1 Taxation and State‒Society Relations in China ‒ Why Didn’t the Dog Bark?

Budget is the skeleton of the state stripped of all misleading ideologies.

Fiscal capacity is widely regarded as a pillar of the state. Raising fiscal revenue, however, has been and continues to be a highly contentious state‒society issue, both historically and contemporarily. After all, the psychology of loss aversion implies that both rich and poor detest relinquishing part of their income to the state as tax payments unless they are necessary, for example, to secure public goods or expand political rights. Failure to resolve implicit or explicit fiscal bargaining erodes state‒society relations, inciting mass resentment, social unrest, and eventual tax revolt typically spelling the end of a regime. Fiscal extraction is ubiquitous across states, and authoritarian regimes are no exception because fiscal revenue bolsters their infrastructural power.Footnote 1

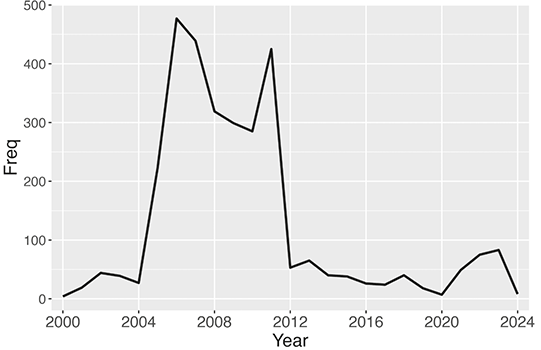

Given the centrality of taxation in state‒society relations, China remains a puzzling case. By various metrics, the Chinese government has a strong fiscal capacity compared to many countries. Historically, the state’s fiscal revenue rarely exceeded 5% of the GDP since the fourteenth century.Footnote 2 By 2019, however, the total government revenue amounted to 27.27% of the GDP.Footnote 3 Compared to many states ‒ even China before the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949 ‒ the state’s strong fiscal capacity has encountered relatively little resistance because the government seldom resorts to blunt coercion for most tax collection. Taxation is rarely the primary cause of social unrest in contemporary China.Footnote 4 Even when taxation was a key source of conflict sparking rural unrest in the 1990s, agricultural taxes amounted to less than 6% of the total government fiscal revenue.

Paradoxically, the Chinese government has undertaken several tax cut reforms despite local governments face mounting fiscal pressure and looming government debt.Footnote 5 Take personal income tax (PIT) as an example: Since the 1980s, both the share of PIT in government revenue and the pool of taxpayers have steadily increased, driven by China’s booming economy. This is an ideal scenario in which the government retains greater revenue from PIT without having to raise the tax rate; nonetheless, the Chinese Government has repeatedly raised the exemption threshold for PIT since 2006, along with some adjustments of marginal tax rates. Effectively, these reforms shrank the tax base for PIT and reduced its contribution to total government tax revenue. In addition, the share of taxes on goods and services declined from close to 60% of total tax revenue in 1999 to barely 40% by 2021.

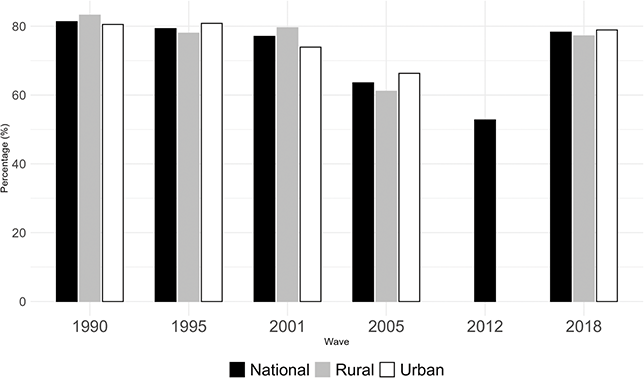

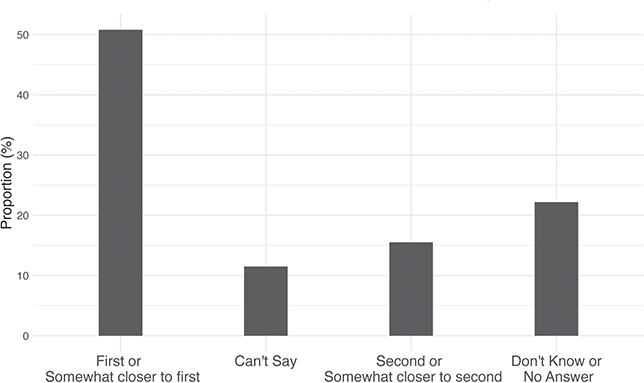

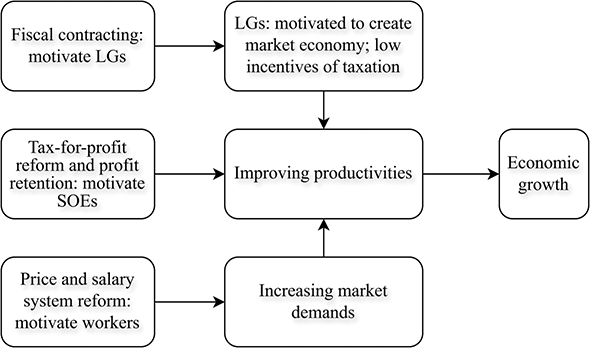

The apparent low political salience of taxation among ordinary citizens and businesses, coupled with the Chinese government’s repeated tax cut initiatives, defies conventional wisdom. The spatial models of electoral competition posit that tax policies are driven by the “median voter” and redistributive preferences (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Meltzer and Richard Reference Meltzer and Richard1981; Steinmo Reference Steinmo1993). In China, by contrast, policymaking is driven by elite politics and central‒local government bargaining, not by the aggregation of mass preference through elections. Although policymaking in autocracies could respond to the need to appease the public, the low salience of tax grievance implies that the government did not initiate these tax cuts to mitigate social unrest in China – except perhaps in the case of the abolition of agricultural taxes in 2006.

Meanwhile, special interest groups, particularly business elites, are crucial players who exert enormous influence on tax policymaking in both democracies and nondemocracies (Dixit, Grossman, and Helpman Reference Avinash, Grossman and Helpman1997; Fairfield Reference Fairfield2015; Martin Reference Martin1991; Winters Reference Winters2011). The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has meticulously undermined the ability of any organization to overcome the collective action problem in the political sphere. Hence, these tax reforms rarely resulted from any intense lobbying and pressures from economic elites. Finally, major tax reforms are often sparked by exogenous shocks like the global financial crisis and international tax competition (Basinger and Hallerberg Reference Basinger and Hallerberg2004; Hays Reference Hays2011; Swank Reference Swank1998; Wallerstein and Przeworski Reference Wallerstein and Przeworski1995). These Chinese tax reforms, except for the 2008 value-added tax (VAT) reform, met with no external pressures.

To shed light on this perplexing development of taxation and state‒society relations in China, we investigate three crucial questions in this Element. First, what objectives does the Chinese government seek to accomplish through its tax policies? Second, why hasn’t taxation emerged as a prominent issue motivating Chinese citizens and businesses to politically engage with the government? Last, what are the unintended consequences stemming from the Chinese government’s strategy in taxation?

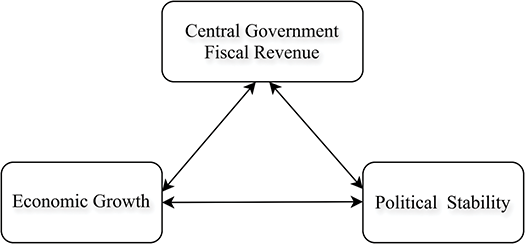

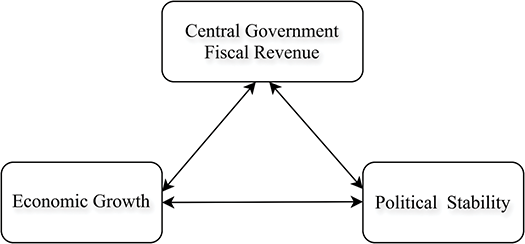

We delve into the logic of taxation from the perspective of the Chinese government, contending that tax policies have been an important instrument for the Chinese central government to serve three policy goals: Raising fiscal revenues, stimulating economic development, and maintaining political stability. These objectives, however, engender a trilemma, forcing the Chinese central government to balance tradeoffs by prioritizing one goal over the others. Crucially, the central government’s policy implementation relies on local governments, which frequently exercise their discretionary power to selectively fulfill competing mandates from higher-level authorities. In response, the central government initiates tax reforms to address the challenges resulting from the trilemma, inadvertently creating further unintended consequences, and thus requiring subsequent adjustments.

Second, we contend that the low saliency of taxation in Chinese society is by design. During the Maoist era, the socialist economic model rendered direct taxation unnecessary because the state controlled nearly all aspects of economic production and distribution. When China transitioned to a market-oriented economy after 1978, the state prioritized taxes on goods and services, targeting firms, not individuals, as the primary tax base. Consequently, business taxes account for more than 90% of total government tax revenues to date. Despite shouldering most of the tax burden, Chinese businesses have not actively engaged in politics to push for policy changes. Instead, they adopt atomized strategies to reduce their tax burdens through legal or illegal means and seek preferential policy treatments via political connections. Furthermore, the reliance of indirect taxation on China’s tax structure implies that Chinese businesses could shift a large portion of their nominal tax burden to downstream businesses and consumers, mitigating their perceived tax burden.

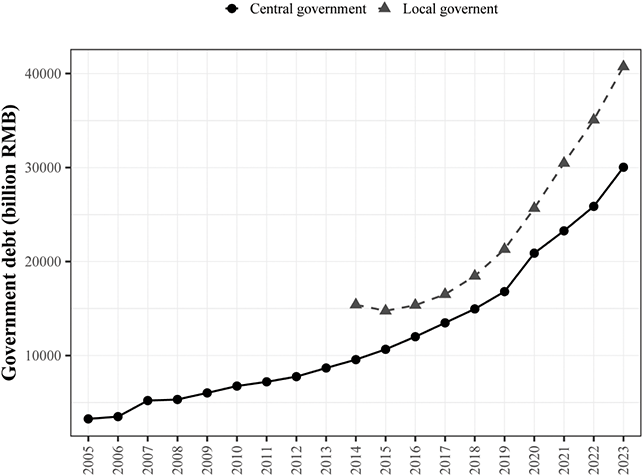

Third, we contend that the Chinese government’s efforts to diminish the saliency of taxation in state‒society relations inadvertently generate new sources of tension. Specifically, advocating for lightening the tax burden on citizens amplifies their sensitivity to potential tax increases in the future, largely because of citizens’ unrealistic expectations resulting from the state’s continuous promise of low taxes. This dynamic constrains the state’s ability to extract taxes from alternative sources, perpetuating a cycle of continual tax reductions. Meanwhile, local governments face immense pressure to raise fiscal revenue while promoting economic growth and financing local public goods. This has led to escalating government debt and heavy reliance on nontax revenue from land resources, and even leniency in enforcing regulations on firms in exchange for tax income. Consequently, new sources of grievance have emerged, further heightening citizens’ sensitivity to any tax hikes.

This Element contributes to recent scholarship revisiting the political origins and consequences of fiscal policy and taxation in China.Footnote 6 In this strand of literature, they have primarily provided an institutional perspective, highlighting how China’s political system and administrative framework shape the development of tax policies and fiscal capacity. For instance, Zhang (Reference Zhang2021) contends that the CCP faces two dilemmas concerning taxation ‒ growth and representation ‒ and proposes the pursuit of three sets of strategies to resolve them: Half-tax state,Footnote 7 de facto fiscal federalism, and underinstitutionalized tax administration. Focusing on the operation of taxation bureaucracy, Cui (Reference Cui2022) offers a detailed study of the tax administration responsible for tax collection in China. He coins the term “revenue mobilization,” arguing that China’s expansive tax capacity rests on the revenue management system through non-rule-based tax collection. This observation echoes both qualitative and quantitative studies of fiscal extraction and taxation by subnational governments in China (Lü and Landry Reference Lü and Landry2014; Tian and Zhao Reference Tian and Zhao2008; Wu Reference Wu2007). Lan (Reference Lan2021) places China’s fiscal policies in the broader macroeconomic context, studying the ways through which fiscal policies shape local governments’ behavior in promoting economic growth, attracting FDI, and expanding urbanization. His argument is built on earlier scholarship indicating that the Chinese government uses fiscal incentives to motivate local governments to pursue industrial growth (Oi Reference Oi1992). Finally, Lin (Reference Lin2022) provides a comprehensive overview to China’s public finance system.

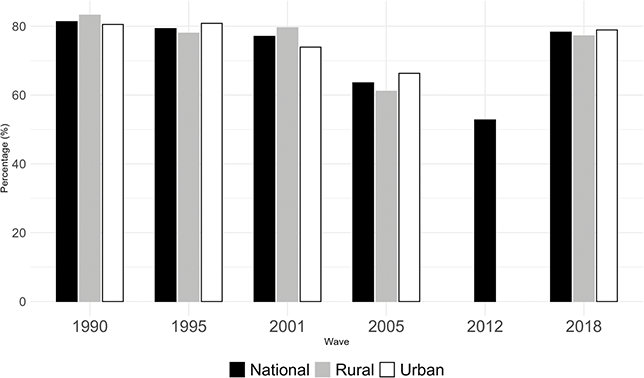

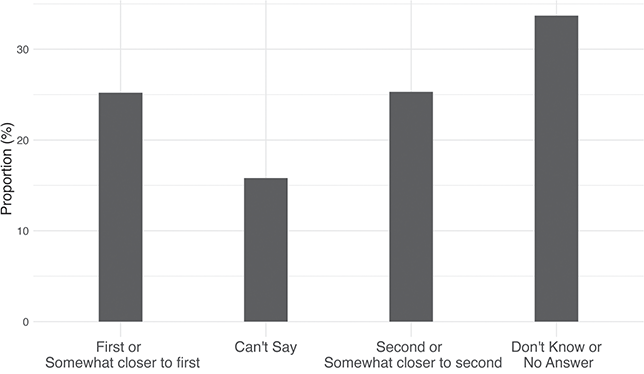

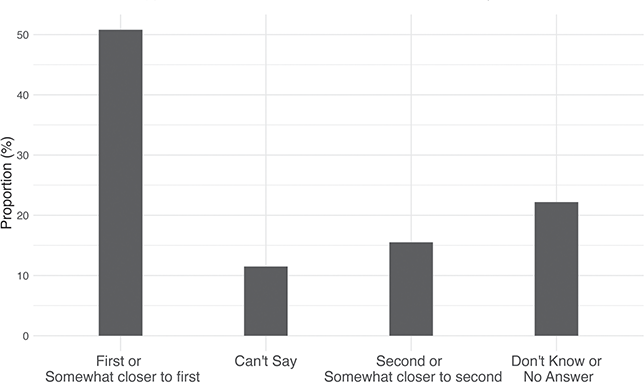

Building on this strand of scholarship, we contend that the evolution of tax reforms since the 1980s reflects a trilemma confronting the central government, which navigated through strategic engagement with local governments. Importantly, we extend the existing institutional perspective by focusing on the political behaviors of citizens and businesses in their responses to state tax policies. By leveraging a diverse array of data ‒ from public opinion surveys to instances of social unrest in China ‒ we uncover several new findings. We reveal that urbanites, despite having high tax morale, are highly sensitive to direct taxation and favor redistributive tax policies. In addition, we challenge the presumed link between taxation and social unrest in rural China by highlighting the disparity between trends in social unrest and the peasant tax burden. We suggest that taxation alone may not have been the primary catalyst for rural unrest in the 1990s. Instead, it has been used as leverage by rural residents to vent grievances stemming from issues concerning rural governance. Finally, we observe that businesses in China typically adopt atomized strategies to mitigate their tax burden rather than engaging in collective action to drive broader policy changes. These new insights generate important implications for future studies of taxation and the state‒society relationship in China.

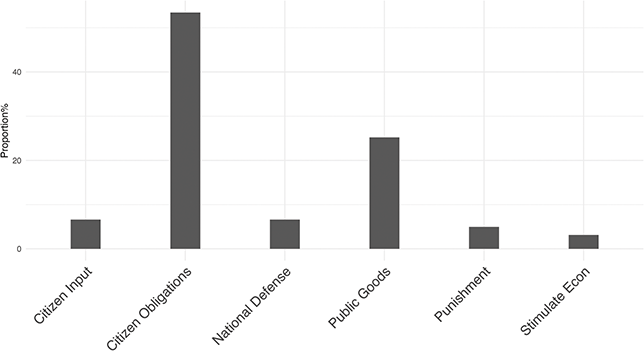

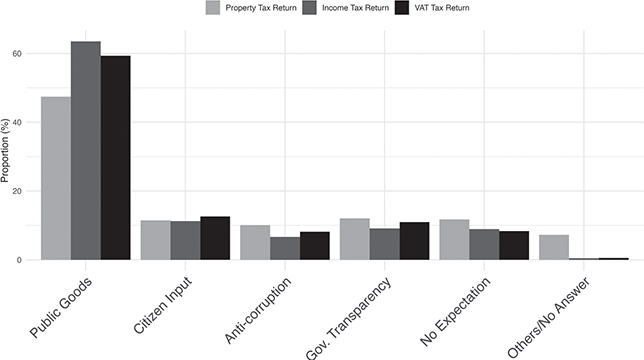

The remainder of this Element is divided into five sections. In Section 2, we offer an overview of China’s fiscal system and tax structure, placing it in the global context. Section 3 is a deep dive into the political logic underpinning the evolution of taxation policies in China, emphasizing the distinct objectives and strategies pursued by the central and local governments. We explore both the intention and consequences of several major tax reforms since the 1980s. In Section 4, we shift the focus to the political behaviors of citizens and businesses. Drawing on existing survey data and scholarship, we demonstrate that Chinese citizens exhibit high tax morale and strong expectations for public services in return for taxation. Businesses, by contrast, have sought to secure individual benefits in exchange for taxes. Furthermore, Section 5 highlights several unintended consequences of China’s tax policies, focusing on issues like citizens’ sensitivity to direct taxation, serious local government debt, heavy reliance on land-based nontax revenue, and the government’s leniency in enforcing regulations. In Section 6, we conclude by outlining several promising avenues for further research into the role of taxation in shaping state‒society relations in China from a comparative perspective.

2 Lay of the Land: Mapping China’s Taxation System and Fiscal Capacity

To contextualize China’s contemporary taxation system, we first compare its revenue structure and composition to those of democratic and authoritarian states, then briefly overview its evolution since the reform era. We are primarily interested in a focus on taxation capacity, or the state’s capacity to collect various forms of taxes, not the broader notion of fiscal capacity, or the state’s ability to extract revenue from both tax and nontax sources.Footnote 8 The distinction reflects state‒society relationships through fiscal extraction ‒ from whom and how the state extracts fiscal revenue. For instance, Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter and Swedberg1991 [1918]) proposed a typology of the state based on the structure of its fiscal revenue: A feudal state is one where rulers fund with their own land, dues paid by their serfs and customs, not by tax. By contrast, a tax state primarily relies on the collection of taxes codified through laws and regulations. Lieberman (Reference Lieberman2003) expands the categories, identifying five types of fiscal states: Skeletal, rentier, communist, adversarial tax state, and cooperative tax states (54‒60). In the rentier state and the communist state, a state may have high fiscal capacity but low taxation capacity.

The hallmark of a modern fiscal state is reliance on taxation as its primary source of revenue, offering legitimacy and transparency to the state’s fiscal extraction. Since the reform era of the 1980s, the Chinese government has pursued rapid economic growth while strengthening its fiscal capacity. Alongside this process, China’s fiscal regime evolved from a communist state to a tax state, mirroring its broader transition from a planned economy to a socialist market economy. In particular, the Chinese government has undertaken a series of fiscal reforms to strengthen its taxation institutions since the early 1990s, aligning with a broader transition to a market economy.Footnote 9 Slowly, China’s tax-to-GDP ratio steadily rebounded from less than 10% in 1994 to over 20% by 2020. We conclude by examining a key characteristic of its tax state ‒ reliance on indirect taxation ‒ and place it in the larger context of nontax revenues and contributions from state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

2.1 Tax Capacities and Structures of Autocracies and Democracies

According to Huntington (Reference Huntington1968) the effectiveness of government is a more critical concern for developing countries than its form, but the reverse also holds true: The forms of government can significantly influence the capacity and effectiveness of governance, particularly in tax capacity. To this end, researchers attempt to identify the causal effect of regime type on taxation capacity, yet empirical findings remain inclusive.

From one perspective, democracies may tax less than autocracies because institutional arrangements like elections and legislatures generate veto points constraining ruling governments’ ability to extract revenue from society at will (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002). Furthermore, democratic governments generally rely less on coercion, leading to lower tax rates than authoritarian governments with the means and incentives to impose onerous tax burdens on citizens (Przeworski Reference Przeworski1990).

Another perspective suggests the opposite: Democracies are associated with higher taxation.Footnote 10 Facing the pressure of median voters, democracies may tax more for redistribution, especially in countries rife with inequality (Meltzer and Richard Reference Meltzer and Richard1981). Democracies could also tax more because of heavier investment in building taxation capacity (Besley, Ilzetzki, and Persson Reference Besley, Ethan and Torsten2013). Finally, an effective taxation system relies on quasivoluntary tax compliance, or compliance motivated by a willingness to cooperate but backed by coercion (Levi Reference 86Levi2006: 7). Because of representative institutions and government transparency, democracies have a stronger capacity to achieve citizens’ quasivoluntary compliance, embodying higher taxation capacity than authoritarian regimes.

Empirical investigations, however, demonstrate a mixed relationship between regime type and taxation capacity. Whereas Garcia and von Haldenwang (Reference Garcia and Haldenwang2016) identify a nonlinear relationship between tax ratios and democracy scores, Cheibub (Reference Cheibub1998), Herb (Reference Herb2005), and Mulligan, Gil, and Sala-i Martin (Reference Mulligan, Gil and Sala-i-Martin2004) find no difference in the taxation capacity of democracies and autocracies. Using longer time-series data, Haber and Menaldo (Reference Haber and Menaldo2011) find no significant relationship between tax reliance and regime type.

The mixed evidence on the relationship between regime type and fiscal capacity may derive from several critical factors shaping taxation capacity. Besley and Persson (Reference Besley and Persson2011) suggest investment in fiscal capacity as a forward-looking decision by ruling elites, influenced by the costs of investment and uncertainty surrounding future benefits. Key determinants of these cost‒benefit analyses include the state of the regime (i.e., common-interest states, redistributive states, and weak states), degree of political stability, resource (aid) independence, and level of economic development. Rather than adhering to a simplistic dichotomy of regime types, their framework underscores the interplay of political, economic, and cultural factors shaping a country’s fiscal capacity. Importantly, they emphasize the complementariness in development clusters of these factors. Shown later, this approach offers valuable insights into China’s fiscal capacity development, yet puzzling patterns remain.

Turning to case studies, Bräutigam, Fjeldstad, and Moore (Reference Bräutigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008) and Moore, Prichard, and Fjeldstad (Reference Moore, Prichard and Fjeldstad2018) highlight a complex web of tax capacity determinants. Building on recent elite-centric accounts of taxation capacity, the former underscore the development of a state’s taxation capacity, primarily shaped by the incentives and capabilities of ruling elites in state-capacity building.Footnote 11 Furthermore, a state’s commitment to economic development and distinctive economic model also yields significant implications for the evolution of its taxation capacity. Demonstrated in Section 2.2.1, China’s SOEs and land-based revenue play a unique role in strengthening the government’s taxation capacity within a competitive market system ‒ an exceptional case among autocracies that typically rely on indirect taxation and natural resource revenues to sustain fiscal capacity (Morrison Reference Morrison2015; Ross Reference Ross2012).

Finally, Stasavage (Reference Stasavage2016) contends that the rise of representation and expansion of fiscal capacity in premodern Europe is conditional on a unique historical context. On one hand, representation improves the quality of public expenditure, thus contributing to economic growth. On the other hand, representative institutions improve taxation capacity by improving tax compliance without producing political instability. Most developing countries today, however, encounter limited interstate warfare and easy access to nontax revenue sources. Consequently, rulers have weaker incentives to invest in costly taxation capacity (Centeno Reference Centeno2002; Herbst Reference Herbst2000; Moore Reference Moore, Bräutigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008; Queralt Reference Queralt2022). Considering the potential political demand stemming from expanding taxation capacity, Martin (Reference Martin2023) argues that rent-seeking leaders in low-capacity states strategically underinvest in fiscal capacity to reduce citizens’ call for political representation and accountability. Similarly, Slater, Smith, and Nair (Reference Slater, Smith and Nair2014) note that many newly established democracies struggle with building the infrastructural capacity needed for effective resource extraction, particularly in taxing the wealthy, largely because these governments tend to limit political contestation.

2.1.1 China’s Taxation Capacity in a Comparative Perspective

With the caveat that the relationship between regime type and taxation is mixed in existing studies, we compare China’s taxation in the global context. First, we place a commonly used measure of taxation capacity – ratio of tax revenue to GDP ‒ against the level of economic development of the country. Taxation data derive from the International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD);Footnote 12 the measure of GDP, from Fariss et al. (Reference Fariss, Anders, Markowitz and Barnum2022). We drew the measure of regime type from the political regime indicator on the Varieties of Democracy (V-dem).Footnote 13

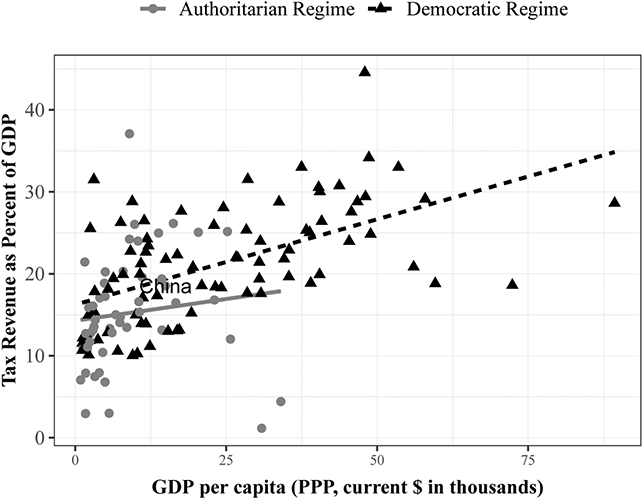

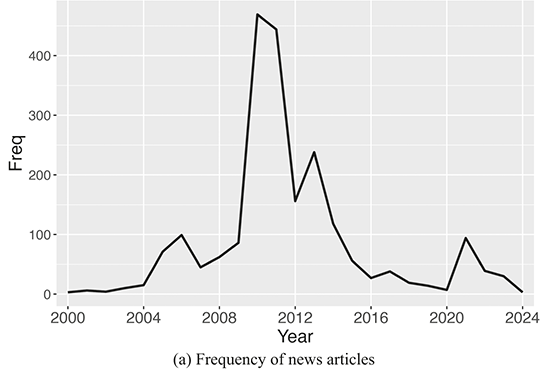

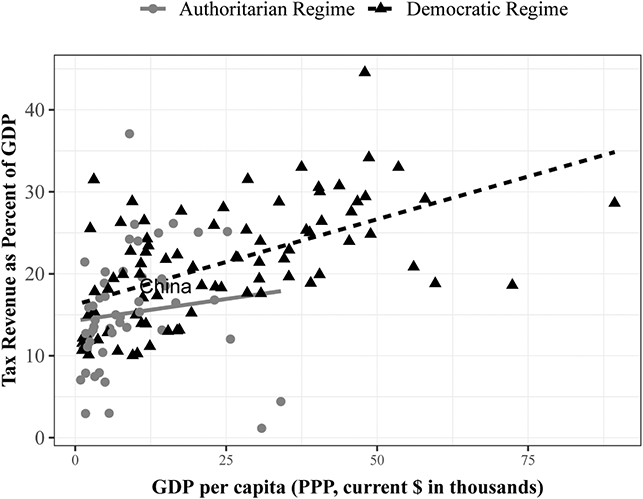

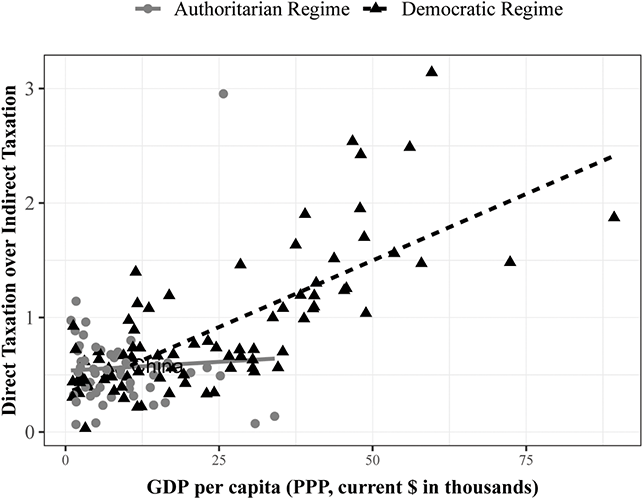

We first plot the ratio of tax revenue to GDP against GDP per capita (PPP, purchasing power parity) for all countries in 2018, marking them by regime type and adding a linear fitted value for each type. Figure 1 reveals three patterns. First, the ratio of tax revenue to GDP positively correlates with GDP per capita income as predicted by Wagner’s law (Besley and Persson Reference Besley and Persson2011; Easterly and Rebelo Reference Easterly and Rebelo1993). Second, democratic regimes tend to have higher taxation capacity compared to autocracies as the level of economic development increases. Democratic regimes average 21.26% in terms of the ratio of tax revenue to GDP, with a median of 21.03%; authoritarian regimes average 15.21%, with a median of 14.55%. China’s taxation capacity aligns with a typical authoritarian regime at 18.52%, sitting above the fitted value for authoritarian regimes but below the fitted value for democracies. Third, we observe significant variations within and across regime types, consistent with mixed findings in existing studies and the framework built by Besley and Persson (Reference Besley and Persson2011), emphasizing the complementarities of development clusters.

Figure 1 Ratio of tax revenue to GDP among autocracies and democracies (2018).

Note: The tax revenue data are from ICDT. The data of GDP per capita are from Fariss, Anders, Markowitz & Barnum (Reference Fariss, Anders, Markowitz and Barnum2022). Finally, we rely on V-dem for the definition of regime type.

Figure 1Long description

The graph examines the ratio of tax revenue to GDP, where GDP per capita in thousands of current PPP dollars is on the x-axis, ranging from 0 to 100 in increments of 25, and tax revenues as percent of GDP, ranging from 0 to 50 in increments of 10, on the y-axis. China is labeled around $15,000 in GDP per capita and about 18.52% in tax revenue as percent of GDP, roughly in the middle of the authoritarian cluster. Its tax-to-GDP ratio is close to the authoritarian average, but slightly above the trend line, meaning it collects a bit more tax revenue than the typical authoritarian country at its income level. Compared to democracies with similar income levels (around $15k GDP per capita), China’s tax revenue is somewhat lower. Democracies at this income level usually raise above 20 to 25% of GDP in taxes, while China is just below that.

2.1.2 China’s Taxation Structure in a Comparative Perspective

The structure of direct and indirect taxation is another revealing indicator for the state of taxation capacity. Direct taxation refers to taxes imposed on individuals and firms based on their income and assets, including personal and business income taxes, property taxes, and inheritance tax. Indirect taxation is levied on goods and services, including VAT, sales taxes, and customs on imports and exports. Of the two, direct taxation poses a greater challenge for any state because it demands a robust bureaucratic capacity for accurate assessment and effective compliance (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2011; Prasad 2018); moreover, it is far more salient than indirect taxation because of its visibility, thus engendering greater political resistance (Finkelstein Reference Finkelstein2009; Martin Reference Martin2023; Prasad Reference Prasad2012). Given the challenges and complexity of the collection, direct taxation has been commonly considered a benchmark for measuring a state’s taxation capacity.

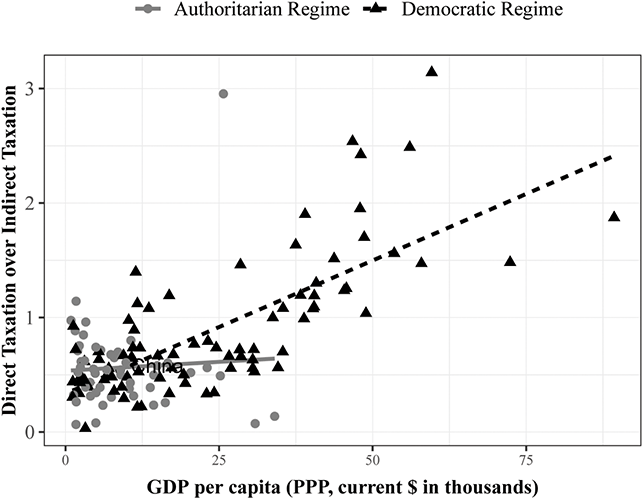

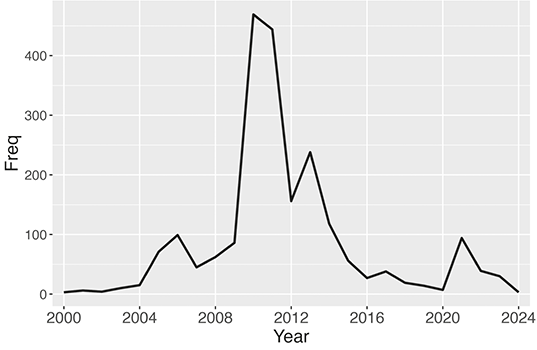

We construct an indicator to measure a state’s tax structure: The ratio of direct tax revenue to indirect tax revenue. We plot this indicator against GDP per capita and mark the regime type. Figure 2 reveals two notable divergences between democratic and authoritarian regimes. First, the average ratio of direct tax revenue to indirect tax revenue for democratic regimes is 0.90 (median, 0.70), which is higher than authoritarian regimes (average, 0.56 and median, 0.52). Put differently, while direct and indirect taxes contribute roughly equally to government revenue in democratic regimes, direct tax revenues in authoritarian regimes amount to only 56% of those from indirect taxation. China’s tax structure remains in the mix of autocracies (0.58). Second, democracies’ tax structures increasingly rely on direct taxation as their economic development advances.Footnote 14 By contrast, little correlation exists between tax structure and the level of economic development in autocracies.

Figure 2 The ratio of direct to indirect taxation among autocracies and democracies (2018)

Note: The tax revenue data are from ICDT. The data of GDP per capita are from Fariss, Anders, Markowitz & Barnum (Reference Fariss, Anders, Markowitz and Barnum2022). Finally, we rely on V-dem for the definition of regime type.

Figure 2Long description

The graph examines the relationship between ratio of direct to indirect taxation and GDP per capita across authoritarian and democratic regimes in 2018, with GDP per capita in thousands of current PPP dollars on the x-axis, ranging from 0 to 75 in increments of 25, and the ratio of direct taxation over indirect taxation, ranging from 0 to 3 in increments of 1 on the y-axis. Democratic regimes consistently exhibit a positive correlation between GDP per capita and direct-to-indirect tax ratio. We do not find any correlation between these two variables in authoritarian regimes. China occupies an intermediate position within this framework. With a GDP per capita of 14,950, its direct-to-indirect tax ratio falls to 0.58, placing it in the middle of the authoritarian cluster. This aligns with the authoritarian characteristic of relying disproportionately on indirect taxation (e.g., VAT, consumption tax). Notably, China’s ratio is slightly higher than the average for authoritarian regimes at its income level, reflecting stronger fiscal capacity than many autocracies, but remains far below the democratic average, highlighting the gap in direct tax reliance between China and its democratic peers.

Figures 1 and 2 suggest that democracies and autocracies may pursue different strategies for building taxation capacity. Specifically, the taxation capacity of democratic regimes is positively associated with reliance on direct taxation. By contrast, autocratic regimes demonstrate no clear preference for either direct or indirect taxation; if anything, they may deliberately limit the expansion of direct taxation to minimize potential conflicts in state‒society relations.

2.2 The Evolution of China’s Fiscal Capacity since the Reform Era

Section 2.1 reveals that China’s taxation capacity aligns with global norms given its level of economic development, marked by a significant reliance on indirect taxation. But how has China’s tax system evolved since the 1980s? Furthermore, what is the relative contribution of tax vis-à-vis nontax revenue to China’s fiscal capacity? In Section 2.2, we review the evolution of tax capacity and structure within the broader context of China’s fiscal capacity.

2.2.1 Structure and Sources of Fiscal Revenue

We first examine the shifting primary sources of fiscal revenue since the 1980s. Zhang (Reference Zhang2021) calls China’s fiscal state a “half-tax state,” relying on indirect taxes (comprising two-thirds of tax revenue) and nontax revenue as the primary sources of government income. Furthermore, SOEs still play a vital role in contributing to both tax and nontax revenue despite China’s transition from a planned to market economy.

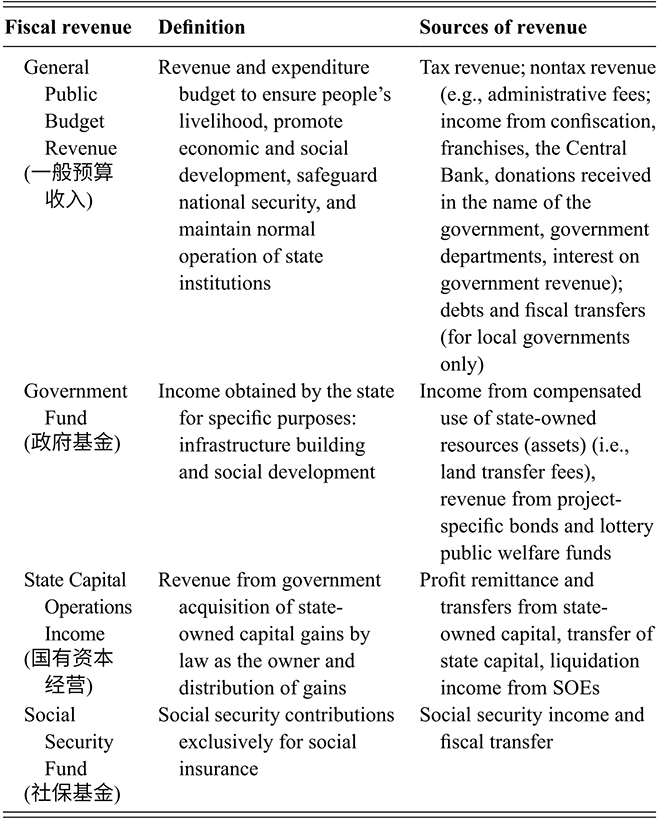

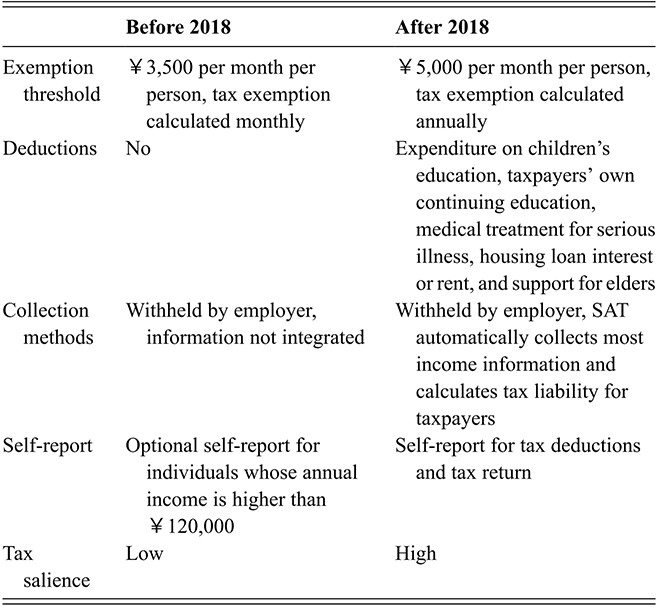

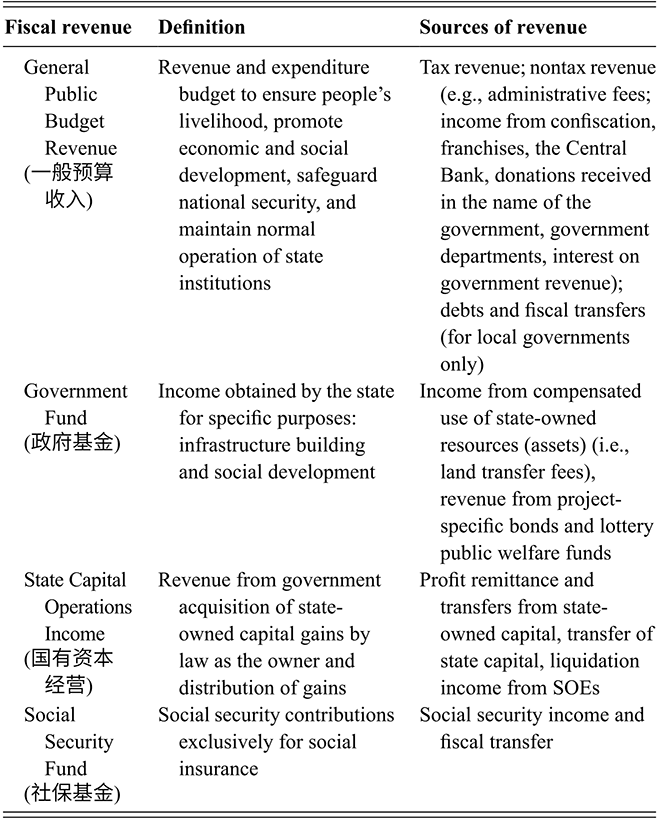

The complexity of fiscal revenue definitions employed by the Chinese government reflects its evolving fiscal capacity since the reform era (Table 1). For instance, General Public Budget Revenue encompasses most funds allocated for public expenditure. Notably, the Chinese central government has sought to curtail local governments’ extrabudgetary incomes (预算外收入) since the 2000s by integrating them into General Public Budget Revenue to enhance oversight. In addition, the central government designated the Government Fund to provide regulation and oversee government-led infrastructure investment and social development initiatives. The reform of China’s social security system established the Social Security Fund. Last, the government designated an account ‒ State Capital Operations Income ‒ to manage revenue from SOE remittance.

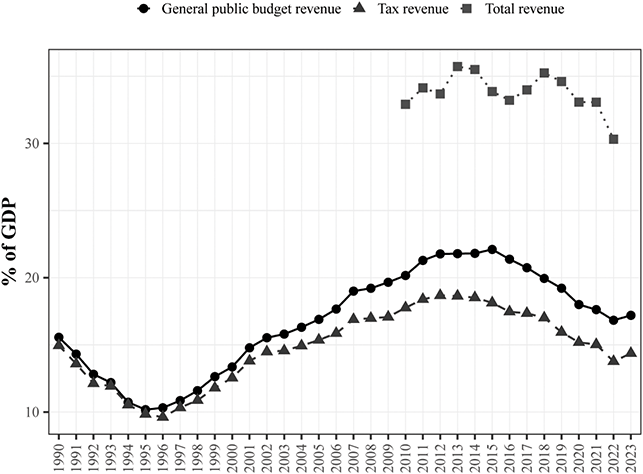

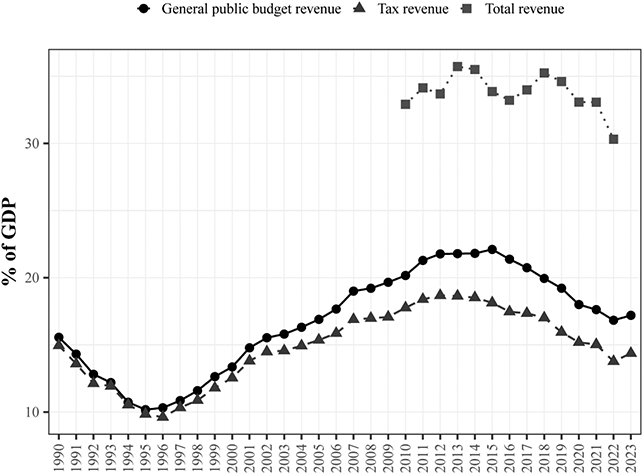

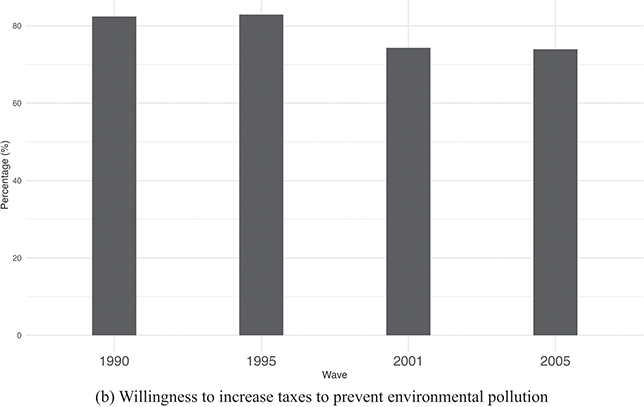

Based on these definitions, we illustrate the changes in China’s fiscal capacity from 1990 to 2023 in Figure 3. First, the share of tax revenue as a percent of GDP rose from less than 10% in 1995 to as high as 17% around 2013, retreating to 15% in 2023. Turning to General Public Budget Revenue, including some nontax revenues, we find a slightly higher level of fiscal capacity. Its share of GDP hovered around 10% in 1995, surged to over 22% by 2015, retreating to just over 17% in 2023. If we adopt a broader definition of government revenue (Total Revenue), which includes all four types of revenue noted in Table 1, it reached as high as 35%, declining to only 30% in recent years.

Figure 3 Fiscal capacity through various definitions (1990–2023).

Note: Data derived from the China Statistical Yearbook.

Figure 3Long description

The graph tracks the evolution of China’s fiscal capacity from 1990 to 2023, measured by three key indicators as a percentage of GDP: General Public Budget Revenue, Tax Revenue, and Total Revenue. Tax Revenue and General Public Budget Revenue follow a closely correlated trend, with the latter remaining consistently higher than the former throughout the period. Between 1990 and 1995, both indicators experienced a continuous decline as a percentage of GDP, reaching a low point of approximately 10% in 1995. Post-1996, both metrics began a sustained and parallel increase, eventually peaking and plateauing between 2012 and 2015. From 2016 onward, both indicators reversed course, entering a period of decline. By 2022, Tax Revenue fell below 15% of GDP and General Public Budget Revenue declined to approximately 17%. Additionally, the figure presents Total Revenue as a percentage of GDP for the period 2009–2022. This metric generally fluctuated between 32% and 35%, exceeding 35% in 2013, 2014, and 2018, before dropping to just over 30% by 2022.

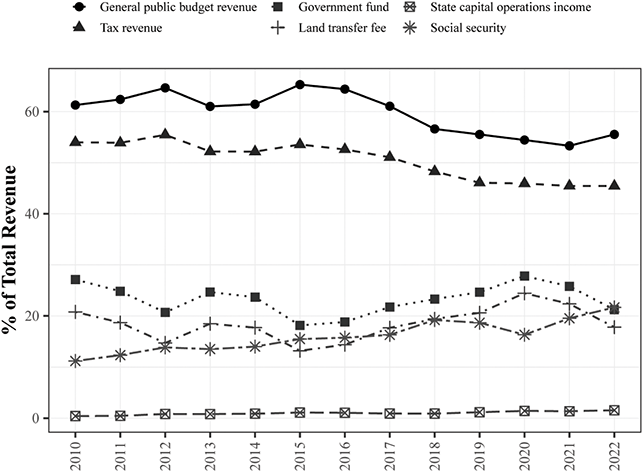

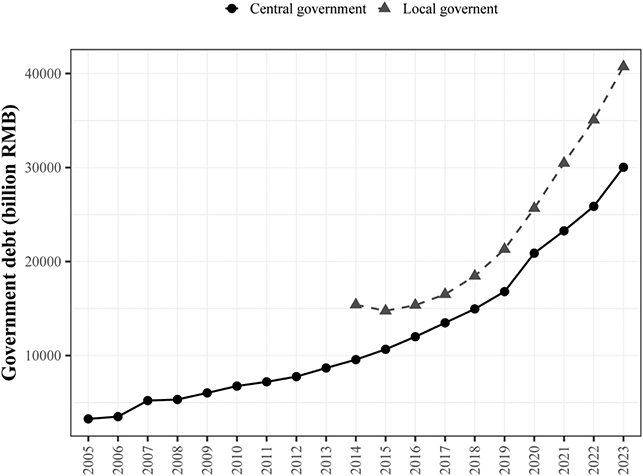

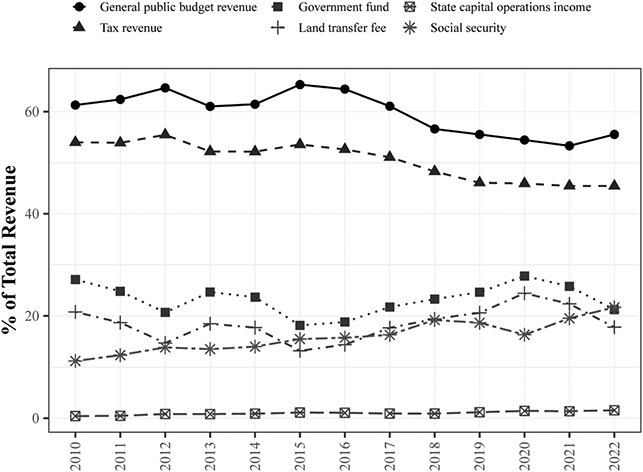

To further unpack the contribution from nontax revenues, Figure 4 illustrates the share of government revenue from various sources. Specifically, the share of General Public Budget Revenue has amounted to over 60% of the total government revenue since 2010, beginning a decline to 53% in 2021. Meanwhile, the share of the Government Fund and the Social Security Fund rose to 26% and 20% of total government revenue in 2021, respectively. If land transfer fees are separated from the Government Fund, Figure 4 shows that they became a significant source of revenue for Chinese local governments from early 2000s to 2020, and only recent economic woes resulted in the sharp decline that contributed to the growing revenue challenges faced by local governments. Together, these measures of fiscal capacity indicate that although tax revenue constitutes the major fiscal income source for the Chinese government, nontax revenues ‒ government funds, social security, and state capital operations income ‒ have increased since 2015.

Figure 4 Share of revenue from various sources (2010–2022).

Note: Data derived from the China Statistical Yearbook. Tax revenue is a major subcategory of General Public Budget Revenue; land transfer fees constitute a major subcategory of the Government Fund. The Social Security Fund excludes the fiscal transfer fund (from General Public Budget Revenue).

Figure 4Long description

The graph illustrates the share of China’s total revenue from various sources between 2010 and 2022, including General Public Budget Revenue, Government Fund (dominated by land transfer fees), State Capital Operations Income, Tax Revenue (as the major source of General Public Budget Revenue), Land Transfer Fee (as the major source of government fund), and Social Security Fund (excluding fiscal transfers from the General Public Budget). Data are from the China Statistical Yearbook. General Public Budget Revenue: The largest source, with a share that fluctuated slightly over 60% in 2010, a low of 53% in 2021. Its stability reflects its role as the backbone of fiscal income, though its relative share was pressured by the growth of land-related revenue. Government Fund: Highly volatile, driven by land transfer fees. It ranged between 18% to 28% from 2010 to 2022. State Capital Operations Income: The smallest source, consistently accounting for only 0.4% to 1.4% of total revenue, indicating limited fiscal contributions from state-owned enterprise (SOE) profits. Tax Revenue: The major fiscal revenue source, but it experienced steadily decline over the years, from 54% in 2010 to 45% in 2022. Land Transfer Fee: Composes around 21 percent of total fiscal revenue in 2010, with some fluctuations afterwards, reaching a bottom of 13 percent in 2015 a peak of 25 percent in 2020, then drops slowly. Social Security Fund: The only source with steady growth, rising from 11% in 2010 to 20% in 2022, driven by expanded social security coverage and aging population-related contributions.

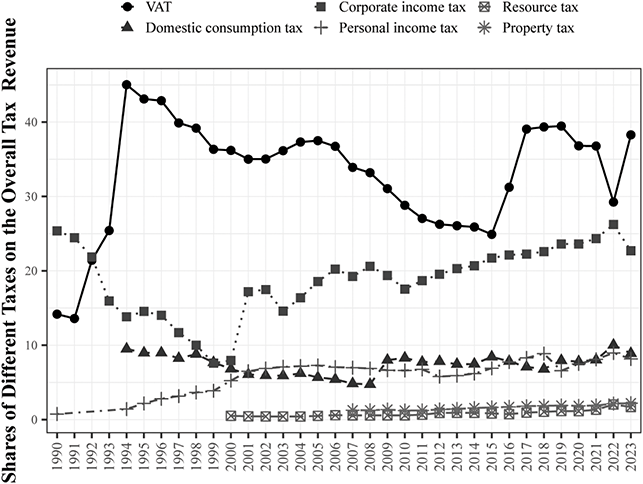

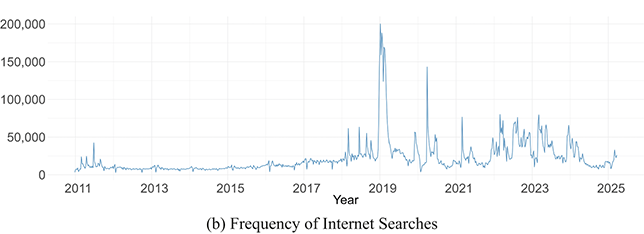

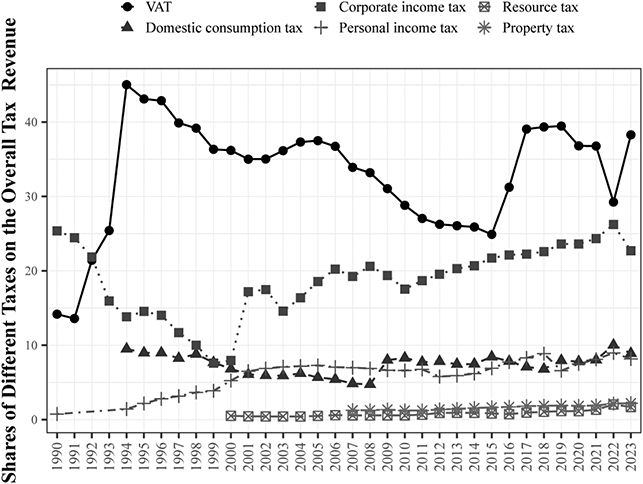

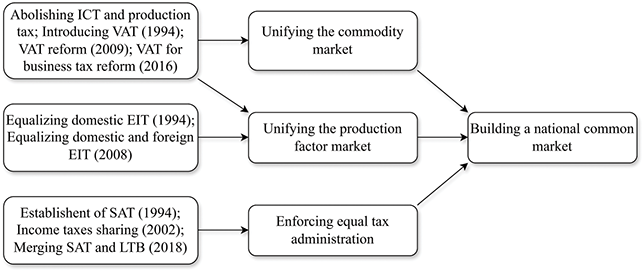

Now we turn to a narrower definition of fiscal revenue ‒ tax revenue. As in many nondemocratic regimes, China’s taxation capacity predominantly relies on indirect taxation, constituting approximately two-thirds of total tax revenue. In Figure 5, we deconstruct tax revenue by sources and trace their contribution to overall tax revenue from 1990 to 2023. The VAT emerges as the most important –its share in the total tax revenue consistently above 30% after the 1994 TSS reform. Although that figure has gradually declined since the late 2000s because of the rising contribution from personal and corporate income tax, it returned to become the primary source of tax revenue, especially after the BT (business tax)-to-VAT reform in 2016.Footnote 15 Meanwhile, corporate income tax has consistently risen since 2000, reaching 25% of total tax revenue by 2023. Personal income tax and domestic consumption have remained minimal, each contributing less than 10% of government revenue over time.

Figure 5 China’s structure of tax revenue (1990–2023).

Note: Data derived from the China Statistical Yearbook. The drop in VAT in 2021 occurred because the VAT allowance for refund policy was designed to stimulate economic growth during the COVID pandemic.

Figure 5Long description

The graph details the evolution of China’s tax revenue structure from 1990 to 2023, showing the proportion of total tax revenue contributed by six key taxes: Value-Added Tax (VAT), Corporate Income Tax (CIT), Resource Tax, Domestic Consumption Tax, Personal Income Tax (PIT), and Property Tax. VAT has been the dominant source. It accounted for 45% of total tax revenue in 1994 and steadily declined to 25% until 2015. The 2016 "Business Tax to VAT" reform temporarily increased its share to 44%. However, the 2021 VAT refund policy caused a sharp decline to 29%. By 2023, it had recovered to 38%, reaffirming its central role. Corporate Income Tax has been the second most important source of tax revenue, ranging between 17 to 26% from 1994 to 2023. Domestic Consumption Tax has been relatively stable, ranging from 5% to 10% from 1990 to 2004. Personal Income Tax (PIT) has exhibited a consistent upward trend, rising from less than 2% in 1990 to 6.7% after the 2011 PIT reform, and reaching 9% after the 2018 reform (which introduced special deductions). This growth has been driven by rising household incomes and improved tax collection and administration. Resource Tax & Property Tax have remained minor revenue sources. The Resource Tax increased from 0.5% to 2% (driven by rising resource prices and tax reforms), while the Property Tax has stagnated at 1% to 2.5%, indicating an underdeveloped property tax system that excluded household real estate property.

2.2.2 Fiscal Contribution from SOEs

A large, strong sector of SOEs makes a unique contribution to Chinese fiscal capacity. First, despite decades of market reform, SOEs and state-holding corporations are a major source of national tax revenue, contributing 31.7% of government revenue in 2014 whereas collective enterprises and collective holdings, about 34% (Zhang Reference Zhang2021: 56). Notably, the substantial tax contribution by SOEs can be attributed to their monopoly in sectors like energy, utilities, and finance.

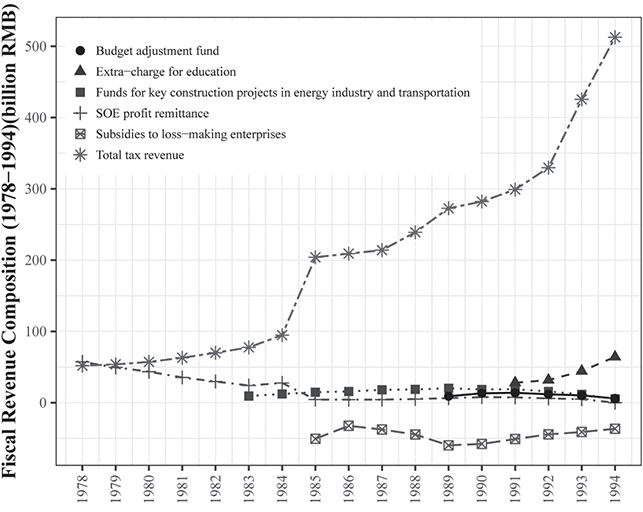

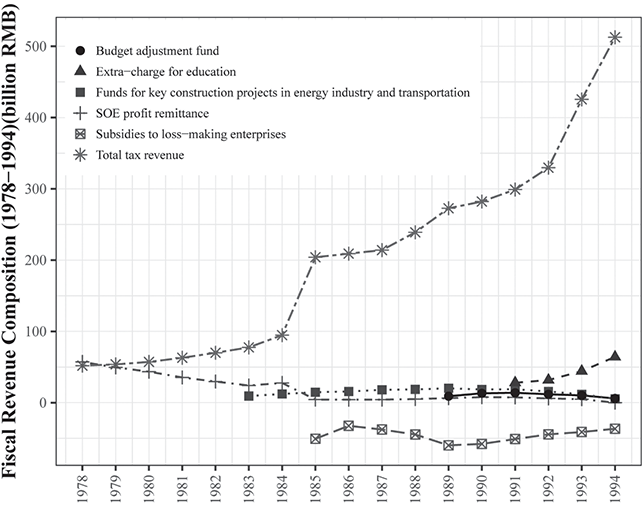

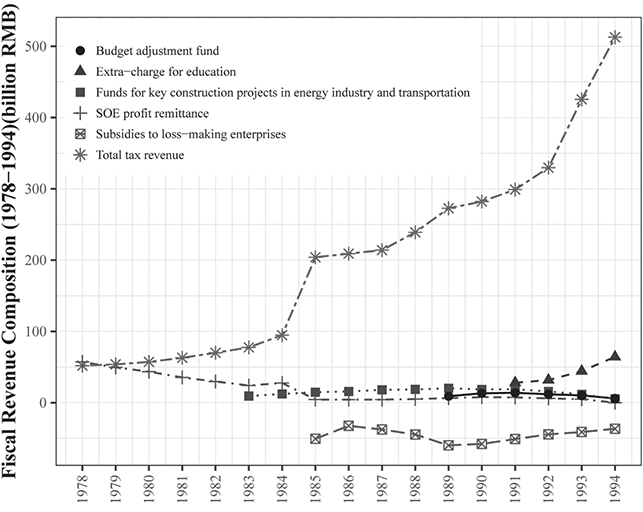

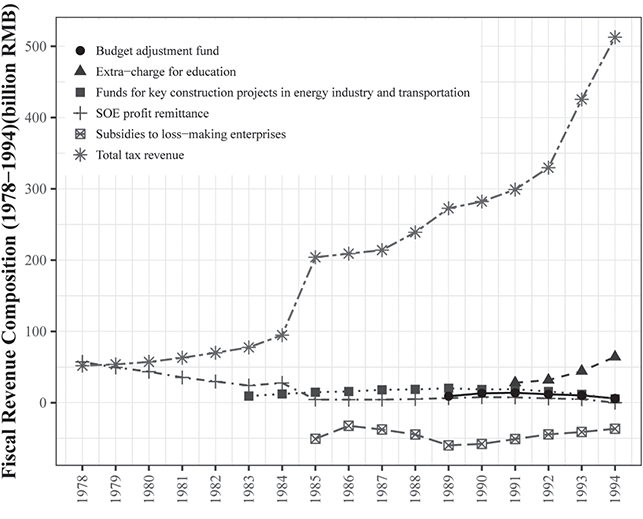

Second, SOE profit remittance, comprising half the national fiscal revenue before 1980, has been replaced by taxes as a consequence of 1984 and 1985 tax-for-profit reforms (Figures 6a and 6b). The SOE profit remittance drastically declined from 1993 to 2006 because of the dismal performance of most SOEs in the 1990s and early 2000s.

(a) Sources of fiscal revenue

Figure 6aLong description

The graph shows the composition of China’s fiscal revenue sources from 1978 to 1994, with values in billions of RMB. The indicators include the Budgetary Adjustment Fund, the Education Surcharge, the Fund for Key Energy and Transport Projects, SOE Profit Remittances, Subsidies to Loss-Making SOEs (shown as negative values), and Total Tax Revenue. Total Tax Revenue was the fastest-growing source, rising from 51.9 billion RMB in 1978 to 512.7 billion RMB in 1994-representing a nearly tenfold increase. This growth was driven by the 1983 to 1984 “Tax-for-Profit” reforms, which progressively replaced the system of SOE profit remittances with taxes. SOE Profit Remittances followed a declining trend, falling from 57.1 billion RMB in 1978 to 42.9 billion RMB in 1987, and nearing zero by 1994 (when the system was formally suspended under the 1994 TSS). This reflects the fundamental shift from direct “profit submission” to a modern “taxation” system for SOEs.

(b) Tax revenue and share of fiscal revenue from SOE remittance

Notes: Data derived from China Statistical Yearbook. The SOE profit remittance was suspended in 1994, so the sum of shares in (b) does not equal or exceed 100 because of other revenue sources and subsidies to lose-making SOEs (negative). Fiscal revenue here refers to General Public Budgetary Revenue.

Figure 6bLong description

The graph compares the shares of China’s General Public Budget Revenue contributed by Total Tax Revenue and SOE Profit Remittances from 1978 to 1994. The sum of the two shares never reaches 100% due to the existence of other revenue sources and the negative impact of subsidies to loss-making SOEs. Total Tax Revenue Share exhibited a steady and significant upward trend, rising from less than 50% in 1978 to over 80% after 1985, and reaching 92% in 1994. The 1983 to 1984 “Tax-for-Profit” reforms were pivotal to this increase: the tax share jumped from 58% in 1982 to 65% in 1983 and 82% by 1985, as SOE profits were progressively converted into tax payments. This reform formalized the fiscal relationship between the state and enterprises. SOE Profit Remittance Share experienced a steady decline, falling from 35% in 1978 to 20% in 1983, 10% in 1985, and nearly 0% by 1994. The 1994 Tax Sharing System (TSS) formally suspended the SOEs’ profit remittance system until 2007, shifting SOE contributions entirely to taxes, primarily the Corporate Income Tax.

Figure 6 SOEs fiscal contribution (1978–1994)

Nonetheless, SOEs reemerged as a major force in the Chinese economy, an increasingly important fiscal revenue source.Footnote 16 From 2013 to 2022, a total of 18.2 trillion yuan was submitted by central SOEs (央企) through taxes and fees, accounting for about one-eighth of the national tax revenue: 1.3 trillion yuan to state capital operation income and another 1.2 trillion yuan to the Social Security Fund.Footnote 17 Notably, only the profits of nonfinancial SOEs are included in the state capital operations budget as profit submission and are then used to supplement General Public Budget Revenue through the transfer of funds. The profits submitted by financial SOEs are not included in state capital operations income but are managed by the Ministry of Finance (MOF) separately and included in the nontax revenue of General Public Budget Revenue. However, central SOEs’ profit remittance is still very limited compared to their profits. For example, central SOEs had a total profit of 2.55 trillion yuan and submitted 2.8 trillion as taxes and fees in 2022, while SOEs’ profit remittance contributed only 172 billion yuan to state capital operation income.Footnote 18 This contribution should be discounted as the government returns most profits submitted by SOEs through reinvestment, therefore contributing even less to fiscal revenue.

In addition to the two routine channels, the Chinese central government mandates specific state-owned financial and franchised institutions, such as the China National Tobacco Corporation, to remit their accumulated profits in a lump sum (as nontax revenue) during periods of economic hardship. The profits should be transferred to the government-managed fund budget as ‘special profits turned over by central government units’ and transferred to the general public budget as needed. In 2022, for example, the People’s Bank of China, its central bank, turned over 1.13 trillion yuan in surplus profits to the country’s central budget to “support enterprises, stabilize employment and ensure people’s well-being.”Footnote 19

2.3 Administrative Foundation of China’s Taxation Capacity

Developing a strong bureaucratic capacity for taxation is a challenging task for any country, and China is no exception. Since its transition to a market economy in the 1980s, the Chinese government launched several waves of reform to strengthen its taxation capacity. In this section, we briefly overview the evolution of China’s tax administration since the 1980s,Footnote 20 then discuss a unique practice of China’s tax administration ‒ the tax targeting system ‒ which allows the Chinese Central Government to ensure compliance from low-level government in tax collection.

2.3.1 Evolution of the Tax Administration

China decentralized its tax administration in the 1980s to operate as a subsidiary of the MOF. Thus, local tax bureaus were directly managed by corresponding local finance bureaus and, by extension, local party and government authorities ‒ a structure known as horizontal management.Footnote 21 The state administration of taxation was a semi-ministerial-level agency at the national level under the MOF but lacking direct power to command tax bureaus at the provincial level, which were controlled by provincial governments. Under this arrangement, tax administration was decentralized to local governments, which collected tax revenue and then remitted part of it to higher-level governments.

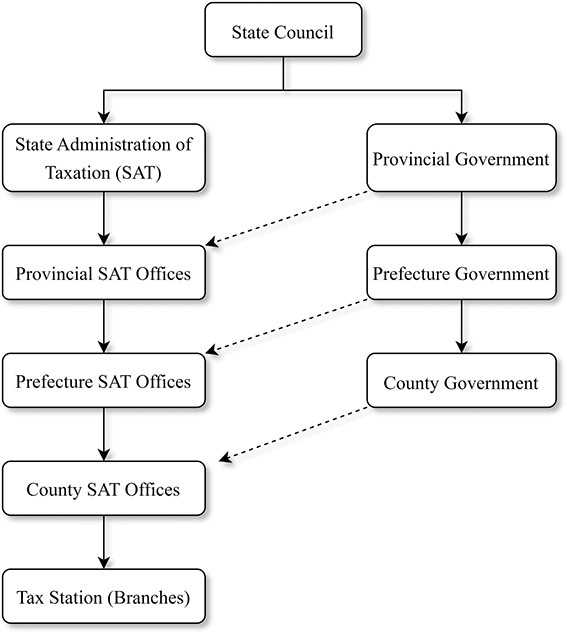

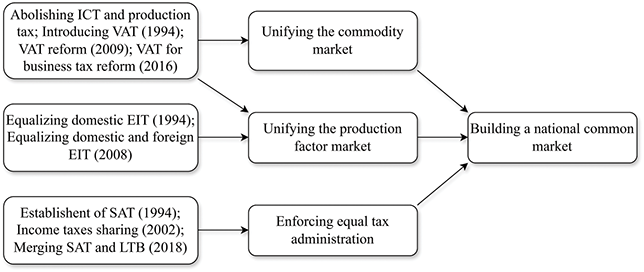

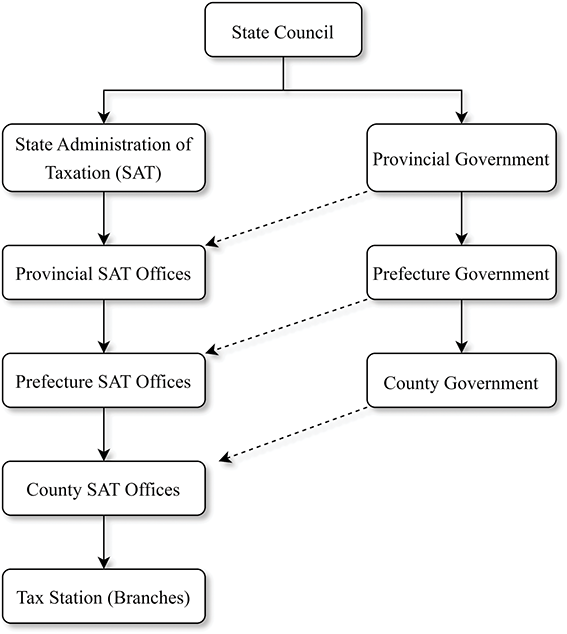

The 1994 Tax Sharing System (TSS) reform was designed to institutionalize spending obligations and tax sharing between central and local governments, specifically to recentralize the taxation power. To facilitate tax collection, the TSS reform established two independent and vertically managed taxation bureaus: The State Administration of Taxation (SAT) and the Local Taxation Bureau (LTB). The SAT falls under the direct leadership of the Chinese Central Government (State Council) as a ministerial-level institution. Although the SAT is independent from the MOF, the personnel of these two agencies maintain close working relationships. For instance, SAT directors usually have prior experience at the MOF before their appointments. Although the SAT was institutionally independent from the local government, LTBs operated under dual leadership, reporting to both the higher-level LTBs and local governments in jurisdictions where they are located. Notably, the higher-level LTBs – or the SAT in the case of a provincial-level LTB – had greater administrative authority in appointing local LTB directors and supervising their size and organizational issues.

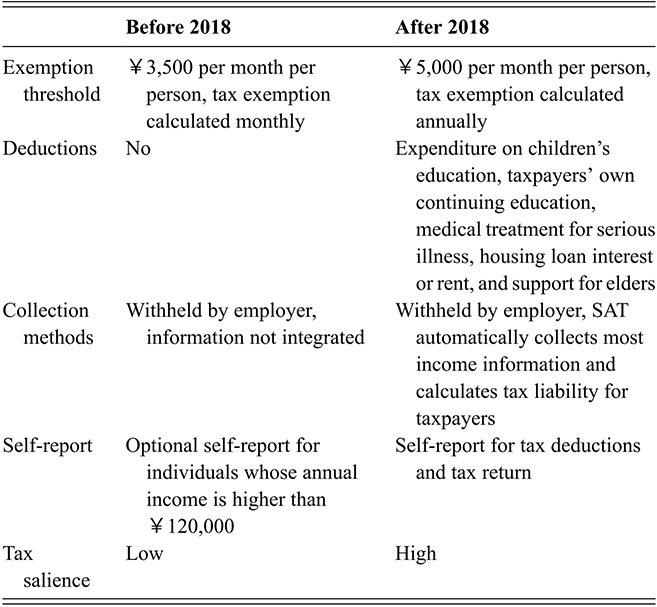

Both the size and capacity of China’s tax administration experienced rapid growth after the 1994 TSS reform. Together, the SAT and LTB employ about one million people; furthermore, both are equipped with more professionals than their predecessors, up-to-date information technology and equipment, a rationalized management system, and an improved taxation capacity. In 2018, the SAT and LTB were merged into the new SAT, designed to further streamline tax collection and improve administrative efficiency. In addition, the Social Security Fund collection was assigned to the new SAT. Compared to the Bureau of Human Resources and the Social Security Administration, the new SAT now has a much greater capacity for fee collection, further strengthening its taxation capacity. Figure 7 reflects the organizational structure of China’s tax administration after 2018.

Figure 7 Organizational structures of tax administrations in China (2018–Present).

Notes: This figure is based on Figure 5 in Cui (Reference Cui2022: 170), but we provide a more detailed demonstration of the relationships among levels of government and SATs at several levels.

2.3.2 The Tax Target System

Despite the Chinese government’s endeavor to transition into a modern tax state through these major fiscal reforms, its taxation system retains an important legacy of the previous fiscal system under the planned economy and the unitary system ‒ the tax target system ‒ for the purpose of revenue mobilization (Cui Reference Cui2022). Although the Chinese government has maintained the importance of Rule by Law,Footnote 22 many tax liabilities are not in fact designated by law (依法征税) but according to the revenue targets set by their supervisors (higher-level tax bureaus and governments at the corresponding levels) and informal agreements between tax administrators and taxpayers. Specifically, higher-level tax bureaus and the local governments set specific tax revenue targets for both the county SAT office, within which all the tax collection agents (tax office and tax officials) have specific tax collection targets (税收任务). These targets are reminiscent of the fiscal contracting system that the 1994 TSS reform was intended to replace. Notably, the tax bureaus are vertically managed, and local governments do not have the power of personnel management to directly pressure SATs to fulfill these targets. Instead, a common method to motivate local tax bureaus is financial reward;Footnote 23 consequently, the tax target system undermines the institutionalization of tax collection because it violates the rule of law in the realm of taxation (Zhang Reference Zhang2021).

The primary objective of the tax target system is to incentivize tax bureaucrats at various levels to enhance tax collection efforts (Cui Reference Cui2022; Zhang Reference Zhang2021). Notably, the Chinese government has a decentralized administrative system given its vast territory, and local politicians are not accountable to residents because of the lack of meaningful elections. The CCP developed a nomenklatura system to use career incentives to motivate and monitor local officials (Landry Reference Landry2008; Whiting Reference Whiting, Naughton and Yang2004). Local CCP committees, with assistance from the Party’s Organization Department, evaluate the cadres’ performance and punish or reward them through a cadre management systemFootnote 24 that covers economic growth, tax revenue, social stability, environmental protection, and population control. These metrics are adjusted from periodically, depending on the Party’s political priorities. Organizations and individuals accomplishing or exceeding the target are rewarded both economically (bonus) and politically (better opportunity for promotion).Footnote 25 Notably, local cadres view nomenklatura as a pressure-based system (压力型体制) (Rong Reference Rong1998). In the realm of taxation, revenue targets are divided into smaller quotas and assigned to lower-level government organizations or individuals expected to meet these targets within a specified timeframe.Footnote 26

2.4 Conclusion

This section maps out China’s taxation system within the broader context of fiscal capacity. To some extent, China’s rising fiscal capacity since the reform era aligns with the predictions in the theoretical framework proposed by Besley and Persson’s (Reference Besley and Persson2011). Unlike the Maoist period (1949–1976), the reform era has been characterized by prolonged political stability, rising per capita income, and cohesive political institutions committed to a common objective ‒ economic development. China’s taxation capacity development, however, diverges from this framework in notable ways, particularly in the government’s reluctance to expand direct taxation. Instead, it has persistently relied on indirect taxation and nontax revenues as the primary source of fiscal revenue. In the next section, we explore the political logic behind the design of China’s tax system and tax reforms, demonstrating how strategic interactions between the central and local governments have been pivotal in its evolution. In Sections 4 and 5, we examine how China’s taxation system influences the behaviors of local governments, citizens, and businesses as well as the dynamics of their interactions.

3 Political Logic of Taxation in China

Our country is so large with such an enormous population, and the situation is so complicated, with both central and local initiatives, which are much better than having only one initiative… . We should promote the style of handling affairs in consultation with the local authorities. When handling affairs, the Center should always consult with the local authorities and never give orders blindly without consulting with different authorities.

Taxation manifests the state’s endeavor to extract economic resources from the society, making it a focal point for state‒society tensions. Arising from fiscal policies, conflicts in democracies are often mediated through electoral competition, where tax policy design reflects the aggregation of mass preferences shaped not only by voters’ self-interest but also by the influence of political and economic elites on public opinion. By contrast, policymaking in autocracies is typically insulated from public scrutiny and interparty competition, rendering a different logic behind the design of tax policy.

Although the CCP remains the dominant ruling party with supreme authority in the political system, it gradually delegated the design and implementation of economic policies to the government apparatus, reflecting a fundamental shift in its priorities from political struggle to economic development.Footnote 27 Shirk (Reference Shirk1993) underscores the institutional contours (i.e., the separation of the party and state in economic policymaking and the political competition among elites striving for political appointment) as key drivers behind China’s economic and fiscal reforms. Importantly, Shirk proposes a selectorate model,Footnote 28 in which “reciprocal accountability” exists among elites holding leadership positions in the party, government, and military. Although high-level officials are appointed by the CCP Politburo and its Standing Committee, they wield significant influence in shaping the competition among party leaders vying for ascension to the very pinnacle of China’s political hierarchy. Policymaking in China, therefore, is essentially a process of elite bargaining and factional struggle, engineered by high-level elite CCP members who seek support from leaders in ministerial bureaucracies and provincial governments.

This logic is reflected by the characterization of China’s policymaking process from the perspective of “fragmented authoritarianism” (Lieberthal Reference Lieberthal, Lieberthal and Lampton1992; Lieberthal and Oksenberg Reference Lieberthal and Oksenberg1988), revealing that the Chinese government is not a monolith but a complex system comprising multiple political elites, each overseeing distinct policy domains. These political leaders have conflictual or complementary policy goals, and policy outcomes reflect the distribution of power and coalition building among them. The authority structure became decentralized and fragmented after Mao; therefore, policymaking now requires building a unified consensus within bureaucratic systems. Consequently, the policymaking process results from governmental bargaining and consensus building by horizontal bureaucracies (ministries) with “department parochialism” and vertical government agencies (local party government) with “local protectionism.”

Among the layers of governmental relations, central‒local interaction plays a vital role in shaping China’s tax policies. Effective fiscal centralization is considered a hallmark of the modern tax state (Dincecco Reference Dincecco2009), but it is not only about placing the power of tax policymaking into the hands of the central government, which may hold de jure authority in designing and legislating tax policies. Local governments, however, maintain de facto power in policy implementation; therefore, the central government must be mindful of their preferences and negotiate with them during the policymaking process to ensure smooth policy implementation.

Viewing tax policies through the lens of central‒local relations, we investigate the central and local governments’ fiscal policy goals and behaviors, particularly in the realm of taxation. We show that the central government faces a trilemma of revenue extraction, economic growth, and political stability, employing legislative power and career advancement to incentivize local governments to achieve their objectives. Meanwhile, local governments, broadly aligned with central government objectives like economic development and revenue generation, selectively implement tax policies to advance their own interests. Given the short time horizon of local governments, their policy choices often engender political instability or deviations from the objectives of the central government, worsening the trilemma faced by the latter. In the context of the trilemma, we then briefly discuss the motivation and outcomes of several major fiscal and tax reforms in China since the 1980s.

3.1 Central Government Trilemma: Balancing Multiple Policy Goals

What does the Chinese central government seek to accomplish through its tax policies? Bolstering the state’s fiscal capacity through tax revenue is the most obvious objective. In addition, the Chinese government considers tax revenue an important instrument for stimulating economic growth, particularly through government capital investment and public goods provision. Finally, maintaining political stability is the foremost concern for any single-party regime. Hence, the Chinese government must carefully considers the direct and indirect impact of its tax policies on political stability. These policy goals were explicitly laid out in the Communiqué of the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the CCP in 2018: [Public] finance is the foundation and an important pillar of state governance. Good fiscal and taxation systems are the institutional guarantee for optimizing resources allocation, maintaining market unity, promoting social equity, and realizing enduring peace and stability.Footnote 29

Some governments invest in expanding taxation capacity and strengthening representative institutions, leading to the formation of a “developmental cluster,” where high taxation, political stability, and a high level of development could coexist (Besley and Persson Reference Besley and Persson2011). Representative institutions aggregate mass preferences and translate them into public expenditure, which in turn promotes economic growth, enhances tax compliance, and strengthens regime legitimacy. Meanwhile, nondemocratic regimes could achieve revenue extraction, economic growth, and expanded public spending to maintain political stability (Acemoglu Reference Acemoglu2005; Morrison Reference Morrison2015). These outcomes are, however, often sustained through nontax revenues like natural resource endowments. In the absence of representative institutions and abundant natural resources in China, balancing these three policy goals poses an acute challenge. Scholars have documented local governments prioritizing economic growth at the expense of environmental protection and labor relations.Footnote 30 When the Chinese government expands social welfare to ease state‒society tensions stemming from rapid economic growth and rising inequality, its policies have yielded limited improvements in citizen trust (Li et al. Reference Ding, Lü, Shuang and Yang2025; Lü Reference Lü2014; Yang and Shen Reference Yang and Shen2021), sometimes even serving as instruments of surveillance and repression (Pan Reference Pan2020).

Equally important, Besley and Persson (Reference Besley and Persson2011) underscore the cohesiveness of political institutions as pivotal in shaping fiscal capacity, alongside other complementary elements in the development clusters. The institutional design of China’s central‒local relations creates conflicting interests between central and local leaders. For instance, the 1994 TSS reform enabled the central government to retain most of the revenue surplus, leaving local governments grappling with persistent budgetary constraints. This is exacerbated by pervasive unfunded mandates, compelling local authorities to implement policies without necessary financial support, further straining their fiscal resources (Wong and Bird Reference Wong, Bird, Brandt and Rawski2008). Meanwhile, economic growth has been a cornerstone of the CCP’s “performance legitimacy,” crucial in maintaining popular support (Dickson Reference Dickson2016; Zhao Reference Zhao2009). The emphasis on promoting economic development, however, prevents the government from imposing heavy tax burdens onto firms, which sometimes even receive illicit tax breaks from local governments. Similarly, efforts to expand public goods and social welfare may support political stability in the short term, but they could strain fiscal resources and hinder long-term economic growth if improperly managed.

Figure 8 illustrates the trilemma the Chinese government faces concerning the delicate balance among these policy goals. In the remainder of this section, we first highlight the importance of these three policy goals to the Chinese central government. We then discuss the ways the central government addresses the tradeoffs among them through tax systems and policy adjustments. In Section 3.3, we offer a nuanced discussion on how specific reforms prioritized one aspect of the trilemma while generating unintended consequences for the others.

Figure 8 The trilemma among policy goals

3.1.1 Central Government’s Objectives

Fiscal Revenue. “Revenue enhances the ability of rulers to elaborate the institutions of the state, to bring more people within the domain of those institutions, and to increase the number and variety of the collective goods provided through the state” (Levi Reference Levi1988: 2). Fiscal revenue is indispensable for any state ‒ including the CCP ‒ in performing government functions. As a late industrializing country, the CCP pursued the model of a planned economy in the 1950s by following that of the Soviet Union and taxed the peasants heavily to support rapid industrialization. After the 1994 TSS reform, increased tax revenue empowered the central government to finance important initiatives ‒ capital investment, national defense, and intergovernmental transfers as well as the expansion of the provision of public goods and services in the last two decades. During economic downturns, the central government often becomes the ultimate, if not the sole, source of emergency spending to stimulate the economy and provide bailouts for financially struggling local governments. Notably, the central government aims to maintain macroeconomic stability while promoting economic growth. Before the transition to a market economy, the Chinese government relied on administrative tools but not fiscal and financial policies for macroeconomic management (Huang Reference Huang1996). After transitioning to a market economy, fiscal policies became a more effective tool for macroeconomic management (Liu and Fu Reference Liu and Zhihua2018: 165).

Economic Growth. Recognizing the importance of performance legitimacy as a substitute for charismatic legitimacy, the CCP shifted its focus from class struggle to economic development in the late 1970s. Deng Xiaoping (Reference Deng1983: 214) famously said, “Development is the absolute principle,” acknowledging that bringing prosperity to the people would revive popular support for the CCP after years of political and economic turmoil from 1949 to 1978. The Chinese government prioritizes promoting economic growth by maintaining a light tax burden, with the hope that rapid economic growth will lead to greater tax revenue in the long run. The CCP leaders, including Mao Zedong, recognized the intricate relationship between economic growth and fiscal revenue as early as 1942. He said: “It is true that the quality of fiscal policy affects the economy, but it is the economy that determines public finances. No one can solve the financial difficulties without an economic foundation, and no one can make public finances adequate without economic development.”Footnote 31

Political Stability. The ultimate priority for the Chinese government has always been political stability. Despite his desire to pivot the CCP’s priority to promoting economic growth, Deng Xiaoping reminded party leaders that “[political] stability is a principle of overriding importance” (Deng Reference Deng1993: 363). Facing mounting social discontents stemming from two decades of economic reforms, the Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao administration shifted the national development priority in the mid-2000s from solely promoting economic growth to implementing the so-called “scientific outlook of development” (科学发展观) along with a “harmonious society (和谐社会),” emphasizing more expenditures on public goods provision. Meanwhile, stability maintenance became an increasingly pressing issue for the CCP, eventually leading to the establishment of a costly stability maintenance system under the leadership of Zhou Yongkang, then a standing committee member of the Politburo in charge of the Central Politics and Law Commission. Despite Zhou’s downfall during Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign in 2014, this stability maintenance system has been further enhanced and expanded. Xi continues to emphasize the importance of political stability by advocating for a comprehensive view of national security. He calls for integrated planning that accounts for both development and national security.

3.1.2 Taxation Strategies of the Central Government

As shown in what follows, the Chinese central government has developed several strategies to balance the trilemma of policy objectives. We detail the evolution and tradeoffs of these strategies in turn.

Centralization of Legislative Power in Taxation. Under China’s one-party regime, the CCP Central Committee, the National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee (NPCSC), and the State Council wield the ultimate legislative power necessary to promulgate laws and regulations for taxation; and they could override those made by the subnational legislatures.Footnote 32 China’s governance structure has undergone several centralization‒decentralization cycles since 1949 as did the degree and form of taxation power.

In 1950, the newly established Government Administration Council of the Central Government of China (replaced by the State Council in 1954) issued the Decision on the Unifying National Tax Administration. This directive required that prefectural and county governments obtain provincial approval for tax legislation while provincial tax policies required authorization from the central government.Footnote 33 The tax legislation power was then decentralized from 1958 to 1970, offering provincial governments greater autonomy in making tax policy. In 1977, however, the Chinese central government recentralized the tax legislation power, when the State Council approved the MOF’s Request for Instruction on the Tax Administration System (Editorial board of Contemporary China Finance 1990). This move became a new starting point for subsequent tax reforms in 1980s and 1990s (Cui Reference Cui2012; Zhang Reference Zhang2018: 20‒21, 60‒64).

Specifically, the State Council maintained greater autonomy in tax policymaking. For instance, the NPC delegated tax legislative power to the State Council in 1984, allowing the latter to create bylaws, regulations, and temporary or transitional measures related to taxation without engaging in the legislative process at the NPC. Even the 1994 TSS reform bypassed the NPC or NPCSC: It was approved only by the CCP Central Committee and the State Council. The only exceptions in tax legislation were those related to foreign individuals and entities, such as the PIT (initially targeting foreigners in the early 1980s) and the foreign enterprise income tax law.

The NPC and the State Council possess the legislative authority to introduce new taxes, reform existing ones, and restructure the tax system to broaden the tax base and enhance its rationality. Through these measures, they seek to strengthen fiscal capacity and advance the development of a socialist market economy. Notably, despite the centralization of legislative power in taxation, the tax administration is highly decentralized because of China’s vast size and uneven development. The central government can enact tax policies as it sees fit with the full understanding that the enforcement of these laws and policies depends heavily on the efforts of local governments, which hold significant discretionary power in policy implementation, a realm lying beyond the central government’s full control. Hence, the central government must ensure that when making tax policy, the incentive structure of local governments is considered in its implementation.

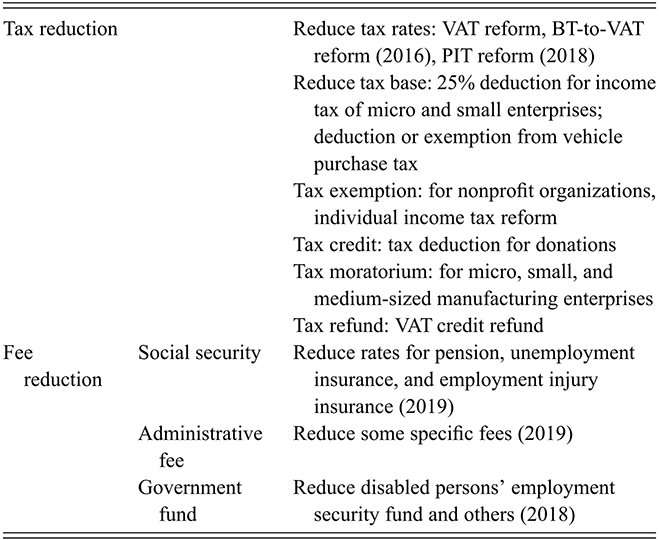

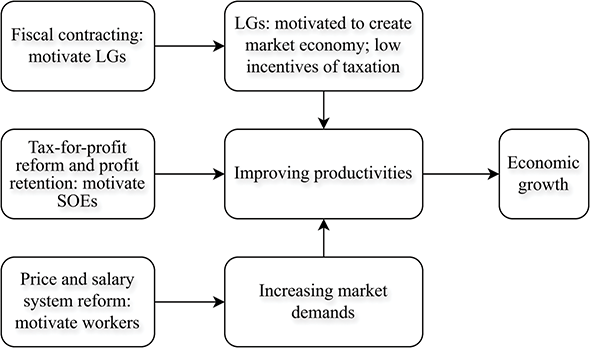

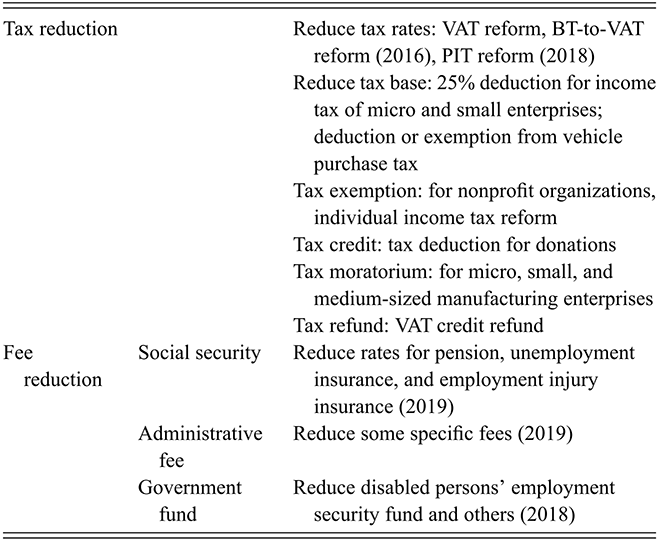

Institutionalization of Taxation to Stimulate Economic Growth. A well-functioning market economy ‒ where market prices serve as key signals for business operations ‒ is essential for fiscal policies to effectively serve as instruments for microeconomic management. As China transitioned to a market economy after 1992, fiscal policies were increasingly designed to fulfill this purpose (Huang Reference Huang1996; Yang Reference Yang2020: 6‒9). Specifically, tax and fee reduction (TFR) has been a primary instrument to stimulate economic growth since 2008. Initially, the Chinese government called it “structural tax reduction,” associated with tax and fee reform and “universal tax deduction.” Furthermore, the Chinese government shifted from a proactive expansionary fiscal policy to TFR for the purpose of stimulating economic growth since 2015, resembling a fundamental part of supply-side structural reform.

Tax and fee reduction has frequently appeared in government work reports and the formulation of macroeconomic policies since 2008 (see Table 2 for a list of these policies). For instance, the VAT reform (including BT-to-VAT reform) was announced to stimulate businesses, and the PIT reform was intended to stimulate domestic consumption. In addition, the central government launched a wide range of policies to support small and micro enterprises, venture capital investment, and technological innovation. Between 2012 and 2017, the BT-to-VAT reform reduced an estimated 2 trillion yuan in tax burdens, and other tax and fee deduction policies reduced the equivalent of another 1 trillion. In 2018, an estimated 800 billion in tax deductions and 300 billion in fee deductions occurred (Zhang and Yang Reference Yang2020: 224). Now it covers the process of production, investment, consumption, and innovation.

3.2 Local Government Challenge: Fulfilling Competing Mandates

Local governments serve as agents of the central government under China’s unitary political system. To entice compliance from local governments, the CCP has established a nomenklatura system operating as a pressure-based system (see Section 2.3.2). Although they share many policy goals with central authorities, they face competing and sometimes conflicting mandates from higher-level government. Hence, local politicians strive to selectively fulfill these policy targets, particularly those quantitatively measurable (O’Brien and Li Reference O’Brien and Lianjiang1999).

Collecting tax revenues has consistently ranked among the most crucial indicators in the evaluation of local officials. The primacy of taxation in cadre evaluation is twofold. First, given that officials tend to manipulate GDP data, tax revenue serves as a more reliable indicator of local officials’ performance (Lü and Landry Reference Lü and Landry2014). Second, greater tax revenue enables local government to finance local public spending, from urban development to local public goods provision, crucial to fulfill the unfunded mandates from the central government (Wong and Bird Reference Wong, Bird, Brandt and Rawski2008). The 1994 TSS reform expanded expenditure obligations for local governments while shrinking their share of tax revenue; therefore, raising tax revenues became an imperative for local governments. In the following sections, we first provide a brief overview of local governments’ objectives regarding taxation within the framework of the cadre management system, then explore how local governments use taxation to meet policy targets set by higher-level authorities.

3.2.1 Objectives of Local Governments

By and large, local governments prioritize four policy areas: promoting regional economic growth, fulfilling the taxation revenue quotas, financing local public spending, and maintaining local stability.

Economic Growth. Economic growth became a primary policy objective after CCP leaders shifted their top priority from class struggle to economic development and pursuit of the “four modernizations” (四个现代化) in 1978. Consequently, the political selection of local politicians has been increasingly based on local economic performance, not simply ideological conformity or personal ties. Some scholars argue that local politicians participate in a “promotion tournament,” in which those who achieve better GDP growth rates in their jurisdictions are rewarded with promotions (Li and Zhou Reference Hongbin and Zhou2005; Yao and Zhang Reference Yao and Zhang2015). By tying cadre promotion to economic growth, the central government creates strong incentives for local politicians to engage in economic development, explaining China’s rapid growth in the last three decades.

Fulfilling Quotas for Taxation Revenue. The quota system for tax revenue, a remnant of the planned economy, involved higher-level governments setting quotas for tax revenues for remission by lower-level governments (see Section 2.3.2 for more detail). This practice persisted into the fiscal contracting system of the 1980s, where lower-level governments signed tax contracts with higher-level authorities, specifying tax quotas and annual growth rates.

The typical practice of the tax quota entails the following steps. At the beginning of a year, usually around the time of the NPC Annual Meeting in March, the central government officially announced the targets for annual GDP growth rate and fiscal revenue. Once the total fiscal revenue target was established, it was distributed among lower-level governments. Local governments meeting or exceeding their tax revenue targets were rewarded both economically (through bonuses) and politically (with better promotion prospects). No standardized procedure or scientific method was in place for setting these targets; instead, they reflected the preferences of party‒government leaders (Cui Reference Cui2022; Zhang Reference Zhang2021).

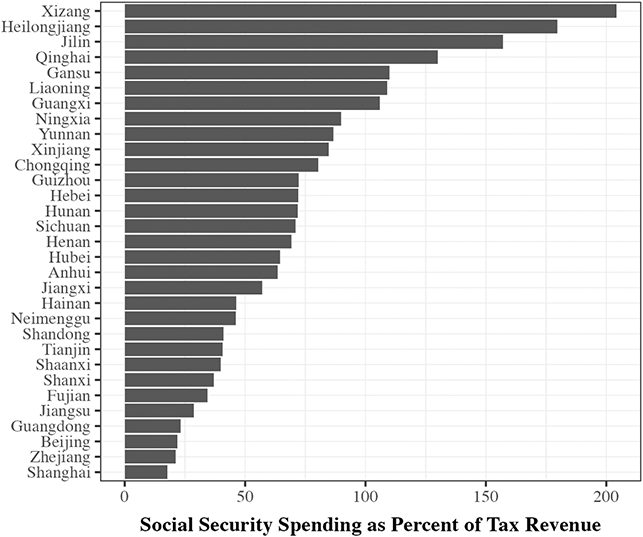

Financing Local Public Spending. Economic growth is not the only source for the Chinese government’s performance legitimacy. The expansion of public goods provision is another way to enhance its popular support. Since 2002 under the Hu‒Wen regime, the CCP responded to rising social discontent by expanding social spending. For instance, the Chinese central government launched several initiatives to expand public goods provision in both rural and urban China in the 2010s, including the abolition of compulsory school tuition and fees (Lü Reference Lü2014) and the expansion of rural healthcare and pension system (Huang Reference Huang2014) as well as the institution of the social protection program (Huang Reference Huang2020; Pan Reference Pan2020). Although the central government has established various intergovernmental transfers to assist local governments in financing these policy initiatives, local governments bear responsibility for covering most expenses.Footnote 34 Consequently, local governments face mounting pressure to identify fiscal resources to fund these mandates from higher-level governments.

Maintaining Local Stability. Promoting rapid economic growth can be costly. Chinese society has experienced rising social contention since the 1990s, driven by a wide range of issues like SOE reform, rural governance, labor conflict, government land expropriation, and environmental degradation.Footnote 35 Since 2008, stability maintenance has become a crucial criterion for evaluating local governments’ performance, especially at the county and township level. Because those in higher-level governments view stability maintenance as a veto issue and citizens recognize that grassroots governments may make concessions, maintaining stability has increasingly become an expensive endeavor, consuming a substantial portion of local expenditures.Footnote 36 Not only do local governments use social spending to mitigate potential social unrest, but they also sometimes outsource coercion to nonstate actors in order to quell social contention from citizens (Ong Reference Ong2022).

3.2.2 Taxation Strategies of Local Governments

The previous section underscores how local governments must navigate a range of competing mandates from higher-level governments, requiring them to balance their efforts across multiple goals. Their tax collection strategies are primarily influenced by two key factors. First, the degree of political competition for promotion shapes local politicians’ intensity in tax collection. Second, competing mandates compel local governments to exercise their discretionary authority in policy implementation, either offering tax incentives or adopting aggressive tax collection practices.

Interjurisdiction Competition and Tax Collection. Scholars have attributed China’s success in promoting economic growth to regionally decentralized authoritarianism (RDA), characterized by highly centralized political powers and high-decentralized administrative and economic powers (Jin, Qian, and Weingast Reference Hehui, Qian and Weingast2005; Landry Reference Landry2008; Montinola, Qian, and Weingast Reference Gabriella, Qian and Weingast1995; Xu Reference Chenggang2011). Under RDA, local politicians are incentivized to engage in interjurisdictional competition in the realm of economic development and fiscal extraction to enhance prospects for their promotion (Jia, Kudamatsu, and Seim Reference Jia, Kudamatsu and Seim2015; Landry, Lü, and Duan Reference Landry, Lü and Duan2018; Li and Zhou Reference Hongbin and Zhou2005).

Most local officials actively seek promotion but do not always maximize tax revenue in this endeavor: Not only does an onerous tax burden hinder economic growth, but it could also undermine the political stability valued by higher-level governments. Furthermore, the level of fiscal revenue is not only determined by local officials’ efforts but also by local economic endowments (e.g., geographic locations, human capital accumulation, and natural resources), and sometimes luck (e.g., external economic booms and crises, natural disasters). Consequently, local officials may exert varying degrees of effort in tax collection. Lü and Landry (Reference Lü and Landry2014) present a theoretical framework undergirding the logic of interjurisdictional political competition and fiscal extraction in China, proposing an inverted U-shaped relationship between the intensity of political competition and fiscal revenue. The intuition behind this framework is that local politicians exert minimal effort when political competition is either too intense or too weak as fiscal revenue becomes less pivotal in both scenarios.

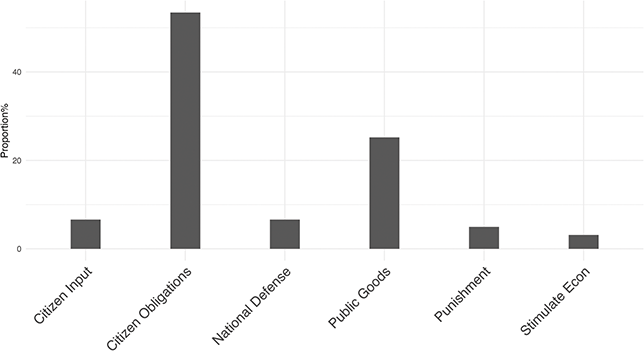

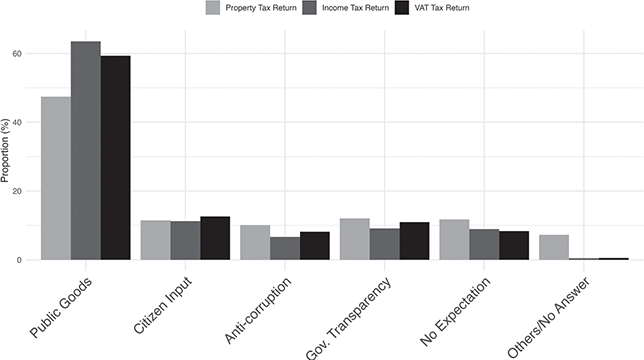

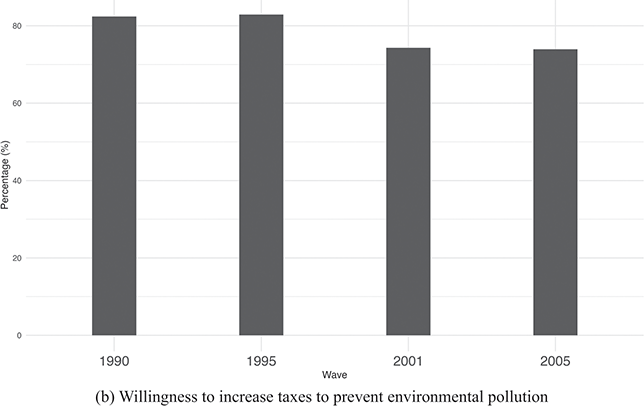

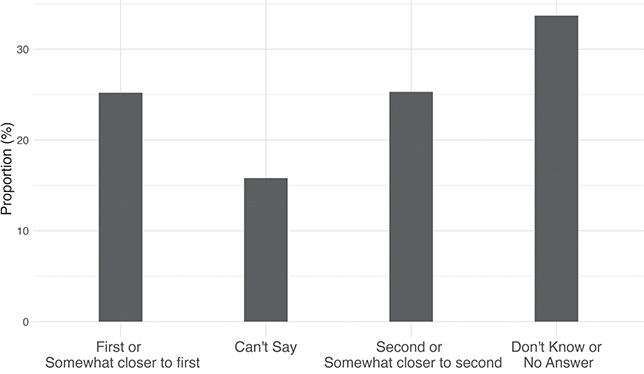

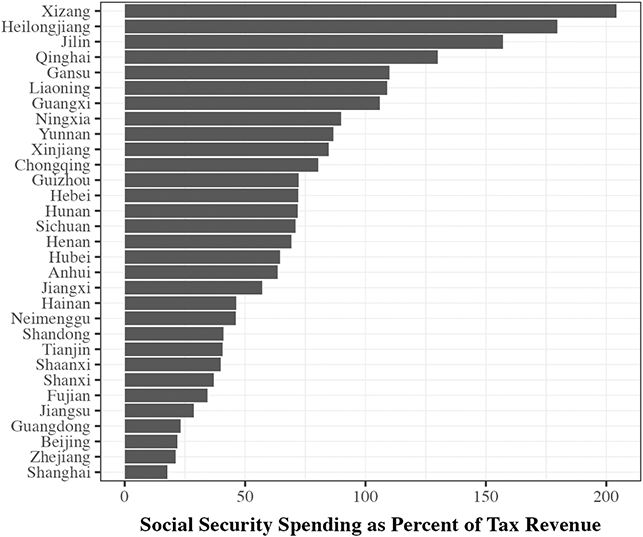

Discretionary Power of Local Governments. Given the competing mandates imposed by higher-level governments, local politicians employ diverse tax strategies to navigate these pressing needs. Specifically, although local governments have no legislative power to set tax rates or change tax policies, they wield considerable discretion in implementing tax policies; therefore, local governments concurrently employ strategies of generous tax rebates and predatory tax collection.