Across cultures, people display a wide range of philanthropic behaviors, including cooperating in public good games (Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, Boyd, Bowles, Fehr, Camerer and Gintis2004), benefitting others through volunteering (Ruiter and De Graaf Reference Ruiter and De Graaf2006), giving money (Borgonovi Reference Borgonovi2008) and helping strangers (Bennett and Einolf Reference Bennett and Einolf2017). Research thus shows that philanthropic behavior is—at least to some extent—universal. Research across different disciplines also supports the idea that there is some universality in the individual motivations for this behavior. Aknin et al. (Reference Aknin, Barrington-Leigh, Dunn, Helliwell, Burns and Biswas-Diener2013) show that people across cultures experience a “warm glow” of giving. This is supported by the recent meta-analyses of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies on altruistic and strategic decisions to give by Cutler and Campbell-Meiklejohn (Reference Cutler and Campbell-Meiklejohn2019): When contributing to others, areas in the brain related to reward processing light up. In another recent meta-analyses, Thielmann, Spadaro and Balliet (Reference Thielmann, Spadaro and Balliet2020) show the influence of personality traits on prosocial behavior and conclude that traits related to the unconditional concern of others’ welfare (such as social value orientation, altruism, concern for others and empathy) are more strongly correlated with prosocial behavior in economic games.

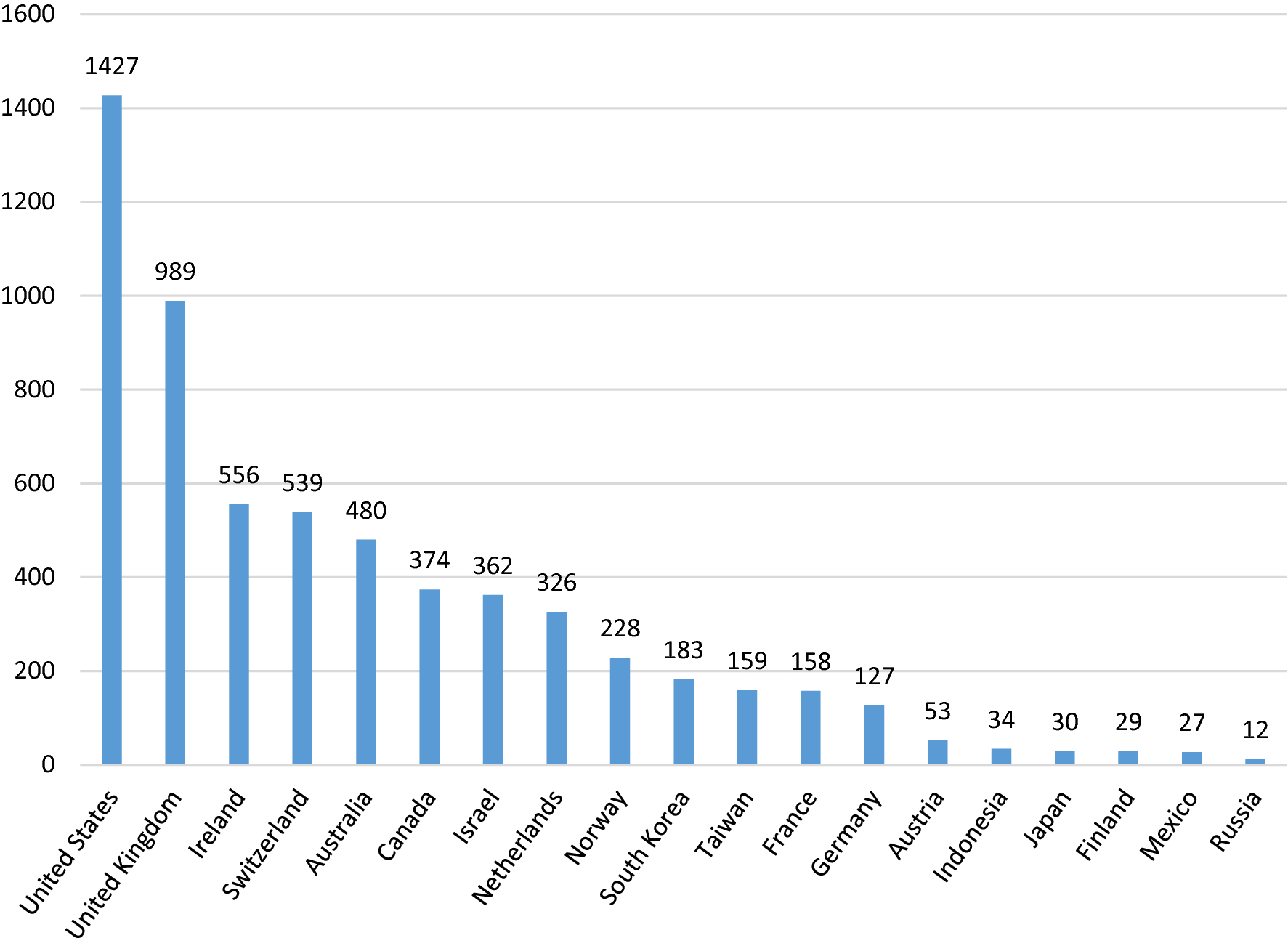

However, research also shows large variation across countries and cultures in different types of philanthropic behaviors. Take as an example the average amounts people donate to charitable causes across a range of nineteen countries, as displayed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Average donations in US dollars to charitable causes by people in nineteen countries

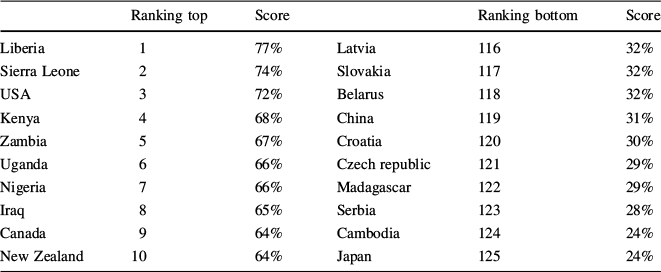

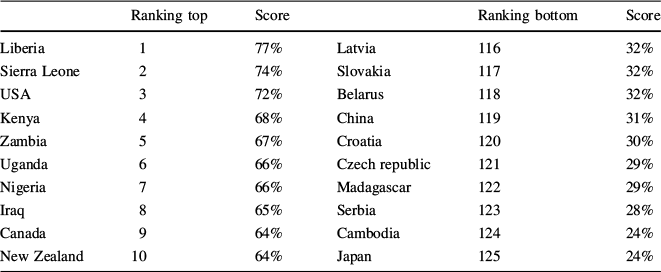

The average amounts people donate to charitable causes range from 1427 US dollar in the USA to the equivalent of 12 US dollar in Russia. To take another measure, the percentage of people in a country helping a stranger, as displayed in Table 1.

Table 1 Percentage of people helping a stranger in the past four weeks—top 10 and bottom 10 countries

Ranking top |

Score |

Ranking bottom |

Score |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Liberia |

1 |

77% |

Latvia |

116 |

32% |

Sierra Leone |

2 |

74% |

Slovakia |

117 |

32% |

USA |

3 |

72% |

Belarus |

118 |

32% |

Kenya |

4 |

68% |

China |

119 |

31% |

Zambia |

5 |

67% |

Croatia |

120 |

30% |

Uganda |

6 |

66% |

Czech republic |

121 |

29% |

Nigeria |

7 |

66% |

Madagascar |

122 |

29% |

Iraq |

8 |

65% |

Serbia |

123 |

28% |

Canada |

9 |

64% |

Cambodia |

124 |

24% |

New Zealand |

10 |

64% |

Japan |

125 |

24% |

Table 1 shows that there is large variation across countries in the percentage of people who report to have helped a stranger in the past four weeks. People in Liberia, Sierra Leone and the USA most often report to have helped a stranger, while people in Serbia, Cambodia and Japan least often report this behavior (CAF 2019; GWP 2018).

While there is apparent evidence that philanthropic behavior and the motivations for this behavior are at least to some extent universal, there is also evidence that people across the world do not equally display these types of behavior. How can we explain these differences in philanthropic behavior worldwide? And, more importantly, what can we learn from this? If research better understands why people differ in the display of philanthropic behaviors across different countries and cultures, it can make important contributions to society: It could support the development of societies where people are more inclined to display philanthropic behaviors and benefit others and the public good.Footnote 1 In this article, I will demonstrate that three problems intrinsic to the current study of global philanthropy—geographical orientation, connotations and definitions—are limiting the contribution of our field to society.

In a recent overview of the social bases of philanthropy, Barman (Reference Barman2017) examines the micro-, meso- and macro-level explanations for philanthropy. She defines philanthropy as “private giving for public purposes” (Barman Reference Barman2017, p. 272). Her conclusion is that in the literature, much knowledge has accumulated about the “characteristics, traits and roles of actors” (micro-level), and the “embeddedness in dynamic and changing social relationships” (meso-level) of philanthropic behavior (Barman Reference Barman2017, pp. 277–278). However, she concludes that the study of the macro-level, the embeddedness of donors “in broader societal configurations that encourage or constrain charitable giving,” is limited and in need of further development (Barman Reference Barman2017, pp. 280–281).

I echo her call for the development of the macro-level study of philanthropy, as I believe it is the lack of macro-level research in philanthropy that is limiting the contribution of our field to society. We need to better understand, measure and explain the variation in philanthropic behavior in all its forms across geographical units, and only then, we can contribute to evidence-based interventions to stimulate philanthropic behavior leading to improved societal outcomes.

Across the world, governments, corporations and civil society organizations are continuously implementing new policies, rules and regulations which change the context for philanthropic behaviors. These interventions are rarely evaluated. Think for example about the changes in laws that are made each year across countries, for example leading to more restrictive environments for civil society organizations (CIVICUS 2019; IU Lilly Family School of Philanthropy 2018). Consider the many changes in fiscal incentives for giving to charitable organizations (CAF 2016; Dehne et al. Reference Dehne, Friedrich, Nam and Parsche2008). Also relevant here are (fiscal) policies influencing the billions of dollars that are sent home yearly by migrants through remittances, not only to support their own nuclear families, but also their more distant kin and communities (Adelman et al. Reference Adelman, Barnett and Riskin2016; Moreno-Dodson et al. Reference Moreno-Dodson, Mohapatra and Ratha2012; Tertytchnaya et al. Reference Tertytchnaya, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018). And as a final example consider the blood and organ donation collection regimes that influence donation rates across countries (Gorleer et al. Reference Gorleer, Bracke and Hustinx2020; Healy Reference Healy2000; Johnson and Goldstein Reference Johnson and Goldstein2003). These are all examples of how the macro-level, the contextual level, influences individual philanthropic behaviors.

We also know very little about how demographic, economic and social changes influence philanthropic behaviors across geographical contexts (IU Lilly Family School of Philanthropy 2018). It would be of great relevance to also better understand and predict the influence of aging populations, economic downturns, increasing wealth inequality, secularization, technological developments and human-made and natural disasters on philanthropic behavior outside Western Europe and North America, to name a few significant developments at the societal level.Footnote 2

There are good reasons for the underdevelopment of the macro-level study of philanthropy. In the next section of this article, I will set out some of the current barriers and challenges that I contend researchers are facing in the global study of philanthropy, and offer suggestions for solutions to overcome these issues to enable further development of this research field. I contend there are three large problems with the global study of philanthropy: the problem with geographical orientation, the problem with connotations and the problem with definitions.

The Problem with Geographical Orientation

Figure 2 shows the geographical distribution of articles in the field of nonprofit studies published in 19 academic journals, as shown by Ma and Konrath (Fig. 7 in Ma and Konrath Reference Ma and Konrath2018, p. 1146). The darker the color, the more articles originated from that country. Here you can clearly see that most articles originate from North America, Western Europe, Australia and India. While the inclusion of India in the figure from Ma and Konrath seems encouraging for the representation of countries in nonprofit studies, the statistics for two key journals in our field: Voluntas and the Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly (NVSQ), are less hopeful. In 2017, 71% of the articles published in Voluntas and 84% of those published in NVSQ originated from either North America or Western Europe.Footnote 3 The lack of geographical representation of scholarly research on philanthropy is problematic, because this leads to a unidimensional North American or Western European view of what is “philanthropy” and consequently which countries are “more philanthropic.” And as a result, research and policy interventions are mostly based on this view.

Fig. 2 Geographical representation of publications in nonprofit studies, based on authors’ affiliation

There are many barriers for scholars studying geographical units outside North America and Western Europe, including lack of geographically diverse representation on editorial boards, lack of reviewers with local geographical and cultural knowledge, different frames and paradigms for academic research and publications, commercial presses and their paywalls, a constant requirement to compare and contrast with the situation in the USA, and the lack of high-quality, valid and reliable quantitative data.Footnote 4 In particular, this last barrier is an important limiting factor for the global study of philanthropy (Bekkers Reference Bekkers, Meuleman, Kraaykamp and Wittenberg2016). To collect the high-quality quantitative data needed to publish in academic journals is very difficult and especially costly in contexts outside North America and Western Europe. In addition, there are only a few quantitative data sources that allow for the comparative study of philanthropic behaviors, including the publicly available Eurobarometer (EB 2004), World Values Survey (WVS 2005), European Social Survey (ESS 2003), Individual International Philanthropy Database (IIPD Reference Wiepking and Handy2016) and the costly Gallup World Poll (GWP 2018). All but the GWP and the IIPD rely on data collected almost two decades ago, and only the GWP and the WVS provide a global sample. In addition, there are intrinsic problems with these existing quantitative data sources, which I will elaborate on in the section covering the problem with definitions later in this article.

The Problem with Connotations

The second problem I want to discuss relates to connotations that people have with the word “philanthropy,” which is used in most of the published research. For many people across the world, including Western Europe and North America, philanthropy is associated with “rich, white men giving away their money—and not always for charitable reasons” (Herzog et al. Reference Herzog, Strohmeier, King, Khader, Williams and Goodwin2020, p. 463). When thinking about philanthropy, for many people images of historical figures such as Carnegie and Rockefeller or more recent philanthropists such as Bill Gates and Warren Buffet come to mind. As women in the video “Who is a philanthropist?” from the Women’s Philanthropy Institute fittingly state: “People [philanthropists] are viewed as needing to be rich, multi-billionaires, millionaires, famous people”, “‘Philanthropist’ has a connotation of old white men”, and “philanthropists [are] rich, wealthy, who are on tv, run an organization, not just a regular person” (Women’s Philanthropy Institute 2019).

Figure 3 shows a painting nicknamed “The Mayor of Delft,” a painting by Dutch painter Jan Steen, which to me is one of the most intriguing philanthropy paintings from my country, the Netherlands. You see a burgher, which is a title for an upper class citizen in Jan Steen’s time, and his daughter, who in the most careless way give a donation to a poor lady and her son. Why would someone want to be depicted like that? This image is not that of the typical Maecenas. But it is illustrative for how many people see philanthropy and philanthropists, and the connotations they have with these words.

Fig. 3 Adolf en Catharina Croeser aan de Oude Delft, Jan Steen (1655). Location: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, the Netherlands

To connect this article with the recent critiques of philanthropy in the USA (Callahan Reference Callahan2017; Giridharadas Reference Giridharadas2018; Reich Reference Reich2018; Villanueva Reference Villanueva2018) and older critiques of philanthropy in Europe (Lassig Reference Lassig and Adams2004; Owen Reference Owen1965; Rodgers Reference Rodgers1949; Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1972), there are many issues with that kind of philanthropy. Although, at the same time, there are a great many “Big Philanthropists” out there who do genuinely care for others and are committed to contribute to improved societal outcomes (Breeze Reference Breeze2019; Buchanan Reference Buchanan2019).

The Problem with Definitions

The final and probably most important and complicated problem I want to discuss relates to definitions. The problem with the definition of philanthropy also reflects the problems with geographical orientation and connotations. And although several scholars have made excellent contributions to different cultural—and more inclusive—definitions of philanthropy, including Salamon and Anheier (Reference Salamon and Anheier1992, Reference Salamon and Anheier1998), Payton and Moody (Payton Reference Payton1988; Payton and Moody Reference Payton and Moody2008), Sulek (Reference Sulek2010a, Reference Sulekb), Butcher and Einolf (Reference Butcher and Einolf2017), Campbell and Çarkoğlu (Reference Campbell and Çarkoğlu2019), Bies and Kennedy (Reference Bies and Kennedy2019), Fowler and Mati (Reference Fowler and Mati2019) and Schuyt (Reference Schuyt2020), I believe much more global research is needed to inform a truly inclusive and comprehensive discussion of the global definition of philanthropy and of how different disciplines have coined this term in different national, cultural or language contexts. Fowler and Mati put the problem with definitions really well: “[…] from a global perspective, comprehension of philanthropy is biased and incomplete, calling for a more open understanding of the phenomena” (Fowler and Mati Reference Fowler and Mati2019, p. 724). To solve the issue with a global definition of philanthropy, I argue we first need to conduct large-scale comparative qualitative research into the conceptualization, meaning and understanding of philanthropy on a global scale. At the end of this article, I will share strategies for how I believe scholars can contribute to this.

In the meanwhile, because of the unidimensional North American and Western European view in the literature of what “philanthropy” is, philanthropy is typically defined in line with Payton, as “voluntary action for the public good” (Payton Reference Payton1988, p. 7). And it is often operationalized as formal philanthropic giving, financial donations to charitable organizations. This is exactly what is done in one of the few existing datasets available for the comparative study of philanthropic behavior, the Individual International Philanthropy Database (IIPD Reference Wiepking and Handy2016). The IIPD was created through the merge and synchronization of existing representative micro-level surveys. Researchers voluntarily contributed their data to create a comparative database including the incidence and amount people donated to charitable organizations in nineteen countries (Wiepking and Handy Reference Wiepking and Handy2016). As such, it is the first, and so far only, comparative data that include the amounts of money that people give to charities, which is of high relevance when studying how the macro-level context relates to individual-level philanthropic behavior (see for analyses using the IIPD De Wit et al. Reference De Wit, Neumayr, Handy and Wiepking2018; Wiepking et al. Reference Wiepking, Handy, Park, Neumayr, Bekkers and Breeze2020). However, as I mentioned, there are intrinsic problems with existing datasets like the IIPD. The first and foremost problem is the operationalization of philanthropic behavior only as formal philanthropic giving: monetary donations to charitable organizations. This behavior is largely dependent on the opportunity to give to formal charitable organizations, which is related to—among others—the local institutionalization of these organizations, and the trust people have in them (Campbell and Çarkoğlu Reference Campbell and Çarkoğlu2019; Fowler and Mati Reference Fowler and Mati2019; Wiepking and Handy Reference Wiepking, Handy, Wiepking and Handy2015a; Yasin Reference Yasin2020). In addition, the IIPD only covers a selective range of countries, predominantly in Western Europe, North America and Asia, and the data have been collected using different methodologies across different time frames.Footnote 5

In addition to the IIPD, the Gallup World Poll (GWP 2018) also illustrates the intrinsic problems with existing comparative data sources. Like the IIPD, the GWP uses limited definitions and consequently problematic operationalizations of philanthropic behavior. In the GWP, between 2009 and 2018 representative samples of between 120 and 150 countries in the world were asked the following three questions annually:

Have you done any of the following in the past month?

• Helped a stranger, or someone you didn’t know who needed help?

• Donated money to a charity?

• Volunteered your time to an organization?

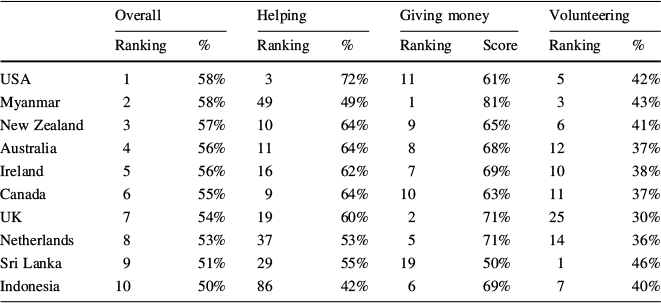

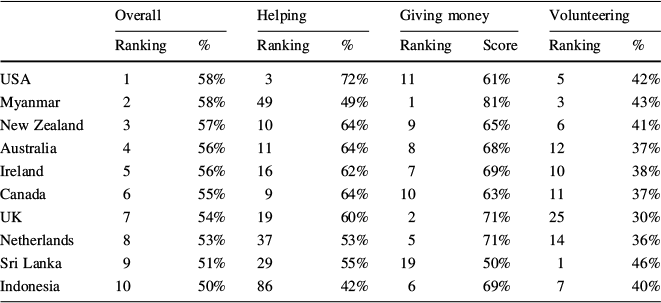

There are several issues with using these questions as a proxy for philanthropic behavior. These issues relate to the already mentioned cultural differences in definitions and differences in the opportunity of displaying these three behaviors, but also to language barriers; cultural differences in reporting of these behaviors; and the use of different time periods of reporting in the GWP, including local and religious holidays that correspond with higher giving, volunteering and helping. It is quite problematic that the Charitable Aid Foundation (CAF) uses aggregated data from the GWP to compare and rank countries in terms of “their generosity” in their World Giving Index (CAF 2019). It is no coincidence that the top 10 highest ranking countries consistently include predominantly English language countries. This is illustrated in Table 2 with the overall ranking of countries in the CAF Giving Index over the past ten years (CAF 2019).

Table 2 The world’s highest ranking countries in the CAF Giving Index—10-year trends

Overall |

Helping |

Giving money |

Volunteering |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ranking |

% |

Ranking |

% |

Ranking |

Score |

Ranking |

% |

|

USA |

1 |

58% |

3 |

72% |

11 |

61% |

5 |

42% |

Myanmar |

2 |

58% |

49 |

49% |

1 |

81% |

3 |

43% |

New Zealand |

3 |

57% |

10 |

64% |

9 |

65% |

6 |

41% |

Australia |

4 |

56% |

11 |

64% |

8 |

68% |

12 |

37% |

Ireland |

5 |

56% |

16 |

62% |

7 |

69% |

10 |

38% |

Canada |

6 |

55% |

9 |

64% |

10 |

63% |

11 |

37% |

UK |

7 |

54% |

19 |

60% |

2 |

71% |

25 |

30% |

Netherlands |

8 |

53% |

37 |

53% |

5 |

71% |

14 |

36% |

Sri Lanka |

9 |

51% |

29 |

55% |

19 |

50% |

1 |

46% |

Indonesia |

10 |

50% |

86 |

42% |

6 |

69% |

7 |

40% |

Source Gallup World Poll (2018) as reported in Charity Aid Foundation World Giving Index (CAF 2019)

I believe it is very problematic to create rankings of “most generous countries,” especially given the limitations in the operationalization of philanthropy in the GWP. It is a rather excluding practice: What do people living in countries ranking at the bottom think about this? From research, we know that people in those countries also display a wide range of generosity behaviors, as is illustrated for example by work on Bulgaria (Bieri and Valev Reference Bieri, Valev, Wiepking and Handy2015), Russia (Mersianova et al. Reference Mersianova, Jakobson, Krasnopolskaya, Wiepking and Handy2015), Serbia (Radovanovic Reference Radovanovic2019) and China (Xinsong et al. Reference Xinsong, Fengqin, Fang, Xiaoping, Xiulan, Wiepking and Handy2015), countries that all rank in the bottom ten places in the 2019 CAF World Giving Index. Research shows that people in those countries are also generous, but in ways that are not captured by these rather unidimensional measures developed for WEIRD populations (Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010). In which WEIRD stands for Western, higher Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic.

There are many other ways people can display behavior that is beneficial to others: They can volunteer for organizations, donate organs, blood or other body fluids or in more informal ways help others, both kin and non-kin, care for others and share their resources, including expertise. In order to study global philanthropy, we need to understand the different concepts, meanings, definitions and motivations that people across the world have in relation to this phenomenon, continuing the work by—among others—Salamon and Anheier (Reference Salamon and Anheier1992, Reference Salamon and Anheier1998), Fowler and Mati (Reference Fowler and Mati2019) and Campbell and Çarkoğlu (Reference Campbell and Çarkoğlu2019).Footnote 6 As a personal critique, my own research has suffered from similar biases. I have conducted mostly research on “formal philanthropy,” using Western European perspectives and definitions, and studying WEIRD populations. In my future research, I intend to take into account all forms of philanthropy, using local words and definitions, and study the world’s population. In the final section of this article, I am suggesting the first steps for a collaborative research agenda, inspired to come to a truly global and inclusive understanding of philanthropic behavior. Interested researchers are explicitly encouraged to seek collaboration and help develop this agenda.

A Future Collaborative Research Agenda: To Come to An Inclusive Study of Global Philanthropy

The first step to overcome barriers and challenges that researchers are facing in the global study of philanthropy is to start by tackling the problems with connotations. One tentative suggestion is to replace the use of the word “philanthropy” with “generosity,” when studying this phenomenon globally. I say tentatively, because I fully realize there may not be one global term for this complex, multifaceted behavior. But, in contrast to philanthropy, generosity appears to have a more favorable connotation. In a series of informational interviews with scholars and practitioners from across the world, Herzog et al. (Reference Herzog, Strohmeier, King, Khader, Williams and Goodwin2020) conclude that generosity “is seen to be a softer concept, one that is more concerned with the motivation or values behind the act of giving than with the gift itself.” (Herzog et al. Reference Herzog, Strohmeier, King, Khader, Williams and Goodwin2020, p. 464). In lieu of better-unified terminology, I will use “generosity” moving forward, until research presents us with better alternatives.

Secondly, we need to work on the problems with definitions. We know that people across the globe practice different types of generosity behaviors. In order to come to an inclusive understanding of what types of generosity behavior people across the world practice, the language they use to discuss this, the motivations they have for this behavior, and not less important, how we can ask them to report about this, we can use several strategies. I highlight two complementary strategies. The first is to continue the excellent qualitative work into all forms of generosity behavior that researchers have been and are continuing to conduct locally, to mention a few examples, in addition to the already mentioned studies by Butcher and Einolf (Reference Butcher and Einolf2017), Fowler and Mati (Reference Fowler and Mati2019), Campbell and Çarkoğlu (Reference Campbell and Çarkoğlu2019) and Bies and Kennedy (Reference Bies and Kennedy2019): a study of the role of the state in relation to volunteering in China (Hu Reference Hu2020); different types of prosocial behavior in Brazil (Vieites Reference Vieites2017); charitable giving to health care in Iran (Ziloochi et al. Reference Ziloochi, Sari, Takian and Arab2019); the motivations of international volunteers from Japan (Okabe et al. Reference Okabe, Shiratori and Suda2019); employee volunteering in Iran (Afkhami et al. Reference Afkhami, Nasr Isfahani, Abzari and Teimouri2019); and individual giving in India (Sen et al. Reference Sen, Chatterjee, Nayak and Mahakud2020), China (Yang and Wiepking Reference Yang and Wiepking2020), Ethiopia (Yasin Reference Yasin2020) and Mexico (Butcher García-Colín and Ruz Reference Butcher García-Colín and Ruz2016). A second strategy I like to suggest is a large-scale, comparative, qualitative study, where local and international researchers and students interview representative citizens about their “generosity” behaviors and motivations for this behavior in their own language.Footnote 7

Only when we have a better qualitative understanding of the language, meaning, practices and motivations of generosity behaviors across the world, we may be able to design a quantitative study where we comparatively operationalize and measure these behaviors and their motivations. This quantitative study would need to incorporate the multifaceted definitions of generosity and use local languages and terminology in order to be inclusive of the different behaviors and motivations. When these data are collected using open science practices, researchers from across the world would have access to high-quality data—both qualitative and quantitative—measuring generosity behaviors. This will likely increase the geographical representation of published academic research on generosity, the remaining problem addressed in this article.

A final suggestion for a research agenda for the global study of generosity targets solving the lack of comparable information on the institutionalization, policies, rules and regulations that make up the context for generosity behaviors. In order to conduct macro-level comparative research, high-quality country- and regional-level data are necessary. A start to collect these contextual data was made in the project that resulted in the IIPD (Reference Wiepking and Handy2016) and the Palgrave Handbook of Global Philanthropy (Wiepking and Handy Reference Wiepking and Handy2015b): the Contextual International Philanthropy Database (CIPD work in progress).Footnote 8

Here, collaboration with governments, civil society actors and especially international civil society network organizations such as WINGS and CIVICUS may be very relevant. Only when high-quality data about the changing (institutional) context for generosity behavior are available, researchers will be able to study the implications of interventions intended to stimulate global generosity. And only then, they will be able to contribute to development of societies where people are more inclined to display generosity behaviors with the aim to contribute to improved societal outcomes for everyone.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the audience of the 2019 ERNOP Conference in Basel, Switzerland, the three anonymous reviewers, the editors of this special issue and René Bekkers and Femida Handy for their feedback to previous versions of this work. I am thankful for Beth Breeze for the generous sharing of resources on European critiques of philanthropy as well as her feedback to a previous version of this article. The author would also like to thank the many students who have contributed to this article in one way or another: first of all, PhD students Kidist Yasin, Yongzheng Yang, Dana Doan and Anastesia Okaomee who have shared many insights and through this helped me develop new thoughts and ideas about studying generosity from a non-WEIRD perspective, but also all my students in the global philanthropy classes at the IU Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, who shared their experience and insights related to the practice of global philanthropy, and interviewed people all across the global on their generosity behaviors. Finally, I am thankful for the support for my work by Mary-Joy and Jerre Stead, their family and the Dutch Charity Lotteries.

Funding

The work by Pamala Wiepking at the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy is funded through a donation by the Stead Family, and her work at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam is funded by the Dutch Charity Lotteries.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.