Introduction

The Morrison government's political recovery eroded during 2021. Its response to successive COVID-19 waves was flat-footed and the government was paralysed by its handling of two alleged sexual assault cases among other scandals. The government was also occupied by national security concerns, principally China's rise in the Indo-Pacific. Morrison succeeded in adopting a net-zero-by-2050 policy and the budget deficit continued to grow.

Election report

Regional elections

Elections on 13 March, in Western Australia (WA) saw the Australian Labor Party (ALP) win a resounding victory, claiming 53 of a possible 59 seats with 59.9 per cent of the vote (Western Australian Electoral Commission 2021). The Liberal Party of Australia (LP) was reduced to two seats, and the National Party (NP) had four. In Tasmania, the incumbent LP was returned to office with 13 seats and 48. 7 per cent of the vote. Labor won nine seats, the Australian Greens (AG) two and one new independent was elected (Tasmanian Electoral Commission, 2021).

Cabinet report

There were three reshuffles in 2021 (Table 1). The first was precipitated by the alleged rape of former Liberal political adviser Brittany Higgins in the office of the Defense Minister, and an accusation of an alleged historical sexual assault against Attorney-General Christian Porter, which he strenuously denies. After protracted debate, the government conceded that Porter could not act as first law officer of the land in good faith. The Prime Minister used this reshuffle to promote Karen Andrews as the first female Home Affairs Minister and reorganized several other portfolios.

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Morrison II in Australia in 2021

Note: The ruling coalition consists of the LP, NP, the Queensland-based Liberal National Party (LNP) and the Country Liberal Party (CLP) of the Northern Territory. LNP members select to sit in either the LP or NP party rooms and are therefore counted as either LP or NP. CLP members always attend the LP party room.

Source: Australian Parliamentary Handbook, Ministry Lists; https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Parliamentary_Handbook/Current_Ministry_List/Previous_Ministry_List.

A challenge by former NP leader Barnaby Joyce against the hapless Michael McCormack precipitated the second reshuffle. Joyce brought back disgraced minister Bridget McKenzie and booted factional enemies from the Cabinet. Morrison returned Melissa Price to the Cabinet (she was demoted after the 2019 election), taking the total number of women to eight – the highest ever.

Christian Porter resigned after it emerged he had accepted large anonymous donations via a blind trust to pay his legal fees in his defamation case against the Australian public broadcaster (ABC) resulting from reporting of an alleged historical sexual assault. During this final reshuffle, Morrison elevated factional ally Alex Hawke into the Cabinet, bringing the total number to 24 members, violating the convention of 23 Cabinet ministers.

Parliament report

The defection of Craig Kelly (LP) on 22 February 2021 reduced the coalition to 76 members out of 151. The government no longer had a working majority in the lower house (the government supplies the speaker by convention) (Grattan Reference Grattan2021).

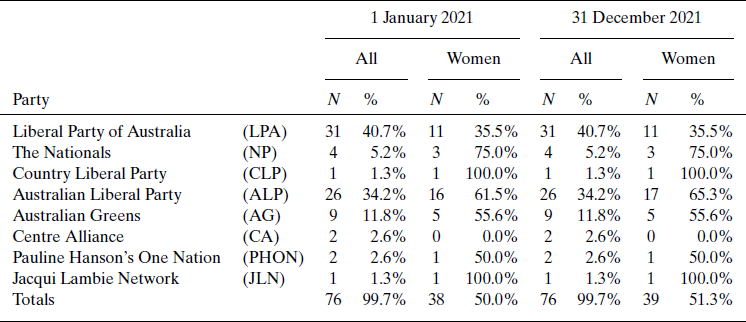

In the Senate, three casual vacancies (two retirements and one death) saw the gender composition change, with one Labour female Senator replacing a man in the upper house.

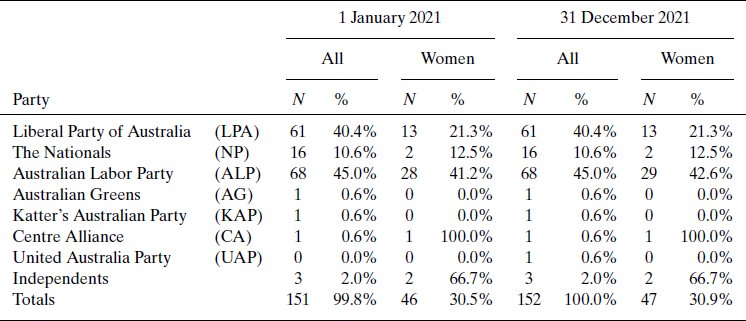

For data on the composition of both houses of Parliament, see Tables 2 (Lower House) and 3 (Upper House).

Table 2. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Parliament (House of Representatives) in Australia in 2021

Note: Craig Kelly defected from the LP in February 2021. He first became an independent, but later joined the UAP in August 2021.

Source: Parliamentary Handbook (2021), https://handbook.aph.gov.au/Elections.

Table 3. Party and gender composition of the upper house of the Parliament (Senate) in Australia in 2021

Note: There were three ‘casual vacancies’ in 2021. Senators S. Ryan (LP) and R. Siewert (GRN) retired and were replaced by senators of the same sex. Senator A. Gallacher (ALP) died and was replaced by a female ALP senator, changing the sex composition of the Senate.

Source: Parliamentary Handbook (2021), https://handbook.aph.gov.au/Elections.

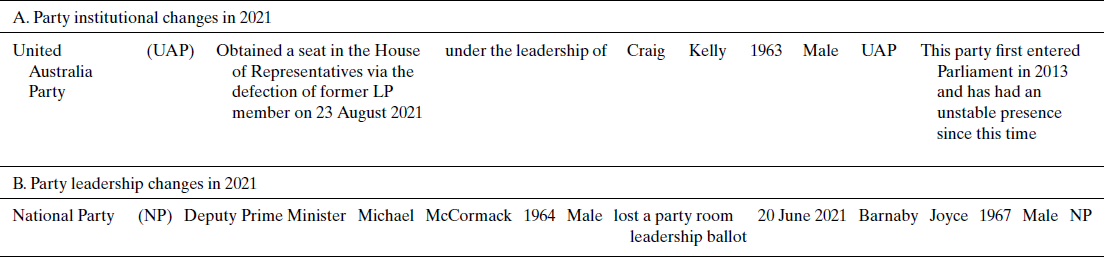

Political party report

Defector Craig Kelly joined the United Australia Party (UAP) on 23 August 2021, after six months as an Independent, changing the party composition of Parliament. The UAP was absent from the lower House since the defeat of billionaire founder and mining magnate Clive Palmer, who retired prior to the 2016 elections. Palmer spent A$83 million on advertising during the 2019 election (by contrast, Labour spent A$50 million and the Liberals A$48 million) (Australian Electoral Commission 2020).

Former NP leader Barnaby Joyce launched a second challenge against incumbent Michael McCormack and secured a bare majority of 11 votes to 9. Joyce's return as NP leader also meant he again became Deputy Prime Minister.

For data on changes in political parties, see Table 4.

Table 4. Changes in political parties in Australia in 2021

Source: Parliamentary Handbook (2021), https://handbook.aph.gov.au/Elections.

Institutional change report

Changes in state populations in WA and Victoria triggered a redistribution of seats within both states. Victoria gained a new ‘safe Labour’ division, Hawke, named after former Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke. The Liberal-held division Stirling (WA) was abolished. The government failed to progress its promised anti-corruption agency: the Commonwealth Integrity Commission.

The Electoral Act was amended, including increasing the number of members a political party must have before registering (from 500 to 1500 members) (Australian Electoral Commission 2022). The change aimed to reduce the number of parties running at elections, but grandfathered existing parties. The government also introduced legislation to require voters to carry personal identification before voting and to change Australia's voting system from preferential (alternative vote) to optional preferential (Australian Electoral Commission 2022). Neither bill passed Parliament.

The Morrison government committed to enacting the recommendations of the Jenkins Report (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2021) into parliamentary culture. These recommendations would change the conditions under which politicians and their political advisers work.

Issues in national politics

Women's safety within Parliament House and wider society was the dominant issue in 2021 alongside the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The alleged rape of former political adviser Brittany Higgins and allegations of historic rape allegations against the Attorney-General sparked nationwide protests, several inquiries (Hill, Reference Hill2021) and a landmark report into the culture of Parliament (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2021). The Morrison government's inability to meaningfully engage on this subject saw the scandal and political turmoil drag on for months, eroding the polling dominance of both the Prime Minister and the government.

The government made the fateful decision to retain control of the COVID-19 vaccination rollout by using the network of general practitioners, which it funded, instead of delegating this job to subnational governments responsible for running Australia's health systems. The result was a chaotic rollout, compounded by supply shortages and seizures of vaccines in transit by third countries. The Delta COVID-19 variant saw national and subnational governments take extraordinary measures: Australia closed its border, threatening gaol time, to Australian citizens attempting to return from India (Bucci, Reference Bucci2021). Both Sydney (106 days) and Melbourne (78 days) enforced long lockdowns. In total, Melbourne has endured over 250 days of lockdown since the pandemic's start (Campbell, Reference Campbell2021). In September, violent protests in Melbourne featured gallows and calls for the execution of State Premier Dan Andrews.

In a shock announcement, the government abandoned its conventional French-built submarine project and instead entered a new security alliance between the UK, the United States and Australia, called AUKUS. This would grant Australia access to nuclear submarines. The French President accused Morrison of lying and it emerged that Australia would not get its first submarine before the late 2030s (Hartcher, Reference Hartcher2021).

The Morrison government committed to net-zero emissions by 2050 at the Glasgow climate summit, but provided no plan to achieve the target (Martin, Reference Martin2021). Morrison engaged in protracted talks with coalition partner, the NP, in order to secure this rhetorical change, promising billions of spending in exchange. The deal damaged perceptions of Morrison's prime ministerial authority. The ongoing debate about inequality and housing continued with only modest progress. The unemployment benefit was lifted by A$25 per week for the first time in over 25 years (Henriques-Gomes, Reference Henriques-Gomes2021). Last, it was found that at least A$27 billion in subsidies from the government's COVID-19 wage subsidy programme, Job Keeper, was given to profitable companies (Wright, Reference Wright2021). The government did not ask businesses to return the money.

The year ended with the government returning to national security, deploying inflamed rhetoric about China. The government positioned itself against ongoing COVID-19 restrictions.

Acknowledgements

Open access publishing facilitated by Australian National University, as part of the Wiley – Australian National University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.