Introduction

The drive for accountability in international development cooperation has established Results-Based Management (RBM) as a dominant operational logic for many aid agencies, particularly among OECD-DAC donors (OECD - DAC, 2002; Reference VähämäkiVähämäki, 2017). This approach, which prioritises specific and measurable outcomes, is intended to ensure the efficient and effective use of aid. However, a critical tension emerges when the focus on measurement becomes an end in itself. Scholars have identified this as an “obsessive measurement disorder”, a point where the bureaucratic requirements designed to prove results become counterproductive to achieving them (Reference Alexius and VähämäkiAlexius & Vähämäki, 2024; Reference NatsiosNatsios, 2010). Navigating the balance between necessary oversight and the practical realities of implementation remains a central challenge in the sector, prompting continuous evolution in aid delivery practices (Reference GulrajaniGulrajani, 2015).

Core funding, the provision of financial resources with minimal restrictions on usage (Reference MuttukumaruMuttukumaru, 2015), has emerged as a prominent aid delivery mechanism. Proponents, including academics (Reference Gulrajani and LundsgaardeGulrajani & Lundsgaarde, 2023; Reference Karlstedt, Abdulsalam, Ben-Natan and RizikKarlstedt et al., 2015) and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) (Brolin, Reference Brolin2017; Reference LarssonLarsson, 2018), argue that it enhances efficiency and local ownership of development initiatives. Project funding, on the other hand, involves donors earmarking funds for specific initiatives, often with predetermined objectives and outcomes (OECD - DAC, 2002). While offering targeted support, this approach may introduce challenges related to adherence to donor-specified objectives and potential limitations on organisational flexibility (Reference Caccavale, Haver and StoddardCaccavale et al., 2016).

Despite its popularity, empirical evidence supporting core funding for CSOs remains scarce. While extensive research exists on General Budget Support in state-to-state aid (Reference Elbers, Gunning and de HoopElbers et al., 2007; Reference Koeberle, Walliser and StavreskiKoeberle et al., 2006; Reference NordtveitNordtveit, 2014; Reference Swedlund and LierlSwedlund & Lierl, 2020) these findings cannot be uncritically extrapolated to the distinct dynamics of the CSO sector (Reference DietrichDietrich, 2021; Reference Suárez and GugertySuárez & Gugerty, 2016). This gap risks reducing aid policies to fads or fashions (Reference SwedlundSwedlund, 2017) rather than informed management decisions.

While previous research includes a significant body of work on high-level aid conditionality and allocation (Reference Alesina and DollarAlesina & Dollar, 2000; Reference Nunnenkamp, Öhler and ThieleNunnenkamp et al., 2013), less systematic attention has been paid to the specific procedural requirements governing donor–CSO relationships and their effect on implementing capacities. Local CSOs and field programme officers have had to adapt to increasingly complex aid delivery requirements without perceiving the anticipated benefits (Reference Karlstedt, Abdulsalam, Ben-Natan and RizikKarlstedt et al., 2015; Reference KrawczykKrawczyk, 2018). Despite expectations that local recipients would benefit from core support's flexibility (Reference HonigHonig, 2018), the findings of this paper suggest otherwise, indicating insufficient attention to how aid policy decisions affect implementation outcomes in the case of CSOs.

This article responds to specific calls in the literature: to explore the impact of donor regulations on aid relationships (Reference EybenEyben, 2010), to examine inter-organisational dynamics between donors, intermediaries, and CSOs (Reference Wallace, Bornstein and ChapmanWallace et al., 2007), and to provide empirical evidence assessing RBM efficacy (Reference VähämäkiVähämäki, 2017). The research addresses the evolving landscape of international aid, characterised by increasingly complex donor requirements (Reference Dunton and HaslerDunton & Hasler, 2021; Reference SwedlundSwedlund, 2017), and examines how CSOs navigate diverse and sometimes conflicting donor mandates (Reference McNeillMcNeill, 1981) while maintaining their organisational objectives (Reference HonigHonig, 2018).

This article examines the research question: How do the requirements associated with core funding compare to those of project funding in their impact on the execution outcomes of aid initiatives by civil society organisations? Emphasising donors’ agency (Reference Minasyan, Nunnenkamp and RichertMinasyan et al., 2017) and relationship-focused perspectives (Reference SwedlundSwedlund, 2017), it investigates the aid delivery process black box (Reference Bourguignon and SundbergBourguignon & Sundberg, 2007), aiming to advance scholarship by providing empirical evidence on donor–CSO dynamics while offering practical insights for policymakers and practitioners.

Theoretical Framework

This article is grounded in scholarship that views donor structural and organisational conditions as determinants of aid effectiveness (Reference DietrichDietrich, 2021; Reference GulrajaniGulrajani, 2014; Reference Minasyan, Nunnenkamp and RichertMinasyan et al., 2017) recognising the importance of studying the aid delivery process itself (Reference Ramalingam, Laric and PrimroseRamalingam et al., 2014; Reference SwedlundSwedlund, 2017) and understanding how policies are executed, or “translated into practice” (Reference Froitzheim, Schierenbeck and SöderbaumFroitzheim et al., 2022, p. 288). It is based on political economy and institutionalist approaches to the incentive structure (Reference Gibson, Ostrom, Andersson and ShivakumarGibson et al., 2005; Reference Martens, Mummert, Murrell and SeabrightMartens et al., 2002; Reference Burnside and DollarBurnside and Dollar, 2000) incorporating the increasing complexity of the contemporary aid chain (Reference Alexius and VähämäkiAlexius & Vähämäki, 2024) by systematically characterising the specific administrative and procedural requirements that cascade from donors to recipients. This section presents the core concepts for the analysis which guide the methodological approach and the operationalisation of variables.

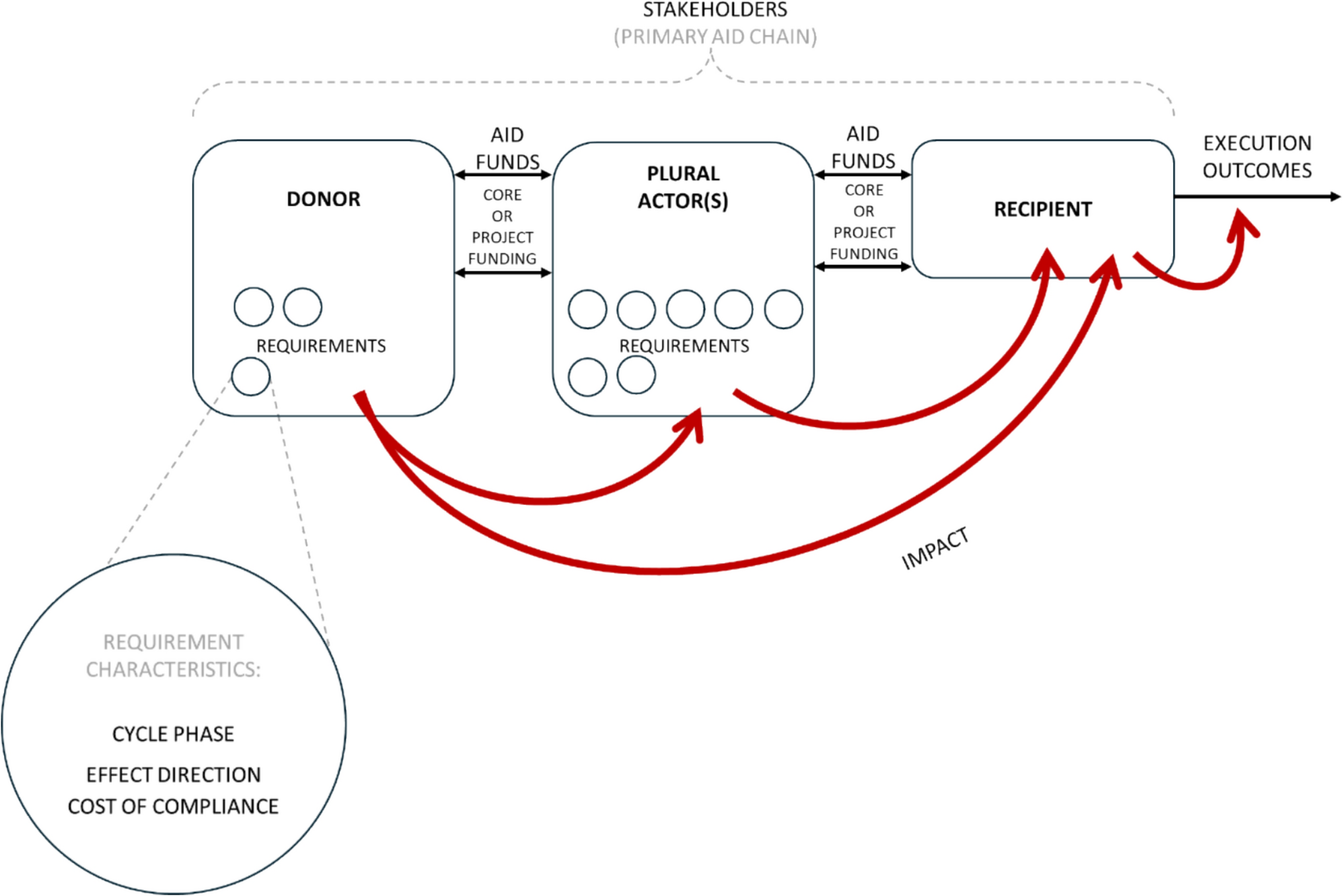

A requirement, is a specific task, action, or condition stipulated by a donor that a recipient must fulfil to access or utilise aid funds (Reference Caccavale, Haver and StoddardCaccavale et al., 2016). Donors, following RBM, establish indicators and specific bureaucratic requirements that recipients must meet to receive aid. They range from relatively straightforward document or questionnaires submission, to complex and demanding implementation of organisational governance adjustments or long-term strategic developments. Three intrinsic characteristics of these requirements are analysed: cycle phase, effect direction, and cost of compliance. Furthermore, reoccurrence, the frequency of compliance requests, is also crucial and differentiated between the aid delivery mechanisms: core funding (fewer, more demanding requirements less often) and project funding (more, less demanding requirements, more often). Finally, the recipient's flexibility in fund utilisation, potentially extending beyond individual initiatives, is also considered.

The effect of these requirements is measured against the execution outcomes, the dependent variable in this framework. Following the results production model (OECD - DAC, 2002), an execution outcome refers to the tangible results, such as specific changes or improvements, that occur as a direct consequence of executing an aid initiative (Reference Arndt, Jones and TarpArndt et al., 2015). The funding for the initiative goes along what is called the aid chain, a complex delivery process through which resources flow from the donor, often via multiple intermediaries, and finally reach the recipient (Reference Wallace, Bornstein and ChapmanWallace et al., 2007). Assessing execution outcomes is complex, however, as the process is subject to numerous ambiguities which make recipient perception a key, yet often unclear, element of the analysis (Reference MatlandMatland, 1995; Reference Mujabi, Otengei, Kasekende and NtayiMujabi et al., 2015). Therefore, this study observes execution through a qualitative analysis of project documents and interviews rather than attempting to quantify a singular result through indicators, thus avoiding the same pitfalls of measurement that the implementing agencies and donors often fall into. In this article, impact then refers to the specific effect that compliance with a donor requirement has on the CSO capacity to execute an initiative. It is later operationalised through a scoring system, detailed in the Methods section, which captures both positive and negative impacts.

Cycle phase refers to the chronological stage of the aid delivery process. Aligned with RBM principles and OECD guidelines (Reference ThioléronThioléron, 2009), aid agencies follow project cycles such as SIDA's “contribution management cycle” (SIDA, 2005). This framework identifies three common phases: application (the pre-phase, with undispersed funds and evaluation through a formal application process of project design, partner assessment, and preparatory activities); implementation (the peri-phase, where the initiative is approved, funds are disbursed, and recipients are executing the project, including regular reporting and potential mid-term modifications in goals and objectives); and evaluation (the post-phase, involving final reporting, both narrative and financial, audits, and monitoring and evaluation). Both cycle phase and reoccurrence frequency influence a requirement's perceived impact, as recipient capacity to comply varies depending on timing and frequency.

Effect direction characterises a requirement's impact as positive or negative, distinguishing between two: scrutinising requirements, control measures that align with the donor's policies and beliefs but not necessarily with the recipient's or the project's immediate needs; and constructive requirements, which facilitate project design and success. The perspective is recipient-centric, but also informed by donors’ and plural actors’ clarifications on requirements’ origins.

Cost of compliance is the tangible resource expenditure (financial, material, and human) to meet a requirement. While proportionality is often considered, donors may not adapt requirements to project funding levels (Reference Achamkulangare and TarasovAchamkulangare & Tarasov, 2017). Compliance cost directly affects perceived impact, as it can divert resources from core project activities.

Stakeholders, as previously described, are critical links in the aid chain, actively participating in aid allocation, disbursement, initiative execution, and overall governance. Stakeholders encompass a spectrum of actors, including not only donors and recipients but also various plural actors (Reference Alexius and VähämäkiAlexius & Vähämäki, 2024), who play intermediary roles in the aid process by responding to both donor and recipient logics at different moments and towards different actors of the aid delivery process.

The usual premise (Reference Banks, Hulme and EdwardsBanks et al., 2015; Reference Deserranno, Nansamba and QianDeserranno et al., 2021) is that executing an aid initiative is responsibility of the recipient. While it does bear the primary responsibility for implementation, it is crucial to acknowledge that all stakeholders involved in the aid process exert direct or indirect influence on the execution outcomes. These stakeholders contribute to shaping the project's trajectory and impact everything from adherence to timelines and budgets to the community engagement and sustainability of the initiative.

Following from this conceptualisation, the framework models the aid delivery process by positing that the flow of resources is accompanied by requirements. These originate from various stakeholders and cascade down the aid chain to the final recipient (Reference Wallace, Bornstein and ChapmanWallace et al., 2007). As established, each requirement is not monolithic; its nature, timing, and cost of compliance determine its effect on execution outcomes. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of this analytical process. It illustrates how the intrinsic characteristics of each requirement, imposed by different stakeholders, combine to produce an overall impact on the aid initiative.

Fig. 1 Visual representation of the analytical framework. Note Source: Author.

To analyse this structure, and answer the research question, I follow a three-step process: The first step involves the identification and quantification of requirements. Through a careful and systematic analysis of application templates, reporting guidelines, and evaluation documents, a comprehensive list of individual requirements associated with a particular initiative is compiled. As noted earlier, a requirement can manifest in various forms, including financial or narrative reports, document requests, thematic policy adherence, governance practices, or a set of standards, among other typologies. The identification process meticulously records and isolates all requirements involved in a specific initiative.

The second step is the assignment of requirements to specific stakeholders. The primary theoretical structure underpinning this stakeholder analysis is the aid chain (Reference Wallace, Bornstein and ChapmanWallace et al., 2007), which, in its more complex form, has been conceptualised as a dynamic web of interactions (Reference Alexius and VähämäkiAlexius & Vähämäki, 2024). Even though not all stakeholders interact directly with the final recipient, it is generally possible to identify the specific point in the aid chain at which a requirement originates. This is achieved by tracing the requirement back through the various intermediaries involved, determining where it first appears or whether it is a direct consequence of the evaluation process conducted by a particular stakeholder. This detailed analysis allows for the isolation of the specific impact that each individual stakeholder exerts on the aid delivery process and, ultimately, on execution outcomes. Furthermore, by contrasting this stakeholder-specific impact with the aid delivery mechanism employed by the initiative (whether core or project funding), it becomes possible to observe whether a stakeholder's behaviour varies depending on the funding modality. This nuanced understanding of stakeholder influence is a key contribution of the framework.

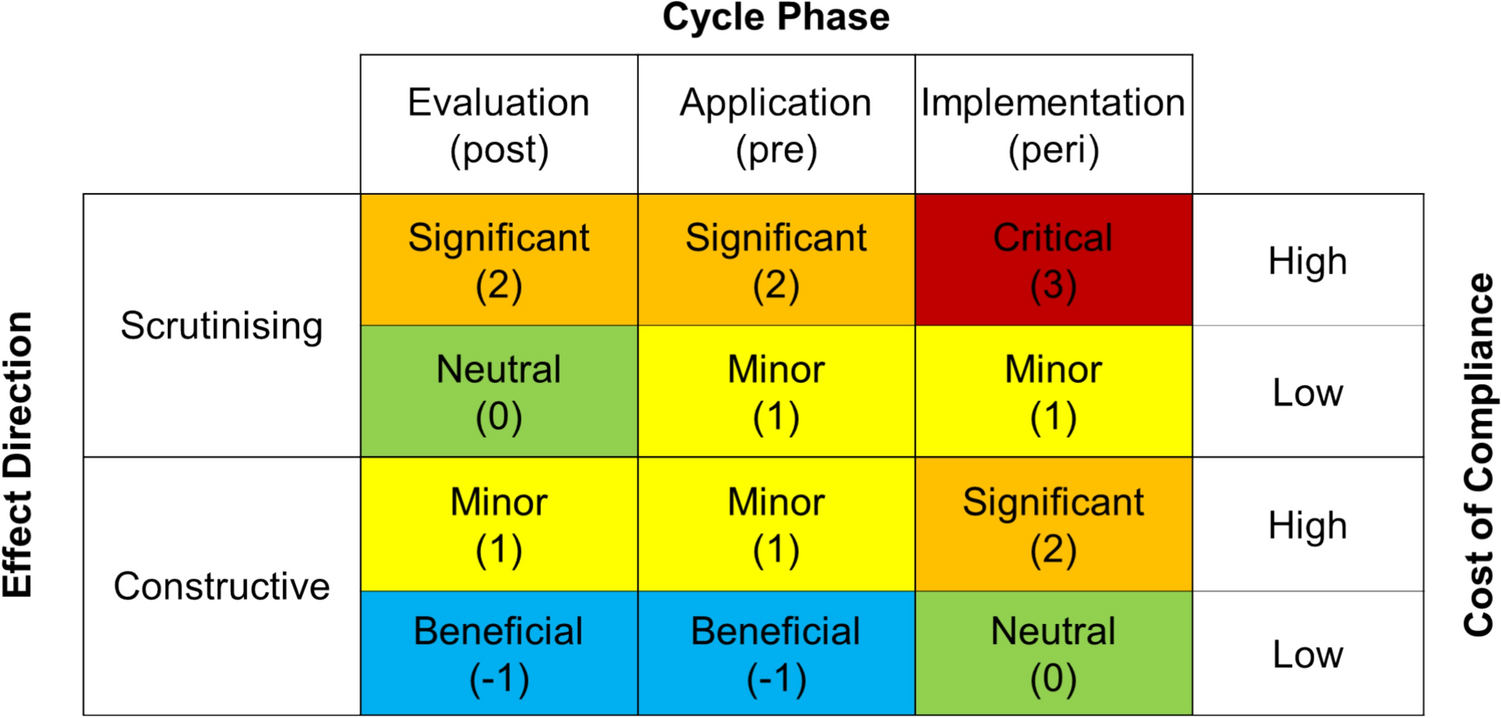

The third step involves a deeper analysis of each individual requirement and a thorough assessment of its impact on execution. This is achieved by carefully characterising the requirement according to the three key elements described earlier: cycle phase, effect direction, and cost of compliance. Each of these characteristics has distinct implications for the overall impact on execution, and the combination of these three characteristics, through the process impact assessment (See Methods and Materials below), allows for a robust comparison and contrast of requirements. This comparison can be conducted not only between different requirements within a single initiative but also across different stakeholders and according to the specific aid delivery mechanisms employed. The impact of a requirement can vary significantly. Some requirements can be beneficial, helping to structure the project or application process and ultimately improving the execution of the initiative. Other requirements may be neutral, having either a low overall impact or a positive impact that is offset by the associated cost of compliance. Finally, requirements can have varying degrees of negative impact, ranging from minor inconveniences to significant burdens and, in the worst cases, critical impediments to project success. A critical negative impact occurs when a requirement diverts significant resources, primarily staff time, away from essential implementation activities and towards bureaucratic tasks. By analysing different combinations of the impact assessment, aggregating requirements according to specific categories, it becomes possible to gain valuable insights into the critical points and potential bottlenecks within the aid delivery process.

The concepts presented above provide a systematic lens through which to observe and interpret stakeholder activities within the aid chain. This framework is used to empirically test a central assumption in aid discourse: that flexible funding mechanisms, such as core support, have a less detrimental impact on execution outcomes than more restrictive project funding. This expectation is grounded in the premise that greater autonomy allows recipient organisations to reduce administrative burdens and focus on implementation (Reference Gulrajani and LundsgaardeGulrajani & Lundsgaarde, 2023; Reference Karlstedt, Abdulsalam, Ben-Natan and RizikKarlstedt et al., 2015). This three-step process of identifying requirements, assigning them to stakeholders, and assessing their specific impact provides the analytical structure to ground these theoretical arguments in empirical evidence, allowing for a granular comparison of how each funding modality functions in practice. The following section details the methods used to apply this framework and test this assumption.

Methods and Materials

This research used a qualitative, comparative case study approach, doing a structured, focused comparison (SFC) (Reference George and BennettGeorge & Bennett, 2005; Reference Jankauskas, Eckhard and EgeJankauskas et al., 2023) of two CSO-led initiatives. This design allows in-depth examination of real-world phenomena within their contexts, capturing data on processes and interactions. It facilitates exploration of causal mechanisms to investigate how donor requirements interact with other variables to influence execution outcomes. The SFC approach is well suited for studying contemporary events where the boundaries between the phenomenon and its context are unclear.

This study examines how donor requirements (independent variable) impact execution outcomes (dependent variable) moderated by aid delivery mechanisms. Performance indicators included adherence to project timelines and milestones, resource allocation efficiency, stakeholder engagement, and CSO adaptability. The aid delivery mechanism moderates the relationship between donor requirements and execution outcomes, as well as between donor and recipient. This study focused on project funding, which provides targeted support for specific initiatives, and core funding, which offers more flexible resources for overall organisational support. Project funding typically involves stricter guidelines, while core funding, in theory, allows greater autonomy.

Control variables were included to minimise the influence of exogenous factors and enhance the comparability of the cases. These included the identity of the donor, the nature of the funding (development funding, different from humanitarian or nexus), and the characteristics of the initiatives (thematic focus, budget, duration, and geographic location).

A most similar systems design (MSSD) logic guided case selection, aiming to maximise comparability while ensuring variation in the independent variable (donor requirements) (Gerring, Reference Gerring2008). The unit of analysis is the donor-recipient dyad. For an x-centred research testing core theoretical expectations, MSSD prioritises cases similar in all respects except the variables of interest. Given the unknown value of the dependent variable a priori, the selection process prioritised variation in donor requirements (achieved via differing aid delivery mechanisms) while controlling for other potentially confounding variables. A between-case comparative approach was adopted, comparing initiatives from two different recipients of the same donor to capture variations in that donor requirements, which are more likely to manifest across different recipients simultaneously than on the same recipient across time. This design choice also facilitates examination of how variables like donor identity, funding nature, and initiative characteristics interact within specific partnerships.

Data collection for execution outcomes was done from primary data sources including document analysis of project applications, narrative reports, and guideline documents, supplemented by insights gathered from semi-structured interviews with aid officials involved in project implementation. The interviews explored the challenges encountered during implementation and provided detailed accounts of how expected outcomes were achieved. For donor requirements, data were primarily gathered through document analysis of funding application templates, evaluation criteria, application instructions, and agency-wide directives related to project management. Interviews with stakeholders provided additional context and insights into the rationale behind specific requirements. Ten semi-structured interviews were conducted, using guides tailored to recipients, donors, and plural actors, reflecting the study's theoretical framework and variable operationalisation. The informants were selected for their knowledge of the programme and their direct involvement in the aid delivery process (See Supplementary Materials, Sect. 2). The flexible nature of the interviews allowed for adaptation based on emerging information, enriching their relevance and depth. Interviews with recipient organisations and regional managers took place in Panama City, Panama, during the launch conference for the SMC programme. Global officer interviews were conducted at the organisation's Stockholm, Sweden headquarters. SMC and SIDA bureaucrats interviews were conducted remotely. All interviews were recorded with participant consent and transcribed for accurate thematic analysis and quote extraction. Researcher notes supplemented these data. Interviews were conducted in either English or Spanish, depending on the participant's preference. Project narratives, financial reports, logical frameworks, and outcome-harvesting instruments provided additional data for understanding project execution. Twelve documents were analysed, both in English, Spanish, and Swedish (See Supplementary Materials, Sect. 1).

Data Analysis: Process Impact Assessment

The collected data were analysed using a thematic analysis of documents and interview transcripts to identify key patterns related to aid execution and donor requirements. Following this, a detailed “process impact assessment” (Reference Franz and KirchmerFranz & Kirchmer, 2012) was conducted for each individual requirement identified in the study. The final assessment and scoring for each requirement were conducted by the author. However, this assessment was not arbitrary; it was systematically grounded in a triangulation of qualitative data. The process focused on synthesising the direct perceptions of recipient CSO officials. During interviews, these officials were asked not only for their general views but also for specific examples of requirements drawn from the application documents. A practical exercise was also conducted where participants compared different requirements, articulating which they found more or less burdensome or helpful. These specific, comparative perceptions were then triangulated with evidence from project applications, guidelines, and narrative reports. The assessment, therefore, focuses on the perceived impact a requirement had on the CSOs’ capacity to execute their initiatives, rather than attempting to measure a final quantitative outcome. This approach acknowledges the subjective and complex nature of the data, key limitations are therefore the potential for informant bias and the limited generalisability inherent in a qualitative case study design, but on the positive side it prioritises the lived experience of the implementing organisations, a perspective often missing from traditional evaluations.

To operationalise this assessment, each requirement was first categorised according to the three intrinsic characteristics defined in the theoretical framework. The cost of compliance was determined as a relative qualitative category (High or Low). A requirement was coded as “High” if informants consistently described it as diverting significant staff time and resources from implementation, using phrases like “extra load” or “involves many different people” and collating with budget figures when available. It was coded as “Low” if it involved submitting pre-existing documents or information aligned with the CSOs’ normal workflow. The effect direction was coded based on the explicit language used by recipients. A requirement was deemed “Constructive” if informants described it as “useful to learn” or helping to “evaluate the project”. Conversely, it was deemed “Scrutinising” if informants described it as a “double effort”, “imposing values”, or could not understand its relevance. For more information of the coding process, see Supplementary Materials (Sect. 3).

These three characteristics were then used to assign a score to each requirement using the impact score matrix (Fig. 2). The resulting impact scores range from -1 (beneficial) to + 3 (critical), where higher numerical values indicate a more negative impact on execution. This scoring structure was adopted for interpretive clarity, as the majority of the requirements’ impacts observed in the data fell within the neutral-to-negative range. It does not presuppose a negative effect of aid, but rather reflects the empirical findings of this specific case. Finally, the reoccurrence of requirements was accounted for by applying a multiplier to each numeric score, allowing for an aggregate comparison of the total impact of requirements across the two funding modalities.

Fig. 2 Impact score matrix. Note. Each requirement is assigned an impact score by locating it in the matrix according to its value in each of the three intrinsic characteristics. The intersection assigns a descriptive label and a numerical score. Source: Author

Empirical Findings

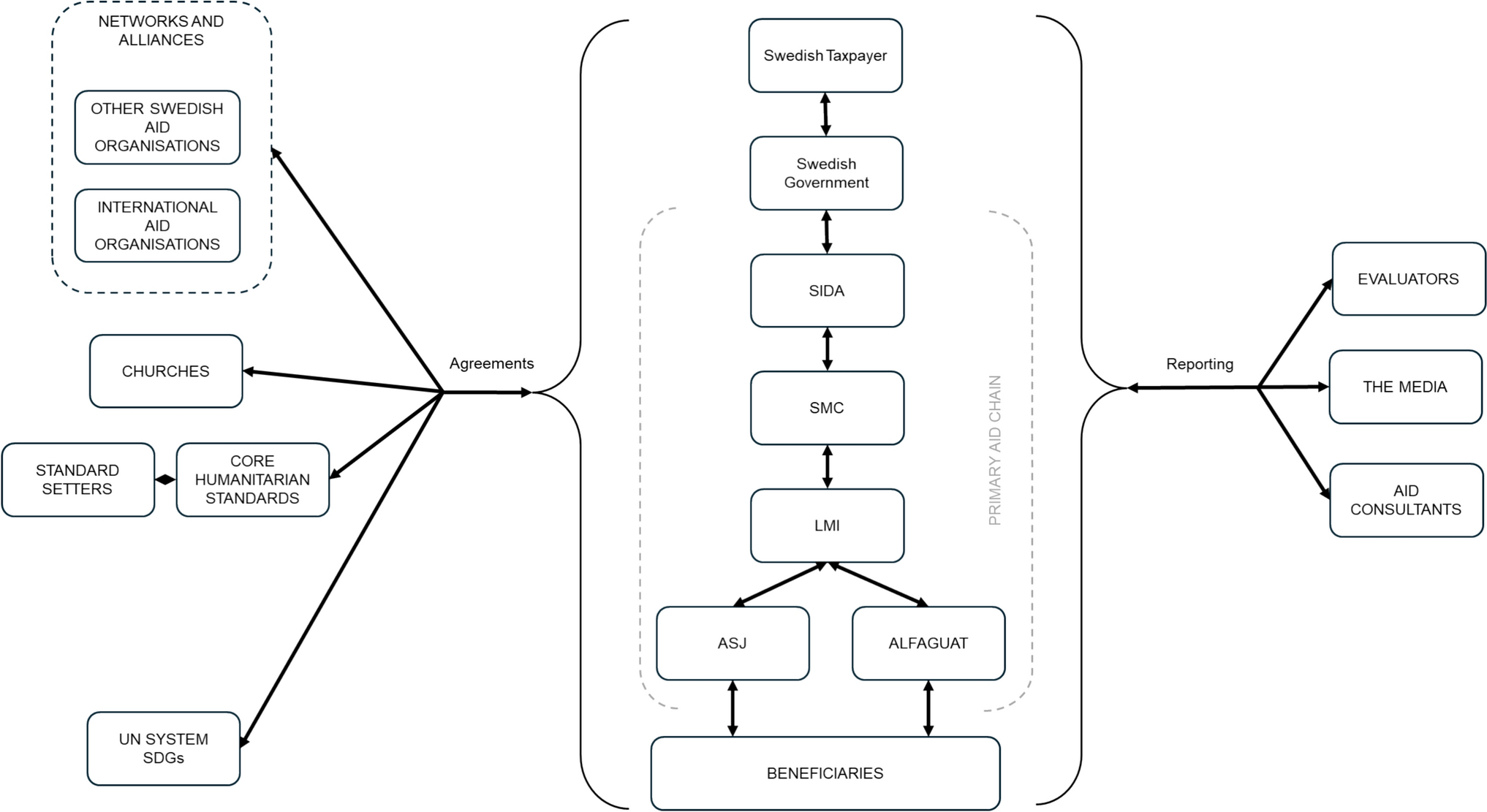

This section delves into the specific characteristics of the selected cases as well as the origin and impact of donor requirements. As established in the analytical framework, the dynamic web model of the aid chain is fundamental to grasping where and how requirements emerge and the mechanisms through which they influence execution outcomes. Figure 3 visually represents the relevant stakeholders for both cases. Crucially, the stakeholder composition differs only in the recipient CSO and the specific aid delivery mechanism employed, adhering to the MSSD logic outlined in the methods.

Fig. 3 Dynamic web model of the aid chain applied to the case studies. Note. Source: Author, based on Alexius and Vähämaki (Reference Alexius and Vähämäki2024)

The diagram distinguishes between the complete stakeholder network and the focused “primary aid chain” on which this analysis concentrates. This focus does not imply that other influences outside the primary aid chain are inconsequential to execution; rather, it reflects the deliberate scope of this study, which prioritises the core relationships directly involved in funding and implementation. The empirical evidence gathered, including interviews and document analysis, centres on the participants within this primary aid chain.

Actor Profiles

The aid chain for the case of study begins with the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) as primary donor, providing 86% of the programme's funds (LM International, 2024). SIDA sets the initial funding requirements, aligning them with its contribution management guidelines and RBM approach (SIDA, 2024a). The funds are channelled through the Swedish Mission Council (SMC), a platform for churches and ecumenical organisations, who allocates them to its member organisations based on its own strategies and theory of change (SMC, 2024) through its member organisations, which then partner with the local CSOs for implementation. LM International (LMI), a faith-based foundation focused on poverty reduction and essential services in vulnerable contexts worldwide, is a member organisation of SMC and the primary applicant for the RISE programme. LMI aggregates the needs of local CSOs and bridges the gap between funding sources and implementers. Beyond its intermediary role, LMI contributes 13% of the programme's funds and manages the initiative's execution, utilising its personnel and expertise (LM International, 2024). This creates a plural actor scenario where SMC and LMI have dual responsibilities: fulfilling application and reporting requirements imposed by their donors while simultaneously establishing its own set of criteria and requirements for applications submitted by their recipients.

The two case studies are Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa (ASJ) in Honduras and Asociación Alfalit de Guatemala (Alfaguat). ASJ, the Honduran chapter of Transparency International, promotes peace, justice, improved services, anticorruption efforts, and transparency (ASJ, 2021). Alfaguat focuses on community empowerment in Guatemala, particularly for women and youth, through education projects (Alfaguat, 2024). ASJ receives core funding and Alfaguat receives project funding, both from the RISE programme and are subject to the requirements of all stakeholders, although their primary communication and reporting are with LMI. These organisations represent the local CSO level, where the impact of the complex aid web, with its various regulatory frameworks and organisational priorities, is ultimately felt. Both initiatives are funded by SIDA through a programme called “RISE for change—Rights, Inclusion and Social Empowerment through CSO Strengthening, Social Audits and Education for All” which aims to promote active citizenship, social auditing, literacy, and CSO strengthening in five countries from 2022 to 2024, in close collaboration of SMC and LMI.

Despite being part of the same programme, they received funding through different aid delivery mechanisms. They fulfil the MSSD criteria by sharing a similar context (Both located in Central America, with the same donor, thematic area and duration, and similar budget size) while differing in the aid delivery mechanism employed (ASJ core funding and Alfaguat project funding).

Analysis of Requirements and Their Impact

A comprehensive analysis of the two cases was conducted. Full results, including a detailed breakdown of each donor requirement for ASJ and Alfaguat are presented in the Supplementary Materials (Table S2). That raw data provide an exhaustive list of requirements, detailing their intrinsic characteristics (cycle phase, effect direction, and cost of compliance), responsible actor, reoccurrence multiplier, and resulting impact scores. This section discusses the empirical data informing the analysis and highlights key insights.

Sixty-eight distinct requirements were identified across the two cases through an exhaustive document review. These requirements encompass a broad spectrum of information and stipulations, including recipient organisational details, organisational policies and contextual assessments, logical frameworks, governance procedures and systems, staff functions, project and organisational budgets, financial reports and audits, partner assessments, implementation and evaluation plans, standardised certifications, and contribution criteria. The identification process went beyond listing application and reporting templates questions, involving a detailed comparison with evaluation guidelines and strategy documents to discern expected answers. Some single questions represented multiple distinct requirements. Sixty requirements were applicable to project funding, and eight to core funding. While some requirements appear in both mechanisms, they are more frequent in project funding due to enhanced due diligence. However, periodic assessments (e.g. narrative reports, financial reports, some audits) are required at the same frequency for both. A multiplier, based on the three-year initiative duration, was assigned to each requirement to reflect this frequency difference.

Stakeholder Analysis

The next step identified each requirement's originating actor. It often is the requesting stakeholder, but this is not always the case. Although SMC handles the primary application process, not all requirements originate from them. Analysis of policies and guidelines, supplemented by interviews, revealed instances where requirements complied with requests from other stakeholders even if this connection was not always immediately apparent. As one plural actor informant explained, “I'd say that most would be requirements from SIDA that we have just, you know, forwarded downwards. But then there would be things that they not necessarily have said you have to do it this way” (Interview; 26th April 2024), illustrating the complexity of aid chain influence. SMC application questions about risk management policies are actually SIDA requirements, due to their ISO 3100 framework compliance mandate. Similarly, some requirements, like LMI's periodic narrative reports and internal audits, are not documented in templates but are still requested. Identifying the responsible stakeholder for each requirement was challenging, requiring nuanced examination of context and origin. Recipient CSOs themselves recognise this ambiguity, often struggling to understand the expected response. As a recipient's informant explained, “Sometimes we have the information itself but they request it in different formats, or maybe it comes from different donors and we do not know if it has a different logic. Therefore, answering that requires an extra intervention on our part” (Interview; 20th March 2024). This underscores the difficulties recipients face navigating the often-opaque landscape of donor requirements.

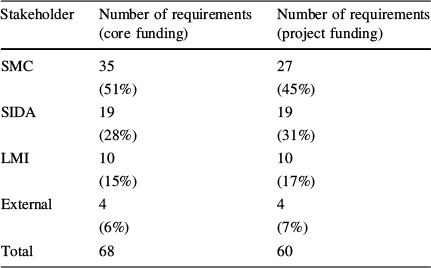

Table 1 presents a summary of the results of this stakeholder identification process. SMC emerges as the stakeholder with the largest number of requirements, with 35 for core funding and 27 for project funding. The remaining stakeholders have the same number of requirements for both aid delivery mechanisms.

Table 1 Stakeholder analysis of donor requirements for both cases

Stakeholder |

Number of requirements (core funding) |

Number of requirements (project funding) |

|---|---|---|

SMC |

35 (51%) |

27 (45%) |

SIDA |

19 (28%) |

19 (31%) |

LMI |

10 (15%) |

10 (17%) |

External |

4 (6%) |

4 (7%) |

Total |

68 |

60 |

Interestingly, according to one informant, SIDA actively promotes the use of core funding for aid initiatives but does not provide specific guidelines for its implementation, leaving the details to the discretion of its SPOs. This explains why SMC is the only stakeholder that imposes a higher number of requirements under core funding compared to project funding; the other actors’ requirements remain constant across both modalities. SIDA is the second largest source of requirements, followed by LMI. A fourth category, labelled “External”, encompasses all actors outside the primary aid chain but who still exert some influence on the requirements imposed, despite not directly requesting them. Examples include certification agencies and standard setters, such as the CHS, and global agreements, such as the SDGs. These external influences are relevant because they still have an impact on the requirements landscape, even though they are not directly part of the system that disburses the funds. Overall, while the total number of requirements is slightly higher for core funding, the difference is not substantial, indicating a relatively balanced distribution across both funding types in terms of the absolute number of requirements.

Process Impact Assessment

Requirements were assessed in their three intrinsic characteristics. This characterisation was informed primarily by recipient's perspective, obtained through the interviews, and the review of the documentation of the RISE programme. The first intrinsic characteristic, cycle phase, was the most straightforward to define, given that the documents usually specify when each requirement needs to be complied with. Most of the project description and organisational and contextual assessments are required during the application (pre-phase). Financial and narrative periodic reports are requested during implementation (peri-phase), as are some of the external quality standards. Audits, as well as the monitoring and learning assessments, are requested during the evaluation (post-phase).

The effect direction of each requirement was assessed through the input provided by recipients during the interviews. Informants were asked to provide specific examples of what they considered positive and negative requirements. For instance, an informant, when asked about positive requirements, stated, “I see as positive when the demand is useful to learn, when it helps to evaluate the project and what we need to take an interest on” (Interview; 21st March 2024). Regarding negative requirements, another informant noted, “For me, negative is perhaps something less relevant, it is like, look, I don't know why this is being requested” (Interview; 20th March 2024). This sentiment was echoed by another informant:

“I believe that some policies are a little bit of both, we have an internal ethical code that regulates several aspects of anticorruption, fraudulent practices and conflict of interests, but the donor wanted to see a specific anticorruption policy. It is useful because it gives more strength to the organisation, but at the same time it is a double effort to create something new out of practices that already existed (…) It does not justify creating a different document and it puts an extra load on the team” (Interview; March 20th, 2024).

Notably, periodic narrative and financial reports were generally viewed as constructive, as they allowed the CSOs to focus efforts and resources on goal achievement. Conversely, codes of conduct and organisational policies were often seen as scrutinising, given that the organisations already had their own in place and felt that the donor organisations were imposing their values. These responses provided the basis for developing a simple taxonomic key (See Supplementary Materials, Sect. 3) to assess each requirement.

The cost of compliance was also assessed using input from the informants and through a review of the budget attached to the application document. The primary driver of cost is the time spent by staff. As one informant explained, “many resources are spent, like a lot, because it involves many different people. From me, from [multiple names], from the Global Office. It ends up costing quite a lot” (Interview; 22nd March 2024). In general, requirements with a low cost are those that do not involve extra processing from the recipient and can be directly attached to the application or the report, such as formal documentation and pre-existing policies, or requirements that had to be developed anyway as part of the project design, such as a theory of change or activity plans. High-cost requirements are usually those that require input from several staff members and, in some cases, impede their presence on the field implementing their initiatives. For example, partner assessments involving visits to headquarters and lengthy interviews and workshops, as well as narrative reports that require a specific methodology or framework that the organisation is not familiar with, represent high costs of compliance.

With this characterisation, and using the impact score matrix, a score was calculated for each requirement, and the reoccurrence multiplier was applied. While the implications for impact of the effect direction and cost of compliance are straightforward (scrutinising and high cost being the negative ones, and constructive and low the positive ones), the cycle phase requires a closer look. Insights from the interviews with the recipients demonstrated that the worst moment to comply with requirements is during the implementation phase. “It comes to a point when we have to ‘make space’ to do our work, to visit the communities and follow up implementation” (Interview; 21st March 2024). The moment when it has the least impact is after the project finishes, because it does not deviate efforts from the execution. After applying the matrix to the full set of requirements, Table 2 shows a summary of the impact scores for both aid delivery mechanisms.

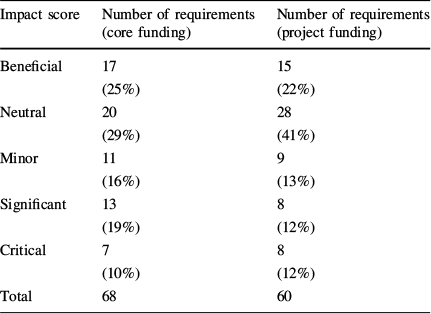

Table 2 Number of donor requirements by their nominal impact score

Impact score |

Number of requirements (core funding) |

Number of requirements (project funding) |

|---|---|---|

Beneficial |

17 (25%) |

15 (22%) |

Neutral |

20 (29%) |

28 (41%) |

Minor |

11 (16%) |

9 (13%) |

Significant |

13 (19%) |

8 (12%) |

Critical |

7 (10%) |

8 (12%) |

Total |

68 |

60 |

Reoccurrence multiplier applied. The impact score is unitless and must be interpreted relative to other categories. The higher the impact score, the more negative impact the requirements have on the execution of aid initiatives

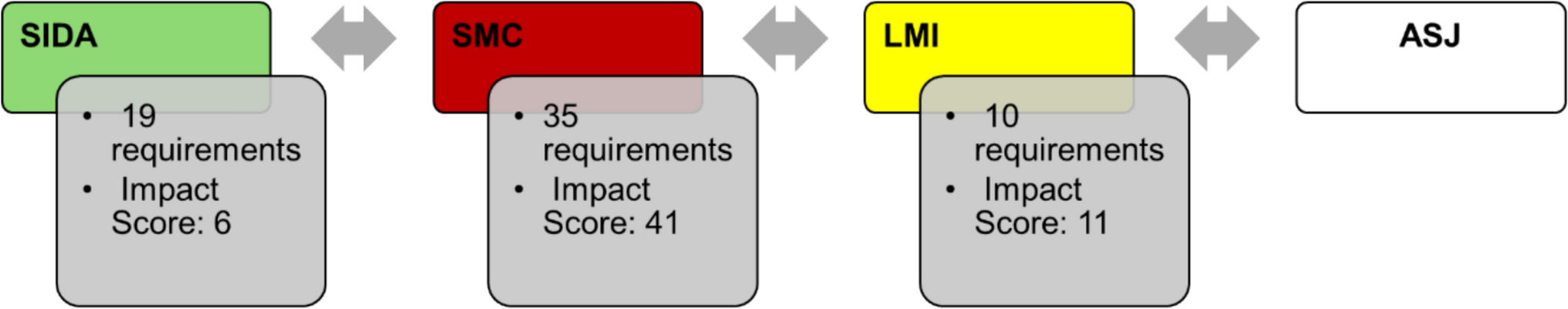

Combining the results of the impact scoring and the stakeholder analysis completes the full process impact assessment. Figure 4 summarises the results for the ASJ case, operating under core funding. Notably, SMC emerges as the primary source of requirements, with 35 identified and the highest impact score of 41. This stems from SMC's protagonist role in partner assessments for core funding and the associated more rigorous requirements it has for this type of support (SMC, 2024). LMI follows with 10 requirements and an impact score of 11, attributable to additional requirement revisions aligning with its own policies and indicators. Conversely, SIDA imposes 19 requirements but registers the lowest impact score, as these requirements are imposed only once at the project grant stage without direct oversight on the day-to-day operations of the recipient organisation.

Fig. 4 Process impact assessment for the ASJ (core funding) case. Note. Source: Author

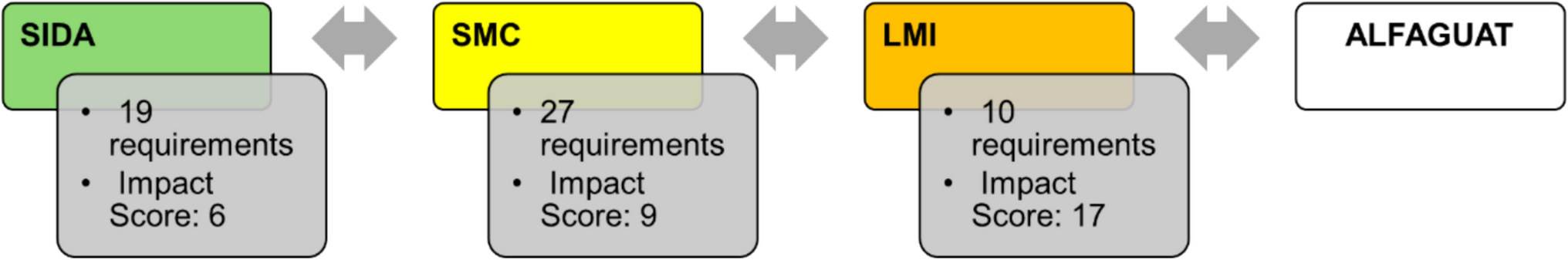

Figure 5 summarises the results of the process impact assessment for the Alfaguat case, which utilises project funding. Surprisingly, LMI, despite having the fewest requirements, records the highest impact score. This is due to higher reporting periodicity and some high-cost requirements. SMC, with the highest number of requirements (albeit fewer than in the core funding scenario), exhibits a significantly lower impact score of 9. Here, SMC's role as the primary evaluator and implementer results in many requirements that are formal in nature and low in compliance costs, therefore having a lower score. Additionally, it exhibits the majority of the beneficial requirements in this modality. Notably, SIDA's requirements and score mirror those of the ASJ case, underscoring a consistent behaviour regardless of funding type, a reflection of SIDA's more detached and strategic approach to aid delivery for civil society, the main reason for it delegating monitoring to SPOs, but also of its position at the beginning of the aid chain.

Fig. 5 Process impact assessment for the Alfaguat (project funding) case. Note. Source: Author

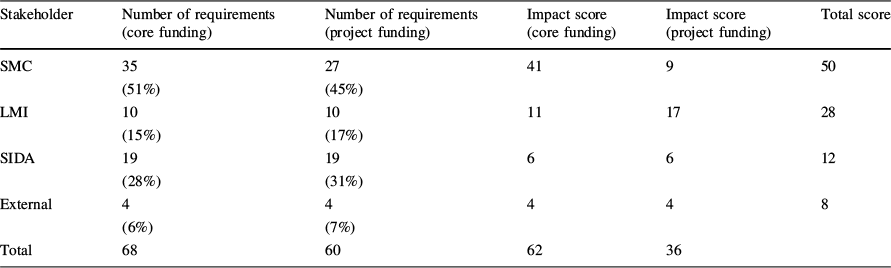

The findings of the process impact assessment reveal a complex dynamic within the aid chain, leading to the paper's central, counter-intuitive result. As summarised in Table 3, the requirements associated with core funding had a significantly higher negative impact (total score: 62) than those of project funding (total score: 36). This finding challenges the prevailing assumption that core funding's flexibility reduces the administrative burden on CSOs. The aggregate scores also mask crucial variations in the roles played by intermediary stakeholders, as illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5. In the core funding scenario, SMC is the dominant source of the negative impact (score of 41), stemming from its intensive partner assessment process. Conversely, in the project funding scenario, LMI has the highest impact (score of 17), attributable to its role in managing more frequent reporting. This stakeholder-level analysis indicates that the overall impact is not a simple function of the funding type, but of how specific intermediary actors adapt their procedures and exert control within each modality.

Table 3 Summary of the process impact assessment by stakeholders and aid delivery mechanisms

Stakeholder |

Number of requirements (core funding) |

Number of requirements (project funding) |

Impact score (core funding) |

Impact score (project funding) |

Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

SMC |

35 (51%) |

27 (45%) |

41 |

9 |

50 |

LMI |

10 (15%) |

10 (17%) |

11 |

17 |

28 |

SIDA |

19 (28%) |

19 (31%) |

6 |

6 |

12 |

External |

4 (6%) |

4 (7%) |

4 |

4 |

8 |

Total |

68 |

60 |

62 |

36 |

The impact score is unitless and must be interpreted relative to other categories. The higher the impact score, the more negative impact the requirements have on the execution of aid initiatives

Several key factors influenced these outcomes. While core funding typically involves more requirements than project funding, the impact stems not just from quantity but from the nature, timing and cost of requirements. Despite aims to streamline processes, core funding retains many project funding requirements, subjecting recipients to drawbacks from both mechanisms.

Discussion and Implications

The qualitative data revealed key tensions within the aid relationship. Regarding proportionality, one intermediary informant was blunt about the funding levels: “no, not at all, it's not enough” (Interview; 22nd March 2024). On the other side, an informant described SMC's highly collaborative approach: “[SMC] rarely rejects any projects, instead, if it has weaknesses, they work and work and work until it has reached the acceptable level” (Interview; 26th April 2024). Tensions also exist in project funding, where one recipient expressed concerns about a lack of organisational support, stating, “it seems as if we are not important, only the project” (Interview; 21st March 2024). The findings suggest that while some requirements positively contribute to capacity-building, many have negative impacts due to compliance costs. It reveals that requirements are easier to adapt to before fund disbursement than during implementation. The results also indicate that stakeholders often impose additional requirements downstream to demonstrate progress, as noted by informants who stated “we must show that we are making progress when evaluating applications” (Interview; 26th April 2024).

It is important to acknowledge alternative explanations for these findings. The two CSOs in this study, ASJ and Alfaguat, have clear differences in terms of organisational capacity, operational scale, and previous project experience. ASJ, as the Honduran chapter of Transparency International, is a very different type of organisation than the more grassroots-focused Alfaguat, and these differences likely influence the type of funding they receive and their interactions with donors. Similarly, pre-existing relationships and external political conditions are undoubtedly relevant factors that shape how aid is implemented.

However, while these factors form a critical part of the context, the analysis demonstrates that the intrinsic nature of the requirements themselves remains a key explanatory variable. The study's contribution lies in isolating and systematically assessing each individual requirement based on its timing, its perceived purpose, and its cost in terms of staff time and resource diversion. This granular analysis reveals that a poorly timed or high-cost scrutinising requirement creates a negative process impact (diverting resources from implementation to compliance) regardless of an organisation's overall capacity. While a high-capacity organisation might manage the burden more efficiently, the diversion of resources still occurs. Therefore, the findings suggest that excessive or poorly designed requirements can lead to obsessive measurement disorder, emphasising the need for a better balance between oversight and operational efficiency.

The study reveals that impact varies based on delivery mechanisms and stakeholder positions in the aid chain, with core funding counter-intuitively showing higher impact due to layered requirements. This article ultimately suggests that improving aid effectiveness requires not just simplified requirements, but a fundamental rethinking of how donors structure their relationships with implementing CSOs.

Conclusions

This article contributes to our understanding of foreign aid delivery, donor-recipient relations, and project execution within the CSO context. Through a structured, focused comparison of two Latin American CSOs receiving SIDA funds (one via core funding, the other via project funding), this research investigates how donor requirements impact aid initiative execution. Contrary to prevailing theories, core funding demonstrated a more detrimental impact than project funding due to the nature, timing, and cost of its associated requirements. This result points not to a simple failure of one modality, but to the unintended consequences of donor-centric management policies rooted in RBM. These findings also highlight the limitations of applying General Budget Support research to the CSO context, which has distinct aid chains and stakeholder interactions. The study also reveals variations in stakeholder impact, with SMC and LMI playing prominent roles in core and project funding, respectively, likely due to their plural actor status. Furthermore, while core support is often assumed to empower local actors and offer flexibility, this research suggests a more complex reality as recipient organisations often reject core funding due to perceived lack of ownership, donor intrusiveness, and unclear requirement origins. These findings offer theoretical implications for streamlining aid delivery by reducing the number of actors involved, minimising requirement duplication, and harmonising standards. The primary policy insight is a call for a more evidence-based evaluation of donor management policies, taking into account their full impact on recipients and the complexities of the aid delivery process. Future research should broaden the sample size and explore these dynamics in other contexts. This study advances scholarship on donor requirements and aid execution by offering recommendations to promote a more balanced and sustainable approach to development cooperation.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Prof. Fredrik Söderbaum for his invaluable guidance, support, and supervision throughout this project. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to Dr. Josephine Sundqvist for her continuous encouragement and support. This research would not have been possible without the generous participation of the CSOs who provided interviews and valuable information. I also extend my gratitude to the entire LARO team for their enthusiastic collaboration.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital). Partial financial support for fieldwork was received from the Adlerbertska Forskningsstiftelsen through a travel grant.

Employment

The author was employed part-time by Läkarmissionen—stiftelse för filantropisk verksamhet at the time the research was conducted.