Mastitis is known to be one of the most important factors causing economic losses in the dairy industry and impacts animal welfare, antimicrobial usage and food quality (Aghamohammadi et al., Reference Aghamohammadi, Haine, Kelton, Barkema, Hogeveen, Keefe and Dufour2018; Pryce et al., Reference Pryce, Royal, Garnsworthy and Mao2004; Ruegg, Reference Ruegg2017). Because of growing antimicrobial resistance in human and veterinary medicine, it is important to further reduce antimicrobial usage in the future. The majority of antimicrobials in dairy cows are applied due to intramammary infection (IMI) as reviewed in 2017 by Ruegg (Reference Ruegg2017). Therefore, a substantial body of research studies is focused on alternative diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for mastitis in dairy cows. Somatic cell count (SCC) is routinely applied to differentiate between healthy and mastitic udder quarters. Milk cell differentiation for early mastitis detection via flow cytometry allows to identify leucocyte subpopulations and complements the information provided by SCC. IMI is defined by presence of mastitis pathogens, diagnosed via aseptically taken milk samples (IDF 2013). IMI results in the entry of somatic cells into the affected udder quarter, it has been shown that the SCC can be used to identify IMI at a rate of ∼80% (Nyman et al., Reference Nyman, Emanuelson and Waller2016). In the event of IMI, polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells represent the main effector cells and are attracted from the bloodstream into milk alveoli via chemokines. The same applies to monocytes, which differentiate after emigration from blood vessels into macrophages and can remain in affected tissues for months. Lymphocytes represent the predominant cell population in milk under physiological conditions. The fact that the quantity of PMN increases during IMI and that of lymphocytes remains at a low level can be used to precisely detect IMI via the differential milk cell count (DMCC; Pilla et al., Reference Pilla, Malvisi, Snel, Schwarz, Konig, Czerny and Piccinini2013). Dosogne et al. (Reference Dosogne, Vangroenweghe, Mehrzad, Massart-Leen and Burvenich2003) developed a protocol for measuring the DMCC via flow cytometric analysis of milk samples to differentiate between the major leucocyte populations even in low-SCC milk. Koess and Hamann (Reference Koess and Hamann2008) proved that flow cytometric plots can be used to identify viable and non-viable PMN, lymphocytes and macrophages and to count the percentages of these cell types after staining with cell type-specific antibodies. As flow cytometry is now widely utilized in routine diagnostic laboratories, this technique has attracted interest as a promising tool for the early detection of IMI. Degen and coauthors (Reference Degen, Knorr, Paduch, Zoche-Golob, Hoedemaker and Krömker2015) showed that the animal-related probability of bacteriological cure of IMI is associated with the results of DMCC analyses. A study from Italy reported the DMCC as a tool for detecting subclinical mastitis via a high-throughput milk analyser (Zecconi et al., Reference Zecconi, Vairani, Cipolla, Rizzi and Zanini2019). Wall et al. demonstrated that 5 h after an intramammary application of cell wall components from typical mastitis-causing pathogens, the SCC increased only moderately, whereas the DMCC revealed an obvious shift in cell populations. This demonstrated the advantage of IMI detection via the DMCC even in the context of a low SCC (Wall et al., Reference Wall, Wellnitz, Bruckmaier and Schwarz2018).

In recent years, a wide range of alternative strategies for treating mastitis have been described: usage of nonsteroidal or steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oxytocin, prebiotics, homeopathy, and biologics such as hyperimmune serum, egg yolk-derived immunoglobulin Y, lactoferrin or Propionibacterium acnes (Francoz et al., Reference Francoz, Wellemans, Dupre, Roy, Labelle, Lacasse and Dufour2017). To date, however, local and systemic antibiotic treatments remain the first choice for treating IMI. Methods to identify future therapeutic approaches are indispensable. Following the 3 R principle, our working group has established an explant model to study the immunological mechanisms associated with IMI. This model serves to examine early inflammatory mechanisms after pathogen contact. When mammary tissue is used for investigations in vitro, the declared goal is to ensure the general health and udder health of the donor animals. Increased SCC and especially higher PMN in milk of donor cows are interpreted as signs of inflammation. Inter-individual variability is inherently greater than in cell cultures. To minimize this, handling deviations are kept as low as possible, and standardization is maximized. Readouts from explant experiments primarily reflect early regulated factors of innate immunity and antimicrobial effector mechanisms (Lind et al., Reference Lind, Sipka, Schuberth, Blutke, Wanke, Sauter-Louis, Duda, Holst, Rainard, Germon, Zerbe and Petzl2015). The animals’ prior history may influence these responses (Petzl Reference Petzl, Rohmeier, Meyerholz, Günther, Schuberth, Engelmann, Kühn, Hoedemaker and Zerbe2019). This can be explained by high phagocyte traffic that has potential impact on tissue composition and cellular reactivity, potentially altering the measured readouts. The principles of endotoxin tolerance and trained immunity were initially observed in vivo (Petzl et al., Reference Petzl, Gunther, Pfister, Sauter-Louis, Goetze, von Aulock, Hafner-Marx, Schuberth, Seyfert and Zerbe2012) and subsequently reproduced in vitro (Filor et al., Reference Filor, Seeger, de Buhr, von Köckritz-blickwede, Kietzmann, Oltmanns and Meißner2022), and are currently being investigated, particularly in the context of mastitis research. Previously, suitable donor cows for the explant model have been selected based on the SCC in milk obtained in vivo (<200,000 cells/ml). For animal welfare reasons and to reduce stress for donor animals, samples are now obtained from slaughtered donor cows. However, data regarding the comparison of milk characteristics ante mortem and post mortem are missing.

To reduce additional stress through in vivo examination and to allow for post mortem selection of donor cows, this explorative study aimed to investigate how slaughter influences the reliability of SCC and DMCC and to assess their validity as diagnostic markers for udder health in bovine milk samples obtained post slaughter. This research paper addresses the hypothesis that the in vivo criterion of bovine SCC < 200,000 cells per ml milk as a diagnostic marker for healthy mammary tissue is not suitable to be adopted to milk samples taken post slaughter.

Materials and methods

Animals and milk sampling

Due to the explorative nature of the study, the sample size of 9–10 cows/36–40 milk samples per group was applied (Hertzog, Reference Hertzog2008; Hill, Reference Hill1998). Originally, n = 20 cows were enrolled in the study. One cow sampled in vivo was excluded due to signs of clinical mastitis. In total, 19 dairy cows in different stages of lactation were used and sampled at the quarter level: 9 cows (36 samples) at the Livestock Centre at Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich (LMU) in Oberschleißheim and 10 cows (40 samples) after slaughter at a local abattoir. The following breeds were present within the cohort of sampled animals: Holstein Friesian, Simmental and Brown Swiss. Initially, the collected milk was evaluated visually and by means of a semiquantitative cell check (California-Mastitis-Test (CMT), eimü® Cell-Check 3S, Eiermacher, Westring 24, 48356 Nordwalde, Germany) to obtain a first impression of the milk quality and the number of cells in the milk. The absolute quantity of the SCC was further detected via optical fluorescence measured by a DeLaval cell counter DCC (DeLaval GmbH, Wilhelm-Bergner-Str. 5, 21509 Glinde, Germany).

Bacteriological examination

Sample inoculum sizes of 0.01 ml were plated on three types of agar plates and incubated aerobically at 37°C for 48 h. The phenotypic identification of major and minor mastitis pathogens was based on selective media, colony morphology, haemolysis and aesculin cleavage. The bacteriological examination of each cow was considered positive if at least one of the four quarter milk samples showed growth of major pathogens.

Isolation and labelling of milk cells for DMCC determination

Isolation of milk cells was performed in three centrifugation and washing steps. After the last centrifugation, the remaining cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of PBS and labelled with acridine orange (AO) and propidium iodide (PI) for DMCC determination.

Further details concerning the milk sampling, bacteriological examination, milk cell isolation and labelling can be found in the Supplementary File.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cell samples were analysed with a BD AccuriTM C6 Plus flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, 1 Becton Drive, Franklin Lakes, NJ 07417-1880, USA). This flow cytometer uses a blue diode pulse solid-state laser and a red diode laser with excitation wavelengths of 488 and 640 nm, respectively. Data were collected and evaluated with CFlow Sampler Software. For each sample, 20,000 events were counted and displayed as density plots. In the case of milk samples containing very few cells (SCC < 100,000 cells/mL), the threshold was set at >5,000 counts per sample. Cells were differentiated into non-viable (PI +, AO +) and viable cells (PI-, AO +). Based on forward (size-related) and side scatter (complexity- and granularity-related) characteristics, the cells were further differentiated into lymphoid cells, PMN and large cells. Gating was performed in accordance with previous studies in which the DMCC was used to monitor udder health and compare the cell composition of milk between healthy and infected udders (Pillai et al., Reference Pillai, Kunze, Sordillo and Jayarao2001; Mehne et al., Reference Mehne, Drees, Schuberth, Sauter-Louis, Zerbe and Petzl2010; Schwarz et al., Reference Schwarz, Diesterbeck, Konig, Brugemann, Schlez, Zschock, Wolter and Czerny2011; Müller-Langhans et al., Reference Müller-Langhans, Oberberger, Zablotski, Engelmann, Hoedemaker, Kühn, Schuberth, Zerbe, Petzl and Meyerholz- Wohllebe2024). Representative density plots for quarter milk samples analysed by determining the DMCC are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Representative density plots for quarter milk samples analysed by determining the DMCC.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with R (R Core Team, R version R 4.5.0 (2025-04-11)). The bacteriological status was compared between the milk samples obtained from cows in vivo and those obtained from cows post mortem. It was reported for each animal, if ‘major pathogens’ were found. Only five animals (n = 2 in vivo and n = 3 post mortem) were classified positive for major pathogens. Due to the small number of observations in each group, statistical analysis for bacteriological status was not conducted. The results of the bacteriological examination are presented descriptively.

It has been shown in the literature, that hind quarters are more often affected with IMI than front quarters (Abebe et al. Reference Abebe, Hatiya, Abera, Megersa and Asmare2016). Therefore, udder quarter positions (front left [FL], hind left [HL], front right [FR] and hind right [HR]) were compared within the dataset before further analyses. The normality of the data distribution for each udder quarter (FL, HL, FR, HR) within the groups in vivo and post mortem was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test. The homogeneity of variance across groups was tested with the median-centred Levene’s test only for normally distributed data. The Levene’s test results were then considered during the group comparison. If all udder quarters showed normal distribution and homogeneity of variation, data were compared with one-way Fisher’s ANOVA, while if data were normally distributed but variances differed, Welsh’s ANOVA was applied. If at least one udder quarter showed not-normal distribution, data were compared with Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test. For the post-hoc pairwise comparisons between quarters via ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis, the Holm p-value adjustment for multiple comparisons was applied. As no differences were detected, udder quarter position was not incorporated in further statistical analyses.

Subsequently, udder quarters were regarded as dependent units of each individual cow for statistical analyses and repeated measures (within cow) were conducted. The logarithmized numbers of SCC, non-viable cells, viable cells, lymphoid cells, PMN and large cells per ml milk were compared between the milk samples obtained from cows in vivo and post mortem. Due to the presence of repeated measures generalized linear mixed effects models with individual animal as a random effect were chosen for analysis.

The following model assumptions were always checked: (1) the normality of residuals was checked by the Shapiro–Wilk normality test, (2) the homogeneity of variances between groups was checked with Bartlett test and (3) the heteroscedasticity (constancy of error variance) was checked with Breusch–Pagan test. In case assumptions were satisfied, generalized linear mixed effects models were used (R package – lmer). In case assumptions were violated, robust linear mixed effects models were applied (R package – robustlmm). Additionally, both linear and robust linear models were compared amongst each other using following performance quality indicators: Conditional coefficient of determination R2, Marginal coefficient of determination R2, the intraclass-correlation coefficient (ICC) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). The model showing the best combination of fitting power was preferred. All differences between groups were assessed after model-fitting by the estimated marginal means (R package – emmeans).

Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to study the relationships between logarithmized numbers of SCC, and large cells, lymphoid cells and PMN per ml milk. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

SCC and bacteriological analysis

The SCC of milk samples obtained post mortem was significantly higher than the SCC of milk samples obtained in vivo (Fig. 2). None of the quarter milk samples obtained from slaughtered animals showed an SCC < 200,000 cells/ml (min: 204,000 cells/ml; max: 4,298,000 cells/ml), whereas 72% of the quarter milk samples obtained in vivo showed an SCC < 200,000 cells/ml (min: 2,000 cells/ml; max: 679,000 cells/ml). All major pathogens identified in the quarter milk samples were Streptococcus spp. positive for aesculin cleavage. These pathogens were detected in n = 6 quarter milk samples. Of these samples, n = 2 derived from two cows sampled in vivo, whereas n = 4 derived from three post mortem sampled cows. Therefore, within the in vivo group n = 2 animals were considered bacteriological positive, whereas within the post mortem group n = 3 animals were considered bacteriological positive.

Figure 2. Comparison of leucocyte subpopulation data obtained via DMCC.

DMCC via flow cytometric analysis

Median, interquartile range (IQR), mean and standard deviation (SD) of the numbers of SCC, viable cells, non-viable cells, PMN, lymphoid cells and large cells per ml milk within the two groups in vivo and post mortem are presented in Supplementary Table S1. The comparison of udder quarter position did not reveal any significant impact on SCC or DMCC results (P > 0.1; data not shown).

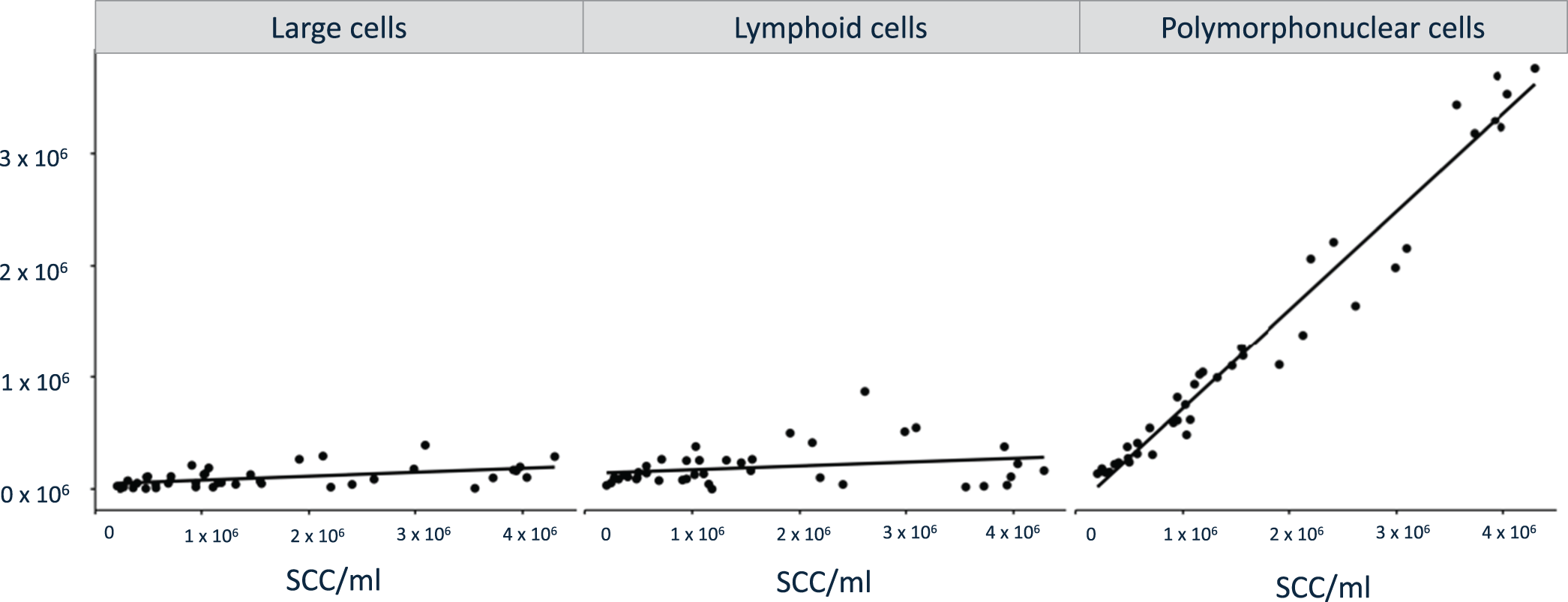

The DMCC verified the significantly higher number of immune cells in the milk samples obtained post mortem from slaughtered cows than in the milk samples obtained from cows in vivo. The number of lymphoid cells, PMN and large cells was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in the milk samples obtained post mortem than in those obtained in vivo, with PMN being the most prominent cell population. Results of the comparison of each immune cell subpopulations measured via DMCC are presented in Fig. 2. Correlation analyses of logarithmized number of SCC versus large cells, lymphoid cells, and PMN revealed a significant positive correlation of large cells (Pearson's correlation coefficient (R) = 0.5; P = 0.0009) and PMN (R = 0.98; P < 0.0001) along rising SCC. The positive correlation was not significant for lymphoid cells (R = 0.2; P = 0.22, Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Correlation analyses of large cells, lymphoid cells, and PMN versus the SCC.

Discussion

Applying flow cytometry for DMCC analysis of quarter milk samples is discussed recently as a promising tool for the early detection of IMI in dairy cows and for monitoring udder health (Pillai et al., Reference Pillai, Kunze, Sordillo and Jayarao2001; Pilla et al., Reference Pilla, Malvisi, Snel, Schwarz, Konig, Czerny and Piccinini2013; Degen et al., Reference Degen, Knorr, Paduch, Zoche-Golob, Hoedemaker and Krömker2015; Fonseca et al., Reference Fonseca, Kurban, Roy, Santschi, Molgat and Dufour2025). Pilla et al. (Reference Pilla, Malvisi, Snel, Schwarz, Konig, Czerny and Piccinini2013) could show that the DMCC could be applied in milk samples with a high or low SCC and be used to identify an existing IMI at an early stage via detection of a rising number of PMN. The authors even established a neutrophilic leucocyte:lymphocyte ratio as a marker for inflammatory processes (Pilla et al., Reference Pilla, Malvisi, Snel, Schwarz, Konig, Czerny and Piccinini2013). Another study showed that lymphocytes were negatively correlated with the SCC (Schwarz et al., Reference Schwarz, Diesterbeck, Konig, Brugemann, Schlez, Zschock, Wolter and Czerny2011). Labelling of immune cells with specific monoclonal antibodies builds the basis for classification of respective immune cell distributions by flow cytometric analysis (Schwarz et al., Reference Schwarz, Diesterbeck, Konig, Brugemann, Schlez, Zschock, Wolter and Czerny2011). This indicates, that by differentiating leucocyte subpopulations, DMCC complements the information provided by SCC, which is routinely applied to differentiate between healthy and inflamed mammary tissue. However, data concerning the impact of sampling methods on the reliability of flow cytometric results are missing.

In veterinary medicine, SCC is the key diagnostic marker for udder health and healthy mammary tissue donor cows are the prerequisite for in vitro experiments with regards to host pathogen interaction. Up to now, usually potential donor animals have been, examined, sampled and selected in vivo shortly before slaughter. For animal welfare reasons and to reduce stress, thorough examination and sampling of live donor animals at the abattoir has increasingly become difficult. Thus, samples mostly have to be obtained from slaughtered donor cows now. Therefore, the aim of this explorative study was to investigate how slaughter influences the reliability of SCC and DMCC and to assess their validity as diagnostic markers for udder health in bovine milk samples obtained post slaughter.

During data collection, we aimed to keep the sampling technique as consistent as possible between the two groups. However, physiological mechanisms occurring in vivo during the removal of the first milk droplets inevitably differ. In vivo, milk ejection and dilution are triggered by teat stimulation and the subsequent release of oxytocin, processes that do not occur when post mortem mammary tissue is used. Moreover, the total milk yield of slaughtered animals cannot be determined, and the milk obtained is likely more concentrated, resembling foremilk. According to the literature, foremilk contains a 2–3-fold higher cell count than the main milk fraction (Sarikaya and Bruckmaier, Reference Sarikaya and Bruckmaier2006). While this represents an important consideration, it cannot account for the approximately 10-fold higher cell counts observed in post mortem samples. The most appropriate approach would have been to compare samples from the same animals before and after slaughter; however, this was not feasible due to technical limitations.

The results of the present study indicate that it is quite important to be aware of the milk sampling conditions before interpreting the flow cytometrically determined DMCC. Independent of the bacteriological status, milk samples obtained post mortem showed up with a significantly higher proportion of PMN compared to samples obtained from cows in vivo. Consequently, post mortem IMI diagnosis should rely more on the detection of major mastitis pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus spp., Trueperella pyogenes or Escherichia coli in milk samples rather than on PMN detection via DMCC determination or SCC alone.

In this study, the number of animals positive for major pathogens was insufficient to allow a statistical calculation of correlations and in our opinion at the same time too small to account for the observed difference in cell counts between the two groups. Therefore, other reasons for the observed immune cell distribution must be discussed. First, mechanical strain during the removal of the udder from the torso in combination with transport from the abattoir to the in-house laboratory, as well as the cleaning procedure followed before sample collection, could impact milk cell distribution patterns. In our opinion, these effects are not strong enough to induce chemotaxis and diapedesis to attract as many PMN as were observed in the corresponding milk samples. Second, during transport to the abattoir and handling before sacrifice, cows are exposed to physical stress, which leads to higher cortisol and catecholamine levels in the blood. These stress-induced endocrine alterations could result in reduced expression of adhesion molecules in PMN and could be associated with an increase in circulating PMN levels (Diez-Fraile et al., Reference Diez-Fraile, Meyer and Burvenich2003). In our view, it is unlikely that stress-induced processes would affect milk cell composition in the observed strong manner. Such pronounced changes in composition were not detected in our previous studies where animals were sampled in vivo after transport but shortly before slaughter or in milk samples obtained from animals at the clinic for ruminants shortly after transport to the clinic.

In our opinion, the most likely explanation for the observed results would be that the routine procedures applied at slaughter, which are stunning by bolt shot and exsanguination, might cause the impressive diapedesis of PMN into the udder secretion. In particular, the drop in blood pressure at the moment of bleeding might intensively impact endothelial permeability via severe damage to the blood-udder barrier. But to the best of the authors’ knowledge no supporting evidence for this explanation can be found in the literature. In contrast, Ichimura et al. (Reference Ichimura, Parthasarathi, Issekutz and Bhattacharya2005) described that a modest increase in blood pressure induced leucocyte margination in postcapillary venules of the lungs in rats, and Meyrick and Brigham (Reference Meyrick and Brigham1983) showed that in sheep, pulmonary hypertension induced the accumulation of leucocytes in the microcirculation. These studies would rather indicate that the intense blood pressure increase occurring shortly before bleeding due to stress or bolt shot leads to the observed PMN influx into the udder. Whether either of the opposing arguments represent the correct explanation can only be speculated and are meant to serve as an attempt of explanation.

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms causing different milk cell distribution patterns, further studies applying flow cytometry to evaluate milk samples are necessary. Comparing more cows in vivo and post mortem after slaughter versus euthanasia would be helpful but was not possible in the present study. In general, milk cell differentiation via density plots generated by flow cytometric analysis was more difficult in milk samples with a low SCC than in those with a high SCC, as very few events were detected, which might impact the comparability of the results.

In conclusion, this dataset indicates that the slaughter procedure impacts SCC and DMCC in milk samples. If selection of donor cows for in vitro models to study mechanisms associated with host–pathogen interaction is performed post mortem, the selection criteria must be adapted instead of being transferred from the in vivo situation. To our opinion, bacteriological examination for detection of major pathogens is a more reliable tool for donor cow selection to exclude sample material collected from mammary tissue with current IMI.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S002202992610199X

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Frank Weber, Sandra Haug (née Kirsch) and Dr. Stefan Nüske for their theoretical and practical support. We also thank the LMU Vet Research programme and the initiative ‘Gleichstellung in Forschung und Lehre’ for providing financial support for this project.

Ethics of experiments

All samples enrolled in this study were taken within routine diagnostic procedures or at the abattoir. The project was conducted according to the German Animal Care law and associated legislative regulations: ‘Tierschutzgesetz’: https://www.gesetze‐im‐internet.de/tierschg/BJNR012770972.html.