1. Introduction

The once-established view that media coverage of ongoing news occasioned “minimal effects” on voters has been replaced with a new consensus that media effects can be quite powerful through agenda-setting, priming, and framing. The current consensus has resulted from the use of experimental and quasi-experimental designs that establish stronger causal links between the media messages that voters are exposed to and changes in public opinion and political behavior (e.g., DellaVigna and Kaplan, Reference DellaVigna and Kaplan2007; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Karlan and Bergan2009; Ladd and Lenz, Reference Ladd and Lenz2009). These effects are, of course, conditional on exposure, countervailing messages, and audience factors (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992; Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Prior, Reference Prior2007). They are also constrained in increasingly polarized societies, where voters select into media “echo chambers” and “filter bubbles” that reinforce their prior political views, rather than exposing themselves to unconsidered messages and potential persuasion (Iyengar and Hahn, Reference Iyengar and Hahn2009; Stroud, Reference Stroud2010; Arceneaux and Johnson, Reference Arceneaux and Johnson2013).

In this article, we revisit the possibility of media effects in the specific case of media coverage of corporate scandals and their effects on support for regulation. We follow Culpepper et al. (Reference Culpepper, Jung and Lee2024) in theorizing that corporate scandals should generate broad support for regulatory policies that aim to remedy the shortcomings revealed by a scandal. Our expectations speak to the literature that addresses emphasis frames and narratives in persuasion (Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Aarøe, Reference Aarøe2011). Corporate scandals create a shared story about wrongdoing and its perpetrators (Guckian et al., Reference Guckian, Chapman, Lickel and Markowitz2020). They represent causal narratives—not just what happened, but also who is to blame and what policy response is demanded (cf. Dahlstrom, Reference Dahlstrom2014; Shiller, Reference Shiller2017). Narratives are capable of changing beliefs in a diverse array of political contexts (Kalla and Broockman, Reference Kalla and Broockman2020; Druckman, Reference Druckman2022). To the extent that they tell a non-partisan story, corporate scandals should be politically potent, at least with respect to related regulatory preferences in policy domains where political parties have not staked out entrenched differences.

The FTX scandal at the heart of our study, however, carried heavy political and partisan overtones. Sam Bankman–Fried, the CEO of the infamous cryptocurrency exchange FTX, who was later convicted of multiple counts of fraud, was not an apolitical CEO. In the 2022 electoral cycle, he was the second largest individual donor to the Democratic Party, after George Soros. Bankman–Fried was also a colorful character: an MIT-educated CEO, dubbed the “crypto king” and feted for his public advocacy of effective altruism. He was known as a nonconformist who lived a bohemian lifestyle with colleagues with whom he shared a Bahamian penthouse.

In the polarized United States of the present, the case of Bankman–Fried and FTX presents an intriguing puzzle for the possibility of media effects on public opinion. There was, prior to the scandal, a bipartisan lack of knowledge about cryptocurrency. These would appear to be prime conditions for a corporate scandal to trigger greater demand for regulation. Yet the public partisan ties of Bankman–Fried may influence the effect of the scandal on attitudes. Americans increasingly use their partisanship to judge the state of the economy, rather than vice versa (Egan, Reference Egan2019; Spencer and Kellstedt, Reference Spencer and Kellstedt2022). Given the combined effects of media echo chambers, motivated reasoning, and affective polarization, there is good reason to think that even a scandal in an abstruse domain, such as crypto, might be subject to partisan interpretation (Bartels, Reference Bartels2005; Nyhan and Reifler, Reference Nyhan and Reifler2010; Kirkland and Coppock, Reference Kirkland and Coppock2018; Slothuus and Bisgaard, Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2021). Since partisan motivated reasoning reflects a tendency to process new information in ways that reinforce prior partisan loyalties (Stroud, Reference Stroud2010), the more that cryptocurrency regulation becomes intertwined with partisan politics, the more likely public reactions to the scandal will diverge along partisan lines.

In early 2022, we had prepared the ground to study the real-world effects of a financial scandal, having deployed a background survey that collected baseline “pre-scandal” survey data on political attitudes from a large sample of survey-takers. We then waited to identify a sufficiently salient corporate scandal, after which we could quickly field a follow-up survey for the panel. Eventually, FTX, whose bankruptcy became public in November 2022, satisfied our criteria of a significant corporate scandal. The affair was extensively covered by the media, and the case resulted in dramatic arrests and congressional hearings. Following the scandal, we immediately returned to the same respondents for whom we had baseline data, and ran a follow-up survey, gathering responses from 2,036 respondents. Three months later, we fielded a second follow-up survey with 1,679 returning respondents. The surveys probed the extent of participants’ exposure to the scandal and measured participants’ post-event support for regulating cryptocurrency.

Alongside the many benefits of this pre- and post-design are legitimate concerns about how self-selection into the scandal exposure condition may distort the results. We therefore complemented our observational study with a two-wave survey experiment, in which a fresh sample of 968 respondents from the United States completed both waves. This survey was in the field at the same time as our second observational study. Study subjects were randomly assigned to read either authentic media coverage of the scandal or a control article, thus giving us causal leverage on the effect of exposure to scandal news coverage on policy preferences. This meant that our experimental subjects—though they obviously came into the experiment from different informational environments and with their own media experience—were all exposed to exactly the same coverage of the scandal immediately before we asked their views about regulating cryptocurrency.

This difference turned out to be decisive. Our combined observational and experimental design reveals striking differences in the way that prior political attachments influence the effect of the scandal across the two different studies. In the experimental study, in which everyone got the same treatment, we find that only those who identify as strong Republicans are moved by the scandal to demand greater crypto regulation, while the attitudes of Democrats remain unmoved by the scandal. Yet in both observational studies, whose participants were exposed to very different accounts of the scandal and interpretations of why it happened, the exact opposite is true: for those who identify as Democrats (but not Republicans), exposure to the scandal elicited significantly higher support for crypto regulation. These findings suggest that exposure to scandal news reinforces existing partisan divides in media exposure.

Diving deeper into the media consumption habits of the participants in our observational sample, we find evidence that the diverging partisan reactions stem from the fact that partisans came to interpret the events through ideologically tinted glasses. Progressives focused in on the lax regulatory environment and the need to prevent future crises, while conservatives zeroed on the moral failings of Bankman–Fried. These views were consistent with differential media coverage of the scandal in outlets of the left and the right.

2. Corporate scandals, partisan processing, and support for regulation

Why should we believe that corporate scandals have any effect on politics? Consider the once-boring question of data privacy. Data privacy was elevated onto the political agenda in the European Union and the United States after the leaks by whistleblower Edward Snowden in 2013, and then again by the revelations about the harvesting of Facebook users’ data by the political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica in 2018 (Culpepper and Thelen, Reference Culpepper and Thelen2020; Antoine, Reference Antoine2023). In both cases, scandals around the activity of private corporations drove a technical issue onto the political agenda. In the aftermath of media coverage of scandals, we might find dramatic shifts in public opinion (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005; Culpepper et al., Reference Culpepper, Jung and Lee2024).

Political scientists remain skeptical that political scandals can shift policy preferences because of the influence of partisan motivated reasoning, which largely shapes voters’ reactions to events (Taber and Lodge, Reference Taber and Lodge2006; Lodge and Taber, Reference Lodge and Taber2013; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Harell, Stephenson, Rubenson and Loewen2023). In the polarized environment of the United States, voters tend to select their media outlets according to their partisan leanings, discounting information that clashes with their partisan priors (Bennett and Iyengar, Reference Bennett and Iyengar2008; Arceneaux et al., Reference Arceneaux, Johnson and Murphy2012). In an environment of affective polarization, even clear acts of wrongdoing can be interpreted in a way that reinforces partisan beliefs (Rothschild et al., Reference Rothschild, Keefer and Hauri2021).

Several mutually reinforcing mechanisms account for partisan-motivated responses to media events. First, voters actively seek information in line with their preexisting attitudes (Iyengar and Hahn, Reference Iyengar and Hahn2009; Stroud, Reference Stroud2010; Garrett and Stroud Reference Garrett and Stroud2014). This selection process is amplified by partisan media outlets that favor coverage of the other party’s scandals (Puglisi and Snyder Jr, Reference Puglisi and Snyder2011). Even scandals that break through media silos are interpreted through a partisan lens that reinforces existing views and avoids dissonance (Taber and Lodge, Reference Taber and Lodge2006). The interpretative bias might involve uncritically accepting attitude-consistent messages, or indeed people’s attitudes might polarize when confronted with information perceived as challenging their partisan priors (Lodge and Taber, Reference Lodge and Taber2013).

Partisan motivated reasoning is potentially further fueled by the ability of causal narratives to shape public opinion. Narratives are components of the information environment that describe causal relations, which place the facts of a situation in a sociopolitical context (Dahlstrom, Reference Dahlstrom2014; Shiller, Reference Shiller2017; Eliaz and Spiegler, Reference Eliaz and Spiegler2020). Kendall and Charles (Reference Kendall and Charles2022) suggest that narratives guide policy choices more than facts and data. When it comes to corporate scandals, then, ideologically-anchored perceptions of the underlying cause of the scandal, and not the malfeasance itself, may be the stimulus for evaluating one’s policy positions (Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2015). The left and the right may agree on an objective act of corporate villainy, but they may still disagree about the underlying reasons that villainy took place.

By the logic of motivated reasoning, corporate scandals should have little effect on policy preferences, particularly where the protagonist is closely associated with one political party. Conservatives and progressives will continue to support partisan policy positions. The negative valence that accompanies corporate misbehavior will be subsumed into people’s thinking in a way that reinforces, and does not necessarily shift, their preconceived notions.

Against this view, corporate scandals have the potential to break through the feedback loops of motivated reasoning for several reasons. For one thing, scandals are mediatized focal events that, by definition, require publicity. What makes a story scandalous is its revelatory quality: what was once private and unknown, or known only to insiders, is made public and widely discussed (Thompson, Reference Thompson2000; Adut, Reference Adut2008; Nyhan, Reference Nyhan2014). Under such circumstances, strong partisans cannot simply dismiss clear acts of malfeasance. Studies show that facts that are clear-cut, rather than ambiguous and permissive of multiple competing interpretations, constrain motivated reasoning (Parker-Stephen, Reference Parker-Stephen2013).

Second, corporate scandals may avoid the centrifugal force of motivated reasoning because they are not typically explicitly political. Frames, narratives, and objective economic realities matter, and public opinion can be quite responsive to external events that can break through the media cycle (Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007). A series of experimental studies looking at corporate scandals has corroborated this view. Culpepper et al. (Reference Culpepper, Jung and Lee2024) found that media coverage of banking scandals can have an identifiable effect in moving voters’ preferences in favor of greater regulation—both among left- and right-leaning individuals. Likewise, Ahlquist et al. (Reference Ahlquist, Copelovitch and Walter2020) confirm that economic shocks cause exposed individuals to shift policy preferences in a uniform direction, regardless of partisanship.

Third, media coverage of corporate scandals tends to utilize strong frames that complement the sensational content innate to scandals (Nicholls and Culpepper, Reference Nicholls and Culpepper2021). Narratives with a clear perpetrator and relatable victims form a persuasive lever that is prone to influence beliefs (Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007). Much of the media coverage of corporate scandals emphasizes differences between regular people and greedy elites. Massoc (Reference Massoc2019) and Münnich (Reference Münnich2017) demonstrate that anti-corporate sentiment can be mobilized on the back of antagonistic anti-finance narratives in the public domain. Given that populists of the left and right both attack greedy elites who profit off a rigged system, corporate malfeasance narratives speak equally to voters regardless of partisan persuasion (Müller, Reference Müller2016; Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019).

Fourth, the policy questions that surround corporate scandals relate to complex and technical issue areas, where voters are less fixed in their views. These tend to be what Carmines and Stimson (Reference Carmines and Stimson1980) call “hard” issues, about which voters do not have a visceral response or long-standing opinion. Cryptocurrency, which was not a heavily politicized issue before the outbreak of the FTX scandal, is not subject to the freezing or polarization of attitudes that scholars observe around highly salient issues, such as immigration (Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Hainemueller, Hangartner and Helbling2015; Berk, Reference Berk2025). The media coverage of scandals can also overcome voters’ low levels of information on economic regulatory policies and thus shape their subsequent attitudes (Baden and Lecheler, Reference Baden and Lecheler2012).

The conflicting dynamics of motivated reasoning and strong scandal narratives give rise to competing hypotheses. One is the partisan motivated reasoning hypothesis. If it is true that voters begin with clear partisan preferences for or against economic regulation, and then map the scandal event onto their beliefs, we should expect no independent effect of exposure to corporate scandals on policy preferences. Specifically, voters identifying with anti-regulation parties will construe the scandal as a nonevent, and their degree of support for regulation will not change as a result. Alternatively, partisans may be genuinely shocked by scandals, but they will nonetheless form judgments that are consistent with their ideological priors (Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2015). In the case of support for regulation, that would mean that partisans of the right would not blame failures of regulation as a cause and would not demand more regulation as a consequence. Either way, the predictions of the partisan motivated reasoning hypothesis are the same.

A second, alternative possibility is the uniform scandal shock hypothesis. Considering that corporate scandals are strong frames with clear wrongdoers and easily accessible solutions, exposure to the event should generate pro-regulatory sentiment across the board. Furthermore, voters typically do not have known priors about any partisan leanings of the firms and executives behind corporate scandals. Thus, even if voters were primed to engage in motivated reasoning, they are unlikely to be exposed to partisan cues in the initial unfolding of a corporate scandal. This leaves us with two hypotheses:

H1 (motivated reasoning): Exposure to scandal will increase support for cryptocurrency regulation only among voters of the left, not among voters of the right.

H2 (uniform scandal shock): Exposure to scandal will increase support for cryptocurrency regulation among all voters.

3. The FTX scandal

The challenge of studying the effect of a specific real-world event, like a corporate scandal, on political attitudes is that we do not know when an event will happen. While corporate misconduct is ubiquitous, not all business misconduct generates such concentrated media attention that it reaches the level of a scandal, with the potential to activate public opinion (Thompson, Reference Thompson2000; Adut, Reference Adut2008). Timing our observational data collection to the outbreak of a new scandal is an innovative feature of our study. In 2020, we collected extensive baseline data on regulatory preferences and political attitudes from respondents in six countries—Australia, France, Germany, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and the United States.Footnote 1 These data provided a robust set of “pretreatment” information that would serve our observational study, while the multicountry scope offered us the flexibility to exploit scandals that might appear in any of these countries. For this baseline data collection and subsequent studies, we turned to YouGov to draw representative samples of each country’s population by using a quota system that matched the sample demographics to the national population.

We then pre-commissioned a series of follow-up surveys with YouGov and established an “early warning” system to identify potential scandals that were registering with the public. Then we waited. A team of research assistants tracked events in all six countries, recording media items that involved corporate malfeasance. Potential scandals needed to surpass a certain threshold of media attention to have the possibility of shifting support for regulatory change. We assessed the magnitude of breaking stories by using Twitter’s (then available) API to track the frequency of Tweets featuring keywords associated with a given scandal, and Google Trends to observe keyword searches related to that scandal. The FTX bankruptcy scandal ticked all the boxes. It generated critical front-page media coverage in the United States that lasted for several weeks and led to intense public scrutiny.

We provide further details about the early warning system in Online Appendix A. At its peak in early 2022, FTX was the second-largest cryptocurrency exchange in the world, valued at more than $32 billion. Its founder, Sam Bankman–Fried was lauded as a wunderkind responsible for revolutionizing financial markets and facilitating mass access to cryptocurrencies. On November 11, 2022, FTX and its affiliates filed for bankruptcy. The catalyst of the event was a revelation about the balance sheet of FTX and its sister trading firm Alameda Research, which precipitated a liquidity crisis at the exchange, as investors tried to withdraw their funds. Despite fevered efforts to find a savior, the organization’s finances cratered.

Creditors eventually appointed John Ray as the replacement CEO, who had led energy trading firm Enron through bankruptcy proceedings years before. Ray was horrified by the extent of the mismanagement at FTX, noting that “never in my career have I seen such a complete failure of corporate controls and such a complete absence of trustworthy financial information as occurred here.” The bankruptcy proceedings revealed that FTX had over one million creditors and liabilities of up to $8 billion. Creditors included a mixture of global financial firms along with hundreds of thousands of retail investors.

Ex-CEO Sam Bankman–Fried was arrested in the Bahamas and extradited to the United States in late December. After the scandal broke, polls conducted by The Economist found that 70% of Democrats and 71% of Republicans believed that Bankman–Fried should be convicted—demonstrating that his guilt was a source of rare bipartisan agreement (Economist/YouGov Poll, 2022). The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Department of Justice launched investigations. In November 2023—after both our studies had already been completed—Bankman–Fried was convicted by a US Federal Court in New York on seven counts of fraud and conspiracy. He was later sentenced to 25 years in prison.

3.1. Dependent variable: support for cryptocurrency regulation

To assess the effect of the FTX scandal on the demand for regulation of cryptocurrency, we needed a measure of public support for cryptocurrency regulation, something that we did not find in the established literature. As a result, we first developed and validated such a measure in a survey fielded immediately following the outbreak of the scandal. We fielded a battery of items to capture a range of attitudes toward the major threads of discussion around cryptocurrency regulation. The final scale, which we used across the observational and experimental studies, contained three items that capture different elements of the regulatory debate, such as government control of money (“any digital currency should be under the control of government or the Federal Reserve”) and consumer protection (“Regulators should ensure that cryptocurrency exchanges provide customers with sufficient information about the risks of investing”). All items were answered on a five-point scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, and the internal consistency was reasonably high, with Cronbach’s α scores ranging from 0.71 to 0.76 across the studies. Online Appendix B provides the full list of items, along with analyses confirming the internal validity and multidimensional coverage of the scale.

4. The observational study

Our observational study used a multi-wave panel format. We first collected baseline data on regulatory preferences and political attitudes—before the FTX scandal occurred (the pre-scandal wave). After the scandal broke, we distributed two post-scandal waves of surveys. The first post-scandal wave was distributed from November 22 to December 5, 2022, immediately after the scandal. This first post-scandal wave (N = 2,036) established immediate reactions to the scandal. Our second post-scandal wave was distributed from March 7 to 27, 2023 (N = 1,679). This second survey gathered additional information about the specific media sources through which respondents had learned about the scandal and also asked respondents about the perceived cause of the scandal. It also allowed us to see if the informational effects of real-world scandals were only fleeting or if they could be observed several months later (Seimel, Reference Seimel2025).

4.1. Independent variable

The foremost challenge in an observational study of this sort is to determine which participants were “exposed” to the scandal. In experimental settings, exposure is a property entirely controlled by researchers. In observational settings, the notion of what constitutes exposure is more amorphous. In this study, we operationalize “exposure” to the scandal by measuring whether respondents were aware of the scandal at the time of the survey, following recent research that classifies individuals as being exposed to external stimuli based on their awareness of media events (Shandler and Gomez, Reference Shandler and Gomez2023). Respondents were asked to identify which of five events had been in the news in the preceding weeks. Sixty-six percent of respondents correctly identified the FTX scandal, and this group is designated as the exposed sub-sample.

We also measure the depth of knowledge of the incident. While the scandal constituted a significant media event that attracted widespread attention, people naturally possess varying levels of knowledge about its details. Therefore, we collect a secondary variable that we label depth of exposure. Among those respondents who successfully identified the existence of the scandal, we followed up with a series of three additional questions to measure the extent of their knowledge. The distribution of exposure and depth of exposure variables appears in Figure 1, and all questions appear in Online Appendix C.

Figure 1. Distribution of depth of exposure to FTX scandal.

For clarity’s sake, in our main analyses, when we refer to exposed and unexposed subgroups, we refer to anyone who scored above a 0 in Figure 1 as exposed (i.e., people who answered the first question correctly, indicating a basic awareness of the scandal), and anyone who scored 0 as unexposed (i.e., those who weren’t even aware of the occurrence of the scandal).

4.2. Analytical strategy

The nature of the observational study means that we must contend with legitimate concerns about selection into our scandal exposure category. Indeed, balance checks reveal differences across the exposed and unexposed groups for age, gender, income, political knowledge, and news consumption. To mitigate concerns about selection bias, our analysis proceeds in the following steps. We examine whether those exposed to the FTX scandal exhibit different levels of support for crypto regulation compared to unexposed groups, while controlling for those variables that predict scandal awareness. Later, we also report the results of an exact matching technique that tests the robustness of our results with artificially balanced treatment groups.

5. Observational post-scandal wave 1 results

Who are the people exposed to the scandal? What predicts whether a person is likely to develop awareness of a corporate media scandal in a way that they become susceptible to exposure effects? In Table 1, we compare the characteristics of exposed and unexposed subgroups. Unsurprisingly, news consumption, news attentiveness, general political knowledge, and income are all predictive of scandal-awareness. We control for each of these covariates in our subsequent modeling. The full regression tables appear in Online Appendix D.

Table 1. Balance checks for scandal awareness

Note: Political orientation is recorded on an 11-point scale with 11 denoting the most right-wing; education is measured on a four-point scale; income is measured on a 10-point scale; the crypto investor variable is a binary variable where 1 signifies investor status; attentiveness to news is measured on a 10-point scale; the news consumption variable is measured on an 8-point scale; the max. score for political knowledge is two. The Diff column shows p-values from ordinal linear regressions testing whether exposed and unexposed populations differ on each variable.

We next examine direct exposure effects, comparing support for crypto regulation among exposed and unexposed participants. Exposed participants exhibited an average level of support for crypto regulation of 3.76 on a 5-point scale, while the mean score for unexposed participants was 3.68. This difference is marginally significant (ß = 0.08, p = 0.069), with scandal awareness being associated with a stronger level of support for regulating the cryptocurrency industry. This difference persists (and even increases) when we control for a battery of associated covariates.Footnote 2

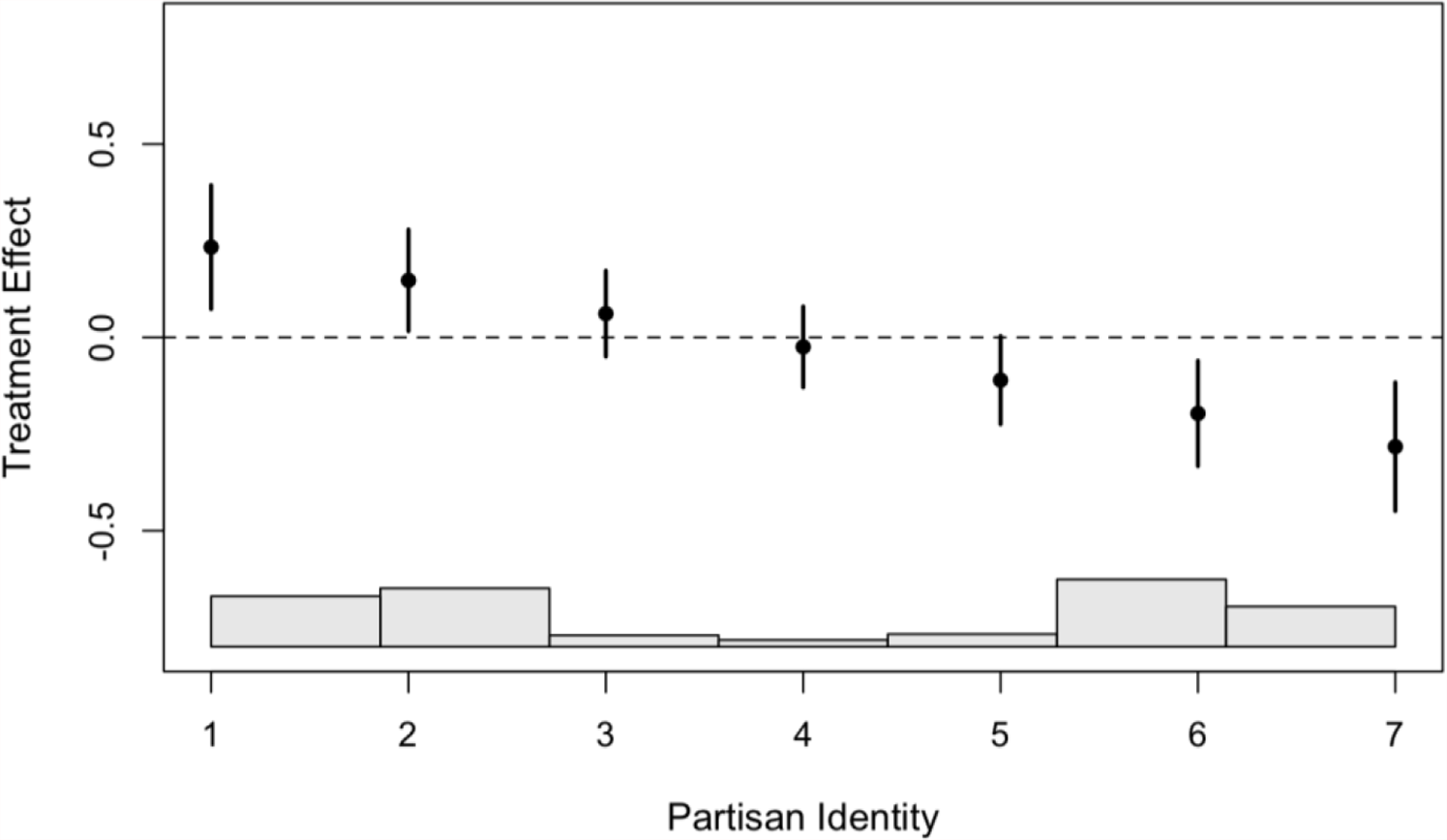

On its face, these results suggest that people exposed to corporate scandals evince more pro-regulatory attitudes in the issue area connected to the scandal. Yet people are not exposed to news stories in a vacuum. They bring with them expectations and attitudes that inform their interpretation of events. To probe the role of partisan interpretation, Figure 2 interacts scandal awareness and partisan identity (measured on a 7-point scale, with 1 denoting strong Democratic identifiers and 7 denoting strong Republican identifiers).

Figure 2. Effect of scandal awareness on support for crypto regulation by partisan identity.

We find a significant interaction effect of partisan identity and crypto regulatory attitudes (interaction effect: ß = −0.09, p = 0.000). Democrats exposed to the scandal experience a strong and statistically significant effect (mean Democrat effect = 0.19), while Republicans experience an equally significant but negative effect (mean Republican effect = −0.21). In these results, hypothesis H1 finds support.

In the online appendix, we conduct a series of robustness tests to test the sensitivity of our results to differently specified models. In Online Appendix G, we re-create our “exposure” variable according to several different specifications to ensure that our observational findings are not a product of our design choices. In Online Appendix H, we conduct a matching analysis that re-analyzes our findings using a reduced, artificially balanced dataset of 1,361 respondents. The analyses confirm that our results are not a product of observational design choices.

6. Observational post-scandal wave 2 results

The results of our first observational wave suggest that Democrats and Republicans react differently to a corporate scandal with political undertones. Yet partisanship is closely associated with other attitudes and behaviors, and the observational nature of the study means that it’s impossible to disentangle partisanship from other political behaviors, such as news consumption habits. To delve deeper into the interpretative process of Democrats and Republicans, we conducted a follow-up survey with the same participants between March 7 and March 27, 2023. During the follow-up survey, we captured fine-grained information about participants’ beliefs about the FTX scandal and the specific news sources where they learned about the scandal.

After replicating the results of the preceding wave,Footnote 3 respondents were then asked to select which of four possible statements described the cause of the FTX scandal. Respondents were permitted to select multiple options. Table 2 presents the percentage of respondents who agreed with each possible cause, broken down by Democratic and Republican identifiers.

Table 2. Perceived causes of FTX scandal

Note: The table shows the percentage of respondents who agree that the item listed is a cause of the scandal. Since respondents were allowed to select zero or multiple causes, the total percentages do not sum to 100%.

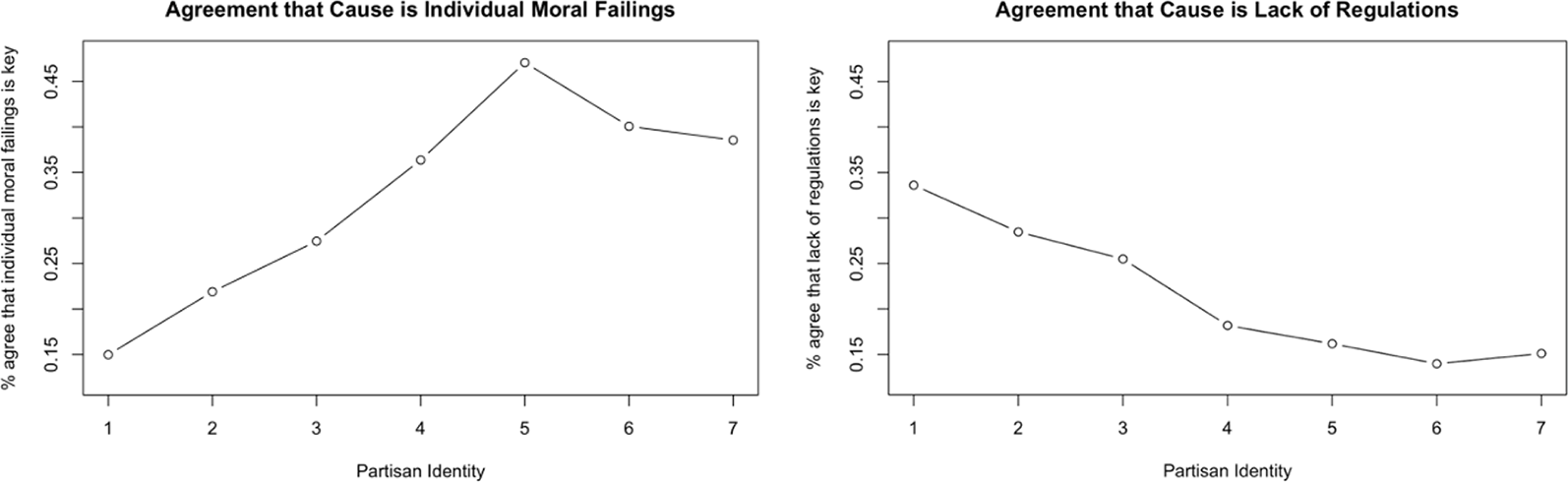

We observe a clear divergence in the way that Republicans and Democrats see the root cause of the scandal. A plurality of Republicans (41%) viewed the FTX bankruptcy as being due to the individual moral failings of company executives; the equivalent figure for Democrats was only 18%. If the cause of the event is individual misbehavior, it stands to reason that additional regulations would not have precluded the scandal. Democrats are more likely than Republicans (31%–14%) to view the cause of the scandal as being a lack of sufficient regulation, which is consistent with Democratic support for imposing additional regulation.

In Figure 3, we plot the level of agreement with the two most popular causes (a lack of sufficient regulation and individual moral failings) by partisanship. The trend lines move in completely opposite directions. While only 15% of strong Democrats agree that the scandal was caused by individual moral failings, up to 47% of strong Republicans support this interpretation. The picture is the opposite when it comes to a lack of regulation, with up to 34% of Democrats adopting this view compared to 15% of Republicans.

Figure 3. Agreement with FTX scandal causes by partisan identity.

Did partisans interpret the scandal through a preexisting ideological filter? Or did they instead learn about the event through partisan media echo chambers that pushed divergent narratives? We find evidence that both mechanisms may be at play. At the end of the questionnaire, we asked the subset of exposed participants to list the media source from which they learned about the scandal. The question was open-ended, and we received 535 unique responses (the full list of responses appears in Online Appendix J).Footnote 4 Using the AllSides Media Bias Ratings,Footnote 5 we categorized the media sources as left-leaning, right-leaning, or unknown/non-biased. Where respondents indicated multiple sources, we assign them to the first source on their list. In all, 310 people were exposed to the scandal through left-leaning media outlets, 208 through right-leaning outlets, and 392 through non-media sources (i.e., word of mouth) or from media sources with no discernible partisan bias.

News and commentary on the FTX scandal had a very different emphasis in media outlets associated with the right and the left. Those on the right often mentioned Bankman–Fried’s political connections to the Democrats. Thus, the Wall Street Journal thought it likely that “Bankman–Fried’s $36 million in donations to Democratic causes bought him political protection” (Finley, Reference Finley2022). Fox News pithily summarized the scandal thus: Bankman–Fried diverted FTX “funds to another company without telling anyone, and from there, he made a bunch of undisclosed investments, lavish real estate purchases, [and] huge political donations to Democrats in time for the midterms, of course” (Gutfeld, Reference Gutfeld2022).

Media outlets on the left did not defend Bankman–Fried, but they stressed more heavily the lack of regulation of the crypto markets. The New York Times prominently featured a quotation that the “lack of transparency and regulation of Mr. Bankman–Fried’s businesses should have been a bright red flag early on” (Goldstein and Stevenson, Reference Goldstein and Stevenson2022). An MSNBC commentator claimed that “a lot of the problems that arose out of the recent catastrophe are due to the lack of regulation of these products” (Aleem, Reference Aleem2022).

These examples illustrate a systematic difference in the way that news outlets on different sides of the political spectrum covered the FTX scandal. To demonstrate this, we conducted a dictionary analysis of all articles published online between November 11, 2022, and January 12, 2023, the two months immediately following the scandal. We identified the proportion of articles that explicitly mentioned words associated with the theme of morality and of regulation in four outlets: two of the right (Wall Street Journal and Fox News) and two of the left (New York Times and MSNBC).Footnote 6 As Figure 4 makes plain, news outlets on the left featured regulation frames much more prominently than morality frames; news outlets on the right, by contrast, were far more likely to discuss morality than regulation.

Figure 4. Proportion of morality and regulation frames in FTX coverage among left- and right-leaning news outlets.

In Table 3, we disaggregate participants’ level of agreement with the two predominant perceptions of the FTX scandal’s cause by political orientation and by the partisan lean of the media source from which they learned about the event. First, consider right-wing respondents who learned about the scandal from left-leaning news sources, those in the fourth row of Table 3: only 35% of this sub-group of right-leaners buy the argument that individual moral failings were the root cause of the scandal—far fewer than their partisan peers who learned about it from right-leaning sources (59% agreement) or unknown sources (54% agreement). This suggests that at least part of the causal message may have been transmitted through a media ecosystem.

Table 3. Cause of the scandal due to the partisanship of respondent and news source

Note: Table includes only those respondents who were aware of the scandal, were on the left or right, and identified a source of news clearly on the left or right. The full table of all respondents is included in Online Appendix K.

We observe the same trend when looking at the partisan breakdown of those who think that a lack of regulation caused the FTX scandal. Twenty-six percent of right-wing Americans who learned about the scandal from liberal news sources identify a lack of regulation as a root cause of the event, far more than other right-wing Americans who learned about the scandal from in-party or unknown news sources (12% or 10%, respectively).Footnote 7

The same trend plays out among liberal Americans, just in reverse. Liberals who learned about the scandal from non-left media sources are far less likely to adopt the partisan perspective that a lack of regulation is the root cause of the scandal. Table 3 shows that one quarter of those on the right who got their news from a left source believe that lack of regulation is the cause—essentially the same percentage as those on the left who got their news from a right source (this latter group is however tiny). We lack the power to test whether the different beliefs among partisans who consume news from the other side of the partisan aisle are associated with correspondingly moderated support for regulation. But the symmetrical effect we observe on beliefs among those in this category on the left and right suggests that future research should examine whether these effects translate into symmetrical changes in support for a given type of regulation (cf. Broockman and Kalla, Reference Broockman and Kalla2025). We can conclude from these results that media ecosystems play a key role in the ideologically sorted scandal effects that we observe.

7. The experimental study

Observational studies offer the advantage of high realism, capturing respondents’ self-selection of news outlets. However, observational studies have drawbacks, including strong assumptions about unobserved confounders. Therefore, to complement our observational studies, we fielded a two-wave survey experiment to assess the effect of scandal coverage on regulatory preferences.

7.1. Research design and independent variable

We conducted the preregistered experimental study in two waves in March–April 2023, at roughly the same time as our second post-scandal observational wave. In the first wave of the experimental study, fielded March 9–23, we recorded respondents’ baseline levels of support for cryptocurrency regulation and collected sociodemographic and attitudinal variables. There were no experimental treatments during this first wave. The second survey wave was distributed 11 days after the first, and we randomly assigned respondents to read an article about the FTX scandal or to a control group that read a neutral news story. Following the treatment, respondents once again answered questions about their support for cryptocurrency regulation. A total of 968 participants completed both waves of surveys.

The scandal treatment was distributed in the form of a newspaper article about the FTX scandal. We developed a composite story using language from news and op-ed articles that had appeared on websites that are both left- and right-leaning: the New York Times, New York Post, and CNN. The article explains how FTX engaged in one of the biggest financial frauds in American history, the dramatic downfall of Bankman–Fried, and the losses of more than $8 billion. Consistent with left-leaning media coverage, the treatment article expounds on how the unclear regulatory environment set the scene for fraud to occur. Consistent with coverage of the right, the treatment discusses the “secret” backdoor Bankman–Fried had ordered created to divert money from clients. Importantly, the article was presented without a logo, meaning that participants could not associate the text with a specific news organization. An abridged picture of our scandal article appears in Figure 5, and full copies appear in Online Appendix L.

Figure 5. Screenshot of the scandal article.

The control article reports dispassionately about the business strategy of a company (Office Depot). We intentionally designed our control articles to include commercial content to ensure that it is the scandal narrative driving opinions and not the mere mention of business.

7.2. Covariates

As part of our initial data collection during Wave A, we gathered data relating to financial behavior, political attitudes, and demographics. Covariates include age, gender, income, education, political orientation, partisan identity, political knowledge, and news consumption. Information on the scales and sources of all measures appears in Online Appendix M.

8. Experimental study results

To test how exposure to media coverage of the FTX scandal influences regulatory attitudes, we regress support for crypto regulation on our treatment condition (assignment to the FTX scandal article). Exposure to the scandal significantly increases support for crypto regulation by 0.11 units on a 5-point scale (β = 0.11, p = 0.05).Footnote 8 The average effect size corresponds to 13% of the standard deviation of the outcome. This effect size is comparable to that of a six-unit shift in income deciles, a variable that commonly predicts attitudes toward financial issues. The effect size is also remarkably similar in magnitude to that found in the observational study. The data confirm our preregistered expectation that media reports of corporate scandals cause the public to adopt stronger pro-regulatory views in that domain.

Nevertheless, as in our observational findings, the positive direct effect masks partisan differences that emerge in our experimental data, which we did not preregister. We expected that we would find effects consistent with the uniform shock hypothesis (H2), which is to say that exposure to media coverage of scandals would spur a change in support for crypto regulation across members of all political parties. Yet, as in the observational study, we found that partisan identity moderated the treatment effect, but in the opposite direction.Footnote 9 Our moderation analysis, shown in Figure 6, interacts the treatment assignment with partisan identity, measured during the non-experimental first wave on a seven-point scale (1 = strong Democrat, 7 = strong Republican). The analysis indicates that our strong treatment effect is concentrated among the most Republican-identifying respondents (interaction effect: ß = 0.06, p = 0.036). Specifically, Republicans (indicating a mild or strong association with the Republican party) exhibited an average treatment effect of 0.23 units, while Democrats were not influenced at all.

Figure 6. Effect of scandal treatment on support for crypto regulation by partisan identity (US).

Why does our treatment shift Republican attitudes more than Democratic attitudes when our observational waves found that Republicans were more resistant to crypto regulation? The answer we propose is that Republican resistance is not entirely baked into partisan identity. In fact, it is partly a function of the media ecosystem to which they belong. In our observational studies, we confirmed that Republicans who learned about the scandal through left-leaning media sources were more likely to assign blame for the scandal to a lax regulatory environment. In our experimental study, the treatment article made that same point, suggesting that Republicans who hear more about the regulatory interpretation may come to share it.

The evidence about partisan media driving the way that people interpret the FTX scandal raises the prospect that our experimental findings may simply be the artefact of people’s pretreatment exposure to partisan media narratives (Druckman and Leeper, Reference Druckman and Leeper2012). Indeed, it is reasonable to ask whether we found no treatment effects among Democrats in the experimental study because their attitudes already aligned with their pretreatment exposure to left-leaning news stories in the weeks before our survey was fielded. There is some evidence for this conjecture, with our data showing that Democrats were initially more supportive of crypto regulation than Republicans, with baseline attitudes already above 4.18 on a 5-point scale in the pretreatment wave (compared with Republicans’ baseline level of 3.78). This suggests that perhaps ceiling effects may be at work for Democratic participants, although we emphasize that this possibility is post-hoc rather than a direct test of our theoretical expectations. Nevertheless, when we re-run our experimental interaction analysis among only those respondents who were unaware of the FTX scandal at the time of the survey, and who therefore seem unlikely to have received any pretreatment exposure, we find the same results as in our general analysis, with only Republicans exhibiting a positive treatment effect. Whatever the case may be, our one-shot treatment increased Republican demand for crypto regulation while leaving the regulatory attitudes of Democrats unchanged.

9. Conclusion

We examined the effects of the FTX scandal on attitudes toward cryptocurrency regulation using a multi-wave observational study, complemented by a two-wave survey experiment. Across these different studies, we find that exposure to information about the scandal marginally increases support for regulating cryptocurrency. This effect, however, masks partisan variation in responses to the scandal. In the observational studies, Republicans remained unmoved by exposure to news of the FTX scandal, while Democrats exposed to news of the scandal were more pro-regulation than those who were not. In the experimental context, we received results that diverged from the observational results and contradicted our preregistered hypotheses: exposed Republicans shifted in favor of crypto regulation, while those who identified as Democrats showed no effect.

Voters’ self-selection into a given media environment is a core part of the phenomenon we wanted to explore in our observational study of media effects during corporate scandals, and not a bug to eliminate through randomized treatment allocation (cf. de Benedictis-kessner et al., Reference de Benedictis-kessner, Baum, Berinsky and Yamamoto2019). We have gathered suggestive evidence that in the wake of the FTX scandal—a corporate scandal with an explicitly partisan protagonist—American voters on the left were more likely to point to a lack of regulation as the cause of the scandal. And the natural response to a lack of regulation is more regulation, which is what Democrats wanted after the scandal. Republicans, on the other hand, homed in on individual moral failings of Democratic donor Sam Bankman–Fried as a root cause of the fiasco. And they did not change their level of support for crypto regulation.

While our data on media consumption are imperfect, they are consistent with a story in which partisan news narratives about a corporate scandal shape what one thinks about the scandal. In our case, a partisan bent in media sources is today’s variant on Marshall McLuhan’s dictum that “the medium is the message.” Our observational results suggest that left- and right-leaning media create narratives of scandal response that reinforce the underlying ideological predispositions of their core consumers. The right, which trumpets individual choice and responsibility, blames the individual greed of a Democratic donor for being at the root of the crisis. The left, which calls on the state to correct market failures, looks to the state to respond to a scandal with new regulation.

It is a popular feature of modern political science scholarship to assume that the gravitational pull of motivated reasoning overwhelms the effects of frames, narratives, and external events (Slothuus and De Vreese, Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010; Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). However, our findings suggest that corporate scandals, even one as politically freighted as FTX, have the potential to free voters from this gravitational pull. Voters on the right who got their news about the FTX bankruptcy from a left-leaning source, like the New York Times, were twice as likely to believe that a lack of regulation caused the scandal compared to co-partisans who got their news from right-leaning or unknown news sources. This result is consistent with Broockman and Kalla (Reference Broockman and Kalla2025), who find that having Fox News viewers watch coverage from left-leaning CNN led to a moderation of their political views. Partisan narratives appear to have an effect beyond co-partisans.

Some corporate scandals have effects that cut across the political spectrum. The collapse of the energy company Enron in 2002 temporarily created bipartisan support for campaign finance reform (Cigler, Reference Cigler2004) and significant changes to corporate governance laws (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005). Similar to these cases, our cryptocurrency case study may generalize to other scandals in technical domains that prompt the public to engage with unfamiliar aspects of policy on which many of them do not have firmly fixed views. Corporate scandals in other words, are likely to influence opinions on “hard” issues more so than on “easy” ones (cf. Carmines and Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1980). However, our study further suggests that the partisan undertones of otherwise low-salience corporate scandals probably made such a significant cross-partisan effect less likely. Our observational study meant that we were unable to choose what sort of scandal would break out while we were poised to study its effects. The FTX scandal ultimately did not precipitate a rush to regulate the cryptocurrency market. FTX broke existing laws, and those laws were sufficient to successfully prosecute the firm’s founder, Sam Bankman–Fried. This ambiguity, and the partisanship of Bankman–Fried himself, probably makes the emergence of the partisan scandal reasoning we have observed more likely, though that is an empirical question that requires further research in the future.

Whatever the next big corporate scandal is, our findings suggest that the narratives different partisan media outlets present about it will have important effects. They will determine whether the scandal leads to seismic political change, like Enron and Cambridge Analytica, or instead becomes reabsorbed into the motivated reasoning of partisan politics, as cryptocurrency emphatically has in the wake of the FTX scandal.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.10079.

Data availability statement

Full replication files and all accompanying datasets are available in the PSRM Dataverse.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jae-Hee Jung, two anonymous reviewers, and the editors of PSRM for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. Hayley Pring provided valuable research assistance, for which we are extremely grateful. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 787887). This paper reflects only the authors’ views and not those of the ERC. This project received ethics approval from the University of Oxford (BSG_C1A-19-10).