Introduction

Within the Upper Palaeolithic (ca. 42–12.5 ka cal BP), the Magdalenian period has the largest number of sites located in southwestern Europe (e.g., Sacchi, Reference Sacchi2003), including the North of the Iberian Peninsula (e.g., Bernal Reference Bernal2024). The Lower Magdalenian phase, dated between ca. 20–17 ka cal BP, during the Greenland Stadial 2 (Grootes et al. Reference Grootes, Stuiver, White, Johnsen and Jouzel1993; Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Bigler, Blockley, Blunier, Buchardt, Clausen, Cvijanovic, Dahl-Jensen, Johnsen, Fischer, Gkinis, Guillevic, Hoek, Lowe, Pedro, Popp, Seierstad, Steffensen, Svensson, Vallelonga, Vinther, Walker, Wheatley and Winstrup2014), is well documented in the sites placed in the mouth of the Sella River valley (Asturias) (Jordá-Pardo et al. Reference Jordá-Pardo, Martín-Jarque, Portero and Álvarez-Fernández2022) (Figure 1). During this phase, subsistence strategies of hunter-gatherer groups were centered on the hunting of red deer and the gathering of marine mollusks (Álvarez-Fernández Reference Álvarez-Fernández2011, Reference Álvarez-Fernández2013; Portero et al. Reference Portero, Cueto, Elorza, Marchán-Fernández, Jordá Pardo and Álvarez-Fernández2024). The lithic industry was characterized by tools such as end-scrapers and microlithics (e.g., backed bladelets and triangles), and the bone industry by weapons (e.g., sagaie points with square cross-section) and other tools for daily use (e.g., needles, awls and spatulas) (Álvarez-Fernández et al. Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Tapia, Arias, Camarós, Cerezo-Fernández, García-Alonso, Martín, Martín-Jarque, Peyroteo-Stjerna, Portero, Teira, Cueto, Jordá Pardo, Martín-Jarque, Portero and Álvarez-Fernández2022; Moure Reference Moure1990). The evidence of territoriality and mobility between different regions of the northern Iberian Peninsula has been amply demonstrated by the circulation of flint, personal ornaments and mobiliary art objects (e.g., Utrilla Reference Utrilla and Fano2007; Martín-Jarque et al. Reference Martín-Jarque, Tarriño, Delclòs, García-Alonso, Peñalver, Prieto and Álvarez-Fernández2023).

Figure 1. Study area located in the northern Iberian Peninsula (Cantabrian Region). The lower map details Tito Bustillo Cave and principal neighboring Lower Magdalenian archaeological sites in the Sella River valley.

One of the most relevant Magdalenian sites in the northern Iberian coastal area (known as Cantabrian Region) is the Tito Bustillo cave (Figure 1), well-known for its Palaeolithic paintings and engravings (Balbín et al. Reference Balbín, Alcolea, Alcaraz and Bueno2022). Archaeological excavations in different areas of the cave revealed human use dating between the beginning and end of the Upper Palaeolithic, as well as the beginning of the Holocene (Álvarez-Fernández et al. Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Bécares, Cueto, Uzquiano, Jordá Pardo and Arias2015, Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Cueto, Tapia, Aparicio, Douka, Elorza, Gabriel, García-Ibaibarriaga, Murelaga, Suárez-Bilbao and Arias2018; Balbín et al. Reference Balbín, Alcolea, Alcaraz and Bueno2022; Moure Reference Moure1997). However, the most intense human activity took place during the Magdalenian, particularly in the so-called Living Area (Área de Estancia) near the entrance of the cave during prehistoric times, which is currently blocked by a landslide. Extensive excavations were carried out in this area during the 1970s and 1980s, encompassing an area of approximately 27 m2. In the stratigraphic unit (SU) labelled as level 1, different habitat structures were documented (arranged slabs hearths, etc.), to which were associated anthracological remains, bones of ungulates and marine mammals, shells of marine invertebrates, antler and bone artifacts, manufactured lithic artifacts, and engraved sandstone plaquettes, among others (García-Guinea Reference García-Guinea1975; González-Sainz Reference González-Sainz1989; McGrath et al. Reference McGrath, van der Sluis, Lefebvre, Charpentier, Rodrigues, Álvarez-Fernández, Baleux, Berganza, Chauvière, Dachary, Duarte-Matías, Houmard, Marín-Arroyo, de la Rasilla Vives, Tapia, Thil, Tombret, Torres-Iglesias, Speller, Zazzo and Pétillon2025; Moure Reference Moure1990, Reference Moure1997; Moure and Cano Reference Moure and Cano1976). The SU level 2, which was never fully excavated, is a level with hardly any archaeological remains and would correspond to a sedimentation phase in Living Area (García-Guinea Reference García-Guinea1975; Moure 1990 Reference Moure1997; Moure and Cano Reference Moure and Cano1976). Based on analyses of lithic and osseous industry remains recovered from these excavations in the Living Area, Levels 1 and 2 have been chronologically attributed to the Lower Magdalenian (Álvarez-Fernández et al. Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Tapia, Arias, Camarós, Cerezo-Fernández, García-Alonso, Martín, Martín-Jarque, Peyroteo-Stjerna, Portero, Teira, Cueto, Jordá Pardo, Martín-Jarque, Portero and Álvarez-Fernández2022; Cerezo-Fernández et al. Reference Cerezo-Fernández, Cueto, Tapia, Álvarez-Fernández, Markovic and Mladenovic2024; Martín-Jarque et al. Reference Martín-Jarque, Herrero-Alonso, Tarriño, López-Tascón, Prieto, Bécares and Álvarez-Fernández2022). Archaeological work in this part of the cave was resumed in 2020 by an interdisciplinary research team from the University of Salamanca (Álvarez-Fernández et al. Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Tapia, Arias, Camarós, Cerezo-Fernández, García-Alonso, Martín, Martín-Jarque, Peyroteo-Stjerna, Portero, Teira, Cueto, Jordá Pardo, Martín-Jarque, Portero and Álvarez-Fernández2022).

Marine mollusk shells are frequently recovered from near-coastal archaeological sites, and they are often used to establish the chronology of site occupations by past hominin populations through radiocarbon dating (e.g., Aguirre-Uribesalgo et al. Reference Aguirre-Uribesalgo, Álvarez-Fernández and Saña2024; Arniz-Mateos et al. Reference Arniz-Mateos, García-Escárzaga, Fernandes, González-Morales and Gutiérrez-Zugasti2024; García-Escárzaga Reference García-Escárzaga2020; García-Escárzaga et al. Reference García-Escárzaga, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, Marín-Arroyo, Fernandes, Núñez de la Fuente, Cuenca-Solana, Iriarte, Simões, Martín-Chivelet, González-Morales and Roberts2022a; Thomas Reference Thomas2015). Nevertheless, the depletion of 14C content in marine samples compared to their contemporary atmosphere, a phenomenon known as the marine reservoir effect (MRE), results in the radiocarbon age derived from marine shells being apparently older than those from coeval terrestrial samples (Erlenkeuser Reference Erlenkeuser, Berger and Suess1979; Rick et al. Reference Rick, Vellanoweth and Erlandson2005). MRE exhibits spatiotemporal variability (Martins and Soares Reference Martins and Soares2013; Soares et al. Reference Soares, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, González-Morales, Martins, Cuenca-Solana and Bailey2016). ΔR(t) expresses the difference between observed MRE, for a specific time and location, and the global marine calibration curve (Heaton et al. Reference Heaton, Köhler, Butzin, Bard, Reimer, Austin, Austin, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Hughen, Kromer, Reimer, Adkins, Burke, Cook, Olsen and Skinner2020; Stuiver and Braziunas Reference Stuiver and Braziunas1993). In the following, for simplicity, we refer only to ΔR, contextualized according to location and the time period. Estimating both the temporal and geographical changes in ΔR values is critical to accurately calibrating radiocarbon dates from subfossil marine shells (e.g., Ascough et al. Reference Ascough, Cook and Dugmore2009; Petchey et al. Reference Petchey, Dabell, Clark and Parton2023; Ulm et al. Reference Ulm, O’Grady, Petchey, Hua, Jacobsen, Linnenlucke, David, Rosendahl, Bunbury, Bird and Reimer2023).

Previous research carried out along the Atlantic façade of the Iberian Peninsula have allowed us to quantify ΔR values for different locations and chronologies throughout the Holocene period (García-Escárzaga et al. Reference García-Escárzaga, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, Cuenca-Solana, González-Morales, Hamann, Roberts and Fernandes2022b; Martins and Soares Reference Martins and Soares2013; Soares and Dias Reference Soares and Dias2007; Soares et al. Reference Soares, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, González-Morales, Martins, Cuenca-Solana and Bailey2016). Soares et al. (Reference Soares, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, González-Morales, Martins, Cuenca-Solana and Bailey2016) tentatively reconstructed the ΔR values in northern Iberia during the Upper Palaeolithic using samples from three sites dated from ca. 25,500 to 16,800 yr cal BP. Information available so far concerning the Lower Magdalenian was published by Soares et al. (Reference Soares, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, González-Morales, Martins, Cuenca-Solana and Bailey2016). They obtained a ΔR value of −426±92 14C years (updated to the Marine20 curve using Calib software [Stuiver and Reimer Reference Stuiver and Reimer1993]) from one specimen of Patella vulgata Linnaeus, 1758 limpet recovered at Cualventi cave (Cantabria) (Figure 1) (Soares et al. Reference Soares, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, González-Morales, Martins, Cuenca-Solana and Bailey2016). However, MREs could vary both across time and space (Martins and Soares Reference Martins and Soares2013; Soares et al. Reference Soares, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, González-Morales, Martins, Cuenca-Solana and Bailey2016). Consequently, more studies including samples from other locations along the Cantabrian coast are required to accurately infer local MREs. Furthermore, ΔR values may also vary according to marine species (England et al. Reference England, Dyke, Coulthard, McNeely and Aitken2013; Ferguson et al. Reference Ferguson, Henderson, Fa, Finlayson and Charnley2011; García-Escárzaga et al. Reference García-Escárzaga, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, Cuenca-Solana, González-Morales, Hamann, Roberts and Fernandes2022b; Pieńkowski et al. Reference Pieńkowski, Coulthard and Furze2023; Russell et al. Reference Russell, Cook, Ascough, Barrett and Dugmore2011), thus highlighting the need to consider additional mollusk shell species.

In this study, we present estimates for MREs at ca. 18,000 yr cal BP (Greenland Stadial 2) in northern Iberia using radiocarbon measurements of terrestrial herbivore bones (primarily Capra pyrenaica and Cervus elaphus) and marine mollusk shells (P. vulgata and Littorina littorea Linnaeus, 1758). These intertidal gastropods represent the most abundant molluskan taxa in Upper Palaeolithic coastal sites in the Cantabrian Region (Álvarez-Fernández Reference Álvarez-Fernández2011; Gutiérrez-Zugasti et al. Reference Gutiérrez-Zugasti, Cuenca-Solana, García-Escárzaga and Revilla2024). Our aim was to obtain ΔR values for these two species to accurately date Lower Magdalenian human occupations in the Cantabrian Region and more specifically in the Sella River valley. Following the pioneering study by Macario et al. (Reference Macario, Souza, Aguilera, Carvalho, Oliveira, Alves, Chanca, Silva, Douka, Decco, Trindade, Marqués, Anjos and Pamplona2015), which employed Bayesian modeling for ΔR determination, latter also employed by García-Escárzaga et al. (Reference García-Escárzaga, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, Cuenca-Solana, González-Morales, Hamann, Roberts and Fernandes2022b), we estimated local ΔRs using a Bayesian model combining radiocarbon measurements and stratigraphic information.

Materials and methods

Radiocarbon dated archaeological remains reported in this study were recovered from the Tito Bustillo cave (Figure 1). The site, discovered in 1968, is located in the village of Ribadesella (43º27′35″N–5º23′10″W) at 200 m from the current estuary of the Sella River and approximately one kilometer from the present-day coastline. The cave has a length of approximately 550 m in the East-West direction (Supplementary Planimetry). Neighboring archaeological sites (Figure 1) include the caves of Les Pedroses, La Lloseta and El Cierro (at a distance of 1km) and Cova Rosa (at a distance of 4.5 km) (Jordá-Pardo et al. Reference Jordá-Pardo, Martín-Jarque, Portero and Álvarez-Fernández2022). Systematic excavations of Magdalenian levels were carried out in 2020, 2022, 2023, 2024 and 2025 following archaeological interventions developed 25 years ago in the so-called Living Area (Moure Reference Moure1990) (Supplementary Plan). Recent archaeological campaigns have allowed us to clarify the contexts of previous excavations and document older occupations of the cave (Álvarez-Fernández et al. Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Bécares, Cueto, Uzquiano, Jordá Pardo and Arias2015, Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Cueto, Tapia, Aparicio, Douka, Elorza, Gabriel, García-Ibaibarriaga, Murelaga, Suárez-Bilbao and Arias2018, Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Tapia, Arias, Camarós, Cerezo-Fernández, García-Alonso, Martín, Martín-Jarque, Peyroteo-Stjerna, Portero, Teira, Cueto, Jordá Pardo, Martín-Jarque, Portero and Álvarez-Fernández2022).

The stratigraphic sequence of the Living Area has just over one meter depth, and can be divided into two large sedimentary sections: 1) the upper part is composed of successive dark clay deposits (SUs 201 to 208) with abundant remains (terrestrial mammal bones, charcoal, mollusk shells and bone and lithic artifacts); 2) while the lower section is formed by grey clays with a lower abundance of archaeological materials (SUs 209-210, and SUs 103 to 105), interspersed with thin layers of brown clays likely resulting from more sporadic occupations. In this lower section, stratigraphic analysis identified five coeval pits, each containing different fillings (SUs 106, 107, 108, 109 and 111) (Figure 2). The contemporaneity of these structures is assumed from the stratigraphic relationships they share, as the pits are cut into and included between the same two continuous strata (more information on the stratigraphical sequence is available in the Supplementary Text and Supplementary Figures).

Figure 2. Harris matrix of the sequence observed at excavations squares XIVF, XIIE, XIII-XIID and XIIC in the Living Area of the Tito Bustillo cave. Star symbols indicate archaeological units containing samples which were subjected to AMS radiocarbon dating.

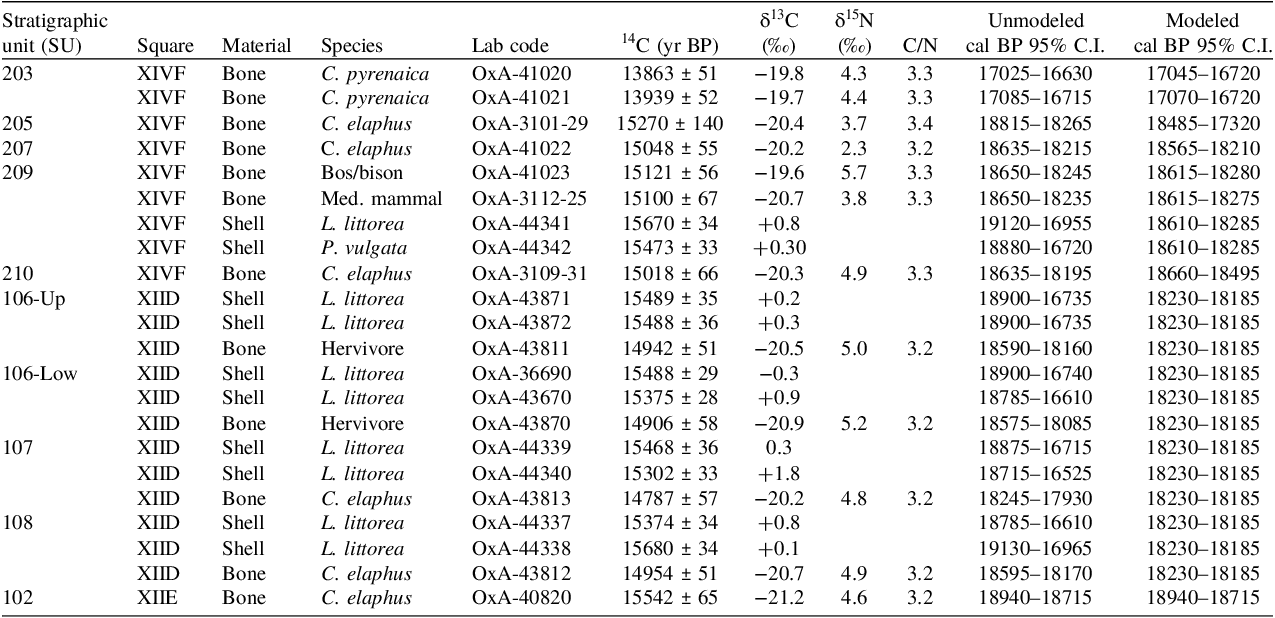

Radiocarbon measurements were done on a total of 22 mammal bone and marine shell samples from nine stratigraphic units dating to the Lower Magdalenian (Table 1). Samples were analyzed at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU) (UK) following standard pretreatment and radiocarbon dating procedures (Brock et al. Reference Brock, Higham, Ditchfield and Ramsey2010). Cleaned mollusk shell remains were reacted in vacuo with phosphoric acid for CO2 release while extracted collagen was combusted to produce CO2. Released CO2 was then reduced to graphite for accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) measurements. Isotopic fractionation corrections were done using δ13C values measured independently via isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham and Leach2004).

Table 1. List of archaeological samples subject to radiocarbon dating and respective results for uncalibrated radiocarbon, carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios, and modeled and unmodeled OxCal date ranges

Bayesian chronological modeling was carried out using the OxCal v. 4.4 software (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009b) and the IntCal20 and Marine20 calibration curves for terrestrial and marine samples, respectively (Heaton et al. Reference Heaton, Köhler, Butzin, Bard, Reimer, Austin, Austin, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Hughen, Kromer, Reimer, Adkins, Burke, Cook, Olsen and Skinner2020; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Butzin, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Hajdas, Heaton, Hogg, Hughen, Kromer, Manning, Muscheler, Palmer, Pearson, van der Plicht, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Turney, Wacker, Adolphi, Büntgen, Capano, Fahrni, Fogtmann-Schulz, Friedrich, Köhler, Kudsk, Miyake, Olsen, Reinig, Akamoto, Sookdeo and Talamo2020) (see Supplementary Code). Following, OxCal language, samples from each SU were grouped as Phases (a group of dates that are considered to be part of the same coherent time period but lack internal order) separated by Boundaries (marker for change in chronological order). An outlier general model was used to detect the possible intrusion of samples into a SU (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009b). We assumed that temporal outliers followed a Student’s t distribution with 5 degrees of freedom, and we employed a 0 to 10,000 years scale. The different phases were distributed according to their stratigraphic sequence using the OxCal Sequence (a series of events or phases that are known to occur in a specific order, with no possibility of overlap). Considering that it was not possible to securely establish the stratigraphic relationship between lower units documented at the XIVF square (i.e., SUs 209 and 210) and the pits located at the XIID square (from SU 106 to SU 108) (Supplementary Text and Supplementary Figures), we employed separate sequences (Sequence 1 and 2). Following stratigraphic analysis, SU 102 was considered the oldest archaeological unit for both sequences. SUs 106, 107 and 108 were deposited contemporaneously, and the start and end boundaries of these three pit units were considered coeval. The identification of three closely situated holes in planimetry view makes it possible to delimit an interface that divides SU 103 into two sections (SUs 103T and 103B) (Harris Reference Harris1997). This division has been confirmed by extending the excavation to the adjacent squares, where two additional holes (SUs 109 and 111) have been identified along the same interface (between SUs 103T and 103B-110). Therefore, sequence 1 consists of SU 102, the deepest stratigraphic unit, and three coeval pits (SUs 106, 107 and 108) that post-date SU 102. For sequence 2, there are a series of units in a clear chronological order (SUs 210, 209, 207, 205, and 203), and these are more recent than SU 102. As there is no clear chronological relationship among the three coeval pits SUs 106, 107 and 108 and SUs 210 and 209, we set the start and end dates for SU 102 as matching in sequences 1 and 2 but did not impose any other chronological relationship among the two sequences (Supplementary Code). Mollusk samples were assigned a wide uniform ΔR prior between –800 and 800 14C yr.

Results and discussion

Bayesian modeling results for the Tito Bustillo cave (Living Area) indicate that the oldest unit (SU 102) started forming sometime between 19,840 and 18,695 yr cal BP (95% C.I.), while the most recent (SU 203) ended sometime between 17,025 and 16,450 yr cal BP (95% C.I) (Figure 3; Supplementary Table). This chronological range is fully within the Lower Magdalenian. These dates corroborate the hypotheses about the chronology of the site based on the revision of the lithic and bone industry from the excavations of the seventies and eighties of the last century in the Living Area that we have been carrying out in recent years (Álvarez-Fernández et al. Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Tapia, Arias, Camarós, Cerezo-Fernández, García-Alonso, Martín, Martín-Jarque, Peyroteo-Stjerna, Portero, Teira, Cueto, Jordá Pardo, Martín-Jarque, Portero and Álvarez-Fernández2022; Cerezo-Fernández et al. Reference Cerezo-Fernández, Cueto, Tapia, Álvarez-Fernández, Markovic and Mladenovic2024; Martín-Jarque et al. Reference Martín-Jarque, Herrero-Alonso, Tarriño, López-Tascón, Prieto, Bécares and Álvarez-Fernández2022). Complete Bayesian estimates for the credible interval for the start and end of each archaeological layer are given in the Supplementary Table together with mean and median date estimates plus a sampled reference for each layer.

Figure 3. Bayesian modeling results for the Tito Bustillo cave (Living Area). Modeled chronology for (a) stratigraphic sequence 1 and, (b) stratigraphic sequence 2. Both graphs were generated using software OxCal v. 4.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a, 2009b) and the calibration curves IntCal20 and Marine20 (Heaton et al. Reference Heaton, Köhler, Butzin, Bard, Reimer, Austin, Austin, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Hughen, Kromer, Reimer, Adkins, Burke, Cook, Olsen and Skinner2020; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Butzin, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Hajdas, Heaton, Hogg, Hughen, Kromer, Manning, Muscheler, Palmer, Pearson, van der Plicht, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Turney, Wacker, Adolphi, Büntgen, Capano, Fahrni, Fogtmann-Schulz, Friedrich, Köhler, Kudsk, Miyake, Olsen, Reinig, Akamoto, Sookdeo and Talamo2020).

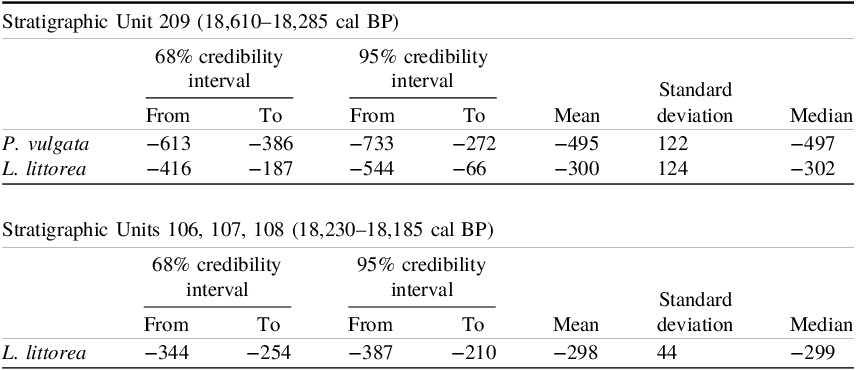

The employed Bayesian chronological model produced distinct ΔR estimates for L. littorea specimens from coeval pits (SUs 106, 107 and 108) and from SU 209 (Table 2). The mean ΔR values obtained for coeval pits (–298±44 14C yr) and SU 209 (–300±124 14C yr) are almost the same and ΔR credible intervals overlap within 68% and 95% credible intervals (Figure 4). The ΔR credible intervals observed for the coeval pits (between –344 and –254 14C yr [68% C.I.] and between –387 and –210 14C yr [95% C.I.]) are smaller than those obtained for SU 209 (between –416 and –187 14C yr [68% C.I.] and between –544 and –66 14C yr [95% C.I.]) (Table 2, Figure 4). The larger ΔR credible intervals from SU 209 are likely due to the low number of marine specimens radiocarbon dated in this unit (n = 1) compared to those dated from the coeval pits (n = 8), rather than to changes in the coastal environments between the deposition of SU 209 (18,610–18,285 yr cal BP) and the coeval pits (18,230–18,185 yr cal BP). Although a gradual improvement in climate conditions has been inferred, using both regional and global proxies (e.g., Jones et al. Reference Jones, Marín-Arroyo, Rodríguez and Richards2021; Rofes et al. Reference Rofes, Murelaga, Martínez-García, Bailon, López-Quintana, Guenaga-Lizasu, Ortega, Zuluaga, Alonso-Olazabal, Castaños and Castanos2014; Seierstad et al. Reference Seierstad, Abbott, Bigler, Blunier, Bourne, Brook, Buchardt, Buizert, Clausen, Cook, Dahl-Jensen, Davies, Guillevic, Johnsen, Pedersen, Popp, Rasmussen, Severinghaus, Svensson and Vinther2014), from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Lower Magdalenian (ca. 26–19 ka cal BP) there is no evidence of short-term abrupt oscillations in local marine environmental conditions during the formation of coeval pits and SU 209 (Martínez-García et al. Reference Martínez-García, Bodego, Mendicoa, Pascual and Rodríguez-Lázaro2014, Reference Martínez-García, Rodríguez-Lázaro, Pascual and Mendicoa2015). Similarly, results from Stanford et al. (Reference Stanford, Hemingway, Rohling, Challenor, Medina-Elizalde and Lester2011) also indicate that marine environments were likely stable during the formation of both archaeological assemblages, since the rate of sea-level rise in the northern Iberia did not begin to accelerate until just after 17 ka cal BP.

Table 2. ΔR results for Patella vulgata and Littorina littorea shell species from the Tito Bustillo cave. Species-specific ΔR values are reported for SU 209 and coeval pits (SUs 106, 107 and 108)

Figure 4. Credible intervals (C.I.) for Bayesian estimates of ΔR for Littorina littorea shells recovered from coeval pits (SUs 106, 107 and 108) (18,230–18,185 yr cal BP 95% C.I.) and Littorina littorea and Patella vulgata recovered from SU 209 (18,610–18,285 yr cal BP 95% C.I.).

Given that the mean ΔR estimates obtained for three coeval pits and SU 209 are almost identical, and the difference between standard deviations is not related to changes in marine environmental conditions, the higher precision ΔR estimate for L. littorea specimens from coeval pits (SUs 106, 107, and 109) (–298±44 14C yr) was selected as a reference for MRE corrections in radiocarbon measurements on L. littorea samples recovered from Lower Magdalenian stratigraphic units in northern Iberia.

For P. vulgata species, the ΔR credible intervals obtained for SU 209 ranged between –613 and –386 14C yr (68% C.I.) and between –733 and –272 14C yr (95% C.I.). These overlap with the ΔR credible intervals for L. littorea species from the same SU at both 68% and 95%. However, P. vulgata ΔR credible intervals only overlap with L. littorea ΔR credible intervals from coeval pits, which were proposed as the reference for future studies, at 95% credible intervals (Table 2, Figure 4). In contrast to previously published results by García-Escárzaga et al. (Reference García-Escárzaga, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, Cuenca-Solana, González-Morales, Hamann, Roberts and Fernandes2022b), who reported a relative 14C depletion in limpets compared to topshell Phorcus lineatus (da Costa 1778), the results obtained herein suggest that periwinkle L. littorea incorporates carbon with smaller 14C content than coeval P. vulgata limpets. For this reason, a different ΔR value for correcting MRE than that given for L. littorea species should be used in future archaeological investigation. We propose to employ –495±122 14C yr in the case of P. vulgata specimens. These results have important implications for future archaeological research in the region, indicating that distinct ΔR values must be applied depending on the species chosen for radiocarbon dating.

Previous research on ΔR variability for marine mollusk taxa has yielded different results. Ascough et al. (Reference Ascough, Cook, Dugmore, Scott and Freeman2005) did not find statistically significant differences in ΔR values between taxa, while Ferguson et al. (Reference Ferguson, Henderson, Fa, Finlayson and Charnley2011), England et al. (Reference England, Dyke, Coulthard, McNeely and Aitken2013) and García-Escárzaga et al. (Reference García-Escárzaga, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, Cuenca-Solana, González-Morales, Hamann, Roberts and Fernandes2022b) reported differences in ΔR values according to species. Different hypotheses have been proposed to account for such differences, including variability in the amount of metabolic carbon incorporated into shell carbonate, and differences between radiocarbon values for dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and metabolic carbon (Fernandes and Dreves Reference Fernandes, Dreves and Allen2017). A recent study showed that the ΔR value for P. vulgata was significantly higher than for P. lineatus in modern and sub-fossil shells from the northern Iberia (García-Escárzaga et al. Reference García-Escárzaga, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, Cuenca-Solana, González-Morales, Hamann, Roberts and Fernandes2022b). This was attributed to differences in the ingestion of carbonate from the rocky background. In our current study, L. littorea showed a higher ΔR value than that obtained for P. vulgata. A similar interpretation is possible, although this would imply that the ingestion of old carbonates by L. littorea is even higher than that by P. vulgata. However, further research is required to confirm whether this is the mechanism behind the observed differences.

The ΔR value estimated in our study for P. vulgata (–495±122 14C yr) closely matches that reported by Soares et al. (Reference Soares, Gutiérrez-Zugasti, González-Morales, Martins, Cuenca-Solana and Bailey2016) for the same species and chronology from Cualventi Cave in Cantabria (Figure 1). Given the 80 km distance between Cualventi and Tito Bustillo Cave, this similarity suggests stable oceanographic conditions across the central northern Iberian Peninsula during the Lower Magdalenian.

Conclusions

Using Bayesian modeling of radiocarbon data and stratigraphic information, we constructed a chronology for stratigraphic units at the Tito Bustillo site in the northern Iberian Peninsula. Modeling results show that the stratigraphic sequence of the Living Area excavated so far was formed between ca. 18.9 and 16.9 ka cal BP, and some of the stratigraphic units could have been occupied for extended periods. MRE during the Lower Magdalenian period in northern Iberia was estimated for two different gastropod taxa: L. littorea and P. vulgata. As the results indicate a significant difference between ΔR values obtained for the two species at 1-sigma, we propose using the following ΔR values for correcting the radiocarbon measurements on shells from Lower Magdalenian stratigraphic units in northern Iberia: –298±44 14C yr for L. littorea and –495±122 14C yr for P. vulgata. It is essential to note that the ΔR values calculated in this study are applicable only to Marine20 curve and should not be utilized with previous or subsequent calibration curves.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2025.10175

Acknowledgments

This work was undertaken in the context of the PaleontheMove Project PID2020-114462GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (PI: E. Álvarez Fernández), funded by the Programa Estatal de Fomento de Generación de Conocimiento y Fortalecimiento Científico y Tecnológico of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and the Palarq Foundation–Aplicación de metodologías y técnicas de las ciencias experimentales/analíticas en Arqueo-Paleontología 2022. We sincerely thank the Regional Ministry of Culture, Language Policy, and Sports of the Government of Asturias. During the development of this research AGE was funded by European Commission through a Marie Skłodowska Curie Action Fellowship (NEARCOAST, https://doi.org/10.3030/101064225) and he is currently funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ESF+ through a Ramón y Cajal Fellowship (RYC2023-044279-I). Finally, we also thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions, which significantly improved the quality and clarity of this manuscript.