I. Introduction

In recent years, the increasing frequency and intensity of global disruptions, from natural disasters to systemic crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, have significantly affected societal stability and economic development worldwide. These events often occur with little warning, catching market participants off guard and triggering widespread consequences.

Global supply chains, which have become the backbone of modern economies, are particularly affected by these disruptions. Under normal conditions, these interconnected networks allow companies to leverage comparative advantages, optimise production, and access global markets. Under a disruption, their tight interdependence means that a problem affecting one company in the chain can quickly cascade to others in the same supply chain. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns in manufacturing hubs led to shortages of medical supplies, semiconductors and essential components, which in turn delayed production and delivery across industries.Footnote 1 To analyse how such systems absorb and recover from disruptions, the resilience of the supply chain is often examined at three levels: the micro level of buyers and suppliers, the meso level of interacting supply networks, and the macro level of broader interactions between corporations and institutional or systemic environments.Footnote 2 Within this structure, the micro level, enterprise resilience, is particularly significant because the adaptive capacity of individual companies shapes the resilience of the wider network. Enterprise resilience refers to a company’s capability to survive, adapt and grow in the face of change and uncertainty.Footnote 3 Such enterprise resilience serves as the foundation of supply chain resilience, which refers to a network’s ability to recover and return to normal operations after unexpected disruptions that affect one or more of its components.Footnote 4 Governments around the world have responded by adopting measures to either anticipate and prevent disruptions or reduce their impact when they happen. In particular, the EU has promoted supplier diversification, increased domestic production capacity and supported digitalisation to improve supply chain visibility.Footnote 5 Among these initiatives, regulatory measures play an especially influential role because they shape both enterprise-level and system-level resilience. Regulation establishes a chain of influence, where regulations first impact the enterprise resilience and then these enterprise-level effects spread through the meso and macro levels of the supply chain. For this reason, the resilience of individual companies forms a critical foundation for the resilience of the overall supply chain. This article, therefore, concentrates specifically on the regulatory impact on enterprise resilience. Regulation can either strengthen or weaken the enterprise resilience. For instance, an excessive number of regulatory requirements may increase compliance burdens, diverting resources away from strategic planning and innovation, and thereby weakening a company’s ability to respond to disruptions.Footnote 6 Conversely, well-designed regulations may encourage companies to diversify suppliers or invest in risk management systems, enhancing their ability to withstand shocks.Footnote 7

Among all recent EU regulations, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), which entered into force on 25 July 2024,Footnote 8 is often referred to as the EU’s first “supply chain law”, serving as a representative example of how EU regulation can impact companies’ activities when facing supply chain disruptions and further shape resilient supply chains. As regulatory landscapes become more complex, companies must incorporate legal foresight into supply chain planning, not only to ensure compliance but also to leverage regulatory frameworks as tools for strategic resilience.Footnote 9 Recognising and responding to the potential impacts of regulation is essential for mitigating risks and capitalising on opportunities that arise from legal change.Footnote 10 In response to practical needs, this article uses the CSDDD to explore the evolving role of the EU regulation in shaping enterprise resilience. It analyses whether the CSDDD strengthens or hinders EU companies’ ability to withstand and adapt to disruptions, offering insights into the balance between regulatory ambition and operational flexibility in an increasingly uncertain global environment.

II. Conceptual framework

1. Corporate sustainability due diligence directive (CSDDD) in a nutshell

The CSDDD is widely recognised as the EU’s first comprehensive supply chain regulation. It introduces mandatory due diligence obligations for large companies, requiring them to identify, prevent, mitigate, and remedy adverse human rights and environmental impacts throughout their operations, subsidiaries, and business relationships (Recital 1&14; Article 6&7&8). The Directive is grounded in the EU’s long-standing commitments to environmental protection and human rights, as reflected in Article 191 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU),Footnote 11 the European Green DealFootnote 12 (Recital 2), and the goal of achieving a just transition to sustainability, as highlighted in the Commission’s Communication A Strong Social Europe for Just TransitionFootnote 13 (Recital 3).

The CSDDD applies to large companies with 1000 employees and a net annual turnover of EUR 450 million.Footnote 14 Reaching consensus on these thresholds was particularly challenging for Member States, as higher thresholds reduce the number of companies subject to the directive. After deliberations, the final CSDDD reflects compromises, raising the original employee threshold from 500 to 1000 and increasing the turnover requirement from EUR 150 million to EUR 450 million. According to the estimate of SOMO, there are 3363 countries in 27 EU countries that shall comply with CSDDD.Footnote 15 The CSDDD requires companies to assess their own activities, as well as those of their subsidiaries and primary collaborators, at every stage of the supply chain to identify potential harm to human rights and the environment (Recital 1&14 & Article 6–8). Moreover, the CSDDD adopts a forward-looking risk-based standard for corporate accountability: companies are required to act when risks of human rights abuse or environmental harm are reasonably foreseeable (Recitals 33–37, 41&42). Micro-enterprises and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are not directly subject to the proposed rules. However, the CSDDD acknowledges that SMEs, with no more than 500 entities, may be indirectly affected as business partners within larger value chains. To mitigate potential challenges, the CSDDD incorporates supporting and protective measures designed to ease compliance pressures on SMEs while fostering responsible business conduct.Footnote 16

2. Enterprise resilience: key capabilities for companies’ supply chain

Enterprise resilience refers to a company’s capability to survive, adapt, and grow in the face of change and uncertainty.Footnote 17 More broadly, enterprise resilience reflects the ability of a company to absorb shocks and maintain continuity in the face of crises, whether caused by natural disasters, geopolitical tensions, or systemic failures.Footnote 18

To make itself resilient in the supply chain, a company must sharpen both its spear and its shield. The spear represents proactive capabilities, which prepare the company in advance to anticipate risks and prevent disruptions from escalating.Footnote 19 The shield, in contrast, symbolises reactive capabilities, which protect the company during disruptions and support its recovery, ensuring a swift return to stability.Footnote 20

This distinction aligns with a functional and temporal perspective: proactive capabilities are deployed before disruptions occur, while reactive capabilities are activated during and after disruptions. The resilience of the supply chain depends on a company’s ability to balance both types of capabilities. Before disruptions arise, companies must be ready, able to detect early warning signals, assess potential impacts, and take preventive action. Once disruptions strike, they must respond quickly and recover efficiently to minimise damage and restore operations.

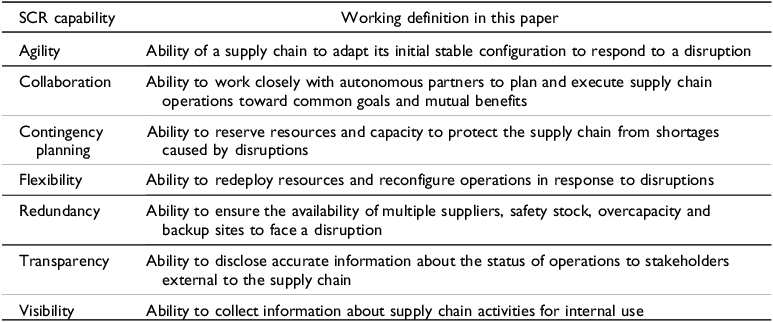

In this sense, resilience requires companies to develop a broad set of skills.Footnote 21 Previous work on management has identified a diverse set of capabilities (see Table 1) that companies need to develop to increase their resilience.Footnote 22 This paper focuses on seven of the most widely discussed in the literature: agility, collaboration, contingency planning, flexibility, redundancy, transparency, and visibility.Footnote 23

Table 1. Working definitions of capabilities required to build supply chain resilience.

Focusing on proactive capabilities, companies must be well-prepared for the possibility of disruptions. Three key capabilities stand out in this regard, which are transparency, visibility, and contingency planning.

Transparency refers to the ability to disclose accurate information about the status of operations to stakeholders external to the supply chain.Footnote 24 Transparency can help reduce information asymmetry, allowing supply chain partners to coordinate more effectively and respond to emerging threats in a unified manner, which builds trust among stakeholders and enables better risk identification by ensuring all parties have access to critical data, such as supplier performance or market trends.Footnote 25 Visibility refers to a company’s ability to collect information about supply chain activities for internal use,Footnote 26 such as tracking inventory levels, supplier performance, and logistics movements in real time. When companies can see what’s happening across their supply network, they’re better equipped to stay ahead of risks and maintain smooth operations even in uncertain environments. Contingency planning refers to the ability to reserve resources and capacity to protect the supply chain from shortages caused by disruptions.Footnote 27 Instead of reacting in panic, firms with well-developed contingency plans can activate pre-arranged responses, such as switching to backup suppliers, rerouting logistics, or reallocating resources. quickly and effectively.Footnote 28

When a disruption occurs, companies must respond quickly and effectively to minimise damage and restore operations. This stage of resilience relies on a set of reactive capabilities that enable firms to adapt, coordinate, and recover under pressure. Four key capabilities are especially critical: agility, flexibility, collaboration, and redundancy.

Agility refers to the ability of a company to adapt its initial stable configuration to respond to a disruption.Footnote 29 It ensures the company can respond swiftly to minimise damage.Footnote 30 Flexibility refers to the ability to redeploy resources and reconfigure operations in response to disruptions.Footnote 31 It involves the ability to adjust processes, resources, or strategies to meet new demands. Unlike agility, which emphasises speed, flexibility focuses on the range and depth of adjustments a company can make, such as switching suppliers, modifying production processes, or altering transportation routes, even if these actions deviate from standard procedures.Footnote 32 Flexibility enables companies to absorb shocks and continue operating under constrained conditions, reducing the risk of prolonged downtime.Footnote 33 Collaboration is the ability of companies to work closely with autonomous partners to plan and execute supply chain operations toward common goals and mutual benefits.Footnote 34 It involves joint problem-solving, resource sharing, and synchronised decision-making, which are especially critical during disruptions when rapid alignment is needed.Footnote 35 Redundancy refers to the ability to ensure the availability of multiple suppliers, safety stock, overcapacity, and backup sites to face a disruption.Footnote 36 The presence of multiple suppliers, safety stock, overcapacity, and backup suppliers can help ensure the smooth provision of products and services.Footnote 37 Conversely, markets with a small number of players, or markets with high barriers to entry, may make it harder for domestic companies to recover.Footnote 38

Although each capability is associated with a specific stage, these distinctions are not rigid. Capabilities often overlap and reinforce one another across multiple phases. For example, visibility supports both early detection and real-time response, while collaboration is essential for both contingency planning and coordinated recovery. This fluidity implies that resilience is not built through isolated interventions but through a coherent system of capabilities that interact dynamically across time and context.

III. Methodology

To explore this issue, the article mainly uses doctrinal research, complemented by a structured coding of legal provisions to support the legal analysis. The doctrinal method used in this research encompasses two stages: decoding selected regulations to fit the resilience theoretical framework and analysing their potential impact on EU companies within the supply chain.

The CSDDD consists of ninety-nine recitals and thirty-nine articles. In our analysis, we code both the recitals and the main text article by article, which helps us understand the legislators’ intentions as well as the substantive content, primarily the obligations and rights established for the subjects covered by the regulation. The entire coding process could be divided into two steps:

Firstly, we analyse the meaning and overall implications of each article for companies. This provides a broad understanding of the regulation’s effects, which will later be complemented by a more focused analysis of its impact in scenarios involving supply chain disruptions. As for each article, we consider its subject, objectives, requirements, and expected outcomes. This entails examining each article’s subject matter to understand its scope and purpose, identifying targeted industries or sectors. Additionally, we assess the article’s objectives, such as promoting competition and scrutinising the prescribed obligations, including compliance standards and enforcement mechanisms. Furthermore, we map the expected outcomes of the article, aligning with the aims of legislators, which helps us anticipate impacts or benefits for companies in the next step. Such understanding of the CSDDD forms the basis for further analysis and evaluation of its impact on EU companies.

Secondly, we assess the potential impact of each article on companies in the context of supply chain disruptions. This involves examining the specific capabilities that companies need to effectively respond to such disruptions, as identified in the supply chain resilience literature. By aligning the regulatory requirements of the CSDDD with these capabilities, we aim to evaluate how the Directive may support or challenge companies in managing disruption-related risks. Our analysis focuses only on those provisions that, based on insights from the supply chain resilience literature, are likely to influence corporate behaviour during disruptions. As a result, certain recitals and articles that fall outside this scope have been excluded from our coding and discussion. These include provisions relating to institutional scope exclusions, such as pension institutions operating social security systems (Recital 18), and sector-specific rules, notably those targeting financial undertakings (Recital 51). Additionally, technical provisions concerning conflicts of law (Recitals 17, 27, 43, 67), overlapping liabilities (Recital 22), and the discretion of Member States to adopt more stringent national measures (Recital 31; Article 4) are not included in the further analysis, as they do not directly inform the supply chain dimension. Detailed procedural and administrative rules, such as the civil liability regime (Recitals 79–91) and institutional arrangements for implementation and coordination at the EU level (Recitals 92, 93, 94, 97, 99), are also excluded from the coding, given their limited relevance to the analysis of corporate operational obligations within global value chains.

With this methodology, we plan to answer the question: What is the impact of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) on the supply chain resilience of EU companies ?

IV. Impact of CSDDD on each capability of enterprise resilience

1. Visibility

Visibility refers to a company’s ability to understand and monitor what is happening within its supply chain. To comply with the CSDDD, both EU and foreign companies operating in the EU internal market are required to engage in extensive information collection to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for actual and potential adverse impacts on human rights and the environment in their supply chains (Recital 7). The type and scope of information required are largely shaped by the EU’s international commitments in areas such as responsible business conduct, climate action, biodiversity and human rights. To assist companies, the Directive includes an Annex listing prohibited activities under international agreements, but it also extends beyond this to encompass other relevant instruments (Recital 25). However, the Commission provides little concrete guidance on what information must be collected. Combined with the open-ended nature of the obligation, this lack of clarity leaves companies uncertain about what exactly they are expected to do, precisely what information they shall provide. As a result, even if EU companies gain some visibility into their supply chains, they cannot be sure that the information they obtain is sufficient to meet due-diligence requirements or to strengthen their resilience against risks.

The CSDDD outlines two approaches for EU companies to collect the required information: independent information collection and joint information collection with other entities. Companies must conduct both, which impose different levels of regulatory burden.

In the independent collection, responsible EU companies must actively gather data on their own activities and those of their subsidiaries that may impact human rights or the environment (Recital 29). However, this obligation does not extend to trade secrets, such as intellectual capital, intellectual property, know-how, or innovation results, which remain protected (Recital 23&64). EU companies must also conduct periodic assessments of their own operations, as well as those of their subsidiaries and business partners, to evaluate the effectiveness of the measures taken to address adverse impacts (Article 15). Complementing this obligation, EU companies must monitor the effectiveness of their due diligence measures at least once every 12 months. To assist companies and reduce compliance costs, the Commission is tasked with issuing guidelines, including references to appropriate digital tools and technologies to support information gathering for supply chain management (Recital 68). It will also define additional rules concerning the content and criteria of due diligence reporting, with attention to Union data protection law (Recitals 95 & 96).

Companies may also actively participate in the development of industry schemes with stakeholders aimed at identifying, mitigating, and preventing adverse impacts (Recital 37; Articles 10 & 14). Although participation in such schemes is voluntary, it is strongly encouraged by the Commission as a means to promote collective responsibility and sectoral alignment.

2. Transparency

In both independent and joint (active) information collection, companies generally have access to information related to their own operations and those of their business partners. However, a key challenge remains: whether EU companies can access information collected by other companies or entities with which they are not directly involved. To support intra-group transparency, companies falling within the scope of the Directive, whether parent or subsidiary, are entitled and required to share information within their group and with other legal entities (Recital 21; Article 5). Each company remains individually responsible for conducting due diligence and ensuring internal information flows effectively across the group. To ensure transparency, companies are required to document their due diligence efforts, particularly any prevention or corrective action plans, and retain this documentation for at least five years (Recitals 61 & 64).

Beyond internal sharing, the Directive promotes broader stakeholder engagement. Companies are required to establish meaningful dialogue with stakeholders to gather relevant information and coordinate their activities in the fields of human rights and environmental protection (Recital 40). In addition to these active engagement duties, information also comes through oversight by public authorities in the Member States, which act as national supervisory bodies.

These authorities have the power to initiate investigations, request information from companies, and publish annual reports on their findings (Recital 75; Articles 24–27). Companies are required to cooperate with these authorities, and failure to comply may lead to sanctions (Article 27). This passive oversight plays a key role in ensuring official sources of information are available and reliable. To enhance coordination, the Commission is mandated to establish a European Network of Supervisory Authorities, which facilitates mutual assistance and harmonisation among national regulators (Recital 78; Article 28).

Moreover, transparency is further enhanced through the mandatory publication of annual reports. These reports must be made available on the company’s website and will also be accessible through the European Single Access Point (ESAP) (Recitals 62 & 63; Articles 16 & 17), enabling wider visibility across the market. To facilitate access and coordination, the Commission will establish a single helpdesk, which will provide tailored guidance, request information where needed, and collaborate with national authorities across Member States (Recital 70). This mechanism is intended to adapt information flows to national contexts and help companies meet their obligations more efficiently.

An additional source of information is the Commission’s report to the European Parliament and the Council on the implementation and effectiveness of the Directive (Recital 98). Although the Directive does not specify whether this report will be publicly accessible, its publication could significantly aid companies in assessing supply chain resilience within the EU internal market, particularly during disruptions or emerging risks. At the broader international level, the Directive promotes the development of multilateral networks to support companies in collecting and sharing information. These networks may include the EU, Member States, international organisations such as the OECD, and other stakeholders (Recital 37). The exchange of information on due diligence policies, processes, findings, and outcomes among these parties is encouraged (Recital 44).

3. Flexibility

The CSDDD establishes rules for companies to address adverse impacts on human rights and the environment (Article 1). This obligation applies at all times, including during urgent or crisis situations, as the Directive does not allow for derogations in emergencies (Recitals 15 & 29). To provide companies with legal clarity and certainty, the Directive required the Commission to specify which actions companies should be required to take in specific circumstances to help companies fulfil their due diligence obligations (Recital 53; Article 19 & 20). One case is that in the situation of state-imposed forced labour, where companies have no reasonable expectation that their efforts could prevent or mitigate the adverse impact on human rights protection, the companies shall terminate the business relationship (Recital 50).

At the same time, the Directive does not impose obligations of result. Companies are not required to guarantee that no adverse impacts will occur. Rather, the CSDDD establishes obligations of means, requiring companies to take reasonable and proportionate steps to identify, prevent and mitigate such impacts (Recital 19). Where it is not feasible to address all identified risks simultaneously, companies are permitted to prioritise the most serious adverse impacts (Recital 80; Article 9). The Directive provides general criteria for prioritisation, including the severity (measured by scale, scope or irremediable character) and likelihood of the adverse impact (Recital 44). Companies must also assess the degree of their involvement, whether they “cause,” “contribute,” or “are directly linked to” the adverse impact, reflecting a diminishing level of responsibility (Recital 45; Article 11). While these provisions offer some structure, prioritisation is inherently context specific. In practice, especially under the time pressures of disruption, decisions on which impacts to address first must often be made immediately and independently by companies. The Directive does not clearly specify whether, or how, the Commission or national authorities will review the appropriateness of these decisions, or whether companies will face sanctions for incorrect prioritisation. As a result, companies retain a degree of discretion, but they also bear the burden of justifying their decisions in hindsight.

The Directive allows companies, as a measure of last resort, to terminate existing business relationships or refrain from entering new ones where adverse impacts cannot be prevented or mitigated (Recital 50; Articles 10 & 11). However, the Commission’s recent Omnibus Proposal removes the duty to terminate such relationships.Footnote 39 Instead, it introduces an option for EU companies to suspend the business relationship while continuing to engage with the partner to seek a solution. This added flexibility recognises that companies may operate in circumstances where their production depends heavily on one or a few key suppliers.Footnote 40

4. Collaboration

Collaboration refers to the company’s ability to work closely with autonomous partners to plan and execute supply chain operations in the face of risks. In the CSDDD, this collaborative dimension appears in how due diligence responsibilities can be shared or transferred within a group of companies. Parent companies may carry out due diligence on behalf of their subsidiaries, particularly when the subsidiaries themselves fall outside the scope of the Directive. In such cases, the parent company is expected to include the operations of those subsidiaries within its own due diligence process (Article 6). More broadly, companies are encouraged to cooperate with supply chain actors best positioned to prevent or mitigate adverse impacts (Recital 49). Such cooperation is essential for comprehensive and effective due diligence across the entire value chain.

Additionally, companies are required to actively engage with relevant stakeholders, which includes maintaining an open dialogue and sharing comprehensive and relevant information with them (Recital 65; Article 13). To support stable and predictable collaboration, the Directive requires the Commission to provide guidance on model contractual clauses, which includes a clear allocation of tasks (Recital 66 & Article 18). However, such collaboration remains largely focused on pre-emptive information sharing. The Directive does not provide a concrete mechanism to enable real-time, coordinated action among buyers and suppliers in response to disruptions. As such, the capacity of these networks to facilitate rapid, joint responses in times of crisis remains limited.

Such collaboration is also supported externally under the CSDDD. The Directive envisions a supporting role for the European Commission and Member States in promoting awareness and facilitating access to industry initiatives. This includes issuing guidance on the fitness criteria and methodologies companies can use to assess the value of such initiatives (Recitals 52 & 57). Companies may also rely on independent third-party verification to support their due diligence (Article 10). While this can offer additional assurance and credibility, the Directive does not yet establish clear EU-wide criteria for qualifying or certifying such third parties, leaving some uncertainty regarding the standards and reliability of external verifiers.

Moreover, to lower the chance for the EU companies to violate this Directive due to the activities of their third-country business partners, the Union and Member States are encouraged to use their neighbourhood, development and international cooperation instruments, including trade agreements, to support third-country governments and upstream companies in third countries to address the adverse impact on human rights and environmental protection rising from their activities (Recital 72).

5. Redundancy

Redundancy requires the availability of alternative suppliers within a company’s supply chain. A key question under the CSDDD is how the Directive affects this redundancy, particularly through its influence on the participation of third-country companies in the EU internal market.

The Directive may reduce redundancy of EU companies operating in large global supply chains with diverse foreign suppliers. Because it imposes rigorous due diligence requirements on all companies within its scope, including third-country suppliers. These requirements, focused on human rights and environmental standards, could act as a barrier for some foreign companies, especially those in developing economies with lower or less aligned standards than the EU. If the costs of accessing the EU market outweigh the benefits of compliance, foreign suppliers may choose not to enter or remain in the EU market, thereby reducing the pool of available partners for EU companies.

At the same time, the CSDDD provides mechanisms to support foreign participation. For instance, third-country companies are allowed to appoint a representative in the Member State where they generate the most turnover, ensuring better communication with supervisory authorities and reducing compliance friction (Recitals 30 & 74; Article 23).

Beyond its impact on foreign suppliers, the Directive’s effect on supply-chain redundancy also depends on how smaller domestic actors can participate. The Directive acknowledges the role of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). While SMEs are not directly targeted by the Directive, they often operate as business partners within supply chains covered by the regulation. To avoid unintended negative impacts on these entities, especially in sectors like agriculture and food, the Directive requires companies to offer targeted and proportionate support to SME partners. This may include capacity-building, financial assistance, training, or support for upgrading management systems (Recitals 46 & 47 & 56; Articles 10 & 11). Additionally, Member States are required to provide financial and informational support to help SMEs comply and remain competitive (Recital 69).

6. Agility

Agility requires companies to quickly respond to disruptions. Regulatory requirements can potentially speed up or slow down response time. In the case of the CSDDD, a company’s agility in responding to disruptions depends on whether the activity in question is likely to cause adverse impacts on human rights or the environment. The Directive does not apply to activities that pose no such risk.

For activities that do have potential adverse impacts, the Directive imposes specific obligations on companies to prevent and mitigate these risks (Recitals 36 & 38 & 39). A key requirement is the prioritisation of engagement with business relationships across the value chain. Due diligence under the CSDDD is not a one-time obligation, but a continuous process that must extend throughout the entire life cycle of a product or service, including production, distribution, transport, storage and provision (Recital 24). This means companies must remain alert throughout their operations and those of their subsidiaries and business partners. The scope of the supply chain covered by the Directive is broad, encompassing both upstream and downstream partners (Recitals 25 & 26), making sustained engagement and monitoring essential.

The CSDDD aims to improve companies’ responsiveness by strengthening the early detection of human-rights and environmental risks. However, it does not introduce any formal “early warning system.” Instead, agility is shaped by how the Directive embeds due diligence into corporate governance, and strict procedural requirements may still slow action if they are not implemented efficiently.

The CSDDD obligates EU companies to continuously identify and assess actual and potential adverse impacts across their value chain, supporting ongoing awareness of emerging risks (Articles 8 & 9). The Directive also requires companies to adopt a risk-based due-diligence programme and integrate it into their corporate policies and risk-management systems (Articles 5 & 7), ensuring that risk considerations are addressed systematically rather than on an ad hoc basis. Article 12 adds a further requirement to regularly verify the effectiveness of these measures, keeping risk-management processes up to date. Taken together, these obligations strengthen awareness and consistency, but they also introduce procedural and administrative demands that may slow decision-making and reduce agility.

7. Contingency planning

The CSDDD requires companies to integrate due diligence into their policies and risk management systems. This includes identifying, assessing, prioritising (when necessary), preventing, mitigating, and, where relevant, bringing to an end or minimising actual and potential adverse impacts on human rights and the environment (Recital 38; Article 7).

As part of this process, companies must ensure that their code of conduct applies across all relevant business operations, such as procurement, employment, and purchasing decisions (Recital 39). The Directive also obliges companies to develop various plans in response to identified risks. One key requirement is the creation of a prevention action plan where potential adverse impacts are identified (Recital 46; Article 10). When an adverse impact cannot be immediately addressed, the company must prepare a corrective action plan. This plan should clearly outline a roadmap for terminating the adverse impact and must align with the company’s overall business strategy and operations (Recital 54; Article 11).

Contingency planning also includes provisions for remediation. If a company causes or jointly contributes to an actual adverse impact, it is required to restore the situation to the condition it would have been in had the impact not occurred (Recital 58). This represents a high standard of remediation, potentially involving compensation, restoration or other corrective measures. To facilitate this, companies must establish complaint procedures that are fair, accessible, predictable, transparent and publicly available. They are also required to inform employees, trade unions, and other relevant stakeholders about these procedures (Recitals 59 & 60; Articles 12, 14, 26 & 29). This introduces additional administrative obligations, as many companies will need to develop new internal systems for handling such complaints. Importantly, these company-level grievance mechanisms do not replace existing national civil or criminal legal remedies. Affected individuals or groups retain the right to pursue claims under national law (Recitals 86 and 89). Although the principle of ne bis in idem (no double punishment) reduces the risk of companies facing duplicate penalties, involvement in both internal and external procedures will likely increase compliance costs and legal exposure.

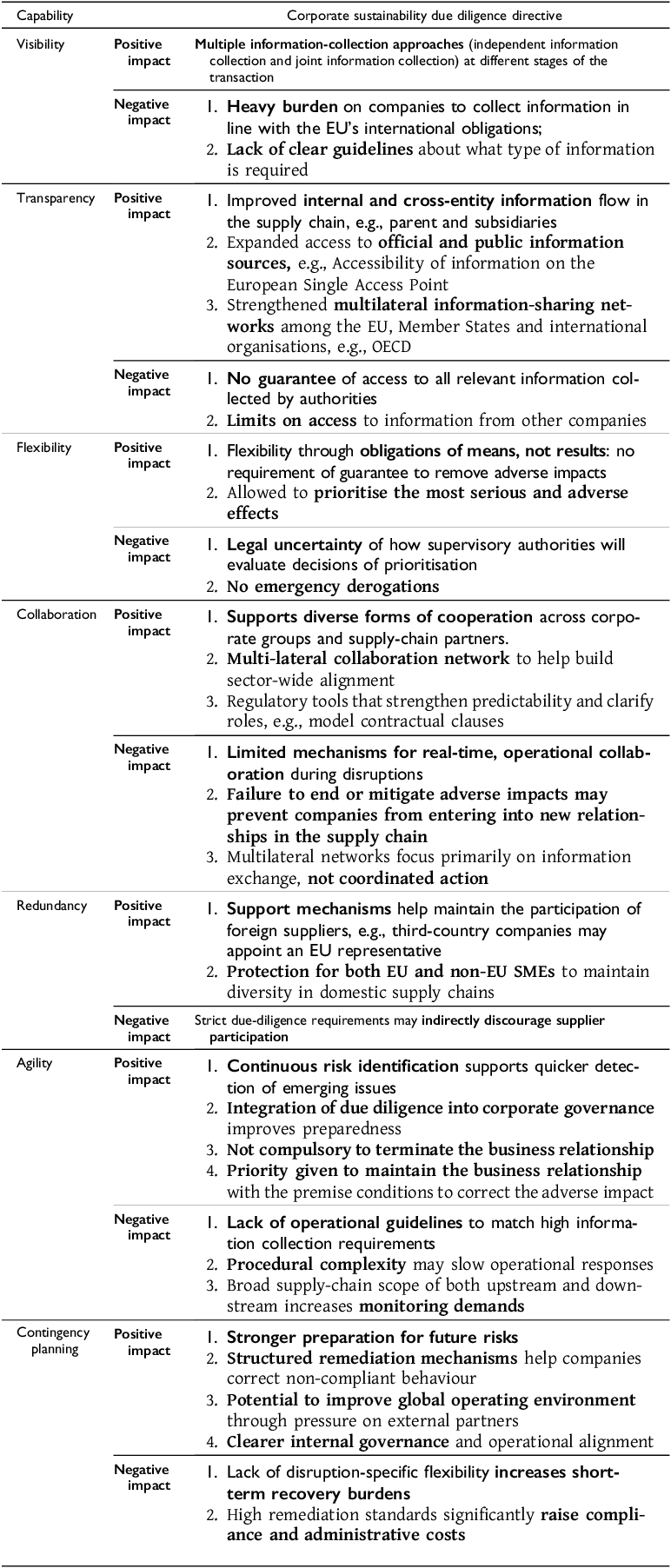

Based on the above analysis, we can see that different articles within the CSDDD may have either a positive or negative impact on companies’ specific capabilities relevant to supply chain resilience. By categorising these impacts according to the resilience capabilities, we can observe that the regulation as a whole exerts both positive and negative impacts across all capabilities. These dual impacts are systematically summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of CSDDD impact on enterprise resilience.

V. Interdependencies among enterprise resilience capabilities

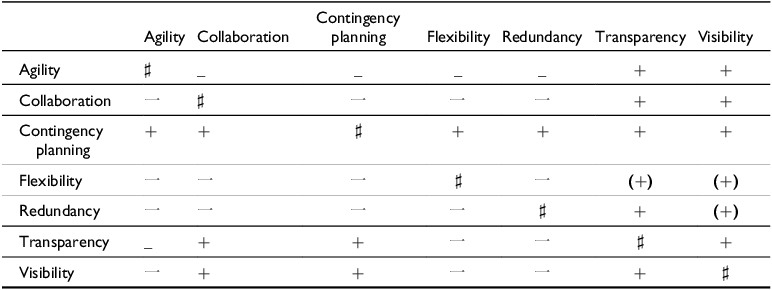

The seven enterprise resilience capabilities, agility, collaboration, contingency planning, flexibility, redundancy, transparency and visibility, are deeply interconnected. The impact of regulation on these capabilities is rarely linear or isolated. Instead, these effects are often interconnected and multidimensional. A single regulatory provision may influence multiple capabilities simultaneously. Even when a regulation does not directly target a particular capability, its influence on one area may indirectly shape others. These interactions might be synergistic, conflicting, or conditional.

Table 3 presents a qualitative matrix that illustrates the nature of these interrelationships. In this matrix, we adopt a unidirectional assessment approach. The capabilities listed in the left-hand column serve as the reference point. We assume that legal or regulatory interventions positively influence these vertical capabilities. Under this condition, we further explore how improvements in these vertically listed capabilities may in turn affect the horizontally listed capabilities.

Table 3. Qualitative matrix of interactions among enterprise resilience capabilities.

To ensure clarity, all seven capabilities are placed on both the vertical and horizontal axes. The diagonal cells, representing self-impact, are marked with “#” and excluded from analysis. A “+” indicates a synergistic relationship, where the regulatory impact on the vertical capability is likely to enhance the corresponding horizontal capability. A “–” indicates a conflicting relationship, suggesting a potential trade-off, where the current regulatory impact on one capability may reduce the effectiveness of another. A “(+)” indicates a conditional relationship, where the impact is context-dependent and may become beneficial under favourable conditions, such as effective stakeholder behaviour or coordination.

First, under the current CSDDD framework, only a limited number of capability improvements generate positive spillovers into other areas of supply chain resilience. This is because most CSDDD provisions primarily emphasise information collection, disclosure, documentation, and oversight, which tend to increase transparency and visibility but constrain more operational capabilities, such as agility, flexibility and redundancy. As a result, the regulation rarely strengthens multiple capabilities simultaneously; instead, it strengthens informational capabilities, which then exert positive effects on a small number of other capabilities.

An initial area where synergy does emerge is through the CSDDD’s strong emphasis on transparency and visibility. The matrix shows that increases in transparency lead to improvements in collaboration and visibility, while visibility positively affects collaboration and contingency planning. This reflects the fact that, for EU companies, CSDDD’s extensive due diligence, reporting and documentation requirements generate larger and more structured information pools. Although these requirements do not directly improve operational responsiveness or flexibility, they do improve companies’ ability to understand the conditions and behaviours of their supply chains. With clearer data about suppliers, risks, and operational conditions, EU companies can collaborate more selectively and more effectively, identifying which partners are reliable and which bottlenecks require joint intervention.

For example, according to Article 21, information will be centralised through a single helpdesk and requires coordination among Member State authorities. For EU companies, the result is greater institutional clarity, improved access to information, and more consistent guidance, all of which reinforce their ability to collaborate within their own supply chains and with external partners. A similar dual effect emerges from Articles 24 to 27, which establish supervisory authorities and require third-country companies to appoint EU representatives. These provisions expand channels for information exchange and regulatory oversight, thereby simultaneously enhancing transparency and enabling more structured collaboration among companies in the supply chain.

Beyond informational capabilities, the matrix shows a synergistic interaction between Agility and Contingency Planning (“+”). Although CSDDD does not directly improve agility, in fact, the regulation constrains fast responses due to documentation and procedural requirements, the mandated development of risk identification mechanisms, escalation channels, and due-diligence processes can indirectly support contingency planning.

The matrix highlights Contingency Planning as the capability with the most consistent positive spillovers. Its row contains multiple “+” entries, indicating that when EU companies develop more robust contingency plans, including scenario analyses, response pathways, and continuity structures, these improvements positively influence several capabilities, including collaboration, visibility, and redundancy. Strong contingency planning can support organisational coherence, facilitate better use of the information generated through CSDDD, and enhance EU companies’ ability to coordinate responses across their supply chains.Footnote 41

Second, while a small number of informational capabilities show positive or synergistic spillovers, the interaction matrix reveals that most operational capabilities experience conflicting relationships under the CSDDD. These conflicts arise because the regulation imposes intensive information-gathering, documentation, verification, and reporting obligations, which tend to slow decision-making, reduce flexibility, and limit company’s ability to reconfigure operations rapidly. A first and consistent pattern in the matrix is the tension between Collaboration and several core operational capabilities. Collaboration shows negative (“–”) effects on Agility, Contingency Planning, Flexibility, and Redundancy because the CSDDD requires formal engagement, stakeholder consultation, and multi-party alignment. These obligations increase coordination overhead, which slows EU companies’ ability to adjust operations, activate contingency plans quickly, and reconfigure production or logistics structures when disruptions occur.

The matrix also shows that Transparency and Visibility have negative (“–”) effects on several operational capabilities. Transparency reduces Agility, Flexibility, and Redundancy because CSDDD requires companies to document processes, standardise procedures, and maintain auditable data trails. For EU companies, this means that changing suppliers or adjusting production becomes slower and more constrained, as every deviation must be justified and documented. As a result, agility falls, flexibility is reduced, and redundancy strategies that rely on multiple alternative options become harder to maintain.

Flexibility itself shows “–” interactions toward Collaboration, Transparency, and Visibility in the matrix. Under CSDDD, maintaining high flexibility multiplies the information required and increases the risk of non-compliance, pushing EU companies toward more standardised and less adaptable setups. A similar constraint applies to Agility, showing “–” interactions with Collaboration, Flexibility, Redundancy and Visibility. CSDDD’s due-diligence, monitoring, and verification procedures require EU companies to establish slow, formalised processes for decision-making. These procedures conflict with the speed and improvisation required for agility, leading to systematic negative interactions with other capabilities that depend on rapid response or structural freedom.

Redundancy is strongly constrained by CSDDD, which shows “–” effects toward other capabilities such as Agility, Flexibility and Visibility. Maintaining redundant suppliers or inventories means EU companies must trace, verify and report on a larger number of supply-chain actors and product flows. This burden becomes even heavier when redundant suppliers are outside the EU, since foreign suppliers often provide incomplete data or require additional checks to meet CSDDD standards. As a result, redundancy is more expensive, administratively complex and difficult for EU companies to justify under the regulation.

Third, the matrix also shows several conditional (“(+)”) relationships, where the impact is context-dependent and may become beneficial under favourable conditions. A clear example is the relationship between Transparency and Flexibility. Flexibility shows a conditional positive (“(+)”) effect on Transparency: adjusting sourcing options or exploring alternative suppliers may reveal additional information that enhances due-diligence processes. However, this positive effect is conditional on effective implementation. If the documentation and traceability requirements become too heavy, EU companies prioritise compliance over exploration, and the potential transparency gains do not materialise.

A similar conditional pattern appears between Visibility and Agility. According to the matrix, Visibility can improve Agility (“(+)”) because clearer data can help EU companies act with greater confidence and prepare quicker interventions. However, this benefit only emerges when the information produced under the CSDDD is accurate, timely, and not overly burdensome to update. Another important conditional relationship is found between Visibility and Contingency Planning. The matrix indicates that improved visibility can support better contingency planning (“(+)”), but only when the information is detailed enough, and the company has the capacity to use it effectively. If EU companies are overwhelmed by the volume or complexity of data from CSDDD reporting, visibility does not translate into more effective contingency planning.

VI. Discussion

In today’s interconnected and complicated domestic and global landscape, EU legal acts are increasingly expected to do more than prescribe behaviour. Nowadays, EU regulations advance broader policy goals, such as sustainability, environmental protection, biodiversity restoration, and human rights, embedded in flagship initiatives like the European Green Deal Footnote 42 and the EU Industrial Strategy.Footnote 43 While, in theory, a single legislative instrument could advance multiple objectives simultaneously, in practice, the diversity of regulatory domains, each with distinct aims, stakeholders, and trade-offs, means that regulations tend to focus on subject matters.

This convergence raises two critical questions: 1. Do these embedded values complement or conflict with other legal and economic objectives? 2. Can individual regulations effectively realise all these values in practice? Our analysis of CSDDD’s impact on resilience can function as an example to answer these questions.

First, when multiple values are embedded in the same legal framework, EU law should explicitly recognise potential conflicts and provide proportionate flexibility to address them. Embedding multiple policy values in EU legislation, such as sustainability, environmental protection and human rights, is both inevitable and desirable. However, the complexity of modern economic systems means these values may interact in unpredictable ways, sometimes leading to tension or conflict.Footnote 44 To manage this, EU law should explicitly acknowledge such potential conflicts and incorporate proportionate flexibility to address them.

Our analysis of the CSDDD illustrates this challenge. Although resilience is not a stated objective of the directive, its implementation can significantly affect supply chain resilience. This underscores a broader point: regulations often have indirect effects beyond their primary aims.Footnote 45 In crisis conditions like pandemic-related border closures, EU companies may need to prioritise maintaining continuity of supply, even if this temporarily outweighs some sustainability targets, in order to restore operations quickly. While resilience can be considered a component of sustainability, the latter’s broad scope may impose obligations that hinder emergency response.Footnote 46 Rigid legal frameworks that ignore such trade-offs risk undermining economic adaptability. Currently, the CSDDD does not include derogation clauses for crisis conditions, leaving companies with little room to respond. To address this, narrowly defined flexibility mechanisms, such as time-limited derogations or phased compliance schedules, should be integrated into EU legislation.Footnote 47 These mechanisms would allow targeted adjustments without compromising the law’s core objectives. Crucially, terms like “emergency” or “urgency” must be clearly defined to prevent arbitrary application, in line with the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union. For example, while public interest derogations under Articles 36 and 52 TFEU are permitted, purely economic justifications are not accepted.Footnote 48

Second, in terms of the design of legal provisions, we can see that there may also be conflicts in the design of laws. Such conflicts do not arise in all scenarios but are triggered only under specific circumstances. This is reflected in the potential positive and negative impacts that may arise when designing the various capabilities of resilience. For example, during disruptions, an emphasis on transparency may affect the number of qualified third-country suppliers available for EU companies in the EU internal market. However, it is also important to recognise the positive impacts of regulations on multiple capabilities. For instance, adequate cooperation can enhance transparency, especially in the context of disruptions, where transparent information and communication are crucial for companies to resume operations. Since such impacts cannot be fully anticipated during the legal drafting phase, the law must balance mandatory regulations with market freedom.Footnote 49 In specific circumstances, when the law may have uncertain adverse effects on company operations, allowing companies to choose whether to comply with certain mandatory provisions based on their operational circumstances may be necessary.

The EU legislator will have to consider how to revise existing texts on aspects that affect not only the activities of businesses during disruptions, but also their day-to-day operations, which makes compliance with regulations burdensome for companies. Although disruptions have become more frequent in recent years, they are still rare in everyday business life. It is therefore impractical to design legislation exclusively for disruptive scenarios. There are a number of ambiguities in the regulations that affect not only the actions of companies in the face of disruptions, but also their day-to-day operations. For example, there is a lack of a list telling companies what information they have to provide, which reduces the possibility of transparency and visibility.

In this sense, the legislator could provide a short list of basic information that all companies should report, while leaving more detailed, risk-specific requirements to sector associations. A small set of common data points, such as the distribution of suppliers by country or the scale of annual transactions, would give companies clarity about the minimum expectations, without replacing the risk-based approach of the CSDDD. Industry bodies could then add further guidance tailored to the risks and structures of their sectors. At the same time, it is necessary to clarify who is entitled to receive such information and how to obtain it in order to increase visibility. Meanwhile, for mechanisms that coordinate the work of different agencies, such as information gathering mechanisms, the EU legislator also needs to use the law to clarify the agencies involved, the coordination mechanisms, and the rights and obligations of the agencies, which will increase the legal certainty of cooperation. However, amending the legal text is a long process, and the CSDDD is a newly enacted law, so amending the law in a short period of time may cause legal uncertainty and decrease the effectiveness when implementing these regulations. Therefore, if it is not possible to amend the law in a timely manner, the EU Commission may consider releasing detailed guidelines to facilitate their implementation, which is also required in the CSDDD. A guideline involves issuing adaptive, sector-specific guidance to clarify how legal obligations apply during disruptions, drawing on precedents such as the European Commission’s COVID-19 temporary frameworks in state aid law.

Third, improved implementation of EU law depends not only on the content of regulations but also on the ability of governments to adapt their institutional functions in a progressive manner that addresses both sustainability and resilience. At the most immediate level, competent authorities tasked with monitoring compliance, such as national supervisory bodies under the CSDDD, should systematically assess how enforcement actions affect core resilience capabilities, including redundancy, flexibility and contingency planning.Footnote 50 These include ex ante impact assessments to model trade-offs under crisis scenarios, stakeholder consultations to identify operational challenges and unintended effects, and scenario planning to anticipate regulatory performance under exceptional conditions.Footnote 51 It requires integrating resilience considerations into standard compliance reviews, rather than treating them as secondary concerns. Building on this, national administrations should strengthen cross-sectoral coordination by establishing interdepartmental structures that link sustainability enforcement with industrial and trade policy, thereby avoiding fragmented decision-making that could inadvertently reduce market access or operational capacity.Footnote 52 At a more strategic level, governments should invest in robust information infrastructures, such as shared platforms for supply chain data, which can provide real-time visibility for both regulators and regulated entities. Finally, long-term regulatory effectiveness requires enhanced engagement with third-country governments to facilitate supplier compliance with EU standards, thereby supporting sustainability and resilience while reinforcing the EU’s global regulatory influence.Footnote 53

VII. Conclusions

This article has explored the evolving role of EU regulation in advancing complex and interrelated policy values, particularly sustainability, environmental protection and human rights. As EU legislation increasingly seeks to embed these values across diverse regulatory domains, it faces the challenge of balancing ambition with operational feasibility. The analysis of the CSDDD demonstrates how regulations, even when narrowly framed, can produce wide-ranging effects, such as influencing supply chain resilience, beyond their stated objectives.

This paper shows that in the face of risks, a single regulation can affect several resilience capabilities of EU companies. The analysis of the CSDDD demonstrates that strict regulatory requirements without derogation clauses may constrain the ability of companies to respond to risks by limiting agility, flexibility and redundancy. In such situations, legislators need to assess the trade-offs among competing policy values and determine which objectives must take priority in specific risk scenarios.

Furthermore, the institutional design of regulations must account for the dynamic interplay among resilience capabilities. The qualitative matrix presented in this article illustrates how capabilities such as transparency, flexibility and redundancy can reinforce or constrain one another depending on context. Recognising these interdependencies is crucial for crafting coherent and adaptive legal instruments.

Ultimately, no single regulation can achieve all policy goals in all circumstances. However, by making trade-offs explicit, managing them transparently, and embedding adaptive mechanisms, EU law can maintain its coherence and effectiveness in a rapidly changing world. This approach not only strengthens the resilience of regulated entities but also reinforces the legitimacy and strategic capacity of the EU’s legal order.

Financial support

This research was funded by European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation program, under the Grant Agreement 101061729.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.