Introduction

Political parties regularly change their policy positions for a wide range of reasons. Spatial theories of party competition and research examining responsiveness suggest that parties shift their positions in order to appeal to the median voter (Downs, Reference Downs1957; Soroka & Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010). Testing these theoretical accounts, there is much empirical evidence that shows that parties are indeed responsive to public opinion (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Dassonneville, n.d; Soroka & Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010, but see Gilens and Page, Reference Gilens and Page2014; O'Grady & Abou‐Chadi, Reference O'Grady and Abou‐Chadi2019), or to the opinions of their own supporters (Adams, Reference Adams2012; Ibenskas & Polk, Reference Ibenskas and Polk2022). Parties have also been found to change their positions in response to rivals' policy shifts (Adams & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Adams and Somer‐Topcu2009b), in response to radical challenger parties (Abou‐Chadi & Krause, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Krause2018; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017; Meijers & van der Veer, Reference Meijers and Veer2019), and in response to external crises (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Haupt and Stoll2009; Braun et al., Reference Braun, Popa and Schmitt2019; Meyer & Schoen, Reference Meyer and Schoen2017). The pervasiveness of policy change begs the question what voters think about parties that change their positions. Although the study of policy shifts and repositioning has blossomed in recent years, it remains unclear whether voters believe repositioning to be a legitimate course of action in political representation, and how such attitudes toward party policy change are structured across voters' individual‐level characteristics.

A first possibility is that voters reject party policy change. They could do so because change increases uncertainty about a party's true policy preferences. Repositioning can also be regarded as a sign of parties' insincerity and opportunism. Moreover, flip‐flopping may be seen as an indication that parties are lacking competence and foresight (Andreottola, Reference Andreottola2021, p. 1669). As an alternative possibility, voters may readily accept parties' repositioning and view it as a sign of parties' flexibility, pragmatism and willingness to compromise (Green‐Pedersen & Hjermitslev, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Hjermitslev2024). Democratic responsiveness, which lies at heart of representative democracy, implies that parties adapt their positions in line with public opinion (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967; Soroka & Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010). Moreover, new circumstances and crises may necessitate parties to alter their stances and change course.

Previous research has come to diverging conclusions about voters' attitudes toward party policy change. Research on the party‐level suggests that the electoral repercussions of position changes vary by the kind of party, the issue and the political context (Adams & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Adams and Somer‐Topcu2009a; Ezrow, Reference Ezrow2005; Meijers & Williams, Reference Meijers and Williams2020; Tavits, Reference Tavits2007). On the individual‐level, there is evidence that parties may not stand to gain from shifting to the right across different contexts and issues (Abou‐Chadi et al. Reference Abou‐Chadi, Cohen and Wagner2022; Karreth et al. Reference Karreth, Polk and Allen2013; Krause et al. Reference Krause, Cohen and Abou‐Chadi2023; but see Hjorth & Larsen Reference Hjorth and Larsen2022). Yet, while this research suggests that certain policy shifts may not be appreciated by voters, it is unclear whether voters are punishing parties on the grounds that they reject policy change as such or that they disagree with the new position. Studies relying on survey experimental methodologies have also arrived at opposing conclusions. One set of studies has found that position change negatively affects political support (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2016; Lupu, Reference Lupu2013; Meijers, Reference Meijers2023; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2016). Repositioning also negatively affects the perceived credibility of the party's position (Christensen & Fernandez‐Vazquez, Reference Christensen and Fernandez‐Vazquez2023; Fernandez‐Vazquez, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez2019) – with partisanship playing a decisive role (Fernandez‐Vazquez & Theodoridis, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez and Theodoridis2020). Another set of studies argue that repositioning is less damaging than commonly assumed (Croco, Reference Croco2016; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Croco and Turitto2019; Schneider, Reference Schneider2020; Sigelman & Sigelman, Reference Sigelman and Sigelman1986). These studies find that voters reward flip‐flopping to a position that is congruent with their own policy preferences, as opposed to evaluating repositioning in valence terms only (Nasr & Hoes, Reference Nasr and Hoes2024). Furthermore, studies that seek to examine which styles of representation voters prefer indicates that promise‐keeping – which would imply stability in positions – is not what citizens prioritise. Based on an experimental study, for example, Dassonneville et al. (Reference Dassonneville, Blais, Sevi and Daoust2021) conclude that in terms of their preferences about how a representative should act, citizens prefer responsiveness to public opinion over candidates sticking to their campaign promises. Along the same lines, Werner (Reference Werner2019, p. 186) finds that citizens ‘care considerably less whether a policy fulfills an election promise than whether it falls in line with public opinion or expert advice on what is best for the common good’.

The existing literature thus finds that appraisals of policy change differ across political contexts, policy issues and voters' own policy preferences. Although there is tremendous value in understanding how voters respond to policy shifts on certain issues or shifts that occur under specific circumstances, what is missing from the literature is an assessment of voters' principled opinions about parties' positional change and whether they find position changes legitimate. As a result, we have a limited understanding of the individual‐level determinants that lead individuals to be more inclined to accept or to reject policy change – net of whether they agree with the policy position. In sum, despite the (mostly experimental) body of work that has studied the consequences of policy change, we still lack insights in the relationship between voters' attitudes and engagement with politics, on the one hand, and their principled acceptance of party repositioning on the other. Moreover, research that seeks to get an overall sense of citizens' appraisals of policy shifts by studying party shifts as captured by manifesto data and their correlation with election results is limited too. This holds, in particular, because policy shifts measured using manifesto data do not seem to correlate with changes in average voter perceptions of these shifts (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Bernardi, Ezrow, Gordon, Liu and Phillips2019). To understand how voters think about party policy change it is therefore important to ask them directly about parties' changes in policy positions. Previous research using this approach has shown that most voters have accurate perceptions of parties' shifts (Jung & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Jung and Somer‐Topcu2022; Seeberg et al., Reference Seeberg, Slothuus and Stubager2017; Somer‐Topcu et al., Reference Somer‐Topcu, Tavits and Baumann2020), especially among governing parties when the policy issue is salient (Plescia & Staniek, Reference Plescia and Staniek2017).

To address these gaps in the literature, we implemented a new direct measure of policy change acceptance, which was administered to over 12,000 respondents across five European countries (Germany, Poland, Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom). The measure asks to what extent the respondent thinks parties should be able to change their policy position. Asking respondents about their overall acceptance of party policy change allows us to examine voters' preferences without specifying the issue and context. This measure allows us to examine the distribution of voters' principled acceptance or rejection of policy change as well as its determinants. We theorise that voters' responses to party policy change are driven by their political attitudes and their attitudes towards representative democracy. In particular, we expect that voters' political interest and ideological extremity affect the acceptance of party policy change. We also expect political attitudes about representation such as technocratic attitudes (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017) and populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) to have downstream effects on the perceived legitimacy of party policy change. In addition, we implement an open‐ended question capturing respondents' opinions about the reasons for party policy change in their own words. Using automated text analysis, these data allow us to test the face validity of our measure and explore voters' motivations to accept and reject party policy change in addition to our formal analyses.

Our findings show that, overall, a slight majority of voters in Germany, Poland, Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom believe that parties should be able to change their policy positions. At the same time, there is considerable variation in the degree to which voters accept party policy change. Some country‐level variation notwithstanding, we find that ideological extremism and populist attitudes have a distinct negative effect on policy change acceptance, while political interest and technocratic attitudes have a positive effect on policy change acceptance. What is more, we find that voters of centrist and left‐wing parties tend to be more likely to accept party policy change than radical right voters. Automated text analysis of the open‐ended survey question shows that there are clear differences in the language used by those who accept and those who reject party policy change. Keyness statistics indicate that proponents of party policy change tend to highlight the necessity of adaptability in party positioning, while opponents see repositioning as evidence for the opportunistic, self‐serving natures of party elites. This dovetails with the finding that voters with high levels of populist attitudes and voters for radical right parties are more likely to reject policy change, while centrist voters with high political interest tend to accept it.

In what follows, we first discuss the existing literature on party policy change. In a next step, we examine policy change acceptance in a descriptive manner and reflect on the likely voter characteristics of voters who accept and reject party policy change, and subsequently introduce our hypotheses. In the Data and Methods section, we expand on our methodological approach and the case selection. We then present the findings of the main analyses as well as of the automated text analysis, followed by a conclusion.

Voters' acceptance of party policy change

Despite the flourishing study of party policy shifts and repositioning in recent years, it remains unclear whether voters believe party repositioning to be a legitimate course of action in political representation, and how such attitudes toward party policy change are structured across voters' individual‐level characteristics.

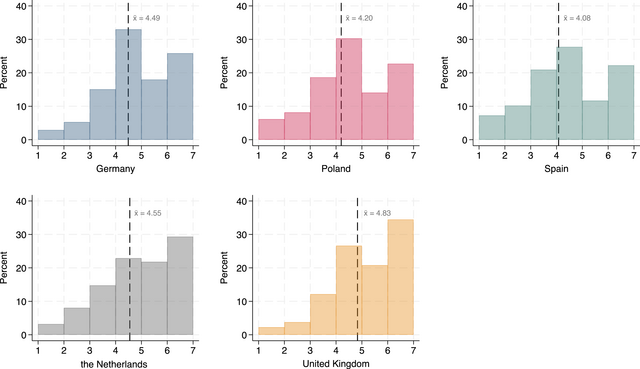

This study is the first to ask respondents directly how they evaluate party policy change. We do so by posing the question to what extent the respondent believes political parties should be able to change their positions, or not on a 1–7 scale – with the ends corresponding to the position that parties should ‘never’ or ‘always’ be able to change their positions. Below we provide more details on the operationalisation of this variable. Figure 1 provides descriptive evidence of voters' overall acceptance of party policy change among British, Dutch, German, Polish and Spanish voters. As Figure 1 shows, there is overall considerable support in all five countries for the idea that parties should be able to change their positions. The median value on the 1–7 scale is four in Germany, Poland and Spain and it is five in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. In each country, there are more respondents that take a position towards the ‘always’ end of the scale than there are respondents choosing a position on the ‘never’ end of the scale. Figure 1 also shows that respondents in the United Kingdom are most likely to accept party repositioning. While a plurality of respondents in each of the countries is rather open to the principle of parties' ability to change their positions, Figure 1 shows that there is significant variation among respondents.

Figure 1. Histogram plot of policy change acceptance by country.

What explains this variation? Theoretically speaking, there are two contrasting perspectives on party policy change. While some voters welcome party repositioning as open‐minded, pragmatic policy making, others reject it as insincere and incompetent politics. We theorise that these perspectives are aligned with individual‐level characteristics, which we expect to have predictive qualities with respect to respondents' support for party policy change.

Expectations

Explanations of voters' support for policy change

Some voters are likely to accept, or even praise, party policy change and consider it an indication of the party's open‐mindedness, flexibility and pragmatism. After all, the democratic ideal of substantive representation postulates that political parties should address public concerns and change their policy positions to follow public opinion (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967; Soroka & Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010). Position change, from this perspective, lies at heart of democratic representation. What is more, given that proper policy implementation entails policy evaluation (Wollmann, Reference Wollmann, Fischer and Miller2017), voters may commend parties for re‐thinking their initial positions when a policy does not have the desired effect. Similarly, voters can appreciate parties to change their positions in the face of changing circumstances. New circumstances may require political parties to revisit their previously held positions. Particularly crises that endanger the well‐being of citizens, such as the Covid19 pandemic, require policy makers to act swiftly, reallocate budgets and change political course (see, e.g., Gilardi et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2021). In addition, in settings where parties govern in coalitions or need the collaboration of other parties to govern, voters might understand that parties have to make compromises to find an agreement with other parties (Plescia et al., Reference Plescia, Ecker and Meyer2022).

We argue that voters' political interest affects how they view party repositioning. Political interest is a key predictor of individuals' political behaviour (Prior, Reference Prior2010). The politically interested are more knowledgeable about politics and more likely to engage in institutionalised and non‐institutionalised forms of political participation (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Schlozman and Verba1999; Carpini & Keeter, Reference Carpini and Keeter1996). Politically interested voters also consume more political news and, as a result, are usually exposed to more perspectives and conflicting viewpoints (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2011; Prior, Reference Prior2007). Hence, politically interested voters are more likely to be aware of the societal and political context that informs policy makers' positioning. Moreover in terms of personality characteristics, politically interested voters tend to be open to new ideas and experiences (Larsen, Reference Larsen2022; Vitriol et al., Reference Vitriol, Larsen and Ludeke2019).

We therefore argue that because the politically interested consume more political news and are more aware of the political context which can necessitate parties' repositioning, this leads politically interested voters to be more accepting of party policy change, compared to voters who are not interested in politics. We expect high politically interested individuals to reflect on the need for party policy change in the light of changing political circumstances or other positively‐valenced reasons, which suggests a positive effect of political interest.Footnote 1 We therefore posit the following hypothesis:

1 Hypothesis All else equal, the higher a respondent's level of political interest, the more favourable they are toward party policy change.

The belief that new information and new expertise should guide policy making arguably makes one more amenable to accept party policy change. Citizens who hold strong technocratic attitudes are particularly likely to reason this way. Technocracy, as Caramani (Reference Caramani2017) put it, ‘stresses responsibility and requires voters to entrust authority to experts who identify the general interest from rational speculation’. Technocracy does not only denote a view of power and representation, but can also be operationalised as an attitude towards political decision‐making among citizens (Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2022; Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández‐Vázquez2022).

In its extreme form, technocracy is antithetical to pluralist party government as it is centred around the idea that expertise helps the identification and implementation of objective solutions to societal problems, while disregarding public opinion or political deliberation (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2022; Caramani, Reference Caramani2017). Yet, as an adjective, ‘technocratic’ decision‐making arguable denotes a form of decision‐making that is more geared towards incorporating expert opinion and knowledge into its decisions at the cost of political responsiveness. We expect that citizens' propensity to accept expert rule positively affects their acceptance of party repositioning. While non‐technocrats may regard deviations of parties' policy platforms or past promises as violations of their representational role, technocrats likely do not prioritise the representational tasks of political parties. Rather, citizens with strong technocratic attitudes are likely to embrace the idea that different circumstances require different solutions. We therefore expect:

2 Hypothesis All else equal, the higher a respondent's level of technocratic attitudes, the more favourable they are toward party policy change.

Explanations of voters' opposition to policy change

Another group of voters is less accepting of party repositioning. Voters may reject party policy change because change increases uncertainty about a party's true policy preferences. After all, for policy representation to be effective political parties need to have readily identifiable political profiles, or ideological ‘brands’ (Lupu, Reference Lupu2013; Nasr, Reference Nasr2020). Voters may also interpret repositioning as a sign of insincere and opportunistic party behaviour. When voters suspect political actors to opportunistically pander to public opinion, this increases uncertainty about the latter's policy preferences (Fernandez‐Vazquez, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez2019; McGraw et al., Reference McGraw, Lodge and Jones2002) – again negatively affecting the representational linkage between voters and representatives. In addition, when political actors alter their positions, voters can take this as a signal of incompetency or interpret it as an indication of the party's lack of expertise and foresight (Andreottola, Reference Andreottola2021, p. 1669).

Previous research on the party‐level has shown that niche parties are unresponsive to shifts in public opinion, while mainstream parties tend to change their policy positions in response to public opinion shifts (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006). What is more, Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006) show that niche parties lose votes when they change their policy platforms, while mainstream parties do not. Given that niche and challenger parties usually adopt more extreme positions on previously ignored issues (de Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2012), their losses after policy change could result from the fact that voters with extreme positions reject policy change. Moreover, positional extremity is found to be correlated with, but analytically distinct from, the certainty of individuals' attitudes (Krosnick et al., Reference Krosnick, Boninger, Chuang, Berent and Carnot1993; Petrocelli et al., Reference Petrocelli, Tormala and Rucker2007). Furthermore, research finds that ideologically extreme individuals are prone to be more dogmatic in their political beliefs (Harris & Van Bavel, Reference Harris and Van Bavel2021; Van Prooijen & Krouwel, Reference Van Prooijen and Krouwel2017). Dogmatic citizens are, moreover, more resistant to attitudinal and positional change (Miller, Reference Miller1965; Rokeach & Fruchter, Reference Rokeach and Fruchter1956). We therefore expect respondents' ideological extremity to negatively affect their acceptance of party repositioning:

3 Hypothesis All else equal, the more extreme a respondent's political preferences, the less favourable they are toward party policy change.

Finally, we believe that populist ideation affects how voters think about party repositioning. Populist beliefs can be a characteristic of political actors, but also of citizens as the literature on populist attitudes has shown (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020). Populism can be understood as a set of ideas grounded in the view that there is a conflict between ‘virtuous’ people and the ‘evil’, corrupt elite (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2009; Mudde, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017). The political elite is seen as a self‐serving elite, solely interested in furthering their own personal gain. As such, populism denotes fierce anti‐elite and anti‐establishment sentiments. Populist actors in turn capitalise on citizens' political discontent and deep‐seated mistrust of political actors.

Moreover, populism assumes that ‘the people’, however defined, are a homogeneous entity and share a single ‘general will’ in the Rousseauian sense. As such, populism negates political pluralism within and among ‘the people’ (Urbinati, Reference Urbinati2019; Zaslove & Meijers, Reference Zaslove and MeijersZaslove & Meijers). This explains the inherent tension between populism and representative democracy, as the latter is based on deliberation and compromise between conflicting viewpoints. Tellingly, the rejection of compromise is part and parcel of many operationalisations of populist attitudes on the individual level (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020). And while populist citizens do not reject liberal democracy per se, they are more likely to reject the intermediary role parties play in modern democracies (Zaslove & Meijers, Reference Zaslove and MeijersZaslove & Meijers).

Expert survey evidence shows that populist parties reject the supposition that political decision‐making is a complex process, advocating common‐sense solutions instead (Meijers & Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021, p. 384). Bischof and Senninger (Reference Bischof and Senninger2018) show that populist actors simplify their campaign messages in comparison with non‐populist politicians. Research studying populism in public opinion furthermore shows that populists embrace the idea to be represented by ordinary citizens, rather than professional politicians (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). These considerations suggest that voters with populist beliefs are less likely to accept it when parties change their policy platform. Highly populist voters' mistrust of elites leads to believe that parties' actions are insincere and opportunistic. Moreover, since populists favour common sense solutions, populists reject the idea that policy review and evaluation lead to adaptation of policy proposals. What is more, by repositioning, parties introduce additional complexity that populists are keen to avoid. We therefore posit the following hypothesis:

4 Hypothesis All else equal, the higher a respondent's level of populist attitudes, the less favourable they are toward party policy change.

Data and case selection

We test our hypotheses using newly collected survey data in five countries. Data collection was conducted by two survey organisations: YouGov in the Spring of 2022 (in Germany, Poland, Spain and the United Kingdom) and ElectionCompass in the Autumn of 2023 (in the Netherlands).Footnote 2

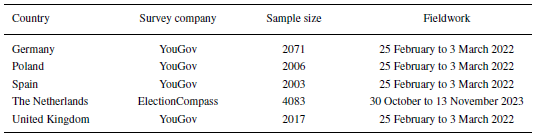

The YouGov samples were recruited from the YouGov panel. Responses were obtained using quota sampling with quotas for age, gender and region for a total of ca. 2,000 respondents per country. To approach national representativeness of the data, the data were weighted using rim weighting algorithm for a joint distribution of age, gender and region. The Dutch sample was recruited from the ElectionCompass panel, a Voting Advice Application, for a total of 4083 completed responses. To provide nationally representative population estimates, the data were subsequently weighted using poststratification, employing a joint demographic distribution of age, sex, educational attainment, ethnic background and geographic region. Table 1 provides an overview of the five samples that were collected. Appendix A of the Supporting Information provides more information on the weighting procedure that was used in each of the five countries.

Table 1. Overview of the collected data

The five countries where we collected data not only cover different geographical regions in Europe, they also differ in terms of the electoral system, the size of the party system, as well as nature of the government in place at the time of the survey (for details, see Appendix B of the Supporting Information). Specifically, the sample includes countries using proportional electoral rules as well as a country using a majoritarian electoral system (the United Kingdom). It also includes both countries with a fairly limited effective number of parties (3.2 in the United Kingdom and 3.4 in Poland) as well as large party systems (9.3 parties in the Netherlands). Furthermore, at the time of the survey, coalition governments were in place in three countries, while a single party governed in Poland and the United Kingdom. Among the countries that had a coalition government, furthermore, one had a minority government (Spain) while in the other two countries the coalition controlled a majority of the seats in parliament. Given that these institutional features generate different incentives for parties to change their positions, there is meaningful variation in the sample in terms of contextual factors that could correlate with citizens' exposure to party policy change. This difference in the institutional incentives for change is also visible when we assess how much parties tend to change their ideological positions over time in each of the five countries in the dataset. As can be seen from supplemental analyses in Appendix B of the Supporting Information, on average there is more change in parties' positions in Poland and the United Kingdom – the countries with the lowest effective number of parties.

In summary, given the diverse nature of the set of countries where we collected data, if we find that the correlates of citizens' acceptance of party policy change are very similar across the countries in our dataset, we can be fairly confident that these findings generalise across institutional contexts.

Methods

Our empirical analysis proceeds in two steps. First, we test our hypotheses using observational survey evidence from Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and the United Kingdom. Second, to gain a deeper insight into the reasoning of our respondents, we analyse respondents' answers to an open‐ended survey question on why they believe parties change their policy positions.

Dependent and independent variables

The dependent variable in this study is our newly developed policy change acceptance item, which captures respondents' views on whether parties should be able to change their positions or not. We operationalised the item as follows: ‘Political parties sometimes change their positions on policy issues. What is your opinion about this? Please indicate on a 1–7 scale whether you think parties should be able to change their policy positions. 1 means that you think that parties should always be able to change their policy positions, 7 means you think that parties should never be able to change their positions’. We subsequently inverted the response categories so that higher values denotes acceptance of party policy change.

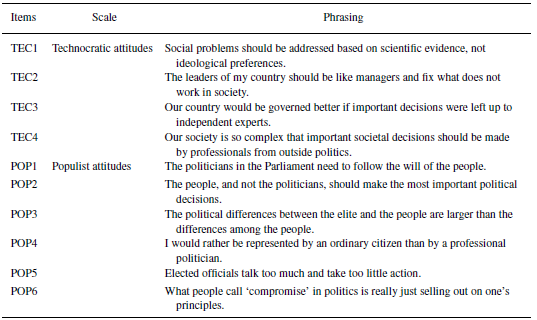

The main independent variables of interest are political interest, technocratic attitudes, extremism and populist attitudes. Political interest is measured on a 1–5 scale with the question ‘Generally speaking, how interested are you in politics?’ with 1 meaning ‘very interested’ and 5 ‘not at all interested’. We reversed the item so that higher values denote higher political interest. We measure technocratic attitudes on the basis of an iterated principal exploratory factor analysis with orthogonal varimax rotation on the basis of four items with a minimal threshold of factor loadings of 0.5 and a minimal Eigenvalue of 1.0. The four items are shown in Table 2. Items TEC1 and TEC2 are taken from Bertsou and Caramani (Reference Bertsou and Caramani2022)'s expertise measure and items TEC3 and TEC4 are taken from the expertise elitism measure of Spruyt et al. (Reference Spruyt, Rooduijn and Zaslove2023). The latent variable of technocratic attitudes was constructed using the predicted regression scores of each factor yielded by the explanatory factor variable. We measure respondents' ideological extremism on the basis of an 11‐point left–right self‐placement question (1–11). Extremism is measured by folding the left–right item, operationalised as the absolute difference from the midpoint (6): ![]() . Finally, populist attitudes are measured following the approach proposed by Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). We make use of the six items shown in Table 2, which we adopted from Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). Subsequently, we conduct an iterated principal exploratory factor analysis with orthogonal varimax rotation on the basis of four items with a minimal threshold of factor loadings of 0.5 and a minimal Eigenvalue of 1.0. We construct the latent variable of populist attitudes on the basis of the regression scores of a factor variable. Appendix C of the Supporting Information details the results of the iterated principal exploratory factor analyses for technocratic attitudes and populist attitudes and shows that the construct validity of both latent variables is high.Footnote 3 Summary statistics of all variables can be found in Appendix D of the Supporting Information.

. Finally, populist attitudes are measured following the approach proposed by Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). We make use of the six items shown in Table 2, which we adopted from Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). Subsequently, we conduct an iterated principal exploratory factor analysis with orthogonal varimax rotation on the basis of four items with a minimal threshold of factor loadings of 0.5 and a minimal Eigenvalue of 1.0. We construct the latent variable of populist attitudes on the basis of the regression scores of a factor variable. Appendix C of the Supporting Information details the results of the iterated principal exploratory factor analyses for technocratic attitudes and populist attitudes and shows that the construct validity of both latent variables is high.Footnote 3 Summary statistics of all variables can be found in Appendix D of the Supporting Information.

Table 2. Overview of items for technocratic attitudes and populist attitudes measures

Model specification

To test our hypotheses, we conduct simple OLS regression analysis with policy change acceptance as the main dependent variable. We first estimate a pooled regression model with country fixed effects, followed by the estimation of country‐specific models. Subsequently, we unpack the effects of extremism by distinguishing between left‐ and right‐wing extremists. We also explore how vote choice is associated with party change acceptance.

In addition to the independent variables of theoretical interest, we include important control variables in the models. Specifically, we control for gender [male/female], education level [low/mid/high] and age (measured as a continuous variable ranging from [18,92] ![]() = 50.8). To address missing values, we recoded ‘Don't Know’ responses to the neutral value in the midpoint of the scale. To ascertain this did not affect our substantive results, we conduct tests in which we control the ‘Don't Know’ responses of the respondents (see Appendix E of the Supporting Information).

= 50.8). To address missing values, we recoded ‘Don't Know’ responses to the neutral value in the midpoint of the scale. To ascertain this did not affect our substantive results, we conduct tests in which we control the ‘Don't Know’ responses of the respondents (see Appendix E of the Supporting Information).

While we have good theoretical reasons to expect a connection between our independent variables and policy change acceptance, readers should keep in mind that our models aim to assess associations, not causal relationships.

Analysis of open‐ended survey questions

To complement our analysis of the individual‐level correlates of voters' acceptance of party policy change, we build on an emerging literature in political science and gain a deeper understanding of voters' reactions to policy change by analysing respondents' answers to an open‐ended survey question (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Sheffer and Mor2022; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Stewart, Tingley, Lucas, Leder‐Luis, Gadarian, Albertson and Rand2014; Zollinger, Reference Zollinger2024).

Specifically, as part of the survey, respondents in all five countries were asked the following question ‘Now could you tell us, in your words, why you think parties sometimes change their policy positions?’ We analyse respondents' answers to this open‐ended survey question to get a sense of how common it is for voters to associate policy change with insincere and opportunistic behavior, versus to conceive of party policy change as a result of open‐mindedness and pragmatism.

Respondents' answers to this open‐ended survey question were recorded in different languages in each of the five countries. Before analysing the data, we therefore translated all responses to English using the DeepL API.Footnote 4 Respondents who answered the questionFootnote 5 gave meaningful answers to this question, with an average length of about nine words before pre‐processing the data.Footnote 6

Using the Quanteda package (Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Watanabe, Wang, Nulty, Obeng, Müller and Matsuo2018), we subsequently pre‐processed the data. We removed punctuation, stemmed words and used the toks_comp function in Quanteda to compound multi‐word expressions that occur often in the data.Footnote 7 This allows for terms as ‘public opinion’ or ‘new information’ to appear as a single term rather than as separate words in the subsequent analysis. Next we removed words without a substantive meaning and words appearing in the survey question (which respondents tend to repeat when they answer, see Ferrario & Stantcheva, Reference Ferrario and Stantcheva2022). For a full list of words that were removed from the text corpus, see Appendix F of the Supporting Information. As a final step, we filtered out words that had a length of two characters or less.

Our analysis of respondents' answers to the question why parties could change positions is descriptive. In a first step, we examine which words respondents in each of the five countries use most when describing the reasons why parties sometimes change positions. We contextualise these word occurrences by means of a qualitative description of respondents' answers. In a second step, we conduct a relative frequency analysis – calculating keyness scores – contrasting the answers of respondents who are more in favour of policy change and those who are more opposed. Specifically, we distinguish between those indicating a score lower than four (which we label as the pro change group) and those indicating a score of four or higher (which we label as the contra change group) on the 1–7 indicator of voters' opposition to policy change which we analysed in the previous section. The keyness scores then allow identifying the words that are characteristic for the answers of both groups of respondents (Zollinger, Reference Zollinger2024), focusing on what distinguishes the answers of those who are more in favour and those who are more opposed to party policy change.

Results

Correlates of repositioning acceptance: Pooled results

What explains how voters think about policy change acceptance? Figure 1 has already shown that there is considerable heterogeneity when it comes to respondents' opinions on the normative question whether parties should be able to change their positions, or not. We posit that political interest (H1), technocratic attitudes (H2), extremism (H3) and populist attitudes (H4) co‐determine respondents' acceptance of party repositioning. Table 3 shows the main results pooled across countries.

Table 3. Pooled OLS regression analysis

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. *![]() ; **

; **![]() ; ***

; ***![]() .

.

In line with Hypothesis 1, political interest has a positive, statistically significant effect on respondents' propensity to accept party repositioning (![]() ‐value

‐value ![]() 0.000). As can be seen from the standardised coefficient for political interest, its effect is small but not negligible. Specifically, a one‐standard‐deviation increase in political interest, is associated with 0.09‐standard‐deviation increase in policy change acceptance. By contrast, while technocratic attitudes has a positive effect on policy change acceptance as Hypothesis 2 posited, it does not meet the threshold for statistical significance in these pooled results (p‐value

0.000). As can be seen from the standardised coefficient for political interest, its effect is small but not negligible. Specifically, a one‐standard‐deviation increase in political interest, is associated with 0.09‐standard‐deviation increase in policy change acceptance. By contrast, while technocratic attitudes has a positive effect on policy change acceptance as Hypothesis 2 posited, it does not meet the threshold for statistical significance in these pooled results (p‐value ![]() 0.340). Turning to possible determinants of rejection of party repositioning, we find – in line with Hypothesis 3 – that ideological extremism has a statistically significant negative effect on policy change acceptance (

0.340). Turning to possible determinants of rejection of party repositioning, we find – in line with Hypothesis 3 – that ideological extremism has a statistically significant negative effect on policy change acceptance (![]() ‐value

‐value ![]() 0.001). The substantive size of this effect is limited however. The standardised coefficient indicates that a one‐standard‐deviation increase in extremism reduces policy change acceptance by 0.04 standard deviations. Finally, Hypothesis 4 stipulated that populist attitudes have a negative effect on voters' acceptance of party positional shifts. In line with this expectation, we find that populist attitudes have a sizeable and statistically significant effect on policy change acceptance (

0.001). The substantive size of this effect is limited however. The standardised coefficient indicates that a one‐standard‐deviation increase in extremism reduces policy change acceptance by 0.04 standard deviations. Finally, Hypothesis 4 stipulated that populist attitudes have a negative effect on voters' acceptance of party positional shifts. In line with this expectation, we find that populist attitudes have a sizeable and statistically significant effect on policy change acceptance (![]() ‐value

‐value ![]() 0.000). The standardised coefficient shows that the association between populist attitudes and policy change acceptance is quite strong. A one‐standard‐deviation increase in populist attitudes is associated with a 0.24‐standard‐deviation reduction in acceptance of party policy.

0.000). The standardised coefficient shows that the association between populist attitudes and policy change acceptance is quite strong. A one‐standard‐deviation increase in populist attitudes is associated with a 0.24‐standard‐deviation reduction in acceptance of party policy.

Correlates of repositioning acceptance: Country‐specific estimates

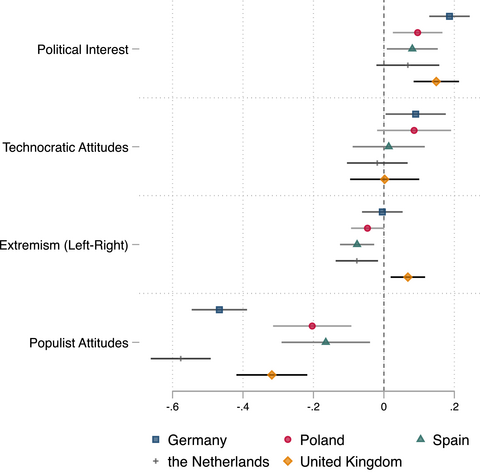

Table 3 presented our findings pooled across the five countries for which we collected data. Such pooled models can hide important variation between countries. We therefore estimate a separate OLS regression model for each country. Figure 2 visualises the results of these analyses for our five country samples, with a focus on the effects of the main independent variables. Table H.2 in Appendix H of the Supporting Information shows the full models including controls.

Figure 2. Coefficient plot of OLS regression models per country.

Note: All models include controls for gender, education and age. Survey weights are applied.

With respect to political interest, we see that it has a positive effect on policy change acceptance in most countries in our study, but fails to meet statistical significance in the Netherlands (![]() ‐value

‐value ![]() 0.135). Contrary to our expectations, the pooled model showed no positive effect for technocratic attitudes on policy change acceptance. Yet, the effect for Germany is positive (

0.135). Contrary to our expectations, the pooled model showed no positive effect for technocratic attitudes on policy change acceptance. Yet, the effect for Germany is positive (![]() ) and statistically significant (

) and statistically significant (![]() ‐value

‐value ![]() 0.038). For Poland the effect is also positive (

0.038). For Poland the effect is also positive (![]() ) but insignificant with a

) but insignificant with a ![]() ‐value of 0.109.

‐value of 0.109.

With respect to ideological extremism, the pooled results showed a significant, negative effect on policy change acceptance. Turning to country‐specific estimates, we see that extremism has a negative effect in four of the five countries. In the United Kingdom, ideological extremism has a significant, positive effect on respondents' tendency to accept policy change (![]() ,

, ![]() ‐value =

‐value = ![]() 0.006). In Germany, the effect is negative, but not statistically significant (

0.006). In Germany, the effect is negative, but not statistically significant (![]() ‐value

‐value ![]() 0.878). In Spain, Poland and the Netherlands, extremism has a significant, negative effect on policy change acceptance (with respective

0.878). In Spain, Poland and the Netherlands, extremism has a significant, negative effect on policy change acceptance (with respective ![]() ‐values of 0.002, 0.050 and 0.012). Finally, populist attitudes has a statistically significant negative effect in all five countries in our sample. For each country, populist attitudes is the strongest predictor of respondents' acceptance of party repositioning. The effect is particularly outspoken in Germany (

‐values of 0.002, 0.050 and 0.012). Finally, populist attitudes has a statistically significant negative effect in all five countries in our sample. For each country, populist attitudes is the strongest predictor of respondents' acceptance of party repositioning. The effect is particularly outspoken in Germany (![]() ) and the Netherlands (

) and the Netherlands (![]() ).

).

Robustness of the results

In Appendix I of the Supporting Information, we disaggregate the populist attitudes scale to examine whether particular items drive the effect of populist attitudes. These additional analyses indicate that POP2, POP4 and POP6 (see Table 2) in particular have large negative effects. POP2 and POP 4 capture popular rule by citizens rather than professional politicians, while POP6 captures compromise rejection. We also verify that the results are not driven by the compromise rejection item solely, which is conceptually the closest to our outcome variable. In Appendix I of the Supporting Information, we show that a five‐item construct without POP6 has similar substantive effects on our dependent variable.

Our findings are, moreover, robust to an alternative specification in which we add dummy variables for Don't Know values for the imputed variables. As the estimates in Appendix E of the Supporting Information show, all found effects remain significant and in the same direction. The exception is the effect of political interest in Poland (![]() ‐value

‐value ![]() 0.218).

0.218).

Finally, each of our key independent variables is measured with some error, and it could be argued that this introduces bias in the estimation. One way to account for this is by estimating an errors‐in‐variables model. In Appendix J of the Supporting Information, we show that effect sizes are somewhat larger when we do so.

Unpacking ideological extremism

Our main measure of ideological extremism captures ideological extremes irrespective of its ideological direction. However, it is possible that respondents with extreme left‐wing attitudes view party policy change differently than respondents with extreme right‐wing positions. Far right views are associated with exclusionary outlooks, whereas far left ideology is associated with inclusionary beliefs (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013; Vasilopoulos & Jost, Reference Vasilopoulos and Jost2020). This may well affect how left‐ and right‐wing extremists appraise party repositioning.

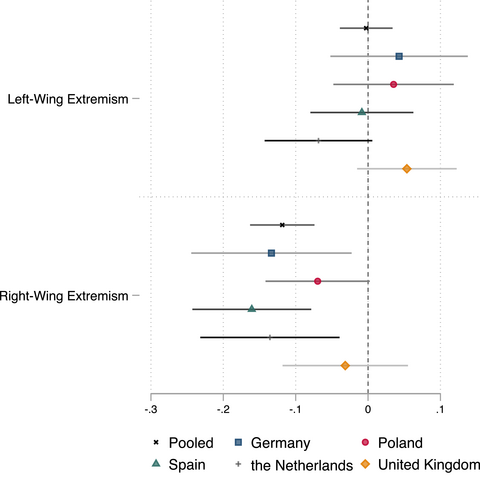

To explore whether extreme left and extreme right respondents have different views on the acceptability of party repositioning, we create two separate measures for left‐ or right‐wing extremism. In this operationalisation, the lowest score of 0 denotes a centrist or more left (more right) position and 5 signifies a more right (more left) position. Based on a full regression model including both variables and all other covariates, Figure 3 visualises the coefficients of left‐wing extremism and right‐wing extremism.Footnote 8

Figure 3. Coefficient plot of extremism for left‐wing and right‐wing extremists.

Note: All models include political interest, technocratic attitudes and populist attitudes as covariates as well as controls for gender, education and age. Survey weights are applied.

This additional analysis points out that the negative effect of extremism in our main model is driven by ideologically extreme respondents on the right side of the spectrum. Only in the United Kingdom there is no significant effect of right‐wing extremism on policy change acceptance (![]() ‐value

‐value ![]() 0.476). In contrast, there is no statistically significant effect for left‐wing extremism in any of the countries. For British, German and Polish respondents, the coefficient of left‐wing extremism (ranging from 0.035 to 0.053) is positive, but statistically insignificant with respective

0.476). In contrast, there is no statistically significant effect for left‐wing extremism in any of the countries. For British, German and Polish respondents, the coefficient of left‐wing extremism (ranging from 0.035 to 0.053) is positive, but statistically insignificant with respective ![]() ‐values of 0.126, 0.375 and 0.405.

‐values of 0.126, 0.375 and 0.405.

Party preference and repositioning acceptance

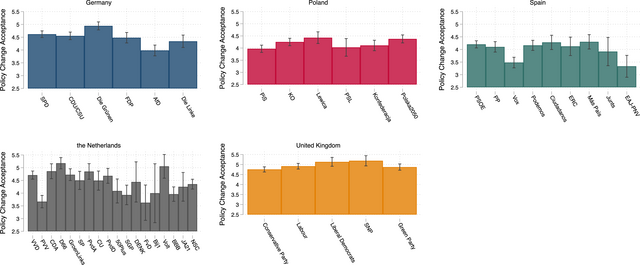

So far, in testing our hypotheses we have focused on the association between the acceptance of party policy changes and fundamental political attitudes. The analysis of the connection between ideological extremity and repositioning acceptance, however, already points out that citizens' acceptance of party policy change seems related to their party preferences. To explore this more systematically, we estimate an additional regression model in each country in which we include as covariates measures of respondents' partisan preferences. To do so, we include a series of dummy variables capturing whether a party is a respondent's most preferred party or not, which we construct by using a survey item asking respondents how much sympathy they have for a list of parties. The party for which the respondent expressed the highest sympathy is selected as the most preferred party.Footnote 9

Figure 4 visualises respondents' level of acceptance of party policy change per preferred party. To do so, we show, for each partisan group, the predicted level of policy change acceptance (and 95 per cent confidence intervals). Looking at the estimates for the different countries, a few patterns emerge. First, in line with the descriptive evidence in Figure 1, we see that voters in the United Kingdom are generally rather positive towards party repositioning, regardless of party preference.

Figure 4. Marginal effects of partisanship on policy change acceptance.

Note: Survey weights are applied.

Figure 4 also indicates that in most countries voters of centre‐left and centre‐right parties with governing experience are generally rather positive towards party repositioning, whereas more radical, anti‐establishment parties tend to oppose party repositioning. In line with our finding that respondents' populist attitudes and right‐wing extremism are a key predictor of their acceptance of party repositioning, we see that voters of far‐right parties (Vox in Spain, PVV and FvD in the Netherlands and to a lesser extent PiS in Poland) tend to reject party policy change. This provides face validity to the results of our main OLS regression models.

Evidence from open‐ended survey questions

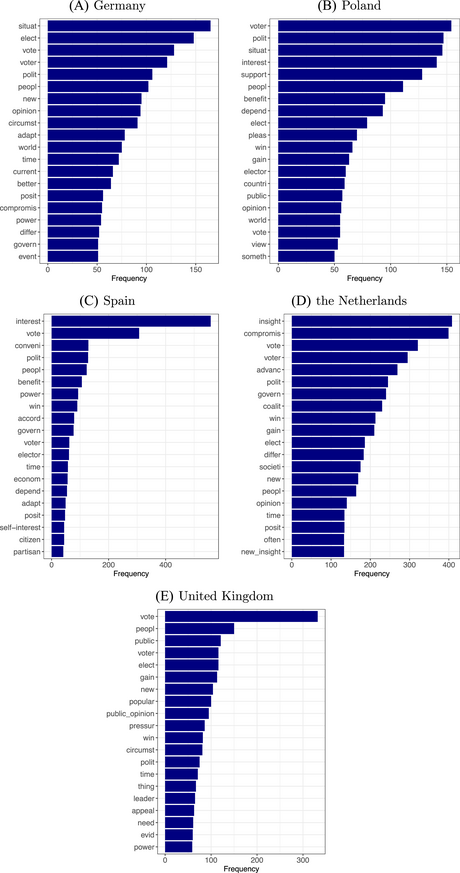

As a final step, we turn to an analysis of the open‐ended survey question. We start by examining the words that were mentioned most in respondents' answers to the question why they think parties sometimes change their positions. In Figure 5 we show, for each of the five countries, the 20 words most frequently used in respondents' open‐ended answers to this question. The graphs are sorted by frequency, with the highest‐frequency words in each country shown on top in the panels. What emerges clearly from these data is that respondents strongly associate party policy change with electoral considerations. This is clear from the frequent use of terms like ‘vote’ and ‘voter’. Respondents associate party policy change to elections and the electorate, but seem to specifically have in mind that party policy change can be a strategy for parties ‘to attract more voters’, as a respondent in the Netherlands formulates it, ‘to gain the sympathy of new potential voters’ (quote from a Spanish respondent), or ‘because they understand that otherwise voters will run away from them’ (quote from a German respondent).

Figure 5. Most used words used to describe the reasons of party policy change.

In addition to referring to elections and electoral considerations, respondents also mention public opinion (‘public’, ‘people’, ‘public opinion') more generally as a reason why parties can change their positions. A German respondent, for example, indicated that parties might change positions ‘because the opinions of society change’.

The open‐ended answers also include words that suggest a more explicitly negative interpretation of party policy change as opportunistic, leading to words as ‘power’ or ‘benefit’ being used quite often. For these respondents, party policy change is strategy that parties use out of self‐interest, or because it allows them to stay in power. One German respondent answered that they thought parties change positions ‘because they are interested exclusively in gaining and maintaining power’.

Respondents’ answers also reflect an understanding of institutional incentives for change, with ‘compromise’ being a much‐used term in the answers from Dutch respondents. One respondent in the Netherlands indicated that ‘parties sometimes change their policy positions because they have to compromise with other parties to get into the coalition’. In Germany, too, the need to form coalitions was sometimes referred to, as for instance in the response by a respondent who answered that change can allow a party to ‘get closer to the other parties for the purpose of forming a government’. In the United Kingdom, ‘leader’ is included in the list of the most used words, reflecting respondents' understanding that leadership change can lead a party to change its positions, because ‘Different leaders have different ideas’ (quote from a British respondent).

Finally, in each of the five countries there are respondents who appreciate that factors out of parties' control, as well as changing circumstances can lead parties to adapt their positions. This is clear from the fairly high position of the term ‘circumstances’ in Germany and the United Kingdom, or ‘advancing insight’ and ‘new insights’ in the Netherlands. A respondent in the United Kingdom summarised it as follows: ‘The world is changing so policy needs to be changed to keep up’.

Respondents' open‐ended answers to the question why parties change their positions reflect a good understanding of the different reasons that could lead parties to adjust their positions, but from these answers it is also quite clear that there are different levels of appreciation of party policy change. To more clearly distinguish between the views of respondents who evaluate party policy change negatively and those assessing policy change more positively, in Figure 6 we show keyness statistics that indicate which terms are most distinctively used by respondents who are against change (rating change lower than 4 on the 1–7 scale) and those who are more favourable of change (giving a rating of 4 or higher on the 1–7 scale). Here, we show keyness statistics for the full text corpus that combines information from the five countries, but Appendix K of the Supporting Information shows keyness statistics for each of the countries separately.

Figure 6. Keyness statistics on words used to describe the reasons of party policy change: Comparison of voters who are pro and voters who are against party policy change.

From this analysis, it becomes clear that those who evaluate change positively and those evaluating it more negatively have very different views about the sources of party policy change. Those who hold negative attitudes typically think about opportunistic reasons for change, and talk about parties' ‘interests’, or their willingness to stay in ‘power’. This differs markedly from the answers of those who evaluate party policy change more positively. The answers of this group of respondents stands out for their appreciation of adaptation to changing ‘circumstances’, new knowledge or ‘advancing insights’.

This analysis of respondents' answers to an open‐ended survey question complements our analysis of the individual‐level correlates of support for party policy change. Those analyses showed a strong negative effect of populist attitudes on accepting party repositioning. This association seems to emerge from the fact that many citizens do not see policy change as an indication of responsiveness to public opinion, but instead as a strategy of parties that only seem interested in staying in power. Those who evaluate policy change more positively also do not think of policy change as an indication of responsiveness to public opinion first and foremost – they more often refer to the fact that circumstances change, having in mind some exogenous factors that parties have to adapt to.

Conclusion

There are many reasons why parties alter their positions on specific issues. They can do so because of exogenous factors or new insights force them to adapt their viewpoints, because they think changing their positions will be electorally rewarding, or because they are trying to find a compromise with other parties. Although party change is prevalent across representative democracies, we know remarkably little about citizens' acceptance of party policy change.

Granted, previous work has studied the electoral effects of party policy repositioning through a focus on ideological shifts of parties – as reflected in their party manifestos (Adams & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Adams and Somer‐Topcu2009a; Meijers & Williams, Reference Meijers and Williams2020; Tavits, Reference Tavits2007). Whether such work really allows inferring how citizens respond to party policy change, however, has been called into question by research showing that shifts in party positions as captured by party manifestos do not correlate with citizens' or experts' perceptions of policy change (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Bernardi, Ezrow, Gordon, Liu and Phillips2019). Furthermore, research that has relied on experimental methods to gauge citizens' reactions to parties changing their positions faces challenges disentangling the effects of change per se and the impact of a party moving away from or towards an individual on an issue. As a result, we lack information on citizens' principled attitudes about party policy change.

To bring new insights into the acceptability of party policy change, we introduce a novel survey item that asks respondents to indicate to what extent parties should be able to change their positions. By including this question in surveys in five European democracies, we were able to show that citizens – across contexts – are rather supportive of parties' ability to alter their positions. Overall, less than 5 per cent of the respondents indicated that they thought parties should ‘never’ be able to change positions, and in each country a plurality of voters gives an answer that is closer to the ‘always’ than the ‘never’ end of the scale.

We also theorised the individual‐level correlates of party policy change, with a focus on the role of political interest, ideological extremity, technocratic and populist attitudes. While our analyses indicate that the more politically interested are more accepting of party policy change, the strongest correlate of citizens' principled acceptance of party repositioning is populist attitudes. In each of the five countries where we collected data, more populist attitudes significantly and substantively reduce the extent to which citizens accept policy change. Our analyses furthermore indicate that individuals who take extreme right positions are particularly averse to party policy change, resulting in much scepticism about party change among supporters of extreme right parties. The fact that the findings are broadly consistent across the five countries suggests that the patterns that we observe are fairly general, and would likely emerge in other established democracies too.

An analysis of an open‐ended survey item asking respondents to indicate reasons for party repositioning sheds light on the sources of individuals' views about party repositioning. While those who are on average more accepting of party repositioning more often indicate that changing circumstances and new insights sometimes force parties to adapt, those who view party change negatively more often see policy change as a power‐seeking strategy of parties that are not principled.

Our results offer important insights in the challenges that parties face when they reposition. Even though many voters understand that parties sometimes have to change their positions, and apprehend the conditions under which parties might have to adapt, citizens with populist attitudes and supporters of radical right parties are especially adverse to party policy change. For this group of the electorate, that already tends to see an opposition between ‘virtuous’ people and a corrupt elite, party repositioning risks confirming their perceptions of political elites as self‐serving actors that cannot be trusted. In settings where a diverse set of parties builds a large coalition in an effort to keep extreme right parties out of power, furthermore, the need for compromise that such coalition‐building entails can further strengthen the perception that position changes are opportunistic.

There are still open questions that our data do not provide answers to, due to the abstract nature of our measure of repositioning acceptance. First, while we find important differences in the extent to which different partisan groups accept policy change, we cannot assess whether extreme right voters – for example – are equally adverse to party repositioning when their party adapts its positions as they are when mainstream parties reposition. Second, while principled views about party policy change should theoretically shape citizens' reactions when parties alter their positions, they are only part of story. Citizens' reactions should also vary by the extent to which and how accurately they perceive real‐life party position shifts. Third, it is possible that citizens' willingness to accept policy change varies across different types of issues. Tavits (Reference Tavits2007) has demonstrated that the electoral effects of party policy shifts differs across ‘pragmatic’ and ‘principled’ issues. In other words, shifts on economic policy issues are largely left unpunished, shifts on social and cultural issue are more likely to provoke a voter backlash. This is in line with the literature on affective polarisation that has found that ideological divergence over cultural issues is a driver of out‐group hostility, whereas disagreement over economic issues is not (Gidron et al. (Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020), p. 58; see also Goren & Chapp, Reference Goren and Chapp2017). After all, whereas economic issues relate to the redistribution of resources within the community, cultural issues pertain to core questions of identity of who belongs to the community in the first place. Future studies should tackle these important questions, using our new survey instrument of principled views about party policy to push research on citizens' responses to party repositioning further.

Data Availability Statement

The data are publicly available on Harvard Dataverse at: Meijers, Maurits; Ruth Dassonneville, 2024, ‘Replication Data for: Who Accepts Party Policy Change? The Individual‐Level Drivers of Attitudes Towards Party Repositioning’, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HZAW3O.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank participants of the ‘Rendez‐vous de science politique’ at Université Laval in Québec, Canada for their enthusiastic feedback. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their insightful comments. Maurits Meijers gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Dutch Organisation for Sciences (NWO Veni Grant VI. Veni.191R.018, ‘The Reputational Cost of Party Policy Change'). We would also like to thank the anonymous referees and the editors for their constructive feedback during the review process.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table B.1: Institutional and government characteristics of countries in the sample

Figure B.1: Absolute party left–right change between CHES waves.

Table C.1: Pooled iterated principal exploratory factor analysis (orthogonal varimax rotation) of technocratic attitudes items

Table C.2: Pooled iterated principal exploratory factor analysis (orthogonal varimax rotation) of populist attitudes items

Table C.3: Iterated principal exploratory factor analysis (orthogonal varimax rotation) of technocratic attitudes items per country

Table C.4: Iterated principal exploratory factor analysis (orthogonal varimax rotation) of populist attitudes items per country

Table D.5: Summary statistics for the Pooled, German, UK and Spanish model

Table D.6: Summary statistics for the Polish and Dutch model

Table E.7: Full weighted OLS regression analysis with controls for missing answers

Table F.1: Words removed from text corpus

Figure G.1: Keyness statistics on words used to describe the reasons for party policy change.

Table H.1: Full weighted OLS regression analysis with controls

Table H.2: Full weighted OLS regression analysis per country

Table H.3: Full weighted OLS regression analysis with controls

Figure I.2: Coefficient plot for analyses with disaggregated populist attitudes scale.

Figure I.3: Coefficient plot for analyses with 5‐item populist attitudes scale (without POP6).

Table J.1: Pooled OLS regression analysis, errors‐in‐variables estimation approach

Figure K.1: Keyness statistics on words used to describe the reasons of party policy change: Comparison of voters who are pro and voters who are control party policy change in Germany (top panel) and the Netherlands (bottom panel).

Figure K.2: Keyness statistics on words used to describe the reasons of party policy change: Comparison of voters who are pro and voters who are control party policy change in Poland (top panel) and Spain (bottom panel).

Figure K.3: Keyness statistics on words used to describe the reasons of party policy change: Comparison of voters who are pro and voters who are control party policy change in the United Kingdom.