Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by deficits in attention, and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association 2013). ADHD in adulthood is associated with educational and employment underachievement (Ahlberg et al. Reference Ahlberg, Du Rietz, Ahnemark, Andersson, Werner-Kiechle, Lichtenstein, Larsson and Garcia-Argibay2023), poor health (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Faraone, Tarko, McDermott and Biederman2014), and criminal justice system contact (Anns et al. Reference Anns, D’Souza, MacCormick, Mirfin-Veitch, Clasby, Hughes, Forster, Tuisaula and Bowden2023; Young and Cocallis Reference Young and Cocallis2021). Adverse outcomes are higher in untreated cohorts (Shaw et al. Reference Shaw, Hodgkins, Caci, Young, Kahle, Woods and Arnold2012). Identification of adult ADHD is important for accessing treatment (Katzman et al. Reference Katzman, Bilkey, Chokka, Fallu and Klassen2017). Many adult ADHD screening tools were originally developed based on childhood ADHD symptom profiles and may not best reflect the adult presentation. Adult mental health service professionals may have a low awareness of the clinical presentation of adult ADHD (Kooij et al. Reference Kooij, Bejerot, Blackwell, Caci, Casas-Brugué, Carpentier, Edvinsson, Fayyad, Foeken, Fitzgerald, Gaillac, Ginsberg, Henry, Krause, Lensing, Manor, Niederhofer, Nunes-Filipe, Ohlmeier, Oswald, Pallanti, Pehlivanidis, Ramos-Quiroga, Rastam, Ryffel-Rawak, Stes and Asherson2010) and miss the diagnosis (Adamis et al. Reference Adamis, Graffeo, Kumar, Meagher, O’Neill, Mulligan, Murthy, O’Mahony, McCarthy, Gavin and McNicholas2018). While noting that the symptom presentation is just one of the five criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) ADHD diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association 2013), it is argued here that a re-assessment and characterisation of the symptom presentation in adult ADHD is needed.

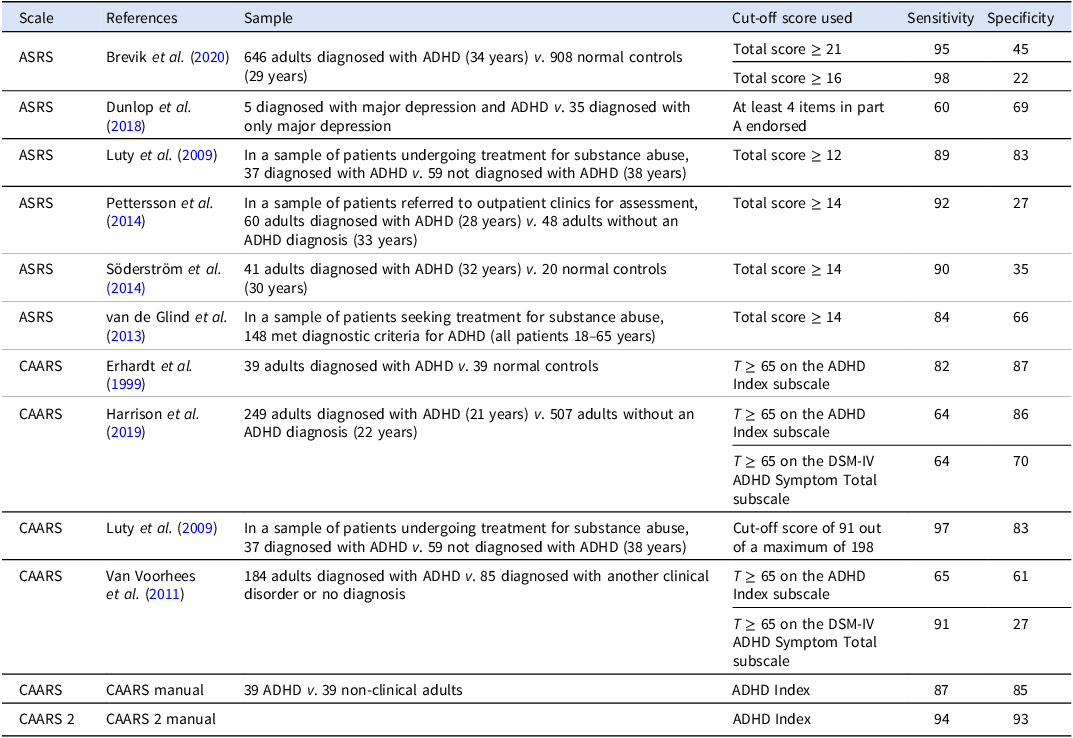

Screening scales, which compare respondents’ endorsed behaviours with those of ADHD and non-ADHD samples, are an important part of the diagnostic process, notwithstanding that the clinical interview is the main method of assessment used by clinicians. An accurate screening scale with high accuracy can facilitate access to appropriate assessment and treatment. The Adult ADHD Self-Rating Scale (ASRS) (Adler et al. Reference Adler, Kessler and Spencer2003) and the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS and CAARS 2) (Conners et al. Reference Conners, Erhardt and Sparrow1999; Conners et al. Reference Conners, Erhardt and Sparrow2023) are widely regarded as benchmark measures used during the process of assessing adult ADHD. These scales closely paraphrase symptoms listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association 2013). The accuracy of screening scales is examined using sensitivity and specificity: a scale must be able to identify those with ADHD (sensitivity) and those without (specificity) ADHD. The accuracy of the ASRS and the CAARS has been assessed (see Table 1). The ASRS has good sensitivity but poor specificity (Brevik et al. Reference Brevik, Lundervold, Haavik and Posserud2020; Dunlop et al. Reference Dunlop, Wu and Helms2018; Luty et al. Reference Luty, Rajagopal Arokiadass, Sarkhel, Easow, Desai, Moorti and El Hindy2009; Pettersson et al. Reference Pettersson, Söderström and Nilsson2018; Söderström et al. Reference Söderström, Richard and Nilsson2014; van de Glind et al. Reference van de Glind, van den Brink, Koeter, Carpentier, van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen, Kaye, Skutle, Bu, Franck, Konstenius, Moggi, Dom, Verspreet, Demetrovics, Kapitány-Fövény, Fatséas, Auriacombe, Schillinger, Seitz, Johnson, Faraone, Ramos-Quiroga, Casas, Allsop, Carruthers, Barta, Schoevers and Levin2013). The CAARS has varied sensitivity and specificity (Erhardt et al. Reference Erhardt, Epstein, Conners, Parker and Sitarenios1999; Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Nay and Armstrong2019) (Luty et al. Reference Luty, Rajagopal Arokiadass, Sarkhel, Easow, Desai, Moorti and El Hindy2009; Van Voorhees et al. Reference Van Voorhees, Hardy and Kollins2011).

Table 1. Sensitivity and specificity of the ASRS and CAARS

ASRS = Adult ADHD Self-Rating Scale; CAARS = Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Limitations with the accuracy of the ASRS and the CAARS can be partially attributed to the recognised limitations of the DSM 5 in describing symptoms of adult ADHD. First, DSM 5 ADHD symptoms are sometimes present in other clinical disorders, complicating identification of ADHD (McCann and Roy-Byrne Reference McCann and Roy-Byrne2004). Second, the symptom items do not sufficiently capture how symptom profiles change with age. Third, neither the CAARS nor the ASRS was designed in consultation with adults with lived experience of ADHD. It is noted that the classification systems were not designed to capture all aspects of ADHD, but to be able to separate ADHD from other conditions and be sufficiently accurate in reaching a diagnosis.

An updated version of the CAARS, the CAARS-2, was recently published and was found to have both higher sensitivity and specificity than the CAARS (Conners et al. Reference Conners, Erhardt and Sparrow2023). The CAARS-2 included more items capturing verbal and motoric hyperactivity, difficulties with executive function, impulsivity, and emotion regulation, but it does not include symptoms established in the adult ADHD literature, such as differences in time perception.

The symptom profiles for child and adult ADHD differ. With age, symptoms of inattention may become more prominent, while symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity tend to decline (Hechtman et al. Reference Hechtman, French, Mongia and Cherkasova2011). It is important to note that in some people, symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity may not reduce per se but become less visible to others (Downey et al. Reference Downey, Stelson, Pomerleau and Giordani1997). The nuances of symptom manifestation differ as well; for example, motor impulsivity is observed more in childhood, while cognitive impulsivity is observed more in adulthood (Sagvolden et al. Reference Sagvolden, Aase, Johansen and Russell2005).

Researchers have noted a set of adult ADHD symptoms that are not included in the diagnostic criteria of the DSM 5 or ASRS but are, to a limited degree, included in the CAARS. A better understanding of these symptoms in adults with ADHD may help increase the specificity of the screening tools. Hyperfocus is a state of complete focus on the task at hand to the extent that the individual is unaware of anything else (Ashinoff and Abu-Akel Reference Ashinoff and Abu-Akel2021), and has been observed in some adults with ADHD (Hupfeld et al. Reference Hupfeld, Abagis and Shah2019). Emotion-related difficulties include irritability and hot-temperedness (Kieling and Rohde Reference Kieling, Rohde, Stanford and Tannock2012), difficulties recognising emotions (Bodalski et al. Reference Bodalski, Knouse and Kovalev2019), and more salient negative affect (Hirsch et al. Reference Hirsch, Chavanon, Riechmann and Christiansen2018). It is noted that low frustration tolerance, irritability, and mood lability are associated features supporting the diagnosis within the DSM 5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) and in the assessment scales of Brown (Reference Brown2001) and Wender (Reference Wender1995). Sleep-related difficulties include taking longer to fall asleep and poorer sleep efficiency (Becker Reference Becker2020), more frequent night awakenings (Díaz-Román et al. Reference Díaz-Román, Mitchell and Cortese2018), poorer sleep quality (Gregory et al. Reference Gregory, Agnew-Blais, Mattthews, Moffitt and Arseneault2017), and daytime sleepiness (Díaz-Román et al. Reference Díaz-Román, Mitchell and Cortese2018). Finally, some adults with ADHD struggle to accurately estimate and reproduce time intervals, known colloquially as ‘time blindness’ (Mette Reference Mette2023).

The aim of this study was to interview individuals with lived experience of ADHD to understand better the adult ADHD presentation, to support future co-creation of an adult ADHD scale that might enhance screening accuracy. It was hypothesised that participants would report difficulties with both switching on and off attention, internalised and more subtle presentations of hyperactivity, impulsive behaviours associated with greater risk, difficulties with sleep, and difficulties with time perception. It was also hypothesised that participants would report emotional lability, with diversity in how it presented.

Methods

Study design

This study used a phenomenological qualitative approach, where concepts of adult ADHD were explored and understood anew vis-à-vis the lens and terminology of adults with ADHD (Fossey et al. Reference Fossey, Harvey, Mcdermott and Davidson2002). This acknowledges the expertise of individuals with lived experience. Semi-structured interviews were conducted using Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) methodology to explore experiences with attention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, executive function, emotional lability, sleep, and time perception across the domains of work, academics, social functioning, psychological functioning, and any other experiences the participant chose to discuss (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006).

Participants

Psychiatrists invited their adult patients diagnosed with ADHD to participate in the study. A holistic diagnostic assessment was conducted by the psychiatrists with each participant using the DIVA-5. The presence of co-occurring neurodevelopmental disorders was also assessed. Eligibility criteria included a minimum age of 18, fluency in English, a diagnosis of ADHD, and a T-score of at least 65 on the DSM-IV Inattentive Symptoms and/or DSM-IV Hyperactive–Impulsive Symptoms subscales of the CAARS. In total, 18 adults (10 female, 8 male) (M = 33.5, SD = 8.81, range 21–53 years) were interviewed. Six participants with comorbid autism spectrum disorder and one with comorbid bipolar disorder were excluded due to confounding symptom overlaps, leaving a final sample of 11 participants (seven female, four male) (M = 32.0, SD = 6.56, range 23–44 years). Participants’ ASRS scores ranged from 49 to 65 (M = 55.5, SD = 5.16). CAARS T-scores tended to be higher on the DSM-IV Inattentive Symptoms subscale (M = 82.5, SD = 7.12, range 72–90) than on the DSM-IV Hyperactive–Impulsive Symptoms subscale (M = 78.5, SD = 7.84, range 66–86).

The interviews concluded after data saturation was achieved (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2021). Ethics approval was provided by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee.

Measures

Demographic information was collected. Participants completed the ASRS (Adler et al. Reference Adler, Kessler and Spencer2003) and the CAARS Self-Report: Long Format (CAARS-S:L) (Conners et al. Reference Conners, Erhardt and Sparrow1999). The CAARS-2 was not available at the start of this study.

Procedure

Of the 11 participants, two were interviewed over Zoom and nine were interviewed in-person by one of the first two authors, after providing informed consent. The interview followed a semi-structured interview schedule and concluded with participants completing a brief demographic questionnaire, the ASRS and the CAARS-S:L. All participants received a $50 gift card for their time. Interviews lasted between 26 and 55 minutes and were audio recorded and transcribed using NVivo 14 transcription software (Lumivero 2023).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics for age, the ASRS, and CAARS were calculated. For the qualitative data, template analysis (codebook analysis) was applied (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2021; Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Serena, Emma and King2015). An initial codebook was created based on DSM 5-TR ADHD criteria (APA, 2022) using NVivo version 14 (Lumivero 2023). The codes were hierarchical, with top-level codes representing broad themes such as “Attention” that then encompassed narrower, specific codes such as “Making careless mistakes” and “Difficulty sustaining attention.” This initial template was then applied to participant transcripts by the first author. New codes were created whenever new information emerged that was not sufficiently represented by existing codes. Consequently, a blended inductive and deductive approach was used to understand the data (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006). A reflective journal was kept throughout this process to note interesting observations, explore how the first author’s existing knowledge of adult ADHD might interact with data interpretation, and minimise personal bias.

Following the first round of coding, the codebook was refined in consultation with the research team. Collaborating psychiatrists (TJ, SD) reviewed the codebook to ensure face validity. Three researchers then applied the codebook to one transcript each to familiarise themselves with the codes and identify areas for improvement. Of these three coders, one was a researcher in ADHD (KJ), and two (JV, JB) had lived experience of adult ADHD.

Several meetings were held between the coders to discuss modifications to the codebook. The updated codebook was then applied to a new transcript. All four coders used the same transcript to check the codebook’s reliability. A satisfactory level of reliability (80%) was achieved. The final codebook was applied by the first author to all transcripts. Appropriate quotes were selected for discussion in the results and tables to validate the research findings.

Results and discussion

Nine primary themes emerged: attention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, disorganisation, forgetfulness, activation, emotional lability, sleep, and time perception. Some primary themes had shared secondary themes due to difficulty identifying the underlying mechanism for a reported behaviour. As coding progressed, more secondary themes were added to represent experiences reported that were not mentioned in the DSM 5 nor in the literature. The final nine primary themes and their secondary themes reflect how participants’ data informed reorganisation of ADHD symptoms.

Across the nine primary themes, participants generally agreed that their experiences were “zero to 100” and “all or nothing”, explaining that symptoms typically manifested on extreme ends of the spectrum, and were sometimes completely absent, and sometimes debilitating. For example, they either struggled greatly with sustaining their attention or they maintained their attention to a task to such a strong degree that it was detrimental to their health and well-being. This switching on and off was under poorly regulated. This suggests dysregulation is a pervasive and broader theme experienced by adults with ADHD, which may be present across all the various symptom domains.

Experiences of inattention

Attention was the most frequently endorsed primary theme, and the secondary theme of “Difficulty Sustaining Attention” was endorsed by all participants. The DSM 5 symptoms of inattention were reported to some degree by all participants (see Supplementary Table 1). Other new secondary themes related to attentional difficulty emerged. Participants described inattention occurring unknowingly. Not realising that their attention had lapsed made it more difficult for participants to control and redirect their attention. Participants found that inattention occurred due to boredom, mind wandering, or being easily distracted, and as noted by the DSM 5, focus could be facilitated by interest in the task or task novelty.

The DSM 5 only considers attention difficulties from the perspective of inattention. The literature, however, has identified that attentional difficulties can also take the form of hyperfocus, the state of complete focus on a task to the extent of being unaware of anything else (Ashinoff and Abu-Akel Reference Ashinoff and Abu-Akel2021; Brod et al. Reference Brod, Pohlman, Lasser and Hodgkins2012; Hupfeld et al. Reference Hupfeld, Abagis and Shah2019; Ozel-Kizil et al. Reference Ozel-Kizil, Kokurcan, Aksoy, Kanat, Sakarya, Bastug, Colak, Altunoz, Kirici, Demirbas and Oncu2016). Hyperfocus occurred mostly during tasks that the participant deemed interesting but could also occur during uninteresting tasks if external pressures were present. Like inattention, hyperfocus occurred unknowingly, and participants could not control when it started or stopped. This caused them to engage in tasks at inappropriate moments, neglect tasks that they deemed more important, fail to re-enter a state of hyperfocus once they left it, and neglect physical needs like eating, sleeping, and going to the toilet.

Participants also reported a second type of sustained focus: hyperfixation. Hyperfixation lasted for longer periods of time than is typical of hyperfocus, for days or even weeks, and did not involve the sense of time slipping by or the neglect of physical needs. It occurred in relation to participants’ interests only, such as hobbies, sport, or music. While experiencing episodes of hyperfixation, participants thought of the activity constantly, or created as much time as they could in their daily schedules to engage in the activity. This is another example of the theme of dysregulation. Currently, no studies on adult ADHD specifically explore hyperfixation, but this phenomenon has been identified when exploring restricted interests in Autism (Turner-Brown et al. Reference Turner-Brown, Lam, Holtzclaw, Dichter and Bodfish2011). While participants with a diagnosis of autism were excluded from the study, hyperfixation may represent an overlapping, or co-occurring, neurodevelopmental symptom related to autism and ADHD. This requires further research.

Attentional difficulties appear in the domain of fine control of attention – what to pay attention to, when to withdraw attention, and for how long to attend. Attention regulation issues included difficulties switching attention off as well as on. Although the DSM 5 and the ASRS do not capture this theme of attention dysregulation, the CAARS and CAARS-2 contain one item that does: “Sometimes my attention narrows so much that I’m oblivious to everything else; other times it’s so broad that everything distracts me.” Inconsistency with fine control over attention is also presented in experiences of multitasking and task switching.

Hyperactivity

In their reports of hyperactivity (see Supplementary Table 3), some participants agreed with the DSM 5 description of “being driven by a motor.” For some, restlessness caused frequent fidgeting with their fingers, hands, and legs. For others, restlessness caused difficulties with relaxing or engaging in leisurely activities like watching a movie, echoing earlier research on how restlessness presents differently in adults with ADHD compared to children (Adler Reference Adler2004).

Although the ASRS and CAARS do well in capturing adult-specific experiences of hyperactivity, their items still pertain to physical, external hyperactivity. Participants expanded this perspective of hyperactivity by describing how it can also be experienced mentally. Mental hyperactivity was primarily experienced as racing thoughts that are simultaneous and difficult to decipher. Participants reported that mental hyperactivity makes it difficult to concentrate and increases distractibility. This aligns with emerging research suggesting that racing thoughts are a crucial aspect of adult ADHD that is distinct from inattentive mind wandering (Martz et al. Reference Martz, Bertschy, Kraemer, Weibel and Weiner2021; Martz et al. Reference Martz, Weiner, Bonnefond and Weibel2023), but this is a matter of debate, and further research is needed (Bozhilova et al. Reference Bozhilova, Michelini, Kuntsi and Asherson2018).

Racing thoughts appear to partially underlie symptoms of excessive talking. Some participants reflected that having too many simultaneous thoughts caused confusion, difficulty with expressing themselves, and difficulty falling asleep. This aligns with the association between the frequency of racing thoughts and insomnia severity (Martz et al. Reference Martz, Bertschy, Kraemer, Weibel and Weiner2021). Internal hyperactivity is an important feature of adult ADHD and should be explicitly assessed in adult ADHD screening tools.

Impulsivity

Participants endorsed the DSM listing of impulsivity symptoms, but some participants also talked about risk-taking, such as speeding when driving, substance use, and engaging in unsafe sexual activity (see Supplementary Table 4). The ICD currently includes risk-taking behaviours, while the DSM 5 does not. Others reported spending impulsively on unnecessary purchases, resulting in financial “chaos.” This aligns with research findings of poor financial decision-making associated with adult ADHD (Bangma et al. Reference Bangma, Koerts, Fuermaier, Mette, Zimmermann, Toussaint, Tucha and Tucha2019).

Although the CAARS has one item pertaining to risk, “I am a risk-taker or a daredevil”, this phrasing does not effectively assess all forms of risk-taking described by participants. The CAARS 2 contains several functional outcome questions assessing for difficulty managing finances and risky driving; however, it still does not capture risk-taking like substance use, unsafe sexual activity, extreme sports, and high-risk careers. Participants attributed risky behaviours to their impatience, need for immediate satisfaction, and thrill-seeking. These factors influencing risk-taking are not captured in the DSM, while the CAARS has only one relevant item, “I don’t plan ahead.” The CAARS 2 has relevant items of “I am impatient” and “I’d rather get a small reward right away instead of waiting for a big reward later” but does not account for thrill-seeking.

According to the DSM, impulsivity manifests as blurting and interrupting others. This was endorsed by participants, while other forms of conversational impulsivity were discussed, such as oversharing private information in inappropriate settings. This manifestation of blurting was not captured by the three scales.

Disorganisation

Participants experienced disorganisation as struggling to do things in order, messiness of personal belongings, losing things easily, and struggling to plan (see Supplementary Table 5). Disorganisation appeared to affect several life domains including finances, daily routines, work, and academic. For some, disorganisation caused strong feelings of being overwhelmed. The DSM’s symptoms of disorganisation are not comprehensively represented in the ASRS, CAARS, or CAARS 2.

Forgetfulness

The DSM includes a symptom about forgetfulness in daily activities (such as doing chores, running errands, or paying bills); however, participant experiences of forgetfulness are broader than what the DSM represents (see Supplementary Table 6). Participants reported difficulty keeping track of appointments, struggling to recall recent events, retain information, and remember other people’s names or the topic of ongoing conversations, instructions, and tasks that needed completing. Some participants also lost belongings as they struggled to remember where they had put them. The ASRS assesses forgetfulness through the item “How often do you have problems remembering appointments or obligations?”, while the CAARS asks generally about forgetfulness without providing specific examples or domains.

Activation

Participants struggled with activation (see Supplementary Table 7), describing difficulties with starting and completing tasks of their own volition, even ones that were deemed important. Difficulty starting and completing tasks was initially coded under inattention in accordance with the DSM; however, these difficulties were later found to be impacted by factors beyond attention, including hyperactivity, impulsivity, disorganisation, and time perception. Consequently, activation was made a primary theme to account for these differences in experience.

The DSM describes task avoidance occurring with unpleasant tasks, such as chores and mentally effortful tasks; however, it does not account for the role of motivation. Participants could start and finish unpleasant tasks in a timely manner when external pressures were present and provided motivation, such as having a second person nearby (body-doubling).

Activation was presented differently in participants. Some reported feeling stuck and unable to start tasks, especially if they were difficult or boring. Even if participants managed to start a task, they struggled with completion due to prolonged task exposure causing a loss of novelty or stimulation. Some described themselves jumping from one task to another rapidly without completing any of them, while others described spontaneously starting and completing tasks at inappropriate or inconvenient times. This variety in experiences is not fully represented in the DSM, ASRS, or CAARS.

Emotional lability

Many participants reported that ADHD affected their emotional experiences (see Supplementary Table 8). Emotions fluctuated quickly for some participants. Others endorsed intensity across a range of emotions including anger, sadness, and happiness. Some reported crying easily, while others reported feeling drained and exhausted by strong positive emotions. Most participants who endorsed rapid fluctuation and strong intensity in emotions specifically cited anger in their examples. Several participants experienced emotional intensity as heightened sensitivity to rejection.

These reported difficulties with emotional lability align with sentiments from existing literature (Asherson et al. Reference Asherson, Buitelaar, Faraone and Rohde2016; Christiansen et al. Reference Christiansen, Hirsch, Albrecht and Chavanon2019; Franke et al. Reference Franke, Michelini, Asherson, Banaschewski, Bilbow, Buitelaar, Cormand, Faraone, Ginsberg, Haavik, Kuntsi, Larsson, Lesch, Ramos-Quiroga, Réthelyi, Ribases and Reif2018). Although the diagnostic criteria of the DSM 5 and ASRS do not capture emotional lability, the CAARS has a few items. The Impulsivity/Emotional Lability subscale captures low frustration tolerance and mood swings, which were endorsed by participants. The CAARS 2 Emotional Dysregulation subscale captures the intensity of negative emotions and emotion regulation difficulties. Participants also identified other aspects of emotional lability not included in both the CAARS, such as mood swings occurring with positive emotions like happiness, and heightened sensitivity towards rejection by others.

Sleep

Several participants endorsed sleep difficulties (see Supplementary Table 9). They reported struggling to fall asleep even when feeling exhausted, resulting in fatigue during the day. Reasons for sleep difficulties included racing thoughts, physical restlessness, and hyperfocus. Other reported sleep difficulties included struggling to wake up due to fatigue. Notably, several participants denied experiencing problems with sleep, finding that they were typically able to fall asleep very quickly.

The CAARS does not capture sleep difficulties, but the CAARS 2 contains one question on difficulties with falling asleep, staying asleep, and feeling well-rested. This echoes existing research on sleep, where adults with ADHD experience shorter sleep duration, more nighttime awakenings, and subjectively poor sleep quality (Becker Reference Becker2020).

Time perception

Some participants reported that ADHD affected their perception of time (see Supplementary Table 10). Participants felt that time would slip away when they were not consciously paying attention to it, especially if they were engaged in an activity or in a state of hyperfocus. Time perception irregularities caused difficulties with time estimation, including overestimating the amount of time needed to complete undesirable tasks and underestimating the amount of time needed to meet a deadline. This aligns with earlier research on ADHD associations with time estimation (Mette Reference Mette2023; Valko et al. Reference Valko, Schneider, Doehnert, Müller, Brandeis, Steinhausen and Drechsler2010). Differences in time perception are not represented in the DSM and the ASRS. Although the CAARS contains one item on time perception, “I misjudge how long it takes to do something or go somewhere”, this item was removed in the CAARS 2 and was not replaced with an equivalent item.

Difficulties with accurately perceiving time led to struggles with punctuality. Although the DSM does not have a symptom for time perception differences, it does flag poor time management as a part of the symptom of disorganisation. The DSM does not account for coping strategies to mitigate this, such as showing up much earlier to appointments. This may cause adults with ADHD who experience significant difficulty with accurately perceiving time to be missed because they present as having good time management.

Implications

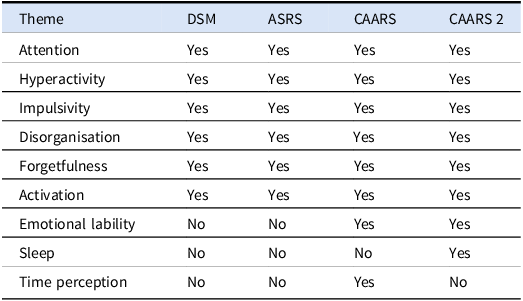

Our analysis of participants’ experiences of ADHD symptoms in adulthood identified nine core symptom domains. Broadly, the DSM and ASRS contain symptoms pertaining to six of these nine themes. The themes of emotional lability, sleep, and time perception do not feature in existing diagnostic frameworks (see Table 2). The CAARS includes symptoms for all themes except sleep, while the CAARS 2 includes symptoms for all themes except time perception.

Table 2. Nine primary themes and representation in the DSM, ASRS, CAARS, and CAARS 2

DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ASRS = Adult ADHD Self-Rating Scale; CAARS = Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale.

The secondary themes that emerged from the data revealed additional nuance to the expression of these nine themes, much of which was missing from the DSM and the screening scales. These secondary themes aligned with existing literature on symptoms of ADHD in adults and developmental theories for differences in presentation from childhood to adulthood. Where some themes were uniformly endorsed by all participants, other themes demonstrated variability across this study’s participant pool. One suggestion is for a glossary to be published that contains a full description of symptoms experienced by adults with ADHD, which could complement the DSM 5.

Symptom expression was shown to be impacted by each participant’s life circumstances and learned coping strategies. For example, some participants described managing their symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity by creating a highly active lifestyle that involved socially appropriate risk-taking. This echoes Antshel’s (Reference Antshel2018) finding that some ADHD symptoms can be useful for a person’s circumstances. Participants also described using coping strategies to mitigate symptoms of ADHD, for example, by being chronically early to avoid tardiness. Qualitative explorations have revealed similar sentiments where adults with ADHD develop various skills that help them cope and consequently mask the difficulties they have (Canela et al. Reference Canela, Buadze, Dube, Eich and Liebrenz2017).

There were some limitations to this study. Participants with a co-occurring diagnosis were excluded from the study, including six participants with comorbid autism spectrum disorder and one with comorbid bipolar disorder. This was done to reduce the influence of overlapping symptoms. We acknowledge the growing research on dimensional and symptom-based approaches for the diagnosis of neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders, which will help to advance our scientific understanding and clinical practice (Astle et al. Reference Astle, Holmes, Kievit and Gathercole2022; Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff, Bagby, Brown, Carpenter, Caspi, Clark, Eaton, Forbes, Forbush, Goldberg, Hasin, Hyman, Ivanova, Lynam, Markon, Miller, Moffitt, Morey, Mullins-Sweatt, Ormel, Patrick, Regier, Rescorla, Ruggero, Samuel, Sellbom, Simms, Skodol, Slade, South, Tackett, Waldman, Waszczuk, Widiger, Wright and Zimmerman2017). A one-hour interview was insufficient to fully capture the complexity of adult ADHD. Consequently, some themes warrant further exploration, such as hyperfixation and how it differs from hyperfocus, especially in the context of people with a dual diagnosis of autism and ADHD. Furthermore, the sensitivity and specificity reports of the current screening scales compare people with and without ADHD, rather than people with ADHD and people with co-occurring conditions such as anxiety, depression, and personality disorders. Further research is needed to improve upon these screening scales. Additionally, discussions of sleep difficulties were mostly centred on difficulty falling asleep due to hyperactivity. The literature and the CAARS 2 capture other ways that ADHD impacts sleep, including shorter sleep duration, subjective reports of poor sleep quality, daytime fatigue, and nighttime awakenings (Becker Reference Becker2020; Díaz-Román et al. Reference Díaz-Román, Mitchell and Cortese2018; Schredl et al. Reference Schredl, Alm and Sobanski2007). These aspects of ADHD require follow-up study. Some participants struggled to identify which experiences could be attributed to ADHD, as they did not know whether others without ADHD would share similar experiences. This difficulty was conflated for some participants by the recency of their diagnosis. Five of the 11 participants interviewed had been recently diagnosed within the year, and some reported still being in the process of understanding how ADHD affects them. The data from 11 participants will not capture all aspects of ADHD, such as the impatience and irritability experienced when waiting in a queue. Information provided was further constrained by the limitations of participants’ memory. Several participants reported struggling to think of relevant examples. An additional challenge was the inevitability of the interviewers’ preconceived notions of what ADHD entails. Interviews ranged from 26 to 55 minutes. While unavoidable due to differences in participant response styles, this could have led to greater representation of some experiences than others. Finally, although all participants appeared forthcoming in the interviews, it is possible that some may have withheld information due to fears of stigma.

In summary, of the nine themes that emerged from the data, six themes of attention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, disorganisation, forgetfulness, and difficulties with activation were included in the ASRS, CAARS, and CAARS 2. These scales, however, did not capture important nuances of these themes, which could enhance the specificity of a new screening scale. Adult ADHD appears to be associated with pervasive dysregulation of behaviour. Fine attention control is dysregulated in adults with ADHD. Hyperactivity occurs through mental restlessness and racing thoughts in many of the participants. Impulsivity and risk-taking behaviour were common experiences. Disorganisation and forgetfulness appeared across many life domains. Difficulty with activation presented differently across the participants. The remaining three themes of emotional lability, time perception, and sleep were not captured by the ASRS and were differentially captured by the two CAARS. Many participants reported quick and strong emotional fluctuations, and several reported sensitivities to rejection. Further research is needed on time perception and sleep difficulties associated with ADHD. This study highlights gaps in the current assessment tools and suggests directions for future research. Further research is needed to clarify the most pertinent items for screening for symptoms of adult ADHD and to determine which symptoms are distinct and which are shared with other common co-occurring disorders. By summarising the lived experiences of adults with ADHD and by highlighting additional symptom dimensions, this study will inform the development of more comprehensive assessment instruments.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2026.10175.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the generosity of all the participants who took part in this study.

Author contribution

IJJC and CS interviewed participants. IJJC coded the interviews and wrote the manuscript. JV and JB interpreted and coded the interviews. FM and DA designed the study. TJ and SD diagnosed the participants and reviewed the coding. KJ designed the study, supervised the project, coded the interviews, and co-wrote the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Melbourne. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.