A student who began the study of Platonic philosophy in Alexandria in Egypt in the early sixth century ad would learn that philosophy was divided into two branches, practical and theoretical, that is, knowledge concerning praxis, human action in this material world, and theoria, that is, knowledge of the natural world and its transcendent causes, a knowledge which was thought to be the highest accomplishment of human reason and its felicity. Practical philosophy, the student would learn, was itself divided into three: ethics (concerning the individual), ‘economics’ (an ethics of the household) and political philosophy (concerning the community, city, state). Theoretical philosophy, it was explained, also had three branches: physics, mathematics, and metaphysics (or ‘theology’, as this science was called, the ‘science of the divine’). It was proposed that these sciences be studied in a first cycle by reading the corresponding treatises of Aristotle, and, in a higher cycle, by reading a selection of ten dialogues of Plato which were held to correspond to the sciences and which led finally to two Platonic dialogues (the Timaeus and the Parmenides), two dialogues believed to encapsulate and crown the whole course of study. Prior to beginning this curriculum, the student would be initiated to logic, considered to be an instrument (organon) of philosophy, by reading Aristotle’s texts on logic.Footnote 1

We can suppose that students in Alexandria would have followed this very ambitious programme of study to varying degrees. Their teachers, trained both in Alexandria and in the famous school of Platonic philosophy in Athens, would have completed the whole curriculum and they would have expected this of their better students. Ammonius, for example, who taught in Alexandria at the end of the fifth century, had studied with the great Proclus (†485) in Athens, who himself had gone through the complete curriculum with his predecessor as head of the school in Athens, Syrianus. The curriculum, as practised in the school of Athens in the fifth century, goes back in large part to the educational programme instituted by Iamblichus in his school of Platonic philosophy in Apamea in Syria in the late third/early fourth century, a programme presumably followed in part at least by those of his students who themselves set up schools in Asia Minor.

The philosophical training proposed in these schools was not simply aimed at the transmission of information. The overall purpose of philosophy, as understood there, was the divinization of human nature, the ‘assimilation to God’ of human nature as far as possible (Plato, Theaetetus 176ab). This goal could be achieved in that what is highest, most ‘divine’, in human nature is reason and in that the perfection of reason is knowledge, a condition approaching what was thought to be the felicity of the gods. Knowledge as a perfection of the activity of the human rational soul could be called a virtue of the soul. And as there are degrees in the quality of knowledge which is attained, going from practical knowledge dealing with the changing circumstances of worldly existence up to theoretical knowledge of the eternal and necessary principles which create the world, so there are degrees in virtue. In this way the structure of sciences represents a gradation intended to lead the rational soul from lower virtues and levels of knowledge (the practical sciences) to ever higher virtues and knowledge (the theoretical sciences), a gradation which moves from the natural world (physics), through mathematics, to the summit of scientific knowledge, metaphysics, which is both a knowledge of and a sharing in divine existence.Footnote 2

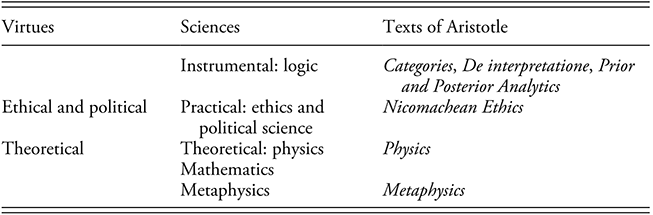

A simplified plan of the curriculum advocated and (to some extent) followed in the schools of Athens and Alexandria in the fifth and sixth centuries might resemble Table 0.1.

Table 0.1 The Neoplatonic curriculum, preliminary cycle: Reading Aristotle

This plan represents a minimal programme and follows the brief indications given by Marinus in his account of his teacher Proclus’ training under Syrianus in Athens.Footnote 3 We can assume that Proclus read other important texts of Aristotle, for example, the De anima, a text which was felt to lead (like mathematics) from physics to metaphysics.Footnote 4 The Alexandrian teachers give us much more extensive and elaborate lists of Aristotle’s works,Footnote 5 but we may doubt that such lists were followed completely in the school. The commentaries on works of Aristotle written in the Athenian and Alexandrian schools (some of which have survived, if only sometimes as fragments) testify to the use of these works in teaching.

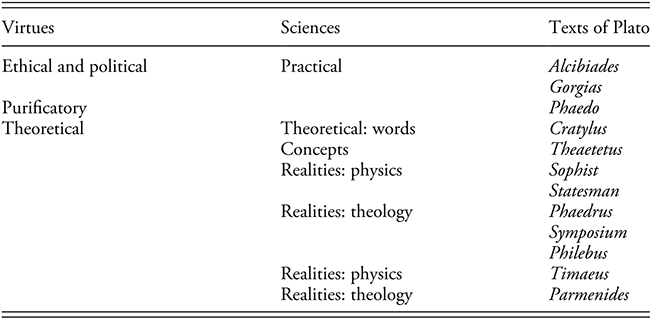

Table 0.2Footnote 6 represents a curriculum of study which is reported as having been introduced by Iamblichus.Footnote 7 It is possible that the first cycle, that of reading Aristotle’s works, also goes back to Iamblichus, since both cycles seems to reflect an overall plan. We know that Iamblichus also commented on and made use of Aristotle’s treatises.Footnote 8 Other authorities, besides Aristotle and Plato, were read in the schools as supplements to the programme, for example, the (Pseudo-Pythagorean) Golden Verses and Epictetus’ Manual, read as providing a preparatory moral education; Nicomachus’ introductory manuals, useful for the study of arithmetic and harmonics; Euclid’s Elements, a text for geometry; and Ptolemy’s Syntaxis (Almagest), for astronomy. The texts of these authorities were also commented on or reworked in the schools.Footnote 9

Table 0.2 The Neoplatonic curriculum, main cycle: Reading Plato

The function of the sciences in leading the rational soul up to a divine existence was expressed by the image of a ladder, or bridge: the sciences provide as it were a ladder or bridge which leads us up to a higher life. The image of a ladder was made popular in particular by the second-century-ad Platonist Nicomachus of Gerasa in his Introduction to Arithmetic: ‘It is clear that these mathematical sciences are like ladders and bridges which transport our reasoning faculty from the objects of perception and opinion to those of intellection and science.’Footnote 10

The image of the ladder becomes quite common in the writings of the Platonists of Late Antiquity, for example, in IamblichusFootnote 11 and in a course of lectures reflecting the teaching given in sixth-century Alexandria, where the Hellenized Latin word σκάλα is used.Footnote 12 One might mention also the robe of the personification of Philosophy which appears in a vision to Boethius in his prison near Padua before his execution in 524, a robe on which was woven (below) the letter Π and (above) the letter Θ, the letters linked by steps like those of a ladder (in scalarum modum gradus), leading from the lower to the higher.Footnote 13 So Philosophy will lead Boethius from practical to theoretical knowledge and thereby bring him back from his confusion and misery towards true happiness. Plato himself had not used the image of the ladder in this way, but he certainly suggests a succession of stages which can lead human reason to higher levels of knowledge both in the great image of the cave in the Republic (514a–519c) and in the ascent through levels of beauty of the Symposium (210a–211c), an ascent by means of ‘steps’ (ἐπαναβασμοί, 211c3). In a phrase inspired by Plato’s image of the cave which was to become popular in the Platonic schools of Late Antiquity, Plotinus noted that mathematical studies could accustom the student of philosophy to immaterial reality.Footnote 14

The division of philosophy into two branches, practical and theoretical, themselves divided into three parts, was not above discussion in the schools. In particular, the distinction between the three practical sciences – ethics, economics and politics – was questioned by some Platonists, according to reports we read in texts from the Alexandrian school. These (unnamed) Platonists argued that a purely quantitative distinction (one person, a household, a community) did not make a difference between sciences, but just a difference in the extent covered by a science, and that another distinction to be found in Plato, between legislative and judicial science, was to be preferred. However, our Alexandrian sources propose a reconciliation and combination of these different positions.Footnote 15 The treatment of logic as an instrument, and not as a part of philosophy, was also a subject of debate.Footnote 16 Here too, a reconciliation of the different positions was attempted. If logic was studied at the beginning of the curriculum, as if in preparation (as an instrument) for the sciences to be acquired after it, it still remained a part of the curriculum, which was not the case for two other disciplines which were also considered to be instrumental, rhetoric and poetics.Footnote 17

The following aspects might be noted as concerns the curriculum of studies sketched here. The fact that a range of sciences served to structure the curriculum meant that each of these sciences tended to acquire a specific place and importance in the teaching of philosophy, as one of the parts of philosophy. This tendency was strengthened by the use made of Aristotle’s treatises in the first cycle of the curriculum, since Aristotle’s treatises suggested that each science has its proper domain of investigation and its proper methods. Integrated in a curriculum which was profoundly Platonic in its inspiration and finality, this meant, on the one hand, that Platonic philosophy would become to some degree Aristotelian in its various parts, and, on the other hand, that the Aristotelian sciences could not be simply taken over: they required adaptation to a new Platonic metaphysical landscape and would need to contribute to the overarching goal of study: assimilation to the divine as interpreted in Platonism. One can claim, as a result of this, that a new importance was given to a range of sciences in the Platonic schools of Late Antiquity and that these sciences were interpreted in ways which were in some respects new. The chapters in this book may serve to substantiate these claims. In the following pages I provide a context for each chapter and summarize the main points.

Part I Rhetoric

In the Greco-Roman world of Late Antiquity, higher education often took the form of study at a school of rhetoric. Such study could prepare for a career in administration and politics, or could be followed by a training in law, medicine or philosophy. Thus Platonist philosophers frequently had received training in rhetoric and sometimes themselves taught in schools of rhetoric and wrote treatises on rhetoric. So wide and deep was the impact of rhetoric on intellectual life in Late Antiquity that its presence can be felt throughout many kinds of literary production, including writings composed by Platonist philosophers.

Although rhetoric did not form part of the curriculum of Platonist schools, it was considered by Platonists as an ‘instrument’ (like logic) of philosophy. For purposes of communication both in the schools, in teaching, and outside, in writings addressed to a wider public, the tools of rhetoric could be turned to good use by philosophers. The first part of this book concerns both the thesis that rhetoric is an instrument which can be put to good use by philosophy and the presence of rhetorical procedures in the way Platonist philosophers composed their texts.

Chapter 1 takes the multiple biography published by Damascius, the last head of the school of Athens before its closure due to Emperor Justinian’s anti-pagan legislation in 529. In this biography, the Life of Isidore, Damascius describes the lives of many of the intellectuals of his time, including various rhetors. Among these rhetors he singles out some who, in his view, were not only virtuous, but also worthy to be called philosophers. Damascius therefore distinguished between good and bad rhetors, a distinction which I relate to the distinction between good and bad rhetoric which we can find it in the work of two Alexandrian philosophers of the fifth and sixth centuries, Hierocles and Olympiodorus: bad rhetoric caters to the base desires of the mob, whereas good rhetoric has a worthy moral purpose and is based on true knowledge. Damascius also notes variety in rhetorical skill, in particular the limitations of his own teacher Isidore in this regard, which compare with his own considerable expertise in the discipline.

Chapters 2 to 5 concern the presence of rhetorical procedures in various works of the Platonists. Chapter 2 discusses fragments surviving from Iamblichus’ correspondence. This correspondence, which includes open letters destined for a wider readership, seems to have been collected for use in the philosophical schools, perhaps by a student of Iamblichus. The collection contains letters which originally, I argue, were of different types. One type is that of an exhortation (a ‘protreptic’) to the study of a science, in this case dialectic. I compare this protreptic with that to be found in Iamblichus’ On General Mathematical Science (De communi mathematica scientia, on which see also Chapter 4); both protreptics correspond to the rhetorical model for the praise of a science. Another type of open letter is that which proposes a ‘Mirror of Princes’ for the edification of people in power and their entourage. A third type to be found in the letters is a monograph which discusses a difficult philosophical question: the relation between fate and freedom. If addressed to a well-educated professional, perhaps a former student of Iamblichus, this letter could have had a wider circulation.

In Chapter 3, the first book of Iamblichus’ multi-volume work On Pythagoreanism, a book entitled On the Pythagorean Life, is placed in the context of Iamblichus’ advocacy of a revival of the ancient roots of Platonism in Pythagoreanism. An analysis of the book suggests that, in it, Iamblichus makes free use of rhetorical models of two kinds of speeches of praise, that of a hero (Pythagoras) and that of a science (Pythagorean philosophy). The work thus serves to invite the reader to a study of Pythagorean philosophy by showing the exceptional nature of Pythagoras’ contribution to human welfare and the value of the sciences which he revealed. In the following books, this protreptic function would be carried on: in the second book, the Protrepticus, an exhortation to study philosophy in general and Pythagorean philosophy in particular; and in the third, the De communi mathematica scientia, a protreptic to mathematics. The following books introduced the four mathematical sciences, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy, and related arithmetic to physics, ethics and theology.

Chapter 4 discusses in more detail the protreptic structure, not only of the De communi mathematica scientia, but also of Proclus’ revision of this text in the First Prologue to his commentary on Euclid’s Elements. I note rhetorical patterns and styles of argumentation used by Iamblichus, which mean, for example, that the same arguments can be made both in support of the study of philosophy (in the Protrepticus) and in support of the study of mathematics (in the De communi mathematica scientia). I note Proclus’ use of Syrianus’ commentary on Aristotle’s Metaphysics in his revision of Iamblichus’ book and suggest that Iamblichus may have been influenced by the prolegomena of Ptolemy’s Syntaxis.

Finally, in Chapter 5, I explore some relations between rhetorical models for speeches in praise of the gods and Platonist texts relating to metaphysics, or ‘theology’, the science of divine first principles. As rhetoric distinguishes different modes and styles in discourse about the gods, so do the Platonists, both in their own works and in those of their ancient authorities (Pythagoras and Plato), distinguish in corresponding ways between different modes of teaching in theology. And as rhetoric prescribes, for speeches about the gods, genealogies of the gods, their actions and benefactions, so too do Platonist theological texts expound the metaphysical genealogy of first principles, a hierarchy of causes and their effects. But speech expresses the limitations of human souls: to approach what is divine and transcendent, which is ineffable, is to be silent, to practice the silence of Pythagoras and of Socrates.

Part II Ethics

After long neglect, ethics and ethical themes in Plotinus and his Platonist successors have become the object of increasing interest and study in recent decades. In Chapters 6 and 7 I propose a survey of ethical subjects in Plotinus and indicate directions of enquiry as regards his Platonist successors. One of these directions is offered by Late Antique Platonist biographies of philosophers. In Chapters 8 and 9 I discuss two such biographies, Iamblichus’ On the Pythagorean Life and Damascius’ Life of Isidore, showing how the figure of Pythagoras expresses in Iamblichus’ account a discipline of life inspired by Epicurean ethics and how the various biographies in Damascius’ text exemplify stages in the scale of virtues. In Chapters 10 to 12 I discuss in more detail two specific themes in Plotinus and his Platonist successors: love and evil. Chapter 13 sketches some elements of a Late Antique Platonist ‘economics’, that is, household ethics, the second branch, coming between ethics and political philosophy, of the practical sciences.

The survey of ethical themes in Plotinus in Chapter 6 begins with Plotinus’ argument that happiness (eudaimonia) is life at its highest degree, the life of intellect of which human soul is capable. The affairs of bodily existence have no part in this life of intellect, which is a perfect, joyful, peaceful state. To reach this state, virtue is required. Plotinus distinguishes between two sorts of virtue: the ‘political’ virtues and the ‘higher’ (or ‘greater’) virtues. These virtues represent stages in assimilation to the divine life of transcendent Intellect. If the affairs of our bodily life are not part of happiness, they do concern us as souls which have a need, a natural ‘appropriation’, to take care of bodily lives, ours and that of others, a generosity which reflects the self-giving of the absolute first principle, the One (or Good).Footnote 18 Action in this bodily existence should be guided by practical wisdom: I discuss Plotinus’ distinction between theoretical and practical wisdom, a wisdom guided by ‘premises’, that is, norms derived from theoretical wisdom. Finally, I indicate the variety of texts composed by Plotinus’ Platonist successors where ethical themes may be found.

In Chapter 7 I discuss the consequences, as regards the theory of virtue, of Plotinus’ denial that ‘spirit’ (thumos) and ‘desire’ (epithumia) are parts of the nature of soul. This denial contrasts with Plato’s tripartition of the soul (which includes spirit and desire) in the Republic, where the tripartition serves to define the four cardinal virtues. However, Plotinus defines these ‘political’ virtues in a different way, as the knowledge and the measure and order brought by rational soul to the affects which arise in the living body. Plotinus introduces furthermore a higher level of virtues, the ‘greater’ virtues. I discuss the relation between these two levels of virtue, in particular as regards the nature of this scale. I argue that in Plotinus the lower (‘political’) virtues are imperfect if possessed without the greater virtues.

Porphyry and Iamblichus added further levels of virtue to Plotinus’ scale of virtues. In Chapter 8 I discuss Iamblichus’ On the Pythagorean Life, which presents Pythagoras as a model of the political virtues.Footnote 19 I show how, on this level, Iamblichus takes over Epicurean ideas about serenity, freedom from disturbance, a balanced control of desires and bodily needs and how, more generally, the Epicurean biographical practice of praising philosophical heroes as models to be imitated anticipates Iamblichus’ presentation of the figure of Pythagoras. I note also a wider use of Epicurean ethical ideas in Late Antique Platonism, in particular on the level of political virtues, the virtues of the discipline of bodily desires.

In his Life of Isidore, Damascius, as I argue in Chapter 9, described the lives of a wide range of figures of his period as exemplifying to varying degrees success or failure in progress through the scale of virtues, thus providing an edificatory panorama of patterns of philosophical perfection, a panorama which could serve to inspire people beginning the study of philosophy. Many of these figures in Damascius’ account were able to achieve lives lived on the level of the political virtues, but few were able to attain higher levels of virtue and very few the highest levels. Yet these exceptional examples could also serve to inspire.

Chapters 10 to 12 concern two themes, love and evil, which could be considered as extending into the domain of metaphysics, so wide is the phenomenon of love, as desire of the Good (or the One), and that of evil, as deriving from matter, the totally indeterminate end to the productivity of the One or Good. In Chapter 10 I explore the range of love in Plotinus, going from human earthly (including sexual) loves up to the One/Good as itself love. Plotinus takes over Plato’s interest in love and makes it into a feature of reality in general. Human love – the desire to unite with the beloved, the feeling of need – anticipates aspects of higher levels of love, soul’s love which brings it to union with transcendent Intellect, Intellect being itself love of the One. I discuss the special sense in which the One can be said to be love and self-love.

Plotinus provided an explanation of evil which was original and philosophically challenging. While deriving everything from one source, the absolute transcendent Good, Plotinus does not trivialize the phenomenon of evil or reduce it to human moral deviation, as do other philosophical and religious approaches, but traces evil back to a metaphysical principle, matter, the source of evil in the world and in human souls. In Chapter 11 I present Plotinus’ account of evil and discuss to what extent it can be defended against a series of criticisms formulated by Plotinus’ successors, in particular by Proclus.

Proclus did not accept Plotinus’ position that matter is absolute evil and responsible for other evils. I return to his position in Chapter 12, as it is followed by Simplicius in explaining the evils of his period, the reign of the Emperor Justinian, a period which was afflicted by a series of natural catastrophes (earthquakes, fires, the plague) and human disasters (military, social, economic). Natural disasters, Simplicius explained, are part of the compensatory balance of forces of the natural world and are not evil, as such; human moral evil can be of benefit to those who suffer it. I contrast this account of evil with that given by a contemporary, Procopius of Caesarea, who explains the same evils of his time in terms of the Justinian’s demonic nature.

‘Economics’, that is, household ethics, was included in the Late Antique ladder of sciences as a branch of practical philosophy. In Chapter 13, a preliminary sketch is proposed of this science, its topics and the authoritative texts to be used in its study. Comparing some chapters of Porphyry’s Life of Plotinus and of Marinus’ Life of Proclus, I show how in these texts Plotinus and Proclus exhibit exemplary practice in household ethics and how Marinus’ portrait of Proclus attempts to show his superiority in comparison with Porphyry’s portrait of Plotinus. I also indicate further texts where more material can be found concerning Late Antique Platonist household ethics.

Part III Political Science

Besides ethics and ‘economics’, practical philosophy includes political science. Olympiodorus provided his students in Alexandria in the sixth century with a handy summary of political science which I discuss and develop in Chapter 14. The following themes are introduced: the domain of political science (the realm of praxis, the life of soul in the material world, in the state or city, where political science directs other subordinate expertises); law (the primacy of law in an ideal city for humans); practical wisdom (its use of theoretical wisdom and difference from it); the goal (‘political’ happiness, involving the political virtues and preparing for a higher life); earthly and heavenly cities; the place of the philosopher in the city; Platonist texts concerning political science. In the following chapters I examine some of these themes in more detail.

Chapters 15 and 16 concern the relation between philosophy and politics and the place of the philosopher in the city. In Chapter 15 I compare the personifications of philosophy which we find in Synesius’ On Kingship and in Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy. I describe the relationship between philosophy and politics, as presented by Synesius, as ‘tense’. Synesius, ambassador for Cyrene at the court of Constantinople at the beginning of the fifth century (and later bishop of Cyrene), asserts the superiority and independence of true philosophy in relation to politics, while asserting the advantages that philosophy can bring to politics. Boethius, a high-ranking Roman official awaiting his execution in 524, is consoled by Philosophy; his mission to bring philosophy and rulership together was not in vain. I mention three factors which can limit the intervention of philosophy in the political sphere.

Chapter 16 takes up this theme in more detail, in an analysis of an important passage in Simplicius’ commentary on Epictetus’ Manual. What functions can the (true) philosopher have in political and social life? Simplicius answers this question as concerning either a state or city which is good or one which is evil. In general, the philosopher should look to the moral wellbeing of others, seeking to ‘humanize’ them (i.e., to promote the virtues, the political virtues, of a good human being). With this in view, in a good state the philosopher will assume leadership functions, as described in Plato’s concept of political science. In a morally corrupt state there will be no place for the philosopher in politics. To preserve his integrity, the philosopher may have to go into exile, as Epictetus did, and Simplicius himself. Or if exile is not possible, the philosopher will try to act in a more limited (probably domestic) sphere, but without compromise.

But why are states evil? In Chapter 17 I approach this question in relation to Plato’s analogy between soul and city, as this analogy was interpreted by Platonists in Late Antiquity. I indicate first that individual souls belong originally, according to the Platonists, to a transcendent, intelligible community, a city of souls where they enjoy an ‘intelligible love’, a ‘divine friendship’. However, souls, in their presence in the material world, can become alienated by this world, alienated from their original community and from each other. I show that a relation is made between Plato’s account of successive stages of degradation in political constitutions in the Republic Books VIII and IX and stages of moral alienation in souls. Corrupt souls produce corrupt states and corrupt states can corrupt souls.

Legislation was considered by the Platonists, following Plato, as the primary part of political science. In Chapters 18 and 19 I discuss legislation and legislators as conceived in Late Antique Platonism. Chapter 18 introduces the theory of natural law to be found in Plotinus and in Proclus in connection with the interpretation of Plato’s Timaeus. Natural law derives from the ‘law of being’ which is divine Intellect and from souls which, in their nature, are laws unto themselves (autonomous). Divine and natural law are considered as paradigmatic for human law. I explore this relationship as it is presented in Proclus and as exemplified in the idea of rulership for women. Appropriate knowledge in metaphysics and physics is required of the legislator in formulating corresponding human law.

In Chapter 19 I show that these ideas can be found in the writings of Julian the Emperor. Julian speaks of a hierarchy of laws, going down from divine paradigmatic laws to the laws of nature and to human laws (both universal and regional). I also describe Julian’s concept of the ideal legislator, how it relates to Iamblichus’ views, and I give an example of Julian’s legislation, that concerning funeral processions, and describe how this legislation is explained by Julian as relating to metaphysical principles.

Tyranny was, in Plato’s descriptions of political constitutions, the most degraded of them all. In Chapter 20 I present the way in which Proclus interpreted the figure of the tyrant in Plato’s dialogues. Tyranny is based on force, violates laws, both cosmic and human, and is motivated by a misled desire for power, power divorced from goodness and knowledge. I argue that Proclus and other Platonists, Damascius and Simplicius, could use this interpretation of Plato to describe the political regimes of their period, in particular the rule of Emperor Justinian, as tyrannies. These tyrannies, in their metaphysical ignorance and moral turpitude, violated divine order and law in destroying pagan temples and statues. I consider finally the cases of two other authors, John Lydus and Procopius of Caesarea, who describe Justinian’s rule in terms of kingship or tyranny.

Part IV Mathematics

Progressing up the ladder of the sciences, from the practical to the theoretical sciences, the student in a Platonist school in Late Antiquity could begin with the study of physics and then move on to mathematics and metaphysics. Mathematics represented an intermediate stage, leading beyond physics and the natural world towards the highest theoretical science, metaphysics. The study of mathematics in the Platonist schools is attested by the commentaries Platonist philosophers composed on the mathematical texts of Nicomachus, Euclid and Ptolemy. A new and inspiring conception of the mathematical sciences (which include arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy) was developed by Iamblichus, by Syrianus and, in its clearest and most fully developed form, in Proclus. In Part I (Chapter 4) I describe the rhetorical dimension to the presentation of this conception in Iamblichus and Proclus; in Part IV, I propose an overview of this conception in its scientific dimension and in its implications for the practical sciences, in particular ethics.

Although fundamental questions in the philosophy of mathematics had been raised and discussed by Plato and Aristotle, only two complete works on the subject survive from Antiquity, Iamblichus’ De communi mathematica scientia and Proclus’ commentary on Euclid’s Elements Book I. In Chapter 21 I list works by Proclus concerning mathematics and the sources he used in these works. Concentrating on Proclus’ commentary on Euclid, I describe his conception of the ontological status of the objects with which mathematics is concerned: these objects are originally concepts innate in human soul, forming part of its very nature, concepts which the mathematician then seeks to articulate, project, construct through various methods so as to constitute an elaborated science. I present also the distinctions made between the mathematical sciences and their methods, the importance of mathematics for other sciences (both superior and inferior to it), and Proclus’ relations with other mathematicians of his time.

In Chapter 22 I examine music in more detail, considered as a theoretical science dealing with the relations (or proportions) between numbers. The ontological status of the objects studied in theoretical music (‘harmonics’) is described and the primary proportions (or intervals), identified as concords, are presented. The importance of music as providing models for subordinate sciences, in particular ethics and physics, is sketched.

The paradigmatic function of music with respect to ethics is explored in more detail in Chapter 23. Four levels of music are distinguished by Proclus, going from audible music, through harmonics (theoretical music) up to the highest, divine music, that of philosophy as assimilated to the divine. Bringing these four levels of music into relation with the scale of virtues, I describe how audible music can have a role in the education of irrational affects on the level of ‘ethical’ virtue. On the level of ‘political’ virtue, harmonics provide knowledge inspiring political virtue and which is of use in producing morally beneficial audible music. I note how Proclus, in dealing with these themes in relation to Plato’s association of virtues with musical consonances, made use of Ptolemy’s Harmonics and how Damascius both provides more information about Proclus’ views and criticizes them. Finally, I refer to the highest levels of music and their relation to the highest levels of virtue, where plurality and differentiation (in music and virtue) are finally absorbed in unity.

The theme of the harmony of the spheres appears already in Plato and is criticized (as a Pythagorean theory) in Aristotle: if there is such a harmony, why is it that we do not hear it? Despite Aristotle’s criticism, various attempts were made in Antiquity to provide an answer to the question. In Chapter 24 I present an answer to be found in Simplicius which, I argue, goes back to Iamblichus: Pythagoras alone can hear the celestial harmony, whereas we in general cannot; this is because Pythagoras has a faculty corresponding to and able to sense this harmony, an astral vehicle of the soul which is pure, as compared to the impure accretions our souls accumulate in our descent to the body and which prevent us from hearing the celestial music. I describe this music, how Pythagoras educated himself in hearing it and how he composed audible music imaging it for the moral education of his followers.

Part V Metaphysics

Metaphysics constituted the summit of the ladder of sciences taught in the Platonist schools of Late Antiquity. A new conception of metaphysics as a science was developed by the Platonists, inspired in particular, on the one hand, by their adoption of Alexander of Aphrodisias’ reading of Aristotle’s Metaphysics as expounding a science corresponding to Aristotle’s conception of demonstrative science, and by their attempt, on the other hand, to reconcile this with their view that the objects of metaphysical science – divine first principles – transcend human scientific reasoning. Chapter 25 provides a general survey of the development of the Platonists’ new conception of metaphysics as a science and the following chapters describe in more detail particular aspects of this science.

In Chapter 25 I introduce Alexander of Aphrodisias’ adoption of a systematic reading of Aristotle’s Metaphysics, a reading which unified Aristotle’s various descriptions of a science in the treatise and saw it as exemplifying the Aristotelian ideal of demonstrative science. I then show how Syrianus took over Alexander’s reading of Aristotle, combining it with Plato’s references to a supreme knowledge, ‘dialectic’, and explaining the possibility of scientific knowledge of the objects of metaphysics – transcendent divine first principles – in terms of concepts innate in the soul which both image these first principles and are available to discursive reasoning as sources of knowledge of these principles. However, the primary text for metaphysics, according to the Platonists, was not Aristotle’s Metaphysics, but Plato’s Parmenides. I show how Proclus’ interpretation of the Parmenides, inspired by Syrianus’ conception of metaphysics, underlies the composition of Proclus’ metaphysical masterpiece, the Elements of Theology. Finally, Damascius, in another metaphysical masterpiece, is shown to have brought out to the fullest extent the limits of human reasonings about transcendent divine principles, reasonings which incessantly lead to contradictions and impasses (aporiai), the aporetical ‘birth-pangs’ of the reasoning soul where it meets what transcend it.

Chapter 26 discusses in more detail the concepts innate in the soul whereby soul can reason about what transcends reasoning. I describe the relations between words, concepts and things (in this case transcendent realities), as the later Platonists saw these relations, and argue that the rational soul does not simply ‘look’ at metaphysical concepts, as it were, but that they are known as part of the dynamic, productive operations of rational thought.

The way in which Proclus’ Elements of Theology exemplifies metaphysical science as understood by Late Antique Platonists and as expressed in Proclus’ commentary on Plato’s Parmenides is examined in Chapter 27, which proposes an analysis of the propositions and demonstrations which open the book. I stress the idea that these metaphysical reasonings were regarded as ‘exercises’ of the rational soul, a training leading to a greater proximity to divine first principles.

Alexander of Aphrodisias included Aristotle’s first principles of rational thinking, in particular the principle of non-contradiction, in the domain of metaphysics, as would Syrianus. In Chapter 28 I discuss this principle as it was understood by Syrianus, in particular with regard to its roots in divine Intellect, where the unity of intellection and its objects grounds the principles of reasoning in human intellection and the truth of its objects.

Finally, lest the apparent scientific rigour of the arguments of a text such as Proclus’ Elements of Theology might mislead one to think that a definitive science of divine first principles is achieved, Damascius’ Difficulties and Solutions concerning First Principles provides an effective antidote to such an illusion. In Chapter 29 I describe how Damascius exploits the contradictory arguments and conclusions that rational soul can develop in its reasonings with concepts about the divine. I argue that these dilemmas, these impasses suffered by the rational soul, are not, as Damascius sees things, expressions of the ultimate failure of metaphysics, nor the stalemate of a sceptic which requires suspension of judgement, but a privileged place where the soul exercises its rational powers in an approach to the divine.