Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak a global pandemic in March 2020. Novel vaccines were given regulatory authorization in December 2020, and vaccination of populations was promoted as the primary way to end restrictive measures around the world. Vaccine hesitancy, defined as a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite the availability of vaccination services (MacDonald and Sage Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Reference MacDonald2015), was identified as a major obstacle to achieving this goal. It is notable that a significant percentage of HCWs proved to be hesitant. Maltezou and colleagues (Reference Maltezou, Dounias, Rapisarda and Ledda2022) reported that, as of August 2021, the median full vaccination rates among HCWs in 17 European countries was 79% (with exceptional differences between countries), and similarly, 30% of HCWs in US hospitals were still unvaccinated as of September 2021. In Greece, the vaccination rate of health personnel (medical, nursing, and laboratory staff) in public and private healthcare facilities was 70% (National Committee on Bioethics and Technoethics 2021).

Various governments, such as those of Italy, France, Greece (Law 4820/2021 article 205), Germany, Poland, Australia, and Canada, reacted aggressively by taking harsh measures, such as mandates stipulating dismissing HCWs from work unless vaccinated. Μandates were often presented in the media as a necessity, the rationale being that refusal to vaccinate manifests various moral failings on the part of HCWs, who violate the basic ethical principle of ‘do no harm’, showing lack of solidarity, disrespect toward medical institutions such as national vaccination committees, and ignorance of science, as we discuss extensively in the article.

In Greece, vaccine mandates were introduced for HCWs on 1 September 2021, and as a result around 6500 HCWs were initially suspended (Bouloutza Reference Bouloutza2022). Government action resulted in rallies and protests to change this decision and allow HCWs to return to work (Reuters 2021). In the following months, many HCWs underwent vaccination so as not to lose their jobs, and by December 2022 there were 2100 unvaccinated HCWs (Bouloutza Reference Bouloutza2022). Mandates ended in November 2022 when the Council of State (the top administrative court) decided that, while such measures could be lawfully enacted and enforced during a period of crisis, the principle of proportionality dictates that they be revoked once the crisis is over (Mandrou Reference Mandrou2022).

Yet, commentators have noted that mandates are counterproductive (Parker, Bedford, Ussher et al. Reference Parker, Bedford, Ussher and Stead2021). Politis and colleagues’ (Reference Politis, Sotiriou, Doxani, Stefanidis, Zintzaras and Rachiotis2023) systematic review of the literature found that HCWs in general oppose vaccine mandates (including the ones who were vaccinated) and warned policymakers against using such measures as they ‘[are] associated with the aggravation of distrust in officials, the depletion of healthcare facilities, political polarization, and decreased intent to receive both the COVID-19 vaccine and unrelated vaccines, such as the chickenpox vaccine’ (p. 19). Recognizing the systemic element that shapes the politics of hesitancy, the UK government changed their original decision to make vaccination mandatory for HCWs (Reuters 2022). It is in the same spirit that the WHO (2021a) warns against the adoption of coercive measures (as coercion would make things worse), while at the same time recognizing vaccine hesitancy as one of the major health challenges of our times.

Larson and colleagues (Reference Larson, Jarrett, Eckersberger, Smith and Paterson2014) explain that vaccine hesitancy is a complex phenomenon that extends to vaccines other than Covid-19 (ie the flu vaccine). Hesitant individuals range from complete acceptors to complete refusers and include intermediate positions where individuals may have doubts about certain vaccines but not others, delay getting the jab as much as possible, or even when they do get vaccinated, are not completely certain about either the merits or side effects. The WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (Sage 2012) produced a report that organizes reasons for vaccine hesitancy as based on (a) context (ie historic, sociocultural, institutional, economic, or political), (b) individual perceptions (ie natural immunity) and group influences (peers, family, and social groups), and (c) issues specific to the characteristics of the vaccine (ie research and development/authorization) or the vaccination process.

Indeed, in the case of the Covid-19 vaccine, various studies have shown that the decision to vaccinate depends on trust in government, ideas about government overreach and individual liberty, distrust toward pharmaceutical companies, and negative or positive lived experiences within people’s communities (Di Gennaro, Gakidou and Murray. Reference Di Gennaro, Murri, Segala, Cerruti, Abdulle, Saracino, Bavaro and Fantoni2021; Goldenberg Reference Goldenberg2021; Holzmann-Littig Reference Holzmann-Littig, Braunisch, Kranke, Popp, Seeber, Fichtner, Littig, Carbajo-Lozoya, Allwang, Frank, Meerpohl, Haller and Schmaderer2021; Politis, Sotiriou, Doxani et al. Reference Politis, Sotiriou, Doxani, Stefanidis, Zintzaras and Rachiotis2023). The phenomenon of hesitancy was further aggravated by misinformation and conflicting information given changing circumstances and scientific uncertainty (Larson, Gakidou and Murray Reference Larson, Gakidou and Murray2022; Loeb-Piltch, Harriman, Healey et al. Reference Loeb-Piltch, Harriman, Healey, Bonetti, Toffolutti, Testa, Su and Savoia2021; Ruggeri, Vanderslott, Yamada et al. Reference Ruggeri, Vanderslott, Yamada, Argyris, Većkalov, Boggio, Fallah, Stock and Hertwig2024;). Conflicting and evolving information about new vaccines made healthcare professionals hesitant about recommending some vaccines (Amin and Palter Reference Amin and Palter2021).

In this article, we aim to understand reasons for vaccine hesitancy among Greek HCWs, reasons for which the government decided to impose mandates, and ways in which the advice and decision making system could be improved in Greece and beyond. We start from the premise that vaccine hesitancy is linked to trust in political institutions and other contextual factors as mentioned above, and we engage in policy analysis to propose solutions to this policy problem (Dunn Reference Dunn1981). We adopt a specific theoretical framework of policy analysis, that is, hermeneutics policy analysis, to investigate contextual events that can help us understand the drivers of hesitancy and reconstruct the problem from the point of view of stakeholders. As we discuss herein, hermeneutics policy analysis also exposes stereotypes, especially the systemic bias and entrenched ways of thinking embedded in government action and scientific expertise, excluding alternative ways of knowing and affecting the making of decisions.

To this effect, in the first main section of this article, we discuss the Greek government’s narrative with regard to HCW mandates, and we then seek to connect it to other texts and the science advice system so as to give a hermeneutic interpretation of the Greek government’s position with regard to vaccine hesitancy and the reasons for which they decided in favor of mandates for HCWs. We also make linkages to other science advice systems in Europe to connect our findings with studies undertaken in other European countries. In the second main section of the paper, we make sense of Greek HCWs’ positions and the individual and social factors that influence their perception(s) of risk. Again, we make linkages to the general literature on hesitancy and empirical studies on drivers of HCW hesitancy, to connect our findings with studies undertaken in other European countries. Reconstructing the problem in this way is important as it gives a voice to stakeholders affected by policies and adjusts policies to make them relate to their concerns. Neglecting their point of view feeds into distrust (Hilgartner, Hurlbut and Jasanoff Reference Hilgartner, Hurlbut and Jasanoff2021) and makes compliance an unattainable goal.

Therefore, we engage in this exercise (reconstructing the point of view of regulator and regulatee) as compliance with government policies is more likely to occur if decision making systems strive to become trustworthy by giving a voice and committing to honest communication to understand the needs of the other (Ayres and Braithwaite Reference Ayres and Braithwaite1992, Braithwaite and Makkai Reference Braithwaite and Makkai1994) and, as such, adopt strategies of persuasion rather than mandates. Nevertheless, mandates can always be reserved in the background if persuasion fails (Ayres and Braithwaite Reference Ayres and Braithwaite1992; Braithwaite and Makkai Reference Braithwaite and Makkai1994) or in extreme situations where epidemiological indicators (ie mortality rates) dictate extreme solutions. We will discuss the theoretical basis of these claims in more detail in the next section of the introduction.

Hermeneutic analysis also links to specific ways to think about institutional reforms of science advice systems in Greece and beyond. Science advice systems assisted governments during the pandemic by means of making recommendations that fed into decision making concerning, for example, curfews, mask wearing, closing of schools, and vaccination mandates. The system has been criticized for being secretive and for pushing disagreement and conflict of values into the background, while governments claimed that they simply followed recommendations, that they ‘followed the science’. Essentially, governments sought to legitimize their decisions by projecting the image of the undisputed authority of science, yet critics pointed to disagreements among scientists and questioned the division between science and policy (Pamuk Reference Pamuk2021). Greece is an interesting case of a newly established science advice system with a distinctive character, making it a brilliant case study for others considering building or reforming their systems. We show in section 5 that it is based on the ‘ethical scientist’ model of science advice systems, as ethical values such as ‘protect the vulnerable’ were clearly voiced by the chief scientist, who became a trustworthy source of information as people identified with him (he was ‘one of us’). Still, as we show, in the case of HCW mandates in particular, the Greek government said they followed vaccine science and concealed scientific uncertainty and value tradeoffs. We want to argue that, if we want to design science advice systems that build trust, then institutional reforms that give a voice to those affected by policies, such as hearing (see work by Independent Sage)Footnote 1 in the UK as reviewed by McKee, Altmann, Costello et al. (Reference McKee, Altmann, Costello, Friston, Haque, Khunti, Michie, Oni, Pagel, Pillay, Reicher, Salisbury, Scally, Yates, Bauld, Bear, Drury, Parker, Phoenix, Stokoe and West2022) and science courts (Pamuk Reference Pamuk2021), need to be considered. In the final section 6, we reflect on ways to improve the system of science advice in Greece and beyond by means of considering such proposals for institutional reform.

We now consider in more depth the theoretical underpinnings of these proposals.

Theory: from policy analysis to compliance

Dunn (Reference Dunn1981, p. 35) defines policy analysis as ‘an applied social science discipline which uses multiple methods of inquiry and argument to produce and transform policy-relevant information that may be utilized in political settings to resolve policy problems.’ It follows from this definition that policy analysis needs to produce knowledge that is useful to policymakers. There are various schools of thought (for a summary and critique, see Dryzeck Reference Dryzek1982). For example, there is the policy evaluation framework that focuses on proposing solutions to a policy problem mainly by means of looking at legislative intent (ie laws and regulations, or debates in parliament regarding the professional and other obligations of HCWs). Advocacy frameworks, on the other hand, aim to promote a well-structured argument in favor of a particular position (ie to save the healthcare system). In single inquiry frameworks, the analyst chooses a theoretical framework and analysis is conducted according to criteria established by the theory (ie the morality-as-cooperation theory, according to which cooperation is morally good and defection such as refusal to vaccinate is seen as morally bad, see Korn, Böhm, Meier et al. Reference Korn, Böhm, Meier and Betsch2020). Moral philosophy generates broad principles (the ends of policy, such as ‘do no harm’). Indeed, HCWs have an ethical obligation not to harm their patients, and mandates were often legitimized on this basis. But the principle of ‘do not harm’ does not give blanket answers. Any restrictions on freedom of choice (via mandates) need to be necessary and proportionate and depend on local context and conditions. In times of crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic, increased morbidity and pressure on health system capacity, as well as lack of trust in political institutions, feed into tradeoffs that need to be investigated empirically (WHO 2021b) and take into account HCWs’ ‘burnout’ in overburdened public health systems (WHO 2020).Footnote 2 Analysts produce scenarios with harms and benefits, and as we show in later sections, the Greek Bioethics and Technoethics Committee followed this rationale. Yet, there is always a certain degree of arbitrariness regarding the choice of factors to include (or not), and the strategic interests of actors are omitted in this type of analysis. Wildavsky’s (Reference Wildavsky1979) early criticism is relevant to this type of analysis too. He pointed out that analysts far too often protect the interests of the organization they work for.

We agree with Dryzeck (Reference Dryzek1982) that all these frameworks tend to ignore an in depth analysis of the value orientations of actors, value conflicts, the constraints upon these actors, and the structure of their reasoning. In the end, policy recommendations are rejected on the grounds of their limited relevance to the situation as defined by those stakeholders, which can only be grasped if we reconstruct the problem from their point of view. In the scenarios with harms and benefits discussed above (ethical frameworks), these are described from the perspective of government. But the perspective of stakeholders is often missing. In short, the problem of vaccine hesitancy is a case of a ‘messy’ policy problem (Dryzeck Reference Dryzek1982) where different stakeholders understand it in a different way and, as such, escapes easy definitions and invites well thought policy analysis.

Hermeneutics policy analysis rests on the idea that people draw upon personal associations to enact and express civic concern with an issue (see Wynne Reference Wynne1992). The enactment of public concern involves the articulation of threats to actors’ way of life, personal values, relationships, lived experiences, broader societal values, and institutional structures (Paul et al. Reference Paul, Zimmermann, Corsico, Fiske, Geiger, Johnson, Kuiper, Lievevrouw, Marelli, Prainsack, Spahl and Hoyweghen2022; Bijker Reference Bijker2017). Public controversies may go beyond disagreements over interpretations of a single problem (correct science versus bad science). Instead, we should try to understand how governments’ and publics’ perceptions and experiences of a policy situation constitute multiple new realities or multiple problems (Dryzek Reference Dryzek1982; Hilgartner, Hurlbut and Jasanoff Reference Hilgartner, Hurlbut and Jasanoff2021; Pinch and Bijker Reference Pinch and Bijker1984; Wagenaar Reference Wagenaar2007; Yanow Reference Yanow1995). For a government, the problem of HCW vaccine hesitancy could be perceived as part of a plan to save a crumbling health system and protect vulnerable populations, or it could be perceived as part of a plan to open the economy. For HCWs, vaccine hesitancy may be perceived as a continuation of past practices (HCWs are hesitant with respect to the flu jab too) and an expression of distrust stemming from adverse work conditions in times of reduced public spending or systemic discrimination toward minorities or even distrust toward medical hierarchies given the troubling past of medicine with communities of color and the disabled. It depends on the context of complex human social, economic, and political systems (Larson, Lin and Goble Reference Larson, Lin and Goble2022) and history, but the point here is that such perceptions shape how actors construct risk and feed into HCWs’ and government’s understanding of the proper balance between professional responsibility and autonomy.

Hermeneutics inspired analysis seeks to understand actors’ different perspectives and in doing so it aspires to improve decision making by means of including a plurality of perspectives in solutions. It is necessary to demolish stereotypes, especially the systemic bias and entrenched ways of thinking embedded in government action and, importantly, scientific expertise. As such, it aligns with literature showing that experts often weigh the possible harms of certain uncertainties differently compared with the public (Jasanoff Reference Jasanoff2003). Also, omitting the inclusion of diverse points of view feeds into distrust. Hilgartner, Hurlbut and Jasanoff (Reference Hilgartner, Hurlbut and Jasanoff2021) explain that it is distrust toward elites (and the elitism of science) that provides the fertile ground for conspiracy theories.

While hermeneutics makes policy relevant to stakeholders and improves decision making by means of bringing to the fore situational knowledge of actors whose behavior we seek to regulate (Yanow Reference Yanow2007), limitations can be found in the subjective nature of reporting, lack of reproducibility, and researchers’ bias. Dryzek (Reference Dryzek1982) warns that while a certain level of advocacy on the part of the analyst is even necessary, it still needs to be acknowledged. In the present study of vaccine mandates, we acknowledge that, first, we want to find ways to increase levels of vaccination and, second, deepen democracy, the latter understood as having an epistemic component (involving a variety of different sources of knowledge) and aiming to improving the quality of decisions and build trust. Despite the limitations we mentioned, the more important merits of hermeneutics policy analysis can be found in that it presents us with the work required for building trust and in this way ensure compliance.

Compliance and trust

Trust in government is strongly associated with vaccine acceptance, and it can contribute to compliance with policies (Lazarus, Ratzan, Palayew et al. Reference Lazarus, Ratzan, Palayew, Gostin, Larson, Rabin, Kimball and El-Mohandes2021). It is known from previous disease outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) and Ebola, that trustworthiness of information sources is of major importance so that people comply with public policies such as vaccination (ibid). The notion of trustworthiness needs to be unpacked to understand these claims. Scheinerman (Reference Scheinerman2023) notes that at the heart of trustworthiness is the uneven power relationship between public institutions and trustees: ‘The trusted, then, is expected to determine what is good or not good for the trustee, thus holding power over them…. To trust then is to truly believe that the trusted has the trustee’s welfare at heart when making decisions.’ Braithwaite (Reference Braithwaite2020) also notes that ‘trust.[is] the expectation that others will care for you…. leaving ourselves or others open to exploitation through privileging trust’. Distrust may manifest itself with active resistance or apathy, but the key message is that, given uneven power relations between trusted and trustees, political institutions need to nurture trust rather than take it for granted. Especially in cases where past exploitation and systemic injustice have resulted in violation of trust toward the medical or political establishment (Scheinerman Reference Scheinerman2023), governments ‘should be using different trust building strategies for different institutional contexts and for different groups of people’ (Brathwaite Reference Braithwaite2020), so that people subject to regulation are persuaded that policies are in the public’s best interest (Job and Reinhart Reference Job and Reinhart2003). Importantly, when governments act with distrust toward citizens, people tend to react with distrust and do not comply (Braithwaite and Makkai Reference Braithwaite and Makkai1994).

During the Covid-19 pandemic, governments operated under assumptions that jeopardized building trust. Citizens were expected to accept the law, and if not, they deserved punishment. This approach was also based on several dubious assumptions about social psychology. For example, Drury, Carter, Ntontis et al. (Reference Drury, Carter, Ntontis and Guven2020) challenge the invocation of folk psychology assumptions according to which the public panics and cannot act responsibly. They also question the notion of public fatigue (ie with lockdowns and other restrictions) that was often invoked during the pandemic to legitimize coercion and withholding information from the public. In the same spirit, the Independent Sage in the UK criticized the government for blaming the public for non-adherence and threatening with fines and other penalties to ensure compliance. McKee, Altmann, Costello et al. (Reference McKee, Altmann, Costello, Friston, Haque, Khunti, Michie, Oni, Pagel, Pillay, Reicher, Salisbury, Scally, Yates, Bauld, Bear, Drury, Parker, Phoenix, Stokoe and West2022) noted that ‘research on emergencies and disasters shows that people affected characteristically come together to support each other and this forms the basis of collective resilience’ (p. 241).

If we start from a different premise, notably that people do not comply when they distrust government’s intentions, then reasons for resisting government policies may also be found in cognitive dissonance theories, which affirm that, when there is lack of clear communication or an abundance of conflicting and rapidly changing information, as happened so many times during Covid-19, people tend to believe information that confirms previous beliefs. Bardosh, Figueiredo, Gur-Arie et al. (Reference Bardosh, Figueiredo, Gur-Arie, Jamrozik, Doidge, Lemmens, Keshavjee, Graham and Baral2022) explain that this created psychological stress leading the public to doubt the rationale and proportionality of restrictive measures. Given these circumstances, behavioral psychologists suggested that mandates feed into distrust and resistance, and literature reviewed by Drury, Carter, Ntontis et al. (Reference Drury, Carter, Ntontis and Guven2020) found that compulsory Covid-19 vaccination would likely increase levels of anger in those already mistrustful of government, and do little to persuade the already reluctant. In fact, mandates may even decrease acceptance of future voluntary vaccines such as the influenza and chickenpox vaccines (the authors refer in detail to two experiments conducted in Germany and the USA).

Solutions

Having established that mandates aggravate distrust, we turn to solutions, ways to build trust so that people are persuaded to follow government policies. Drury et al. (Reference Drury, Carter, Ntontis and Guven2020) explain that ‘when the source is seen as one of “us”, we are more likely to see their messaging and behavior as relevant, more likely to listen, and more likely to follow their instructions or their example. This has been demonstrated in both “normal” life and in relation to the Covid-19 pandemic.’ This position aligns with models of science advice such as ‘ethical scientist’, as we discuss in section 5. It also resonates with attempts to inform publics by respected people in their communities (ie by means of hosting information sessions in hospitals by acclaimed physicians), and with studies showing that people form beliefs in their social circle in conversation with esteemed and trusted peers (see section 5). But this approach has limitations. It fails to acknowledge the conflict of values that makes decisions hard. It does not seek to engage stakeholders or elicit situational knowledge of actors and give a voice to improve decisions and build trust. Yet, hermeneutics analysis places high priority on engaging with those affected by policy, drawing on experience with co-production of solutions (Turk, Durrance-Bagale, Han et al. Reference Turk, Durrance-Bagale, Han, Bell, Rajan, Lota, Ochu, Porras, Mishra, Frumence, McKee and Legido-Quigley2021). This can be done by interviews and analysis of texts, a process that we explain in detail in the next section on methodology. The analysis of the present article is based on this approach.

But we could also make analogies with more general proposals regarding possible ways to reform science advice systems to make them more inclusive, although we acknowledge that modifying the system to address the case of vaccine hesitancy and the question of mandates for HCWs is no easy feat. Still, various more general proposals have been made recently regarding ways to improve science advice systems. For example, the UK Independent Sage proposed involving rigorous evaluation and integration of knowledge from multiple disciplines and perspectives to contribute technical expertise, hearings to disseminate information to citizens and to encourage the articulation of their concerns, but also to incorporate their situational knowledge (McKee, Altmann, Costello et al. Reference McKee, Altmann, Costello, Friston, Haque, Khunti, Michie, Oni, Pagel, Pillay, Reicher, Salisbury, Scally, Yates, Bauld, Bear, Drury, Parker, Phoenix, Stokoe and West2022). In her recent book, Pamuk (Reference Pamuk2021) makes the case for ‘science courts’, in which laypeople question experts. This proposal echoes wider concerns in bioethics (see, for example, Scheinerman Reference Scheinerman2023) arguing for public engagement through citizen juries by providing space for active listening, reflection, and engaging with the lived experiences of participants (Ercan et al. Reference Ercan, Durnová, Loeber and Wagenaar2020; Ercan and Gagnon Reference Ercan and Gagnon2014; Forester Reference Forester1999). We reflect on these approaches in section 6.

Method/Methodology

In this article, we deploy the methodological tools of hermeneutic analysis to make sense of both HCWs’ and the Greek government’s positions. Following Lejano (Reference Lejano2006) and Lejano and Leong (Reference Lejano and Leong2012), we argue that hermeneutics offers novel tools to policy analysts, to understand policy controversies in a way that takes into account the diversity of perspectives, which in turn feeds into better public policy responses (Lejano Reference Lejano2006; Lejano and Leong Reference Lejano and Leong2012). Constructing actors’ narratives is key. According to Fisher (Reference Fisher1985), to narrate, we must be capable of apprehending and interpreting the world of human activities as a story, with content, involving different actors, and to grasp the events in terms of patterns. Yet, hermeneutics requires that we go beyond speakers’ utterances. Texts such as interviews and archives of press conferences provide evidence that can be further analyzed to understand meaning particular to a policy problem that remains concealed or misrepresented. For Gadamer (Reference Gadamer2004), the interpreter needs to re-awaken the text so that they truly make sense of what has been written. Yet, the analyst needs to understand the hermeneutic circle (Gadamer Reference Gadamer2004). Beyond the narrator’s intentions and to understand the meaning of the text itself, we need to follow cues or references as they take us away to other distant yet related texts (Lejano and Leong Reference Lejano and Leong2012). This can be past government reports on related issues, professional practices, codes of conduct, or even objects such as buildings or architecture. The text can also be linked to institutions; they have narratives too. Following Hilgartner (Reference Hilgartner2000), we see statements and opinions as reinforcing or challenging the system of science advice put in place to build credibility and thereby structuring relations between experts and their audiences.

We used thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006) and situational analysis (Clarke, Friese and Washburn Reference Clarke, Friese and Washburn2018) to make sense of the regular weekly press conferences held by the government during the pandemic. These press conferences were televised, and transcripts are stored on official government sites, offering us a unique opportunity to use content analysis to derive themes and the government’s primary narrative. For Braun and Clark (Reference Braun and Clarke2006), deriving themes requires first familiarization with the data, then coding, followed by generation, reviewing, and naming of themes. Familiarization is achieved by reading through the material various times, and coding involves organizing the data into categories (ie information about mortality rates, healthcare system capacity and virus mutations, vaccine recommendations and mandates, regulatory approvals of vaccines, and reasons for which citizens should be vaccinated). Then, we started identifying recurring themes that cut across these codes. Themes are broader than codes in the sense that they combine several codes and require interpretation of the codes, as themes present a pattern across the dataset. As such, this requires moving back and forth between the codes in search of commonalities. We discuss themes in the following sections, as well as subthemes that come under broad themes and help further organize their meaning.

After putting together the main narrative construction based on primary text, which is based on various themes and subthemes (for example, HCWs transmit the virus to patients and colleagues), we then find links to other ‘distant’ texts that help elucidate meaning, such as reports showing that many HCWs did not even vaccinate against the flu (something that had already caught the attention of the Ministry of Health before Covid-19) and reports showing that the public health system is on the brink of collapse and it is still running as a result of the heroic attendance of HCWs. Looking for ‘distant’ texts is not an arbitrary exercise. We looked specifically at outputs of the Ministry of Health that concerned broader vaccination policies as well as reports and literature that concerned working conditions at hospitals since the beginning of the financial crisis in 2010, as public health system capacity is recognized as a major factor influencing policy during health crises.

Moreover, we conducted 74 interviews with hesitant HCWs. We divided them into two groups. Τhe first group consisted of 36 unvaccinated HCWs who were suspended. The second group consisted of 38 vaccinated HCWs who were vaccinated after mandates were announced.Footnote 3 Sixty-seven people came from Athens, and seven from three provincial cities in Greece. Although we consider our sample to be adequate, we acknowledge a limitation in the fact that most of our interviewees came from Athens. The interviews were semistructured and lasted from 15 min to 1 h. HCWs were informed in advance of the purpose of the study and that the interview would be recorded, and they signed an informed consent document. Before the interview, they were given a detailed explanation of how anonymity is preserved and personal data protected, to create a climate of trust. Arranging interviews was a painstaking process, as hesitant healthcare workers were very cautious and suspicious. The first participants came from professional contacts of one author. Then, the participants put the researcher in contact with their colleagues in other health units. Moreover, E.C. attended a meeting of the coordinating body of HCWs against mandates to inform them of the research and ask permission to forward the request for interviews to members. E.C. also attended various events organized by them so as to inform HCWs about the study and request an interview. We asked questions such as reasons for hesitancy, reasons for vaccinating, attitudes toward the flu vaccine, whether they take protective measures, if they feel at risk, if they trust science advisors, how they were informed about Covid-19, and who should be vaccinated. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis to construct the primary narrative of HCWs’ positions. We compared the two groups (those unvaccinated and those vaccinated after mandates were announced), and we found various differences (for example in attitudes toward the flu vaccine and reasons for vaccinating). After putting together the main narrative construction based on various themes and subthemes (for example, bodily autonomy trumps public health, as both vaccinated and unvaccinated people transmit the virus), we then deployed hermeneutic analysis to link statements to distant texts such as reports on natural immunity and working conditions inside hospitals in debt-stricken Greece. Finally, the two coauthors discussed overall coherence and whether it feeds into a convincing storyline. The whole process took place over 14 months, from November 2022 to December 2023. As a last note, we add that thematic analysis tells a story, and as such confirmation bias looms large. We reflected on the bias of our own interpretations. We are in favor of persuasion (rather than mandates), and we want a system of science advice that is participatory, yet we recognize that persuasion is not always the solution and mandates may indeed be necessitated depending on circumstances (ie high mortality rates and speed of transmission).

Primary interpretation of the position of the Greek government

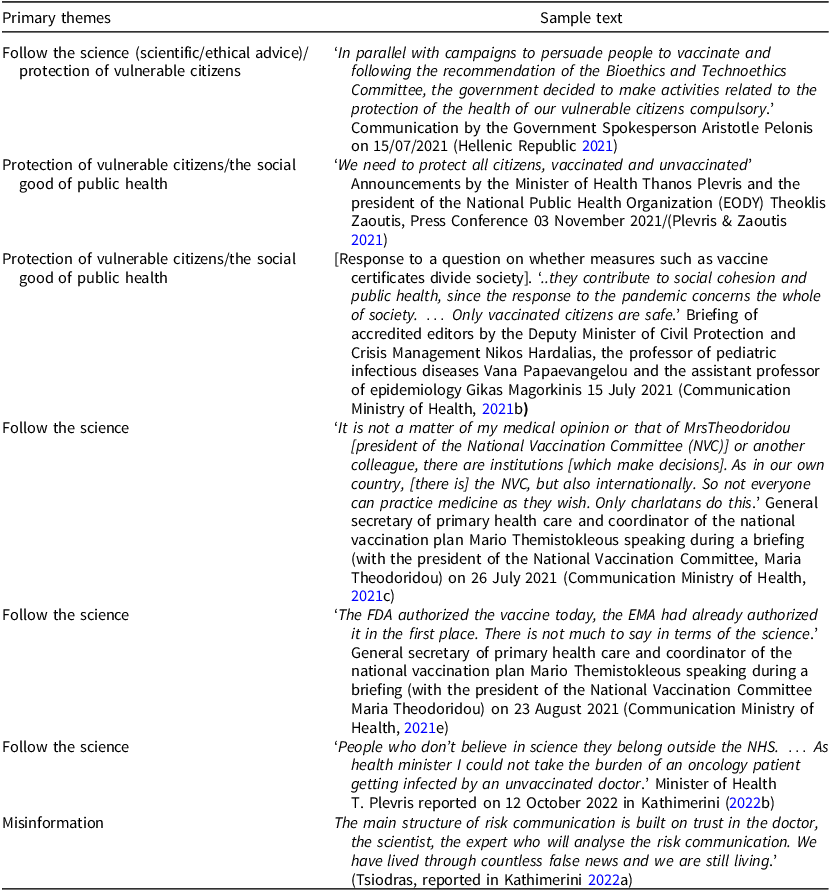

The national vaccination plan was announced on 18 November 2020. The president (professor of pediatrics Maria Theodoridou) of the Greek National Vaccination Committee (NVC) together with other members of the NVC, members of the National Experts Committee on Public Health (NECPH), and the General Secretary of Primary Health started presenting briefings to an audience of journalists two or three times a week on national television. These briefings were dedicated to informing the public about the vaccination rollout, prioritization, and international or national developments. It was in July 2021 that the Greek government announced mandates for unvaccinated HCWs to commence on 1 September 2021, at a time when the number of Covid-19 patients in hospital had started to rise. During these briefings (before and after the introduction of mandates for HCWs), experts and ministers presented information on the percentage of vaccinated citizens, numbers of deaths, numbers of people infected with the virus, numbers of intensive care unit (ICU) beds, and pressure on the public health system. Thematic analysis of briefings and statements of members of expert committees and ministers in the popular press reveals a number of recurring themes with respect to unvaccinated HCWs. Following Lejano and Leong (Reference Lejano and Leong2012), we summarize recurring themes in Table 1 and we provide excerpts that illustrate the contents of the themes. These themes are useful in that they help us construct the primary narrative of the government.

Table 1. Government narrative

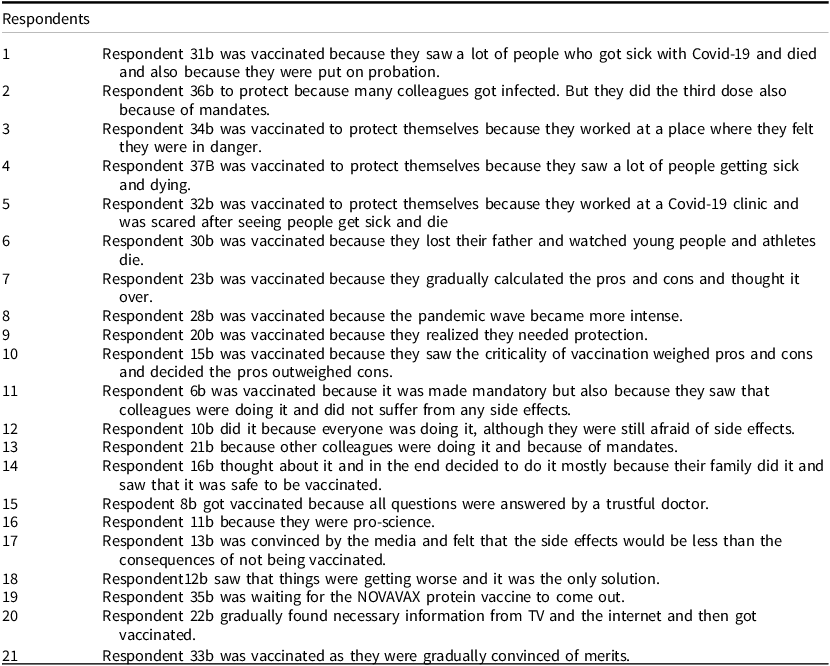

Table 2. Reasons why some respondents changed their mind and underwent vaccination

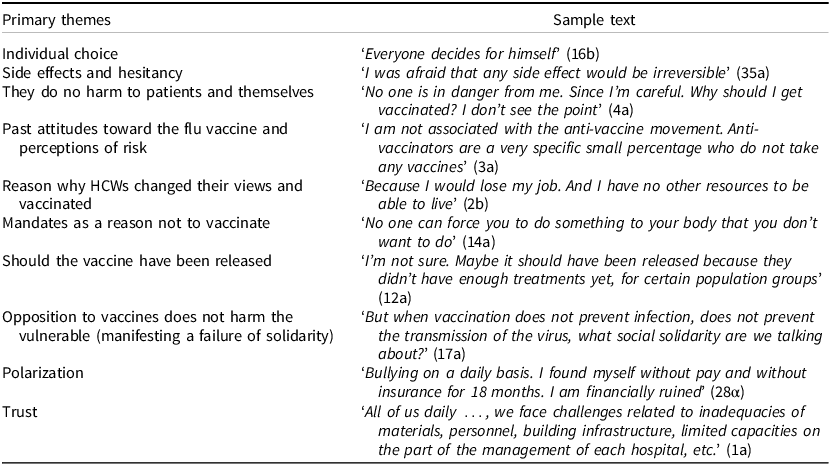

Table 3. HCWs’ narrative

In our analysis, we found three main themes: follow the science (experts’ and doctors’ opinions), protect the social good of public health/vulnerable populations, and combat misinformation. We identify various recurring subthemes, such as unvaccinated HCWs transmit the virus, HCWs do not respect established (regulatory, scientific, and professional) hierarchies, trust the experts and science advice institutions, and pressure on the public health system. The initial narrative of the policy issue is constructed from thematic analysis, but what about meanings that go beyond these declarations? As Lejano and Leong (Reference Lejano and Leong2012) ask, do these statements mean what they say or are issues pushed into the background? In our case, one more reason to ask these questions and try to look beyond the primary text lies in the government’s assertion that they followed the recommendations of the National Bioethics and Techno-ethics committee (BTC)Footnote 4. Yet, this is partly accurate.

True, the government asked the BTC to produce a recommendation. The BTC is a committee staffed with internationally acclaimed ethicists, whose mission as stated on their website is ‘public dialogue to address the need to develop technology in line with societal needs’. The question they were asked to answer concerned whether it is morally acceptable to introduce mandates for unvaccinated HCWs since the pandemic continues to threaten and cost human lives and since there are approved vaccines that are safe and effective. We note that, first, they had to respond to a very specific question framed in a very particular way by the government. Second, safety concerns or perceptions of safety were not part of what the specific committee had to give advice on; the government only wanted to know more about the ethical and legal aspects of mandates. Third, the BTC was asked to give ethical advice and not engage in a broad analysis of democratic purposes and goals. Considering the above limitations, the BTC still crafted a careful analysis that considered the conflict between different values (autonomy, duty to protect the vulnerable, and the principle of ‘do no harm’) and noted that compulsory vaccination is both morally and legally controversial. It is notable (as good practice) that the BTC had previously organized meetings with stakeholders and various healthcare worker associations (ie doctors, nurses, and midwives) to elicit their views, following the European Groups of Ethics’ and other ethics committees’ practice around the world. The BTC explained that any balancing between conflicting values needs to be conducted in the light of evidence with regard to effectiveness and safety, the infectiousness rate in the general population, the number of cases, the occupancy rate of ICU beds, the vaccination coverage rate in the general population, and cited evidence showing that a single dose of some Covid-19 vaccines reduces transmission in the close environment by 38–49% and that viral load is reduced in vaccinated individuals 14 days after the first dose, suggesting lower transmission. They then recommended an escalating approach (including education and information campaigns) with mandates being the last resort measure. It is notable that they published their opinion on their website along with the names of those who participated in drafting the opinion, in a laudable effort to be transparent, while very few other advisory committees around the world engaged in similar open practices (see the discussion by McKee, Altmann, Costello et al. Reference McKee, Altmann, Costello, Friston, Haque, Khunti, Michie, Oni, Pagel, Pillay, Reicher, Salisbury, Scally, Yates, Bauld, Bear, Drury, Parker, Phoenix, Stokoe and West2022).

We mentioned above that it was partly true that the government followed the advice of the BTC. Indeed, what the government took from this report is that controversial mandates can be lawful (as long as they apply to particular groups of people and for a particular period of time in light of the principle of proportionality). Nowhere in the televised briefings we discussed above was there explicit mention of a conflict of values making decisions hard. Moreover, the advice was sought narrowly on ethical and legal balancing, while dissenting views and unvaccinated healthcare workers’ opinions were nowhere present in consultations.

Hermeneutic interpretation: hesitancy toward the flu vaccine and presenteeism

The previous analysis allowed us to reconstruct the primary narrative upon which mandates have been largely based. But we need to also reveal the hidden issues not addressed or stressed in the primary interpretation. Hermeneutics helps us engage in this task. Following Lejano and Leong (Reference Lejano and Leong2012), in our thematic analysis of press conferences on the national vaccination plan, we also found references that stand out and call for a deeper analysis to understand their meaning. This can be undertaken by means of finding links with other policy texts drafted in the past on issues loosely related to Covid-19 and vaccine hesitancy. Indeed, in the communications, we found that while one member of the National Vaccination Committee (NVC) said that we need to ‘make an appeal’ to HCWs, the President of the NVC used strong language: ‘Everyone’s right is to be vaccinated or not vaccinated except for health professionals.’ Moreover, we found that two members stressed the weakening of the public health system as a crucial factor of any decision. This is a consequentialist approach (rather than one that stresses duties and professional responsibility) and provides crucial context to understand decisions. We need to better understand these statements, and to this effect we need to find links with other texts. This is not an arbitrary exercise. We chose to look for links with government policy papers on broader vaccine policy to understand if mandates are part of broader policy, as well as with literature that discussed financial pressure on the Greek public health system, especially after the beginning of the Greek financial crisis, which put to test the political system at large. Moreover, public health system capacity is recognized as a major factor influencing policy during a health crisis.

A crucial subtext (text connected to the primary text) concerns past attitudes of HCWs with respect to the flu jab. A second subtext refers to the daunting reality of the Greek public health system being on the verge of collapse. To begin with the first, for the first time in 2019, the Ministry of Health decided to give an award to health units that achieved the highest vaccination coverage rates nationwide and established the Coordinating Committee on Seasonal Flu Vaccination for Health Professionals to identify, plan, and implement best practices to increase the vaccination coverage of health service personnel against influenza. In a separate report dedicated to vaccination against seasonal flu by the Ministry of Health (EODY 2019), it is stated that healthcare settings have a duty to protect their patients and staff and note that a significant percentage of HCWs remain unvaccinated (in Greece, 41.6% of HCWs remained unvaccinated against seasonal flu, see Alasmari, Larson and Karafillakis Reference Alasmari, Larson and Karafillakis2022) and vaccination of HCWs needs to be secured. The document mentions that vaccination coverage of healthcare workers remains low globally, with the exception of the USA, where mandatory influenza vaccination policies have been implemented over the last decade with excellent results.

In a different document released by the Department for Legislative Initiative, Parliamentary Scrutiny, and Codification of the Ministry of Health published on 30 April 2019 in response to a question (no. 5641/14, February 2019) submitted to the Greek parliament by MP Mr. K. Bargiotas on the need for mandatory vaccination of health workers, the Ministry of Health answered that

‘The issue of mandatory vaccination of health service staff has been repeatedly discussed by both the National Vaccination Committee of the Ministry of Health and the Coordination Committee for the Vaccination of Health Professionals for Seasonal Influenza. Both Committees consider that there is a need to develop a legal/institutional framework for vaccination of health service personnel and that mandatory vaccination of health service personnel could be a requirement for enrolment in health schools or for employment in the health system (acceptance of mandatory vaccination upon recruitment into the health system)’ (Ministry of Health 2019).

We see that both the Ministry of Health and the National Vaccination Committee were already concerned with the problem of unvaccinated HCWs prior to the pandemic and they were already considering legislation making vaccination against seasonal flu mandatory or de facto mandatory by means of making it a requirement to attend university and seek employment. A publication (with the lead author employed by the Directorate of Research, Studies, and Documentation, Greek National Public Health Organization) sheds further light on the reasons for which unvaccinated HCWs pose a threat (Maltezou et al. Reference Maltezou, Dounias, Rapisarda and Ledda2022). The authors explain that HCWs have long been recognized as a high-risk group both for acquisition of several vaccine-preventable diseases (such as the flu or childhood disease such as measles) and for transmission of viruses to patients (they cite various studies from around the world, including the case of a misdiagnosed physician with measles who was traced as the source of an outbreak of 35 cases at an Italian hospital a few years ago). Worse, the authors refer to ‘presenteeism’, defined as working while being ill, which, they argue is common among HCWs, even in high-risk settings. They refer to an influenza outbreak that occurred in an oncology unit where two out of three infected HCWs continued to work despite being symptomatic. The reasons were ‘sense of duty’ (56%) and ‘viewing their illness as too minor to pose risk to others’ (44%). The authors further cite a survey from the USA that found that 183 out of 414 (41.4%) HCWs with influenza or similar illness continued to work for a median of 3 days, giving reasons such as ‘still being able to perform job duties’ and ‘not feeling bad enough to miss work’. Finally, they cite a survey, again from the USA, showing that 92% of HCWs with influenza worked while ill, even those working in a transplant unit. In a different study, with the same lead author (employed by the Directorate of Research, Studies, and Documentation, Greek National Public Health Organization), the authors estimated costs associated with the first wave of Covid-19 in Greece as a result of HCWs falling ill, amounting to €1.73 million. They further note that 15% of HCWs with Covid-19 in their study reported presenteeism (for a mean duration of 2.2 days) (Maltezou et al. Reference Maltezou, Giannouchos, Pavli, Tsonou, Dedoukou, Tseroni, Papadima, Hatzigeorgiou, Sipsas and Souliotis2021).

These numbers make more sense if we also account for the daunting reality of a public health system on the brick of collapse. The following long excerpt is illustrative:

‘it is striking that Greece with the highest per capita rate of licensed specialist physicians among EU Member States (6.2 per 1000 population) has the fourth lowest rate of health personnel employed in hospitals…. The imposed freeze on hiring drove many doctors to seek work abroad or to private practice. The Greek hospital-based doctors work daily under ‘emergency’ conditions …. while this might be seen as extraordinary for other countries, it is ‘normal’ in Greece, perhaps placing the medical staff in Greece in a better position in the current pandemic crisis. Their experience of working under strenuous and very difficult conditions, with low pay and insufficient resources at their disposal, ironically might have contributed to effective management and the successful containment of cases, in conjunction with the imposed national lockdown’ (Giannopoulou & Tsobanoglou Reference Giannopoulou and Tsobanoglou2020).

The above texts show that an important factor that influenced the decision to impose mandates concerned the need to keep the national health service from breaking down and protect vulnerable populations. Mandates also made sense considering previous recommendations of the vaccination committee with regard to this matter. Statistics about HCWs’ attitudes in relation to other vaccines (flu) and presenteeism are crucial, as HCWs are defined as a high-risk group for both transmitting and catching the virus.

But this discussion would be incomplete without accounting for the key role played in the overall handling of the pandemic by Prof. Tsiodras and the newly established National Experts Committee on Public Health (NECPH). A key theme that emerged in our thematic analysis is the ‘protection of vulnerable’, and references such as ‘We need to protect all citizens, vaccinated and unvaccinated’ (Plevris and Zaoutis. Reference Plevris and Zaoutis2021) were common. In the following section, we discuss subtexts that further elucidate this theme.

Protect the vulnerable

One day before the first officially reported case of Covid-19 in Greece, the chief science advisor of the Greek government and member of the NVC, Prof. Tsiodras, stated that the virus poses a risk for the elderly and that it behaves like a pandemic (Tsiodras Reference Tsiodras2021), which led to legislation on Covid-19 in Greece (Government Gazette 2020). Weeks before other countries, Greece adopted draconian measures and a full lockdown, which was later hailed as having averted innumerable deaths. During this first phase, the government raised their percentage of popularity.

‘I have been told by someone I know, a very important scientist, one of the world-renowned people, that we make too much fuss about a few old and chronically ill citizens. The answer I give internally within myself and I leave it to your judgment is that the miracle of medical science in 2020 is the prolongation of survival of these individuals, many of whom are our mothers and fathers, grandmothers and grandfathers. The answer is that we honor everyone, we respect everyone, we protect everyone, but most of all we protect them. We cannot exist or have an identity without them’ (Communication Ministry of Health 2020)

There is indeed a high percentage of elderly people in Greece, a society that values the elderly, who are also in close contact with their children and grandchildren. Tsiodras gained the trust of the public, a modest family man, father of seven children, and 94% thought of him positively in April 2020. The New York Times hailed him as a hero, and France’s Le Figaro said he is the reason why Greece avoided many more deaths. In an interview, the Israeli historian and philosopher Yuval Noah Harari said: ‘If I had to choose between Greece and the United States for who should be leading the world now, giving us a plan of action, I would definitely choose Greece.’ New York Times reported interviewees saying that ‘He’s one of us.’ ‘He’s humble, modest and caring, but he’s also undeniably a top expert’ (Gridneff 2020). Prof Tsiodras can be seen as a case of ‘ethical scientist’ (see the discussion by Douglas Reference Douglas2009 contrasting ethical with neutral advice), and he set the pace for a type of science advice particular to Greece that we will term the ‘view from inside’ (for styles of science advice communication generally, see Jasanoff Reference Jasanoff, Camic, Gross and Lamont2011), putting compassion and protection of vulnerable populations squarely into statements about what needs to be done. Apparently, his voice resonated with a society where suffering during the economic crisis in Greece encouraged solidarity (Knight Reference Κnight2015).

He stopped being the spokesperson in press conferences in May 2020, and those who took his place (as spokespersons) never matched his popularity but retained the emphasis on ‘protect the vulnerable and the public health system’. With the advent of subsequent waves of the pandemic (and a rise in the number of deaths) and with the proliferation of conflicting information about vaccines and the usefulness of confinement measures alike, support for government measures (always claiming that they followed the science) dropped. Yet facts about the public health system and the tipping point of breaking down involve normative judgments such as how a particular society is expected to tolerate the suffering of vulnerable populations such as the elderly, the importance we attach to the value of public health system and what it can deliver in times of crisis (solidarity), and freedom of choice from medical paternalism (Pamuk Reference Pamuk2021; Reference Pamuk2022). But, tradeoffs between competing values were not publicly discussed. On 15 October 2022, Prof. Tsiodras commented on vaccination policy: ‘Risk communication needs experts, a team, collaboration, detecting what your audience thinks (public perception). Something we failed at. We failed miserably […] The main structure of risk communication is built on trust in the doctor, the scientist, the expert who will analyse the risk communication. We have lived through countless false news and we are still living.’ (Kathimerini 2022a).

We want to argue that the problem can be approached in a different way. It is possible that HCWs perceive risk in drastically different ways from experts, as we will discuss in detail in the following section (on this point more generally, see Larson, Lin and Goble Reference Larson, Lin and Goble2022). Also, contextual factors need to be considered. The austerity measures during the Greek financial crisis (the first austerity measures agreed in 2010) resulted in a 15% cut in the salary of health workers, a 10% cut in pensions, the abolition of benefits, and an increase in the retirement age from 65 to 67 years. It is worth noting that health workers in Greece before the financial crisis had the lowest salaries in the European Union. With the financial crisis, salaries were further reduced and benefits abolished. Horizontal cuts were implemented through tax increases, cuts through the single payroll for all civil servants, and reductions in special payrolls for doctors. HCWs perceived salary reductions combined with increasing workload and unsuccessful reforms as an offense to their professional value and social role (Kerasidou et al. Reference Kerasidou, Kingori and Legido-Quigley2016). In addition, no performance-based productivity bonuses were given, and no replacement of retired staff was provided, as it was decided to appoint only one person for every five retired staff. Several health workers retired after the memorandum to secure a larger pension. This worsened the problem of an understaffed hospital system, bearing in mind that there was a shortage of staff in the health sector even before the financial crisis (Economou et al. Reference Economou, Kaitelidou, Kentikelenis, Maresso and Sissouras2015). During the Covid-19 pandemic, the long-term pathologies of the health system (mismanagement and inefficiency) negatively affected workers, leading to burnout and lack of job satisfaction. Nurses had the highest burnout because of increased workload, low pay, and lack of autonomy (Galanis, Katsiroumpa, Vraka et al. Reference Galanis, Katsiroumpa, Vraka, Siskou, Konstantakopoulou, Katsoulas and Kaitelidou2023a). Staff shortages reinforced the intention to leave work, further exacerbating understaffing. During the pandemic, the phenomenon of silent resignation occurred. Since finding a job was difficult, workers did not quit their jobs but continued to work with lower performance. Nurses chose quiet resignation more than other health workers (Galanis, Katsiroumpa, Vraka et al. Reference Galanis, Katsiroumpa, Vraka, Siskou, Konstantakopoulou, Katsoulas and Kaitelidou2023a). It is noteworthy that, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), when the pandemic broke out, Greece had the lowest ratio of nurses and general practitioners per 1000 inhabitants in Europe. The ratio was 3.4 nurses and 0.44 physicians per 1000 inhabitants. In Germany, for example, this ratio is 11.79 nurses and 1 physician per 1000 inhabitants. HCWs worked in extreme conditions before and during the pandemic, affecting trust toward the government and political institutions. During the pandemic, as admissions increased dramatically, the health system was placed under extreme pressure and staff were required to work in extremely difficult working conditions in a high-risk environment (Galanis, Katsiroumpa, Vraka et al. Reference Galanis, Katsiroumpa, Vraka, Siskou, Konstantakopoulou, Κatsoulas, Moisoglou, Gallos and Kaitelidou2023b). We turn to consider these aspects (ie perceptions of risk and trust) now.

The primary narrative of healthcare workers’ positions

We conducted 36 interviews with unvaccinated (suspended) HCWs and 38 with HCWs who underwent vaccination after the announcement of mandates. The primary narrative emerging from the interviews with HCWs was that mandates conflicted with the right to self-determination and freedom of choice. Vaccination is a medical procedure, and HCWs needed to give their consent. Although, in principle, public health reasons could trump individual rights, they thought that public health reasons did not justify mandates in their specific case. The reason, according to them, is that they were taking extra care not to transmit the virus to patients, colleagues, and their environment. Moreover, they referred to research showing that vaccinated and unvaccinated people carry a similar viral load, so self-testing two or three times a week would be a way to address concerns. They emphasized that they do not violate professional codes of conduct (do not harm) and did not fail to show social solidarity with the public health system, exactly because they took care not to transmit the virus and they were willing to do frequent self-testing. Moreover, they had doubts about vaccine safety, and they attributed their hesitancy to fear of side-effects (although they explicitly said that they do not identify with the antivaccine movement in general). For some of them, coercion strengthened their hesitancy, while others said that they vaccinated so that they did not lose their jobs. Finally, lack of trust in the political system strengthened hesitancy. Lack of trust was further strengthened as they felt they belong to a professional group that was stigmatized and faced social exclusion in a society divided into the vaccinated and unvaccinated. In more detail, we found the following themes:

Individual choice

Interviewees in both groups (A and B) said that they were against compulsory vaccination, because it is up to individuals to decide for themselves and their body. Similarly, in group B, interviewees said that they were forced to vaccinate yet health professionals have every right to decide not to be vaccinated (with only one exception (interviewee 20b), who had changed their mind completely and was even in favor of mandates).

Side effects and hesitancy

Groups A and B expressed similar fears with regard to the reasons for which they were hesitant. All questioned the safety of the vaccine and the authorization procedure. They were concerned about side effects, and they said that this was a new vaccine that was authorized under emergency procedures; it had not completed clinical trials, and as such they considered it to be at an experimental stage.Footnote 5 Some mentioned fear of the unknownFootnote 6 as well as doubts about efficacy.Footnote 7 The overwhelming majority said that they feared long-term side effects, while some were also concerned about short-term side effects.Footnote 8

Some interviewees mentioned additional reasons such as health problems that did not allow them to get vaccinated (rheumatoid arthritis, kidney problems, allergies, autoimmune diseases, deafness, phospholipid syndrome, and psoriasis).Footnote 9 Others said that they did not belong to a vulnerable group,Footnote 10 they did not get sick easily, and they avoided taking medication in general.Footnote 11

They do no harm to patients and themselves

They pressed the point that they know how to protect themselves, patients, and others. We asked group B specifically about protective measures, and they said that they were wearing masksFootnote 12 and gloves,Footnote 13 hand washing,Footnote 14 limiting contacts,Footnote 15 avoiding crowded places (19b), keeping distance,Footnote 16 avoiding indoor spaces (11b and 17b), using antisepticFootnote 17 and disinfectants,Footnote 18 undergoing regular rapid tests (13b and 28b), putting clothes in a special bin and leaving shoes outside the house (37b), not hugging and kissing people (37b), exercising, and maintaining good nutrition and avoiding stress (18b). Respondent 8b decided to take their family away and stayed alone during the quarantine period. Respondents 12b and 32b did not visit their extended family. Respondent 32b did not even see friends, to protect them. Respondent 28b did not travel on public transport. Respondent 26b did not come into contact with vulnerable groups or oncology patients.

Past attitudes toward the flu vaccine and perceptions of risk

The attitude of both groups towards vaccination before the pandemic was generally positive.

‘I am not associated with the anti-vaccine movement. Anti-vaccinators are a very specific small percentage who do not take any vaccines.’ (respondent 3a)

HCWs said that they and their children are vaccinated against childhood illnesses.Footnote 19 However, there is a significant difference between the two groups regarding the influenza vaccine. In group A, the overwhelming majority were against the flu vaccine too. In contrast, in group B, interviewees were divided, although more than half of our interviewees said that they would vaccinate against seasonal flu.Footnote 20 Those who said that they did not need the flu jab offered reasons such as not belonging to a vulnerable group (it is a vaccine for older people) and did not get sick easily. They also said that the flu vaccine is not effective as the virus mutates.

Reasons why HCWs changed their views and underwent vaccination

Inquiring into the reasons why people change their perceptions of risk is crucial. Out of 38 interviewees in group B, 21 said that they gradually changed their mind in favor of Covid-19 vaccination. They started feeling fearful of contracting Covid-19 (32b) and decided that they had to be vaccinated to be protected.Footnote 21 They also said that, during work at the hospital, they saw many people getting sick from Covid-19Footnote 22 and dying.Footnote 23 One interviewee said that they underwent vaccination because they lost their father to Covid-19. Others (10b and 21b) reported that they changed their minds because several of their colleagues and relatives were vaccinated (16b) and found the vaccine to be safe as there were no significant side effects (6b and 16b).

The remaining 17 of the 38 interviewees in group BFootnote 24 said that the only reason why they decided to get vaccinated was to avoid losing their job.Footnote 25 ‘Because I would lose my job. And I have no other resources to be able to live’ (2b).

Mandates as a reason not to vaccinate

According to group A, vaccine mandates had the opposite effect and somehow reinforced their decision not to vaccinate. For them, freedom meant being able to express their opinion without fear of consequences and to decide for themselves about their own body. They said they were fighting for freedom, free choice, and self-determination. They needed more time to be able to decide and more information.Footnote 26

Should the vaccine have been released?

There were differences between groups A and B in this regard. Generally, group B was more supportive, while group A was more negative. We asked group A if they thought that the vaccine should have been released, and some said that they were not sure and expressed the opinion that perhaps it should have been released for vulnerable groups.Footnote 27 ‘I’m not sure. Maybe it should have been released because they didn’t have enough treatments yet, for certain population groups’ (12a). Others (15a and 16a) argued that it should have been released but with full transparency and after all studies were made public. However, there were also those who were less moderateFootnote 28 and argued that the vaccine should not be used in any population group because it is at an experimental stage.

In contrast, in group B, the majority answered that the vaccine should have been released.Footnote 29 Some were not sure,Footnote 30 while some argued that it should have been released but not so quickly.Footnote 31 Others thought it should have been released only for vulnerable groups.Footnote 32 One individual responded that it should have been released only if it had been proven to be effective (26b). In group B, most of the participants believed that the vaccine is potentially harmful for the whole population and not just for themselves.Footnote 33 Meanwhile, others argued that it is different for every person:Footnote 34 ‘Everybody reacts differently I can’t know how it might affect others. I can only know how it affects me.’ (24b).

Opposition to vaccines does not harm the vulnerable (manifesting a failure of solidarity)

In group A, interviewees said that there is no question of social solidarity since no immunity wall is created and transmission and disease are not prevented by vaccination.Footnote 35 Everyone is vaccinated for their own good and protection.Footnote 36 Similarly, in group B, respondents said that they believed that vaccination is an act of social solidarity aimed at the common good,Footnote 37 provided that the protocols have been followed (11b, 28b, and 36b) and that vaccination has been shown to make a real contribution to the general good.Footnote 38 But they alluded that this was not the case for the Covid-19 vaccine. Participants (1b, 8b, and 13b) believed that there was no question of social solidarity since vaccination could not prevent the transmission of Covid-19 (25b), nor the deaths of those vaccinated (4b). Vaccination is not a collective action but an individual choice (18b and 25b). Everyone vaccinates to protect themselves.Footnote 39

Polarization

The lives of unvaccinated health workers in group A became very difficult because of their decision not to undergo vaccination.Footnote 40 They lost their jobs, their income, and a career. Their social life suffered, it affected their relationships, and they experienced social exclusion.Footnote 41 In fact, they pointed toward what has been termed in the literature as ‘affective polarization’ (for a discussion, see Filsinger and Freitag Reference Filsinger and Freitag2024), according to which social identities are formed around shared opinions, leading to positive evaluation of one’s group members and a negative evaluation of others outside the group.

Group A interviewees strongly expressed these sentiments: ‘it’s the citizens’ fault when they do not respect each other’s opinion.’ (4a); ‘That’s how polarization is created. When you think the other person is bizarre and you don’t listen and respect the other person’s views.’ (5a); ‘I have experienced social exclusion from family and friends and even at work. It’s very painful because before we were colleagues, friends, brothers and sisters and I don’t think there should be this criterion between people’s relationships.’ (26a).

Group B interviewees also expressed similar sentiments,Footnote 42 yet in a milder manner: ‘Governments have divided the world. Maybe also in the way they have handled this whole issue of the pandemic’ (2b); ‘I don’t think there’s any reason to do that [create a division]. I mean, to put a label and divide the citizens into two groups.’ (22b).

Trust

Both groups expressed distrust of the role of the pharmaceutical industry. They believed that pharmaceutical companies aim to make a profitFootnote 43 and promote their financial interests.Footnote 44 Moreover, participants from both groupsFootnote 45 stated that they do not trust the political system. They have lost their trust since the economic crisis that marked the degradation and devaluation of the political system in all its forms of expression (they referred to memorandum commitments, austerity, salary and pension cuts, economic recession, reversal of referendums, corruption, and inability to deal with crises).Footnote 46 They believe that everyone was pursuing their own agenda (34b and 36b); politicians made decisions without any concern for the citizen (5b and 13b), especially in the health sector (5b). Health services have deteriorated (25b). Privatization and contracts with private contractors do not benefit either the patient or HCWs (25b). ‘And I see everywhere shortcomings, problems, irresponsibility…’ (7b).

Group AFootnote 47 was more outspoken than group BFootnote 48 when it came to the problem of lack of trust. Yet, interviewees from both groups trust frontline workers such as doctors and nurses but not health managers at hospitals and those who make health policies. They also reported that the health system lacks staff and health equipment, lacks organization, and does not function properly, and they put the blame on politicians. ‘All of us daily, we face challenges related to inadequacies of materials, personnel, building infrastructure, limited capacities on the part of the management of each hospital, etc.’ (1a).

Hermeneutic interpretation

The interviews revealed various differentiations. The sample in the first group was more extreme in its views, while group B was more moderate. The majority of participants in group B, for example, recognized that the vaccine should have been released for vulnerable populations, while group A disagreed even on this. Moreover, in Group A, mandates reinforced their decision not to vaccinate. They perceived mandates as a threat to their freedom, and they caused them anger. For group B, things were different. While some underwent vaccination so as not to lose their job, 21 of 38 interviews in group B said that they gradually changed their minds as they became exposed to new experience and information from their immediate social and professional environments. These findings align with theories showing that individuality is constructed through interacting with others (Mead Reference Mead and Morris1934) and is formed through both internal and external conversations (Archer Reference Archer2007) rather than being based on individual decisions taken in a private space secluded from society. Still, the question of perception change (or not) requires more analysis as well as the profound lack of trust toward political institutions. We turn to hermeneutics for assistance.

False optimism, innate immunity, and the flu jab

We noted that HCWs were afraid of not only side effects of the Covid-19 vaccine but also side effects of the flu vaccine. Moreover, they underestimated the risk of catching and spreading the seasonal flu and Covid-19 virus alike and avoided vaccination. In fact, many interviewees from both group A and B explicitly told us that they consider Covid-19 to be similar to seasonal flu or said that they think it is not as dangerous as portrayed in the media.Footnote 49 Interviewee 26b said ‘Covid-19 was given a lot of unnecessary coverage and that something similar that had happened in 2007 and 2010 with H1M1’, 2b said ‘it is a disease like other [flu like] disease’, 29b said ‘things are not tragic’, and 36a explained that ‘it is a virus with low morbidity 0,05 mainly affecting vulnerable groups.’ Some also explicitly mentioned innate immunity as a reason for not vaccinating.Footnote 50

‘Once you either get sick or get vaccinated your immunity will last you six months so why should I go get vaccinated? So, let it be’ (7b).

‘And when we say herd immunity, I understand that those who are healthier will get it and won’t get sick and those who are scared will be more protected.’ (18b)

‘The strangest thing of all, both scientifically and politically is how the importance of natural immunity has been downplayed …It is known that developing antibodies are much better than vaccination and if there is reinfection …it is milder’ (10a).

Our interviewees’ references to innate immunity and seasonal flu provide important cues for a hermeneutic analysis. Meaning needs further elucidation through linking with other texts. Indeed, there is an academic publication by the president of the National Vaccination Committee (Theodoridou Reference Theodoridou2014) where she explains that Greek HCWs feel invulnerable because of the immunity they have acquired from contact with patients. ‘HCWs often manifest a falsified sense of invulnerability due to the protection acquired from their long-standing period as patient care providers.’ Perhaps the best text to further elucidate the idea that a false sense of security may influence perception and decisions is a publication in Nature that dates to 1919 and discusses the reasons why the Spanish flu killed so many people. The paper was written 100 years ago yet still raises questions that are relevant for us today. Similar to Covid-19, there was much uncertainty back then with regard to the transmission and origin of the virus. Moreover, people often exhibited false optimism, underestimated risks, and as a result ignored prevention strategies and posed a threat to themselves and others. Soper (Reference Soper1919) notes that people who were not infected had the burden to take preventive measures and that this burden became even greater given the uncertainty and controversy that surrounded the science behind the Spanish flu.

We find the same false optimism in HCWs’ statements. If we accept this point, then our finding that perceptions change in the light of lived experience (people getting seriously ill and dying in one’s immediate social circle or discussions with trustful persons about harm) makes more sense. These findings align with other studies (Larson, Lin and Goble Reference Larson, Lin and Goble2022) showing that individuals minimized the severity of Covid-19 and/or underestimated the likelihood of contracting it, either because no one in their social circle had been affected or because those affected did not develop serious symptoms. Our findings also align with studies showing that HCWs have a different perception of risk and that attitudes with respect to the flu vaccine influenced attitudes toward the Covid-19 vaccine (Alasmari, Larson and Karafillakis Reference Alasmari, Larson and Karafillakis2022). Health workers who believed they had a high risk of disease were vaccinated against Covid-19 at a higher rate (Nyamuryekung’e, Amour, Mboya et al. Reference Nyamuryekung’e, Amour, Mboya, Ndumwa, Kengla, Njiro, Mhamllawa, Ngalesoni, Kapologwe, Kalolo, Metta and Msuya2023). Similar to Papazachariou, Tsioutis, Lytras et al. (Reference Papazachariou, Tsioutis, Lytras, Malikides, Stamatelatou, Vasilaki, Millioni, Danesaki and Spernovasilise2022), we also found that those who were vaccinated against the flu before and during the pandemic were more likely to be vaccinated against Covid-19. In short, given past practice of avoidance of immunization for all the reasons discussed herein, changing perceptions about innate immunity and perceptions about the seriousness of catching Covid-19 seems to be the key to a successful policy.

Science advice and consensus

Our interviewees’ references to the trustworthiness of the science advice system also provide useful cues:

‘Actually, I don’t trust anyone. One was saying one thing, the other was saying another… And they themselves were in a situation where they couldn’t understand what was happening, what could protect us and what is it that has come out…[what] has killed so many people.’ (2b); ‘The way the system is [organized], the political part of the health care system, with the special [science] committees staffed with people appointed by government … you don’t hear opposing views …., I can’t have confidence.’ (1a)

The science advice system in Greece can be treated as a text with its own narrative. Discussing this narrative is important, to link it to HCWs’ statements. The Greek government expected that the public health system (and HCWs) ought to speak in one voice and follow the scientific consensus as articulated by the newly established science advice system in Greece. They downplayed any uncertainty (as did many other science committees around the world, see Jarman, Rozenblum, Falkenbach et al. Reference Jarman, Rozenblum, Falkenbach, Rockwell and Scott2022) to communicate a single authoritative message and increase the chances of collective action. Indeed, in February 2020, the Greek government put in place a committee of independent experts to assist with the management of the Covid-19 crisis: the National Experts Committee on Public Health (NECPH) (Government Gazette 2020a; Government Gazette 2020b). The new committee played a central role during the crisis and represents a case of evidence-based policy (Ladi, Angelou, and Panagiotatou Reference Ladi, Angelou and Panagiotatou2021), marking a break with many past unsuccessful efforts to introduce science as the basis for policy in Greece, the limited role of expertise, and the poor quality of reforms (Ladi, Angelou and Panagiotatou Reference Ladi, Angelou and Panagiotatou2021; Monastiriotis and Antoniades Reference Monastiriotis, Antoniades, Kalyvas, Pagoulatos and Tsoukas2013; Trantidis Reference Trantidis2016; Tinios Reference Tinios, Kalyvas, Pagoulatos and Tsoukas2013). It is notable that all member names were made known publicly.

Sotiris Tsiodras, professor of Pathology and Infectious Disease at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Medical School, was appointed chief scientist and president of the NECPH (he is also member of the National Vaccination Committee). Professor Tsiodras is a renowned and trusted figure with a reputation for independence, who turned down a position at the University of Harvard and came back to serve his country (Protothema 2020). In appointing a chief scientific advisor (CSA) and institutionalizing an expert committee, the Greek government followed a well-tested model of science advice used in Europe and beyond (Gluckman Reference Gluckman2014; Melchor, Elorza, and Lacunza Reference Melchor, Elorza and Lacunza2020; Wilsdon Reference Wilsdon2014), organized around the idea of a science leader who bridges the world of science with the world of politics. The choice of Prof. Tsiodras bolstered the authority of the committee, projecting to audiences the prestige of science but also that science was put to the service of public health (Tsiodras Reference Tsiodras2021).