Impact statement

Adolescent suicide remains one of the most urgent public health issues globally, with devastating consequences for families, schools and communities. Traditional approaches to understanding youth suicide risk have often focused on individual risk behaviors, like smoking or poor diet, in isolation. However, adolescents rarely engage in such behaviors separately. Instead, their habits often form interconnected patterns, known as health lifestyles, which reflect both their personal choices and the social environments they navigate.

Our study contributes to an emergent strand of research that identifies health lifestyle patterns encompassing both conventional behaviors, such as diet, physical activity and substance use, and newer risks – including problematic social media use and e-cigarette consumption. Using data on more than 6,000 adolescents from the 2022 Luxembourg HBSC survey, we identified distinct behavioral patterns closely linked to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Some adolescents showed particularly high risk when multiple vulnerabilities, such as poor diet, substance use and digital overuse, were combined in their daily lives.

These findings have practical implications. They suggest that public health programs and school-based interventions should move beyond targeting single behaviors. Instead, prevention strategies need to be multidimensional and reflect the complex realities of young people’s lives. Screening tools, health education programs and counseling services can be more effective when tailored to the specific behavior profiles we identified, whether characterized by high substance use, digital vulnerabilities or other emerging risks.

By illuminating how combinations of behaviors are associated with increased suicide risk, our research supports earlier identification of vulnerable youth and more holistic, targeted prevention strategies. This approach can help improve adolescent mental health and reduce the tragic toll of suicide on young people and their communities.

Introduction

Adolescent suicidal behavior is a critical public health issue and ranks among the leading causes of death among young people worldwide (Campisi et al., Reference Campisi, Carducci, Akseer, Zasowski, Szatmari and Bhutta2020). Although suicide among individuals aged 15–19 years accounts for a relatively small proportion of all suicides globally, it is the fourth leading cause of death in this age group, partly because deaths from natural causes are relatively uncommon during adolescence (World Health Organization, 2021). Beyond mortality, each suicide or suicide attempt can have far-reaching consequences for families, peers and communities (Andriessen et al., Reference Andriessen, Krysinska, Rickwood and Pirkis2020). Research suggests that adolescents who attempt suicide may experience enduring emotional and social difficulties even a decade later (Ligier et al., Reference Ligier, Kurzenne, Kabuth and Guillemin2021). Accordingly, public health authorities describe adolescent suicide as a pressing global burden and call for coordinated, multisectoral prevention strategies (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Park, Lee, Lee, Woo, Kwon, Kim, Koyanagi, Smith, Rahmati, Fond, Boyer, Kang, Lee, Oh and Yon2024). These concerns underscore the need to better understand the range of factors contributing to youth suicide risk, especially modifiable behaviors that can be targeted through early intervention.

Health behaviors are increasingly recognized as important determinants of adolescent mental health and suicidality. This relationship is grounded in socio-ecological and social determinants of health frameworks, which emphasize how individual behaviors interact with broader social and environmental contexts (DiClemente et al., Reference DiClemente, Brown and Davis2013). A growing body of research has demonstrated that substance use (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Hoven, Liu, Cohen, Fuller and Shaffer2004), physical inactivity (Michael et al., Reference Michael, Lowry, Merlo, Cooper, Hyde and McKeon2020), inadequate diet – including low fruit and vegetable intake or high consumption of sugary drinks (Shawon et al., Reference Shawon, Rouf, Jahan, Hossain, Mahmood, Gupta, Islam, Al Kibria and Islam2023) – and problematic social media use (Sedgwick et al., Reference Sedgwick, Epstein, Dutta and Ougrin2019) are each independently associated with suicide risks among adolescents.

Adolescence is a critical period in which health lifestyles take shape through experimentation, identity development and peer influence (Patton et al., Reference Patton, Sawyer, Santelli, Ross, Afifi, Allen, Arora, Azzopardi, Baldwin, Bonell, Kakuma, Kennedy, Mahon, McGovern, Mokdad, Patel, Petroni, Reavley, Taiwo, Waldfogel, Wickremarathne, Barroso, Bhutta, Fatusi, Mattoo, Diers, Fang, Ferguson, Ssewamala and Viner2016). During this stage, behaviors related to physical activity, diet, substance use and screen time are often adopted and can influence long-term mental health outcomes (Burdette et al., Reference Burdette, Needham, Taylor and Hill2017). Yet, adolescents rarely engage in these behaviors in isolation. Instead, they often adopt interconnected behavioral patterns that reflect broader health lifestyles. Health lifestyles are constellations of interrelated behaviors that co-occur and interact to shape health trajectories, influenced by both social structure (e.g., group norms and socioeconomic conditions) and individual agency (Mollborn et al., Reference Mollborn, Lawrence and Saint Onge2021). Lifestyle theory suggests that studying health behaviors in isolation can obscure interactions between behaviors and underestimate their cumulative impact on health (Cockerham, Reference Cockerham2005).

Much health behavior research has examined these domains individually, thereby missing how behaviors cluster in everyday life. At the same time, emerging behaviors, such as e-cigarette use and problematic social media engagement, have become increasingly prevalent and relevant, yet are rarely included in multidimensional lifestyle research on how these behaviors co-occur and how specific constellations relate to suicidality, offering a promising avenue for identifying adolescents at heightened risk. Person-centered approaches, such as latent class analysis (LCA), can uncover meaningful subgroups defined by shared behavioral patterns that variable-centered approaches may not detect.

The present study aims to address this gap by using LCA to identify distinct health lifestyle patterns among adolescents, including emerging behaviors, and assess their associations with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Methods

Study design

This study used data from the 2022 Luxembourg Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey, a cross-sectional international research project designed to examine adolescent health behaviors and their social determinants (HBSC survey, 2022). The HBSC survey aims to monitor trends in adolescent health, health behaviors, well-being and social environments using a standardized international protocol. HBSC provides nationally representative data collected with validated measures and covers both traditional and emerging health behaviors, including suicidality, making it well-suited for identifying multidimensional behavioral patterns. Data collection in Luxembourg took place between February 22 and June 1, 2022.

Sample

The HBSC Luxembourg survey employed a clustered sampling strategy, inviting all students enrolled in randomly selected school classes to participate. The sample included students from Cycle 4, première année (equivalent to US grade 5) through the final grades of both general and vocational secondary schools. Parents and students received written information about the study and consent forms, allowing them to participate voluntarily or decline. Additionally, teachers reminded students verbally of their right to withdraw at any time.

Data were collected using a paper-and-pencil questionnaire, self-administered in class during school hours and typically requiring 45–60 min to complete. The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into German and French following a rigorous translation–back-translation procedure.

A total of 802 school classes from 178 schools were drawn, and all 13,343 pupils in these classes were invited to participate in the survey. The 2022 survey included 8,538 adolescents aged 11–18 years, but only secondary-school students aged 13 years and older were asked about suicidal behavior, resulting in a final analytic sample of 6,187 participants.

Further details regarding the survey procedure, sampling and the examined population are available in the Luxembourg HBSC 2022 national report (“HBSC_2022_Methods Report.pdf,” n.d.).

Ethics approval

The HBSC 2022 survey received ethical approval from the Ethics Review Panel of the University of Luxembourg (ERP 21–013 HBSC 2022).

Description of study variables

Health lifestyle behavior: Seven variables were used to assess health lifestyle behaviors. Daily fruit and vegetable consumption was measured using two items, each on a seven-point scale ranging from “never” to “more than once daily.” Participants reported how often they usually ate fruits and vegetables each week. Adolescents who reported eating fruits or vegetables at least once a day were classified as daily consumers. For analysis, responses were dichotomized to reflect daily consumption, consistent with public health recommendations encouraging regular daily fruit and vegetable intake (Vereecken et al., Reference Vereecken, Pedersen, Ojala, Krølner, Dzielska, Ahluwalia, Giacchi and Kelly2015).

Physical activity was assessed by asking participants how many days in the past 7 days they had been physically active for at least 60 min per day. Responses were recorded on an eight-point scale, ranging from “0 days” to “7 days.” For analysis, adolescents were classified as meeting or not meeting the 7-day physical activity guideline (i.e., ≥60 min/day every day) (“WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour,” 2020).

Current use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes and alcohol consumption was assessed by asking participants how many days in the past 30 days they had engaged in each behavior. Responses were recorded on a seven-point scale, ranging from “never” to “30 days or more.” For analysis, each behavior was dichotomized into “yes” (reported use on at least 1 day) versus “no” (never) to capture current substance use (Charrier et al., Reference Charrier, van Dorsselaer, Canale, Baska, Kilibarda, Comoretto, Galeotti, Brown and Vieno2024).

Problematic social media use was assessed using the nine-item Social Media Disorder Scale, which evaluates addiction-like social media use over the past year (van den Eijnden et al., Reference van den Eijnden, Lemmens and Valkenburg2016). Participants responded to yes/no questions about behaviors such as preoccupation with social media, withdrawal symptoms, loss of interest in other activities, deception about usage and social conflicts due to social media use. A sum score was computed, with adolescents scoring six or more classified as problematic users, and those scoring five or less classified as nonproblematic users (Boer et al., Reference Boer, van den Eijnden, Finkenauer, Boniel-Nissim, Marino, Inchley, Cosma, Paakkari and Stevens2022).

Dependent variables: Suicidal behavior was measured using two items adapted from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (May and Klonsky, Reference May and Klonsky2011). Suicidal ideation was assessed using the question: “During the past 12 months, did you ever consider suicide?” with response options “yes” or “no.” Suicide attempts were evaluated with the question: “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” Response options included: “0 times,” “1 time,” “2 or 3 times,” “4 or 5 times” and “6 times or more.” For analysis, suicide attempts were dichotomized as “yes” (≥1 attempt) versus “no” (0 attempts).

Covariates: Participants provided information on age, migrant status, family structure, family affluence and school type. Migrant status was categorized as “nonimmigrant,” “parents immigrated” or “immigrated myself.” Family structure was classified based on household composition: “living with both parents,” “single parent,” “stepfamily” or “other family arrangements.” Family affluence was measured using the Family Affluence Scale III (FAS-III) (Torsheim et al., Reference Torsheim, Cavallo, Levin, Schnohr, Mazur, Niclasen and Currie2016). FAS scores were categorized into the lowest 20%, medium 60% and the highest 20% (Europe, 2016). School type was classified according to the Luxembourgish education system into two categories: “Enseignement Secondaire Général,” which provides a more applied and vocational track, and “Enseignement Secondaire Classique,” which follows a more academic and university-preparatory track.

Statistical analyses

Description of the sample: The distribution of each variable was assessed, and outliers, coding errors, missing data and multicollinearity were checked. Categorical variables were described using numbers and percentages.

Identification of health lifestyle behavior classes: We used LCA to identify distinct health lifestyle behavior classes among adolescents. This method permits identifying homogeneous unobserved (i.e., latent) subgroups in a heterogeneous population by grouping individuals who share similar patterns of responses across multiple observed variables (Weller et al., Reference Weller, Bowen and Faubert2020). Optimal number of classes was determined based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), entropy (0–1), the proportion of participants per class (>5% of the sample), average posterior probabilities of group membership for each latent class (>70%) and class interpretability (Nagin, Reference Nagin2009). Missing data were handled using the expectation–maximization algorithm implemented in the poLCA package, which estimates class membership probabilities based on all available item-level data, while excluding missing values from the likelihood computation (Linzer and Lewis, Reference Linzer and Lewis2011). The resulting classes were characterized by examining the proportion of participants with specific health lifestyle behaviors and sociodemographic characteristics within each class. We compared categorical variables across classes using chi-square tests.

Association between health lifestyle behavior classes and suicidal behaviors: We used hierarchical logistic regression models to assess the association between health lifestyle behavior classes and suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Random intercept models were specified to account for school class-level clustering. Model diagnostics included checks for multicollinearity, residual uniformity and normality of random effects; no major violations were detected. Model fit was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to determine the proportion of variance attributable to school-class level differences.

To assess the associations between health lifestyle behavior classes and suicidal ideation and suicide attempt, we first estimated unadjusted models. To account for potential confounding, we adjusted the models for age, sex, migrant status, family structure, family affluence and school type.

All statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.1.0) using the poLCA (Linzer and Lewis, Reference Linzer and Lewis2022) package for LCA and the lme4 (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker, Walker, RHB, Singmann, Dai, Scheipl, Grothendieck, Green, Fox, Bauer, Pavel, Tanaka and Jagan2025) package for multilevel logistic regression. Model results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

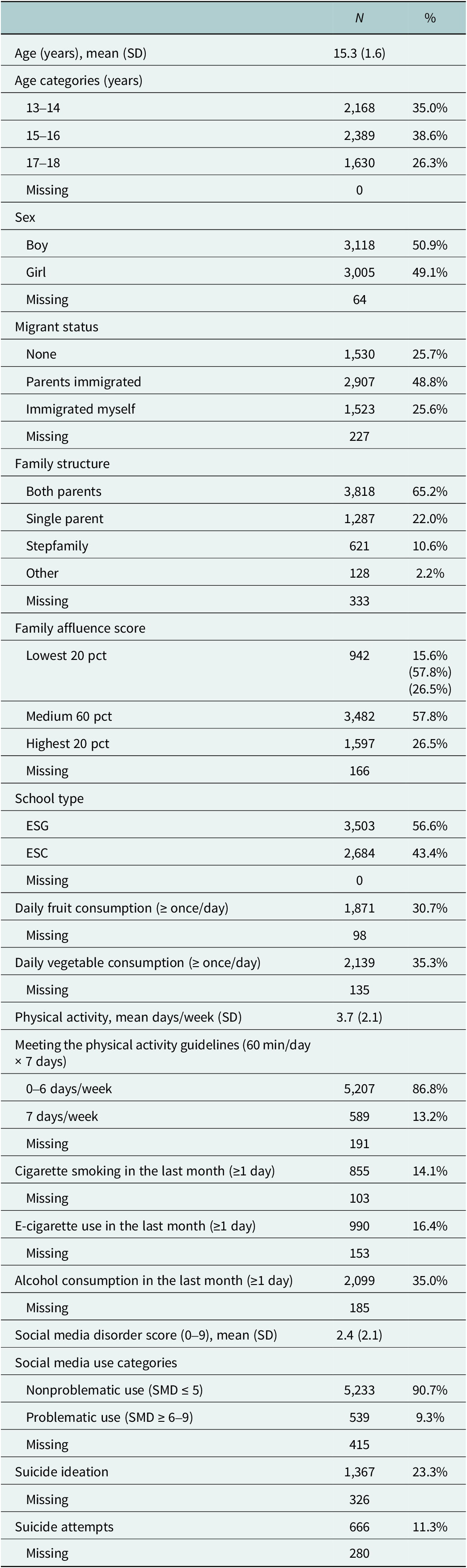

A total of 6,187 adolescents aged 13–18 years were included in the analyses. The characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of sociodemographic characteristics, health lifestyle behavior and suicidal behavior among adolescents

Abbreviations: ESG = Enseignement Secondaire Général (general secondary education); ESC = Enseignement Secondaire Classique (classical secondary education); SMD = Social Media Disorder scale.

Latent class identification and model fit

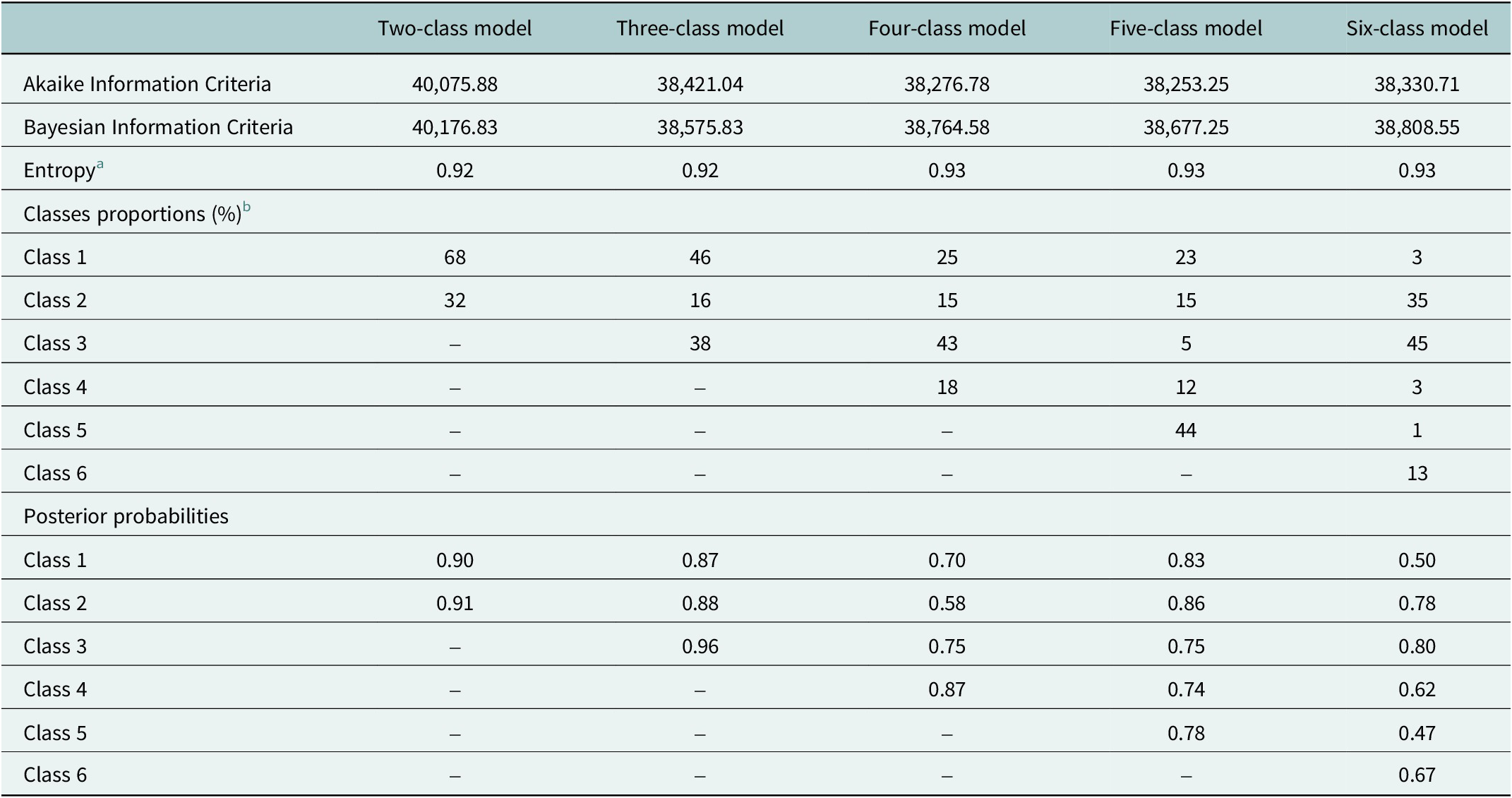

Descriptions of model-fit statistics, class proportions and posterior probabilities are reported in Table 2. Although the BIC was lowest for the three-class model, we selected the five-class solution based on a combination of statistical (e.g., lower AIC) and substantive interpretability criteria. The five-class model provided greater conceptual clarity by distinguishing between traditional substance use patterns and emerging digital risks, making it the most informative and theoretically relevant classification (Masyn, Reference Masyn and Little2013).

Table 2. Description of model-fit statistics, class proportions and posterior probabilities of the latent class analysis process

a Ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating more accurate definition of classes by the model.

b Proportions may not sum up to 100 due to rounding.

Latent class descriptions

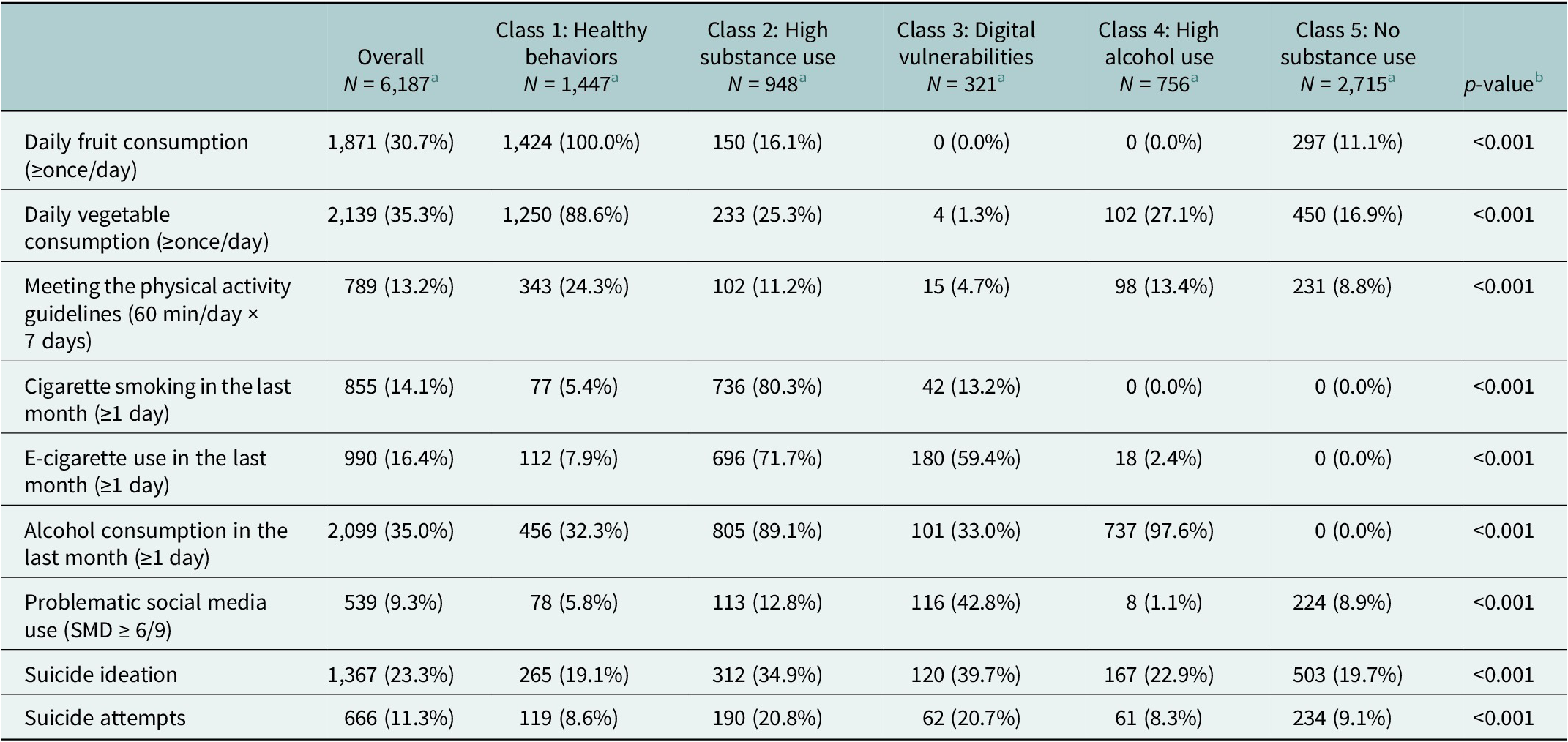

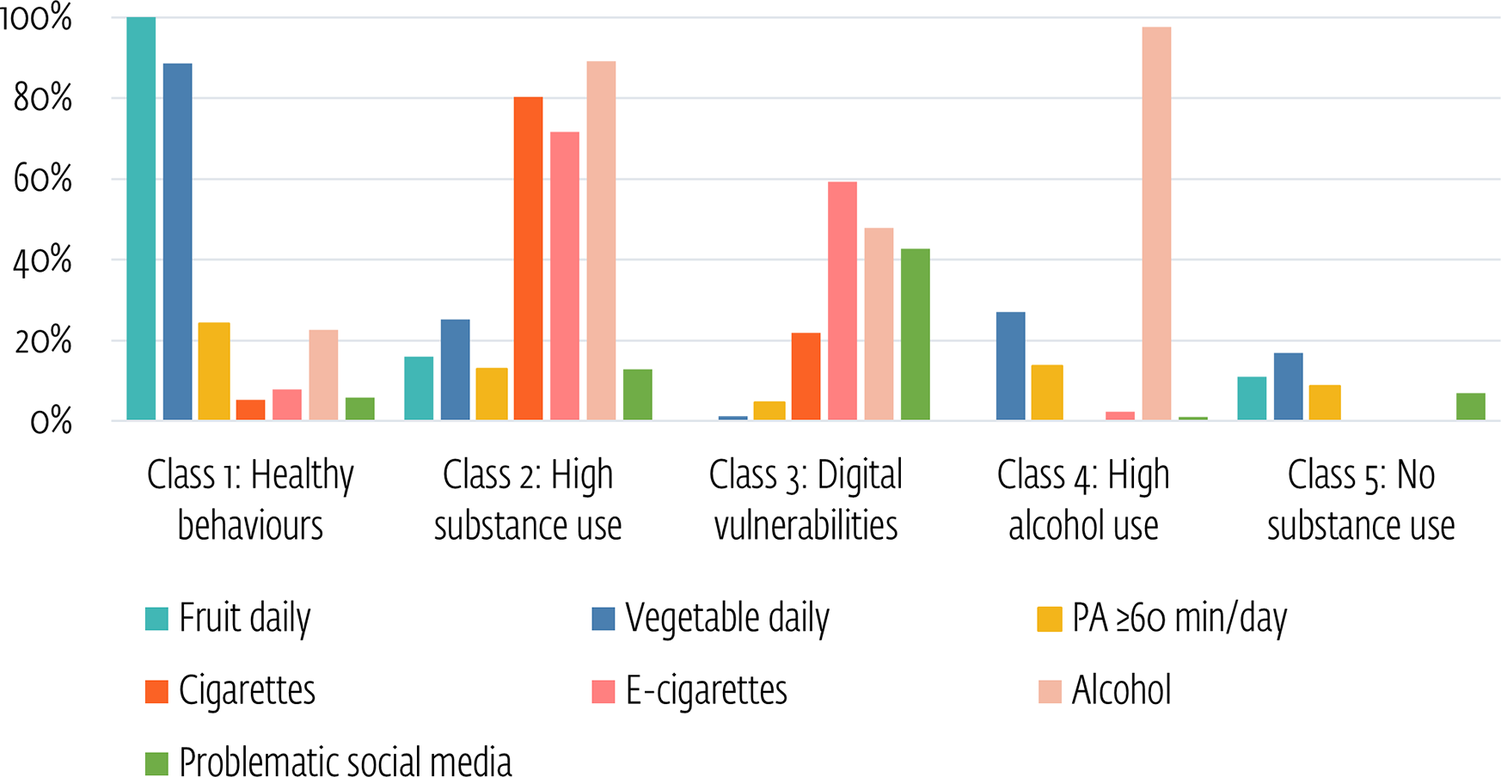

Table 3 presents the health lifestyle characteristics of adolescents across the five identified classes. On average, 30.7% and 35.3% of participants reported consuming fruits and vegetables daily, respectively. Physical activity for 7 days/week was reported by 13.2%. In relation to substance use, 14.1% reported cigarette smoking, 16.4% e-cigarette use and 35.0% reported alcohol consumption. Problematic social media use was reported by 9.3%. Figure 1 provides a visual comparison of the distribution of key health behaviors across the five latent classes.

Table 3. Health lifestyle characteristics of adolescents according to the identified classes

a n (%), bPearson’s chi-squared test.

Figure 1. Distribution of key health behaviors across the five latent classes. Note: PA = physical activity.

Class 1 (23.4% of participants), labeled “Healthy behaviors,” showed much higher than average daily fruit (100%) and vegetable (88.6%) consumption and physical activity (24.3%). Cigarette smoking (5.4%), e-cigarette use (7.9%) and problematic social media use (5.8%) were all lower than the sample averages.

Class 2 (15.3% of participants), labeled “High substance use,” showed lower daily fruit (16.1%) and vegetable (25.3%) consumption. Substance use was substantially higher: 80.3% reported cigarette smoking, 71.7% e-cigarette use and 89.1% alcohol consumption. Problematic social media use was higher than the sample average (12.8%).

Class 3 (5.2% of participants), labeled “Digital vulnerabilities,” had the lowest levels of health behaviors: no daily fruit consumption, 1.3% daily vegetable consumption and 4.7% meeting the recommended physical activity guidelines. E-cigarette use was elevated (59.4%), and problematic social media use was highest (42.8%).

Class 4 (12.2% of participants), labeled as “High alcohol use,” showed no daily fruit consumption and 27.1% daily vegetable consumption. Alcohol use was nearly universal (97.6%), the highest of all classes. In contrast, cigarette use (0.0%), e-cigarette use (2.4%) and problematic social media use (1.1%) were very low.

Class 5 (43.9% of participants), labeled “No substance use,” had below-average fruit (11.1%) and vegetable (16.9%) consumption and physical activity (8.8%). No adolescents in this class reported cigarette, e-cigarette or alcohol use.

Association between health lifestyle behavior classes and suicidal behaviors

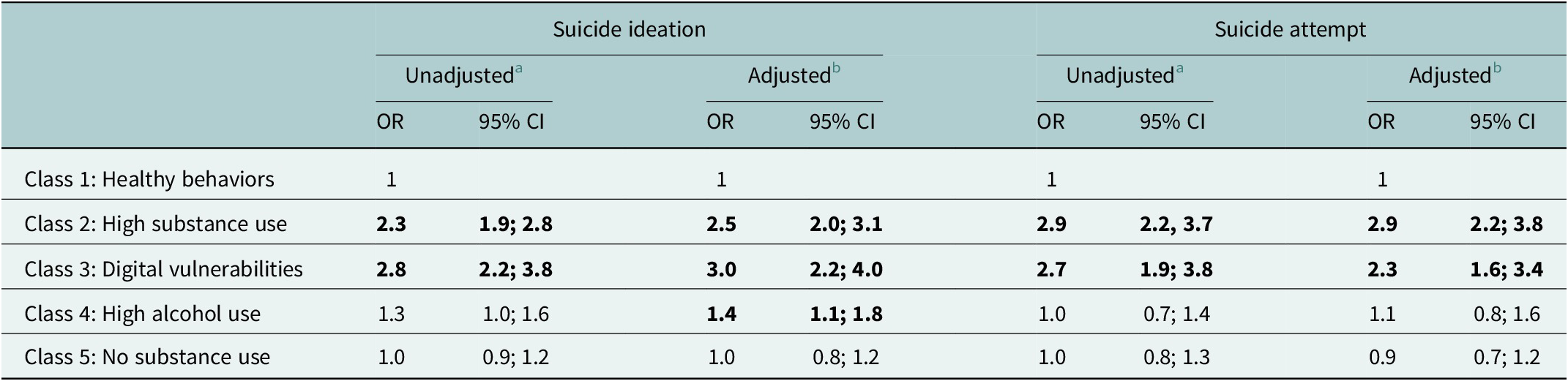

Results from logistic regression models assessing the association between health lifestyle behavior classes and suicidal behaviors are presented in Table 4. The ICCs for the models were low, with 2.2% of the variance in suicide attempt (ICC = 0.022) and 2.7% of the variance in suicidal ideation (ICC = 0.027) attributable to differences between school classes.

Table 4. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for suicide ideation and suicide attempt among adolescents according to lifestyle behaviors classes

a CIs were obtained using a hierarchical (level = school class) univariate binary logistic regression model.

b CIs were obtained using a hierarchical (level = school class) multivariate binary logistic regression model adjusting for age, sex, migrant status, family structure, family affluence and school type.

Compared to Class 1 “Healthy behaviors,” adolescents in Class 2 “High substance use” had significantly higher odds of reporting both suicidal ideation (OR = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.9;2.8) and suicide attempt (OR = 2.9, 95% CI: 2.2;3.7) in unadjusted models. These associations remained significant after adjustment for sociodemographic covariates (suicidal ideation: OR = 2.5, 95% CI: 2.0;3.1; suicide attempt: OR = 2.9, 95% CI: 2.2;3.8).

Adolescents in Class 3 “Digital vulnerabilities” also showed increased odds of both suicidal ideation (unadjusted OR = 2.8, 95% CI: 2.2;3.8; adjusted OR = 3.0, 95% CI: 2.2;4.0) and suicide attempt (unadjusted OR = 2.7, 95% CI: 1.9;3.8; adjusted OR = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.6;3.4) compared to Class 1.

Class 4 “High alcohol use” was associated with increased odds of suicidal ideation (unadjusted OR = 1.3, 95% CI: 1.0;1.6; adjusted OR = 1.4, 95% CI: 1.1;1.8), but no significant association was observed with suicide attempt (unadjusted OR = 1.0, 95% CI: 0.7;1.4; adjusted OR = 1.1, 95% CI: 0.8;1.6).

Finally, adolescents in Class 5 “No substance use” did not differ significantly from the Class 1 in terms of suicidal ideation (unadjusted OR = 1.0, 95% CI: 0.9;1.2; adjusted OR = 1.0, 95% CI: 0.8;1.2) nor suicide attempt (unadjusted OR = 1.0, 95% CI: 0.8;1.3; adjusted OR = 0.9, 95% CI: 0.7;1.2).

Discussion

Overview of identified health lifestyle classes and associations with suicidality

The present study aimed to identify distinct health lifestyle patterns among adolescents across traditional domains, including diet, physical activity, cigarette use, alcohol use, as well as emerging behaviors such as e-cigarette use and problematic social media use. The use of LCA reflects a person-centered approach that captures population heterogeneity in adolescents’ health lifestyles. Rather than isolating the effects of single behaviors, it identifies latent constellations of co-occurring habits, offering a more integrated view of how these patterns are associated with indicators of suicide risk (Scotto Rosato and Baer, Reference Scotto Rosato and Baer2012).

Five classes of adolescent health lifestyles were identified, each showing different associations with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Adolescents in Class 2, defined by concurrent cigarette, e-cigarette and alcohol use together with below-average daily fruit and vegetable consumption and low physical activity, had significantly higher odds of both suicidal ideation and suicide attempt compared to Class 1, characterized by overall health-promoting behaviors. Class 3, in which problematic social media use and e-cigarette consumption co-occurred with very low diet quality and physical inactivity, was also associated with increased suicidal ideation and attempt. Interestingly, Class 4, marked by the highest alcohol use and poor diet quality but minimal involvement in other risk behaviors, was associated with higher odds of suicidal ideation but not attempts. Finally, Class 5, defined by low diet quality and physical inactivity but no substance use, did not differ significantly from Class 1 in either suicidal ideation or suicide attempts.

Behavioral differentiation

Prior research has commonly identified clusters of healthy, unhealthy or mixed lifestyle behaviors among adolescents (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Romanelli and Lindsey2019; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Xue, Xia, Cui, Hu, Huang, Wan, Fang and Zhang2022). Our study extends this literature by incorporating e-cigarette use and problematic social media use, two increasingly prevalent behaviors rarely included in multidimensional lifestyle classifications, despite their growing relevance for adolescent health (Efa et al., Reference Efa, Lathief, Roder, Shi and Li2024). By capturing these additional behavioral domains, our findings offer a more comprehensive and contemporary depiction of adolescent health behavior patterns.

We also modeled cigarette use, e-cigarette use and alcohol consumption as separate indicators, rather than aggregating them into a single “substance use” domain. This distinction reflects differences in social norms, risk perceptions and engagement patterns across substances (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Andrews and Francis2017; East et al., Reference East, Hitchman, McNeill, Thrasher and Hammond2019; Moustafa et al., Reference Moustafa, Rodriguez, Mazur and Audrain-McGovern2021; Adekeye et al., Reference Adekeye, Boltz, Jao, Branstetter and Exten2025; Vu et al., Reference Vu, Sun, Hall, Connor, Thai, Gartner, Leung and Chan2025). The latent class structure supported this decision: Class 2 combined all three substances (polysubstance use), Class 4 was defined largely by high alcohol use, Class 3 captured a pattern in which e-cigarette use co-occurred with problematic social media engagement in the absence of other substances and Class 5 reflected the absence of substance use. These substance-differentiated patterns provided a basis for examining how broader lifestyle configurations related to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Patterns of risk across health lifestyle classes

The associations across classes suggested a gradient of suicide risk. Adolescents in Class 5, characterized by poor diet and low physical activity but no substance use, showed no increased risk relative to Class 1. Those in Class 4, marked by high alcohol use, exhibited elevated odds of suicidal ideation only. In contrast, adolescents in Classes 2 and 3, who combined similar nutritional and activity deficits with either polysubstance use (Class 2) or e-cigarette use and problematic social media engagement (Class 3), displayed substantially higher odds of both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

This pattern is consistent with synergistic, rather than purely independent, behavioral effects. Suicidality did not mirror the presence of individual behaviors considered separately. Most notably, adolescents in Class 5, who reported poor diet quality and physical inactivity, showed no elevation in suicide risk, despite engaging in multiple health-compromising behaviors. This suggests that these behaviors alone contribute minimally to vulnerability. In contrast, when similar dietary and activity patterns were combined with either polysubstance use (Class 2) or e-cigarette use paired with problematic social media engagement (Class 3), risk was substantially elevated for both ideation and attempts.

Overall, these findings indicate that vulnerability to suicidal outcomes depends on how behaviors co-occur within individuals. The progression from no elevation (Class 5) to ideation only (Class 4) to increased odds of both ideation and attempts (Classes 2 and 3) underscores the relevance of examining how behaviors cluster and interact when interpreting patterns of adolescent suicide risk.

Mechanistic pathways

The distinction observed between Class 4, associated with suicidal ideation only, and Classes 2 and 3, associated with both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, highlights that different combinations of health behaviors may be differentially related to ideation and to progression toward attempts, a distinction also emphasized in contemporary models of suicidal behavior (O’Connor and Kirtley, Reference O’Connor and Kirtley2018).

Increased vulnerability from cumulative risk behaviors: Adolescents in Class 2 had significantly higher odds of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts compared to the healthiest group (Class 1). Their combined engagement in cigarette smoking, e-cigarette use and alcohol consumption, alongside a small intake of fruits and vegetables, reflects a clustering of risk behaviors. This pattern aligns with the cumulative risk hypothesis, which posits that the presence of multiple co-occurring health-compromising behaviors amplifies vulnerability to poor mental health outcomes (Xiao and Lu, Reference Xiao and Lu2019).

One possible explanation for this association relates to the accumulated burden of behavioral risk factors on adolescents’ physical and emotional functioning. Poor nutrition may be associated with fatigue, low mood and reduced self-esteem (Gaddad et al., Reference Gaddad, Pemde, Basu, Dhankar and Rajendran2018; Khanna et al., Reference Khanna, Chattu and Aeri2019; Heslin and McNulty, Reference Heslin and McNulty2023), while substances such as alcohol and nicotine can interfere with neurochemical regulation and sleep, which may in turn affect emotional stability (Riehm et al., Reference Riehm, Rojo-Wissar, Feder, Mojtabai, Spira, Thrul and Crum2019; Phiri et al., Reference Phiri, Amelia, Muslih, Dlamini, Chung and Chang2023). This convergence of physical and neurochemical strain may erode adolescents’ emotional regulation and psychological resilience (Pisani et al., Reference Pisani, Wyman, Petrova, Schmeelk-Cone, Goldston, Xia and Gould2013), increasing vulnerability to depression, hopelessness and suicidality (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Wright, Hickman, Kipping, Smith, Pouliou and Heron2020).

Taken together, this pattern is consistent with a cumulative behavioral strain pathway, in which multiple co-occurring risk behaviors jointly undermine emotional and physiological resilience and elevate risk for both suicidal ideation and attempts.

Digital vulnerabilities and emerging behavioral risks: Adolescents in Class 3 had significantly higher odds of both suicidal ideation and suicide attempt compared to the healthiest group (Class 1). This class was characterized by a high proportion of adolescents who use e-cigarettes and have problematic social media use, alongside a very low proportion of those physically active and have a poor diet. Unlike Class 2, which involved a broader range of conventional health risk behaviors, Class 3 appears to reflect a more specific vulnerability profile tied to emerging behavioral and digital risks.

The co-occurrence of these behaviors may reflect emotional disengagement and social withdrawal, coupled with the absence of protective routines such as physical activity and healthy eating (Sina et al., Reference Sina, Boakye, Christianson, Ahrens and Hebestreit2022). Prior studies have linked e-cigarette use to depressive symptoms and suicidality, potentially through neurobiological pathways involving nicotine and its association with impulsivity and difficulties in emotion regulation (Javed et al., Reference Javed, Usmani, Sarfraz, Sarfraz, Hanif, Firoz, Baig, Sharath, Walia, Chérrez-Ojeda and Ahmed2022). Similarly, problematic social media use has been associated with sleep disturbance, social isolation, cyberbullying and negative social comparison, factors that may contribute to psychological distress in adolescents (Paakkari et al., Reference Paakkari, Tynjälä, Lahti, Ojala and Lyyra2021). These behavioral vulnerabilities may also interact dynamically over time: longitudinal research suggests that digital overuse can contribute to internalizing symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, which in turn increase the likelihood of subsequent e-cigarette use, reinforcing a cycle of emotional coping and behavioral disengagement (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Ao and Zhao2023). Adding to this vulnerability, evidence indicates that social media content, often disseminated by influencers and celebrities, frames e-cigarettes as fashionable, soothing and relatively harmless, thereby shaping adolescents’ beliefs and behaviors through increased curiosity, peer modeling and reduced risk perception (Adekeye et al., Reference Adekeye, Boltz, Jao, Branstetter and Exten2025).

Overall, this constellation is consistent with a digital-behavioral vulnerability pathway, marked by emotional disengagement, nicotine-related dysregulation and the absence of protective daily routines, producing elevated risk for both ideation and attempts.

High alcohol use in the absence of broader vulnerabilities: Adolescents in Class 4 also exhibited increased odds of suicidal ideation compared to Class 1, despite reporting relatively few co-occurring risk behaviors. This group was defined primarily by the highest prevalence of alcohol use across all classes, alongside low diet quality. Unlike Class 2 and Class 3, cigarette use, vaping and problematic digital engagement were notably absent, indicating a more targeted lifestyle risk pattern.

The presence of adolescents characterized primarily by high alcohol use is well-supported in the literature, highlighting a distinct and well-replicated pathway of vulnerability. Research analyses consistently identify this profile as robust, separate from nonusers, low-level users and polysubstance users (Göbel et al., Reference Göbel, Scheithauer, Bräker, Jonkman and Soellner2016). Frequent alcohol consumption has been linked to increased suicidal ideation (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kim, Lee, Cha, Lee, Lee, Seo, Lee, Lee, Lim and Choi2021). However, the progression from suicidal thoughts to attempts may require additional psychological or contextual factors, such as emotional dysregulation, reduced fear of self-harm or disconnection from protective environments (Klonsky et al., Reference Klonsky, Pachkowski, Shahnaz and May2021), which were not clearly reflected in the behavioral pattern observed in this group. The preserved physical activity and absence of digital or tobacco risks in this class, which are associated with better self-esteem and sleep (Gaddad et al., Reference Gaddad, Pemde, Basu, Dhankar and Rajendran2018; Phiri et al., Reference Phiri, Amelia, Muslih, Dlamini, Chung and Chang2023), may serve as partial protective buffers against escalation to suicide attempts.

This pattern, therefore, reflects an alcohol-specific vulnerability pathway in which ideation risk is elevated, but partial protective routines may prevent progression to attempts.

Perspectives for intervention and prevention

From a clinical and public health perspective, identifying distinct lifestyle configurations helps clarify how different constellations of behaviors relate to elevated vulnerability. Rather than treating health-compromising behaviors in isolation, these patterns provide a structured way to recognize combinations that may require more attentive follow-up. In particular, the markedly elevated odds of suicidal ideation and attempts observed in Classes 2 and 3 suggest that these constellations warrant heightened concern, whereas Classes 4 and 5 reflect more moderate and lower-risk patterns, respectively. These distinctions offer practical guidance for prioritizing prevention resources and help clinicians focus attention on adolescents most likely to benefit from targeted support.

Our findings highlight the importance of developing multifaceted suicide prevention strategies that consider adolescents’ lifestyle behavior patterns. The observed association between multiple co-occurring health behaviors and suicidal outcomes suggests that prevention programs may benefit from moving beyond single-behavior approaches. Traditionally, schools or public health initiatives have focused on specific targets, such as substance use, diet or physical inactivity, in isolation. However, adolescents in high-risk lifestyle classes (such as Class 2 or Class 3) may require more comprehensive strategies that address the constellation of behaviors they engage in, as well as the broader psychosocial contexts in which these behaviors occur (Webb et al. Reference Webb, Kauer, Ozer, Haller and Sanci2016; Simonton et al., Reference Simonton, Young and Johnson2018). While universal prevention remains essential given the prevalence of at least one risk behavior in this age group, the markedly elevated risks observed in Classes 2 and 3 suggest that complementary, cluster-specific approaches could more effectively identify and support adolescents at greatest risk. An integrated model combining universal prevention with targeted, class-based interventions, therefore, appears both efficient and clinically meaningful. Broad-based screening tools may help identify these risk patterns early by capturing co-occurring health behaviors and mental health concerns (Webb et al. Reference Webb, Kauer, Ozer, Haller and Sanci2016). For example, Webb et al. (Reference Webb, Kauer, Ozer, Haller and Sanci2016) advocate for broad screening in youth primary care, including diet, exercise, substance use and mood, given that most adolescents attend annual check-ups and report valuing discussions about health risks. In practical terms, adolescents who present one risk behavior might be assessed for additional co-occurring patterns. Pediatricians and school counselors could incorporate brief behavioral questionnaires covering physical activity, diet, substance use and screen habits into routine mental health check-ups to support early identification and appropriate referrals.

Such early detection can guide an integrated prevention framework in which universal mental health promotion is complemented by targeted, profile-based interventions for adolescents in higher-risk classes. Tailoring interventions to class-specific profiles may improve reach and effectiveness. Adolescents in Class 2 may benefit from comprehensive approaches addressing substance use, nutrition and physical activity, possibly via peer-led or family-based programs targeting impulsivity and social norms (Georgie et al., Reference Georgie, Sean, Deborah M, Matthew and Rona2016; Horigian et al., Reference Horigian, Anderson and Szapocznik2016). Incorporating components, such as group exercise, nutrition education and skills-based health promotion, may further support emotional well-being and reduce depressive symptoms (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Song, Ying, Zhang, Wu, Shan, Zha, Zhou, Xiao and Song2025). For adolescents in Class 3, interventions could explore the role of media literacy and balanced digital engagement, including promoting healthy online behaviors, facilitating both online and offline peer support networks, and offering structured digital tools such as gamified physical activity or app-based dietary challenges designed to foster healthier routines and support more balanced screen time patterns (Corepal et al., Reference Corepal, Best, O’Neill, Tully, Edwards, Jago, Miller, Kee and Hunter2018; Suleiman-Martos et al., Reference Suleiman-Martos, García-Lara, Martos-Cabrera, Albendín-García, Romero-Béjar, la Fuente GA and Gómez-Urquiza2021). Those in Class 4 may benefit from more targeted alcohol prevention efforts, such as motivational interviewing and school-based educational modules adapted for younger populations.

Limitations

This study is subject to certain limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes causal inference between lifestyle behavior classes and suicidal behaviors. While the use of nationally representative data enhances external validity, longitudinal studies are needed to explore how evolving patterns of health behaviors influence the onset or persistence of suicidal ideation and attempts over time. Second, both lifestyle and suicidal behaviors were assessed through self-reported measures, which may be affected by social desirability and recall biases. Third, the use of different timeframes for measuring behaviors (e.g., past 7 days, past 30 days and past year) may limit the temporal comparability between indicators, restricting interpretation regarding the co-occurrence or sequencing of behaviors.

Conclusion

This study underscores heterogeneity in adolescent healthy lifestyles and their associations with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. By incorporating both traditional health behavior factors and emerging behaviors such as e-cigarette use and problematic social media engagement, our findings offer a comprehensive and current account of how adolescent health lifestyles relate to suicide risk. Variation in associations across classes suggests that prevention and health promotion strategies should reflect the specific constellations of behaviors adolescents exhibit. Moving beyond single-risk approaches toward multidimensional, class-specific interventions may better address the complexity of youth health and support more effective prevention efforts.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2026.10147.

Data availability statement

The datasets that were generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to legal guidelines and ethical reasons, but are available from the corresponding author, SB, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

HBSC is an international study carried out in collaboration with WHO/EURO. The International Coordinator of the 2022 survey was Jo Inchley from the University of Glasgow, United Kingdom, and the Data Bank Manager was Oddrun Samdal from Bergen University, Norway. The HBSC Luxembourg study was a collaboration between the University of Luxembourg, the Ministry of Health and Social Security and the Ministry of Education, Children and Youth. The authors would like to thank the former PIs of the Luxembourg HBSC study, Andreas Heinz and Bechara Georges Ziadé, as well as the current PIs, Carolina Catunda and Maud Moinard, for their support. For details, see http://www.hbsc.org.

Author contribution

SB, RS, FGM, JLF and CC wrote the main manuscript text. SB performed the analyses. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Financial support

The HBSC Luxembourg was supported by the University of Luxembourg, the ministère de la Santé et de la Sécurité sociale and the ministère de l’Éducation nationale, de l’Enfance et de la Jeunesse. The funders were not involved in the data analysis or interpretation, the writing of this article or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standard

The HBSC 2022 Luxembourg study was approved by the Ethics Review Panel of the University of Luxembourg (ERP 21–013 HBSC 2022). Parents/guardians of these adolescents received an information letter about the survey, as well as an informed consent form with the opportunity to refuse/consent to their child’s participation. Informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians of all participants of the study.

Comments

Dr. Sarah Bitar

University of Luxembourg

Maison des Sciences Humaines

11, Porte des Sciences, L-4366 Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg

Email: sarah.bitar@uni.lu

Dear Editors,

I am pleased to submit our manuscript entitled “Adolescent health lifestyles and suicidality: Emerging risks in a latent class analysis ” for consideration in Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, as part of your special collection on “Self-harm and Suicide: A Global Priority.”

This study provides a person-centered analysis of how combinations of traditional (diet, physical activity, substance use) and emerging (e-cigarette use, problematic social media use) behaviors cluster into distinct adolescent health lifestyles, and how these patterns relate to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Drawing on data from a nationally representative sample of 6,187 adolescents aged 13–18 in Luxembourg, we identified five behavior classes using latent class analysis and examined their associations with suicidality through multilevel regression.

Our findings underscore that suicide risk is not solely associated with isolated risk behaviors, but often stems from co-occurring behavior patterns that reflect broader health lifestyles. Notably, classes marked by high substance use or digital vulnerabilities showed significantly elevated odds of suicidal ideation and attempts, even after adjusting for sociodemographic factors. These results offer timely insights for public health and education sectors, highlighting the need for integrated prevention approaches that address multiple co-occurring behaviors and tailor interventions to specific adolescent profiles.

This manuscript is original, has not been published, and is not under consideration elsewhere. All authors meet authorship criteria and have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study protocol was approved by the University of Luxembourg’s Ethics Review Panel (ERP 21-013 HBSC 2022).

We appreciate your consideration and hope our work contributes meaningfully to the global dialogue on adolescent suicide prevention.

Sincerely,

Dr. Sarah Bitar