Introduction

An anonymous writer, evocatively described in 1911 a September night of open-air singing around a campfire following an evening walk where dusk had fallen. Like many, they had their account published in Comradeship, the magazine of the Cooperative Holidays Association (CHA):

A roaring camp- fire – surrounded by scarlet blankets that added materially to the comfort of the evening – and copper-red faces! … ‘Friendship’ was never sung with more feeling … Our London Trio charmed the circle with their lovely ‘Lagoon Song,’ the swell and cadence fitting delightfully the fire flames, the whisper of the wind and the beck’s bright flowing chatter … mirth and song illumined the mind as the flare-torches of dead gorse lighted the gipsy band.Footnote 1

The singing of the song ‘Friendship’ from the CHA’s own song book highlights the role of fellowship which the organisation saw as a key feature along with the sensory elements of a roaring fire, scarlet blankets, flickering light and the human voice intermingling with natural sounds of wind and water. The experience of darkness may have played a role here too, opening up new kinds of socialities and bringing non-visual senses to the fore in a way that can evoke different ways of connecting with place and other people.Footnote 2 This was clearly both an evocative emotional and sensory moment in time captured in words and one which points towards the key themes that we will be discussing within this Element: singing, sociality, the body and place. These intersect environmental, health, social and cultural histories, highlighting the complex interactions involved in outdoor singing within group settings over time.

Open-air singing as an activity highlights the interactions between bodies, places, groups of people and other species, as well as a subject that brings to the fore cultural and social contexts. In this Element we bring together sensory and emotional history approaches to enable insight into the ways in which open-air singing has been practiced and experienced both in the past and in the present; through the open-air singing practices and experiences of outdoor recreation groups and organisations based in the north of England in the early twentieth century. This work emerged from historical research into the development, use, and experience of public paths and trails in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.Footnote 3 Ben Harker has highlighted that open-air singing was already part of rambling culture and actions to open-up access to the countryside in the 1930s, in his work on the folk singer Ewan MacColl.Footnote 4 Whilst this provides a political lens on the links between open-air singing and rambling, this intersection is underexplored from a sensory and emotional historical perspective.

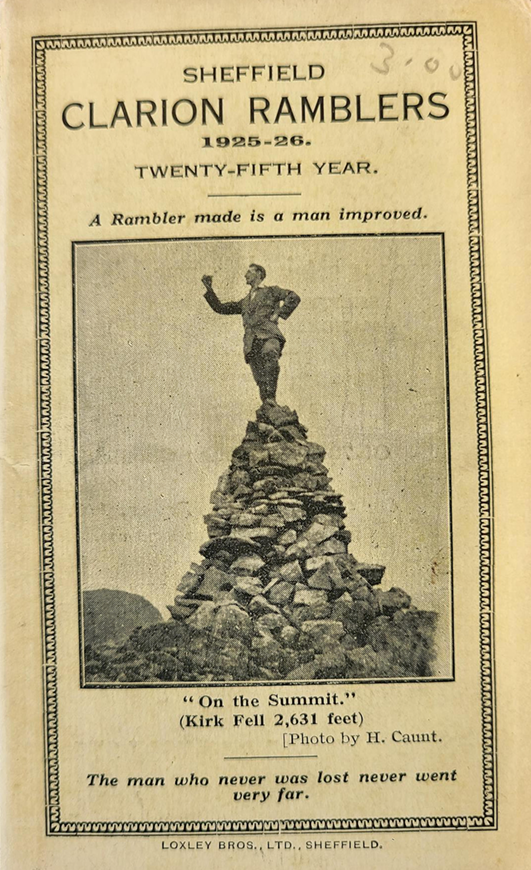

Our key historic sources are publications from the Sheffield Clarion Ramblers (SCR), the co-operative holiday movement (incorporating both the CHA and the Holiday Fellowship [HF]) both of which were active in the early twentieth century and had strong connections with the countryside around the urban centres of Manchester and Sheffield. Our geographic focus is chosen in part because of the historical importance of these landscapes of open-air leisure and recreation for people from these cities. Where appropriate, we have also used supporting material from other, like-minded groups, involved in open-air recreation during this period. Although different in their backgrounds and formation, many of these groups shared a focus on providing meaningful leisure activities for primarily urban working-class men and women (and sometimes younger folk) as a means of personal and social transformation through rational recreation, connecting with nature and immersion in the countryside.Footnote 5 Communal outdoor singing within the landscape (often whilst rambling) was integrated within these groups’ activities. To facilitate this, they published individual songs in their regular publications for members, and collated songs into books of lyrics and music available to purchase (see Figure 1).Footnote 6

Figure 1 The cover of Ward, G.H.B., Songs for Ramblers to Sing on the Moorlands (Sheffield: Sheffield Clarion Ramblers, 1922), featuring an illustration of a pair of walking boots.

Figure 1Long description

The cover of a pocket-sized songbook. The text in the top thread reads “Songs for ramblers to sing on the moorlands”. Below this is a central panel with an illustration of a pair of stout walking boots (one on its side) and a pair of pipes (for smoking) against a light background. In the bottom third is text reading “PRICE 4d.” and “Published by the Sheffield Calrion Ramblers. Edited by G.H.B. Ward. 1922”.

These archival sources, however, are limited in drawing out some of the more personal narratives of the physical experience of singing in these places; therefore, we supplement these with contemporary experiences of collective singing and rambling in landscapes drawn from new qualitative research with a choir who integrate rural and suburban walking within their practice. One of us (Flint) joined the choir on one of their outings for a go-along interview in 2023 – a mobile method which focuses on talking whilst moving in and through environments and aims ‘to (re)place the researcher alongside the participant in the context of the ‘doing’ of mobility’.Footnote 7 There are, of course, clear differences between the experiences of people in the early twentieth century to those in the twenty-first. We are aware that the historical, political, social and cultural contexts as well as the demographics of these groups will be different so we are not suggesting that these experiences will be the same, but rather we aim to bring them into conversation with each other to consider broader questions about bodily movement, singing and interactions with the environment and other people/other species within the landscape over time.

To provide a wider scholarly context for the central register of sound as a sensory category of analysis, we also position our work within a phenomenological understanding of how people experience and construct meaning with the landscapes which comprise their worlds. As Christopher Tilley has stated, these engagements and understandings are ‘grounded in the body itself’.Footnote 8 Being and moving in landscapes, from a phenomenological perspective, is multi-sensory, affective, cognitive and embodied.Footnote 9 Thus, our perceptions of landscape are both mediated and co-constructed through our bodies: ‘we are both in it and of it, we act in relation to it, it acts in us’.Footnote 10 Within this we experience senses altogether rather than consecutively; we simultaneously see, hear, smell and feel aspects of environments. The ethnographer Dara Culhane has noted that ‘attention to sensory experience invites us to re-imagine our minds and bodies, ideas and feelings, not as binaries that are separate from and opposed to each other but rather as actively living in perpetual and dynamic interaction with each other.’Footnote 11 The singing practices of open-air recreation groups were of course part of people’s multi-sensory and embodied engagements with those they were singing with, and the environments they sang within. For instance, writing about her experiences of a CHA holiday in 1933, Miss Phyllis Bell recounted a memorable ‘day when we walked into a thunder-burst, and got soaked, but still went on walking and singing through the rain’.Footnote 12 As well as being a physical process with an audible sensory output, singing and sound can evoke emotional feeling, memories and imaginative connections.Footnote 13 It is impossible to disentangle singing completely from this complex, intersensorial engagement with the world; however, the focus of this Element will be to foreground and bring attention to the role of open-air singing, and how that both contributed to the sonic environments, or soundscapes, of rural and countryside places, highlighting connections with other senses where appropriate.Footnote 14 We also argue that the sensory and the emotional are intertwined and cannot easily be separated. This follows Rob Boddice, who notes the senses are directly tied to a broader conceptual language of ‘feeling’.Footnote 15 Similarly David Howes argues ‘sensory studies plays up the double meaning of the term of “sense”. This term encompasses both sensation and signification, feeling and meaning (as in the “sense” of a word) in its spectrum of referents’.Footnote 16 Our focus on sound and singing recognises that, within this embodied and multi-sensory, phenomenological perspective, sound is integral to how people experience, engage with and make sense of place.Footnote 17 We are, therefore, interested in the role of open-air singing in how people constructed, understood and even challenged conceptions of the English countryside.

Diverse forms of singing are a core part of human experience and their origins may stretch back over a million years. For instance, the value of group singing was recorded in Babylonia in the nineteenth century BCE.Footnote 18 It is a form of expression across human life cycles: from the lullabies sung to new-borns to the mourning songs of burial practices. Communal singing can share emotions and spirituality; it can create empathy, bolster identity and the boundaries of belonging, or challenge and protest social norms.Footnote 19 Open-air communal singing has been part of many spheres of human social life, including the traditional songs that find their origins in the rhythms of agricultural work and singing practices associated with team sports, such as football chants.Footnote 20

Attention has been paid to the role of singing in relation to health, nature and emotions by social scientists as discussed by Sarah Bell, Clare Hickman and Frank Houghton in their survey on work relating to the concept of therapeutic sensescapes. They argue that although most research focuses on the sounds of nature or quiet spaces, there is work on the importance of music ‘as well as a sense of connection experienced while singing in park and woodland settings’.Footnote 21 In the case of one Belgian study a ‘participant explained the sense of freedom of exteriorising emotions at the coast through screaming, crying and singing, gaining a sense of peace in the process’.Footnote 22 As Bell et al. noted quoting Duffy et al., ‘this work suggests value in examining the role of sound in shaping “the euphoria of communicating back-and-forth between the self and others … the sensation of becoming part of a collective – or one shared body” through more-than-human social and sonic landscape encounters’.Footnote 23

Although very aware of the particular historical contingencies of our material, the use of historic as well as contemporary sources and voices will add to this literature on the emotional, therapeutic and sometimes exclusive rather than inclusive role of out-door singing. As Hedley Twidle and Aragorn Eloff argue, ‘The ability of sound to pass through (and to behave differently in) different bodies, substrates, and environments makes it an intriguing and often surprising way to think through received categories and boundaries, whether “natural” or “cultural”.’Footnote 24 We also recognise that these sonic experiences and expressions are highly contextual and dynamic: the ‘phenomenal properties of sound are not fixed and universal; rather they are actively produced by the performative relations of making music’.Footnote 25

Many of the emotional experiences described in our source material relate to community and fellowship through membership of a group. This sits within a wider literature where, as Katie Barclay has outlined, ‘group cultures are also an important location for emotion, allowing people to form “refuges” of feeling within systems where they were excluded (such as in some gay subcultures), or giving shape to the dynamics of particular environments’.Footnote 26 Our focus on singing communities allows us to consider how emotions are shaped and experienced in relation to this shared physical sensory activity as well as the wider political, social and cultural pressures which also shape the group dynamics. As Mark Smith argues, there is a strong historical interrelationship between the development of social and sensory history.Footnote 27

In terms of environmental history, as Peter Coates has outlined, ‘at the risk of stating the obvious, all aural history is environmental in that it deals with sounds in physical settings, whether indoors or outdoors’, which is a good starting point for our foray into the intersections of bodies, communities, places and other species as experienced through outdoor singing.Footnote 28 Attending to sound in environmental history not only ‘invites us to listen across time’ but to also attend to the entanglement of human and other-than-human elements of soundscapes.Footnote 29 Victoria Bates has noted that ‘‟soundscape” remains a useful shorthand. It refers simultaneously to the different sounds that – when perceived, through feeling and/or hearing – make up the profile of a given space or place, and it brings together the material and social aspects of sound’.Footnote 30 However, as Gaynor et al. note, environmental historians are only recently making ‘emotion a central category of analysis’.Footnote 31 We, therefore, hope to add to the growing body of work discussing the role of emotions, as well as the senses, in relation to human–environment interactions.

In this Element we focus on three key areas to consider the sensory and emotional histories of open-air singing in the early twentieth century. The first places the bodily experience at the centre of the discussion and examines the various ways in which the body relates to the environment, primarily via the air as well as to others through the physical act of singing. The second explores the creation of fellow feeling through song and its ability to both include and exclude others as well as develop relationships beyond the human. The third key section focuses on the sensory and emotional relationships to place that are both created and memorialised via song as well as the role that sound and singing play in contested ways of being in the countryside that this examination reveals. Finally, we consider the contemporary connections and resonances through the former three themes to move beyond the archival historical research to ask what the experience of singing groups today can tell us about relationships to their bodies, other beings and places. Our conclusion looks forward and asks what future research might achieve by taking these approaches to considering the role of outdoor song in both the past and present.

1 Sensing and Feeling the Landscape via the Body

The exercise of Synging is delightful to Nature and good to preserve ye Health of Man. It doth strengthen all parts of ye brest and doth open ye pipes.

The foreword of the song book Songs by the Way, produced by and for members of the HF in the 1920s, opens with the quote above by the composer William Byrd. Taken from two statements in 1588 published within Byrd’s own songbook, Psalmes, sonets, & songs of sadnes and pietie, as part of a list of ‘Reasons briefely set downe by th’ author to perswade everyone to learne to sing’.Footnote 33 This not only demonstrates the long history of singing as a practice understood in connection to physical health and breath but also the ways in which twentieth-century organisations, such as the HF, were positioning their own practice of singing in relation to Byrd’s argument.

The use of this approach in the 1920s is particularly interesting as the first decades of the century saw a renewed interest in ‘natural’ open-air exercises for health including ‘games, swimming, field sports, and dancing’, which were promoted by many medical practitioners including the then Chief Medical Officer, Sir George Newman.Footnote 34 For organisations like the HF and various rambling and holiday societies, this also included the joint activities of walking and singing. In many ways this emerged out of late nineteenth-century Christian muscularity which encouraged the development of a strong healthy body through sport, as well as a growing sense of bodily health related to breath and song expressed by some medical practitioners.Footnote 35 This section aims to place the physicality of the singing body at the centre of the discussion and to consider how conceptions of air, breath, song and movement were connected to each other as well as the surrounding environment.

1.1 Air and the Body

As the scholars Tatiana Konrad, Chantelle Mitchell and Savannah Schaufler have recently written, ‘air is a consistent biological necessity, indispensable to human and more-than-human beings, to life and survival’, as well as something that at the same time is ‘materially and ideologically complex; at once an environmental and scientific concern, …, and register of entanglement, relation, and well-being’.Footnote 36 It is therefore both simple in its indispensability and complicated in its relationality to the environment and other living beings. The first and last breaths we take are the key moments marking the beginning and the end of life – it punctuates everything. As Konrad et al. write, ‘breath as a bodily function, in which each inhalation registers direct contact with the external world, sees the alveoli, pleural cavity, the branches of the lungs, as sites of exchange – with air at once both inside and outside’.Footnote 37 The body is made permeable through many mechanisms, but the rhythmical process of breathing is a key method by which we are all physically connected to our environment.

Air, however, has not always been conceptualised as one single element and it has existed in multiple contexts. For example, the ancient Greek Hippocratic tradition distinguished between different types of air: there was external air (aer, eeros) and external wind (pneuma, anemos), as well as inner wind or breath (pneuma, physa).Footnote 38 The importance of the relationship between the environment and the body in early medicine is even captured in the title of one of the key Hippocratic works, Airs, Waters, Places. Although, by 1733, at a time of great interest in the physical properties of air, the physician John Arbuthnot could complain that physicians, unlike Philosophers, Mathematicians, Chemists and ‘Professors of Agriculture and Garden’, had not paid enough attention to the effects of air on the body.Footnote 39 The reason for this lack of interest he suggested was that ‘air is of those Ingesta, or things taken inwardly, which neither can be forborn nor measur’d in Doses’.Footnote 40 This highlights the historical complexities of something which is essential for life, is everywhere and is therefore taken for granted and yet cannot be easily controlled in terms of how much crosses the boundaries of our bodies. As Christopher Sellers, has argued ‘both environmental and medical historians can seek to understand the past two centuries of medical history in terms of a seesaw dialogue over the ways and means by which physicians and other health professionals did, and also did not, consider the influence of place – airs and waters included – on disease’.Footnote 41 Given our focus on modern Britain we will limit ourselves here to noting just these examples from the Western medical tradition, but we recognise that other cultures and times have also had their own conceptions and understandings of the relationship of air and the body in terms of health given its centrality to life.

Breath, speech and song are all interconnected physiological processes, as at the most basic level they all involve the inhalation and expulsion of air via the lungs. The main difference between them being whether conscious sound is made through this process, and, if it is, what kind of sound is produced. As Gillian Kayes explains, ‘breathing and phonation [vibration initiated by the vocal folds] are closely linked in vocal function: in singing and speech production the sound source can be “voiced” – a result of vocal fold vibration – or “unvoiced” – a result of air passing through a constriction above the vocal folds’.Footnote 42 The physicality of singing with its focus on a particularly high physiological use of air in comparison to general breathing emphasises this bodily connection with the external environment and is often viewed as a process by which health can be improved or restored.

As contemporary voice scholars Jing Kang, Austin Scholp and Jack Jiang note, ‘recent years have witnessed an incremental recognition of the value of singing activities in improving mental and physical health in both nonclinical and clinical settings’.Footnote 43 Although they also recognise that these are not new ideas and trace these origins back to the early twentieth century, stating that ‘as early as 1930, Rollrath found that many famous singers had lived to be 80 or even more than 100 years old, which suggested that singing could increase longevity’.Footnote 44 As we have seen above Byrd was already making connections about improving physical health by singing in the sixteenth century, but the idea of tying the physical act of singing to health and longevity fits within a wider narrative found in this early twentieth-century period of the role of air in relation to both exercise and, as we will explore here, singing outdoors. Potential reasons for longevity worth noting were not only confined to the practice of singing – the air itself was considered a factor. For example, in the 1959–60 SCR handbook numerous instances of longevity in Derbyshire were linked specifically to the air itself.Footnote 45 Although the type of quality of the Derbyshire air is not specified in this piece, we can safely assume that what is implied is rural or country air rather than that which is found in urban settings.

Ideas concerning health and rural leisure activities in the early twentieth-century were part of a cosmology of understanding where urban conditions were deemed unhealthy in contrast to the widely imagined countryside as a source of health and wellbeing. This reflects what Bill Luckin and Keir Waddington have described as the pro-rural/anti-urban sentiment that emerged in the nineteenth century and was strengthened by the concerns around physical and mental degeneration of the population at the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 46 One widespread concern related in particular to the high rates of Tuberculosis (TB) which reached their height in Europe towards the middle of the century. It is thought that in 1850 tuberculosis was responsible for one in four deaths worldwide and, according to Richard Morris, ‘until the 1870s it was the number one killer of Britons’.Footnote 47

As TB predominately affects the lungs, one central medical concept which emerged was that time spent in the ‘open-air’ (preferably rural or coastal outdoor air) should be viewed as an essential preventative and therapeutic approach for dealing with this and other related diseases. There were variations on what this meant in practice, but generally this led to patients spending as much time as possible in outdoor settings, even tents and wooden chalets, to obtain the maximum amounts of fresh air and sunshine. This became intertwined with ideas about healthy outdoor recreation and access for urban dwellers to more rural spaces.Footnote 48 As E. A. Letts argued in his 1892 lecture, The Air We Breathe: ‘we live in air, and to a certain extent on air, for it is continually flowing into our blood. No wonder, then, that we are influenced by climate, which means the condition of the air’.Footnote 49 This is echoed in recent work on air which conceptualises it as the ‘medium and breathing the mechanism through which the outside environment is embodied. Air carries the weather, climate and particles from the environment into the body. Humans embody the climate of their environment through air, just as fish embody the climate of their environment through water’.Footnote 50

Similarly, in his introduction to the book How to Conquer Consumption (consumption was another term commonly used for TB), published in 1926, David Masters emphasised these interrelated concerns about air, environment and the body, writing:

People who had been used to working in the open air were imprisoned all day in dusty factories, and whether they were inside or outside, waking or sleeping, the air they breathed was always laden with the impurities that are inseparable from the atmosphere of an industrial centre where factory chimneys and blast furnaces so foul the heavens with fumes and atoms of carbon that all vegetation is stunted within their areas. … The newcomers to industry were denied that breath of pure fresh air which cleansed their lungs and re-oxygenated their blood so long as they lived in the country.Footnote 51

There is a sense of nostalgia in all these pieces for a time before industrialisation and urbanisation when people were more commonly employed as agrarian workers in rural communities. Dr David Chowry Muthu, an Indian physician who established the Mendip Hills Sanatorium in the UK and the Tambaram Sanatorium in India thought a solution to the health issues facing the nation could be found if the Poor Law was abolished and the poor were given free access to the land. He argued that these measures would mean:

more employment in the country, more honourable work done under health-giving conditions … It would mean pure and wholesome occupation to thousands of citizens living in the open air and pleasant sunshine, and engaged in the congenial task of tilling the fields and gathering in the harvest … It would mean that in many a cottage home the family altar would be set up, and a ‘race of pure heart, iron sinew, splendid frame, and constant faith’, would keep alive the bygone traditions of its yeoman fathers.Footnote 52

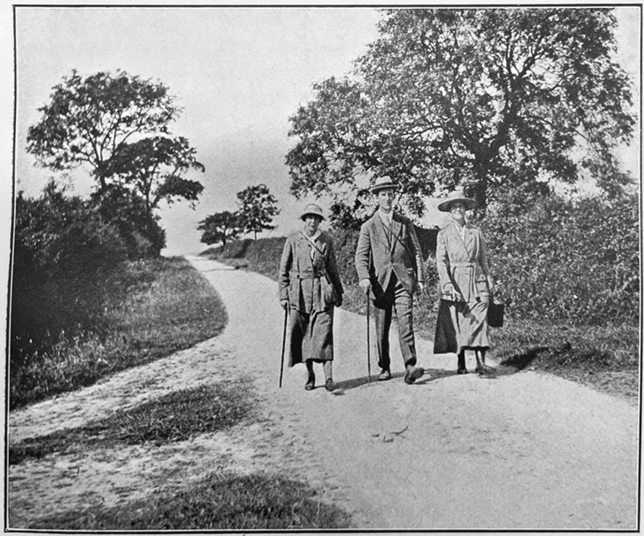

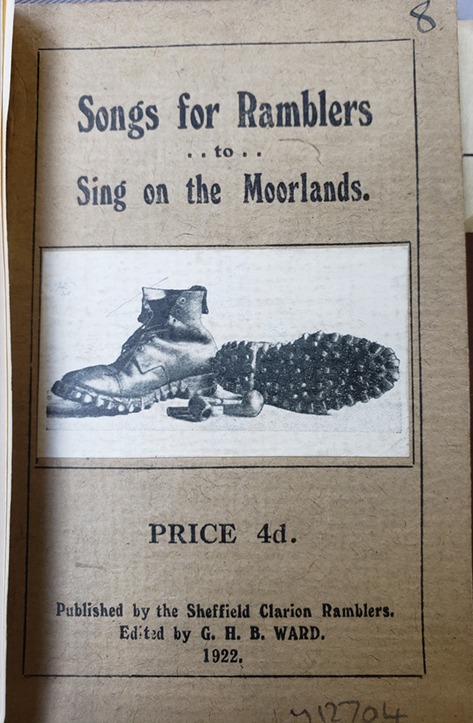

He brought these ideas into his practice by recommending that TB patients that were recovering well should go ‘tramping’ in the countryside (see Figure 2), arguing:

What a change this tramping life would bring to the town-bred patient. The rosy flush of the early dawn, the morning chant of the birds, the sunlit fields and meadows fill him with new delights; while the afterglow of the sunset, the hush of the twilight, the radiance of the starlit sky calm his mind and still his soul into quietness and peace. And as he lies down to rest he nestles close to the bosom of mother Nature and lets her wrap him in dreamless sleep.Footnote 53

Figure 2 Photograph of three patients (two women and one man) in Edwardian dress on a tramping tour or long walk in the countryside.

Muthu, like many physicians treating conditions such as TB at this time, viewed open-air therapies as the answer (as a preventative as well as a therapeutic measure) and argued in 1910 that ‘the secret of its widespread interest in Europe is due to the discovery – if discovery it may be called – that fresh air, hitherto regarded as an enemy to be shut out and barred, is really a friend, and one of Nature’s best gifts to man’.Footnote 54 Others such as the retired Lieutenant, J. P. Muller (previously of the Danish Army), who wrote the book, My Sun-Bathing and Fresh-Air System, also saw this natural method for health as a way to manage the issues brought on by modern life. He argued, ‘Man is subject to more bodily ills to-day than he has ever been before, and it is only natural, when you come to consider it, that the descendants of a race who had to hunt their food before they could eat should not be able to work in a factory or an office without suffering for it in some way or another.’Footnote 55 These pro-rural/anti-urban nostalgic themes were also at the heart of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century movements, including the Arts and Crafts and Garden City Movements.Footnote 56

These ideas are also picked up in G. H. B. Ward‘s 1922, foreword to the SCR’s songbook, Songs for Ramblers to Sing on the Moorlands, where he describes how traditional songs are particularly appropriate for singing outdoors because of their inherent connectedness and resonance with not just the landscape but the open-air itself. Ward writes: ‘what better medium could we desire than the old English country folk song with its simple appeal and the very breath of the countryside in its jingling rhymes’.Footnote 57 This nostalgia for the simplicity of the past as well as the concerns around air and health are brought together in the description of the air as ‘the very breath of the countryside’.Footnote 58 Similarly, the founding ethos of the CHA was in part around the health benefits of rambling and being in the rural open air. Occasionally this made it into the choice of songs by outdoor recreation groups. For instance, the lyrics of ‘On Trek!’ (the marching song of the scouts) include the line ‘Boys, we are going where the clean winds blow!’Footnote 59 Another example published in the SCR songbook ‘A mountain thought’ contains the line ‘The health-born winds about us whirl’, and the line ‘With a heigh-ho! In the fresh air’ is a repeated refrain in the rewrite of ‘Come to the fair’, titled ‘A dinner table song’.Footnote 60

Rural walking was itself encouraged as a healthy practice because of its action on the lungs (see Figure 3). In 1908, an article in The Circle magazine (which was aimed at children within the co-operative movement) titled ‘Pleasures of the Countryside’ extolled the physical virtues of walking in the countryside. The author argued that ‘walking is the most healthful form of exercise, because it brings practically all the muscles of the body into action, while the lungs are refreshed and strengthened by breathing the pure air’.Footnote 61 Along with a discussion of the importance of natural history knowledge and observation, it is clear that getting outside was encouraged for the health of children as well as adults. A short piece entitled ‘On Walking’ in the 1959–60 SCR handbook described how one could not ‘help but feel pity for the townsmen’ who experienced ‘No pleasure in walking, that strengthens the limbs and invigorates the lungs!’Footnote 62 Edward Carpenter, a leading cultural, political and social reformer, was one of those heavily involved in the wider movement to encourage outside recreation. As Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska has discussed in detail, Carpenter delivered a lecture to the Fabian Society titled, Civilization, Its Cause and Cure in 1889, in which he claimed that civilisation was a ‘disease’ that was ‘physical, social, intellectual, and moral’.Footnote 63 He contrasted this by looking at the ‘“higher types of savages” whose “superabundant health” was due to regular “shouting, singing, dancing”, and a culture in harmony with nature’.Footnote 64 As Zweiniger-Bargielowska argues, in Carpenter’s view ‘health was more than a “purely negative” absence of disease. It could only be acquired by the “adoption of a healthy life, bodily and mental”’.Footnote 65 This involved a ‘“return to nature”, a “life of the open air”, “clean and pure food”, and “companionship of the animals”’.Footnote 66 Along with the open air, he recommended sunlight and sunbaths which were also central elements of the sanatoria regimen and chime with the health practices of both Muthu and Muller as discussed above. We have a sense then that Carpenter considered that perfect health could be achieved through physical activities out-doors, ‘in harmony with nature’, including singing which takes us back to Byrd’s quote about singing as ‘delightful to nature’. It is also worth noting here that the founder of the SCR, G. H. B Ward, considered Carpenter a friend and mentor, and quoted his writing numerous times within the pages of the club’s annual handbooks. As such, we can see that Carpenter’s ideas influenced both the practices and ethos of the club.

Figure 3 ‘Come Rambling’: a 1950s poster for The Ramblers’ Association depicting a young (and implicitly healthy) couple walking in a rural landscape.

Figure 3Long description

A poster with the text “Come rambling” at the top, above an image of a young man and woman, smiling and holding hands. They are dressed in rambling clothes: short sleeved shirts and shorts, and walking shoes. The man has a rucksack on and they are walking up hill. Behind them is a farmyard and cottages, and beyond that a hillside marked out into green hills

Carpenter was far from being alone in his belief in the power of singing. In 1901 a US physician, S. A. Knopf, outlined how

Barth, of Köslin, who has made a careful study of the effects of singing on the action of the lungs and heart …, has come to the conclusion that singing is one of the exercises most conducive to health. Considering the fact that it can be practiced anywhere (when the air is pure) or at any time, without apparatus, it should be much more cultivated than it actually is.Footnote 67

Similarly, Muthu recommended singing exercises as an ideal way for TB sufferers to recover their strength arguing that ‘they invoke correct nasal breathing, maintain a better expansion of the chest and a freer passage of air to remote parts of the lung, such as the apices – which are liable to become tuberculous owing to their comparative inactivity – and determine a more efficient supply of blood to these parts, and thus indirectly improve the local and general health’.Footnote 68 He even included breathing and singing exercises at 10.00 am every day in the example given in his book of the daily programme for patients at his sanatorium.Footnote 69 The body was understood to need access to clean, fresh air to fulfil its healthy potential and singing was an easy way to maximise the strength of the lungs and the volume of air inhaled.

Alongside this there were also perceived moral benefits of a closer relationship to nature as both breathing and singing were methods by which the human/environment barrier was constantly breached. As Konrad writes, ‘despite its alleged invisibility and imperceptibility, air is an essential part of the larger environment in which humans exist’.Footnote 70 Ingold similarly argues against seeing the material aspects of the world as mainly landscape and artefacts without the inclusion of air.Footnote 71 Materiality according to him is not just an expression of entanglements between people and ‘things’ but between people and mediums like air and water. This interrelationship between bodies, air and the environment is highlighted in the SCR song ‘An after dinner ditty’, where one of the lines describes how ‘As they strolled across the moorland, on the air their voices rang’.Footnote 72 Here the bodies are moving and physically interacting with the environment in several different ways or as Ingold states, ‘a living, breathing body is at once a body-on-the-ground and a body-in the-air’.Footnote 73

On top of these basic tenets of bodies moving and breathing, we can also layer the changeability and vulnerability of the body to the environment which is perhaps highlighted most through accounts of the sensory experience of weather. As Ingold writes ‘we hear these textures in the rain from the sounds of drops falling on diverse materials, and we touch and smell in the keen wind that – piercing the body – opens it up and sharpens its haptic and olfactory responses’.Footnote 74 Although, as Howes has noted, ‘the body’ is not a singular thing; there are individual differences in the way bodies sense due to gender, race and class, and that multisensory perception is complex and nuanced.Footnote 75 The air itself also has material qualities but so do other aspects of weather like rain and snow. Singing in our research is clearly also used to manage the bodily and emotional challenges created by the weather. For example, in 1926 Stephen Graham described how when walking in the rain ‘after five of ten miles one begins to sing’, ensuring one completes the walk ‘in the highest of spirits’ despite being wet through.Footnote 76 In this way, singing is a form of motivation and emotional self-regulation in the context of embodied experiences of exertion and weather.

1.2 Resonations

Resonations can be both vibrations that are physically felt in the body or heard in the environment as well as metaphorical and symbolic. Writing about sonic resonances in the context of environmental history, Twidle and Elaff highlight sound as both a noun and verb; ‘both physical property (a sound) and open-ended process (to sound or sound out, to enquire into or investigate)’.Footnote 77 In terms of a physical property, Michael Benninger writes that ‘for any instrument to produce sound, something must activate the sound (such as plucking a string on a guitar or blowing into a trumpet), something must vibrate (like the guitar string or the reed), and something must resonate (the body of the instrument)’.Footnote 78 This singular act of the body resonated can have a wide-reaching affect. According to George Revill, ‘the physical properties of sound, pitch, rhythm, timbre seem to act on and through the body in ways which require neither explanation nor reflection. This appears to grant music a singular power to play on the emotions, to arouse and subdue, animate and pacify’.Footnote 79 In its most simple terms when singing the body is the instrument and the resonations come from the exhalation of air via the chest and the head. The environment via the air can then be said to physically resonate within the body as well as outside of it or as Michael Stocker states ‘our sense of sound includes the embrace of our body by the environment’.Footnote 80

In this Element we focus on group singing and there has been some recent scholarly research pointing to the particular health benefits of this activity. Although we cannot apply this directly to the past, it is worth considering the ways in which we currently understand these mechanisms to work in relation to both the physical body and the mind. For example, David Camlin, Helena Daffern and Katherine Zeserson have published research on the wellbeing effects of outdoor group singing on participants of three groups. From this they argue that one key element that makes group singing effective is the ‘phenomenon of interpersonal “resonance”’ as the basis of the shared experience, which, they argue ‘explains why it might contribute positively to the experience not just of social bonding, but also the underlying neurobiological mechanism of the experience of “love”’.Footnote 81 They quote Siegle’s explanation for this phenomenon that ‘when we attune to others we allow our own internal state to shift, to come to resonate with the inner world of another. This resonance is at the heart of the important sense of “feeling felt” that emerges in close relationships’.Footnote 82 From this they posit that wellbeing might not just be from the group participation element or the singing itself but rather that the production of musical effects reinforces ‘interpersonal attunement and consequent individual wellbeing, a mutually reinforcing and complex adaptive process’.Footnote 83 As noted this is a contemporary study but there are clearly descriptions of ’fellow feeling’ which are reinforced through group singing within our historic examples and these will be explored more in Section 2.

It is also possible to consider in this context that broader resonances with nature and other species, as well as other people might further reinforce this process, particularly as one of the participants within Camlin et al.’s project stated that ‘somehow it was the mountains that were reverberating with us, if you see what I mean, rather than an audience’.Footnote 84 The experience of the sound here is inclusive of the mountains which are viewed as an active participant. As the researchers note, ‘from the point of view of the participants, the way in which they come to feel a resonant connection with other individuals, with the group as a whole, with the music they are singing and its meaning, and their surroundings, appears to lie at the heart of what they feel is most powerful about the group singing experience’.Footnote 85

In another example, Theorell has described how participants of choral groups self-report increased experience of joy and relaxation from singing together, as well as a sense of connection and cohesion with other choir members.Footnote 86 Other studies measured levels of oxytocin (a hormone thought to have a role in social-bonding) before and after activities and found higher oxytocin levels after group singing compared with simply chatting together. The factors affecting feelings of social and physical wellbeing from singing are complex, and Theorell concluded that the current state of evidence on the health benefits of group singing was modest and often indirect.Footnote 87 Another synthesis by Kang, Scholp and Jiang, citing Pearce et al., indicated it may be the extent to which participants felt integrated within their group, rather than the nature of the activity itself, that engenders perceived benefits.Footnote 88 However, they also cited research by Stewart and Lonsdale that suggested ‘choral activities seemed to enhance the sense of belonging of the participants, co-ordinated within the singing itself to further improve the well-being and quality of life’.Footnote 89 It should be noted that these synthesis articles mainly looked at group singing by formal choirs in indoor contexts. An exception is the Camlin et al. study which explored and compared the experiences of amateur adult group singers in both open-air and indoor settings. They found that ‘while group singing may contribute to individual health and wellbeing, the primary benefit participants across both groups identified is the way that it brings them to a closer, more profound, connection with others’.Footnote 90 As these are contemporary examples they cannot be simply mapped onto the past but they do suggest that a healthful singing body can be achieved within a group in specific ways, which relate to resonances with others whether they are human, animal or part of the wider place or environment.

One aspect that is potentially less relevant for today’s singing groups, although not for all, is the role of the divine as a key element within the environment. The founder of the CHA and HF, T. A. Leonard, began his career as a congregational church pastor before deciding to ‘devote the whole of his energy and ability to the holiday movement’ which highlights how close these connections could be.Footnote 91 The first song in Songs by the Way published by the HF was ‘The Strength of the Hills’ by Mrs Hemans and includes this verse which depicts God within the air and other natural phenomena:

Here God is present within the mountains and forests and is the creator of air via his breath, so singing outdoors would have an added layer of emotional and spiritual resonance beyond that of the physical realm.

1.3 Emotions and Senses of Wellbeing

The interrelationships between singing, emotions and wellbeing have already been touched on in relation to group singing practices. However, the physicality of singing is clearly an important feature when considering senses of wellbeing. For example, as Feld argues there is a ‘special bodily nexus for sensation and emotion’ when sound, hearing and voice are brought together due to ‘their coordination of brain, nervous system, head, ear, chest, muscles, respiration, and breathing’.Footnote 93 In the case of outdoor walking, movement is also brought into play as our groups were often walking and hiking together as well as singing.

In a 1926 chapter on ‘Marching Songs’, Graham reflects on the interplay between rambling and singing:

Yet singing is very natural, and when one takes to the road the singing impulse comes to the bosom. Light-heartedness begets song. We sing as we walk, we walk as we sing, and the kilometers fall behind. After a long spell of the forced habit of not singing one finds oneself accidentally singing, and there is surprise. Good Heavens! I’m singing.Footnote 94

Although the regular beat of a marching song may help maintain pace and rhythm when walking, Arthur Sidgwick in 1912 posited that stronger drivers for the connection of walking and singing were the links to ‘the actual bodily condition of a walker, that perfect harmony which comes of a frame well occupied’ and the emotions engendered through rambling: ‘It is on the mood which walking induces, rather than on the rhythmical character itself, that the affinity between walking and music mainly rests.’Footnote 95

On an SCR rambling trip to Ambleside in 1919 the description of singing of Come to the fair at an evening concert articulates the close association between air, breath and emotions, and highlights the additional meaning of air as describing a melody: ‘a lilting air, breathing the spirit of the week’.Footnote 96 A ‘love of jollity’ was a characteristic of the early SCR: ‘Here boisterous good humour and kindly “divvlement” had free scope, and many a weary business man and toiler has temporarily forgotten his burden of care and gloom in the joyous revelry of our open air life.’Footnote 97

In all of these accounts song is described as forming an important method by which the body moves and the mind responds to the external environment. As has been touched above and will be explored more fully in the next sections, it is also a way to build connections with other people, animals and places.

2 Fellow-Feeling through Song

The object is to encourage the growth of the true open-air spirit of fellowship and love.Footnote 98

This quote from the foreword to the SCR songbook, Songs for Ramblers to Sing on the Moorlands, illustrates how communal singing was framed by early twentieth century open-air groups as a deliberately relational activity. Through collective, open-air singing people developed a sense of connection and fellow-feeling with both one another and with nature. This use of the word fellow-feeling is chosen by us to mean more than the term ‘Fellowship’ as used by the various organisations we are discussing. As Rob Boddice and Mark Smith argue ‘historical concepts of experience often bear little resemblance to “emotion” or “sense”, but rather combine affective and cognitive categories in more general concepts of feeling’.Footnote 99 Fellow-feeling in relation to our historical actors incorporates more than other humans as well as other concepts, such as potential civilising influences for the modern man and woman, something that will be expanded upon later. However, two concepts are worth noting as useful for our framing of understanding fellow-feeling: the historian Barbara Rosenwein’s definition of emotional communities as groups ‘that have their own particular values, modes of feeling, and ways to express those feelings,’ and the anthropologists Victor and Edith Turner’s notion of communitas as ‘inspired fellowship’.Footnote 100 For Rosenwein, emotional communities are not always centred on emotions but ‘share important norms concerning the emotions that they value and deplore and the modes of expressing them’.Footnote 101 Although tricky to pin down to a simple definition, Edith Turner has described communitas as a form of collective joy: ‘a group’s pleasure in sharing common experiences with one’s fellows’ and ‘the sense felt by a plurality of people without boundaries’.Footnote 102 Communitas comes alive in many diverse settings, and the combination of shared activities such as singing, rambling, eating, drinking, learning, and holidaying together amongst outdoor recreation groups in the early twentieth century may have been fertile ground to inspire this.

In this section we interrogate the archival material to explore relationships between open-air singing and a feeling of community and fellowship. In particular, we consider how building fellow-feeling was one aim of early twentieth-century outdoor recreation organisations, and how this aim was enacted through their singing practices. We will explore how the fellowship engendered through open-air singing both opened-up and created limits to who could be part of these communities, and was extended to other-than-human aspects and actors in the landscape.

A desire to develop feelings of co-operation and fellowship amongst their members and a love and enjoyment of the open air were common foundational aims of many early twentieth-century outdoor recreation groups, including our focal groups founded in Northern England: the co-operative holiday movement and the SCR.Footnote 103 The CHA was founded in 1893 by Thomas Arthur Leonard, who also founded its sister organisation, the HF, in 1913. CHA and HF holidays aimed to ‘give scope for the exercise of personality and initiative, but with everyone contributing to a common stock of fellowship and goodwill’ where guests could discover ‘the joys of fellowship in the open air’.Footnote 104 Similarly, the SCR, founded by George Herbert Bridges Ward in 1900, also aimed to foster a spirit of open-air fellowship, as the quote which opened this section indicated. Both Ward and Leonard were prominent figures in the leadership of open-air recreation; for instance, Leonard was the first president of the Ramblers’ Association and Ward played a central role in wider campaigns for public access to the countryside.Footnote 105 Ward drew from a form of secular socialism and the collective struggle for access, whereas Leonard was influenced by his background as a congregational minister alongside the work of socialist thinkers to encourage fostering a belief in ‘world brotherhood’.Footnote 106 However, both held a common ethos that taking part in communal activities and experiences – such as rambling, learning, singing and holidaying together – were ways of building both an individual’s character and the bonds between people.

Singing together was seen as a medium well-suited to foster these bonds. The foreword to the CHA and HF joint songbook Songs of Faith, Nature and Fellowship described communal singing as a ‘wonderfully unifying influence’.Footnote 107 Chorus singing was described in an earlier songbook edited by Henry Walford Davies as ‘the very affirmation of good fellowship’.Footnote 108 A 1915 piece in the CHA magazine Comradeship emphasised the ‘value of song in seasons of stress’ such as wartime, and its power to encourage feelings of connection between people and to change their emotional state: ‘music shares with the open air the power of refreshing and inspiring us, of rekindling enthusiasm and promoting good fellowship’.Footnote 109 Singing also lent language and metaphor to describe fellowship and community, for instance, as within a scouting movement songbook: ‘a crowd of individuals working in harmony’.Footnote 110 Writing of communitas developed through music specifically, Edith Turner noted it as a distinctive form of human experience that goes beyond the individual, physical boundaries of our bodies through connecting through both rhythm, song and even a state of flow:

In music, you join your voices completely, you are joined, you are in the same place, because you have gone altogether into the sound, and the sound is one sound with all the other people in it: one, in the same space.Footnote 111

As noted in Section 1, recent scientific work has suggested that there are complex physical and social reasons underpinning senses of wellbeing and connection through singing. For instance, Camlin et al. described a blurring of the self and other, through group singing as a process of dialogue and negotiation, as one of the attributes of music that studies have indicated enables the development of interpersonal bonds.Footnote 112 For those singing in the open air, these feelings of connection extended to the landscapes in which they sung and recognised the role of the landscape in facilitating these social connections.Footnote 113 There are, of course, differences between these contemporary studies and the early twentieth century outdoor groups we are concerned with. For our outdoor recreation groups, open-air singing was just one part of their activities, and perhaps in a more informal sing-song than a choir-like setting.

In the early twentieth century, the collective singing encouraged by outdoor recreation groups was influenced by and set in the context of a national community singing movement in England, which was framed by some contemporary organisers and commentators as an antidote to post–First World War economic depression, class tensions and industrial unrest.Footnote 114 Large-scale community singing events were held in public spaces and high-profile venues such as the Albert Hall in London, with sponsorship from national newspapers, and numerous songbooks published.Footnote 115 John Goss, writing in the foreword to the Daily Express Community Song Book, described it as ‘an astounding social movement that has since swept over the country like a prairie fire’.Footnote 116 Open-air elements of this movement included singing at football grounds, which

were turned into gigantic open-air concert centres. Twenty, thirty, forty, fifty thousand men and women provided unforgettable spectacles as they stood in wintry sunshine or biting wind to sing sea shanties, old, well-known choruses, and – most memorable of all – ‘God Save the King’.Footnote 117

Therefore, communal singing was a practice many people may have enjoyed outside of these outdoor groups and that was promoted as a means to heal perceived social divisions during the 1920s.Footnote 118 The community singing movement was an inspiration not only for the notion of singing as a way of building togetherness but in terms of the type of songs perceived as most suitable to foster this. Community songbooks tended to include a mixture of patriotic, national, folk and popular songs. As Baden Powell stated in the 1947 introduction to the scouting movement’s Open Air Songbook:

These are the songs with which we began the community singing idea, and I remember hearing a thousand boys sing a dozen or so of them to the King and Queen at a Melba Concert in the Albert Hall in London.Footnote 119

Other songs were chosen by outdoor recreation groups because they were perceived to evoke the spirit and emotions of fellowship when sung together. The foreword of the HF songbook, Songs by the Way, indicated that the selection of folksongs within the book was not made solely on aesthetic grounds but because they had ‘a peculiar character of jollity which renders them particularly suitable for fellowship singing’.Footnote 120 The structure of some songs also reflected a focus on collective singing. For instance, songs were sometimes arranged in parts and some songbooks included rounds and call-and-response songs, which suggested group rather than individual singing. For example, the SCR song ‘Up the Hill O’ (to the tune of the folksong ‘Twanky Dillo’) had verses assigned for male and female voices separately before a final verse for all to sing together.Footnote 121

Within the historical songbooks, there is also a sense that the groups themselves were tapping into existing practices of and enthusiasm for open-air singing amongst their members. The introduction to the HF’s Songs by the Way described how ‘many of the songs have been sung by them on mountain tracks and field paths, until they have become traditional’.Footnote 122 Ward, too, described many songs within the SCR songbook as ‘regularly sung by Sheffield and Manchester Ramblers in the open, on moorland, hill slope or summit’, indicating this was to some extent an existing open-air repertoire and practice amongst communities of ramblers.Footnote 123 The idea of a living repertoire of songs enjoyed by specific groups is epitomised in the introduction to the (Stafford) Mountain Club’s songbook from 1955 (see Figure 4). The editor described only printing on one side of the pages so that more songs may be printed on these blank pages as they ‘become known’, without the need to reprint the full songbook. Members were also encouraged to add songs to these pages individually.Footnote 124 We might also tentatively see the selection of songs within the open-air songbooks as reflecting a specific sub-section of community singing; a community tramping and open-air repertoire.Footnote 125

Figure 4 Cover of The Mountain Club Songbook (1955) featuring a hand-drawn cartoon of a mountaineer in the foreground facing a range of tall mountains.

Figure 4Long description

A songbook cover with a hand (pen) drawn cartoon of a mountaineer in the foreground facing a range of tall, pointed mountains. The mountaineer has a rope slung over their shoulder and an ice axe to their right. The image is black pen on a white background, apart from a small inset oval emblem in the centre, which features a grey pointed mountain with a snow-scapped peak, against a blue background.

The singing practices of these groups were no doubt also influenced by group singing activities amongst the wider movements they were aligned with. Ward advertised the first SCR club ramble, which took place on 2 September 1900, in the pages of the Clarion newspaper. The Clarion itself published songbooks of appropriate songs for ‘socialist organisations across the Kingdom’.Footnote 126 A recent exhibition at the John Rylands Library in Manchester described communal singing at meetings as ‘an integral part of Clarion Life’.Footnote 127 The co-operative movement also published a range of songbooks, beyond those specifically for use on holidays.Footnote 128

Many open-air recreation groups had an explicit aim of improvement for their members, underpinned by ideas of the value of the educational and rational use of leisure time for the betterment of both the individual and society. Even in some of Ward’s lyrics to SCR songs this idea is foregrounded:

This civilising ideal was often set in the context of a perceived contrast between urban leisure and life (often depicted as unhealthy, senseless and sometimes immoral) with the healthy and enriching experience of countryside leisure: a contrast we explore more fully in the next section. These improvement aims were translated into practices and publications which aimed to influence their members thinking and behaviour, shaping a kind of open-air citizenship. For Ward, one of the purposes of rambling clubs, such as the SCR, was as a form of training in the ethos of rambling (and by implication the club itself) through the passing on of knowledge and skills from older and more experienced ramblers who ‘guide their younger brethren on the way … in developing true personality and desire for Access with responsibility.’Footnote 130 Such groups were essential in Ward’s view so that urban-folk could ‘re-learn how to play’ and ‘intelligently ramble, and not aimlessly ”hike”’.Footnote 131 Each year, the SCR published a handbook that listed the scheduled rambles for that year accompanied by suggested readings, poems or songs. The handbooks also included a series of topical essays (often written by Ward himself) and updates on the activities of various other outdoor focused organisations such as the Council for the Preservation of Rural England and the Commons, Open Spaces and Footpaths Preservation Society. Alongside this, it was expected that every SCR ramble would include a song and reading in the open-air or at a refreshment stop. The open-air educational aspect of the CHA included talks and sermons during walks, which were the core element of CHA holidays. For example, a 1938 summer holiday programme book from the CHA details walking excursions of between eight and fourteen miles for each weekday of the holiday (with an optional walk on Wednesday).Footnote 132 The CHA magazine (Comradeship) included informative articles as well as association updates, and their holiday programmes included lists of recommended reading (including songbooks). In the introduction to The Fellowship Songbook, the links between singing, improvement and fellow-feeling are made clear:

We have been vaguely aware of our great heritage of song, but have not fully realised how truly educative and ennobling that heritage is, nor how its common enjoyment can knit us together in bonds of fellowship.Footnote 133

As singing was part of this improving offer, the choice of songs, and the way they should be sung, played a role in shaping the right kind of open-air fellow or citizen. For some groups this meant that many popular songs of the time were not considered to be appropriate, illustrated by the following quote from the scouting movement: ‘Music-hall songs are not camp-fire items. The “sentimental song” is never suggested as a solo; cheap stuff from the Student’s Songbook dies out of popularity.’Footnote 134 Ultimately, song choice was not to be left up to the scouts or guides themselves as ‘they have not been educated up to a good standard of taste’ but should be chosen by the Leader as a way of shaping their taste in what was deemed to be an acceptable direction.Footnote 135 Similarly, the author of a 1915 article in Comradeship wished that ‘more wisdom was exercised in the choice of songs by amateur singers’, who opted for popular songs that were considered to have less ‘artistic value’.Footnote 136 The SCR songbook is less prescriptive in the type of songs to be sung (although Ward described English folksongs as being particularly appropriate), but we can see the publication of songbooks, and the editorial decisions about what to include and exclude, as shaping the repertoires of these groups.Footnote 137

Therefore, whilst the act of singing was framed as a way of developing community spirit and fellow-feeling generally, the choice of what (and how) to sing was a way of shaping individual behaviours and attitudes in line with the expected cultural norms within groups. This was also informed by aspirational ideas about wider open-air citizenship, and appropriate ways of being in the countryside, which we explore in Section 3.

2.1 Group Singing and Identities

The songbooks published by open-air recreation groups provided a community resource, a shared repertoire of songs, but it is through the act of collective singing itself that these contributed to fellow-feeling and group identity. In an oral history project, led by the Moors for the Future Partnership and the Peak District National Park Authority in 2012, Linda Crawley recalled singing as an integral part of the culture and practice of the Woodcraft Folk in the 1960s.Footnote 138 She compared this to a sense of being part of a singing family: ‘we all sang, we sang on the moors, we sang on the bus, we sang when we were having our lunch, we were like the von Trapp family singers sometimes’.Footnote 139 As a living tradition, songs were not just learned through songbooks but from others as a form of both peer and inter-generational learning:

a lot of the time from the adults who’d grown up through the Woodcraft Folk, taught us the songs when we went to camps and things … and we always had music nights so we learned from each other and from the adults. So there was a history. And we had our songbooks.Footnote 140

In a 1915 article for Comradeship, Henry Walford Davies described how songbooks themselves could facilitate these connections between people not just in the present but across time and generations:

A song book is a human, not a musical document. Through its pages a lonely soul can converse with its kind; comrades can find fellowship; a present and harassed generation can exchange confidences with an age that is past, and find a steadying influence in an expression of feeling which is both free and orderly, both full of fantasy and full of method, at once whimsical and logical, refreshing the mind and the imagination of both the singer and his hearers.Footnote 141

Here, the songbooks are framed as a way of accessing fellow-feeling at distance, away from the companionship and settings in which communal open-air singing took place. Singing these songs was an act of remembering others, reconnecting with memories of shared experiences, and also perhaps an expression of longing and nostalgia for the ideal of a comforting past. Writing in 1926, Stephen Graham reflects on the interplay between song, memory, emotions and identity, and how these are brought to the fore through rambling and singing together in the countryside:

I’m singing. And singing what? Not the latest song, by any means, but something remembered from childhood and school days, the happy innocent strains of days gone by. Songs give birth to songs, memories to memories.Footnote 142

Many of the founding members of the SCR were part of the Clarion Vocal Choir’s Saturday rambling group and, therefore, were likely to have sung together already.Footnote 143 Indeed, singing was depicted as something to be celebrated and rewarded – one of Ward’s ‘hints’ for ramblers in the club’s 1919–20 handbook suggested that ‘should the Leader sing a jolly song, the party have permission to treat him to his tea’.Footnote 144 Group singing (and their shared repertoire) were also a way of identifying with the club. In an account of a ramble in 1921, a club member described the arrival of their founder, G.H.B Ward, announced through singing one of their club songs:

Half way up the side of Bretton Clough we stopped for a breather, and were for a moment astonished at hearing the ‘Land of Moor and Heather’ being sung ‘loud and clear’ apparently from the clouds. Looking up, on a projecting cliff, and like an eagle in his eyrie, stood a form outlined against the blue sky, rucksack on back, and voice uplifted in melody.Footnote 145

This was followed by a call and response of songs, with the resting ramblers singing one of the club songs back to Ward, who responded with a solo rendition of another club song (‘A Jovial Tramp am I’). In this way, the songs provided an intra-community means of communicating connection in the landscape. On the same ramble after lunch the group sang more of their shared repertoire, outside the Barrel Inn at Bretton, ‘to the evident amazement and, let us hope, pleasure of a few strangers who had halted for a modest refresher’.Footnote 146 It is clear from these descriptions that group singing was a well-rehearsed practice and a way of expressing their sense of togetherness when out rambling, in contrast with the ‘strangers’ they encountered in the countryside.

Another way that singing connected with group identity was through the circulation of new lyrics to existing tunes, which celebrated the exploits and characters of members of the SCR. For example, ‘A Toasting Song’, sung to the tune of the traditional song John Peel, included the following lines about the club’s founder:

D’ye ken Bert Ward, when he’s out for the day,

With boots like tanks and his mop of hair astray?Footnote 147

Another song, ‘The Sheepskin and the Jumper’, gently pokes fun at the rambling attire of two club members: ‘Whiteley’s old grey jumper’ and ‘Diver’s sheepskin jacket’.Footnote 148 Re-versioning songs was not a practice limited to the SCR; it also seems to have been common practice amongst members of various twentieth century climbing clubs. For example, the Manchester Rucksack Club’s The Songs of the Mountaineers, published in 1922, included over forty club songs, which the editor, John Hirst, placed in a separated section: ‘As a concession to readers on the fringe of our circle who may be a little aghast at our familiarities’.Footnote 149 However, it was not a practice shared or condoned across all open-air recreation groups. The scouting movement advised against re-writes arguing this ‘spoils the tune forever; and the result is not any more fun to sing than real amusing songs and choruses’.Footnote 150

Singing was also a way of cementing shared bonds of fellowship and identification within groups beyond their open-air activities and holidays. Group singing was part of CHA conference and reunion events, and the SCR sang together at their club dinners.Footnote 151 As T. Henderson noted in the pages of Comradeship in 1914, music itself was part of the fellowship of CHA holidays ‘we make new friends not only of men and women, but of books and music’.Footnote 152

2.2 Boundaries and Limits

Another common thread across the SCR and CHA was that the communal activities and notions of fellowship were open to men and women together – an ethos that was not universal across outdoor recreation organisations at this time. The scouting movement had separate groups for girls (rosebuds/brownies and guides) and boys (cubs and scouts), and many climbing clubs did not accept female members until later in the twentieth century. For instance, the Manchester based Rucksack Club only admitted women members from 1990.Footnote 153 Indeed, one of the distinctive characteristics of CHA and HF holidays was a notion of equal fellowship across gender and social standing, informed by a belief that ‘irrespective of class, education or worldly possessions, the deepest joys are to be found in human friendship and fellowship’.Footnote 154 As Leonard wrote to CHA members in 1910:

One of the best things that our movement offers is the possibility of frank and open friendships between men and women. On the tramp, and in the intercourse of the centre, there are the fullest opportunities for both to contribute to and share in the spiritual and intellectual life of the fellowship.Footnote 155

The annual handbooks of the SCR indicated that women were involved (albeit to a much lesser extent than men) in the running of the club and leading some of the club’s scheduled rambles in the early twentieth century. Furthermore, the exploits and characters of female members of the club were celebrated in the lyrics of some songs in their songbook:

Hilda, she’s a sturdy lass; Mrs Bingley is as well;

It’s a treat to see them going, over moor and fell.Footnote 156

However, there were still activities that were off-limits to women members. Women were asked not to take part in some of the club’s hardiest outings, including some Midnight Rambles and winter Revellers Rambles, and it was not until 1955 that the first formal women’s Revellers Ramble took place.Footnote 157

Whilst not mentioning singing specifically, the historian Melanie Tebbutt has suggested that the incorporation of poetry and literature within Ward’s ethos for the SCR spoke to a ‘need for emotional release more usually constrained by the conventions and expectations of contemporary manliness’ and an alternative, more complex, expression of masculinity.Footnote 158 Whilst rambling on the rugged hills and bleak moorlands of the Peak District was associated with more traditional ideas of masculinity, for Ward this was tempered by a very different manly expression of feeling through song and brotherly companionship with his fellow (male) ramblers, informed by Romanticism and the socialist writing of his friend Edward Carpenter. This combination of nature, song and manly companionship could be powerfully moving, as this extract from the 1916–17 SCR handbook, cited by Dave Sissons, Terry Howard and Roly Smith, illustrates. It was written by club member Harry Inman about walking with G. H. B Ward:

We sang – he and I. Yes, you stay-at-home heathens. I repeat – we sang. His deep resonant voice betraying his emotions. He revelled, he jumped, he shouted and danced to his heart’s content; then he did what only a nature-loving man can do. He wept. Great tears welled into his eyes as his arms went around my neck.Footnote 159

When writing about fellow-feeling, publications from both the CHA and SCR refer to this in masculine terms. For example, in a piece about ‘our coming of age ramble’, the author (The Wee Mon) described ‘the same old Clarionese spirit of brotherliness’.Footnote 160 Similarly, in an article from Comradeship, T. A. Leonard described the CHA and HF as providing ‘simple fraternal holidays’.Footnote 161 Whilst these possibly reflect writing styles of the time (where the masculine was taken to represent all people), there are further pieces that explore the expression of ideas of ‘manly’ and ‘gentlemanly’ ways of being in the context of behaviour in the countryside and at holiday centres. We will come back to this theme in Section 3.

Just as the wider activities of groups like the SCR sometimes reflected inequalities in the reach of fellow-feeling along lines of gender, their open-air singing practices and associated publications reflected a fellowship that was perhaps not universally welcoming. The selection of songs across the historical songbooks, for instance, suggests possibilities for both inclusion and exclusion. The CHA and HF songbooks included sections of hymns which may have been unfamiliar to those who weren’t of Christian faith. As already noted, the SCR songbook included many rewritten songs, referencing the exploits of members of the club itself. One can imagine these may have been experienced as cliquey and less than welcoming by new members. Some iterations of songbooks from the co-operative holiday movement included songs made popular through blackface minstrelsy. Although popular with some audiences at the time, we now understand these as perpetuating harmful stereotypes of blackness and they must be considered in the broader context of complex histories of the othering and marginalisation of people from global majority backgrounds within rural landscapes and outdoor recreation.Footnote 162

There is also some evidence that songbooks (and the songs within them) were employed to promote aspirations for fellow-feeling beyond the groups they originally served. In contrast to the perhaps inward-looking and national focus of the community singing movement, some aspects of the singing practices of outdoor recreation groups served to extend fellow-feeling beyond national borders. CHA songbooks were requested (and in some cases supplied free-of-charge) by soldiers in military camps during the First World War.Footnote 163 Even earlier, a 1912 issue of the CHA magazine Comradeship described how ‘demand for our songbook increases yearly’ and copies had been sent to a missionary-led School in Africa: ‘thus the circle of our influence widens’.Footnote 164 In addition, song selection sometimes indicated international connections. Another outdoor recreation holiday organisation, International Tramping Tours, which T.A. Leonard was involved in forming in the 1930s, included numerous songs from other nations in their songbook, sometimes in languages other than English so that there was ‘no excuse for not joining in when our friends abroad are singing’.Footnote 165 Whilst the SCR songbook did not include songs from other countries, articles within their handbook suggested they welcomed, and celebrated, ‘foreign’ members in a spirit of ‘international brotherhood’, including visitors from Egypt, India and Germany.Footnote 166

2.3 Fellow-feeling with Nature

In the foreword to the SCR songbook, Ward described one purpose of the book as ‘the emulation of the birds who give praise to Nature by their full-throated, joyous song’.Footnote 167 This evoked a form of fellow-feeling with nature: with other-than-human actors and dimensions of the countryside. A similar comparison was made in the introduction to a scouting songbook: ‘Nature expresses itself in music and song. Scouts can follow Nature’s example.’Footnote 168 Both of these examples also emphasise how this fellow-feeling was brokered through an emotional connection and the expression of these emotions through song. Through singing people actively responded to and contributed to emotional, imaginative and sensory encounters with the other-than-human. As the historian Michael Guida has highlighted:

the natural world could itself provoke the rambler into making their own sounds, to complement walking rhythms or to celebrate a sense of freedom, and this contribution to the soundscape should be considered as part of a wide-ranging sensory interplay of body and mind with outdoor surroundings.Footnote 169

There was a sense that, if done in the right way and choosing the right songs, open-air singing complemented and was in harmony with the natural elements of these soundscapes. The example that opened this Element – describing evening singing around a campfire on a CHA holiday – illustrated this with the human voices portrayed as ‘fitting delightfully’ with ‘the whisper of the wind and the beck’s bright flowing chatter’.Footnote 170

The other-than-human is also represented in some of the lyrics of songs included in open-air songbooks. For instance, ‘The Clarion Ramblers’ Marching Song’ (with new words by H. H. Diver set to the tune of ‘When Johnny Comes Marching Home’) places the ramblers in northern moors, with attention to many natural aspects of this rural setting, including sounds. The song mentions heather, ‘mountain sheep’, grouse, cotton grass, rivers, and ‘where raging torrents roar’ and ‘where the birds’ sweet music trills’, and described how

Far away from the city crowd,

Alone with Nature we shout aloud.Footnote 171

There are less bespoke songs in Songs by the Way, but the selection of religious and folk songs often include references to rural and countryside environments, and in some cases, the sense of harmony between human and natural society. For instance, ‘In Derry Vale’, references ‘the singing river’ in the opening line, and ‘The Hunt is Up’ describes the response of nature to the sound of the hunting horns:

All of these give the sense of open-air singing as part of mingled rural soundscapes, although these examples indicate perceptions of the countryside as a largely unpopulated space for nature – (something we explore further in Section 3.1). The notion of singing as a point of connection between human and the other-than-human perhaps also connects with older traditions of singing amongst agricultural workers, as described by folklorist Steve Roud, which included milkmaids singing to cows to calm them and encourage milk yield and the chanting of bird-scaring rhymes.Footnote 173

Along with fellow-feeling amongst the men and women who were members of outdoor recreation groups, and building a feeling of connection with nature generally, there were elements of fellowship through open-air singing which were specifically rooted in the rural landscapes that these groups knew and loved. It is these connections with place that we explore in the next section.

3 Relating to Place

Sing them upon the sunny hills

When the days are long and bright.Footnote 174