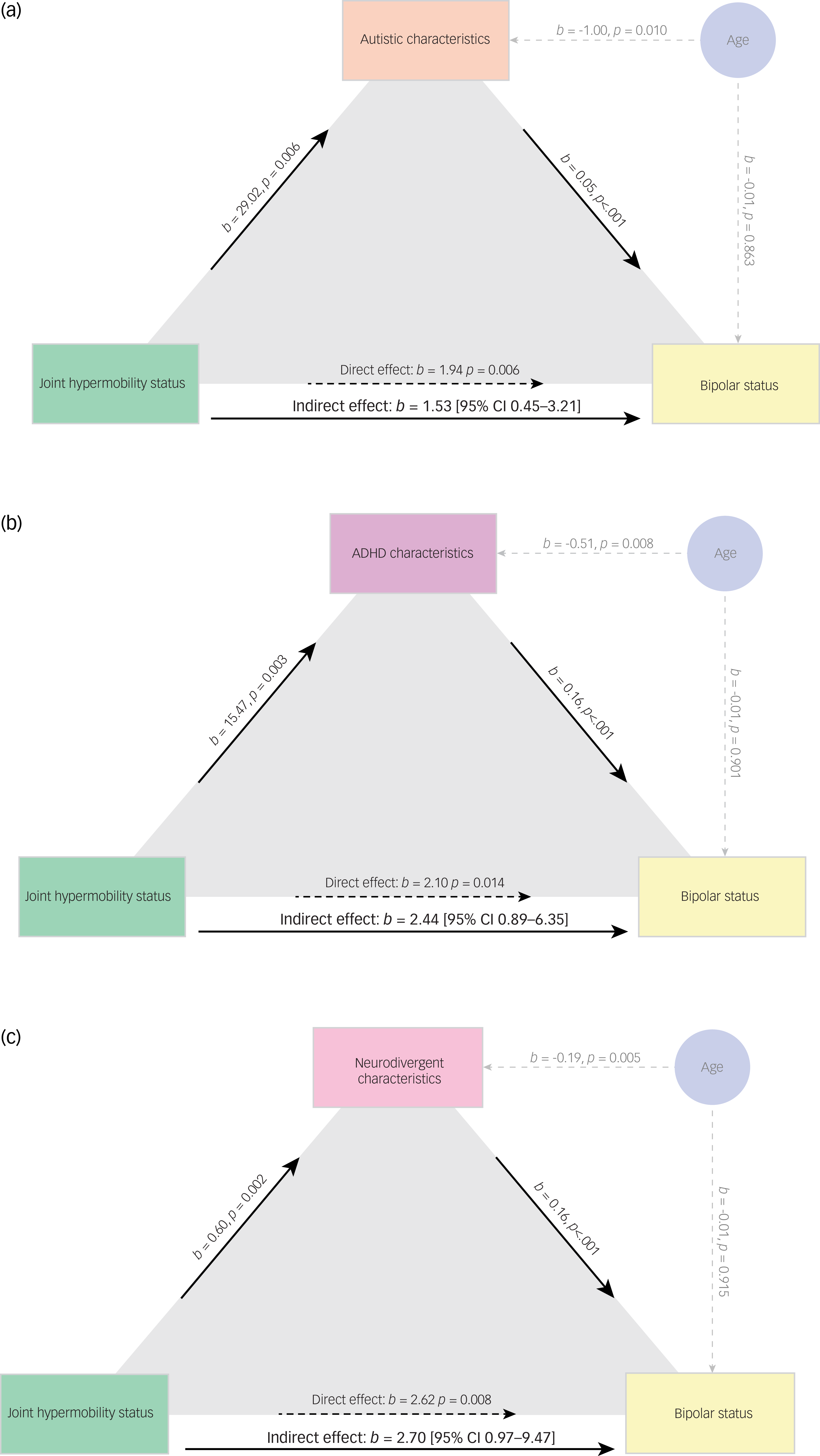

We undertook mediation analyses to test sequentially whether first autistic characteristics (Fig. 3(a)), then ADHD characteristics (Fig. 3(b)) mediated the relationship between the presence of joint hypermobility and bipolar affective disorder.

Fig. 3 Mediation models showing the mediating effects of autistic (a), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (b) and pooled neurodivergent characteristics (c) on the relationship between the presence of joint hypermobility and bipolar affective disorder. Analysis is corrected for age.

Last, we tested whether pooled neurodivergent characteristics mediated this relationship (Fig. 3(c)). Controlling for age, we showed that autistic characteristics mediated the relationship between the presence of hypermobility and bipolar disorder (estimate of indirect effect 1.53, 95% CI 0.45, 3.21) as did ADHD characteristics (estimate of indirect effect 2.44, 95% CI 0.89, 6.35). The composite measure of neurodivergence significantly mediated the relationship between physical features (hypermobility) and psychiatric diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder: the estimate of an indirect effect was 2.70, bootstrapped 95% CI (0.97, 9.47)); all mediations were considered significant as 95% confidence intervals did not cross zero. It must be noted that we have used standardised scores in Fig. 3(c) and thus it is not possible to make a direct numerical comparison of the magnitude of indirect effects across differently scaled models.

Discussion

Key results and interpretation

We demonstrate that a physical index of variant connective tissue (joint hypermobility), predicts a psychiatric diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder, with an odds ratio of 5.1, adding to the existing, albeit small, literature describing this association. This is of particular importance because screening patients with bipolar affective disorder for hypermobility may enhance understanding of the interplay between their mental and physical health concerns. It also potentially suggests an opportunity for screening and early intervention for mood disorder in those identified as hypermobile.

Furthermore, within this brain-body model, we show the strong association between bipolar affective disorder diagnosis and the presence of neurodivergent characteristics (autism and ADHD). Notably, among patients with bipolar affective disorder, more than four out of five scored above the screening threshold for autism, and two-thirds above the threshold for ADHD, compared with the comparison group where one in five scored above the threshold for autism and one in twenty-five for ADHD; very few cases had been previously identified.

Our mediation analysis suggests that the link between hypermobility and bipolar affective disorder is potentially explained by the presence of neurodivergent characteristics. This invites discussion and further investigation into a putative mechanism for affective pathophysiology, through developmental characteristics associated with hypermobility: i.e. the association between hypermobility and bipolar affective disorder is, in part, linked through neurodivergence, that the link between hypermobility and bipolar affective disorder may be concentrated in neurodivergent individuals, or indeed accounted by for by neurodivergence.

Our findings extend a growing evidence base for an association between bipolar affective disorder and variant connective tissue, Reference Cederlöf, Larsson, Lichtenstein, Almqvist, Serlachius and Ludvigsson5,Reference Csecs, Iodice, Rae, Brooke, Simmons and Quadt7 and highlight the value in routinely considering the presence of hypermobility and neurodevelopmental conditions in the evaluation and formulation of patients presenting with affective disorders and vice versa. Our data suggest that this is often overlooked, with patients therefore being potentially misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed. Among the patients we surveyed with established bipolar affective disorder, only 10% had an existing diagnosis of autism and only 4% an existing diagnosis of ADHD. Together, this data invites a potential paradigm shift in our understanding of these conditions.

Identifying bipolar affective disorder can often be challenging. It is both commonly viewed within psychiatry as a severe and enduring mental illness with often major consequences on functioning and quality of life. While current treatments may ameliorate symptoms they rarely lead to complete resolution and can be associated with considerable side-effects. Bipolar affective disorder is around 6 times higher in autistic compared with non-autistic individuals and an estimated 10–20% of adult patients with bipolar affective disorder may have co-occurring ADHD, almost 3 times higher than the general population. Reference Salvi, Ribuoli, Servasi, Orsolini and Volpe16 Shared genes contribute to these associations which are further blurred by evidence that up 60% of autistic patients have ADHD. Reference Davis and Kollins39

What does our study add?

Our study demonstrates the interlinked nature of joint hypermobility, bipolar disorder and neurodivergence. Our mediation analysis suggests a possible causal role, perhaps grounded on an underlying brain-body mechanism (e.g. a nervous system connected to the body and outside world via variant connective tissue predisposes to neurodivergence, including autonomic and somatosensory processes) in bipolar affective disorder that may unify these features, for example, see our model linking emotion regulation in neurodivergent people to the sensory impact of joint hypermobility. Reference Eccles, Quadt, Garfinkel and Critchley40 While future, larger, longitudinal studies are needed to confirm this possible relationship, it highlights the need to consider the broader concept of neurodivergence (including both ADHD and autism). An evidence base is growing that suggests co-occurrence of neurodevelopmental conditions (as is often seen in clinical practice) is the norm rather than the exception.

Based on this, we propose an explanatory model: many disorders or illnesses occur when stress exceeds the threshold of tolerance or capacity for adaptive recovery – the concept of allostatic load. Reference McEwen41 Moreover, some individuals may be uniquely vulnerable to particular stressors. Diathesis (from the Greek for predisposition or sensibility) were considered inherent, stable characteristics. Traits remain latent until provoked and exposed by stressors, leading to altered mental states. For instance Gajwani and Minnis, in their double jeopardy model, Reference Gajwani and Minnis42 explore the intersection between adverse childhood experiences and neurodevelopmental conditions. They describe how combined interplay between genetic predisposition and the environment enhances vulnerability to mental ill-health, emphasising how conditions previously considered mutually exclusive (trauma and neurodivergence) interact and are more likely to co-occur.

Speculatively, joint hypermobility is associated with lower affective regulatory capacity and less stable self-integrity through lower predictive precision in proprioceptive (increased variance of bodily postures) and interoceptive (dysautonomia from dynamic cardiovascular differences) control consequent to systemic expression of variant connective tissue. Reference Eccles, Quadt, Garfinkel and Critchley40 More generally, sensory predictive imprecision may account for the sensory processing features of neurodevelopmental conditions. Our study provides motivation for further empirical investigation, and potential avenues for possible intervention, such as interoceptive training, which our group is actively investigating. We first confirmed efficacy in reducing anxiety in autistic individuals and then trialled interoceptive training in reducing anxiety in hypermobile people and now we are looking to assess the feasibility of self-administered interoceptive training across diagnostic groups. Reference Takaesu43

To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly explore these potential brain-body influences together in the aetiology of bipolar affective disorder. Nevertheless, there remains an epistemological difficulty with current discrete diagnostic constructs in psychiatry. Our observations here add further support to pursuing a dimensional approach linking neural processes to diagnosis, such the RDOC criteria Reference Takaesu43 and trans-diagnostic consideration of neurodevelopmental features, for example, as described in the Early Symptomatic Syndrome Eliciting Neurodevelopmental Clinical Examinations framework. Reference Gillberg44 This is further complicated by the observation that, in bipolar affective disorder, the distinction between recurrent episodic conditions, residual or reactive symptoms and lifelong trait conditions is not clear cut.

The association between joint hypermobility and anxiety is well established Reference Smith, Easton, Bacon, Jerman, Armon and Poland9 and recognition of the link with neurodivergence is gaining momentum. In this context, the present study is the first to explore explicitly how hypermobility may predict bipolar affective disorder through neurodivergent traits. Consequently, this provides a novel perspective, with exciting, previously unconsidered clinical and scientific implications. It places the links between body and brain centre stage, in terms of both co-occurrence and possible aetiology.

We recognise that the ability to generalise the data is limited from this relatively small, internet-based study (which may confer bias, especially from using an online recruitment service like Prolific), however the prevalence of joint hypermobility in the comparison group is consistent with established general population figures. Larger, systematic studies are needed. Given this was a retrospective observational study we cannot confirm a temporal relationship, although the WURS, the RAADS-R and even the 5PQ joint hypermobility questionnaire include childhood features, which other ADHD/autism screening instruments often do not. The WURS specifically probes childhood rather than adult features; however, its robustness in the adult population has been demonstrated. Reference Gift, Reimherr, Marchant, Steans and Reimherr45 However, the study did not include a comprehensive diagnostic assessment of these conditions (autism, ADHD and hypermobility) and relied on reported clinical diagnoses of bipolar affective disorder; it was not possible to verify medical records. It is also very possible that those using platforms such as Prolific are not generalisable. Future larger studies would benefit from systematic clinical diagnostic evaluation for all diagnoses, more comprehensive investigation of general population prevalence and a larger sample size powered primarily for a mediation analysis.

Although we recognise these limitations, the design of this study was pragmatic, allowing us to draw statistical inference to inform a conceptual model.

What does this mean for the future?

Understanding the importance of these associations will lead to better recognition of often missed co-occurrences. More detailed understanding of the interplay of these commonly co-existing physical and psychological factors will enhance clinical practice.

Future research would involve replication of these findings, more specific examination of these theories and potential interrogation of longitudinal cohorts. This study has significant implications for both service and care delivery, highlighting the need to raise recognition of the importance of neurodiversity in healthcare and also integrate mental and physical care in this group. 46 Patients frequently fall through gaps in these often-isolated care groups. Bridging these gaps has huge potential for future patient benefit and scientific understanding.

Box 1 Overlap between hypomanic symptoms and neurodivergence using items from the HCL-32

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, J.A.E.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation – H.D.C., L.Q., J.A.E. Resources – L.Q. Investigation – E.B., L.Q., J.A.E. Formal analysis – E.B., L.Q., J.A.E. Writing (original draft) – E.B., J.A.E., C.S.M.-P. Writing (review and editing) – E.B., L.Q., C.S.M.-P., R.D., A.C., H.D.C., J.A.E.

Funding

Brighton and Sussex Medical School. J.A.E. was supported through an MQ transforming mental health/Versus Arthritis Fellowship (MQF17-19).

Declaration of interest

J.A.E. is the Chair of the Royal College of Psychiatrists Neurodevelopmental Psychiatry Special Interest Group and a member of the Clinical Reference Group for the UK ADHD Taskforce. The other authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Transparency declaration

We affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported, that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.