Introduction

Modern states’ governments typically seek to avoid being blamed for contested policies. This blame avoidance imperative applies to democratic as well as authoritarian, to progressive as well as conservative, to communitarian as well as cosmopolitan governments. While almost all governments seek to avoid blame most of the time, their opportunities to avoid blame for contested policies vary substantively. The growing literature on blame avoidance highlights that delegation of governance tasks to third parties improves governments’ blame avoidance opportunities (see, e.g., Bach & Wegrich, Reference Bach and Wegrich2019; Hinterleitner, Reference Hinterleitner2020; Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2017; Hood, Reference Hood2011; Mortensen, Reference Mortensen2016). International organizations (IOs), including the European Union (EU), are considered particularly helpful in this regard (see, e.g., Daugbjerg & Swinbank, Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2007; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Lake, Nielson, Tierney, Nielson, Hawkins, Lake and Tierney2006; Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2014; Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik1994; Pollack, Reference Pollack1997; Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2020; Tallberg, Reference Tallberg2002; Thatcher & Sweet, Reference Thatcher and Sweet2002).

In the literature, delegation is assumed to help governments to avoid blame in two ways. A first strand in the blame avoidance literature highlights the blame shifting effect of delegating governance tasks to third parties. It underlines that through delegation, governments can distance themselves from the contested policies while agents catch public attention. Moreover, governments can deny their own and underscore their agents’ responsibility, thereby shifting the blame onto the latter. As agents of delegation, third parties, such as the EU, serve governments as convenient lightning rods and scapegoats.Footnote 1 A second strand in the blame avoidance literature hints at the blame obfuscation effect of delegation. This literature claims that the delegation of tasks to third parties allows governments to circumvent public scrutiny. Through delegation, governments make the attribution of responsibility more complex, thereby obfuscating blame. Moreover, by delegating governance tasks to third parties that are not equally subject to public scrutiny, contested policies are less likely to become politicized and, consequently, governments are less likely to become the target of public blame attributions. The policies that are made and/or implemented by third parties, such as the EU, will simply attract less public attention than the policies of governments.Footnote 2

While we agree that delegation has these effects and can thus help governments to avoid blame through blame shifting and/or blame obfuscation, we seek to address two gaps in this literature. First, we find that there is surprisingly little research on whether delegation does in fact come with these blame avoidance effects. The bulk of the literature simply assumes, without empirical assessment, that delegation yields blame shifting and/or blame obfuscation effects. Second, the literature assumes that delegation has these blame avoidance effects regardless of its specific design. In this view, the delegation of governance tasks to the supranational European Central Bank (ECB) generates the same (or at least similar) blame avoidance effects as delegation to the largely intergovernmental European Stability Mechanism (ESM). The literature thus does not discuss whether different delegation designs come with different blame avoidance effects.

To fill these gaps, we study the effect of different delegation designs in the EU on public blame attributions to governments. Which delegation designs come with a blame obfuscation effect and which ones have a blame shifting effect? We argue, first, that delegation to independent agents, such as supranational EU bodies, has stronger blame shifting effects than delegation to dependent bodies, such as intergovernmental EU actors. We claim, second, that delegation to external agents, such as foreign governments, comes with stronger blame obfuscation effects than delegation to internal EU actors, such as the Commission.

The ambition of this paper is to develop the argument that different delegation designs come with different blame avoidance effects theoretically and probe its empirical plausibility. Drawing on the blame avoidance literature, we first elaborate our argument about the blame avoidance effects of different delegation designs. We then assess our theory by employing qualitative content analysis of public blame attributions about two contested EU policies in the financial crisis and the migration crisis. The case studies lend plausibility to our theoretical expectation that a gradual move from dependent (intergovernmental) EU actors to more independent (supranational) EU agents yields blame shifting effects while a move from internal EU agents to external, non-EU agents comes with blame obfuscation effects. The paper concludes by discussing the broader implications of our findings about governments’ institutional design choices and the necessity of compensatory accountability mechanisms.

Theory: Modes of delegation and their blame avoidance effects

Blame avoidance is ubiquitous: almost all the time, governments seek to avoid blame for contested policies (Hinterleitner, Reference Hinterleitner2020; Weaver, Reference Weaver2018). The blame avoidance literature generally assumes that one way by which governments may avoid blame is to delegate governance tasks to third parties. Giving third parties policy-making or policy-implementation tasks allows governments to reduce the blame that is publicly attributed to them in cases in which the respective policies are publicly contested. While we agree with this assumption, we also highlight that this blame avoidance effect of delegation is independent of whether governments delegate for reasons of blame avoidance (see, e.g., Daugbjerg & Swinbank, Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2007; Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2017; Hood, Reference Hood2011; Landwehr & Böhm, Reference Landwehr and Böhm2011) or whether they delegate for reasons that are unrelated to blame avoidance. In either case, we expect delegation to matter for blame avoidance outcomes. This is because delegation increases governments’ opportunities to pursue (presentational) blame avoidance strategies while, at the same time, constraining the opportunities of other actors, such as the opposition, to attribute blame to the government (see, e.g., Heinkelmann-Wild & Zangl, Reference Heinkelmann-Wild and Zangl2020a; Heinkelmann-Wild et al., Reference Heinkelmann-Wild, Kriegmair and Rittberger2020; Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2015; Hood, Reference Hood2011; Weaver, Reference Weaver1986).Footnote 3 In line with the literature, we distinguish two blame avoidance effects of delegation:

-

• Blame obfuscation effect: A blame obfuscation effect implies that a contested policy is not politicized. As a result of delegation, it does not provoke frequent public blame attributions.Footnote 4

-

• Blame shifting effect: A blame shifting effect implies that when blame arises in the course of the politicization of a contested policy, it is not attributed to the government. As a result of delegation, blame attributions target other actors.

Going beyond the literature, we argue that different delegation designs yield different blame avoidance effects. In other words, the blame publicly attributed to governments depends on the particular delegation design, that is, the way in which governments relate to the agents they draw on to govern targets. Some delegation designs are more conducive to governments’ blame avoidance than others; and, some delegation designs have a stronger blame shifting effect, while others have a stronger blame obfuscation effect. Drawing on Abbott et al. (Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2020), we argue that two distinctions of delegation designs are of particular relevance for the blame that is publicly attributed to governments:

(1) Dependent versus independent agent: We claim that delegation to independent agents has stronger blame shifting effects than delegation to dependent agents. As opposed to agents depending on government support, independent intermediaries are not controlled by the government (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2020 p. 4). They bear institutional responsibility for their policies and thus become focal in the general public, attracting public attention once their policies are contested. Therefore, delegation to independent actors, such as central banks or regulatory agencies, has a stronger blame shifting effect than, for instance, delegation to state bureaucracies under government control (Heinkelmann-Wild & Mehrl, Reference Heinkelmann-Wild and Mehrl2021; Heinkelmann-Wild & Zangl, Reference Heinkelmann-Wild and Zangl2020a; Kruck, Reference Kruck2014; Rittberger et al., Reference Rittberger, Schwarzenbeck and Zangl2017; Schwarzenbeck, Reference Schwarzenbeck2017). When governance tasks have been delegated to independent agents, the government can publicly deny its own responsibility for the contested policy or even attribute blame to the independent agent with some plausibility. Moreover, once governance tasks have been delegated to an independent agent, critical actors, such as the opposition, will find it difficult to publicly blame the government for the respective policies with sufficient plausibility. Due to the agent’s independence, it will be difficult to convince the general public to blame the government for a policy an independent agent is actually responsible for. To be sure, the general public is often not well informed about delegation designs in general and the independence of governments’ agents more specifically, thus providing governments (and also opposition parties) some leeway to misrepresent responsibilities and make blame attributions that lack plausibility (cf. Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2014, p. 45; León et al., Reference León, Jurado and Garmendia Madariaga2018, p. 661; Wilson & Hobolt, Reference Wilson and Hobolt2015). Yet, when policies are publicly contested, information about the delegation design – and thus institutional responsibilities – will be disseminated. A process of information updating will set in, preventing actors, including government and opposition, from overtly misrepresenting the institutional responsibilities inscribed in the respective delegation design. They anticipate that misrepresenting institutional responsibilities will undermine their public reputation as trustworthy actors (see Heinkelmann-Wild & Zangl, Reference Heinkelmann-Wild and Zangl2020a, Reference Heinkelmann-Wild and Zangl2020b; Kunda, Reference Kunda1990, p. 482−483; Schwarzenbeck, Reference Schwarzenbeck2017, p. 49−51). Overall, if governance tasks are delegated to an independent agent, blame attributions not only by the government, but – due to plausibility concerns also by the opposition as well as the public at large – will be geared towards the agent rather than the government. Assuming that the (in-)dependence of agents of delegation is a matter of degree, we expect the following:

H1: The more independent (dependent) of government control an agent of delegation is, the lower (higher) the share of public blame attributions targeting the government (blame shifting effect).

(2) External versus internal agent: We suggest that delegation to external actors yields a stronger blame obfuscation effect than delegation to internal actors. Internal actors are public entities created by governments. External actors, by contrast, are merely enlisted by governments for governance purposes and can be either private actors or foreign public entities. Therefore, delegation of governance tasks to private entities, such as credit rating agencies, comes with stronger blame obfuscation effects than the delegation to public bureaucracies. Being external to the government, the former are much less subject to public scrutiny than the latter. After all, actors such as opposition parties, critical journalists or civil society pay much more attention to their own government and its internal entities than to the affairs of private actors or foreign governments (de Wilde, Reference de Wilde2019; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Schaper, De Lange and Van Der Brug2018). Thus, when governance tasks are delegated to external agents, governments are better shielded from public scrutiny. The public pays less attention to the contested policies of external actors compared to the ones of actors internal to the government. While delegation to private actors shifts governance tasks to the private realm, delegation to foreign entities shifts governance tasks to the foreign realm. In either case, the said policy is removed from public attention and public blame attributions will generally be less frequent. This also impedes public information updating on the delegation design and thus on a government’s actual responsibility. Moreover, information updating is also often blocked because requirements of information disclosure are typically lower when governments delegate to private or foreign actors than when they delegate to their own public entities. Assuming that it is a matter of degree whether an agent of delegation is internal or external to the government apparatus, we expect the following:

H2: The more external (internal) to the government an agent of delegation is, the less (more) frequent overall public blame attributions for a contested policy will be (blame obfuscation effect).

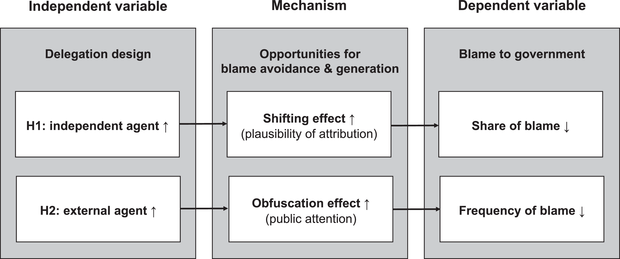

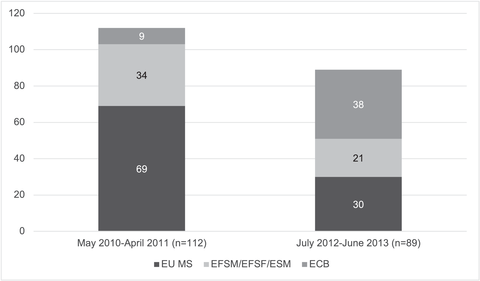

Figure 1 summarizes our theoretical argument. Different delegation designs (independent variable) affect the opportunities for the protagonists of a blame game, including governments and opposition parties, to avoid or generate blame. They shape the plausibility of blame attributions these actors are able to make and the public attention under which these actors operate. Thereby delegation designs define the blame shifting and blame obfuscating effects of delegation, which in turn define the blame the government must incur, and thus the frequency and share of the blame attributions targeting the government (dependent variable).

Figure 1. The effect of delegation design on blame to governments.

Research design

To probe the plausibility of our two hypotheses on the blame shifting effect and the blame obfuscation effect of delegation, we study public blame attributions in the EU. We opted for the EU because in its context member state governments frequently delegate governance tasks to a variety of agents – independent and dependent, external and internal. We study blame for the contested bailout policies in the context of the sovereign debt crisis and the contested border control policies in the context of the migration crisis. In both instances, EU member state governments moved from one delegation design to another, thus allowing us to engage in pairwise comparisons that follow the logic of a most-similar-case-design (Przeworski & Teune, Reference Przeworski and Teune1982, p. 32–33):

• The financial bailout case-pair allows us to assess the suggested blame shifting effect as the delegation design shifted gradually from intergovernmental bodies that were fully controlled by member state governments towards delegation to more independent, supranational EU actors. EU member states initially delegated the task to bail out highly indebted Eurozone member states to predominantly intergovernmental institutions, such as the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM) and the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), later replaced by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) (Gocaj & Meunier, Reference Gocaj and Meunier2013).Footnote 5 From May 2010 onwards, they thus created an ‘intergovernmental, risk-pooling stop-gap’ (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2018, p. 189). With the introduction of its Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program in 2012 (replacing its Securities Markets Programme), the delegation design of the EU’s crisis governance emphasis shifted towards an independent, supranational actor, namely the ECB acting as a lender of last resort. With the implicit, if not explicit, consent from EU member states, the ECB acted upon Mario Draghi’s announcement from July 2012 that the Bank would do ‘whatever it takes’ to save the common currency (Eichengreen, Reference Eichengreen2012; Lombardi & Moschella, Reference Lombardi and Moschella2016; Schelkle, Reference Schelkle, Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2014). Hence, member states ‘used and abused the ECB as a “policy maker of last resort”’ (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2016, p. 54). Due to the respective shift in delegation design, the comparison of the post-May 2010 period with the post-July 2012 period allows us to assess the blame shifting effect. In line with our theory, we expect the change of delegation design to bring about a shift of public blame attributions over time, away from member states and towards the EU.

• The border control case-pair allows us to assess the suggested blame obfuscation effect as the delegation design shifted gradually from an internal body that was created by EU member state governments towards an external actor, namely the so-called ‘Libyan coast guard’. In their approach to control the EU’s maritime borders, EU member states initially relied on Frontex, an EU agency, which was established by a Council Regulation in 2007. Frontex was given the task to support governments in addressing the migration crisis in the Mediterranean Sea through Operation Triton in November 2014, which was replaced by Operation Themis in February 2018 (Servent, Reference Ripoll Servent2018; Scipioni, Reference Scipioni2018).Footnote 6 With the termination of these operations, EU member states started to rely on Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA) as an external agent in the course of 2017. To reduce the number of refugees crossing the Mediterranean, the EU supported the GNA’s coast guards with money, equipment and training (Müller & Slominski, Reference Müller and Slominski2020: 9−13). Following the Malta Declaration of February 2017 (Council of the EU, 2017), EU member states strongly supported the GNA to set up its own search and rescue (SAR) missions. Thus, from August 2017 on, the ‘Libyan coast guard’ effectively replaced the EU’s Frontex mission (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2018: 190; Lavenex, Reference Lavenex2018, p. 1205−1207; Müller & Slominski, Reference Müller and Slominski2020; Niemann & Zaun, Reference Niemann and Zaun2018, p. 13).Footnote 7 Due to this shift in delegation design, the comparison of the post-November 2014 period with the post-February 2017 period helps us to probe the blame obfuscation effect. In line with our theory, we expect the change of delegation design to lead, over time, to a reduction of public blame attributions.

Our case selection follows the logic of a most-similar-case-design, which helps us to probe the plausibility of our hypotheses. The pairwise comparisons allow us to isolate the effect of our independent variable (delegation design) on our dependent variable (blame publicly attributed to governments) while controlling for possible confounding variables, such as policy field and actor involvement. Although the comparison over time within the two case-pairs maximizes the similarity within each case-pair, it cannot account for potential time-dependent effects. Most importantly, it cannot account for the decreasing problem pressure over time which we observe in both of our pairwise comparisons. We thus face a trade-off: finding equally similar case-pairs with similar problem pressure would have been impossible. In the conclusion, we discuss in how far time-dependent effects might have distorted our results.

To measure blame, we study public responsibility attributions (PRA) for contested policies (see, e.g., Bach & Wegrich, Reference Bach and Wegrich2019; Gerhards et al., Reference Gerhards, Offerhaus, Roose, Marcinkowski and Pfetsch2009; Rittberger et al., Reference Rittberger, Schwarzenbeck and Zangl2017; Roose et al., Reference Roose, Sommer and Kousis2020). PRA meet the following three criteria: (1) there is a PRA sender, that is, an individual or corporate actor that attributes responsibility; (2) there is a PRA object, that is, a contested policy; (3) and there is a PRA target, that is, a clearly named actor to whom responsibility is publicly attributed. To identify PRA, we study the media coverage of the selected cases. We focus on media coverage, instead of public opinion polls, because we understand ‘the public’ as a sphere rather than an actor or a set of actors. According to this understanding, governments are not held responsible by the public, but by a number of actors that attribute responsibility in the public (see de Wilde & Rauh, Reference de Wilde and Rauh2019; Habermas, Reference Habermas2008; Risse, Reference Risse2015). To study media coverage, we focus on the quality press which still has a lead media function in European countries and is generally considered to be a good proxy for the public sphere (Brüggemann et al., Reference Brüggemann, Hepp, Königslöw and Wessler2009; Dolezal et al., Reference Dolezal, Grande, Hutter, Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016, p. 45; Koopmans & Statham, Reference Koopmans and Statham2010; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Hutter and Wuest2012; Risse, Reference Risse2015). This allows us to assess PRA made by a variety of actors ranging from government to opposition, from public officials to private companies, civil society actors, scientific experts or journalists.

We focus on two quality newspapers in Germany (Süddeutsche Zeitung; Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung), in France (Le Monde; Le Figaro) and in Austria (Die Presse; Der Standard) as well as one additional quality newspaper with a pan-European reach (The Guardian). While perhaps not fully representative for the European public as a whole, the three countries differ in important dimensions: two countries are big, one is small; two are fiscally conservative, one fiscally more permissive; two are traditionally more migration-sceptical, one more migration friendly; and one country had a right-leaning, one a left-leaning and one a centrist government. To be sure, we would have preferred to also study PRA in newspapers from EU member states that were hit the most by the crises in our case-pairs, especially Italy or Greece. This was impossible not only due to the coders’ lack of language proficiency, but also lacking online newspaper archives. In the conclusion, we discuss this limitation as well as differences between the analyzed countries.

For each case-pair, we searched for PRA statements in the media coverage in the 12-month period after each of the relevant acts of delegation. To single out relevant articles, we conducted keyword searches in the Factiva news database (Dow Jones, 2021). To allow for a comparison, we used within each case-pair the same search string.Footnote 8 We coded all PRA statements directed at either EU member states or their agents.Footnote 9 In our final sample of 348 articles, we identified 424 PRA statements, 201 in the financial bailout case-pair and 223 in the border control case-pair.

To assess the blame shifting effect and the blame obfuscation effect, we draw on two indicators:

-

• To assess the degree to which blame is obfuscated, we study the frequency of PRA statements. Within the two case-pairs we compare the frequency of PRA statements across time periods. This allows us to evaluate whether, over time, the incidence of PRA statements remains on a similar level or is lowered, which would be a sign of blame obfuscation.Footnote 10

-

• To assess the degree to which blame is shifted, we study the targets of PRA statements. Within the two case-pairs, we compare the share of PRA statements that target EU member state governments across time periods. This allows us to evaluate whether, over time, PRA statements target EU member state governments to a similar degree or shift towards their agents.

The EU’s financial bailout policy in the sovereign debt crisis

The EU’s management of the sovereign debt crisis marks an episode of heightened politicization and public contestation (Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Hutter and Kriesi2020; Grande & Kriesi, Reference Grande and Kriesi2015). Consequently, blame games were the order of the day (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2015; Roose et al., Reference Roose, Sommer, Scholl, Kousis, Kanellopoulos, Loukaksis, Barisione and Michailidou2017; Sommer et al., Reference Sommer, Roose, Scholl, Papanikolopoulos, Krieger, Neumärker and Panke2016). As we will show, the blame publicly attributed to EU member state governments changed when the emphasis of their attempt to manage the sovereign debt crisis moved from delegation to dependent, intergovernmental EU actors to delegation to an independent, supranational agent. Comparing PRA during the 12-months period following the delegation to the intergovernmental safety funds – EFSM and EFSF – in May 2010, with the 12-months period following the introduction of the ECB’s OMT program in July 2012 offers support for the blame shifting effect.

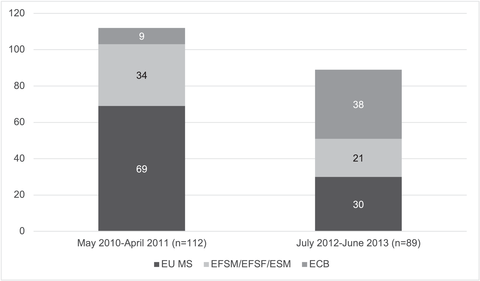

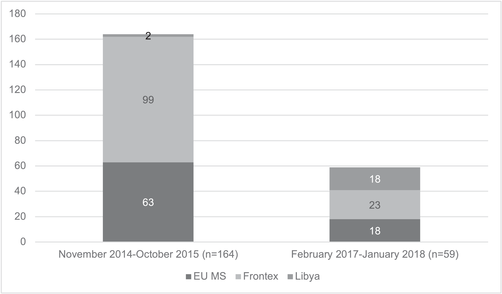

As Figure 2 highlights, PRA frequencies and shares are in line with our theoretical expectations. The frequency of PRA for the EU’s contested financial bailout policy remains relatively constant over time. We identified 112 PRAs for the post-May 2010 period and 89 for the post-July 2012 period.Footnote 11 This slight decline in the frequency of PRA is not statistically significant. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test shows that the monthly number of PRA statements per newspaper do not differ significantly across the two periods (see Online Appendix, Table A.9). However, in line with the suggested blame shifting effect, the share of PRA targeting EU member states decreases quite considerably. The share of PRA statements targeting EU member states drops from 69 out of 112 (62 per cent) in the post-May 2010 period to 30 out of 89 (34 per cent) in the post-July 2012 period. Conversely, the share of PRA targeting the ECB increases from 9 out of 112 (8 per cent) PRA statements in the post-May 2010 period to 38 out of 89 (43 per cent) in the post-July 2012 period. A chi-square test indicates that this shift in PRA shares targeting EU member states is not random. After all, the distribution of PRA statements across the two periods differs quite significantly from the null hypothesis of a random distribution which we can reject on the 99 per cent confidence level (see Online Appendix, Table A.7). Thus, as expected, delegation to an independent EU actor led to a lower share of blame publicly attributed to member state governments.

Figure 2. Public responsibility attributions for the EU’s financial bailout policy.

In the first period, PRA statements typically assigned blame to EU member states. For instance, in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung German economists criticized that ‘[t]he rescue decisions of the EU countries have invalidated the no bail-out clause of the Maastricht Treaty’ and ‘[m]aintaining them would further destabilize the euro zone’ as they would tempt creditors ‘to become careless in their lending and would create an excess of interest rate convergence’ (Fuest et al., Reference Fuest, Hellwig, Sinn and Franz2010; authors’ translation). By contrast, in the second period, PRA statements typically target the ECB. The ECB is criticized for doing ‘everything it can to “save” the euro […] [e]ven if its statutes prohibit monetary state financing’ and for ‘planning the use of further weapons of destruction [i.e., the OMT Program]’ (Steltzner, Reference Steltzner2012; authors’ translation). Further corroborating our expectations, many PRA statements that target the ECB come from member state government officials who actively try to shift blame to the ECB. For instance, German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble (CDU) reportedly blamed the ECB's actions as these ‘would endanger the monetary policy independence of the European Central Bank’ (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 2013; authors’ translation). Even opposition parties assigned blame to the ECB and not to the government. For example, Stephan Werhahn (Freie Wähler) criticized the ECB for putting a burden on German taxpayers and circumventing limitations imposed by the German constitutional court: ‘The limitation of liability is being undermined by ECB President Mario Draghi’ (cited by Plickert, Reference Plickert2012; authors’ translation).

Overall, the findings in the EU financial bailout policy case-pair corroborate the suggested blame shifting effect. As delegation to dependent, intergovernmental EU actors was gradually supplemented with delegation to an independent, supranational EU agent, the frequency of PRA remained largely unaffected, but the share of PRA targeting member state governments decreased. Blame shifted away from member state governments towards the ECB.

The EU's attempt to securing its maritime borders

The EU’s approach to the migration crisis was highly contested and politicized (Hutter & Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019) and gave rise to public blame games (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Schaper, De Lange and Van Der Brug2018; Heinkelmann-Wild & Zangl, Reference Heinkelmann-Wild and Zangl2020a; Heinkelmann-Wild et al., Reference Heinkelmann-Wild, Kriegmair and Rittberger2020). We will show that PRA targeted at EU member state governments changed when EU member states decided to protect the EU’s maritime borders by supplementing the EU agency Frontex with an external, non-EU actor, the so-called ‘Libyan coast guard’. Comparing PRA during the 12-months period following EU member states’ decision to delegate border control tasks to Frontex in November 2015 with the 12-months period following the endorsement of the ‘Libyan coast guard’ – in February 2017 – clearly supports the suggested blame obfuscation effect.

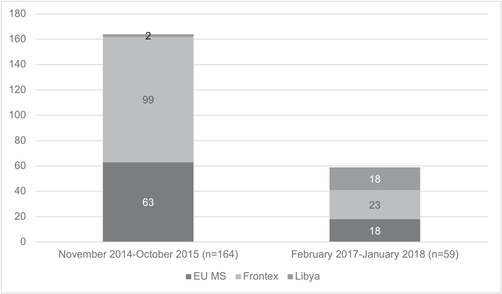

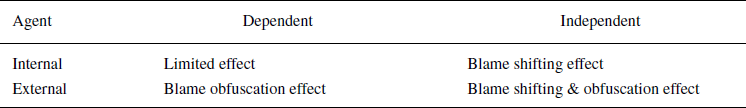

As Figure 3 shows, PRA frequencies and the shares of PRA targeting EU member state governments are in line with our theoretical expectations. Corroborating a blame obfuscation effect, the frequency of PRA decreases by almost 60 per cent from 164 PRAs in the post-November 2015 period to 59 PRAs in the post-February 2017 period.Footnote 12 This shift is statistically significant according to a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. We can reject the null hypothesis that the frequencies of PRA per month and newspaper do not differ across periods at the 0.05 level of significance (95 per cent confidence level) (see Online Appendix, Table A.10). As expected, the share of PRA directed at Frontex went down from 99 out of 164 (60 per cent) to 23 out of 59 (39 per cent), while the share of PRA targeting Libya went up from 2 out of 164 (1 per cent) to 18 out of 59 (31 per cent). Still, the share of PRA targeting EU member states governments stayed roughly the same: 63 out of 164 (38 per cent) in the post-November 2015 period as compared to 18 out of 59 (31 per cent) in the post-February 2017 period. This slight shift is not statistically significant according to a chi-square test (see Online Appendix, Table A.8). What differs substantively though is the overall frequency of PRA. The absolute number of PRA targeting member states decreased from 47 in the first period to 15 in the second. Thus, as expected, delegation to an external non-EU actor reduced the frequency of blame publicly attributed to member state governments.

Figure 3. Public responsibility attributions for the EU’s border control policy.

To be sure, while EU member state governments were targeted less frequently, they received a similar share of public responsibility attributions throughout the two periods under scrutiny. Regardless of whether Frontex or the ‘Libyan coast guard’ was used as agent, member state governments were held partially responsible for their agents’ activities. This is why the share of PRA to EU member states is not declining. Take the following statement of a journalist on the responsibility of EU member states within Frontex operations as a typical example for the first period: ‘[…] it is the direct responsibility of the EU nations involved in the operation of state naval vessels, police boats and helicopters in the Mediterranean to help people in distress. This also includes all naval officers who act on behalf of the EU in the “Frontex” or “Triton” network’ (Zielcke, Reference Zielcke2015; authors’ translation).

Similarly, in the second period we find many statements that hold EU member states accountable for operations conducted by the ‘Libyan coast guard’. For instance, a journalist criticized that ‘Italy supports training and equipment for Libyans through an EU programme’ given ‘the dangerous situation in the country of civil war’, while also blaming Libya because ‘[m]igrants there are largely without rights’ and ‘tens of thousands are held in camps under catastrophic conditions and are often subjected to maltreatment’ (Bachstein, Reference Bachstein2017; authors’ translation).

In the second period, the overall frequency of PRA went down substantially compared to the first period. To be sure, the border control issue remained salient, but we find considerably less PRA in the media coverage. In the first period, when Frontex was the main agent, the suffering of refugees in the Mediterranean was portrayed as an EU issue for which the EU and its member state governments were to be blamed. Consider the following example: ‘The European Union has created a system of defense against refugees and would rather let people drown in the Mediterranean rather than to save them’ (Prantl, Reference Prantl2015). In the second period, by contrast, the media coverage changed. It increasingly depicted the suffering of migrants in the Mediterranean as a ‘non-EU issue’ and thus refrained from attributing blame. The media reported, for instance, ‘that aid organisations rescue migrants and refugees ashore of Libya’ or that migrants ‘started in Libya with smuggler boats’ (Bachstein, Reference Bachstein2017; authors’ translation). The media covered the suffering without reporting blame attributions. Interestingly, even member state governments refrained from shifting blame to the ‘Libyan coast guard’ as their new agent. They did not need to because even their domestic opposition did not frequently assign blame to them. They rather stayed silent to avoid triggering blame games.

In sum, the findings in the EU border control policy case-pair corroborate the suggested blame obfuscation effect. Supplementing the EU agency Frontex with an external agent, that is, the ‘Libyan coast guard’, in patrolling the EU’s maritime borders did not affect the share of PRA targeting EU member state governments; it led to a substantive decrease of overall PRA frequency and thus reduced the blame attributed to member state governments.

Conclusion

The two pairwise comparisons corroborated the blame shifting effect and the blame obfuscation effect of delegation designs on blame attributions to governments. Blame shifted away from member states when, in the EU financial bailout case, delegation gradually shifted from a dependent to a more independent agent – the ECB. PRA frequencies stayed the same, but the share of PRA targeting member state governments decreased. Blame was obfuscated when, in the EU border control case, delegation gradually shifted from an internal to an external agent – namely the ‘Libyan coast guard’. The shares of PRA targeting member states stayed roughly the same, but PRA frequency decreased. The empirical analysis thus supports our claim that different modes of delegation come with different blame avoidance opportunities. Two caveats are in order: First, while our most-similar-case-design, based on pairwise comparisons of the same cases across two distinct time periods, allows us to control for confounding variables, such as policy field and actor involvement, we cannot exclude time-dependent effects. Most importantly, decreasing problem pressure over time might distort our findings. Still, as problem pressure decreased over time in both the EU financial bailout case and the EU border control case, it should have had a similar effect on PRA in both cases. This is not what we see. In the financial bailout cases PRA frequency remained rather constant, while it decreased in the border control cases. Moreover, the share of PRA targeting member state governments remained constant in the border control cases but decreased in the financial bailout cases. Therefore, we have confidence in the internal validity of our findings.

Second, while our most-similar-case-design allows us to control for confounding variables to single out the effects of delegation designs on PRA, we cannot be certain that our findings travel to other circumstances. This is endemic to most-similar-case-designs. For instance, we cannot know whether our findings from the media coverage of EU financial bailout and EU border control policies in Germany, France, and Austria hold in Greece and Italy which were arguably the countries most affected by these EU policies. Yet, Germany was arguably more affected by the two policies than the other two countries, and PRA patterns in the German quality press are similar to those in France (see Online Appendix, Table A.5 and A.6). This might indicate that our findings hold across different levels of affectedness. Only the PRA patterns in the Austrian quality press deviate slightly from those in France and Germany (see Online Appendix, Tables A.5 and A.6). This suggests that the blame avoidance opportunities of less powerful countries, such as Greece, are better than the ones of their more powerful counterparts in France and Germany. In any case, the external validity of our findings is limited.

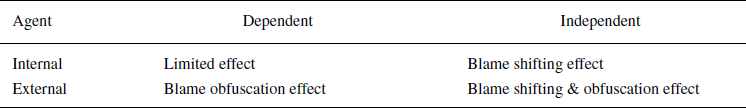

While our analysis affirms the plausibility of our claim that delegation designs affect public blame attributions to governments, more research is needed to assess the blame shifting effect and the blame obfuscation effect under circumstances that differ from our cases. In addition, while we assessed the plausibility of our two hypotheses separately, future research might also probe the combination of both hypotheses. While our analysis indicates that internal agents that are independent bear blame shifting effects and that external agents yield blame obfuscation effects, we have not assessed whether agents that are both external and independent at the same time bring the combination of both effects as suggested by Table 1. Future research might thus study the combination of both hypotheses.

Table 1. Effect of delegation on public blame attribution to the government

Note: The four types of delegation designs correspond to the four modes of indirect governance as defined by Abbott et al. (Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2020), that is, delegation, co-optation, trusteeship, and orchestration.

Moreover, while it is beyond the scope of this paper, our analysis also yields implications for governments’ choice of delegation designs. Based on rationalist assumptions, we would expect governments to opt for delegation designs, which reflect, inter alia, their desire to proactively avoid blame in case an issue might become contested in the future. When governments want to obfuscate blame, they will delegate tasks to external agents, such as foreign governments or private consultancy firms. And when governments want to shift blame, they will delegate tasks to independent agents, such as regulatory agencies, central banks or supranational IO bodies.

Finally, and relatedly, our findings point to the importance of delegation design for governments’ accountability.Footnote 13 After all, public responsibility attributions are an important accountability mechanism (see, e.g., Alcañiz & Hellwig, Reference Alcañiz and Hellwig2011; Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Arceneaux, Reference Arceneaux2006; Arceneaux & Stein, Reference Arceneaux and Stein2006; Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2014; Powell & Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993). PRA contributes in cases of contested policies or outright policy failures to ministerial resignations, electoral punishment, collapsing public support or policy change.Footnote 14 Delegation to internal and dependent agents does not necessarily harm accountability; but the more governments delegate to independent and/or external agents, the more they can evade blame and thus public accountability. It is thus imperative that any delegation act of this kind is accompanied by compensatory accountability mechanisms. If these compensatory mechanisms do not exist, delegation should not take place. In short: no delegation without compensation!

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the four anonymous reviewers, the editors, as well as the participants of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) Virtual General Conference 2020, the 6th Conference of the Section ‘International Relations’ of the German Association for Political Science (DVPW), as well as the ECPR Standing Group on the European Union (SGEU) 10th Biennial Conference. We are specifically grateful to Pieter de Wilde, Christian Kreuder-Sonnen and Christian Rauh for their valuable comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. We also would like to thank Louisa Klein-Bölting, Josef Lolacher, Andrea Johanson and Simon Zemp for their excellent research assistance.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Funding information

The work is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (project number 391007015).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix