Introduction

With the spectre of an economic crisis looming, political leaders will face tough policy choices. A key question whose answer will likely drive these decisions is whether the adoption of austerity, defined as “a restrictive fiscal economic programme that prescribes a reduction of government budget deficits and a stabilization of public debt” and “entails cuts in public spending, an increase in taxation, or a combination of both” (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021, p. 486), will negatively impact an incumbent party's electoral support. The literature does not provide a clear‐cut answer: some argue that austerity is electorally inconsequential (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Perotti, Tavares, Obstfeld and Eichengreen1998, Reference Alesina, Carloni and Lecce2012; Arias & Stasavage, Reference Arias and Stasavage2019), while others find the opposite (Bojar et al., Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022; Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2021; Talving, Reference Talving2017).

Three important gaps in the literature could explain the mixed findings. First, we lack a theory about the evolution of the effect of austerity measures on electoral preferences over time. The current conclusions are essentially driven by the availability of data and few studies differentiate effects by time (but see Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Kemmerling and Sattler2015). Second, we lack an estimation of the causal effect of austerity measures on electoral preferences (but see attempts by Arias & Stasavage, Reference Arias and Stasavage2019, and Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Kemmerling and Sattler2015). Here, the main difficulty is isolating the effect of fiscal consolidation from other relevant political and economic events. The problem is acknowledged in the literature, but not really addressed. Third, the literature is too focused on the overall effect of austerity on electoral preferences and does not give enough attention to how different categories of voters react. This is particularly important since governments have implemented austerity measures in ways that shelter their own voters (Walter, Reference Walter2016).Footnote 1

This study addresses these gaps. First, it theorizes that the effect of austerity measures on electoral preferences is not immediate, but takes time to emerge, as voters find out about the consequences of fiscal consolidation via the media. To test this theory and the diffusion mechanism, the study uses original survey data collected immediately before and after the announcement of austerity measures in Romania and a very rich corpus of daily media coverage data spanning a six‐month period. Second, the study is able to estimate the immediate causal effect of the announcement of austerity measures on electoral preferences. Specifically, it takes advantage of a natural experiment: the fact that the announcement took place while a survey was in the field (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó‐Gimeno and Hernández2020). Third, it investigates how different categories of voters (government supporters vs. others) react to austerity measures.

Employing fine‐grained survey data, causal inference with observational data techniques, and multiple robustness, sensitivity and effect heterogeneity tests, this study confirms not only that austerity has an overall negative impact on support for the incumbent party, but that many former government supporters abandon their party. Romania provides the necessary data to examine the effect of austerity on electoral preferences, but these findings are relevant to other Central and Eastern European contexts and to Western Europe.

The effects of austerity measures on electoral preferences: Immediate or gradual?

The dominant (but contested) view in the literature is that austerity is not electorally consequential (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Favero and Giavazzi2019). Nonetheless, I expect austerity to have a negative impact on incumbent support. Why should austerity hurt the incumbents? Electoral punishment is consistent with retrospective voting (Healy & Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2013). Essentially, voters could perceive fiscal consolidation measures as a signal about the government's lack of competence and decide to punish the incumbent. Moreover, austerity could negatively impact people's incomes or harm overall economic growth, leading voters to sanction the incumbents.

Although some recent scholarship points to elite framing to explain why austerity would not hurt incumbents (Barnes & Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2018; Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021), these studies only look at economic preferences and not at voting behaviour. The role of elite framing remains to be investigated, but we note that, in bad economic times, partisan cues are less relevant for voting behaviour (Stanig, Reference Stanig2013; De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Tilley2018).

It is telling that the studies that find no negative effects of austerity measures on electoral preferences are all based on aggregate‐level analyses (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Perotti, Tavares, Obstfeld and Eichengreen1998, Reference Alesina, Carloni and Lecce2012; Arias & Stasavage, Reference Arias and Stasavage2019). Such analyses have limited power to offer insights about “the underlying mechanisms and the motivations of voter behaviour” (Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2023, p. 7) and are vulnerable to the ecological fallacy.

Recent experimental work by Hubscher et al. (Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2021, Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2023) and work using more fine‐grained observational data (Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Kemmerling and Sattler2015) find a negative effect of austerity on incumbent support. However, we lack clear expectations about the immediate effect of austerity measures on electoral intentions versus their longer‐term impact. Some studies consider the (usually long) periods (4 to 5 years) between elections (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Perotti, Tavares, Obstfeld and Eichengreen1998, Reference Alesina, Carloni and Lecce2012; Talving, Reference Talving2017; Arias & Stasavage, Reference Arias and Stasavage2019), others analyse the annual connection between government popularity and austerity (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Perotti, Tavares, Obstfeld and Eichengreen1998; Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Kemmerling and Sattler2015) and still others employ survey experiments to uncover the causal effect of austerity (Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2021, Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2023).

There are good reasons to expect that the effect of austerity measures will vary over time. Although a high‐impact event, the introduction of austerity measures cannot compare with a terrorist attack. For the latter, the information diffusion is almost instantaneous, and the impact on political attitudes and electoral preferences is immediate (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó‐Gimeno and Hernández2020). For other types of events, including the announcement of austerity, it should take time for an effect to emerge (for a similar argument, see Bridgman et al., Reference Bridgman, Ciobanu, Erlich, Bohonos and Ross2021). First, given that media coverage influences economic perceptions (De Boef & Kellstedt, Reference De Boef and Kellstedt2004), the media is likely to play a fundamental role in informing citizens and interpreting economic news. However, updating economic expectations cannot happen overnight (Doms & Morin, Reference Doms and Morin2004) but should proceed gradually. Second, voters have political predispositions and electoral histories. In the absence of world‐shattering events, they should not be expected to instantaneously switch their support. Third, the announcement of the measures is not the same as their implementation: one could argue that risk‐averse voters prefer to see the measures enacted before reacting electorally. Accordingly, I posit that the effect of the announcement of austerity measures on electoral intentions should not be immediate, but gradual (H1).

While the effect should not be observed right away, voters should still penalize the government for austerity. My argument builds on the interplay between media coverage, public opinion and voting behaviour. We know that media coverage of the economy influences economic perceptions (De Boef & Kellstedt, Reference De Boef and Kellstedt2004). As discussed by Soroka et al. (Reference Soroka, Stecula and Wlezien2015, pp. 458–459), people are most likely to update their economic perceptions when there are high volumes of news, which tends to happen when the economy is doing badly. In bad times, economic perceptions are less influenced by ideology and partisan affiliations (Stanig, Reference Stanig2013) and even partisans of the governing party update their evaluations to reflect the real economic situation (De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Tilley2018). This reduces the influence of partisan cues and opens up the possibility that the media plays an enhanced role in shaping economic perceptions and priming these perceptions when it comes time to vote (Sanders, Reference Sanders2000). It is plausible that the same dynamic occurs following an announcement of austerity measures. Indeed, there is evidence that media coverage shapes perceptions of such measures (Barnes & Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2018). These media‐shaped perceptions should impact electoral preferences (Shah et al., Reference Shah, Watts, Domke, Fan and Fibison1999; Sanders, Reference Sanders2000), resulting in the erosion of incumbent support. However, the effect on voting behaviour should not be immediate since even during high news periods, it usually takes months for citizens to update their economic expectations (Doms & Morin, Reference Doms and Morin2004). Instead, the effect will accumulate over time.

How do different types of voters react to austerity?

To explain their null findings, Arias & Stasavage (Reference Arias and Stasavage2019, p. 1521) refer to the potential explanatory role of “partisan allegiances”: voters' electoral predispositions are too strong for electoral sanctioning to emerge. However, this thesis has not really been tested, and the literature has not paid sufficient attention to the behaviour of different voters. In order for austerity to negatively impact support for the incumbent, past government supporters should decide either to vote for another party (defection) or not to vote at all (demobilization). These expectations are consistent with work suggesting that austerity is detrimental to incumbents (Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Kemmerling and Sattler2015) and reduces turnout (Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2023).

In times of crisis, voters' evaluations of the economy are less subject to the biasing effects of ideology and partisan affiliation (Stanig, Reference Stanig2013), and this facilitates electoral punishment of the incumbent. This is the case in mature democracies and young democracies alike. The decline of partisanship (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004) and increasingly high volatility in advanced democracies as well as consistently high levels of electoral volatility (Emanuele et al., Reference Emanuele, Chiaramonte and Soare2020) and a lack of deep political identities (Tufiș, Reference Tufiș, Comșa, Gheorghitǎ and Tufiș2010) in less consolidated ones can exacerbate electoral punishment. Recent work shows that ideology also plays a reduced role in explaining voters' attitudes towards austerity (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021). Therefore, I expect voters to be less likely to view austerity through an ideological lens and more likely to rely on unbiased evaluations of the government's performance. This is consistent with the retrospective voting (Healy & Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2013), with the austerity measures being perceived as a signal of governmental incompetence and thus triggering sanctioning. If austerity matters electorally, the government's past supporters will respond electorally by punishing the incumbents (H2).

It is also important to consider the effect of austerity on intended turnout and having a vote intention. Economic voting research shows that voters, irrespective of their partisan leanings, update their economic beliefs to reflect real economic changes (De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Tilley2018). In the case of government supporters, this may result in demobilization rather than defection. Confronted with highly negative information about the economic performance of their favourite party, these voters could decide to abstain rather than vote for a different party. Accordingly, I hypothesize that, in the wake of austerity measures, the incumbent's past supporters will be less likely to say that they would vote if an election were imminent (H3). If they do intend to vote, they may be less likely to know which party they would support. This prediction is a variation of the spiral of silence theory (Noelle‐Neumann, Reference Noelle‐Neumann1974): as voters perceive a public opinion climate adverse to their party, they could activate this defence mechanism of not stating a voting preference. In a context where the dominant opinion towards their party is negative, these voters may be reluctant to express a preference that is at odds with public opinion. This leads to the hypothesis that, in reaction to austerity, the incumbent's past supporters will be less likely to state a vote intention (H4).

The previous three hypotheses explore the heterogenous effects of austerity, depending on whether or not the voter had voted for the incumbent. A related question is whether those who are most directly affected by the measures are more likely to punish the incumbent. Spending cuts typically disproportionately hurt public sector employees, the unemployed and pensioners, but is this differentiation politically consequential? The economic voting literature generally finds that retrospective voting is influenced not by voters' personal situations but by their perceptions of the national economy (Duch & Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008). Moreover, Bansak et al. (Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021) find that people's austerity evaluations are not driven by economic self‐interest. However, in the case of those most affected, austerity measures could be considered personal economic shocks (Margalit, Reference Margalit2019). Such shocks have been shown to negatively impact incumbent support (Tilley et al., Reference Tilley, Neundorf and Hobolt2018). Therefore, if people react egotropically to austerity, those most directly affected by austerity will be more apt to punish the incumbent than those less affected (H5).

The Romanian case

To test these hypotheses, I leverage the availability of fine‐grained Romanian survey data. The 2008 crisis hit Romania hard. In 2009, as reported by Eurostat, the GDP contracted by 6.6 per cent (compared to a growth rate of 7.3 per cent in 2008), the budget deficit was 9 per cent of GDP (5.7 per cent in 2008), while the unemployment rate increased to 6.9 per cent, up from 5.8 per cent in 2008. An economic programme supported by a 12.95‐billion Euro loan under a 2‐year stand‐by arrangement was agreed upon with the IMF in March 2009. However, the IMF agreement and some limited budgetary cuts did little to stabilize the economy. On 6 May 2010, the PresidentFootnote 2 announced the reduction of all pensions, unemployment benefits and other social welfare programmes (such as childcare benefits) by 15 per cent and a 25 per cent cut in public sector wages. When the Constitutional Court ruled the proposed pension cut unconstitutional on 25 June 2010, the government reacted by increasing the VAT from 19 per cent to 24 per cent starting 1 July 2010. Other than the pension cut, all other austerity measures announced on 6 May were implemented. Online Appendix A.1 analyses the main austerity events and discusses the topics the media associated with the measures. An automated text (key‐word‐in‐context) analysis of a comprehensive media corpus (see online Appendix A.3 for details) shows that the 7480 media mentions of austerity/budgetary cuts in the post‐announcement period (7 May–5 July 2010) centred on two main topics: (1) the actions of the government (47.4 per cent of all austerity mentions), the PDL, President Bǎsescu, the IMF, and Parliament – the political and institutional dimension; and (2) the effects of the measures on wages (39.3 per cent of all austerity mentions), public sector employees (32.5 per cent), pensions/pensioners (33.5 per cent) and the economy (16.2 per cent) – the economic and social dimension. This informational environment created the conditions for voters to assess the actions of the decision‐makers, understand the impact of the measures and update voting behaviour.

The economic contraction continued in 2010: the GDP lost another 1.6 per cent and the unemployment rate rose to 7.3 per cent. Not surprisingly, Romanians were pessimistic about the country's economy. According to the European Commission's consumer confidence index, the difference between those who had a positive versus a negative opinion about the general economic situation of the country in the next 12 months was fully 64.1 points in June 2010. The opposition parties formed a pre‐electoral coalition in 2011, government MPs defected, and a no‐confidence motion was adopted in April 2012. The centre‐right PDL lost the 2012 legislative elections with only 16.7 per cent of votes, after obtaining 32.4 per cent in 2008.

The paper's findings have the potential to apply to other settings in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and beyond. First, Romania is not the only CEE country that implemented austerity measures in the 2008–2010 period: six of the eight CEE countries examined by Walter (Reference Walter2016) opted for measures that involved cuts in public sector wages and employment and/or spending reductions.Footnote 3 Second, with the exception of Hungary before April 2010, all of the CEE countries that adopted austerity measures were ruled by centre‐right and right‐wing governments (Walter, Reference Walter2016). In addition, an IMF report (IMF, 2015) finds that eight CEE countries (Romania, Lithuania, Estonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Latvia, Croatia, Hungary, and Ukraine) implemented large fiscal adjustments (greater than 3 per cent of potential GDP) in the 2008–2014 period and the average size of the fiscal adjustments in CEE was on a par with those implemented in Western Europe. The Romanian adjustment was not exceptional.Footnote 4 As Ortiz & Cummins (Reference Ortiz and Cummins2013) show, based on 2010–2013 IMF reports for 174 countries, austerity measures were globally widespread: 98 countries implemented wage cuts/caps, including the salaries of public sector workers; 80 countries rationalized and narrowed the scope of safety nets; 86 countries opted for pension reforms; and 94 countries increased or broadened the scope of consumption taxes, such as the VAT. These measures, which were key in Romania's austerity programme, were thus present in many other countries. Given recent work (Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2021) showing that austerity affected incumbent support in five Western European countries (Spain, Portugal, Italy, the UK and Germany), the results are likely to generalize beyond CEE.

More importantly, based on a time‐series analysis of aggregate data for 15 European countries (including Romania) for the 2005–2015 period, Bojar et al. (Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022) show that the announcement of austerity measures has a negative impact on vote intentions for the prime minister's party. These results are robust to different time windows after the austerity announcement (3, 6 or 12 months) and the effect, defined by the authors as “immediate”, is “augmented by the long‐run multiplier during the intervention window” (Bojar et al., Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022, p. 189). Consistent with my argument and demonstrating its generalizability, Bojar et al. (Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022) find that the announcement of austerity affects the incumbent's electoral support and that the electoral punishment varies over time. These findings fit nicely with the scholarship documenting the electoral risks of austerity (Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2021; Talving, Reference Talving2017) and are aligned with the idea that ideology (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021) and partisanship (Stanig, Reference Stanig2013) have limited effects on voters' reactions to austerity or economic downturns. To go one step further, I employed Bojar et al.'s (Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022) replication package and followed their estimation strategy to determine the effect of the austerity announcement on vote intention for the prime minister's party, again for the 2005–2015 period that covers the Great Recession. For each of the 15 European countries, I performed a time series analysis to estimate the short‐term effect of the austerity announcement, using 3‐month and 12‐month time windows around the announcement. The results (Figure A.4, online Appendix A.4 in the online appendix) indicate that the coefficient associated with the announcement is negative for 13 of the 15 countries in the sample, confirming the electoral sanctioning of the incumbents following these events. These tests add further plausibility to my claim about the argument's generalizability.

The immediate effect of austerity on electoral preferences

Identification and estimation strategy

Causally identifying the effect of austerity on electoral preferences has proven challenging, given the difficulty of isolating these episodes from other events. Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina, Carloni and Lecce2012, p. 4) conclude that “beyond two years too much time may have elapsed to attribute reelection (or defeat) mainly to the fiscal adjustment”; Talving (Reference Talving2017, p. 576) discusses how data availability “may limit our ability to capture voters' immediate reaction to rigorous austerity programmes”; Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina, Favero and Giavazzi2019, p. 181) posit that “isolating the role of fiscal adjustments in any statistical analysis may be difficult”; finally, Bartels (Reference Bartels, Bartels and Bermeo2014, pp. 211–212) adds that the evidence he finds of voters punishing the incumbents for austerity during the Great Recession is “fragile” given data limitations. Survey experiments can partly alleviate these concerns (Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2021, Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2023), but questions remain about the plausibility of the experimental vignettes and the results' generalizability.

To address this problem and identify the immediate effect of austerity, I take advantage of the fact that the announcement of the measures took place while a nationally representative public opinion survey was in the field. The poll was conducted between 1 May and 12 May 2010 by “Avangarde”, one of Romania's leading polling institutes, as part of their regular tracking of Romanian political opinion (see online Appendix A.2 for survey information). Announced on the evening of 6 May, the measures fell exactly in the middle of the fieldwork. Following the logic of the Unexpected Event during Survey Design (UESD), the announcement can be considered a natural experiment (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó‐Gimeno and Hernández2020).

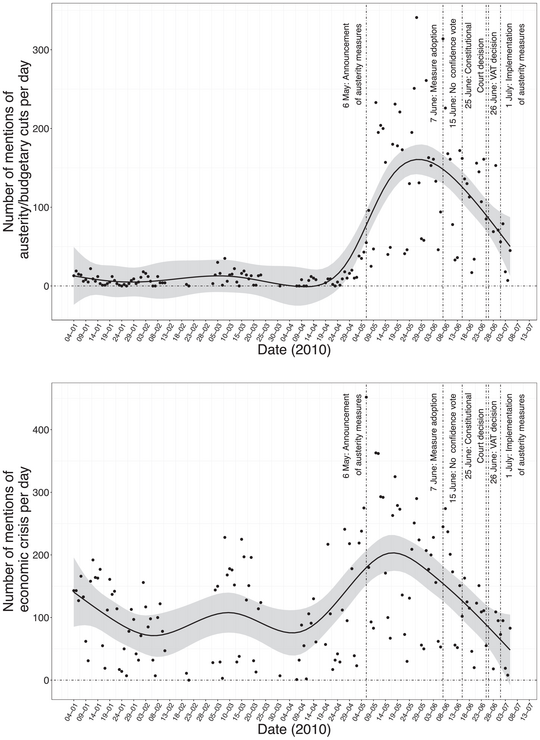

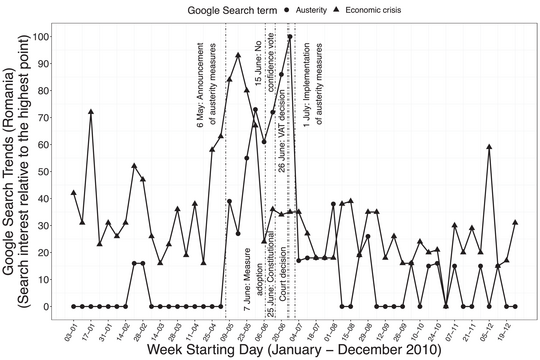

Given the narrow window (6 days before and after), I can confidently say that the announcement was the key event of the period and that no other high‐impact events occurred. This claim is supported by the media coverage (online Appendices A.1 and A.3), which confirms that the event can be considered unexpected: in the pre‐announcement period, the topic of austerity/budgetary cuts was barely present in the media (11 average mentions per day); after the event, the daily mean is 127 mentions (Figure 1). An examination of the evolution of Google searches for the term “austerity” in Romania reveals the same lack of interest among the public before 6 May and a jump in searches after this date (Figure 2). Moreover, the Avangarde survey did not ask anything related to austerity, confirming that the topic was not on the public's mind.

Figure 1. The media coverage of austerity/budgetary cuts and the economic crisis (January–July 2010).

Note: The smooth line (with the shaded area representing 95 per cent confidence intervals) is based on a general additive model with cubic splines.

Figure 2. Weekly Google searches of austerity and economic crisis (January–December 2010).

The UESD enables me to get at the immediate causal effect of the announcement by splitting the sample into those interviewed before the event (untreated) and those interviewed after 6 May (treated). I consider three dependent variables (all binary): vote intention for the main party of government (PDL), intention to turn out and having a vote preference if an election were to be held on the next Sunday. Equivalence‐based balance tests (Hartman & Hidalgo, Reference Hartman and Hidalgo2018) confirm that pre‐ and post‐announcement respondents are similar in terms of age, sex, education, ethnicity, religion, marital status, interest in politics, interest in political news, employment status, household size, being the main family breadwinner, having someone in the family with no stable employment and region of residence (online Appendix A.5). However, I find some small imbalances in terms of urban residence and region. Accordingly, I follow Muñoz et al. (Reference Muñoz, Falcó‐Gimeno and Hernández2020) and pre‐process my data with entropy balancing (Hainmueller, Reference Hainmueller2012), employing the variables that were used for the balance tests to calculate unit weights. I fit Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models with entropy balancing weights, regressing each dependent variable on the treatment variable (being interviewed before or after the announcement). The results remain substantively similar with and without statistical adjustments for imbalance.

Findings

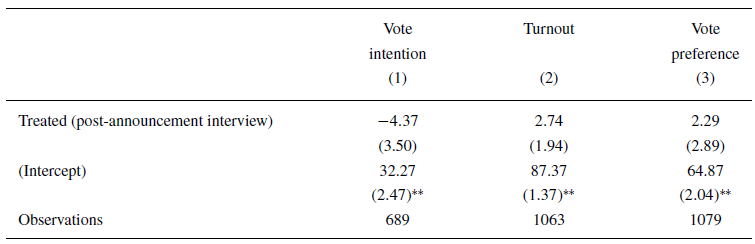

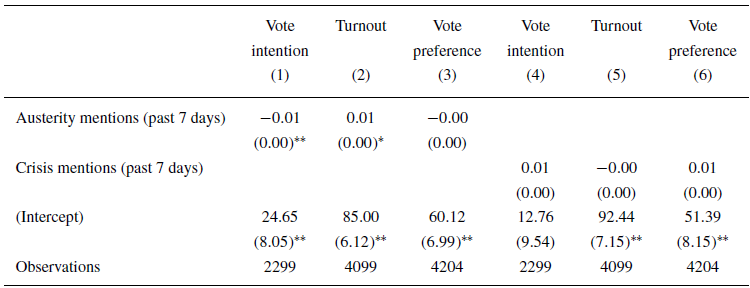

Table 1 presents the results of these estimations (see online Appendix A.6 for descriptive statistics). Although the incumbent loses an estimated 4.4 points in the immediate aftermath of the announcement (model 1), the coefficient is not different from zero. The same is true of the 2.8‐point increase in anticipated turnout (model 2) and the 2.3‐point jump in the probability of having a vote preference (model 3). To test the robustness of these findings, I used a regression discontinuity design, with windows of 3 and 5 days around the event and different polynomial orders (1–3). These estimations, further described in online Appendix A.7, also fail to detect a break. In short, there appears to be no immediate effect of austerity on electoral preferences.

Table 1. The immediate impact of the announcement on electoral preferences.

Note:

![]() $^{**}p<0.01$,

$^{**}p<0.01$,

![]() $^*p<0.05$. OLS models are estimated with entropy balancing weights. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

$^*p<0.05$. OLS models are estimated with entropy balancing weights. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

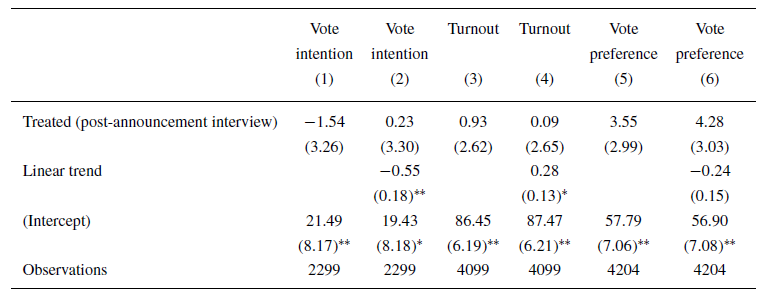

Does this mean that austerity has no electoral effect? According to my argument, it should take time for an effect to emerge. To test this claim, I leverage the fact that another major Romanian polling company, Compania de Cercetare Sociologică și Branding (CCSB), conducted three nationally representative surveys in May 2010, which I combine with the Avangarde poll. The surveys were conducted between 8 May and 20 May, 15 May and 18 May, and 26 May and 28 May, respectively (see online Appendices A.8 and A.9 for details). Now the treatment variable scores 0 for those interviewed before the announcement and 1 afterwards. Controls are included for age, sex, education, employment status, ethnicity, religion, urban residence, and region. A house effect dummy (CCSB vs. Avangarde) is also included, along with a linear trend variable coded 0 up to and including 6 May and then counting the number of days since the announcement.

As Table 2 shows, the treatment variables are not different from zero at conventional levels, another sign of non‐discontinuity. However, the linear trend variable reveals an interesting evolution: for every post‐event day, the incumbent party loses 0.55 percentage points, which, given the 22 post‐treatment days, results in a sizeable electoral punishment of 12.1 points in the voting probability (model 2). The effect is also present for intended turnout: a daily increase of 0.28 points means that, for the entire period, the probability of intended turnout increases by 6.2 points (model 4). However, the effect is not present for vote preference (model 6). Testing for non‐linearity (e.g., an exponential trend), I find that the effect is linear for voting intention, whereas there is some indication of non‐linearity for intended turnout (online Appendix A.10). Moreover, I analyse the evolution of the impact in the post‐announcement period. For vote intention, the substantive effects emerge starting 14 May, approximately 1 week after the announcement and they consolidate towards the final days included in the dataset (26–28 May). For instance, by 28 May, the probability of voting for the incumbent had dropped 12.6 points compared to the pre‐announcement period. The same dynamic is observed for anticipated turnout (online Appendix A.10).

Table 2. The impact of the announcement on electoral preferences (linear trend, May 2010).

Note:

![]() $^{**}p<0.01$,

$^{**}p<0.01$,

![]() $^*p<0.05$. OLS estimations. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

$^*p<0.05$. OLS estimations. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

My theory posits that this gradual effect is the consequence of the media shaping economic perceptions through information provision and interpretation (Barnes & Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2018; De Boef & Kellstedt, Reference De Boef and Kellstedt2004) and citizens progressively integrating these evaluations into their electoral calculations (Sanders, Reference Sanders2000). Higher volumes of news about austerity should influence economic perceptions (Doms & Morin, Reference Doms and Morin2004) and thereby impact electoral preferences. Lacking fine‐grained media consumption data for respondents, I test this argument by connecting aggregate daily media coverage data to individual electoral preferences: Using a rich corpus (approximately 30.2 million words, 1119 documents) of daily transcripts of all political news reported in the national media (four TV channels, 14 newspapers, and four radio stations) and of the main political TV talk‐shows (27 talk‐shows) from 4 January to 5 July 2010 (online Appendix A.3), I can approximate the informational environmentFootnote 5 surrounding a respondent by summing the number of austerity mentions in the 7 days preceding the interview date. This test presents suggestive evidence for the media mechanism, but more research, with better research designs, is necessary for conclusive, causal claims.

The findings are displayed in Table 3, with the same controls as in Table 2 (age, sex, education, employment status, ethnicity, religion, urban residence, region and a house effect dummy). For every media mention of austerity, the incumbent party loses an estimated 0.014 points (model 1). Given the mean of this variable (812), this translates into an average loss of 11.4 points in the probability of voting for the incumbent. In the case of intended turnout, the effect is 0.008 points, which translates into an estimated increase in intended turnout of 6.5 points (model 2).Footnote 6 However, there is no comparable effect on having a vote preference. This suggests that citizens respond to austerity, but their response is gradual and is associated with the increased media coverage of the topic. This fits well with the fact that coverage of austerity does not experience a sharp increase after the announcement on 6 May but increases gradually (online Appendix A.12). Also reassuring is that, when I use the number of mentions of the economic crisis for the past 7 days instead of austerity, the results are not different from zero at conventional levels (models 4–6).Footnote 7 When I include both the linear time trend and media coverage of austerity in Table 3, the time trend variable ceases to be statistically significant in both the vote intention and turnout models (online Appendix A.14), suggesting that the time trend is explained by the increasing number of media mentions and validating my argument. The results in Table 3 hold when I conduct a placebo test based on a different measure of austerity mentions (Table A.18, online Appendix A.14) and when I additionally account for any non‐linearities at the day level (Table A.19 in the online appendix).

Table 3. The impact of media coverage on electoral preferences (May 2010).

Note:

![]() $^{**}p<0.01$,

$^{**}p<0.01$,

![]() $^*p<0.05$. OLS estimations. Standard errors clustered at the date level are shown in parentheses.

$^*p<0.05$. OLS estimations. Standard errors clustered at the date level are shown in parentheses.

In sum, H1 is supported: the announcement of austerity does not have an immediate effect (measured 6 days post‐event – Table 1) on electoral preferences, but it does have a short‐term effectFootnote 8 (measured for a 3‐week post‐event period – Tables 2 and 3) that takes time to emerge and is associated with an increase in media coverage of the measures.Footnote 9

How do different types of voters react to fiscal consolidation?

Identification and estimation strategy

So far, I have been looking at the overall effect of the measures, but, as argued above, we would expect the incumbents' past supporters to be especially affected by the austerity announcement. The Avangarde survey does not have questions on respondents' electoral histories, so I cannot assess their immediate reaction to the measures. However, data from surveys conducted by CCSB throughout 2010 (online Appendix A.8) allow an examination of the behaviour of past government supporters shortly before and after the cuts.

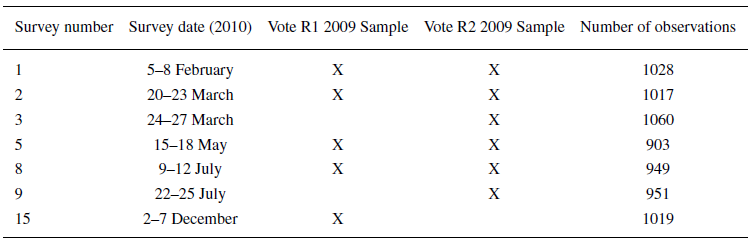

In order to analyse the electoral behaviour of government supporters, I employ reported vote in the first round of the 2009 presidential elections (scored 1 for those who voted for the PDL candidate, incumbent President Bǎsescu, and 0 for those who voted for another candidate or did not vote).Footnote 10 As a robustness check, I use reported votes in the second round of the same elections (scored 1 if the respondent voted for Bǎsescu and 0 otherwise). Table 4 displays information on the data collection periods and sample sizes for the seven nationally representative CCSB surveys that contain reported votes in the first or second round of 2009 elections, which will be employed for testing the hypotheses.

Table 4. Information on the 2010 surveys.

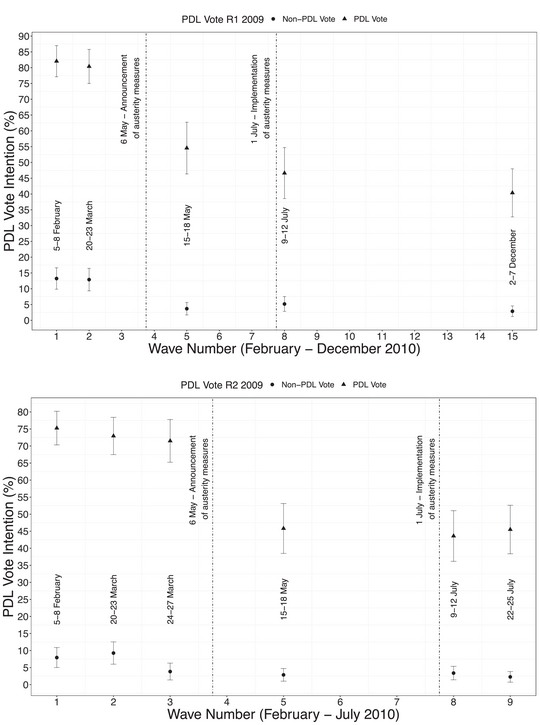

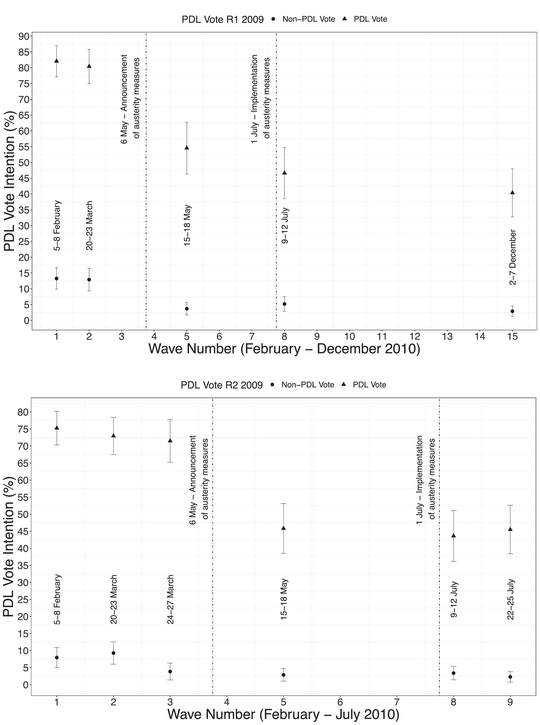

I estimate the impact of austerity using a DID estimation with time series cross‐sectional data. The key variable distinguishing between the pre‐ and post‐treatment periods is coded 0 for respondents surveyed before 6 May 2010 and 1 for those contacted after this date. Reported votes in the 2009 presidential elections differentiates the treated groups. I employ the same three binary dependent variables as for H1. The quantity of interest is the difference between past PDL supporters' electoral preferences pre‐ and post‐announcement. According to this approach, to build the counterfactual (comparison group) for past PDL voters in the post‐announcement period, we consider the pre–post announcement evolution of non‐PDL voters' behaviour and the baseline outcome for past PDL voters. For a proper comparison, we make the parallel trend assumption: for instance, for the vote intention outcome (Figure 3), we assume that, in the absence of the announcement, past PDL voters would have had a stable level of support for PDL, matching the behaviour of non‐2009 PDL voters (who show stable and, as expected, low levels of support for PDL) – a reasonable assumption; for the turnout (Figure C.1, online Appendix C.2) and vote preference (Figure C.2, online Appendix C.2) variables, we assume that, in the absence of the announcement, past PDL voters would have had a stable level of turnout/vote preference, mimicking the behaviour of non‐2009 PDL voters which is overwhelmingly stable – again, a reasonable assumption.

Figure 3. The evolution of the PDL vote intention for the treatment and control groups (H2).

Note: The point estimates are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Binary‐dependent variables pose methodological challenges for the DID estimation (see online Appendix C for my detailed identification strategy and how I deal with inferential threats). To address these challenges, I use propensity score matching (nearest neighbour) to match observations pre‐ and post‐austerity measures and employ the matched observations to calculate the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) using a non‐parametric DID estimation with bootstrapped standard errors (Stuart et al., Reference Stuart, Huskamp, Duckworth, Simmons, Song, Chernew and Barry2014). For matching, I employ sex, age, education status, religion, ethnicity, type of community, region and whether the respondent was targeted by the measures (i.e., a public employee, unemployed or a pensioner). Descriptive statistics are available in online Appendix A.9.

Findings

Main results

The question is whether, after the announcement, past PDL voters abandoned their party, as H2 predicts. Figure 3 provides a graphical answer. The top panel is based on the vote in the first round of the 2009 elections, and the bottom panel is based on the second‐round vote.Footnote 11 It shows a steep drop in PDL vote intentions among the party's past voters and relatively stable (although very low) support among non‐PDL past voters.

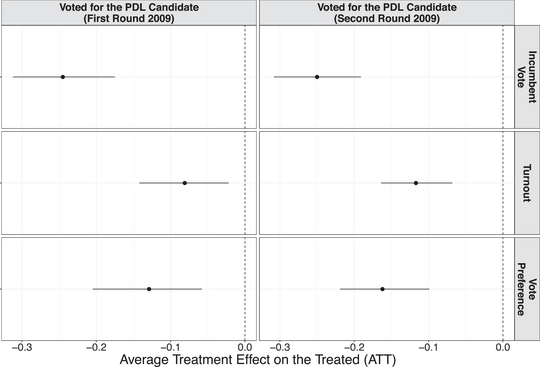

To answer this question more formally, I combine propensity score matchingFootnote 12 with non‐parametric DID. Here, I estimate the total impact of the austerity announcement on PDL vote intention, turnout and having a vote preference among 2009 PDL voters, by contrasting the electoral behaviour of this group of voters pre‐ versus post‐event (treatment) and by building an appropriate comparison group through DID, which allows me to show whether austerity triggered the defection and demobilization of past PDL voters. There is strong support for H2.Footnote 13 The announcement of austerity measures has a strong impact on those who had voted for the PDL candidate in the first round of the 2009 presidential elections (Figure 4, left panel), causing a big drop in support for the PDL among those who had voted for incumbent President Bǎsescu: the difference was fully 25 points, with most of this difference (19 points) occurring between the 20–23 March and 15–18 May surveys (see full results in Table E.1 and Figure E.1 in online Appendix E). The finding is very similar for those who had voted for Bǎsescu in the 2009 presidential runoff elections (the right panel), with the announcement inducing a big drop (about 25 points) in vote intentions for the party in power among these voters, whether we look at the period as a whole (Figure 4) or just compare the 24–27 March and the 15–18 May surveys (Table E.1 and Figure E.1 in online Appendix E). Thus, voters who only a couple of months before had voted for the incumbent responded harshly to the measures. Work on economic voting has shown that, in times of crisis, voters are apt to abandon their electoral history and predispositions and punish the incumbents based on their perceived performance (Bartels, Reference Bartels, Bartels and Bermeo2014; Stanig, Reference Stanig2013). These results show that austerity triggers the same process.

Figure 4. The total impact of the austerity measures on electoral preferences (H2–H4).

Note: The point estimates are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Full results are given in Table E.1 (online Appendix E).

Figure 4 also displays the results for H3, which predicts that, following the austerity announcement, the incumbent's past supporters will be less likely to report that they intend to vote. The measures clearly had a negative effect on the intended turnout of those who had voted for the PDL in the first round of the 2009 elections. The effect was a 9‐point drop (according to both the two surveys conducted pre‐ and post‐announcement (Table E.1 and Figure E.2 in online Appendix E) and the surveys as a whole (Figure 4)), compared with the pre‐announcement period. The difference is even bigger when we look at those who supported the PDL candidate in the run‐off of the last presidential elections (14 points based on a comparison of the 24–27 March and 15–18 May surveys (Table E.1 and Figure E.2 in online Appendix E) or 12 points based on the surveys as a whole (Figure 4)). Thus, hypothesis H3 is clearly supported.

According to H4, after the announcement, the incumbent's past supporters will be less likely to have a vote preference if the parliamentary elections were to be held the next Sunday. Figure 4 provides strong support for H4. Following the announcement, those who voted for the PDL in the first round of the 2009 elections are 13 points and 16 points less likely than before the announcement to report having a vote preference (based on the surveys as a whole (Figure 4) and the two surveys conducted close to the announcement (Table E.1 and Figure E.3 in online Appendix E), respectively). The comparable figures for those who had voted for the PDL candidate in the second round of the same elections are very similar: 17 points (Figure 4) and 13 points (Table E.1 and Figure E.3 in online Appendix E), respectively.

In sum, faced with austerity measures, many erstwhile supporters turned against the incumbent party. Moreover, austerity served to demobilize many of the incumbent party's past supporters and left them undecided about how to vote.Footnote 14

Robustness checks and sensitivity analyses

To ensure that these findings are robust, I test how much confidence we should have in the parallel trend assumption, the key assumption behind the DID estimation. The assumption posits that, should the treatment not have happened, the control and the treatment groups would have continued on the same trend. Simply put, the effect should emerge after the announcement, not before. To test this, I use pairs of surveys in their chronological ordering to estimate how the effect size changes over time. I find that, for all three hypotheses, the expected effect appears only when comparing the two surveys conducted just before and after the announcement. We do not find anticipatory effects to undermine the assumption. These results, displayed in online Appendix E (Figures E.1– E.3), show that (1) the austerity announcement massively influences electoral preferences; (2) the adoption and implementation of the measures do not bring about additional substantive changes; (3) the announced spending cuts drive the impact and the VAT tax increase is inconsequential.

To address the potential problem that one particular survey is driving the results, I have systematically excluded each survey in turn and re‐estimated the total effects. As reported in online Appendix E, there are no significant changes in the coefficients, compared with those shown in Figure 4.

The results hold across further robustness checks. First, I estimate linear probability models (online Appendix F.1) instead of propensity score matching with the non‐parametric DID estimator. Second, I go beyond a binary definition of the treated groups (2009 PDL voters vs. other voters) and contrast the former PDL voters with the voters of other parties and non‐voters (online Appendix F.2). Third, I employ OLS estimations with entropy balancing weights (online Appendix F.3) and the inverse probability weighted DID estimator (Sant'Anna & Zhao, Reference Sant'Anna and Zhao2020) (online Appendix F.4).

Finally, with observational data, selection bias and omitted variable bias more generally are potential threats. Three sensitivity analyses alleviate these concerns. The first two analyses refer to the results based on matching and employ the solutions proposed by Rosenbaum (Reference Rosenbaum2010), Rosenbaum and Silber (Reference Rosenbaum and Silber2009), and by Blackwell (Reference Blackwell2014), while the third test is applied to the parametric results (online Appendix F.1) and uses the method proposed by Frank et al. (Reference Frank, Maroulis, Duong and Kelcey2013). Full details of all three tests are presented in online Appendix F.5 and indicate that the results for H2 are highly robust to unobserved confounders; the results for H3 are also robust, but they are more sensitive for H4 (particularly for the sample based on the 2009 first‐round vote).

Do the most affected voters react more strongly to austerity?

A total of 7.6 million Romanians (42 per cent of the country's adult population) were directly impacted by austerity, including 0.738 million unemployed persons (National Statistics Institute, April 2010), 5.495 million pensioners (Labor Ministry, June 2010), and 1.362 million public sector workers (National Statistics Institute, February 2010). H5 predicts that the impact of austerity on intended electoral behaviour would be greater on those who were most affected, on the assumption that egotropic concerns will dominate.

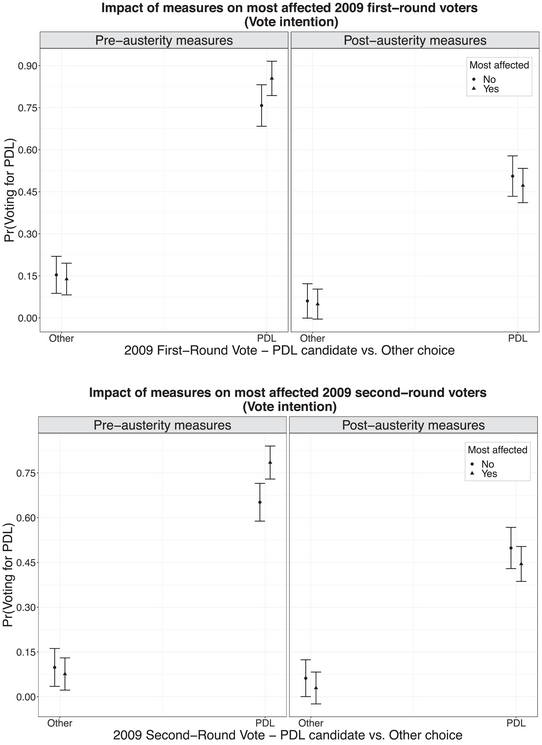

To test this hypothesis, I interact the DID coefficient (which, in a parametric setting, is an interaction between the 2009 vote and the period variable) with a “most affected” variable (corresponding to public‐sector employees, the unemployed, and pensioners). The resulting predicted probabilities plots are presented in Figure 5 (see online Appendix G.1 for the estimation). There are no statistically significant differences between the most and less affected 2009 PDL voters: they are equally likely to punish the incumbents. Even in a context of austerity, there does not appear to be an egotropic reaction.Footnote 15 There is no evidence to reject the null hypothesis for H5.Footnote 16 These results are consistent with the finding that attitudes towards austerity are not determined by people's economic interests (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021). No heterogeneity is observed for the other two dependent variables, either (online Appendix G.1). Moreover, two additional tests, conducted using the respondent's county unemployment rate and income, do not indicate any heterogeneity for any of the outcomes (online Appendices G.3 and G.4).

Figure 5. Effect heterogeneity tests (H5).

Note: The point estimates are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. The other variables are kept at their means (continuous variables) or reference (categorical variables) levels. The plots use Models 1 and 2 from online Appendix G.1.

Conclusions

This article has sought to answer an important, but unresolved question: Does austerity influence incumbent support? After showing that the literature struggles with theorizing the evolution of austerity's electoral effect over time, estimating the causal effect of fiscal consolidations, and analysing how different voters are affected by these measures, I set out to address these gaps.

First, I theorized that the effect of the austerity announcement on electoral intentions should not be immediate, but gradual. As the media covers the austerity measures and thus shapes their economic perceptions, voters are likely to update their electoral preferences; however, this process takes time, even in the case of high‐impact events that send clear signals to the voters about the government's competence. I leverage the availability of a survey that was in the field when austerity measures were announced in Romania in May 2010, combined with additional survey data collected shortly after the announcement and with comprehensive daily media coverage, to analyse how the electoral effect evolved over time and to test the mechanism of information diffusion via the media. I find that austerity does not have an immediate impact on incumbent support, intended turnout in the next election or expressing a vote preference, but instead there is a gradual effect on incumbent support and turnout (H1). This effect is associated with increased media attention to the cuts. Using the Romanian case, I thus find support for the thesis that austerity matters for electoral support (Bojar et al., Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022; Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2021; Talving, Reference Talving2017). My findings partly contradict the dominant findings in the literature on the electoral impact of fiscal consolidation (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Perotti, Tavares, Obstfeld and Eichengreen1998, Reference Alesina, Carloni and Lecce2012; Arias & Stasavage, Reference Arias and Stasavage2019), but add the insight that the over‐time evolution of the effect needs to be considered. Austerity does not have an immediate effect on electoral preferences, but it can have consequences that take time to appear.

Second, the natural experiment setup allows me to estimate the immediate causal impact of austerity, thus providing a contribution to the literature that struggles to provide a convincing answer to whether fiscal consolidations affect incumbent support. Third, I employed survey data from Romania to explore how different voters react in the short term to austerity, focusing on two potential reactions: electoral defection and demobilization. The results indicate that voters are willing to punish the government for fiscal adjustments irrespective of their own electoral histories (H2) and whether or not they are among those most affected by the cuts (H5). The significant and negative effect for those who voted for the PDL candidate in 2009 testifies to the presence of electoral defection among voters when confronted with austerity. Contrary to what others have found (Lenz, Reference Lenz2012), in the case of austerity, voters can reject their party's policy leadership. The decline in anticipated turnout in the next parliamentary elections (H3) and in reporting a vote preference (H4) due to austerity is also observed for those who voted for the PDL candidate in the last presidential elections. These findings suggest that austerity has the potential to impact incumbent support through electoral demobilization as well as defections. Contrary to other findings (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Perotti, Tavares, Obstfeld and Eichengreen1998), but in line with more recent research (Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2021), spending cuts are very unpopular with voters. The adoption and implementation of the measures did not bring significant additional punishment.

I expect my argument about austerity's gradual negative impact on incumbent support to generalize to other democratic countries with active and relatively free media. Austerity measures were widespread after 2010 (Ortiz & Cummins, Reference Ortiz and Cummins2013) in both Central and Eastern Europe (Walter, Reference Walter2016) and Western Europe (Engler & Klein, Reference Engler and Klein2017). Recent work, using both observational and experimental data, demonstrates not only the electoral risks of austerity (Hubscher et al., Reference Hubscher, Sattler and Wagner2021; Talving, Reference Talving2017), but that austerity announcements during the Great Recession affected parties in power in 15 European countries (Bojar et al., Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022). Employing Bojar et al.'s (Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022) replication package, I find that the short‐term effect of the austerity announcement (measured with both 3‐month and 12‐month time windows around the announcement) on the prime minister's party support is negative for 13 out of the 15 countries, including Romania. The electoral risk of austerity is thus a broad phenomenon.

Nonetheless, how gradually the electoral punishment emerges will vary across contexts, so it is important to discuss at least three scope conditions to my argument related to (1) citizens' media consumption, (2) the media coverage of austerity and (3) the strength of partisanship. First, information diffusion depends on citizens' media consumption: the more voters follow the media, the faster they are likely to be informed about austerity's impact and to react electorally. Based on the 2008 wave of the European Social SurveyFootnote 17 (ESS) (which was administered right before the introduction of austerity measures in Europe), there is variation in the proportion of those who follow news, politics or current affairs on TV, radio or in newspapers or who use the Internet daily in the 29 countries surveyed (Figures A.5 and A.6, online Appendix A.4). This heterogeneity is expected to influence how fast voters turn against austerity's political backers, with slower reactions expected for countries like Cyprus, Greece and Bulgaria and swifter updating envisaged for Norway, Denmark and Estonia. Second, and relatedly, the volume of news could impact information diffusion and political reactions: the more coverage the media gives to austerity, the sooner the political consequences will emerge. Using Dow Jones Factiva for nine European countries (Romania, France, Germany, United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, Portugal, Ireland and Austria) for each year of the 2008–2012 period, I have calculated the proportion of articles mentioning austerity. Based on the media coverage of austerity (Figure A.7, online Appendix A.4), we can expect a faster electoral response in countries such as Portugal, Ireland or Spain and a slower one in Austria and Germany. Third, although citizens are less likely to rely on partisanship during economic downturns (Stanig, Reference Stanig2013), partisan identification could affect their reactions to austerity: those who feel closer to the governing party should take longer to update their voting behaviour. Thus, the electoral sanctioning should emerge faster in countries with lower levels of partisanship such as Latvia, Poland and Ireland. Based on the 2008 ESS wave, we can see (Figure A.8, online Appendix A.4) an important variation in terms of how many voters in each country feel closer to a party.

Based on these three dimensions, Romania could be considered an intermediate case in terms of how fast the electoral punishment for austerity will emerge: (1) the country is close to the European average for daily media use (Figures A.5–A.6, online Appendix A.4); (2) its Reference Tufiș, Comșa, Gheorghitǎ and Tufiș2010 score for media coverage of austerity was below the scores for Portugal, Ireland and Spain, but above those for France, Austria and Germany (Figure A.7, online Appendix A.4); and (3) on partisanship (Figure A.8, online Appendix A.4), Romania is again close to the European mean.

By leveraging multiple datasets, I show that austerity measures impact incumbent support and electoral preferences more broadly, by zooming in on the evolution of their impact over time, the role of media coverage and the electoral defection and demobilization of past incumbent supporters. To the literature affected by data quality and too focused on answering whether austerity matters electorally, I contribute a careful exploration of how austerity can influence electoral preferences. This approach could be an example of how to analyse austerity's electoral consequences. Austerity is one of the fundamental issues for governments, parties and voters alike, and, although this article is a step in the right direction, we need to do more to assess its ramifications.

Acknowledgements

I thank Elisabeth Gidengil for her comments on multiple drafts of the paper. My gratitude also goes to Leonardo Baccini, Aengus Bridgman, Aaron Erlich, Olivier Jacques, Dietlind Stolle, the EJPR anonymous reviewers and editors for their feedback. I thank Mirel Palada for making available the CCSB data. I also thank Vlad Ionas for access to the Avangarde survey. I am thankful to Oana Negrea and Alin Teodorescu for access to data on IMAS surveys. The paper benefited from the constructive engagement of the participants to the Fifth Leuven–Montreal Winter School on Elections (2019), McGill Political Science PhD Research Seminar and 13th ECPR General Conference (2019). I acknowledge financial support from the Government of Canada's Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council as a Vanier Scholar. All errors are my own.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Data S1

Data S2