Introduction

After the tumultuous elections of November 2023, in which the radical right-wing populist Party for Freedom/Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) emerged as the largest party, the Netherlands spent the first half of 2024 attempting to form a government that included the PVV. The PVV, along with the conservative-liberal Liberal Party/Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD), the agrarian-populist Farmer-Citizen-Movement/BoerBurgerbeweging (BBB), and the newcomer social-conservative New Social Contract/Nieuw Sociaal Contract (NSC), agreed on what they termed a ‘programme Cabinet’. In this arrangement, the relationship between the coalition parties in Parliament and the Cabinet was intended to be more distant than in recent years, with a politically neutral Prime Minister and governing parties' leaders remaining in Parliament. This marked the first time in over a century that the Prime Minister was not affiliated with one of the coalition parties. This arrangement paved the way for the most right-wing government in the Netherlands since the postwar era. In the second half of the year, the coalition's fragile nature became evident, as the Cabinet found itself on the brink of collapse on three separate occasions.

Election report

On June 6, the Netherlands held elections for its delegation to the European Parliament (EP). Public attention for the 2024 elections was relatively low, with media- and political attention in the final weeks of May and early June directed squarely towards Cabinet formation and installation (see below). Having already held two elections in the previous year—regional and national—there was seemingly little appetite for yet another election, which was reflected in the somewhat limited campaigning activities and media coverage. The main campaign themes were migration, the environment and the geopolitical role of the European Union (EU). Voter turnout was 46 per cent, which was a 4 percentage point increase from five years earlier, but still much lower than the almost 78 per cent turnout for the 2023 national elections. Van der Brug (Reference Van der Brug2024) speculates that the higher turnout may be due to the more substantive nature of the EP election campaign, compared to previous elections.

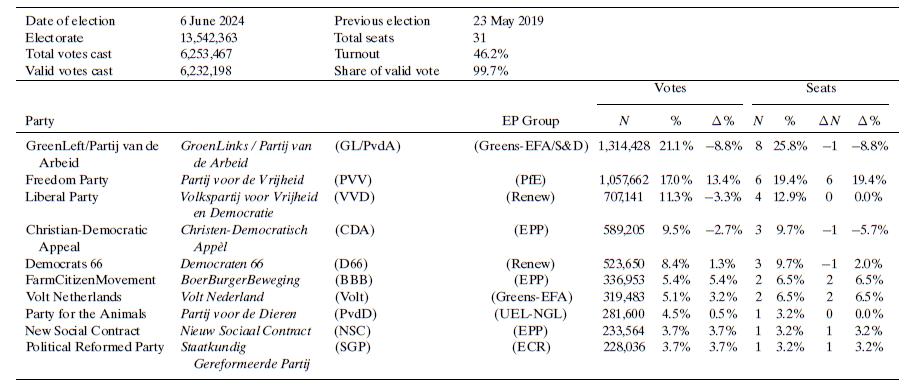

Information on elections to the EP in the Netherlands in 2024 can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament (EP) in the Netherlands in 2024

Notes:

1. Between the elections, the total number of seats changed, making the difference in seats different.

2. In 2019, the SGP ran on a joint list with the CU, winning one seat. The change in votes and seats sees the SGP as a new party.

Source: Kiesraad (2025). Verkiezingsuitslagen.nl. https://www.verkiezingsuitslagen.nl/

GreenLeft/GroenLinks (GL) and the Labour Party/Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA) ran on a joint list, which was led by the sitting member of EP (MEP) and Co-Spitzenkandidat for the European Greens, Bas Eickhout. Their campaign sought to combine the green transition with the pursuit of social justice. With 20 per cent of the vote and eight out of 26 seats, the joint list was the largest party in the 2024 elections. While the combined list performed markedly worse than the two parties had separately in the 2019 European elections, it did better than their joint effort in the 2023 national elections. After the elections, the Labour Party's MEPs joined the group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats, while the GL MEPs joined the group of the Greens/European Free Alliance.

The second-largest party in the elections was the PVV, led by Sebastiaan Stöteler, a municipal councillor in Almelo and regional councillor in Overijssel. The party's campaign centred on the need for the Netherlands to opt out from EU migration rules. Notably, the PVV had already abandoned its longstanding call for a Dutch exit from the EU in the fall of 2023 in an attempt to make the party koalitionsfähig. With 17 per cent of the vote and six seats, the party performed worse than in the national elections but significantly better than in the previous EP elections in 2019, when the party reached an all-time low and lost all of its seats.Footnote 1 After the elections, the PVV MEPs joined the newly founded Patriots for Europe group, which succeeded the Identity and Democracy group after the 2024 elections.

The VVD secured third place in the elections, with sitting MEP Malik Azmani at the helm. The VVD focused its campaign on the need for the EU to play a geopolitical role, particularly in the areas of foreign, defence and security policy. The party performed worse than in the 2023 national and 2019 European elections, winning just over 10 per cent of the vote but retaining its four seats. Despite criticism of fellow Renew Europe MEP Valérie Hayer during the campaign for the VVD's coalition talks with the PVV, the party remained a member of the Renew Europe group.

The Christian-Democratic Appeal/Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA) was led by sitting MEP Tom Berendsen. Similar to the VVD, the CDA advocated for a stronger role for the EU in foreign policy. With just under 10 per cent of the votes and three seats, the party performed significantly better than its disastrous showing in the 2023 national election but fell short of its 2019 result. It remained a member of the European People's Party (EPP).

The progressive-liberal Democrats 66/Democraten 66 (D66) was led by Gerben-Jan Gerbrandy, who had served as an MEP between 2009 and 2019. The party remained committed to further the integration and democratisation of the European Union. Winning just under 10 per cent of the vote and securing three seats, D66 improved on its results from the previous national and European elections. It remained a member of Renew Europe.

The BBB participated in EP elections for the first time, with former CDA policy advisor in the EP, Sander Smit, as its lead candidate. The party presented a manifesto that called for both less EU interference (specifically where EU regulations restrain the Dutch agricultural sector) and more EU action (such as increased political cooperation). The party secured just over 5 per cent of the vote and won two seats. After the elections, it joined the EPP group.

Volt, a pan-European party already represented in the Dutch Parliament (with two seats) and in the EP (through its German MEPs), did not have a Dutch EP delegation as yet. The party chose former Volt Europe chair Reiner van Lanschot as its lead candidate. Volt's key policy plan is a federal Europe. The party garnered just over 5 per cent of the vote and secured two seats, which marked a significant improvement, as this result exceeded both its 2019 European election result and its 2023 national result combined. Just like Volt Germany, Volt Netherlands joined the group of the European Greens/EFA.

The Party for the Animals/Partij voor de Dieren retained its seat in the EP. The party focused on the need to reform the European Common Agricultural Policy in order to improve the living standards of animals and the quality of nature in the EU and combat climate change. Led by sitting MEP Anja Hazenkamp, the party secured slightly less than 5 per cent of the votes. It continued as a member of the Group of the United Left-Nordic Green Left.

NSC, which had been founded in August 2023, also participated in the EP elections for the first time. The party was led by Dirk Gotink, former spokesperson for EPP chair Manfred Weber. NSC called for a stronger geopolitical role of the EU while advocating for a limited role in housing and social security and restricting its ability to take on debt and tax EU citizens and companies. The party won just below 4 per cent of the vote, which translated into one seat. This result was significantly lower than its spectacular entry in the 2023 national Parliament elections. It joined the EPP group.

In 2019, the conservative-protestant Political Reformed Party/Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij (SGP) ran on a joint list with the Christian-social ChristianUnion/ChristenUnie, (CU) in 2019. This time, however, the parties ran separately, with sitting MEPs Bert-Jan Ruissen (SGP) and Anja Haga (CU) as their respective lead candidates. Both parties focused on the need for the EU to prioritise farmers and religious freedom, but the SGP adopted a more Eurosceptic stance than the CU. The SGP retained its seat in the EP, while the CU lost its seat. The SGP joined the Group of European Conservatives and Reformers.

Cabinet report

At the start of the year, the negotiations about the coalition agreement were still ongoing and would conclude just before spring. During the same period, the sitting Rutte IV Cabinet saw major changes.

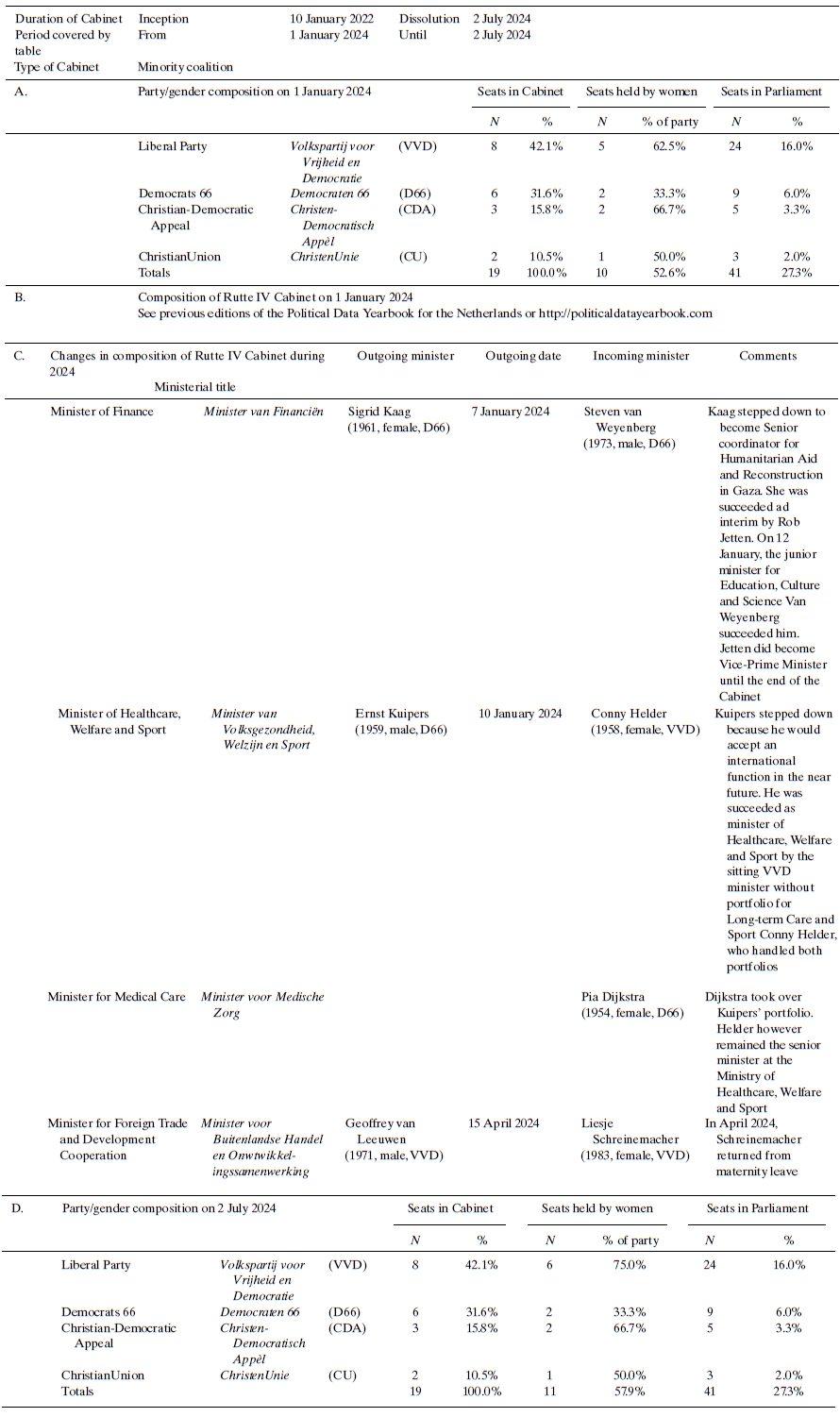

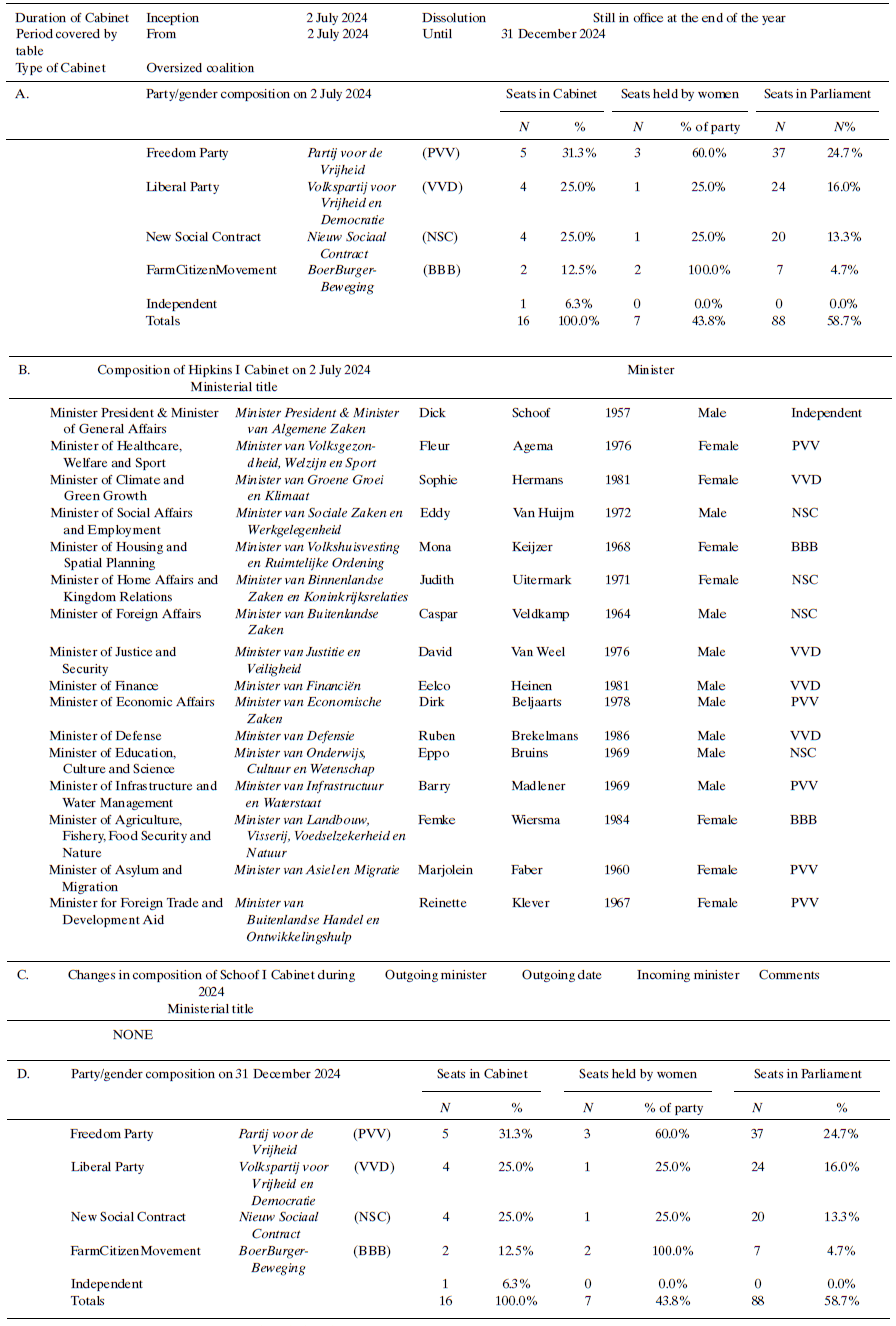

Information on Cabinet composition of Rutte IV and Schoof I in the Netherlands in 2024 can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Rutte IV in the Netherlands in 2024

Source: Parlementair Documentatiecentrum (PDC). (2025); https://www.parlement.com/

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Schoof I in the Netherlands in 2024

Source: Parlementair Documentatiecentrum (PDC). (2025); https://www.parlement.com/.

Rutte IV Cabinet

In parallel to the formation of the new government, several changes occurred with the caretaker Rutte IV government. On 8 January, Sigrid Kaag, the Minister of Finance, stepped down to become United Nations Senior Humanitarian and Construction Coordinator for the Gaza Strip. Her duties were temporarily taken over by D66 Vice-Prime Minister Rob Jetten until 12 January, when Steven van Weyenberg was appointed as her permanent successor. Rob Jetten retained his position of vice-PM. Van Weyenberg had only recently been appointed junior Minister of Education, Culture and Science in December, and was succeeded in that role by Fleur Gräper, former member of the Groningen Provincial Executive and former D66 party chair.

On 10 January, Ernst Kuipers, the D66 Minister of Healthcare, Welfare and Sports, also left the Cabinet in anticipation of a new international position. His portfolio was initially taken over by the Minister for Long-term Care and Sports, Conny Helder. On 2 February, Pia Dijkstra became Minister for Medical Care, while Helder retained K position as minister with final responsibility for the ministry, keeping her original portfolio focused on Long-term Care and Sports. On 1 May, Kuipers was appointed Distinguished University Professor and Vice-President of Research at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. On 25 May, Vivianne Heinen, the State Secretary for infrastructure and water management, went on maternity leave, and the Minister at that department took over her portfolio. On 26 June, Mark Rutte was selected as the new Secretary General of NATO, a position he took up on 1 October.

Coalition formation

Appointed at the end of 2023, Ronald Plasterk, a former Labour Party minister and columnist for the right-wing newspaper De Telegraaf, led talks between the PVV, VVD, NSC and BBB. Initially, these talks focused on establishing ‘a shared baseline for safeguarding the Constitution, fundamental rights, and the democratic rule of law’,Footnote 2 before expanding to cover a range of themes including migration and government finance. From the very beginning, the coalition discussions were troubled by the fact that the NSC, in particular, had fundamental concerns about governing with the PVV.

On 7 February, NSC withdrew from the coalition negotiations after receiving long-term financial estimates from the ministries. The party's unease with the negotiations was reflected in the communication about the breakdown of coalition talks, which was highly unusual; the media was informed before Plasterk as well as the other coalition partners, who were notified via WhatsApp. Notwithstanding this major hiccup, the final report by Plasterk found sufficient potential to continue the negotiations—on the condition that the new government would be ‘extraparliamentary’ in nature. This initial unease and mishandling of communication paved the way for future crises.

On 14 February, Kim Putters, chair of the Social-Economic Council and former Labour Party Senator, was appointed informateur by a parliamentary majority at the proposal of Geert Wilders. His role was to explore which kind of political cooperation would be possible. This round of negotiations was complicated by the VVD Senate Group's announcement that it would support a bill by caretaker State Secretary Van der Burg (VVD) to allow the central government to force municipalities to house asylum seekers. The PVV strongly opposed this bill because it would undermine the autonomy of municipalities to decide on whether they would allow asylum seekers into their local community. The party indicated that this would lead to an impasse in the government formation process, though it did not. On 14 March, Putters advised the House to pursue what he called a ‘programme Cabinet’, where parties would agree on a brief, baseline coalition agreement, no party leaders would serve in the Cabinet and only half of the ministers would be party politicians. This would allow for a greater political distance between the Cabinet and the coalition parties in Parliament, following decades of close coordination between the two.

On 20 March, Elbert Dijkgraaf, a former SGP MP, and Richard van Zwol, a member of the Council of State, former high-ranking civil servant, and CDA member, were appointed as informateurs. Both were experienced operatives in national politics and government: Dijkgraaf had been the SGP's spokesperson on finance, while Van Zwol had led a State Committee on migration.

Historically, the process of coalition formation was characterised by strict radio silence by all parties involved: Negotiations occurred behind closed doors. Party leaders and informateurs would only speak in general terms about what was on the table. The 2023–2024 formation occurred much more in the public eye, with party leaders frequently using the social media platform X. For instance, Geert Wilders used the platform to mobilise his followers with anti-immigration rhetoric, and when NSC dropped out of the negotiations, the remaining parties publicly reacted to each others’ messages to present a united front.

On 16 May, the four negotiating parties announced that they had reached a ‘framework agreement’ titled ‘Hope, Courage and Pride’. This relatively short coalition agreement would be further worked out by the new Cabinet after ministers were installed. The agreement focused on key issues, representing the priorities of the PVV, BBB, NSC and VVD: migration, agriculture, government reform and the budget. The four parties agreed on a restrictive migration policy, particularly limiting asylum migration, and wanted the new government to declare an asylum crisis that would allow the Netherlands to bypass international agreements on the issue, should ‘substantive justification’Footnote 3 be found. On agriculture, the parties agreed to seek support from the EU for exceptions to nitrogen pollution rules, which previous governments had also sought but not received. This should give the Dutch agricultural sector a long-term perspective, where previous governments had considered reducing the number of cattle in the country. On the budget, the parties committed to adhering to the European Stability and Growth Pact, enacting sizable tax cuts for families and businesses, and drastically cutting the civil service, pushing for cutting the Dutch contribution to the EU in budgetary framework negotiations, and development aid, to fund these budgetary changes. The existing ‘transition fund’ of 24 billion euros to buy out nitrogen-emitting farms near nature reserves was scrapped, with 5 billion of it retained for stimulating emission-reducing innovations. On foreign affairs, the parties agreed to continue to support Ukraine politically, military, financially and morally in its fight against Russian aggression, despite the PVV's previous opposition to providing military support for Ukraine. The coalition agreement also included government reforms—which were mainly proposals by NSC to change the electoral system to improve regional representation, and the establishment of a constitutional Court (discussed in detail below).

On 22 May, Richard van Zwol was appointed formateur. In the last 50 years, the formateur was the intended Prime Minister, but in this case, the parties could not agree on a candidate during the final stage of the formation. According to media reporting, Ronald Plasterk, the PVV's preferred candidate, was vetoed by NSC over issues surrounding his personal integrity related to his work as a professor in Molecular Genetics at the University of Amsterdam. Other candidates reportedly considered for the role of Prime Minister included Kim Putters, the chair of the Social-Economic Council who had served as the second informateur, Marnix van Rij, CDA State Secretary for Finance, and Richard van Zwol himself, but all declined. To avoid delays in the process, Van Zwol was appointed formateur to form the new Cabinet, including the selection of a Prime Minister.

On 28 May, Dick Schoof, the highest civil servant at the Ministry of Justice and Security, was nominated as the common Prime Minister candidate for the four parties. Schoof, a former Labour Party member, had served as the head of both the General Intelligence and Security Service and the National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism. In the week of 17 June, Van Zwol and Schoof received the nominated ministers. The PVV provided five ministers and four state secretaries for the Schoof Cabinet. At Healthcare, Welfare and Sport, the PVV nominated the long-serving PVV MP Fleur Agema and at Infrastructure and Water Management, he nominated long-serving PVV MP Barry Madlener. For the newly formed Ministry of Migration and Asylum, Wilders nominated long-standing PVV MP Gidi Markuszower. However, Wilders withdrew his nomination after the background check by the General Intelligence and Security Service. This agency had previously warned against nominating Markuszower for Parliament in 2010 due to his sharing of information with a foreign government, generally assumed to be Israel. He was replaced by another PVV MP, Marjolein Faber. Markuszower had also been intended to serve as Vice-Prime Minister, a role now taken by Agema. For Economic Affairs, Wilders nominated Dirk Beljaarts, chair of the hospitality industry association, who applied to relinquish his Hungarian nationality prior to his nomination. On Foreign Trade, Wilders nominated former MP Reinette Klever. As State Secretary for Kingdom Affairs and Digitalisation, he nominated the former VVD MP Zsolt Szabó, who relinquished his VVD membership prior to his nomination. As State Secretary for Safety and Justice, he nominated Rotterdam local councillor for Leefbaar Rotterdam, Ingrid Coenradie. As State Secretary for Public Transport and the Environment, he nominated Flevoland provincial executive Chris Jansen. Finally, as State Secretary for Long-term Care, he nominated PVV MP Vicky Maeijer. Thus, although the PVV managed to supply ministers and state secretaries for the new Cabinet, the nominees were either from outside the PVV ranks, or party loyalists with long-standing ties to the PVV but limited administrative experience, reflecting the lack of organisational depth of this memberless party.

The VVD secured four ministerial positions: Defense, Finance, Climate and Green Growth (a new ministry), and Justice and Safety. They nominated MPs Ruben Brekelmans, Eelco Heijnen and Sophie Hermans, for the first three posts, and David van Weel, the assistant to the NATO Secretary General, for the latter. Hermans also became Vice-Prime Minister. The VVD also secured the three state secretaries (Primary and Secondary Education; Participation and Civic Integration; and Youth Prevention and Sports). As State Secretary for Primary and Secondary Education, they nominated Mariëlle Pauw, who had been serving as the Minister for Primary and Secondary Education. She was the only continuing person in the Cabinet but she was demoted to State Secretary. As State Secretary for Participation and Civic Integration, they nominated Jurgen Nobel, a local executive from Haarlemmermeer. As State Secretary for Youth, Prevention and Sport, Vincent Karremans, a member of the Rotterdam local executive, was nominated.

NSC nominated the ministers for Home Affairs and Kingdom Relations, for Social Affairs and Employment, for Foreign Affairs and for Education, and Culture and Science. They nominated their MPs Judith Uitermark, Eddy van Hijum and Caspar Veldkamp, as well as former CU MP Eppo Bruins, who relinquished his CU membership prior to his nomination. Van Hijum became Vice-Prime Minister. NSC also nominated the State Secretary for Legal Protection (at the Ministry of Justice and Safety), as well as two state secretaries at the Ministry of Finance—one for the Allowance System and Customs, and another for Taxation. The new Justice Secretary, Teun Struycken, did not become a member of the NSC. At Finance, NSC nominated candidate MP and prosecutor Nora Achahbar as well as Folkert Idsinga, who had been a VVD MP before joining NSC.

Finally, the BBB claimed the ministers of Housing and Spatial Planning (a new ministry) and Agriculture, Fishery, Food Security and Nature (a new name). They nominated sitting BBB MP and former CDA State Secretary for Economic Affairs and Climate, Mona Keijzer, and Friesland Provincial Executive Femke Wiersma, who was well known from her participation in the popular television show Boer zoekt Vrouw (Farmer Wants a Wife). Keijzer also became Vice-Prime Minister. BBB also claimed the state secretaries for Agriculture, Fishery, Food Security and Nature; Defense; and Groningen Reconstruction (at the Ministry of Home Affairs and Kingdom Relations). At Agriculture, they nominated candidate MP Jean Rummenie, at Defense, MP Gijs Tuinman and at Home Affairs, Groningen Provincial Councillor Eddie van Marum.

The goal set by Putters to have half of the 29 Cabinet members come from outside the political arena was achieved: 17 of the ministers and state secretaries had previously served as MP, two were candidate MP, and five had experience in subnational government. Arguably, the PM (Schoof), two ministers (Van Weel, Beljaarts) and one state secretary (Struycken), came from outside the political arena, although the first two had been high-ranking civil servants. As mentioned above, two individuals gave up their membership in other parties to join the Cabinet. Between 20 June and 26 June, the Second Chamber held hearings with candidate ministers and state secretaries. This process, introduced just before the 2023 elections, sits in some tension with the Dutch constitutional norm of negative parliamentarism, where the Dutch House does not hold an investiture vote on individual ministers or on the cabinet as a whole. On 2 July, the Cabinet was sworn in by the King, and on 13 September, the Cabinet presented its government programme, further elaborating the plans outlined in the framework agreement.

Cabinet Schoof

In the first half year of its existence, the new Cabinet faced three major crises that threatened the continuation of the political experiment. The first crisis occurred in the night of 29 to 30 August, when the party leaders negotiated the budget. The VVD wanted to ensure that people whose primary source of income is employment saw a larger increase in purchasing power than those relying on benefits, while NSC wanted the opposite. At that point, NSC leader Omtzigt informed the other negotiators that his party would not support the budget. If NSC had actually voted against the budget, it would have led to a fall of the Cabinet. After an intervention by PVV leader Geert Wilders, Omtzigt agreed to the budget version preferred by the VVD. In response to the tense relations among the coalition leadership, the weekly coordination meeting of coalition Parliamentary Party Group (P leaders was reinstated, a practice that had previously been abolished to allow for more freedom for individual coalition parties.

The second crisis concerned the plan in the framework agreement to declare an official emergency to implement emergency measures aimed at limiting the inflow of asylum seekers, including not granting permanent refugee status and restricting family migration. Although this plan had been included in the framework agreement, it was made conditional on the decision being ‘substantially justified’. Legal scholars raised doubts about whether the current circumstances truly warranted such a measure, as emergency legislation is typically reserved for exceptional circumstances like floods or pandemics. During the debate on the Speech from the Throne, the Prime Minister, under pressure from the temporary leader of NSC, Van Vroonhoven, shared the civil servants’ advice on the use of emergency legislation. This advice was highly critical of the possibility of sufficient justification for such a measure. Despite this, PVV leader Wilders and the Minister for Asylum and Migration, Faber, remained strongly committed to the emergency measures and threatened the end of the coalition if the state of emergency was not declared. Under the leadership of Schoof, the PPG leaders from the four coalition parties decided to renegotiate the migration paragraph of the agreement. They reached a resolution on 24 October. Instead of pursuing emergency measures, the Cabinet would draft a migration bill, which they would ask Parliament to address urgently. The bill would cover proposals already outlined in the coalition agreement and the government's plan.

On 1 November, Folkert Idsinga, the State Secretary for Fiscal Affairs, announced his resignation following pressure from Geert Wilders, who had publicly (via social media platform X) demanded transparency regarding Idsinga's investment portfolio. Idsinga's resignation did not trigger a coalition crisis, and he was succeeded by NSC MP Tjebbe van Oostenbruggen on 15 November.

On 15 November, as Noura Achahbar, the State Secretary for the Benefits System and Customs, resigned over what she described as ‘polarising interactions in the last weeks’.Footnote 4 This caused the third crisis. Her resignation followed an episode of antisemitic violence by youth with Middle Eastern and North African backgrounds, targeting Israeli supporters of the football team Maccabi Tel Aviv in Amsterdam during the night of 7 and 8 November. These events cannot be seen independently from the Israeli War on Gaza. The violence in Amsterdam was compounded by harsh statements from some Cabinet officials, such as Prime Minister Schoof, who said during his press conference that ‘we have a problem with civic integration’, and the Liberal Secretary for Participation and Integration, Nobel, who allegedly said during a closed Cabinet meeting that ‘a large share of the Islamic youth does not subscribe to our values’.Footnote 5 While it remains unclear why exactly Achahbar resigned, it is likely that it had something to do with these expressed views. After her resignation, there was a brief period of uncertainty, as other NSC Cabinet members considered stepping down, which could have brought down the entire cabinet. However, after a session of the Cabinet, which the leaders of the four coalition PPGs also attended, no further ministers resigned, and the government held firm. On Tuesday 19 November, two NSC MPs stepped down from Parliament in solidarity with Achahbar. On 13 December, Achahbar's successor, NSC MP Sandra Palmen, was sworn in by the King.

Parliament report

The newly installed Schoof Cabinet did not have a majority in the Senate, requiring support from other parties to pass legislation. The first controversial issue was the value-added tax (VAT) on cultural activities and sports, which was part of the proposed tax plan. On 14 November, the leaders of D66, CDA, CU and SGP in the House struck a deal with the government: Their House PPGs would vote in favour of the tax plan, provided that the Minister of Finance, Heinen, assured them that the Cabinet would propose an alternative VAT reform that would raise enough revenue without targeting culture and sports. Their Senate PPGs were expected to follow this example.

The second controversial proposal involved a two billion euro cut on education spending, which represented about 3 per cent of the education budget. On 12 November, a compromise was reached in the House between the leaders of the coalition parties and those of CDA, CU, SGP and JA21. Their House PPG would vote in favour of the education budget, including a cut of 1.2 billion euros, which was smaller than initially proposed. D66, which had also been initially involved in the negotiations, ultimately walked away from the talks after concluding there was insufficient room to achieve their desired outcomes. Again, their Senate PPGs were expected to follow this example.

Early analyses of the parliamentary behaviour of the Schoof Cabinet indicate weaker coalition unity. The coalition parties tended to vote as a single bloc less frequently than in previous governments.Footnote 6 Where during the Rutte IV Cabinet, the four coalition parties voted the same in more than 80 per cent of votes, the parties have only done so in 65 per cent of cases under the Schoof Cabinet. These numbers are similar to the Rutte I Cabinet, in which the PVV operated as a support party, and the cooperating parties voted together in 70 per cent of votes. The PVV, in particular, often voted differently from its coalition parties, frequently supporting motions from parties further to its right. On legislation and budgetary matters, however, the coalition has generally voted as a unified bloc.

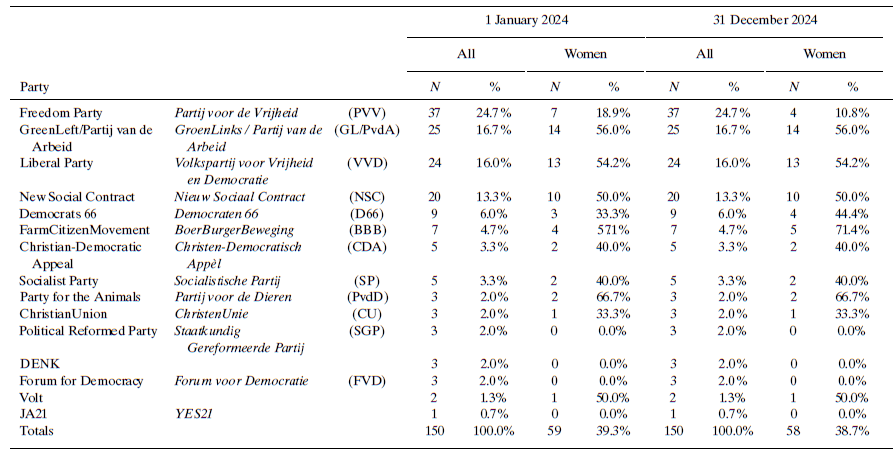

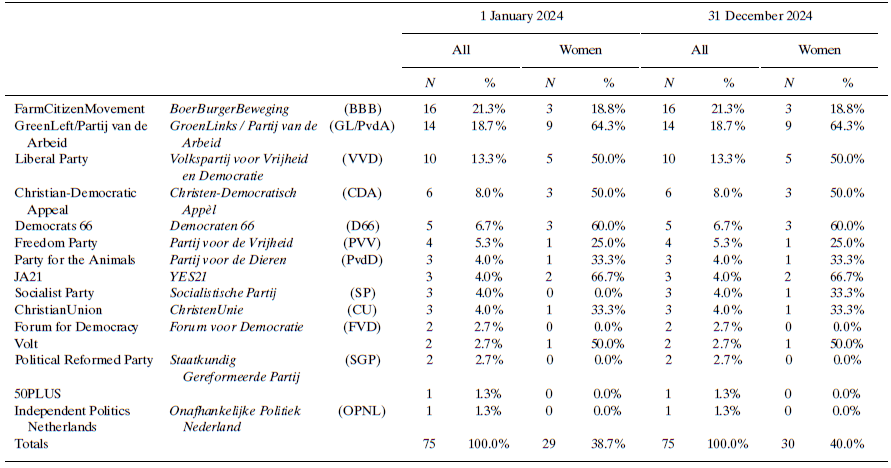

Information on party and gender composition of the lower house and the upper house of Parliament in the Netherlands in 2024 can be found in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal) in the Netherlands in 2024

Notes:

1. One of the PvdD MPs is non-binary.

2. DENK means ‘Think’ in Dutch and ‘Equal’ in Turkish.

Source: Parlementair Documentatiecentrum (PDC). (2025); https://www.parlement.com/.

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the upper house of Parliament (Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal) in the Netherlands in 2024

Source: Parlementair Documentatiecentrum (PDC). (2025); https://www.parlement.com/.

Institutional change report

The coalition agreement included a wide-ranging and ambitious package of reforms aimed at overhauling the political system in the Netherlands. One of the key proposals was the introduction of a new electoral system that would strengthen the regional bond between citizens and their representatives. Currently, the Netherlands uses proportional representation in what is effectively a single national electoral district. The government programme specified that the Netherlands would adopt a system with multimember districts and national compensation seats, modelled on the Danish electoral system. This change would not require a constitutional revision. Additionally, the agreement proposed removing the prohibition on judicial review of legislation from the constitution; the Netherlands is currently the only country in the EU to explicitly ban courts from assessing the constitutionality of legislation. A newly established constitutional court would instead be tasked with judicial review, allowing judges to assess whether laws conflict with the civil and political rights enshrined in the Constitution. The agreement also included plans to reform the Council of State. This body currently serves two functions: It is a key advisor to the government on proposed legislation and it serves as the highest court for administrative law. While currently these two functions are divided over two divisions, the agreement proposed to split the Council into two separate organisations, each with distinct functions.

Both the coalition agreement and the government programme noted that the constitutional revision concerning the introduction of a binding corrective referendum would continue without committing parties to vote in a particular way. This initiative, introduced by SP MP Temmink, had already passed its first reading in both houses of Parliament before the 2023 elections. A second reading, however, would require a two-thirds majority in both houses.

The coalition agreement also committed to strengthening the right of information of members of Parliament. It would allow Parliament itself to assess whether information is being rightfully withheld from MPs on the basis of ‘state interest’. This call for greater transparency is a direct response to the childcare benefit scandal, in which the government withheld information from both victims and Parliament (Otjes & Hansma Reference Otjes and Hansma2021). Further, the agreement emphasised the importance of independence for the Electoral Council. The coalition parties pledged to extend the Council's mandate, transforming it into the Electoral Authority, tasked with overseeing the electoral process more comprehensively.

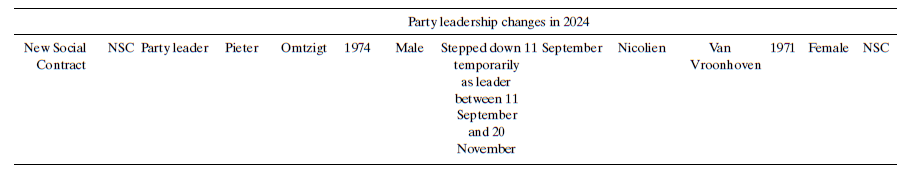

Information on changes in political parties in the Netherlands in 2024 can be found in Table 6.

Table 6. Changes in political parties in the Netherlands in 2024

Source: Parlementair Documentatiecentrum (PDC). (2025); https://www.parlement.com/.

Party report

On 23 September, Pieter Omtzigt, the leader of NSC, temporarily stepped down from his leadership position on the advice of his doctor. During his absence, Nicolien van Vroonhoven, the party's deputy leader, took over the role. Omtzigt returned on 20 November.

Issues in national politics

Migration and civic integration continued to be dominant political issues, evident in the fact that two of three near crises within the coalition centred around migration (the proposed emergency law) and civic integration (the eruption of antisemitic violence in Amsterdam). As the macroeconomic indicators were generally positive, economic issues did not play a major role on the agenda: Inflation stood at 3.2 per cent (down from 4.1 per cent in 2023, but above the Eurozone average of 2.4 per cent); economic growth was 1.0 per cent (up from 0.1 per cent in 2023 and close to the Eurozone average of 0.9 per cent); unemployment was 3.7 per cent (just higher than 3.6 per cent in 2023, but well below the Eurozone average of 6.4 per cent); and the country's budget deficit was 0.9 (just higher than 0.4 per cent in 2023, but below the Eurozone average of 3.1 per cent).Footnote 7

The second major (ongoing) issue involved nitrogen emissions. In 2019, the Council of State (as the highest administrative court) ruled that as long as the government does not adopt policies that substantially reduce nitrogen emissions, new construction plans should be accompanied by actual reductions of nitrogen emissions (Otjes & Voerman Reference Otjes and Voerman2020). The Council ruled that the existing nitrogen regulations did not comply with the requirements of the EU Habitat Directive, which obliges the Netherlands to improve the quality of its natural environment. Nitrogen pollution, mainly from cattle farming, is an important cause of the deterioration of Dutch nature. The Rutte IV government had planned to reduce nitrogen emissions by buying out cattle farms near nature reserves, including the possibility of forced buyouts (Otjes & De Jonge Reference Otjes and de Jonge2023). In the coalition agreement, the new coalition essentially abandoned the previous policy aimed at reducing nitrogen emissions. Instead, the coalition promised to take a firm stance with the European Commission in order to secure exceptions to the rules surrounding nitrogen pollution. However, the EU indicated that the Netherlands’ current exemption regarding the spreading of manure on fields would end in 2026. In response, Wiersma, the BBB Minister of Agriculture, introduced a bill that would require livestock farmers who sold their businesses to relinquish part of their rights to have livestock to help limit manure production. This regulation would affect all sectors of livestock farming, including cattle, pigs, and poultry. On 18 December, the Council of State, the highest administrative court, ruled that businesses could not use unused nitrogen emission rights from existing permits for new projects (known as the internal settlement scheme). Instead, a new permit would be necessary for any new project. However, given the significant level of nitrogen pollution, new permits were not available.